Introduction

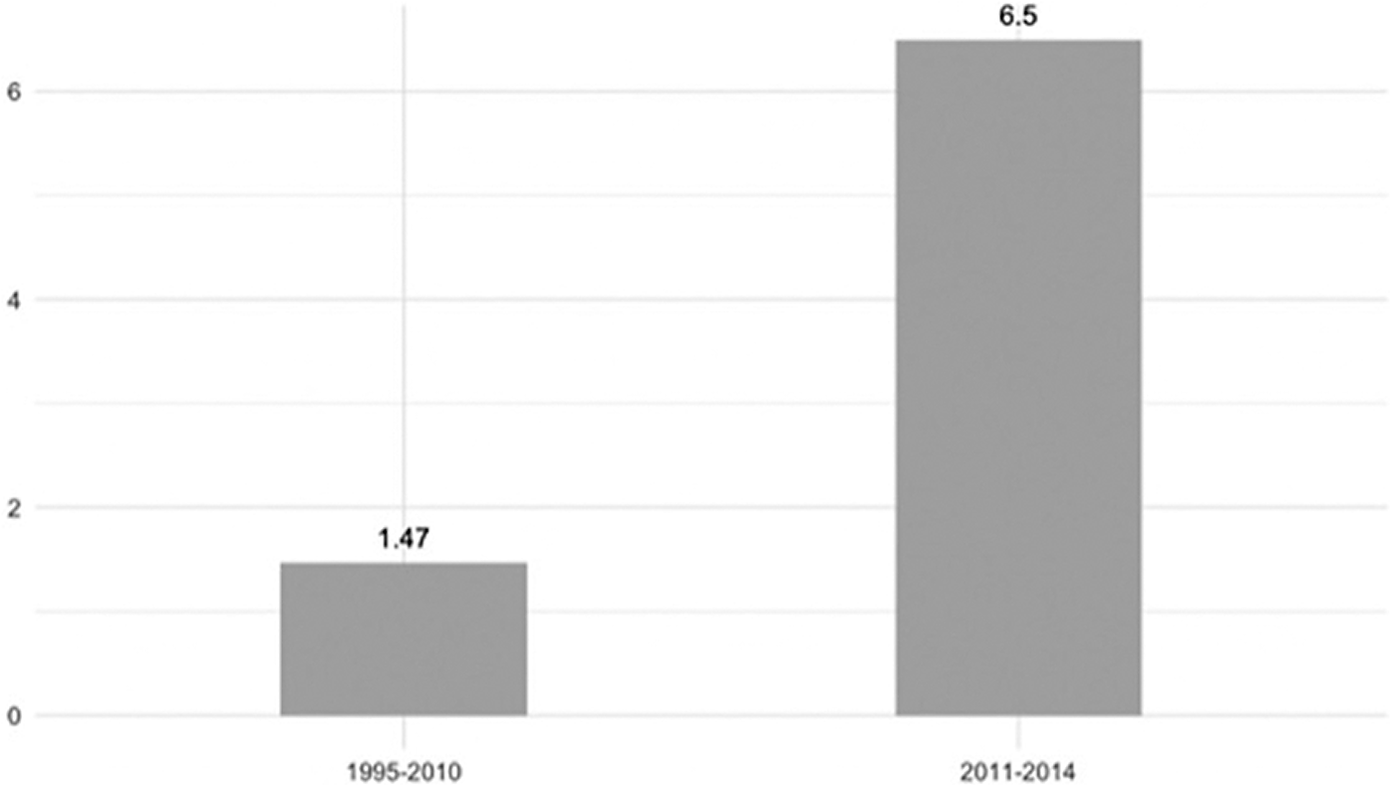

Since Xi Jinping assumed the presidency in 2013, China has adopted a more assertive approach to global affairs, particularly regarding its maritime claims over the South China Sea (SCS). Chinese officials began to clearly and frequently refer to the South China Sea as a core interest (O’Neill Reference O’Neill2018, 1–21). Moreover, there have recently been significant escalations in maritime disputes concerning the South China Sea, showing a tendency to shift from diplomatic or verbal tensions to actual military exchanges. China’s assertiveness became more explicit in 2009, with the inclusion of the nine-dash line map in a diplomatic note, and it further intensified under Xi Jinping, as seen in the sustained coast guard presence near Second Thomas Shoal in 2013, aimed at pressuring the Philippines (Chubb Reference Chubb2019). As shown in Figure 1, the average number of Militarized Interstate Disputes (MIDs) related to the South China Sea experienced a substantial three-fold increase during the period of 2011–2014 compared to the previous period of 1995–2010.

Figure 1. Average Number of Militarized Interstate Disputes (MIDs) Related to the South China Sea.

