Introduction

The dog is widely regarded as the first domesticated animal in human history, and its incorporation into human society has had profound effects on human cultural adaptations (Morey, Reference Morey2010; Losey et al., Reference Losey, Wishart and Loovers2018). Despite decades of research, identifying the origin of dogs has been elusive (Benecke, Reference Benecke1987; Germonpré et al., Reference Germonpré, Sablin, Stevens, Hedges, Hofreiter, Stiller and Després2009; Drake et al., Reference Drake, Coquerelle and Colombeau2015; Perri, Reference Perri2016; Botigué et al., Reference Botigué, Song, Scheu, Gopalan, Pendleton, Oetjens and Taravella2017; Thalmann and Perri, Reference Thalmann, Perri, Lindqvist and Rajora2019), although recent findings suggest dogs may have been independently domesticated in more than one geographical region (Frantz et al., Reference Frantz, Mullin, Pionnier-Capitan, Lebrasseur, Ollivier, Perri and Linderholm2016; Bergström et al., Reference Bergström, Stanton, Taron, Frantz, Sinding, Ersmark and Pfrengle2022). The process of dog domestication has likewise been contentious, with one hypothesis arguing that humans actively captured and hand-raised wolves, with these socialized wolves becoming reproductively isolated from wild populations, ultimately giving rise to early dogs (Serpell, Reference Serpell and Clutton-Brock1989, Reference Serpell2021; Müller, Reference Müller, Vigne, Peters and Helmer2005; Germonpré et al., Reference Germonpré, Lázničková-Galetová, Sablin, Bocherens, Stépanoff and Vigne2018, Reference Germonpré, Van den Broeck, Lázničková-Galetová, Sablin and Bocherens2021; Mech and Janssens, Reference Mech and Janssens2022; Brumm et al., Reference Brumm, Germonpré and Koungoulos2023). In contrast, a second hypothesis proposes a commensal pathway, in which wolves adapted to anthropogenic environments (Coppinger and Coppinger, Reference Coppinger and Coppinger2001; Zeder, Reference Zeder2012; Larson and Fuller, Reference Larson and Fuller2014; Morey and Jeger, Reference Morey and Jeger2015). In this scenario, wolves initially scavenged around human settlements, gradually adapting to this new ecological niche. Over time, mutual habituation likely developed between the two species, eventually leading to a two-way partnership between wolves and humans (Zeder, Reference Zeder2012, Reference Zeder2015).

To help resolve these hypotheses, unambiguous identification of early dogs in the archaeological record is needed. Recognition of early dog skeletal remains often depends on associated archaeological evidence that can provide direct connections to human activity. One example that provides such a link between dog skeletal remains and human activity is the 14,200-year-old Bonn–Oberkassel specimen, wherein a canid was interred alongside two adult humans (Janssens et al., Reference Janssens, Giemsch, Schmitz, Street, Van Dongen and Crombé2018). Unfortunately, such examples, particularly from the Late Pleistocene, are very rare and often challenging to interpret. As a result, skeletal remains of several proposed early dogs are highly contested, and some have been revealed to belong to lineages of Pleistocene wolves that were separate from those that led to modern dogs (Ramos-Madrigal et al., Reference Ramos-Madrigal, Sinding, Carøe, Mak, Niemann, Samaniego Castruita and Fedorov2021). When such canid specimens are recovered from Late Pleistocene contexts, they warrant detailed, extensive investigations to clarify any potential connection to the history of dog domestication.

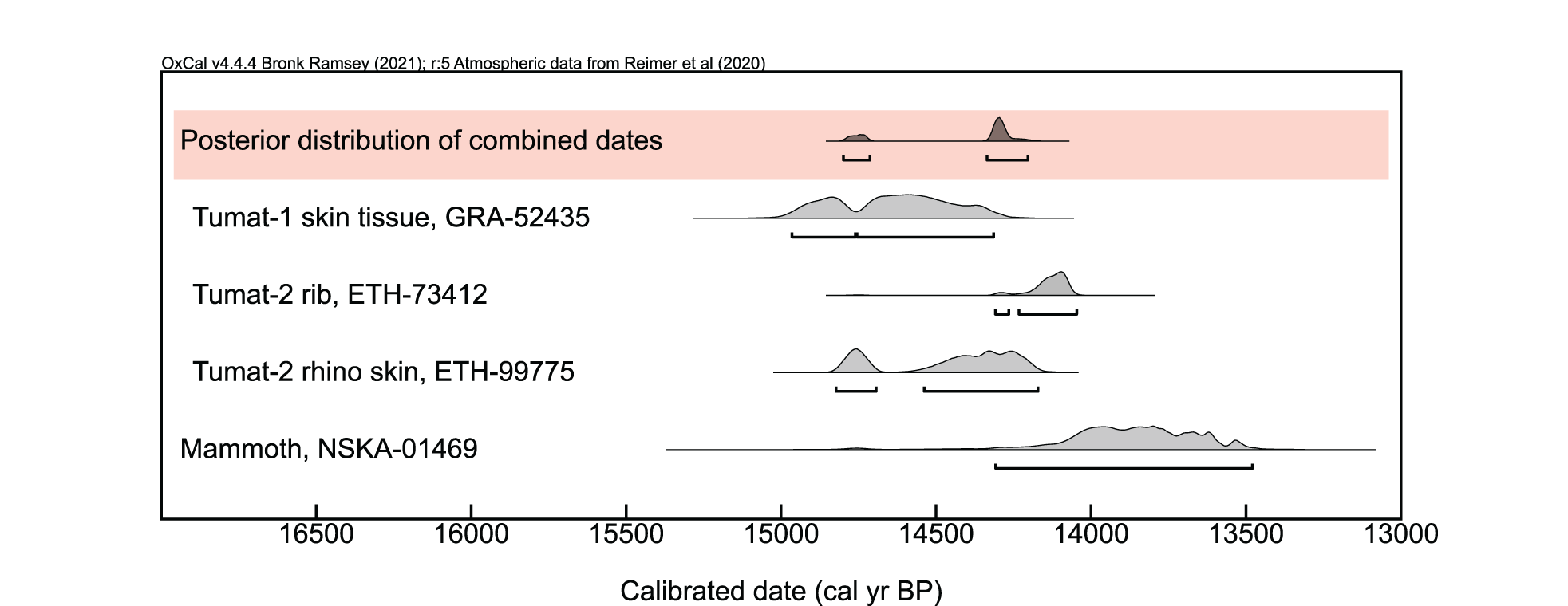

The so-called ‘Tumat Puppies’ (Fig. 1) were discovered at a location in northern Siberia that has since been named the Syalakh site (Fig. 2). Tumat-1 (14,965–14,314 cal yr BP, Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 1; Fedorov et al., Reference Fedorov, Garmaeva, Luginov, Grigoriev, Savvinov, Vasilev, Kirikov, Allentoft, Tikhonov, Kostopoulos, Vlachos and Tsoukala2014) was discovered by mammoth ivory hunters from the village of Tumat in 2011 (Fedorov et al., Reference Fedorov, Garmaeva, Luginov, Grigoriev, Savvinov, Vasilev, Kirikov, Allentoft, Tikhonov, Kostopoulos, Vlachos and Tsoukala2014), while Tumat-2 (14,309–14,046 cal yr BP, Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 1; Mak et al., Reference Mak, Gopalakrishnan, Carøe, Geng, Liu, Sinding and Kuderna2017) was uncovered during an excavation of the site in 2015 (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). As originally described by Kandyba et al. (Reference Kandyba, Fedorov, Dmitriev and Protodiakonov2015), the present day Syalakh site is situated on the eastern shore of an oxbow lake near the Syalakh River in the Sakha Republic (Yakutia), Russia, (Fig. 4A). The site consists of a terrace that is eroding due to seasonal freezing and thawing cycles. Behind the solifluction apron, excavators identified five stratigraphic layers (Fig. 4B), with the remains of the naturally mummified Tumat Puppies located between layers 2 and 3 in association with mammoth postcranial bones and a broken mammoth skull (Fedorov et al., Reference Fedorov, Garmaeva, Luginov, Grigoriev, Savvinov, Vasilev, Kirikov, Allentoft, Tikhonov, Kostopoulos, Vlachos and Tsoukala2014). Evidence of burning and human processing of the mammoth bones (Supplementary Fig. 3) suggests that the Syalakh site may have been a mammoth butchering site.

