Introduction

Malaysia stands out as a notable case in discussions of democratization. As democratic backsliding garners increasing attention in political science, this Southeast Asian country has made notable strides in democratic development, despite its half-century history as a textbook case of electoral authoritarianism and the persistent influence of ethnicity based identity politics (Ostwald and Oliver Reference Ostwald and Oliver2020). According to the V-Dem Electoral Democracy Index, Malaysia’s scored jumped from 0.34 to 0.47 between 2017 and 2019, and then further rose to 0.52 in 2024 (on a 0 to 1 scale).

Despite this striking progress, Malaysia was long regarded as an unlikely case for democratization, given that the long-standing ruling coalition, Barisan Nasional (the National Front, BN), not only controlled key state resources and maintained an extensive patronage network, but also exercised significant influence over the administration of national elections. As a result, the outcome of the fourteenth general election (GE14) in 2018 came as a surprise to many. Even the then-current Prime Minister Mahathir publicly admitted that the main opposition coalition at the time, Pakatan Harapan (the Hope Alliance, PH), “did not expect to win the general election.”Footnote 1 This unexpected victory prompted political scientists to investigate its underlying causes. One immediate explanation was the emergence of a multi-ethnic, urban-centered voter bloc distinct from rural voters. This view gained traction as many observed that PH tended to secure higher vote shares in urban, or more precisely, population-dense, electoral districts. However, despite widespread electoral evidence supporting this pattern, survey data continued to suggest that urban and rural voters were, in fact, quite similar in their voting behavior once ethnic background was controlled for.

Although this article acknowledges that both perspectives offer valuable insights, I argue that both aggregated election data and survey data ultimately point in the same direction: the urban–rural divide may not be as pronounced as commonly assumed. This is not to suggest that urban–rural differences are unrelated to party vote share. However, this empirical difference tends to reflect differences in party performance across states with markedly different levels of urbanization, rather than capturing local dynamics or differences in underlying voter preferences. For example, while Kuala Lumpur is clearly distinct from semi-urban and rural areas in Kelantan, a city like Kota Bharu (i.e., the capital of Kelantan) has more in common with its surrounding rural districts than one might at first assume. At the same time, some of the observed variation between urban and rural districts within the same state can be attributed to the inclusion of suburban areas within electoral boundaries that are formally classified as urban, due to their proximity to neighboring urban centers. This boundary design may exaggerate the perceived urban–rural divide. Thus, at the aggregated level, once we control uneven population density across states and within electoral districts, there is little evidence to support a meaningful association between the urban–rural divide and party vote share differences. At the individual level, consistent voting patterns across ethnic groups underscore the enduring influence of ethnic cleavages in Peninsular Malaysia.Footnote 2

Let’s begin by taking a step back to address a fundamental question: why does the debate over the urban–rural divide in Malaysia persist? The disagreement in the existing literature remains unresolved because neither of the two camps has adequately addressed the concerns raised by the other. Scholars who rely on survey data argue that the apparent discrepancies between individual-level findings and aggregated election results stem from the problem of ecological fallacy, that is, we cannot infer individual behavior based on group-level data. This is indeed a serious methodological concern. However, I also understand why this conclusion remains unconvincing to many scholars of Malaysian politics. Historically, there has been a lack of high-quality survey data on Malaysian voters’ behavior. In contrast, while aggregated election data is methodologically less desirable, it is far more accessible. Although new survey data, such as the dataset I use in this article, has recently become available, we cannot retroactively collect data on historical voting behavior. In short, it is understandably difficult to persuade scholars of Malaysian politics to abandon aggregated election data, which is sometimes the only reliable data source for examining the country’s electoral landscape.

The debate was also heated because both sides have made some broad claims that go beyond what their empirical evidence and research design can substantiate. For instance, proponents of the urban–rural divide position have asserted that Malaysia’s urban–rural divide confirms modernization theory, claiming that the urban–rural cleavage supersedes traditional ethnic boundaries (Ng et al. Reference Ng, Rangel and Chin2021a; Slater Reference Slater2018), while survey-based studies sometimes dismiss the relevance of aggregated election data without rigorously assessing the reliability and validity of their own data.

In this article, therefore, I hope to identify the cause of the discrepancy between individual-level survey results on voting behavior and aggregated election data in the most consequential election in Malaysian history. I argue that the spatially heterogeneous effect of urban–rural differences explains the empirical discrepancy we observe. While it is true that, at a general methodological level, political methodologists have yet to reach a consensus on how to infer individual behavior from group-level data, I argue that, given our contextual understanding of Malaysia, it is still possible to investigate the origins of this discrepancy. After all, aggregated election results are ultimately composed of individual voting behaviors. Therefore, this article seeks to decompose and reconcile the differences between aggregated outcomes and survey findings.

To facilitate a better understanding of this question, this article conducts a detailed analysis of both aggregated election data and survey data. Notably, following the 2018 election, the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) published, for the first time, detailed demographic information for each electoral district, both at the federal parliamentary level and the state legislative level (Dewan Undangan Negeri, DUN), based on the 2018 electoral boundaries (Department of Statistics Malaysia 2022). Additionally, the Asian Barometer Survey conducted by National Taiwan University (NTU) (Asian Barometer Survey Reference Survey2023) included, for the first time, a question explicitly asking respondents about their voting behavior in the last election (GE14 under this context). The increased data transparency following BN’s electoral defeat enables a more comprehensive examination of claims raised by both sides of the debate.

This article proceeds as follows. First, I provide a detailed literature review that traces the evolution of the debate, highlighting the concerns each side has raised against the other, as well as the under-examined issues within their own designs. Second, I examine how aggregated election data has been analyzed and discuss proposed designs that aim to address two major concerns: within-district and across-state heterogeneity in urbanization levels. I propose methodological responses to these concerns by hierarchical modeling and integrating federal- and state-level election data in a matching design to analytically estimate how differences manifest across electoral districts. Third, to validate the survey data, I aggregate responses from individuals based on the demographic characteristics of electoral districts and simulate election outcomes. By comparing these simulations to actual results, I demonstrate that the survey data offers an accurate representation of voter behavior. Through this approach, I aim to contribute fresh perspectives that enhance our understanding of Malaysian politics.

The big debate in Malaysia

The evolving history of this debate

For quite a long time, discussions over the urban–rural divide have persisted in the Malaysian politics literature. The twelfth General Election (GE12) marked the beginning of this debate. Many aspects of Malaysian politics underwent substantial change following this landmark election. Prior to 2008, electoral politics in Malaysia were believed to be largely divided along Malay/non-Malay ethnic lines. Urbanization and the rise of the Malay middle class seemed to have little, if any, effect on reducing the political divisions between Malays and non-Malays in Peninsular Malaysia (Pepinsky Reference Pepinsky2007). Despite facing several electoral setbacks, BN, the multi-ethnic electoral authoritarian coalition led by the Malay nationalist party United Malays National Organization (UMNO), consistently secured a two-thirds majority in the federal parliament until 2008. In GE12, however, BN not only failed to achieve the two-thirds super-majority required to amend the constitution, winning just 63 percent of the seats, but also received only slightly more than half of the popular vote.

Reflecting on this election, many politicians and analysts observed that Malaysian Chinese voters appeared to have significantly shifted away from the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) and Parti Gerakan Rakyat Malaysia (Malaysian People’s Movement Party, GERAKAN), the two major Chinese ethnic parties within BN at that time, in favor of expressing strong support for the opposition, particularly the Chinese-dominant Democratic Action Party (DAP) and the Malay-based, multi-ethnic Parti Keadilan Rakyat (People’s Justice Party, PKR). Together with the long-standing Malay opposition party, Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (Malaysian Islamic Party, PAS), and the defection of Indian voters from BN, the shift of Chinese voters was widely interpreted as creating a political phenomenon dubbed the Tsunami Cina (Chinese Tsunami) in Malaysian politics (Pepinsky Reference Pepinsky2009).

BN’s declining electoral support continued five years later in the thirteenth General Election (GE13), when it failed to secure the popular vote. Prime Minister Najib Razak attributed this outcome to a continued defection of Chinese voters. However, many analysts objected, noting that the Chinese electorate alone was not large enough to account for such a significant swing. Instead, the results were interpreted as evidence of a broader, multi-ethnic urban coalition turning away from BN, a shift described as the Urban Tsunami (Palatino Reference Palatino2013).

If anything fueled this narrative, it was the opposition’s strong performance in highly urbanized states such as Selangor and Penang. As a result, many scholars began to explore the assumption that a new cluster of urban voters was emerging.

