Introduction

Recent years have witnessed an increasing acceptance and support for multilingualism in Pakistan. There is an emerging consensus among scholars, policy makers, and private stakeholders (e.g. British Council, Australian Center for Educational Research) for a multi-language policy in primary education (Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training 2018, 2022; Mahboob Reference Mahboob, Giri, Sharma and D'Angelo2020; Manan, Channa, & Haider Reference Manan, Channa and Haidar2022). What makes this multilingualism suspect is its celebration by the very forces that, until a few decades back, considered it to be a threat to national cohesion, and an impediment to modernization and economic development. Critical applied linguists have highlighted ideological continuities of celebratory discourses on multilingualism with the logics of coloniality that viewed languages as enumerable and bounded entities. These celebratory conceptualizations also mystify its contradictory character whereby it legitimizes only a few dominant languages, while it peripheralizes a vast number of indigenous languages and functions to reproduce hierarchical socioeconomic structures in society (Duchêne Reference Duchêne2020; Pennycook & Makoni Reference Pennycook and Makoni2020). Moreover, these framings conceal its complicity with the nation-state and neoliberal forces in producing dynamic and flexible subjects to serve the socioeconomic interests of the state and market forces. Some of the critical language scholars even suspect the metalanguage of sociolinguistics, including additive bi/multilingualism and codeswitching, as informed by colonial monoglossic ideologies, and argue that it warrants a decolonial reconceptualization associated with grassroots struggles for linguistic and social justice (Pennycook & Makoni Reference Pennycook and Makoni2020; Makoni, Severo, & Abdelhay Reference Makoni, Severo and Abdelhay2023).

In the present article, we examine the dominant framings of multilingualism from a southern perspective. In contrast to the celebratory stance that upholds multilingual education as a right and resource, we adopt a southern stance combined with the linguistic governmentality perspective to demystify the ideologies running through the dominant framings of multilingualism, and the politics of subject formation associated with the multilingualism of such current framings. In what follows, we first locate our stance in southern multilingualism and linguistic governmentality (Pennycook & Makoni Reference Pennycook and Makoni2020; Canagarajah Reference Canagarajah2022; Makoni, Kaiper-Marquez, & Mokwena Reference Makoni, Kaiper-Marquez, Mokwena, Makoni, Kaiper-Marquez and Mokwena2023) followed by a glance at South Asian linguistic governmentalities. Next, we present a brief history of shifts from a monolingual to multilingual language policy in Pakistan. Next, we analyze education and language policy discourses to examine the language ideologies that underpin the dominant framings of multilingualism, and the subject positions they entail. We conclude the article with academic and policy implications and propositions for combating linguistic governmentalities and redeeming the transformational power of multilingualism. The study aims to answer the following questions:

(i) What discourses and language ideologies underpin the dominant framings of multilingualism in education policy discourses in Pakistan?

(ii) How does the enactment of these policy discourses shape multilingual speakers’ linguistic experiences and identities and interpellate them into monolingual subject positions?

Southern multilingualisms and linguistic governmentalities

We combined southern multilingualisms and linguistic governmentality frameworks to examine the current framings of multilingualism in Pakistan. Southern multilingualism entails a broad translinguistic and transsemiotic view of communication situated in the lived realities of marginalized people in the Global South (Pennycook & Makoni Reference Pennycook and Makoni2020; Canagarajah Reference Canagarajah2022; Li Wei Reference Wei2023). This heteroglossic view of language encompasses a range of multilingualisms alternatively known as plurilingualism, metrolingualism, translanguaging, and translingualism (Canagarajah & Ashraf Reference Canagarajah and Ashraf2013; García & Li Wei Reference García and Wei2014; García & Otheguy Reference García and Otheguy2019). All of these theorizations are part of southern perspectives that emerged as a response to monolingual ideologies, and center on dynamic language practices in multilingual contexts. Yet in the present study, we prefer the term translingualism because it offers a theorization of grassroots multilingualisms in South Asia that involve fluid, flexible, and creative communicative practices where speakers constantly make strategic use of their linguistic, semiotic, and multimodal resources to (re)negotiate meaning, and configure and reconfigure their subjectivities and identities (Canagarajah Reference Canagarajah2022; Makoni, Kaiper-Marquez, & Mokwena Reference Makoni, Kaiper-Marquez, Mokwena, Makoni, Kaiper-Marquez and Mokwena2023). In its original conceptualization, translingualism was presented as an antithesis to monolingualism and as not susceptible to cooptation by dominant forces (García & Li Wei Reference García and Wei2014). However, recent studies have highlighted its transformative limits and pointed toward its academic and market uptakes that tend to blunt its transformative potential. Scholars also argue that its uncritical uptake might (in)advertently threaten indigenous communities’ struggles for linguistic rights (Duchêne Reference Duchêne2020; Canagarajah Reference Canagarajah2022; Li Wei Reference Wei2023). Critical scholars, therefore, argue for a need to unravel the linkages between multilingualism and subject formation in specific socioeconomic and political contexts (Duchêne Reference Duchêne2020; Flores Reference Flores, Rojo and Percio2020). Accordingly, we adopt a linguistic governmentality lens to examine the subject positions entailed in multilingualism's dominant conceptualizations, and its complicity in the production of neoliberal subjects.

Governmentality was first introduced by Foucault (Reference Foucault2004) as a form of power that operates mainly through the production and circulation of discourses and knowledges that shape individuals’ understanding of the self and guide their behavior. In critical applied linguistics, the terms language governmentality and linguistic governmentality have been used with slightly different foci: language governmentality has been used to examine the ways that changes in linguistic rationalities corresponded with shifts in economic and political rationalities, and the ways that the idea of language as a bounded system was used to discipline people's conduct in conformity with the interests of the nation-state and colonial empires (Pennycook Reference Pennycook2002; Flores Reference Flores, Rojo and Percio2020). Linguistic governmentality, by contrast, has focused mainly on the ways speakers are invested in shaping their linguistic conduct/competencies in alignment with the interests of the dominant nation-state and neoliberal institutions (Martín Rojo & Del Percio Reference Martín Rojo, Del Percio, Rojo and Percio2020; Urla Reference Urla, Rojo and Percio2020). In the present study, we operationalize linguistic governmentality as a synthesis to examine both the ways institutional discourses and knowledges promote a specific idea of multilingualism to constrain and manage linguistic diversity, and the ways speakers invest themselves in linguistic competencies desired by the state and the market forces.