Figure 1. Photos of Tumat-1 (left) and Tumat-2 (right).

Figure 2. Location of the Syalakh site in Siberia. The village of Tumat, after which the canids were originally named, is located 40 km southwest of the Syalakh site. The inset map provides an overview of the location of the site in northern Asia. Map data are from OpenStreetMap (OpenStreetMap contributors, 2017) and prepared using QGIS (QGIS Development Team, 2023).

Figure 3. Calibrated radiocarbon dates for Tumat-1, Tumat-2, and the mammoth remains found at the Syalakh site. Note that the second date for Tumat-2 is taken from woolly rhinoceros skin found within the canid’s GI system. Because the Tumat Puppies are expected to be the same age, a posterior distribution of the combined ages was calculated; however, a χ2-test found these dates to be in poor agreement. See Supplementary Table 1 for more information. Repositories: GRA = Centre for Isotope Research, University of Groningen (GrM); ETH = ETH/AMS Facility, Institut für Teilchenphysik (ETH); NSKA = Geology and Paleogeography of Cenozoic Laboratory, Northeast Interdisciplinary Scientific Research Institute Russian Academy of Sciences, Far East Branch (MAG).

Figure 4. Plan and stratigraphy of the Syalakh site. (A) Overview of the Syalakh site with description of the current landscape. The site is eroding from the eastern side of an oxbow lake next to the Syalakh River. (B) Stratigraphic profile of the Syalakh site showing five distinct layers. The Tumat Puppies were found between layers 2 and 3 in the vicinity of the mammoth bone concentration, although due to solifluction of the melting permafrost, the precise location is unknown. Re-ice here refers to subsurface ice that forms in frost cracks by repeated addition of water and subsequent freezing.

Based on the proximity to putatively anthropogenic ecofacts, Fedorov et al. (Reference Fedorov, Garmaeva, Luginov, Grigoriev, Savvinov, Vasilev, Kirikov, Allentoft, Tikhonov, Kostopoulos, Vlachos and Tsoukala2014) hypothesized that the Tumat Puppies are early dogs. Association with the potential mammoth butchering site, if confirmed, could provide a compelling link to human activity, potentially leading to hypotheses that the Tumat Puppies were local domesticates, tamed wolves, or habituated scavengers. Although they were contemporaneous with the earliest confirmed Western European dogs (Janssens et al., Reference Janssens, Giemsch, Schmitz, Street, Van Dongen and Crombé2018), Ramos-Madrigal et al.’s (Reference Ramos-Madrigal, Sinding, Carøe, Mak, Niemann, Samaniego Castruita and Fedorov2021) whole-genome analysis of Tumat-2 showed that this individual was not directly related to modern dogs. However, this genetic evidence could still be compatible with a scenario in which the Tumat Puppies were part of a local domesticated lineage that went extinct without contributing to modern dog genetic history, or their pack could have been scavenging in areas of human activity. Although Bergström et al. (Reference Bergström, Stanton, Taron, Frantz, Sinding, Ersmark and Pfrengle2022) found a three base pair KB deletion in Tumat-2, a genotype that gives rise to black fur and is believed to have introgressed from dogs into wolves, the unresolved status of the Tumat Puppies makes it difficult to assess whether the deletion evolved before or after canid domestication.

The exceptional preservation of the Tumat Puppies provides an opportunity to investigate their suggested association with the mammoth remains at the site through dietary reconstruction based on their hard and soft tissues and gastrointestinal (GI) content. A further hypothesis, based on the proximity of the two individuals as well as their visual similarities, suggests that the Tumat Puppies were siblings from the same litter. Through the combination of osteometry, stable isotope analysis, plant macrofossils, metagenomic analysis of the GI content, and genomic kinship analysis, this study evaluates the two hypotheses and obtains novel insight into the life and death of these two Pleistocene canids.

Methods

In 2014, 2016, and 2018, subsamples were provided by SF and distributed to the individual researchers and institutes involved in this study for the purpose of the analyses summarized below. Detailed descriptions of all methods are available in the Supplementary Information (SI).

Radiocarbon dating

To evaluate whether putatively butchered mammoth bones from the Syalakh site are contemporaneous with the Tumat Puppies, a fragment of mammoth metacarpal was dated using accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) at the Cenozoic Geochronology Center, Russia. The radiocarbon age of the mammoth and three published dates for the canids (Fedorov et al., Reference Fedorov, Garmaeva, Luginov, Grigoriev, Savvinov, Vasilev, Kirikov, Allentoft, Tikhonov, Kostopoulos, Vlachos and Tsoukala2014; Mak et al., Reference Mak, Gopalakrishnan, Carøe, Geng, Liu, Sinding and Kuderna2017; Lord et al., Reference Lord, Dussex, Kierczak, Díez-Del-Molino, Ryder, Stanton and Gilbert2020) were calibrated with OxCal 4.4.4 (Bronk Ramsey, Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) using the IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (Reimer et al., Reference Reimer, Austin, Bard, Bayliss, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey and Butzin2020) (Supplementary Table 1). The uncertainty of the calibrated dates is reported using a 95.4% (2σ) confidence interval.

Description and osteometry

Briefly, the full bodies, limbs, and fur of both individuals (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figs. 4–9) were measured and recorded. A full dissection was carried out on Tumat-1, and the stomach (Supplementary Fig. 10) was found to contain identifiable feathers (subsample T1:S4, Supplementary Fig. 11), as well as a piece of skin with hair still attached (subsample T1:S5, Supplementary Fig. 12). Tumat-2 was not fully dissected but remained in a semi-frozen state. During the limited dissection of Tumat-2, the stomach was cut open (Supplementary Fig. 13), which allowed subsampling from different sections of the stomach, and an additional sample was taken from the rectum.

The crown length (CL) of the upper dP2 and dP3, and the lower dp2 and dp3 were measured with calipers. Computed tomography (CT) scans were used to calculate the length of the skull (Fig. 5A), the length of the mandibula, the CL of the lower dp4, and of the germ of the lower carnassial (m1). The incompletely calcified crowns of the germs of the lower carnassials were reconstructed with Dragonfly 3.5 (Object Research Systems Inc., 2018) in order to verify which cusps were present (Fig. 5B). In dogs, antero-external cusps always develop first (Tims, Reference Tims1896). The CL of the lower molars were calculated based on the models as though the complete mesiodistal CL in these teeth had been reached, even without the development of the enamel. In completely developed dog molars, the maximum thickness of tooth enamel is about 1 mm (Crossley, Reference Crossley1995). The total CL of the lower first molar was estimated by adding 2×1 mm to the calculated CL of the germs of the Tumat Puppies. These measurements were compared with reference groups consisting of recent and ancient pups and adults of both wolves and dogs (Supplementary Tables 2–4). Age at death was determined by comparing the dentition of the Tumat Puppies with known deciduous and permanent dentition eruption sequences for several recent dog breeds and wolves. For Tumat-1, the age at death was also assessed based on fur development, where the length of the fur was measured in order to detect adult guard hair.

Figure 5. 3D images based on CT scans of the skulls and dentition of the Tumat Puppies. (A) 3D images of the skulls. (B) 3D images of the incompletely calcified crowns of the germs of the lower carnassials (m1). Full lines indicate the length, width, or height with measurements given; dotted lines indicate position of the measurement on the 3D model; ec = entoconid, hcl = hypoconulid, hy = hypoconid, me = metaconid, pa = paraconid, pr = protoconid; not to scale.

