In recent years, contemporary diets, which largely deviate from traditional diets(Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken1–Reference Tribaldos, Jacobi and Rist3), have become increasingly unhealthy, placing a substantial burden on public health and environmental sustainability(2,Reference von Braun, Afsana and Fresco4) . According to the UN, the world population will grow to 10·4 billion by the end of the century(5), driving a growing demand for food. This demand is occurring alongside a nutritional transition accelerated by technological advancements, globalisation and westernisation that is linked to rising rates of non-communicable diseases and increased environmental burdens(Reference von Braun, Afsana and Fresco4,6) . According to data from the WHO, approximately one-tenth of the world’s population suffers from hunger, while 43 % of adults are overweight and 16 % are obese(7). Although technological advances have enabled a growing population to be fed, the current food system fails to ensure environmental sustainability, contributing to climate change through the generation of high greenhouse gas emissions (GHGE) and overconsumption of available resources(Reference Allan, Arias, Berger, Masson-Delmotte, Zhai and Pirani8–Reference Stuart, Lüterbacher and Paterson10). About 30 % of GHGE are associated with the food system(Reference von Braun, Afsana and Fresco4,Reference Allan, Arias, Berger, Masson-Delmotte, Zhai and Pirani8) and are projected to rise by an estimated 80 % if these dietary trends are left unchecked(Reference Tilman and Clark11). There is an urgent need to transition to sustainable, healthy food systems to assist in the reduction of the burden on the environment and improvements in overall public health. This is emphasised by international and national organisations calling for immediate action(Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken1,2,Reference von Braun, Afsana and Fresco4,Reference Shukla, Skeg and Buendia9,12) supported by current research evidence(Reference Ruben, Cavatassi and Lipper13–15).

Leading organisations have set out frameworks to encourage sustainable and healthy eating in response. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recommends transitioning towards healthy, sustainable and locally based diets to help mitigate climate change(2,Reference Shukla, Skeg and Buendia9) . The WHO and the FAO of the UN released sixteen nutritional guidelines advocating dietary changes to align with sustainability principles(Reference Martini, Tucci and Bradfield16). Furthermore, the EAT-Lancet Commission was established to define targets for healthy diets and food production to meet the health and sustainability needs of global populations and the environment(Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken1). The WHO and FAO define a sustainable diet as one that is adequately nutritious, accessible, economically fair and affordable, safe, culturally acceptable, and that minimises the environmental impact of food consumption and production(2). A sustainable diet is necessary to provide food security and nutrition for present and future generations(2). Despite these global initiatives, many challenges remain in their adoption. Sustainable diets also must be tailored to local cultural contexts and populations to be widely applicable and acceptable(2,Reference Shukla, Skeg and Buendia9,Reference Monterrosa, Frongillo and Drewnowski17) .

Traditional diets are shaped over centuries and tailored to local environments and cultures, often emphasising whole foods, seasonal and locally sourced ingredients, and diverse plant-based dishes, aligning well with modern sustainability principles(Reference Vargas, de Moura and Deliza18–Reference Durazzo20). These diets should be considered for their potential to address global issues from a culturally sensitive perspective, offering viable alternatives to current food systems(Reference Oita, Nagano and Matsuda21,Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22) .

However, traditional diets lack a clear definition, ranging from indigenous and ancestral diets to local, minimally processed foods. A relatively recent review of twenty-three definitions (1995–2019) found no consensus but identified four common traits: time, place, skills and cultural meaning, with intergenerational knowledge emerging as the most frequent characteristic. Most research is Europe-based and consumer-focused, highlighting the need for clearer, locally grounded definitions(Reference Rocillo-Aquino, Cervantes-Escoto and Leos-Rodríguez23).

For this review, we adopt a working definition of traditional place-based diets as the locally available foods culturally recognised within a community(Reference Roudsari, Vedadhir and Rahmani24). These foods are specific to a certain place and population, supported by recipes and cooking techniques passed down over generations(Reference Roudsari, Vedadhir and Rahmani24,Reference Chopera, Zimunya and Mugariri25) . They commonly reflect cultural identity and are associated with happiness, love and social connection(Reference Renko and Bucar26). Recognising these complexities is critical, as such diversity and cultural embeddedness challenge the use of standardised health and sustainability metrics, which often rely on nutrient composition or environmental footprints without accounting for contextual or cultural dimensions. The Mediterranean diet (MedD) has been the subject of substantial attention in scientific research as a dietary pattern that promotes both health and environmental preservation(Reference Sáez-Almendros, Obrador and Bach-Faig27–Reference Dernini, Berry and Serra-Majem29). Emphasising the consumption of plant-based foods (vegetables, fruits, legumes and unrefined grains), while also incorporating moderate amounts of meat, fish and olive oil(Reference Lăcătușu, Grigorescu and Floria28). UNESCO’s recognition of the MedD as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity highlights not only its nutritional value but also the lifestyle and cultural practices embedded within(Reference Lăcătușu, Grigorescu and Floria28,Reference Dernini, Berry and Serra-Majem29) . Similarly, the traditional Japanese diet, Washoku, which includes nutrient-rich foods such as soyabeans, seaweed, green tea and fish, is also acknowledged by UNESCO for its holistic cultural significance(Reference Oita, Nagano and Matsuda21). Both diets have demonstrated positive health outcomes and environmentally sustainable practices within their regions(Reference Gabriel, Ninomiya and Uneyama19,Reference Oita, Nagano and Matsuda21,Reference Damigou, Naumovski and Panagiotakos30) . However, there remains a significant gap in the exploration of other traditional diets from different regions, whose diversity and potential benefits are still underexamined.

