I. Introduction

Religion is widely recognized as a key determinant of drinking behavior, often operating through social norms that promote abstention or strict moderation (Castro et al., Reference Castro, Barrera, Mena and Aguirre2014; Michalak et al., Reference Michalak, Trocki and Bond2007; Najjar et al., Reference Najjar, Young, Leasure, Henderson and Neighbors2017). The tension between cultural norms and alcohol consumption was vividly illustrated during the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, when authorities banned alcohol sales in stadiums, triggering intense public debate (Swart and Ishac, Reference Swart, Ishac, Elbanna, Elsharnouby, Aljafari and Fatima2025). In the context of global wine trade, such cultural influences are particularly salient as international demand has surged in Northern Europe and North America, where the role of religion in shaping the behavior of younger generations is comparatively limited (Pew Research Center, 2018). This surge in demand has contributed to the rapid expansion of the global wine market: exports have grown from around 10% of global production in the 1960s to 30% in the 2010s (Mariani et al., Reference Mariani, Pomarici and Boatto2012) and 42% by 2022 (Snoussi-Mimouni et al., Reference Snoussi-Mimouni, Wijkström and Meier-Ewert2023). Yet, despite growing evidence that culture systematically shapes trade patterns (e.g., Gurevich et al., Reference Gurevich, Herman, Toubal and Yotov2025; Melitz and Toubal, Reference Melitz and Toubal2014, Reference Melitz and Toubal2019), much of the wine literature focuses on traditional trade policy instruments, such as tariffs and non-tariff barriers (NTB), with cultural factors typically relegated to crude proxies accounted for by bilateral dummies (Yotov et al., Reference Yotov, Piermartini and Larch2016). This leaves their economic importance largely unexamined and, in turn, limits their consideration in market-development efforts.

In this paper, we examine the relationship between the religious composition of countries and wine trade flows, focusing on variation across nine major religious groups. We use a theory-based structural gravity model of bilateral wine trade, following the universal gravity framework (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Arkolakis and Takahashi2020). We posit that trade costs are affected by the extent of religious similarity between importing and exporting countries. Our analysis relies on a newly constructed bilateral wine trade dataset combined with country-level religious composition data from the World Values Survey (WVS) (Haerpfer et al., Reference Haerpfer, Inglehart, Moreno, Welzel, Kizilova, Diez-Medrano, Lagos, Norris, Ponarin and Puranen2022). First, we estimate how the shares of common denominations across major religious groups between trading partners relate to bilateral wine flows. We find that a one-percentage-point increase in the share of the Protestant denomination is associated with a 1.3% increase in wine trade flows. We then use a general equilibrium (GE) framework to explore how global religious alignment could affect global wine trade. If all trading pairs shared complete alignment in the Protestant denomination, total wine exports from major exporters could be up to three times higher than in a scenario where wine tariffs are eliminated. Welfare gains in this scenario would be up to four times larger than those under zero tariffs.

Our paper contributes to three key strands of the literature. First, it contributes to the growing literature on how cultural factors, particularly language and physical appearance, affect trade flows (Egger and Lassmann, Reference Egger and Lassmann2015; Egger and Toubal, Reference Egger, Toubal, Ginsburgh and Weber2016; Gurevich et al., Reference Gurevich, Herman, Toubal and Yotov2025; Melitz, Reference Melitz2008; Melitz and Toubal, Reference Melitz and Toubal2014, Reference Melitz and Toubal2019). Our work expands this literature by developing a dataset linking countries' bilateral trade flows with their degree of common religious composition, disaggregated across nine major denominations (Roman Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, Other Christian, and Others). By focusing on this level of detail, we reveal essential variations in religion's role in trade that have been largely overlooked. Our analysis shows that cultural and religious factors could influence wine trade patterns more than tariffs and should be integrated into trade promotion strategies alongside traditional economic indicators. The findings suggest that considering cultural compatibility can improve market access, branding, and the development of long-term trade relationships.

Second, we expand the understanding of the determinants of wine trade, which encompasses factors such as economic integration (Castillo et al., Reference Castillo, Villanueva and García‐Cortijo2016), religion (Helble, Reference Helble2007), and customs districts' access to wine production (Chan, Reference Chan2025). Using a GE framework, we simulate the impact of a hypothetical global shift toward a religion for which there is preliminary evidence of a positive association with alcohol trade flows. Incorporating domestic trade flows provides an important dimension to the analysis, enabling us to isolate the effects of changes in religious composition on international trade. This approach addresses an important gap by combining detailed data on religious composition with bilateral trade flows, and by examining these relationships within a theory-consistent structural gravity framework (Yotov et al., Reference Yotov, Piermartini and Larch2016). Our results highlight the role of cultural factors compared to mainstream policy variables such as tariffs.

A more subtle contribution of our paper relates to the literature on historical changes in wine consumption (K. Anderson and Pinilla, Reference Anderson and Pinilla2022; Ayuda et al., Reference Ayuda, Ferrer-Pérez and Pinilla2020). This body of work examines the growth of wine globalization and the factors driving increased supply and demand in European and non-European regions, including shifts in production, trade policies, and marketing strategies. We extend this line of work by linking historical trends in international wine trade to the religious composition of countries. Prior studies have shown that behavioral traits and cultural norms, particularly religiosity and spirituality, can strongly influence alcohol consumption patterns across societies (Aldwin et al., Reference Aldwin, Park, Jeong and Nath2014; Bock et al., Reference Bock, Cochran and Beeghley1987; Maseeh et al., Reference Maseeh, Sangroya, Jebarajakirthy, Adil, Kaur, Yadav and Saha2022; Michalak et al., Reference Michalak, Trocki and Bond2007). These works demonstrate that religious beliefs and practices often shape attitudes toward alcohol, producing significant variation in consumption.

