The history of psychiatry contains many examples of unexpected discoveries that have reshaped both understanding and treatment of mental illness. Horace Walpole’s 1754 definition of serendipity as ‘making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things which they were not in quest of’ captures the essence of this process. In psychopharmacology, many transformative advances have followed this path, from early antipsychotics to more recent developments. These were not simply strokes of luck, but the result of clinicians recognising the value of unanticipated observations and pursuing them.

This recurring pattern raises questions about how scientific progress occurs and what conditions best support innovation. As Ban observed in his review of serendipity in drug discovery, a significant number of psychiatric medications were identified not through targeted design, but through attention to unexpected effects. Reference Ban1 Evidence-based medicine already incorporates a spectrum of evidence, from case reports to large trials, which means the task is not to pit observation against rigor, but to ensure that unusual findings are systematically recognised, assessed and developed.

Today’s clinical and research environments present both opportunities and obstacles for this kind of work. Standardisation has improved the quality and consistency of care, but the emphasis on structured assessments, adherence to treatment guidelines and time-limited clinical encounters can narrow the scope for noticing and exploring unexpected responses.

This paper reviews the historical role of serendipity in psychiatric discovery, and considers how to preserve its benefits in contemporary practice. We argue that serendipity is best understood as the meeting point of clinical attentiveness, interpretive skill and systems that make it possible to investigate anomalies. By fostering these conditions, psychiatry can remain open to the kinds of discoveries that have so often driven its progress.

Method

This is a selective narrative review intended to illustrate how serendipity has shaped psychiatric therapeutics and to sketch practical implications for clinical observation. We prioritised widely cited discovery cases (e.g. chlorpromazine, iproniazid/imipramine, lithium, benzodiazepines, clozapine, valproate, ketamine and psychedelics) drawn from landmark primary reports and peer-reviewed historical syntheses. Our aim is conceptual rather than exhaustive. Where accounts conflict or are partly anecdotal (e.g. reports of euphoria among patients with tuberculosis at Sea View Hospital), we note the contested status and, where possible, cross-reference primary sources and secondary narratives. This strategy inevitably introduces selection bias: well-documented and ultimately successful discovery stories are overrepresented, whereas negative findings, less dramatic trajectories and contributions from underdocumented settings are harder to capture. Our aim is therefore illustrative rather than exhaustive, and the examples reviewed do not encompass the full diversity of discovery pathways.

Results

Historical overview of serendipitous discoveries in psychiatry

The discovery of chlorpromazine

The identification of chlorpromazine’s antipsychotic effects stands as one of the most influential serendipitous discoveries in psychiatry. First synthesised in 1950 by Paul Charpentier at Rhône-Poulenc as part of a programme to develop new antihistamines, the compound was initially explored for its potential role in anaesthesia. Reference López-Muñoz, Alamo, Cuenca, Shen, Clervoy and Rubio2 Henri Laborit, a French military surgeon, noted that the drug induced what he described as ‘artificial hibernation’ in surgical patients – a state marked by calm detachment from their surroundings without loss of consciousness. Reference Laborit, Huguenard and Alluaume3

Intrigued by this striking effect, Laborit proposed that the drug might have applications in the psychiatric setting. Later that year, Jean Delay and Pierre Deniker at Sainte-Anne Hospital in Paris administered chlorpromazine to patients with psychosis, documenting marked reductions in agitation, hallucinations and delusions. Reference Delay and Deniker4 Through a series of careful clinical reports, they established chlorpromazine as an effective antipsychotic, heralding the beginning of the psychopharmacological era. Although initial clinical use remained limited, broader uptake followed commercial release as Largactil in France in November 1952, and US approval as Thorazine in May 1954. Reference Ban5

As Ban observed, the discovery of chlorpromazine was not the product of an understanding of schizophrenia’s underlying biology, but rather the recognition of unanticipated clinical effects. Reference Ban5 Its introduction transformed the treatment of severe mental illness and catalysed decades of research into the neurobiological mechanisms of psychosis. Concurrently, reserpine (derived from Rauwolfia serpentina) emerged as another early antipsychotic, with Nathan Kline’s reports proving instrumental in popularising its psychiatric application. Reference Kline6,Reference Kline and Stanley7