Scholars engaging with the idea of governmentality have further classified it into nation-state/colonial governmentality and neoliberal governmentality (Flores Reference Flores2013; Canagarajah Reference Canagarajah2017; Martín Rojo & Del Percio Reference Martín Rojo, Del Percio, Rojo and Percio2020). Scholars argue that current conceptualizations of multilingualism are underpinned by monoglossic and raciolinguistic ideologies that were originally a part of the nation-state/colonial governmentality that invented the idea of a language as a disciplinary technique to control and manage linguistic diversity. This was achieved by imposing linguistic hierarchies with differential status and orders (e.g. official, national, regional) and exclusive functionalities (i.e. office, education, and home) for each. Consequently, this process inevitably led to otherizing and inviziblizing indigenous languages. While a few indigenous languages were officially acknowledged, a majority of them were relegated to obscurity (García & Li Wei Reference García and Wei2014; Canagarajah Reference Canagarajah2017; Flores Reference Flores, Flubacher and Percio2017; Duchêne Reference Duchêne2020; Pennycook & Makoni Reference Pennycook and Makoni2020; Rahman Reference Rahman, Giri, Sharma and Angelo2020; Shah Reference Shah2023). Similarly, raciolinguistic ideologies were centered on an idealized white male listening/speaking subject who created deficient populations and labelled their multilingual practices as non-standard, inappropriate, and unacademic (Flores & Rosa Reference Flores and Rosa2015). These ideologies involved a causal directionality between mastery over the language of the masters (e.g. English) and development, education, and upward social mobility. Thus, language as a bounded system was at the center of a system of racial and ethnographic differentiation of speakers based on their language practices.

Recent conceptualizations of multilingualism are informed by neoliberal resource orientations that view multilingualism as an asset, and make it complicit in the re/production of sociolinguistic hierarchies that multilingualism was originally meant to redress (Flores Reference Flores, Flubacher and Percio2017; Manan et al. Reference Manan, Channa and Haidar2022). At the heart of neoliberalism is the idea that the best outcomes will be achieved if the demand for and supply of goods and services are allowed to play out without interference by government forces. It operates through a set of strategies, including deregulation, privatization, and accumulation by dispossession with a relentless maximization of profit as the ultimate and only goal (Harvey Reference Harvey2003). The current framings of multilingualism as a resource form a part of neoliberal governmentality aimed at producing dynamic, flexible, English-speaking plurilingual subjects who live their lives in accordance with the dictates of market economy (Holborow Reference Holborow and Chapelle2015; Kubota Reference Kubota2016a, Reference Kubotab; Canagarajah Reference Canagarajah2017; Flores Reference Flores, Rojo and Percio2020; Martín Rojo & Del Percio Reference Martín Rojo, Del Percio, Rojo and Percio2020).

A glance at South Asian linguistic governmentalities

After the formal end of colonialism, the linguistic landscape in multilingual postcolonial societies was too complex to be reduced to only one language. The aim of linguistic governmentality in postcolonial societies was to produce bi/trilingual subjects and manage language diversity by maintaining the language of the former colonial masters, such as English, as the language of elite education, while deploying one (or two) indigenous languages for public education. This phenomenon is visible in language education policies in post/neocolonial settings, such as Pakistan, India, Hong Kong, Philippines, and South Korea (Canagarajah & Ashraf Reference Canagarajah and Ashraf2013; Piller & Cho Reference Piller and Cho2013; Lin Reference Lin, Wright, Boun and García2015; Manan, David, & Dumanig Reference Manan, David and Dumanig2016; Phyak & Sharma Reference Phyak and Sharma2021). For instance, while for about five decades after independence, nation-state/(post)colonial language governmentality remained dominant, neoliberal rationalities became hegemonic at the turn of the century (Tupas Reference Tupas, Mirhosseini and Costa2020; Sah Reference Sah2021; Sultana Reference Sultana2023; Majeed Reference Majeed, Zaidi and Harder2024). The present situation is characterized by a form of hierarchical additive multilingualism with strict boundaries among languages based on their political and economic value in a specific context.

In postcolonial contexts, linguistic governmentality is operationalized through the hierarchization and instrumentalization of linguistic functions, the otherization and invisibilization of indigenous languages, and the compartmentalization of languages at academic levels, respectively. At the policy level, it is conspicuous in the concurrent institutional support and legitimization of elite bi/multilingual education policies that privilege English as the medium of instruction (MOI), with customary support for a select few regional languages as library languages (Manan et al. Reference Manan, David and Dumanig2016; Rahman Reference Rahman, Giri, Sharma and Angelo2020; Bhattacharya & Mohanty Reference Bhattacharya, Mohanty, Rubdy and Tupas2021; Manan et al. Reference Manan, Channa and Haidar2022; Sah & Karki Reference Sah and Karki2023). Sah & Karki (Reference Sah and Karki2023) showed that school policies privileging English and Nepali over students’ mother tongue(s) are informed and shaped by nationalist ideology and market ethos; that is, the value ascribed to Nepali and English is associated with the agenda of producing subjects in alignment with both nationalist and market interests. They argue, ‘the neoliberal dispositions have decided on the bi/multilinguality of EMI schools as the use of languages other than English is idealized by neoliberalism and nationalism, creating a context of elite bi/multilingualism’ (Reference Sah and Karki2023:31). Studies conducted by Gautam (Reference Gautam2021) and his associates (i.e. Gautam & Poudel Reference Gautam and Poudel2022) have highlighted the paradoxical effects of the transition to democracy and neoliberalism with a ceremonial recognition and celebration of linguistic diversity and linguistic rights on the one hand, while reinforcing the status of English and Nepali as the dominant languages on the other. Similar concerns have also been raised in Bangladesh where studies have reported on a ‘fractured multilingual ecology’ (Sultana Reference Sultana2023:697), that is, rationalizing the hegemonic status of English and Bangla, and a systematic inviziblization of indigenous languages and communities (Chakma & Sultana Reference Chakma and Sultana2023). Studies from Bangladesh have also reported on postcolonial subjectivities that reject the colonial discourses of an essential nexus between development and English, and instead favor alternative discourses of development based on religion, Arabic, and indigenous languages (Chowdhury Reference Chowdhury2022).

