In 1777, the Spanish official, Antonio de la Torre y Miranda, founded the town of Montería on the banks of the Sinú River. As was typical in the Caribbean region of what is now Colombia, much of the population lived beyond the ‘guiding’ influence of civil and ecclesiastical authorities. De la Torre had already spent several years resettling the region’s inhabitants to solidify imperial control and foment economic growth. As the southernmost Spanish settlement along the Sinú River, de la Torre also hoped to turn Montería into a waystation on an overland trail connecting the province of Cartagena to the gold mines in Chocó. This latter project never materialized. Instead, just six years after its founding, Guna (Kuna) Indians from the Darien burned Montería to the ground.Footnote 1

After residents rebuilt their town, and the Indian raids subsided, the ties between Montería and the Darien became a distant memory. For years Montería remained a sleepy outpost at the edge of the ‘civilized’ world. Long-term French resident, Louis Striffler, described the region south of town, in the 1840s, as a ‘green desert’ of tropical forest.Footnote 2 The establishment of Franco-Belgian cacao plantations, and the arrival of American lumbermen, in the 1880s marked a ‘turning point’.Footnote 3 The increased demand for labour and services helped transform Montería into a frontier boomtown. Within several decades, its population jumped fivefold to eclipse Lorica as the economic capital of the Sinú Valley. By the 1930s, local elites, smug with the region’s progress, embarked on a twenty-year project to create their own department, Córdoba, with Montería as its capital. As scholars sought to explain the economic development of the Sinú Valley, they looked to Europe and the United States, or south to Antioquia.Footnote 4 What they have missed—whether they view foreign investment as a dynamizing force, like James Parsons, or criticize it as a source of dependency, like Orlando Fals-Borda—is the significance of the Darien for Montería’s growth, and the role of the Sinú Valley in the origins of the Panama Canal.Footnote 5

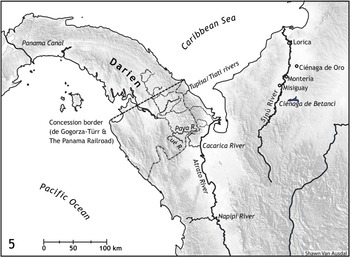

Despite their proximity, the connections between these two regions were, surprisingly, woven together with ‘fragile threads’ that stretched far across a globalizing Atlantic.Footnote 6 Tracing these filaments takes us on a journey from France to the Americas; from Colombia to California; between Europe and the United States; and back and forth between Paris, Montería, and the Darien (see Figures 1 and 2). They also draw our attention to the neglected figures whose ‘lifepaths’ spun this gossamer web: André Anthoine (who later changed his name to Anthoine de Gogorza) and Louis Lacharme.Footnote 7 In other words, to recover the lost origins of the Panama Canal, and develop a clearer understanding of how foreign capital flowed into Colombia’s Sinú Valley, we need to look beyond the nation as well as follow the trajectories of individual actors.

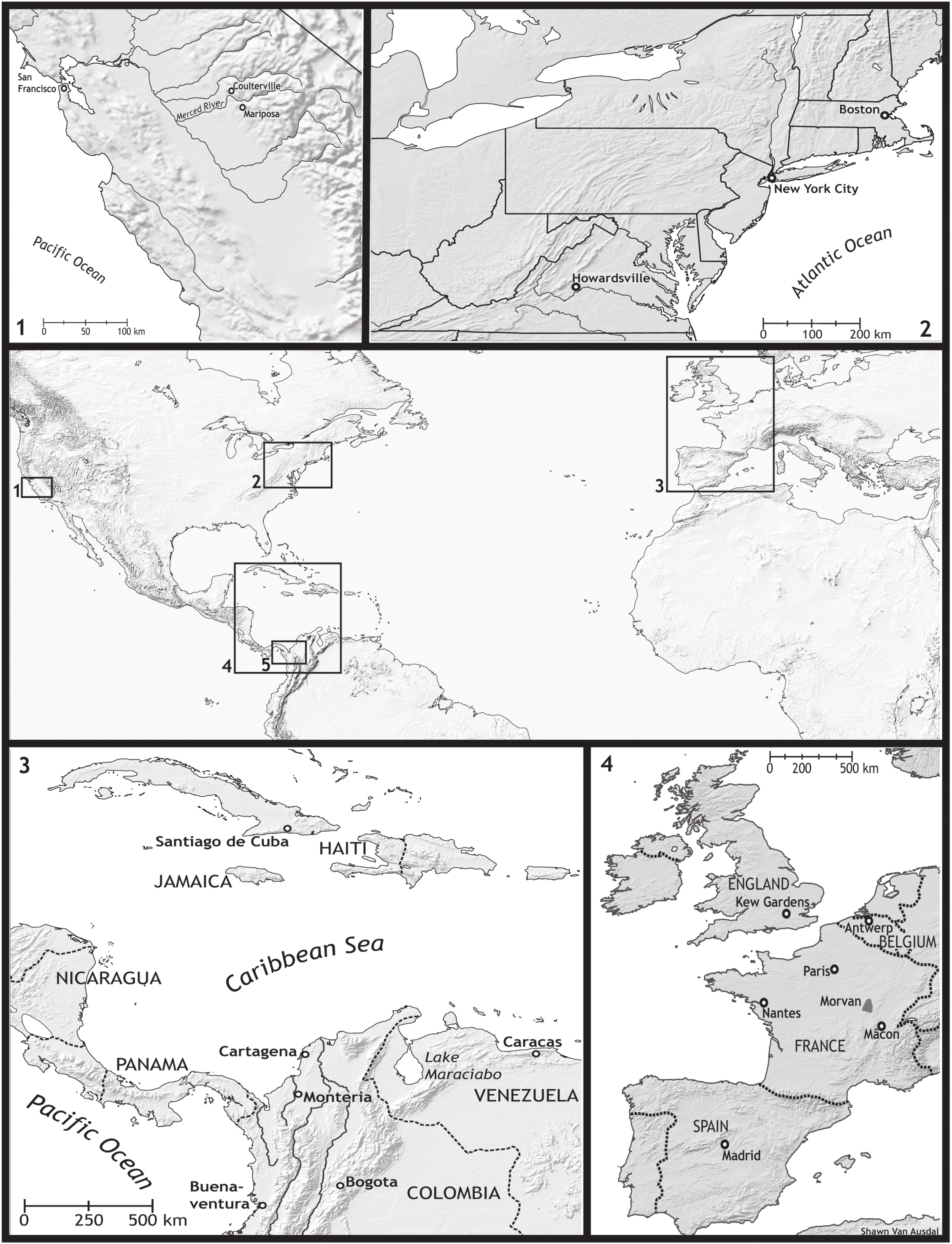

Figure 1. The worlds of de Gogorza and Lacharme.

