1 Introduction

High-energy and high-intensity mid-infrared (MIR) lasers in the 3–5 μm range have various applications in medical laser surgery, remote sensing of atmospheric constituents, scientific material processing, national defense and differential-absorption light detection and ranging (DIAL)[ Reference Kernal, Fedorov, Gallian, Mirov and Badikov 1 – Reference Mirov, Moskalev, Vasilyev, Smolski, Fedorov, Martyshkin, Peppers, Mirov, Dergachev and Gapontsev 3 ]. The DIAL techniques for achieving high sensitivity and long-range detection require an MIR laser source with high energy, short pulse width, tunable wavelength and high beam qualities[ Reference Foltynowicz and Wojcik 4 ]. There are mainly two available ways to meet such requirements: the optical parametric oscillator (OPO) and optical parametric amplifier (OPA)[ Reference Haakestad, Fonnum and Lippert 5 , Reference Wei, Tian, Zhou, Yi, Zhang, Xiong, Ren, Wang, Wang, Wu, Zhou, Lu and Shang 6 ] and transition-metal (TM)-doped II-VI chalcogenide lasers (such as Cr:ZnSe and Fe:ZnSe)[ Reference Mirov, Moskalev, Vasilyev, Smolski, Fedorov, Martyshkin, Peppers, Mirov, Dergachev and Gapontsev 3 ], and their combinations[ Reference Li, Yang, Liu, Ya and Ju 7 , Reference Kanai, Kaksis, Pugžlys, Baltuška, Okazaki, Yasuhara and Tokita 8 ]. Due to the broad absorption and emission band cooperating with its large cross-section, Fe:ZnSe has achieved tremendous development in high-average-power (35 W at 100 Hz[ Reference Martyshkin, Fedorov, Mirov, Moskalev, Vasilyev and Mirov 9 ] and 105 W at 250 Hz[ Reference Wu, Zhou, Zhou, Ren, Zhang, Wei, Shang, Wang, Leng, Dai, Yi, Tang and Chen 10 ]), continuous wave (CW) (9.2 W[ Reference Martyshkin, Fedorov, Mirov, Moskalev, Vasilyev, Smolski, Zakrevskiy and Mirov 11 ]), high-energy (single shot 10.6 J with long pulse duration of approximately 1 ms[ Reference Kozlovsky, Korostelin, Podmar'kov, Skasyrsky and Frolov 12 ], 1.67 J with pulse duration of about 200 ns[ Reference Velikanov, Gavrishchuk, Zaretsky, Zakhryapa, Ikonnikov, Kazantsev, Kononov, Maneshkin, Mashkovskii, Saltykov, Firsov, Chuvatkin and Yutkin 13 ]), ultra-fast operations (~15 GW peak power, 1.1 W average power with 247 fs duration[ Reference Marra, Zhou, Wu and Chang 14 ]) and coupled-cavity design[ Reference Kozlovsky, Butaev, Korostelin, Leonov and Frolov 15 , Reference Leonov, Frolov, Korostelin, Skasyrsky and Kozlovsky 16 ] in the last decade.

For prospective high-energy MIR pulses in the ns time scale, Fe:ZnSe lasers gain-switched by electric-discharge hydrogen fluoride (HF) lasers[ Reference Velikanov, Gavrishchuk, Zaretsky, Zakhryapa, Ikonnikov, Kazantsev, Kononov, Maneshkin, Mashkovskii, Saltykov, Firsov, Chuvatkin and Yutkin 13 ], Q-switched Er-doped solid-state lasers[ Reference Velikanov, Gavrishchuk, Zakharov, Kozlovsky, Korostelin, Lazarenk, Maneshkin, Podmar'kov, Saltykov, Skasyrsky, Frolov, Tsykin, ChuvatkinI and Yutkin 17 ], OPOs[ Reference Li, Yang, Liu, Ya and Ju 7 ] and directly Q-switched systems[ Reference Uehara, Tsunai, Han, Goya, Yasuhara, Potemkin, Kawanaka and Tokita 18 ] have been implemented. It is in common agreement that the generation energy of Fe:ZnSe lasers is primarily limited by the low energy capabilities of the employed solid-state lasers at the wavelengths within the absorption spectrum under the conditions of short pulse operation. In contrast, the HF laser has sufficient generation energy with 100–150 ns duration and high repetition frequencies. Most high-energy Fe:ZnSe lasers in the ns-width scale are pumped by HF lasers at present[ Reference Velikanov, Gavrishchuk, Zaretsky, Zakhryapa, Ikonnikov, Kazantsev, Kononov, Maneshkin, Mashkovskii, Saltykov, Firsov, Chuvatkin and Yutkin 13 ]. However, the complexity and toxicity of HF lasers limit the applications, and thus all solid-state lasers are preferable. In addition, their pulse duration of 100–150 ns (although shorter than the upper-level lifetime of Fe:ZnSe at room temperature) is too wide for high-peak-power intensity applications. The waveform of the HF-pumped Fe:ZnSe laser pulses sometimes exhibits a spike-like structure (a sharp spike followed by a much longer tail) because of the relaxation oscillation induced by the comparatively long pulse duration[ Reference Gavrishchuk, Ikonnikov, Kazantsev, Kononov, Rodin, Savi, Timofeeva and Firsov 19 , Reference Xu, Pan, Chen, Chen, He, Zhang, Yu, Sun and Zhang 20 ]. To achieve a much shorter pulse width of sub-nanoseconds in the single-pulse regime, Ghimire et al. [ Reference Ghimire, Danilin, Martyshkin, Fedorov and Mirov 21 , Reference Ghimire, Danilin, Martyshkin, Fedorov and Mirov 22 ] used a 2.98 μm idler beam from a potassium titanyl arsenate (KTA)-OPO to pump a room-temperature Fe:ZnSe laser. The single-spike pulse width of the approximately 4.5 μm laser was only 0.89 ns with an output energy of 1.05 mJ when the pump energy was 16 mJ and the pump pulse duration was 9 ns.

