Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic posed a challenge not only for infectiology and intensive care but also for other essential healthcare services [1], such as mental health services (MHS). Fears of infection, post-COVID syndromes, the psychological effects of infection control measures, and economic hardships may have led to changes in the demand for MHS [Reference Ahrens, Neumann, Kollmann, Plichta, Lieb and Tüscher2–Reference Kunzler, Röthke and Günthner4]. Similarly, infection control measures, resource reallocations, a focus on somatic medicine, and changes in incentive structures may have—among other factors—altered the provision of mental healthcare services [Reference Chevance, Gourion and Hoertel5–Reference Wiegand, Bröcker and Fehr7].

Several studies have reviewed the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on MHS utilization. In a systematic review, Duden et al. [Reference Duden, Gersdorf and Stengler8] narratively synthesized the evidence regarding challenges and changes in global MHS during the pandemic. They reported reductions in demand, access, referrals, admissions, and caseloads during the initial phases of the pandemic, followed by normalizations or even increases later on. They interpreted their results as evidence that community MHS were quite adaptable and resilient to the challenges posed by the pandemic. Another global trend was the introduction of telemedicine services [Reference Duden, Gersdorf and Stengler8]. Steeg et al. [Reference Steeg, John and Gunnell9] examined presentations to MHS following self-harm. They reported a reduction in the first month of the pandemic in 2020 but a trend toward normalization in 2021 and even an increase in service use among adolescent girls. However, these latter results were based on a limited number of studies [Reference Steeg, John and Gunnell9]. Wan Mohd Yunus et al. systematically reviewed studies on service use in children, adolescents, and young adults aged 0 to 24 years. They found decreases in service use during the early phases of the pandemic. They interpreted these findings as potentially indicative of delayed treatment and unmet needs [Reference Wan Mohd Yunus, Kauhanen, Sourander, Brown, Peltonen and Mishina10]. In their systematic review of MHS use, Ahmed et al. reported decreases in inpatient admissions by 11–43%, presentations to emergency departments and walk-in services by 14–58%, and community mental health and outpatient services by 24–75%, alongside a shift from in-person to telemedicine contacts [Reference Ahmed, Barnett and Greenburgh11]. Inpatient services remained below pre-pandemic levels in late 2020 and 2021, whereas community mental health and outpatient services reported higher-than-pre-pandemic utilization [Reference Ahmed, Barnett and Greenburgh11].

These existing reviews have some limitations in estimating the effect of the pandemic on MHS utilization. They were either restricted to defined syndromes [Reference Steeg, John and Gunnell9] or services [Reference Wan Mohd Yunus, Kauhanen, Sourander, Brown, Peltonen and Mishina10] or provided only narrative syntheses [Reference Duden, Gersdorf and Stengler8, Reference Ahmed, Barnett and Greenburgh11]. Furthermore, it is important to account for the considerable heterogeneity in the level of observation of the studies on MHS utilization, which ranged from single emergency departments to entire countries. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the global literature on MHS utilization. Such a synthesis of study results is of high relevance for discussions on the evaluation of pandemic response measures in the context of their impacts on other areas of care, and for learning from a comprehensive picture of changes in order to be better prepared for future crisis situations.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included studies that examined the utilization of the mental healthcare system and compared the period before the COVID-19 pandemic with the period during the COVID-19 pandemic, to quantify changes to pre-pandemic utilization levels. We excluded studies that only compared periods during the pandemic with intervals after the pandemic, because of assumed changes in offerings and utilization patterns in some areas of MHS after the pandemic. We only focused on studies employing quantitative research methodologies, including longitudinal studies (prospective and retrospective), cohort studies, and analyses of routine data, while excluding qualitative research. Results were categorized into three service types: inpatient, emergency department (ED), and outpatient services. Additionally, outpatient telemedicine services and outpatient medication prescriptions were examined separately. Inpatient services included planned inpatient hospitalizations, emergency inpatient admissions, or admissions resulting from visits to emergency departments. Outpatient services encompassed general practitioner visits, mental health specialist visits, outpatient telemedicine services (e.g., video calls, phone calls), individual or group psychotherapy, and outpatient prescriptions for psychotropic medications. A detailed overview of the settings for each study is provided in the supplementary material (Supplementary Material Figure S6). Only studies involving populations with a known or newly diagnosed mental disorder according to ICD-10 or DSM-5 were included. Participants had to be 18 years of age or older. In cases where the population age was not clearly stated or where there were mixed adult and adolescent populations, the authors were contacted to confirm that the study either did not include or only minimally (cutoff <15% of patients) included individuals under 18 years of age. Studies that focused on suicide or suicide attempts but not diagnosed mental disorders or utilization, as well as case reports, qualitative surveys, intervention studies, commentaries, and discussion papers, were excluded.