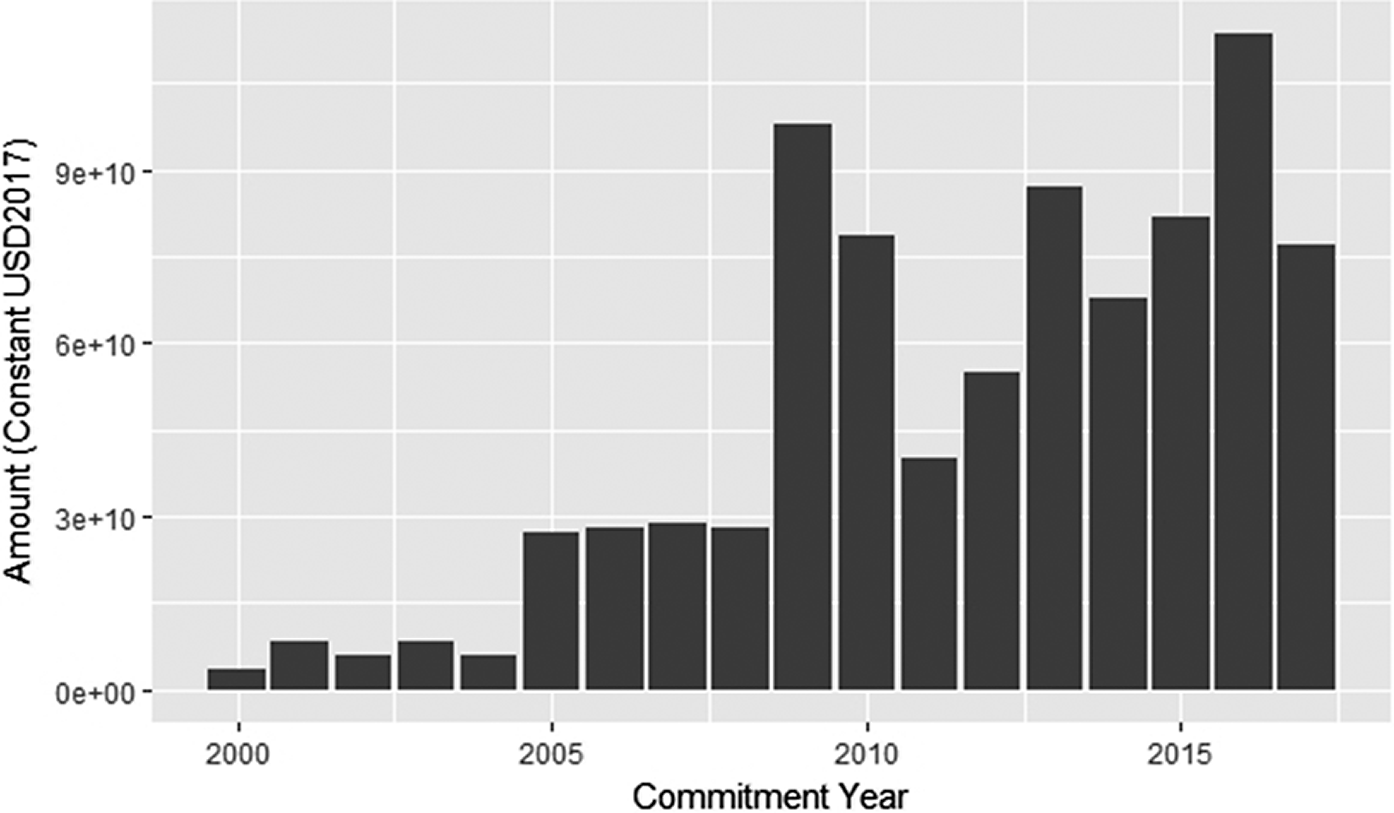

In tandem with this strategic shift, China has also increasingly focused on its foreign aid programs and their implications for advancing its political and economic interests (Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Su and Ouyang2022). A pivotal move was the announcement of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), demonstrating China’s substantial commitment to funding significant infrastructure projects in neighboring countries (Cheng Reference Cheng2020). Moreover, the amount of Chinese aid grew rapidly from the early 2000s to the late 2010s, towards every region of the world. Figure 2 illustrates the significant growth in China’s aid commitments from 2000 to 2017.Footnote 1

Figure 2. Chinese Aid Commitments by Year.

In other words, China has strengthened its economic levers of influence on other countries as a main asset. By examining these two distinct shifts in China’s behavior and potential changes in its global strategy, this article contends that China uses aid as a strategic foreign policy tool to induce favorable behaviors on the part of disputant states. For example, we found that one of the key claimants in the South China Sea, the Philippines, softened its stance during Rodrigo Duterte’s administration. The South China Sea issue represents a longstanding maritime dispute between China and the Philippines. In 2016, the arbitral tribunal under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) ruled in favor of the Philippines (Permanent Court of Arbitration 2016). However, instead of asserting its de jure sovereign rights reaffirmed by the tribunal, Duterte stated that the arbitration case of the South China Sea is merely a “piece of paper,” and one that would “take a back seat” (ABC 2016). Duterte added that he would not adopt a harder line and would wait for President Xi to bring up the South China Sea dispute (Lim Reference Lim2016). Following this surprising turnaround, China rewarded the Philippines with $24 billion USD worth of funding and investment pledges (Calonzo and Yap Reference Calonzo and Yap2016). This case involving the Philippines suggests that China may be utilizing its economic power as an aid donor to influence the behavior of disputant states.

China’s similar tactic pattern was also found in the case of Cambodia. Although Cambodia is not one of the claimant states to the South China Sea dispute, in 2012, China promised to provide the state with 450 million Yuan worth of economic assistance. In exchange, China demanded that Cambodia not internalize the South China Sea disputes within ASEAN (Yoshimatsu Reference Yoshimatsu2017). Consequently, at the 45th ASEAN Ministerial meeting in July 2012, despite its position as that year’s ASEAN chair, Cambodia cautiously refrained from including the South China Sea disputes on the agenda in the meeting’s joint statement (Yoshimatsu Reference Yoshimatsu2017).

This article argues that China is increasing its aid to effectively silence claimant states involved in military disputes. China carefully targets its aid to disputant states capable of exerting substantial political influence, effectively buying silence in the South China Sea disputes. We test our theories in the Southeast Asia region by utilizing the overlapping Maritime Assertiveness Time Series (MATS) dataset and AidData’s Global Chinese Official Finance Dataset for the aforementioned 2000–2015 period. This study provides empirical evidence that China strategically uses aid to control interstate military disputes in the South China Sea.

Our research contributes to the aid and conflict literature by examining the conditions that influence donors’ decisions to offer foreign aid to claimant recipients, specifically targeting claimants with smaller winning coalitions. The findings in this article support the potential of foreign aid to act as a bargaining tool capable of reducing interstate conflict. This South China Sea maritime dispute has created security tensions among China, the donor country, and various other Southeast Asian countries, recipients of Chinese aid. The presence of unique security dynamics in the region expands the theoretical and analytical space available to develop new models for testing the effects of donor aid on recipient policy shifts, even when both sides are involved in military disputes. In doing so, this research also contributes to the formulation of foreign policy implications for Asian countries insofar as it provides a better understanding of the conflict management strategy of China in the South China Sea disputes.

Foreign aid as a strategic tool: China’s strategic allocation of foreign aid to manage the South China Sea disputes

Foreign aid as foreign policy tool

Foreign aid is widely recognized as a highly cost-effective foreign policy instrument (Morgenthau Reference Morgenthau1962, 301–9). It is a fungible resource that can be easily converted into other assets. Donors can allocate aid based on their political and strategic considerations, rather than solely focusing on recipients’ economic needs or policies (Alesina and Dollar Reference Alesina and Dollar2000). Donor countries can utilize foreign aid as an effective strategic tool in two ways.

First, targeted foreign aid can serve as a valuable strategic tool for donor countries to cultivate positive perceptions among the public of aid recipients (Goldsmith et al. Reference Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Wood2014). By strategically allocating foreign aid, donor countries can create favorable images that contribute to achieving various strategic objectives in their foreign relations. Furthermore, aid recipients who have experienced the benefits of long-term assistance from a particular donor are more inclined to be receptive to the donor’s foreign policy goals (Blair et al. Reference Blair, Marty and Roessler2022).