This review examines how traditional place-based diets have been assessed for health and sustainability in the global literature and evaluates the relevance of common metrics in capturing their cultural and contextual complexity. The goal is to identify effective, evidence-based approaches for promoting sustainable, healthy diets across diverse populations.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was conducted to identify all studies examining traditional diets within their cultural contexts as a tool for sustainable and healthy diet transformation. The study protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) at the University of York (ID: CRD42023445750).

Search strategy

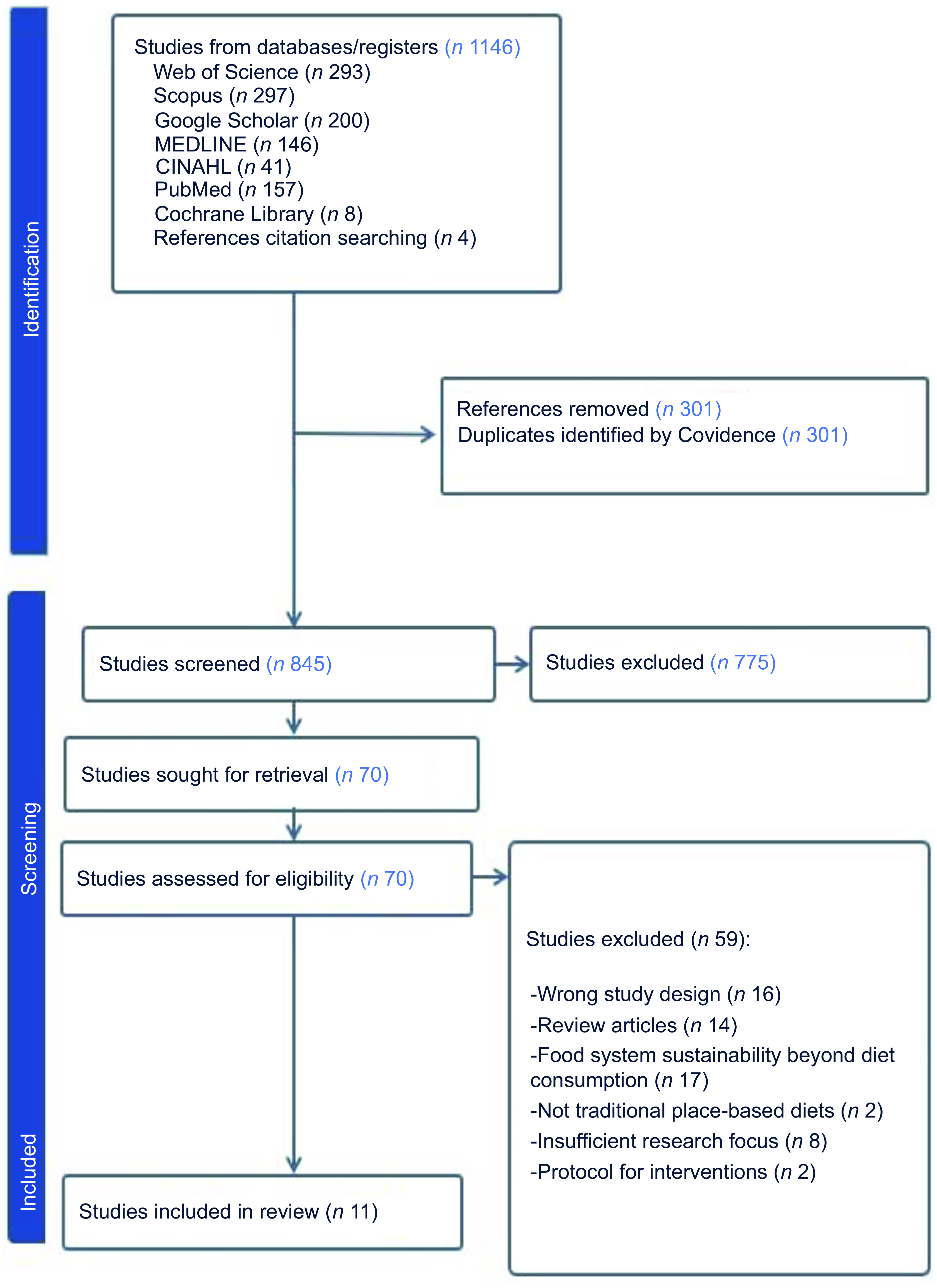

This review followed the PRISMA 2020 protocol (Figure 1)(Reference Parums31). Seven electronic databases were searched (CINAHL, Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, PubMed and Google Scholar) using keywords developed with the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) and included key terms such as ((‘traditional diet*’ OR ‘traditional food*’ OR ‘place-based diet*’ OR ‘place-based food’) AND (‘health*’) AND (‘sustainable*’ OR ‘environmentally friendly’ OR ‘EAT-Lancet’)). A search of grey literature was conducted to identify related studies, and reference lists of relevant studies that met the inclusion criteria were reviewed. Literature searches were concluded in June 2024 without a time restriction on publication date. Only articles published in English were included.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process. The diagram illustrates the identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion stages for articles in the systematic review. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion

All traditional place-based diets were eligible. Included studies examined the health benefits and sustainability impacts of traditional food consumption, including environmental sustainability assessments, but were restricted to diet and food consumption only. Additionally, included studies were required to present the design, implementation, promotion or evaluation of traditional place-based diets to health and sustainability outcomes and to assess these diets against established health and sustainability guidelines. All study designs providing relevant information to the research question, including both grey literature and peer-reviewed original articles, were eligible.

Exclusion

Studies were excluded if they examined non-traditional diets or traditional diets outside traditional locations, did not assess the health and sustainability impacts of the diets, focused on traditional diet components or food systems threatened by environmental pressures, assumed sustainability without explicitly addressing it, or examined individual nutrients or food ingredients without considering their broader context. We also excluded studies focusing on farmers or agricultural practices, production and hunting, as well as those studies addressing the loss of traditional diets and related food insecurity due to climate and social change. Reviews, opinion articles, editorials, commentaries, letters to the editor, conference abstracts and publications lacking original research content, or which failed to provide sufficient data for analysis or protocols for interventions were excluded. We found overlaps in sustainability themes beyond this review’s scope, leading to categorised exclusions by two authors (FA and RM).

