The ageing population is increasing, with more people experiencing old age and living longer than ever before(Reference Leon1). The UN estimates that the proportion of people aged 60 years and above will reach over 2 billion by 2050 worldwide(2). Ageing is associated with functional declines and an increased risk of several age-related chronic diseases(Reference Beard, Officer and De Carvalho3). Therefore, supporting healthy ageing is crucial to reduce the healthcare costs and socioeconomic burden of treating age-related disabilities and chronic conditions(Reference Beard, Officer and De Carvalho3,Reference Lopreite and Mauro4) .

Although ageing is commonly viewed as a chronological process(Reference Maltoni, Ravaioli and Bronte5), it does not accurately reflect the actual biological and physiological declines due to the accumulation of cellular damage(Reference Levine6). For this reason, biological ageing is considered to be more relevant in medical research as it represents the changes at the cellular level, impacting the organs, bodily systems and overall physiology of the body(Reference Rollandi, Chiesa and Sacchi7). Cellular senescence, characterised by permanent cell cycle arrest, is a leading phenomenon driving biological ageing. The accumulation of senescent cells is associated with loss of organ and tissue function(Reference Kwon and Belsky8) and subsequently age-related diseases(Reference LeBrasseur, Tchkonia and Kirkland9). Cellular senescence is predominantly driven by the shortening of telomeres, which are the nucleoprotein structures located at the end of chromosomes, protecting DNA structure and integrity(Reference Victorelli and Passos10). Telomeres gradually shorten during each cell division, and as they reach a critical length, cell proliferation completely ceases, causing cellular senescence or apoptosis(Reference Greider11,Reference Srinivas, Rachakonda and Kumar12) . Therefore, telomere length is regarded as a biomarker of ageing. Shorter telomere length is associated with a higher risk of age-related chronic diseases and mortality(Reference Müezzinler, Zaineddin and Brenner13–Reference Wang, Zhan and Pedersen15).

Various internal factors during ageing, such as oxidative stress, inflammation and immune deficiency, can accelerate the shortening of telomere length(Reference Omidifar, Moghadami and Mousavi16,Reference Kawanishi and Oikawa17) . These internal factors can be modulated by lifestyle factors including dietary intake, exercise, alcohol consumption and smoking(Reference Aseervatham, Sivasudha and Jeyadevi18). From a nutrition perspective, diets characterised by high saturated fat intake, meat consumption and Western dietary patterns have been linked to shorter telomeres(Reference Freitas-Simoes, Ros and Sala-Vila19). Conversely, Mediterranean diets, vegetable and fruit intake and dietary components that reduce oxidative stress and inflammation have been shown to decelerate telomere shortening(Reference Galiè, Canudas and Muralidharan20,Reference Hu21) .

Albeit often considered as separate food types, nuts and seeds have comparable nutrient profiles(Reference George, Daly and Tey22), and they are rich in protein, unsaturated fats and, more importantly, vitamins, minerals and phytonutrients that act as antioxidants that combat inflammation and oxidative stress in the body(Reference Blomhoff, Carlsen and Andersen23). Therefore, it is highly plausible that nut and seed intake may protect against telomere attrition. Evidence from previous research suggests that dietary patterns that emphasise nuts and seeds were related to longer telomere length(Reference Galiè, Canudas and Muralidharan20), but these associations cannot be attributed specifically to nut and seed intake. Therefore, a systematic review exploring the specific effects of nuts and seeds on telomere length is warranted. Although a previous review has explored a somewhat similar topic, it was conducted as a narrative review, and it did not include seed intake(Reference Tan, Tey and Brown24). Therefore, the aim of this systematic review is to evaluate the role of nut and seed intake on telomere length using the evidence generated from observational and interventional studies.

Methods

Search strategy

Four databases, that is, Medline, CINAHL, Embase and Web of Science, were systematically searched from inception to 12 March 2024. The search strategy was developed in consultation with a liaison librarian (Faculty of Health, Deakin University, Australia), and the themes used included nuts or seeds, telomere length or biological ageing. An example of a line-by-line search is provided in the online Supplementary Table 1. Truncation and alternative spellings were included in the search terms to maximise the results. A further snowball search was conducted to identify additional articles from other relevant systematic reviews, which may have been missed in the original systematic literature search. The protocol for this systematic review was registered with PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42024501688) and reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (2020)(Reference Page, Moher and Bossuyt25).