Notably, Ng et al. (Reference Ng, Rangel, Vaithilingam and Pillay2015) argued that in GE13, BN relied heavily on rural voters, regardless of ethnic background, suggesting the emergence of a significant urban–rural divide that even overshadowed Malaysia’s long-standing ethnic cleavages. This claim was challenged by Pepinsky (Reference Pepinsky2015), whose article appeared in the same issue of the Journal of East Asian Studies. Citing several measurement and research design issues in Ng et al. (Reference Ng, Rangel, Vaithilingam and Pillay2015), Pepinsky (Reference Pepinsky2015) contended that both urban–rural and ethnic cleavages persisted in Malaysian politics, and that these two dimensions operated independently rather than interactively. To be precise, Pepinsky (Reference Pepinsky2015) suggested that there was no evidence that two electoral districts with the same ethnic composition and different urban levels would manifest different electoral outcomes.

As Malaysian politics moved toward GE14 in 2018, the debate over whether BN’s declining support stemmed primarily from a multi-ethnic urban coalition continued. Ng and his co-authors appeared to take Pepinsky’s critique seriously. They refined their research design and measurement approaches, employing both linear and logistic regression models on aggregated election data. Their findings ultimately aligned with those of Pepinsky (Reference Pepinsky2015), concluding that both electoral districts with higher proportions of Malay voters and those that were more urban were associated with lower BN vote shares (Ng et al. Reference Ng, Rangel and Phung2021b). In other words, they argued that urban–rural divides and ethnic cleavages coexisted in Malaysia.

Elvin Ong emerged as one of the most vocal critics of this conclusion, joining others who questioned whether the ethnic cleavage structure had truly shifted, such as Moten (Reference Moten2019). Drawing on his work with individual-level survey data, he rightly pointed out that previous studies, including Pepinsky (Reference Pepinsky2009; Reference Pepinsky2015) and Ng et al. (Reference Ng, Rangel, Vaithilingam and Pillay2015), relied exclusively on aggregated election data, yet sought to draw inferences about individual voting behavior (Gandhi and Ong Reference Gandhi and Ong2019; Ong Reference Ong2020). Based on survey data collected by Ong himself and from the Asian Barometer, he found no evidence that urban and rural voters in Peninsular Malaysia had different political views when controlling for ethnic background. He acknowledged that some Malay voters may indeed have defected from BN but argued that urban Malay voters were not significantly different from their rural counterparts in this regard (Gandhi and Ong Reference Gandhi and Ong2019; Ong Reference Ong2020). He went so far as to dismiss the notion of urban–rural differences as a “hollow concept” in the study of Malaysian politics (Ong Reference Ong2020).

The bigger methodological issues behind the debate

Although Ong (Reference Ong2020) critique was on point in highlighting the problem of drawing inferences about individual electoral behaviors from aggregated data, it still prompted an immediate response from Ng and his co-authors. Employing tree-based machine learning techniques on aggregated election data, Ng et al. (Reference Ng, Rangel and Chin2021a) offered a rebuttal to Ong (Reference Ong2020), arguing that the urban–rural divide was the strongest predictor of voting behaviors in Peninsular Malaysia.

Ng et al. (Reference Ng, Rangel and Chin2021a) reinforces this critique by emphasizing the superiority of tree-based machine learning methods. To be clear, while machine learning tools can identify that urban districts are highly likely to be won by PH, they do not address the core question raised by Ong (Reference Ong2020). To use a metaphor: if a machine learning model detects a high volume of oxygen atoms in a black box, it still cannot determine whether those atoms come from oxygen gas or water. In other words, relying on machine learning does not automatically overcome the key methodological concerns at the heart of the debate, many of which, as I demonstrate in this article, arise from context-specific issues in Peninsular Malaysia.

Other scholars, however, have responded to Ong’s (Reference Ong2020) critique in different ways. For example, Dettman and Pepinsky (Reference Dettman and Pepinsky2024) sidesteps the issue by arguing that the demographic characteristics of electoral districts shape parties’ candidate selection and campaign strategies, thus avoiding direct claims about individual voting behavior. This approach acknowledges the validity of Ong’s (Reference Ong2020) concerns while showing that aggregated data can still yield meaningful insights, depending on the type of inference being made. Nevertheless, Dettman and Pepinsky (Reference Dettman and Pepinsky2024) maintains that urban–rural cleavages exist in Malaysia. What the study does not address, however, is the source of the discrepancy between aggregated analyses and survey-based findings: at which point in the process does the aggregation break down?

The gravity of this debate

Why is this debate important, and why does it remain relevant? Despite ongoing disagreements in the study of Malaysian politics, these empirical debates exert a subtle yet powerful influence on the direction of subsequent research. Increasingly, scholars align themselves with particular narratives, often without replicating the analyses they cite. Once a narrative becomes established, it can shape the trajectory of knowledge production, reinforcing itself over time and marginalizing alternative perspectives. More significantly, the debate has exposed recurring methodological misunderstandings, particularly among comparative political scientists studying electoral politics. As demonstrated in this section, many issues stem from insufficient attention to the ecological fallacy, improper model specification, and misinterpretations of empirical data.

Perhaps more importantly, these academic conclusions have, in some cases, directly influenced political parties’ campaign strategies and produced tangible real-world consequences. For example, prior to GE14, UMNO and Najib took deliberate steps to amplify the division between PAS and its former allies in PH by allowing PAS to introduce the Syariah Courts (Criminal Jurisdiction) Act 1965 (Amendment) Bill (widely known as Rang Undang Undang 355 or RUU355), apparently aiming to attract Malay voters in semi-urban constituencies, such as many districts in Selangor, away from PH (Ting Reference Ting2017). Advisors to PH also drew on such studies when formulating campaign strategies, particularly with regard to seat allocation. For instance, Saiful (Reference Saiful2018) suggested that Parti Peribumi Bersatu Malaysia (Malaysian United Indigenous Party, Bersatu) should play a greater role in semi-urban districts with a mix of Malay and other ethnic voters, and the party eventually did get more seat allocations in the semi-urban districts of Johor. In the most recent fifteenth general election (GE15), Anwar Ibrahim moved his constituency from Port Dickson in Negeri Sembilan to Tambun in Perak, a suburban electoral district near Ipoh, to boost PH’s support, apparently convinced that that suburban voters were primed to support the opposition. The fact that a major prime ministerial candidate chose to contest a semi-urban seat highlights the strategic importance of the urban–rural divide in Malaysian elections. As Ong (Reference Ong2020) observed, these studies may have shaped how political elites perceived their own strategic positions.

Moreover, if the urban–rural cleavage had remained as prominent since GE12 as many argued, the rise of Perikatan Nasional (the National Alliance, PN), a Malay-dominant coalition with a few nominally multiethnic partners (such as GERAKAN which could not secure any seats anymore), would seem puzzling, if not implausible. Yet, PN successfully mobilized Malay support across both urban and rural areas. These developments underscore the need for greater conceptual and empirical clarity.

Spatial heterogeneity: One hypothesis

Returning to the central question: how does the aggregation of electoral data produce what may be a misleading inference of pronounced urban–rural differences? Ong (Reference Ong2020) offered a potential solution for unpacking this issue, arguing that the spatial heterogeneity of urban–rural divisions play a crucial role. In Malaysia, there are at least two forms of spatial heterogeneity: inter-state and intra-state variation. To be fair, most studies of Malaysian politics have recognized the considerable differences in electoral outcomes across the states and federal territories (Wilayah Persekutuan) of Peninsular Malaysia (Pepinsky Reference Pepinsky2015; Ostwald and Oliver Reference Ostwald and Oliver2020; Ng et al. Reference Ng, Rangel and Chin2021a; Dettman and Pepinsky Reference Dettman and Pepinsky2024), which represent the first type of heterogeneity. However, these studies typically treat states as categorical variables, without formally estimating how the relationship between population density and party vote share varies between different states.

Treating states as a categorical variable allows researchers to estimate the average vote share that a party or coalition receives in each state, while controlling factors such as population density, the usual proxy to measure urban–rural differences, and ethnic composition. This approach is reasonable, as it reveals the baseline level of support that each party or coalition garners in each state. However, it does not capture the heterogeneous effects of population density within different states and federal territories. To elaborate, if we assume that the relationship between population density and party vote share is constant across states and federal territories, and only the baselines (regression intercepts) vary, this method may be sufficient. Yet, it fails to account for the substantial variation in urbanization both across and within electoral districts and states. As a result, this oversight risks misattributing certain aspects of spatial heterogeneity to the effect of population density.

To address this, I propose using linear mixed effects model (or hierarchical linear model) that allows the slopes and intercepts of model estimates to vary across states. This approach captures the differential impact of population density on vote share in a more nuanced and statistically rigorous way.