Process of selection and data collection

Following the search strategy, eligible papers were identified and integrated into the Covidence software (https://www.covidence.org), and duplicates were removed(Reference Kellermeyer, Harnke and Knight32). The inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied independently by two authors (FA and RM) who screened papers by title and abstract. Any discrepancies were resolved through consultation between the authors and a third author (NN).

Data extraction

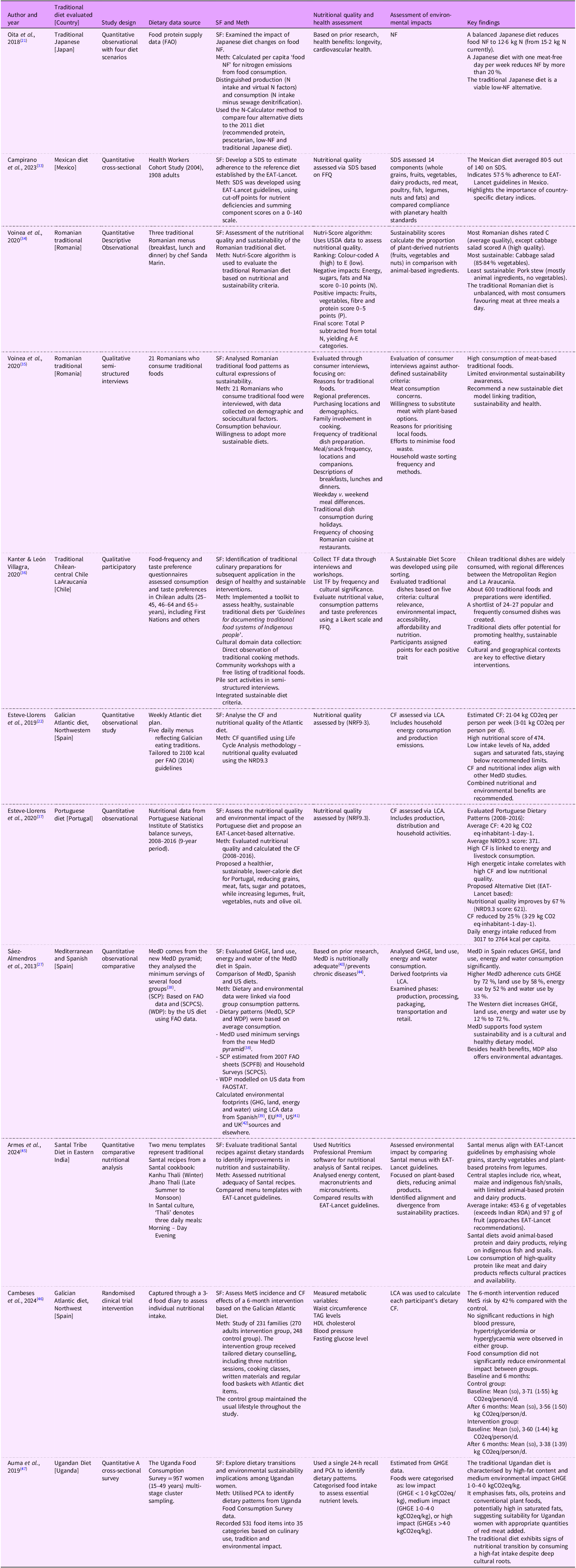

Data were extracted and organised into a pre-defined table identifying the methods and tools used to assess the nutritional and sustainability impacts of traditional place-based diets and the key findings (Table 1). Considering recent publications and the growing interest in the field, our screening of manuscripts identified various combinations involving traditional diet, health and sustainability concepts. Applying our criteria strictly limited findings to studies focused solely on diet and food consumption.

Table 1. Study characteristics, methodology and tools used for articles included in this review of traditional place-based diets as a tool for transforming health and sustainability

SF, study focus; Meth, methodology; TF, traditional food; NF, nitrogen footprint; CF, carbon footprint; LCA, life cycle assessment; GHGE, greenhouse gas emissions; SDS, Sustainable Dietary Score; USDA, United States Department of Agriculture; NRD9.3, Nutrient-Rich Dietary Index; MedD, Mediterranean diet, SCP, Spanish diet, SCPCS, Spanish Ministry Surveys, WDP, Western diet, MetS, metabolic syndrome, RM, metropolitan region, AR, Region of La Araucanía, PCA, principal component analysis.

Assessment of quality

Due to the diverse and heterogeneous research methodologies employed, we encountered challenges in evaluating the quality of the studies. Consequently, direct comparisons between the studies were not feasible. Given this heterogeneity in study designs, populations and methods, a narrative synthesis approach was used to integrate and interpret the findings.

Results

Study selection

Studies were identified and selected as shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (see Figure 1). An initial search yielded 1146 results. After removal of duplicate articles and title and abstract screening, seventy full-text eligibility were assessed by two researchers (FA and RM). This process led to the inclusion of eleven studies(Reference Oita, Nagano and Matsuda21,Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22,Reference Sáez-Almendros, Obrador and Bach-Faig27,Reference Campirano, López-Olmedo and Ramírez-Palacios33–Reference Esteve-Llorens, Dias and Moreira37,Reference Armes, Bhanjdeo and Chakraborty45–Reference Auma, Pradeilles and Blake47) .