At the academic level, linguistic governmentality can be noticed in the stringent institutional policies deployed to discipline students’ language behavior. Research has shown how educational institutions reproduce sociolinguistic hierarchies by enforcing English-only policies through disciplinary techniques involving rewards, penalties, occasional punishments, public shaming, and various other mechanisms to discipline students’ language practices in accordance with the colonial/neoliberal discourse of modernization and development (Bhattacharya Reference Bhattacharya2013; Manan et al. Reference Manan, David and Dumanig2016; Bhattacharya & Mohanty Reference Bhattacharya, Mohanty, Rubdy and Tupas2021; Sah & Karki Reference Sah and Karki2023; Manan, Tajik, Hajar, & Amin Reference Manan, Tajik, Hajar and Amin2023; Phyak Reference Phyak2024). Phyak's (Reference Phyak2024) study in Nepal revealed that both public and private schools exerted disciplinary power to implement English-only policy using panoptic, and postpanoptic measures, that is, vertical, horizontal, and intrapersonal techniques, involving self-censorship, criminalization, public shaming of students’ language behaviors, peer-policing, and discursive violence. Similarly, Manan and colleagues’ (Reference Manan, David and Dumanig2016) study in Pakistan reported the ways private schools implemented a strict English-medium policy by monitoring students’ language practices using disciplinary techniques involving surveillance, rewards, and punishment, and maintaining regimes of linguistic hierarchization and instrumentalization, delegitimization, and ghettoization of indigenous languages. This leads to an internalization of the differential functionalities and values among the student population who rationalize linguistic hierarchization with a strong preference for socially dominant languages over their mother tongue (Manan Reference Manan2024). In addition, national curricula also play a major part in nation-state and neoliberal governmentalities by perpetuating nationalist and neoliberal ideologies and reinforcing patriotic identities and entrepreneurial subjectivities (Lashari, Shah, & Memon Reference Lashari, Shah and Memon2023; Shah Reference Shah2023).

Regimes of postcolonial and neoliberal governmentalities in Pakistan

From a governmentality lens, Pakistan's language policy can be broadly classified into two phases: postcolonial and neoliberal, respectively. For us, postcolonial marks the political decolonization when the subcontinent rid itself of the colonial occupation but embraced colonial structures and ideologies. We hold a decolonial southern perspective that aims at a radical epistemological break with the ideologies of colonialism (Mignolo Reference Mignolo, Mignolo and Walsh2018). Language policy in its postcolonial phase (1947–1990) was inspired by the metadiscursive regimes of colonial modernity that deemed modernization and nation-building as inconceivable without English and Urdu respectively (Mahboob & Jain Reference Mahboob, Jain, García, Lin and May2017; Ayres Reference Ayres, Brown and Ganguly2003), while nearly seventy indigenous languages were deemed as unsuitable for the purposes of scientific education and economic growth (Rahman Reference Rahman, Giri, Sharma and Angelo2020). In education, Urdu was introduced as MOI in the government sector schools, while English was reserved for the elite private schools (Rahman Reference Rahman1997; Mahboob & Jain Reference Mahboob, Jain, García, Lin and May2017). The purpose was to produce an ideal national subject who was conceived as a bilingual individual capable of serving the national interests, for example, modernization and economic growth. This language policy was overtly based on the state's refusal to legitimize linguistic and cultural diversity, and therefore, conflicted with the demands of ethnic peripheries in both wings (Eastern and Western) of the country for democratizing the state structure, and for political, linguistic, and economic justice (Rahman Reference Rahman1997; Ayres Reference Ayres, Brown and Ganguly2003). Ethnic resistance to the state's homogenizing nationalist identity were articulated in political, literary, and cultural movements, such as Bhasha Andolan (the language movement) in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). Bhasha Andolan was a movement for recognizing Bangla language as a national language alongside Urdu. In the Sindh province, the resistance to the state's homogenizing identity was articulated in and through the political, literary, and cultural collectives, such as Sindhi Adabi Sangat (Sindhi literary fellows) and Bazm-e-Sufia-e-Sindh (Sindh Sufi Congregation) (Ayres Reference Ayres, Brown and Ganguly2003; Levesque Reference Levesque2021). These movements were, however, brutally suppressed until the separation of East Pakistan in 1971.

The conflict between the state's will and the ethnonationalist rationalities was resolved in favor of the former with the passage of the constitution in 1973. Article 251 of the 1973 Constitution of Pakistan stipulated that Urdu should be the (only) national language, while English would be the official language until arrangements were made for Urdu to replace English within fifteen years. As for the indigenous languages, the Constitution states, ‘without prejudice to the status of the National language, a Provincial Assembly may by law prescribe measures for the teaching, promotion and use of a provincial language in addition to the national language’ (National Assembly of Pakistan 1973:152–53). Thus, the constitution showed no compromise on the status of Urdu as the only national language but relegated the promotion of indigenous languages (about seventy of them) to the intent and will of the provincial assemblies.

The second phase, or the neoliberal phase, of language policy began with the processes of economic liberalization that started in the late 1980s but gained unprecedented momentum in the early 2000s. The past two decades have witnessed a rapid shift toward neoliberalism characterized by privatization, and deregulation of state-owned enterprises, and the growing influence of international funding agencies (IFAs), that is, International monetary fund (IMF) and the World Bank, and non-governmental organizations (Zaidi Reference Zaidi2015). Specifically, the liberalization of electronic media and the arrival of the internet and social media exerted a strong influence on language practices and linguistic rationalities. Thus, the political and economic rationalities, both globally and locally, created a new matrix of intelligibility that necessitated the production of ‘a new dynamically languaged elite class of English-speaking plurilingual subjects who are able to participate in the fluid linguistic practices’ (Flores Reference Flores, Flubacher and Percio2017:536). Education and language policy discourses are heavily infused with nation-state, that is, nation, language, culture, country, and neoliberal ideologies with words such as competition, globalization, free-market, human capital, human resource development, quality, jobs, and so on. For instance, policy discourses on education and language education as shown in the following excerpts derive their rationale from the global competition that serves as a central plank to ascribe differential status and functionalities to a selected group of named languages.

(1) Pakistan ranks 125th out of 140 economies on the Global Competitiveness Index 2018, far behind other South Asian economies and several other comparators such as Malaysia (24) and Indonesia (62). Pakistan faces significant skills shortages and mismatches, and there is a growing and as yet inadequately met demand for market-relevant, job-specific skills produced by the higher education and skills sectors, especially in emerging economic. sectors (National Education Policy Framework; Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training 2018:3–4)

(2) The advanced economies are investing in intellectual capital to produce highly skilled human resource. It is imperative for Pakistan to keep investing in higher education to make its economy knowledge-based for sustainable growth. (Annual Report 2021–2022; Higher Education Commission of Pakistan 2023:2)

By comparing Pakistan with advanced economies as shown in excerpt (1), the policy views competition as a virtue and guarantee of professional success (Martín Rojo & Del Percio Reference Martín Rojo, Del Percio, Rojo and Percio2020). These language and education policy discourses entail specific subject positions and behavioral models aligned with neoliberal governmentality that aim at cultivating human capital with knowledge and skills required both by national and global market-forces (see excerpt (2)). Consequently, language diversity and multilingualism have begun to feature in language policy documents as a resource and asset (National Education Policy Framework and Single National Curriculum; Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training 2018, 2022). Words such as multi-language proficiency, multilingually proficient (National Education Policy Framework; Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training 2018:10), and multilingual policy (National Curriculum Framework; Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training 2017a:68) can be noticed in education policy discourses. For example, the National Curriculum Framework (2017a) underscores the need for multilingual policy for education as a universally preferred model of education across the globe. This view squarely aligns with the neoliberal linguistic governmentalities. We examine the colonial and neoliberal ideologies underpinning this turn to multilingualism in language policy documents in the sections below.