In addition to promoting positive images, strategic aid allocation can help donors achieve their foreign policy objectives while building alliances with aid recipients. Donor countries also expect political support from aid recipients. During the Cold War, the US and the Soviet Union used foreign aid to stimulate international political support from aid recipients. The aid receivers allocated their political support to stimulate more aid from these donors (Lundborg Reference Lundborg1998). Donors also use aid allocation to pressure recipients to respond to their requests or encourage their cooperation in international affairs (Mosley Reference Mosley1986). These advantages make aid an expedient tool for influencing the behavior of recipient states (Tarnoff and Lawson Reference Tarnoff and Lawson2016; Bueno de Mesquita and Smith Reference Bueno de Mesquita and Smith2007, 255), leading many countries to employ aid as a foreign policy instrument.

China as aid donor

China has emerged as a prominent foreign aid donor, utilizing aid to exert influence over the governments of developing countries (Dreher and Fuchs Reference Dreher and Fuchs2011; Welle-Strand and Kjøllesdal Reference Welle-Strand and Kjøllesdal2010). Unlike Western donors, China’s foreign aid policies are usually “no strings attached,” free of democratic, good governance and human rights considerations (Welle-Strand and Kjøllesdal Reference Welle-Strand and Kjøllesdal2010). This approach has made China an attractive donor for many developing countries seeking to evade the conditionalities imposed by Western aid donors (Lengauer Reference Lengauer2011; Dreher and Fuchs Reference Dreher and Fuchs2011; Blair et al. Reference Blair, Marty and Roessler2022).

In this vein, Chinese foreign aid has more leverage and a comparative advantage to influence the governments of developing authoritarian states. This strategy proves successful by augmenting the resources accessible to autocratic leaders, enabling them to sustain the support of their comparatively small winning coalitions and finance patron–client networks (O’Neill Reference O’Neill2018, 79–87). Moreover, China mostly provides non-concessional aid as economic assistance, enabling the country to maintain long-term influence over the recipient state. Consequently, China can expect stronger and longer loyalties from such authoritarian recipient states. Against this backdrop, China is becoming increasingly economically integrated with Southeast Asian authoritarian countries such as Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam; and aid is a crucial tool for economic integration.

Additionally, in contrast to Western aid, Chinese aid exhibits more significant state influence, with aid allocation being highly politicized. Compared to Western donors, the Chinese state plays a fundamental role in aid allocation and exercises control over the actual outflow of aid (O’Neill Reference O’Neill2018, 70–86; Li et al. Reference Li, Long and Jiang2022). These unique characteristics of Chinese aid provide the state with a greater ability to influence aid allocation decisions directly. By observing aid allocation, one can peek into the intentions of the Chinese government (Blair et al. Reference Blair, Marty and Roessler2022; Landry Reference Landry2021; Dreher et al. Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2018).

Unfortunately, little research has been done on Chinese aid policy in neighboring Asian states. Moreover, Southeast Asia shares a distinct security dynamic with China, where many countries in the region face military tension with China. The unique security context allows room for scholars to develop new explanations of donor aid policy when the recipient is involved in military disputes with the donor.

Chinese aid as a strategic tool in South China Sea issues

The roots of the South China Sea disputes date back to the colonial period, with historical records indicating that China had militarized disputes with its neighboring countries (Buszynski and Roberts Reference Buszynski and Roberts2014). China has claimed sovereignty over the four major archipelagic groups in the South China Sea including the Spratlys, Paracels, Pratas, and the Macclesfield Bank and Scarborough Shoal, basing its indisputable sovereignty on historical surveying expeditions, fishery activities and naval patrols over the past years (Morton Reference Morton2016; Mustaza and Saidin Reference Mustaza and Saidin2020). Many of China’s Southeast Asian neighboring countries, including Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam, are claimant states of the South China Sea dispute. China has claimed the area within the nine-dash line, which extends hundreds of miles to the south and east of its island province of Hainan. This area overlaps with the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam.Footnote 2 Also, China, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia have claimed the whole or some parts of the Spratly islands and both China and Vietnam claim over Paracel islands (Emmers Reference Emmers2010). Thus, this maritime dispute became one of the recent and core militarized disputes between the Southeast Asian neighbors and China.

At the initial stage, the Southeast Asian claimants sought to manage the South China Sea disputes peacefully by signing the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC) in 2002 and engaging in ongoing efforts to adopt a binding Code of Conduct (COC). Also, in November 2002, during the 8th ASEAN Summit, both sides signed the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC), expressing their cooperative approach toward militarized disputes (Buszynski Reference Buszynski2003). However, negotiations with China over the South China Sea have faced stumbling blocks due to China’s assertive behavior. From the late 2000s through the 2010s, China’s stance on its maritime claims became significantly more assertive, leading to heightened tensions and growing concerns among ASEAN member states. The shift in China’s strategy in the South China Sea sends a clear signal to other Southeast Asian claimant countries that China is less likely to compromise and make concessions on the issue.

In response to China’s assertiveness, many ASEAN claimant states are taking active measures against China. Vietnam and the Philippines, for example, have shown distinct opposition to China’s behavior and declarations. Vietnam, which has the largest overlapping claims with China, has continuously protested Chinese fishery activities and has sought strategic support from the US to address the issue (Thayer Reference Thayer2016). Meanwhile, the Philippines has actively used diplomatic channels and pursued bilateral and multilateral military exercises with the US near the conflicted region (Lum and Dolven Reference Lum and Dolven2014).

Although few ASEAN claimant states are taking active diplomatic actions against China’s assertive behaviors in the South China Sea, China’s increased aid to ASEAN members hampers the member states’ ability to build a united front against China (O’Neill Reference O’Neill2018, 14). China has considerably expanded its aid programs, particularly in Southeast Asian nations. Given the increased military tension in the South China Sea, it becomes crucial to examine why and under what conditions China increases its aid to Southeast Asian countries.

Buying silence strategy through positive aid sanction in South China Sea disputes

Aid donors’ decision to impose aid sanctions

Economic sanctions serve as coercive foreign policy tools that states may employ to alter a target state’s behavior. Ultimately, if the cost of sanctions outweighs the benefits of not conceding, the target state will concede to the demands of the coercer. Sanctions should include a threat to penalize the target state for non-compliance, as well as a promise not to punish if the target state complies (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1971).

