Non-technical Summary

Porpoises are small whales closely related to dolphins. Today, harbor porpoises and several other whale species live in the waters off the eastern United States. This study reports the first porpoise fossils ever found in the western North Atlantic Ocean. The fossils comprise four ear bones discovered on beaches near Charleston, South Carolina. These bones likely came from rock layers that are about 3–5 million years old, during a period called the Pliocene when the climate was warmer than today and sea levels were higher. The ear bones are particularly valuable to scientists because they contain unique features that help identify different species. Using micro-CT scanning technology similar to medical scanners, we created a detailed three-dimensional model of the inner ear structures of one of the fossils. Scans revealed that the extinct porpoises had specialized hearing adaptations for detecting high-frequency sounds, similar to modern porpoises that use echolocation to navigate and hunt. The discovery fills an important gap in our understanding of when and how porpoises first arrived in Atlantic waters. Porpoises likely originated in the Pacific Ocean and later spread to other parts of the world. These South Carolina fossils represent some of the earliest evidence of porpoises in the Atlantic, suggesting they dispersed here much earlier than previously thought.

Introduction

In the present day, harbor porpoises (Phocoena phocoena Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1758) as well as other odontocetes (e.g., Tursiops Gervais, Reference Gervais1855; Stenella Gray, Reference Gray1866; Lagenorhynchus Gray, Reference Gray and Gray1846; Physeter Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1758; Pseudorca Reinhardt, Reference Reinhardt1862; Globicephala Lesson, Reference Lesson1828) are relatively common in the western North Atlantic (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Best, Mannocci, Fujioka and Halpin2016, Reference Roberts, Yack and Halpin2023). However, porpoises are absent from the fossil record of this area, which complicates reconstruction of their diversification, dispersal, and paleobiogeography. Phocoenidae are known in the fossil record from the late Miocene (~10–11 Ma) onward, with the earliest known representative Salumiphocaena stocktoni Wilson, Reference Wilson1973 (Barnes, Reference Barnes1985) appearing in the Monterey Formation in California, USA. To our knowledge, 16 extinct species have been described in the past 50 years (Colpaert et al., Reference Colpaert, Bosselaers and Lambert2015; Murakami et al., Reference Murakami, Shimada, Hikida and Hirano2012a; Racicot et al., Reference Racicot, Deméré, Beatty and Boessenecker2014), with most Miocene–Pliocene taxa reconstructed as stem phocoenids. The majority of late Miocene to early Pliocene phocoenid fossils have been reported from the eastern Pacific (California, Mexico, and Peru; see, e.g., Barnes, Reference Barnes1984; de Muizon, Reference de Muizon1984, Reference de Muizon1988; Boessenecker, Reference Boessenecker2013; and Racicot et al., Reference Racicot, Deméré, Beatty and Boessenecker2014) and northern Japan (Ichishima and Kimura, Reference Ichishima and Kimura2000, Reference Ichishima and Kimura2005, Reference Ichishima and Kimura2009; Murakami et al., Reference Murakami, Shimada, Hikida and Hirano2012a, Reference Murakami, Shimada, Hikida and Hiranob; Tanaka, Reference Tanaka2016; Tanaka and Ichishima, Reference Tanaka and Ichishima2016). The origin of Phocoenidae is thus thought to lie somewhere in the southeast or northeast Pacific Ocean (Fajardo-Mellor et al., Reference Fajardo-Mellor, Berta, Brownell, Boy and Goodall2006; Colpaert et al., Reference Colpaert, Bosselaers and Lambert2015) with subsequent dispersal events allowing them to spread into the Northwest and South Pacific at some point during the late Miocene and Pliocene. The first dispersal of early phocoenids into the North Atlantic happened in the Early to early Late Pliocene via the Central American Seaway (Fajardo-Mellor et al., Reference Fajardo-Mellor, Berta, Brownell, Boy and Goodall2006), or alternatively via the Arctic and Bering Strait (Colpaert et al., Reference Colpaert, Bosselaers and Lambert2015). This was followed by a second trans-arctic immigration event of phocoenids such as Phocoena phocoena in the late Pliocene to Pleistocene (Lambert, Reference Lambert2008). Extant phocoenids comprise six genera and seven species found in both hemispheres occupying diverse marine and freshwater environments, including pelagic, coastal, and riverine habitats (Read, Reference Read, Würsig, Thewissen and Kovacs2018; Committee on Taxonomy, 2025). Although a single species lives in the North Atlantic today, not a single phocoenid has been reported from Pliocene or Pleistocene rocks in the western North Atlantic, despite abundant records of other marine mammals (e.g., Whitmore and Kaltenbach, Reference Whitmore and Kaltenbach2008). The discovery of phocoenid fossils from this region sheds further light on trends in changes to their diversity through time.

The cetacean ear

The cetacean periotic is highly diagnostic and a rich source of anatomical features used in taxonomy and phylogenetic analyses (Kasuya, Reference Kasuya1973; Fordyce, Reference Fordyce1994; Mead and Fordyce, Reference Mead and Fordyce2009; Ekdale et al., Reference Ekdale, Berta and Deméré2011). The high preservation potential of the periotic permits the study of cetacean faunal diversity through time even when well-preserved skulls and skeletons are not known (Kellogg, Reference Kellogg1931; Barnes, Reference Barnes1977; Whitmore and Kaltenbach, Reference Whitmore and Kaltenbach2008). The inner ear of mammals in general is affected by high levels of evolutionary and functional constraints (Billet et al., Reference Billet, Hautier, Asher, Schwarz, Crumpton, Martin and Ruf2012). Therefore, variation in shape and size of the bony labyrinth, the hollow space inside the periotic housing the soft tissue structures that allow hearing and balance senses to operate, is regarded to be not significant (Martins et al., Reference Martins, Park, Racicot and Cooper2020). This allows the study of a single specimen for deducing taxonomic and functional implications as has been done in numerous previous studies on extant and fossil mammals (e.g., Spoor et al., Reference Spoor, Garland, Krovitz, Ryan, Silcox and Walker2007; Ekdale and Racicot, Reference Ekdale and Racicot2015; Racicot et al., Reference Racicot, Gearty, Kohno and Flynn2016, Reference Racicot, Darroch and Kohno2018; Ruf et al., Reference Ruf, Volpato, Rose, Billet, de Muizon and Lehmann2016). The auditory sense of Odontoceti is a highly adapted orientation system in terms of underwater navigation and foraging by echolocation (Ketten, Reference Ketten, Webster, Fay and Popper1992; Klima, Reference Klima, Niethammer, Krapp, Robineau, Duguy and Klima1994; Schulze, Reference Schulze1996; Geisler et al., Reference Geisler, Colbert and Carew2014). Ketten and Wartzok (Reference Ketten, Wartzok, Thomas and Kastlein1990) proposed that the development of the auditory sense had proceeded not only in adaptations to life underwater but also with specific adaptations to different habitats (coastal, offshore, and so on). More recent studies proposed that the cochlear shape and the morphology of the surrounding periotic can be used as a determinant for ecological preferences. In particular, the length of the cochlear canal as well as the size and shape of the pars cochlearis of the periotic may serve as proxies for marine or riverine habitats (Gutstein et al., Reference Gutstein, Figueroa-Bravo, Pyenson, Yury-Yañez, Cozzuol and Canals2014; Costeur et al., Reference Costeur, Grohé, Aguirre-Fernández, Ekdale, Schulz, Müller and Mennecart2018).