II. Methods and data

A. Universal gravity model

We rely on a trade model that falls within the universal gravity framework outlined by Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Arkolakis and Takahashi2020). This model enables us to analyze the trade effects of changes in religious composition, assuming that these changes affect bilateral trade costs. Similar cultural factors have also been treated as determinants of trade costs in the gravity literature (Melitz, Reference Melitz2008; Melitz and Toubal, Reference Melitz and Toubal2014, Reference Melitz and Toubal2019). In the model, we assume that there are ![]() $N$ countries, indexed by subscripts

$N$ countries, indexed by subscripts ![]() $i$ or

$i$ or ![]() $j$. Shipping wine from country

$j$. Shipping wine from country ![]() $i$ to country

$i$ to country ![]() $j$ involves incurring iceberg trade costs

$j$ involves incurring iceberg trade costs ![]() ${\tau _{ij}} \geq 1$. There is roundabout production, as in Eaton and Kortum (Reference Eaton and Kortum2002), that combines immobile labor,

${\tau _{ij}} \geq 1$. There is roundabout production, as in Eaton and Kortum (Reference Eaton and Kortum2002), that combines immobile labor, ![]() ${L_i}$, with intermediate input,

${L_i}$, with intermediate input, ![]() ${M_i}$, in a Cobb-Douglas function with constant returns to scale. Thus, total production,

${M_i}$, in a Cobb-Douglas function with constant returns to scale. Thus, total production, ![]() ${Q_i}$, is given by:

${Q_i}$, is given by:

\begin{equation}{Q_i} = {\left( {{A_i}{L_i}} \right)^\zeta }M_i^{1 - \zeta },\end{equation}

\begin{equation}{Q_i} = {\left( {{A_i}{L_i}} \right)^\zeta }M_i^{1 - \zeta },\end{equation} where ![]() ${A_i} \gt 0$ is labor productivity, and

${A_i} \gt 0$ is labor productivity, and ![]() $\zeta \in \left( {0,1} \right]$ is the share of labor in costs.

$\zeta \in \left( {0,1} \right]$ is the share of labor in costs. ![]() ${M_i}$ is a constant elasticity of substitution (CES) aggregate of the differentiated varieties in all locations, and is assumed to be the same bundle of goods as those entering final consumption, so that the price index,

${M_i}$ is a constant elasticity of substitution (CES) aggregate of the differentiated varieties in all locations, and is assumed to be the same bundle of goods as those entering final consumption, so that the price index, ![]() ${P_i}$, for intermediates, is the price index taken over all goods.

${P_i}$, for intermediates, is the price index taken over all goods.

Under perfect competition, the price of output in country i is given by:

\begin{equation}{p_i} = \bar \kappa {\left( {\frac{{{w_i}}}{{{A_i}}}} \right)^\zeta }P_i^{1 - \zeta },\end{equation}

\begin{equation}{p_i} = \bar \kappa {\left( {\frac{{{w_i}}}{{{A_i}}}} \right)^\zeta }P_i^{1 - \zeta },\end{equation} where ![]() $\bar \kappa $ is a constant and

$\bar \kappa $ is a constant and ![]() ${w_i}$ is the local wage rate. The value of total output is given by

${w_i}$ is the local wage rate. The value of total output is given by ![]() ${Y_i} \equiv {p_i}{Q_i}$. Since we assume that labor is the only factor of production and profits are zero, all output is distributed to workers, resulting in the identity

${Y_i} \equiv {p_i}{Q_i}$. Since we assume that labor is the only factor of production and profits are zero, all output is distributed to workers, resulting in the identity ![]() ${Y_i} = {p_i}{Q_i} = {w_i}{L_i}$. This means that

${Y_i} = {p_i}{Q_i} = {w_i}{L_i}$. This means that ![]() ${Y_i}{\text{ }}$ is simultaneously a measure of a country's value of production and total income.

${Y_i}{\text{ }}$ is simultaneously a measure of a country's value of production and total income.

The price of wine from country ![]() $i$ to country

$i$ to country ![]() $j$ is expressed as:

$j$ is expressed as:

The quantity of wine reaching country ![]() $j$ after subtracting iceberg trade costs, is denoted by

$j$ after subtracting iceberg trade costs, is denoted by ![]() ${q_{ij}}$. The expenditure on wine from country

${q_{ij}}$. The expenditure on wine from country ![]() $i$ in country

$i$ in country ![]() $j$ is given by:

$j$ is given by:

In equilibrium, markets clear, which means that prices and quantities adjust so that total output at every origin country equals aggregate demand from all locations, accounting for iceberg trade costs, so that  ${Q_i} = \mathop \sum \limits_{j = 1}^N {q_{ij}}{\tau _{ij}}$.

${Q_i} = \mathop \sum \limits_{j = 1}^N {q_{ij}}{\tau _{ij}}$.

Each country ![]() $i$ has a representative consumer who values wine from different countries based on CES preferences, as in Armington (Reference Armington1969), Anderson (Reference Anderson1979), and Anderson and Van Wincoop (Reference Anderson and Van Wincoop2003). Wine is differentiated by country of origin, following the Armington (Reference Armington1969) assumption. The consumer supplies labor inelastically and earns all income from it. The consumer's optimization problem leads to a demand equation for wine from country

$i$ has a representative consumer who values wine from different countries based on CES preferences, as in Armington (Reference Armington1969), Anderson (Reference Anderson1979), and Anderson and Van Wincoop (Reference Anderson and Van Wincoop2003). Wine is differentiated by country of origin, following the Armington (Reference Armington1969) assumption. The consumer supplies labor inelastically and earns all income from it. The consumer's optimization problem leads to a demand equation for wine from country ![]() $i$ in country

$i$ in country ![]() $j,\;{X_{ij}}$, which is given by:

$j,\;{X_{ij}}$, which is given by:

\begin{equation}{X_{ij}} = \frac{{{{\left( {{p_i}{\tau _{ij}}} \right)}^{ - \theta }}}}{{P_j^{ - \theta }}}{E_j},\end{equation}

\begin{equation}{X_{ij}} = \frac{{{{\left( {{p_i}{\tau _{ij}}} \right)}^{ - \theta }}}}{{P_j^{ - \theta }}}{E_j},\end{equation} where ![]() $\textstyle\theta$ is the trade elasticity with respect to trade costs, which is a parameter governing how trade flows react to changes in trade costs.Footnote 1

$\textstyle\theta$ is the trade elasticity with respect to trade costs, which is a parameter governing how trade flows react to changes in trade costs.Footnote 1  $P_j^{ - \theta } = \mathop \sum \limits_{k = 1}^N {\left( {{p_k}{\tau _{kj}}} \right)^{ - \theta }}$ is the importer multilateral resistance term and

$P_j^{ - \theta } = \mathop \sum \limits_{k = 1}^N {\left( {{p_k}{\tau _{kj}}} \right)^{ - \theta }}$ is the importer multilateral resistance term and  ${E_j} = \mathop \sum \limits_i {X_{ij}}$ is total expenditure.