There are two types of sanctions: negative and positive sanctions. Firstly, negative sanctions create market imperfections by making transactions between private economic actors and the target state costly (Bapat and Kwon Reference Bapat and Kwon2015). In the context of aid, negative sanctioning refers to the termination or reduction of aid. Donor governments commonly use threats to terminate or reduce aid as a means of pressuring recipients (Morgan et al. Reference Morgan, Bapat and Kobayashi2014). On the other hand, positive sanctions are actual or promised rewards to the target state (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1971, 23). Such promises of rewards are considered a form of sanction because they imply a threat of not rewarding the target state if it fails to comply. Positive sanctions may include military alliances, development assistance, and foreign aid. States may impose positive sanctions to reward or even entice cooperation from the target states.

The dynamics of the cost and burden of sanctions vary when considering foreign aid. Since aid typically entails a unilateral transfer of funds from the donor state to the recipient state, the economic impact on the donor state from imposing aid sanctions is generally limited. However, negative sanctioning can have reputational costs for the donor country as it signifies non-compliance with aid commitments. This, in turn, increases the likelihood of the targeted recipient states seeking alternative aid partners and avoiding cooperation with the non-complying donor. On the other hand, positive sanctioning involves the donor providing additional aid to the recipient, bearing the economic costs alone but expecting cooperation from the target states.

Donor states will seek to minimize the negative side effects of sanctions, and generally, they will opt to withhold or terminate aid as a means of coercion. Chinese foreign economic assistance mostly consists of non-concessional loans (O’Neill Reference O’Neill2018, 86). China’s cancellation of 90 percent of its interest-free loans demonstrates its significant political leverage over aid and its use of negative sanctions as a foreign policy tool (Guérin Reference Guérin2008). However, some donor states, including China at times, impose positive aid sanctions instead of negative ones. For example, China awarded the Cambodian government $1 billion in aid after it agreed to deport Chinese asylum-seekers (O’Neill Reference O’Neill2018, 69–88).

Donor states do not typically send their money abroad without expectations attached and will calculate the cost and benefits of foreign aid (Dudley and Montmarquette Reference Dudley and Montmarquette1976). If foreign aid is unlikely to produce the intended result, donor states will not allocate more aid. Thus, unless the donor estimates a high probability of the target state changing its behavior after aid allocation, it would not be inclined to sanction positively.

Aid recipient’s small winning coalition and vulnerability to aid sanctions

In all types of regimes, a limited number of people, known as the winning coalition, hold indispensable support that enables a government to maintain political survival (Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2005, 10). Hence, leaders who aim to remain in power for an extended time require the backing from their winning coalition. This perspective is linked to the argument that politicians may use government resources to maintain and consolidate their positions of power (Landau Reference Landau1990; Anwar Reference Anwar2006). To secure support from these key players, leaders often offer policy concessions and share rents that favor their winning coalitions.

Rent sharing involves leaders designing a budget that maximizes the utility of the winning coalition by offering a combination of private and public goods (Licht Reference Licht2010). Political leaders can prolong their tenure in office by stockpiling reserve resources during periods of positive economic shocks. These reserves can then be deployed to mitigate the impact of subsequent economic downturns (Kono and Montinola Reference Kono and Montinola2009). Specifically, Kono and Montinola (Reference Kono and Montinola2009) indicate that leaders of small coalitions are particularly adept at accumulating such reserves compared to those with larger coalitions. Thus, in regimes characterized by small winning coalitions, the extraction of rents through either direct appropriation or the manipulation of redistributive policies that benefit a select group is more likely to occur.

Moreover, the influence of a winning coalition’s size on member loyalty has significant ramifications for a leader’s political tenure. As observed by Kono and Montinola (Reference Kono and Montinola2009), a smaller coalition size facilitates maintaining power with fewer resources, as loyalty within the group is enhanced. The value of being part of a winning coalition diminishes as its size increases, leading to a proportional decrease in group loyalty. Therefore, leaders of smaller coalitions often benefit from a more devoted following. This dynamic is particularly pronounced in regimes with compact winning coalitions, which typically exhibit higher levels of loyalty within their inner circles (Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2005).

Foreign aid serves as an additional resource for leaders engaged in tenure-seeking activities (Licht Reference Licht2010). Recipient state leaders can leverage foreign aid as a fungible resource to buy the support of elites and other important political groups within the country to cement their position in power domestically (Brooks Reference Brooks2002; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2013). Consequently, for leaders, especially those who have small coalitions, foreign aid becomes a vital tool to reinforce their political stability. Such leaders are more effective in leveraging foreign aid as a strategic resource to bolster their governance. Thus, from the perspective of recipient leaders, promises and actual allocations of foreign aid are potent incentives that can prompt a change in behavior. Therefore, when donor states provide substantial amounts of foreign aid to recipient states, they can significantly influence their domestic and foreign affairs (Apodaca Reference Apodaca2017).

While the donor’s aid sanctions will undoubtedly affect recipient leaders, the degree of the impact will vary depending on the domestic political situation of the recipient leader. Recipients who depend on aid as an additional resource to buy off their winning coalition are likely to be more vulnerable to the donor’s aid policies. Thus, donor states’ decision to impose aid sanctions will depend upon how susceptible the recipient is to the donor’s aid policy and how much leverage the donor is able to exert over the recipient.

Chinese positive aid sanction: Bargaining power over aid recipients

As previously discussed, regimes with small winning coalitions often exhibit a greater willingness to concede to the demands of donor nations in exchange for aid. When the recipient state has a small and exclusive winning coalition, donor countries can utilize foreign aid as a strategic tool with even greater efficiency (Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2005; Bueno de Mesquita and Smith Reference Bueno de Mesquita and Smith2009). In such contexts, aid sanctions significantly impact the targeted recipients, whose political leadership relies on closely knit coalitions (Brooks Reference Brooks2002, 10–11).

This article posits that China employs positive sanctions to quell dissent among the claimants in the South China Sea disputes. By providing increased aid to recipient states with smaller winning coalitions, China aims to de-escalate tensions by encouraging these states to withdraw from maritime militarized disputes. The strategy of positively sanctioning claimant states, which are more vulnerable, may influence their military and foreign policies. Notably, China’s distinctive patronage politics with certain claimant states in the South China Sea and clientelism politics in ASEAN countries afford the donor significant leverage to coerce its recipients to alter their stance on ongoing conflicts with Beijing.

