Many include the concepts of religious freedom and separation of religion and state (SRAS) as a core element of Western liberal values and assume that Western democracies value and follow these principles.Footnote 1 This study examines whether 28 EU states in practice have SRAS using data from the Religion and State (RAS) dataset and finds that none of these states meet a “zero-tolerance” standard of SRAS and only five meet a very loose SRAS standard. In addition, among the world’s democracies, EU states have less SRAS than other democracies. Thus, I argue, the terms SRAS, rainbows, and unicorns can be reasonably used in the same sentence with regard to the EU. This raises questions of the extent to which EU governments follow political secularism and demonstrates the persistence of religious cleavages in the EU.

This study first examines the source of the assumption of a link between liberal Western democracies and SRAS. I then examine the differences between three standards of SRAS common in Western democracies. Finally, I operationalize these standards and evaluate how many EU countries meet these standards.

Assumptions of Separation of Religion and State in Western Democracies

There is a strong dual assumption in much of the literature that addresses liberal democracy and politics: that liberal democratic states ought to maintain SRAS and, in fact, meet this standard. This is based on an ideology known as political secularism, which is a subset of the more general concept of secularism. Secularism can be defined in many ways, but all of them involve the negation of religion, separation from religion, or something different from religion. (Philpott, Reference Philpott2009: 185) It is a very broad concept that can apply to individuals, society, and government.

Political secularism more narrowly applies to governments. It involves religion being separate or different from the state, or perhaps a state which is anti-religious. Fox (Reference Fox2015: 28) defines it as “an ideology or set of beliefs which advocates that religion ought to be separate from all or some aspects of politics and/or public life.” Casanova (Reference Casanova2009: 1051) similarly defines “secularism as a statecraft principle” as “some principle of separation between religious and political authority.” Rawls (Reference Rawls1993: 151) more generally argues that we must “take the truths of religion off the political agenda.” All discussions of secularism in this study focus on political secularism unless otherwise specified. As I discuss in more detail in the next section, political secularism is not a monolithic ideology and has multiple manifestations in Western politics.

This political secular assumption also includes providing religious freedom. While there are several different formulations of the proper way to achieve SRAS, Alfred Stepan’s concept of the “twin tolerations” provides a good description of this philosophy’s prescriptive elements:

Religious institutions should not have constitutionally privileged prerogatives that allow them to mandate public policy to democratically elected governments. At the same time, individual religious communities…must have complete freedom to worship privately. In addition, as individuals and groups they must be able to advance their values publicly in civil society and to sponsor organizations and movements in political society, as long as their actions do not impinge negatively on the liberties of other citizens or violate democracy and law. (Stepan, Reference Stepan2000: 39-40)

Stepan (Reference Stepan2000: 40) also argues that “analysts frequently assume that the separation of church and state and secularism are core features not only of Western democracy, but of democracy itself.”

However, Stepan (Reference Stepan, Calhoun, Juergensmeyer and VanAntwerpen2012: 131-133) acknowledges that not all democracies respect SRAS. Also, not everyone accepts this normative argument, but even those who believe there is a role for religion in democratic government envision a limited role. de Tocqueville, perhaps the best-known advocate for a role for religion in democracy, argues that a “successful political democracy will inevitably require moral instruction grounded in religious faith,” (Fradkin, Reference Fradkin2000: 90-91) but does not support the concept of an official religion. Rather, de Tocqueville believes that religion can “facilitate the use of democracy” (Fradkin, Reference Fradkin2000: 88) by preventing it from degenerating into despotism. More specifically,

since it facilitates the use of freedom, [religion is]…’indispensable to the maintenance of republican institutions.’ And there is good reason for this, because ‘despotism may govern without religion, but liberty cannot.’ (Wach, Reference Wach1946: 90 with quotes from de Tocqueville)

Others make related arguments. For example, Bader (Reference Bader1999), Durham (Reference Durham, van der Vyver and Witte1996: 19), and Greenawalt (Reference Greenawalt1988: 49, 55) argue that religion cannot be fully banned from the public sphere due to the liberal concept of tolerance. Driessen (Reference Driessen2010), Marquand & Nettler (Reference Marquand and Nettler2000), and Mazie (2004; Reference Mazie2006) argue that a government may establish an official religion without violating liberal values, provided that it protects religious freedom and does not make a religion mandatory. Thus, liberal states can have official religions, but, at the same time, must maintain elements of SRAS.

Be that as it may, many argue that political secularism, religious freedom, and SRAS are distinct features of the West in the context of comparing the West and the non-West. Perhaps the best-known version of this argument is Huntington’s (1993; Reference Huntington1996) argument that “the separation and recurring clashes between the church and state that typify Western civilization have existed in no other civilization. The division of authority contributed immeasurably to the development of freedom in the West.” (Huntington, Reference Huntington1996: 75) There is no shortage of concurring arguments. For example, Calhoun (Reference Calhoun, Calhoun, Juergensmeyer and VanAntwerpen2012: 86) argues that “the tacit understanding of citizenship in the modern West has been secular. This is so despite the existence of state churches, presidents who pray, and a profound role for religious motivations in major public movements.” Appleby (Reference Appleby2000: 2) argues that “the core values of secularized Western societies, including freedom of speech and freedom of religion, were elaborated in outraged response to inquisitions, crusades, pogroms, and wars conducted in the name of God.” Demerath & Straight (Reference Demerath and Straight1997: 47) argue that “there is no question that the secular-state secular-politics combination is often associated with Western Europe in particular.” Inboden (Reference William, Desch and Philpott2013: 164) argues that “the post-Enlightenment tradition in the West of treating religion as an exclusively private and personal matter sometimes prevents policymakers from perceiving the public and corporate nature of religion in many non-Western societies.”Footnote 2