The antidepressant revolution: from tuberculosis wards to psychiatric clinics

The origins of modern antidepressant treatment offer another striking example of serendipity in action. In 1951, physicians treating patients with tuberculosis with the monoamine oxidase inhibitor iproniazid noticed unexpected improvements in mood and energy. Reference Selikoff, Robitzek and Ornstein8 At Sea View Hospital on Staten Island, contemporaneous reports described patients as unusually cheerful and active during treatment – accounts that quickly drew attention to the drug’s potential psychiatric uses. Reference Sandler9

Nathan Kline recognised the significance of these observations and undertook some of the earliest systematic trials, publishing a landmark report on iproniazid for depression in 1958. Reference Kline10 Around the same time, imipramine’s antidepressant properties were identified in an entirely different context. Developed as part of efforts to create a new antipsychotic, the compound was trialled by Roland Kuhn in Switzerland, who found it ineffective for schizophrenia, but strikingly beneficial for patients with depression. Reference Kuhn11 Imipramine’s chemical structure, derived from tricyclic scaffolds related to phenothiazines, illustrates that such discoveries often build on existing medicinal chemistry and prevailing theoretical models.

These breakthroughs emerged when depression was still poorly defined and widely viewed as resistant to treatment. Beyond offering effective therapies, they stimulated the development of new neurobiological accounts of mood disorders, most notably the monoamine hypothesis of depression. Reference Schildkraut12

Lithium: from urate experiments to mood stabilisation

The identification of lithium’s mood-stabilising properties by John Cade is another classic example of serendipity in psychiatry. Working in a small Australian hospital with minimal resources, Cade hypothesised that mania might be caused by a toxin present in the urine of patients with bipolar disorder. In testing this idea, he used lithium urate as a control in experiments with guinea pigs, expecting it to be physiologically inert. Instead, he observed a marked calming effect on the animals. Reference Cade13

This unexpected result prompted Cade to trial lithium in patients with mania, producing striking improvements and, in some cases, remission of symptoms. His 1949 report in the Medical Journal of Australia described substantial recoveries in an uncontrolled series, many in individuals who had been in-patients for extended periods. The importance of the finding was not immediately recognised, in part because of safety concerns following deaths in the USA from lithium used as a low-sodium salt substitute. Reference Shorter14

Lithium’s clinical value was firmly established only after Mogens Schou and colleagues in Denmark confirmed its efficacy in the 1950s. Reference Schou, Juel-Nielsen, Strömgren and Voldby15 This episode highlights a recurring feature of serendipitous discovery: initial observations often require sustained advocacy and rigorous evaluation before gaining acceptance. Today, lithium remains one of the most effective treatments for bipolar disorder, its origins a reminder of the importance of remaining attentive to unanticipated findings.

Benzodiazepines: from discarded compounds to anxiolytics

The discovery of benzodiazepines provides yet another illustration of how chance, coupled with persistence, can yield major therapeutic breakthroughs. In the 1950s, Leo Sternbach at Hoffmann-La Roche was tasked with developing new tranquillising agents to compete with meprobamate. After extensive testing of novel compounds with little success, a laboratory clean-up uncovered a shelved molecule labelled Ro 5-0690, which was nearly discarded. Reference Sternbach16

Instead of disposing of it, Sternbach chose to test the compound, and found it had pronounced sedative and muscle-relaxant properties. This molecule became chlordiazepoxide (Librium), the first benzodiazepine. The rapid development of diazepam (Valium) and other derivatives soon transformed the management of anxiety disorders. Reference Tone17