Meanwhile, Ong’s (Reference Ong2020) other critique is more challenging, as it questions whether the effect of population density persists in the presence of high intra-district heterogeneity. Many studies have rightly pointed out that the electoral committee under BN often incorporated densely populated urban areas with less densely populated suburban ones in order to manipulate voter representation (Case Reference Case and Gomez2004; Ostwald Reference Ostwald2013; Ong Reference Ong2020).

Although this question is difficult to answer without access to polling-station-level data, I employ a strategy that links DUN election results to federal parliamentary outcomes. In Peninsular Malaysia, each federal constituency, excluding those in federal territories such as Kuala Lumpur, which lack state-level legislative bodies, typically comprises several state legislative districts. Assuming that voters in this region generally do not engage in ticket-splitting,Footnote 3 this approach enables me to examine whether population density is strongly associated with party vote share across multiple small units within larger federal districts. Specifically, it allows me to account for the degree of heterogeneity within each federal constituency.

Building on both Gandhi and Ong (Reference Gandhi and Ong2019) and Ong (Reference Ong2020), I take an additional step to demonstrate the value of survey data. Specifically, I demonstrate that we can use individual-level data not only to make inferences about voting behavior but also to validate those inferences against aggregated electoral outcomes. After all, aggregated election data, as its name suggests, should be an aggregation of individual behaviors. The conclusion that urban and rural voters of the same ethnic background tend to vote similarly, drawn from individual-level survey data, can, in fact, be shown to align with patterns observed the aggregate level using election data.

To do so, I aggregate individual voting preferences derived from survey data to simulate estimated electoral outcomes, which I then compare with actual election results. The close correspondence between the simulated and observed results suggests that survey data we have for Malaysia indeed provide a reliable prediction of electoral outcomes, thereby offering a degree of validation for conclusions drawn from individual-level analysis.

Data and variables

As discussed in the previous sections, I combine three distinct datasets related to GE14 for my analysis.Footnote 4 First, the election results at both the federal and state levels are fundamental to my research. These results are publicly accessible through The Star (2018). Second, I utilize data on the demographic composition of federal- and state-level electoral districts. Prior to GE14, researchers of Malaysian politics had limited access to detailed demographic data, which compelled many studies to rely on proxies such as log transformations of district areas (Pepinsky Reference Pepinsky2015) and voter density (Ostwald Reference Ostwald2013), as they only had access to voter figures rather than actual population counts. However, Department of Statistics Malaysia (2022) made these detailed data available following GE14 as part of an effort to enhance data transparency. Third, after GE14, in collaboration with Malaysia’s largest political polling company, Merdeka, the Asian Barometer by NTU included a survey question that asked respondents about their voting choices in the past general election, for the first time in Malaysian history. This survey also recorded respondents’ ethnic backgrounds, regions of residence, and urban–rural classifications (Asian Barometer Survey Reference Survey2023).

As previous studies have primarily examined the role of ethnicity and the urban–rural divide in shaping electoral outcomes in Peninsular Malaysia, this article focuses specifically on five variables, as summarized in Table 1. The outcome variable is the performance of political parties in GE14. In the aggregated data, this is measured by party voting share in each electoral district, while in the survey data, it is represented by voters’ recalled voting behavior.

Table 1. Summary of variables and measurements across datasets

BN serves as a useful test case for the theory, as the decisive nature of the election meant that voters were essentially choosing for or against BN, the long-standing electoral authoritarian coalition. A potential concern about using BN as a measure is that, although BN is dominated by UMNO, it also includes parties representing other ethnic groups. If we hypothesize that Malay voters predominantly preferred BN, does this preference hold when it is another BN component party, such as the MCA, contesting in certain districts?

I recognize the validity of this concern, but I believe it would be even more problematic to focus solely on districts where UMNO contested. First, Malaysia has a long history of multiethnic political coalitions, and it is common for voters to make choices based on coalitions rather than individual parties. In GE14 specifically, all major coalitions, BN, PH, and Gagasan Sejahtera (Ideas of Prosperity, GS), competed as unified political entities. Arbitrarily breaking the dataset into units based on member parties of each coalition would introduce unnecessary confusion.

Second, while it is true that UMNO often refrained from contesting in districts with predominantly ethnic minority populations, Malay voters in these districts frequently chose between BN member parties representing ethnic minorities and candidates from other coalitions, who are also often minority candidates. Based on these considerations, I contend that it is more appropriate to use political coalitions as the unit of analysis, rather than individual member parties.

The two explanatory variables, ethnicity and the urban–rural divide, are central to major theoretical frameworks in the field. Ethnicity is typically measured by the proportion of ethnic groups (commonly categorized as Malay/Non-Malay) within each electoral district in the aggregated data, and by respondents’ self-reported ethnic backgrounds in the survey data. The urban–rural divide is assessed using population density in the aggregated data and urban–rural classifications provided in the survey datasets, which are also coded by population density.

The challenge of categorizing electoral districts as “urban” or “rural” lies at the core of this discussion. As Nemerever and Rogers (Reference Nemerever and Rogers2021) argue, while total population or population density is often regarded as the gold standard for measuring the urban–rural divide, this approach raises important concerns: are “rural” areas near San Diego truly comparable to “rural” areas in Montana, even if they exhibit similar population densities? Although this question is metaphorical, the contrast between Malaysia’s East Coast and the suburb of Kuala Lumpur is equally significant. As the urban–rural divide has gained prominence globally, particularly in the United States, scholars have increasingly highlighted the limitations of such binary classifications.

I refrain from addressing this issue in greater detail here primarily because doing so would complicate the analysis, although I do elaborate on my thoughts in the Appendix (section A). I aim to remain consistent with prior studies by employing the same set of variables, ensuring comparability across research. While this article is not the appropriate venue for an in-depth exploration of this issue, my proposal to localize the measurement of the relationship between population density and party vote share constitutes is, I believe, a constructive step toward better measuring it.

