Introduction

Today we live in the participation age (Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup2014; Silagadze & Gherghina, Reference Silagadze and Gherghina2020). We witness countless new initiatives such as citizens’ assemblies and agoras in order to further involve citizens in democratic processes. Referendums form the backbone of such participation, giving citizens a direct say in decision-making. However, on certain occasions political actors ask their followers to boycott referendums and refrain from having a say on the proposal. As Pope Benedict XVI said in 2005, four days before the referendum on in vitro fertilization in Italy, ‘What is the principle of wisdom, if not to abstain from all that is odious to god?’ (Altman, Reference Altman2010, p. 23).

There is a large body of literature on how political parties initiate referendums and how they offer cues to citizens during referendum campaigns (e.g., de Vreese & Semetko, Reference de Vreese and Semetko2004; Oppermann, Reference Oppermann2013). There are also studies of electoral boycotts or citizen attitudes toward abstention in referendums, particularly in relation to the effect of turnout quorums (Aguiar-Conraria & Magalhães, Reference Aguiar-Conraria and Magalhães2010b; Hizen, Reference Hizen2021; Hizen & Shinmyo, Reference Hizen and Shinmyo2011; Kouba & Haman, Reference Kouba and Haman2021). However, beyond individual case studies, we know very little on why parties boycott referendums. We study this puzzling aspect; given the pressure to boost citizen participation, what circumstances motivate a political party’s decision to boycott a referendum?

We argue that despite the increasing popularity of citizen participation, the reality is more complex. The context within which a referendum is called matters. For instance, in Macedonia in 2004, the then Prime Minister Hari Kostov urged voters to boycott the vote so it would fail to meet the 50% turnout requirement (Wood, Reference Wood2004). Similarly, in Azerbaijan in 2009, opponents of Azerbaijan President Ilham Aliyev said they would ‘boycott an upcoming referendum that could enable him to remain in power for life’ (VOA, 2009). These quotes demonstrate the importance of the context, specifically democratic politics and institutional design, in motivating political actors to boycott direct democracy.

To offer the first comparative or comprehensive study of political party decisions on referendum boycotts, we build an original dataset of 223 referendums across 37 countries, focussing primarily on the contextual factors that the parties operate within. While our primary focus is on the (non)democratic context and turnout quorums, we control for a battery of other institutional factors such as the number of political parties in the system, referendum’s binding nature, referendum type (mandatory, optional, initiative), and referendum issue (internal policy, foreign affairs, sovereignty, morality issues, constitutional issues, political or electoral system). Based on regression analyses, we find that the democratic status of the country and turnout quorums have an impact on boycott motivations. The presence of quorum requirements is strongly associated with an increased likelihood of referendum boycotts, however our findings also suggest interaction effects. The maturity of democracy in European countries is strongly associated with a reduced rate of referendum boycotts, which largely holds true even in some cases where we might expect quorum requirements to motivate tactical boycotts. In addition, we find hybrid (partly free) systems to have a higher proportion of boycotts than in more and less democratic systems, arguably fueled by the perfect combination of legitimacy concerns and (sufficient) confidence in electoral processes. Finally, we find that, across all systems and institutional settings, referendums on sovereignty issues are significantly more likely to face boycott calls than referendums on any other issue type.

We complement the regression results by offering a further analysis of the context of referendum boycotts by qualitatively coding and categorizing boycott actor justifications. In this deeper analysis, we trace six distinct boycott motivation types and discuss how they relate to contextual and institutional dynamics. More specifically, we find that boycotts in non-democratic systems are largely influenced by legitimation concerns, with opposition parties rejecting referendum processes that are often designed to consolidate or expand the powers of an executive that is perceived to lack democratic legitimacy. In free and partly free systems, on the other hand, referendum boycotts are more commonly driven by the motivation of tactical turnout suppression to defeat or invalidate referendum proposals in the presence of quorum requirements. We also identify and discuss some rarer types of boycotts, those by ethnic minority groups, those fueled by ideological opposition to either ballot measure, and the puzzling case of government-sponsored boycotts.

Below, we first review the literature on direct democracy and participation, with a particular focus on political parties. We then discuss referendum politics through contextual attributes such as democratic status and institutional design. Next, we detail our research design and explain our findings. We conclude with a discussion on future research paths and policy implications.

Understanding non-participation in democratic processes

While political participation is often treated as a democratic ideal, strategic non-participation, particularly by political parties, can serve as a powerful political tool. In electoral contexts, parties often boycott contests to delegitimize a process perceived as unfair or to avoid conferring legitimacy on authoritarian incumbents (e.g., Beaulieu & Hyde, Reference Beaulieu and Hyde2009; Chernykh, Reference Chernykh2014; González-Ocantos et al., Reference González-Ocantos, Jonge and Nickerson2015). Governing parties, in turn, often seek high turnout to bolster legitimacy, especially under international scrutiny. But what are the motivations and conditions for non-participation in referendums?

Referendum boycotts remain underexplored, particularly from a party decision-making perspective. This is striking, given the growing global emphasis on participatory democracy. Scholars argue that citizen involvement is widely seen as normatively desirable, even when its effectiveness is contested (Baiocchi & Ganuza, Reference Baiocchi and Ganuza2017, p. 3). Referendums embody this participatory turn. In democratic regimes, they offer direct input into policy. In non-democratic contexts, however, they are often used to consolidate power or manufacture legitimacy (Fruhstorfer, Reference Fruhstorfer, Albert and Stacey2022; Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup2017; Tierney, Reference Tierney2015).

Yet, why do political parties, key actors in democratic and authoritarian systems alike, choose to boycott referendums rather than participate? These decisions have significant consequences. In Catalonia’s 2017 independence referendum, many unionist voters and parties refused to participate, contributing to a low turnout that weakened the vote’s credibility despite overwhelming support for independence among participants. In Venezuela, the opposition’s boycott of the 2017 Constituent Assembly election failed to block its creation, ultimately enabling President Maduro to expand his authority amid widespread domestic and international criticism. Egypt’s 2012 constitutional referendum faced a boycott from liberal and secular groups who objected to the process, but the constitution was still approved, deepening political divides and paving the way for future instability. Meanwhile, in Crimea, large segments of the population, including Crimean Tatars and ethnic Ukrainians, boycotted the 2014 referendum held under Russian military presence, casting doubt on its legitimacy even as Russia claimed overwhelming support for annexation.