Study selection criteria

Both observational (e.g. cross-sectional, case-control and prospective longitudinal studies) and interventional (e.g. randomised, controlled trials) studies were eligible for inclusion in this systematic review. Studies were eligible if they assessed intake of nuts or seeds, applied nut or seed interventions and measured telomere length as an outcome in adult human participants (aged ≥ 18 years). No exclusions were applied for studies that included participants with overweight or with common metabolic diseases such as diabetes, high blood cholesterol and hypertension. Studies were deemed ineligible if they included participants who were pregnant or had genetic or inborn metabolic disorders that influenced telomere outcomes. Studies on the intake or interventions involving coconuts, chestnuts or cacao were excluded due to their significantly different nutrient composition compared with other tree nuts and peanuts(Reference George, Daly and Tey22). Exclusions were also applied if the studies assessed the isolated components of nuts or seeds, such as extracts, oil (e.g. sunflower oil), flour, etc. Studies were excluded if telomere length outcomes could not reasonably be attributed to nut or seed intake, for example, when nuts or seeds formed part of a broader dietary pattern and no specific nut or seed intervention arm was present. Review articles and animal or in vitro studies were excluded. The original studies meeting the above criteria and published in English with an available full text were included.

Screening and data extraction

All the studies retrieved from the database search were uploaded to Covidence (Melbourne, VIC, Australia), an online tool streamlining the systematic review process. After removing duplicates, all studies were independently assessed for eligibility by two reviewers independently (MB, MP, MED, CD, OG, MW or VT), screening through titles and abstracts, followed by the full text. The conflicts were resolved by a third assessor when consensus could not be reached among the first two assessors. Data from the included articles were extracted by one reviewer (MB, MP, MED, CD, OG, MW or VT) and verified by another reviewer (SYT or JH). Studies were stratified based on observational and interventional design, and two separate data extraction tables were developed. Data extracted from observational studies included author, year, country, study design, study population, age (years), BMI (kg/m2), sample size, male/female distribution, types of nuts/seeds assessed, dietary assessment methods, telomere length measurement methods and main findings on the telomere length outcome. Data extracted from interventional studies additionally included sample size and demographic details for participants in the control and intervention arms, the duration, type, form and dose of nut/seed intervention and the control.

Quality and risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias and quality assessment of the included studies were performed independently by two assessors using the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Evidence Analysis Library® November 2022: Quality Criteria Checklist tool on Primary Research(26). This checklist evaluated the relevance (four questions) and validity (ten questions) of the studies. Based on the ratings of these fourteen questions, each article is assigned a quality rating of negative, neutral or positive. If all relevance questions were rated as ‘yes’ and most (six questions or more) of the validity questions were rated as ‘yes’, the article was given a positive rating. If the answer to any of the four relevance questions was rated a ‘no’ but ‘yes’ was indicated in six or more validity questions, the article was then given a neutral rating. If most (six or more) of the validity was rated as ‘no’, the article was assigned a negative rating.