Stable isotope analysis

Elemental (C, N, S) and isotopic analyses (δ13C, δ15N, δ34S) were performed on bone, hair, and tissue samples collected from both Tumat Puppies (Supplementary Tables 5–8). For bone collagen, the reliability of the δ13C and δ15N values can be established by measuring collagen chemical composition, with atomic C:N ranging from 2.9–3.6 (DeNiro, Reference DeNiro1985) and the percentage of C and N above 8% and 3%, respectively (Ambrose, Reference Ambrose1990). δ34S values were retained from samples whose atomic C:S and N:S fit into the range of 300–900 and 100–300, respectively (Nehlich and Richards, Reference Nehlich and Richards2009), and whose percentage of S ranged between 0.13% and 0.27%, determined through the results of modern mammalian collagen (cattle, elk and camel) measured in the same sets. In contrast to what is known about bone collagen, there are few, if any, widely accepted criteria for quality control of skin, ligament, muscle, hair, and feather. However, because skin, ligament, and muscle are composed primarily of type I collagen, similar to bone, the same ranges for C:N, C:S, and N:S ratios can arguably be applied for these tissues (Lamb, Reference Lamb2016). Limited information is available for isotopic values in hair and feathers, but the keratin protein that makes up these tissues contains a high abundance of cysteine leading to a likely increase in S content. An estimated C:N range of 3.0–4.0 is expected in hair according to published data (Kuitems et al., Reference Kuitems, Van Kolfschoten and van der Plicht2015; Szpak and Valenzuela, Reference Szpak and Valenzuela2020) and internal analyses performed at the Tübingen laboratory, while a C:N range of 3.6–4.0 is anticipated for feather (Linglin et al., Reference Linglin, Amiot, Richardin and Porcier2020). Further research is required to refine the quality criteria of S content in hair and feathers, but until such a time, published data (Touzeau et al., Reference Touzeau, Amiot, Blichert-Toft, Flandrois, Fourel, Grossi, Martineau, Richardin and Lécuyer2014; Linglin et al., Reference Linglin, Amiot, Richardin and Porcier2020; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Shim, Shin, Choi, Bong and Lee2021) and internal analyses at the Tübingen laboratory suggest a range of 2.3–5.0% in S content is appropriate.

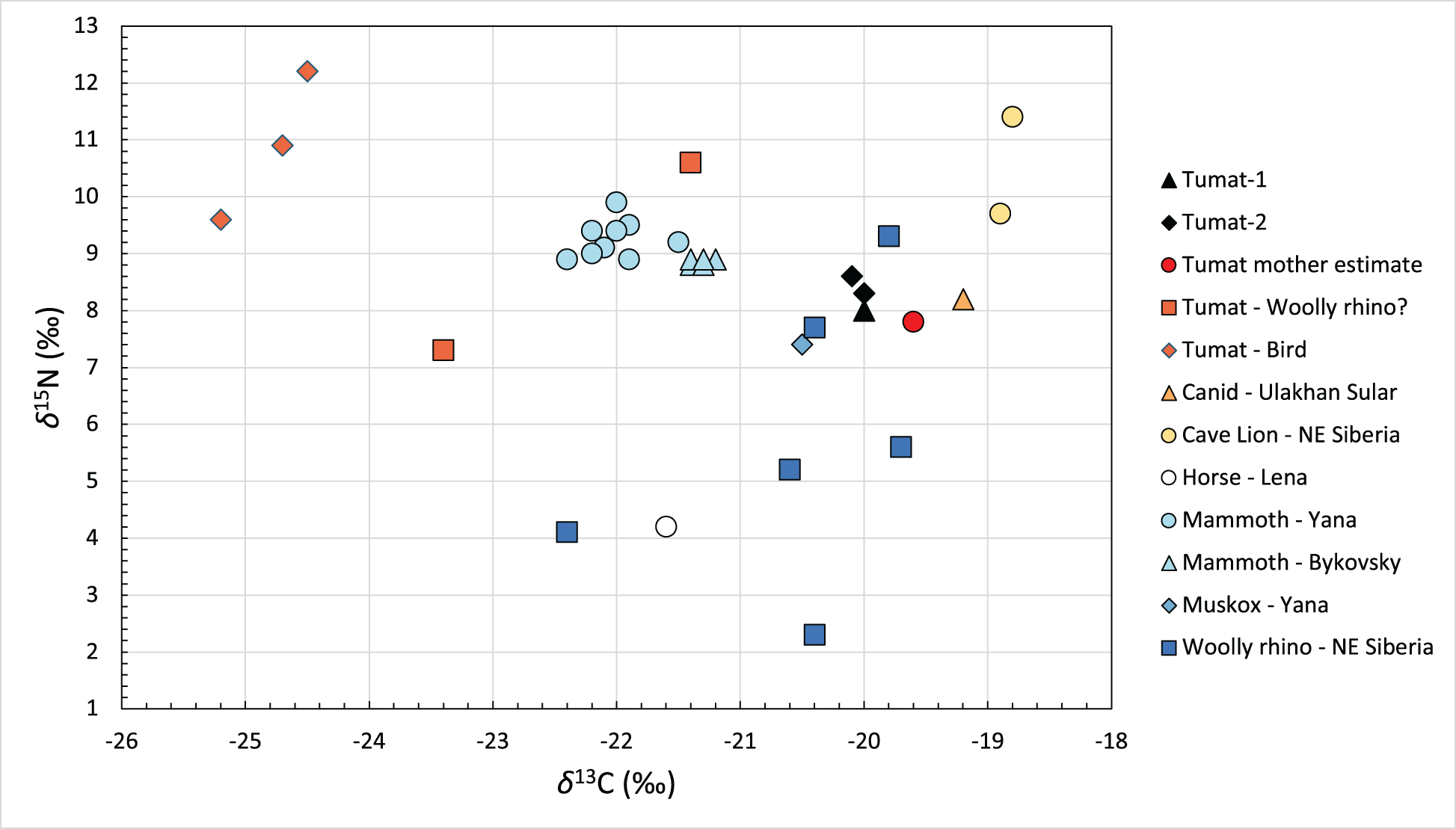

Maternal prey choice was reconstructed by adjusting the tissue (i.e., hair) that provided the lowest δ15N value to equivalent bone collagen values using the isotopic spacing between hair and collagen measured on the remains of a Paleolithic cave lion (Panthera spelaea) from the Chukchi Peninsula (Kirillova et al., Reference Kirillova, Tiunov, Levchenko, Chernova, Yudin, Bertuch and Shidlovskiy2015). Measurements from subsamples TUM1-ST1 and TUM2-ST1h were adjusted to bone collagen values using the same calculations described above for the body hair. Measurements from the feathers in subsamples TUM1-ST3, TUM1-ST4, and TUM2-ST2 were adjusted to bone collagen values using the work of Hobson and Clark (Reference Hobson and Clark1992). To complete the trophic web, published data were collected from large mammals from northeastern Siberia aged between ca. 16,400 and 12,000 14C yr BP (Supplementary Table 6).

Plant macrofossils

The stomach content samples were screened using an Olympus SZX 16 stereomicroscope, and plant remains were identified to the lowest possible taxonomic level using a reference collection at the Senckenberg Research Station of Quaternary Palaeontology and identification keys (Katz et al., Reference Katz, Katz and Kipiani1965; Berggren, Reference Berggren1969, Reference Berggren1981; Anderberg, Reference Anderberg1994). The taxa nomenclature follows the WFO Plant List (World Flora Online, 2024). The reconstruction of paleo-vegetation followed the methodology of Kienast et al. (Reference Kienast, Schirrmeister, Siegert and Tarasov2005, Reference Kienast, Tarasov, Schirrmeister, Grosse and Andreev2008, Reference Kienast, Wetterich, Kuzmina, Schirrmeister, Andreev, Tarasov, Nazarova, Kossler, Frolova and Kunitsky2011), and the identified vascular plant taxa were assigned to plant communities based on their ecological preferences and present-day occurrences (Hilbig, Reference Hilbig1995; Reinecke and Troeva, Reference Reinecke and Troeva2017).