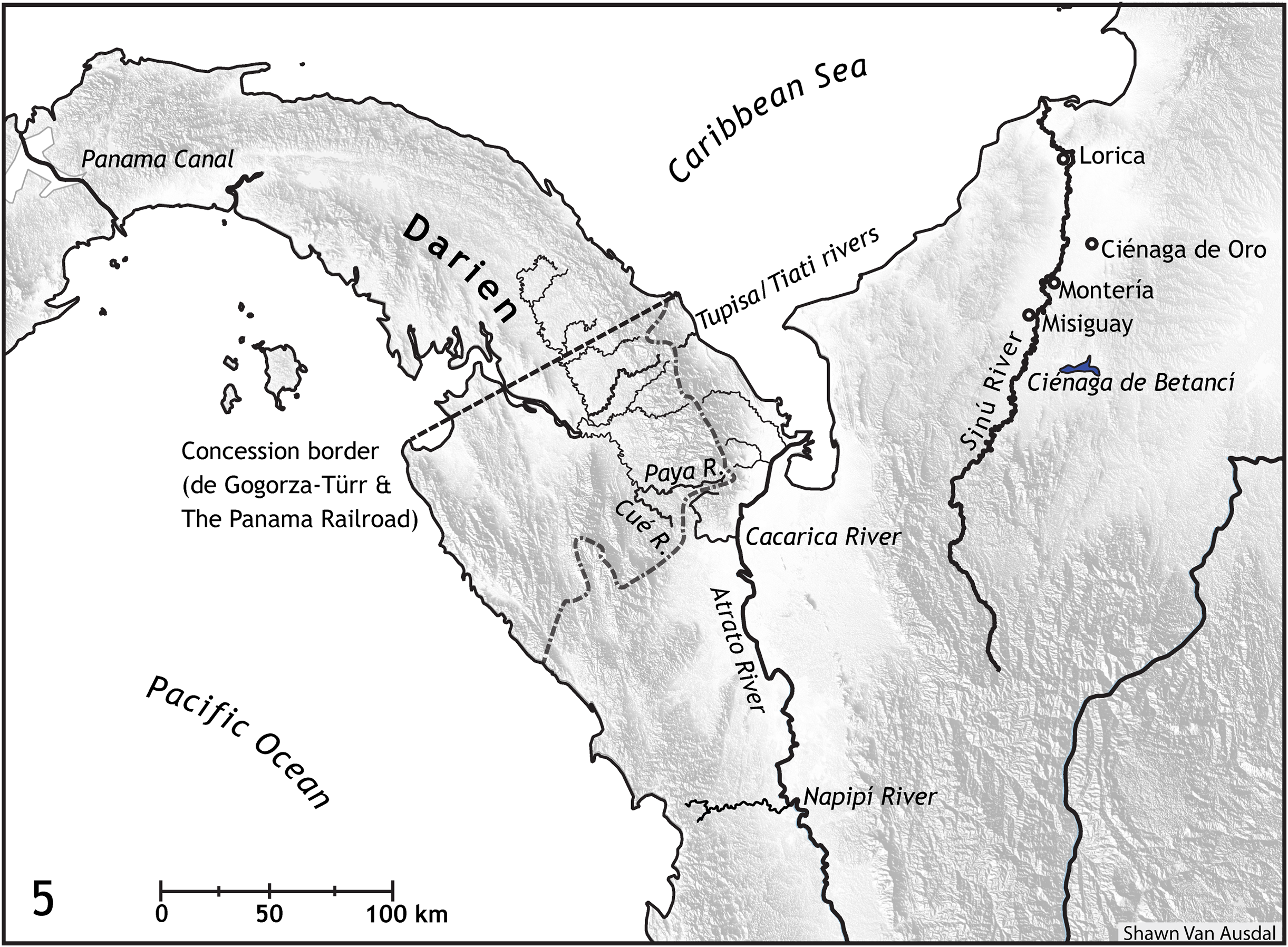

Figure 2. The Darien and the Sinú Valley.

The story of the Panama Canal has been told many times. Yet the path that led Ferdinand de Lesseps to break ground in 1881 remains hidden behind a narrative structure that juxtaposes ‘French Failure’ and ‘American Triumph’ (or emphasizes American imperialism).Footnote 8 By 1889, the enormous cost in lives and capital, exacerbated by mismanagement and graft, drove de Lesseps’s French company into bankruptcy. By contrast, the Americans were said to be ‘driven less by idealism than national … ambition’ and, backed by ‘scientific and technical expertise’, picked up the pieces and completed the project.Footnote 9 With the drama focused on national rivalries, how the French became involved was of minor concern. Only Gerstle Mack’s thorough history of the canal mentions Anthoine and Lacharme; but he dismisses theirs as one of ‘[h]alf a dozen projects, all hopelessly impracticable [that] emanated from France’.Footnote 10 The pair of entrepreneurial adventurers were French, but they emigrated to Colombia’s Sinú Valley in the 1840s. Anthoine (under the name de Gogorza) discovered a route across the Darien in Spain’s colonial archives and promoted it in the United States and Europe. The low-lying pass his partner, Lacharme, purportedly found captivated de Lesseps’s circle. His claim to have personally crossed the isthmian divide, unlike Lionel Gisborne, Lucien de Puydt, and other explorers, gave the passage credibility. What helped Lacharme navigate this formidable region was fifteen years of experience in the tropical forests of the Sinú Valley.

Similarly, Colombian historiography has found foreign investment of interest only once it entered the country; how it arrived was beside the point. A few histories of the Sinú Valley mention Anthoine and Lacharme, but they hardly glance beyond the region’s borders.Footnote 11 As a result, both men’s work in the Darien and their global escapades go unnoticed. Likewise, the pair appear in accounts of French explorers in the Darien, but their connections to the Sinú are ignored.Footnote 12 Weaving these narrative fragments together is key: peel back the layers of the Franco-Belgian companies that invested in the Sinú and we find Lucien N. B. Wyse, Louis Verbrugghe, and possibly István Türr, key figures in the initial scheme of de Lesseps’s canal project. Lacharme’s ability to manoeuvre through the tropical forest enthralled them and lent authority to his views on the region’s potential. In other words, deep ties to the Sinú Valley helped a pair of French speculators captivate the interest of de Lesseps and company; and the resulting explorations opened a portal to foreign investment in the Sinú. To uncover these connections, and their surprising sources of finance, we must look global and go micro.

It is now a well-worn mantra that History suffers from a disciplinary ‘birth defect’: an overriding obsession with narrating the nation.Footnote 13 National history has much to offer besides the project of nation-building. Shared structures and meanings, in part the result of state institutions and regulations, as well as the circulation of people, goods, and ideas within a sovereign territory, give a particular coherence to national histories. But methodological nationalism has also discouraged the exploration of stories at larger scales or across transnational spaces; and it has fostered the adoption of Eurocentric models of historical change. Overcoming such limits has been one of the promises of the global turn: to draw out of the shadows stories, processes, and connections by reimagining the spaces of history.

Latin America has been slow to jump on the global history bandwagon. Of course, influences beyond the nation were never entirely ignored. ‘Obviously’, proclaim Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Enzo Faletto, ‘Latin American societies have been built as a consequence of the expansion of European and American capitalism.’Footnote 14 But such connections—typically rooted in capital flows and import–export statistics—tended to remain abstract. Some historians of Latin America highlight the structural challenges of doing global history from the margins, such as limited funding, tepid institutional interest, and inward-looking research collections.Footnote 15 Others feel out of place in its ‘West/rest dichotomy’ and ill-fitting periodizations.Footnote 16 This reluctance resonates with broader scepticism about the global turn—questioning the emphasis on ‘motion over place’, globetrotters over the sedentary, flattened topographies of power—and fear of a resurgence of Eurocentric narratives.Footnote 17

Such risks exist, but they aren’t intrinsic to a global perspective. As Doreen Massey reminds us, mobility and privilege are not synonymous, and places are constructed through global connections as much as local traditions.Footnote 18 In the end, many of the critics favour alternative kinds of stories—about hybridity, disintegration, and the geopolitics of knowledge—rather than rejecting a global spatial frame. And a new generation of Colombian scholars has begun to explore transnational connections and propose new spatialities to reframe national narratives.Footnote 19 Their stories also complicate the perception of Colombia as a global backwater. Despite low levels of immigration, foreign investment, and exports, connections to currents circulating around the Atlantic world remained vital.