Here we describe four isolated beach-cast periotics and the bony labyrinth of one of these (CCNHM 1913) found on Folly Beach and in dredge spoils along the Stono River in coastal South Carolina, USA. The periotics preserve several diagnostic external anatomical characters of Phocoenidae and the genus Phocoena in particular. We use micro-computed tomography (μCT) scanning to reconstruct a three-dimensional (3D) model of the bony labyrinth to further test this interpretation. Assessing the affinity of the fossils improves our understanding of marine ecosystems through a dynamic interval of the Neogene and sheds light on the origins and dispersal of a major odontocete clade.

Geological setting

The four fossil periotics described in this study were collected ex situ on Folly Beach and from dredge spoils along the Stono River near Charleston in coastal South Carolina (Fig. 1). Given both that this is the first marine mammal material described from this locality and the lack of mapped submarine outcrops along the shoreline, the precise age of the periotics is uncertain. Fossils have been regularly found ex situ on Folly Beach after being accidentally delivered during a 2014 beach renourishment that sourced Holocene sand (and presumably Miocene–Pleistocene sediment and bedrock) from four federal borrow areas approximately 6–7 km east southeast of the Folly Beach Pier. No core samples exist for the borrow areas, but terrestrial fossils of Pleistocene age (land mammals, birds, turtles, alligators) and marine vertebrate and invertebrate fossils of Pliocene age (mollusks, echinoderms, sharks, bony fish, sea turtles, cetaceans, pinnipeds) are common, and rare shark and marine mammal fossils of older Miocene and Oligocene age are also encountered. In the subsurface, core samples in the area suggest the presence of, from oldest to youngest, the Oligocene Ashley Formation, the lower Miocene Marks Head Formation, the Pliocene Goose Creek Limestone, and the upper Pleistocene Wando Formation (Weems et al., Reference Weems, Lewis and Lemon2013).

Figure 1. Illustration of the locality (starred) at which the ex situ Phocoena sp. periotic specimens (CCNHM 1913, 4018, 5996, and 7906) were found. For a variety of reasons, we consider that the periotics were most likely sourced from the Goose Creek Limestone Formation (lower Pliocene; see discussion in “Geological setting”). Stratigraphic column inset modified from Edwards et al. (Reference Edwards, Gohn, Bybell, Chirico, Christopher, Frederiksen, Prowell, Self-Trail and Weems2000).

For several reasons, however, we consider the periotics to be most likely derived from the Goose Creek Limestone. Principal among these is that large blocks of Goose Creek Limestone are common on Folly Beach and are richly fossiliferous, preserving, among other things, a distinctive mollusk fauna (including Ostrea coxi Gardner, Reference Gardner1945; Placunanomia plicata (Tuomey and Holmes, Reference Tuomey and Holmes1857); Chesapecten septenarius (Say, Reference Say1824); Carolinapecten eboreus Conrad, Reference Conrad1833; Ecphora quadricostata (Say, Reference Say1824)). Moreover, in other localities, outcrops of Goose Creek Limestone preserve material belonging to marine mammals (Boessenecker et al., Reference Boessenecker, Boessenecker and Geisler2018). Derivation from older units such as the lower Miocene Marks Head Formation (~18 Ma) is unlikely as this unit pre-dates the entire fossil record of Phocoenidae. Given that these specimens are identified to the extant genus Phocoena (see the following), derivation from the overlying late Pleistocene Wando Formation is possible, but the marine mammal assemblage looks to be Pliocene. Virtually all marine mammal remains with adhering matrix found on Folly Beach exhibit light gray calcarenite matching the lithology of the Goose Creek Limestone, and other lithologies have not been found in association. Further, some marine mammals are clearly extant genera (e.g., Tursiops, Phocoena) already known from the Pliocene (and could possibly be Pleistocene), but many are also extinct taxa (e.g., cf. Astadelphis Bianucci, Reference Bianucci1996; Herpetocetus Van Beneden, Reference Van Beneden1872; Kogiidae Gill, Reference Gill1871 “cf. Aprixokogia” Whitmore and Kaltenbach, Reference Whitmore and Kaltenbach2008; “Balaenoptera” borealina Van Beneden, Reference Van Beneden1880) unique to Pliocene deposits (e.g., Yorktown Fm., North Carolina; Pliocene of Italy; Bianucci, Reference Bianucci1996; Whitmore and Kaltenbach, Reference Whitmore and Kaltenbach2008). Last, the Pleistocene Wando Formation is typically a nonmarine unit, and all remains clearly originating from this unit consist of terrestrial mammals, turtles, and alligators (Sanders, Reference Sanders2002; Weems et al., Reference Weems, Lewis and Lemon2013). One specimen was derived from a spoil pile along the bank of the Stono River (CCNHM 7096), where Pliocene fossils (including those with adhering Goose Creek Limestone matrix) are common but Pleistocene land mammals are exceedingly rare (R. W. Boessenecker, personal observation, 2018–2023), further suggesting derivation of these periotics from the Goose Creek Limestone. Discovery of specimens with adhering matrix will be required to test this hypothesis.