Ancient DNA preparation and sequencing

Pre-PCR laboratory work was carried out in dedicated ancient DNA laboratory facilities in Copenhagen and Stockholm. Genomic DNA was extracted from seven GI samples from both Tumat-1 and Tumat-2 (Supplementary Table 9) following established methods for ancient DNA (Dabney et al., Reference Dabney, Knapp, Glocke, Gansauge, Weihmann, Nickel and Valdiosera2013; Allentoft et al., Reference Allentoft, Sikora, Sjögren, Rasmussen, Rasmussen, Stenderup and Damgaard2015; Rohland et al., Reference Rohland, Glocke, Aximu-Petri and Meyer2018). Raw DNA was converted to double-stranded Illumina libraries, using either a seminal protocol used by many ancient DNA researchers (Meyer and Kircher, Reference Meyer and Kircher2010) or the Blunt End Single Tube (BEST) protocol (Carøe et al., Reference Carøe, Gopalakrishnan, Vinner, Mak, Sinding, Samaniego, Wales, Sicheritz‐Pontén and Gilbert2018) to reduce the number of purification steps and increase library complexity. Indexing PCR was carried out using unique dual indexes to improve the accuracy of multiplex sequencing (Kircher et al., Reference Kircher, Sawyer and Meyer2012). Libraries were then sequenced across one lane of Illumina HiSeq 4000 in 80bp single-read mode.

DNA data processing

The raw DNA sequencing data were processed in a series of steps to remove contamination and ensure robust analyses were performed on authentic ancient DNA. First, the Illumina adapters used in sequencing were removed using AdapterRemoval/v2.3.1 (Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Lindgreen and Orlando2016) and the quality of the resultant trimmed reads was assessed with FastQC/v0.11.8a (Andrews, Reference Andrews2010). Trimmed reads for all samples were then processed with PRINSEQ/v0.20.4 to filter uninformative low-complexity sequences using the DUST algorithm (Schmieder and Edwards, Reference Schmieder and Edwards2011). To remove potential contaminant human DNA, reads were mapped against the human reference genome, hg38, using BWA/v0.7.17 (Li and Durbin, Reference Li and Durbin2009) with the seed (the length of the initial sequence used for alignment) disabled to improve read mapping for ancient DNA (Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Ginolhac, Lindgreen, Thompson, Al-Rasheid, Willerslev, Krogh and Orlando2012). Reads that did not map to the human genome were retained for further processing, using Samtools/v1.9 to select unmapped reads (Li et al., Reference Li, Handsaker, Wysoker, Fennell, Ruan, Homer, Marth, Abecasis and Durbin2009) and bedtools/v2.26.0 BamToFastq to convert to fastq format (Quinlan, Reference Quinlan2014). The non-human reads were then mapped to the wolf genome (Gopalakrishnan et al., Reference Gopalakrishnan, Samaniego Castruita, Sinding, Kuderna, Räikkönen, Petersen and Sicheritz-Ponten2017) using the previously described mapping strategy (Supplementary Table 10). PCR duplicates were removed using Picard/v2.6.0 (Broad Institute, 2019) and downstream analyses were limited to reads with a mapping quality ≥30 indicating few, if any, errors. Four methods were used to explore the authenticity of the aligned reads: DNA fragment length, ancient DNA damage signatures at the ends of the reads using mapDamage 2.0 (Jónsson et al., Reference Jónsson, Ginolhac, Schubert, Johnson and Orlando2013), read distribution across a genome of interest (Key et al., Reference Key, Posth, Krause, Herbig and Bos2017), and edit distance (Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Niemann, Iversen, Fotakis, Gopalakrishnan, Vågene and Pedersen2019).

Kinship analysis

To analyze the relatedness of the Tumat Puppies, the reads that aligned to the wolf reference genome were merged with previously published genome-wide sequencing data from Tumat-1 and Tumat-2 (Mak et al., Reference Mak, Gopalakrishnan, Carøe, Geng, Liu, Sinding and Kuderna2017; Bergström et al., Reference Bergström, Stanton, Taron, Frantz, Sinding, Ersmark and Pfrengle2022). Two approaches were used to evaluate kinship, one based on pseudo-haploid data using READ (Monroy Kuhn et al., Reference Monroy Kuhn, Jakobsson and Günther2018), the other a genotype likelihood method using NGSrelate/v20200904 (Hanghøj et al., Reference Hanghøj, Moltke, Andersen, Manica and Korneliussen2019) with the R 0/R 1 and KING-robust estimators described in Waples et al. (Reference Waples, Albrechtsen and Moltke2019). The expected values for the kinship estimators vary depending on the demographic history of the population, but such information is unavailable for the Tumat Puppies. Instead, a reference panel of unrelated and related canids, comprising genomic data from 5 Pleistocene wolves, 26 Eurasian grey wolves, 21 American grey wolves, and 11 Greenland village dogs (Supplementary Table 11) was compiled and used as a comparative dataset to enable the kinship analyses and interpret the results of the Tumat Puppies. The Greenland village dogs were included as an example of a small population size and a high level of inbreeding.

Metagenomic analysis of GI content

The sequencing reads that did not align to the human and wolf reference genomes were aligned to all available mitochondrial genomes (downloaded from NCBI on 14 May 2020) using MALT/v.0.4.1 (Vågene et al., Reference Vågene, Herbig, Campana, Robles García, Warinner, Sabin and Spyrou2018) and a Last Common Ancestor (LCA) analysis was performed in MEGAN/v6.19.4 (Huson et al., Reference Huson, Beier, Flade, Górska, El-Hadidi, Mitra, Ruscheweyh and Tappu2016). All species with a substantial number of matching reads (≥ 500) were considered to be “candidate species” and were subjected to further analysis to evaluate whether they were likely authentic. Specifically, the trimmed, non-human and non-wolf sequencing reads were mapped to the mitochondrial genomes of each candidate species, with a subsequent assessment of authenticity as described for the wolf DNA.

Results

Chronology

The mammoth bone from the Syalakh site yielded an age of 14,308–13,480 cal yr BP (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 1). Because other analyses indicate Tumat-1 and Tumat-2 must be contemporaneous with each other (see kinship results), OxCal’s R_Combine function was used to combine three dates associated with the canids (14,965–14,314, 14,309–14,046, and 14,823–14,171 cal yr BP) in an attempt to refine the chronology. This combination of dates yielded a posterior distribution of 14,799–14,204 cal yr BP, which overlaps with the mammoth and could be compatible with the canids living when the mammoth butchering site was in use. However, this posterior distribution should be considered unreliable, because a χ2-test implemented in OxCal fails at the 5% level, signifying that the three dates from the Tumat Puppies are in poor agreement. The lack of fit of the three dates may be due to contamination of recent carbon in a sample or another unrecognized issue, but ultimately this inconsistency limits the chronological resolution. Without a clear justification to favor one set of AMS results, the Tumat Puppies can be considered conservatively to date within the full range of the calibrated dates (i.e., 14,965–14,046 cal yr BP), and no conclusions can be drawn from the dating on whether the canids may have been contemporaneous with the mammoth.

Description and osteometry

Physical description

Both of the Tumat Puppies were female based on their external genitalia. Their bodies were mostly intact (Fig. 1, Supplementary Figs. 4–9), and measured 545 mm and 488 mm in length for Tumat-1 and Tumat-2 respectively, with tail lengths of 145 mm and 152 mm each. The ears and paws of both individuals were undamaged, and fur was preserved on both bodies. The fur was a monotone dark brown with no color phases except on the palms and plantar parts of the paws, where pale hairs were present (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 7). The fur was relatively short and downy, and long guard hairs were absent. According to Kennedy (Reference Kennedy1982), adult guard hairs of wolves are 100–145 mm long on the back and 24–96 mm long on the belly. Detailed descriptions of the two specimens along with further analysis of Tumat-1’s fur are available in the SI.