Methodology, data, and analysis

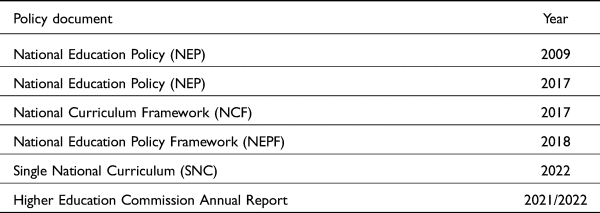

The present study drew upon data from two sources: Education policy documents published between 2009 and 2024, and narratives obtained from postgraduate students’ linguistic experiences. We combined critical policy studies (CPS) and narrative analysis to examine the language ideologies that underpin the current framings of multilingualism, their enactment in and through curriculum, and their tentative effects on multilingual speakers. The study employed critical policy studies (CPS) as a method of analyzing the policy documents in Pakistan. CPS attempts to understand policy processes not merely through their apparent inputs and outputs, but also their interests, values, and normative assumptions—both social and political—that shape and inform these processes (Fischer, Torgerson, Durnová, & Orsini Reference Fischer, Torgerson, Durnová, Orsini, Fischer, Torgerson, Durnová and Orsini2015; Torgerson Reference Torgerson, Fischer, Torgerson, Durnová and Orsini2015). CPS focuses on the discursive aspect of policy making to explain why particular policies are formulated and implemented. It therefore enables researchers to problematize a particular policy, practice, and regime by unraveling hegemony and power embedded in policy discourses (Howarth Reference Howarth2010). The data for the present analysis was obtained from the policy documents published on the website of the Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training and the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan. The Ministry is the government body responsible for planning, funding, regulating and implementing policies in educational institutions including the Higher Education Commission. In total, seven documents were selected for analysis (see Table 1 below).

Table 1. Official documents analyzed for review.

The documents that served as data sources included: the National Education Policies (NEP; Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training 2009, 2017b) that represent educational goals and lay out plans for their implementation; the Single National Curriculum (SNC; Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training 2022) proposed by the Ministry in 2020, which elaborates competencies, standards, benchmarks, and student learning objectives in line with the national education policy; the National Curriculum Framework (NCF; Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training 2017a) and the National Education Policy Framework (NEPF; Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training 2018), which served as the preamble to the SNC; and lastly, the Annual Report 2021–2022 by the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan (2023), which lays out the progress toward achieving the Commission's objectives up to 2022. Together these documents served to develop a coherent picture of the ideal subjects envisioned in the policy discourses.

In order to examine the ways these policies as enacted in government schools and colleges shape students’ language learning experiences and identities, we supplemented the data from CPS with a narrative analysis of the data obtained between 2021 and 2023 through language learning histories (LLHs) (n = 47) and interviews (n = 20). Narrative inquiry involves narrative analysis in which ‘storytelling serves as a means of analyzing data and presenting findings’ (Barkhuizen Reference Barkhuizen, Benson and Chik2014:3). The present narrative inquiry was conducted by the first author as part of a larger study that involved postgraduate students (n = 47) enrolled in the master of business program at a public sector university. Participants were required to write language learning histories (LLHs) at the start of the first semester of the two-year-long program, and were interviewed twice during that semester as per their convenience. The average duration of interviews with each participant was around two hours, while the length of LLHs varied between two and four pages. The LLHs and interviews allowed us to get a better understanding of the ways the monoglossic language policies were enacted in school and college, and the ways the experiences of multilingual speakers were discursively shaped at these ideological crossroads. Considering the word limit for the present article, we only present narratives from two participants, Shahmeer and Waseem (pseudonyms), to illustrate the subjectivation of students in and through the objectification of dominant discourses (see the section The making of plurimonolingual subjects). The first author had known the two participants for two years as the first author taught the course ‘Managerial communication’ in the first semester of the MBA program from 2017 to 2023.

Using reflexive thematic analysis (RTA; Braun & Clark Reference Braun and Clarke2006, Reference Braun and Clarke2019), each data source was read recursively to identify the themes. According to Braun & Clark (Reference Braun and Clarke2019:594), themes do not emerge passively from data, but rather are the product of a convergence between theoretical knowledge, analytical resources, and data. As part of RTA, our data analysis was informed by our theoretical affiliation with the decolonial and linguistic governmentality approaches that challenge the ideologies that constitute the colonial and neoliberal matrix of power within which multilingual speakers’ subjectivities are shaped. Following Braun & Clarke's (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) six-step data analysis, each document was read separately to identify and extract vocabulary (e.g. competition, human capital, resources) and excerpts that explicitly or implicitly referred to language policy, English, Urdu, indigenous languages, culture, or social, economic and political functions assigned to languages. This vocabulary (e.g. subthemes), as identified in the data, provided a means to understand how linguistic governmentality is enacted through policy and curriculum discourses and how participants’ narratives are informed by colonial and neoliberal rationalities. Consequently, our analysis led us to four major themes/discourses: (a) hierarchization of linguistic functions, (b) otherization and invisibilization of indigenous languages, (c) compartmentalization of languages in school curricula, and (d) the making of plurimonolingual subjects. We have discussed the first three discourses in relation to policy and curriculum discourses in the first section of the article, while the second section focuses on the participants’ narratives, explaining how plurimonolingual subjectivities emerge as a result of nation-state and (post)colonial governmentalities enacted through official policy and curricula. Specific attention was paid to the subject positions these discourses entailed, and the metadiscursive regimes, that is, nation-state/colonial and neoliberal, that underpinned these discourses.