Speculators, like Anthoine and Lacharme, both rode and helped create these currents. Yet few historians have paid such figures much heed. Of greater interest to business historians of nineteenth-century Latin America have been foreign merchants and free-standing companies. Unlike multinationals, which tended to develop expertise at home before expanding abroad, free-standing companies were created to take advantage of specific overseas investment opportunities.Footnote 20 While the relative merits of their lean management structures have generated debate, the role of speculators in their formation has been neglected.Footnote 21 Thousands of adventurous entrepreneurs from Europe and North America fanned out across Latin America over the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.Footnote 22 While most of their schemes flopped or developed at a local scale, these promoters were instrumental in connecting local opportunities with northern capital markets. Following such speculative ventures sheds light on, in this case, the business of exploration, frictions between science and commerce, local dissatisfaction with liberal economic policies, and the global networks that channelled foreign capital to Latin America. To do so requires that we scale down.

Following people through the archives as well as across the vast spaces of an interconnected world has been a strategy of global microhistory. At one level, such microscopic studies enable individuals to serve as ‘keyholes through which to view the worlds in which they lived’.Footnote 23 As an antidote to the soulless ‘structures and processes of world history’, Tonio Andrade advocates using this micro perspective to ‘bring the history of our interconnected world to life’.Footnote 24 However, some historians fear that simply adding ‘picturesque details’ to existing historical models could resurrect a long-standing critique of microhistory ‘as a form of escapism’.Footnote 25 The original aim of (Italian) microhistory was not to bring the past alive, counters Francesca Trivellato; it sought ‘to test the validity of macro-scale explanatory paradigms’ by radically narrowing the scale of analysis.Footnote 26 Divisions reappear over the reach of this revisionism. While many suggest that ‘[g]eneralization is a key element in microhistory’, others disagree.Footnote 27 Microhistory encourages us to ask new, even sweeping questions, Giovanni Levi argues, but the answers will always be ‘local’.Footnote 28

To economic historian Jan de Vries, this ambivalence towards generalization undermines the very purpose of the discipline—namely, to explain change over time. But de Vries’s critique is deeper: by adopting a synchronic approach and focusing on sociological outliers, microhistory cannot generalize: ‘There is no path, no methodology, no theoretical framework in the current repertoire of the microhistorian’ to move from micro to macro-level analyses.Footnote 29

While I agree with de Vries’s insistence on looking for ‘patterns, trends and regularities’, these efforts can create their own blinkers.Footnote 30 For instance, Alan Taylor’s admirable overview of capital flows to Latin America emphasizes arbitrage opportunities, risk perception, and the macroeconomic environment.Footnote 31 But these factors only partially help us understand foreign investment in Colombia where economic conditions were less favourable. Fals-Borda takes an alternative approach, suggesting that foreign entrepreneurs were ‘bewitched’ by the tropics and the riches they concealed.Footnote 32 But this begs the question of how they became enchanted. Despite the increased flow of information, capital, and people over the nineteenth century, such circulation was not simply the product of disembodied responses to abstract economic signals or popular imaginaries. Instead, it flowed through people, institutions, and networks. The density of such connections, not just variations between economic indicators, helps explain uneven rates of foreign investment. Following entrepreneurial lifepaths sheds light on the webs and contingencies that shaped foreign investment in Colombia’s Caribbean region.

Additionally, some histories seek to explain events instead of (or in addition to) patterns.Footnote 33 While the two are closely bound, the former requires highlighting the particular rather than just searching for generalizations. Such efforts do not necessarily replicate discarded notions about ‘the great men of history’, as critical exploration studies have shown.Footnote 34 For some historical puzzles, we need to follow people, not just the money. ‘The glory of microhistory’, Richard Brown suggests, ‘lies in its power to recover and reconstruct [the] past … in which actual people as well as abstract forces shape events.’Footnote 35 In other words, to recover the forgotten origins of the Panama Canal, as well as better understand the flow of capital to the Sinú Valley, we need to follow the lifepaths of Anthoine (de Gogorza) and Lacharme from both a global and micro perspective. In turn, this story draws attention to the overlooked figure of the speculator in the globalizing nineteenth century, complicating the way we think about the business of exploration, marketing the tropics, and informal imperialism.

Origin Stories

Anthoine de Gogorza, born André Anthoine in Nantes in 1810, first arrived in the Sinú Valley in 1843. The son of a merchant in the colonial trade and occasional slave trader, Anthoine was sent to Santiago de Cuba at the age of sixteen, presumably to learn the family business.Footnote 36 While Anthoine still considered himself a merchant in 1836, the following year he tied his fortunes to the natural resources of the American tropics.Footnote 37 Venezuelan lawmakers had just authorized the immigration of European labourers from beyond the Canary Islands, prompting Anthoine to bring fifty Germans, and a steam-powered sawmill, to work his lands on the western shores of Lake Maracaibo.Footnote 38 This global trade in labour must have seemed promising, for the following year he arranged the transport of ninety-five French immigrants.Footnote 39 Anthoine offered to sell their contracts to anyone willing to reimburse his expenses; his profits would come from new state subsidies. The onerous terms of these contracts shocked the French consul in Caracas: ‘Has bread become so scarce in France’ that able-bodied men would travel so far ‘to beg a few bananas, some manioc, and find their grave?’Footnote 40 His repugnance may have prompted Anthoine to see Spanish refugees as less problematic.Footnote 41 Yet they proved harder to attract due to growing concern about the rights of foreigners in Venezuela and the magnetic draw of the United States.Footnote 42 Having already accepted a substantial advance from the Venezuelan state, Anthoine could either return the funds or skip town.Footnote 43

In 1843, he travelled to Cartagena and the Sinú Valley, where he became intrigued by a latex used to make torches and a cloth-like insect barrier.Footnote 44 Rubber had captured the world’s attention as new forms of processing expanded its applications. Demand grew ninefold in the 1830s and 1840s.Footnote 45 While most globally traded rubber was harvested in the Brazilian forests of Pará and Manaus, Anthoine illustrates how speculators had already started probing new areas for alternative sources of supply. After surveying parts of Central America, he decided to export rubber out of Lorica, the principal port on the lower Sinú River, with another French adventurer, Louis Lacharme.

Lacharme arrived in Colombia in 1844 as the machinist on a gold-mining venture on the upper Sinú River.Footnote 46 His extended family were rural labourers in the Grosne River Valley, near Mâcon. However, his father, Jean Baptiste, had broken out of this insular world at the end of the Napoleonic wars only to enter another: the Morvan, a rugged region of poor granitic soils and extensive forests. It’s unclear what drew him to this impoverished region where wet nurses were a significant export once decent roads began to break its isolation in the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 47 Yet there was a dynamism to Jean Baptiste, who ascended from the status of a wage labourer in 1822 (the year Louis was born) to an estate manager and tenant farmer, who likely sublet his land to sharecroppers, to a property owner by 1832 and the prize-winning breeder of Morvandeau cattle and sheep.Footnote 48 This social mobility likely enabled Louis to become a skilled machinist and acquire refined manners. Striffler even thought Lacharme was of ‘noble extraction’, a notion fomented by the deterritorialized social relations of frontier life.Footnote 49

The gold-mining endeavour that employed Striffler and Lacharme was the brainchild of Victor Dujardin, a French merchant of dubious reputation who had arrived in Cartagena by 1833.Footnote 50 The Compañía Minera del Alto Sinú was partly the product of renewed confidence in the mining sector after the dashed expectations of the post-Independence slump. The authoritative Parisian laboratory of Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac, which assessed samples of alluvial sands from the upper Sinú River, further churned the frothy expectations of European and Colombian investors. Yet with sardonic hindsight, Striffler suggests the scheme was mostly a ‘puff’, using the English word to describe the exaggerated prospects ‘employed by men of imagination to make money by exploiting the same craving in others’.Footnote 51 This was a common problem among free-standing companies, which often bolstered their untested reputations by naming high-ranking figures to decorative positions.Footnote 52 While Striffler managed the company’s day-to-day operations, Jean Pavageau—a wealthy merchant from Jamaica (via Haiti), friend of Simón Bolívar, and the French consul in Cartagena—became its director. In France, Dujardin contracted three engineers as well as a chef, carpenter, and machinist (Lacharme). While the amount of gold extracted from the alluvial sands was less than anticipated, the engineers also found the frontier living conditions untenable and the local labour insubordinate. By the time a flood washed away some of the company’s equipment, the French recruits had half-packed their bags. Only Lacharme decided to stay.Footnote 53

