Preamble

Henry Nouwen’s classic treatise on pastoral care, The Wounded Healer,Footnote 1 highlighted an ambiguity of pastoral care: that many who care for others are themselves damaged and wounded. In doing so, he stripped away the pretension that carers must be perfect, superhuman beings, but rather could function effectively as agents of healing and transformation in spite of their own weaknesses and limitations. It is a book which enabled many carers to accept their own weakness and limitation, and use their own suffering as a vehicle for healing.Footnote 2 It is one of those rare books which stimulates a paradigm shift: a fresh approach to a long-standing phenomenon.Footnote 3

History suggests that it is now time for a fresh paradigm shift. There has been an increasing recognition that Christianity and many of its constituent churches have been complicit in a variety of abusive situations. Popular discussion has occasioned the realization that the church itself has bloody hands. Yet, recognition of this is not some fresh blinding revelation, but has been long recognized, especially by peoples who have been on the receiving end of behaviours that Jon Sobrino described starkly:

For some reason it has been possible for Christians, in the name of Christ, to ignore or even contradict fundamental principles that were preached and acted upon by Jesus of Nazareth.Footnote 4

Furthermore, it has become increasingly difficult to deny involvement in such behaviours historically. Some grim examples, the tip of an iceberg, suffice: the complicity of churches in the abuses of the stolen generations of first nations peoples,Footnote 5 in the Atlantic slave trade,Footnote 6 and in the PadroadoFootnote 7 are increasingly recognized as failures of witness to the truths of the gospel. Yet, the ever-present human ability to ignore or deny such tragedies has delayed a full and proper recognition of these injustices in privileged, usually northern, Christian circles. The distance of privilege has often silenced the cries of the victims and the poor, even, tragically, in contexts where they were neighbours.

What has provoked the privileged church to awaken from its reflective slumber and denial of its complicity has, more than anything else, been the barrage of revelations of historic sexual abuse which have been uncovered across a multitude of Christian groups and denominations, often on their own doorsteps.Footnote 8 Gerald W. Hughes astutely summarized the scale and effects of such findings:

It will probably take us decades to unravel the complexities and to understand more clearly the underlying reasons for the crimes, for the nature of the public reaction to them, to learn how to protect children without afflicting them with paranoia, and to know how to act justly and effectively with the offenders so that they do not offend again and are offered hope for the future.Footnote 9

This has hit so close to home that even the most tin-eared have had had to sit up and take notice. Consequently, the reality that the church has made a significant contribution to both abuse and trauma is inescapable. It is important to note that both have occurred, and to start these reflections with definitions of both, the differences between them, and the realization that they may be the consequence of both intentional and unintentional behaviour – which in no way condones or excuses what has happened.

Abuse

The events outlined above have caused much reflection on what constitutes abuse. If attention is focused on the global Anglican Communion, the Anglican Consultative Council (ACC-9) meeting of 1993, subsequent ACC meetings, the Lambeth Conferences of 1998 and 2008, Primates’ Meetings and specialist consultations all considered what constituted abuse.Footnote 10 They identified several behaviours which constituted abuse:

-

bullying;

-

concealment of abuse;

-

cyber abuse;

-

emotional abuse;

-

financial abuse;

-

gender-based violence;

-

harassment;

-

neglect;

-

physical abuse;

-

sexual abuse; and

-

spiritual abuse.Footnote 11

From this arose the Anglican Communion Safe Church Commission (ACSCC) Guidelines (hereafter Guidelines).Footnote 12 Individual provinces were scrutinized for their handling of allegations of abuse, for example, in England and Australia. Investigations such as the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse identified several factors that contribute to abusive culture, which include, but are not exhausted by:

-

victim-blaming, shame, and honour;

-

use of religious texts and beliefs;

-

gender disparity;

-

abuse of power by religious leaders;

-

distrust of external agencies;

-

fear of external reporting and reputational damage;

-

managing allegations internally; and

-

forgiveness, especially if misused to block reporting and justify failures.Footnote 13

The Guidelines neatly summarize behaviours aimed at fostering a culture in which:

-

church workers act with integrity;

-

victims of abuse receive justice;

-

church workers who commit abuse are held accountable; and

-

church leaders do not conceal abuse.Footnote 14

Five commitments underpin these:

-

1. Pastoral support where there is abuse;

-

2. Effective responses to abuse;

-

3. Practice of pastoral ministry;

-

4. Suitability for ministry;

-

5. Culture of safety.Footnote 15

The Anglican Diocese of Newcastle in New South Wales, which had been particularly hard hit by the investigations of abuse, adopted their own protocols:

-

The handling of historic abuse within a framework shaped by the gospel mandates;

-

The reporting of cases through safe and trustworthy channels;

-

Restitution for hurts;

-

Healing for victims of abuse;

-

Transparency and a firm intention to recognize the potential for, and avoid, conflicts of interest;

-

Means for perpetrators to enter into a process through which the true nature of abuse is recognized (which must work in tandem with state and federal law) and conversion is possible;

-

Which demands a means for perpetrators to continue to worship and share in the life of the community without licence to put others at risk or to re-offend;

