Introduction

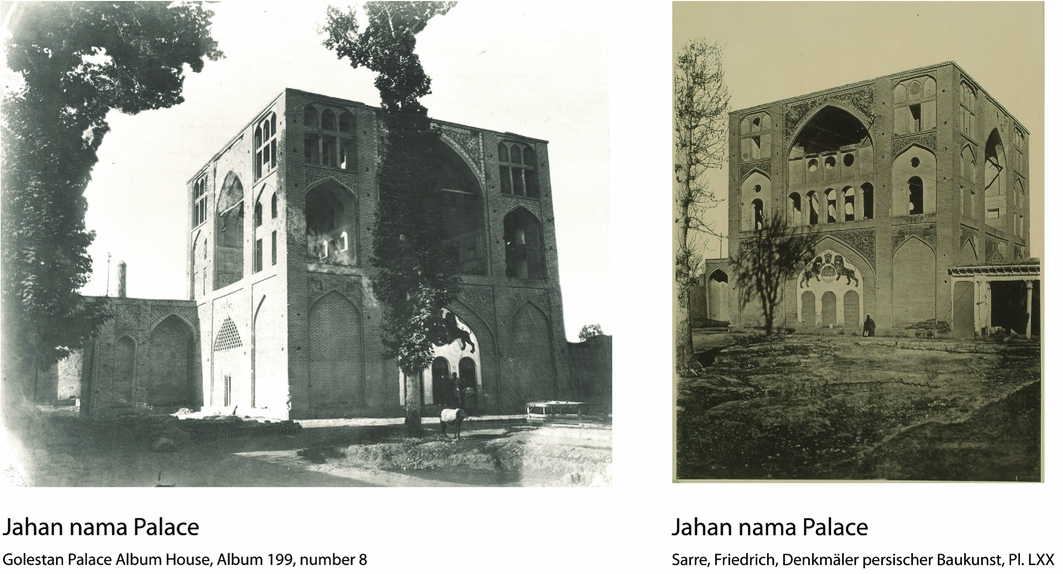

Isfahan in central Iran was selected as a capital city by both the Seljuk (AD 1040–1157) and the Safavid (AD 1501–1722) dynasties. During the Safavid period, and under Shah Abbas I (AD 1571–1629) in particular, the city was greatly expanded with important new quarters including Naqsh-e Jahan Square (AD 1590–1595). Running north to south, a new avenue or boulevard called the Charbagh (Ḵiyābān-e Čahārbāğ) was also constructed (AD 1595–1596) (Figure 1), serving as both a leisure or tourist attraction outside the city walls, and to connect some of the new capital's institutions. It extended from the Dowlat Gate to the entrance of a garden and palace named Hazārjarib (Figure 1) (Emrani Reference Emrani2012: 123). Down the middle of the avenue was a channel that fed water to a series of pools of various shapes. There were seven or eight pools, the first of which was square-shaped and was constructed close both to the Dowlat Gate and a three-storey pavilion (Figure 2), which provided a panoramic view of the Charbagh and its surrounding gardens (Tavernier Reference Tavernier1678: 155; Chardin Reference Chardin1811: 23–25; Della Valle Reference Della Valle1843: 455). As a result of this view, this building, described in the Safavid and Qajar itineraries and historical texts, was called the Jahānnamā Palace or ‘World Showcase’ (Taḥwildār Eṣfahāni Reference Taḥwildār Eṣfahāni1963: 41). The palace was demolished in 1896 by Zell-al Soltān (The Sultan's Shadow), the Governor of Isfahan (Jāberi Anṣāri Reference Jāberi Anṣāri1942: 325). Its location, however, is recorded in plans by Engelbert Kaempfer and on a map of Charbagh drawn by Pascal Cost, and there are also photographs of the palace dating back to the Qajar period (Figure 2) (Alemi Reference Alemi and Daneshvari2005: 2, 20; Golestan Palace Album House, album 199, number 8; Sarre Reference Sarre1901: pl. lxx).

Figure 1. Parts of Dowlat Ḵāna and Charbagh Street in the modern city of Isfahan. The Jahānnamā Palace is located in the northern part of Charbagh Street.

Figure 2. Photograph of the Jahānnamā Palace during the Qājār period prior to its destruction.

As a part of development work, including the construction of the subway system beneath Charbagh Street, the first archaeological investigation at the probable site of the Jahānnamā Palace was carried out from February to May 2015. The excavations covered around 300m2 and revealed not only structures of Safavid date, but also remains of the pre-Safavid and pre-Islamic periods.

The post-Safavid period

The most important discovery relating to the post-Safavid period is a coffeehouse located in the northern part of the excavated area, consisting of walls in pisé (Figure 3). The main artefacts found in this section include examples of hukka vases, opium pipes, saucers and a clay pipe. The hukkas are made of multi-coloured pottery typical of the Qajar dynasty (Lane Reference Lane1971: pl. 62B, 91). The existence of a coffeehouse behind the Jahānnamā Palace at this time is also recorded in contemporary newspapers and documents (Rajaii Reference Rajaii2004: 183).

Figure 3. Parts of the coffeehouse located in the northern part of the area under investigation. The walls are mud-brick and pisé. Beneath this structure is an earlier diagonal stone wall between 0.3 and 1m in height.

The Safavid period

The excavations revealed a number of features dating to the Safavid period. These include foundation walls of mortared brick, and cobblestones belonging to the Jahānnamā Palace (Figures 4 & 5). These footings extended for 17.6m, north to south. As the palace had an almost square plan (Figure 2), it can be safely assumed that other parts of the structure lie beneath Charbagh Street. Among important artefacts related to the Jahānnamā Palace are the cuerda seca, or seven-colour, tiles with arabesque and human motifs, and the stucco work of varied colours and patterns similar to others used in Safavid monuments.

