1. Introduction

Many words in language are associated with scales whose members are ordered in terms of informational strength (Horn, Reference Horn1972). Examples include such categories of words as quantifiers, adverbs or adjectives (Gazdar, Reference Gazdar1979; Horn, Reference Horn1989). For example, the adjective warm is said to be informationally weaker when compared to its scalar counterpart hot, since a sentence containing the latter such as X is hot entails one with the former (X is warm), whereas the opposite is not the case. Based on such paradigmatic relations, comprehenders often enrich the meaning of sentences containing scalar words, excluding stronger alternatives. Thus, the sentence in (1) may trigger a so-called scalar implicature (Grice, Reference Grice1975; Horn, Reference Horn1972), namely, that Kate’s soup was warm but not hot:

One prominent view to explain how this scalar implicature arises is that comprehenders must consider hot as the stronger alternative to warm in order to negate it. That is, the speaker could have said that Kate’s soup was hot, a stronger statement compared to (1). Since they did not, the comprehender can reason that the stronger statement does not hold. While most theoretical accounts of scalar implicatures agree that such alternatives are a necessary component of the derivation (Sauerland, Reference Sauerland2012), little is known about how they are established in online processing, namely how comprehenders activate, select and represent them. In the current study, we address this question by means of manipulating whether implicatures are licensed. We do this by exploiting negation, a downward entailing environment where scalar implicatures should not occur (see Horn, Reference Horn1972; Panizza et al., Reference Panizza, Chierchia and Clifton2009, for a theoretical treatment and experimental evidence, respectively). We test what kinds of alternatives become available to comprehenders (scale-mates and antonyms) upon processing sentences that do or do not licence scalar implicatures.

Below, we begin by discussing the state of the art regarding the role of alternatives in scalar implicature derivation, and we introduce two competing accounts of how alternatives are established during processing, the Scalar Approach and the Alternative Activation Account. Next, we introduce our two manipulations (negation and antonymy) and show how these allow us to test the two accounts against each other. Then, we report three lexical decision experiments. Overall, we find that both stronger alternatives and antonyms are activated, but that negation cancels their activation. We conclude by arguing that the Alternative Activation Account best describes this pattern of data.

1.1. Scalar implicature derivation and the role of alternatives

Since the seminal work of Grice, it has been established that comprehenders often enrich the meaning of statements containing scalar expressions like (1). Most theoretical accounts have argued that for scalar implicatures to arise, it is necessary to negate the stronger alternative proposition to get the desired upper-bounded meaning (see Sauerland, Reference Sauerland2012, for an overview of other accounts). In (1), the stronger alternative proposition is that Kate’s soup was hot. This needs to be negated and conjoined with the literal meaning of (1) to derive that Kate’s soup was warm but not hot, the strengthened meaning.

While much of the literature assumes that comprehenders reason about alternatives to derive a scalar implicature, it is an open question as to what kinds of alternatives constitute the basis from which implicature computation proceeds. Testing what alternatives are activated and when could inch us closer to answering this question, as results from cognitive processing have been argued to be informative even for formal investigations (Love, Reference Love2015). In this article, we investigate what alternatives are established to later play a role in online scalar implicature derivation. We will present, compare and empirically test two broad accounts of alternative generation online that aim to explain how comprehenders end up with the alternatives that can then be subject to further processes of implicature derivation.

We start with the Scalar Approach (hereafter ScA), a processing account derived from the formal work by Horn (Reference Horn1972, Reference Horn1989); see Chemla & Singh, Reference Chemla and Singh2014, for related processing accounts). According to this view, words such as warm or some have scale-mates that are informationally stronger. These would be hot and all, respectively. Scales are said to be stored in the lexicon. A crucial point in this theory is that each polarity half is considered to be a separate scale, as member ordering is defined in terms of asymmetric entailment. Both warm and cool refer to certain temperature ranges. However, they are not on the same Horn scale, because no asymmetric entailment relationship obtains between sentences containing the two terms. While the stronger scale-mate of warm is hot, for cool it is cold. The theoretical literature on scalar implicatures mostly assumes only the stronger scale-mate to play a role during the process of implicature derivation (e.g., Chierchia, Reference Chierchia2006; Fox, Reference Fox2007; Gazdar, Reference Gazdar1979), as to avoid inferences that would lead to a contradiction with the literal meaning of the sentence. The processing ScA account we consider here can be described as an immediate access theory, which claims that comprehenders immediately activate and represent only the relevant stronger scale-mates for the purpose of deriving scalar implicatures.

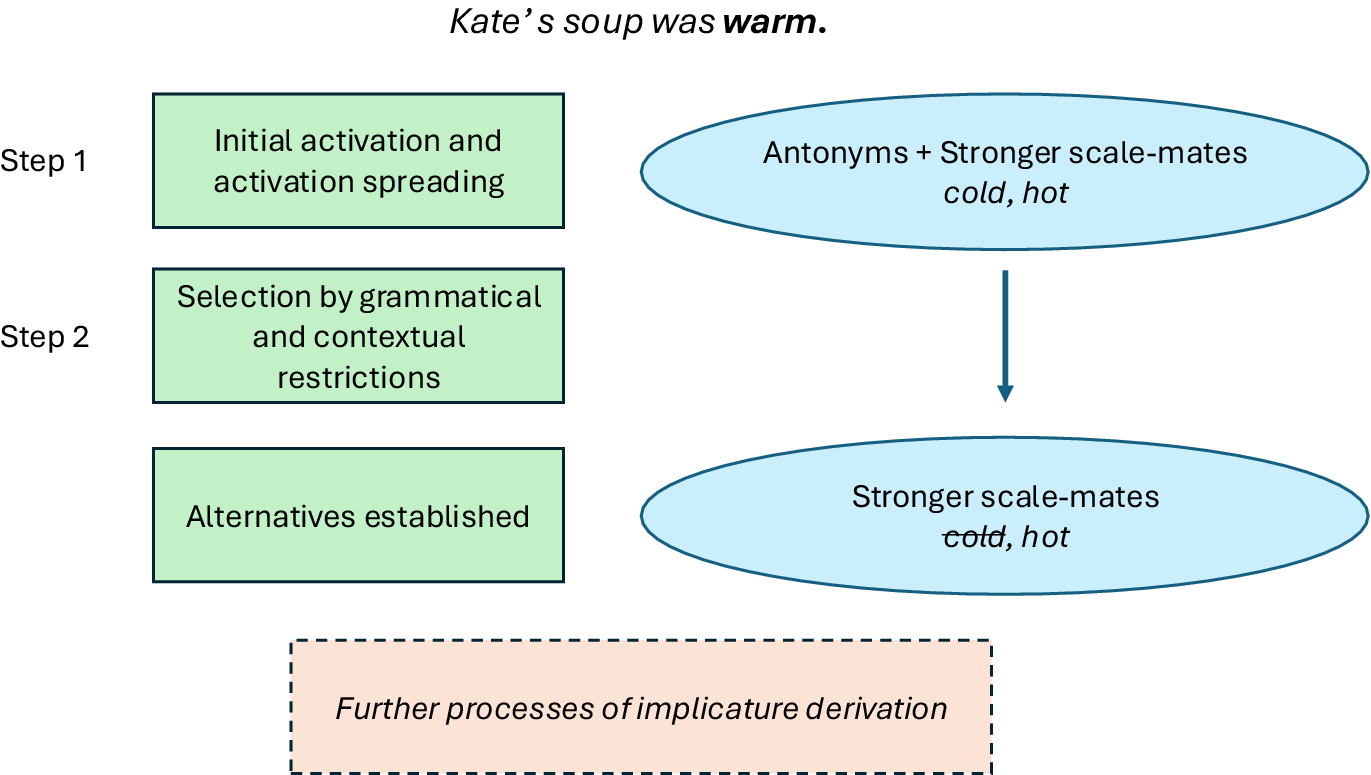

The second account is the Alternative Activation Account (hereafter AAA; Gotzner, Reference Gotzner2019, Reference Gotzner2017, see Gotzner & Lacina, Reference Gotzner and Lacina2025 and Lacina, Reference Lacina2025, for a detailed discussion of the theory). In it, alternatives arise via two consecutive processes. First, there is an initial activation of a broad set of alternatives that happens due to domain-general mechanisms. This amounts to activation spreading in the lexical-semantic network (Swinney, Reference Swinney1979). Afterwards, there is a restriction process that occurs by means of both grammatical and pragmatic constraints. As for grammatical restrictions, these include properties of the sentential context such as monotonicity – for instance, negation, which blocks certain implicatures (Gazdar, Reference Gazdar1979; Hirschberg, Reference Hirschberg1991). This restriction is exploited in the current study. Pragmatic constraints might involve aspects of both the narrow sentential context and the broader discourse context. After this selection, only the proper alternatives that are negated for the purpose of deriving a scalar implicature remain. This account combines accounts of the organisation of the lexical-semantic network and theoretical semantic treatments of alternatives. The AAA has originally been proposed to capture alternatives within the comprehension of linguistic focus. This phenomenon has commonalities with scalar implicatures and has even been claimed to be underpinned by joint mechanisms (see Fox & Katzir, Reference Fox and Katzir2011; Gotzner & Romoli, Reference Gotzner and Romoli2022 for an overview). We provide a graphical illustration of the functioning of the AAA proposal in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The AAA (Gotzner & Lacina, Reference Gotzner and Lacina2025) in the form of a diagram. The initial activation stage (Step 1) following exposure to the sentence in (1) sees the activation of both the stronger alternative (hot) and the antonym cold. In Step 2, there is a selection process during which antonyms are eliminated. What results is the final set of alternatives containing only the stronger alternative. This is then followed by further processes that operate with alternatives to derive the implicature.