Results

Study selection and study quality

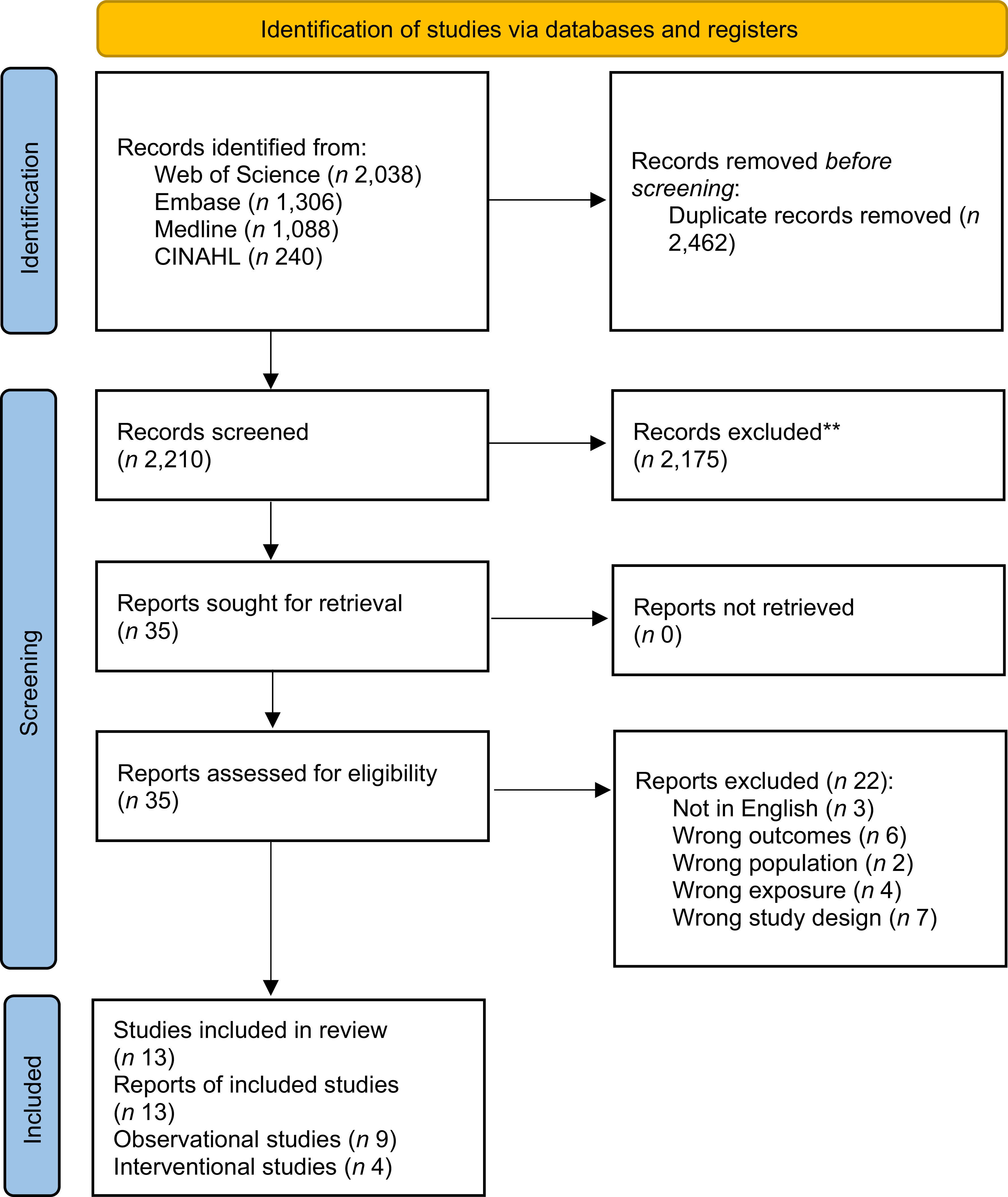

The systematic literature search yielded 4672 articles in total. After removing duplicates, 2210 articles were screened for titles and abstracts, and thirty-five articles were identified for full-text screening, of which eleven articles met all inclusion criteria. Two additional articles were identified through a snowball search, resulting in thirteen articles being included in this systematic review. Figure 1 shows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of the selected articles. Of the thirteen studies included, nine studies were of observational study design(Reference Chan, Woo and Suen27–Reference Zhou, Zhu and Cui35), and four were interventional studies(Reference Canudas, Hernández-Alonso and Galié36–Reference Ward, Hill and Buckley39).

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart for the article selection process.

The outcomes of the quality assessment of the studies included in this systematic review are presented in online Supplementary Table 2. Three out of the nine observational studies were of positive quality(Reference Gu, Honig and Schupf29,Reference Meinilä, Perälä and Kautiainen32,Reference Nettleton, Diez-Roux and Jenny33) , while the remaining six studies were of neutral quality(Reference Chan, Woo and Suen27,Reference Crous-Bou, Fung and Prescott28,Reference Karimi, Nabizadeh and Yunesian30,Reference Lee, Jun and Yoon31,Reference Tucker34,Reference Zhou, Zhu and Cui35) . The reasons that observational studies scored neutral ratings were lack of blinding in outcome measurements (n 5), lack of withdrawal handling method (n 4), not applicable regarding procedure implementation (n 3), not applicable regarding procedure feasibility (n 3), unclear regarding free of bias in participants selection (n 2) and possible bias from funding source (n 2). Three out of the four interventional studies were of positive quality(Reference Canudas, Hernández-Alonso and Galié36,Reference Freitas-Simoes, Cofán and Blasco37,Reference Ward, Hill and Buckley39) , with one categorised as neutral quality(Reference García-Calzón, Martínez-González and Razquin38) (online Supplementary Table 2).