Search strategy and screening process

The methods of this systematic review were predefined and registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, registration number CRD42022334792) [Reference Glock, Lieb and Wiegand12] and were conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines [13]. We searched Embase for English-, French-, and German-language sources published from November 2019—the time when the COVID-19 disease first emerged and later developed into a pandemic—up to July 2022, and PubMed and PsycINFO from November 2019 until 30.03.2025.

The search strategy combined terms related to COVID-19 (e.g., “COVID-19,” “SARS-CoV-2,” “2019-nCoV”) and mental health (e.g., “mental health,” “mental disorders,” “psychiatric disorders”) using both free-text terms and controlled vocabulary (MeSH terms). The Supplementary Material (Supplementary Material Figure S9) presents the complete search strategy for the three databases. Using Endnote [14], the studies identified were imported into Covidence [15] for title/abstract and full-text screening. To identify additional references, we manually searched the reference lists of the identified reviews. After duplicates were removed, the reviewers performed the title, abstract, and full-text screenings in tandems of two.

Data extraction

We extracted the following data from each study: authors, study characteristics (aim of study, study design, country, setting, time periods considered), population details (age, gender), the number of visits or consultations in the respective setting, and psychiatric diagnoses according to ICD-10 or DSM-5 (for details, see Table 1). Two independent reviewers conducted the data extraction process, resolving discrepancies through discussion or consensus within the review group.

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies

Study observation periods

We selected 2019 as the reference year for studies comparing multiple years with 2020 to ensure consistency and enhance comparability across studies. However, studies with different comparison periods were also included. Whenever possible, we compared the same periods before and during the pandemic to minimize the influence of seasonal variations on service utilization. An overview of the observation periods for each study can be found in the Supplementary Material in Table S5. For analysis we separated studies that examined the initial phase of the pandemic outbreak in 2020 (short term), using a cut-off of 8 months, from those that investigated longer periods, such as the entire year 2020 or subsequent years (long term).

COVID-19 containment and health index

To show the country-specific degree of COVID-19 containment measures for the respective periods of the included studies, we added the COVID-19 Containment and Health Index (CCHI) [16] to Supplementary Table 2. This index “is a composite measure based on 13 policy response indicators, including school closures, workplace closures, travel bans, testing policy, contact tracing, face coverings, and vaccine policy, rescaled to a value from 0 to 100 (100 = strictest)” [16].

Quality assessment

The quality of the included studies was assessed using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies [Reference Wells, Shea, O’Connell, Peterson, Welch, Losos and Tugwell17]. This scale evaluates studies across three main categories—Selection, Comparability, and Outcome—comprising eight subcategories in total. A maximum of seven stars could be awarded, with a star (“☆”) indicating that the criterion was met. If a criterion was not met, it was marked with a “/” symbol (for details, see Table S1 and S2 in the Supplementary Materials).

Level of observation

To estimate the quantitative changes in service utilization during the pandemic more reliably, we categorized the studies into three groups based on the varying data foundations:

-

• Category A studies: Complete or nearly complete surveys of a larger region, state, or country (e.g., regional health register data, health insurance data, or healthcare data from main regional community health providers).

-

• Category B studies: Samples covering several departments or clinics that do not represent the main or only healthcare provider within a defined larger region or cover the complete or nearly complete population of such a region (e.g., “13 Germany-based hospitals”).

-

• Category C studies: Data from individual clinics or departments (e.g., “Geneva University Medical Center”).