The Goose Creek Limestone is a medium- to coarse-grained quartzose and phosphatic gray-white calcarenite and is divisible biostratigraphically into lower and upper units coincident with an unconformity (Weems et al., Reference Weems, Lemon, McCartan, Bybell and Sanders1982; Campbell and Campbell, Reference Campbell and Campbell1995). Near Charleston, the Goose Creek Limestone underlies marls belonging to the Raysor Formation (see Campbell and Campbell, Reference Campbell and Campbell1995), which has been dated to 3.6–3.1 Ma from planktonic foraminifera corresponding to zone PL3 (see Tseng and Geisler, Reference Tseng and Geisler2016). A Pliocene age for the Goose Creek Limestone was established by Weems et al. (Reference Weems, Lemon, McCartan, Bybell and Sanders1982) and Campbell and Campbell (Reference Campbell and Campbell1995) on the basis of mollusk faunas and was confirmed by Bybell (Reference Bybell1990) on the basis of nannoplankton indicating an assignment to zone NN16–NN14, which elsewhere has been dated to 3.9–3.6 Ma (Tseng and Geisler, Reference Tseng and Geisler2016). However, the fossil periotics described here and other fossils confirmed or presumed to originate from the Goose Creek Limestone are likely to be late Pliocene (Piacenzian) in age because of the occurrence of Ostrea coxi (Gardner, Reference Gardner1945). Owing to their ex situ discovery, a Pleistocene age for the phocoenid periotics cannot be ruled out; however, all the Pleistocene fossils from Folly Beach found thus far are of terrestrial mammals, reptiles, and birds, and a Pleistocene origin is unlikely.

Materials and methods

Specimens

A complete left periotic (CCNHM 1913) was analyzed using μCT. Specimen CCNHM 1913 was collected ex situ by Andrew W. Wallace on 18 June 2017 on Folly Beach (South Carolina, USA). The external morphology of two additional periotics (CCNHM 4018, collected 12 February 2018 by Don Pendergrast; CCNHM 5996, collected 8 January 2020 by Tracy Burlison) from Folly Beach and a single specimen (CCNHM 7906, collected 21 August 2021 by Robby Jackson) from dredge spoils along the Stono River (South Carolina, USA) are also reported (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Periotics of Phocoena sp. from Folly Beach, South Carolina, USA. (1–4) Left periotic in (1) dorsal, (2) ventral, (3) lateral, and (4) medial views (specimen CCNHM 1913). (5–8) Left periotic in (5) dorsal, (6) ventral, (7) lateral, and (8) medial views (specimen CCNHM 7906). (9–12) Right periotic in (9) dorsal, (10) ventral, (11) lateral, and (12) medial views (specimen CCNHM 5996). (13–16) Right periotic in (13) dorsal, (14) ventral, (15) lateral, and (16) medial views (specimen CCNHM 4018). Scale bars = 5 mm.

μCT scanning and segmentation

Specimen CCNHM 1913 was μCT scanned at the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences of Vanderbilt University (Nashville, Tennessee, USA) using the North Star Imaging μCT scanner. The μCT slices have a resolution of 16.7 μm isometric voxel size; a voltage of 81 kV and a current of 83 μA were used. The exposure time was 266.667 ms. The tomography system was equipped with a Varian PaxScan detector (size 2,000 × 1,600 pixels). The digital endocast of the bony labyrinth was digitally segmented using Avizo v. 9.0.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific FEI, Waltham, MA USA). Mainly “brush” and “blow” were used as selection tools.

Measurements and PCA

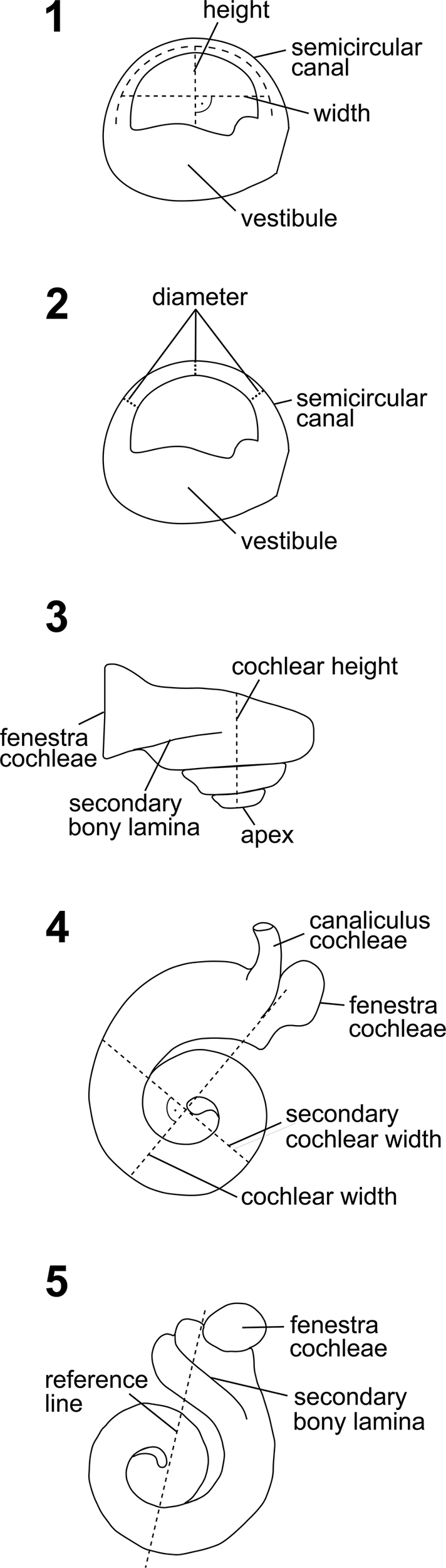

Measurements of the semicircular canals were performed with Avizo v. 9.0.1. The radii of curvature were determined by measuring the inner and outer heights and perpendicular inner and outer widths of each canal (Fig. 3.1), averaging these to obtain the heights and widths as would be measured from the center of each canal and then calculating the radius using the formula 0.5 × (height + width)/2 (Ruf et al., Reference Ruf, Volpato, Rose, Billet, de Muizon and Lehmann2016, modified from Schmelzle et al., Reference Schmelzle, Sánchez-Villagra and Maier2007). The arc diameter was calculated by measuring the thickness of the canal at three sections (anterior limb, middle, posterior limb) as the distance between the inner and outer curvature of the canal in its plane (Fig. 3.2); the resulting values were averaged.

Figure 3. Outlines of some cochlear and semicircular canal measurements redrawn from Ekdale (Reference Ekdale2013). (1) Measurement section of the semicircular canal height and perpendicular width for calculating the radius of curvature. (2) Measurement sections of the semicircular canal diameter (tube thickness). (3) Measurement section of the cochlear height. (4) Measurement section of the cochlear width and perpendicular secondary cochlear width. (5) Reference line used to calculate the number of cochlear turns.

The angles between two canals were measured using the “plane method” following Racicot et al. (Reference Racicot, Darroch and Kohno2018) and were compared with the supplementary data table (table S3) of that paper. The planes were inserted manually using the “Oblique Slice” module from Avizo. Afterward, snapshots of the perpendicular planes were exported as .tif files, and the angles were measured with the open-access imaging software ImageJ v. 2.0.0-rc68. In short, the average deviation from 90° of each angle is the basis to calculate 90var; this is calculated by adding the deviation values from 90° of each angle and dividing them by three (Malinzak et al., Reference Malinzak, Kay and Hullar2012; Berlin et al., Reference Berlin, Kirk and Rowe2013; Ekdale and Racicot, Reference Ekdale and Racicot2015; Racicot et al., Reference Racicot, Gearty, Kohno and Flynn2016, Reference Racicot, Boessenecker, Darroch and Geisler2019).