Study characteristics

This review examined traditional diets across populations in eight countries: Spain.(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22,Reference Sáez-Almendros, Obrador and Bach-Faig27,Reference Cambeses-Franco, Gude and Benítez-Estévez46) , Romania(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Negrea34,Reference Voinea, Popescu and Bucur35) , Chile(Reference Kanter and León Villagra36), Japan(Reference Oita, Nagano and Matsuda21), Portugal(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Dias and Moreira37), Mexico(Reference Campirano, López-Olmedo and Ramírez-Palacios33), Uganda(Reference Auma, Pradeilles and Blake47) and India(Reference Armes, Bhanjdeo and Chakraborty45) (Table 1).

Only two studies(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Bucur35,Reference Kanter and León Villagra36) used qualitative methods with specific populations: the Chilean ethnic group(Reference Kanter and León Villagra36) and Romanians(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Bucur35). Five studies utilised secondary data sources and included Portuguese food balance surveys.(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Dias and Moreira37), Japanese FAO data(Reference Oita, Nagano and Matsuda21), Mexican Health Workers from the Cohort Study(Reference Campirano, López-Olmedo and Ramírez-Palacios33), Spanish FAO data and Spanish Ministry Surveys. Two studies examine minimal servings from the new Mediterranean Pyramid (MDP)(Reference Sáez-Almendros, Obrador and Bach-Faig27) and Ugandan food consumption data from a nationally representative survey(Reference Auma, Pradeilles and Blake47). Others used traditional recipes(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Negrea34,Reference Armes, Bhanjdeo and Chakraborty45) , weekly diet plans(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22) and clinical trial analyses(Reference Cambeses-Franco, Gude and Benítez-Estévez46).

The studies focused on different outcomes: environmental impact only (n 2)(Reference Oita, Nagano and Matsuda21,Reference Sáez-Almendros, Obrador and Bach-Faig27) , both nutrition and environment (n 4)(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22,Reference Voinea, Popescu and Negrea34,Reference Esteve-Llorens, Dias and Moreira37,Reference Auma, Pradeilles and Blake47) , health and environmental impact (n 1)(Reference Cambeses-Franco, Gude and Benítez-Estévez46), cultural and sustainability insights (n 2)(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Bucur35,Reference Kanter and León Villagra36) , and alignment with global guidelines from the EAT-Lancet Commission (n 2)(Reference Campirano, López-Olmedo and Ramírez-Palacios33,Reference Armes, Bhanjdeo and Chakraborty45) . Only one was a randomised controlled trial(Reference Cambeses-Franco, Gude and Benítez-Estévez46), evaluating a 6-month Atlantic diet intervention for its effects on metabolic syndrome (MetS) and carbon footprint (CF). The rest used observational or cross-sectional designs.

The environmental impact of traditional diets was assessed using indicators such as GHGE, carbon and nitrogen footprints (NF), land use, energy, and water consumption. Four studies(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22,Reference Sáez-Almendros, Obrador and Bach-Faig27,Reference Esteve-Llorens, Dias and Moreira37,Reference Cambeses-Franco, Gude and Benítez-Estévez46) used life cycle assessment (LCA): Two in Spain evaluated the Atlantic diet’s CF(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22,Reference Cambeses-Franco, Gude and Benítez-Estévez46) , one in Portugal assessed the Portuguese diet’s CF(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Dias and Moreira37) and another in Spain analysed the GHGE, land energy and water use of adhering to MedD(Reference Sáez-Almendros, Obrador and Bach-Faig27). Additionally, a Ugandan study classified foods by GHG impact(Reference Auma, Pradeilles and Blake47), while a Japanese study focused on the NF(Reference Oita, Nagano and Matsuda21).

Nutritional quality and health outcomes were assessed using various tools. Three studies(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22,Reference Voinea, Popescu and Negrea34,Reference Esteve-Llorens, Dias and Moreira37) evaluated dietary nutritional quality, two used the Nutrient-Rich Diet (NRD9.3) score(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22,Reference Esteve-Llorens, Dias and Moreira37) and one applied the Nutri-Score algorithm(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Negrea34). A randomised controlled trial(Reference Cambeses-Franco, Gude and Benítez-Estévez46) evaluated the Atlantic diet’s effects on MetS, offering potential evidence of health impact.

These studies provided primary analyses of health and sustainability, with four studies assessing both environmental impact and nutritional quality or health outcomes(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22,Reference Esteve-Llorens, Dias and Moreira37,Reference Cambeses-Franco, Gude and Benítez-Estévez46,Reference Auma, Pradeilles and Blake47) . While two studies(Reference Oita, Nagano and Matsuda21,Reference Sáez-Almendros, Obrador and Bach-Faig27) focused solely on environmental aspects, they referenced health outcomes indirectly. The Japanese study measured only the NF(Reference Oita, Nagano and Matsuda21), and the Spanish study compared the environmental performance MedD to Spanish and US diets(Reference Sáez-Almendros, Obrador and Bach-Faig27). Other studies aligned traditional diets with EAT-Lancet guidelines(Reference Campirano, López-Olmedo and Ramírez-Palacios33,Reference Armes, Bhanjdeo and Chakraborty45) . In India, nutrient intakes were compared with EAT-Lancet targets(Reference Armes, Bhanjdeo and Chakraborty45), while in Mexico, a Sustainable Dietary Score (SDS) was developed(Reference Campirano, López-Olmedo and Ramírez-Palacios33). Qualitative approaches were also used in Chile and Romania to explore cultural values and sustainability through cultural domain analysis(Reference Kanter and León Villagra36) and semi-structured interviews(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Bucur35) (Table 1).

Environmental impact of traditional diets

The Atlantic, MedD, Ugandan and Japanese diets were all assessed as sustainable, showing lower environmental impacts such as reduced CF, GHGE and NF compared to the contemporary Western diet. However, the extent varied by dietary pattern and context.