This assumption has deep roots. One strand of the literature focuses on its origins in the evolution of Christianity. Martin (Reference Martin1978: 25-49), for example, links religious tolerance and SRAS in the West to the rise of Protestantism because Protestant denominations had a less symbiotic relationship with the state than the Catholic Church and were far more tolerant of denominational dissent. Protestant theology also played a role. It places a greater emphasis on individualism than Catholicism, making Protestants less likely to place their religion above the state. In addition, some Protestant theologies include the concept of common grace, which increases support for universal rights. Finally, the Protestant reformation increased religious pluralism in Europe, which facilitated increased tolerance and SRAS. Woodbury & Shah (Reference Woodbury, Shah, Hoover and Johnston2012) similarly argue that Protestantism in the non-West is associated with the foundations of democracy, including religion’s independence from the state, an independent civil society, mass education, pluralism, reduced corruption, and economic development.

Others focus on evolving Catholic ideology. For example, Philpott (Reference Philpott2004) and Anderson (Reference Anderson2000) argue that Vatican II (1962-1965) fundamentally changed the Catholic Church, making it more tolerant of religious minorities and supportive of democracy. The Church has also become more active in human rights and socioeconomic issues, but less active in local politics, leaving more room for democracy.

Perhaps the deepest roots of this assumption is secularization theory which predicts, among other things, that modernity will reduce or even eliminate religion’s influence on government and society.Footnote 3 Originally, the theory predicted religion’s demise across the world but, given abundant evidence that this has not occurred, beginning in the 1990s, many argue that the secularization process, including increased SRAS, is specific to the West. Some of these arguments apply more broadly than to just SRAS, but the declining role of religion in government is a clear element of these arguments. For example, Berger (Reference Berger2009: 69) argues that “a consensus now exists that secularization theory can no longer explain the worldwide persistence and spread of modern religious movements, with the exception of western and central Europe as well as intellectuals in general.” Marquand & Nettler (Reference Marquand and Nettler2000: 2) argue that “Western Europe appears to be an exception …Organized religion almost certainly plays a smaller role in politics in 2000 over most of the territory of the European Union than it did in 1950.” Haynes (Reference Haynes1997: 709) posits that “secularization continues in much of the industrialized West but not in many parts of the Third World” and that past views of religion’s decline have “undergone revision, with some seeing a near-global religious resurgence, with only Western Europe not conforming to the trend.” (Haynes, Reference Haynes2009: 293)Footnote 4 This retreat of secularization theory is understandable because the original model for the theory was the presumed secularization of the West.

Secularization theory is closely related to another body of theory, which argues that various uniquely Western social and political processes have increased religious freedom and SRAS in the West. According to these arguments, Europeans have rejected religion in politics due to their increased individualism and liberalism, as well as the trauma of past religious wars. Western governments have subordinated religious institutions and instituted equality policies. (Haynes, Reference Haynes1997; Reference Haynes1998; Reference Haynes2009) In this new environment, European churches have adopted more liberal ideals and focused their theologies on tolerance. For example, Kuhle (Reference Kuhle2011) argues that governments in Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, and Iceland have successfully pressured their national (Lutheran) churches to change their theologies on a wide variety of issues, including the ordination of women and gay marriage.

Charles Taylor (Reference Taylor2007) focuses on the evolution of Western religious belief positing that religion no longer legitimizes Western states because the West has shifted from “a society where belief in God is unchallenged…to one in which it is understood to be one option among others.” (Taylor, Reference Taylor2007: 3) Norris & Inglehart (Reference Norris and Inglehart2004) use economic reasoning to arrive at a similar conclusion. They argue religion is no longer necessary in the West because developed states have existential security. That is, when people no longer need to worry about basic personal security issues like food, shelter, and safety, they have less need of a God to provide them.

These assumptions, while remaining common, have been repeatedly challenged, particularly by empirical studies which demonstrate religion remains politically relevant in the West. In general, these studies do not address the larger question of whether the West is secular, has SRAS, or supports religious freedom. Rather, they tend to assume religion is relevant and focus on more specific topics. These studies address the role of religion in the European Union and European integration (Nelsen & Guth, Reference Nelsen and Guth2015), the role of religious political parties in Europe (Minkenberg, Reference Minkenberg2009; Raymond, Reference Raymond2020), the influence of religion in populist and right-wing parties (Beuter & Kortmann, Reference Beuter and Kortmann2023; Cremer, Reference Cremer2023; Molle, Reference Molle2019) the registration of religious communities in Europe (Flere, Reference Flere2010), religious accommodations for Muslims (Kwon, et. al., Reference Kwon, McCaffree and Taylor2020) perceptions of religious freedom (Breskaya, et. al., Reference Breskaya, Giordan and Zrinščak2021; Breskaya & Giordan, Reference Breskaya and Giordan2021) the regulation of Islam in European public education, (Ciornei, et. al., Reference Ciornei, Euchner and Yesil2021), the impact of government interference in religion on religious giving, (Cokgezen & Hussen, Reference Cokgezen and Hussen2020), the influence of religion on perceived discrimination, (Aisa & Larramona, Reference Aisa and Larramona2021), the link between religiosity and veil bans (Hoffman & Rosenberg, Reference Hoffman and Rosenberg2022), the influence of religion on a government’s legitimacy, (Fox & Breslawski, Reference Fox and Breslawski2023) and religious organizations acting as interest groups (Grzymala-Busse, Reference Grzymala-Busse2016 Reference Grzymala-Busse2015; Minkenberg, Reference Minkenberg2012; Pfaff & Gill, Reference Pfaff and Gill2006; Warner, Reference Warner2000).