Political parties’ relationship with direct democracy is multifaceted. They are primarily designed to work in a representative system, but they can also gain new opportunities of mobilization in referendums. Existing literature sheds light on how parties initiate referendums (e.g., Closa, Reference Closa2007; Oppermann, Reference Oppermann2013) and guide voter choice (e.g., Atikcan, Reference Atikcan2010; de Vreese & Semetko, Reference de Vreese and Semetko2004; Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2006; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992) but far less is known about the decision to abstain altogether. The literature on party cues in referendums has begun acknowledging that cues are not limited to those that specify which side to vote for, and that they can also influence voters’ decisions to turn out. We know that higher familiarity of voters with the referendum topic boosts turnout (Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2005). Recent studies started exploring the impact of party cues on abstention. For instance, in their study of the 2015 Slovakian referendum, Nemčok et al. (Reference Nemčok, Spáč and Voda2019) find that parties’ recommendations to abstain from voting influence voters’ behavior in a similar way as a yes/no recommendation. Such influence can even be higher in certain institutional settings, where a high turnout threshold is involved.

Party strategies are influenced not only by institutional factors but also by the broader political context. Some scholars have examined this through the lens of interparty dynamics. Vospernik (Reference Vospernik, Morel and Qvortrup2018, pp. 435-436) identifies seven motivations for parties to resort to referendums: to enact policy, ensure survival and unity, shirk responsibility, block policy, mobilize ahead of elections, use as a tactical device in power struggles, and for outsiders to gain a foothold in the political arena. These motives suggest that, depending on who initiates the referendum, parties defending the status quo generally face two options: to actively campaign against the proposal or to boycott it.

A recent example further illustrates how political context, especially in populist and polarized environments, shapes boycott decisions. In the 2023 Polish referendum, the ruling illiberal party held a referendum simultaneously with parliamentary elections, deploying emotionally charged issues to rally supporters and deepen societal divisions (Musiał-Karg & Kapsa, Reference Musiał-Karg and Kapsa2025; Musiał-Karg & Casal Bértoa, Reference Musiał-Karg and Casal Bértoa2025). Opposition parties responded by promoting a selective boycott strategy: encouraging their supporters to vote in the election but abstain from the referendum. This approach served both to delegitimize the referendum and to protest its instrumentalization by the government. Data from Polish citizens abroad showed that strong party identification was a key factor driving abstention, reflecting strategic non-participation rooted in political polarization. These findings support the view that, in illiberal or hybrid regimes, boycotts may function as defensive tactics against democratic erosion, especially when referendums are perceived less as genuine instruments of citizen engagement and more as ‘populist polarizing’ tools. The Polish case thus demonstrates that party-led boycotts are shaped not only by institutional factors, such as turnout quorums, but also by wider concerns about the misuse of direct democracy by dominant political actors.

While there has been significant attention to citizen attitudes toward abstention in referendums (e.g., Gherghina et al., Reference Gherghina, Farcas and Oross2024; Kouba & Haman, Reference Kouba and Haman2021), there is much less written on how political parties approach a referendum boycott decision and in what circumstances they may be more likely to do so. There is no work that studies boycott decisions of political parties comparatively, paying attention to specific factors that shape the context parties operate in. Our argument is that the context within which a referendum is called shapes political party decisions on boycotts. Although there is increasing pressure to involve citizens in democratic decision-making, political parties operate in a context with nuanced institutional dynamics. We aim to capture this context through factors such as democratic status, existence of a turnout quorum, and other institutional arrangements.

To start with the existence of democratic politics, referendums do not function the same way in democratic and authoritarian contexts. There can be unfree referendums where a government uses state power to influence voting and manipulate results (Albert & Stacey, Reference Albert and Stacey2022). These referendums take place in authoritarian or illiberal regimes, where dictators or populists use referendums to increase their power (Bratton & Lambright, Reference Bratton and Lambright2001; Gherghina et al., Reference Gherghina, Farcas and Oross2024; Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup2014). Gherghina et al. (Reference Gherghina, Farcas and Oross2024, p. 17) argue that support for referendums takes different forms in liberal and illiberal contexts. In democracies, citizens’ support for referendums is driven by a dissatisfaction with democracy. In an illiberal setting, citizens associate direct democracy with the initiator, and their attitude toward the referendum depends on their support for the initiator (e.g., Bratton & Lambright, Reference Bratton and Lambright2001). Put differently, citizens’ political engagement determines their support for referendums in democracies, whereas a more passive engagement, citizens’ closeness to the initiator, is the main indicator in illiberal contexts. Political parties mirror these dynamics. In democracies, boycotts often reflect contestation over process, policy, or principles. In authoritarian or hybrid regimes, where referendums are used to entrench executive power, boycotts serve as a tool to withhold legitimacy from a flawed process.

The second factor is the existence of a turnout quorum. Quorums in referendums provide a powerful tool to advance participation. Out of 154 countries with referendum laws, 60 uses such quorums for optional or mandatory referendums (International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, 2020; Kouba & Haman, Reference Kouba and Haman2021, p. 281). Turnout requirements are intended to bolster legitimacy by ensuring broad participation, but they often backfire by incentivizing strategic abstention (Aguiar-Conraria & Magalhães, Reference Aguiar-Conraria and Magalhães2020; Kouba & Haman, Reference Kouba and Haman2021; LeDuc, Reference LeDuc2003; Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup2005). Such quorums exist in many countries around the world, both democratic and non-democratic, and their levels and rules vary substantially (Hizen, Reference Hizen2021). Both citizens and political parties are shown to be strategic in referendums with turnout quorums in order to preserve the status quo (Gherghina et al., Reference Gherghina2019; Kouba & Haman, Reference Kouba and Haman2021). Citizens experience a ‘no-show’ paradox, where they might refrain from voting for the status quo only to avoid helping the pro-change side from helping the necessary turnout (Aguiar-Conraria & Magalhães, Reference Aguiar-Conraria and Magalhães2010b; Fishburn & Brams, Reference Fishburn and Brams1983). Political parties, on the other hand, can adopt a similar strategy due to a parallel ‘quorum paradox’ (Herrera & Mattozi, Reference Herrera and Mattozi2010). The Italian referendums of the 1990s provide clear examples, where abstention often ensured proposals failed by not meeting a quorum (Uleri, Reference Uleri2002). In line with this key example, there is a significant body of work confirming that the use of turnout quorums supresses voter turnout (e.g., Aguiar-Conraria & Magalhães, Reference Aguiar-Conraria and Magalhães2010b; Hizen & Shinmyo, Reference Hizen and Shinmyo2011; Kouba & Haman, Reference Kouba and Haman2021), and suggesting that relatively small quorums are less likely to trigger strategic abstention (Hizen, Reference Hizen2021). These findings are also in line with the policy recommendations of the Code of Good Practice on Referendums, which advise against turnout quorums (Venice Commission, 2022). We therefore expect that political parties have more tactical incentives to boycott when there is a turnout quorum in place, and that this is particularly the case in democratic systems where parties have a reasonable belief that referendum processes will be free and fair, and that turnout will be accurately reported. This is not only because a boycott might allow them a more strategic path to win but also because it would enable them to contest the initiator’s potential legitimacy gain from the use of a turnout quorum.