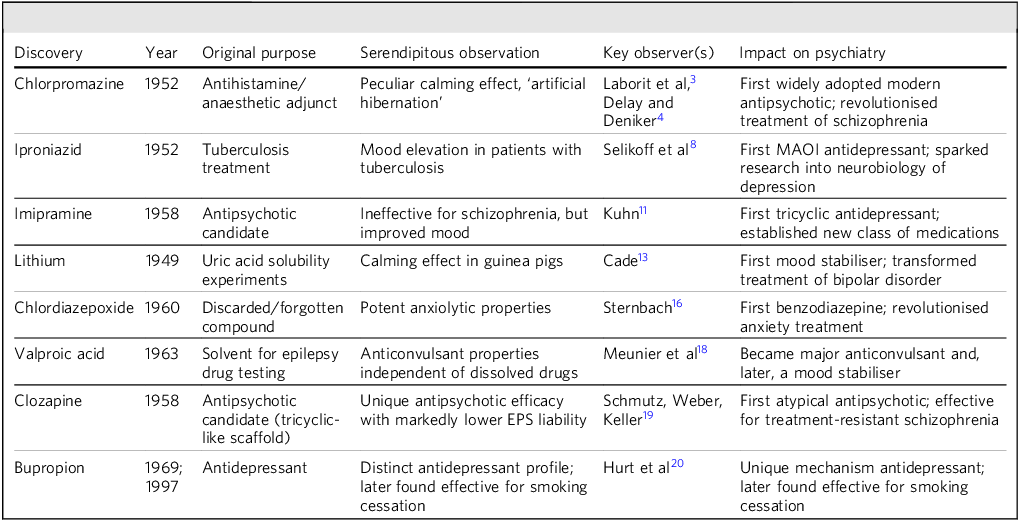

The benzodiazepine story highlights that serendipitous discoveries often hinge not only on unexpected observations, but also on the decision to pursue leads that may initially appear unpromising. Sternbach’s choice to investigate a forgotten compound ultimately led to one of the most widely prescribed classes of psychiatric medications. Other major serendipitous discoveries in psychiatry are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1 Major serendipitous discoveries in psychiatry

Clozapine was synthesised in 1958; early clinical observations appeared in the early 1960s. Reference Hippius19 EPS, extrapyramidal symptoms; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor.

The nature of serendipity in scientific discovery

Understanding serendipity in psychiatric discovery involves looking closely at both the conditions that allow such findings to occur and the mental processes within the observer that make their recognition possible. Roberts identified three essential elements in true serendipity: chance, sagacity and purpose. Reference Roberts21 Although chance is inherently unpredictable, the ability to recognise and act on an unexpected observation – sagacity – can be developed.

Louis Pasteur’s observation that ‘chance favors the prepared mind’ captures this idea. The psychiatrists and researchers behind major breakthroughs were not simply fortunate; they had the knowledge, observational acuity and intellectual flexibility needed to see the significance in unanticipated effects. Delay and Deniker’s recognition of chlorpromazine’s antipsychotic action, for example, depended on a refined understanding of psychiatric phenomenology and the capacity to distinguish its effects from simple sedation. In many cases, the observation was intelligible only because existing theory or chemical lineage had primed the observers – imipramine and clozapine, for instance, both shared tricyclic-like scaffolds that shaped expectations around the discovery.

Serendipity in psychiatry often followed what Merton (1957) described as the ‘serendipity pattern’: the encounter with an unanticipated, anomalous and strategically important finding that leads to the creation or extension of a theory. Reference Merton22 The observation that patients with tuberculosis on iproniazid developed euphoria was anomalous because it defied expectations about the mood of seriously ill patients, and strategic because it suggested a new approach to treating depression.

Social and institutional settings also influence the likelihood of such discoveries. As Campanario (1996) noted, environments that allow flexibility in research priorities and encourage the investigation of anomalies are more likely to benefit from serendipitous observation. Reference Campanario23 In psychiatry, the relatively unstructured nature of clinical work in the 1950s and 1960s, along with greater autonomy for clinician-researchers, likely supported the recognition and pursuit of unexpected clinical findings.

Beyond these conceptual accounts, recent work has sought to operationalise serendipity within psychopharmacology. López-Muñoz and colleagues, for example, have applied explicit criteria and a four-pattern taxonomy to classify the role of serendipity in the discovery of newer antidepressant drugs, distinguishing unexpected clinical observations from more rationally designed development programmes. Reference López-Muñoz, D’Ocón, Romero, De Berardis and Álamo24 Such operational approaches complement narrative histories and reinforce our central claim that serendipity reflects an interaction between chance events, prepared observers and the research systems within which they work.