Discourses and language ideologies underpinning the dominant framings of multilingualism

For almost five or so decades, language diversity was viewed as an impediment to nation-building and development, and language education policy was designed to control language diversity (Piller Reference Piller2016; Spolsky Reference Spolsky2021). In the post-liberal era, however, multilingualism is no more viewed as a problem but as a resource associated with the need for speakers to retain their linguistic resources and (be able to) participate in local and global competition. As part of nation-state/colonial and neoliberal governmentalities, the dominant framings of multilingualism are characterized by techniques, such as hierarchization of linguistic functions, otherization and inviziblization of indigenous languages, and compartmentalization of languages in school curricula. These techniques are meant to deliver plurimonolingual subjects that are capable of making efficient use of multiple languages recognized and valued by both the state and the market forces. We present the results of our documentary and narrative analyses in the sections below.

Hierarchization of linguistic functions

As part of the production of human capital, the dominant framings of multilingualism incorporate colonial language ideologies with a neoliberal resource-orientation. That is, this multilingualism embodies a hierarchical order of languages with exclusive political and socioeconomic functions that correspond with state nationalism and align with the needs of the local and global capital. Article 251 of the Constitution of Pakistan designates national status to Urdu, official status to English, and regional status to provincially dominant languages (i.e. Punjabi, Sindhi, Pashto, and Balochi) languages respectively. Heuristically, this implicit hierarchical status of languages can be mapped onto an imaginary pyramid divided into four layers, namely apex, super-central, central, and peripheral respectively (Piller Reference Piller2016). English occupies the apex due to its status as official language, and its association with local and imperial powers; Urdu resides in the super central part due to its solo status as national language and local lingua franca; local/regional languages, such as Punjabi, Pashto, Sindhi, and Balochi, hold the central position; however, nearly seventy indigenous languages are made to inhabit the bottom layer of the pyramid. The border between central and indigenous languages is blurred since, despite their status as regional languages, they are not preferred for MOI by the provincial authorities for formal education. These conceptualizations of multilingualism maintain those hierarchies and functions: English continues to be associated with the discourses of modernization, development, and literacy, while Urdu remains associated with the discourses of Islam and Muslim nationalism (Rahman Reference Rahman1997). Conversely, indigenous languages are implicitly associated with disempowerment and economic marginalization. These conceptualizations essentialize these linguistic functionalities by attributing languages exclusive functions: English as the vector of education and economic opportunities, Urdu as a language of national cohesion, and a few regional languages reserved for maintaining cultural heritage, as illustrated in the following excerpts.

(3) English language also works as one of the sources for social stratification between elite and non-elite. Combined with employment opportunities associated with proficiency of the English language the social attitudes have generated an across the board demand for learning English language in the country. (NEP; Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training 2009:27)

(4) Private schools predominantly use English as medium of instruction, with a very strong focus on active use of English language by children, while public sector schools mostly use Urdu and the regional, mother tongue as a language of instruction. Children with better English language skills tend to have more opportunities because of its glorified status in society and its use as a de facto official language. (NEPF; Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training 2018:3)

These excerpts highlight the ways colonial discourses about monolithic functionalities of English and vernacular languages are enveloped in the neoliberal lexicon. The official policy acknowledges English's role in social inequalities, yet at the same time it solidifies its position in the hierarchy of languages and allows it to colonize spaces—such as home, education, scholarship, and business—previously occupied by Urdu and regional languages. The entanglements of language policy discourse with colonial ideologies can also be observed in the causal directionality between English and education and upward social mobility, on the one hand, and an implied causal association between Urdu/regional language/mother tongue and poverty and social disparities on the other hand. The assumption is that democratizing the access to English language education, and promoting English proficiency will empower students, and automatically resolve the issues of illiteracy and socioeconomic disparities (Rahman Reference Rahman, Giri, Sharma and Angelo2020; Manan et al. Reference Manan, Tajik, Hajar and Amin2023). This, however, contradicts the evidence that shows that ‘English acts more as an exclusionary force than empowering in the highly polarized postcolonial societies such as Pakistan where the reasons of poverty, deprivation and unemployment are largely social, political, economic and structural than that of access or the lack thereof to English language’ (Manan Reference Manan2024:999). Phillipson (Reference Phillipson2008:34) rightly argues that ‘when English increasingly occupies territory that earlier was the preserve of national languages in Europe or Asia, what is occurring is linguistic capital accumulation over a period of time and in particular territories in favor of English’. Thus, linguistic capital accumulation on the part of the speakers of dominant languages inversely corresponds with the process of linguistic capital dispossession on the part of the speakers of the marginalized languages.

Otherization and invisiblization of indigenous languages

The dominant framings of multilingualism apparently acknowledge cultural and linguistic diversity and view them as a resource, yet at the same time otherize and invisiblize languages that resist cooptation or are not yet commodified and harnessed to the interests of the state or the market. This is aligned with nation-state/colonial and neoliberal governmentalities whereby languages that are supposedly incapable of delivering human capital, and unsuited to participate in global competition, are implicitly cast out from the policy and practice of education. This phenomenon can be noticed in the following excerpts.

(5) English is an international language, and important for competition in a globalized world order. Urdu is our national language that connects people all across Pakistan and is a symbol of national cohesion and integration. In addition, there are many other languages in the country that are markers of cultural richness and diversity. The challenge is that a child is able to carry forward the cultural assets and be, at the same time, able to compete nationally and internationally. (NEP; Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training 2009:11, emphasis added)

(6) Urdu and provincial languages of Pakistan are pivotal for maintaining national identity and integration of diverse linguistic and cultural groups in the country. (NCF; Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training 2017a:64)

In these excerpts, English is framed as a global lingua franca, Urdu is referred to as a national language, while more than seventy indigenous or vernacular languages have been lumped together under a single label as ‘other’. This otherization of indigenous languages reeks of a colonial monolingual habitus that precludes the possibility of national cohesion without a standardized national language and treats the vast majority of indigenous languages as unsuitable for national integration and civic and academic purposes. Consequently, this leads to differential institutional support and affects societal attitudes toward these languages (Mohanty Reference Mohanty, García, Skutnabb-Kangas and Torres-Guzmán2006; Majeed Reference Majeed, Zaidi and Harder2024). Multilingual speakers of marginalized languages experience differential access to academic and economic opportunities that are readily available to speakers of elite multilingualism, comprising languages of the state and the market (De Costa Reference De Costa2019). Consequently, multilingualisms of the marginalized and the elite are differently valued and rewarded. A number of studies on the nature and effects of multilingual education policies in the global South have pointed toward ‘multilingualism of unequals’ (Mohanty Reference Mohanty, García, Skutnabb-Kangas and Torres-Guzmán2006; Tupas Reference Tupas2015; Pervez Reference Pervez2023; Phyak Reference Phyak2024), and ‘inequalities of multilingualism’ characterized by ‘the symbolic and material dominance of some languages over other languages’ (Tupas Reference Tupas2015:89). In Tupas's (Reference Tupas2015:89) words, ‘cosmetic support of multilingualism and multilingual education does not diminish the insidiousness of ideologies and practices against it’.