-

In which the fears of all parties (victims, perpetrators and bystanders) are minimized.Footnote 16

Caution is needed: good intentions will not eliminate abuse. Michael Salter, reflecting on events in the same Anglican Diocese of Newcastle, warns that they may not even produce institutional forms and behaviours which will generate benevolence:

A key insight of critical theory is that the rationalising ethos of modernity has not eradicated cruelty and atrocity but instead structured and mechanised it in more efficient and effective ways. This observation would appear to hold true in the case of institutional abuse and neglect, which emerges not from contexts of social anomie, but rather from highly structured and organised environments. Nonetheless, sexual abuse prevention strategies frequently endorse, and strengthen, technocratic forms of human organization without considering their links to institutional wrongdoing and sexual coercion.Footnote 17

Commenting on a specific instance of sexual abuse which occurred there, he added:

Abusive sexualities that take shape and form within instrumentalised systems of power can be expanded and projected via those same systems.Footnote 18

Churches need constantly to be vigilant against the emergence of abuse in new forms. However, when turning to trauma, it must be noted that it, and its appearance within church life, is not always the consequence of vicious behaviour. It may arise accidentally, or even because of church members engaging in behaviours that are part and parcel of church life and practice.

Trauma

‘Trauma’, while commonly used, defies an easy or glib description.Footnote 19 The American Psychological Association offers a description that focuses on the emotions:

Trauma is an emotional response to a terrible event like an accident, rape or natural disaster. Immediately after the event, shock and denial are typical. Longer term reactions include unpredictable emotions, flashbacks, strained relationships and even physical symptoms like headaches or nausea. While these feelings are normal, some people have difficulty moving on with their lives. Psychologists can help these individuals find constructive ways of managing their emotions.Footnote 20

However, its extent is limited neither to these situations, nor emotional contexts. Trauma has increasingly been recognized as a much broader set of phenomena, which may include physical, psychological, social and spiritual damage. Thus, the Australian Psychological Society notes:

Potentially traumatic events are powerful and upsetting incidents that intrude into daily life. They are usually experiences which are life threatening or pose a significant threat to a person’s physical or psychological wellbeing.Footnote 21

Such events provoke a number of responses:

Symptoms of trauma can be described as physical, cognitive (thinking), behavioural (things we do) and emotional.

-

Physical symptoms can include excessive alertness (always on the look-out for signs of danger), being easily startled, fatigue/exhaustion, disturbed sleep and general aches and pains.

-

Cognitive (thinking) symptoms can include intrusive thoughts and memories of the event, visual images of the event, nightmares, poor concentration and memory, disorientation and confusion.

-

Behavioural symptoms can include avoidance of places or activities that are reminders of the event, social withdrawal and isolation and loss of interest in normal activities.

-

Emotional symptoms can include fear, numbness and detachment, depression, guilt, anger and irritability, anxiety and panic.Footnote 22

Trauma may affect groups as well as individuals. Here, the experience of trauma may both explain suffering and foster collective identity:

In a collective, it is a shared sense of suffering felt by the collective that motivates certain groups to propose narratives to name and account for the suffering and that also moves the collective to accept a given narrative. Erikson captures the reality that the social fabric of a collective can be severely ruptured, irrespective of whether the collective has adopted a common narrative to account for the suffering. Alexander captures the reality that, when the group accepts a narrative for its collective suffering, that narrative has a capacity to shape the identity of the collective.Footnote 23

Abuse, a vicious set of behaviours, is inextricably linked with trauma, but is not its sole source. It is, perhaps, more useful to describe trauma as a consequence of disaster.Footnote 24 Trauma may, for example, affect not just those directly affected, but those who suffer vicariously, ministering to the victims of disaster or in the workplace,Footnote 25 or witnessing it as bystanders. Thus, for example, in the case of abuse, not only the victims are traumatized, but also those who live with their abuse, or are involved in the processes of addressing it. When sustained over a long period of time or repeated exposure, such trauma may contribute to phenomena such as burn-out.Footnote 26

If trauma suggests a wider range of experiences in which the church may be an agent, it might be asked why comments about abuse have preceded it, and why we might think of the church as an ‘abusive healer’. There are two reasons. First, as has been suggested, it is the recognition of the church’s involvement in abuse that has provoked much of the reflection on trauma.

The second is grimmer. It would be possible for a church focusing on trauma to deny that it plays a role in abuse. After all, trauma, as the above analysis has shown, may be a result of experiences which have neither been abusive nor intentional. Trauma may even be considered a consequence of imitating Christ in ministry and viewed as either a necessity or a virtue: ‘Take up thy cross’, as the old hymn goes. Thus, a church which identified as a traumatized healer might claim to be a fellow sufferer: what might be called victim-claiming.Footnote 27 Perversely, the pain of those who are traumatized may even be branded something virtuous or valuable. Those who are traumatized can be told that this is a necessary part of their discipleship.Footnote 28 But this should never happen on those occasions where the church as an institution has been complicit in abuse, or failed to protect its members and ministers, for example, ‘in the workplace’. A church which denies or remains ignorant of its potential to practise or enable harm, and history shows that it has and can, is much more likely to find itself embroiled in similar behaviours in the future. Even if trauma has arisen from an accident or an unforeseen circumstance, lessons can be learned to avoid repetition: ‘ Kilichoniuma jana nikaona uchunguwe hakinitambai tena’ – ‘That which bit me yesterday and hurt me, does not crawl over me a second time.’Footnote 29 So, ‘abusive healer’ is better suited to remind churches and Christians of their potential to cause harm and, in describing it in such terms, of how undesirable such behaviours really are, whether trauma is suffered directly or vicariously.