The Atlantic diet, assessed in northwestern Spain, was associated with a CF of 3·01 kg CO₂eq/d in one observational study(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22). A clinical trial in the same region found a small, non-significant reduction of −0·17 kg CO₂eq/d (from 3·71 to 3·38 kg CO₂eq/d) after 6 months (P = 0·24)(Reference Cambeses-Franco, Gude and Benítez-Estévez46). In Portugal, the current national diet had a higher CF of 4·20 kg CO₂eq/d, but modelling an EAT-Lancet-adapted version of the Portuguese diet reduced CF by almost 25 %, to about 3·29 kg CO₂eq/d(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Dias and Moreira37), indicating potential synergies between global dietary recommendations and local adaptations of traditional eating patterns.

The MedD in Spain was associated with significant environmental benefits, including reductions in GHGE (72 %), land use (58 %), energy consumption (52 %) and water use (33 %), while Western diets increased these impacts(Reference Sáez-Almendros, Obrador and Bach-Faig27). The Japanese study found that incorporating a weekly meat-free day into a traditional dietary pattern reduced NF by over 20 %, from 15·2 to 12·6 kg N/week(Reference Oita, Nagano and Matsuda21). Similarly, in Uganda, traditional plant-based diets were categorised as having a medium environmental impact (GHGE 1·0–4·0 kg CO₂eq/kg), notably more sustainable than high-impact, animal-based diets exceeding 4·0 kg CO₂eq/kg(Reference Auma, Pradeilles and Blake47). Across the included studies, traditional plant-forward diets consistently showed lower environmental impacts than animal-based or Western patterns, which may further support long-standing proposals of their benefits.

Nutritional quality and health evaluation

The three traditional diets of the Atlantic, Mediterranean and Japanese regions were assessed as being healthy. In northwestern Spain, the traditional Atlantic diet achieved an NRD9.3 score of 450(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22). A 6-month randomised controlled trial further demonstrated a reduction in the incidence of MetS (defined as a cluster of conditions that increase the risk of heart disease, stroke and T2DM) in the intervention group compared to controls (2·7 % v. 7·3 %, relative risk = 0·32)(Reference Cambeses-Franco, Gude and Benítez-Estévez46). Significant improvements were reported in waist circumference, central obesity risk and HDL-cholesterol, although no significant changes were observed in blood pressure, TAG or fasting glucose levels(Reference Cambeses-Franco, Gude and Benítez-Estévez46). The Portuguese study found a 67 % increase in NRD score (from 377 to 621) when following a low-calorie diet aligned with EAT-Lancet guidelines(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Dias and Moreira37). In Spain, the MedD was evaluated through secondary data and found to be nutritionally adequate, with evidence supporting its role in chronic disease prevention(Reference Sáez-Almendros, Obrador and Bach-Faig27). Moreover, the Japanese study indicated that adhering to the traditional Japanese diet was associated with positive health outcomes, such as extending lifespan and reducing the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and heart disease(Reference Oita, Nagano and Matsuda21).

Not all traditional diets meet health standards. Two studies found the traditional Romanian diet unhealthy, citing high meat consumption as a contributing factor.(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Negrea34,Reference Voinea, Popescu and Bucur35) . However, high meat consumption alone does not determine a diet’s healthiness. The Romanian diet also lacks sufficient vegetables, fibre and other essential nutrients, which contribute to its lower nutritional quality.(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Negrea34)

One study found that most traditional Romanian dishes were rated ‘C’ on the Nutri-Score scale, reflecting average nutritional quality, largely due to frequent consumption of meat-heavy meals three times daily and insufficient plant-based components(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Negrea34). A qualitative study further reported that daily meat consumption is common in Romania and that there is low acceptance of plant-based diets among the population(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Bucur35). Both studies highlight the diet’s low vegetable intake and high reliance on animal-based foods, recommending improvements to enhance both health and sustainability(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Negrea34,Reference Voinea, Popescu and Bucur35) .

Traditional diet and alignment with global standards EAT-Lancet

Two studies(Reference Campirano, López-Olmedo and Ramírez-Palacios33,Reference Armes, Bhanjdeo and Chakraborty45) , evaluated traditional diets against the EAT-Lancet Commission’s reference diet, focusing on nutritional components rather than environmental impact measures. In Mexico(Reference Campirano, López-Olmedo and Ramírez-Palacios33), a SDS was developed based on the EAT-Lancet framework, incorporating fourteen food components. The average score was 80·5 out of 140, indicating 57·5 % adherence to EAT-Lancet guidelines among adults in the Health Workers Cohort Study(Reference Campirano, López-Olmedo and Ramírez-Palacios33). In India(Reference Armes, Bhanjdeo and Chakraborty45), traditional meals of the Santal tribe partially aligned with EAT-Lancet’s plant-based recommendations but lacked animal protein and dairy products, a divergence driven by cultural practices and geographic factors that deviates from both Indian dietary recommendations and EAT-Lancet guidelines(Reference Armes, Bhanjdeo and Chakraborty45). Traditionally, people in the Santal tribe avoid dairy products, in contrast to the Indian recommendations of 300 g per d(48) and the EAT-Lancet guidelines of 250 g per d(Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken1).

Qualitative insights: cultural and sustainable dimensions of traditional diets

Two qualitative studies(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Bucur35,Reference Kanter and León Villagra36) provided insights by engaging populations to explore personal experiences, regional preferences and sustainability perceptions of traditional foods. In Chile(Reference Kanter and León Villagra36), a study used an adapted version of the ‘Guidelines for Documenting Traditional Food Systems of Indigenous People’(Reference Kuhnlein, Smitasiri and Yesudas49) to evaluate sustainable traditional diets(Reference Kanter and León Villagra36). Originally designed to document traditional food, this toolkit was expanded to assess entire culinary preparations and ingredients, identifying culturally significant foods for sustainable health interventions. The sustainability of dishes was calculated based on cultural suitability, nutritional sufficiency, accessibility, economic fairness and environmental impact(Reference Kanter and León Villagra36). The study highlighted diverse traditional preparations, particularly vegetable-based dishes, to guide healthy, sustainable interventions(Reference Kanter and León Villagra36).