Osteometry

The skull of Tumat-1 has a total length of 127.1 mm, while the skull of Tumat-2 is 128.5 mm long (Fig. 5A, models are available, see Data Availability). The milk dentition of both Tumat Puppies had erupted and was at full stature, and the lower first molars were in the intra-mandibular phases of formation (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 8). No permanent teeth were visible, and the first lower premolar in both specimens had yet to reach the alveolar ridge.

The CL of the deciduous teeth from both Tumat Puppies were compared with those from milk dentition of recent dogs and wolves (Supplementary Table 3). Although there was a small overlap between the observed ranges (ORs) of all the milk teeth (except dp4) in dogs and wolves in the reference datasets, the means of the CL of the milk teeth of dogs were significantly smaller than those of wolves (Supplementary Table 3). In both Tumat Puppies, all measured deciduous teeth were larger than the lengths observed in the dog reference group, and within or larger than the recent wolves reference group (Supplementary Table 3). The exception is dp2, which falls within the OR of the recent dog references but is smaller than the OR of the wolf reference group.

It was not possible to estimate the adult CL of the first lower molars (m1) of Tumat-1 because the germs did not reach their completed lengths. In Tumat-2, the crowns were complete, and the length of the full-grown left molar was estimated to 26.73 mm, while the right was estimated to 25.15 mm. As such, the length of the left lower molar fell within the ranges of Paleolithic dogs and recent northern wolves, while the right lower molar fell in the OR of the Mesolithic Zhokhov dogs (Supplementary Table 4). Further details on the osteology and specific measurements are available in the SI.

Age at death

Mech (Reference Mech1970) observed that adult hairs appeared on the face of captive wolf pups at an age of 9 weeks and on the entire body at an age of 10 weeks. The absence of long, adult guard hairs on the face and body of the Tumat Puppies therefore suggested that they were younger than nine weeks at death. The completed eruption and full crown stature, the absence of shedding of the deciduous teeth, and the presence of an incompletely calcified crown of the lower carnassial further indicated that they were between seven and ten weeks of age at the time of death (Arnall, Reference Arnall1960; Shabestari et al., Reference Shabestari, Taylor and Angus1967; Esaka, Reference Esaka1982; Van den Broeck, Reference Van den Broeck2022; Van den Broeck et al., Reference Van den Broeck, De Bels, Duchateau and Cornillie2022). In combination, this provided an estimate that both specimens were at least seven, but less than nine weeks old when they died.

Stable isotope analysis

The δ13C values of the bone collagen, hair, and tissue samples from Tumat-1 varied with less than 1‰ (Supplementary Table 7), which is consistent with intra-tissue isotopic variability. The δ15N values (Supplementary Table 7) of the Tumat-1 bone collagen, ligament, and hair samples were identical (+8.0‰), while the skin sample produced the highest value (+9.4‰). The higher δ15N value obtained from skin provides the most recent isotopic information and likely reflects the ongoing consumption of mother’s milk, which mimics the δ15N enrichment observed in predators (e.g., Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Partridge, Stephenson, Farley and Robbins2001). For Tumat-2, the δ13C values obtained from hair and muscle samples were 1–3‰ lower than those measured in the rib and scapula collagen of the same individual (Supplementary Table 7), a phenomenon that is not uncommon in mammals (e.g. Fox-Dobbs et al., Reference Fox-Dobbs, Bump, Peterson, Fox and Koch2007; Caut et al., Reference Caut, Angulo and Courchamp2009). Although the δ15N values between the Tumat-2 tissues were comparable (Supplementary Table 7), the relatively high δ15N value in the muscle (+9.1‰) is likely linked to the consumption of mother’s milk, as with the skin sample from Tumat-1. The δ15N enrichment due to suckling may also account for the slightly higher δ15N values in rib collagen (+8.6‰) compared with scapula collagen (+8.3‰), resulting from potential higher collagen turnover in ribs. Although the most recently formed hair follicles also preserve the most recent isotopic values (e.g., Caut et al., Reference Caut, Angulo and Courchamp2009), the δ15N values from the hair samples of both individuals did not reflect those obtained from the soft tissues, suggesting that the youngest part of the hair was not submitted for analysis.

Feathers from the stomach content of Tumat-1 showed relatively low δ13C and high δ15N values (Fig. 6, Supplementary Table 7), which is consistent with a freshwater ecosystem (e.g., Symes and Woodborne, Reference Symes and Woodborne2010). The hair and skin samples from the same stomach content showed very different δ13C and δ15N values, which suggests they came from a different individual or possibly another species (Fig. 6, Supplementary Table 7).

Figure 6. Scatter plot of carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) isotope measurements taken from bone collagen of Late Pleistocene animals from northeastern Siberia. Note that the reconstructed values of the mother of the Tumat Puppies are comparable to measurements of the Ulakhan Sular canid. See Supplementary Table 7 for additional information and results for non-collagen samples.

The δ34S values measured on bone collagen, ligament, hair, and skin from Tumat-1 and bone collagen and hair from Tumat-2 varied from +3.0 to +4.0‰ (Supplementary Table 8), illustrating a relative homogeneity between the different tissues. Fractionation linked to trophic position is not expected in δ34S, leading to a relatively low intra-individual variability (Richards et al., Reference Richards, Fuller, Sponheimer, Robinson and Ayliffe2003; Tanz and Schmidt, Reference Tanz and Schmidt2010). The δ34S values observed in the Tumat Puppies are consistent with the local baseline of bioavailable sulfur in northeastern Siberia at the time, based on measurements from post-last glacial maximum (LGM) mammoth remains from the Bykovsky Peninsula (Arppe et al., Reference Arppe, Karhu, Vartanyan, Drucker, Etu-Sihvola and Bocherens2019).

Maternal prey choice

The measured δ13C and δ15N values of the Tumat Puppies and the reconstructed values of their mother are comparable to those of the Ulakhan Sular canid (Fig. 6, Supplementary Table 7), another post-LGM specimen geographically and morphometrically similar to the Tumat Puppies. The δ13C and δ15N values of the Berelekh mammoth remains are inconsistent with mammoth having constituted a significant proportion of the diet of the Tumat Puppies and their mother, due to lack of trophic enrichment in the canids compared to the mammoth. A large contribution from freshwater and marine ecosystems is also excluded. Instead, terrestrial ungulates, such as horse in combination with reindeer and possibly large bovids, likely comprised the majority of their diet (Supplementary Table 7).

Plant macrofossils

During dissection, the stomach contents of Tumat-1 and Tumat-2 were visually similar, consisting of a light-gray mass. Only Tumat-1 was fully thawed while Tumat-2 was not. As a result, identification of plant macrofossils was only carried out for Tumat-1. The most abundant remains were stems and leaves of grasses (Poaceae). A detailed inspection of the cellular structure of the plant suggests they belong to Calamagrostis sp. Several florets and achenes found within the stomach also belong to graminoids: Hordeum jubatum and Carex sect. Phacocystis cf. P. minuta (Fig. 7). Numerous twigs, two buds, and two almost complete leaves were identified as Salix sp. Complete shallowly lobed leaves belonging to Dryas octopetala were also observed. The only detected seeds were from Pedicularis cf. P. labradorica and Poa cf. P. arctica. Several moss species were observed within the sample. Invertebrate chitin remains were not abundant in the sample. Three complete elytra found in the stomach of Tumat-1 were identified as a dung-beetle, Aphodius sp.

Figure 7. Identified plant macrofossils found within stomach content of Tumat-1. (A, B) Leaves of Salix sp.; (C) bud of Salix sp.; (D) leaf of Dryas octopetala; (E) mosses; (F) spikelet of Hordeum jubatum; (G, H) spikelet and seed of Poa cf. P. arctica; (I) Carex sp. utricle. Scale bar indicates 1 mm.