${E_j} = \mathop \sum \limits_i {X_{ij}}$ is total expenditure.

We assume that trade deficits are exogenous. Expenditure is a multiple of output value, such that ![]() ${E_i} = {\Xi }{\xi _i}{Y_i},$ where

${E_i} = {\Xi }{\xi _i}{Y_i},$ where  $\Xi = \displaystyle{\sum_i}Y_i/\displaystyle{\sum_i}{\xi_i}Y_i$ is an endogenous scalar that ensures that the sum of all trade deficits equals zero.

$\Xi = \displaystyle{\sum_i}Y_i/\displaystyle{\sum_i}{\xi_i}Y_i$ is an endogenous scalar that ensures that the sum of all trade deficits equals zero. ![]() ${\xi _i}$ is the exogenous expenditure-output ratio. Finally, we set the numeraire

${\xi _i}$ is the exogenous expenditure-output ratio. Finally, we set the numeraire  $\mathop \sum \limits_i {Y_i} = \bar Y \gt 0$.

$\mathop \sum \limits_i {Y_i} = \bar Y \gt 0$.

B. Partial trade effects

We operationalize the universal gravity model to estimate how changes in religiosity and the religious composition of trading partners affect bilateral trade flows by assuming that bilateral trade costs, ![]() ${\tau _{ij}}$, evolve in time according to:

${\tau _{ij}}$, evolve in time according to:

\begin{equation}{\tau _{ij,t}} = \exp \left( {\ln \left( {{{\text{t}}_{ij,t}} + 1} \right) + {\beta _2}PT{A_{ij,t}} + {\beta _3}CST{U_{ij,t}} + {\text{RE}}{{\text{L}}_{ij,t}}{\gamma } + Inte{r_{ij,t}} + {\lambda _{ij}}} \right),\end{equation}

\begin{equation}{\tau _{ij,t}} = \exp \left( {\ln \left( {{{\text{t}}_{ij,t}} + 1} \right) + {\beta _2}PT{A_{ij,t}} + {\beta _3}CST{U_{ij,t}} + {\text{RE}}{{\text{L}}_{ij,t}}{\gamma } + Inte{r_{ij,t}} + {\lambda _{ij}}} \right),\end{equation} where ![]() ${{\text{t}}_{ij,t}}$ is the applied tariff that country

${{\text{t}}_{ij,t}}$ is the applied tariff that country ![]() $j{\text{ }}$collects from country

$j{\text{ }}$collects from country ![]() $i$ in year

$i$ in year ![]() $t$.

$t$. ![]() $PT{A_{ij,t}}$ is an indicator that

$PT{A_{ij,t}}$ is an indicator that ![]() $i$ and

$i$ and ![]() $j$ have a preferential trade agreement (PTA) in year

$j$ have a preferential trade agreement (PTA) in year ![]() $t$, while

$t$, while ![]() $CST{U_{ij,t}}$ is an indicator for when both countries are part of the same customs union in that year.

$CST{U_{ij,t}}$ is an indicator for when both countries are part of the same customs union in that year. ![]() $Inte{r_{ij,t}}$ is a set of time-varying international border dummies, which help capture globalization trends (Bergstrand et al., Reference Bergstrand, Larch and Yotov2015).

$Inte{r_{ij,t}}$ is a set of time-varying international border dummies, which help capture globalization trends (Bergstrand et al., Reference Bergstrand, Larch and Yotov2015).![]() ${\text{ }}{\lambda _{ij}}{\text{ }}$is a country pair fixed-effect that captures unobserved time-invariant components of trade costs.

${\text{ }}{\lambda _{ij}}{\text{ }}$is a country pair fixed-effect that captures unobserved time-invariant components of trade costs. ![]() ${\text{RE}}{{\text{L}}_{ij,t}}$ is a row vector that contains variables related to the religious similarities of the exporter and importer, and

${\text{RE}}{{\text{L}}_{ij,t}}$ is a row vector that contains variables related to the religious similarities of the exporter and importer, and ![]() ${\gamma }$ is the column vector of estimated partial trade effects of these variables on wine trade flows. The elements in

${\gamma }$ is the column vector of estimated partial trade effects of these variables on wine trade flows. The elements in ![]() ${\text{RE}}{{\text{L}}_{ij,t}}$ are as follows.

${\text{RE}}{{\text{L}}_{ij,t}}$ are as follows.

First, we define cross-country differences in religiosity to analyze the impact of the differences in the strength of religious belief. Religiosity is measured as in Doan and Mai (Reference Doan and Mai2025), who use three questions from the WVS to construct three measures: the share of respondents affiliated with a religion, the average reported importance of religion, and the average frequency of religious service attendance. ![]() $Religiosit{y_{ij,t}}$ is the simple average of these three measures. We then compute the absolute difference in religiosity between exporter and importer,

$Religiosit{y_{ij,t}}$ is the simple average of these three measures. We then compute the absolute difference in religiosity between exporter and importer, ![]() $\Delta Rel_{ij,t}$, as:

$\Delta Rel_{ij,t}$, as:

\begin{equation}{\Delta }Re{l_{ij,t}} = \left| {Religiosit{y_{i,t}} - Religiosit{y_{j,t}}} \right|.\end{equation}

\begin{equation}{\Delta }Re{l_{ij,t}} = \left| {Religiosit{y_{i,t}} - Religiosit{y_{j,t}}} \right|.\end{equation} Second, we examine how shared religious composition between exporter and importer influences wine trade. Specifically, we calculate the share of respondents in the WVS who report belonging to one of nine major religious groups ![]() $r$: Roman Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox (e.g., Russian or Greek), Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, Other Christian (e.g., Evangelical, Pentecostal), and Others. Then, we calculate the common share of respondents belonging to each religious denomination as:

$r$: Roman Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox (e.g., Russian or Greek), Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, Other Christian (e.g., Evangelical, Pentecostal), and Others. Then, we calculate the common share of respondents belonging to each religious denomination as:

\begin{equation}ShareRel_{ij,t}^r = \min \left( {share_{i,t}^r,{\text{ }}share_{j,t}^r} \right),\end{equation}

\begin{equation}ShareRel_{ij,t}^r = \min \left( {share_{i,t}^r,{\text{ }}share_{j,t}^r} \right),\end{equation} where ![]() $share_{i,t}^re$ is the share of respondents who reported being of the

$share_{i,t}^re$ is the share of respondents who reported being of the ![]() $r$ denomination in year

$r$ denomination in year ![]() $t$. We set

$t$. We set ![]() $ShareRel_{ij,t}^r = 0$ for

$ShareRel_{ij,t}^r = 0$ for ![]() $i = j$ to isolate the partial effects on international trade flows (Larch et al., Reference Larch, Monteiro, Piermartini and Yotov2025a).