We now briefly set up the contrast between the two accounts. The ScA sees no role for expressions that are not the stronger scale-mate, such as antonyms, within the derivation of scalar implicatures. On the other hand, according to the AAA, both informationally stronger alternatives and non-entailed alternatives such as antonyms have a place in the process, at least during the initial activation step due to them being semantically associated. More specifically, the AAA assumes that there is an initial activation of a broad cohort of alternatives based on general cognitive mechanisms underpinning semantic activation spreading (see Gotzner et al., Reference Gotzner, Wartenburger and Spalek2016; Husband & Ferreira, Reference Husband and Ferreira2016, for work on focus). Following this initial activation, the cohort of alternatives needs to be narrowed down to the set of relevant alternatives based on grammatical and contextual restrictions. While Husband and Ferreira view this process to be based on standard priming and selection, Gotzner (Reference Gotzner2017) developed an account for focus based on classic grammatical and contextual restrictions assumed in formal accounts of focus. Recently, Gotzner and Lacina (Reference Gotzner and Lacina2025) have extended such an account to scalar implicature.

Below, we first review the way alternatives in processing have been treated in the investigations of focus and, later, scalar implicatures. This will prove crucial for our study, as focus processing theories have served as a basis for treating the processing of alternatives for online scalar implicature derivation. We then point to a gap in our understanding – what alternatives are activated in the course of scalar implicature processing and when. Lastly, we introduce the predictions of the two accounts and how we use negation and antonymy to test them.

1.2. Focus alternatives

Focus is a category of information structure contrasting with topic or background, which is said to be present in all human languages (Zimmermann & Onea, Reference Zimmermann and Onea2011). While associated traditionally with the expression of new or contrastive information, one of its arguably most successful theoretical treatments sees the function of focus to be the introduction of meaning alternatives (Krifka, Reference Krifka2008). In focus, alternatives are sets of elements capable of replacing the focused element in a sentence within a given context (Rooth, Reference Rooth1985, Reference Rooth1992). Where the phenomena of focus and scalar implicatures intersect most clearly is the case of particles such as only. The semantic contribution of only is to negate the propositions containing the alternatives but not the focused element, that is, to exhaustify (Chierchia, Reference Chierchia2004):

What (2) means is that out of the contextually given set of individuals taking part in the chess tournament, say {Sarah, Mary, Jane, David}, Mary defeated David and no other member of this set. Just as in the case of scalar implicatures, alternatives need to be present to be negated. Notice, however, that both in the case of focus and scalars, alternatives are generated, but that their exclusion in the form of focus exhaustivity inferences or scalar implicatures is accomplished by means of an additional process.

This led to the question whether alternatives are present during the online comprehension of focus. The last decade of research has convincingly shown this (for a review, see Gotzner & Spalek, Reference Gotzner and Spalek2019) using the lexical decision and probe recognition paradigms, which provide us with data on the immediate activation in the case of lexical decision or representation strength in the mental model of the discourse in that of probe recognition. In these paradigms, comprehenders’ reaction times to primed target words as compared to unrelated baselines are measured. It has been found that comprehenders entertain not only the relevant alternatives but also mere semantic associates. When encountering a focused word, comprehenders activate a slew of related words (Braun & Tagliapietra, Reference Braun and Tagliapietra2010). After several hundred milliseconds, this initial set is reduced to only those words that can serve as focus alternatives, as Husband and Ferreira (Reference Husband and Ferreira2016) found with sentences such as:

When contrastive prosody on sculptor was used, initially both merely associated (statue) and contrastively associated (painter) words were activated. However, at 750 ms after the offset of the prime (sculptor), only the contrastively associated words, that is, those that were the true focus alternatives, remained activated. What this showed was that comprehenders were selecting the appropriate alternatives when processing focus. Further research showed that focus particles, such as only and also, strengthen the representation of both contextually mentioned and unmentioned alternatives (Gotzner et al., Reference Gotzner, Wartenburger and Spalek2016; Gotzner & Spalek, Reference Gotzner and Spalek2017). The AAA was first proposed by Gotzner (Reference Gotzner2017, Reference Gotzner2019) to explain how focus alternative sets are composed in comprehenders’ minds.

Such an account can be straightforwardly extended to the domain of scalar implicatures (as shown by Gotzner & Lacina, Reference Gotzner and Lacina2025). In the first step, a broad cohort of associated elements should be activated and subsequently narrowed down to relevant alternatives, that is, stronger scale-mates. There is evidence from existing work that comprehenders may indeed entertain alternatives beyond those necessary for the derivation of the implicature. Peloquin and Frank (Reference Peloquin and Frank2016) have shown that scalar implicatures are better modelled when the full scale, that is, including opposite polarity, is taken into consideration (e.g., expressions such as all, most, some, little and none). This would be expected under the AAA described above, as semantic activation spreading during the first step would include any semantic associates of the scalar word.

Recent work by Muxica and Harris (Reference Muxica and Harris2025a, Reference Muxica and Harris2025b) used a probe recognition task to test whether alternatives that are mentioned in the context but are not semantically related to the focused expression become available early on to comprehenders (A: Andy used a muffin and a pistol as props in a movie that he was directing, B: No, he only used a [cake]F). Their study indicated that focus alternatives that were not semantically related to the focused element were immediately primed after encountering focussed expression. For this reason, they proposed an immediate access model for focus without appealing to an initial step of broad activation of semantic associates. Applying this to the domain of scalar implicatures, we would predict that scalar alternatives can become available immediately, as assumed in the ScA.

1.3. The lexical priming of scalar terms

To directly test which alternatives are activated in the minds of comprehenders, recent lexical priming studies have examined scalar expressions.Footnote 1 Using masked priming and lexical decision, De Carvalho et al. (Reference De Carvalho, Reboul, Van der Henst, Cheylus and Nazir2016) showed that weaker scale-mates activated their strong terms more than the strong did the weak scalars. Their participants were exposed to either the weak (e.g., some) or strong (all) scalar terms in isolation, both as primes and as targets in different conditions. They interpreted their results as pointing towards the psychological reality of lexical scales.

Next, Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023) asked whether comprehenders activated unmentioned alternatives to scalar words when engaged in processing sentences with possible implicatures. They conducted several web-based lexical decision priming experiments, in which participants were exposed to textual stimuli containing scalar words. As opposed to De Carvalho et al. (Reference De Carvalho, Reboul, Van der Henst, Cheylus and Nazir2016), they also manipulated whether the presented scalar words were embedded in sentences or not. The researchers used weak scale-mate terms, which functioned as primes (dirty), which were followed by a target term that was on the same scale yet informationally stronger (filthy). They also included trials with unrelated primes (patterned). A difference in target recognition latency between the two conditions indicated a priming effect. In their so-called lexical experiment, prime words were presented in isolation. In their sentential experiments, the same prime words were embedded within sentences such as:

The idea of Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023) was that a difference between the priming profiles of the two types of experiments could be indicative of the involvement of alternatives in implicature processing. While, in the sentential experiment, one can expect comprehenders to compute scalar implicatures to the negation of the stronger alternative proposition, this does not occur when prime words are presented in isolation. Here, no pragmatic reasoning should be taking place. Therefore, priming should be seen only when the sentential context is available. Their results showed exactly this – weak scalar terms (dirty) primed stronger scale-mates (filthy) when the former appeared within sentential contexts, but not in isolation. They took these results to confirm their predictions: scale-mate terms activated their stronger counterparts when the latter were necessary for implicature computation. They concluded that they had found evidence that stronger alternatives were involved in the process of the real-time derivation of scalar implicatures. However, it must be noted that Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023) did not test for whether their comprehenders in fact derived the implicatures in question. Nevertheless, their data show that when implicatures are possible, stronger scale-mates are activated.