It is also noteworthy that linguistic and cultural diversity are collocated with nation-state and neoliberal values of national integration and competition respectively. However, words such as cultural richness and diversity, and cultural assets imply a disembodied, neutral, and ahistoric understanding of culture that obfuscates its dynamic, hybrid, and contested nature. Culture is defined as a ‘collective memory bank of a people's experience in history’ (Thiongo Reference Thiongo1986:15), ‘a theatre where various political and ideological causes engage with each other’ (Said Reference Said1993:xiv). It seems ironical that at the same time as the language policy discourses acknowledge cultural diversity, they peripheralize and invisibilize the very languages that embody indigenous communities’ diverse ways of knowing, thinking, doing, and being in the world (Maldonado-Torres Reference Maldonado-Torres2007). This view of cultural diversity mystifies the history of indigenous contestations and struggles against linguistic homogeneity and socioeconomic injustice. In the context of Pakistan, for example, the ethnolinguistic movements in the former East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) and Sindh were quintessentially the struggles for inclusion and economic redistribution that not only demanded language and identity rights but also contested exploitation of their resources by the center.

Linguistic compartmentalization as hidden curriculum

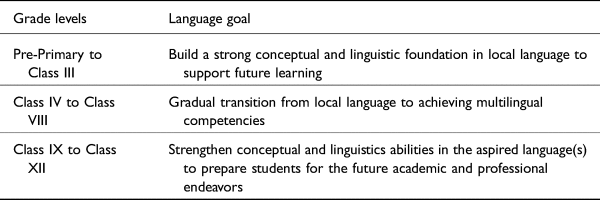

Pakistan's national curriculum provides a clear illustration of the ways linguistic governmentality is operationalized through a multilanguage policy with the explicit purpose of producing plurimonolingual subjects to cater to the needs of the state and the market. National curriculum functions as an ideological artifact and mode of objectification that entails subject positions aligned with the interests of the dominant socioeconomic and political forces (Apple Reference Apple1979; Piller Reference Piller2016). It embodies dominant discourses and language ideologies that legitimize the differential status of selected dominant languages and compartmentalize those languages into separate subjects and MOI across different levels of education, from higher secondary to tertiary and higher education. This is evident in the framing and operationalization of multilingual policy in the national curriculum documents (i.e. NCF and SNC; Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training 2017a, 2022). For instance, SNC ‘incorporates the local language, national language, and international and official language at various stages of the speakers’ educational journey to best support cognitive, academic, and social development’ (Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training 2022:32). Table 2 below illustrates the official conceptualization of multilingualism and the vision for its operationalization from primary to higher secondary education in Pakistan.

Table 2. Language in education policy goals (Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training 2022:34).

First, the sequential and transitory role of additive multilingualism is visible in the table. It is not clear what ‘local language’ refers to and/or whose language practices are referred to as ‘local’ since each province has a number of indigenous languages. It is also noteworthy that while the document proposes local languages, in practice, four out of five provinces use Urdu instead of local languages, such as Punjabi, Pashto, Kashmiri, or Balochi, as MOI in public sector schools. In addition, the perceived function of local language and multilingual competencies is to support learners’ transition to developing abilities in ‘aspired languages’ for academic and professional purposes. The ‘aspired language’ presumably refers to English since it is the MOI in intermediate as well as university education and is also the language for public and private sector professional opportunities in Pakistan. The progression clearly suggests a trend from additive (i.e. local languages and multilingual competencies) to restricted multilingualism (i.e. aspired language(s), such as English). In the broader scheme of things, multilingual competencies apparently serve instrumental functions of conceptual development and academic achievement up to matriculation. Multilingualism serves as an auxiliary to the English language and tends to be progressively redundant with regard to academic and professional purposes. SNC (Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training 2022:34, emphasis added) also proposes a hybrid method intended to facilitate ‘the students as they transition away from their local language(s) towards Urdu or English as the medium of instruction’. This transitional model entails instrumentality that views children's mother tongue and/or local languages as insufficient on their own for academic and professional purposes and as needing to be supplanted by English. Odugu & Lemieux (Reference Odugu and Lemieux2019:275) rightly note that ‘language use in multilingual contexts does not fit the rigidities of the discrete systems implicit in transitional multilingualism’. The transitional character of multilingualism entails a disincentivization of indigenous language use and a reinforcement of linguistic hierarchies based on their instrumental value in academia and the market (Odugu & Lemieux Reference Odugu and Lemieux2019).

The policy of strict separation between languages stands in stark contrast with the lived realities where children experience ‘early multilingual socialization and develop multilingualism as their first language’ (Mohanty Reference Mohanty, García, Skutnabb-Kangas and Torres-Guzmán2006:265). Mohanty (Reference Mohanty, García, Skutnabb-Kangas and Torres-Guzmán2006:264) argues that ‘The children who enter schools with these mother tongues are forced into a dominant language “submersion” education with a subtractive effect on their mother tongues’. Thus, schooling tends to produce subjects with plurilingual tongues but monolingual minds; that is, multilinguals schooled in believing in the ontological status and distinct functionalities and values of dominant named languages, while delegitimizing their own fluid translingual practices in real-life communication. We illustrate this phenomenon by presenting two narratives relating to Shahmeer and Waseem's sociolinguistic experiences.

The making of plurimonolingual subjects

Shahmeer

The first narrative is of Shahmeer who was enrolled in the MBA program of the university where the first author worked. Shahmeer was from a middle-class family in the Southern Punjab region. He identified himself as multilingual since he could speak Urdu, Rangri, Siraiki, Punjabi, and English with varying levels of competencies. He spoke Urdu as his home language, while he acquired Rangri because his family lived in a predominantly Siraiki-speaking and Rangri-speaking neighborhood in Southern Punjab. He loved the Rangri and Siraiki languages very much. According to him, ‘Siraiki is like khand [‘sugar’]. I spoke both Rangri and Siraiki with my friends, sometimes even at home with my siblings in my native town’. However, his love for Urdu, Rangri, and Siraiki was thwarted by familial, educational, and social factors: in his own words, his family ‘did not appreciate, rather strictly forbade any other language except Urdu at home’. More importantly, he experienced linguistic hierarchization and compartmentalization in school where he had to choose English or Urdu as the MOI. At his school, classroom interaction between teacher and students was supposed to be in either English or Urdu; that is, English-medium students were expected to use English for communication in class, while Urdu-medium students were supposed to use only Urdu inside class. Students could speak to teachers in any other language, for example, Siraiki and Rangri, outside the class. Furthermore, the demands made on students by school authorities for competency in Urdu and English gradually distanced him from developing proficiency in the languages he loved (i.e. Siraiki and Rangri). Initially enrolled in an English-medium section, he had to switch to the Urdu-medium section because of his lack of proficiency in English. His decision to shift to the Urdu-medium section was not appreciated by his family initially. However, the family agreed only when his teachers reassured his family that ‘he is good at other subjects but English. Once he overcame his deficiency in English, he would be alright’. These experiences with English led him to invest himself in mastering the English language, and English proficiency. By the time he completed his intermediate, he had already started imbibing dominant colonial and neoliberal language ideologies whereby Urdu and English were indexed as the language of culture and education, respectively. That is, he felt proud of his refined Urdu and his better proficiency in English. He stated,