Discussion

Contemporary challenges to serendipitous discovery

In contemporary psychiatric research and practice, several factors complicate the recognition and development of serendipitous observations. Many of these stem from advances that have otherwise improved clinical care and research quality, yet they can unintentionally limit opportunities for unexpected findings to emerge or be successfully pursued.

Standardisation and protocol-driven care

The shift toward evidence-based medicine and standardised treatment protocols has enhanced the overall quality and consistency of psychiatric care, but may have also narrowed the space for noticing unexpected treatment effects. Clinical guidelines and algorithms, designed to promote effective and reliable practice, focus attention on established interventions and anticipated outcomes. Reference Sackett, Rosenberg, Gray, Haynes and Richardson25 Although these tools are invaluable, they can inadvertently discourage clinicians from pursuing observations that fall outside predefined parameters. Notably, the evidence-based framework already accommodates exploratory signals such as case reports, case series, registries and pragmatic data; the key challenge lies in building explicit mechanisms that can move credible anomalies into structured investigation, rather than dismissing them as statistical or clinical noise.

Similarly, the use of structured diagnostic interviews and standardised outcome measures has improved diagnostic reliability and the monitoring of treatment effects, but may constrain the breadth of clinical observation. As Andreasen has argued, an emphasis on checklist-based assessment risks overlooking subtle phenomenological details that could yield important insights into mental disorders and their treatment. Reference Andreasen26

Time constraints and productivity pressures

Modern clinical practice is frequently shaped by time pressures that limit opportunities for detailed observation and reflection. Economic and administrative demands often require clinicians to see more patients in less time, reducing the likelihood that unexpected findings will be noticed or explored. Reference Mechanic27 In many settings, tightly constrained appointment lengths and insurance-driven efforts to reduce in-patient stays stand in marked contrast to the extended hospital observation common in the mid-20th century, leaving less scope for sustained, careful phenomenological assessment.

Research funding and design constraints

The organisation of modern research funding and clinical trial design can also constrain the scope for serendipitous discovery. Grant applications generally demand clearly defined hypotheses and predetermined outcome measures, leaving limited flexibility to follow unanticipated leads. Reference Ioannidis28 Large, randomised controlled trials remain essential for establishing efficacy, but their scale and rigidity mean they are less likely to detect rare or unexpected effects that might emerge in smaller, more adaptable studies or through attentive clinical observation. In addition, the high costs and regulatory demands of drug development create strong incentives for pharmaceutical companies to prioritise incremental modifications of existing compounds over riskier ventures into novel mechanisms suggested by unexpected findings. Reference Munos29 Although commercially understandable, this approach can result in missed opportunities for transformative advances.

One response to these constraints has been the development of innovative trial designs that may be particularly well-suited to evaluating signals arising from serendipitous observation. Adaptive platform and other master-protocol designs allow several candidate mechanisms, doses or combinations to be tested within a single overarching trial structure, adding or dropping arms over time as evidence accumulates. Rather than treating each new mechanistic hypothesis as a full standalone trial, these platforms can incorporate a novel arm based on an unexpected clinical signal, compare it head-to-head against relevant standards, and then either expand enrolment or close the arm according to prespecified decision rules.

Rapid-fail proof-of-concept programmes take a complementary approach by focusing on small, methodologically rigorous, early-phase studies that test whether a novel mechanism produces a clear signal on proximal targets (for example, pharmacodynamic biomarkers, task performance or short-term symptom change) before committing to larger, expensive phase 3 trials. In psychiatry, where many mechanistically promising agents have failed late in development, rapid-fail designs offer a way to recognise serendipitous observations while limiting opportunity cost and patient burden: signals that do not replicate or that lack convincing mechanistic engagement can be discontinued quickly, whereas promising effects can be escalated into larger, possibly platform-based trials for more definitive evaluation.