Our current study also uses lexical priming to determine what alternatives constitute the basis for scalar implicature derivation. We will look at two novel test cases, negation and antonyms, that are crucial to decide among the two competing accounts of scalar implicature discussed above.

2. Test cases in the current study

We focus on two cases for which the standard ScA does not predict priming to occur. In entailment reversal-inducing downward-monotonic contexts, according to standard theoretical accounts (Horn, Reference Horn1972; Sauerland, Reference Sauerland2012), no implicature is expected to arise. These are contexts where hot is not informationally stronger than warm. When weak scalar terms are embedded under negation, the entailment relations between the (formerly) weak and strong terms are reversed in exactly this way (Horn, Reference Horn1972):

(5) is true in those and only those worlds in which Kate’s soup has a temperature that is lower than some contextually set standard for warm. This contrasts with the non-negated version of (5), whose literal meaning would be that the soup is at least warm. Moreover, (5) entails that Kate’s soup was not hot. Thus, in negated sentences, the relations between scalar words change such that not warm is stronger than not hot. Thus, the ScA predicts that the (formerly) stronger scale-mate (hot) should not be activated under negation in (5).

The meaning that was conveyed by the implicature in the non-negated counterpart of (5) (warm

![]() $ \to $

‘not hot’) is not predicted to be derived. The case in (5) thus contrasts with the case where this meaning is derived via the scalar implicature, where the negation of the stronger term is seen as needed (Sauerland, Reference Sauerland2012), as seen in sentence (1). It is further the case that comprehenders need not activate the (formerly) stronger term hot as it is not derived as an implicature.

$ \to $

‘not hot’) is not predicted to be derived. The case in (5) thus contrasts with the case where this meaning is derived via the scalar implicature, where the negation of the stronger term is seen as needed (Sauerland, Reference Sauerland2012), as seen in sentence (1). It is further the case that comprehenders need not activate the (formerly) stronger term hot as it is not derived as an implicature.

The second crucial case to distinguish different accounts relies on scalar terms that are of the opposite polarity, that is, antonyms. The reason this could be informative with regards to scalar implicature processing is that antonyms are semantically related to the strong scalar terms of opposite polarity (Murphy, Reference Murphy2003). At the same time, just as in the case of negation, no implicature to the negation of the strong scalar term (hot) is computed:

The meaning ‘not hot’ is already excluded by the literal meaning of (6). This is analogous to the sentence that exemplifies the negation of the weak scale-mate term warm in (5). In fact, the sentential context in (6) supports a scalar implicature to the negation of the corresponding strong term, namely cold. Again then, hot is not needed for the computation of the implicature (‘Kate’s soup was not cold’), at least according to the standard accounts based on the work by Horn (Reference Horn1972). Given the assumption of split scales found within this approach, scalar words that refer to the same underlying dimension, say temperature, but are of opposite polarity, should be irrelevant and, therefore, not activated for the purposes of implicature calculation.

We test what alternatives are active during scalar implicature computation looking at these two test cases: negated scalars and antonyms. We do this by using the method, procedure and items employed by Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023) and testing the priming of target scalar words when these cease to be informationally stronger. We first add negation to scale-mate primes (Experiment 1) and then replace scale-mate primes with their antonyms in a series of two further experiments. In the first antonym experiment (Experiment 2), we use non-negated sentences with antonymic primes. In Experiment 3, we add negation to the sentences with antonymic primes in order to test whether any effects (or lack thereof) observed in Experiment 1 could be attributed solely to negation.

While negation is important here for the purpose of entailment relations reversal, it must be noted that in processing, it carries additional effects that might be able to influence priming. In general, negated sentences incur longer processing times, argued to be due to added difficulty. This has been demonstrated across different sentence types and experimental set-ups, although context has been found to diminish this processing difficulty in some cases (see Kaup & Dudschig, Reference Kaup, Dudschig, Viviane and Espinal2020, for an overview). Studying metaphors under negation with lexical priming, Hasson and Glucksberg (Reference Hasson and Glucksberg2006) found that while in affirmative sentences, metaphorically related target words were activated by their primes at all time-points during processing, whereas under negation, this was the case only in early processing. Capuano et al. (Reference Capuano, Sorg and Kaup2023) found that in some cases, negation enhanced the activation of certain related meanings that could serve as alternatives in the context. This suggests that lexically-induced activation can be maintained under negation.

Many studies have found that there is a strong relationship between words in an antonymic pair in terms of lexical processing (e.g., Becker, Reference Becker1979). Becker (Reference Becker1980) found that as isolated lexical items, antonymic pairs facilitate each other. Crucially, van de Weijer et al. (Reference Van de Weijer, Paradis, Willners and Lindgren2012) found that these effects were not modulated by co-occurrence measures. What this means for our purposes is that the activation of antonyms can likely be attributed to factors relating to their semantic structure, which could then be related to further pragmatic processing. What we aim to do with antonyms in the current study is to test their priming by weak scalars within sentential contexts that do or do not allow for scalar implicatures to be derived, similarly to what Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023) did for strong scalars.

3. Experiments

In this section, we describe the three experiments we conducted and the method used therein. We focused on exploiting the test cases described in the previous section to distinguish between the ScA and AAA. Given that the experiments share most of the materials, procedure and analysis methods, we describe them jointly. We begin by discussing the accounts’ predictions below.

3.1. Experiment overview and predictions

We now turn to the predictions derived from our two accounts. Within the ScA, the proposed lexical nature of scales and their polarity separation (Horn, Reference Horn1972) give us reason to predict that antonyms should not activate strong scalar terms that are of the opposite polarity. When it comes to negation, no priming of the scale-mates is likewise expected. This is because according to this approach, the reversal of entailment relations makes the formerly strong term informationally weaker. As such, it should not be involved in any implicature computation.

The AAA assumes an initial activation stage of general associates followed by subsequent narrowing of activated alternatives based on grammatical and contextual factors (Gotzner, Reference Gotzner2017, Reference Gotzner2019; Gotzner & Lacina, Reference Gotzner and Lacina2025; Husband & Ferreira, Reference Husband and Ferreira2016). When negation is present in the prime sentences with scale-mates, no priming should occur, as the originally stronger target is no longer a relevant alternative for implicature calculation.

As far as antonyms are concerned, the AAA says the following. Firstly, it expects the activation of antonyms in non-negated sentences due to the presence of the first broad activation step postulated by the account. Hence, the priming of antonyms would be compatible with recent results suggesting that stronger scale-mates might not be the only relevant expressions in the course of implicature calculation (Peloquin & Frank, Reference Peloquin and Frank2016; Skordos & Papafragou, Reference Skordos and Papafragou2016), but that antonyms also play a role in this process. Since the AAA proposes that grammatical and contextual factors can influence the activation and selection of alternatives following the initial broad activation stage, it is moreover predicted that negation will affect the activation of targets both in the case of scale-mates and antonyms. In the case of the former, no scalar implicature is expected. When it comes to the latter, that is, antonyms, there is also no expectation of a scalar implicature. If the sentence contains the prime not cool, there is no scalar implicature to the effect of the meaning not hot. Footnote 2 Therefore, we expect no activation from negated antonyms under the AAA.

We report three web-based lexical decision experiments with sentential stimuli that were closely modelled on two of the experiments in Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023). We aimed to test the above-described hypotheses and to expand the findings of Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023) to the case of antonyms and negated scale-mates. Crucially, we also conduct a joint analysis with the data provided on non-negated scale-mate primes in Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023).