Nine cochlear measurements were taken to examine the hearing sensitivity of this specimen (following Churchill et al., Reference Churchill, Martinez-Caceres, de Muizon, Mnieckowski and Geisler2016; Mourlam and Orliac, Reference Mourlam and Orliac2017; Galatius et al., Reference Galatius, Olsen, Steeman, Racicot, Bradshaw, Kyhn and Miller2019; Racicot et al., Reference Racicot, Darroch and Kohno2018, Reference Racicot, Boessenecker, Darroch and Geisler2019) in the context of a principal components analysis (PCA). The measurements for this analysis comprise cochlear height (Ch) (Fig. 3.3), cochlear length (Cl), cochlear width (Cw) and cochlear width perpendicular to Cw (W2) (Fig. 3.4), interturn distance at the first quarter turn of the cochlea (ITD), surface area of the fenestra cochleae (FC), spiral ganglion width at the first quarter turn (GAN), and the number of turns (#T) (Fig. 3.5). Most measurements were taken using Avizo v. 9.0.1; the endocast and the original data were exported as an .stl file and transferred to VGStudio MAX v. 2.2 (Volume Graphics GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) for additional measurements. To calculate the surface area of the fenestra cochleae (FC), the vertical and horizontal radii were measured and entered into the common formula for an elliptic plane (A = π · r · r). The number of cochlear turns (#T) was obtained by counting the number of crossings of a line that goes through the proximal laminar gap and the axis of rotation. It is reported in number of turns #T = (times of crossings · 180° + angle of apex coil)/360°. The spiral ganglion canal width at the first quarter turn (GAN) was not preserved in specimen CCNHM 1913 and thus could not be measured.

To provide a clearer picture of phocoenid hearing sensitivity overall, measurements from Racicot et al. (Reference Racicot, Gearty, Kohno and Flynn2016) were added to the PCA dataset. The missing measurements from that dataset (SBL, W2, FC) were measured directly in VGStudio MAX v. 2.2 (using the polyline length tool) or Avizo v. 9.0.1 on the following added species: Neophocoena asiaorientalis Pilleri and Gihr, Reference Pilleri and Gihr1972, Phocoena dioptrica Lahille, Reference Lahille1912, Phocoena sinus Norris and McFarland, Reference Norris and McFarland1958, Phocoena spinipinnis Burmeister, Reference Burmeister1865, Phocoenoides dalli True, Reference True1885, Haborophocaena toyoshimai Ichishima and Kimura, Reference Ichishima and Kimura2005, Miophocaena nishinoi Murakami et al., Reference Murakami, Shimada, Hikida and Hirano2012a, Numataphocoena yamashitai Ichishima and Kimura, 2000, Piscolithax boreios Barnes, Reference Barnes1984, Piscolithax tedfordi Barnes, Reference Barnes1984, Semirostrum ceruttii Racicot et al., Reference Racicot, Deméré, Beatty and Boessenecker2014, and an undescribed phocoenid fossil (UCMP 128285).

Additional measurements and calculations not used for the PCA, but useful for additional inference of cochlear function, include the axial pitch (Ap = Ch/#T), basal/aspect ratio of the cochlear spiral (Br = Ch/Cw), cochlear slope (Cs = Ch/Cl/#T), and the product of cochlear length and number of cochlear turns (CT = C · #T). These measurements were taken and calculated following Racicot et al. (Reference Racicot, Gearty, Kohno and Flynn2016). The ratio of cochlear length and secondary bony lamina length (%SBL = SBL/Cl) was calculated using the method of Ekdale and Racicot (Reference Ekdale and Racicot2015). Morphometric data from our bony labyrinth sample were compared with those of Racicot et al. (Reference Racicot, Gearty, Kohno and Flynn2016). To evaluate similarities and differences between the measurements and calculations, values from the Racicot et al. (Reference Racicot, Gearty, Kohno and Flynn2016) supplementary data that lie within 10% deviation from our bony labyrinth measurements were considered to be a match. Both higher and lower deviation values resulted in too large or too small numbers of matches that could not be interpreted unequivocally.

To evaluate the external periotic morphology, the distances between the fenestra cochleae, the perilymphatic foramen, the endolymphatic foramen, and the internal acoustic meatus were measured for specimen CCNHM 1913 following Luo and Marsh (Reference Luo and Marsh1996).

For increased accuracy, all measurements were performed three times and averaged for subsequent analyses. The measurements were performed directly on the surface of the endocast (i.e., semicircular canal measurements), on the three-dimensional model of the periotic (i.e., FC), or on selected μCT images (i.e., all cochlear measurements excluding FC and all periotic measurements).

To visualize the hearing ranges of CCNHM 1913 alongside other artiodactyls, we analyzed measurement data via a PCA that builds on an original study by Mourlam and Orliac (Reference Mourlam and Orliac2017) that was subsequently expanded by Racicot et al. (Reference Racicot, Darroch and Kohno2018, Reference Racicot, Boessenecker, Darroch and Geisler2019) and Racicot and Preucil (Reference Racicot and Preucil2022). All analyses were performed in the open-access statistical software R (R Core Team, 2020). The PCA was performed using the FactoMineR package (Lê et al., Reference Lê, Josse and Husson2008); following previous work (Mourlam and Orliac, Reference Mourlam and Orliac2017; Galatius et al., Reference Galatius, Olsen, Steeman, Racicot, Bradshaw, Kyhn and Miller2019; Racicot et al., Reference Racicot, Darroch and Kohno2018, Reference Racicot, Boessenecker, Darroch and Geisler2019; Racicot and Preucil, Reference Racicot and Preucil2022), any measurements that could not be obtained from the μCT scans were imputed, using the missMDA package (Josse and Husson, Reference Josse and Husson2016), although missing data were very few—less than 1% of the total measurements. Following Mourlam and Orliac (Reference Mourlam and Orliac2017), PCAs were performed on ranked (rather than raw) measurements.

Repository and institutional abbreviation

Figured specimens examined in this study are deposited in the Mace Brown Museum of Natural History (CCNHM), College of Charleston, Charleston, South Carolina, USA.