Some scholars have noted that trauma may provide a lens through which Scripture may be read, interpreted and contribute to strategies for pastoral care:

While trauma can refer to severe physical injury, it is psychological and social trauma, their reflexes in literature, and the appropriation of that literature that have garnered significant attention among biblical interpreters. Developments in the fields of psychology, sociology, refugee studies, and comparative literature have all influenced the manner in which they employ the lens of trauma. Biblical interpreters recognize manifold aspects of trauma, which include not only the immediate effects of events or ongoing situations but also mechanisms that facilitate survival, recovery, and resilience. Trauma hermeneutics is used to interpret texts in their historical contexts and as a means of exploring the appropriation of texts, in contexts both past and present. Footnote 30

This potential has been recognized by, among others, Gerald O. West in his account of biblical texts such as 1 Sam. 13.1-22 being used for social transformation when community workshops address violence against women in South African contexts. Here, the use of Scripture enables a subject usually considered taboo to be named and addressed.Footnote 31

Ritual also may play a part in both naming and healing trauma, not least because it provides a forum in which such Scriptures are identified as valuable in shaping responses to it:

Religious ritual can cultivate safety, nurture social bonds, and foster both discursive and nondiscursive modes of representing collective suffering.Footnote 32

It is from such perspectives that the accounts of the bronze serpent become valuable for locating the role of the church as an abusive or traumatizing healer.

The Bronze Serpent: The Lifted Healer

And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up,15 that whoever believes in him may have eternal life. (Jn 3.14-15, nrsv)

The character of the serpent must be addressed, not least because of our human primal and instinctive response to snakes.Footnote 33 It may immediately be off-putting or negative – a feature which serves well to illustrate the response that trauma may have had on the onlooker. As such it may provoke a reminder that the stuff of faith can be turned to harm. But, as the bronze serpent is a potential image of healing, it must be remembered that the ancients knew that medicine and poison are never far apart.

Derrida could identify three related characteristics: ‘not only pharmakos (victim or scapegoat) and pharmakon (medicine/poison), but also pharmakeus (sorcerer or magician)’.Footnote 34 Indeed, antiquity knew multiple symbolic meanings for the serpent: 16 that might be classed as negative, and 29 as positive.Footnote 35 The gospel belongs to a world which could use serpent symbolism positively. Indeed, it might be used to indicate any of divinity, life, immortality and even resurrection:Footnote 36 the bronze serpent may be understood as divine, a healer or both. This is not as alien to our modern world as it might first appear: the caduceus (the staff of Hermes with intertwined snakes) remains, up to the present, a sign of healing.Footnote 37 Thus, the first stage of engagement with the serpent is to shift from revulsion to attraction.

This text provides a distinctively Christian focus for reflection on the nature of healing by drawing on an incident from the history of Israel (Num. 21.4−9) to articulate an understanding of the lifting up of Jesus. The event has a chequered reception within Judaic tradition: 2 Kgs 18.4 describes the smashing of a bronze serpent by Hezekiah, while Wis. 16.6 describes it as a ‘symbol of salvation’.Footnote 38 Both traditions refocus attention on the Law and its keeping, not on the serpent as the source of the cure.Footnote 39

The verses highlight an analogy between Jesus and the bronze serpent: both are ‘lifted up’. The identification of Jesus as the Son of Man has already been made (Jn 1.51),Footnote 40 and will be reiterated (Jn 8.28; 9.35-37; 12.32-34).Footnote 41 John makes belief in this lifting up of the Son of Man the basis for receiving ‘eternal life’.

While ‘lifting up’ has frequently been identified with the Crucifixion, this identification does not exhaust its full range of meaning.Footnote 42 The ambiguity of ‘lifted up’ also stresses the idea of benefit, as the Greek hypsoun/hypsousthai may include a positive meaning: of being exalted.Footnote 43 It thus may include both the notions of Crucifixion and ‘return to the Father in glory’.Footnote 44 This allows Jesus’ ‘lifting up’ to be a paradox: his debasement marks his exaltation or glorification.Footnote 45

Objections have been brought against this double identification of ‘lifting up’. Thus, J. Harold Ellens argues that the motif reflects only the exaltation of Jesus and his heavenly status. His argument is essentially that details of the Crucifixion are absent:

What can and must be said is that the brass serpent was redemptive in the story of Moses because it was believed to be the symbol of divine salvation from snake bite. It was not alive. It was not lifted up to be killed. It was not salvific because it was a substitutionary atonement. It was not sacrificed for the people. The key issue in being healed by the brass serpent was to believe in it enough as God’s instrument, so as to look at it in faith, with expectation, and not ignore it.Footnote 46

At the heart of this critique lies the premise that the details between the two events cannot be correlated exactly, and that John might not have the imagination to use the event creatively: it looks dangerously as if only a direct copying would be legitimate. Nothing apparently may be added to the Numbers account. Details from Jesus’ later fate simply are ruled out; an oddity when the passage is obviously being reinterpreted to refer to something other than its original story. The importing of ‘substitutionary atonement’ risks including an anachronistic theological term, or, at least, one which is neither demanded by the text, nor may even have been intended by the author, as a vital component of the reading. This is a rhetorical rather than a critical flourish: Pelion has been piled on Ossa.