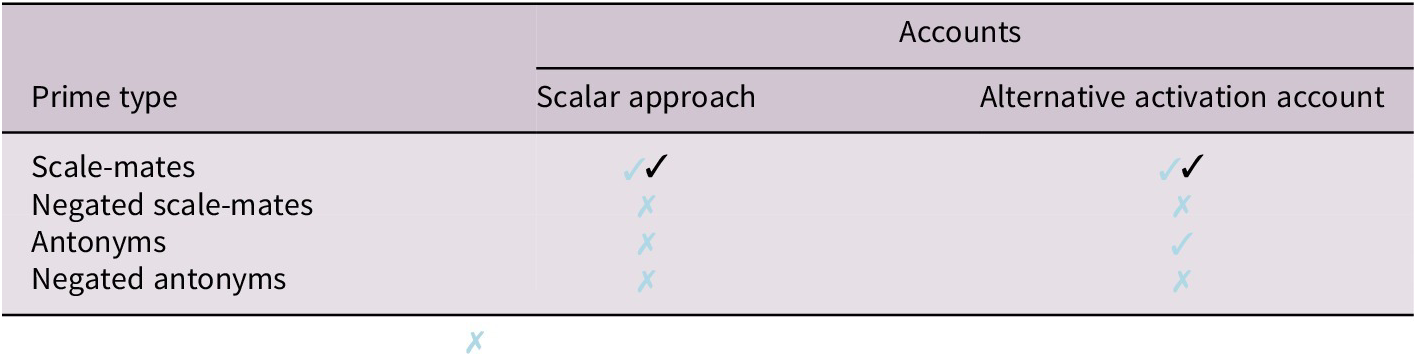

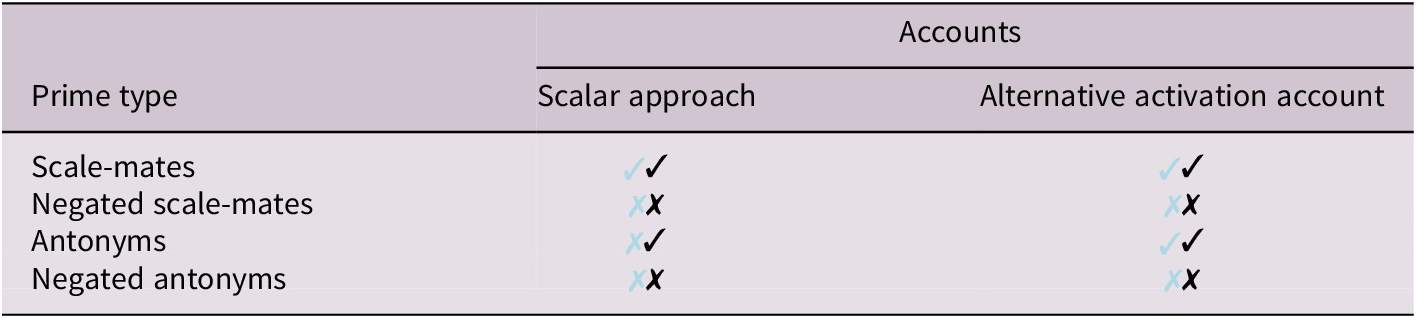

To summarise, in Experiment 1, we use negation to reverse entailment relations between scale-mates to create a context in which our targets, originally strong alternatives to scale-mate primes, become informationally weaker. Both the ScA and the AAA predict no priming. In Experiment 2, we use antonymic primes, which make the target word irrelevant under the ScA. However, priming should be expected under the AAA, since it assumes that a broad cohort of elements is activated. In Experiment 3, we use negated antonyms as primes. Here, both accounts predict no priming. The reader may consult Table 1 to review these predictions. Symbols in blue stand for predictions, and the black tick in the scale-mate row indicates that this was found to be the case by the earlier study of Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023).

Table 1. Predictions of the two accounts for the types of stimuli of interest in blue and the results of Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023) in black

Note: Ticks represent priming, whereas ![]() -signs represent its absence.

-signs represent its absence.

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Materials

We took the scalar terms and associated sentential frames from Experiment 3 of Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023) as our starting point. In Experiment 1, we added constituent negation to the prime, which was either the weak term or an unrelated word, that is, not dirty or not patterned. In Experiment 2, we replaced the prime words in the related condition (i.e., the weak scalar terms) with their antonyms, for example, clean substituted for dirty. The unrelated condition stayed the same. Finally, in Experiment 3, we added negation to these antonyms, resulting in primes such as not clean. Below, the reader may find example items from all experiments.

In addition to testing prime-target pairs that were semantically related, our experiments also included an unrelated condition, exemplified below. Notice that the unrelated prime word is the same across experiments and that the unrelated conditions in Experiments 1 and 3, which include negation, are identical:

The target in all conditions and experiments was filthy, a strong scalar term when compared to dirty and an antonym when compared to clean. In each experiment, we added non-word fillers to match the critical items in the 1:1 ratio, ensuring an equal number of YES and NO responses. We take faster response times to the targets following related primes when compared to unrelated ones as evidence for the increased activation of the targets in the minds of comprehenders at a particular time point.

In the case of some scales where constituent negation could not be constructed, sentential negation was used instead. In Experiment 1, we excluded 8 items from the original list of the 60 items used in Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023), since inserting negation into those sentences made them either ungrammatical or highly infelicitous, resulting in 52 items in total.

For Experiment 2, we replaced the scale-mates from Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023) with their antonyms (e.g., clean for dirty). The target word (filthy) and the unrelated condition were the same as in their experiment.

In order to create the items for Experiment 3, we took the list of 52 items used in Experiment 1 and the list of antonyms used in Experiments 2. We replaced the weaker scale-mate with the corresponding antonym for each item. At this stage, we excluded four more items, since adding negation to the antonym resulted either in ungrammaticality or infelicity, resulting in 48 items.

3.2.2. Participants

For each experiment, we recruited 50 native speakers of English on Prolific (with the exception of Experiment 3 with 49 participants). The participants had to have been born in the United States, live there, be monolingual, have been raised only in English, be 18 to 35 years old and have the highest possible approval rating on Prolific. They received £3 for their participation lasting approximately 13 min. We excluded participants based on the accuracy of their responses to the combined set of experimental and filler items with the threshold being 90%.

In Experiment 1, there were 25 women, 23 men and 2 people of diverse gender. The mean age was 29.72 (sd = 4.05), and we excluded two participants based on their low accuracy. In Experiment 2, the demographics were the following: 19 men, 28 women, 1 person of diverse gender and 2 people who chose not to disclose their gender. The mean age was 27.12 years (sd = 4.96). All participants met the 90% accuracy threshold. In Experiment 3, 19 women and 20 men took part (mean age of 29.83 years, sd = 3.74). Five participants were excluded due to low accuracy.

3.2.3. Procedure

Upon clicking on a link to the hosting PCIBex platform (Zehr & Schwarz, Reference Zehr and Schwarz2018), participants read a consent form, were given instructions and went through 10 practice items. Finally, the experiment itself was started. Sentences were presented using the RSVP method with the rate of 350 ms per word (Potter, Reference Potter2018). Each trial started with a fixation cross (350 ms) followed by 400 ms of a blank screen. After the sentence and 650 ms of a blank screen, the target word appeared for the maximum of 3000 ms. Participants had to indicate as quickly as possible using the keys J for YES and F for NO whether the string was a word of English or not.

Latin Square rotating experimental lists were generated within PCIbex. Thus, no participant saw both the related and the unrelated version of a single item. The order of the items as well as the fillers was randomised per participant.

3.2.4. Analysis

We fit a Bayesian hierarchical model with the log-normal distribution function to the response times larger than 150 ms for each experiment using the package brms (Bürkner, Reference Bürkner2017) in R (R Core Team, 2024). We included the maximal random effects structure (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Levy, Scheepers and Tily2013) with slopes and intercepts for participants and items. We included relatedness as a fixed effect with the levels related (i.e., scale-mate, antonym, coded as

![]() $ 1 $

) and unrelated (coded as

$ 1 $

) and unrelated (coded as

![]() $ 0 $

). The models were run with four chains for 10,000 (2,000 warm-up) iterations each with the seed 1702. We considered

$ 0 $

). The models were run with four chains for 10,000 (2,000 warm-up) iterations each with the seed 1702. We considered

![]() $ \hat{R} $

values close to 1 to indicate convergence. We used the following regularising priors:

$ \hat{R} $

values close to 1 to indicate convergence. We used the following regularising priors:

-

• intercept: N(6.5,1)

-

• the slopes for fixed effects: N(0,0.1)

-

• standard deviation of the random effects: LKJ distribution (Lewandowski et al., Reference Lewandowski, Kurowicka and Joe2009) with

$ \eta =2 $

$ \eta =2 $

For the Bayes factor (BF) analysis, we compared two models that had the same random-effects structure and differed in the fixed effect of relatedness: the null model (i.e., without this fixed effect) and the full model (relatedness included). We calculated BFs for a range of priors, which differed in the standard deviation term for the fixed effect. These values were

![]() $ \sigma =0.1 $

,

$ \sigma =0.1 $

,

![]() $ \sigma =0.05 $

and

$ \sigma =0.05 $

and

![]() $ \sigma =0.01 $

. These priors were non-informative (

$ \sigma =0.01 $

. These priors were non-informative (

![]() $ \mu =0 $

). The higher the

$ \mu =0 $

). The higher the

![]() $ \sigma $

value, the larger the expected size of the effect. This was done because BF analysis is known to be sensitive to prior specification (Schad et al., Reference Schad, Nicenboim, Bürkner, Betancourt and Vasishth2023).Footnote

3 Testing a range of priors allows us to see (a) whether the BF analysis is stable and (b) whether larger or smaller effect sizes are supported by the data. Each model was run for 10,000 iterations (2,000 warm up). The seed was 1702. We then obtained BF values using bridge sampling. This was run five times per prior specification in order to ascertain whether the BF values were stable. We report the mean BF value rounded to the second decimal place.

