Introduction

The Flinders Islands Rock Art Project was initiated by the Traditional Owners of the islands, the Aba Wurriya, and is the latest in a series of collaborations between the Aba Wurriya and Australian and international researchers (e.g. Adams et al. Reference Adams2021). The intention of the Aba Wurriya in embarking on these projects is to improve understanding of the history of the islands and enhance protection of the islands’ cultural heritage.

Geography and environment

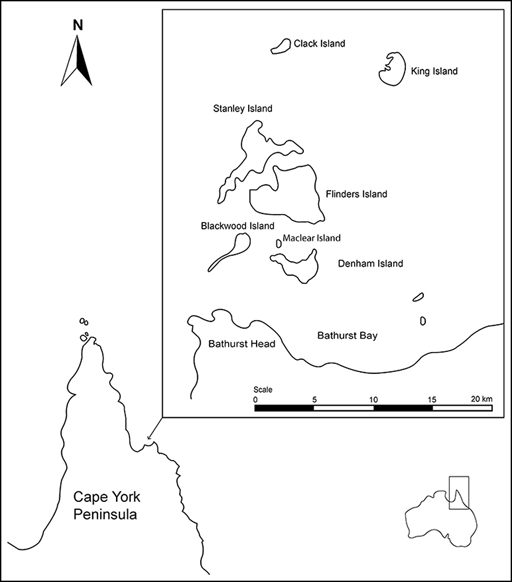

The Flinders Islands are in Princess Charlotte Bay, which is approximately 340km north-west of Cairns and 350km south-east of the tip of Cape York in Queensland, Australia (Figure 1). There are seven main islands in the group: Flinders (Wurriima), Stanley (Muyu Mali), Denham (Inggal Odul), Blackwood (Wakayi), Clack (Ngurromo), Maclear (Yukamini) and King (Murirrrma).

Figure 1. Location of the Flinders Islands Group (figure by authors).

Composed of sandstone, the islands are relatively small (≤1460ha) and low lying (≤205m above sea level). Topographically rugged, they feature cliffs, steep escarpments and sand dunes (Figure 2). The main vegetation types are heathy woodland, grassland and vine thickets. Mangroves, salt flats and seagrass beds are found near the shore. A recent survey recorded more than 100 animal species on the islands (Augusteyn et al. Reference Augusteyn, Hines and McDougall2023), while surrounding waters support crocodiles, dugong, turtles and numerous fish species.

Figure 2. Examples of environments encountered in the Flinders Islands (photograph ‘a’ by H. Williams, used with permission; photographs b–d by Oliva Arnold).

The islands’ climate is tropical; the ambient temperature ranges between 20 and 33°C, and monsoon rains usually begin in November and last until April.

History

Recent work at Yindayin Shelter on Stanley Island indicates that humans were using the islands by 6280 cal BP (Wright et al. Reference Wright, Faulkner, Westaway, Thakar and Flores Fernández2023). Oral history identifies the Aba Wurriya as the first inhabitants (Peter Sutton pers. comm. 2018) and ethnographic accounts indicate that the Aba Wurriya moved between the islands and the mainland, subsisting on both marine and terrestrial resources (Hale & Tindale Reference Hale and Tindale1933).

Ethnographic records (Sutton et al. Reference Sutton, Chase and Rigsby1993) and archaeological evidence (Adams et al. Reference Adams2021) further show that the Aba Wurriya were part of a far-reaching social network.

The first recorded meeting of the Aba Wurriya and Europeans took place in 1821 (King Reference King1837). The islands subsequently became a stopping point for ships travelling between Sydney and Asia, before becoming a centre for pearling and beche-de-mer fishing (Walsh Reference Walsh1984). These developments greatly impacted the Aba Wurriya. Between 1899 and 1935, the islands experienced a 90 per cent decline in population—from 84 people to just nine (Sutton Reference Sutton, Verstraete and Hafner2016)—and in the 1940s, the Aba Wurriya were permanently relocated to Hopevale and Palm Island (Sutton Reference Sutton, Verstraete and Hafner2016).