Specialisation and fragmentation

The growing specialisation within psychiatry and neuroscience has advanced understanding within specific domains, but may also limit the cross-disciplinary perspectives that have historically contributed to serendipitous discovery. Many past breakthroughs arose from clinicians whose work spanned different areas of medicine – surgeons noting psychiatric effects of anaesthetics, or internists observing mood changes in patients treated for tuberculosis. Today, the clearer separation between specialties may reduce opportunities for such cross-fertilisation of clinical observations. Reference Fava30

The argument for cultivating serendipity in clinical psychiatry

Despite these challenges, there are compelling reasons to actively cultivate conditions that support serendipitous discovery in contemporary psychiatry. The history of psychiatric therapeutics demonstrates that many fundamental advances emerged not from hypothesis-driven research, but from careful observation of unexpected phenomena. As we face the limitations of current psychiatric treatments and the need for novel therapeutic approaches, maintaining openness to serendipitous discovery is more important than ever.

The limits of rational drug design

Although rational drug design grounded in disease mechanisms has driven important progress in many areas of medicine, its impact in psychiatry has been modest. Despite decades of work on the neurobiology of mental illness, most current psychiatric medications belong to chemical classes first identified through serendipitous discoveries many decades ago. Reference Hyman31 The repeated failure of rationally designed agents in clinical trials underscores how incomplete our understanding of psychiatric neurobiology remains. The National Institute of Mental Health’s Research Domain Criteria initiative aims to move beyond traditional diagnostic categories, towards a dimensional view of psychopathology, Reference Insel, Cuthbert, Garvey, Heinssen, Pine and Quinn32 offering a valuable framework for future research. Yet the limits of existing neurobiological models, combined with the potential rigidity of any predefined framework, underline the importance of remaining attentive to unexpected clinical observations, which can yield critical insights and open new therapeutic avenues.

Caveat: when serendipity misleads

The historical record also contains examples where promising signals from early open-label studies or case series failed to hold up in larger randomised trials. Instances such as the off-label use of certain agents as mood stabilisers, or adjunctive anti-inflammatory treatments that later produced mixed or null results, Reference Deakin, Suckling, Barnes, Byrne, Chaudhry and Dazzan33 highlight the importance of disciplined follow-up. Preregistration, transparent reporting and rigorous evaluation are essential to distinguish genuine therapeutic signals from findings that may ultimately reflect noise.

The value of phenomenological observation

Detailed phenomenological observation, which was central to many historical serendipitous discoveries, continues to hold value in modern psychiatry. As Parnas and colleagues have noted, close attention to subjective experience and subtle behavioural features can uncover dimensions of mental illness that standardised assessments may overlook. Reference Parnas, Sass and Zahavi34 Such observations can point to novel treatment targets or reveal unanticipated effects of existing interventions.

Personalised medicine and individual variation

The move towards personalised or precision medicine in psychiatry makes it increasingly important to attend to unexpected individual treatment responses. As the heterogeneity within psychiatric diagnoses becomes clearer, and as we better understand the complex interplay of genetic, environmental and treatment-related factors, careful observation of individual variation takes on greater significance. Reference Ozomaro, Wahlestedt and Nemeroff35 An apparently anomalous response in one patient may, in fact, signal a distinct illness subtype or reveal a biological pathway that could shape future therapeutic strategies.

The expanding role of pharmacogenomics in psychiatry demonstrates how responses once regarded as idiosyncratic can have systematic explanations with direct clinical relevance. Serendipitous recognition of unusual drug effects in single patients has led to the identification of genetic polymorphisms that influence drug metabolism and treatment response. Reference Müller, Kekin, Kao and Brandl36

A framework for encouraging serendipitous observation

To make use of serendipity’s potential in advancing psychiatric understanding and treatment, we propose a multi-level framework spanning individual, institutional and systemic factors. The goal is to preserve the strengths of standardised, evidence-based practice while maintaining a readiness to recognise and explore unexpected findings.

The individual level: cultivating prepared minds

At the level of the individual clinician, several approaches can increase the likelihood of recognising and acting on serendipitous findings.

-

• Phenomenological training: Psychiatric education should place greater emphasis on detailed phenomenological observation alongside structured assessment. As Stanghellini and Broome note, teaching clinicians to attend to patients’ subjective experiences and subtle behavioural features can reveal aspects of illness not captured by standardised interviews. Reference Stanghellini and Broome37 This includes grounding in descriptive psychopathology that extends beyond DSM criteria and draws on the broader tradition of psychiatric phenomenology.