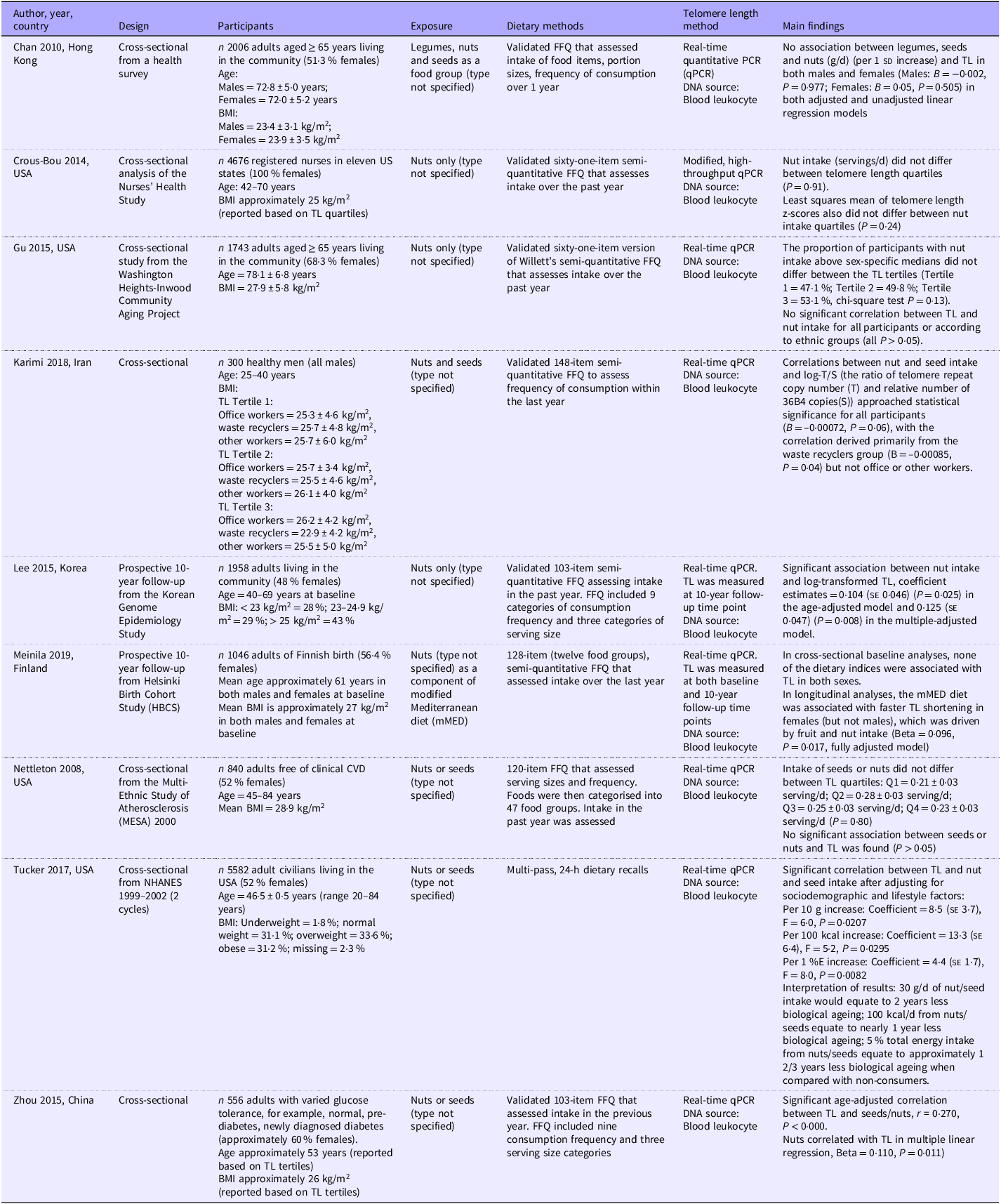

Evidence from observational studies

Of the nine observational studies included, seven studies had a cross-sectional design(Reference Chan, Woo and Suen27–Reference Karimi, Nabizadeh and Yunesian30,Reference Nettleton, Diez-Roux and Jenny33–Reference Zhou, Zhu and Cui35) , and two studies had a longitudinal design(Reference Lee, Jun and Yoon31,Reference Meinilä, Perälä and Kautiainen32) . Four studies were conducted in the USA(Reference Crous-Bou, Fung and Prescott28,Reference Gu, Honig and Schupf29,Reference Nettleton, Diez-Roux and Jenny33,Reference Tucker34) , one in Europe (Finland)(Reference Meinilä, Perälä and Kautiainen32) and four in Asia (two in China(Reference Chan, Woo and Suen27,Reference Zhou, Zhu and Cui35) , Iran(Reference Karimi, Nabizadeh and Yunesian30) and Korea(Reference Lee, Jun and Yoon31)). All studies were conducted in adults living in the community, with two studies specifically including adults aged 65 years or above(Reference Chan, Woo and Suen27,Reference Gu, Honig and Schupf29) . In terms of dietary exposure, one study grouped ‘legumes, nuts and seeds’ as a food group(Reference Chan, Woo and Suen27), four studies examined nuts only(Reference Crous-Bou, Fung and Prescott28,Reference Gu, Honig and Schupf29,Reference Lee, Jun and Yoon31,Reference Meinilä, Perälä and Kautiainen32) and the remaining four studies considered both nuts and seeds as one food group(Reference Karimi, Nabizadeh and Yunesian30,Reference Nettleton, Diez-Roux and Jenny33–Reference Zhou, Zhu and Cui35) . All but one study used validated semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaires that assessed dietary intake in the past year. The exception was a study that included data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which used a multiple-pass, 24-h diet recall administered by a trained National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey interviewer(Reference Tucker34). To determine telomere length, all studies used DNA extracted from blood leukocytes and followed the quantitative PCR technique. A summary of the observational studies is given in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of observational studies (n 9)