Kinship analysis

DNA sequenced from seven GI samples of each Tumat Puppy contained 0.1–18.3% canid DNA (Supplementary Table 10), with C to T misincorporations varying between 4.5–13.8% in the first position, consistent with damaged DNA molecules. The total coverage on the wolf reference genome was low (0.005 and 0.150 × depth of coverage for Tumat-1 and Tumat-2, respectively) but in conjunction with published data from a tooth of Tumat-1 (Bergström et al., Reference Bergström, Stanton, Taron, Frantz, Sinding, Ersmark and Pfrengle2022) and soft tissues of Tumat-2 (Mak et al., Reference Mak, Gopalakrishnan, Carøe, Geng, Liu, Sinding and Kuderna2017), the genome-wide data (Tumat-1 = 0.46× and Tumat-2 = 5.77×) enabled a kinship analysis.

Using READ (Monroy Kuhn et al., Reference Monroy Kuhn, Jakobsson and Günther2018), P0 between pairs of individuals in the reference wolf and dog populations was calculated and compared to the expected distribution of P0 of unrelated individuals. The results showed that the distribution of P0 among Pleistocene wolves is close to that observed in modern grey wolves, thus these values can be used to identify relationships in Pleistocene canid populations. The P0 obtained for the Tumat Puppies falls outside the distribution of unrelated individuals and is similar to that obtained from three pairs of grey wolves with a full-sibling relationship (Fig. 8A).

Figure 8. Results of the kinship analyses. (A) READ results indicate that the Tumat Puppies share a full-sibling relationship. The histogram depicts the non-normalized pairwise distance (P0) estimated for different groups of canids, with points specifying P0 for relevant samples: the Tumat Puppies, three Eurasian grey wolves with a known full-sibling relationship (U1, U2, and U3), and American grey wolves with a known parent–offspring relationship (Yellowstone 2 is the offspring of Yellowstone 1 (mother) and Yellowstone 3 (father)). (B) NGSrelate estimates of R 0 and R 1 (top) describe identity-by-state genome-wide sharing patterns between pairs of individuals, while the KING-robust (middle) kinship coefficient measures the overall relatedness of each pair of individuals. In both plots, the Tumat Puppies fall near the theoretical expectations for half-siblings, and thus a half-sibling relationship is inferred. NGSrelate estimates of inbreeding coefficients F (bottom) indicate the Tumat Puppies have values similar to other Pleistocene wolves and modern Eurasian grey wolves, indicating that these populations provide appropriate comparative datasets for kinship analyses. FS = full-siblings, HS = half-siblings, PO = parent–offspring, UR = unrelated.

Using NGSrelate (Hanghøj et al., Reference Hanghøj, Moltke, Andersen, Manica and Korneliussen2019), R 0/R 1 and KING-robust kinship coefficients between pairs of samples were estimated, with Tumat-1 and Tumat-2 falling within the expected values for half-sibling relationships (Fig. 8B). Given that the expected R 0/R 1 and kinship coefficients can vary in highly inbred populations, NGSrelate was also used to estimate inbreeding coefficients. NGSrelate determined that the Tumat Puppies (Fa = 0.103613–0.120594) and most other Pleistocene wolves (Fa = 0.1006–0.525134) had inbreeding coefficients comparable to that of modern Eurasian grey wolves (Fa = 0.1006–0.6139).

The difference in kinship assignment between the READ and NGSrelate approaches is most likely due to the low depth of coverage of the Tumat-1 genome, which particularly affects NGSrelate (Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Brace and Barnes2023). It is further worth noting that kinship software packages are generally developed using human datasets, but demographic processes vary by species and allele frequencies from small reference panels may be inaccurate. Indeed, there are indications the allele frequencies of wolf populations may not be properly calibrated by NGSrelate, as the few individuals with known relationships do not exactly match theoretical expectations: the full-sibling relationships for U1, U2, and U3 individuals from Ree Park in Denmark have unexpectedly high values for R 1 and the parent–offspring relationships for individuals from Yellowstone National Park yield kinship coefficients that are similar to the values expected in unrelated pairs of individuals (Fig. 8B). Nonetheless, both approaches indicate that the Tumat Puppies share at least a half-sibling relationship.

Metagenomic analysis of GI content

The MALT analysis of unmapped reads identified 37 taxa that had at least 500 reads mapped to their mitochondrial genomes. This candidate list of eukaryotes was subjected to a series of authenticity checks to differentiate between closely related species and evaluate which taxa may have been present in the GI system of the Tumat Puppies (Supplementary Table 12, Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15). One of these species, wolf, was excluded from further analysis, because it had been confirmed previously and rather suggests the filtering of wolf DNA from the metagenomic dataset was not entirely successful. The assignment of reads from each subsample revealed that the stomach content had a heterogeneous composition (Supplementary Tables 12 and 13). Nine species of plants were detected in the T2:S5 and T2:CFM samples from Tumat-2, while another 20 plant species were found only in T2:CFM. Because the MEGAN LCA analysis revealed that the majority of assigned plant mitochondrial reads clustered at higher taxonomic levels (Supplementary Fig. 15) and given the complicated nature of plant mitochondrial phylogenies (Kowalczyk et al., Reference Kowalczyk, Staniszewski, Kamiñska, Domaradzki and Horecka2021), an expanded authentication of the limited plant DNA data was not pursued.

In contrast to the limited plant DNA data, GI samples from both Tumat individuals yielded tens of thousands of DNA molecules matching the mitochondrial genome of woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) (Supplementary Table 13, Supplementary Figs. 14–16). This is consistent with the previous recovery of a woolly rhinoceros mitochondrial genome from a single subsample of mummified tissue from the stomach of Tumat-1 (Lord et al., Reference Lord, Dussex, Kierczak, Díez-Del-Molino, Ryder, Stanton and Gilbert2020). Two subsamples contained reads assigned to the mitochondrial genome of the extant Indian rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis), but most failed to meet the minimum threshold for the edit distance, and all of the samples displayed an uneven read distribution despite high depth of coverage (Supplementary Table 13). In contrast, the reads that mapped to the woolly rhinoceros mitochondrial genome displayed a more even read distribution across the entire genome (Supplementary Table 13, Supplementary Fig. 16), and edit distances were consistent with a good match between the aligned reads and the reference. Five of the seven subsamples from Tumat-1 and four of the seven subsamples from Tumat-2 met authentication criteria for woolly rhinoceros.

Sequencing reads from the T1:S2 and T1:S4 subsamples were identified as closely related to four potential avian species by the MALT analysis (Supplementary Table 12, Supplementary Fig. 14): the white wagtail (Motacilla alba), the black-backed wagtail (Motacilla alba lugens), the grey wagtail (Motacilla cinerea), and the Hawaiian akikiki (Oreomystis bairdi). Although the Late Pleistocene range of these species is not known, several species of wagtails, including the white wagtail and the grey wagtail, have breeding ranges that include Siberia today. While the majority of these species have yet to have their mitochondrial genomes sequenced, the western yellow wagtail (Motacilla flava), another summer inhabitant of Yakutia, was directly added to our candidate bird species panel using NCBI entry MW929090. Following the mapping and authentication steps, the akikiki was rejected because the read distribution was highly uneven, with 52.3% of the mitochondrial genome without any coverage. In contrast, the mitochondrial genome of several wagtail species exhibited high and even coverage, as well as declining edit distances, which suggested a strong match between the reference genome and the data. The black-backed wagtail, the only non-resident of Siberia among the wagtail references, was a worse fit to the data, while the western yellow wagtail was found to have the highest mean depth of coverage (one sample reaching 152.0×), with 99.99% of positions represented. Although this indicates that the western yellow wagtail is the most likely candidate, the limited availability of wagtail reference genomes makes it difficult to conclusively identify which species of wagtail was eaten by Tumat-1.