Results

Periotic description

The anatomical description of the fossil periotic CCNHM 1913 follows a combination of the terminology used by Luo and Marsh (Reference Luo and Marsh1996) and Mead and Fordyce (Reference Mead and Fordyce2009). The whole periotic, including the bony labyrinth, is well preserved and almost completely intact (Fig. 4). Specimens CCNHM 1913, 4018, 5996, and 7906 are not appreciably different from one another; therefore the following description applies to all specimens. From the anterior view (also visible in ventral and medial views), the anterior apex of the periotic is parted by a shallow groove (Fig. 4.2, 4.3). In the posterior direction, there is no tympanic breakage visible (Fig. 4.2, 4.3). The ventrolateral tuberosity of the periotic is located anterolateral of the fossa for the head of the malleus and posteriorly of the anterior bullar facet (Fig. 4.2, 4.3). The hiatus epitympanicus is positioned between the ventrolateral tuberosity and the posterior process. It extends until the medially located fossa incudis (Fig. 4.2, 4.3). The fossa for the head of the malleus and the fossa incudis are both well pronounced. The groove for the musculus tensor tympani flanks the anterior process medially and the promontorium laterally. It is prominent and proceeds almost to the fossa for the head of the malleus (Fig. 4.2).

Figure 4. Isosurface renderings of the left periotic of Phocoena sp. (CCNHM 1913) from different views. (1) Dorsal (cranial) view. (2) Ventral (tympanic) view. (3) Medial view. (4) Lateral view. aap = apex of anterior process; abf = anterior bullar facet; acm = area cribrosa media; ap = anterior process; app = apex of posterior process; ca = cochlear area; ct = crista transversa; elf = endolymphatic foramen; fai = foramen acousticum inferius; fas = foramen acousticum superius; fc = fenestra cochleae; fi = fossa incudes; fm = fossa for malleus; fs = foramen singular; fv = fenestra vestibuli; gtt = groove for tensor tympani; he = hiatus epitympanicus; iam = internal acoustic meatus; pc = pars cochlearis; pf = posterior facet for articulation with tympanic bone; plf = perilymphatic foramen; pofc = proximal opening of facial canal; pp = posterior process; pr = promontorium; tsf = tractus spiralis foraminosus; tu = ventrolateral tuberosity. Scale bar = 10 mm.

The promontorium, the bulged ventral surface of the pars cochlearis, appears to be elongated from medial view (Fig. 4.3). It is well rounded but slightly elliptic from ventral and dorsal views (Fig. 4.1, 4.2). From anterior or posterior view, it shows an elliptical shape. The distance between the fenestra cochleae and the perilymphatic foramen is about 2.14 mm (Fig. 4.3). Both are located on the medial side of the pars cochlearis. The internal acoustic meatus opens dorsally, containing the dorsally opening tractus spiralis foraminosus. The latter is shallow and opens wide (Fig. 4.1). Together with the perilymphatic foramen and the endolymphatic foramen, the internal acoustic meatus forms a triangular shape (Fig. 4.1). The area within this triangle is planar. The distances between the three characters are as follows: 3.08 mm between endolymphatic foramen and perilymphatic foramen, 3.00 mm between perilymphatic foramen and internal acoustic meatus, 3.09 mm between endolymphatic foramen and internal acoustic meatus. The internal acoustic meatus is subdivided by the crista transversa into the lateral foramen acusticum superius, housing the proximal opening of the facial canal, and the medial foramen acusticum inferius, with three distinct openings: the spiral cribriform tract, the area cribrosa media, and the foramen singulare (Fig. 4.1). Recently, homology of the foramen singulare of cetatceans and other mammals has been re-evaluated by Ichishima et al. (Reference Ichishima, Kawabe and Sawamura2021) and Orliac et al. (Reference Orliac, Orliac, Orliac and Hautin2020).

The posterior process of the periotic is peg-shaped and tapering from lateral and medial view (Fig. 4.3, 4.4). It seems to be bent slightly ventrally. The surface of the posterior facet appears to be smooth.

Identification and comparisons of external features

CCNHM 1913, 4018, 5996, and 7906 preserve all or most of the six characteristics of crown phocoenids (the clade containing all extant porpoises: Phocoena, Neophocaena, and Phocoenoides) identified by Kasuya (Reference Kasuya1973): (1) loss of ridges and grooves on the posterior bullar facet (except for CCNHM 4018, which has some poorly defined striations); (2) a posterior bullar facet that is anteroposteriorly longer than it is wide; (3) anterior and posterior processes that are anteroposteriorly aligned and with the posterior bullar facet facing ventrally rather than anteroventrally; (4) a subtriangular pars cochlearis (subjective and difficult to evaluate but clearly present in CCNHM 1913, less clearly present in 4018 and 5996); (5) a crista transversa deeply recessed into the internal acoustic meatus; and (6) no spongiosa anywhere in the posterior process.

We further identify four additional features that appear to unite crown phocoenids and are also preserved in these four specimens: (7) a transversely narrow anterior process that is rectangular in ventral view; (8) an anterodorsal angle of the anterior process that is much larger than the anteroventral angle and forms an acute angle in medial/lateral view; (9) fenestra cochleae widely separated from the fenestra vestibuli and stapedial muscle fossa; (10) fenestra cochleae positioned anteriorly with its anterior margin overlapping with the fenestra vestibuli.

The four South Carolina specimens are morphologically distinct from all nominal extinct phocoenids on the basis of the 10 characters described above. These specimens differ from Miophocaena nishinoi in characters 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, and 10; the periotic of Miophocaena nishinoi is much more robust with an inflated, subrectangular anterior process, a dorsoventrally thick outline, convex lateral margin, and a shallower posterior process. Similarly, Numataphocoena yamashitai possesses a distinctly massive periotic lacking a deep anterior incisure and bearing a transversely and dorsoventrally thick and globose anterior process and a large, spherical lateral tuberosity, and further differing in characters 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, and 10. Haborophocoena toyoshimai possesses a relatively large and delphinid-like periotic with a proportionally large and transversely massive anterior process, and a leaf-shaped posterior bullar facet with posterolateral point; it further differs from these specimens in characters 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, and 10.

The South Carolina taxa differ from Pterophocaena nishinoi in characters 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 10; Pterophocoena possesses a much longer and laterally directed posterior process. These specimens differ from Salumiphocoena stocktoni in characters 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, and 10; Salumiphocoena further exhibits a much larger lateral tuberosity. Semirostrum ceruttii possesses an absolutely small periotic with a proportionally short and conical anterior process, and large pars cochlearis; it further differs from these specimens in characters 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, and 10. These specimens differ from Lomacetus ginsburgi de Muizon, Reference de Muizon1986 in characters 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 10; Lomacetus possesses a transversely wider anterior process and a rounder, wider internal acoustic meatus. They also differ from Australithax intermedia de Muizon, Reference de Muizon1988 in characters 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 8, and Australithax further differs in possessing a particularly medially shifted fenestra rotundum, a furrow between the caudal tympanic process and the fenestra rotunda, and a nearly circular internal acoustic meatus.