Data analysis

In our meta-analysis, the natural logarithm of the rate ratio (ln(RR)) was used as the effect size for statistical computations. Random-effects models were employed to estimate summary effect sizes, accounting for both within-study and between-study variability. After conducting the analyses, the ln(RR) values were exponentiated to obtain the rate ratios (RR), which are presented in all figures and tables for ease of interpretation. All analyses were performed using RStudio (Version 2023.09.1) with R (Version 4.4.1). Heterogeneity was assessed using the I 2 statistic from Cochran’s Q and τ 2 calculated with the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) method. To assess publication bias, funnel plots were generated for each setting (Supplementary Figure S2a–e).

Results

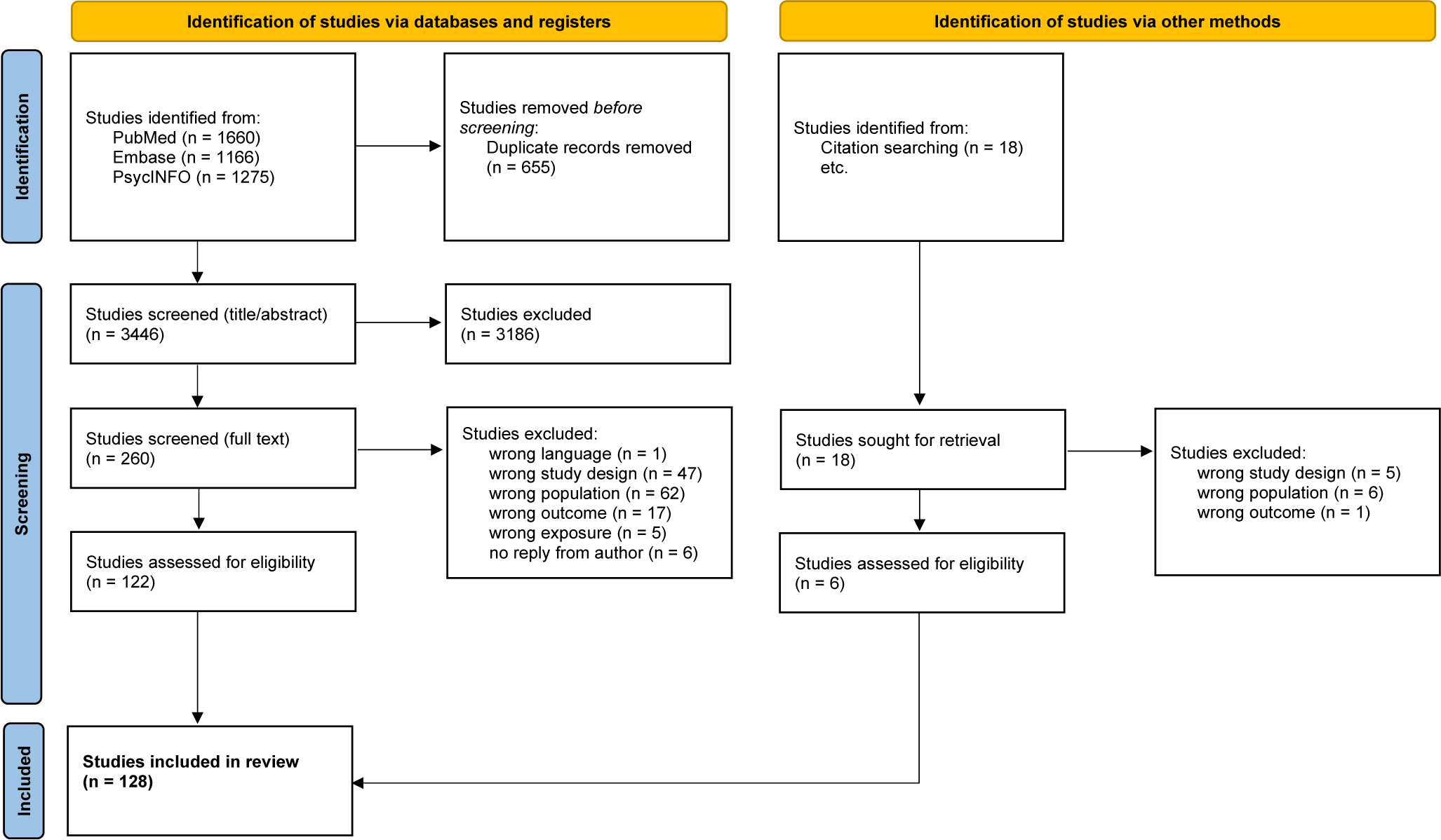

Initially, 4101 records were retrieved and 655 duplicates were excluded. After title/abstract screening, 260 studies remained for full-text screening. Following the full-text screening, 122 studies from the database search were included. The interrater-agreement showed a Cohen’s Kappa of 0.74. Citation screening identified 18 additional studies, of which 6 were selected for inclusion, resulting in a total of 128 studies included in the review [13]. Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA flow diagram, outlining the steps involved in the screening and selection process.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of study selection.

Four studies [Reference Flodin, Sörberg Wallin and Tarantino18–Reference Silva-Valencia, Lapadula and Westfall21] report results from multiple countries. The following countries are represented in our review: the United States [Reference Luo, Chai and Li19, Reference Silva-Valencia, Lapadula and Westfall21–Reference Wang, Anand, Bena, Morrison and Weleff43] with 25 studies, Italy [Reference Luo, Chai and Li19, Reference Balestrieri, Rucci and Amendola44–Reference Di Valerio, Fortuna, Montalti, Alberghini, Leucci and Saponaro57] with 15 studies, Germany [Reference Luo, Chai and Li19, Reference Engels, Stein, Konnopka, Eichler, Riedel-Heller, König, Klauber, Wasem, Beivers and Mostert58–Reference Goldschmidt, Kippe, Finck, Adam, Hamadoun and Winkler69] with 13 studies, the United Kingdom [Reference Luo, Chai and Li19, Reference Bakolis, Stewart and Baldwin70–Reference