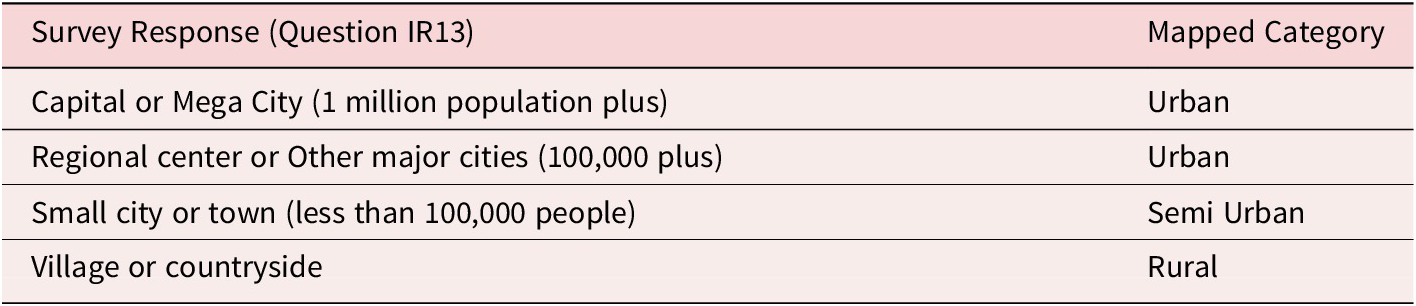

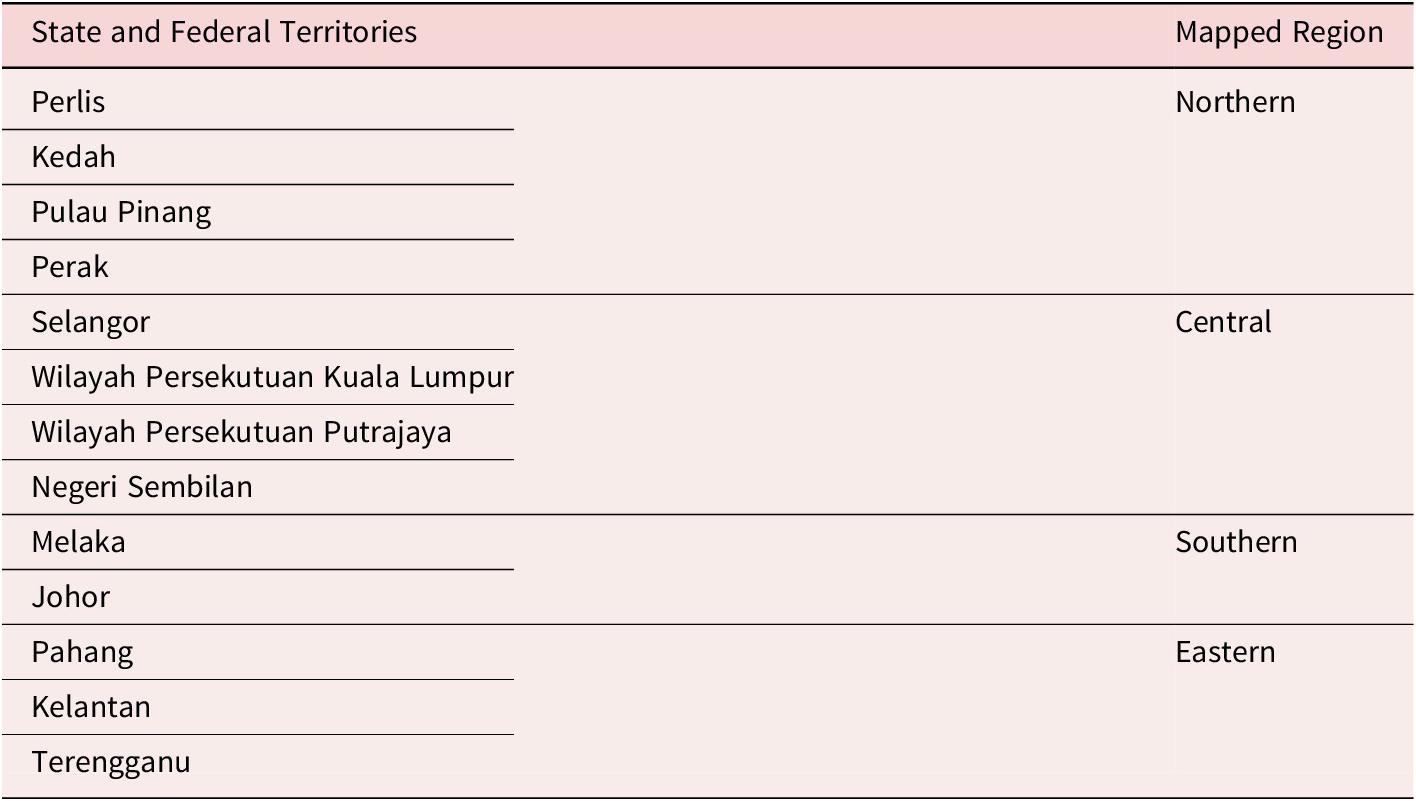

I must also contend with the fact that the survey data only provide four categorical classifications when it comes to urban and rural areas. For the electoral district (whose boundaries are unfortunately not aligned with administrative boundaries), Tindak Malaysia (2023) offers a classification of electoral districts into three urban tiers by Global Human Settlement Layer (GHSL) from the European Commission Joint Research Centre (2024) onto electoral boundaries and using electorate figures to estimate the predominant urban classification of each constituency.Footnote 5 I further harmonized their classification system with the urban–rural classifications provided in the Asian Barometer Survey (Reference Survey2023), shown in Table 2. Additionally, since the Asian Barometer Survey (Reference Survey2023) does not specify the state of residence for respondents and instead categorizes them by region within Peninsular Malaysia, I matched the state-level data in the aggregated dataset to the regional categories in the Asian Barometer dataset, shown in Table 3.Footnote 6

Table 2. Urban–rural classification mapping from survey responses

Table 3. Mapping of Malaysian states to regions (Peninsular Malaysia only)

Analysis of aggregated election data

Addressing the inter-state heterogeneity

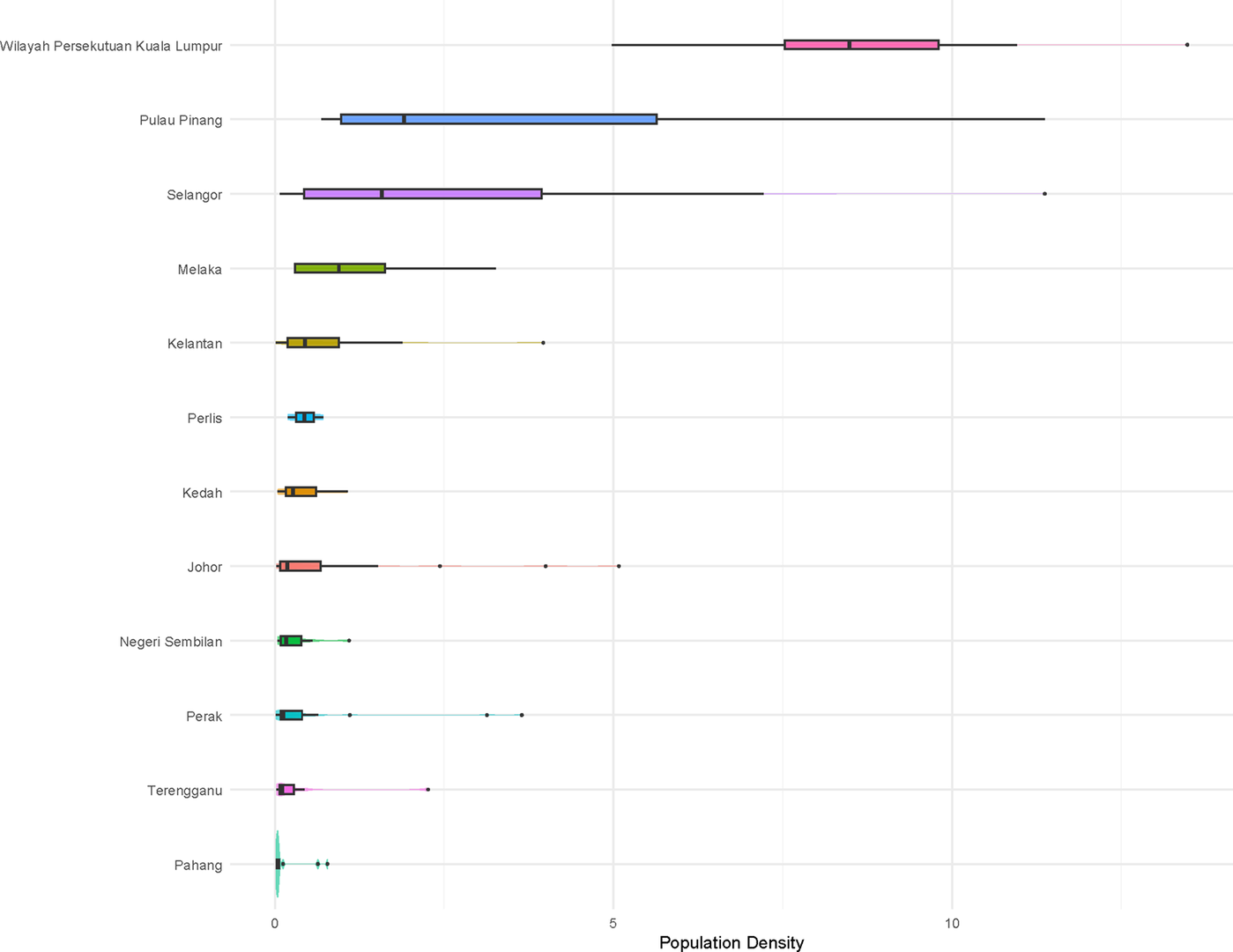

As I have previously noted, there is considerable heterogeneity in levels of urbanization across Malaysia, particularly when population density is used as a proxy. An examination of population density across electoral districts (see Figure 1) reveals that certain states, notably Penang, Selangor, Johor, and Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur, are significantly more densely populated than others. This substantial variation underscores the importance of addressing urban–rural differences in any serious analysis of Malaysian electoral dynamics.

Figure 1. Population density across federal parliamentary districts.

Why does inter-state heterogeneity matter? If spatial variation is not sufficiently apparent on the map, we can further decompose the data to illustrate the substantial variation in population density across states. Figure 2 clearly shows a highly skewed distribution of densely populated districts. Aside from a few exceptions, such as Kuala Terengganu, most of these districts are concentrated along the West Coast. If the analyses by Ostwald and Oliver (Reference Ostwald and Oliver2020) and Dettman and Pepinsky (Reference Dettman and Pepinsky2024) are correct in asserting a strong state-level effect in Peninsular Malaysia’s electoral politics, then a critical question arises: Are we truly estimating the relationship between population density and vote share, or are we mistakenly attributing state effects to population density, or vice versa?

Figure 2. Distribution of population density across states.