Polling data demonstrates that religion influences Western attitudes toward European integration and the European Union, (Boomgaarden & Woost, 2009; Reference Boomgaarden and Woost2012; Hagevi. Reference Hagevi2002; Minkenberg, Reference Minkenberg2009; Nelsen, et. al., Reference Nelsen, Guth and Fraser2001), immigration and refugees (Bohman & Hjerm, Reference Bohman and Hjerm2013; Grotsch & Schnabel, Reference Grotsch and Schnabel2012; Reference Grotsch and Schnabel2013; Vaughan, Reference Vaughan2021), party politics and choice (van der Brug, et. al., Reference van der Brug, Hobolt and de Vreese2009), democracy (Vlas & Gherghina, Reference Vlas and Gherghina2012), voting (Barklay, Reference Barklay2020), identity in Europe (Schnabel & Hjerm, Reference Schnabel and Hjerm2014; Verkutyten, et. al. Reference Verkutyten, Malieparrd, Martinovic and Khoudja2014), and attitudes toward Muslims as well as comparisons between Muslim and Christian political attitudes. (Brekke, Reference Brekke2018; Dangubić, et. al., Reference Dangubić, Verkuyten and Stark2020; Fetzer & Soper, 2003; Helbling, 2014; Helbling & Traunmuller, 2015; 2020; Helbling, et. al., Reference Helbling, Jager and Traunmüller2022)

Recent studies have also shown that Christian nationalism is increasingly influential in Western politics. (Broeren & Djupe, Reference Broeren and Djupe2024; Davis, et. al., Reference Davis, Perry and Grubbs2024) However, this phenomenon focuses largely on a combination of identity politics and individual rights, particularly religious freedom, at least for Christians. (Goff, et. al., Reference Goff, Silver and Iceland2024) There is considerable overlap between Christian nationalism and religious populism, which is also on the rise in the West. However, this movement tends not to be “associated with religious organizations nor have religious policies per se but identify ‘the people’ and their enemies according to a religious or civilizational classification.” (Cesari, Reference Cesari2024: 2)

There are some exceptions to this trend, which make broader claims relating to the continuing role of religion in Western and European politics. Branas-Garza & Solano (Reference Branas-Garza and Solano2010: 347) show that “the proportion of clearly religious-averse [European] citizens is very small and never larger than 6%. That is, almost all individuals are somewhat concerned about societal secularization. Therefore, in electoral terms, the potential cost of pro-religion policies is very low.” Madeley & Enyedi (Reference Madeley John and Enyedi2003: 2) argue that “it is probably no exaggeration to say that almost nowhere in Europe’s 50-odd sovereign territories are significant issues of the relationship between religious organizations, society, and the state completely absent from the political agenda.” Helbling & Traunmuller (2015: 2) argue that “European democracies are far from secular…Institutions of state support of religion are not only widespread in Western Europe but also are a significant and tangible element of the public life and collective identities of its citizens.” Finally, Thomas (2010: 17) argues that “religion is coming back into European politics. Europe has become a mission field for devout Muslims and evangelical Christians from the global South.” Also, examinations of European institutions such as the European Court of Human Rights show a bias where Christian litigants suing for religious freedom are more likely to prevail. (Richardson, Reference Richardson, Breskaya, Finke and Giordan2024)

Given all of this, I consider the question of whether European Union governments, in fact, maintain SRAS an empirical question. I focus on the EU because the expectation of SRAS is specifically for liberal democracies. EU states have explicitly joined a union that not only formally espouses liberal democratic values but also has the means to enforce them.

Competing definitions of Separation of Religion and State

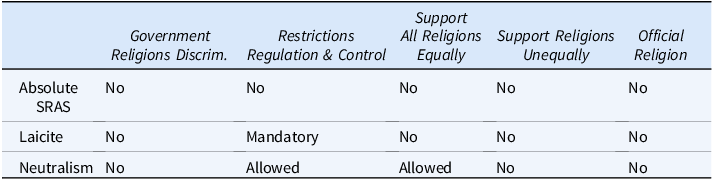

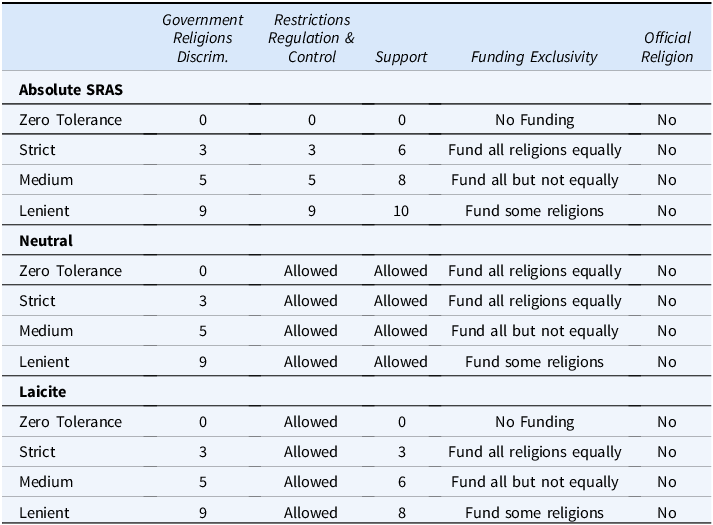

In the West, there are three distinct politically relevant philosophies on how SRAS should be applied in practice. These categories basically represent whether or not the state may engage in five types of activities: (1) restricting the religious practices or institutions of minority religions in a manner it does not restrict the majority religion, (2) restricting, regulating, or controlling the majority religion (often along with other religions), (3) supporting religion in general, and (4) giving preferential support to one or some religions over others. (5) Declaring an official religion. I summarize the discussion on these three types of SRAS with respect to these questions in Table 1.