Last, these specimens differ from Piscolithax spp. in most regards; from Piscolithax boreios in characters 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, and 10, from Piscolithax tedfordi in characters 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 8, and from Piscolithax longirostris de Muizon, Reference de Muizon1983 in characters 2, 4, 7, 8, and 10. The periotics of these species are surprisingly dissimilar from one another but further differ from the South Carolina specimens; Piscolithax tedfordi has a more anteroposteriorly compact periotic, and Piscolithax boreios bears a short, globose, and dorsoventrally thick anterior process and a triangular posterior apex of the posterior process. Piscolithax longirostris also differs in possessing an anterior process with a rectangular medial profile.

The specimens described compare best with Phocoena phocoena and do not differ appreciably from one another. These specimens differ from Neophocaena in having a proportionally smaller pars cochlearis and a proportionally larger posterior bullar facet that laterally overlaps the fenestra vestibuli. These specimens differ from Phocoenoides dalli in having an excavated dorsal margin of the posterior process (also in all other species of Phocoena) and in possessing an anteriorly shifted posterior bullar facet laterally overlapping the position of the fenestra vestibuli. These specimens differ from Phocoena sinus in having a longer anterior process and a quadrate rather than triangular posterior bullar facet with a straight lateral margin. These specimens differ from Phocoena dioptrica in possessing a narrower posterior bullar facet that overlaps with the fenestra vestibuli. These specimens differ from Phocoena spinipinnis in having a less extremely excavated dorsal surface of the posterior process, lacking a tubercle around the aperture for the cochlear aqueduct, and having a more medially prominent and subtriangular rather than low pars cochlearis.

The periotics strongly differ from those of all published extinct phocoenids, which are frequently more delphinid-like in morphology; extinct phocoenids typically have fewer than half of the above cited features (Kasuya, Reference Kasuya1973; this study) that characterize most crown Phocoenidae. Given the combination of features and favorable comparison with Phocoena spp., these periotics are best identified as Phocoena sp. More precise identification is not attempted owing to incompleteness.

Bony labyrinth description

The anatomical description of the bony labyrinth of CCNHM 1913 follows the terminology used by Racicot et al. (Reference Racicot, Gearty, Kohno and Flynn2016). The entire bony labyrinth is preserved, but the internal acoustic meatus is incomplete.

The semicircular canals are distinctively small and well preserved. The posterior canal is the smallest of all three (radius of curvature = 0.53 mm) and shows an arcuate, symmetric form (Fig. 5.1; Table 1). The lateral canal is the largest of all the canals (radius of curvature = 0.74 mm) and presents a highly asymmetric shape (Fig. 5.3). While the posterior canal is oriented nearly planar, the anterior canal shows a slight medial bend in anterior view (Fig. 5.1). The lateral semicircular canal undulates dorsally. The tube diameters of the three semicircular canals do not differ significantly from each other (ASC = 0.29 mm, PSC = 0.28 mm, LSC = 0.30 mm).

Figure 5. Isosurface renderings of the digital endocasts of the bony labyrinth of Phocoena sp. (CCNHM 1913) from (1) anterior, (2) medial, (3) dorsal, and (4) vestibular views. ap = apex; asc = anterior semicircular canal; cc = canaliculus cochleae; co = cochlea/cochlear canal; fc = fenestra cochleae; fv = fenestra vestibuli; lsc = lateral semicircular canal; pbl = primary bony lamina; psc = posterior semicircular canal; sbl = secondary bony lamina; ve = vestibule. Scale bar = 5 mm.

Table 1. Averaged measurement results and calculations of the semicircular canals, used for the description and comparison of specimen CCNHM 1913. Please refer to the Appendix 1 for a detailed measurement listing. scc = semicircular canal

The angle between the anterior and the posterior canals is by far the widest at 110.99° (Table 1). The angle between the anterior and the lateral semicircular canals is the smallest (85.95°). The calculated 90var value is 10.51°.

The canaliculus cochleae is located close to the fenestra cochleae and proceeds in a dorsoposterior direction. It is separated by a narrow groove from the fenestra cochleae (Fig. 5.3; Table 2). The latter opens lateroventrally and extends in an elliptical shape (Fig. 5.4). The fenestra vestibuli opens out from a ventral position. It has a round aspect although it is neither a fine circle nor an ellipse. The cochlea has about one and a half turns and appears to be planispiral. From a dorsal or ventral view, the turns are clearly overlapping although they do not cover each other completely, and a cochlear hook is recognizable (Fig. 5.3, 5.4). The spiral ganglion canal width at the first quarter turn (GAN) was not preserved in specimen CCNHM 1913 and thus could not be measured (Fig. 6).

Table 2. Averaged measurement results and calculations of the cochlea, used for the description and comparison of specimen CCNHM 1913. Please refer to the Appendix 1 for a detailed measurement listing. scc = semicircular canal

Figure 6. μCT scan slices of periotic of Phocoena sp. (CCNHM 1913). (1) Slice showing internal structures such as cochlear canal, bony laminae, and others. (2) Slice through cochlear canals and canaliculus cochleae. (3) Slice showing both vestibular and cochlear regions of the bony labyrinth. (4) Slice through two semicircular canals and other features. Scale bars = 5 mm.

A prominent section at the cochlear base reflects a thick and wide secondary bony lamina, which extends almost half of the basal turn and becomes thinner and less wide in the course of the cochlear canal (Fig. 5.2). The primary bony lamina, at the opposing side of the cochlear canal, is as distinctive as the secondary lamina although it is incomplete and ends after about one quarter turn in this specimen (Fig. 5.4). The cochlear width is almost twice the cochlear height, which is also reflected in the aspect ratio of the cochlear spiral (0.54). The secondary bony lamina has a length of 23.87 mm and is therefore almost as long as the cochlear canal, with 24.92 mm.

Identification and comparisons of bony labyrinth features

Given the potential for intraspecific variation and measurement error in fossil material, we used a conservative 10% threshold to identify morphological overlap consistent with possible generic affinity while acknowledging this represents a practical rather than statistically derived cutoff. Measurements within this range are referred to as “matches.”