TL, telomere length; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Findings from observational studies on the associations between telomere length and nut and/or seed intake were mixed. Three (all of neutral quality) out of the nine studies reported positive associations between nut and/or seed intake and telomere length(Reference Lee, Jun and Yoon31,Reference Tucker34,Reference Zhou, Zhu and Cui35) . A study in the USA that used nationally representative data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (n 5582) reported that every 10 g/d increase in nuts and seeds intake was associated with 8·5 (se 3·7) base-pairs (bp) longer telomeres. Additionally, every 100 kcal/d higher energy intake and every 1 % higher energy intake from nuts and seeds were associated with 13·3 (se 6·4) and 4·4 (se 1·7) bp longer telomeres, respectively, after adjusting for sociodemographic and lifestyle factors(Reference Tucker34). The authors further reported that 30 g/d, 100 kcal/d and 5 % of daily energy intake from nuts and seeds would equate to 2, 1 and 1⅔ years younger biological ageing, respectively. Another study in China reported a significant correlation between telomere length and the intake of nuts or seeds (r = 0·270, P < 0·001), and in the multiple regression model, nuts alone were a protective factor for leucocyte telomere length (B = 0·110, P = 0·011)(Reference Zhou, Zhu and Cui35). Finally, a longitudinal observational study from Korea with 10-year follow-up also reported that nut (only) intake was prospectively associated with longer telomeres (coefficient-estimate for log-transformed telomere length = 0·125 (se 0·047), P = 0·0080) after 10 years(Reference Lee, Jun and Yoon31).

In contrast to the studies that reported positive associations above, two-thirds of the studies (n 6), all based on cross-sectional analyses, failed to find any significant relationships between nut/seed intake and telomere length(Reference Chan, Woo and Suen27–Reference Karimi, Nabizadeh and Yunesian30,Reference Meinilä, Perälä and Kautiainen32,Reference Nettleton, Diez-Roux and Jenny33) . Specifically, intake did not correlate with telomere length(Reference Chan, Woo and Suen27,Reference Karimi, Nabizadeh and Yunesian30,Reference Meinilä, Perälä and Kautiainen32) , and nut/seed intake did not differ between tertiles(Reference Gu, Honig and Schupf29) or quartiles(Reference Crous-Bou, Fung and Prescott28,Reference Nettleton, Diez-Roux and Jenny33) of telomere length. Interestingly, one of these studies, which included a longitudinal analysis, found that adherence to a Mediterranean diet was associated with faster telomere length shortening over 10 years in females but not males (B = 0·096, P = 0·017). This was found to be driven by the intake of vegetables and nuts; however, details on this were not provided(Reference Meinilä, Perälä and Kautiainen32).