$ \sigma $

value, the larger the expected size of the effect. This was done because BF analysis is known to be sensitive to prior specification (Schad et al., Reference Schad, Nicenboim, Bürkner, Betancourt and Vasishth2023).Footnote

3 Testing a range of priors allows us to see (a) whether the BF analysis is stable and (b) whether larger or smaller effect sizes are supported by the data. Each model was run for 10,000 iterations (2,000 warm up). The seed was 1702. We then obtained BF values using bridge sampling. This was run five times per prior specification in order to ascertain whether the BF values were stable. We report the mean BF value rounded to the second decimal place.

3.3. Results

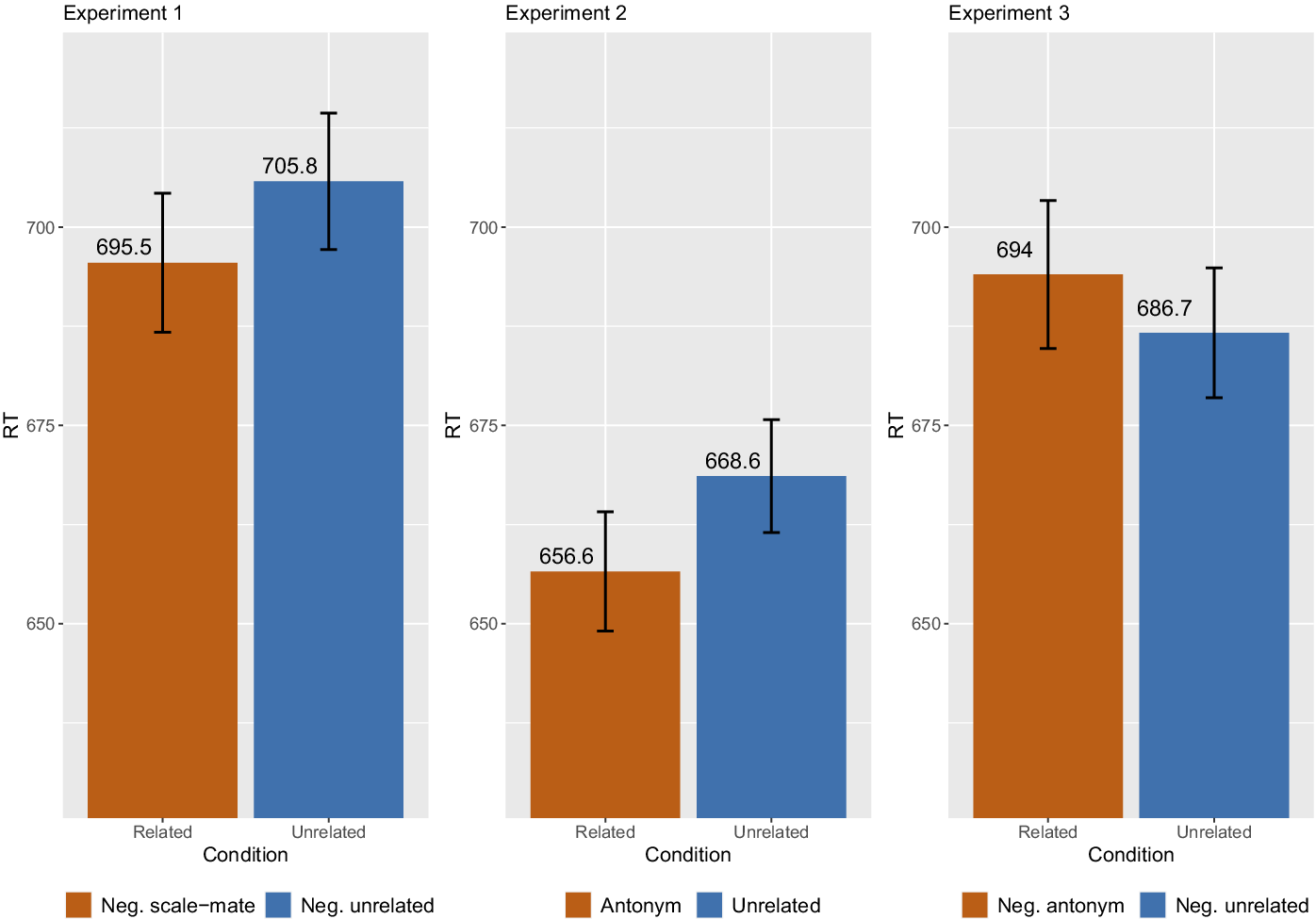

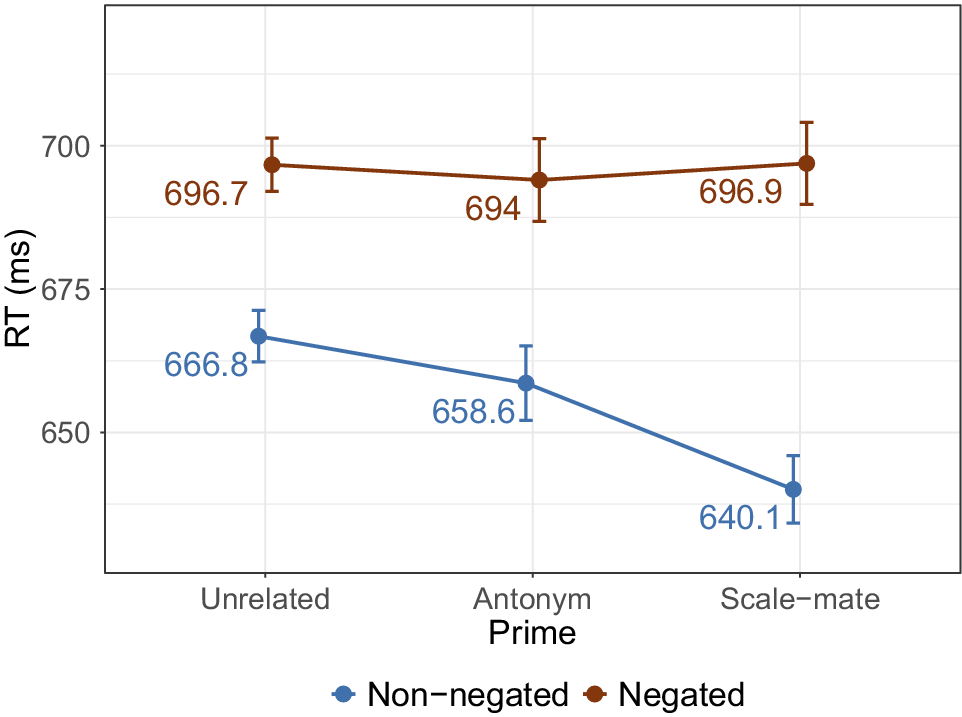

The mean reaction times obtained in all three experiments with their associated standard errors sorted by the relatedness condition are in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Mean reaction times in ms by condition with associated standard errors in Experiments 1, 2 and 3.