-

• Reflective practice: Creating space for reflection, even within busy services, enables clinicians to notice patterns and anomalies that might otherwise pass unnoticed. Regular case discussions that allow open-ended exploration of puzzling or unexpected observations can nurture curiosity. As Schön described, the ability to reflect both in action and on action is central to professional growth and discovery. Reference Schön38

-

• Interdisciplinary exposure: Maintaining awareness of developments in related fields – such as neurology, immunology and endocrinology – can help psychiatrists recognise connections with potential clinical significance. Historically, many discoveries in psychiatry came from individuals applying insights from other medical domains. Regular interdisciplinary meetings and collaborations can help sustain such cross-pollination.

-

• Documentation practices: Encouraging clinical records that capture more than checkbox symptoms, and include unexpected or seemingly tangential observations, creates a resource for identifying patterns over time. Although electronic health records are often criticised for their limitations, they could be adapted to support free-text entries alongside structured data. Reference Cimino39

The institutional level: creating supportive environments

Healthcare institutions can play a central role in creating environments that support serendipitous discovery.

-

• Protected time for observation: Institutions should recognise the importance of detailed clinical observation by building protected time for it into clinical schedules. This could include longer initial assessments, dedicated time for complex case discussions or opportunities for clinicians to follow up on unexpected findings. As Gabbay and le May observed in their ethnographic work, the informal knowledge gained through careful observation can be as valuable as formal research evidence. Reference Gabbay and le May40

-

• Flexible research support: Mechanisms that allow rapid pursuit of unexpected clinical leads can help translate serendipitous observations into structured inquiry. Examples include small grant schemes for pilot studies, streamlined ethics review processes for observational research and collaborations with basic scientists to explore potential mechanisms. Reference Woolf41

-

• Culture of inquiry: Institutional leadership can promote a culture that prizes curiosity and the exploration of anomalies. This might involve celebrating serendipitous findings from the organisation’s history, shielding clinicians from productivity pressures when they pursue such leads, and establishing regular forums for sharing puzzling cases or unusual treatment responses.

-

• Database infrastructure: Robust clinical data systems can make it easier to detect unusual treatment responses or other unexpected patterns. Integrating natural language processing and machine learning into clinical databases could help identify anomalous patterns in narrative notes, whereas positive-signal pharmacovigilance systems could systematically record unexpected benefits alongside adverse events. Reference Jensen, Jensen and Brunak42

The systemic level: policy and research infrastructure

At the broader systemic level, several measures could help create an environment more conducive to serendipitous discovery.

-

• Funding mechanisms: Research agencies should develop dedicated programmes for investigating unexpected findings. The National Institutes of Health’s R21 exploratory grants offer one example, but additional schemes tailored specifically to serendipitous observations could add value. As Heinze et al found, funding structures that allow flexibility and tolerate risk are associated with more innovative outcomes. Reference Heinze, Shapira, Rogers and Senker43 Embedding such mechanisms within learning health systems could speed the path from initial observation to formal evaluation.

-

• Regulatory flexibility: In addition to maintaining necessary safety standards, regulatory bodies could create streamlined pathways for the rapid investigation of unexpected therapeutic effects from approved medicines. The US Food and Drug Administration’s expanded access programmes offer a precedent, but further targeted mechanisms for studying serendipitous findings could accelerate their translation into practice. Reference Darrow, Sarpatwari, Avorn and Kesselheim44

-

• Publication venues: Establishing reputable outlets for well-documented case reports and case series describing unexpected treatment responses could improve the dissemination of serendipitous observations. Although such reports sit low in the evidence hierarchy, they have historically been central to recognising new therapeutic possibilities. Journals focusing on phenomenological observation and unexpected clinical findings, alongside structured registries for recording unexpected benefits, could help restore this role. Reference Vandenbroucke45

-

• Training reform: In addition to the psychiatric training reforms already discussed, medical education should explicitly address the role of serendipity in discovery, equipping clinicians with the skills to recognise and follow up on unexpected observations. This might include teaching the history of medical breakthroughs, philosophy of science and research methods suited to investigating serendipitous effects. Reference Goldacre, Heneghan, Mahtani and Godlee46

Case studies: contemporary examples of serendipity

To demonstrate that serendipitous discovery remains possible in contemporary psychiatry despite the constraints outlined above, we highlight a few recent examples.