However, even the mentions of Daniel, Jesus and his identification as the Son of Man add details to the Numbers account. So, the question is not whether such details may be added, but which the interpreter chooses to add. Ellens feels free to add material he considers already present in Jn 1.51, which is drawn from Genesis, Daniel and 1 Enoch.Footnote 47 These allow a reading about the exalted Son of Man alone. A significant point is retained: it is the lifting up of the Son of Man that matters, not just any old ‘lifting up’.Footnote 48

However, conspicuously absent from Ellens’ reading is any acknowledgement of the hypsoun/hypsousthai traditions found in Isaiah, which describe the Suffering Servant (Isa. 52.13 LXX) and are combined with the vocabulary of exaltation. This might equally have informed a reading which drew on the Jewish Scriptures, not least because Isaiah 52−53 are known to the gospel, and likely alluded to here and on a number of other occasions.Footnote 49 The potential inclusion of suffering in John’s understanding of the Son of Man would mark a departure from 1 Enoch, which does not include the suffering theme in its adaption of Isaiah.Footnote 50 However, there is no requirement that the evangelist was bound to follow the theology of 1 Enoch to the letter.

Nor is there any rule which states that echoes from different scriptures may not be conflated in a text interpreting Numbers 21 afresh, as Ellens’ own inclusion of Daniel 7 admits. Nor need these be limited to a single text. Indeed, other NT writers are even able to combine texts from different sources in what are presented as quotations: it is a recognized practice.Footnote 51 Additionally, it might be asked whether readers of the gospel might have prior knowledge of Jesus’ fate through which they might interpret this and the other passages which refer to the lifting up of the Son of Man (Jn 8.28; 12.32−34), and the degree to which they might also be aware of the treatments in the Synoptic traditions, which include the ‘suffering Son of Man who will be killed’.Footnote 52 This need not demand a scenario in which John derives from these gospels and their traditions, but simply a shared environment in which the various traditions emerge, and in which materials might be adapted creatively when transmission permitted redaction.Footnote 53

Ellens’ last point (that it is faith which ultimately matters) is echoed by others such as Andreas Köstenberger, even while recognizing the paradox of Crucifixion and exaltation.Footnote 54 Yet, this privileges the response of the believer over the event which makes such a faith possible, and appears deeply un-Johannine, given the evangelist’s stress on the writing of the gospel, and its record of what occurred as the basis for faith (Jn 20.30−31). The relationship between event and faith is causal: faith depends on the event. This admits that the event may be more or equally important to the response of faith: a sine qua non. Additionally, such matters must be connected to the gift of the Spirit, of which the crucifixion is identified as a ‘prerequisite’ in John 3, and brought to the fore, for example, in Jn 7.39.Footnote 55

The reading which uses the motif of ‘raising up’ to connect crucifixion and exaltation is to be retained. It gives the believer, or reader, confidence and hope because it is based on an event that has already taken place by the time of reading. John does not base hope on propositions about God, but roots them firmly in the past events which he describes. The gospel, in its received form, goes even further, making these claims witnessed by the Beloved Disciple its fons et origo (Jn 21.24). These provide the stuff which makes confidence in Jesus’ identity and promises sure – not speculation, or mythic imagery alone. They also, however, remind the reader of the need of faith or belief in these events to receive eternal life. It is this element that will come to the fore when the question is asked: how does one look to the bronze serpent for ‘having eternal life’ today? The attitude of faith must be focused on Christ, the bronze serpent, ‘lifted up’.

One other detail reveals the suitability of the image to point towards abuse, trauma and healing by setting, respectively, context and the ambiguity inherent in the salvific process: that the ‘lifting up of the Son of Man’ takes place in the wilderness.

The imagery of the wilderness in Numbers sets the scene in two ways:

First, it supplied the concept of Jesus’ journey from above to the earth and his return above to the Father. Second, it provided a paradigm: the journey of Jesus’ followers through the wilderness of life, and drinking ‘living water’ that provides eternal life. Thus, Jesus’ followers were to perceive that Jesus’ way led to the necessity of the cross on which Jesus was exalted like a serpent (the symbol of new life) and from which he was freed to return to his Father.Footnote 56