Table 1. Standards of Separation of Religion and State (SRAS) in Theory

Absolute SRAS. This philosophy, which is the dominant perspective on SRAS in the United States, requires the state to stay out of religion as much as possible by banning all government support for religion and interference in religion. Thus, the state may not engage in any of the five types of policy in Table 1 with two caveats. First, while passing generally applicable laws, there may be some inadvertent regulation of religion. For example, Church buildings are not exempt from building codes and zoning restrictions. Second, there is some diversity within this philosophy over the appropriate role of religion in public, such as in political discourse and civil society. In the United States, for example, the mainstream view accepts the expression of religion in public life and even in political discourse, but there is considerably less support for religious views influencing policy in even a general manner. (Esbeck, Reference Esbeck1988; Kuru, Reference Kuru2009)

Laicite is derived from the French policy of that name. It restricts not only any role for religion in politics but also any religious presence in the public sphere. This anti-religious philosophy views religion as something which is negative, primitive, violent, and undermines democracy. For this reason, it must be strictly excluded from the public sphere. It considers religion a private matter, so religious expression in private is permissible. Accordingly, the state maintains and enforces a secular public space where religion should not be seen. (Durham, Reference Durham, van der Vyver and Witte1996: 21-22; Esbeck, Reference Esbeck1988; Haynes, Reference Haynes1997; Keane, Reference Keane2000; Kuru, Reference Kuru2009; Stepan, Reference Stepan2000)

Supporting religion equally or preferentially contradicts Laicite. Regulating all religions, including the majority religion, is not only allowed but expected because this is necessary to maintain a secular public space. However, government restrictions on the practices or institutions of a minority religion that do not apply to the majority religion are inconsistent with this philosophy because it effectively shows a preference for the non-restricted religions. Any measure necessary to maintain a secular public space should be applied to all religions. A good example of this model is France’s 2004 law that bans overt religious symbols in public schools. While this happens to particularly restrict the head coverings worn by Muslim women, the law is written and applied generally. This contrasts with policies in the schools of other European countries, which specifically ban head coverings but not other religious symbols. (Fox, Reference Fox2020)

The neutralism philosophy achieves SRAS by treating all religions equally. A government may support or restrict religions as long as it does so equally for all religions. Madeley & Enyedi (Reference Madeley John and Enyedi2003: 5-6) argue that this conception “requires that government action should not help or hinder any life-plan or way of life more than any other and that the consequences of government action should therefore be neutral.” Thus, it may not engage in differential support or restrict religious minorities in a manner that it does not restrict the majority religion.Footnote 5 Even differential support violates neutralism because religion is not free. When a state supports a religion financially, for example, it is making this religion less expensive for its members than non-supported religions. This inequality gives this religion an advantage in acquiring and retaining members. (Stark & Finke, Reference Stark and Finke2000)Footnote 6

Measures of Government Religion Policy

This study uses the RAS dataset, which includes a wide variety of measures of government religion policy and currently covers 1990 to 2014. All data in this study is from 2014, the most recent year available. Each of the five aspects of a potential SRAS definition listed in Table 1 is operationalized using variables from the RAS dataset. I analyze these measures for all countries that were EU members in 2014. The full details of all of these variables are available at the RAS webpage.Footnote 7 In this section, I discuss each of these variables and their general distribution in EU states.Footnote 8 In the next section, I discuss how they relate to the SRAS standards I use in this study.Footnote 9

This study looks at five different RAS variables to measure SRAS, or more precisely, its absence: government-based religious discrimination (GRD), Restrictions, regulation, and control (RRC) of the majority religion, government religious support (GRS), whether governments finance religion, and whether the state declares an official religion. As discussed in detail in Fox (2011; Reference Fox2015; Fox, Finke, & Mataic, Reference Fox, Finke and Mataic2018), each of these variables measures a different aspect of government religion policy and can have very different dynamics and motivations. For this reason, most RAS-based studies, including this one, measure and analyze them separately.

The RAS project defines GRD as “restrictions placed by governments or their agents on the religious practices or institutions of religious minorities that are not placed on the majority religion.” (Fox, Reference Fox2020: 3) To discriminate means to treat unequally, so this variable does not include restrictions placed on religious minorities that are also placed on the majority religion. As noted above, this is a form of government religion policy that is inconsistent with all conceptions of SRAS used in this study. GRD includes 36 distinct types of religious discrimination including (1) twelve types of restriction on religious practices such as restrictions on the public observance of religious festivals or the sabbath, (2) eight types of restriction on religious institutions and clergy such as restrictions on building, maintaining, and repairing places of worship, (3) eight types of restriction on conversion and proselytizing such as restrictions on proselytizing by foreign missionaries and (4) nine other types such as the arrest, detention or harassment of religious figures. Each variable is scaled from 0 to 3 based on how widespread and severe the restrictions are, so the combined variable ranges, in theory, from 0 to 108. Among the EU countries, in 2014, GRD ranged from 1 in Estonia to 30 in Bulgaria and Germany

RRC of the majority religion is often, but not necessarily, applied to all religions in a state. It includes 29 distinct types of RRC each measures based on severity on a scale of 0 to 3 which creates a combined measure with a potential range of 0 to 87. RRC includes (1) five types of restriction on religion’s political role such as restrictions on religious political parties, (2) nine types of restrictions or regulation of religious institutions such as the government appoints or must approve of high level clerical appointments, (3) seven types of restriction on religious practices such as restrictions on the display of religious symbols in public places, and (4) six other types of restriction such as restrictions on religious hate speech. In practice, levels of RRC in the EU in 2014 range from 0 in Italy to 17 in Denmark.