Ketamine and rapid antidepressant action

The recognition of ketamine’s rapid antidepressant effects offers a contemporary example of serendipity reshaping psychiatric thinking. For years, anaesthesiologists had noted that some patients reported improved mood after ketamine anaesthesia, but these accounts were largely regarded as incidental side-effects. It was only when Berman and colleagues conducted a small, controlled trial based on such observations that ketamine’s striking, rapid antidepressant action was formally demonstrated. Reference Berman, Cappiello, Anand, Oren, Heninger and Charney47

This finding has transformed approaches to depression, overturning the long-standing assumption that antidepressants require weeks to take effect, and stimulating intensive investigation into glutamatergic pathways in mood regulation. The subsequent development and US Food and Drug Administration’s approval of intranasal esketamine for treatment-resistant depression exemplifies how a serendipitous clinical observation can be successfully translated into an approved therapeutic option. Reference Daly, Singh, Fedgchin, Cooper, Lim and Shelton48

Anti-inflammatory approaches to depression

Reports that some patients with autoimmune disorders experienced unexpected improvements in mood or psychotic symptoms when receiving anti-inflammatory treatments have fuelled growing interest in the role of inflammation in mental illness. Although links between inflammation and psychiatric disorders had been suggested for decades, it was often these unanticipated clinical improvements during immunological treatment that prompted systematic research. Reference Miller, Haroon, Raison and Felger49

Such observations have led to clinical trials of anti-inflammatory agents for conditions such as depression, opening potential new avenues for treatment. Reference Kappelmann, Lewis, Dantzer, Jones and Khandaker50,Reference Bai, Guo, Feng, Zhang, Zhang and Liu51 That these findings arose from attentive monitoring of patients undergoing therapy for non-psychiatric illnesses highlights the enduring value of cross-disciplinary clinical observation.

Psychedelic renaissance

The resurgence of interest in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy is partly rooted in serendipitous observations from clinicians and researchers who noted unexpected, lasting benefits in research participants and patients who had used these substances. Although studies in the 1950s and 1960s had suggested therapeutic potential, the work was largely discontinued for political and social, rather than scientific reasons. Over time, persistent anecdotal accounts of benefit led contemporary investigators to revisit these findings and test them systematically. Reference Nichols52 Recent controlled trials have confirmed aspects of the early reports, indicating possible breakthrough treatments for conditions such as treatment-resistant depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Reference Carhart-Harris and Goodwin53 In parallel, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted therapy has shown efficacy for post-traumatic stress disorder in randomised trials. Reference Mitchell, Bogenschutz, Lilienstein, Harrison, Kleiman and Parker-Guilbert54 This revival demonstrates how revisiting research abandoned for non-scientific reasons can open valuable therapeutic possibilities.

Future directions and recommendations

As psychiatry advances into an era of precision medicine and biological psychiatry, remaining open to serendipitous discovery will be both more difficult and more essential. We offer the following recommendations for fostering conditions conducive to serendipitous discovery while maintaining scientific rigor.

Integration with precision medicine

Rather than viewing attention to serendipitous observation as competing with precision medicine approaches, we should recognise their complementary nature. Unexpected treatment responses in individuals may reveal previously unrecognised biological subtypes or mechanisms. Building infrastructure to systematically capture and investigate such observations could accelerate precision medicine efforts. Reference Collins and Varmus55

Technology-enhanced observation

Digital health technologies, including smartphone applications and wearable devices, offer new ways to identify unexpected patterns in symptoms or treatment responses. Practical steps to enable this include the following.

-

• Electronic health records (EHR) outlier detection: Developing anomaly-detection models using natural language processing to flag unusual response trajectories, rapid-onset effects or distinctive improvement patterns for clinical review.

-

• Positive-signal pharmacovigilance: Adapting adverse event reporting systems to capture unexpected benefits, using structured fields and allowing for patient-reported input.

-

• Single-patient (N-of-1) and micro-randomised trials: Incorporating lightweight, consent-based individual experiments within routine care to rapidly test emerging signals.