Simkin, Yung, Greig, Perera, Tsamakis and Rizos78] with 10 studies, Spain [Reference Gómez-Ramiro, Fico and Anmella79–Reference Irigoyen-Otiñano, Porras-Segovia, Vega-Sánchez, Arenas-Pijoan, Agraz-Bota and Torterolo86] with 8 studies, Canada [Reference Silva-Valencia, Lapadula and Westfall21, Reference McKee, Crocker and Tibbo87–Reference Ying, Yarema and Bousman93] and Sweden [Reference Flodin, Sörberg Wallin and Tarantino18, Reference Moreno-Martos, Zhao and Li20, Reference Silva-Valencia, Lapadula and Westfall21, Reference Andersson and Håkansson94–Reference Lieber and Werneke97] with 7 studies each, South Korea [Reference Luo, Chai and Li19, Reference Seo, Kim, Lee and Kang98–Reference Kim, Lee, Hong, Han and Paik101], Australia [Reference Silva-Valencia, Lapadula and Westfall21, Reference Jagadheesan, Danivas, Itrat, Shekaran and Lakra102–Reference Zaki and Brakoulias105] and China [Reference Silva-Valencia, Lapadula and Westfall21, Reference Lee, Mo and Lam106–Reference Zhang, Chen and Xiao109] with 5 studies each, France [Reference Luo, Chai and Li19, Reference Pignon, Gourevitch and Tebeka110–Reference Perozziello, Sousa, Aubriot and Dauriac-Le Masson112] with 4 studies, Croatia [Reference Vukojević, Đuran, Žaja, Sušac, Šekerija and Savić113–Reference Savić, Vukojević, Mitreković, Bagarić, Štajduhar and Henigsberg115], Netherlands [Reference Flodin, Sörberg Wallin and Tarantino18, Reference Chow, Noorthoorn, Wierdsma, Van Der Horst, De Boer and Guloksuz116, Reference Visser, Everaerd, Ellerbroek, Zinkstok, Tendolkar and Atsma117], Switzerland [Reference Ambrosetti, Macheret and Folliet118–Reference Wullschleger, Gonçalves, Royston, Sentissi, Ambrosetti and Kaiser120] and Turkey [Reference Yalçın, Baş, Bilici, Özdemir, Beştepe and Kurnaz121–Reference Muştucu, Güllülü, Mete and Sarandöl123] with 3 studies each, Malta [Reference Bonello, Zammit, Grech, Camilleri and Cremona124, Reference Warwicker, Sant, Richard, Cutajar, Bellizzi and Micallef125], Portugal [Reference Alves, Marques and Carvalho126, Reference Gonçalves-Pinho, Mota, Ribeiro, Macedo and Freitas127] and Saudi Arabia [Reference Ramadan, Fallatah, Batwa, Saifaddin, Mirza and Aldabbagh128, Reference Jahlan, Alsahafi, Alblady and Ahmad129] with 2 studies each. Additionally, one study originated from each of the following countries: Belgium [Reference Flament, Scius, Zdanowicz, Regnier, De Cannière and