Clientelism in Southeast Asia can explain why China’s positive aid can be a tool to pressure Southeast Asian claimants. Dreher et al. (Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Hodler, Parks, Raschky and Tierney2019) demonstrate that Chinese aid can be especially susceptible to exploitation by politicians involved in clientelism politics. Political survival is generally governed by clientelism where politicians provide reward to their core constituents in exchange for votes (Dreher et al. Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Hodler, Parks, Raschky and Tierney2019, 46). In democracies characterized by clientelism, such as the Philippines, vote-buying is commonplace. Previous studies indicate that approximately 30 percent of voters were offered monetary inducements for their ballots in the 2010 and 2016 elections (Cruz Reference Cruz2019; Mendoza et al. Reference Mendoza, Beja, Venida and Yap2016). In Vietnam, a party-based authoritarian regime, top Vietnamese leaders also routinely allocate pork or provide benefits in kick-backs from construction contracts to achieve their electoral support before Party Congresses (Malesky Reference Malesky2009). Researchers also find that public investment significantly increased two years before a Party Congress and declined after (Malesky et al. Reference Malesky, Abrami and Zheng2011). With a small and closely connected winning coalition, it becomes easier for donor states to direct foreign aid towards influencing the recipient state’s political elite. These dynamics consequently enhance the bargaining leverage of Chinese aid in recipient countries especially those who are more dependent on aid and have smaller winning coalitions (Biglaiser and Lu Reference Biglaiser and Lu2021; Isaksson Reference Isaksson2020, 834–35).

For instance, Nguyen Phu Trong, the former General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam, tried to consolidate power by keeping close economic ties with China (Cook Reference Cook, Rosman and Chinyong2018). Sustaining high economic growth is crucial for political stability and Vietnam needed more investment to achieve the goal under Trong’s leadership (Thanh and Dapice Reference Thanh and Dapice2009). To sustain rapid economic growth, Vietnam relied on essential funds, with Chinese aid playing a vital role in the maintenance of Trong’s political power. Despite tensions over the South China Sea, Vietnam needed to maintain a considerable amount of aid from China under Trong’s leadership (Ma and Kang Reference Ma and Kang2023, 368). The Vietnam case illustrates how China’s positive aid sanction can reduce the South China Sea conflict.

Similarly, the Philippine case exemplifies the interconnection of aid sanction and South China Sea conflict, showing how political elites leverage Chinese aid to boost domestic power. Under President Duterte, longstanding issues like dynastic politics, party-switching, and patronage worsened (Teehankee Reference Teehankee, Tomsa and Ufen2013). Duterte’s populist approach further undermined the party system, enabling major electoral wins for his allies in 2019 midterm elections (Teehankee Reference Teehankee2024). Additionally, Duterte’s pursuit of authoritarian policies led to human rights abuses, which alienated Western donors and prompted him to pivot toward closer ties with China.

In line with Duterte’s foreign policy pivot, the Philippines recalibrated its approach to the South China Sea dispute to align with its deepening economic ties with China. Although the Philippines had escalated the South China Sea conflict by initiating arbitration under UNCLOS in 2013, resulting in a favorable ruling from the Hague tribunal in 2016, the Duterte administration downplayed the ruling and prioritized economic engagement with China. Following Duterte’s meeting with President Xi Jinping, where China pledged $24 billion in aid for Philippine infrastructure (Kim Reference Kim2021), China swiftly committed billions in funding, including a $224 million dam project and a $280,000 rail project (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2018). Duterte’s administration pushed for rapid progress on high-profile infrastructure projects such as the Kaliwa Dam and the Chico River Pump Irrigation Project, both of which advanced significantly during his term (Camba Reference Camba2021). These initiatives bolstered Duterte’s domestic political standing, illustrating how Chinese aid was strategically used to secure elite support and expand political influence, while sidelining territorial disputes (Camba Reference Camba2021).

By addressing theoretical discussions and providing case examples, we argue that China is more likely to provide aid to South China Sea claimants with smaller winning coalitions. To test this, we distinguish between two types of disputes between China and ASEAN claimant states to analyze aid distribution patterns. First, we examine militarized disputes involving reactive assertiveness from both sides. For example, in 2011, China entered Vietnamese waters, blocked oil exploration, and faced Vietnamese military exercises in response (Palmer et al. Reference Palmer, McManus, D’Orazio, Kenwick, Karstens and Bloch2022). After initiating tensions, China may then actively offer aid to ASEAN claimants as part of its own strategy to silence them or manage their responses. Second, we analyze cases where ASEAN states initiate assertive actions. Though China has grown more militarily assertive, ASEAN claimants have also taken aggressive steps, such as when the Philippine navy seized two Chinese fishing vessels near Luzon (Palmer et al. Reference Palmer, D’Orazio, Kenwick and Lane2015). In such cases, China often responds with aid to de-escalate tensions. This approach is seen as more cost-effective than military retaliation, which risks the US involvement and could drive ASEAN states closer to Washington. By offering aid, China enhances its long-term political leverage over recipient states while avoiding direct conflict.

There are specific differences between two specific cases in terms of 1) the initiator of assertiveness and 2) China’s perception of assertive actions. The first case represents a broader situation in which China initiates the dispute, but Southeast Asian countries may still respond assertively, leading to a situation of mutual escalation. Here, both sides contribute to the tensions, and responsibility is not one-sided—both China and ASEAN states may contribute to escalation. In contrast, the latter captures a more specific case in which Southeast Asian states initiate the dispute but still China aimed at silencing claimants in Southeast Asia through aid as a diplomatic tool. This approach carries greater political and strategic cost, making China’s aid more significant in this context.

Testing these two scenarios provides valuable insight into China’s strategic intent. Assertive behavior by ASEAN states may reflect their willingness to challenge the status quo, potentially influencing China’s aid allocation. While both cases relate to China’s use of aid to manage maritime disputes with countries that have small winning coalitions, distinguishing who initiates the conflict offers important insights into China’s strategic logic.

Based on the above conjectures, the following hypotheses can be derived:

Hypothesis:

-

a. When both China and an ASEAN member state engage in assertive actions, ASEAN claimant states with small winning coalitions are more likely to receive increased Chinese foreign aid than non-claimant states or claimant states with large winning coalitions.

-

b. When the assertive actions are initiated by ASEAN states, those with small winning coalitions are more likely to receive increased aid from China than non-claimant states or claimant states with large winning coalitions.