Even my friends could feel I was not the same Shahmeer since I could speak saaf [‘refined’; i.e. without mixing Rangri or Siraiki words] Urdu. I could get a sense of becoming more civilized. We sound more cultured when we speak Urdu. Using English words while speaking Urdu gives out an impression of my being educated.

This statement clearly highlights the ways Shahmeer's multilingual identity gradually succumbed to a monoglossic sense of self shaped by indexicalities (i.e. refined and pure language, civilized, cultured, educated) located within colonial and neoliberal ideologies. From class 9 up to class 12, he developed a keen interest in Urdu fiction and composed his own poetry in Urdu. However, he had to give up this activity because, in his words, ‘I had to focus on my career, and English took the center stage in my life as I had to pass the entrance exams to get admission to university’. This statement highlights the influence of neoliberal ideologies and a corresponding linguistic entrepreneurship whereby he was invested in learning English at the expense of the languages he loved and lost his passion for artistic pursuits like poetry. The gradual erasure of his multilingual identity and his artistic pursuits could be attributed to his experiences with hierarchization, compartmentalization, and commodification of linguistic competencies.

Waseem

Waseem was born in 1999 in a village near Moro in the Sindh province. He spoke Sindhi as his home language and started developing auditory proficiency in Urdu, Siraiki, and Punjabi in early childhood due to his exposure to television programs and Siraiki -and Punjabi-speaking friends. He formally started learning Urdu in a private school (grades 1–5). He stated that his cousin and he were the only Sindhi-speaking students while a majority of the class spoke Urdu as their mother tongue. His friends and teachers used to speak in Urdu. Since he was the monitor (class leader), he was laughed at by his classmates for his Sindhi accent. At that time, he believed that ‘Urdu was the most important language of all’. He developed a patriotic feeling towards Urdu as he was told by his teachers that Urdu was the national language of the country. From grades 6 to 10, he studied in a Sindhi-medium government school where all subjects, except for English and Urdu, were taught in Sindhi. In this school, he developed a love for his mother tongue and Sindhi literature so much so that for him there was no better language than Sindhi. He learned the nuances of his mother tongue, such as grammatical structures and vocabulary, more carefully than before. He was introduced to indigenous literature, such as the poetry of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, and the literary diction in this school. According to Waseem, this was the time when he would get confused whether to think in Urdu or in Sindhi.

In college (grades 11–12), Waseem's education transitioned from Sindhi to English medium. He faced difficulties with comprehending science subjects, writing assignments, and doing class presentations in English. According to Waseem, ‘I was ridiculed by teachers for writing tooti-phooti [‘broken/non-standard’] English’. He recounted an incident about his cousin who was excellent at mathematics but was ridiculed by his classmates for mispronouncing a word in English in a way that it sounded like a gaali ‘swear word’ in Sindhi. In one of his own presentations, he lost his nerve and fainted because of lack of confidence in English and was made fun of by his classmates. He stated that ‘this happened because I was weak at English. I was good at mathematics, and science subjects, so I thought I would do well in English too. I worked very hard for the presentation but could not deliver it well. So I got very very depressed and fainted’. He also admitted to a fear of an accent and felt the need to speak like a native English speaker. He was taunted by a teacher for his accented English. The teacher remarked, ‘you even speak English in a Sindhi accent’. The teacher himself spoke English in an Anglo-American style and expected students to model their pronunciations on his accent. Thus, Waseem used to emulate his teacher's accent. According to him, there was a great deal of focus on ‘prepositions, adjectives, and adverbs’, that is, on accuracy rather than fluency. It is interesting that, despite these horrible experiences, he never lost his fascination with English. He stated, ‘I still find English so attractive; when I speak English or mix English words in Urdu or Sindhi, I feel like a Fanne khan [‘Lord; Swagger’]. Sometimes I even unwittingly code-switch to English in my Dua [‘prayers’]’. During his preparation for university entrance exams, his English teachers focused exclusively on grammar and tenses and sentence structures, and recommended grammar books to improve students’ English grammar. In response to a question about whether he felt English had influenced his multilingual proficiency, Waseem revealed,

Mostly my readings are in English. I have lost touch with Urdu. I find it difficult to read text in Urdu. As for Sindhi, I haven't read books in Sindhi for a very long time. An example of this is that I use English where I am expected to speak Sindhi, like at home, friends circle, or in an unexpected situation.

Waseem's beliefs about languages and subjectivities were shaped within and by the academic institutions he studied in. Discourses associated with different languages—such as Urdu as a national language, Sindhi as a mother tongue, and English as the language of education—employment, and opportunities informed his behavior toward these languages. These competing linguistic demands and linguistic disciplining in school/college affected Waseem's self-perception and identity and changed his attitude toward multilingualism since, in his view, ‘multilingualism creates confusion’. Like Shameer, Waseem also experienced differential academic and social valorization of languages with different emotional and political values attached to each one of them.

These narratives clearly indicate the ways postcolonial nation-state and neoliberal language ideologies—that is, hierarchization of linguistic functionalities, otherization, and compartmentalization—are enacted in and through a complex intersection of discourses and consequently interpellate multilingual speakers into plurimonolingual subject positions aligned with nation-state and neoliberal interests (Piller Reference Piller2016; Pennycook & Makoni Reference Pennycook and Makoni2020). The effects of the transitional character of multilingualism in education can be observed in the voluntary withdrawal of multilingual speakers from creative pursuits in indigenous languages in favor of language investment in dominant languages (Manan Reference Manan2024). Waseem and Shahmeer's love for their respective mother tongue (i.e. Sindhi & Urdu), and local languages (i.e. Siraiki & Rangri) revealed temporary cracks in dominant ideologies and showed possibilities of their developing alternative subjectivities. However, this was suppressed by the obligations of linguistic entrepreneurship discursively imposed by the state and the market.