In terms of identification based on bony labyrinth characteristics, the semicircular canals of CCNHM 1913 are distinctively small, similar to Phocoena phocoena (Racicot et al., Reference Racicot, Gearty, Kohno and Flynn2016, fig. 3). In dorsal view, the position and proximity of the canaliculus cochleae and the fenestra cochleae resemble those of juvenile and adult Phocoena phocoena, Phocoena dioptrica, and Phocoena spinipinnis (Racicot et al., Reference Racicot, Gearty, Kohno and Flynn2016, fig. 5). In anterior view, the cochlear canal dorsal of the secondary bony lamina features a different shape in each specimen. This area is rather straight in specimen CCNHM 1913 and more like Phocoena sinus. Whereas most specimens examined in Racicot et al. (Reference Racicot, Gearty, Kohno and Flynn2016) show a ventrolaterally or anteroventrally directed fenestra vestibuli, the one of specimen CCNHM 1913 opens out almost completely ventrally. Conveniently, Phocoena phocoena is one of these specimens. However, Phocoenoides dalli does not match with CCNHM 1913 in terms of the expected range of measurements in this comparison. Besides Phocoena phocoena, there are also some extinct Phocoenidae (Harborophocoena toyoshimai; Numataphocoena yamashitai; Piscolithax boreios; Semirostrum ceruttii) and even some Monodontidae Gray, Reference Gray1821 (Delphinapterus leucas (Pallas, Reference Pallas1776); Monodon monoceros Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1758), and Delphinidae Gray, Reference Gray1821 (Cephalorhynchus commersonii (Lacépède, Reference Lacépède1804)) that share a maximum of three matches with CCNHM 1913 (anterior/posterior, posterior/lateral, and anterior/lateral semicircular canal angles, deviations of anterior/posterior and lateral/posterior semicircular canals angles from 90°, 90var).

A comparison of all cochlear measurements we collected, plus basal ratio and axial pitch values from Racicot et al. (Reference Racicot, Gearty, Kohno and Flynn2016) and Churchill et al. (Reference Churchill, Martinez-Caceres, de Muizon, Mnieckowski and Geisler2016), also revealed similarities with specimen CCNHM 1913. Two species can be highlighted in their morphometric similarity to CCNHM 1913: Phocoena phocoena and Phocoenoides dalli. Concerning Phocoena phocoena, most matches occur with both juvenile specimens at a maximum of eight matches (Cl, #T, Br, Ch, Cw, Ct, Ap, Cs) while both adult specimens show two matches maximum (Cl, Cw). With an average of 5.5 matches, both Phocoenoides dalli specimens appear to be similar to CCNHM 1913 as well. The only reference value that did not match with any specimen was the product of cochlear length and number of cochlear turns. The value that comes closest is similar to the Phocoena phocoena juvenile specimens with about 45.55 (approximately 12% deviation from the value we measured).

PCA analysis of bony labyrinth

CCNHM 1913 plots within the morphospace of odontocetes that specialize in narrow-band high-frequency (NBHF) sound production and reception (i.e., 125–140 kHz) (Fig. 7). The inclusion of Neophocoena asiaeorientalis Pilleri and Gihr, Reference Pilleri and Gihr1972 increases the size of the convex hull surrounding the NBHF species compared with previous results, and this area now includes the majority of extinct and extant phocoenids. Some extinct phocoenid specimens do not plot within the extant NBHF morphospace (Haborophocoena toyoshimai; Miophocoena nishinoi, Numataphocoena yomashitai, and specimen UCMP 128285); however, they still plot rather closely, and only one inner ear (the right side) of H. toyoshimai plots outside of this morphospace. Pterophocaena nishinoi Murakami et al., Reference Murakami, Shimada, Hikida and Hirano2012b, the earliest-diverging phocoenid, and Salumiphocaena stocktoni, the oldest known phocoenid, both still plot within the NBHF morphospace. Other taxa plot in positions that correspond with those of previous analyses, such as the positioning of terrestrial artiodactyls and mysticetes with presumed infrasonic hearing abilities.

Figure 7. Principal components analysis (PCA) of nine cochlear measurements with variables factor maps inset. The black star indicates the position of CCNHM 1913 among other echolocating odontocetes. Yellow convex hull outlines extant narrow-band high-frequency (NBHF) specialists. The dataset has been modified from Racicot and Preucil (Reference Racicot and Preucil2022) to include the cochlear measurement data from this study and that of Racicot et al. (Reference Racicot, Gearty, Kohno and Flynn2016). (1) Full analysis showing all species. (2) Close-up of morphospace, including all phocoenids. Data point species/specimen abbreviations in Appendix 2. T = number of cochlear turns; FC = fenestra cochleae surface area; Ch = cochlear height; Cl = cochlear length; Cw = cochlear width; W2 = secondary cochlear width; ITD = inter-turn distance; SBL = secondary bony lamina; GAN = spiral ganglion canal.

Discussion

Western North Atlantic Pliocene Phocoenidae

The richly fossiliferous Yorktown Formation at the Lee Creek Mine in eastern North Carolina has produced the most diverse and well-studied marine mammal assemblage of Pliocene age on Earth, including diverse odontocetes, many representing clades that are still extant in the North Atlantic (Whitmore and Kaltenbach, Reference Whitmore and Kaltenbach2008), although recent phylogenetic analyses suggest some generic assignments may require revision (Citron et al., Reference Citron, Geisler, Collareta and Bianucci2022). Published studies have not yet recovered any evidence of phocoenids. It is possible that future collecting may produce tympanoperiotics or skull fragments of phocoenids, and scores of uncatalogued ear bones from this unit await identification and study in USNM collections (D.J. Bohaska, personal communication, 2019). However, given the large sample from the Yorktown Formation, it is possible, if not likely, that the Yorktown Formation was deposited before the arrival of phocoenids in the western North Atlantic and that the Goose Creek Limestone dredged offshore Folly Beach (South Carolina) is perhaps slightly younger in geochronologic age. Evidence supporting this is the occurrence of the delphinid cf. Astadelphis at Folly Beach, unknown from the Yorktown Formation but common in upper Pliocene strata in Italy, and the occurrence of upper Pliocene bivalves such as Ostrea coxi, thus far reported only from the upper Pliocene Tamiami Formation of Florida (Gardner, Reference Gardner1945). The rarity and low diversity of phocoenids in the North Atlantic upper Miocene and Pliocene contrast strongly with the western and eastern North Pacific, their likely center of origin (Barnes, Reference Barnes1984, Reference Barnes1985; Ichishima and Kimura, Reference Ichishima and Kimura2000, Reference Ichishima and Kimura2005, Reference Ichishima and Kimura2009; Murakami et al., Reference Murakami, Shimada, Hikida and Hirano2012a, Reference Murakami, Shimada, Hikida and Hiranob; Boessenecker, Reference Boessenecker2013; Racicot et al., Reference Racicot, Deméré, Beatty and Boessenecker2014) and suggest limited and geologically recent dispersal to the North Atlantic (e.g., Colpaert et al., Reference Colpaert, Bosselaers and Lambert2015; Fajardo-Mellor et al., Reference Fajardo-Mellor, Berta, Brownell, Boy and Goodall2006; Lambert, Reference Lambert2008). If from the Goose Creek Limestone, a dispersal near the early–late Pliocene boundary is possible. While derivation from the upper Pleistocene Wando Formation is unlikely (see above), it is possible that these specimens are from a separate as-yet unrecognized Pleistocene deposit; however, no evidence supporting this exists.