However, the narrative flow of the gospel itself may add further details to the generic wilderness motif. It describes specific harmful behaviours. Thus, the immediate point of reference is Golgotha (Jn 19.17), outside the city walls (Jn 19.20, Heb. 13.12).Footnote 57 However, the events which precede this further delineate Jesus’ wilderness experience. They include both political and religious institutional failure. Thus, the Jerusalem authorities, notably Annas and Caiaphas (e.g., Jn 11.49−53; 12.43; 18.13−14), preside over a flawed judicial process which prioritizes expediency, and fail – in the evangelist’s view, ironically (Jn 11.51) – to be cognizant of the movements of God in their own midst: ‘those who deny Jesus are really concerned with human affairs rather than the things of God’.Footnote 58 Pilate, outplayed by those whom he is meant to rule (Jn 19.12), vacillates and abrogates his responsibilities, thus revealing the arbitrary nature of the Roman law he dispenses: neither truth (Jn 18.38) nor justice (Jn 19.6) is served:

He typifies what happens when a hollow ideology is put into practice by those who hold real power, and when a political regime ceases to care for those who live under its authority.Footnote 59

His fate also shows how even his disciples add to his trauma: the one who hands him over (Jn 12.6; 13.21−30; 18.1−8) and the others who desert him (Jn 13.36-38; 18.15-18, 25-27). Jesus, the victim, is traumatized by the ‘church’, the ‘state’ and even friends, as may happen to victims of both trauma and abuse in modern settings. Jesus crucified and exalted, the bronze serpent ‘lifted up’, offers eternal life to those in the wilderness. He is all of pharmakos (victim), pharmakon (medicine, poison), and pharmakeus (sorcerer or magician). If this last point sounds startling, it is likely because of a post-Enlightenment discomfort with terms like magician, thaumaturge and even healer being used of Jesus.Footnote 60

That said, a case needs to be made for the symbol of the serpent to include ideas like healing or curing: such concepts should not be simply imported from contexts elsewhere in antiquity which connected serpents and healing. The gospel has its own lexical field or semantic domain, and we cannot assume that it automatically embraces concepts like healing or curing, even if these are prominent in formative interpretations like the Jewish Scriptures. Extant symbols and concepts may be re-accentuated to fit with the objectives of a new ideology or worldview.

John’s preferred term for the results of gazing on the serpent is ‘to have eternal life’ (Jn 3.15), his preferred term for a superior mode of existence, distinguishable from natural life as now lived.Footnote 61 Might this include hopes which include healing and curing? The short answer is affirmative. ‘Eternal life’ is, after all, not restricted to a post-mortem existence. John 3.7 has already spoken of the need ‘to be born from above/anew’. The gospel is shaped by an inaugurated eschatology, which implies that the transition into ‘having eternal life’ is already a reality for the believer, albeit one that may be lost. The instances of healing which occur in the gospel show that life and healing are linked, as in the healing of the centurion’s son (Jn 4.46−54).Footnote 62 The healing of the paralytic (Jn 5.1−25; 7.23) shares a pattern familiar also to the Synoptics: an ab minore ad maius or qal wahomer construction, which indicates that the ability to heal indicates Jesus has the power to grant eternal life.Footnote 63 The same may well hold for the man born blind (Jn 9.1−40).Footnote 64 If Jesus can heal, he can also give eternal life. This connection of ideas suggests that, for John’s Gospel, the language of healing may be more appropriate than that of curing. Eric Manuel Torres usefully distinguishes curing and healing, by noting that a cure may focus on the physical or biological,Footnote 65 whereas healing has a broader remit, encompassing ‘the psychological, social, communal, familial, emotional and spiritual levels of the person, and even, at times, the environmental level’.Footnote 66

It is ‘a holistic transformative process; it is personal; it is innate or naturally occurring; it is multidimensional; and it involves repair and recovery of mind, body, and spirit’.Footnote 67

Torres notes that Christian concepts of healing must add a further dimension: redemption in Christ, effected by a relationship with him.Footnote 68 Additionally, the healing which comes from Christ gives ‘eternal life’ not ‘this life in perpetuity’. At no point does John view the physical restoration and preservation of the current modus vivendi of the believer as the outcome of Jesus’ life and work. The raising of Lazarus is not a paean to resuscitation, but an anticipation of resurrection, which entails a higher order of existence.Footnote 69

John is not alone: both Paul and the seer of Revelation could adopt magical/medical imagery from their contexts, Judaic or Graeco-Roman, without worrying that this compromised or tainted their depiction of Jesus.Footnote 70 This practice still holds good. African Christians may adopt the paradigm of Jesus as ‘traditional healer’ to contextualize his significance as the true healer.Footnote 71

The serpent provides and image which might be usefully applied to address situations of trauma today. The two verbs suggest two spheres of action: raising and gazing.

Raising the Serpent Today

The experience of trauma within the church resonates both with the account in the gospel and the Jewish Scriptures which inform that narrative. The Exodus narrative starts in hope: Israel sings and rejoices at deliverance from Egypt (Exod. 15.1-22). They are God’s chosen and special people. But, the rot sets in: the journey through the wilderness is marked by complaints about food and drink (Exod. 16.1–17.7), by power struggles (Lev. 10; Num. 12.1-16; 14.1-12; 16.1-50), and even by overt idolatry (Exod. 32.1-35): all within God’s people, and all bringing trauma both to the involved parties and the people as a whole. This depiction of God’s chosen people as one which is far from perfect should be the starting point for ecclesiology. The church in the here and now is not a gathering of those who are perfect: it is of the present age as much as of the age to come, it is the church militant, not the church triumphant, it is on earth, but not yet in heaven. The first step in adopting the image of the serpent is to consider the theology and practices of the church that might constitute the raising of the serpent.