Data and empirical strategy

Dataset and operationalization of variables

To test the hypotheses concerning the relationship between the aid amounts and assertive actions of actors committed in the maritime disputes in the South China Sea, conditioned on the winning coalition size, a number of datasets are employed that provide information. The unit of analysis is the country-year, representing the aid the donor state (China) provides to its recipient(s), the ASEAN, in a given year. To conduct the empirical analysis, we re-code the information of the Chinese aid dataset (Dreher et al. Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2022). This dataset provides information on the dependent variable of this article, the Chinese aid amount in a given year. For the independent variables of this article, the Maritime Assertiveness Time Series (MATS) dataset (Chubb Reference Chubb2022) is utilized. Using these datasets, the period from 2000 to 2015 is analyzed, with 9 different ASEAN countries identified in this dataset.Footnote 3

Dependent variable

The dependent variable in this study is the amount of Chinese aid allocated to ASEAN states. The Aid Data’s Global Chinese Official Finance Dataset (Dreher et al. Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2022) is used to retrieve the yearly Chinese aid amounts to ASEAN countries. The data set captures over 13,427 development projects worth $843 billion that were financed by more than 300 Chinese government institutions and state-owned entities across 165 countries from 2000–2017 (Oh Reference Oh2020). This article relies on this dataset to estimate the amounts of Chinese aid, rather than other aid datasets such as OECD aid data or World Bank aid data. For more descriptive summary statistical information on aid dataset, refer to the Appendix.

For the purpose of this research, only aid projects that have reached the official commitment stage are considered. The aid amounts allocated to ASEAN states are aggregated by year, and in instances where no aid was given or projects were suspended or canceled, the amount is coded as 0 for the respective year. To ensure comparability over time and space, the reported aid amount in the dataset is constant 2017 US dollars. It is worth noting that Chinese aid data is continuous data, and aid amounts have increased rapidly in recent years (see Figure 2). A logarithmic transformation with an additive constant of 1 is applied to the dependent variable to reduce skewness in the aid data and to avoid computational issues associated with taking the natural logarithm of zero when no aid is allocated.

Independent variable

This article uses the Maritime Assertiveness Time Series (MATS) dataset to examine the independent variable of China and claimant states’ assertive actions in the South China Sea. The MATS dataset is collected from open press sources and historical works by China and claimant states’ official government documents. This new dataset identifies four types of assertive actions: declarative (verbal assertions via non-coercive statements); demonstrative (e.g., patrols, surveys, resource development, construction of infrastructure); coercive (threat or imposition of punishment); and use of force (Chubb Reference Chubb2022).Footnote 4

To test the hypotheses, this article operationalizes the independent variable in two ways. First, we use the total number of assertive actions from both parties (China and ASEAN) against each other in a given year. This variable captures the overall frequency of assertive actions between Southeast Asian claimant states and China in the South China Sea. Additionally, we construct the “ASEAN Claimants’ assertive action” variable as another independent variable. This variable captures the total number of assertive actions against China initiated by the ASEAN claimant state.

Moderator variable

In this research, the moderator variable used to test the two key hypotheses is the “winning coalition” size. We adopt the newly developed W indicator by Bueno de Mesquita and Smith (Reference Bueno de Mesquita and Smith2022) to measure the winning coalition’s size. This measurement offers a more comprehensive assessment compared to other regime type measurements, such as the Polity score, by incorporating various factors that determine the country’s winning coalition size.Footnote 5 The W indicator, is calculated using institutional variables developed from the V-Dem project, including 1) Autonomy of election monitoring body; 2) Opposition parties’ autonomy; 3) Barriers to political party participation; 4) Closed Succession, an indicator of succession by heredity or within a military or single party setting (Bueno de Mesquita and Smith Reference Bueno de Mesquita and Smith2022, 5). W indicator is a continuous index that ranges from 0 to 1, with a score close to 0 indicating the smallest winning coalition size and a score close to 1 representing the largest winning coalition size (Bueno de Mesquita and Smith Reference Bueno de Mesquita and Smith2022). The W indicator does not provide any score of Brunei, a monarchy. Hence, we recode Brunei’s score by calculating the average score of other Muslim monarchy states in the dataset.Footnote 6

Confounding covariates

In this study, we incorporate various confounding variables that may affect China’s aid distribution to each ASEAN recipient. First, we include GDP growth (percent) as a control variable. The growth rate of a country’s GDP may serve as a determinant that impacts the allocation of donor state aid (Carter Reference Carter2014). China may provide more aid to recipients experiencing higher growth, viewing them as promising economic partners, or alternatively, may target countries with lower growth that signals greater need for assistance. To measure the GDP growth rate, we utilize the variable from the World Bank Development Indicators (WDI) Data (World Bank 2018).

Second, GDP per capita (2015 US Dollars) is another control variable for this article. A country’s economic status can have an impact on the amount of foreign aid it receives. Recipients with a comparatively higher GDP per capita are less susceptible to Chinese aid offers and can refuse requests to alter their foreign policy regarding militarized disputes in exchange for aid packages. We obtain this variable from the World Bank Development Indicators (WDI) Data (World Bank 2018).

As a third control variable, this study considers the trade interdependence between China and ASEAN recipient states. It is reasonable to assume that states which are more dependent on Chinese trade may be less likely to become strong opposers to China. Additionally, China may allocate more aid toward its critical trading partners. Therefore, trade relations with China may be a confounding variable. To calculate ASEAN’s trade dependency on China, we use the trading data (1974–2014) from the COW dataset (Barbieri et al. Reference Barbieri, Omar and Pollins2009). For the missing years of 2015–2017, we collect the export and import data directly from the IMF DOTS database (Direction of Trade Statistics) and calculate the trade interdependence using the same method as the COW data set.

Lastly, this article also considers US military ties as a key confounding variable in the empirical models. It is assumed that states allied with the US are more likely to support the US and oppose China or expect to receive support from the US in resisting China’s assertive claims. To conduct empirical analysis, we obtain information on military alliances from the Alliance Treaty Obligations and Provisions (ATOP) dataset (Leeds et al. Reference Leeds, Ritter, Mitchell and Long2002). We code “US military ties” as 1 if a country has signed a defense pact with the US, and 0 otherwise. Table 1 provides a summary of the variables and their corresponding data sources utilized in this article.

Table 1. List of variables and data sources

Method

We conduct Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) tests using the independent and the control variables described above. The OLS regression analysis includes an interaction term to capture the effects of the size of winning coalitions on China’s decision to allocate aid to ASEAN recipients. This variable is constructed as an interaction between assertive actions and the size of winning coalitions. The coefficient of the interaction term (number of Assertive Actions × W indicator) and its p-value show whether the variable has a significant impact on China’s aid allocation decisions.