There are also other institutional arrangements that might affect political party behavior and potentially their motivations for boycotts, and we control for them in our analysis. As discussed earlier, interparty dynamics could shape the thinking of parties (Vospernik, Reference Vospernik, Morel and Qvortrup2018, pp. 435-436). The binding nature of the referendum could be another concern for political parties. They may be more motivated to boycott a legally binding referendum to ensure a stronger impact. Another institutional factor might be the type of the referendum. Political parties might be keener to boycott a referendum that is not mandatory, as this might give them stronger ground to build their case. Finally, the issue of the referendum (e.g., internal or foreign policy, sovereignty, moral or constitutional issues) could influence party motivations. Constitutional referendums, for example, unlike other types of referendums, allow citizens of democratic and non-democratic societies to feel identified with the constitution and consequently with the state (Michel & Cofone, Reference Michel and Cofone2017; Tierney, Reference Tierney2009). In their study of supermajority requirements in referendums, Qvortrup and Trueblood (Reference Qvortrup and Trueblood2023, p. 197) similarly single constitutional referendums out as a key category where such majorities are highly necessary. They argue that referendums on binding constitutional issues should be treated differently because, a) they are about status or standing, and maintaining equality of standing necessitates equal participation of political communities, b) they involve the establishment of a political community for future generations and thereby require the greatest possible degree of consensus. In non-democratic contexts, the picture would be different as most unfree referendums ratify constitutional changes that increase the government’s power by decreasing constitutional limits on the exercise of power (Albert & Stacey, Reference Albert and Stacey2022). Given the high salience and potential implications of constitutional referendum issues, there is therefore a case that they may be more or less likely to be subject to boycotts depending on the context in which they occur. In the following section, we outline our research design.

Theoretical framework and research design

To examine the conditions under which political parties call for referendum boycotts, we adopt a mixed-methods approach that combines quantitative and qualitative analysis. We test two core hypotheses:

H1: Boycotts are more likely in less democratic regimes, where they serve as resistance to authoritarian consolidation.

H2: Turnout quorum requirements increase the likelihood of tactical party boycotts.

First, we employ quantitative regression analyses to assess the significance of the country-level contextual predictors of the occurrence of referendum boycotts identified through our above literature review and theoretical framework. Specifically, we test our theoretical expectation that the type of political system and the institutional/legal design of referendum processes will influence the likelihood of boycott calls at an aggregate level. Second, to deepen this analysis, we conduct a qualitative discourse analysis of boycott justifications, drawing on statements from political actors, civil society representatives, and media sources. In democratic contexts, political parties are typically more inclined to boycott referendums for tactical reasons such as objections to procedural fairness, disagreement with the policy content, or ideological opposition. These boycotts reflect strategic engagement within a functioning democratic system, where parties anticipate that their non-participation will be interpreted as a legitimate form of contestation. Conversely, in non-democratic regimes, boycotts tend to be driven by more fundamental objections to the use of referendums as tools for entrenching executive power. In such cases, referendums are viewed less as instruments of public deliberation and more as mechanisms for legitimizing authoritarian rule, leading opposition actors to withdraw from what they perceive to be a manipulated and illegitimate process.

This multi-method strategy allows us to identify structural patterns while also unpacking the actor-level rationales behind boycotts. Specifically, the quantitative analysis enables us to test for correlations between independent and dependent (boycott occurrence) variables, while the qualitative component enables the corroboration of trends and potential causal patterns, while adding additional depth and richness to our findings (Lieberman, Reference Lieberman2005; Rossman & Wilson, Reference Rossman and Wilson1985). The integration of statistical modeling with discourse analysis enables both breadth and depth, highlighting the interplay between institutional context and strategic behavior. The findings inform a typology of boycott motivations and offer a more holistic understanding of strategic non-participation in referendums.

Data collection – referendum cases

Data for this paper were collected in three stages. First, we used the online Database and Search Engine for Direct DemocracyFootnote 1 to compile a list of all known cases of referendums in Europe from 1972-2023. We then used advanced Google searches to find any mentions of a referendum ‘boycott’ both in English and in the main official language of each country. This gave us 61 confirmed cases of boycotted referendums across 23 European countries with provisions for national referendums. Given our focus on real-world occurrences and instances of strategic non-participation, we adopted a conservative approach to case selection. We included only those boycotts confirmed by at least two independent sources, each clearly naming the boycott actors and referencing an observed or publicized boycott call.Footnote 2 We excluded tentative cases, such as social media posts or opinion pieces by unaffiliated individuals that were not acted upon, as well as unofficial referendums such as the Catalan independence votes, where non-participation by opponents is the expected norm and does not constitute an explicit boycott of a democratic process.

Data collection – contextual & institutional variables

In the second stage of data collection, we collected information on our institutional and democratic status explanatory variables for each confirmed case of referendum boycott, as well as all other national referendums in major European countries from 1972 to 2024 to serve as control cases. The start date (1972) was chosen for pragmatic reasons, as it marks the earliest availability of Freedom House dataFootnote 3 , which is one of our key explanatory variables. This created a total dataset of 223 referendums across 37 countries.Footnote 4 A breakdown of boycotted and non-boycotted referendums by country is presented in Table A1 of the online Appendix. To operationalize the maturity of democratic institutions, we used the Freedom House Democracy index rating of ‘Free’, ‘Partly Free’, or ‘Not Free’, for each referendum year in each country. We operationalized the presence of a quorum as any referendum in which there was either a minimum participation or decision quorum needed to validate the result. While most quorum data were available through the Database and Search Engine for Direct Democracy, we cross-referenced these with media coverage and official government websites where possible. For the institutional design of the direct democratic instrument, we encountered similar classification challenges to those noted by Silagadze and Gherghina (Reference Silagadze and Gherghina2020), due to the absence of a universally accepted typology.Footnote 5 To address this, we created a simplified ‘referendum type’ variable based primarily on the initiator and legal status, categorizing referendums as mandatory, optional, or initiative. In cases of inconsistency between databases, we followed Silagadze and Gherghina’s approach of requiring corroboration from two independent sources (media, government, or academic).