$i = j$ to isolate the partial effects on international trade flows (Larch et al., Reference Larch, Monteiro, Piermartini and Yotov2025a).

We estimate trade flows, ![]() ${X_{ij,t}}$, using the Poisson Pseudo Maximum Likelihood (Poisson PML) estimator proposed by Santos Silva and Tenreyro (Reference Santos Silva and Tenreyro2006). This estimator is widely used in the gravity literature because it addresses heteroskedasticity and can handle zero trade flows (Yotov et al., Reference Yotov, Piermartini and Larch2016). Wine trade flows are specified as:

${X_{ij,t}}$, using the Poisson Pseudo Maximum Likelihood (Poisson PML) estimator proposed by Santos Silva and Tenreyro (Reference Santos Silva and Tenreyro2006). This estimator is widely used in the gravity literature because it addresses heteroskedasticity and can handle zero trade flows (Yotov et al., Reference Yotov, Piermartini and Larch2016). Wine trade flows are specified as:

\begin{align}{X_{ij,t}} &= \exp \left( {\alpha _0} + {\alpha _1}\ln \left( {{{\text{t}}_{ij,t}} + 1} \right) + {\alpha _2}PT{A_{ij,t}} + {\alpha _3}CST{U_{ij,t}} \right.\cr

&\left. \quad +\, {\text{RE}}{{\text{L}}_{ij,t}}{\delta } + In{t_{ij,t}} + {\mu _{j,t}} + {\mu _{i,t}} + {\mu _{ij}} \right) + {\varepsilon _{ij,t}},\end{align}

\begin{align}{X_{ij,t}} &= \exp \left( {\alpha _0} + {\alpha _1}\ln \left( {{{\text{t}}_{ij,t}} + 1} \right) + {\alpha _2}PT{A_{ij,t}} + {\alpha _3}CST{U_{ij,t}} \right.\cr

&\left. \quad +\, {\text{RE}}{{\text{L}}_{ij,t}}{\delta } + In{t_{ij,t}} + {\mu _{j,t}} + {\mu _{i,t}} + {\mu _{ij}} \right) + {\varepsilon _{ij,t}},\end{align} where ![]() ${\alpha _0}$ is an intercept term,

${\alpha _0}$ is an intercept term, ![]() ${\alpha _1} = - \theta $ is the trade elasticity with respect to trade costs, and

${\alpha _1} = - \theta $ is the trade elasticity with respect to trade costs, and ![]() ${\alpha _2} = - \theta {\beta _2}$ and

${\alpha _2} = - \theta {\beta _2}$ and ![]() ${\alpha _2} = - \theta {\beta _2}$ are the trade-level effects with respect to

${\alpha _2} = - \theta {\beta _2}$ are the trade-level effects with respect to ![]() $PT{A_{ij,t}}$ and

$PT{A_{ij,t}}$ and ![]() $CST{U_{ij,t}}$, respectively.

$CST{U_{ij,t}}$, respectively. ![]() $In{t_{ij,t}} = - \theta Inte{r_{ij,t}}$ are international border-year fixed effects that account for globalization effects.

$In{t_{ij,t}} = - \theta Inte{r_{ij,t}}$ are international border-year fixed effects that account for globalization effects. ![]() ${\mu _{j,t}}$ is an importer-time fixed effect to account for inward (importer) multilateral resistances.

${\mu _{j,t}}$ is an importer-time fixed effect to account for inward (importer) multilateral resistances. ![]() ${\mu _{i,t}}$ is an exporter-time fixed effect to account for outward (exporter) multilateral resistances.Footnote 2 These fixed effects also absorb income-related variation, which may otherwise confound the estimated impact of religion (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Choi and Karlan2021).

${\mu _{i,t}}$ is an exporter-time fixed effect to account for outward (exporter) multilateral resistances.Footnote 2 These fixed effects also absorb income-related variation, which may otherwise confound the estimated impact of religion (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Choi and Karlan2021). ![]() ${\mu _{ij}} = - \theta {\lambda _{ij}}$ are country-pair fixed effects to account for unobserved time-invariant trade costs.

${\mu _{ij}} = - \theta {\lambda _{ij}}$ are country-pair fixed effects to account for unobserved time-invariant trade costs. ![]() ${\varepsilon _{ij,t}}$ is an additive error term, which we cluster at the importer-exporter level to control for any remaining country-pair correlations. The column vector

${\varepsilon _{ij,t}}$ is an additive error term, which we cluster at the importer-exporter level to control for any remaining country-pair correlations. The column vector ![]() ${\delta } = - \theta {\gamma }$ contains trade elasticities with respect to

${\delta } = - \theta {\gamma }$ contains trade elasticities with respect to ![]() ${\text{RE}}{{\text{L}}_{ij,t}}$.

${\text{RE}}{{\text{L}}_{ij,t}}$.

To better understand how changes in shared religious composition affect trade costs, we first estimate Equation (9) using ![]() $ShareRel_{ij,t}^r$ for all nine major religious groups. The reference category in this regression is the common share of respondents who report not belonging to any religion. In this first step, we identify which religious group has the largest effect on

$ShareRel_{ij,t}^r$ for all nine major religious groups. The reference category in this regression is the common share of respondents who report not belonging to any religion. In this first step, we identify which religious group has the largest effect on ![]() ${X_{ij,t}}$. We then run a second regression using only the common share of that specific religion, treating the combined share of all other religions as the base group. This approach addresses potential multicollinearity concerns.

${X_{ij,t}}$. We then run a second regression using only the common share of that specific religion, treating the combined share of all other religions as the base group. This approach addresses potential multicollinearity concerns.