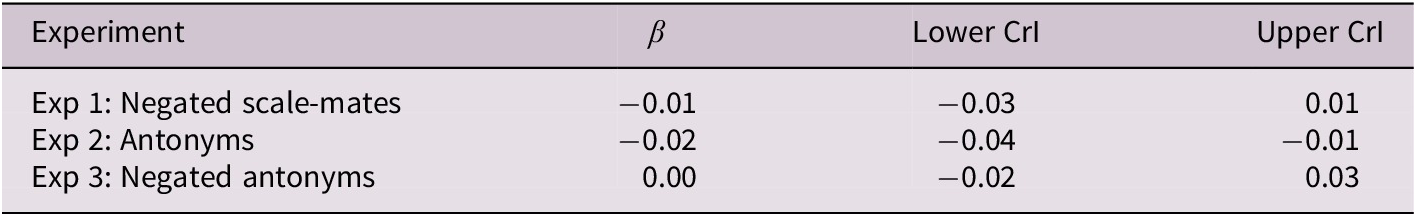

As seen in Table 2, the main effect of relatedness is negative in Experiments 1 and 2 and centred at zero in Experiment 3. The 95% credible intervals cross zero in Experiments 1 and 3, which tested scale-mate and antonym primes under negation, respectively, indicating no priming effect. On the other hand, the intervals in Experiment 2 (non-negated antonyms) are negative and outside of the zero range. This suggests that the factor relatedness had an effect and priming by related words was observed.

Table 2. Estimates and 95% credible intervals of the fixed factor of relatedness in Experiments 1, 2 and 3

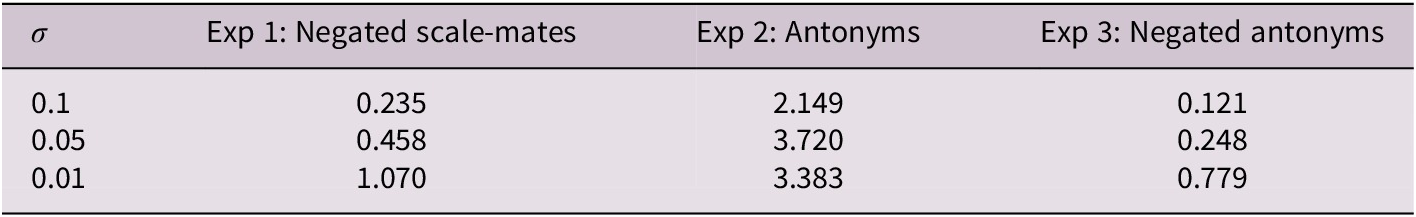

Table 3 summarises the results of our BF analyses for the individual experiments. These analyses compared models with and without the main effect of relatedness. We report the values indicating support for the alternative hypothesis, that is, the full model (BF

![]() $ {}_{10} $

). We can see that only in Experiment 2 were BF values above 1, indicating evidence in favour of including the relatedness factor in the model. However, the strength of this support is rather small, according to a scale provided by Lee and Wagenmakers (Reference Lee and Wagenmakers2014), which classifies it as anecdotal under the broadest prior (

$ {}_{10} $

). We can see that only in Experiment 2 were BF values above 1, indicating evidence in favour of including the relatedness factor in the model. However, the strength of this support is rather small, according to a scale provided by Lee and Wagenmakers (Reference Lee and Wagenmakers2014), which classifies it as anecdotal under the broadest prior (

![]() $ \sigma =0.1 $

) and moderate under the two narrower ones.

$ \sigma =0.1 $

) and moderate under the two narrower ones.

Table 3. Mean BFs in favour of the alternative hypothesis (BF10) in Experiments 1, 2 and 3 comparing the models with the fixed effect of relatedness and without under three sets of priors

On the other hand, we see that in Experiments 1 and 3, which implemented negation, the analysis points that the null hypothesis is preferred, that is, an absence of priming. In Experiment 1 (negated scale-mates), the evidence for the null model is anecdotal to moderate under the two broader priors and inconclusive (close to 1) for the narrowest prior (

![]() $ \sigma =0.01 $

). In Experiment 3 (negated antonyms), the strength of this evidence is moderate under the two broader priors and anecdotal under the narrowest one.

$ \sigma =0.01 $

). In Experiment 3 (negated antonyms), the strength of this evidence is moderate under the two broader priors and anecdotal under the narrowest one.

3.4. Interim discussion

In Experiment 1, we tested the scale-mate terms used by Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023) under negation. Our BF analysis pointed in the direction of no effect – the null hypothesis was preferred under two sets of priors. In Experiment 2, which tested antonyms, we found that antonyms did activate the target word, even though it was no longer informationally stronger. Our analysis showed a preference for the alternative hypothesis, which was weak, yet present under all three sets of priors. Finally, we tested antonyms within negated contexts in Experiment 3. Here, we saw no priming effects, which was similar to Experiment 1, where scale-mates were negated. Again, as in Experiment 1, our BF calculation showed that the null hypothesis was preferred under the broadest prior and the middle one. Under the narrowest prior, there was inconclusive evidence.

4. Joint analysis

Comparing the results from Experiment 1 (negated scale-mates) with the earlier results reported in Ronai and Xiang’s (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023) study, we can tentatively say that while scale-mates are primed in non-negated contexts, introducing negation seems to cancel the activation. However, since the presence of an effect in one experiment and its absence in another does not provide evidence for a difference between experiments, we also conducted a joint analysis of our Experiment 1 (negated scale-mates) and of Experiment 3 from the study of Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023), where the priming of the same terms was tested in non-negated contexts. We also added our Experiments 2 and 3, which tested non-negated and negated antonyms, respectively. This was done in order to see (a) whether negation also cancelled priming with antonymic primes and (b) whether the effect of negation was different for the two types of primes.

We do this to properly test the prediction of the AAA that negation weakens or even cancels the priming of the target word due to informational strength relations between the prime and target changing. This analysis may be conducted, since both our experiments and the one conducted by Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023) used the same scalar terms as well as filler items, experimental script and procedure. The samples for our experiments also employed the same inclusion and exclusion criteria as theirs. It can be argued that our Experiments 1–3 are as similar to Experiment 3 from the study of Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023) as they are to each other. All effort was thus made to make sure that no confounding variables between the experiments would arise due to factors such as participant selection, procedure or filler composition.

The AAA predicts that priming occurs for both antonyms and scale-mates in the non-negated conditions. This is what we already saw in the individual analyses of Experiment 2 and in Ronai and Xiang’s (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023) Experiment 3. Next, we expect negation to interact with scale-mate primes – according to the predictions of the AAA and the ScA, negation ought to block the scalar implicature from arising, so no priming ought to be observed, in line with the null results of our Experiment 1. For antonyms, we expect that there to be a priming effect, given the results of Experiment 2. The AAA also expects no priming to occur for negated antonyms and neither does the ScA. This would predict an interaction of antonyms with negation. There could be a difference in the size of priming between scale-mate and antonym primes and in the effect of negation on this priming in terms of its size, that is, the interaction could differ between different types of primes.

4.1. Analysis

We created a single data set, where we pooled the unrelated trials from the scale-mate and antonym experiments together (separately for the non-negated and negated experiments), since these were identical in the experiments testing antonyms and scale-mate primes. All of the data sets used in this pooling contained cleaned response times of correct answers. We only included the items that were common between all of the experiments resulting in 48 critical items per participant.

We ran two Bayesian hierarchical models with the fixed effects of negation and prime type. The factor of negation had two levels, negated and non-negated. Prime type was unrelated, scale-mate or antonym. The two models differed in their contrast coding, both of which used the treatment type (Schad et al., Reference Schad, Vasishth, Hohenstein and Kliegl2020). For the first model, we used the unrelated primes as the baseline (coded as 0), whereas in the second model, it was the scale-mate prime that was coded as 0. As for the factor of negation, this was coded in the same way in both models, non-negated as 0 (baseline) and negated as 1.

We used this contrast coding to properly test the hypotheses of the AAA. The first model was run to determine whether priming could be observed for scale-mate and antonym primes, respectively, and whether negation interacted with either of the two. The second model allowed us to test the difference between the two types of related primes, scale-mates and antonyms.

Our priors were set in the following way for both models:

-

• intercept: N(6.5,1)

-

• the slopes for fixed effects: N(0,0.1)

-

• the slope for the interaction effect: N(0,0.1)

-

• standard deviation of the random effects: LKJ distribution (Lewandowski et al., Reference Lewandowski, Kurowicka and Joe2009) with

$ \eta =2 $

$ \eta =2 $

Both models were run for 14,000 iterations with four chains. The first 2,000 samples were disposed of as warm-up. The seed was specified as 1702. All the models had

![]() $ \hat{R} $

close to 1, indicating convergence.

$ \hat{R} $

close to 1, indicating convergence.

