Highlights

-

• No significant moral foreign language effect (MFLE) was found among Chinese-English bilinguals, challenging the robustness and generalizability of prior MFLE findings.

-

• Victim vulnerability emerged as a robust contextual factor, consistently increasing utilitarian choices across language contexts.

-

• The effect of victim vulnerability was moderated by emotional distress: it was stronger under low distress and weaker under high distress, revealing a nuanced emotional-contextual interaction.

1. Introduction

The foreign language effect (FLE), first introduced by Keysar et al. (Reference Keysar, Hayakawa and An2012), refers to the tendency of bilinguals to make different decisions when reasoning in a foreign language (FL) compared to their native language (NL). Since then, the FLE has been documented across multiple domains, including enhanced logical reasoning (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Zika, Rogers and Thierry2015), increased honesty (Bereby-Meyer et al., Reference Bereby-Meyer, Hayakawa, Shalvi, Corey, Costa and Keysar2020) and greater tolerance for egoistic lies (Xie et al., Reference Xie, Liao and Ni2025). Among these, the moral foreign language effect (MFLE), which refers to the increased likelihood of making utilitarian moral judgments in an FL, has received particular attention (Geipel et al., Reference Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Surian2015a). Most empirical investigations of the MFLE employ classical sacrificial dilemmas (e.g., the trolley dilemma) within questionnaire-based paradigms (Cipolletti et al., Reference Cipolletti, McFarlane and Weissglass2016; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Foucart, Hayakawa, Aparici, Apesteguia, Heafner and Keysar2014; Geipel et al., Reference Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Surian2015a; Privitera et al., Reference Privitera, Li, Zhou and Wang2023; Yavuz et al., Reference Yavuz, Küntay and Brouwer2024). Although many studies report robust MFLEs (e.g., Cipolletti et al., Reference Cipolletti, McFarlane and Weissglass2016; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Foucart, Hayakawa, Aparici, Apesteguia, Heafner and Keysar2014; Geipel et al., Reference Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Surian2015b), others find that the effect emerges only for specific dilemma types (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Gu, Ng and Tse2016; Del Maschio et al., Reference Del Maschio, Del Mauro, Bellini, Abutalebi and Sulpizio2022; Privitera et al., Reference Privitera, Li, Zhou and Wang2023) or fail to replicate it entirely (Białek et al., Reference Białek, Paruzel-Czachura and Gawronski2019; Čavar & Tytus, Reference Čavar and Tytus2018; Yavuz et al., Reference Yavuz, Küntay and Brouwer2024). These inconsistencies raise concerns about the generalizability of the MFLE and suggest that both methodological and psychological factors contribute to its variability.

A key methodological issue concerns the stimulus sets commonly used. First, the majority of MFLE studies employ one or two classical trolley-problem variants (Cipolletti et al., Reference Cipolletti, McFarlane and Weissglass2016; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Foucart, Hayakawa, Aparici, Apesteguia, Heafner and Keysar2014; Geipel et al., Reference Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Surian2015b; Privitera et al., Reference Privitera, Li, Zhou and Wang2023; Yavuz et al., Reference Yavuz, Küntay and Brouwer2024), which limits generalizability and risks confounding language effects with scenario-specific features (Del Maschio et al., Reference Del Maschio, Del Mauro, Bellini, Abutalebi and Sulpizio2022). Second, while some studies have attempted to broaden the stimulus set, they often fail to rigorously pretest materials for homogeneity (e.g., Brouwer, Reference Brouwer2021; Hayakawa et al., Reference Hayakawa, Tannenbaum, Costa, Corey and Keysar2017). Unvalidated but diverse dilemmas introduce inter-item variability, increasing statistical noise and potentially obscuring true effects. As a result, whether the MFLE reflects a genuine language effect or an artifact of stimulus selection remains unresolved.

Theoretical accounts of the MFLE have centered on dual-process theory (Greene et al., Reference Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley and Cohen2001, Reference Greene, Nystrom, Engell, Darley and Cohen2004), which posits that moral judgments arise from the interaction between automatic emotional processes (System 1) and controlled cognitive deliberation (System 2). System 2 involves effortful cost–benefit reasoning and relies on cognitive control to override intuitive emotional responses from System 1. Within this framework, the MFLE has been interpreted through two competing accounts: the “increased deliberation hypothesis” posits that using an FL enhances cognitive control, fostering utilitarian decisions (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Corey, Hayakawa, Aparici, Vives and Keysar2019; Stankovic et al., Reference Stankovic, Biedermann and Hamamura2022), whereas the “reduced emotion hypothesis” suggests that FL use weakens emotional engagement, reducing the influence of System 1 (Dewaele, Reference Dewaele2008; Harris, Reference Harris2004; Puntoni et al., Reference Puntoni, De Langhe and Van Osselaer2009). These accounts reflect the ongoing debate regarding whether the MFLE is fundamentally cognitive or emotionally driven.

Cognitive control, broadly defined as the ability to regulate thoughts and behaviors in line with goal-directed processes (Banich et al., Reference Banich, Mackiewicz, Depue, Whitmer, Miller and Heller2009; Miyake et al., Reference Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, Howerter and Wager2000), has long been considered a plausible mechanism underlying the MFLE (Hayakawa et al., Reference Hayakawa, Tannenbaum, Costa, Corey and Keysar2017; Keysar et al., Reference Keysar, Hayakawa and An2012). However, empirical studies that directly measure individual differences in cognitive control remain scarce and rely predominantly on single offline measures conceptualized as trait-level indicators. Privitera (Reference Privitera2024), for example, used the Simon task and found that higher cognitive control predicted more utilitarian responding in an FL, though the effect was limited to specific dilemmas. Given that the Simon task primarily assesses spatial rather than linguistic conflict, it may not fully capture the domain-specific control processes engaged during language-based moral reasoning (Hilchey & Klein, Reference Hilchey and Klein2011).

Emotional distress constitutes a second key factor. Within dual-process theory, heightened distress may shift the balance toward intuitive, emotional reactions at the expense of controlled deliberation, thereby influencing moral outcomes (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Gu, Ng and Tse2016; Muda et al., Reference Muda, Niszczota, Białek and Conway2018). Although some studies report reduced distress when reasoning in an FL (Geipel et al., Reference Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Surian2015a), its moderating role in the MFLE is inconsistent, reflecting the complex interplay between language and emotion. Language proficiency is another frequently discussed moderator (Del Maschio et al., Reference Del Maschio, Del Mauro, Bellini, Abutalebi and Sulpizio2022; Privitera et al., Reference Privitera, Li, Zhou and Wang2023), though a recent meta-analysis found it does not significantly influence the MFLE (Circi et al., Reference Circi, Gatti, Russo and Vecchi2021). Consequently, controlling for proficiency allows researchers to isolate core cognitive and emotional mechanisms of interest more effectively.