Data on the binding nature of referendums were more consistently available and verified using the same cross-checking method. We also coded a policy domain control variable using a simplified version of Silagadze and Gherghina (Reference Silagadze and Gherghina2020), classifying referendums as internal policy, foreign affairs, sovereignty, morality, constitutional, or political/electoral system-related.Footnote 6 Finally, we added a further control for party system type and party fragmentation using data from Gallagher’s (2024) Election Indices.Footnote 7 While this does not fully capture interparty dynamics, these are explored further in both our regression models and qualitative analysis.

Data collection and method for qualitative analysis – party boycott motivations

In the third stage of data collection, we conducted a qualitative analysis to identify the motivations behind party-led referendum boycotts. We began by collecting statements from boycotting actors, primarily through direct quotes attributed to politicians, party officials, or civil society representatives, sourced from mainstream media during our earlier Google search process. In addition to these primary sources, we included a smaller number of secondary sources, such as academic publications and retrospective media analyses that provided context to the boycott campaigns or cited relevant actor statements. We then conducted a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006) of these statements, manually coding them to identify recurring justifications. Through iterative comparison and refinement, we grouped similar statements into analytically distinct categories. Adopting a data-driven, inductive approach allowed us to explore patterns without bias from theoretical assumptions or the quantitative results. This facilitated the development of an exploratory typology comprising six distinct boycott motivations and helped assess the real-world salience of factors identified in the regression analysis. To mitigate the risk of subjective bias inherent in inductive coding, both authors independently analyzed the data, regularly revisited early classifications, and reached consensus on emerging themes to ensure consistency and transparency.

Regression analysis model specifications

For the statistical analysis, we ran two different models to test for the relationship between democratic and institutional factors and the likelihood of party referendum boycotts. In Table 1, we present the full bivariate and multivariate regression models for our full dataset of 223 European referendums, including the 61 boycotts, using referendums as the unit of analysis. Our dependent variable is a dummy indicating the occurrence of a party boycott. We operationalize democratic freedoms using the Freedom House rating for the referendum year, converted into a numeric scale from 1 (‘not free’) to 3 (‘free’). For quorum, in turn, we use a dummy variable for the presence of any type of quorum requirement.Footnote 8 Control variables include whether the referendum was legally binding (dummy), referendum type and issue area (categorical), and party system type measured by the effective number of parties in the country during the referendum year. For some authoritarian cases, such as Belarus, Azerbaijan, and certain early 1990s Balkan independence referendums, data on effective party numbers was unavailable and coded as zero to reflect the lack of a competitive party system.

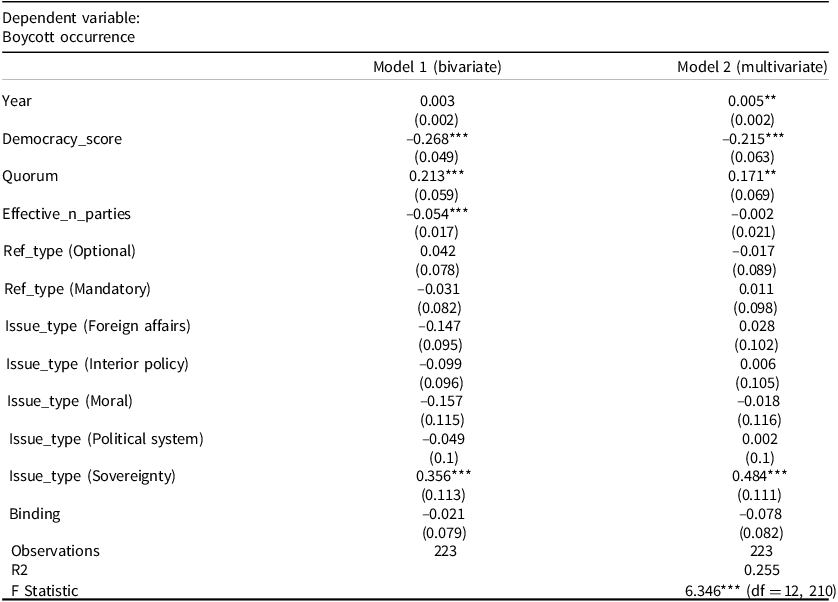

Table 1. Contextual and institutional determinants of referendum boycotts in Europe

Standard errors are in parentheses.

Signif. codes: ***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.1.

In Table 2, we reran the regression using countries as the unit of analysis to control for potential skewing from countries with many referendums, such as Denmark and Ireland, which had numerous referendums but no boycotts. We used the percentage of boycotted referendums relative to total national referendums as the dependent variable. For quorum requirements and binding status, we applied the same dummy variables as before. To test the effect of institutional design, we used counts of mandatory, optional, and initiative referendums per country. Finally, we controlled for party system type and fragmentation by averaging the effective number of parties over the period.

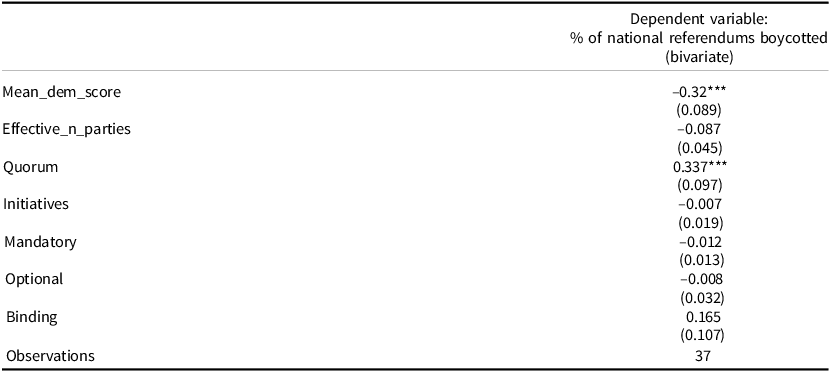

Table 2. Country-level determinants: % of national referendums subject to boycott

Standard errors are in parentheses.