RAS measures 52 types of GRS. All are measured as present in a state or not, creating a scale that potentially ranges between 0 and 52. These types of support include: (1) 21 ways a government might enact religious ideology or precepts as law such as bans on abortion, (2) five types of laws or institutions which enforce religion such as blasphemy laws or religious courts, (3) eleven ways a government might fund religion such as paying clergy salaries or direct grants to religious organizations, (4) six types of entanglement between religious and government institutions such as a government religion ministry or requirements that a head of state or monarch belong to the state religion, (5) Nine other types of support such as religious symbols of flags or religious education in public schools. Levels of support in these countries in 2014 range from four types in Austria to 17 types in Denmark.

The RAS finance variable measures whether EU governments finance religion unequally. In 2014, all EU states financed religion in some manner. Three of them, Cyprus, the Netherlands, and Slovenia, do so equally for all religions for which there is a substantial number of adherents in the country. Lithuania funds all religions, but the funding is not equal. All other states fund only one or some religions.

Finally, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Malta, and the UK all had established religions in 2014.

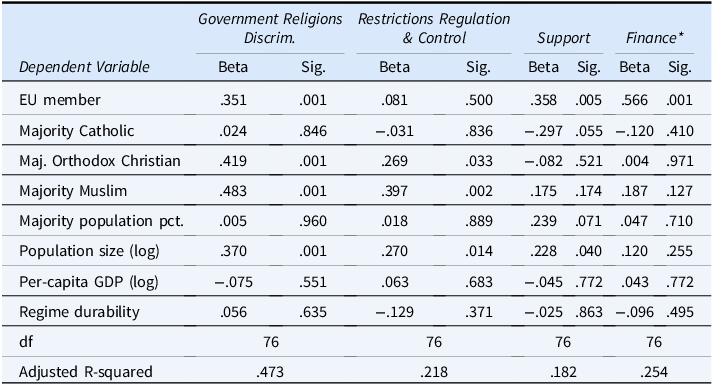

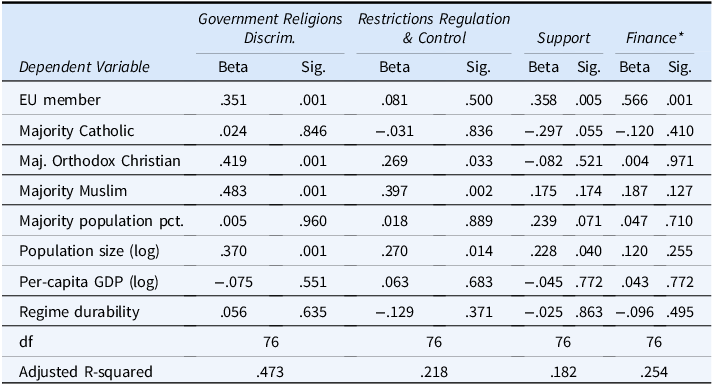

Given this, it is clear that EU governments are heavily involved in religion in a manner that likely undermines SRAS. In addition, as shown in Table 2, EU states are more likely than other democracies to engage in most of these types of policy, indicating that EU states have less SRAS than other democracies across the world. This multivariate analysis looks at democracies only—all countries which score an 8 or higher on the Polity scale (which ranges from −10, the most autocratic, to 10, the most democratic). (Jaggers & Gurr, Reference Jaggers and Gurr1995) It controls for factors included in previous analyses of the RAS data (e.g., Fox, 2015; Reference Fox2020). These include the majority religion, the percentage of the country population which belongs to the majority religion,Footnote 10 the country’s population size, per capita GDP,Footnote 11 regime durability measures, and the number of years since the last change in the country’s Polity score, and whether the country is an EU member. The results show that among democracies, GRD, support, and financing religion are more common in EU member states in 2014. Orthodox and Muslim-majority states engage in higher levels of GRD and RSC.

Table 2. OLS Multivariate Analysis Predicting Government Support for Religion in 2014 among Democracies

*This variable measures the number of types of financial support for religion.

While this indicates that SRAS is not a strong feature in EU member states, in the next section, I evaluate more specifically how many of these states met any of the three standards of SRAS I analyze in this study.

Measuring SRAS

The three standards of SRAS that we discuss in this study, laicity, absolute separationism, and neutralism, can be measured using these five variables. More specifically, we can ask whether each standard allows these practices and measure whether the countries in the EU engage in these types of policies or not. This requires a descriptive rather than a causal analysis because either a state scores low enough on these measures to have SRAS according to these standards, or it does not.