Compared to individual-level differences, contextual features of moral dilemmas have received relatively little attention. Prior research has examined the influence of personal force (Geipel et al., Reference Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Surian2015a; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley and Cohen2001; Privitera et al., Reference Privitera, Li, Zhou and Wang2023), intentionality (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Flexas, Calabrese, Gut and Gomila2014; Privitera et al., Reference Privitera, Li, Zhou and Wang2023) and protagonist identity (Lunsford, Reference Lunsford2000; Qi et al., Reference Qi, Li and Du2018; Yavuz et al., Reference Yavuz, Küntay and Brouwer2024) on MFLE. However, one key but understudied variable is victim vulnerability: the perceived fragility of the potential harm recipient. Yavuz et al. (Reference Yavuz, Küntay and Brouwer2024) noted that harmful acts toward elderly victims are judged more harshly, presumably due to their vulnerability compared to adults, yet no study has systematically manipulated this variable across multiple dilemmas in the MFLE context. Construal Level Theory (CLT; Trope & Liberman, Reference Trope and Liberman2010) offers a useful theoretical framework for understanding how victim vulnerability shapes moral judgments by linking social perception to mental representation. CLT posits that an event’s perceived psychological distance, including social, spatial and temporal dimensions, determines its level of mental construal. Psychologically distant events are represented abstractly and schematically (a high-level construal), whereas psychologically close events are represented with rich, concrete detail (a low-level construal). From this perspective, a highly vulnerable victim is likely to reduce perceived psychological distance by eliciting a sense of protective responsibility (Haidt & Joseph, Reference Haidt and Joseph2007), thereby promoting low-level construal and suppressing utilitarian choices. Therefore, examining victim vulnerability is not merely filling a current gap; it is essential for testing the boundary conditions of the MFLE through the lens of psychological distance.

Despite its theoretical importance, the role of victim vulnerability on moral judgment remains relatively underexplored, and existing findings are inconsistent. On one hand, high vulnerability often elicits protective moral responses across age groups. For example, children preferentially protect victims with physical or psychological disadvantages (Findlay et al., Reference Findlay, Girardi and Coplan2006; Nucci et al., Reference Nucci, Turiel and Roded2018), and adults show stronger condemnation for harmful acts toward elderly or female victims, groups commonly perceived as vulnerable (Barreto et al., Reference Barreto, Ryan, Schmitt, Barreto, Ryan and Schmitt2009; Chu & Grühn, Reference Chu and Grühn2018; Kite et al., Reference Kite, Stockdale, Whitley and Johnson2005). On the other hand, this protective instinct is not absolute and can even be reversed under certain circumstances. For instance, Yoo and Smetana (Reference Yoo and Smetana2019) reported that children may justify harm to vulnerable victims more than to typical ones in contexts involving psychological harm. These mixed findings indicate that the influence of vulnerability on moral judgment is highly context dependent. This contextual sensitivity is also evident in classic moral dilemmas, which vary considerably in how they frame vulnerability. For example, the Euthanasia scenario (i.e., a trapped, severely injured soldier vulnerable to enemy capture and torture; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley and Cohen2001) emphasizes physical vulnerability, whereas Sophie’s Choice (i.e., a mother choosing which of her two children will undergo fatal experimentation; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Nystrom, Engell, Darley and Cohen2004) lacks such framing. These inconsistencies in both empirical findings and stimuli highlight the need for a more systematic investigation of victim vulnerability.

Beyond descriptive effects, the specific psychological mechanisms underlying vulnerability effect remain largely unexamined. The interplay between emotion and cognition appears particularly critical. Although direct evidence linking emotional distress to victim vulnerability is scarce, prior research suggests that distress significantly influences responses to other victim characteristics. For example, identifiable victims evoke stronger emotional distress and higher helping intentions (Kogut & Ritov, Reference Kogut and Ritov2005), and moral condemnation is heightened when victims belong to socially recognized vulnerable groups (Chu & Grühn, Reference Chu and Grühn2018).

Building on these findings, we propose that victim vulnerability exerts its influence through two primary emotional pathways: empathic concern (an other-oriented affective response aimed at alleviating others’ suffering; Batson et al., Reference Batson, Batson, Slingsby, Harrell, Peekna and Todd1991) and protective moral norms (safeguarding those perceived as fragile; Haidt & Joseph, Reference Haidt and Joseph2007). From the perspective of dual-process theory (Greene et al., Reference Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley and Cohen2001, Reference Greene, Nystrom, Engell, Darley and Cohen2004), heightened vulnerability is expected to intensify emotional responses, thereby suppressing the deliberative system and reducing utilitarian tendencies. Importantly, the magnitude of this effect is likely to vary across individuals depending on their emotional susceptibility and cognitive control. Individuals high in emotional susceptibility may be more strongly affected by the distress elicited by a vulnerable victim, leading to more deontological judgments, whereas those with stronger cognitive control may more effectively regulate emotional interference, facilitating utilitarian choices. However, this account alone cannot explain paradoxical findings in which high vulnerability leads to increased utilitarian responding (Yoo & Smetana, Reference Yoo and Smetana2019). To reconcile these inconsistencies, we propose an additional mechanism rooted in threat and defensive processes (e.g., Correia et al., Reference Correia, Alves, Sutton, Ramos, Gouveia-Pereira and Vala2012): when emotional arousal exceeds an individual’s tolerance threshold, it may activate defensive emotional distancing, prompting a shift toward more calculative, utilitarian reasoning. Thus, whether victim vulnerability reliably promotes deontological judgments or, under certain conditions, enhances utilitarian responding remains an unresolved empirical question. Addressing this question requires examining how vulnerability interacts with emotional distress and cognitive control, two key individual-level factors central to bilingual moral cognition.

Against this background, the present study sets out to achieve two primary objectives. First, we provide a more rigorous and generalizable test of the MFLE by employing a diverse yet methodologically homogenized set of 14 moral dilemmas. Second, we investigate the boundary conditions of the MFLE by examining how victim vulnerability interacts with individual differences in cognitive control and emotional distress. Specifically, we address three research questions: (1) Is the MFLE robust across a well-validated set of 14 moral dilemmas? (2) Does victim vulnerability modulate the MFLE? (3) How do cognitive control and emotional distress moderate the effects of language and victim vulnerability on moral judgments, respectively? Based on the literature reviewed above, four hypotheses were formulated. First, we predicted a main effect of Language, expecting to replicate the MFLE such that participants would make more utilitarian judgments in the foreign than in the native language. Second, we expected a main effect of Victim Vulnerability, with fewer utilitarian responses in high-vulnerability scenarios. Third, we hypothesized that victim vulnerability would moderate the language effect, such that the MFLE is expected to be amplified under conditions of high victim vulnerability. Finally, we hypothesized moderation by individual differences: higher cognitive control and lower emotional distress were expected to strengthen the MFLE, whereas higher emotional distress and weaker cognitive control were expected to reduce utilitarian responding, particularly in high-vulnerability dilemmas.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