C. GE trade effects

Trade elasticities contained in ![]() ${\delta }$ capture the direct effect of changes in religious composition on trade flows, holding prices, income, and expenditures constant. However, changes in trade costs driven by religious composition can also affect these variables. GE effects account for these adjustments, allowing us to capture the full impact of religious composition on trade flows. We estimate GE effects using the “hat algebra” notation introduced by Dekle et al. (Reference Dekle, Eaton and Kortum2007). For each variable, its hat version is the ratio of the value of the variable in a counterfactual equilibrium relative to the value in a baseline equilibrium. In this way, if

${\delta }$ capture the direct effect of changes in religious composition on trade flows, holding prices, income, and expenditures constant. However, changes in trade costs driven by religious composition can also affect these variables. GE effects account for these adjustments, allowing us to capture the full impact of religious composition on trade flows. We estimate GE effects using the “hat algebra” notation introduced by Dekle et al. (Reference Dekle, Eaton and Kortum2007). For each variable, its hat version is the ratio of the value of the variable in a counterfactual equilibrium relative to the value in a baseline equilibrium. In this way, if ![]() $x$ is the value in the baseline observed equilibrium,

$x$ is the value in the baseline observed equilibrium, ![]() $x'$ is the value in the counterfactual equilibrium, so that

$x'$ is the value in the counterfactual equilibrium, so that ![]() $\hat x = x'/x$. Changes in religious composition are leading to counterfactual trade costs,

$\hat x = x'/x$. Changes in religious composition are leading to counterfactual trade costs,  $\tau _{ij,t}^{'}$, so that:

$\tau _{ij,t}^{'}$, so that:

\begin{equation}\hat \tau _{ij,t}^{ - \theta } = \frac{{\tau _{ij,t}^{' - \theta }}}{{\tau _{ij,t}^{ - \theta }}} = \frac{{\exp \left( {{\text{REL}}{'_{ij,t}}{\delta }} \right)}}{{\exp \left( {{\text{RE}}{{\text{L}}_{ij,t}}{\delta }} \right)}} = {\text{exp}}\left( {\left( {{\text{REL}}{'_{ij,t}} - {\text{RE}}{{\text{L}}_{ij,t}}} \right){\delta }} \right).\end{equation}

\begin{equation}\hat \tau _{ij,t}^{ - \theta } = \frac{{\tau _{ij,t}^{' - \theta }}}{{\tau _{ij,t}^{ - \theta }}} = \frac{{\exp \left( {{\text{REL}}{'_{ij,t}}{\delta }} \right)}}{{\exp \left( {{\text{RE}}{{\text{L}}_{ij,t}}{\delta }} \right)}} = {\text{exp}}\left( {\left( {{\text{REL}}{'_{ij,t}} - {\text{RE}}{{\text{L}}_{ij,t}}} \right){\delta }} \right).\end{equation}We examine two scenarios, with the baseline set to the last year in our sample, 2023. In Scenario 1, all global wine tariffs are set to zero.Footnote 3 This scenario provides a benchmark for trade cost reductions. In Scenario 2, all trading partners share the same religion, which is associated with the highest increase in bilateral wine trade. This scenario captures trade diversions if countries' religious composition changes. While these scenarios are extreme, they illustrate the potential magnitude of religion's impact on trade costs.

The trade model is reduced to a system of equations for ![]() ${\hat p_i}$,

${\hat p_i}$, ![]() ${\hat P_i}$ and

${\hat P_i}$ and ![]() ${\hat \Xi }$ as described in Campos et al. (Reference Campos, Reggio and Timini2024). Once this system is solved, after defining

${\hat \Xi }$ as described in Campos et al. (Reference Campos, Reggio and Timini2024). Once this system is solved, after defining ![]() $\psi = \left( {1 - \zeta } \right)/\zeta $ and

$\psi = \left( {1 - \zeta } \right)/\zeta $ and ![]() ${c_i} = {A_i}{L_i}$, the comparative statics are calculated as:

${c_i} = {A_i}{L_i}$, the comparative statics are calculated as:

\begin{equation}{{{\mathbf{GE}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{Impact}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{on}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{Trade}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{Flows}}:{\text{ }{\widehat X}}}_{ij}} = \widehat \tau _{ij}^{ - \theta }\widehat p_i^{ - \theta }\widehat P_j^\theta {\widehat E_j}\end{equation}

\begin{equation}{{{\mathbf{GE}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{Impact}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{on}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{Trade}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{Flows}}:{\text{ }{\widehat X}}}_{ij}} = \widehat \tau _{ij}^{ - \theta }\widehat p_i^{ - \theta }\widehat P_j^\theta {\widehat E_j}\end{equation} \begin{equation*}{\mathbf{GE}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{Impact}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{on}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{Total}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{Output}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{Value}}:\;{\widehat Y_i} = {\widehat p_i}{\hat Q_i} = {\widehat c_i}\frac{{\widehat p_i^{1 + \psi }}}{{\widehat P_i^\psi }}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\mathbf{GE}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{Impact}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{on}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{Total}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{Output}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{Value}}:\;{\widehat Y_i} = {\widehat p_i}{\hat Q_i} = {\widehat c_i}\frac{{\widehat p_i^{1 + \psi }}}{{\widehat P_i^\psi }}\end{equation*} \begin{equation*}{\mathbf{GE}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{Impact}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{on}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{Welfare}}:\;{\widehat W_i} = {\hat \Xi }{\widehat \xi _i}\frac{{{{\widehat w}_i}}}{{{{\widehat P}_i}}} = {\hat \Xi }{\hat \xi _i}\frac{{{{\widehat c}_i}}}{{{{\widehat L}_i}}}{\left( {\frac{{{{\hat p}_i}}}{{{{\widehat P}_i}}}} \right)^{1 + \psi }}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\mathbf{GE}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{Impact}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{on}}{\text{ }}{\mathbf{Welfare}}:\;{\widehat W_i} = {\hat \Xi }{\widehat \xi _i}\frac{{{{\widehat w}_i}}}{{{{\widehat P}_i}}} = {\hat \Xi }{\hat \xi _i}\frac{{{{\widehat c}_i}}}{{{{\widehat L}_i}}}{\left( {\frac{{{{\hat p}_i}}}{{{{\widehat P}_i}}}} \right)^{1 + \psi }}\end{equation*}We calculate these changes using the iterative algorithm developed by Campos et al. (Reference Campos, Reggio and Timini2024). It builds on Baier et al. (Reference Baier, Yotov and Zylkin2019) to solve for GE price adjustments.