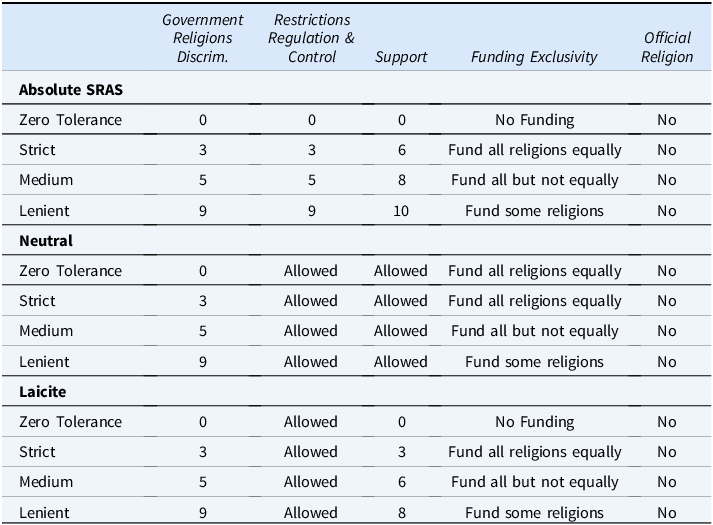

Table 3 shows how each of these standards overlaps with these five variables using four standards. The first standard is “zero-tolerance” where if a standard bans an action, the state must meet this standard with no exceptions. For example, if it bans GRD, then the country must engage in no GRD. The strict, medium, and lenient standards allow the country to engage in this activity to some extent based on the argument that some states may, in general, comply with these standards, but there may be a few isolated exceptions.

Table 3. Converting Religion and State Codings to Measure Separation of Religion and State

The lenient standards allow a considerable amount of government intervention in religion. For example, the lenient standard for absolute separationism allows scores of 9, 9, and 10, respectively, for GRD, RRC, and GRS. This means a government may engage in three types each of GRD and RRC of the most severe coding or as many as nine of each with a lower coding, as well as ten types of GRS, and still meet this standard. While few would consider such a state to have SRAS, if, as is the case, few states meet even this lenient standard, this would provide a good demonstration that SRAS is uncommon in the countries included in the study. These cutoffs are the same for all three standards for GRD. Only the absolute separationism standard bans RRC. The neutral standard does not ban equal support. The standards for support are slightly stricter for the laicite standard than the absolute separationism standard because laicite not only demands no support, but it demands a secular public space. The standards for financial support are less strict for the neutral standard because it allows equal support. None of the standards allows a state religion, which would violate even the most lenient of standards.

This range of standards is, admittedly, somewhat arbitrary. However, they achieve the goal of measuring both strict adherence to SRAS as well as standards so loose that many would dispute that states which barely meet these standards have SRAS. Though I argue that it is possible to argue states that meet these loose standards meet the spirit of SRAS to some extent. Thus, if, as is the case here, most states do not even meet these loose standards, it is reasonable to argue that SRAS is rare in the EU.