Previous research on the rock art

The islands’ rock art was first mentioned in print during the 1830s (King Reference King1837), but it was not until the 1880s that some of the motifs were published (Coppinger Reference Coppinger1883). Subsequently, Roth (Reference Roth1899) reported finding rock art sites on Clack. Hale and Tindale (Reference Hale and Tindale1933) discussed additional sites but did not conduct a survey. Several decades later, Walsh (Reference Walsh1984) documented over a dozen rock art sites in an assessment of the islands’ archaeology.

More detailed analyses were carried out by David in the 1990s using Walsh’s (Reference Walsh1984) data (David Reference David1994; David & Chant Reference David and Chant1995; David & Lourandos Reference David and Lourandos1998). David concluded that the islands’ rock art and that of the adjacent mainland are homogeneous, although he noted a greater emphasis on sea-related motifs on the islands (David Reference David1994). He also concluded that the style of the rock art of the Flinders Islands and the adjacent mainland is distinct from that of other parts of Cape York, reflecting a process of regionalisation in the Late Holocene (David & Chant Reference David and Chant1995; David & Lourandos Reference David and Lourandos1998). One of the main goals of the present project is to reassess these interpretations with a larger, more systematically collected dataset.

Project activities

The Flinders Islands Rock Art Project involves three main activities: 1) recording rock art using digital technology; 2) developing a taxonomy of the motifs; and 3) comparing the Flinders Islands’ rock art with corpora of rock art found elsewhere in the region.

Recording the sites

Fieldwork was conducted on Flinders, Stanley and Denham islands in 2022 and 2023 by Olivia Arnold and five Traditional Owners. Other islands were not surveyed due to cultural restrictions.

The team visited 13 known sites (four on Flinders, six on Stanley and three on Denham) and located two new sites (one on Stanley and one on Flinders). The co-ordinates of each site were recorded with GPS, and contextual imagery was captured with a drone camera. Each site’s rock art was recorded with digital cameras and a smartphone 3D scanner app. DStretch was used to improve interpretation of faded and/or superimposed motifs. Using this combination of techniques, the team documented a total of 1468 motifs (Figure 3); over 30 per cent more than the 1093 reported by Walsh (Reference Walsh1984).

Figure 3. Select motifs recorded by this project (photographs by Olivia Arnold).

After completing the fieldwork, we combined our data with Walsh’s (Reference Walsh1984) data for Clack Island. The motifs were then discussed with community members. A series of ship motifs proved to be of particular interest (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Some of the ship motifs recorded by the present project (photographs by Olivia Arnold).

Developing a taxonomy

Taxonomic analyses of the motifs are ongoing. So far, 10 major categories have been identified. The most common is ‘Marine Animal’ (29% of all motifs), followed by ‘Other Animal’ (22%; dominated by a moth/butterfly (motjala) motif; Figure 5) and ‘Mythical Being’ (15%), which includes a zoomorph with a crescent head (Figure 6). Less common is ‘Terrestrial Animal’ (9%). Together, these categories account for 75 per cent of motifs. No other category individually exceeds six per cent.

Figure 5. Examples of the moth/butterfly (motjala) motif found at some rock art sites in the Flinders Islands (photographs by Olivia Arnold).

Figure 6. An example of the ‘Mythical Being’ (a) with a crescent head represented in colour and greyscale DStretch Filter: LXX (photograph by Olivia Arnold).

Comparative analyses

Preliminary results support a shared motif repertoire across the islands but also show that different islands favour different motifs. For example, ‘Mythical Being’ dominates on Clack (49% of motifs), while ‘Marine Animal’ is most common on Stanley (38% of motifs). This variation may reflect subgroup-specific utilisation of different islands (e.g. only males were permitted to visit Clack).

Conclusions

The Flinders Islands Rock Art Project has already substantially enriched the motif database for the islands and we expect current analyses to shed new light on the Aba Wurriya’s history. These outcomes will support efforts to improve protection of the islands’ heritage, including an application to the Australian National Heritage List.

Acknowledgements

This project is covered by National Parks Permit No. WITK16288415. Logistical support for fieldwork was provided by Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS). We thank the Traditional Owners, all fieldwork volunteers and QPWS.

Funding statement

Mark Collard is supported by the Canada Research Chairs Program, the Canada Foundation for Innovation and the British Columbia Knowledge Development Fund. Part of this research is supported by Michael C Westaway’s Australian Research Council Future Fellowship grant FT180100014.