Thonon130], Denmark [Reference Rømer, Christensen, Blomberg, Folke, Christensen and Benros131], Ireland [Reference McAndrew, O’Leary, Cotter, Cannon, MacHale and Murphy132], Israel [Reference Pikkel Igal, Meretyk and Darawshe133], Serbia [Reference Golubovic, Zikic, Nikolic, Kostic, Simonovic and Binic134], South Africa [Reference Wettstein, Tlali and Joska135], Argentina [Reference Silva-Valencia, Lapadula and Westfall21], Austria [Reference Fellinger, Waldhör and Vyssoki136], Hungary [Reference Gajdics, Bagi, Farkas, Andó, Pribék and Lázár137], Japan [Reference Abe, Suzuki, Miyawaki and Kawachi138], Kosovo [Reference Rugova, Kryeziu-Rrahmani, Jahiu, Dakaj, Rrahmani and Kryeziu139], Latvia [Reference Flodin, Sörberg Wallin and Tarantino18], New Zealand [Reference Hansen, McLay and Menkes140] and Singapore [Reference Silva-Valencia, Lapadula and Westfall21] (Supplementary Table S3). All continents were represented. However, the majority of studies came from the European Region (86 studies), followed by 35 studies from the Americas, 18 from the Western Pacific, 4 from the Eastern Mediterranean Region, and 1 from the Africa Region (Supplementary Figure S1), according to World Health Organization (WHO) specifications [141]. According to the World Bank classification, only high-income and upper-middle-income economies were represented (Supplementary Table S4). Detailed data are provided in Table 1. Furthermore, Supplementary Table 2 presents the individual index values of the COVID-19 Containment and Health Index for each studies region and the corresponding comparison period during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Most studies included in our analysis compared periods from 2019 with similar periods during the pandemic. The length of comparison periods varied, with some studies examining only a few months, mainly during COVID-19 high-incidence or lockdown periods, while others covered an entire year. Some studies also compared non-equivalent periods within the same year (e.g., the end of 2019 to the beginning of 2020) (Supplementary Table S5). Supplementary Table 2 outlines the distribution of the studies across different settings and the respective periods during the pandemic. In some cases (e.g. 58, 59, 94, 122), it was possible to extract and analyze data from both the short-term and long-term comparison periods and data for these extended time periods.