Signif. codes: ***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.1.

Because referendums are still relatively rare events globally, and referendum boycotts are anomalous within those cases, we are conscious that our datasets of 223 cases at the referendum level and 37 cases at the country level potentially stretch the robustness of linear regression due to small sample biasing. To address this, we opted for bivariate analysis of both datasets, while for the larger referendum-level dataset we also compared these bivariate results to a multivariate model. We also used both step-wise and bootstrapping techniques to test the robustness of our multivariate model (results available in the online Appendix) and found consistency in the significance of our key explanatory variables.Footnote 9

Findings – regression analyses

Referendum level findings

Table 1 shows the bivariate and multivariate regression outputs for all 223 referendums, with boycott occurrence as the dependent variable. The findings reveal several key insights into the contextual drivers of boycotts at both country and referendum-levels of analysis. First, they show that boycott occurrences are largely unaffected by referendum type (mandatory, optional, or initiative) across the 37 countries analyzed. Interestingly, whether a referendum is binding has little impact on boycott calls. To some extent this runs against our expectations that parties may be more inclined to tactically boycott binding referendums. However, this may be influenced by two factors. In more authoritarian contexts, boycotts tend to stem from government legitimation concerns rather than tactical opposition to policies. In many democracies, on the other hand, non-binding referendums are often treated by elites as politically binding, as seen in UK referendums on the Alternative Vote (2011), Scottish Independence (2014), Brexit (2016), and three Dutch referendums.

Our first major positive finding supports H1, and H2, whereby both quorum requirements and democracy scores significantly predict boycott occurrence. Higher democracy scores, indicating more established democracies, correlate with fewer boycotts. Conversely, quorum presence strongly increases boycott likelihood, aligning with the theory that quorums encourage tactical boycotts to suppress turnout and invalidate unfavorable outcomes. While the effective number of parties is significant in the bivariate model, suggesting more parties reduce boycotts, its significance disappears in the multivariate analysis, likely due to its correlation with democracy scores, as countries with more parties tend to have higher democracy ratings.

Beyond confirming H1 and H2, the regression models reveal an unexpected finding: referendums on sovereignty issues are much more likely to face boycott calls than other types. While the statistical analysis adopted in this paper does not enable us to propose clear causal mechanisms to explain this, we suggest that the high-stakes identitarian and legitimacy dynamics inherent to sovereignty referendums may be key factors (Atikcan et al., Reference Atikcan, Nadeau and Bélanger2020; Stockwell, Reference Stockwell2025). As Goers et al (Reference Goers, Cunningham and Balcells2024) explain, boycotts are common features of sovereignty referendums and often stem from overlapping concerns about the illegitimacy of the parent state, or proposed territorial changes/concessions, as well as from internal divisions between groups within movements that may hold conflicting or contradictory autonomist demands. We explore these motivations manifest in the explicit justifications of boycott actors in the following qualitative analysis.

To test the robustness of these findings we reran the full referendum-level regression with 223 cases using both stepwise and bootstrapping methods (Tables A3 and A4 in the online Appendix). The stepwise regression eliminates all but the democracy score and quorum presence explanatory variables, while the bootstrapping shows confidence intervals excluding zero only for democracy score, quorum, and sovereignty referendum types. These findings, therefore, further confirm our H1 and H2 hypotheses enabling us to reject the null hypotheses.

Country level findings

Table 2 presents the country-level regression using the percentage of national referendums boycotted as the dependent variable. Consistent with Table 1, only quorum presence and mean democracy score are significant,Footnote 10 supporting H1 and H2: boycotts are less likely in more established democracies and more likely where quorums exist. Interestingly, when we reran a multivariate analysis of Table 2 using the categorical ‘Free’, ‘Partly Free’, and ‘Not Free’ statuses from the Freedom House index (based on the mode of these ratings across the time period), we find the ‘Partly Free’ status to be the most significant positive predictor of boycotts. We suggest that a mix of legitimacy concerns and some confidence in free and fair processes creates ideal conditions for tactical boycotts. This pattern is largely driven by post-communist Eastern European countries with quorum rules, especially Ukraine, Montenegro, Serbia, and Moldova, where 60–100% of referendums since independence have faced party boycotts.

Government boycotts of referendums

The vast majority of referendum boycotts in our dataset were boycotted by opposition actors (80%). Government boycotts, on the other hand, are somewhat rare, perhaps unsurprising given most referendums in our dataset are either optional referendums called by the government or mandatory referendums triggered by constitutional changes proposed by incumbents. Of the 63 confirmed cases of referendum boycotts we identified, only 6 were called by government actors. Three of these were in Italy, the 1991 referendum on the repeal of preferential votes, the 2011 referendums on water privatization and nuclear power, and the 2016 referendum on offshore oil drilling. The only other cases of government boycotts in Europe since 1972 were in the 2004 Macedonian autonomy referendum, the 2004 minority rights referendum in Slovenia, and the 2023 referendum in Slovakia on the calling of an early snap election. All of these cases were triggered by citizen initiatives, with the exception of the 2004 Slovenian referendum, which was called as a result of pressure from a coalition of right-wing opposition parties (Toplak, Reference Toplak2006). While this finding is somewhat intuitive, as governments would be unlikely to boycott referendums initiated by themselves or constitutionally required for their own policy objectives (for example, EU accession), it does highlight an important potential conflict between representative and direct democratic policy-making in countries which allow for citizen’s initiatives. The way in which governmental actors justify calling boycotts of citizen-initiated policy-making is discussed in the following section.

Summary of key quantitative findings

Collectively, these regression analyses offer several key insights into the factors driving political actors to call for referendum boycotts. Our findings suggest that high-stakes sovereignty issues are the most likely to face boycott calls in referendums, while institutional and contextual factors of democratic freedom and procedural direct democratic design (quorums) are also key drivers of boycott likelihood in a cross-national perspective. Specifically, we firstly find consistent evidence that the presence of quorum requirements is strongly associated with an increased likelihood of referendum boycotts. This supports our second hypothesis (H2) and aligns with previous research suggesting that quorums can unintentionally suppress turnout by incentivizing parties to strategically encourage non-participation to invalidate unfavorable outcomes.