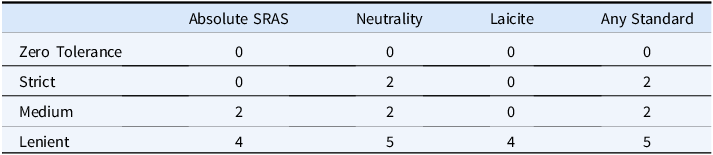

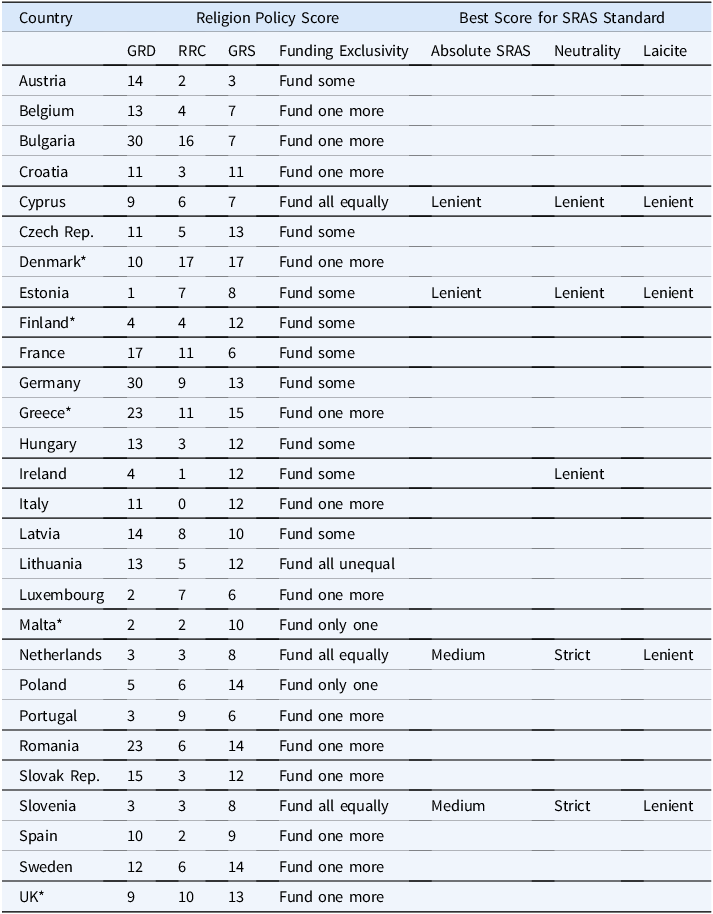

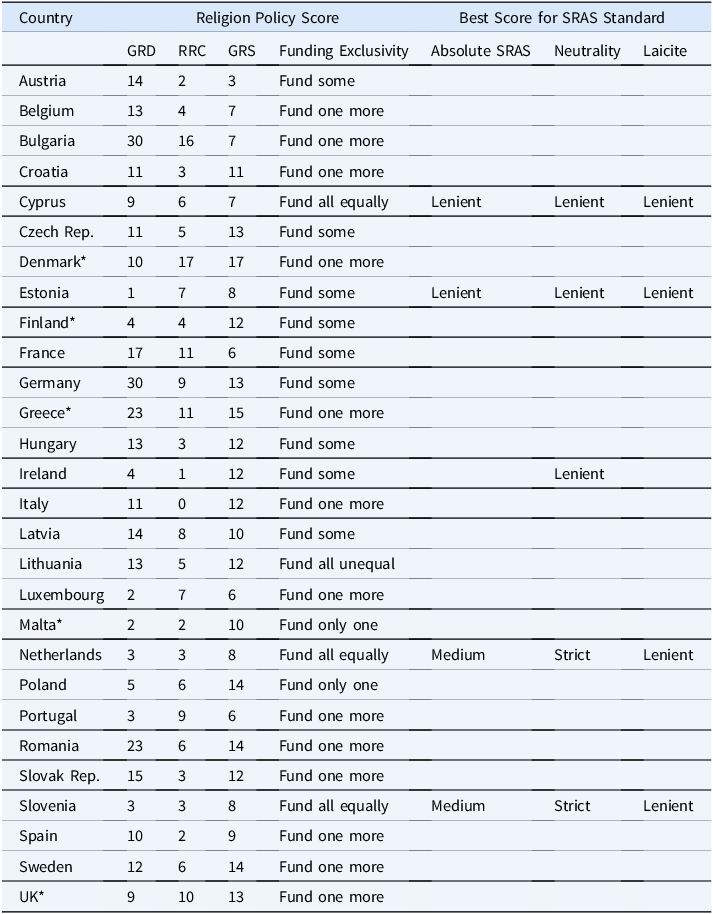

Table 4 presents the number of states that meet each standard, and Table 5 lists all of the EU states, how they score on each of the variables, and the strictest standard in each category that they meet. These results show that few EU states meet even the loose standards.

Table 4. Number of EU Countries meeting each Separation of Religion and State (SRAS) Standard

Table 5. Country listing of RAS Scores and Whether They Meet any Separation of Religion and State (SRAS) Standard

*Country has an official religion.

More specifically, no EU state meets any of the zero-tolerance standards. Thus, strictly speaking, no EU state has SRAS by any of these three standards. The Netherlands and Slovenia meet the strict standard for neutrality, the medium standard for absolute separationism, and the lenient standard for laicite. Cyprus and Estonia meet the lenient versions of all three standards, and Ireland meets the lenient standard for neutrality. Thus, of 28 EU states, only 5, less than 18%, meet at least one of the lenient standards examined in this study, and all of them violate SRAS in some manner based on a zero-tolerance standard.

This clearly demonstrates that, depending on how strictly one holds states to these standards, SRAS is either uncommon or nonexistent in the EU. The Netherlands, one of the two states that meets at least one strict standard, provides some context. It engages in three actions considered by the RAS project to constitute GRD. First, it places some restrictions on minority clergy by requiring all imams and other spiritual leaders recruited in Islamic countries to complete a year-long integration course before permitting them to practice. (US State Department, 2012-2013) Second, the government monitors Mosques and Imams to see if they engage in hate speech or support the Islamic state. (Dutch News, 2014a) Third, courts have ruled that employers may fire or refuse to hire employees who will not comply with “reasonable” expectations to engage in actions that a worker might refuse to do because it violates their religious beliefs. This includes wearing religious clothing to work, refusing to work on religious holidays, shaking hands with the opposite gender in meetings, or facial hair policies. (US State Department, 2009-2014) Interestingly, all three of these types of GRD are in practice applied to Muslims only and not any of the other religious minorities present in the country.

The only form of RRC coded in the Netherlands is restrictions on religious hate speech. The law protects freedom of speech and press, except for speech, writings, or imagery that deliberately offends a group of people because of their race, religion or beliefs, sexual orientation, or physical, psychological, or mental handicap. Such speech constitutes a criminal offense. Due to a significant increase in hate speech on the internet, authorities introduced a hotline for people to report offensive postings and increased the number of referrals to courts for possible prosecution. There were several convictions for anti-Semitic hate speech, but convictions are rare due to a desire to preserve free speech in public debate. (US State Department, 2013) In March 2009, the Supreme Court limited the interpretation of this law, ruling that criticizing a religious ideology (as distinct from its followers) does not necessarily constitute a criminal offense. This restriction was the basis for dismissing hate speech charges against Freedom Party leader Geert Wilders. (US State Department, 2009) Similarly, charges against the rector of Rotterdam Islamic University, who criticized non-believers and Alevis, were dismissed. (Dutch News, 2014b)

The Netherlands engages in eight types of support for religion coded by the RAS project. (1) Some localities limit the number of Sundays per year a business may be open. (Radio Netherlands, 2010) (2) Article 23.5 of the country’s constitution makes a provision for public funding of religious education in private schools. (3) The government subsidizes universities providing training for residents interested in becoming imams. (US State Department, 2013; Van Ysselt, Reference Van Ysselt and Messner2015) (4) Organizations with religious affiliations which provide social services, such as hospitals and retirement homes or youth activities, may receive funding as non-profit organizations. (5) The government paid the salaries of clergy in the islands of the former Netherlands Antilles which became municipalities of the Netherlands (beginning in 2010) until their contracts expired but made; no new contracts for state-paid clergy. The state also provides subsidies to provide clergy in the military, prisons, hospitals and retirement homes. (US State Department, 2013; Van Ysselt, Reference Van Ysselt and Messner2015) While the RAS project does not code the salaries for clergy in hospitals or the military as government funding of clergy, it does code funds for clergy in retirement homes. (6) There is some government funding for the restoration and maintenance of religious buildings designated as historic or cultural sites. (Van Ysselt, 2015; US State Department, 2013) (7) Article 23.3 of the Constitution states that “Education provided by public authorities shall be regulated by Act of Parliament, paying due respect to everyone’s religion or belief.” Article 23.5 provides for funding for religious education in public schools. Public schools teach about religion so as to prepare students for life in a religiously diverse society, but do not promote any particular religion. (Franken & Loobuyck, Reference Franken and Loobuyck2011; Van Ysselt, Reference Van Ysselt and Messner2015) (8) While there is no legal requirement for religious groups to register with the government. Groups “of a philosophical or religious nature” may register in order to receive certain rights and privileges, such as tax exemptions. There are no criteria regarding membership or doctrine. (US State Department, 2013)