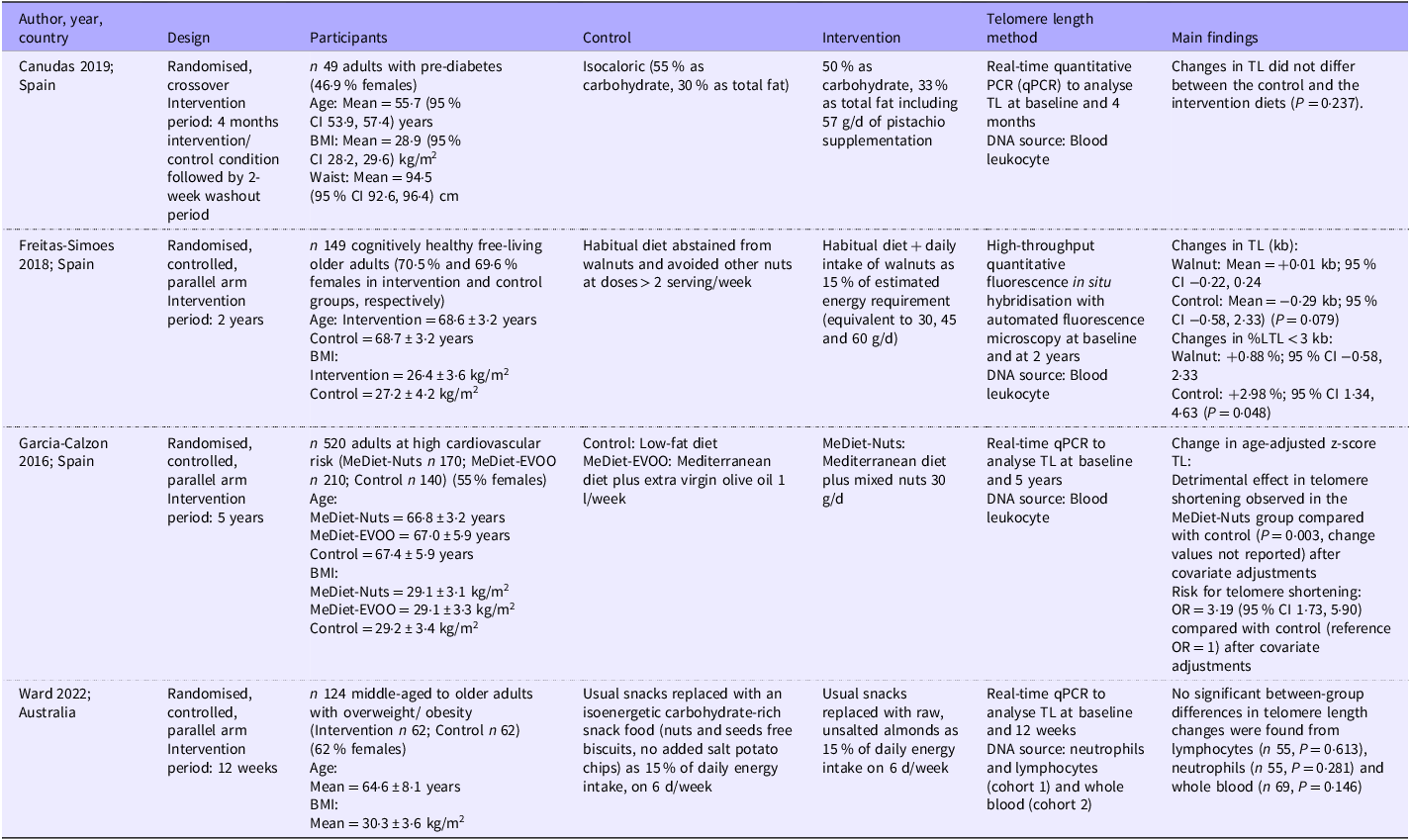

Evidence from interventional studies

Only four interventional studies were identified in this systematic review. Three studies were conducted in Spain(Reference Canudas, Hernández-Alonso and Galié36–Reference García-Calzón, Martínez-González and Razquin38) and one in Australia. These studies supplemented habitual diets with pistachios (57 g/d)(Reference Canudas, Hernández-Alonso and Galié36) and mixed nuts (30 g/d)(Reference García-Calzón, Martínez-González and Razquin38) or replaced 15 % of energy intake as walnuts or almonds(Reference Freitas-Simoes, Cofán and Blasco37,Reference Ward, Hill and Buckley39) . No study used seeds as an intervention. Three out of the four studies were randomised controlled(Reference Freitas-Simoes, Cofán and Blasco37–Reference Ward, Hill and Buckley39), parallel-arm trials(Reference Canudas, Hernández-Alonso and Galié36), and the other used a randomised crossover design. One study was conducted in cognitively healthy free-living older adults(Reference Freitas-Simoes, Cofán and Blasco37), while the other studies included middle-aged to older adults with pre-diabetes(Reference Canudas, Hernández-Alonso and Galié36), high cardiovascular risk(Reference García-Calzón, Martínez-González and Razquin38) or overweight or obesity(Reference Ward, Hill and Buckley39). The sample sizes ranged from 49 to 520, and the intervention period ranged from 12 weeks to 5 years. For telomere length outcomes, three studies used leukocytes as a DNA source(Reference Canudas, Hernández-Alonso and Galié36–Reference García-Calzón, Martínez-González and Razquin38), while the remaining study used neutrophils, lymphocytes and whole blood(Reference Ward, Hill and Buckley39). Three studies used the quantitative PCR method(Reference Canudas, Hernández-Alonso and Galié36,Reference García-Calzón, Martínez-González and Razquin38,Reference Ward, Hill and Buckley39) , while the other one used high-throughput quantitative fluorescence in situ hybridisation with an automated fluorescence microscopy technique(Reference Freitas-Simoes, Cofán and Blasco37). A summary of these interventional studies is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of interventional studies (n 4)

TL, telomere length; MeDiet, Mediterranean diet; EVOO, extra virgin olive oil.