Anthoine and Lacharme established a commercial house in Lorica by 1847 to export Castilla rubber.Footnote 54 After devising a suitable processing method, it took considerable coaxing—with gifts, not just advances—to convince residents of indigenous communities to supply them with sufficient latex. Their eventual success aroused the jealously of local elites. In May 1848, anti-foreigner protests erupted in Lorica. Prompted by a commercial dispute and animated by ‘hostile’ officials, crowds called for the ‘expulsion of the foreigners who come to seize the land and remove the riches that belong to the sons of the country’.Footnote 55 While liberal economic policies had gained ground nationally, locally foreign investment could appear threatening. The vitriolic outburst convinced Anthoine and Lacharme to abandon their operations and retreat to Cartagena. The French legation remonstrated against the state’s wilful disregard for the rights of its citizens. In an era of gunboat diplomacy, President Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera worried that this minor affair could blow up, damaging the country’s reputation and costing its treasury ‘enormous sums’.Footnote 56 Yet his entreaties to the provincial governor and local officials fell on deaf ears, highlighting the fissures of power even within a clientelistic state. Nothing came of the affair and, in late 1848, Anthoine returned to France to appeal the classification of their rubber as processed rather than raw, which increased the tariff.Footnote 57 With their business paralysed, a fate common to many foreign speculative ventures, Lacharme kept his ears open for more promising horizons. What happened next takes us well beyond the typical confines of national history.

Golden California

News likely to seduce an adventurer already committed to the trials of frontier life somehow seeped into Cartagena: a gold- and gem-mining boom in the foothills of Virginia.Footnote 58 There is little information on Lacharme’s sojourn along the Rockfish River near Howardsville.Footnote 59 Likely it didn’t last long since President James Polk’s confirmation of the discovery of gold in California, on 5 December 1848, encouraged Lacharme and many other Virginia miners to race west.Footnote 60 He was in San Francisco by early 1849 where he provided the French newspaper, Le Siècle, with information on the conditions awaiting would-be-miners.Footnote 61 It’s unclear if he spoke from first-hand experience since he spent some of his time tinkering with a gold-washing machine, for which he earned a patent in October 1849.Footnote 62 His other important achievement, facilitated by the flux of a mining boom, was social mobility: Le Siècle introduced Lacharme as a civil engineer and the former manager of a gold mining company in South America. This new-found status would become central to the subsequent mining ventures of Lacharme and Anthoine.

The record of Lacharme’s California mining endeavours begins with a letter dated 1 May 1851 from John C. Frémont to David Hoffman.Footnote 63 Frémont, a celebrated explorer of the American West and officer in the Mexican–American War, bought a sprawling but ill-defined land grant in 1847. Purchased sight-unseen, part of the mad rush by US army officers to snap up land rights in the wake of conquest, the 70 square-mile estate lay in the distant foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains, much to Frémont’s initial consternation. The discovery of gold changed his mind. In early 1849, Mexican miners sifted a 100 pounds of gold per month from the streams of his property, Las Mariposas. Yet it was the discovery of the rich Mariposa lode—a 5-mile-long quartz vein expected to yield over $16 million a year—that generated the most excitement.Footnote 64 Because quartz-rock mining is so capital intensive, Frémont sought European partners. Yet faced with a timid market, following the initial exuberance for California mining companies, he continued to grant leases locally. Most of these would soon expire, he tried to reassure his frustrated European representative, David Hoffman; and he had only extended the terms for three promising parties. One of these was Louis Lacharme, ‘who in company with Mr. Antoine [sic], & Mr. Swift went up yesterday to the Mariposas’.Footnote 65

Lacharme used Frémont’s lease to create a joint-stock company in Paris on 15 August 1850. Anthoine, still in Paris, filed the paperwork and became a shareholder.Footnote 66 By 1852, Lacharme had raised 250,000 francs (about US$49,000), half of the company’s authorized capital, and V. Marizou et Compagnie, a global shipping firm from Le Havre, took on an independent supervisory role (conseil de surveillance).Footnote 67 Rather than break ground at Las Mariposas, which was overrun with squatters, Lacharme leased the Adeline Vein, near Coulterville, on 20 May 1851.Footnote 68 Within a year, he and Anthoine expanded their operations to include several nearby claims. The monarchist author, Henry de Riancey, sang the praises of Lacharme, likely at the behest of Louis-Victor Marizou, the ardent Catholic shipping magnate who financed the Société de l’Océanie, a Marist missionizing effort that stretched from the South Pacific to Oregon.Footnote 69 Gustave Touchard, transferred from Tahiti to run Marizou’s San Francisco office in 1852, helped make it one of the wealthiest enterprises in the city and kept tabs on Lacharme’s mining company. While de Riancey averred that the relatively small size of Lacharme et Compagnie would ensure greater economy, in reality it assured financial vulnerability. Given the high costs of establishing a mine, Lacharme and Anthoine burned through their operating capital within a year. Faced with insolvency, salvation came not from pro-Catholic French circles but British investors who also felt betrayed by Frémont.

In January 1852, the Quartz Rock Mariposa Gold Mining Company (QRM) acquired the lease granted by Frémont to Lord Erskine and quickly raised about two-thirds of its authorized capital of £60,000 (about US$290,000).Footnote 70 The directors then hired a German metallurgist with mining experience in Mexico and purchased two state-of-the-art ore-crushing machines. However, when Schmitz arrived at Las Mariposas in August 1852, Frémont’s agents ‘refused to put [him] into possession of the mines’.Footnote 71 Schmitz found a promising alternative at Maxwell’s Creek but died of typhoid before closing the deal.Footnote 72 With few viable options, company directors continued the negotiations, coming to an agreement, in March 1853, with the mine’s proprietors, ‘French engineers of considerable experience’: Lacharme and Anthoine.Footnote 73

The QRM directors not only extolled the bright future of its new mines, but they also stressed that the purchase was made ‘on very advantageous terms’.Footnote 74 In reality, the company only subleased them, which satisfied the needs of both parties. Lacharme and Anthoine sought capital and equipment; QRM needed a mine. The company agreed to make the mine fully operational and pay Lacharme and Anthoine a 5 per cent commission on its net profits as well and US$8 per ton of ore extracted. With Schmitz gone, QRM also hired the French ‘engineers’ to manage its operations for an annual salary of US$4,000 each and reimbursed Lacharme for the infrastructure he had already constructed.Footnote 75

Making the mines operational took longer and cost more than the company anticipated. By the time the mill was ready in February 1854, QRM had run out of cash and owed local suppliers £6,511 (about US$31,700). Furthermore, the mining operation revealed glaring inefficiencies: while the stamp mill could pulverize 60 tons of ore per day, Lacharme’s gold-washing machine ‘proved virtually worthless in practice’.Footnote 76 Although shareholders initially agreed to cover the company’s shortfall, its revenue failed to keep up with expenses. Like many free-standing companies that invested in California mining, QRM underestimated the capital needs of hard-rock mining. This kind of mismanagement plagued free-standing companies. Designed to provide a reputable legal structure to channel metropolitan capital to overseas investment opportunities, these companies typically subcontracted outside expertise to maintain low-cost management structures. But the combination of limited information and the lack of experience was often fatal.Footnote 77 Lacharme kept the company’s creditors at bay by borrowing US$74,000 from Touchard of V. Marizou et Compagnie. Yet once shareholders baulked at the recurring calls for additional funds—the result of false expectations and reports of poor-quality ore—QRM dissipated. By the time Touchard sued the company and Lacharme for US$103,000 (debts plus interest) in June 1856 it was too late.Footnote 78