In order to account for the heterogeneity in Chinese aid across different years (Appendix: Figure 3), we include a year fixed effect in our main model. This allows us to control for unobserved time-variant covariates, such as fluctuations in Chinese financial policies and the subsequent aid shocks. The use of time-fixed effects assumes that (1) past aid treatment does not directly influence current outcome, and (2) past outcomes do not affect current treatment (Imai and Kim Reference Imai and Kim2019). In other words, we assume that there is no spillover effect of Chinese aid from one year to the next. However, the two-way fixed effect models are not reported as our main model, due to the multicollinearity issue with country fixed effects and our other confounding covariates. The confounder variables of our research already capture the country level variation, so we do not apply the country fixed effect in our models. The results of the two-way fixed effect models for country and year fixed effects can be found in the Appendix.

Figure 3. Predicted values of Chinese aid.

Results

Tables 2 and 3 present the empirical results for testing Hypothesis a and Hypothesis b, respectively. Table 2 presents the estimation results for Hypothesis a: when both China and an ASEAN member state engage in assertive actions, ASEAN claimant states with small winning coalitions are more likely to receive increased Chinese foreign aid compared to non-claimant states or claimant states with large winning coalitions. Table 3 reports the estimation results for Hypothesis b, which tests whether assertive actions initiated solely by ASEAN states with small winning coalitions lead to increased aid from China.

Table 2. Winning coalitions and assertive actions on both sides: Year fixed-effects estimates

Note: *p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01

Table 3. Winning coalitions and ASEAN assertive actions: Year fixed-effects estimates of Chinese aid

Note: *p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01

The findings strongly support both hypotheses, indicating that assertive actions by small winning coalition ASEAN states attract more aid from China, regardless of who initiated the actions. Specifically, our results suggest that ASEAN states with smaller winning coalitions receive more aid allocation from China when they engage in assertive actions, and this effect is even stronger when the actions are initiated by the ASEAN state.

Table 2 reports the results of the model with and without year fixed effects, which tests Hypothesis a. The main explanatory variable, which is the interaction between assertive actions and ‘W indicator’ capturing the size of the winning coalitions, is statistically significant in the expected direction in the time-fixed model of Table 2. The OLS model results suggest that when there are more assertive actions, ASEAN states that have larger winning coalitions receive a 3.239 percent decrease of Chinese aid compared to ASEAN states with smaller winning coalitions. This result is significant at the 1 percent level. The W indicator is a continuous variable, and the winning size is larger when the index is closer to 1.

Figure 3 plots the overall mean predicted outcomes of implemented Chinese aid amounts for W score indicators based on Model (1) of Table 2. In order to plot a continuous variable interaction model, the W indicator is categorized to either 0 or 1. The figure shows that the mean predicted amount of aid for ASEAN states increases when the W indicator is 0, while when the W indicator is 1 the amount of aid decreases. In other words, ASEAN states, with smaller winning coalitions, are likely to receive more aid when involved in assertive actions compared to their counterparts with larger winning coalitions.

Table 3 depicts the year fixed models and the model without time fixed effect that tests Hypothesis b. Similarly, the main explanatory variable in Table 3, which is the interaction term between assertive action and W indicator is statistically significant in the expected direction. The results indicate that when ASEAN states initiated the conflict, states with larger winning coalitions were likely to receive less aid from China. When there are more assertive actions, there is a 5.513 percent decrease in Chinese aid allocation, while remaining regressors are held at their mean values. ASEAN states with larger winning coalitions, or large W scores are likely to receive less aid than their counterparts. The explanatory variable of Table 3 is significant at the 1 percent level.

In sum, our study provides strong empirical evidence supporting our theoretical framework. Our results show that China tends to allocate more aid to ASEAN states that are more susceptible to foreign aid, especially when those states are involved in assertive actions. Furthermore, ASEAN states with smaller winning coalitions that initiate assertive actions are more likely to receive larger aid packages from China. These findings suggest that China’s positive aid sanctions are conditional on the recipient’s vulnerability to aid based on its winning coalition size.

We posit that China’s strategy of providing to developing authoritarian states is aimed at shaping the incentives of the leader through bilateral foreign economic policies, such as foreign aid, loans, and investment. This strategy has proven successful in expanding the resources available to autocrats, enabling them to maintain the support of their relatively small winning coalitions. Consequently, those with small winning coalitions are more likely to be susceptible to aid and will likely comply with China’s demands. In times of intense conflict, China may even choose to bribe its counterpart to back down from the conflict by distributing more aid. While we do not test the process of this mechanism in this article, we closely examine the case of Vietnam, one of the claimant states, and find that it aligns positively with our proposed theory.

Supporting our hypothesis, Vietnam provides a compelling case study. Categorized as a party-based authoritarian regime under the W score coding, Vietnam has a W score between 0.132 and 0.24, indicating a small winning coalition (Bueno de Mesquita and Smith Reference Bueno de Mesquita and Smith2022). The legitimacy of Vietnam’s one-party socialist state is rooted in Ho Chi Minh’s charismatic leadership and the country’s history of defending against foreign rule (Thayer Reference Thayer2009). China and Vietnam, both single-party communist regimes, once shared a unique relationship. Prior to the breakdown of Sino-Vietnamese relations in 1979,Footnote 7 the countries enjoyed close ties, bonded by shared ideological beliefs and personal connections between leaders Ho Chi Minh and Mao Zedong (Do Reference Do2021).

After normalizing relations in 1991, the two sides sought to strengthen their unique party-to-party ties. Since then, senior leaders from Vietnam and China have met annually to review their bilateral relations (Guan Reference Guan1998). This relationship has established a direct communication network between the communist parties (Do Reference Do2021).Footnote 8 Regular meetings between high-level party leaders have provided platforms for strategic reassurance. These established communication channels are vital in addressing South China Sea disputes, facilitating both government-level and high-level talks to address the issue (Guan Reference Guan1998; Li Reference Li2014). For China, maintaining direct communication channels with Vietnam and further developing diplomatic talk, signals a commitment to resolving tension. In the event of a clash in the South China Sea, this commitment may motivate China to offer aid to Vietnam, seeing it as an opportunity to rebuild the relationship and address the issue quickly.