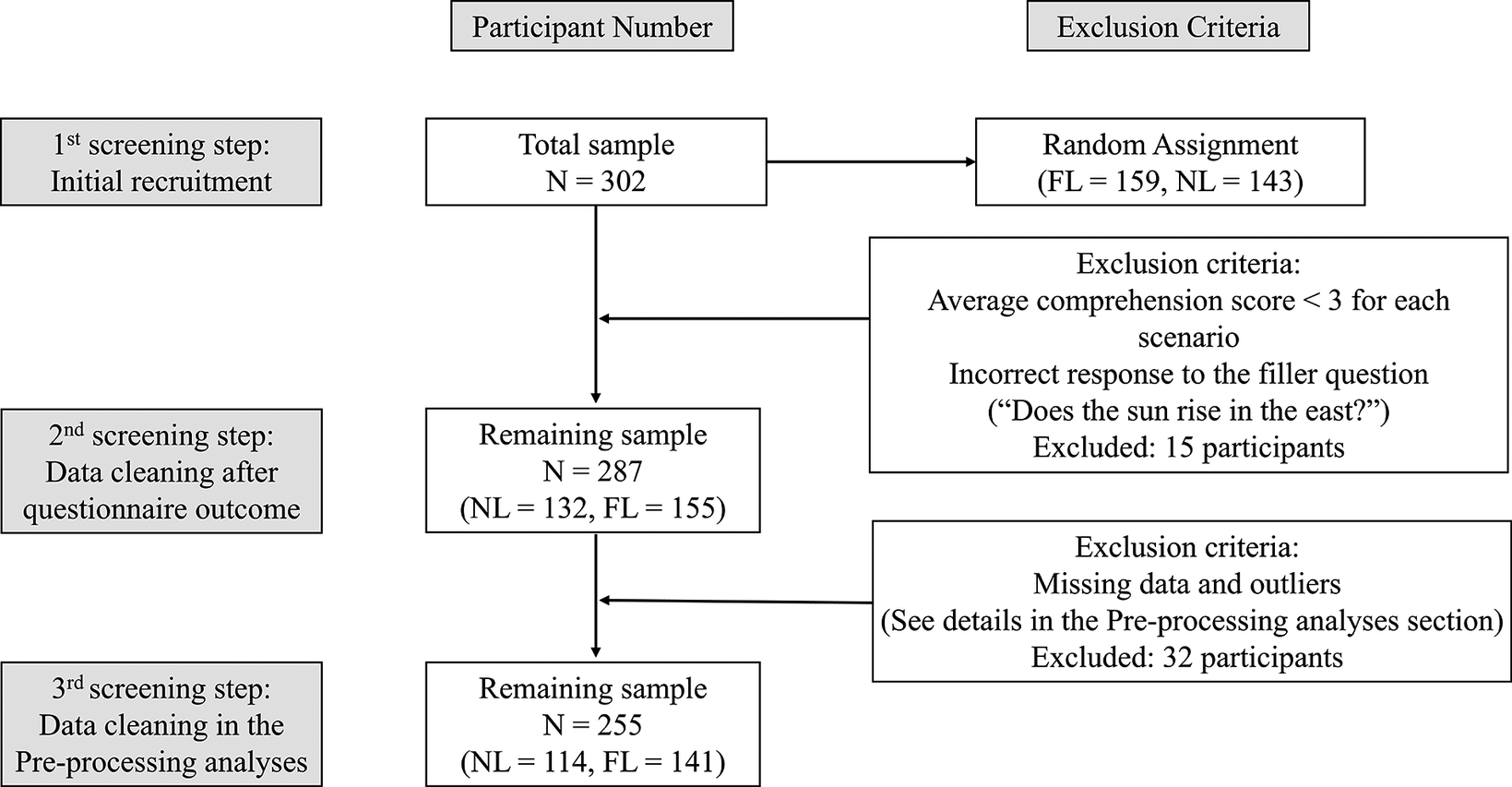

To evaluate the statistical power for detecting the hypothesized effects, a power analysis was conducted based on data from the first 20 pilot participants (Brysbaert, Reference Brysbaert2019). The analysis was performed using the mixedpower function (Kumle et al., Reference Kumle, Võ and Draschkow2021) in R (R Development Core Team, 2020). Power estimates were calculated across several hypothetical sample sizes (N = 150, 200, 250, 300), using a conventional significance threshold of t = 2. Pilot results indicated that with N = 200, the estimated power was 81.5% for the language effect and nearly 100% for both the vulnerability main effect and the Language × Vulnerability interaction. These findings suggested that a minimum sample size of 200 would yield adequate statistical power for detecting the effects of interest. In view of the potential data loss during preprocessing and the variability typically observed in MFLE, we recruited 302 Chinese–English bilinguals from several universities in China. After applying exclusion criteria, the final sample comprised 255 participants, meeting the power requirements established in the pilot analysis (see Figure 1 for exclusion criteria and Table 1 for participants’ details).

Figure 1. Flow chart of participants trimming procedure.

Table 1. Participants’ details on demographic information and language background

Note: p-values were calculated using chi-square tests for gender (female percentage) and Welch’s t-tests for all other demographic variables.

2.2. Design and materials

The experiment employed a 2 (Language: Chinese versus English) × 2 (Victim vulnerability: high versus low) mixed-factorial design, with Language as a between-subjects factor and Victim Vulnerability as a within-subjects factor. Individual differences in cognitive control and emotional distress were also measured to further analyze their moderating effects.

The moral dilemmas were selected through a rigorous dual-criterion pretesting procedure to ensure their suitability for eliciting the MFLE. Consistent with prior work (e.g., Hayakawa et al., Reference Hayakawa, Tannenbaum, Costa, Corey and Keysar2017; Muda et al., Reference Muda, Niszczota, Białek and Conway2018), the materials needed to be (a) emotionally engaging and (b) high in internal conflict. Following established procedures (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Feng and Zhang2023; Yin et al., Reference Yin, Guan, Hua and Zhang2018), we adapted previous framework to two 7-point scales assessing internal conflict and emotional state, and applied them to 26 well-established dilemmas (e.g., Baron, Reference Baron1998; Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Flexas, Calabrese, Gut and Gomila2014; Conway & Gawronski, Reference Conway and Gawronski2013; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley and Cohen2001, Reference Greene, Nystrom, Engell, Darley and Cohen2004; Hayakawa et al., Reference Hayakawa, Tannenbaum, Costa, Corey and Keysar2017; Lotto et al., Reference Lotto, Manfrinati and Sarlo2014). Twenty-eight participants (10 male; M age = 24.46, SD = 2.08), none of whom took part in the main experiment, rated each scenario. Internal conflict was rated from 1 (no conflict) to 7 (extremely high conflict), with 4 indicating moderate conflict. Emotional state was rated on a bipolar scale from 1 (extremely negative) to 7 (extremely positive), with 4 as neutral. Scenarios were retained only if they received emotional state ratings below the midpoint (<4) and internal conflict ratings above the midpoint (>4). This ensured that the final set of materials was homogeneous in being both emotionally negative and sufficiently conflict-inducing, a necessary condition for eliciting the MFLE. To further enhance cultural and ecological validity, two experts evaluated the cultural appropriateness of each scenario based on the guidelines proposed by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Feng and Zhang2023). Place names and culturally specific details were localized accordingly. Full pretest data and all stimuli are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