While V. Marizou et Compagnie and QRM shareholders lost their investments, Lacharme and Anthoine seemingly machinated a profitable outcome from their California adventure. QRM had reimbursed Lacharme for his initial investments (US$70,759), and presumably paid him and Anthoine at least some of their salaries and mining royalties. After all, the pair managed the company’s California operations, something that the QRM directors—who eventually complained about their ‘chicanery’—probably regretted.Footnote 79 They also left for Paris in 1855 with a ‘valuable’ collection of ‘bizarrely-contorted’ gold nuggets to display in the 1855 Universal Exhibition.Footnote 80 By that time, the pair were likely planning their next endeavour back along the Sinú River. This is suggested by Anthoine’s decision to describe his latex-processing experiments before the Société impériale et centrale d’agriculture, later published in Revue colonial.Footnote 81 The way French authorities classified his rubber almost a decade earlier was no longer of much concern. Instead, the account was a way to circulate his name within ‘progressive’ scientific circles and bolster his commercial credentials. This fusion of science and commerce—as well as recycling European investment in the California gold rush—was central to their subsequent frontier endeavours.

From the Sinú to the Darien

By 1856, Anthoine and Lacharme were back in Colombia where they acquired various properties, including more than 20,000 hectares of public lands along the Sinú River, south of Montería.Footnote 82 Initially they exported forest products, such as mahogany. But as global cotton prices spiked during the US Civil War, they engaged peasants to grow the crop on the far edge of the agrarian frontier. Lacharme, who enjoyed rural life, managed the cotton farm. Enthralled by the ‘vegetable wealth of the land’, he spent more time at his rural property, and in the forests of the Sinú, than at his house in Montería.Footnote 83 By contrast, Anthoine, who was then forty-seven, preferred to remain in contact with metropolitan networks from the relative comfort of Cartagena. The resource that most interested him was not high-value tropical products but paper pulp. He sought to convert two marketless raw materials—a heliconia (Heleconia mariae) and the bongo tree (Cavanillesia platanifolia)—that grew abundantly on his property along Ciénaga de Betancí (a large wetland) into a profitable export.

The heliconia was Anthoine’s entry into global botanical networks. Anthoine sent a description of the plants to Peter Le Neve Foster, secretary of the Royal Society of Arts, Britain’s long-standing ‘national improvement agency’, seeking paper-manufacturing contacts.Footnote 84 Foster forwarded his letter to Joseph D. Hooker, then assistant director of Kew Gardens. Hooker, who plied far-flung correspondents for botanical information, asked Anthoine for additional descriptions and physical samples of the heliconia.Footnote 85 While Hooker gave Anthoine the honours of naming the new species, what really interested the French entrepreneur were commercial contacts.Footnote 86 ‘As science and commerce are so intimately connected’, he wrote, Hooker could surely help him contact a ‘great paper manufacturer’.Footnote 87 These connections were real: the global flow of botanical information, directed by metropolitan ‘control centers’ like Kew Gardens, ‘was of great commercial importance’.Footnote 88 But to Hooker, who prided himself a man of science (which still retained airs of a gentlemanly vocation rather than paid profession), Anthoine’s request might have appeared too crass, for no connections were forthcoming.Footnote 89 By the time Anthoine told Hooker about the Société civile forestière du Sinu, founded in November 1863 to develop his paper-pulp business, he was already planning his next venture: an interoceanic canal.Footnote 90

The long-held dream of connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans gathered renewed attention in the wake of the California gold rush. Geopolitics played an even larger role. After the United States became a transcontinental power at Mexico’s expense, ‘the question as to the best mode of communication’ between the two coasts was ‘render[ed] exceedingly important’.Footnote 91 The completion of the transcontinental railway in 1869 partially resolved this issue, but the US Navy still desired a canal, as did various European nations. The French, for instance, imagined a canal would bolster their imperial (and anti-American) ambitions in Latin America, exemplified by their foray into Mexico from 1861 to 1867, and in the Pacific.Footnote 92 Nonetheless, the most appropriate route remained hotly debated. For some, including Anthoine, the most promising passage likely lay hidden within the little-known and inhospitable Darien. Yet just happening across a viable route—as the Irish physician and Royal Geographical Society fellow, Edward Cullen, claimed to have done in 1849—was unlikely. So Anthoine first sought evidence of a natural connection that, he surmised, Spanish colonial officials had kept hidden. To gain access to Spain’s colonial archives, Anthoine travelled to Madrid in 1862 with a sizeable gift for Queen Isabel II: a 15-metre dugout canoe from the Sinú.Footnote 93

The French entrepreneur also arrived under the guise of an altered identity: André-Anthoine de Gogorza. In Spain, he adopted the surname of his Venezuelan ‘wife’. While he did so at the request of her family, he wrote to Hooker, it may have been a strategy to conceal the fact that they were not legally married.Footnote 94 (Anthoine had abandoned his first wife in France, where divorce remained illegal). This metamorphosis was facilitated by the malleability of his name—Anthony, Antonio, André, Andrew—which de Gogorza (henceforth I will use his adopted surname) manipulated to strategically shift his national identity: French, Colombian, American (naturalized through his father, who spent several years in New York City in the 1790s). In an era of rising nationalism, his shifting identities were also used to attack his credibility. Not only was he accused of being an American spy (seeking to discredit Lucien de Puydt’s canal route), but of being a fictitious American (‘he had himself naturalized’) and hiding his real identity (‘he disguises his real name behind the Spanish pseudonym of Antonio de G***, which he has no right to use’).Footnote 95 Rummaging through the archives, de Gogorza claimed to have found ample evidence—colonial surveys, pirate attacks, Indian trails—of a near sea-level path through the Darien. To help finance an expedition to confirm this route, de Gogorza travelled to New York City in 1865 to sell his Betancí business.

Although cotton prices were poised to fall at the end of the US Civil War, de Gogorza managed to enthral several Yankee businessmen. The tropics still enchanted the American public, which had turned out in droves to view the ‘transcendent glory’ of Frederic Church’s landscape painting, ‘The Heart of the Andes’, and its portrayal of an undeveloped but promising continent.Footnote 96 The leading force of what became the Intertropical Company, which purchased de Gogorza’s land and paper-making patent, was Lorenzo Dow. An ex-gold prospector and Kansas Supreme Court justice, Dow had made a small fortune selling munitions to the Union Army during the Civil War.Footnote 97 The other two directors were Linus Yale, Jr., of the Yale Mechanical Lock Company, and Charles Puffer, a Reconstruction-era plantation owner. Henry Winn, Yale’s son-in-law, was the company’s secretary, and Oscar Ireland, who befriended Lacharme, kept the books in Montería.Footnote 98 Although economic historians have noted how demand for cotton during the US Civil War reconfigured global supply chains, few have traced the way wartime accumulation fuelled foreign investment in places like Colombia. While Intertropical continued to grow cotton, its main prospects were forest products—mahogany, rubber, fustic dye—and operating a steamboat on the Sinú River. Ireland dismissed Dow’s ‘rose-colored’ promises, but still thought his own prospects were ‘fair if not magnificent’.Footnote 99 However, within three years the company folded. While the fleeting nature of such speculative ventures has caused them to be overlooked (in favour of foreign merchants), cumulatively they played a significant role fomenting outside ties to Latin America.Footnote 100 (They also buried a fair amount of capital in the tropics.) For de Gogorza, the sale of his Betancí property enabled him to finance an exploratory survey of his Darien route at the end of 1865.