Second, we find that higher levels of democratic maturity correlate with fewer boycotts, even in countries like Denmark and Portugal that impose a 50% turnout quorum but have seen no boycott cases during the time period under study. Conversely, we see different dynamics at play in the somewhat unique case of Italy, where eight out of the 24 referendums since 1972 were subjected to explicit boycott or abstention campaigns by major political actors, despite Italy’s consistently high rating of democratic freedoms. While statistical analysis alone cannot fully explain these country-specific anomalies, both visual and qualitative examination of our dataset suggest that Italy’s frequent use of citizen initiatives, combined with its quorum rules, has led to the institutionalization of strategic abstention by parties to manage referendum-driven policy pressures (see also Uleri, Reference Uleri2002).Footnote 11 In the following section, we take a more qualitative actor-centered approach to further unpack how the contextual and institutional factors driving referendum boycotts that were identified in this section interact with, and shape, the explicit boycott justifications of parties and political actors.

Findings – boycott actor justifications

The quantitative analyses presented above identified several key determinants of referendum boycotts such as quorum requirements, regime type, and issue area. In this section, we turn to qualitative data to unpack the mechanisms behind these statistical relationships. We show how these contextual and institutional variables appear directly in the stated justifications of boycotting actors and explore cases where motivations extend beyond the scope of our regression model. To achieve this, we identify themes by coding the explicit statements or secondary post-hoc explanations of boycott actor justifications in a thematic analysis, tracing key examples of different types of boycott motivation and how the institutional and contextual factors we compared in the above analysis shape these dynamics. Aligning with our hypotheses, our initial coding approach was to identify themes or explicit statements relating to the use of referendums as a legitimizing tool for authoritarian or hybrid regimes, or statements that explicitly or implicitly called for tactical boycotts or abstention in cases where specific turnout quorums were required. As we outline below, these were in fact the most common justifications of boycott actors in authoritarian and democratic systems respectively. Our qualitative analysis also found, however, some additional themes in the statements of boycott actors that suggest a greater degree of nuance and a broader range of possible boycott motivations where legitimacy and fairness concerns overlap with tactical motivations.

Specifically, we find that explicit boycott actor justifications are shaped most prominently by national context, and in particular, by the level of democratic freedoms and the related confidence that opposition groups and parties have in the legitimacy of the government or referendum initiator, and in the fairness of electoral processes. Conversely, we find that free and partly free countries (but crucially not in non-democracies) which have quorum requirements, boycotting parties are often explicitly motivated by tactical turnout suppression in order to invalidate the referendum result, thereby maintaining a preferred status-quo position.

In established democracies without quorum requirements (where boycotts are rarest), we also find that some boycotts may have largely ideological motivations, such as in the cases of the 2016 UK Brexit referendum and the 2015 bailout referendum in Greece, both of which were boycotted by left-wing parties on the grounds that either choice on the ballot paper represented a continuation of a neoliberal consensus. Below we outline the six common types of boycott motivations that we identified through the thematic analysis and discuss how these motivations interact with the contextual factors of democratic freedom quorum requirements, and referendum issue type. An important caveat of this section is that we acknowledge there may be an overlapping dimension to party boycott motivations as statements from boycott actors could in some cases fit into two or more categories. These categories are therefore not mutually exclusive, but rather represent the range of commonly presented justifications for boycotts in European referendums. We begin by discussing two types of boycott motivation most commonly found in non-democracies or hybrid regimes, which we grouped as ‘(de)legitimation of authoritarian regimes’ and ‘uneven playing field/rigged vote’ boycotts. We then discuss occurrences of highly context specific instrumental boycotts that were not captured in the quantitative analysis, often driven by, or in objection to, narrow party-political interests. Following this, we discuss the most common boycott type found in free and partly free countries, relating to explicit motivations of tactical ’turnout suppression’ in contexts that required participation quorums. Finally, we discuss two rarer forms of boycott motivation, we define these as ‘minority interest’ boycotts, which appear most common in sovereignty, secession, and independence referendums, and ‘ideological’ boycotts, driven by ideological objections to both ‘yes’ and ‘no’ positions on the referendum ballot.

(De)legitimization of authoritarian regimes

As outlined above, we find a significant number of boycotts in countries that are rated ‘not free’ by the Freedom House index, which were motivated by concerns that referendum processes were being used to legitimate authoritarian regimes and, in particular, concerns that referendums were being used to consolidate power in the hands of authoritarian governments. In the 2005 Armenian constitutional referendum, for example, a coalition of 17 opposition parties called for a boycott of the referendum ‘because the vote is a pretence of democracy. The former Foreign Minister Raffi Hovanissian, also joined the call for a boycott, describing the government as a “regime that supports thieves, murderers, and corrupt individuals”’ (Parsons, Reference Parsons2005). Another notable example of this boycott type can be found in a statement issued by Azerbaijan’s Classic Popular Front Party in the build up to a 2016 constitutional referendum which would have granted several new powers and an extended term to the incumbent president. The boycotters argued that ‘the proposed amendments to the Constitution, expanding the already vast powers of the president, serve for the perpetuating the reign of the current government. In addition, there is no real separation of powers: legislative, and judicial authorities have turned into an appendage of the executive’ (Turan, 2016)

A final clear example of this type of boycott motivation can be found in the 2022 Belarussian referendum on constitutional change that critics argued would further cement the (illegitimate) powers of the government and, in particular, President Lukashenko (Kuznetsov, Reference Kuznetsov2021). Opponents, including Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, a candidate in the 2020 Belarussian Presidential election, called on voters to ‘disrupt the referendum by spoiling the ballots. In this way, in their opinion, Belarusians will be able to demonstrate their disagreement with the country’s authorities, turning the referendum into a ‘vote of no confidence’ in the regime’ (Perunovskaya, Reference Perunovskaya2021). These statements support our finding that lower democracy scores are associated with a higher likelihood of boycotts, particularly in non-democratic or hybrid regimes.