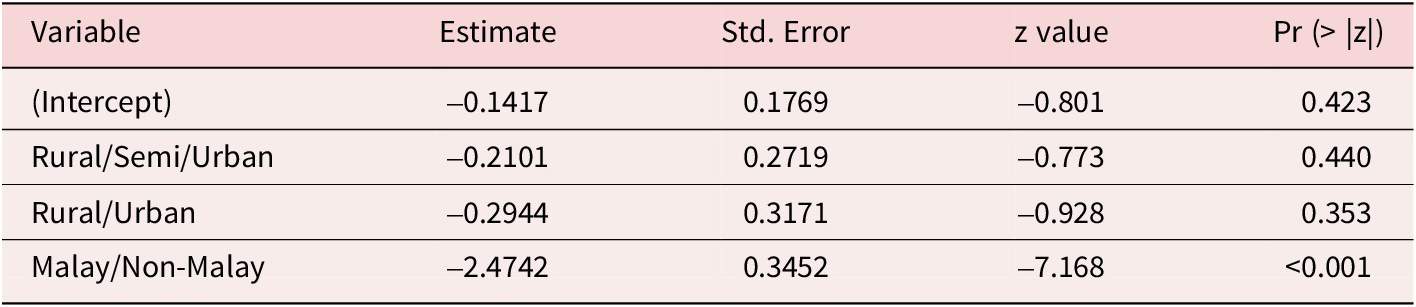

Accordingly, I should allow the coefficient on population density to vary across states and federal territories. Although the raw population-density values within each jurisdiction are approximately Gaussian, pooling them causes certain states to exert disproportionate influence on the estimates. I further elaborate on this point in the Appendix.

Previous research has commonly included state as a variable in regression models. However, this approach merely estimates the average vote share of political coalitions across different regions of Peninsular Malaysia while controlling for population density and ethnic composition. Such a design does not account for the possibility that the relationship between population density and vote share may vary by state.Footnote 7 While state dummies mitigate the broader issue, they do not inherently resolve the influence of extreme observations within states. Highly dense urban districts like Jelutong or Lembah Pantai may still disproportionately influence the estimates. A mixed effects model addresses this limitation by allowing both the intercepts and the slopes for population density to vary across states. In this article, I model the vote share of BN as the outcome variable, with Malay Share and Population Density as the explanatory variables. I estimate a linear mixed-effects model with a random slope on population density by state, and further estimate standard errors using bootstrap to further mitigate the heterogeneity issue:

Where:

-

• i indexes state legislative districts (DUNs)

-

• j indexes states

-

•

$ {\beta}_0 $

is the fixed intercept (shared across all states)

$ {\beta}_0 $

is the fixed intercept (shared across all states) -

•

$ {\beta}_1 $

is the fixed effect of Malay ethnic share

$ {\beta}_1 $

is the fixed effect of Malay ethnic share -

•

$ {\beta}_2 $

is the average fixed effect of population density

$ {\beta}_2 $

is the average fixed effect of population density -

•

$ {\mu}_{0j}\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{\mu_{0j}}^2\right) $

is the random intercept specific to state j

$ {\mu}_{0j}\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{\mu_{0j}}^2\right) $

is the random intercept specific to state j -

•

$ {\mu}_{1j}\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{\mu_{1j}}^2\right) $

is the random deviation in the effect of population density for state j

$ {\mu}_{1j}\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{\mu_{1j}}^2\right) $

is the random deviation in the effect of population density for state j -

•

$ {\varepsilon}_{1j}\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{\varepsilon}^2\right) $

is the residual district-level error

$ {\varepsilon}_{1j}\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{\varepsilon}^2\right) $

is the residual district-level error

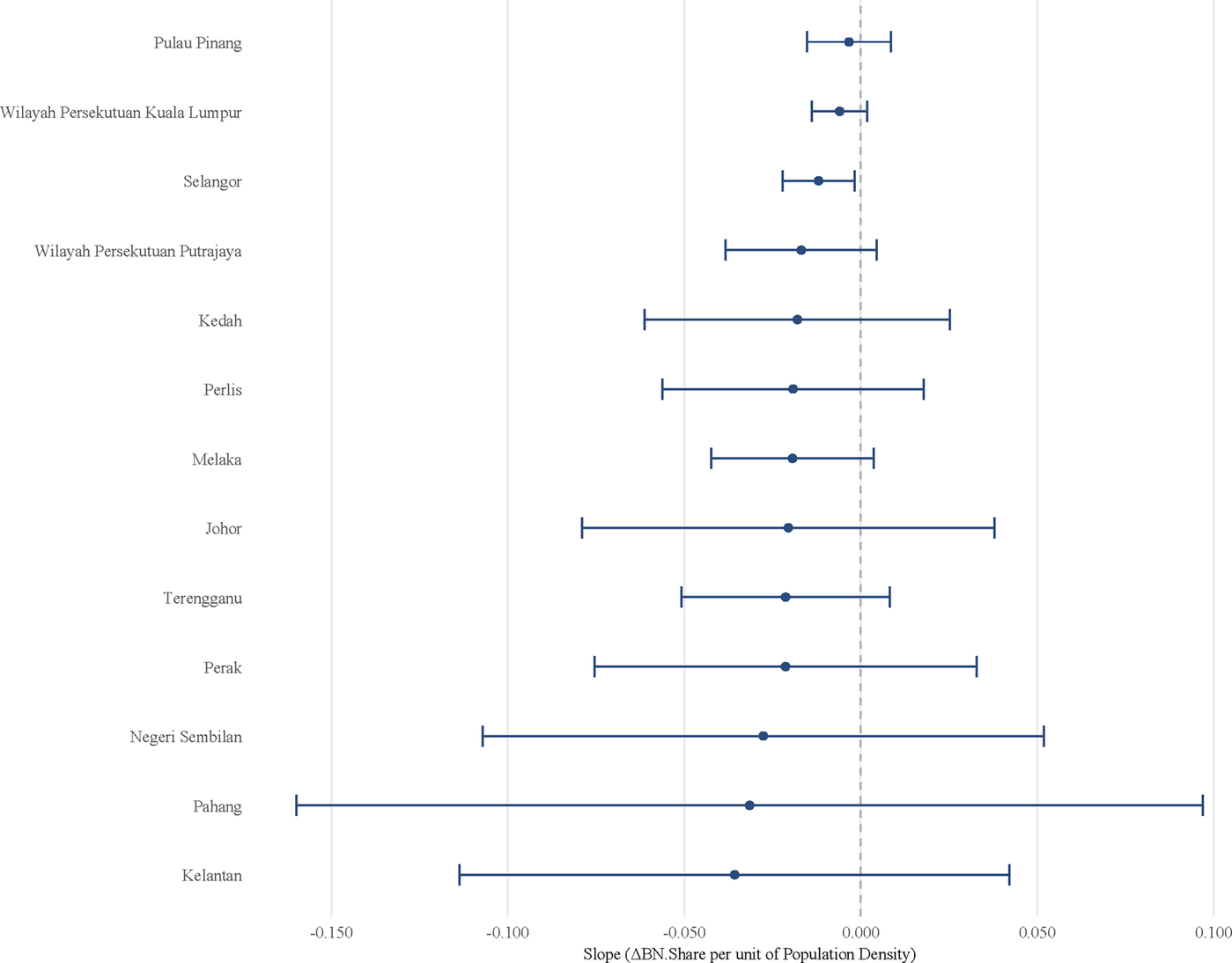

As shown in Figure 3 (see Table A3, for the output table), there is considerable heterogeneity in the effect of population density on political coalitions’ vote shares across states and federal territories. Notably, the estimated effect of population density tends to decline as the overall level of urbanization increases from one state to another. However, as indicated by the bootstrapped confidence intervals, there is no statistically significant association between population density and party vote share once the model allows these effects to vary explicitly across states and federal territories.

Figure 3. Associations between population density and party share by state.

The results from both the baseline model and the hierarchical linear model support my hypothesis that the baseline model primarily captured variation in levels of urbanization across states and federal territories. Once inter-state heterogeneity is explicitly controlled for, there is little substantive evidence to support a strong association between party vote shares and population density at a more localized level.

Intersecting Intra-Electoral-District Spatial Heterogeneity

Incorporating intra-electoral-district heterogeneity significantly complicates the analysis of elections, particularly when relying on aggregated data. However, the institutional and electoral context of Malaysia in 2018 offers a unique opportunity to address this challenge. In that year, federal-level parliamentary elections and state-level legislative elections were held concurrently, ensuring that both levels of government were subject to similar political and economic conditions. This simultaneity enables a more consistent analysis of electoral behavior across different tiers of governance. Each federal electoral district in Malaysia is subdivided into multiple state-level districts (see Figure 4). Leveraging this structure, I examine state-level election results nested within federal electoral boundaries to evaluate how local demographic characteristics, particularly ethnic composition and urbanization, relate to voting patterns. I focus specifically on the performance of the BN coalition. The aggregated election data used in this analysis are drawn from The Star (2018) and Department of Statistics Malaysia (2022), which provide comprehensive documentation of election results and socioeconomic characteristics for each district. This nested design allows for within-federal-district comparisons, enabling the analysis to account for local heterogeneity while controlling broader regional disparities.

Figure 4. Federal and state electoral district boundaries.