For this task, de Gogorza turned to his old partner, Lacharme, who was adept at moving through the forests of the Sinú. He also perked the interest of the Compagnie générale transatlantique (CGT), the shipping company founded in 1855 by Émile and Isaac Pereire, the Saint-Simonian industrialists and founders of Crédit Mobilier, the investment bank instrumental in Hausmann’s transformation of Paris.Footnote 101 In 1860, CGT took over the French government’s lucrative mail contract between France and the Americas, including the Panamanian port of Colón, from V. Marizou et Compagnie. With close ties to de Lesseps and an appetite for large infrastructure projects, it’s not surprising that the Pereire brothers would send Jules Flachat, the chief civil engineer on the French island of Guadeloupe and son of Saint-Simonian railway developer and CGT board member, Eugène Flachat, to help de Gogorza survey his proposed canal route. However, upon Flachat’s arrival in Panama in mid-November 1865, he organized his own expedition rather than wait for Lacharme, who did not receive an invitation until 21 December. De Gogorza was livid, considering Flachat’s actions to be an ‘usurpation of his right to the discovery of the said pass’.Footnote 102 He also feared being excluded from the sale of the canal route, underscoring the speculative nature of such expeditions. In other words, the ‘business of exploration’ was not limited to publication of expedition narratives, as the field of critical exploration studies emphasizes. Instead, the expedition itself could be the business.Footnote 103

When Lacharme arrived in Colón, de Gogorza declined to accompany him to the wild headwaters of the Punusa, a tributary of the Tuyra River. This risk aversion gave Lacharme license to bypass the Punusa route after his guides said Flachat had found it unpromising. Lacharme had better luck on the Paya River, attributing his success to forest clues: the flight path of a black-bellied whistling duck (Dendrocygna autumnalis), which ‘never fly over high ground if they can proceed by way of valleys and water-courses among the hills’.Footnote 104 Given the questions of reliability or veracity that threatened the European project of exploration, institutions like the Royal Geographic Society tried to standardize the collection and presentation of expedition data.Footnote 105 Publishers also relied on a range of rhetorical devices to generate credibility. In this case, Lacharme deployed natural history to substantiate his ‘discovery’ of a low-lying pass. On 27 January 1866, his small party reached Tugulegua Creek, whose waters flowed into the Cacarica, a tributary of the Atrato River on the Caribbean side of the Darien. At an altitude of 58 metres, the pass was just under the 60 metres that French engineers had estimated to be the upper limit of a sea-level canal. ‘I have fulfilled my mission’, Lacharme wrote, ‘by discovering a passage … for the union of the two oceans’.Footnote 106

Promoting a canal

Since Flachat’s unfavourable report discouraged the Pereire brothers, de Gogorza turned to the United States for support. With Lacharme’s field notes in hand, he secured preliminary backing from a group of prominent New Englanders, including Frederick Billings, William Sprague, Oakes Ames, and Benjamin Butler. To resurvey his Paya route, the group of investors hired George Davidson of the United States Coast Survey. Yet fear of being duped—a common problem in such speculative ventures—made them nervous, and contract negotiations dragged on for the better part of 1866. So when Davidson fell ill upon reaching Colón in early 1867, their representative, John Spooner, decided to turn home. Latent fears about the Darien may have become all too real: the calamitous Strain expedition, in which six members died of starvation, was just over a decade old.Footnote 107 But Spooner’s long-standing suspicions reached the breaking point when he learned that de Gogorza had never actually set foot on the route he promoted.Footnote 108 Disillusioned, especially after the abortive launch of a second company with Nathaniel Banks, de Gogorza turned back towards Europe.Footnote 109

His proposal finally gained traction during the first international geography conference held in Antwerp in 1871. Congress organizers had posed a pressing question: what was the best canal route across Central America? Speaking on behalf of de Gogorza before a crowded audience, General Wilhem Heine (best-known for his lithographs of Commadore Perry’s Japan expedition) revealed the solution. Surprisingly, he first credited a nameless Indian.Footnote 110 While many explorers downplayed the critical role of local guides, de Gogorza relied on third parties—imaginary native inhabitants or colonial officials and their documents—to substantiate his claims: a process of recovery rather than discovery. To further corroborate Lacharme’s field notes, Heine claimed to have personally seen a gap in the costal range, in the area indicated by de Gogorza, while watching the sun set from the mouth of the Atrato River. That the ship’s captain as well as the mineralogist on the Selfridge expedition saw the same natural break added weight to his story.Footnote 111 The layers of eyewitness accounts were seductive. A couple of years after the opening of the Suez Canal, de Gogorza’s report of a natural passage through the spinal column of the Darien was, Le Pays reported, the most sensational news to come out of the congress.Footnote 112 Congress organizers formally thanked de Gogorza and recommended that the world’s great powers follow up his ‘interesting work and discoveries’.Footnote 113

One country to seriously study the question was the United States. For Ulysses S. Grant and others, an American-built canal was central to removing ‘all European flags from this continent’ and projecting US commercial power around the world.Footnote 114 At the end of the Civil War, the Senate instructed the Navy to prepare a report on all possible canal routes. The task fell to Rear-Admiral Charles H. Davis, who decided to first survey the Darien.Footnote 115 As a result, Lieutenant Selfridge spent several years in the field (1870–72), concluding, among other things, that de Gogorza’s route’s along the Paya River was ‘decidedly, unfavourable’: the elevation of Cacarica Pass was too high and the ‘broken country’ would require a ‘fatal’ amount of excavation.Footnote 116

De Gogorza objected that Selfridge, misled or delusional, surveyed the Cué River rather than his route.Footnote 117 The claim found echo and de Gogorza was invited to the second international geographical congress in Paris in 1875. There he insisted the Darien was composed of two distinct geological formations: the spinal column of Panama and an extension of the Andes. Where they met, a natural pass, with fossil evidence of having once been underwater, slunk through the mountains.Footnote 118 By contrast, Lucien de Puydt, whose own route along the Tanela River had been dismissed by Selfridge as ‘entirely impracticable’, countered that the Darien had a ‘uniform geologic formation’.Footnote 119 Given the conflicting opinions and the lack of solid evidence, Congress called for ‘further studies’.Footnote 120 De Lesseps agreed that it was premature to endorse any particular route; yet if forced to pick, he favoured the Darien.Footnote 121

General István Türr, a Hungarian revolutionary and aide-de-camp to the king of Italy, was also ‘struck by the logic’ of de Gogorza’s proposal.Footnote 122 By 22 January 1876, the pair had formed a partnership. De Gogorza would obtain a concession to build a canal across the Darien, and Türr would raise the capital to resurvey de Gogorza’s route and make the initial designs of a sea-level canal, the only kind de Lesseps would accept.Footnote 123 On 19 August, Türr formed the Société civile internationale du canal interocéanique du Darién with his brother-in-law, Lucien Napoleon Bonaparte Wyse, grandson of Napoleon’s younger brother, Lucien. Investors included prominent figures in French society, many with Saint-Simonian roots.Footnote 124 Wyse, an officer in the French Navy, was to lead the Darien expedition. Should de Gogorza’s route prove viable, both the preliminary plans and concession would be sold to a company created—presumably by de Lesseps—to build the canal.