In the context of abuse, it is the place where abuse has happened, still happens and, regretfully, will continue to happen. As a first step this tragic reality must be recognized, but never simply accepted. However, even doing this simply is a fraught business. Let us consider a simple example from Australia: in the wake of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, many churches and places of worship display posters advising their commitment to addressing abuse, and giving contact numbers of designated bodies to whom allegations and reports should be addressed. Such notices are meant to instil a sense of safety and security. However, they might provoke a very different response. For some, they are reminders that they are victims of abuse themselves, and this does not always elicit a positive set of responses. In extreme cases, such a trigger may risk re-traumatizing a victim.

Also important is that ministers, lay and clerical, recognize their own limitations. Addressing any form of trauma demands a specialist knowledge which may well exceed the training and formation received in seminaries or theological colleges. Part of the wisdom of those ministering to the traumatized should be a recognition of their own limitations, which needs to be supplemented with the knowledge to know how best to refer victims of trauma to specialists who may properly address their needs. None of which is to say that ministry of word, prayer and sacrament are alien to a therapeutic referral process, but simply to recognize that ministers need to be aware that aspects of a healing ministry may be better handled by others. It begins by recognizing the need for a trauma sensitive theology which

flows in the service of trauma survivors who are congregation members and clergy who desire to provide supportive, stabilizing, grace-filled presence to persons and communities impacted by trauma. Trauma-sensitive theology is a theoretical lens, ethical commitment, and guide for praxis that extends in most areas of pastoral care, practical theology, pastoral counseling, liturgy, homiletics, and care for souls, minds, and bodies.Footnote 72

A focus on trauma then recognizes that pastoral care should be committed to addressing four basic phenomena:

the priority of bodily experience, full acceptance of trauma narratives, natural given-ness of human psychological multiplicity, and faith in the robust resiliency of trauma survivors.Footnote 73

The healing of trauma is not, therefore, restricted to therapeutic models. There is a place for any or all of prayer, meditation, reflection, liturgy and sacraments in transforming the experience of the sufferer. However, the handling of word and sacrament may need some refinement. Some varieties of Christianity, as already pointed out, dwell on theories of atonement which are heavily, if not exclusively, dependent on correlating sin with substitution.Footnote 74 The sense of personal worthlessness on which such theories lie may be harmful rather than healing to the victim of trauma, suggesting subtly that somehow they deserved, contributed to, or enabled the abuse which has caused their trauma. It may be a theological truism to state that all stand in need of redemption, but it does not follow that all are always responsible for the evils which they suffer. After all, is not the whole study of theodicy predicated on the understanding that bad things may happen to those who do not deserve them?

Treating the bronze serpent as an example of restorative justice may be of more help to the traumatized than drawing on substitutionary theories, as the basis for pastoral care. Restorative justice is

a process in which all the stakeholders affected by an injustice have the opportunity to discuss the consequences of the injustice and what might be done to put them right.Footnote 75

Its parameters are well described by John Braithwaite:

The prescriptive normative content of restorative justice is therefore rather minimalist – non-domination, empowerment, respectful listening and a process where all stakeholders have an opportunity to tell their stories about the effects of the injustice and what should be done to make them right. There is a lot of other normative content to restorative justice. For example, most restorative justice advocates would see forgiveness, apology, remorse for the perpetration of injustice, healing damaged relationships, building community, recompense to those who have suffered, as important restorative justice values. But there is no prescription that these things must happen for the process to be restorative justice.Footnote 76

Allison R. deForest sees the serpent as exemplifying this pattern:

Restorative justice seeks to heal all parties involved in an offense: victims, offenders, and communities. It does this by considering three basic conceptions. The first, encounter bringing all ‘stakeholders’ – offender, victim, and other affected members of a community − together in various configurations of a mediated conversation to discuss not only what happened, but what contributed to it and what resulted from it. In John’s Gospel, one is confronted with one’s own offense through Jesus as the serpent (John 3:14). Seeing God in the incarnate Jesus, crucified because of humanity’s rejection, yet risen and ascended, leads human offenders to confront their offense and their victim in order to find healing.Footnote 77

Whether or not such a process is effective will ultimately depend on the readiness of the different protagonists to gaze at the serpent.

Gazing at the Serpent

The symbol of the serpent has identified three groups involved in a quest for restorative justice. Each has to gaze on the serpent from a different perspective.

When the church or its officer has been the abuser, a rethinking of accepted pattern of dealing with justice and forgiveness. A dominant matrix is one in which the church and its office bearers are considered to be the mediators of forgiveness. In patterns like those seen in Mt. 16.18−19, 18.18-19; Jn 20.23, the church and its clergy in particular, seem to hold the power to forgive and effect justice. However, when it is the church and its officers who have been the sources of trauma, such a modality, which leaves forgiveness, justice and healing in their hands, is lopsided. It fails to empower their victims. It is compromised as a means of restorative justice. What is needed in this case is a different approach to the mediation of justice and forgiveness.