How much intra-district heterogeneity can be observed with this design? Figure 5 illustrates this variation, where higher population density differences indicate that DUNs (state-level districts) have a denser population than their corresponding parliamentary constituencies, and vice versa for negative scores. As Ong (Reference Ong2020) rightly pointed out, the substantial spatial heterogeneity within each district has been largely overlooked in previous research.

Figure 5. Population density difference.

In this design, I slightly transformed the variables to capture within-federal-district deviations between state (DUN) and federal-level indicators. Specifically, I computed the difference between the state-level and federal-level values for several key variables: the ethnic composition (Malay share), political support (BN vote shares), and population density. Formally, for each state district i nested within federal district j, I defined the following difference metrics:

These difference variables capture the local (intra-federal-district) deviations from the federal-level district, thereby normalizing each state district’s characteristics relative to its local context. By focusing on these deviations, the analysis emphasizes fine-grained, local heterogeneity that is otherwise obscured in aggregate measures. This approach helps to isolate the micro-level dynamics of electoral behavior from broader, macro-regional trends and facilitates more precise inferences about localized political and demographic effects.

To examine how localized variation in demographic factors explains deviations in political support for BN, I once again estimated a linear mixed-effects model. Formally, the model is specified as follows:

$$ BN\;{Share\ Diff}_{ij}={\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{\beta}_0+{\beta}_1 Malay\;{Share\ Diff}_{ij}+\left({\beta}_2+{\mu}_{1j}\right)\; Population\;{Density\ Diff}_{ij}\\ {}+\hskip2px {\mu}_{0j}+{\varepsilon}_{ij}\end{array}} $$

$$ BN\;{Share\ Diff}_{ij}={\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{\beta}_0+{\beta}_1 Malay\;{Share\ Diff}_{ij}+\left({\beta}_2+{\mu}_{1j}\right)\; Population\;{Density\ Diff}_{ij}\\ {}+\hskip2px {\mu}_{0j}+{\varepsilon}_{ij}\end{array}} $$

Where:

-

•

$ i $

indexes state legislative districts (DUNs)

$ i $

indexes state legislative districts (DUNs) -

•

$ j $

indexes states

$ j $

indexes states -

•

$ {\beta}_0,{\beta}_1,{\beta}_2 $

are fixed-effect coefficients estimated across all districts

$ {\beta}_0,{\beta}_1,{\beta}_2 $

are fixed-effect coefficients estimated across all districts -

•

$ {\mu}_{0j}\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{\mu_{0j}}^2\right) $

is a random intercept specific to state j

$ {\mu}_{0j}\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{\mu_{0j}}^2\right) $

is a random intercept specific to state j -

•

$ {\mu}_{1j}\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{\mu_{1j}}^2\right) $

is a random deviation in the effect of population density for state j

$ {\mu}_{1j}\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{\mu_{1j}}^2\right) $

is a random deviation in the effect of population density for state j -

•

$ {\varepsilon}_{ij}\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{\varepsilon}^2\right) $

is a residual district-level error

$ {\varepsilon}_{ij}\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{\varepsilon}^2\right) $

is a residual district-level error

This specification allows both the baseline level of BN support deviation (

![]() $ {\mu}_{0j} $

) and the effect of population density deviation (

$ {\mu}_{0j} $

) and the effect of population density deviation (

![]() $ {\mu}_{1j} $

) to vary across states. In doing so, the model captures unobserved state-specific heterogeneity, such as political culture or state-level party organization strength, that may moderate the effect of local population density on BN vote share. I also used bootstrap methods to calculate standard errors for estimates.

$ {\mu}_{1j} $

) to vary across states. In doing so, the model captures unobserved state-specific heterogeneity, such as political culture or state-level party organization strength, that may moderate the effect of local population density on BN vote share. I also used bootstrap methods to calculate standard errors for estimates.

Importantly, similar to the model in the previous section the inclusion of a random slope for

![]() $ Population\;{Density\ Diff}_{ij} $

enables the model to assess whether the association between local urbanization and BN support is consistent across states or whether it varies significantly, potentially indicating conditional relationships driven by regional institutional or historical contexts.

$ Population\;{Density\ Diff}_{ij} $

enables the model to assess whether the association between local urbanization and BN support is consistent across states or whether it varies significantly, potentially indicating conditional relationships driven by regional institutional or historical contexts.

The validity of this approach depends on two key assumptions specific to the Malaysian context. First, it assumes that political parties attract relatively consistent electorates across both state and federal levels. Unlike its Southeast Asian neighbors such as the Philippines and Indonesia, where individual politicians often dominate campaigns through personal networks and clientelism, Malaysia’s electoral competition is more party-centered (Aspinall et al. Reference Aspinall, Weiss, Hicken and Hutchcroft2022). Party branding plays a more decisive role than individual candidate appeal, which supports the comparability of vote shares across state and federal contests. Second, the concurrent scheduling of federal and state elections in 2018 reduces the likelihood of unobserved shocks affecting only one level of government, thereby minimizing potential bias in the observed associations.

In electoral systems where political behavior is more candidate-driven, or where elections are held at staggered intervals, this approach would be significantly less valid. In contrast, Malaysia’s party-centered and concurrent electoral structure makes it feasible to investigate intra-district heterogeneity using aggregated data while maintaining a reasonable degree of interpretability. More importantly, previous theories have centered their arguments on the association between population density and party vote share, without mentioning any candidate effects, that is, the design in fact aligns itself with the assumptions from previous studies.

As shown in Figure 6 (see Table A4 for the output table), even after accounting for internal heterogeneity within each district, there remains substantial variation in the relationship between population density and electoral outcomes. Nevertheless, the overall conclusion holds: in all cases, there is no statistically significant association between deviations in population density and BN vote share once both cross-state and within-district heterogeneity are controlled.

Figure 6. Association between Population Density and BN Share by State with Intra-District Heterogeneity Controlled.

The validity of survey data

One remaining question to be answered is how much we can truly trust survey data. If we directly estimate the following baseline model using data from Asian Barometer Survey (Reference Survey2023) we can assess this.

$$ \mathit{\log}\frac{\mathit{\Pr}\;\left( BN\; Vote=1\right)}{1-\mathit{\Pr}\;\left( BN\; Vote=1\right)}={\beta}_0+{\beta}_1 Urban/ Rural+{\beta}_2\; Malay/ Non- Malay $$

$$ \mathit{\log}\frac{\mathit{\Pr}\;\left( BN\; Vote=1\right)}{1-\mathit{\Pr}\;\left( BN\; Vote=1\right)}={\beta}_0+{\beta}_1 Urban/ Rural+{\beta}_2\; Malay/ Non- Malay $$