Sixty-four studies examined inpatient services. Forty-three studies addressed ED services, and 43 studies covered outpatient services. Twenty studies focused on psychotropic medication and 16 studies on telemedicine services (Table 1).

Four studies, listed in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2 were excluded from the meta-analysis either due to insufficient comparability [Reference Adorjan, Pogarell and Pröbstl60, Reference Correia, Greyson, Kirkwood, Darling, Pahwa and Bayrampour91] or because the data combined multiple service settings, preventing a disaggregated analysis of individual settings [Reference Palzes, Chi, Metz, Campbell, Corriveau and Sterling40, Reference Leonhardt, Bramness, Rognli and Lien142].

Supplementary Figure S7 shows the classification of studies into one of the three levels of observation categories, as described in the Methods section. We performed separate calculations for the meta-analysis, including only the most representative category A and B studies and all three categories (Supplementary Table 2). In the following, we outline results for studies that belong to level of observation categories A or B, and we report short-term (first 8 month of the pandemic) separately from long-term comparison periods. The results for category C studies are presented in Supplementary Table 2. The corresponding forest plots for category C, as well as the forest plots for the long-term observations, can be found in the Supplementary Material (Figure S8a-d).

For the initial phase of the pandemic, all settings, except for telemedicine, showed a decrease in service utilization (Supplementary Table 2). High τ 2 values, particularly for telemedicine (τ 2: 0.51), reflect substantial between-study variability. We performed detailed subgroup analyses based on ICD-10 F-diagnosis disease categories for inpatient (Figure 2), emergency department (Figure 3), and partly outpatient service (Figure 4) as a sufficient number of Category A or B studies were only found for these settings.

Figure 2. Forest plots of inpatient services utilization. AFR = African Region, AMR = Americas, EUR = European Region, WPR = Western Pacific Region.

Figure 3. Forest plots of emergency department service utilization. AFR = African Region, AMR = Americas, EUR = European Region, WPR = Western Pacific Region.

Figure 4. Forest plots of health care service utilization. (a–c) outpatient services, (d) telemedicine cases, (e) medication prescriptions. AFR = African Region, AMR = Americas, EUR = European Region, WPR = Western Pacific Region.

Inpatient services utilization

First, we analyzed changes in inpatient service utilization. During the initial phase of the pandemic, a significant decrease in utilization was observed across all diagnosis groups (RR: 0.75, 95% CI: 0.67 to 0.85, n = 16 studies, I 2 = 99.6%, Tau2 = 0.064) (Figure 2a). The analysis of diagnostic subgroups showed significant decreases in utilization for substance-related disorders (ICD-10 F1) (RR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.66 to 0.92, I 2 = 97.7), schizophrenia, schizotypal, delusional, and other non-mood psychotic disorders (ICD-10 F2) (RR: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.75 to 0.98, I 2 = 96.6%), mood disorders (ICD-10 F3) (RR: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.66 to 0.87, I 2 = 99.0%), anxiety, dissociative, stress-related, and somatoform mental disorders (ICD-10 F4) (RR:0.72, 95% CI: 0.62 to 0.84, I 2 = 98.4%), and personality disorders (ICD-10 F6) (RR: 0.87, 95% CI: 0.75 to 1, I 2 = 89.4%) (Figure 2c–g). No significant changes were observed for organic mental disorders (ICD-10 F0) (Figure 2b). For the long-term comparison period, a less pronounced but statistically significant decline in inpatient utilization was observed (RR: 0.93, 95% CI: 0.89 to 0.98, I 2 = 99.8%) (Supplementary Table 2).

Emergency department service utilization

Next, we examined ED utilization for mental disorders. The meta-analytic model showed a reduction of RR: 0.87 (95% CI: 0.69 to 1.10, n = 8 studies, I 2 = 99.7%, Tau2 = 0.108) across all diagnosis groups for the initial phase of the pandemic (Figure 3a). The analysis for diagnosis subgroups (ICD-10 F1, F2, F3, and F4) showed no significant change (Figure 3b–e). For the long-term comparison periods, a non-significant, slight increase in the utilization of mental health ED services was observed, with substantial heterogeneity in primary studies (RR: 1.18, 95% CI: 0.66 to 2.09) (Supplementary Table 2).

Outpatient services, telemedicine, medication

Finally, we examined changes in outpatient and telemedicine service utilization and psychotropic medication prescriptions. Due to the small number of studies, no diagnostic subgroup analyses were performed for telemedicine and medication prescriptions. During the initial phase of the pandemic, we observed a significant decrease in outpatient service utilization (RR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.66 to 0.92, n = 15 studies, I 2 = 100%, Tau2 = 0.102) (Figure 4a). The analysis for diagnosis subgroups (ICD-10 F2 and F3) in the outpatient setting showed no significant change, whereas meta-analysis showed a significant increase in the utilization of telemedicine (RR: 7.57, 95% CI: 3.63 to 15.77, n = 4 studies, I 2 = 100%, Tau2 = 0.516) (Figure 4d) and no significant change in psychotropic medication prescriptions (RR: 0.90, CI: 0.77 to 1.05, n = 15 studies, I 2 = 100%, Tau2 = 0.129) (Figure 4e).

For the long-term comparison periods, a significant decrease in the utilization of outpatient services (RR: 0.79, 95% CI: 0.65 to 0.97, I 2 = 100%), and telemedicine services (RR: 18.38, 95% CI: 3.63 to 93.08, I 2 = 100%) was observed, whereas medication prescriptions showed no significant change (RR: 0.91, 95% CI: 0.74 to 1.11, I 2 = 100%).