Uneven playing field/rigged votes

A related, although substantively different explicit boycott motivation that we find often presented alongside legitimation concerns, again largely in countries rated not free or partly freeFootnote 12 , is claims by opposition groups that the electoral process would not be free and fair, or that the process would be rigged in favor of a preferred government outcome. We find explicit motivations of this kind in four of the boycotts in our dataset including the 2000 constitutional referendum in Ukraine which was subject to a boycott call by Peter Simonenko, the then leader of the Ukrainian Communist Party, on the grounds that the result could strip the independence of the Parliament (BBC News, 2000), but while also accusing the government of falsifying the results (Blagov, Reference Blagov2000). A second example of this, is again in Azerbaijan, where a group of 30 opposition parties threatened to boycott the 2000 referendum on an array of constitutional reforms, because political parties were not granted equally free access to television and radio, and that there was insufficient independent monitoring of the electoral process (Radio Free Europe, 2002).

Instrumental use/party interests

A third type of boycott justification was observed in several cases in which the explicit justification of the referendum boycott was a rejection of the instrumental use of referendums, usually to further the (electoral) interests of the governing party. Although related to legitimation boycotts, we suggest that the focus of boycotting parties in these incidences is distinct enough to warrant a separate category. Specifically, while in both cases boycott actors question the legitimacy of referendum processes designed to benefit ruling incumbents, boycotting actors in this subset of cases focussed more on discrediting the instrumental use of boycotts in service of the initiating parties’ electoral interests, rather than on the illegitimacy of the referendum as a tool for consolidating executive powers in office. As such, the cases in this category of referendum boycott occurred largely in backsliding or illiberal democracies, rather than in purely authoritarian systems. Recent examples of this boycott type include the 2013 Bulgarian referendum on the building of a new nuclear plant, which was boycotted by the Bulgaria for Citizens party on the grounds that is was being used by the ruling GERB and main opposition Socialist Party ‘to serve their narrow party interests’ and, specifically, ‘as a sounding of public opinion ahead of the 2013 parliamentary elections’ (Novinite, 2013). Another more recent high-profile example of this type of boycott can be found in the 2023 Polish referendum on the sale of state assets, retirement age, and illegal immigration. In this case, a successful boycott campaign was mounted by the opposition against the ruling Law and Justice Party (PiS) on the grounds that the referendum was being used cynically to both mobilize and polarize the electorate, a strategy that PiS believed would be electorally beneficial both in the referendum and subsequent parliamentary elections (Musiał-Karg & Casal Bertoa, Reference Musiał-Karg and Kapsa2025; NFP, 2023).

Turnout suppression

We now turn to the most frequent type of boycott justification in established and emerging (post-communist) European democracies. 13 out of 61 confirmed cases of referendum boycotts in our dataset fall into this category. In these cases, we find that the boycotting party’s motivations often explicitly cite an aim of driving down turnout in an attempt to invalidate any referendum result by keeping it below the quorum, thus maintaining a status quo preferred by the boycotting party(s). A clear example of this came in the 2003 Polish referendum on EU membership, in which ‘Self-Defence and the League of Polish Families, (were) actively endorsing a boycott in hopes of defeating the referendum’ (Finn, Reference Finn2003). Similarly in the 2018 referendum on gay marriage in Romania, there are several reports of opposition figures and human rights groups calling for a boycott ‘in the hope the turnout fell below the 30% needed to validate the referendum’ (BBC News, 2018). Some referendum boycotts in this category come with more implicit justifications that focus on the potential negative effects of a policy change, thus framing abstention as the safest option, rather than explicitly mentioning the aim of driving down turnout. An example of this is the 2016 abrogative initiative on offshore oil drilling, in which, rather than suggest a ‘no’ vote, Prime Minister Renzi ‘urged the public to boycott the poll, arguing that ending drilling rights would increase Italy’s dependence on imported energy’ (DW, 2016). This aligns with our regression finding that quorum requirements are a strong and significant predictor of boycott likelihood.

We find these boycott dynamics to be particularly prominent in Italy, including a high proportion of citizen’s initiatives and government-led boycott campaigns. In addition to the 2016 referendum on offshore oil drilling, another example occurred in 1991 in the Italian referendum on the repeal of preferential votes, in which Donovan (Reference Donovan1995: 55) explains that ‘The referendum result was also significant in that both Craxi and Bossi made a rare strategic mistake; they called for a boycott of the referendum, hoping that less than half the electorate would turn out, thus nullifying the ballot’.

Minority interest boycotts

A smaller number of referendum boycotts in our dataset appear to be motivated by minority and minority-ethnic group interests. Specifically, minority opposition parties in some referendums justify their boycotts because of a perception that insufficient concern has been paid to their minority group interests. This includes representation of ethnic and minority groups in the referendum process itself, but also arguments from these groups that any new settlement reached in the event of a policy change post-referendum would inadequately address their concerns and interests. We find that sovereignty referendums make up a high proportion of this type of boycott motivation, with many cases occurring in former Yugoslav countries. One clear example is the boycott of the 1991 Macedonian independence referendum by ethnic Albanians ‘in protest against their perceived inferior constitutional status’ (Widner, Reference Widner2004). Similar cases which contest the parent-state defined status of ethnic, regional, or autonomist interests in the aftermath of sovereignty referendums can be found in the Basque, Catalan, and Andalusian autonomy referendum boycotts of 1979 and 1980. Boycott motivations of this type were also expressed, however, in some instances of constitutional amendment referendums where the status of minority groups was to be (re)negotiated. A key example of this is the 2010 constitutional referendum in Turkey, in which ‘The pro-Kurdish Peace and Democracy party (BDP) had called for a boycott, saying the package failed to address the grievances of Turkey’s estimated 14 million Kurds’ (Tait, Reference Tait2010).

Ideological boycotts

Finally, the most minor type of boycott motivation we identify, both in terms of frequency and the magnitude of the boycott itself, is what we term ideological boycotts. We find this justification in only three cases in our dataset but consider the explicit motivations of the boycotting parties to be clear and different enough from all other motivations to warrant including as a distinct category. In each of these cases, generally fringe far-left parties call for boycotts of national referendums (all without any quorum requirements), on the grounds that either outcome from the referendum process would perpetuate a neoliberal consensus, thus calling on voters to abstain from legitimizing either option with a vote and pursuing class struggle politics through other means. The three examples we find of this type of boycott motivation are the boycott of the 1992 French Maastricht Treaty referendum by minor communist and Trotskyist parties including Lutte Ouvrière (Austin, Reference Austin2005), the boycott of the 2015 Greek bailout referendum by the KKE (Savas, Reference Savas2015), and the boycott of the 2016 Brexit referendum in the UK by the Socialist Equality Party (WSWS, 2016).