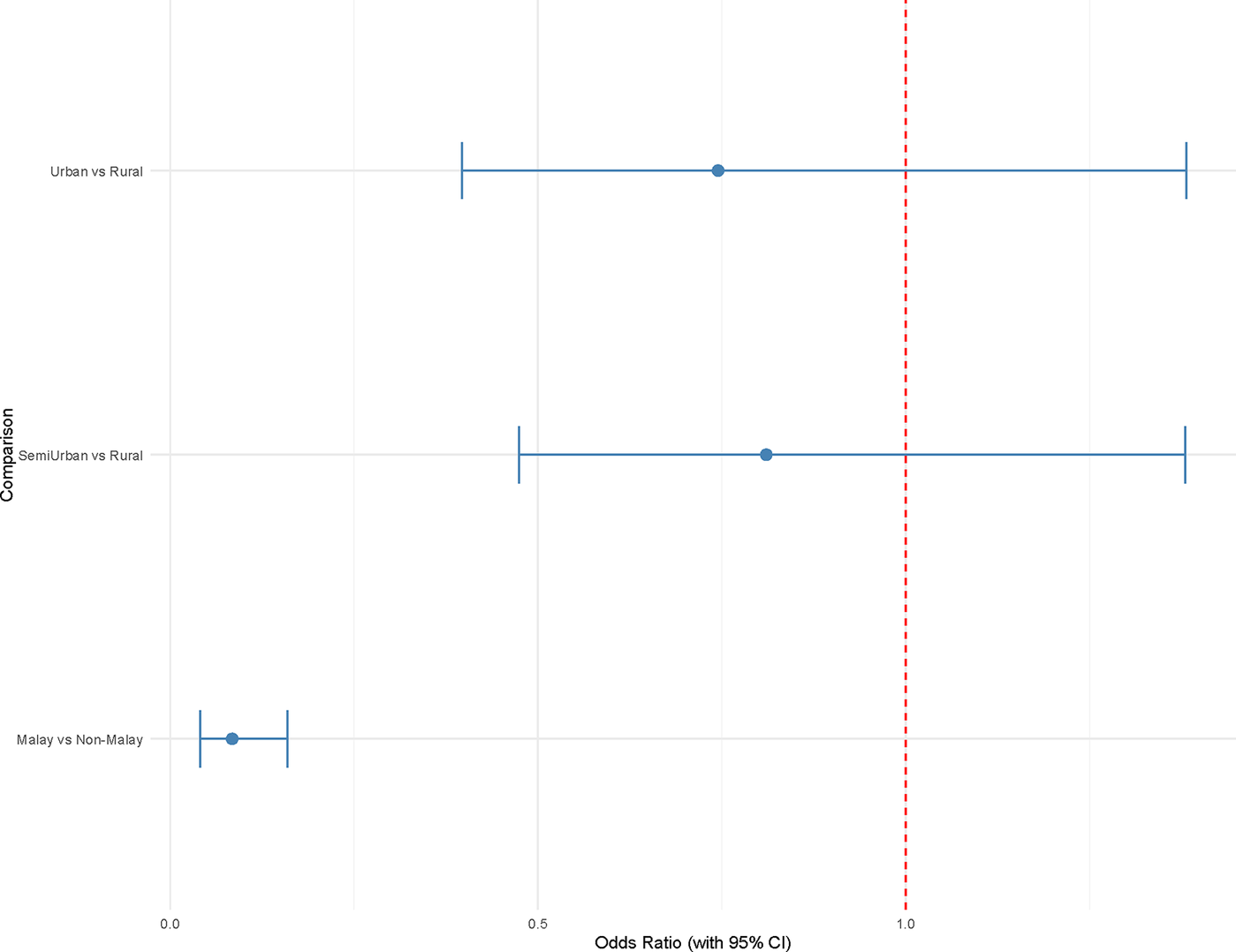

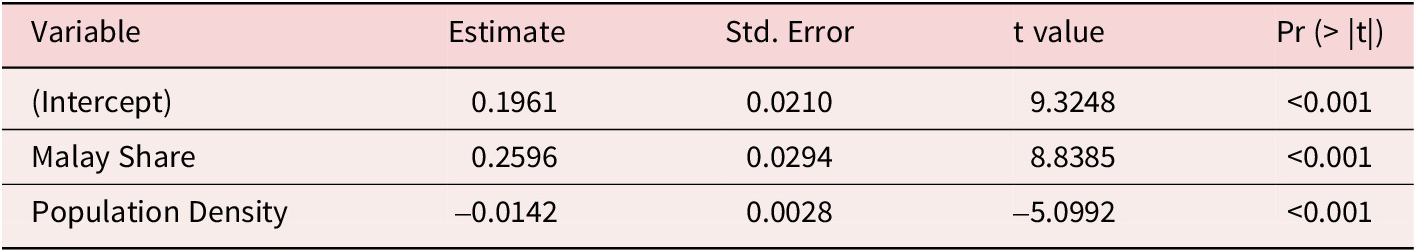

Calculating the odds ratios in Figure 7 from the logistic regression model (see Table A5) we observe a conclusion consistent with Ong (Reference Ong2020). When controlling voters’ ethnic backgrounds, there is no significant difference in the behavior of urban and rural voters.

Figure 7. Odds ratio: Urban/semi-urban vs rural.

To further validate this conclusion, I use survey data to construct a set of “ideally typical” voters. These ideal types represent hypothetical individuals defined by intersecting social and geographic characteristics: ethnic background, urban–rural residency, and region (approximated at the state level within Peninsular Malaysia).

To improve district-level predictions of BN support in the GE14, I employ a multilevel regression with poststratification (MRP) framework. This approach leverages hierarchical modeling to estimate individual-level probabilities of voting for BN, then aggregates these estimates using the demographic structure of each electoral district. I fit a logistic multilevel model predicting the probability that an individual supports BN. The model includes fixed effects for urban–rural residency and random intercepts and slopes for ethnic groups, along with random intercepts for region:

$$ \mathit{\log}\frac{\mathit{\Pr}\left( BN\;{Vote}_i=1\right)}{1-\mathit{\Pr}\left( BN\;{Vote}_i=1\right)}={\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{\beta}_0+\left({\beta}_1+{\mu}_{1j\left[i\right]}\right)\; Urban/{Rural}_i+{\beta}_2\; Malay/ Non\\ {}-\hskip2px {Malay}_i+{\mu}_{0j\left[i\right]}+{\nu}_{k\left[i\right]}\end{array}} $$

$$ \mathit{\log}\frac{\mathit{\Pr}\left( BN\;{Vote}_i=1\right)}{1-\mathit{\Pr}\left( BN\;{Vote}_i=1\right)}={\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{\beta}_0+\left({\beta}_1+{\mu}_{1j\left[i\right]}\right)\; Urban/{Rural}_i+{\beta}_2\; Malay/ Non\\ {}-\hskip2px {Malay}_i+{\mu}_{0j\left[i\right]}+{\nu}_{k\left[i\right]}\end{array}} $$

Where:

-

•

$ i $

indexes state legislative districts (DUNs)

$ i $

indexes state legislative districts (DUNs) -

•

$ {\beta}_0 $

is the fixed intercept

$ {\beta}_0 $

is the fixed intercept -

•

$ {\beta}_1 $

is the fixed slope for the effect of residing in an urban or rural area, denoted by

$ {\beta}_1 $

is the fixed slope for the effect of residing in an urban or rural area, denoted by

$ Urban/{Rural}_i $

$ Urban/{Rural}_i $

-

•

$ {\mu}_{0j\left[i\right]}\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{\mu_{0j}}^2\right),{\mu}_{1j\left[i\right]}\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{\mu_{ij}}^2\right),{\nu}_k\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{Region}^2\right) $

represent the random intercept and slope for group j[i] (individual i’s ethnic group), capturing variation in baseline support for BN and in the urban–rural effect across ethnic groups.

$ {\mu}_{0j\left[i\right]}\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{\mu_{0j}}^2\right),{\mu}_{1j\left[i\right]}\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{\mu_{ij}}^2\right),{\nu}_k\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{Region}^2\right) $

represent the random intercept and slope for group j[i] (individual i’s ethnic group), capturing variation in baseline support for BN and in the urban–rural effect across ethnic groups.

$ Corr\left({\mu}_{0j},{\mu}_{1j}\right)={\rho}_{Ethic\ Group} $

and

$ Corr\left({\mu}_{0j},{\mu}_{1j}\right)={\rho}_{Ethic\ Group} $

and

$ {\rho}_{Ethic\ Group} $

is the correlation between the random intercept and slope for ethnic groups.

$ {\rho}_{Ethic\ Group} $

is the correlation between the random intercept and slope for ethnic groups.

Predicted probabilities of BN support are then generated for every possible combination of the three stratifying variables, ethnic group, urban–rural status, and region, forming a comprehensive set of ideal types:

These predicted probabilities reflect model-implied support for BN among individuals with specific socio-geographic profiles. To estimate BN support in each electoral district d, the predicted probabilities are weighted by the district’s actual ethnic composition:

Where:

-

•

$ {{\hat{\mathrm{p}}}_{\mathrm{jrk}}}_{\mathrm{d}} $

is the predicted probability of a BN vote for ethnic group j in district d’s region and urban–rural classification

$ {{\hat{\mathrm{p}}}_{\mathrm{jrk}}}_{\mathrm{d}} $

is the predicted probability of a BN vote for ethnic group j in district d’s region and urban–rural classification -

•

$ {\omega}_{jd} $

is the proportion of ethnic group j in district d

$ {\omega}_{jd} $

is the proportion of ethnic group j in district d

This yields district-level estimates of BN support that account for both modeled behavior and observed demographic structure. Model performance is assessed by comparing estimated district-level BN vote shares BN against actual results. I compute the mean absolute error (MAE) and the Pearson correlation coefficient (where D is the number of districts):

These metrics indicate how well the model captures variation in support for BN across different electoral contexts. As shown in Figure 8, the three variables alone produce a reasonably accurate estimate of the actual election results, with an MAE of 0.08 and a correlation coefficient of 0.71. Thus, the case of Peninsular Malaysia illustrates a plausible scenario that reconciles the positions on both sides of the debate: using simulated data based on the surveys we can reproduce the observed election results with a significant degree of accuracy.

Figure 8. BN: MRP estimate vs actual.

Discussion

In this article I conducted an extensive analysis of both aggregated election data and individual-level survey data from GE14 in Peninsular Malaysia, aiming to provide a comprehensive review of a decade-long debate. At the aggregate level, political coalitions tend to perform differently in densely populated (urban) versus sparsely populated (rural) areas. However, this does not reflect individual-level differences in voting behavior between urban and rural-based voters. Instead, this pattern diminishes once we control across-state and within-district heterogeneity. In fact, once ethnic background is accounted for, urban and rural voters exhibit similar voting patterns.