Fortunately, an alternative pattern is found elsewhere in the Gospels: Mt. 6.23-26 may be read as a reminder of the need to be reconciled to victims of misbehaviour as a preliminary to right worship. This demands both a recognition of being at fault, and of surrendering the authority to control the process of forgiveness: it should involve a deeply kenotic response to tragedy.Footnote 78

Ultimately, it must embody the hope that such actions are nothing less than a gospel imperative. It is not being asked to gloss over harsh realities in the name of some cosy ‘happy ever after’, but to embrace the fact that new life and restoration have come at a cost. It must be prepared to put aside its own feelings in the interest of reaching a just and fair conclusion in which reconciliation and restoration, not retribution, are achieved. The all too human tendency to pick sides, and keep them, needs to be abandoned. It may be particularly hard in close-knit communities where loyalties run deep, and where the achieving of justice may appear to demand their abandonment. The wider community must be supportive of the quest for restorative justice, gaining confidence from its focus on the serpent: the Crucified and exalted Jesus. It must not pretend that the church does this, usurping his rightful place.

When the church is identified as an ‘abusive healer’, the trauma victim recognizes that its presence in a healing process is double-edged. Here the geography of the serpent intrudes. If the allegory of the Serpent is unpacked, the following schema emerges: the victim as the one bitten, the church as the desert (where the victim is bitten), but Christ as the lifted serpent who heals. It is crucial that the church at this point avoids identifying itself with the serpent, despite its claim to be Christ’s mediator or agent.

Christians may perform supportive roles. Friends and colleagues may be those who point out to victims of trauma that their behaviour has changed, that they are exhibiting signs of trauma in their thinking, speaking and acting. It should go without saying that engagements should be motivated by aim to help, to transform and to heal, and avoid judgmentalism and the perception of negative criticism. Behaviours that enhance trauma by stigmatizing, or seeming to stigmatize, it are counterproductive, no matter how well intentioned.

One of the first actions for trauma victims is to recognize that they are victims of trauma. This then leads to the recognition that this means that they behave or react in ways of which they are not aware. A response, for example, to a letter from a church figure involved in the aftermath of trauma, might include visceral reactions with any or all of physical, mental, emotional and spiritual elements. These may be severe, leading colleagues and observers to describe these as unusual, out of character or even paranoid. When victims are in such a situation it is vital that they simply admit this is the reality, but avoid standing in judgment of themselves. Even if they feel or recognize that their own decisions or actions may have contributed in some way, trauma is the result of the actions, accidental or intentional, of a variety of agents, intentionally or accidentally: ‘Bila mtu wa pili ugomvi hauanzi’ – ‘Without a second person a quarrel cannot start.’Footnote 79 Victims must not victim-shame themselves unnecessarily, and be made aware of this danger or temptation. Genuine awareness becomes the first step in healing. From this stems the pursuit of therapeutic and healing behaviours, some of which may need expert care and attention from qualified healthcare practitioners, as well as those disciplines which emerge from spiritual and liturgical practice. From this vantage point, victims are also encouraged to gaze on the serpent lifted up.

Here, Christian devotions and rituals may intrude in several forms, depending on the tradition in which the victim stands. For some, this may be focused on the reading of Scripture. For others, meditative practices such as an Ignatian contemplatio, in which:

He asks the one making the Exercises to recall ‘the history,’ ‘see the place,’ look at what the people in the story or picture are doing and listen to what they are saying.Footnote 80

Prayer of this kind is

centred on the word of God or on events which likewise mediate God to us, is a formative process. It can mould and change us in accordance with the word of God, and reach our innermost hearts, the most fundamental attitudes and dispositions which day by day give shape and colour to our lives. This form of imaginative contemplation helps people to put on ‘the mind of Christ’.Footnote 81

The bronze serpent scene itself (Jn 3.14) allows victims of trauma to imagine themselves within a healing process with Jesus present, or the exaltation of Jesus.

Sometimes an external focus might be adopted, using religious artefacts like icons, as in Catholic or Orthodox tradition:

The word icon simply means image. A religious icons [sic] is considered to be a soul window, an entrance into the presence of the Holy.

Icons serve as invitations to keep eyes open while one prays. It is prayer to just look attentively at an icon and let God speak.

The profound beauty of an icon is gentle. It does not force its way. It asks for time spent before it in stillness … gazing. More importantly it invites the one praying to be gazed upon by it.