While the regression model reveals broad institutional and contextual patterns, particularly regarding democratic quality and quorum rules, our qualitative analysis captures additional motivations, such as ideological objections and minority grievances, that elude purely institutional explanations. Together, the two approaches offer complementary insights: the quantitative analysis identifies structural trends, while the thematic coding reveals how actors frame, exploit, or resist these conditions in practice. Although some boycott motivations, particularly those related to ideology or minority grievances, fall outside the scope of our regression model, the overall alignment between the two approaches strengthens the comprehensiveness of our explanatory framework.

Conclusion

This paper examines the paradox of party-led referendum boycotts in an age that celebrates participation. We first present a novel dataset tracking all referendum boycotts across Europe since 1972. Second, our regression analysis identifies institutional conditions, specifically democratic maturity, quorum rules, and regime type, under which parties are more likely to promote boycotts. Third, our qualitative thematic coding of publicly-stated justifications offers a six-part typology of boycott motivations. These findings emphasize the importance of framing. While the regression models reveal broad structural patterns, our qualitative analysis shows how parties leverage these structures in discourse, as part of campaign framing, aligning with Snow and Benford’s (Reference Snow and Benford1988) insights on interpretive shortcuts in political messaging.

Our mixed-methods findings reinforce established theoretical insights on institutional design and democratic context. The negative association between established democratic regimes and boycott likelihood aligns with theories of democratic consolidation (e.g., Linz & Stepan, Reference Linz and Stepan1996) which suggest that entrenched democratic norms reduce incentives for delegitimizing democratic processes through boycott. Conversely, the strong positive association between quorum rules and boycotts supports the contention of Uleri (Reference Uleri2002) and Hizen (Reference Hizen2021) that such requirements may inadvertently encourage strategic abstention, suppressing participation despite their intent to bolster it (Aguiar-Conraria & Magalhães, Reference Aguiar-Conraria and Magalhães2010a).

Crucially, we observe interaction effects. In consolidated democracies, boycotts are typically tactical, aimed at turnout suppression or ideological resistance, while in authoritarian or hybrid regimes, they reflect deeper legitimacy crises. This aligns with Qvortrup’s (Reference Qvortrup2019) distinction between democratic and plebiscitary referendum use and extends Smith’s (Reference Smith2014) work on electoral boycotts in hybrid regimes. Our findings therefore nuance existing theories of electoral and referendum boycotts by emphasizing the mediating role of regime type and institutional design. Our qualitative analysis further supports this distinction by identifying common rhetorical justifications used by parties across regime types. In authoritarian contexts, parties frequently denounce referendums as tools of authoritarian legitimation or protest electoral manipulation (‘uneven playing fields’), while in backsliding or hybrid democracies, boycotts often respond to what actors perceive as the instrumental use of referendums for partisan gain. These narratives reflect a broader logic of strategic delegitimation.

These findings invite a wider rethinking of how referendum boycotts relate to democratic legitimacy, party behavior, and strategic non-participation. Rather than treating boycotts solely as signs of democratic backsliding or protest, our results show that parties may use them tactically, to challenge, exploit, or adapt to institutional constraints. In both democratic and authoritarian settings, boycotts serve as part of a strategic repertoire, allowing parties to pursue goals through abstention, invalidation, or delegitimation of participation itself.

Unexpectedly, we find little evidence that referendum content or type (e.g., mandatory, initiative, binding) systematically predicts boycott behavior. This suggests that institutional and national context outweigh issue salience or legal form. Yet, our typology identifies two analytically distinct and rare forms: ‘minority interest’ boycotts, especially in sovereignty referendums involving ethnic exclusion, and ‘ideological’ boycotts, where fringe parties reject both ballot options as reinforcing a dominant consensus. These highlight the symbolic and expressive dimensions of boycott behavior, especially where formal engagement is seen as ineffective.

However, the one clear exception is sovereignty referendums, which emerge as a distinct and consistent predictor of boycott behavior. Both the quantitative and qualitative findings suggest these referendums generate uniquely high-stakes contexts, often triggering boycotts rooted in identity-based disputes, legitimacy contests, and minority exclusion. This is particularly evident in post-communist and multinational states, where questions about the constitutional status of minority communities intensify perceived unfairness. We also identify occasional government-led boycott calls in initiative referendums within established democracies, especially in Italy, highlighting tensions between representative and participatory logics. These cases reveal an underexplored source of institutional conflict and inform wider debates on the strategic use of direct democracy by incumbents.

These rich, and at times counterintuitive, findings open important avenues for research. Comparative small-N case studies could further unpack the causal mechanisms behind boycott motivations and contextual contingencies. Extending our dataset globally would test the generalizability of institutional and contextual explanations. Moreover, exploring interparty dynamics and potential domino effects in boycott mobilization could deepen our understanding of strategic coordination in these campaigns.

Finally, our study carries normative and policy implications. Referendums in democratic systems provide settings where abstention can be more effective than voting (Gherghina et al., Reference Gherghina2019), While turnout is often seen as a marker of legitimacy (e.g., Arnesen et al., Reference Arnesen2019; Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup2005), our results highlight how institutional design, specifically quorum requirements, can paradoxically incentivize strategic abstention, thus distorting democratic outcomes (Hizen, Reference Hizen2021; Uleri, Reference Uleri2002). In such cases, abstention functions as a counter-majoritarian veto, challenging assumptions that participation is inherently democratic. These dynamics suggest the need to critically reassess referendum design, particularly turnout thresholds and quorums. More broadly, we demonstrate how institutional, contextual, and discursive factors interact to shape boycott strategies, reaffirming that abstention is not mere apathy, but a strategic political act embedded in regime-specific logics.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773925100301.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Louis Stockwell], upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Aimee McColgan for her work in bringing together the dataset that enabled this study. We would also like to thank the editors of this special issue, Sergiu Gherghina and Matt Qvortrup, for their feedback on early versions of this work, along with the participants of the 2024 Glasgow workshop on political parties and direct democracy, where our ideas for this study were first presented. Finally, we are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for helping to sharpen this study through their suggestions.

Funding statement

The authors would like to thank the Department of Politics and International Studies at the University of Warwick for their generous research support.

Competing interests

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.