Figure 4. a) The first pool of Charbagh Street, in front of the Jahānnamā Palace; b) four footings of Jahānnamā Palace; c) water channel for the Charbagh stream.

Figure 5. Some of the archaeological discoveries in the northern parts of Jahānnamā Palace (left); overlapping structures of stone and brick related to the pre-Safavid era, which subsequently appear to have been reused as the foundations for the Safavid-period palace (right); the remains of an oven are also on the right of this structure.

Other features identified are the most northerly of the Charbagh's pools (lined with mortared brick) and a diagonal wall of brick and stone (Figures 3 & 4). The square pool, lying at the start of the avenue, was positioned on the central axis of the palace and about 2.5m distant from it; this matches Chardin's (Reference Chardin1811) description (Figure 4). Flowing fromthe south, water passed over a cascade into the pool and then continued through a duct to the north and water pipes to the east and west (Figure 4). A diagonal wall, aligned north-west to south-east, was located in the northernmost part of the site (Figure 3). According to the descriptions of Kaempfer and other travellers, this location coincides with a road near the city wall (Alemi Reference Alemi and Daneshvari2005: 15; Babaie Reference Babaie2008: 80). Further excavation of this feature may improve our understanding of it and guide us to the location of the eleventh-century city wall.

The pre-Safavid era

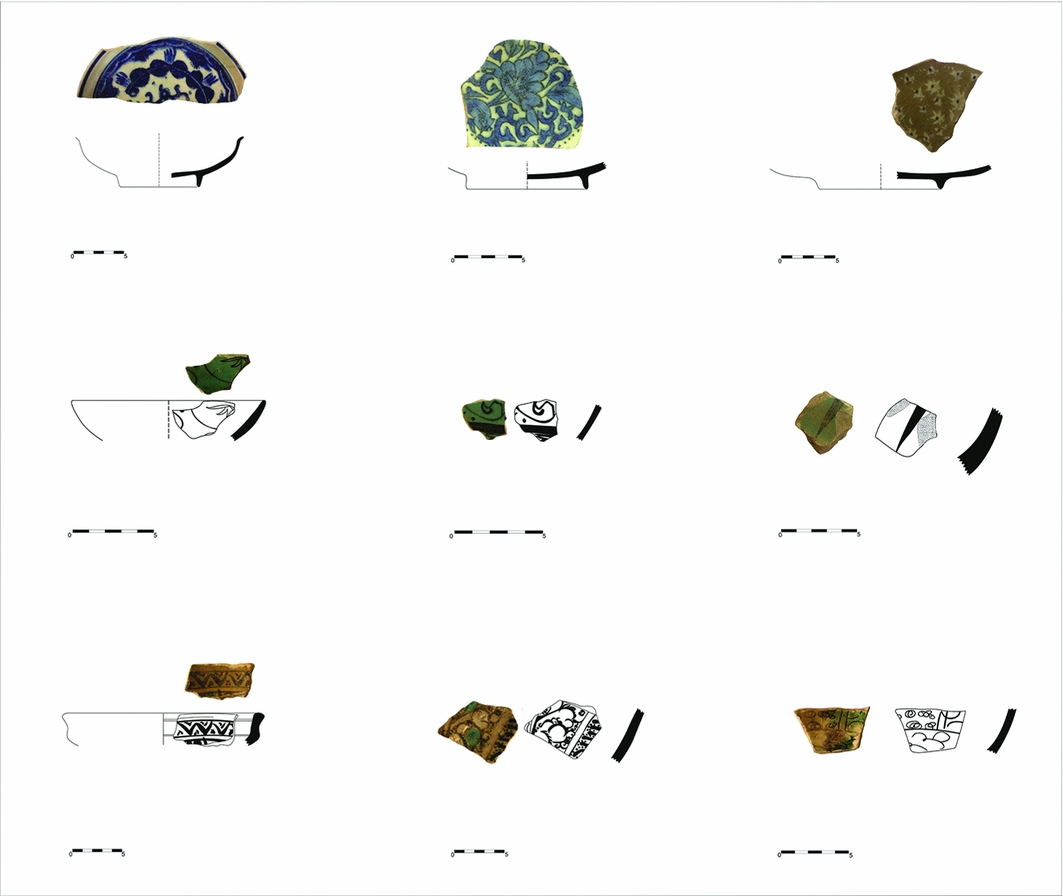

Beneath the Safavid layers, in the eastern part of the site, there are two overlapping structures of stone and brick, including the remains of an oven, around 0.7m in diameter, made of clay and used for making food or boiling water, and sherds dating from the ninth to seventeenth centuries (Figures 3 & 6). It seems that during the Safavid period, these structures were reused as foundations. In addition, pottery sherds and brick have been dated using thermo-luminescence to the first millennium BC and the late Sasanian period.

Figure 6. Pottery sherds of the ninth to seventeenth centuries, found during excavation at Jahānnamā.

Conclusion

Many of the cities of Iran have long histories resulting in rich and complex archaeological deposits. When undertaken, urban excavations are conducted in the context of time-limited rescue projects in advance of development. The results from Isfahan demonstrate the importance of such investigations for our understanding of the historical cities of Iran. The discovery of the remains of the Jahānnamā Palace and one of the Charbagh Street pools, in combination with the maps and descriptions provided by historians and travellers, provides a framework for the planning of future investigations and the identification of related features of the Safavid city such as additional pools and the entrances of the palaces on both sides of Charbagh Street. The discovery of pre-Safavid structures and pre-Islamic material also underlines the importance of this part of the Isfahan Plain during earlier periods.