I highlighted the importance of considering the broader context in which data are situated, as overlooking these factors can sometimes lead to biased interpretations, particularly when working with aggregated election data. This research demonstrates that by carefully addressing biases related to model and variable selection, both aggregated election results and survey data can yield consistent insights. While it is important to remain cautious of ecological fallacy, election results remain a valuable resource for studying electoral politics, particularly in contexts where high-quality survey data are limited. In Malaysia, for instance, only a few institutions, such as the Merdeka Center, consistently produce reliable survey data. Thus, rather than dismissing election data entirely due to concerns about ecological fallacy, a careful and rigorous approach to analyzing such data can provide meaningful contributions to our understanding of electoral dynamics.

The result of this analysis has implications for two questions of significant gravity. First, how should we understand Malaysian politics? As this country continues to face the challenges of democratization, does the fundamental cleavage within Malaysian society shift? Based on the analysis in this article, I argue that ethnic cleavages will continue to dominate the landscape of political competition. In the foreseeable future, Malaysian political parties are likely to form cross-ethnic coalitions while maintaining their distinct ethnic identities. Indeed, campaign politics and policymaking in Malaysia have largely followed this ethnic-based logic, with little change even years after PH’s takeover. For example, in recent trade talks with the United States, Malaysian diplomats reaffirmed that preserving Bumiputera/Malay-oriented economic development policy remained a non-negotiable priority.Footnote 8 As scholars, we should remain cautious about the extent to which ethnic politics might recede in a democratizing Malaysia. The recent reconciliation among Malay-dominant parties, Bersatu, PAS, and Parti Pejuang Tanah Air (Homeland Fighters’ Party, Pejuang), illustrates that such campaign strategies continue to hold significant appeal in Malaysian politics.Footnote 9

Second, does the urban–rural divide not matter? This article does not support such a conclusion. Rather, as I have consistently argued, urban–rural differences matter—though not to an extent that surpasses the influence of ethnic politics. Spatial heterogeneity, both within and across districts, has contributed to the divergence between aggregated results and individual voting behavior. Future studies could build on this by examining why spatial heterogeneity produces such divergences. Is it solely the product of BN’s deliberate gerrymandering? Or does it arise from the higher concentration of ethnic minorities in urban areas? Ultimately, however, we should be cautious not to overstate the role of urbanization in Malaysia’s electoral turnovers. In a country with small electoral districts, even a small number of defections in each constituency can lead to substantial shifts in outcomes. Indeed, the fragmented electoral landscape that emerged after BN’s downfall has borne out this perspective.

I hope this article encourages scholars of Malaysian politics to move beyond this binary debate and instead examine the evolving nature of social cleavages that may shape the country’s political landscape in the years ahead.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Robert Franzese, Mary Gallagher, Allen Hicken, Wooseok Kim, Walter Mebane, and Dan Slater for consistently providing feedback on this project at various stages. I am also grateful to my fellow group members in the Interdisciplinary Workshop on Comparative Politics (IWCP), where Brian Min and Ken Mathis Lohatepanont discussed my article, and the Southeast Asia in Social Sciences (SASS) Workshop at the University of Michigan for their valuable feedback on my initial proposal. Additionally, I thank Catherine Morse for her assistance in acquiring the data. Finally, I want to thank the Journal of East Asian Studies editorial team, especially Thomas Pepinsky, and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments during the review process. All errors and mishaps are my own. The data and codes for replication can be found at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/tylercrmmse.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Appendix

Remaining methodological challenges

One issue for which I do not provide a definitive answer is the extent to which internal migration influences election outcomes, a question raised by scholars on both sides of the debate (Ong Reference Ong2020; Ng et al. Reference Ng, Rangel and Chin2021a). Studying within-country migration is particularly challenging because, counterintuitively, demographic variation within a country can be greater than variation between countries (Yu et al. Reference Yu2023). Analytically assessing the influence of internal migration would require, at a minimum, estimates of the fertility rate in each constituency and comprehensive national census data. Unfortunately, such data are scarce in Malaysia. Accurately estimating this impact would require more sophisticated research designs that are beyond the scope of this article.

Nonetheless, I also remain cautious about overstating its influence. According to data from the Department of Statistics Malaysia (2017), only 1.8 percent of Malaysians over the age of one migrate internally each year. While I acknowledge that even small-scale migration can significantly affect electoral outcomes under Malaysia’s first-past-the-post system, I argue that its effect on overall party vote shares is likely to be marginal.

Another important issue, though beyond the scope of this article, is how to define urban and rural districts. The concept of “urban” varies widely across different theories and frameworks. Generally, population density is the most common proxy for measuring urban–rural differences (Long et al. Reference Long, Delamater and Holmes2021). However, as Ong (Reference Ong2020) rightly observes, the perceived urban–rural divide may simply reflect a combination of latent factors such as education, income, and others, a view I share. Defining what constitutes “urban” in the Malaysian context could open up a broader debate that warrants separate and in-depth examination.

One reason I consider population density to be the most useful proxy in the Malaysian context is that arguments for the impact of urbanization on mitigating ethnic politics often rely on the classic assumption from modernization theory: that individuals develop greater tolerance in democratizing societies, a claim that can be traced back to Lipset (Reference Lipset1959). Urban areas are hypothesized to be sites where people from diverse backgrounds meet and form connections. Therefore, within the context of this debate, population density remains a powerful and relevant variable.

Some may also question the exclusion of malapportionment of electoral districts from the measurement. One important concern that people may raise is that malapportionment is correlated with urban–rural divide in the Malaysian context (Ostwald Reference Ostwald2024), so it would be wise to explicitly control for it. Ng et al. (Reference Ng, Rangel and Chin2021a) included a z-score of population density as a proxy for malapportionment, which is a commonly accepted method of controlling for uneven population sizes across electoral districts (Chen Reference Chen2010; the results from the regression featuring z-score are shown in Table A1). The reason I exclude this variable in this article is that the Election Commission (EC) under BN’s rule is believed to electoral districts based primarily on two criteria: the proportion of the Malay population and population density, precisely the two explanatory variables that I aim to decompose in this study. In fact, the EC report on re-delineation right before GE14 explicitly acknowledged that they intentionally redrew districts to integrate urban areas with their surrounding rural areas for the convenience of voters, although they did shirk any accusations of political intentions behind this rationale. (see Suruhanjaya Pilihan Raya Malaysia (The Electoral Commission of Malaysia) (2024), 14). Including malapportionment would introduce at least two problems. First, it would be difficult to eliminate the influence of multicollinearity, as malapportionment is inherently correlated with both explanatory variables. Second, it would create a reverse causation problem, since areas where BN receives fewer votes are often those that experience higher levels of gerrymandering their surrounding rural areas for the convenience of voters, although they did shirk any accusations of political intentions behind this rationale. (see Suruhanjaya Pilihan Raya Malaysia (The Electoral Commission of Malaysia 2024), 14). Including malapportionment would introduce at least two problems. First, it would be difficult to eliminate the influence of multicollinearity, as malapportionment is inherently correlated with both explanatory variables. Second, it would create a reverse causation problem, since areas where BN receives fewer votes are often those that experience higher levels of gerrymandering.

Table A1. Bootstrapped estimates and 95% CIs for association between population density and bn vote share (with z-score added as a control variable)

Influential Points

I can conduct a more precise analysis to determine which types of districts are skewing our estimates. I estimated the baseline model in the equation below, and the results, presented in Table A2, follow the default approach commonly used in studies that examine the urban–rural divide in Peninsular Malaysia. A closer look at the Cook’s Distance bar plot (Figure A1), which measures the change in all fitted values when a given observation is removed, where larger values indicate greater influence on the model’s coefficients, shows that highly populated districts exert disproportionate influence on the estimates. The three most influential cases are P.50 (Jelutong, Pulau Pinang), P.116 (Wangsa Maju, Kuala Lumpur), and P.121 (Lembah Pantai, Kuala Lumpur).

Figure A1. Cook’s distance

Table A2. Linear regression results: Baseline model

Residual standard error: 0.08541 on 162 degrees of freedom.

Multiple R-squared: 0.5272, Adjusted R-squared: 0.5213.

F-statistic: 90.3 on 2 and 162 DF, p-value: < 0.001.

Table A3. Bootstrapped estimates and 95% CIs for association between population density and BN vote share

Table A4. Bootstrapped estimates and 95% CIs for association between population density and BN share by state with intra-district heterogeneity controlled

Table A5. Logistic regression results

Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1.

Null deviance: 520.06 on 446 degrees of freedom.

Residual deviance: 427.28 on 443 degrees of freedom.

AIC: 435.28.

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 5.

Tyler Rongxuan Chen is a PhD student in Political Science and Scientific Computing at the University of Michigan. His research interests lie at the intersection of social demography and party politics, with area foci on East and Southeast Asia.