Discussion

The multifaceted analyses performed in this study provide detailed and unique insight into the lives and deaths of the two Late Pleistocene canid mummies known as the Tumat Puppies. Their state of preservation, with largely intact bodies complete with downy, dark-brown fur, suggests that they were buried immediately after death. Based on their full stomachs, it is likely that they died rapidly, potentially due to a den collapse, similar to the scenario proposed for the Canadian Zhùr wolf pup mummy (Meachen et al., Reference Meachen, Wooller, Barst, Funck, Crann, Heath and Cassatt-Johnstone2020), or a landslide. Either event could account for the absence of traumatic injuries, however, it is interesting to note that this period was characterized by increased thermokarst activity (Walter et al., Reference Walter, Edwards, Grosse, Zimov and Chapin2007), and rapid thawing of organic-rich permafrost could have led to landslides. Both Tumat Puppies were females in similar stages of development, and, based on the length of the majority of their deciduous teeth, could be described as wolf-like in size. The presence of deciduous teeth, but the absence of adult guard hair, suggests that they perished 7–9 weeks after parturition (Arnall, Reference Arnall1960; Shabestari et al., Reference Shabestari, Taylor and Angus1967; Mech, Reference Mech1970; Esaka, Reference Esaka1982; Van den Broeck, Reference Van den Broeck2022; Van den Broeck et al., Reference Van den Broeck, De Bels, Duchateau and Cornillie2022). Although wolf pups can already consume solids when a little older than three weeks (Mech, Reference Mech2022), at 7–9 weeks, they start the transition from a milk-based diet to solids and begin eating regurgitated food provided by their mother and other pack members; they may even feed on small carcasses (Packard et al., Reference Packard, Mech and Ream1992; Packard, Reference Packard, Mech and Boitani2003, Reference Packard and Choe2019). The results of the stable-isotope and metagenomic analyses on the Tumat Puppies are consistent with the dietary changes undergone by wolf pups during this stage of development. The multi-isotopic analyses did not indicate advanced weaning in the recently formed soft tissues, while the metagenomic analysis, which provided a snapshot of their last meal, demonstrated that the Tumat Puppies were both eating solids.

The Tumat Puppies were found in the same location, and based on their visual similarities, it has been hypothesized that they were littermates. The results of the analyses performed in this study support this hypothesis. The genetic kinship analyses indicated that the canids were either half- or full-siblings (Fig. 8). A full-sibling relationship is arguably more likely given their comparable stage of development, the similarity of their diet, and what is known about modern wolf reproductive strategies. Both Tumat Puppies consumed woolly rhinoceros and although wagtail DNA was only detected in the stomach of Tumat-1, feathers were also recovered from Tumat-2 and included in the multi-isotopic analysis. In addition, no significant differences were found in the long-term dietary information recovered with stable isotope analysis. The inference that the Tumat Puppies were littermates is also consistent with present-day wolf pack composition. Wolf packs are territorial, multigenerational family groups. They can vary in size and complexity, depending on, for example, type and availability of prey. Pack complexity can also reflect pack size itself. Although large packs may include a second breeding pair, most often they are made up of one adult breeding pair and their offspring (Mech, Reference Mech1999; Tallian et al., Reference Tallian, Ciucci, Milleret, Smith, Stahler, Wikenros, Ordiz, Srinivasan and Würsig2023). Usually only one litter, comprising five to six pups on average, is born each season by the mother of the pack (Mech, Reference Mech1999; Stahler et al., Reference Stahler, MacNulty, Wayne, vonHoldt and Smith2013). In the Siberian tundra today, wolf pups are born between the second half of May and the beginning of June (Heptner et al., Reference Heptner, Naumov, Yurgenson, Sludskii, Chirkova and Bannikov1998), which is consistent with the presence of wagtail in the stomach content, because wagtails in Northern Eurasia breed in the Siberian tundra in the warmer months before migrating south for the winter (Winkler et al., Reference Winkler, Billerman, Lovette, Billerman, Keeney, Rodewald and Schulenberg2020).

The Tumat Puppies have previously been hypothesized to be early domestic dogs (Fedorov et al., Reference Fedorov, Garmaeva, Luginov, Grigoriev, Savvinov, Vasilev, Kirikov, Allentoft, Tikhonov, Kostopoulos, Vlachos and Tsoukala2014; Kandyba et al., Reference Kandyba, Fedorov, Dmitriev and Protodiakonov2015), because they were discovered at a potential butchering site containing burnt and cut mammoth bones (Supplementary Fig. 3). Although this tangential link to humans sets them apart from other proposed Siberian early dog remains, corroborative evidence is needed to firmly establish a connection between the canids and human activities. Unfortunately, currently available radiocarbon dates for the Tumat Puppies are not in close agreement and cannot be used to fully evaluate whether the butchered woolly mammoth remains were contemporaneous (Fig. 3). In contrast to the ambiguous chronology, the dietary analyses are more conclusive, with both the short- and long-term dietary reconstruction as performed in this study using metagenomics and stable isotope analyses suggesting that mammoth did not significantly contribute to the diet of the juveniles or their mother. Thus, there is no indication that the canids benefited from human activities, either by receiving food or by scavenging butchery sites. Rather than mammoth, the metagenomic analysis revealed that the last meal of the Tumat Puppies consisted of woolly rhinoceros and, in the case of Tumat-1, a wagtail.

Observational studies of present-day wolves show that during the summer while some members of the pack are engaged in pup-rearing activities, wolf packs tend to subsist on smaller prey and often hunt ungulate neonates (Tallian et al., Reference Tallian, Ciucci, Milleret, Smith, Stahler, Wikenros, Ordiz, Srinivasan and Würsig2023). Consumption of megafauna such as woolly rhinoceros could therefore be construed as unusual based on recent wolf ecology. Notably, however, the piece of woolly rhinoceros skin recovered from Tumat-1’s stomach (Supplementary Fig. 12) was covered in blond fur. Although little is known about the fur color changes of the woolly rhinoceros during their lifespan, Chernova et al. (Reference Chernova, Protopopov, Perfilova, Kirillova and Boeskorov2016) found that hair from the calf known as “Sasha” was considerably lighter than that of adult members of the species. This could suggest that the meat in the Tumat Puppies’ stomachs came from a woolly rhinoceros calf, which would coincide with present-day wolf hunting strategies that focus on juvenile prey (Tallian et al., Reference Tallian, Ciucci, Milleret, Smith, Stahler, Wikenros, Ordiz, Srinivasan and Würsig2023). In addition, the multi-isotopic dietary reconstruction predicted a generalist diet consisting primarily of terrestrial ungulates for the mother of the Tumat Puppies (Supplementary Table 7). Such a diet is consistent with the general trend observed in post-LGM large canids from Europe and eastern Beringia (Yeakel et al., Reference Yeakel, Guimarães, Bocherens and Koch2013; Bocherens, Reference Bocherens2015).

Although the Tumat Puppies inhabited a diverse landscape that was also occupied by humans (Sikora et al., Reference Sikora, Pitulko, Sousa, Allentoft, Vinner, Rasmussen and Margaryan2019), this study found no evidence that can conclusively link them to human activities. Arguments for early dog domestication require exceptional evidence, with a clear link between canid and human activities, but the results obtained here can be explained as Pleistocene wolf subsistence strategies and behavior. This interpretation supports previous DNA evidence that places the Tumat Puppies on an ancient wolf lineage that did not contribute to the diversity of modern dogs (Ramos-Madrigal et al., Reference Ramos-Madrigal, Sinding, Carøe, Mak, Niemann, Samaniego Castruita and Fedorov2021; Bergström et al., Reference Bergström, Stanton, Taron, Frantz, Sinding, Ersmark and Pfrengle2022). Thus, even if some canids from Late Pleistocene Siberia were supported by humans, the Tumat Puppies do not provide evidence for this process.