In Romania(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Bucur35), a qualitative study identified that participants were highly positive about traditional dishes, mainly due to their cultural significance, evoking memories of childhood and a sense of pride. These foods are highly regarded for their authenticity, nutritional value, freshness and taste, although overconsumption of meat was identified as a challenge to sustainability(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Bucur35). These qualitative findings highlight the depth of cultural knowledge and lived experiences, offering dimensions of sustainability often overlooked in standardised dietary assessments.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to examine how traditional place-based diets contribute to both health and environmental sustainability while critically evaluating the methodological limitations of current assessments. While traditional diets are often assumed to be inherently beneficial, our findings show this is not always the case. Mediterranean, Atlantic and Japanese patterns exhibit the alignment of nutritional quality with environmental sustainability, whereas Romanian(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Negrea34,Reference Voinea, Popescu and Bucur35) and the Indian Santal diets(Reference Armes, Bhanjdeo and Chakraborty45) highlight risks of environmental burden or nutritional gaps. These contrasts demonstrate that the sustainability of traditional diets cannot be assumed but requires context-specific and critical assessment.

We note a lack of standardised methods to jointly assess nutritional and environmental adequacy. Although tools like NRD9.3, Nutri-Score, LCA and EAT-Lancet frameworks were widely applied across the included studies, their relevance for capturing the cultural and ecological complexity of traditional diets remains contested. While LCA is widely recognised, most dietary studies focus narrowly on CF or GHGE. These are important climate metrics and are often used as proxies for other impacts (e.g. acidification, eutrophication)(Reference Harrison, Palma and Buendia50,Reference Masset, Soler and Vieux51) but can oversimplify food system impacts, overlooking biodiversity loss, soil carbon depletion and food waste(Reference González-García, Esteve-Llorens and Moreira52,Reference Ridoutt, Hendrie and Noakes53) . A review of 113 sustainable diet studies found that GHG were the most frequently used indicator (63 %), followed by land use (28 %) and energy use (24 %)(Reference Jones, Hoey and Blesh54).

Additionally, inconsistencies in system boundaries further reduce comparability: some studies assess the full life cycle from production to consumption, while others omit packaging, transport or waste(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22,Reference Esteve-Llorens, Dias and Moreira37) , potentially underestimating impacts(Reference Harrison, Palma and Buendia50). Inconsistent definitions and labelling of similar LCA metrics, along with single-indicator approaches, can distort results or shift impacts between stages or regions(Reference Ridoutt, Hendrie and Noakes53). These inconsistencies hinder meaningful comparison of traditional diets across settings(Reference Harrison, Palma and Buendia50).

Another challenge is the mismatch between standardised LCA indicators and the localised nature of traditional food systems. For instance, only one MedD study assessed multiple indicators, but it relied on generic LCA databases, reducing contextual accuracy(Reference Sáez-Almendros, Obrador and Bach-Faig27). Similarly, a study on Ugandan diets(Reference Auma, Pradeilles and Blake47) reported moderate environmental impacts but relied on global data, reducing its local validity. Such issues often stem from data constraints but undermine ecological specificity and cultural sensitivity, both of which are essential when evaluating traditional diets(Reference Sáez-Almendros, Obrador and Bach-Faig27,Reference Auma, Pradeilles and Blake47) .

Ideally, environmental assessments should draw on region-specific data that reflect local agricultural practices, production methods and consumption patterns, including home preparation and waste(Reference McLaren, Berardy and Henderson55). Until such data are widely available, LCA-based conclusions about traditional diets should be interpreted with caution.

The NF was used in one study assessing the traditional Japanese diet, which found that greater adherence could significantly reduce nitrogen emissions(Reference Oita, Nagano and Matsuda21). Unlike CF, NF captures reactive nitrogen losses across the food system mainly from fertiliser use and nitrogen-fixing crops, which contribute to air and water pollution, as well as climate change through nitrous oxide (N₂O), a greenhouse gas nearly 300 times more potent than CO₂(Reference Oita, Nagano and Matsuda21,Reference Shibata, Galloway and Leach56) . Globally, agriculture accounts for approximately 75 % of N₂O emissions(Reference McLaren, Berardy and Henderson55).

Originally designed for individuals, NF now applies to institutions worldwide and highlights the environmental cost of protein-rich, fertiliser-intensive diets(Reference Leach, Galloway and Castner57). However, these models typically rely on industrial datasets, often overlooking low-input, seasonal food systems typical of traditional diets. As a result, applying NF without localised data may misrepresent the true environmental footprint of traditional practices.

This limitation is not unique to NF. Most environmental assessment tools, including LCA, draw heavily from datasets based on large-scale, high-input agricultural systems in high-income countries(Reference Poore and Nemecek58). For instance, the Poore and Nemecek database (Reference Poore and Nemecek58), though comprehensive, primarily reflects industrial farm data. Consequently, traditional, low-impact diets remain underrepresented, and the cultural and ecological specificity of traditional food systems is often ignored. Without localised adaptations, integrated carbon-nitrogen tools risk undervaluing the sustainability potential of traditional diets.