As previously noted, Vietnam has been one of the countries most affected by China’s assertive actions in the South China Sea due to extensive overlapping territorial claims. These tensions have triggered frequent public protests and strong nationalist sentiment, especially during the 2014 oil rig crisis, which saw heightened public pressure for a tougher stance against China. Despite rising tensions, China increased aid to Vietnam in 2014, continuing to fund education and infrastructure projects. This included a $1.402 billion syndicated loan for a power plant and a $200 million loan from the China Development Bank in 2015 to support broader economic development (Dreher et al. Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2022).

Our research indicates that China has successfully attempted to buy Vietnam’s silence on the South China Sea issue, as evidenced by Figures 4 and 5, which demonstrate the effectiveness of the “buying silence” approach. The graphs (Figure 4 and 5) illustrate that the implemented aid amount increases when the number of assertive actions is higher in previous years.

Figure 4. Observed China’s aid to Vietnam and both sides’ assertive actions.

Figure 5. Observed China’s aid and Vietnam’s assertive actions.

Figure 4 displays a pattern that indicates a correlation between China’s aid project implementation and the total numbers of assertive actions taken by both China and Vietnam. The data reveals that there are significant spikes in the aid implementation preceded by an escalation of assertive actions. It can be inferred that the sudden increase in aid may have been utilized as a diplomatic tool or as part of China’s foreign policy strategy to alleviate the heightened tension between the two states.

Figure 5 illustrates the correlation between Vietnam’s assertive actions and the implementation of aid projects by China in general. It demonstrates that there is a positive relationship between the surge in assertive actions by Vietnam in the prior years and the increase in aid allocated by China, especially during the 2000s and 2010s. After a higher number of assertive actions from Vietnam, an increase in aid from China is observed. This trend suggests China strategically uses foreign aid to induce compliance among states with small winning coalitions engaged in the South China Sea disputes.

Robustness Tests

The preceding analysis shows a significant relationship between China’s implemented aid and the interaction term (Assertive Actions × W indicator). To address concerns not covered in the main empirical section, we also examine committed aid as the dependent variable. While the main model focuses on implemented aid, pledged aid differs from implementation, committed aid can be adjusted more readily in response to assertive behavior, whereas altering aid already in the pipeline is more difficult. Thus, committed aid may better reflect China’s strategic responses. Nonetheless, robustness checks using committed aid yield results consistent with our main findings, reinforcing the reliability of our conclusions across alternative aid measures.

To further account for potential confounding variables, additional robustness tests were conducted. First, we included controls for Chinese high-level visits as a proxy for bilateral relations, as well as Chinese leadership periods to account for shifts in foreign policy priorities. Second, to address potential endogeneity between assertive actions and aid allocation, we lagged assertive actions and included prior aid allocation as controls to mitigate long-term effects of conflict behavior. Across these additional models, the interaction between assertive behavior and winning coalition size remains statistically significant. Due to space constraints, we address the specific findings from robustness tests in the Appendix.

Conclusions

In this study, we introduced a theoretical framework and tested a model that emphasizes the importance of conditionality in foreign aid allocation. Specifically, we highlight the role of the recipient state’s winning coalition size in shaping the donor’s decision to employ carrots rather than sticks during militarized disputes. The decision to reward target states with more aid allocations, “positive sanctions,” in exchange for policy concessions depends largely on the recipient state’s vulnerability to aid-based influence.

The hostility between China and ASEAN claimant states was reduced in the early 2000s due to China’s adoption of a reassurance policy toward regional partners. However, the intensification of China’s territorial assertions in the South China Sea reignited regional tensions. China’s main goal is to avoid internationalizing the dispute, which would attract unwanted international attention to the disputed region. This sort of behavior has been seen constantly in China’s South China Sea policy of averting intervention by external powers and refusing multilateral approach towards dispute resolution (Buszynski 2012; Yahuda Reference Yahuda2013; Morton Reference Morton2016; Mustaza and Saidin Reference Mustaza and Saidin2020). Previous scholars (Cook Reference Cook, Rosman and Chinyong2018; O’Neill Reference O’Neill2018; Beeson and Watson Reference Beeson and Watson2019; Stubbs Reference Stubbs2019) have noted that China significantly prevents ASEAN from forming a united front against its interests. China’s objective is to encourage the claimant states to retreat from the dispute and ideally manage the situation through alternative diplomatic means, aiming to de-escalate tensions. Consequently, in the face of mutual assertiveness, China is inclined to extend positive sanctions to ASEAN claimants more receptive to foreign aid, thus enhancing the likelihood of concessions. Even when the ASEAN claimant state initiates the assertive actions, China will offer more aid to vulnerable recipient states with small winning coalitions as a means to alter their hostile behavior.

The empirical results indicate a systematic preference in aid distribution to claimants with smaller winning coalitions which is consistent with the proposed theory. Instances involving the Philippines and Vietnam suggest that China is using aid to buy silence from the claimant states of the South China Sea. These cases show that states may be willing to back away from pressing their claims of sovereignty over the South China Sea if they can be bribed into silence. The results of this research advance our understanding of China’s aid policies towards ASEAN states involved in militarized disputes.

Finally, our study opens a number of avenues for future research. This article focuses on analyzing China’s aid pattern towards Southeast Asian countries that are involved in disputes. Hence, expanding the scope of this article could direct a series of future research programs as well. For example, future research questions might include: How have China’s aid amounts shifted towards non-ASEAN claimant states? How did other main donor countries involved in a series of interstate disputes carry out aid policies toward their recipient states? These and other future research questions will advance our understanding of the relationship between donors’ decisions to provide aid to claimant recipients. These questions are, however, also subject to an additional caveat: This article’s results show only the correlation between Chinese aid and the assertive actions of aid recipients. While this study provides evidence that the Chinese government has provided more aid to claimant recipients with a small winning coalition size, combining this work with future research will act as a guidepost for expanding our understanding of China’s aid policies, as well as, more generally, donor countries’ decisions to provide aid to recipients they are in conflict with. This study has found that donor states have offered more aid to claimant countries with small winning coalitions. This is an important step forward. Based on these findings, we believe that our recommended future studies will contribute to bridging two very different literatures in international relations: aid and conflict.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/jea.2025.10018.

Jinwon Lee is Ph.D. candidate of Political Science at University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. She served as a researcher at the Korea National Diplomatic Academy. Her areas of research interest include regional conflicts, nuclear weapons, and alliance politics.

Jaeseok Cho is a lecturer of University College at Korea University.

Moonyoung Kim is a Ph.D. in Political Science at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.