D. Data

We obtain bilateral trade data from an updated version of the International Trade and Production Database for Simulation developed by Borchert et al. (Reference Borchert, Larch, Shikher and Yotov2024). The original database covers 140 industries, with data from 1988 to 2019. Using the same methodology, we extend the database for the wine sector through 2023. An important feature of the database is that it includes domestic trade flows, which are essential for GE analysis. We impute missing domestic trade data following the approach in Borchert et al. (Reference Borchert, Larch, Shikher and Yotov2024). Still, these imputed values are used only in the GE simulations, not in elasticity estimation (Larch et al., Reference Larch, Shikher and Yotov2025b). Country-level religion data is obtained from the WVS (Haerpfer et al., Reference Haerpfer, Inglehart, Moreno, Welzel, Kizilova, Diez-Medrano, Lagos, Norris, Ponarin and Puranen2022). This is a global project that has conducted nationally representative surveys in more than 100 countries annually since 1981. The WVS has also been used in related work, such as Melitz and Toubal (Reference Melitz and Toubal2019). We keep responses to the following WVS questions: A006 (Importance in life: Religion), A065 (Member: belongs to religious organization), F025 (Religious denominations: major groups), and F028 (How often do you attend religious services). For questions with scaled or binary responses, we calculate the simple average of non-missing answers.Footnote 4 For F028, we calculate the share of respondents who identify with each major religion.Footnote 5

Industry-average tariff rates, in ad valorem equivalent terms, are calculated using data from the WITS TRAINS database (UNCTAD, 2024).Footnote 6 Data on PTAs and customs unions is from the USITC Dynamic Gravity Dataset and the World Trade Organization (2024) RTA Database.Footnote 7 Similar to Campos et al. (Reference Campos, Estefania-Flores, Furceri and Timini2023), we estimate the supply elasticity for the wine industry using the share of intermediate inputs in total gross output, as reported in the EUKLEMS & INTANProd database by Bontadini et al. (Reference Bontadini, Corrado, Haskel, Iommi and Jona-Lasinio2023).Footnote 8 We calculate input shares by country, industry, and year, and restrict the sample to values between the 10th and 90th percentiles for each industry-year combination. Using this trimmed data, we compute an average supply elasticity of 2.81 for the wine industry, which we use for the GE analysis.Footnote 9 After merging all datasets, our final dataset covers 102 countries from 1988 to 2023.

We report the descriptive statistics in Table 1. The average annual bilateral export flow is $2.11 million, with a maximum of $2.78 billion. The average ad-valorem equivalent wine tariff is 31.6%. However, a few countries, such as Egypt, imposed extremely high tariffs, in some cases exceeding 2,000%. On average, 27% of importer-exporter pairs share a PTA, and 4% belong to the same customs union. The average difference in religiosity is 0.8, with the average declining between 1988 and 2023. The highest average common shares across countries are found for Roman Catholics, Muslims, and Protestants. However, all three groups show a decline over the sample period.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Note. The table shows the descriptive statistics. We exclude domestic flows from the calculations. Δ1988/2023 is the difference in the mean value between 1988 and 2023. ![]() $\Delta Rel$ represents differences in religiosity. PTA indicates whether the trading partners have a preferential trade agreement, while CSTU shows whether they are part of the same customs union. Ad-valorem tariffs and shares of common religion are reported in percentages. In the regression analysis, we use the shares,

$\Delta Rel$ represents differences in religiosity. PTA indicates whether the trading partners have a preferential trade agreement, while CSTU shows whether they are part of the same customs union. Ad-valorem tariffs and shares of common religion are reported in percentages. In the regression analysis, we use the shares, ![]() $ShareRel_{ij,t}^r,$ without multiplying them by 100.

$ShareRel_{ij,t}^r,$ without multiplying them by 100.

III. Results and discussion

Table 2 shows the baseline regression results. Columns (1) and (2) report estimates using all common religious membership shares, with the only difference being that the former excludes globalization effects while the latter includes them. Following the identification strategy of Fontagné et al. (Reference Fontagné, Guimbard and Orefice2022), who exclude globalization controls, we use Column (1) to compute tariff elasticities. The estimates indicate that increasing average tariffs by 10 percentage points, from the average 31.6% to 41.6%, would reduce wine trade flows by 10.5%. In line with Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Steinbach and Zurita2024), both PTA and CSTU are associated with positive effects on trade. Following Bergstrand et al. (Reference Bergstrand, Larch and Yotov2015), we recover the level effects of PTA and CSTU using estimates from Column (2), which accounts for globalization effects. The results indicate that PTA membership increases bilateral wine trade by an average of 28.1%, while CSTU membership is associated with a 95.6% increase.

Table 2. Impact of religiosity and religious composition on International Wine Trade

Note. The table presents the baseline regression results of common religious composition on bilateral trade flows. ![]() $t$ represents tariffs, and

$t$ represents tariffs, and ![]() $\Delta Rel$ represents differences in religiosity. We use the original shares for common religion without multiplying them by 100. All regressions include exporter-time, importer-time, and exporter-importer fixed effects. Standard errors, shown in parentheses, are clustered at the exporter-importer level.

$\Delta Rel$ represents differences in religiosity. We use the original shares for common religion without multiplying them by 100. All regressions include exporter-time, importer-time, and exporter-importer fixed effects. Standard errors, shown in parentheses, are clustered at the exporter-importer level.

* p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

In Column (2), increasing ![]() $\Delta Rel$ by one unit, increases bilateral wine trade flows by 14.8%, suggesting that greater religious dissimilarity increases trade flows. We interpret this result with caution, as the relationship may reflect correlations with other religious composition variables rather than a direct influence of religiosity gaps. In particular, the level of religiosity may already be captured by the common-share variables. Moreover, the coefficient

$\Delta Rel$ by one unit, increases bilateral wine trade flows by 14.8%, suggesting that greater religious dissimilarity increases trade flows. We interpret this result with caution, as the relationship may reflect correlations with other religious composition variables rather than a direct influence of religiosity gaps. In particular, the level of religiosity may already be captured by the common-share variables. Moreover, the coefficient ![]() $\Delta Rel$ is not significant in all specifications, which may indicate that the coefficient in this regression reflects a spurious correlation. Columns (1) and (2) use the no religion denomination as the reference group for religious composition shares. Controlling for globalization trends, a one-percentage-point increase in the common share of respondents identifying as Protestants raises bilateral wine trade by 0.7%.