The EAT-Lancet dietary guidelines(Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken1) provide a universal reference diet within planetary boundaries, aiming to limit GHGE to 5 gigatonnes of CO2-equivalent per year, nitrogen application to 90 teragrams per year, phosphorus application to 8 teragrams per year and freshwater use to 2500 km3 per year, achieving an extinction rate of ten species years of extinction and reducing cropland use to 13 million km2(Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken1). Even though these global sustainability benchmarks are valuable, they face challenges when applied across diverse populations. For instance, the Portuguese study reported a reduction in CF when diets were adjusted according to these guidelines(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Dias and Moreira37). In contrast, studies in Mexico and India showed varied outcomes: the Mexican diet met only 57·5 % of the targets(Reference Campirano, López-Olmedo and Ramírez-Palacios33,Reference Armes, Bhanjdeo and Chakraborty45) . While the Santal tribe’s diet in India aligned with the sustainability criteria for plant-based foods but lacked animal proteins and dairy products, raising concerns about nutrient adequacy, especially for iodine and vitamin D in an already deficient population(Reference Armes, Bhanjdeo and Chakraborty45). These examples underscore a key limitation: EAT-Lancet targets may not fully reflect local nutritional needs, food availability or cultural dietary patterns. Its one-size-fits-all approach may not fully reflect the diversity of traditional dietary practices shaped by cultural, ecological and economic contexts.

The NRF9.3 Index is a widely recognised measure of diet quality, balancing nine nutrients to encourage with three to limit (added sugar, Na and saturated fat). Despite being identified as the most frequently used nutritional quality tool in a scoping review of eighty-two indicators(Reference Harrison, Palma and Buendia50), it appeared in only two studies in this review(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22,Reference Esteve-Llorens, Dias and Moreira37) .

The application of NRF9.3 has additional relevance for sustainability research, as higher scores have been linked to lower GHGE and alignment with high-quality traditional diets(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22,Reference Reguant-Closa, Pedolin and Herrmann59) . Its ability to measure nutrient density independently of energy intake supports cross-study comparability(Reference Harrison, Palma and Buendia50).

However, the use of NRF9.3 in diverse cultural contexts still remains limited. The application of NRF9.3 may overlook nutrient priorities shaped by local deficiencies, food preparation methods or traditional food combinations. As Drewnowski notes, nutrient profiling models were developed for high-income settings to address obesity, penalising energy-dense foods while ignoring their micronutrient value(Reference Drewnowski, Amanquah and Gavin-Smith60). Applied uncritically in low-income countries, such models risk undervaluing culturally important foods rich in Ca, Fe or high-quality protein. This underscores the need for culturally adapted indices over unmodified global metrics(Reference Drewnowski, Amanquah and Gavin-Smith60). Misalignment between traditional diets and global standards may reflect limitations of the tools rather than shortcomings in the diets themselves. Standardised tools like NRF9.3 and Nutri-Score rely on a reductionist model, focusing on isolated nutrients while ignoring synergistic effects of whole foods, preparation methods and ecological context(Reference Hercberg, Touvier and Salas-Salvadó61,Reference Ortenzi, Kolby and Lawrence62) . In studies by Fardet and Rock(Reference Fardet and Rock63) and Monteiro et al. (Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Levy64), traditional diets often feature minimally processed foods, bioactive synergies and seasonal diversity. Nutrient profiling tools that overlook food matrix effects and cultural preparation methods risk undervaluing traditional diets, sometimes ranking ultra-processed foods such as sweetened cereals above nutrient-dense staples like eggs and whole milk, leading to misclassification of diet quality(Reference Ortenzi, Kolby and Lawrence62).

Nutri-Score, while effective for packaged foods in Europe, depends on per 100 g nutrient data and does no account for mixed dishes or home-prepared meals. Even in France, adaptations were needed for foods such as cheeses and fats to align with national guidelines, showing the need for cultural adjustments(Reference Hercberg, Touvier and Salas-Salvadó61). Nutrient-based tools may misrepresent traditional diets unless mixed dishes are disaggregated into their components. The Saint Kitts and Nevis National Individual Food Consumption Survey (NIFCS) showed that recipe disaggregation changed key food group estimates,(Reference Crispim, Elias and Matthew-Duncan65). Likewise, analysis of Australia’s 2011–12 National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey (NNPAS) demonstrated that breaking down composite dishes improved the accuracy of meat, poultry and fish intake estimates(Reference Sui, Raubenheimer and Rangan66), underscoring the need for local ingredient data. Without cultural adaptation and a local data, nutrient-based tools may misrepresent traditional diets and overlook their true value.

Case studies from Uganda(Reference Auma, Pradeilles and Blake47), Japan(Reference Oita, Nagano and Matsuda21), Romania(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Negrea34,Reference Voinea, Popescu and Bucur35) and India(Reference Armes, Bhanjdeo and Chakraborty45) illustrate how traditional diets are shaped by local environments, nutrient needs and cultural norms. In Uganda, moderate environmental impacts coexisted with a need for higher meat intake among nutritionally vulnerable groups, especially women of reproductive age(Reference Auma, Pradeilles and Blake47). In Japan, a minor change of one meat-free day per week reduced NF without compromising nutritional adequacy(Reference Oita, Nagano and Matsuda21). In Romania, meat-centred traditions posed barriers to sustainability(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Negrea34,Reference Voinea, Popescu and Bucur35) . While the plant-based diet of the Santal tribe in India failed to meet micronutrient needs, raising concerns about iodine deficiency(Reference Armes, Bhanjdeo and Chakraborty45).

These examples highlight the importance of flexibility and cultural sensitivity in dietary recommendations. WHO/FAO and the World Cancer Research Fund guidelines advise limiting red meat to < 71 g/d or 0·5 servings daily(67), but such recommendations must be adapted to population-specific nutritional vulnerabilities. For instance, a Romanian survey (2021–2022, n 1053)(Reference Balan, Gherman and Gherman68) showed high animal product intake (71 %) and low consumption of fruits, vegetables, nuts and fish (77–81 %), raising health and sustainability concerns(67).