We then ran a BF analysis to determine whether the inclusion of the interaction term improved the model. This was done to find out whether there was evidence for the factor of prime type interacting with negation. We compared the model with the interaction to the one without, maintaining the same random-effects structure, in a series of priors that were centred at

![]() $ \mu =0 $

with a varying

$ \mu =0 $

with a varying

![]() $ \sigma $

term, which was either

$ \sigma $

term, which was either

![]() $ 0.1 $

,

$ 0.1 $

,

![]() $ 0.05 $

, or

$ 0.05 $

, or

![]() $ 0.01 $

. Each model was run with 10,000 iterations (2,000 discarded for warm-up) with the seed 1702.

$ 0.01 $

. Each model was run with 10,000 iterations (2,000 discarded for warm-up) with the seed 1702.

4.2. Results

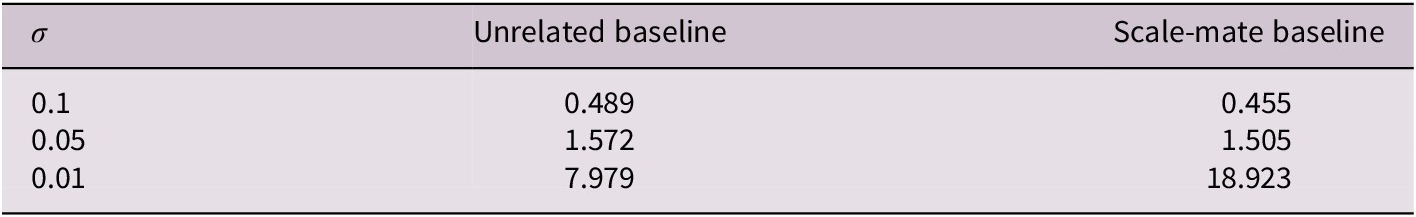

Figure 3 presents a plot of the combined data set sorted according to negation and prime type.

Figure 3. Mean reaction times in ms by negation and prime type with associated standard errors in the combined data set consisting of Experiments 1, 2 and 3 from the current study and Experiment 3 from Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023).

The first model, that is the model with the unrelated non-negated condition set as the baseline, revealed the following effects. Firstly, the simple effect of negation had these characteristics:

![]() $ \beta =0.03 $

, 95% CrI:

$ \beta =0.03 $

, 95% CrI:

![]() $ \left[-\mathrm{0.02,0.09}\right] $

. As far as the simple effect of prime, the values for scale-mates were

$ \left[-\mathrm{0.02,0.09}\right] $

. As far as the simple effect of prime, the values for scale-mates were

![]() $ \beta =-0.03 $

, 95% CrI:

$ \beta =-0.03 $

, 95% CrI:

![]() $ \left[-0.05,-0.02\right] $

and for antonyms

$ \left[-0.05,-0.02\right] $

and for antonyms

![]() $ \beta =-0.02 $

, 95% CrI:

$ \beta =-0.02 $

, 95% CrI:

![]() $ \left[-0.04,-0.01\right] $

. Let us now turn to the interaction between prime type and negation. For scale-mates, the values were

$ \left[-0.04,-0.01\right] $

. Let us now turn to the interaction between prime type and negation. For scale-mates, the values were

![]() $ \beta =0.03 $

, 95% CrI:

$ \beta =0.03 $

, 95% CrI:

![]() $ \left[-\mathrm{0.00,0.05}\right] $

. Antonyms resulted in the following:

$ \left[-\mathrm{0.00,0.05}\right] $

. Antonyms resulted in the following:

![]() $ \beta =0.03 $

, 95% CrI:

$ \beta =0.03 $

, 95% CrI:

![]() $ \left[-\mathrm{0.00,0.05}\right] $

.

$ \left[-\mathrm{0.00,0.05}\right] $

.

The BF analysis only revealed substantial evidence in favour of the interaction between prime type and negation with one of the priors used, the narrowest

![]() $ 0.01 $

$ 0.01 $

![]() $ \sigma $

term (see Table 4). With the middle prior, the values were close to one and, therefore, inconclusive. The opposite was seen with the broadest prior, where some evidence against including the interaction was seen. This can be interpreted as evidence for the interaction, yet with a smaller effect size.

$ \sigma $

term (see Table 4). With the middle prior, the values were close to one and, therefore, inconclusive. The opposite was seen with the broadest prior, where some evidence against including the interaction was seen. This can be interpreted as evidence for the interaction, yet with a smaller effect size.

Table 4. BFs reported as mean BF10 for the combined analyses with unrelated and scale-mate baselines comparing the models with the interaction of prime type and negation and without the interaction by the σ parameter of the prior

The second model was specified with scale-mate primes as the baseline. The simple effect of negation had these characteristics:

![]() $ \beta =0.05 $

, 95% CrI:

$ \beta =0.05 $

, 95% CrI:

![]() $ \left[-\mathrm{0.01,0.11}\right] $

. The main effect of unrelated was the following:

$ \left[-\mathrm{0.01,0.11}\right] $

. The main effect of unrelated was the following:

![]() $ \beta =0.03 $

, 95% CrI:

$ \beta =0.03 $

, 95% CrI:

![]() $ \left[\mathrm{0.02,0.05}\right] $

, while that of antonyms was

$ \left[\mathrm{0.02,0.05}\right] $

, while that of antonyms was

![]() $ \beta =0.01 $

, 95% CrI:

$ \beta =0.01 $

, 95% CrI:

![]() $ \left[-\mathrm{0.01,0.03}\right] $

. The interaction between negation and unrelated primes revealed these values:

$ \left[-\mathrm{0.01,0.03}\right] $

. The interaction between negation and unrelated primes revealed these values:

![]() $ \beta =-0.02 $

, 95% CrI:

$ \beta =-0.02 $

, 95% CrI:

![]() $ \left[-\mathrm{0.05,0.00}\right] $

. Finally, the interaction of negation with antonyms was

$ \left[-\mathrm{0.05,0.00}\right] $

. Finally, the interaction of negation with antonyms was

![]() $ \beta =0.01 $

, 95% CrI:

$ \beta =0.01 $

, 95% CrI:

![]() $ \left[-\mathrm{0.03,0.04}\right] $

.

$ \left[-\mathrm{0.03,0.04}\right] $

.

The BF analysis of the second set of models revealed the following. The broadest priors showed preference for the null model, the middle prior was inconclusive, and there was a clear preference for the alternative model with the interaction of negation and prime type with the narrowest prior. This was especially strong – the mean BF value was 18.9, which can be considered as strong evidence according to the classification proposed by Lee and Wagenmakers (Reference Lee and Wagenmakers2014).

Overall, the joint analysis revealed that our data are most compatible with the AAA. The reader is invited to consult the predictions in Table 1. Since negation has been found to interact with the presence of priming for both scale-mate and antonym primes in this analysis, we have evidence that their activation is sensitive to being within a negated versus non-negated (affirmative) context, which allows for an implicature to be computed. No differences were found between the two types of related primes either in non-negated sentences or under negation. Given this and that for non-negated antonyms, we saw evidence of activation, this result is incompatible with the ScA.

5. General discussion

Alternatives are considered to be a necessary component of implicature derivation by most theoretical accounts (see Sauerland, Reference Sauerland2012, for an overview). Thus, in the current study, we asked what alternatives are activated online in sentential contexts that differ with regard to what implicatures they make possible. We used negation and antonymy to manipulate informational strength relations between primes and targets. We created cases where, according to theoretical views, scalar implicatures should not be present (e.g., Horn, Reference Horn1972, Reference Horn1989). When no longer informationally stronger compared to the prime word due to negation, neither weak scalar words (Experiment 1, not dirty) nor antonyms (Experiment 3, not clean) activated the targets (filthy). When non-negated, antonyms (Experiment 2, clean) did activate the targets of opposite polarity (filthy).

To directly test the effect of negation on priming and specifically the prediction that negation eliminates the activation of the target word, we conducted a combined analysis of our data with the non-negated scale-mate data from Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023). Overall, we can say that the two combined models showed that (a) negation cancels the priming effect for both scale-mates and antonyms and that (b) scale-mates and antonyms behave similarly to each other in negated and non-negated contexts. We also observed that there was no simple effect of negation within unrelated conditions.

5.1. Implications for the accounts

We now turn to what these results mean for the predictions of the accounts introduced earlier (see Table 5).