After screening, 14 selected dilemmas were subsequently categorized according to the key within-subjects manipulation: victim vulnerability. Vulnerability was operationalized through systematic narrative adjustments highlighting the victim’s physical fragility. In the high-vulnerability condition, victims were described using cues indicating compromised physical condition, such as severe injury, poor health, or limited likelihood of self-protection (e.g., “a severely injured passenger”). In the low-vulnerability condition, these cues were removed so that the victim appeared physically capable and not particularly fragile. These narrative modifications guided participants’ perceptions of the victim’s susceptibility to harm without altering the core structure of the dilemmas. To validate this categorization, we employed a two-step procedure. First, two independent psychology experts classified all scenarios as high or low in vulnerability; their classifications were fully consistent with our manipulation criteria. Second, an independent sample of 21 participants (12 male; M age = 24.62, SD = 2.64), who had participated in neither the previous pretest nor the main experiment, was asked to rate perceived victim vulnerability on a 7-point scale from 1 (completely not vulnerable) to 7 (extremely vulnerable). A paired-samples t-test confirmed that high-vulnerability scenarios (M = 5.00, SD = 1.29) were rated as significantly more vulnerable than low-vulnerability scenarios (M = 3.65, SD = 1.22) (t (20) = 2.786, p = .011, Cohen’s d = 0.608).

The finalized set of 14 dilemmas shared several critical features. First, all were empirically validated to be high in internal conflict and to elicit negative affect, ensuring a consistent baseline of moral engagement. Second, the two validated sets differed systematically in victim vulnerability. Third, all scenarios were sacrificial dilemmas requiring trade-offs between harming one individual and saving more people (Kahane et al., Reference Kahane, Everett, Earp, Caviola, Faber, Crockett and Savulescu2018), thereby reliably activating emotional distress. To reduce fatigue while preserving moral tension (Cecchetto et al., Reference Cecchetto, Rumiati and Parma2017), all dilemmas were edited for conciseness without altering their ethical structure. Despite structural parallels, the scenarios varied in content (e.g., Burning Building, Car Accident, etc.), providing a range of contexts for examining our research questions. Last but not least, all English dilemmas were translated into Chinese by two bilingual linguists, and subsequently back-translated by an independent translator to ensure semantic and emotional equivalence. We additionally conducted a structural comparison of the final English and Chinese versions. A paired-samples t-test revealed identical sentence counts across versions (English: M = 3.57, SD = 0.85; Chinese: M = 3.57, SD = 0.85); t (13) = 0.00, p = 1.00), indicating that the narratives were structurally comparable across languages, minimizing potential confounds related to complexity and length.

Overall, the final stimulus set consisted of 28 target dilemmas (14 Chinese, 14 English; see Table 2 for examples), interspersed with six filler trials containing low-conflict or non-moral content (Greene et al., Reference Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley and Cohen2001, Reference Greene, Morelli, Lowenberg, Nystrom and Cohen2008; Unger, Reference Unger1996) to reduce response biases and prevent habituation. All materials were presented in pseudo-randomized order to control for order effects. An attention-check item was embedded to ensure valid responding (see Supplementary Materials for details).

Table 2. Examples in each experimental condition

Note: Text indicating vulnerability of the potential victim is displayed in bold.

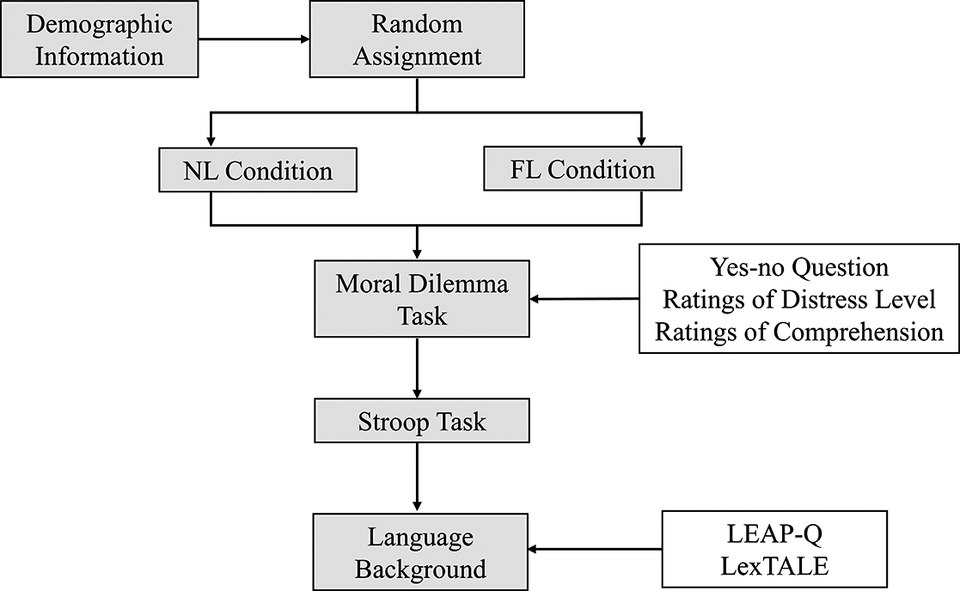

2.3. Procedure

The experiment was conducted in a sound-attenuated, well-lit room to minimize distractions, and all tasks were completed individually on computers. All questionnaire-based components, including demographic information, the moral dilemma task and the language proficiency measures, were administered via the professional online survey platform Wenjuanxing (https://www.wjx.cn). The Stroop task, however, was administered through an online cognitive assessment program coded in JavaScript, which automatically recorded behavioral data. Figure 2 provides an overview of the experimental procedure. After providing demographic information, participants were randomly assigned to either the NL or FL condition. The experiment began with the moral dilemma task. Participants read 14 distinct moral scenarios, each followed by a binary (yes/no) decision question (Hayakawa et al., Reference Hayakawa, Tannenbaum, Costa, Corey and Keysar2017). Following each dilemma, participants rated both the emotional distress elicited by the scenario and their comprehension of the narrative, using a 7-point Likert scale. The distress rating, adapted from Del Maschio et al. (Reference Del Maschio, Del Mauro, Bellini, Abutalebi and Sulpizio2022) and Privitera et al. (Reference Privitera, Li, Zhou and Wang2023), captured participants’ subjective experience of internal conflict and emotional discomfort (1 = “completely not distressing”; 7 = “extremely distressing”). Comprehension ratings assessed how well participants understood the scenario (1 = “not understandable at all”; 7 = “completely understandable”). The response sequence (yes/no decision, distress rating, comprehension rating) was held constant across all trials.