$\Delta Rel$ is not significant in all specifications, which may indicate that the coefficient in this regression reflects a spurious correlation. Columns (1) and (2) use the no religion denomination as the reference group for religious composition shares. Controlling for globalization trends, a one-percentage-point increase in the common share of respondents identifying as Protestants raises bilateral wine trade by 0.7%.

In contrast, a one-point increase in the proportion of respondents reporting belonging to Other Christian denominations reduces the wine trade by 4%. These results share similarities with those of Najjar et al. (Reference Najjar, Young, Leasure, Henderson and Neighbors2017), who find that Christians and Muslims have a less religious perception of alcohol than Buddhists and non-religious groups. Their analysis is based on a sample of U.S. undergraduate students, whereas our sample includes data from a broader set of countries and is not limited to students. Previous literature also finds that attitudes toward alcohol consumption differ across Protestant denominations, with religiosity among Conservative Protestants being negatively associated with alcohol use (Bock et al., Reference Bock, Cochran and Beeghley1987). In our analysis, we cannot distinguish between different Protestant groups. What we do observe, however, is that countries with higher common shares of respondents reported as Protestants are primarily located in Northern and Western Europe, North America, and Oceania. These countries may also share cultural norms regarding alcohol consumption, which could help explain our results.

Overall, our regressions show that country pairs with larger common shares of respondents identifying as Protestants tend to have higher levels of wine trade. We use this result for Scenario 2 in the GE analysis. However, this share is mechanically correlated with the shares of other religions, meaning that if one share increases, others must decrease. To simplify interpretation and better isolate the effect of Protestant affiliation, we reestimate Equation (9) using only the common Protestant share. The corresponding estimates are shown in Columns (3) and (4). In these regressions, the reference group is all other religious denominations. We confirm that higher proportions of respondents identifying as Protestants are associated with increased wine trade. Our preferred partial effect estimate for the common Protestant denomination share is taken from Column (4), which controls for globalization trends and is estimated at 1.28. This implies that a one-percentage-point increase in the common Protestant share is associated with roughly a 1.3% increase in the global wine trade. Moreover, to remain consistent with Fontagné et al. (Reference Fontagné, Guimbard and Orefice2022), we recover the demand elasticity from Column (3), where ![]() $\theta $ is estimated at 1.76. This implies a tariff elasticity (or partial effect) of –1.76. Our supply elasticity

$\theta $ is estimated at 1.76. This implies a tariff elasticity (or partial effect) of –1.76. Our supply elasticity ![]() $\psi $ is estimated at 2.88, using data from the EUKLEMS & INTANProd database.

$\psi $ is estimated at 2.88, using data from the EUKLEMS & INTANProd database.

Table 3 presents GE simulation results for our counterfactual scenarios, using 2023, the final year in our data, as the baseline year. Panel (a) shows results for Scenario 1, where all wine tariffs are eliminated worldwide. Panel (b) presents results for Scenario 2, where all countries have a full share of respondents identifying with the Protestant denomination, representing complete global religious alignment. While results are calculated for all countries with domestic consumption in 2023, we focus on the top 10 wine-exporting countries in the sample: France, Italy, Spain, Australia, New Zealand, Chile, the United States, Germany, Argentina, and South Africa. In Scenario 1, exports of major wine-exporting countries would rise between 1.1% and 12.8%. Except for Argentina, the major exporters' wine output value would increase between 0.9% and 5.4%. Welfare would rise for most exporters, with gains ranging from 0.2% to 3.7%. In Scenario 2, total exports by the major wine-exporting countries increase between 64% and 205.9%. Except for Argentina and the United States, wine output value for these countries rises between 26.5% and 108.3%. Welfare improves for all major exporters, with gains ranging from 3.5% to as high as 369.9%. These results suggest that reducing cultural differences may have a larger impact on trade costs than reducing tariffs, which echoes Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Hsieh and Song2022) results for NTBs.

Table 3. Ratio of changes in variables to their original values (![]() $\hat x = x'/x$)

$\hat x = x'/x$)

Note. The table shows the estimated changes of the most relevant variables in our GE analysis. Panel (a) presents changes in the scenario of eliminating all wine tariffs. Panel (b) presents changes under the scenario in which all countries have a full share of respondents identifying with the Protestant denomination.