Hearing adaptations

Specimen CCNHM 1913 shares many features of the bony labyrinth that indicate NBHF hearing ability (e.g., Galatius et al., Reference Galatius, Olsen, Steeman, Racicot, Bradshaw, Kyhn and Miller2019; Racicot et al., Reference Racicot, Mourlam, Ekdale, Glass, Marino and Uhen2024). The secondary bony lamina is 95.78% the size of the cochlear length. It lies above the top end of the typical range for extant odontocetes (71–92%) (Churchill et al., Reference Churchill, Martinez-Caceres, de Muizon, Mnieckowski and Geisler2016). A high ratio of cochlear length and secondary bony lamina length is a clear indicator for ultra-high-frequency hearing, or ultrasonic hearing (hearing ranges from tens of kHz up to 170 kHz; e.g., Churchill et al., Reference Churchill, Martinez-Caceres, de Muizon, Mnieckowski and Geisler2016). This feature is found in all extant odontocetes (Ketten, Reference Ketten, Webster, Fay and Popper1992; Churchill et al., Reference Churchill, Martinez-Caceres, de Muizon, Mnieckowski and Geisler2016). Another evidence for ultrasonic hearing is a high cochlear aspect ratio (above 0.55; see Gray, Reference Gray1907, Reference Gray1908; Ekdale, Reference Ekdale2010; Racicot et al., Reference Racicot, Gearty, Kohno and Flynn2016), which is nearly achieved by the value of 0.54 observed in specimen CCNHM1913 (Ketten and Wartzok, Reference Ketten, Wartzok, Thomas and Kastlein1990; Churchill et al., Reference Churchill, Martinez-Caceres, de Muizon, Mnieckowski and Geisler2016). The highest-frequency sounds are detected at the cochlear base. Since the width of the cochlea, including the base, affects the aspect ratio, the latter can be correlated with the ability of high-frequency hearing (Churchill et al., Reference Churchill, Martinez-Caceres, de Muizon, Mnieckowski and Geisler2016). Following West (Reference West1985) and Racicot et al. (Reference Racicot, Gearty, Kohno and Flynn2016), the product of cochlear length and number of turns, which characterizes the tightness of the cochlea coiling, is negatively correlated with the hearing frequency range (i.e., lower values mean a higher frequency threshold). Since specimen CCNHM 1913 shows the lowest cochlear turn value compared with other phocoenids (Racicot et al., Reference Racicot, Gearty, Kohno and Flynn2016), this strongly indicates that it could potentially hear high frequencies. Altogether, this evidence further supports the positioning of CCNHM 1913 within the morphospace of other odontocetes known for ultra-high-frequency hearing, and particularly NBHF.

Locomotory adaptations

A suitable metric to infer the agility of aquatic mammals, especially of extinct species, is 90var (Malinzak et al., Reference Malinzak, Kay and Hullar2012; Berlin et al., Reference Berlin, Kirk and Rowe2013; Ekdale and Racicot, Reference Ekdale and Racicot2015; Racicot et al., Reference Racicot, Gearty, Kohno and Flynn2016, Reference Racicot, Darroch and Kohno2018). This reference value is negatively correlated with rotational movement sensitivity of the head, thus smaller 90var values mean higher sensitivity to head movements, which are associated with faster-moving animals (Berlin et al., Reference Berlin, Kirk and Rowe2013; Racicot et al., Reference Racicot, Darroch and Kohno2018). With a 90var value of 10.51, specimen CCNHM 1913 is situated close to various extinct and extant phocoenid specimens, for example, Semirostrum ceruttii, Haborophocoena toyoshimai, Phocoena phocoena, Phocoena sinus, and Phocoenoides dalli (Racicot et al., Reference Racicot, Darroch and Kohno2018). According to Racicot et al. (Reference Racicot, Gearty, Kohno and Flynn2016, Reference Racicot, Darroch and Kohno2018), this may be an indicator for a coastal lifestyle since recent phocoenid species with higher 90var values show coastal habitat preferences.

Conclusions

We describe the first fossil occurrence of true porpoises (Phocoenidae) from the western North Atlantic, likely derived from the Pliocene Goose Creek Limestone of coastal South Carolina. Our analyses suggest that the specimens described are very similar to Phocoena phocoena. We assign the four ?Pliocene specimens to Phocoena sp. as species-level identification would require a comprehensive comparative study, including intraspecific variation, of the ear anatomy across all phocoenids (extant and fossil), which is beyond the scope of this study. The morphometric analyses of the secondary bony lamina length and cochlear length ratio, the aspect ratio, and the tightness of cochlear coiling indicate the ability to hear NBHF signals like other phocoenids. The PCA confirms this in the position of specimen CCNHM 1913 within the NBHF sound production and ultrasonic hearing morphospace. The specimens reported herein are most plausibly Pliocene in age; thus, they may support a pre-Pleistocene trans-Arctic dispersal of Phocoena to the North Atlantic. We predict that fossils of Phocoena spp. may be found in correlative strata of the North Sea (e.g., Lillo Formation) or possibly Italy, which also contains richly fossiliferous Pliocene and Pleistocene odontocete assemblages.

Acknowledgments

We thank the collectors, T. Burlison, R. Jackson, D. Pendergrast, and A. Wallace, for donating the specimens studied in this paper to CCNHM. We further thank A.W. Gale for encouraging and facilitating these donations. Thanks to S.J. Boessenecker (formerly CCNHM) for access to specimens under her care. R.A.R. acknowledges support from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, which is sponsored by the Federal Ministry for Education and Research (Germany), during earlier stages of the project. We gratefully acknowledge reviews from T. Kimura and O. Lambert that greatly improved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Data availability statement

Data (3D models and μCT scan) are available from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.fttdz0967.

Appendix 1. Detailed listing of all measurements, referring to the periotic, cochlea, and semicircular canals of specimen CCHNM 1913

Appendix 2. Listing of all species abbreviations indicated in the PCA analysis