Overall, this is a significant level of government involvement in religion. As much of it involves funding and supporting religion in a generally equal manner, it is consistent with a neutralist approach. Similarly, the approach to religious hate speech suggests the appropriateness of allowing some leeway in considering whether a country meets a SRAS standard. However, the GRD present in the Netherlands is focused mostly on Muslims. Interestingly, the Netherlands allows employers to refuse to hire or even fire people who refuse to work on Muslim religious holidays, but at the same time restricts businesses from being open on Sundays, the Christian Sabbath. Thus, within this larger neutral approach to religion, one can still find some preference for Christianity over other religions.

Given this, even states that meet a “strict” standard for SRAS engage in practices that undermine their SRAS and certainly do not meet a zero-tolerance SRAS standard.

Conclusions

Karl Deutsch (Reference Deutsch and Polsby1963) argues in his article “the limits of common sense” that our assumptions are often incorrect. While our common sense can reveal important relationships it can also, in our fertile imagination, cause us to see relationships that are not valid. For this reason, it is essential for researchers to question their own preconceived notions, overcome biases, and engage in systematic analysis and empirical investigation. Engaging in this endeavor demonstrates that assumptions of SRAS in Western democracies are not accurate when examining the policies and laws of EU states. In addition, while the study does not focus on religious freedom, the fact that all of these states in 2014 restricted the religious practices and/or institutions of religious minorities in a manner that was not applied to the majority religion indicates a deficit of religious freedom as well.

This finding that SRAS in the EU is as common as rainbows and unicorns has implications far beyond the narrow questions asked in this study. It implies that basic assumptions about the politically secular nature of liberal democracy are false. Either SRAS and religious freedom are not basic requirements for liberal democracy, or one could that argue most states considered liberal democracies are not, in fact, liberal democracies. It is certainly true that even if the EU states value SRAS in theory, this value is imperfectly put into practice.

One of the basic issues involved is that, in essence, both religions and the concept of liberal democracies are normative belief systems. As such it is unlikely that they can be fully compatible. Religions generally contain rules guiding one’s behavior, which often involve behavior that overlaps with the political. (Fox, Reference Fox2018) Also, the concept of SRAS is historically recent. Even when efforts are made to apply a version of this standard, it can be difficult to fully overcome the legacy of the past, where states were intimately intertwined with religion.

An additional key factor is that both religious and secular ideologies can cause states to become involved in religion. That religious ideologies can motivate state support for religion and GRD is well known and documented. However, secular ideologies can lead to the same result through several dynamics. Religious practices considered abhorrent to at least some secular ideologies can be restricted. These include at least three prominent secular-religious clashes in the EU. First, female modesty (particularly head coverings) can clash with some interpretations of women’s’ rights beliefs. Religious requirements for the ritual slaughter of animals can run afoul of some secular beliefs regarding animal rights. Finally, some secular advocates consider Jewish and Muslim male infant circumcision rituals a violation of the child’s bodily integrity. Also, one of the most effective means for restricting religions is to support the religious institutions, but require in return some level of government influence over those institutions. All of these practices are common in the European Union. (Fox, 2015; Reference Fox2020) In fact, in many instances, secular governments through their support of national churches have forced these churches to change their doctrines on issues such as female clergy and same-sex marriage (Kuhle, Reference Kuhle2011). Thus, even secular impulses can undermine the SRAS in that they can cause the state to become more rather than less involved in religion.

In addition, the EU is becoming more religiously diverse which challenges its Christian roots and has contributed to the rise to Christian Nationalist and populist movements opposing immigration and the presence of certain religious minorities. While the extent to which this is truly driven by Christianity is unclear, it is part of a longer-term European tendency to raise the issue of Christianity when confronted with Islam, as occurred during debates over the Turkish accession to the EU. (Boomgaarden & Woost, Reference Boomgaarden and Woost2012; Minkenberg, Reference Minkenberg2012) Nelsen & Guth (Reference Nelsen and Guth2023: 1) argue similarly that despite a decline in religiosity in Europe, “a set of beliefs, practices, and institutions, religion is the core of broader confessional cultures, overall ways of life shaped by particular religious traditions” constitute “powerful, common formative conditions” in Europe. All of this demonstrates the importance of religious cleavages even in the most secular of European contexts.

Given all of this, this study demonstrates that both the question of what are Europe’s true values with regard to RAS and religious-secular cleavages require more study and contemplation.

Jonathan Fox received his Ph.D. in Government and Politics, University of Maryland, College Park 1997. He is currently the Yehuda Avner Professor of Religion and Politics at Bar Ilan University and director of the Religion and State Project. He has written on many areas of religious politics including government religion policy, religious minorities and religion in international relations. His most recent book is Religious Minorities at Risk (Oxford University Press, 2023).