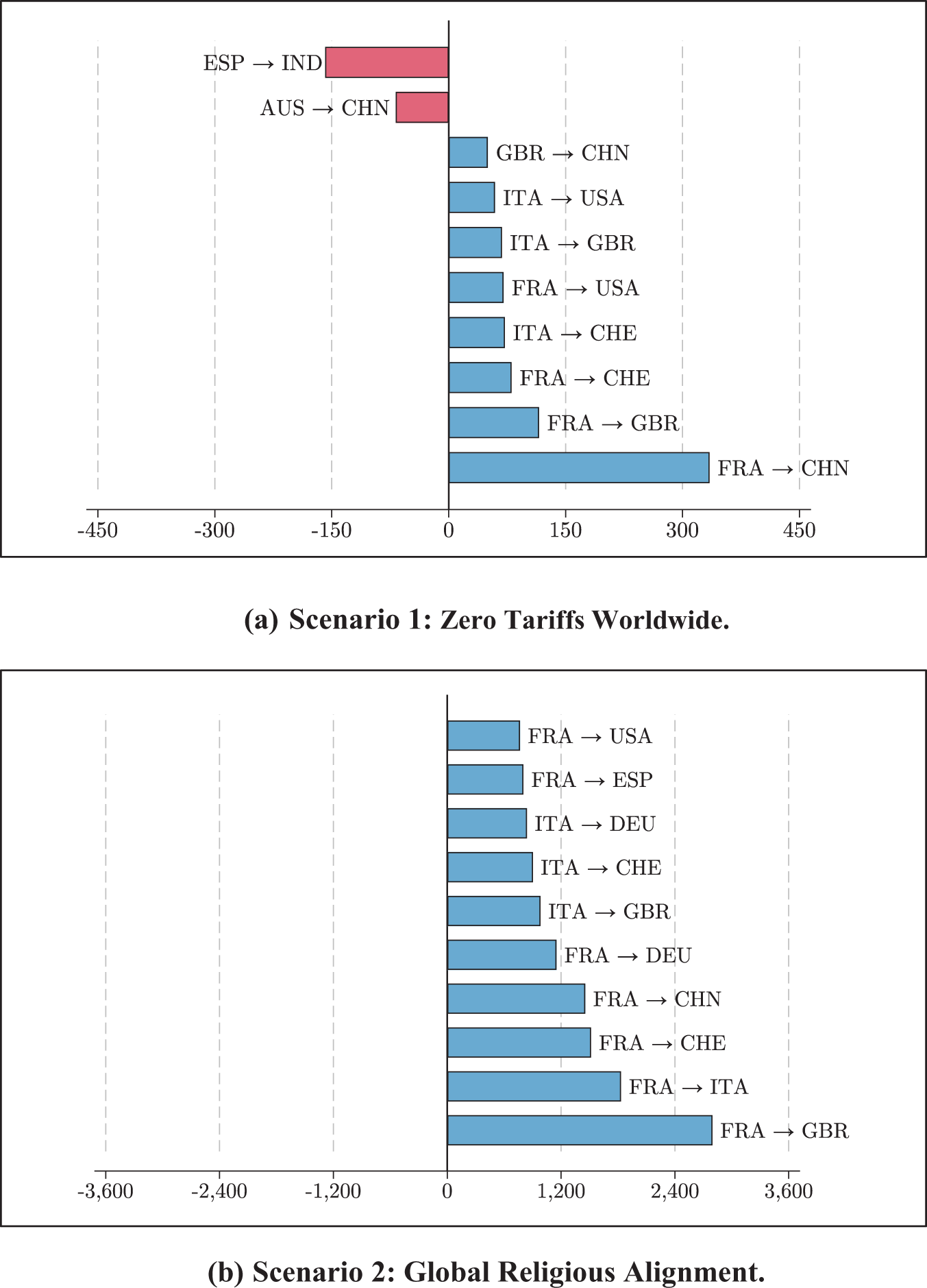

Figure 1 shows the 10 largest wine export reallocations in absolute terms for Scenario 1 (Panel a) and Scenario 2 (Panel b), reported with their respective signs. When global wine tariffs are eliminated, the largest export gain would occur in shipments from France to China, rising by $334.69 million. In the baseline, French wine faces an ad valorem equivalent tariff of 35.4% in China. Conversely, exports from Spain to India would fall by $158.50 million, despite eliminating the 84.5% tariff equivalent that India imposes on Spanish wine. In Scenario 2, all 10 major changes in export flows are positive and 10 times larger than those in Scenario 1. The largest increase would occur in exports from France to Great Britain ($2.8 billion), followed by changes in exports from France to Italy ($1.8 billion). In 2023, France already shipped more than $1.9 billion of wine to Great Britain and more than $400 million of wine to Italy. At the same time, France has a common share of respondents self-identifying as Protestants of less than 2.2% with either country. Under Scenario 2, the pattern indicates that country pairs with substantial existing wine trade but relatively small common Protestant shares tend to experience the largest export expansions.

Figure 1. Top 10 export reallocations in the counterfactual GE scenarios.

IV. Conclusion

This paper examines the relationship between countries' religious composition and their participation in global wine trade. Using bilateral wine trade data from 1988 to 2023, we estimate trade elasticities associated with the common shares of respondents adhering to nine major religious denominations. Our main results show that larger shared proportions of respondents identifying with the Protestant denomination in both exporter and importer countries are associated with higher bilateral wine trade flows. In contrast, higher shares of respondents reporting belonging to Other Christian denominations are associated with lower levels of wine trade flows. A simulation exercise indicates that if all countries were fully aligned with Protestantism, total exports from the major wine-exporting countries would rise by at least 64%. In comparison, their welfare would increase by at least 3.5%. Notably, the impact of changes in religious composition on welfare is up to four times greater than in a scenario where wine tariffs are eliminated globally.

Our results highlight religion as a determinant of trade costs and its influence on wine trade flows. While previous research has emphasized the importance of broader cultural factors, such as language and social distance (Egger and Lassmann, Reference Egger and Lassmann2015; Egger and Toubal, Reference Egger, Toubal, Ginsburgh and Weber2016; Gurevich et al., Reference Gurevich, Herman, Toubal and Yotov2025; Melitz, Reference Melitz2008; Melitz and Toubal, Reference Melitz and Toubal2014, Reference Melitz and Toubal2019), these factors are typically captured as bilateral fixed effects (Yotov et al., Reference Yotov, Piermartini and Larch2016). In contrast, we isolate the effects of specific religious affiliations. Our analysis shows that the trade impact of religion varies by both importer and exporter composition, likely reflecting group-specific norms and attitudes toward alcohol (Bock et al., Reference Bock, Cochran and Beeghley1987; Michalak et al., Reference Michalak, Trocki and Bond2007; Najjar et al., Reference Najjar, Young, Leasure, Henderson and Neighbors2017). We interpret these effects as trade frictions rooted in religious differences, which can restrict wine trade and, in some cases, exceed the impact of traditional trade policies such as tariffs. This interpretation aligns with Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Hsieh and Song2022), who find that NTBs often impose greater trade costs than tariffs by selectively limiting access for specific exporters. In our context, countries with lower religious alignment tend to face higher implicit trade costs and stand to gain the most from greater global convergence in religious composition.

Our findings underscore the importance of historical similarities in religious composition for trade costs. Although the global religious alignment scenario that we analyze is extreme, the results illustrate how significant religious differences can be in shaping trade costs, often rivaling or exceeding the impact of tariffs. For the wine sector specifically, our results suggest that cultural alignment, particularly shared religious norms, which also capture shared cultural norms toward alcohol consumption, meaningfully shape trade patterns. These findings are particularly relevant for exporters seeking to expand into new markets, as they suggest that trade promotion strategies may benefit from considering cultural and religious factors alongside traditional economic factors. Similarly, industry groups and international trade agencies need to take into account how cultural compatibility influences market access, branding, and long-term trade relationships.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the editor and two anonymous referees for their comments, which substantially improved the paper.

Funding statement

This paper was supported by an AAWE Research Scholarship.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.