One is invited to enter into the icon and come closer to the Holy One portrayed. Icons are a reminder of God’s unconditional love.Footnote 82

Adam Ján Figeľ’s icon of the bronze serpent from the Greek Catholic Church in Bratislava provides a modern example of the scene envisioned for this use.Footnote 83

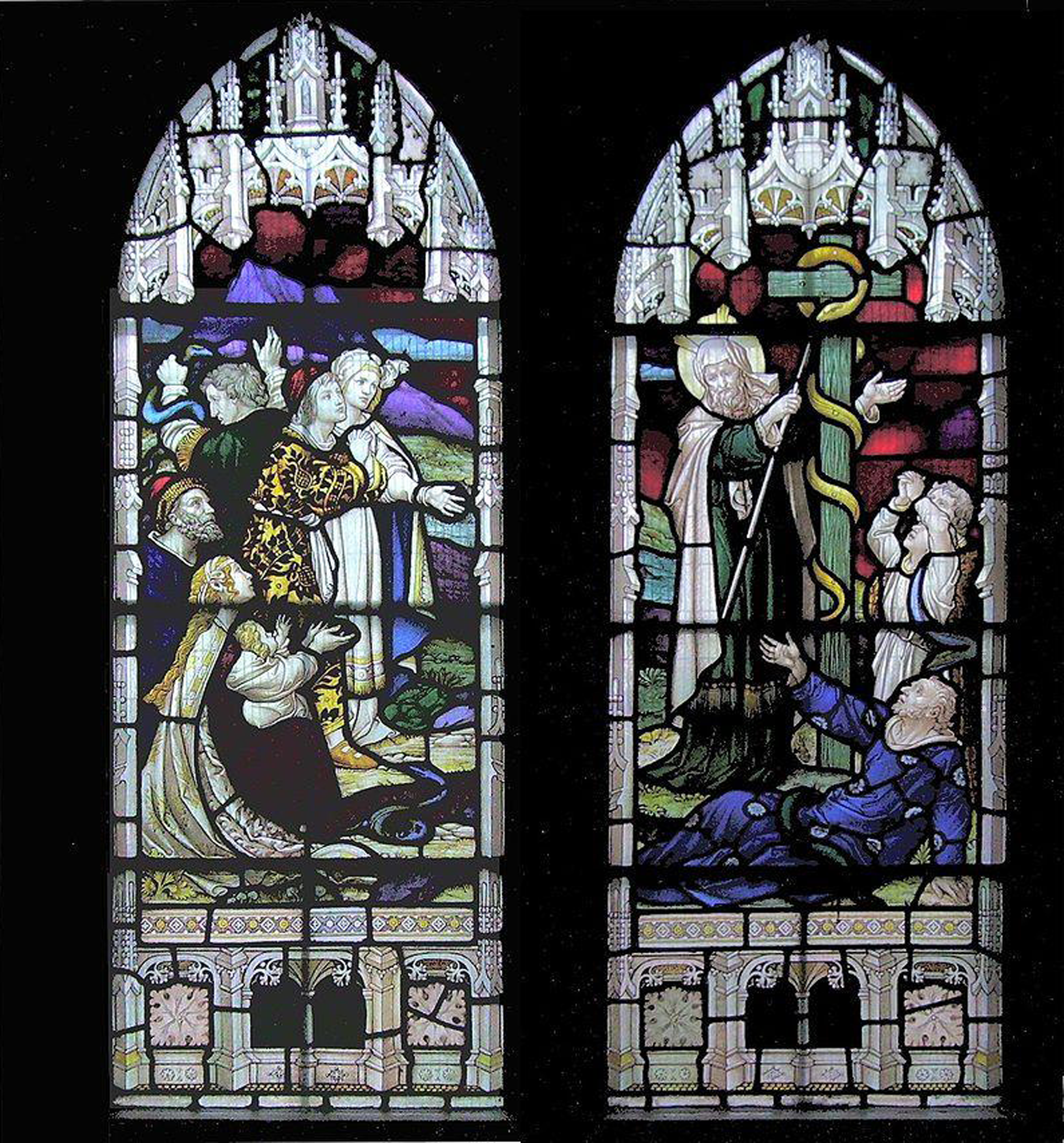

Not all Anglican churches are comfortable with the use of icons. Critical to the debate is whether they are to be included in the condemnation of idolatry (e.g., Exod. 20.4). Writers like Rowan Williams and Graham Kings have affirmed the value of their use, noting that icons point not to themselves, but to some holiness or reality beyond.Footnote 84 Support for this understanding is not universal.Footnote 85 For those comfortable with using icons or other religious art in this way, architecture may provide alternatives. A west end panel, a mosaic, in All Saints’, Margaret Street (London) depicts the bronze serpent.Footnote 86 St Mark’s Church, Gillingham, offers a stained-glass window (see Figure 1). All offer an external focus which expresses the pattern outlined above: a space (church/desert) where the victim of trauma may gaze on the Serpent/Christ.

Figure 1. Moses lifts up the brass snake in a photograph of the stained-glass window at St Mark’s Church, Gillingham.

Photo: Mike Young (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nehushtan#/media/File:MosesandSnake.JPG)

Conclusions

Those who have experienced trauma because of the church are highly likely to look askance at it as a source of healing. The bronze serpent, too, initially seems an unlikely source of healing, given our innate instinctive reaction to snakes. However, gazing on the serpent who becomes identifiable as the crucified and risen Christ becomes the means to eternal life. Enabling this gazing in faith through the provision of resources and rituals which allow the Risen Christ to heal allows those who have been wounded to overcome their initial repugnance at the church and be transformed as they look to him. The image also allows the church to remember its place solely as the space where a healing encounter with Christ may take place; it should also remember its own complicity in the creation of trauma, and strive intentionally to replace such behaviours with those which are genuinely life-giving.