Figure 2. Flow chart of experiment procedure.

After completing the moral dilemma task, participants performed a classic color-word Stroop task to measure cognitive control. Because the Stroop task inherently engages linguistic representations, it may activate language-related knowledge (Ness et al., Reference Ness, Langlois, Kim and Novick2023) and provides a more direct index of bilinguals’ control processes relevant to language switching (Hilchey & Klein, Reference Hilchey and Klein2011). These features make it particularly well suited for the objectives of the present study. In this task, Chinese color words were displayed in font colors that were either congruent, incongruent or neutral relative to the word’s meaning. The task comprised 84 trials evenly distributed across three conditions: (1) Congruent: word meaning and font color matched (e.g., “红” [red] in red font); (2) Incongruent: word meaning and font color conflicted (e.g., “蓝” [blue] in red font) and (3) Control: a colored rectangle appeared without text. Participants were instructed to respond as quickly and accurately as possible to the font color. Cognitive control was operationalized via the Stroop interference effect, calculated as the response time difference between incongruent and control trials (Bub et al., Reference Bub, Masson and Lalonde2006; Goldfarb & Henik, Reference Goldfarb and Henik2007), with larger interference values indicating lower cognitive control capacity.

The session concluded with assessments of language proficiency. Subjective proficiency was measured using the Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q; Marian et al., Reference Marian, Blumenfeld and Kaushanskaya2007), while objective proficiency was evaluated using the LexTALE test (Lemhöfer & Broersma, Reference Lemhöfer and Broersma2012). These assessments were placed at the end of the session to minimize their potential influence on participants’ performance in the moral judgment task and to reduce fatigue-related confounds.

2.4. Data analyses

2.4.1. Pre-processing analyses

All statistical analyses were performed in R (R Development Core Team, 2020), using the lme4 package (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015). Prior to model estimation, all variables were preprocessed to ensure data quality and model interpretability. Contrast coding was applied to categorical predictors to facilitate interpretation of main effects and interactions. The binary predictors were coded as follows: (1) Language (Foreign = −0.5, Native = 0.5) and (2) Vulnerability (Low = −0.5, High = 0.5).

For cognitive control, an index of the Stroop interference effect was calculated for each participant by subtracting the mean reaction time (RT) of control trials from that of incongruent trials (Bub et al., Reference Bub, Masson and Lalonde2006; Goldfarb & Henik, Reference Goldfarb and Henik2007). Greater interference scores reflect poorer cognitive control. To simplify interpretation, the difference scores were multiplied by −1, such that higher values indicated better cognitive control performance. Subsequently, cases with missing Stroop data were excluded. Outliers (i.e., ≥ M ± 2SD) were removed and the remaining scores were standardized (z-scores). Likewise, self-reported emotional distress, measured on a 7-point Likert scale, was standardized prior to inclusion in the model. Standardizing continuous variables mitigated scale disparities and improved model convergence and interpretability (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken2013).

For the dependent variable, moral decision (0 = deontological; 1 = utilitarian), an additional outlier screening procedure was performed. Specifically, each participant’s proportion of deontological choices was computed and standardized. Participants with z-scores exceeding ±2 were flagged and removed from the dataset. After excluding 47 participants during data preprocessing (see Figure 1 for details), the final dataset comprised 255 participants, meeting the sample size requirements determined in the power analysis.

2.4.2. Main analyses

The primary analyses were conducted using mixed-effects logistic regression models, appropriate for binary outcome variables (Jaeger, Reference Jaeger2008). Rather than fitting the dependent variable directly, these models estimate the probability of each possible outcome (i.e., deontological versus utilitarian judgment). We constructed a series of models with the following fixed effects: language, vulnerability, cognitive control (Z Stroop), emotional distress (Z Distress), and all possible interactions among them. To account for individual and item-level variability in baseline response tendencies, we included random intercepts for both participants (ID) and scenarios (Item). The random-effects structure also incorporated by-participant random slopes for vulnerability, emotional distress, and their interactions. However, random slopes were not specified for language or cognitive control because neither predictor exhibited within-participant variability. Language was manipulated between participants, and cognitive control was measured as a stable individual-difference variable, leaving no within-participant variation for slope estimation. Similarly, to prevent potential overfitting and ensure model convergence given the relatively small number of scenarios (N = 14), we only included random intercepts for scenarios and did not model by-scenario random slopes.

To identify the best-fitting model while maintaining parsimony, we followed a systematic model comparison procedure, beginning with a maximal random-effects structure (Barr, Reference Barr2013). We first attempted to fit a model including all possible random slopes. When convergence issues arose, we iteratively simplified the random effects structure by removing random slopes, prioritizing the elimination of overly complex components that could contribute to overfitting. Each iteration was compared using likelihood ratio tests via the anova () function to ensure that simplifications did not significantly reduce model fit. The final, best-fitting model was selected based on this stepwise comparison, with the Akaike Information Criterion used as an additional diagnostic for model selection. The random effects structure of our final model included random intercepts for both participants (ID) and scenarios (Item) to account for baseline variability, and also a by-participant random slope for emotional distress (Z Distress). The significance of main effects and interactions was tested using likelihood ratio tests implemented through the mixed () function from the afex R package.

3. Results

3.1. Moral foreign language effect

To address RQ1, we first examined whether the MFLE emerged consistently across the 14 moral dilemmas. The analysis revealed no significant main effect of Language on moral decision-making (χ2 (1) = 0.50, p = .479), which indicates that the MFLE did not emerge as a robust or universal effect across all participants and dilemmas in the current dataset. However, descriptive statistics suggest a non-significant trend, with participants in the NL condition displaying slightly lower utilitarian response rates (55.32%) than those in the FL condition (57.14%). Given the lack of a significant main effect, we proceeded with further analyses to investigate potential moderating factors that might interact with language context to influence moral judgments.

3.2. Victim vulnerability and language

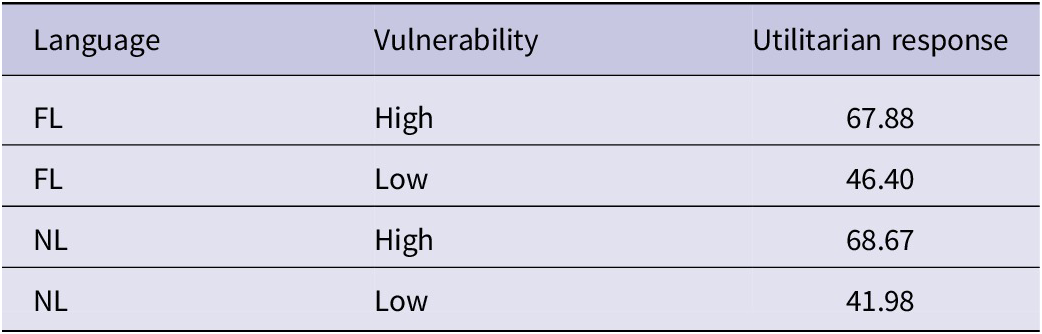

To address RQ2, we examined whether victim vulnerability interacted with language context in shaping utilitarian judgments. Descriptive patterns (see Table 3) indicated a consistent tendency toward more utilitarian decisions in high-vulnerability scenarios across both language conditions.