Regional differences in service utilization

For some regions, meta-analysis of regional results were possible: For Europe inpatient psychiatric service utilization declined consistently across all ICD-10 F groups (F1 = RR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.69 to 0.88, F2 = RR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.80 to 0.97, F3 = RR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.72 to 0.85, F4 = RR: 0.71, 95% CI: 0.64 to 0.78), while decreases in the Western Pacific Region were smaller and non-significant (F2 = RR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.71 to 1.03, F3 = RR: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.66 to 1.07, F4 = RR: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.76 to 1.07). For the ED setting, Europe showed significant reductions only for organic mental disorders (F1 = RR: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.54–0.97). Studies from the Americas showed stable or slightly increased utilization (total = RR: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.87 to 1.21). Corresponding forest plots are in Supplementary Figure S3.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis of MHS utilization demonstrates significant changes during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period. The most prominent change is a significant decrease in inpatient service utilization during the first month of the pandemic. In contrast, reductions in ED, outpatient services, and psychotropic medication utilization were less pronounced. The analysis of ED studies showed the importance of relying on representative samples, as the Category C studies showed significant reductions, whereas the analysis of the more representative Category A and B studies showed (for all diagnostic groups together) no significant change, even for the initial month of the pandemic. For the long-term observations, reductions in MHS service utilization were smaller, which might reflect an adaptation of patients and systems seeking to balance infection protection with the need for services. The introduction of telemedicine and modifications to clinical practices likely contributed to this recovery. Overall, the reductions in the initial period seemed to be more pronounced in Europe, as meta-analyses of studies from other world regions, like the Western Pacific Region or the Americas, did not indicate significant changes.

For the initial period of the pandemic, the analyses showed differential effects depending on subgroups of mental disorders (according to ICD-10). Significant reductions in inpatient care were noted for substance use disorders (ICD-10 F1), affective disorders (F3), neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders (F4), and personality disorders (F6), whereas for organic mental disorders (F0) and schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders (F2), no significant reductions were observed. Regarding ED utilization, a reduction reaching statistical significance was only observed for substance use disorders (F1).

There are no indications that the prevalence or treatment needs for substance use disorders (ICD-10 F1), affective disorders (ICD-10 F3), and neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders (ICD-10 F4) declined during the pandemic. It is more likely that disruptions in service availability and access, as well as patients’ fears of infection or general policy measures like curfews and so forth led to decrease in inpatient treatment utilization for these patients. As well, it is not known in which regions and to what degree existing flexible healthcare models like assertive community treatment or telemedicine were able to compensate for reduce inpatient or outpatient in-person offerings. In that sense, some mental healthcare systems might have been better equipped to deal with the challenges of the pandemic. However, to our knowledge, no large-scale systematic studies have investigated the effects of the reductions on treatment quality, treatment outcomes, or infection prevention. Therefore, these reductions and the potential harm from delayed treatment cannot be assessed. This underscores the need for more systematic monitoring of mental health system utilization and quality at national and international levels.

In this context, the regional and economic imbalance of the included studies is notable: most were from Europe, but even within the European Union, studies were from only 12 of the 27 member states. 27 countries were classified as high-income economies and seven as upper-middle-income economies. No countries from lower-middle-income or low-income economies were represented in our review. Within Europe, this calls for a harmonized mental health system utilization and quality indicators to become an essential part of the planned European Health Data Space, which would enable more comparable European health policies and their effects. This would allow us to learn from the most successful models.

The remarkable increase in telemedicine service utilization (RR: 7.57) can be seen as an essential adaptation of mental healthcare systems. It would be desirable for these service levels to be maintained beyond the pandemic, as they could help mitigate the shortage of qualified mental healthcare professionals, especially in rural areas, and provide low-barrier, low-stigma access options. However, in this context, the evidence base for telemedicine interventions, especially for long-term treatments for severely ill patients, needs further expansion, and access barriers to digital services need to be taken into consideration [Reference Sánchez-Guarnido, Urquiza, Sánchez, Masferrer, Perles and Petkari81, Reference Scott, Clark, Greenwood, Krzyzaniak, Cardona and Peiris143].