Beyond the question of domestication status, the results of the multifaceted analysis provide insights into the vegetation composition of the Tumat Puppies’ habitat. The radiocarbon dates of the two individuals fall on the transition from the Late Weichselian stadial (ca. 15,000–12,500 14C yr BP), as defined by Sher et al. (Reference Sher, Kuzmina, Kuznetsova and Sulerzhitsky2005), which is approximately 18,000–14,500 cal yr BP. Prior to the transition, Sher et al. (Reference Sher, Kuzmina, Kuznetsova and Sulerzhitsky2005) reconstructed a relatively mild but dry climate. This was followed by an increase in temperature and moisture that marked a major environmental change across the region, which led to widespread permafrost thaw (Sher et al., Reference Sher, Kuzmina, Kuznetsova and Sulerzhitsky2005; Walter et al., Reference Walter, Edwards, Grosse, Zimov and Chapin2007).

The mixture of plants retrieved from the stomach content of Tumat-1 suggests a heterogeneous vegetation consistent with the banks of a river or oxbow lake shore, and it is not inconsistent with any point in this period of climatic transition. The mixture of plants retrieved from the stomach content of Tumat-1 suggests a heterogeneous vegetation structure characterized by both dry and moist environments, which is consistent with the banks of a river or oxbow lake shore. Here, slope drainage would have made the slopes of the river terrace and oxbow lakes suitable for dry-tolerant vegetation such as Dryas octopetala (e.g., Vydrina et al., Reference Vydrina, Kurbatskiy and Polozhiy1988; Kienast et al., Reference Kienast, Tarasov, Schirrmeister, Grosse and Andreev2008, Reference Kienast, Wetterich, Kuzmina, Schirrmeister, Andreev, Tarasov, Nazarova, Kossler, Frolova and Kunitsky2011), while the floodplain would have provided conditions suitable for mesic vegetation, such as willow and the graminoids (grasses and sedges) that dominated the GI content.

While wolves are primarily carnivores, they have been observed to feed their young with berries (Homkes et al., Reference Homkes, Gable, Windels and Bump2020), and consumption of grasses is a common behavior of modern dogs (Bjone et al., Reference Bjone, Brown and Price2007). It is possible, therefore, that the plant material may have been consumed for dietary reasons, but it could also have been ingested during play or exploration of the environment. The environmental conditions also align with present-day white and yellow wagtail breeding ranges, which are characterized by positive air temperatures and include tundra, floodplains, and the shores of water bodies (Ryzhanovskiy, Reference Ryzhanovskiy2018).

The success of this project highlights the potential of employing recent methodological advances to expand our knowledge of the Tumat Puppies and other organisms preserved in permafrost. One blossoming area of biomolecular research is paleoproteomics (Warinner et al., Reference Warinner, Korzow Richter and Collins2022), through which mummified stomach tissue can be tested to infer more detailed dietary information (e.g., Grimm, Reference Grimm2021). For the Tumat Puppies, paleoproteomics could allow detection of beta-lactoglobulin to determine if they had consumed milk shortly before dying.

As advocated by Mann et al. (Reference Mann, Fellows Yates, Fagernäs, Austin, Nelson and Hofman2023) for dental calculus, DNA enrichment methodologies would enable a deeper analysis of dietary DNA, thereby refining taxonomic identifications and potentially leading to population-level analyses of Pleistocene flora and fauna. To facilitate such an analysis, genomic data from extant wagtail species would be invaluable to understand past canid diets and Pleistocene ecology. Likewise, expansion of wild plant DNA reference panels beyond chloroplast sequences would facilitate taxonomic identifications and potentially offer gene-level analyses to explore adaptive responses across glacial regimes. Finally, microbial DNA from mummified GI tracts could allow researchers to reconstruct ancestral microbiomes and elucidate millennia-scale evolution of the gut microbiome (e.g., Santiago-Rodriguez et al., Reference Santiago-Rodriguez, Fornaciari, Luciani, Dowd, Toranzos, Marota and Cano2015).

Conclusions

The Late Pleistocene Tumat Puppies have been an enigma in the search for the origins of dogs. While the canid pups fit the chronology of dog domestication and have previously been linked to human-modified woolly mammoth bones, this study suggests the most parsimonious interpretation is that they represent wolf littermates. This key inference is based on genetic data from the gut contents and stable isotopic signatures, neither of which indicate mammoth consumption either by the pups or their mother.

A possible link to humans was predicated on the proximity of the Tumat Puppies to butchered woolly mammoth bones, but our findings support an alternate interpretation that the individuals belong to a wolf population that did not contribute to the lineages that led to modern dogs. In addition to shedding light on the domestication status of the Tumat Puppies, this multifaceted study leveraged the exceptionally well-preserved remains to expand knowledge about the pups’ kinship and diets, and the environment of Northern Siberia in the Late Pleistocene.

Both pups were visually identified as female and genetic analysis revealed they are most likely littermates, which is consistent with sharing the same dietary components and being in a similar state of development, at seven to nine weeks of age. The gut contents revealed that the pups were already eating solids, including woolly rhinoceros and, in the case of Tumat-1, a wagtail, but isotopic composition of their soft tissues suggested they continued to consume some milk. In concert with the DNA data, plant microfossils demonstrated that the individuals inhabited a heterogeneous landscape that would have supported a range of flora and fauna. This work demonstrates the range of methods that can be applied to naturally mummified remains recovered from permafrost, as well as the potential of integrating disparate types of data to address controversial questions about Quaternary fauna.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/qua.2025.10.

Acknowledgments

A.K.W. Runge and J. Niemann were funded by the European Union’s EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation Horizon 2020 under Grant Agreement No. 676154. M. Sablin was supported by ZIN RAS (state assignment No. 122031100282-2). R. Losey was supported by SSHRC grant #G 435-2019-0706. Investigations by Alexander V. Kandyba were carried out as part of a government assignment to IAET SB RAS (Novosibirsk) No. FWZG-2024-0001. We thank Peter Tung and Valentina García-Huidobro (Senckenberg HEP, University of Tübingen) for their technical support in the analytical work for the isotope data. We express our appreciation to the Danish National High-throughput Sequencing Centre for assistance in generating the genomic sequencing data. The Viking cluster, which is a high-performance computing facility provided by the University of York, was used during this project. We are grateful for computational support from the University of York, IT Services and the Research IT team. Map data are copyrighted by OpenStreetMap contributors and available from https://www.openstreetmap.org. We sincerely thank the reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive feedback, which greatly improved this manuscript. We also extend our gratitude to the editorial team and in particular, acknowledge Mary Edwards for highlighting a possible connection between the formation of the Syalakh site and thermokarst activity.

Data availability

The metagenomic dataset generated for this study is available in the NCBI BioProject PRJNA1093083. 3D models based on CT scans: Tumat-1 (https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/tumat-cobaka-specimen-1-1cbd1e108be74c0dac02f93847b61c90), (https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/tumat-cobaka-specimen-1-9a5d5e7649a3405aacc1739ad2bdeaf1), and (https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/tumat-cobaka-specimen-1-f2992ebed7e6491b8687f850289566c4). Tumat-2 (https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/tumat-cobaka-specimen-2-e15b8b70ac924b518900c1b9c16091ca), (https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/tumat-cobaka-specimen-2-151e6d458e7446e6939c6b51f4e8e7e3), (https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/tumat-cobaka-specimen-2-f9c845cfa256477fa089e318683a2f99).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author contributions

The project was conceived by MHSS, SF, MTPG, AKWR, and NW. MG, MVdB, SF, JR, RL, and MS performed the descriptive and osteological analyses and interpreted the results. HB and DGD performed the elemental and isotopic analyses and interpreted the results. KB identified and interpreted the plant macrofossil analyses. AKWR, MHSS, and AL performed the genomic laboratory analyses of the GI content. JN, AKWR, NW and DS designed and performed the metagenomic bioinformatic analyses and interpreted the results. JR-M performed the kinship analysis and interpreted the results with input from SG. JS provided reference samples for the kinship analysis. AK interpreted the stratigraphy, and SF curated the archaeological material. AKWR and NW wrote the manuscript with input from MTPG, MG, DGD, HB, JR-M, KB and the other authors. All authors revised, edited and accepted the manuscript prior to publication.