Table 3. Percentages of utilitarian judgments by language and vulnerability

The mixed-effects model revealed a main effect of Vulnerability (χ2 (1) = 7.72, p = .005), suggesting that participants were significantly more likely to choose the utilitarian option when the potential victim was highly vulnerable (β = 1.160, SE = 0.362, z = 3.204, p = .001) (see Figure 3). In contrast, no significant interaction between Language and Vulnerability was found (χ2 (1) = 3.15, p = .076). Overall, these findings show that although victim vulnerability did not significantly modulate the MFLE, it exerted a robust and independent influence on participants’ utilitarian tendencies.

Figure 3. Interaction effect of language and vulnerability on the probability of utilitarian responses (%). Note: Error bars represent standard errors.

3.3. Cognitive control, emotional distress and vulnerability

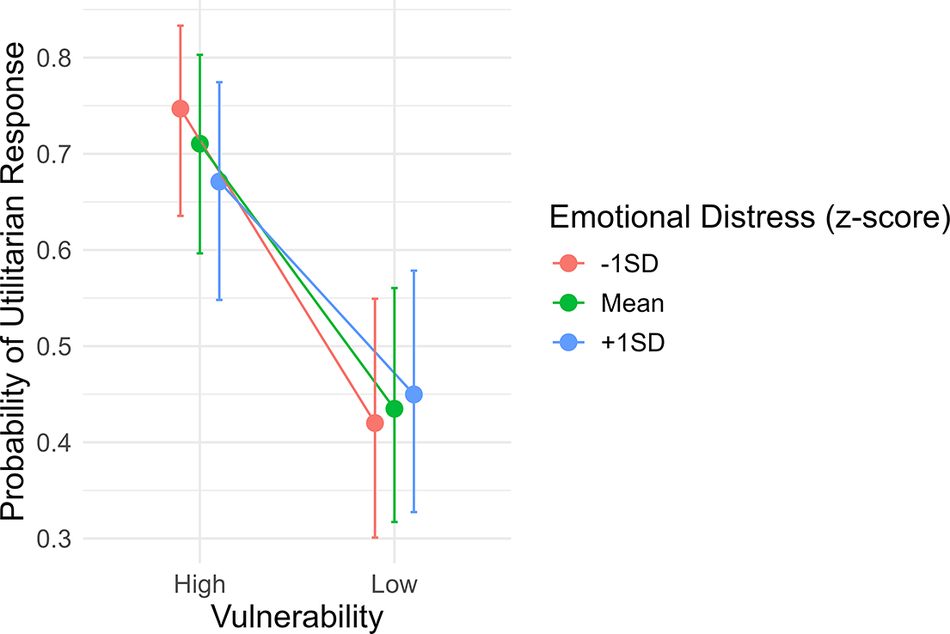

To address RQ3, we examined whether cognitive control and emotional distress moderated the effect of victim vulnerability on moral judgments. The analysis revealed a significant interaction between emotional distress and vulnerability (χ2 (1) = 9.41, p = .002), indicating that emotional distress moderated the influence of victim vulnerability on moral decision-making. Specifically, as emotional distress increased, the difference in utilitarian judgments between high- and low-vulnerability scenarios decreased, indicating that emotional distress attenuated the effect of vulnerability (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Interaction effect between vulnerability and emotional distress on the probability of utilitarian responses (%).

To unpack this interaction, we examined the simple effects of vulnerability at three levels of emotional distress: (1) low distress (−1 SD): the difference in utilitarian judgment between high- and low-vulnerability scenarios was largest (β = 1.405, SE = 0.372, z = 3.778, p < .001). This indicates that under low distress, participants were significantly more likely to make utilitarian judgments in high-vulnerability than low-vulnerability scenarios. (2) Moderate distress (mean): the effect of vulnerability remained significant but was reduced (β = 1.160, SE = 0.362, z = 3.203, p = .001); (3) high distress (+1 SD): the difference in utilitarian responses further diminished (β = 0.915, SE = 0.370, z = 2.474, p = .013). These findings underscore the moderating role of emotional distress, such that individuals experiencing higher distress were less sensitive to victim vulnerability in their moral judgments.

3.4. Cognitive control, emotional distress and language

To investigate whether cognitive control and emotional distress modulated the emergence of the MFLE, we tested the interactions between Language and these two predictors. The analysis revealed that neither cognitive control (χ2 (1) = 0.28, p = .594) nor emotional distress (χ2 (1) = 0.02, p = .901) significantly moderated the effect of language on moral judgments, providing further evidence for the absence of a robust MFLE in the present sample.

Beyond the language-related hypotheses, we conducted a post-hoc exploratory analysis to examine the potential interaction between cognitive control and emotional distress. This analysis was performed without a strong a priori hypothesis regarding the specific interaction. The results revealed no significant interaction (χ2 (1) = 2.82, p = .093). For illustrative purposes, the pattern of this non-significant interaction is depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Interaction effect between cognitive control and emotional distress on the probability of utilitarian responses (%).

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate whether the MFLE persists across 14 moral dilemmas, and how victim vulnerability, cognitive control, and emotional distress interact with language context to influence utilitarian moral judgments.

4.1. Absence of a robust MFLE

Contrary to our hypothesis and previous studies supporting the MFLE (Cipolletti et al., Reference Cipolletti, McFarlane and Weissglass2016; Geipel et al., Reference Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Surian2015a), no significant effect of language on utilitarian judgments was observed. This finding is consistent with a growing number of recent studies reporting null or mixed effects of language context on moral decision-making (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Foucart, Hayakawa, Aparici, Apesteguia, Heafner and Keysar2014; Del Maschio et al., Reference Del Maschio, Del Mauro, Bellini, Abutalebi and Sulpizio2022; Privitera et al., Reference Privitera, Li, Zhou and Wang2023; Yavuz et al., Reference Yavuz, Küntay and Brouwer2024), suggesting that the MFLE may not be as universal or robust as previously assumed.

From a dual-process perspective (Greene et al., Reference Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley and Cohen2001, Reference Greene, Nystrom, Engell, Darley and Cohen2004), several factors may account for these inconsistencies across studies and help explain the absence of a significant MFLE in the present study. Specifically, certain methodological features may attenuate the language effect by influencing the baseline balance between System 1 and System 2 processing. One such factor is the brevity and limited contextualization of the stimuli. As noted by Privitera (Reference Privitera2024), brief scenarios might induce psychological distance, thereby reducing emotional immersion. Although our dilemmas involved life-or-death decisions, their concise presentation may have constrained participants’ emotional engagement, dampening the emotional System 1 reactivity even in the native language. Furthermore, despite efforts to culturally adapt the stimuli (e.g., replacing foreign place names), some scenarios (e.g., terrorism-related cases) may have remained unfamiliar or implausible within the Chinese sociocultural context. This cultural distance could have further weakened emotional resonance across both language conditions, thereby limiting the scope for the “reduced emotion” pathway of the MFLE to operate, potentially creating a floor effect.