Our findings are consistent with previous studies during times of health crisis and longer-term disasters like the SARS outbreaks in Taiwan and Toronto, the West African Ebola outbreak or following Hurricane Katrina, that were showing significant declines in healthcare utilization for outpatient, inpatient, and emergency services. Those reductions were due to fears of infection and restrictive measures [Reference Chang, Huang, Lee, Hsu, Hsieh and Chou144, Reference Schull, Stukel, Vermeulen, Zwarenstein, Alter and Manuel145, Reference Brolin Ribacke, Saulnier, Eriksson and Von Schreeb146] as well as infrastructure loss and system fragmentation [Reference Arrieta, Foreman, Crook and Icenogle147].

This review has several limitations: It focuses only on the first year of the pandemic. Trends in service utilization may have evolved in subsequent years. Continued monitoring and analysis of service usage in the following years are needed to capture the long-term effects and recovery processes in mental health care. The aforementioned geographic and economic imbalance of the included studies limits the generalizability of the findings to global contexts. Future research should aim for studies from a broader, more representative range of regions to enhance the external validity of the findings. The review was limited to studies identified in three databases and restricted to publications in three languages, thus potentially impacting the comprehensiveness of the review. Furthermore, we analyzed only shifts in utilization, but we could not take into account differential access to services, e.g., to telemedicine due to lack of access to technology or digital literacy. In general, the restriction to quantitative studies limits the interpretation, e.g., with regard to the background of changes and experiences of those affected. This review included only studies on adult MHS. It should be repeated for child and adolescent MHS utilization, as those populations seemed to be especially burdened by the pandemic.

The heterogeneity of study results was high, and care must be taken when interpreting these results. This, in comparison to the meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials, high heterogeneity was not unexpected, as healthcare system organization (see Supplementary Table S3), regional infection protection policies (see CCHI in Supplementary Table 2), and the impact of COVID-19 varied between countries and world regions. Another contributing factor was the heterogeneity of study designs, and sample sizes, ranging from studies with millions of participants to those with as few as 100. This variability may affect the robustness and comparability of the meta-analytic findings, potentially introducing bias and reducing the reliability of the overall conclusions. Therefore, the effects should not be evaluated in terms of their absolute value, but it should be emphasized that they were observed despite the great heterogeneity in MHS organization and protection measures. Consensus on further methodological standardization for studies of healthcare utilization should be pursued [Reference Steeg, John and Gunnell9].

Overall, our analyses suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic led to substantial shifts in mental healthcare utilization, with increased reliance on telemedicine alongside reductions in inpatient and emergency services. It remains unclear to what degree telemedicine or other flexible care interventions were able to compensate for those reduced services, especially as they can also have significant access barriers. The reductions were likely to have left specific patient populations, such as people with substance use disorders, affective disorders, or neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders, underserved. To prepare MHS better for future public health challenges, better internationally comparable longitudinal mental health system utilization and quality surveillance data are needed. Such data would allow us to learn which care models are able to maintain needs-oriented, high-quality care even during disruptive crises like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2025.10119.

Data availability statement

The extracted data will be made available on GitHub once the manuscript is published.

Author contribution

MG, JSD, SL, OT, KL, LPH, KA, and HFW conceptualized the review protocol, MG, JSW, SL, LPH, KA, and HFW the search strategy. MG, AE, MR, FU, RH, KA and HFW did the literature (title-abstract and fulltext) screening. MG, AE, MR, FU, RH, and HFW performed the data extraction and quality assessment. MG, AE, JSW and HFW performed the meta ananlysis. MG, OT, LPH, KL, KA and HWF drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed by critical reading and improving the manuscript.

Financial support

This publication was partially funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) as part of the Network University Medicine (NUM): “NaFoUniMedCovid19,” Grant No: 01KX2021 and 01KX2121, Project: “egePan-Unimed” and “PREPARED.” It was partially founded by the Leibniz-Lab Pandemic Preparedness: One Health, One Future of the Robert-Koch-Institute Berlin, Germany (Grant No: LIR_2023_01) and the EU Horizon 2020-Project RESPOND (Grant Agreement 101016127).

Competing interests

All authors report no conflicts of Interest.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.