In the largest (n 520) and the longest interventional study (5 years) included in this review (neutral quality), the authors found that a Mediterranean diet supplemented with 30 g/d of mixed nuts resulted in significant telomere shortening in participants after 5 years compared with the control group, which followed a low-fat diet (P = 0·003)(Reference García-Calzón, Martínez-González and Razquin38). This study further reported that the risk of telomere shortening in the nut-supplemented group was 3·19 (95 % CI = 1·73, 5·90) times higher than that in the control group. Findings from the remaining three interventional studies (all of positive quality) were consistent, where nut supplementation did not have any significant effects on telomere length when compared with the no-nut control diets(Reference Canudas, Hernández-Alonso and Galié36,Reference Freitas-Simoes, Cofán and Blasco37,Reference Ward, Hill and Buckley39) . However, the study that supplemented walnuts for 2 years reported a significantly smaller increase in the percentage of short telomeres (< 3 kb) in the intervention group compared with the control group after the intervention period (0·88 % (95 % CI 0·58, 2·33 %) v. 2·98 % (95 % CI 1·34, 4·63 %) and P = 0·048)(Reference Freitas-Simoes, Cofán and Blasco37). Meta-analysis could not be performed due to the high heterogeneity in the telomere length outcome measures reported across the studies.

Discussion

To date, the number of studies investigating the influence of nut and seed intake on telomere length is limited. Only nine observational studies and four interventional studies were identified and included in this systematic review. The findings are inconsistent across these studies, and the evidence is insufficient to confirm a beneficial role of nut and seed intake on telomere length.

An association between higher adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern and longer telomere length was previously reported in a systematic review and a meta-analysis that included data from eight cross-sectional studies(Reference Canudas, Becerra-Tomás and Hernández-Alonso40). Another systematic review, which examined the relationship between nutrition and telomere length, suggested a positive association between telomere length and the intake of certain antioxidant nutrients, fruits and vegetables, as well as adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern. This review summarised evidence from both observational cohort studies and interventional trials(Reference Galiè, Canudas and Muralidharan20). Although nuts and seeds are well known for their antioxidant properties and are an important food group in the Mediterranean diet, this is the first systematic review focusing specifically on the evidence linking nuts and seeds to telomere length.

Telomere length decreases with cellular ageing(Reference Müezzinler, Zaineddin and Brenner13) and thus is used to predict the risk of age-related diseases(Reference Fasching41). Nut consumption is shown to be protective against multiple age-associated conditions, including cancer(Reference Naghshi, Sadeghian and Nasiri42), CVD(Reference Coates, Hill and Tan43), diabetes(Reference Kim, Keogh and Clifton44,Reference Tindall, Johnston and Kris-Etherton45) and cognitive decline(Reference Nijssen, Mensink and Plat46). The predominant mechanisms through which nuts and seeds could protect telomeres include decreasing oxidative stress and inflammation(Reference Rajaram, Damasceno and Braga47). Telomere sequences are highly susceptible to oxidative damage, which leads to the inhibition of telomerase, the enzyme that protects telomere integrity. This process leads to telomere shortening and, eventually, cellular senescence(Reference Barnes, Fouquerel and Opresko48). Chronic inflammation further accelerates telomere shortening(Reference Liu, Nong and Ji49). Given the hypothesis that nuts/seeds are rich in nutrients that can reduce inflammation and oxidative stress, and subsequently lower the rate of telomere length shortening, the lack of any observed association or effect of these foods on telomere length was unexpected.

The lack of a positive association or effect observed in this review may be explained by several factors including heterogeneity in the methods assessing telomere length outcomes and variations in nut and seed intake. First, telomere attrition tends to occur in longer telomeres(Reference Farzaneh-Far, Lin and Epel50,Reference Ehrlenbach, Willeit and Kiechl51) , and failure to account for this factor may result in the lack of associations. Second, telomere repairs or homeostasis, facilitated by the telomerase enzyme, can occur on short telomeres(Reference Teixeira, Arneric and Sperisen52), and the prevalence of short telomeres may also be more important than the average telomere length in triggering cellular senescence(Reference Vaiserman and Krasnienkov53). Therefore, studies investigating telomere length outcomes may also focus on the proportion of short telomeres as a more sensitive outcome measure. This is supported by findings from the walnut interventional study, which showed a significantly smaller increase in the proportion of short telomeres (those < 3 kb) in the walnut group compared with the control group after 2 years(Reference Freitas-Simoes, Cofán and Blasco37). This was the only study in this review that focused on the short telomeres, and more studies are needed in the future to confirm nuts/seeds’ effects on short telomeres. Third, it has been proposed that old cells divide and, consequently, lose telomere length more gradually than young cells(Reference Ehrlenbach, Willeit and Kiechl51). This implies that assessing telomere length shortening in older adults may require a larger sample size or longer interventional/ observational periods.