Another critical factor concerns the type of moral processing elicited by the task. The current study employed a decision-making format (e.g., “Would you do it?”), which differs conceptually and cognitively from moral evaluation tasks (e.g., “Is this action morally right or wrong?”). Existing research suggests that moral decision-making tasks elicit more pragmatic and goal-directed reasoning, with less reliance on emotional intuitions (Gold et al., Reference Gold, Pulford and Colman2015; Malle, Reference Malle2021; Schaich Borg et al., Reference Schaich Borg, Hynes, Van Horn, Grafton and Sinnott-Armstrong2006). Therefore, the consequence-focused task may have engaged participants’ deliberative System 2 in both language conditions. As a result, any additional cognitive boost from FL processing may have been redundant, thus reducing the likelihood of observing a MFLE.

In summary, from a dual-process perspective, we propose that the combination of attenuated System 1 activation (due to brief, culturally distant stimuli) and maximized System 2 engagement (imposed by the decision-making format) jointly suppressed the emergence of the MFLE in the present study.

4.2. The role of victim vulnerability in moral judgment

A key finding of our study is the significant influence of victim vulnerability on utilitarian choices, observed consistently across both native and foreign language contexts. Contrary to our initial hypothesis, participants were more likely to endorse utilitarian decisions when the potential victim was portrayed as highly vulnerable. This represents the first systematic experimental manipulation of victim vulnerability within moral dilemmas, allowing for a direct assessment of its effect on moral decision-making.

These findings challenge earlier evidence suggesting that vulnerable individuals tend to elicit more deontological moral evaluations. Prior research has shown that harm directed toward socially vulnerable groups, such as the elderly or women, often leads to increased deontological judgments, shaped in part by stereotypes and normative expectations (Barreto et al., Reference Barreto, Ryan, Schmitt, Barreto, Ryan and Schmitt2009; Chu & Grühn, Reference Chu and Grühn2018; Kite et al., Reference Kite, Stockdale, Whitley and Johnson2005). In contrast, our results indicate that high vulnerability can increase utilitarian judgments in sacrificial dilemmas. We attribute this discrepancy to the nature of the moral conflict in the scenarios. In prior studies, such as Nucci et al. (Reference Nucci, Turiel and Roded2018), participants were asked to judge the acceptability of harm, a task format that focuses attention on the inherent moral properties of the action itself. By highlighting the wrongness of the harmful act, this framing may in turn amplify protective instincts toward the weak. In the present study, the forced-choice format likely redirected attention toward pragmatic consequence evaluation, dampening emotional responses to vulnerable victims and increasing utilitarian responses in high-vulnerability dilemmas.

From another perspective, our findings align with evidence suggesting that protective responses toward vulnerable victims are context-dependent. Yoo and Smetana (Reference Yoo and Smetana2019), for example, found that in the context of psychological harm, children judged harm to vulnerable victims as less wrong than harm to typical victims. Similar to Yoo and Smetana, our study involves complex conflicts in which simple “protect the weak” rules are insufficient. Here, the conflict arises from the pragmatic demands of a forced-choice task, requiring participants to weigh outcomes and select the least harmful option. Thus, our findings extend prior work by demonstrating that vulnerability effects are sensitive to the type and complexity of moral conflict.

Theoretically, CLT (Trope & Liberman, Reference Trope and Liberman2010) provides a lens for interpreting the effect of victim vulnerability. According to CLT, highly vulnerable victims should be perceived as psychologically close, due to their social dependency and emotional relevance. Our materials also support this assumption: high-vulnerability contexts reflect concrete, low-level construal features across multiple dimensions (e.g., physical fragility). Such psychological closeness would typically be expected to suppress utilitarian judgments. Yet, our results reveal the opposite pattern, suggesting the operation of a non-standard psychological mechanism. To account for this paradoxical finding, we propose a novel mechanism termed “defensive distancing.” This account, grounded in literature on threat and defensive processes (e.g., Correia et al., Reference Correia, Alves, Sutton, Ramos, Gouveia-Pereira and Vala2012), posits that the effect is driven by an emotional overload that triggers a defensive cognitive shift. Specifically, we argue that highly vulnerable victims are perceived as psychologically too close, a closeness that renders the prospect of harming them emotionally overwhelming. This intense emotional pressure, in turn, prompts the cognitive system to adopt a coping strategy: it shifts from a concrete, emotionally painful representation to an abstract, high-level construal of the dilemma. By reframing the situation as a depersonalized mathematical problem (“saving the greater number”), this defensive shift facilitates utilitarian decision-making by making it more psychologically tolerable. Thus, the observed increase in utilitarian responses reflects an intense psychological distancing process deployed to manage the emotional threat generated by extreme closeness.

Finally, the effect of vulnerability may also be interpreted through the lens of Chinese collectivist cultural values. Unlike individualistic contexts, which emphasize individual rights and inviolability (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Meindl, Beall, Johnson and Zhang2016; LeFebvre & Franke, Reference LeFebvre and Franke2013), collectivist moral reasoning prioritizes group harmony, social stability, and the welfare of the collective (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Meindl, Beall, Johnson and Zhang2016; Stamkou et al., Reference Stamkou, Van Kleef, Homan, Gelfand, Van De Vijver, Van Egmond, Boer, Phiri, Ayub, Kinias, Cantarero, Efrat Treister, Figueiredo, Hashimoto, Hofmann, Lima and Lee2019; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Yu and He2024). In this context, vulnerability can be reframed relationally: protecting the collective may justify individual sacrifices (Mann & Cheng, Reference Mann and Cheng2013). This aligns with the concept of “selfless collectivism” (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Yu and He2024), wherein sacrificing a psychologically closer individual for the greater good is interpreted as an altruistic act in high-conflict situations. From a dual-process perspective (Greene et al., Reference Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley and Cohen2001, Reference Greene, Nystrom, Engell, Darley and Cohen2004), this mechanism may attenuate the emotional salience of individual harm when collective outcomes are at stake, thereby facilitating utilitarian judgments. Taken together, the present findings underscore the need for culturally sensitive models of moral judgment that account for the dynamic interplay between victim vulnerability and sociocultural norms.

4.3. Emotional distress as a modulator of vulnerability sensitivity

Consistent with our initial hypothesis, we further identified emotional distress as a significant moderator of the vulnerability effect: under low distress, participants showed strong sensitivity to victim vulnerability, making more utilitarian choices when victims were highly vulnerable. However, higher emotional distress diminished this sensitivity, flattening moral distinctions based on vulnerability.