Conclusion and implications

The framings and enactment of multilingualism entail deleterious effects and exert epistemic and symbolic violence on speakers’ linguistic repertoire and language diversity (Pennycook & Makoni Reference Pennycook and Makoni2020). Studies in post/neocolonial settings have shown that hierarchical English-dominated multilingualism reinforces the ghettoization and racialization of minoritized languages, makes their learning redundant or consigns them to private use (Tollefson Reference Tollefson2015; Tupas Reference Tupas2015; Manan et al. Reference Manan, David and Dumanig2016). This leads to the epistemicide and grand erasure of experiences of marginalized indigenous people (Phyak Reference Phyak and De Costa2021; Makoni, Severo, & Abdelhay Reference Makoni, Severo and Abdelhay2023). One of the first steps toward a transformative reconceptualization of multilingualism is to do away with the colonial epistemologies involving monoglossic and raciolinguistic ideologies based on the categories of maternality, native speaker, and white male listening/speaking subject (Bonfiglio Reference Bonfiglio2010; Flores & Rosa Reference Flores and Rosa2015). These categories serve as tools for compartmentalizing languages into standard and vernacular, and consequently contribute to racializing speakers into native and non-native, proficient and deficient, based on their conformity or otherwise from the so-called mythical standards (Majeed Reference Majeed, Zaidi and Harder2024). The idea of language as a fixed bounded entity with the figure of native speaker at its center functions as an affective regime that is employed by the dominant forces as an instrument for legitimizing their dividing practices. Such practices produce legitimate and deficient speakers, and central and peripheral multilingualisms, which in turn reproduce unequal linguistic and socioeconomic hierarchies. In response to hierarchical elite multilingualism, critical linguists, teachers, and teacher educators need to adopt a situated approach that takes into account the entire economy of linguistic exchanges, that is, ‘the complex interactive structure that all linguistic performances form in a particular society’ as their point of departure (Kaviraj Reference Kaviraj, Zaid and Harder2024:142).

Shameer's and Waseem's narratives showed how linguistic rationalities and subjectivities of multilingual students were shaped within affective regimes of linguistic entrepreneurship aligned with logics of colonial and neoliberal governmentality. The linguistic differentiation embedded in curricula and textbooks, and embodied in pedagogical practices, inculcate in students a linguistic habitus that impels them to compromise on their artistic pursuits; instead, they shape themselves in the image of idealized human capital: that is, they transform themselves from being-for-themselves to being-for-others. This can be challenged by promoting critical language awareness and reflective activism (Phyak & De Costa Reference Phyak and De Costa2021) among teachers and students regarding the political/ideological character of languages, and the ways linguistic compartmentalization racializes populations and reproduces hierarchical socioeconomic structures. Teachers can foster metalinguistic and critical awareness by enabling students to understand the historicity of bounded notions of language, and the hybrid, translingual, and performative nature of communication. In addition, teachers can encourage students’ literary pursuits in their mother tongue (e.g. Waseem) and other indigenous (e.g. Shahmeer) languages to resist monolingual hegemony and neoliberal identity.

Another important step is to challenge the state-mandated linguistic hierarchies based on a bi/trilingual formula that restricts linguistic diversity to politically and globally dominant languages based on their differential market value. In a Pakistani context, English and Urdu, along with a regional language, are accorded legitimacy—and funding and assistance—while nearly seventy named languages are invisibilized. The unequal status of languages tends to foster unequal multilingualism in society (Gautam & Poudel Reference Gautam and Poudel2022; Majeed Reference Majeed, Zaidi and Harder2024; Phyak Reference Phyak2024). In order to resist elite multilingualism, critical applied linguists need to promote and participate in local struggles demanding equal status for marginalized indigenous languages (De Costa Reference De Costa2019; Phyak & Sharma Reference Phyak and Sharma2021). In Phyak & De Costa's (Reference Phyak and De Costa2021:239) words, ‘efforts towards reclaiming the space for Indigenous languages should be grounded in the critical historical awareness, collective activism, cultural practices, and place-based pedagogies of indigenous communities’. At a policy level, instead of an approach that surrenders to neoliberal logics, a situated approach is needed that takes into account the lived realities and aspirations of local people and the sociolinguistic and political complexities in each locality. In Pakistan, provincial governments can adopt a language education policy that embraces linguistic diversity without threatening erasure of indigenous and marginalized languages, and/or jeopardizing the perceived linguistic identities of marginalized people. This can be achieved by taking local communities on board in policy making and working with them to materialize their aspirations before introducing language (in) education policy.

We conclude this piece by joining in the voices from the global south for the need to decolonize multilingualism that first and foremost requires epistemic disobedience to logics of coloniality including monoglossic and raciolinguistic ideologies (Tupas Reference Tupas2015; Mignolo Reference Mignolo, Mignolo and Walsh2018; Pennycook & Makoni Reference Pennycook and Makoni2020; Phyak & De Costa Reference Phyak and De Costa2021; Canagarajah Reference Canagarajah2022; Manan et al. Reference Manan, Tajik, Hajar and Amin2023; Makoni, Kaiper-Marquez, & Mokwena Reference Makoni, Kaiper-Marquez, Mokwena, Makoni, Kaiper-Marquez and Mokwena2023; Syed Reference Syed2024). It requires ‘creating a new metalanguage from the local linguistic landscape’ (Makoni, Kaiper-Marquez, & Mokwena Reference Makoni, Kaiper-Marquez, Mokwena, Makoni, Kaiper-Marquez and Mokwena2023:5). As decolonial scholars from the global south, we support grassroots multilingualism that is central to communities’ liberatory praxis: a multilingualism that is at the center of marginalized communities’ quotidian struggles against local manifestations of linguistic rights, patriarchy, state violence, and neoliberal enclosures. As long as education is framed in neoliberal logics where it is part of the production of human capital that serves trans/national capital, multilingualism and other associated notions, such as translingualism, will remain vulnerable to appropriation by unjust forces (Canagarajah Reference Canagarajah2022). Decolonizing multilingualism is inconceivable without a corresponding decolonization of school, education, and society. Lastly, this study was specifically meant to problematize the dominant framings of multilingualism and raise a caution against its uncritical uptake in Pakistan and elsewhere. We understand the limitations of this study and do not assume a direct causality between language education policy discourses and students’ subjectivities. We emphasize the need for more situated longitudinal ethnographic studies to examine the influences of metadiscursive regimes within which students’ subjectivities are shaped and/or transformed.