Alongside concerns related to the outcome measures, there are issues with the accuracy of the dietary assessment methods for quantifying nut and seed intake in observational studies. The dietary assessment methods used required the ability to recall and accurately estimate nut and seed portion sizes. As highlighted by our previous review, comprehensive food, nutrient and recipe databases are needed to accurately quantify nut and seed intake(Reference George, Daly and Tey22). Moreover, human diets are complex. Although evidence suggests that certain healthy dietary patterns protect against telomere length shortening(Reference Galiè, Canudas and Muralidharan20), any effort to attribute an effect to a single food or food group, for example, nuts or seeds, may pose significant challenges, as it requires careful consideration of what other dietary aspects need to be accounted for. Although interventional studies have more control over this aspect, it is uncertain if the intervention dose, period and sample size were adequate to detect a statistically and clinically meaningful effect, given that telomere length was not the primary outcome in any of the interventional studies included in this review. In a longitudinal study, where faster telomere length shortening was reported to be driven by fruit and nut intake, the authors noted that this finding may be due to the study’s limitation of only using baseline dietary intake to predict telomere length shortening over 10 years(Reference Meinilä, Perälä and Kautiainen32). It was unknown whether the intakes of nuts and seeds changed during the 10-year follow-up. In the 5-year interventional study that reported detrimental effects of mixed nuts on telomere length in adults at high cardiovascular risk, the authors highlighted that the control group, who were advised to follow a low-fat diet, also increased their adherence to a Mediterranean diet(Reference García-Calzón, Martínez-González and Razquin38). Therefore, the underlying dietary patterns were comparable between the nut intervention and control groups. However, this does not explain why the nut intervention group experienced significantly greater telomere attrition while telomere length remained unchanged in the control group.

It is also important to highlight several strengths and limitations of the included studies and this review. First, although there were several observational studies (albeit the majority are of cross-sectional design), there were very few interventional studies, preventing the establishment of causation. Additionally, the interventional studies showed high heterogeneity in population, intervention type and duration and the reporting of telomere length outcomes, which hindered the ability to draw meaningful conclusions. Second, almost all studies performed carefully planned statistical analyses, adjusting for lifestyle and health factors known to influence telomere length, with age being adjusted for in all studies. However, it is acknowledged that not all relevant factors can be fully controlled. Future studies should consider adjusting for overall dietary patterns or quality when investigating the effect of a single food group. Third, it was found that most observational studies did not specify which nuts (e.g. tree v. ground nuts) were included in the analysis. Although nuts and seeds are generally nutrient-dense, some nuts or seeds may have an advantage over others. For example, walnuts were the only nut type to show protective effects on telomere shortening in an interventional study in this review(Reference Freitas-Simoes, Cofán and Blasco37). The exact underlying explanation is unknown, but walnuts are high in n-3 fatty acids compared with other nuts, hence, a plausible reason. It is unknown whether the grouping of walnuts with other nuts low in n-3 fatty acids in some studies in this review may have diluted the potential associations. If n-3 fatty acid intake is confirmed to be the underlying explanation, future studies should consider adjusting for intake or performing subgroup analysis to isolate the effects of n-3 fatty acids. Finally, no interventional study to date has investigated the effect of seeds on the telomere length. These should be investigated in future research.

Conclusion

In summary, the effects of nut and seed consumption on telomere length cannot be confirmed in this systematic review due to the limited number of studies and inconsistent findings. More interventional studies specifically investigating nut and seed intake and their impact on telomere length are needed. Nevertheless, this should not deter recommendations to include nuts and seeds as part of a healthy ageing diet, as they are nutrient-rich and offer protection against age-related diseases.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114525106028.

Acknowledgements

None.

No financial support provided.

Conceptualisation: S-Y. T. and J. H.; methodology: all authors; data curation: all authors; writing – original draft: M. B., M. P., M. E. D., C. D., O. G., M. W. and V. T.; writing – review and editing: S-Y. T., J. H., I. F., R. B. and S. L. T.; supervision: S-Y. T. and J. H.

J. H., S. L. T., R. B. and S-Y. T. have previously received research funding from various nut sector organisations.