The present finding suggests that emotional overload may blunt attention to contextual moral cues, shifting judgments toward a more generalized deontological stance and reducing flexibility in moral reasoning. This aligns with dual-process theories (Greene, Reference Greene2013; Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2003), where intense emotional arousal favors intuitive responses over deliberative, context-sensitive evaluation.

Importantly, this finding nuances the role of distress in moral judgment: rather than uniformly increasing deontological responses, distress appears to limit the influence of contextual factors such as victim vulnerability, narrowing the moral “lens” through which decisions are made. This has important implications for understanding the interaction between emotional and cognitive load in complex social judgments.

4.4. Cognitive control and its complex role

Another aim of our study was to examine whether cognitive control modulates the effects of language and victim vulnerability on moral judgment. Contrary to our hypotheses and prior findings (Privitera, Reference Privitera2024), no significant interaction was observed. Two methodological considerations may help explain this null effect. First, participants’ relatively low L2 proficiency (NL: M proficiency = 5.93; FL: M proficiency = 5.92) likely imposed substantial cognitive load during the task. High processing demands in the FL condition may have consumed executive resources, leaving limited capacity for cognitive control to exert modulatory influence (Oppenheimer, Reference Oppenheimer2008). Under such high-load conditions, even individuals with high executive functioning may not effectively engage in reflective, top-down moral reasoning. Second, the cognitive control measurement method may also play a role. Whereas Privitera (Reference Privitera2024) employed the Simon task, which primarily assesses response inhibition and conflict monitoring, we used the Stroop task, which targets selective attention and interference control. These tasks, while both tapping executive function, engage distinct neural and cognitive mechanisms (Scerrati et al., Reference Scerrati, Lugli, Nicoletti and Umiltà2017), potentially leading to differential sensitivity in capturing moral decision modulation. These methodological differences underscore the need for future work to examine multiple executive control components within the same study.

Despite the absence of a significant moderating effect in our primary analyses, the exploratory examination of the interplay between cognitive control and emotional distress revealed noteworthy tendency that challenges classic dual-process predictions. Across both language conditions, we observed a consistent, though non-significant, pattern in which higher cognitive control was associated with fewer utilitarian responses. Moreover, this negative association weakened as emotional distress increased. This trend runs counter to the conventional assumption that cognitive control reliably facilitates utilitarian responding by overriding emotional intuitions (Greene et al., Reference Greene, Morelli, Lowenberg, Nystrom and Cohen2008). Instead, the pattern aligns more closely with recent findings reported by Privitera (Reference Privitera2024), suggesting that the role of cognitive control in moral judgment may be more context-dependent than traditionally assumed. This perspective implies that cognitive control may be better conceptualized as a domain-general capacity for goal maintenance rather than a simple facilitator of utilitarian judgments. Its impact on judgment is thus contingent on which moral goal is currently prioritized. One plausible interpretation of our data is that individuals with stronger cognitive control are better equipped to uphold deontological commitments, such as harm aversion, particularly under low emotional arousal. However, this regulatory advantage appears susceptible to disruption under heightened distress, which may diminish individuals’ capacity to maintain principled, rule-based resistance to harm. In other words, when the moral goal is to avoid harm, cognitive control supports that deontological objective; its functional role is determined by the context. In this view, cognitive control does not uniformly promote utilitarian reasoning; rather, it flexibly supports context-relevant moral goals, and its influence is itself modulated by emotional intensity.

Taken together, these findings highlight that cognitive control does not exert a uniform effect on moral decision-making. Instead, its role appears to be modulated by affective state, cognitive load and measurement approach. Future studies should move beyond binary dual-process assumptions and adopt more nuanced models that integrate emotion, cognition and context-specific variables in shaping moral judgments.

4.5. Limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations that require cautious interpretation. First, our assessment of cognitive control relied exclusively on a single Stroop task, which captures only a relatively stable, trait-level component of executive functioning. This approach has two constraints: trait-level measures may not reflect state-level fluctuations during moral reasoning, and the Stroop task alone does not fully represent the multidimensional architecture of executive functions, including inhibition, updating and cognitive flexibility (Banich et al., Reference Banich, Mackiewicz, Depue, Whitmer, Miller and Heller2009; Miyake et al., Reference Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, Howerter and Wager2000). Future research should employ a more comprehensive battery of tasks (e.g., Simon, n-back, task-switching) to disentangle contributions of specific executive subcomponents and incorporate state-level assessments (e.g., dual-task paradigms) to capture momentary cognitive load during moral decision-making.

Second, we did not measure participants’ prior familiarity with the moral dilemmas used in the experiment. Previous studies suggest that moral evaluations may be influenced by individuals’ personal experience or prior exposure to similar moral scenarios (Carpendale & Krebs, Reference Carpendale and Krebs1995). This uncontrolled factor may have introduced unexplained variability in responses, potentially obscuring subtle experimental effects. Future studies should systematically assess and control for prior familiarity to isolate experimental effects more precisely.

Third, although the Chinese and English dilemmas were matched for sentence count, variations in textual length and complexity were not strictly controlled across items. Differences in cognitive load, processing depth and emotional engagement may have independently affected moral judgment (Privitera, Reference Privitera2024). Future research should standardize scenario properties, including length, narrative structure and emotional salience, across languages and items to improve internal validity.

Finally, our measurement of emotional distress relied exclusively on self-report. Subjective reports may not fully capture real-time emotional arousal or physiological reactivity. Future studies could complement self-report measures with physiological indices of emotional distress (e.g., skin conductance responses, heart rate variability) to provide a more comprehensive assessment of emotional processes in moral decision-making.

5. Conclusion

This research offers several important insights into the MFLE and the cognitive–affective mechanisms underlying moral judgment. First, our findings challenge the assumption that the MFLE is a universal phenomenon. Instead, the effect appears to be context-dependent and interacts with situational cues such as victim vulnerability. The robust effect of victim vulnerability, observed across both language conditions, highlights its role as a powerful, language-independent factor that influences decision-making in complex moral contexts. Second, the interaction between victim vulnerability and emotional distress provides strong support for the dual-process framework. Elevated emotional arousal appears to disrupt deliberative processing, thereby diminishing individuals’ sensitivity to contextual information such as the vulnerability of the victim. Third, the results reveal a nuanced role of cognitive control. Rather than exerting a uniform influence on moral judgment, its impact seems contingent upon emotional states and task-specific demands.

Taken together, these findings move beyond a purely language-deterministic view of moral judgment. Instead, they point toward a dynamic, integrated framework in which moral decisions emerge from the interaction of language context, emotional regulation, cognitive capacity and salient victim characteristics.

Data availability statement

The supplementary materials, data and analyses that support the findings of this study are openly available in Open Science Framework at: https://osf.io/jwy85/?view_only=1b5fae81a6884deea6f8ec7655aa3f6d [View-Only link].

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund Youth Project [25CYY080].

Competing interests

The authors declare none.