-

• Pragmatic trial ‘sidecar’ fields: Adding short free-text and checklist options to standard outcome workflows to log unexpected findings prospectively.

-

• Rapid institutional review board pathways: Creating fast-track ethical review processes to study emerging clinical signals promptly, while safeguarding safety, privacy and transparency.

Machine learning can support novelty detection, but these tools should be designed to highlight and triage unexpected positive outcomes rather than focus solely on confirming anticipated patterns. Reference Torous, Onnela and Keshavan56

Global collaboration

Establishing international networks for sharing and investigating serendipitous observations could help accelerate discovery. Variation across populations and treatment settings may reveal different unexpected effects, and coordinated investigation can aid in distinguishing genuine signals from background noise. Existing models, such as the World Health Organization’s pharmacovigilance programmes, could be adapted to capture and evaluate positive, unanticipated outcomes. Reference Lindquist57

Ethical considerations

In promoting attention to serendipitous observations, it is essential to address the accompanying ethical considerations. Patients should be made aware when treatments are being offered on the basis of serendipitous findings rather than evidence from controlled trials. Systems designed to investigate such observations must safeguard patient privacy while still enabling meaningful discovery. The principle of beneficence supports pursuing unexpected findings that may offer clinical benefit, but this pursuit must be balanced with careful evaluation of safety and efficacy. Reference Emanuel, Wendler and Grady58

Taken together, the future imperatives for the field are to train clinicians as prepared observers of anomalous responses, to equip services with technology-enabled tools that can capture and aggregate unexpected signals, and to ensure that emerging leads can flow efficiently into flexible trial platforms. Combining enhanced phenomenological training, digital phenotyping and EHR-based anomaly detection with adaptive platform and rapid-fail proof-of-concept trial designs would allow promising observations to be tested more quickly, while minimising patient burden and opportunity cost. Framing serendipity in this way as a system-level responsibility, rather than an individual virtue alone, offers a more concrete roadmap for research and practice.

Making space for the unexpected

The history of psychiatric therapeutics shows that many of the field’s most effective treatments have arisen not from rational design, but from attentive recognition of unexpected effects. From chlorpromazine to ketamine, serendipitous discoveries have repeatedly reshaped understanding and treatment of mental illness. As psychiatry moves further into an era of neuroscience-driven approaches and precision medicine, it is vital to preserve the value of close clinical observation and openness to the unforeseen.

The obstacles to serendipitous discovery in contemporary psychiatry are significant, but surmountable. By deliberately creating conditions at individual, institutional and systemic levels that encourage the recognition and investigation of unexpected findings, we can sustain the creative tension between standardised practice and innovative discovery. This does not mean abandoning evidence-based medicine, but expanding the definition of evidence to encompass the careful documentation and study of anomalies. In practice, this requires structured pathways that move observations from bedside recognition to hypothesis generation, rapid evaluation and, when justified, confirmatory trials.

With current treatments leaving many needs unmet, and with the demand for novel therapeutic strategies growing, history suggests that some of the most important future advances may arise not from testing predefined hypotheses, but from prepared minds recognising the significance of the unexpected. Making space for serendipity within modern psychiatric research and practice is not a luxury, but a necessity for continued progress in understanding and treating mental illness.

Ultimately, the case for sustaining openness to serendipitous discovery is a case for intellectual humility – acknowledging that our current knowledge remains incomplete, and that unexpected observations may lead to insights we cannot yet foresee. By valuing serendipity while applying rigorous methods to investigate it, we can foster the conditions for the next generation of breakthroughs that have the potential to transform the lives of those living with mental illness.

About the authors

Stanley Lyndon, MD, is an Associate Neuropsychiatrist at the Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Center for Brain/Mind Medicine, Mass General Brigham, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; and Division of Neuropsychiatry, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. Vineeth P. John, MD, MBA, is a Professor of Psychiatry at the Louis A. Faillace, MD, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, McGovern Medical School, UTHealth Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

Data availability

No new data were generated or analysed in this study.

Author contributions

S.L. was responsible for study conceptualisation, idea development and expansion, and wrote and edited the manuscript. V.P.J. was responsible for study conceptualisation, and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.