Table 5. The results (in black) compared to the predictions (in blue) of the two accounts. Ticks represent priming, while x-signs represent its absence

Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023) found evidence that weak scalars activate their stronger scale-mates. We embedded the same items under negation (Experiment 1), which reverses entailment relations and made the target word informationally weaker rather than stronger. In this context, we no longer found activation. This is in line with both the ScA, which predicts that once a scalar term is informationally weaker, it is not activated as it plays no role in any part of the scalar implicature derivation process, and the AAA, which predicts no activation either for stronger alternatives or other expressions when the sentential context is such that scalar implicatures are blocked.

Crucially, we can say that the pattern of priming with antonyms is not consistent with the predictions of the ScA (Experiment 2). This is because this view we proposed based on the theoretical work starting with Horn (Reference Horn1972) predicts only the stronger scale-mates to be activated. This is because the theoretical underpinnings (Horn, Reference Horn1972, Reference Horn1989) do not take antonyms to be members of the same scale as our target word due to their opposite polarity. Thus, no activation related to the possibility of deriving an implicature is expected between scalar terms that are on separate scales in the ScA online processing model.

The AAA on the other hand seems to fit into the observed data with its predictions – priming by weak scale-mates, as reported by Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023), and by antonyms (our Experiment 2), while no priming under negation (Experiments 1 and 3). This is because the AAA proposes that in order for the proper alternatives for implicature derivation to be established, a two-step process of broad initial activation followed by selection is needed. The first step involves the activation of both stronger scale-mates and antonyms. The latter are eliminated in the second step (Gotzner & Lacina, Reference Gotzner and Lacina2025). The proposed functioning of the AAA can be viewed in Figure 1.

The results of the current study have important ramifications for the question about the restriction of alternatives, especially regarding the role of antonyms in scalar implicature computation. Priming for antonyms and scalars occurs in non-negated but not in negated contexts. The activation of both scale-mates and antonyms may be indicative of the claim recently presented in the literature that stronger alternatives are not the only expressions involved in the broadly construed process of scalar implicature derivation (Peloquin & Frank, Reference Peloquin and Frank2016). The AAA would claim that antonyms are activated during the first step of the process, where domain-general mechanisms activate associates within the lexical-semantic network but not during the stage in which the implicature is derived by negating the stronger alternative. These antonyms are culled during the second step when the set of proper alternatives, which are then negated, is created. The main prediction of the AAA for later processing is that antonyms should decay in activation over time (similarly to semantic associates in focus, Husband & Ferreira, Reference Husband and Ferreira2016).

This interpretation of the antonym activation is supported by Lacina and Gotzner (Reference Lacina and Gotzner2025), who used the probe recognition task to examine the strength of representation of strong scalars and antonyms in the resulting mental model of the discourse. They found an interference effect reminiscent of previous results identifying alternatives in the representation of sentences with focus (Gotzner et al., Reference Gotzner, Wartenburger and Spalek2016; Gotzner & Spalek, Reference Gotzner and Spalek2017; Jördens et al., Reference Jördens, Gotzner and Spalek2020; Spalek & Oganian, Reference Spalek and Oganian2019) only for strong scalars, that is only when the target was informationally stronger compared to the prime and could give rise to an implicature. Antonyms were no different from unrelated controls. This suggests that the activation of antonyms observed in the current study is only present in earlier processing stages, when the set of alternatives is only being generated rather than when the implicature is being derived, and that by the point the representation of the discourse is being built, antonyms are already eliminated.

The current results raise questions regarding the timing of the restrictions that get applied to the activated elements during the processing of scalar implicatures (arguably Step 2). We saw that in sentential contexts where scalar implicatures can be derived, antonyms were found to be activated, suggesting that at the point of probing (at 650 ms following the critical word), they were yet to be eliminated. However, at the same time point, negated scalars did not activate either their stronger scale-mates or their antonyms. What this points towards is that the grammatical restriction of negation, which bars certain implicatures, was already operational on the set of activated elements. Alternatively, given the fact that in our stimuli, negation preceded the scalars, the initial activation could have already been blocked.Footnote 4 Further research needs to be conducted to elucidate the questions regarding the timing and strength of various restrictions.

To recapitulate, the AAA for scalar implicatures (Gotzner & Lacina, Reference Gotzner and Lacina2025) assumes both domain-general spreading activation mechanisms to play a role, as well as for grammatical and pragmatic restrictions to operate on alternatives. Comprehenders initially activate a cohort of associated elements including antonyms and other scale-mates and then select the relevant alternatives. Since the targets are no longer informationally stronger under negation, they should not be activated. This account therefore accommodates both of our main findings. We further found that negated antonyms also do not prime the targets (Experiment 3), which is compatible with the AAA. Overall, the results of our experiments could be seen as suggesting that negation presents a strong enough restriction that either does not allow for the activation of the target or triggers a suppression mechanism of the, now informationally weaker, alternative. As for antonyms, it suggests that they are present in the process, yet their exact role needs to be determined by future research.

5.2. Negation processing

We will now address what our results say with regard to the general study of negation processing. Capuano et al. (Reference Capuano, Sorg and Kaup2023) also studied alternative meanings under negation. What they found was that negation activated alternatives, rather than suppressing them. Prima facie, this might be at odds with our own finding that negation cancelled the activation of stronger scale-mates. However, we will argue that the opposite is the case – that they support the AAA’s postulation of selective mechanisms that operate with contextual and grammatical restrictions for the purposes of online pragmatic enrichment. This is due to the difference in the types of alternatives required by the comprehension system in the two cases. In the case of the study of Capuano et al. (Reference Capuano, Sorg and Kaup2023), negation targeted the copula in sentences with nouns for predicates, for example, This is not a dog, where the set of evoked alternatives (including, e.g., wolf) is more analogous to those encountered in focus (Rooth, Reference Rooth1992). In the Capuano et al. (Reference Capuano, Sorg and Kaup2023) study, negation serves as the trigger for alternatives to arise. This contrasts with our study, where the alternatives are of a scalar nature. The scalar word filthy, for example, is informationally stronger compared to its weaker scale-mate dirty. Here, negation interacts with this informational strength relation and makes the (formerly) stronger alternative irrelevant for implicature processing, as no scalar implicature is expected. This is in line with how the AAA approaches alternatives in processing – their activation and selection depend on both contextual and grammatical factors.

The fact that negation cancelled the priming by weak terms, which has been found to occur only in sentential contexts and not in isolation by Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023), is a strong indication that comprehenders do in fact selectively activate the target depending on whether an implicature can be computed or not – that is, depending on whether they are informationally stronger in the given context. That we saw the diffusion of priming by negation suggests that the activation caused by non-negated scale-mates found by Ronai and Xiang (Reference Ronai and Xiang2023) was indeed due to pragmatic processes.

Overall, our study contributes to the study of negation processing by showing that negation can influence the activation of semantically related scalar targets and that this is the case both for scale-mates and antonyms.

6. Conclusion

We addressed the question of what alternatives are activated during the preparatory steps of scalar implicature processing and under what conditions. We ran three experiments, one with negated scale-mates and two with antonyms (within non-negated and negated sentential contexts). Strong scalars are activated by their weak scale-mates (Ronai & Xiang, Reference Ronai and Xiang2023), and our study shows that when these are the antonyms of their primes, they are also activated. Crucially, we find that under negation, which reverses entailment relations, this activation is cancelled. This was the case for both scale-mate and antonym primes. We contrasted two accounts, the Scalar Approach (ScA) and the Alternative Activation Account (AAA). These differed in whether they saw any role for antonyms to be present, with the former seeing no role and the latter predicting antonym activation. Since we observed antonyms to be activated, we concluded that our results are most compatible with the latter theory – the AAA, which allows for both domain-general spreading activation mechanisms to play a role and for grammatical and pragmatic restrictions to operate on the alternatives. Overall, this work contributes to the study of the role of alternatives for online scalar implicature derivation, as well as to the study of negation, by showing that when informational strength relations change, comprehenders change what alternatives they activate.

Data availability statement

The anonymised data and the analysis scripts are available on OSF: https://osf.io/a8c7v.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) as part of the Emmy-Noether grant awarded to the last author (Nr. 441607011). The first author was additionally supported by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD, Scholarship programme Nr. 57694189). They thank Ira Noveck, Matthew Husband, Morwenna Hoeks, Elli Tourtouri, Kristina Kobrock and the audiences of the AMLAP29, XPrag2023 and CogSci45 conferences where this research was presented for their valuable comments and feedback.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethics and consent

This study was conducted as a part of the Scales in Language Processing and Acquisition project, which was granted an ethics approval from the Deutsche Geselschaft für Sprachwissenschaft (German Linguistics Society, Ethikvotum #2019-17-200203).