De Lesseps did not appear publicly involved in Türr’s company, but his hand was visible behind the scenes. De Gogorza obtained a concession specifically for a sea-level canal because de Lesseps had insisted upon a canal without locks.Footnote 125 Türr’s exploration company sought de Lesseps’s approval before issuing its instructions to Wyse and kept him abreast of its progress.Footnote 126 In March 1876, the Commission de géographie commerciale de Paris appointed de Lesseps to head the committee charged with organizing the 1879 canal congress.Footnote 127 It hoped that, by creating an ‘international jury’ of experts to determine the best canal route, this congress would spur the necessary geographical studies to support such a decision.Footnote 128 But de Lesseps and other backers of Türr’s Darien project also used the canal congress to parry the conclusion of the Interoceanic Canal Commission, formed by President Grant, that Nicaragua offered the most advantageous route.Footnote 129 Why not, they suggested, let an international, objective forum decide this pressing global matter?

Wyse’s exploration party departed from Saint-Nazaire on 7 November 1876 to take advantage of the Darien’s dry season. Naval officer Armand Reclus was second-in-command. There were seven engineers of various nationalities—French, English, Italian, Austro-Hungarian, Colombian—as stipulated by the terms of the concession. Wyse also asked Lacharme to join them. By January, their initial optimism began to fade. Although the initial elevation measurements along the Tuyra River were lower than expected, the upper Paya River ascended with ‘angry rapidity’.Footnote 130 While Lacharme’s pass was too high for a sea-level canal, Wyse proposed a tunnel. De Lesseps rejected the design and sent Wyse back to finish surveying an alternative line along the Tupisa and Tiati (Guati) rivers.Footnote 131

The second expedition departed in November 1877. Lacharme and Louis Verbrugghe, an old friend of Wyse, joined them in Panama. By the end of February, the expedition concluded that the Tupisa–Tiati route also required a tunnel, dashing the dreams of finding a sea-level pass through the Darien.Footnote 132 Following de Lesseps’s advice, Wyse sent Reclus to examine the only plausible alternative: the Panama Railroad line.Footnote 133 This route, however, lay outside the concession granted to de Gogorza and Türr. Wyse, therefore, had to race to Bogotá to discuss modifying its terms with Colombia’s outgoing president, Aquileo Parra. Because of low water in the Magdalena River, Colombia’s main transportation artery, Wyse sailed to the Pacific port of Buenaventura and traversed the mountainous country by horse, spending, according to his own account, up to twenty-two hours a day in the saddle.Footnote 134 The publishers of exploration narratives loved, and helped conjure, this sort of drama.Footnote 135 Likely, Türr and his board were also on edge since their investment depended on Wyse’s timely arrival and successful negotiations.

The bet paid off. On 28 May, Parra’s successor, Julián Trujillo authorized Türr’s company to build an interoceanic canal anywhere in Colombian territory. The one exception remained inside the concession already granted to the Panama Railroad Company. To build there, Türr and associates would have to negotiate directly with the American-owned enterprise. In February 1879, Wyse travelled to New York to begin such talks. Although he claimed some leverage by suggesting that a Darien route remained viable, Trenor Park and the other railroad owners held a better hand: they agreed to sell the company for twice its market value.Footnote 136 With the international canal congress scheduled to open on 15 May, Wyse had little choice.

The International Canal Congress

In an era enthralled by large public-works projects, this canal forum was a grand affair. Led by de Lesseps, the congress convened almost 140 experts from around the world (though half were French) to study the canal question. Its most important task was to site the canal based on the best available geographic surveys and engineering studies. Fourteen projects were submitted. De Gogorza, now tied to Türr’s company, did not propose his Darien route. By contrast, Lacharme had sailed to France to propose flooding the Tuyra River Basin to connect the Paya and Cacarica rivers via a canal with locks rather than Wyse’s tunnel design. He likely knew his scheme was a long shot; but the recognition of participating in such an historic congress was a decent consolation prize. Unfortunately, Lacharme died in Paris on 6 October 1878. Years of living in the lowland tropics had likely taken their toll. De Gogorza posthumously submitted Lacharme’s proposal on 16 May 1879. The committee charged with examining canal routes agreed to consider the late entry. Perhaps it buttressed the overarching goal of objectivity. But the committee scoffed at Lacharme’s lowball cost estimate and perfunctorily rejected his proposal.Footnote 137

Under the veneer of impartiality, the Congress was beset by geopolitical tensions and entrepreneurial jockeying. Although de Lesseps positioned himself above the fray, he had already decided to build a canal through Central America. His main requirement was that it be a sea-level canal for the greater volume of traffic it promised. For this reason, Nicaragua did not interest him. Once the hopes for a Darien route fizzled, the only viable alternative was Panama. This is why de Lesseps needed the Congress to select the Wyse-Reclus proposal for a sea-level canal along the Panama Railway line. To the dismay of some, this is precisely what happened. The divisions among congressional participants did not neatly follow national fault lines. But Rear-Admiral Ammen of the US Navy contended that the deck was stacked: ‘the method of appointing “delegates”’ ensured de Lesseps could orchestrate the outcome.Footnote 138 After casting his own vote for Panama, de Lesseps announced, to a cheering audience, that he had already ‘accepted to place myself at the head of the enterprise’.Footnote 139 Less than two weeks later, de Lesseps reached an agreement with the board of Türr’s company to purchase its concession for 10 million francs (about US$1.9 million), half in cash and half in shares of his future canal-construction company, guaranteeing the shareholders of the Darien canal company a profit of more than 500 per cent.Footnote 140

This windfall pay-out likely incensed de Gogorza since he was no longer a beneficiary. From the moment Türr formed the exploration company, de Gogorza felt ‘ticklish’ about his position and rights of discovery.Footnote 141 He had received 150,000 francs (about US$32,000) to reimburse his accumulated expenses and labours. Yet with no seat on the board, de Gogorza may have felt his protagonism and control slipping away. He might also have harboured doubts about his ‘natural channel’—or was hard pressed for funds—since he sold his founder’s shares before any news of the expedition’s progress reached France.Footnote 142 Whatever the motive, de Gogorza underestimated de Lesseps’s commitment and financial profligacy. To claw back some of the ‘prize’ money, he sued Türr for failing to uphold the terms of their original partnership. De Gogorza sought 430,000 francs in damages: for being denied a leading role in the Wyse expedition; for failing to receive a seat on the board of de Lesseps’s new company; and for not equally participating in the profits of their venture.

The courts disagreed. Exploration required ‘men versed in the art’, the judges argued; participation could not be a predetermined right. Neither could Türr oblige de Lesseps to accept de Gogorza as a board member. And de Gogorza did not demonstrate that Türr had disproportionately benefited from the sale of the company. At issue here was 2.5 million francs (about US$477,000) reserved for the board to secretly disburse. But even if Türr had profited from this quasi-slush fund, the appeals court stated, de Gogorza had forfeited any legal claims by selling his founder’s shares. His consolation prize was purely ‘moral’: a ‘place’ among the ‘foremost promoters and founders of the interoceanic canal’.Footnote 143

De Gogorza tried to ensure this legacy by retracing, in the pages of the Journal of the American Geographic Society, his efforts and the evidence for a natural pass through the Darien. As de Lesseps’s canal project foundered in the late 1880s, de Gogorza hoped to revive American interest in his original Darien route: simply resurveying the Paya and Cacarica rivers would ‘prove that I have pointed out the only right place’ for a canal.Footnote 144 Of course, the Americans paid him no heed as they formally took over the French project in 1904 (after engineering the separation of Panama from Colombia the previous year), and completed construction by 1914. As narratives of the Panama Canal increasingly touted US exploits (or, subsequently, its imperialist temperament), de Gogorza’s pivotal role faded away. In Willis Johnson’s Four Centuries of the Panama Canal, published in 1906, he briefly appears as an ‘adventurer’ (misspelled as ‘Gorgoza’) who arrived in Bogotá as the agent of a French company.Footnote 145 An editor of the Bulletin of the American Geographical Society retorted that ‘The person of whom Mr. Johnson writes without knowledge was Mr. Anthony de Gogorza, who died … in Paris [in 1891]. He was a man of good family and of unblemished character; no more of an adventurer, to speak plainly, than Mr. Johnson himself.’Footnote 146 What stands out here is not the defence of character, but how quickly de Gogorza’s role in the story of the Panama Canal had faded from view.