Modifying traditional diets to balance global health and sustainability standards while respecting cultural practices can be beneficial. Adapting traditional diets to meet health and sustainability goals can be beneficial, but changes should be cautious and culturally sensitive. While reducing meat and dairy products may lower environmental impact, these foods often supply Ca, Fe vitamin B12 and Zn(Reference Aleksandrowicz, Green and Joy69,Reference Payne, Scarborough and Cobiac70) . Plant-based diets with moderate meat intake can offer environmental benefits(Reference Chai, van der Voort and Grofelnik71), but adequacy depends on local nutrient needs(Reference Chai, van der Voort and Grofelnik71).

This review aligns with previous research interest in adhering to MedD patterns. Although MedD is already extensively studied and therefore did not feature prominently here, its dual benefits shared with the Atlantic diet are evident in the NRD9.3 scores, which indicate high nutritional quality alongside a low CF(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22,Reference González-García, Esteve-Llorens and Moreira52) . Similar studies(Reference Lăcătușu, Grigorescu and Floria28,Reference González-García, Esteve-Llorens and Moreira52) suggest that this stems from their common emphasis on abundant fruits, vegetables, olive oil and fish, combined with simple cooking methods such as boiling and braising. The Atlantic diet differs from the MedD mainly in its stronger focus on local and seasonal foods(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22,Reference González-García, Esteve-Llorens and Moreira52) yet both serve as practical examples of how to balance nutritional quality with environmental sustainability(Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22,Reference Sáez-Almendros, Obrador and Bach-Faig27,Reference Cambeses-Franco, Gude and Benítez-Estévez46) . These predominantly plant-based diets, which limit meat consumption, provide diverse nutrient profiles while demonstrating potential for reducing CF and improving diet quality(Reference Oita, Nagano and Matsuda21,Reference Esteve-Llorens, Darriba and Moreira22,Reference González-García, Esteve-Llorens and Moreira52) .

In our synthesis of studies assessing both nutritional quality and CF, we observed a consistent inverse relationship: higher diet quality was associated with lower CF. This finding is consistent with other reviews(Reference González-García, Esteve-Llorens and Moreira52) that underscore the environmental advantages of the Atlantic and MedD diets. In addition, the Japanese diet, rich in fish, seaweed, vegetables, soya products, green tea and fruit, combines balanced, nutrient-dense eating with a low NF, offering a culturally distinct model of health and sustainability(Reference Oita, Nagano and Matsuda21).

A fundamental limitation of standardised tools is their lack of connection to the lived realities of those consuming traditional diets. Secondary or aggregated data can mask intra-cultural differences, making detailed, population-level data essential. Qualitative research can uncover cultural, generational and practical dimensions of food systems, as shown in studies from Romania and Chile(Reference Voinea, Popescu and Bucur35,Reference Kanter and León Villagra36) . Combining quantitative and qualitative methods, supported by local expertise, is essential to capture intra-cultural differences and guide sustainable, culturally relevant dietary transitions.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this review is its broad scope, enabling a comprehensive global search and critical evaluation of traditional dietary patterns to health and sustainability. It assesses commonly used tools (NRF9.3, Nutri-Score, LCA and EAT-Lancet) and highlights their limitations when applied to traditional diets.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, limitations of this review include the availability of relevant literature, which may have constrained the breadth of evidence identified. In addition, the substantial variation in methods and indicators across studies reduced comparability and prevented the application of a consistent quality appraisal framework.

Second, limitations of the studies reviewed were also evident. Many investigations modelled meals or weekly menus from FAO guidelines, food pyramids or traditional recipes, which may bias results towards healthier dietary patterns and reduce alignment with real-world consumption. Furthermore, heavy reliance on secondary or global datasets, particularly for LCA and NF analyses, reduced contextual accuracy. Region-specific evidence was limited. Studies were either qualitative or quantitative, but none used mixed-methods to capture the full complexity of traditional diets. No study measured actual consumption of traditional foods or assessed dietary change after interventions.

Ongoing trials, such as a sustainable psycho-nutritional intervention currently underway in Mexico(Reference Lares-Michel, Housni and Reyes-Castillo72) as well as the DELICIOUS Project, a five-country school-based intervention promoting MedD adherence and sustainability education(Reference Grosso, Buso and Mata73), signal growing interest in this field; however, the information available at present is limited to study protocols.

Future directions

We recommend future work to develop culturally tailored, mixed-method approaches that integrate quantitative indicators with local knowledge, use region-specific datasets, include the voices of local communities and researchers, and expand environmental metrics beyond greenhouse gases. Such approaches will enable more accurate, context-relevant assessments and guide policies that protect and promote traditional diets.

Conclusion

Traditional place-based diets tailored to local environments have the potential to address both health and sustainability challenges, but not all such diets meet the criteria for health or sustainability.

In many cases, perceived shortcomings reflect the limitations of assessment tools rather than the diets themselves. Standardised nutrient-based or environmental metrics often overlook the cultural, nutritional and ecological complexity of traditional diets. Assumptions about their healthfulness or sustainability should therefore be tested against local nutritional needs, food access and lived realities.

Traditional diets are dynamic and must be evaluated within their social and environmental context. Ideally, desktop evaluation of historical diets should be replaced with regionally adapted evaluations that reflect local food systems, preparation methods and cultural practices. Engaging local researchers and communities would improve accurate and respectful evaluation. A comprehensive approach combining quantitative metrics with qualitative insights into cultural meaning and everyday practices is recommended to fully capture the potential health and sustainability value of traditional diets.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Murray Turner, Team Leader of Research and Information Services in University of Canberra, for his valuable guidance during our systematic review, especially in database searching. Also, the authors would like to thank Ekavi Georgousopoulou for her advice.

Financial support

This study did not receive any external financial support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Ethics of human subject participation

Not applicable.

Authorship

F.A. and R.M. developed research questions and screened studies, N.N. reviewed conflicts. F.A. conducted the literature search, data extraction, and analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to editing and formatting the final manuscript.