Conclusions

It is not surprising that de Gogorza and Lacharme were quickly forgotten. As soon as the narrative shifted from exploration to canal construction, interest in the backstory withered. The Türr-Wyse partnership became a new moment of departure, relegating all previous expeditions to background noise. What’s missing, in this framing, is how Türr, Wyse, and ultimately de Lesseps first set their sights on the Darien. While the Panama Canal can seem overdetermined, it was by no means inevitable. The Americans could have broken ground in Nicaragua in the 1870s. Were it not for de Gogorza’s persistence, the discouraging conclusions of the Selfridge Expedition might have steered French attention toward, say, the Atrato–Naipipí route. De Lesseps’s growing commitment also mattered given the high cost of purchasing the Panama Railroad Company and its concession. In other words, de Gogorza and Lacharme played a vital role in the genesis of the canal by binding a constellation of French interests to the Darien and then Panama.

This is not just a story about the forgotten origins of the Panama Canal, however; it also uncovers overlooked connections behind Darien expeditions and the development of the Sinú Valley. It reveals, for instance, how the roots of the Panama Canal can be traced back to the forests around Montería. Lacharme’s extensive experience working in these forests facilitated his initial exploration of the Darien and made the route he found appear viable. It also earned him the admiration of his subsequent expedition companions. Wyse, Reclus, and Verbrugghe all marvelled at Lacharme’s capacity—and that of his ‘colossal’, ‘indefatigable’ men from Montería—to labour in the tropical forest.Footnote 147 To Wyse he was an ‘absolute necessity’, and the engineer Victor Celler was afraid to remain in the forest without him.Footnote 148 This status and his favourable impressions of the Sinú Valley, in turn, encouraged foreign investment there. In 1882, Louis Verbrugghe and his brother Georges acquired two properties (La Risa and Mosquito), next to Lacharme’s estate along the Sinú River, where they planted cacao and raised cattle. Wyse and possibly Türr later joined the venture, which helped spark the region’s growth.Footnote 149 In symmetrical fashion, then, the seeds that propelled the economic expansion of Montería had been planted in the forests of the Darien. While this is not a story of place, place plays a key role.

Personal ties to place and people also attracted other compatriots to the Sinú. In 1892, Fernand Vercken de Vreuschmen took charge of La Risa and Mosquito and, six years later, merged with the neighbouring cacao plantation founded by the Bordeaux wine merchant, Léonce Boiteau.Footnote 150 Vercken was related to de Gogorza through his half-sister, Marie-Elizabeth Pinçon. Around 1886 Paul Durand immigrated to the Sinú Valley to manage de Gogorza’s post-canal venture, La Colombie, a large property where he too planted cacao and tried to convert low-value tropical trees into paper pulp. Before Lacharme returned to France for the last time, he convinced his brother Gilbert, and family, to emigrate from the Morvan to Montería. This Franco-Belgian nucleus encouraged still further migrations, leading to a small French colony that promoted the region’s rapid growth as well as social tensions.Footnote 151 In other words, the economic development of the Sinú Valley owes much to the capital and people attracted by de Gogorza and Lacharme.

To recognize their dual legacy, we need to follow the pair as they moved back and forth between Europe, Colombia, the United States, and the Darien. This strategy is partly a function of my sources, which primarily just illuminate their activities in time and space. Yet, as Anne Gerritsen and Christian De Vito suggest, a micro-scale perspective encourages the construction of ‘categories, spatial units, and periodizations’ from within historical processes, and the ‘actions of historical subjects themselves’, rather than impose them from above.Footnote 152 Tracking de Gogorza and Lacharme through the places they inhabited—rather than restrict them to the predetermined spaces of European explorers or regional economic history—reveals one of the most salient aspect of their lives: the connections that other scholars have missed.

Tracing their lifepaths also draws attention to an overlooked figure of nineteenth-century global history: the speculator. In Jürgen Osterhammel’s magisterial overview of this period, for example, merchants abound but global speculators barely figure.Footnote 153 Yet speculators were critical for tethering metropolitan capital to far-flung opportunities. Overseas investments rose dramatically over the second half of the century.Footnote 154 The key instrument for foreign direct investment, especially in natural resources, was the free-standing company.Footnote 155 Sometimes existing concerns or company founders sought overseas investments themselves. More often, however, speculators pitched business opportunities to metropolitan investors (as de Gogorza did with Lorenzo Dow) or formed free-standing companies themselves (such as the mining concern of Lacharme et Compagnie). While a microhistorical perspective can help us recognize such figures, we also need macro-analytical approaches, as de Vries suggests, to develop a broader portrait of who they were and how they operated.Footnote 156 In this sense, I question the contention of De Vito and Gerritsen that micro and macro approaches to global history are ‘mutually exclusive’.Footnote 157

Studying speculative ventures can, moreover, refine the way we view the business of exploration. While historians have long acknowledged that explorers opened new areas for exploitation, they tended to focus on issues of physical endurance, moral rectitude, and the quest for knowledge rather than potentially crass commercial instincts.Footnote 158 Yet exploring uncharted regions was often a for-profit endeavour. Wyse, Reclus, and Verbrugghe all sought to capitalize on their Darien adventures by writing illustrated accounts for a popular audience. What the field of critical exploration studies misses, however, is the way that expeditions themselves could be considered business ventures rather than just the raw material for marketable narratives. The product that de Gogorza, as well as Türr and Wyse, wished to sell was a canal route. This required establishing its viability, a difficult endeavour that took de Gogorza over a decade. In a high-stakes field plagued by limited information and populated by charlatans, the production of trust was crucial. The techniques that de Gogorza and Lacharme deployed often drew inspiration from the world of exploration publishing. Yet one key difference stands out: how they depicted the Darien.

One of the common tropes used to frame the tropics was its exuberant vegetation. De Gogorza appealed to this characteristic to promote his Betancí business. His scheme relied on the natural abundance and low cost of producing paper pulp, made possible by the vigorous growth of tropical plants. This same exuberance, however, was potentially troublesome. All around the tropics, travellers complained about the oppressive heat, inclement weather, swarms of biting insects, disease, and a host of other dangers. In the Darien, these difficulties were compounded by the incessant toil of clearing trails through thick vegetation, fears of getting lost, and the threat of warlike Indians. These concerns were not simply imagined and indeed served to justify outside efforts to tame and transform the region.Footnote 159

As Mary Louise Pratt suggests more broadly, the discursive construction of Latin America as ‘primal nature’ functioned as a ‘sign of the failure of human enterprise’ and ‘legitimated European interventionism’.Footnote 160 Such depictions might help sell travellers’ accounts, but they could also scare off potential investors. In Lacharme’s account of his Darien expedition, we find a radically different portrait: travelling through the interior was easy; the country was salubrious and mosquito-free; and the Indians were friendly, God-loving, and helpful.Footnote 161 Lacharme’s narrative was just as embellished as the subsequent accounts by Wyse and others of slogging through the same terrain. This difference underscores their contrasting audiences and motives. In other words, paying attention to speculators, instead of just explorers and travellers, can recast the way Latin America, and other economic frontiers, were ‘sold’.

Financial support

None to declare.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Shawn Van Ausdal is an associate professor in the Department of History and Geography at the Universidad de los Andes, in Bogotá. He holds a PhD in Geography from the University of California, Berkeley. His work has focused primarily on the history of cattle ranching in Colombia and Latin America, bringing together the fields of agrarian, environmental, and business history.