Recently, we successfully demonstrated a high-efficiency non-critical phase-matched (NCPM) KTA OPO and OPA system, which delivered 293 mJ single-pulse energy at 3.47 μm with a pulse width of approximately 4 ns at 10 Hz repetition rate[ Reference Wei, Tian, Zhou, Yi, Zhang, Xiong, Ren, Wang, Wang, Wu, Zhou, Lu and Shang 6 ]. The beam profile was square with quasi-uniform distribution. Looking into the absorption spectrum band of Fe:ZnSe, the absorption peak of which is located at approximately 3.1 μm, the absorption cross-section of 3.47 μm is comparable (slightly smaller) with that of 2.65–2.94 μm where most Er-doped laser emission is located. We think the NCPM KTA OPO and OPA system might be a more advanced pump source for several ns-scale Fe:ZnSe lasers compared to Q-switched Er lasers. The output energy of flash lamp-pumped Q-switched Er lasers was significantly higher, but the pulse width was wider and the efficiency was much lower[ Reference Karki, Fedorov, Martyshkin and Mirov 23 , Reference Martyshkin, Fedorov, Hamlin and Mirov 24 ]. For laser diode (LD)-pumped Q-switched Er lasers, the highest output energy was 82 mJ at 2.67 μm with a pulse width of 13 ns and a repetition rate of 20 Hz[ Reference Pushkin, Slovinsky, Shakirov and Potemkin 25 ].

Besides the potential high-energy output ability, the 3.47 μm KTA OPO and OPA have the following unique advantages. Firstly, the quantum efficiency (~85%) is obviously improved by reducing the wavelength difference between the pump and Fe:ZnSe lasers. For instance, the quantum efficiency could be increased by 131% and 118% compared to 2.65 μm erbium-doped yttrium lithium fluoride (Er:YLF) and 2.94 μm erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Er:YAG) lasers, respectively. Secondly, the NCPM KTA OPO and OPA have benefits in many aspects, such as utilization of the largest effective nonlinear coefficient and using a longer crystal due to the absence of the walk-off effect, large acceptable spectral width and angle and high damage threshold. It has great potential to achieve high-energy and high-efficiency output when pumped by mature 1 μm lasers. Thirdly, as the pump laser with large beam size for Fe:ZnSe, high beam qualities are not as important as the beam distribution uniformity, which is helpful in preventing hot-spot peak damage. The avoidance of additional and complex beam quality control technology[ Reference Meng, Li, Cong, Zhao, Wang, Liu and Liu 26 ] makes it easier to increase the MIR output energy. Finally, the 3.47 μm output wavelength perfectly matches with the absorption peak of Fe:CdMnTe[ Reference Jelínková, Doroshenko, Jelínek, Šulc, Němec, Osiko, Kovalenko and Terzin 27 ], Fe:ZnMgSe[ Reference Doroshenko, Osiko, Jelínková, Jelínek, Šulc, Němec, Vyhlídal, Čech, Kovalenko and Gerasimenko 28 ] crystals, whose emission spectra are longer at up to 6 μm.

In this paper, we used the 3.47 μm KTA OPO and OPA to pump Fe:ZnSe crystal for the first time. To compensate the lower absorption cross-section, a bilateral diffusion-doping polycrystalline Fe:ZnSe was utilized for sufficient pump absorption. The size of the pump beam with uniform square distribution was optimized considering the transverse parasitic oscillation (TPO), nonlinear transmittance and damage threshold at the high-energy pump density. The output pulse energy of the Fe:ZnSe laser at 120 K was 86 mJ with a central wavelength of approximately 4.05 μm and a single pure pulse width of 6.7 ns at 10 Hz. The corresponding slope efficiency with respect to the absorbed pump energy was 70.7%, which is the highest slope efficiency for Fe:ZnSe lasers ever reported in the literature, to the best of our knowledge. By changing the crystal’s temperature from 80 to 300 K, the output wavelength was tuned from 3.9 to 4.5 μm in a compact and non-selective oscillator.

2 Experimental design and analysis

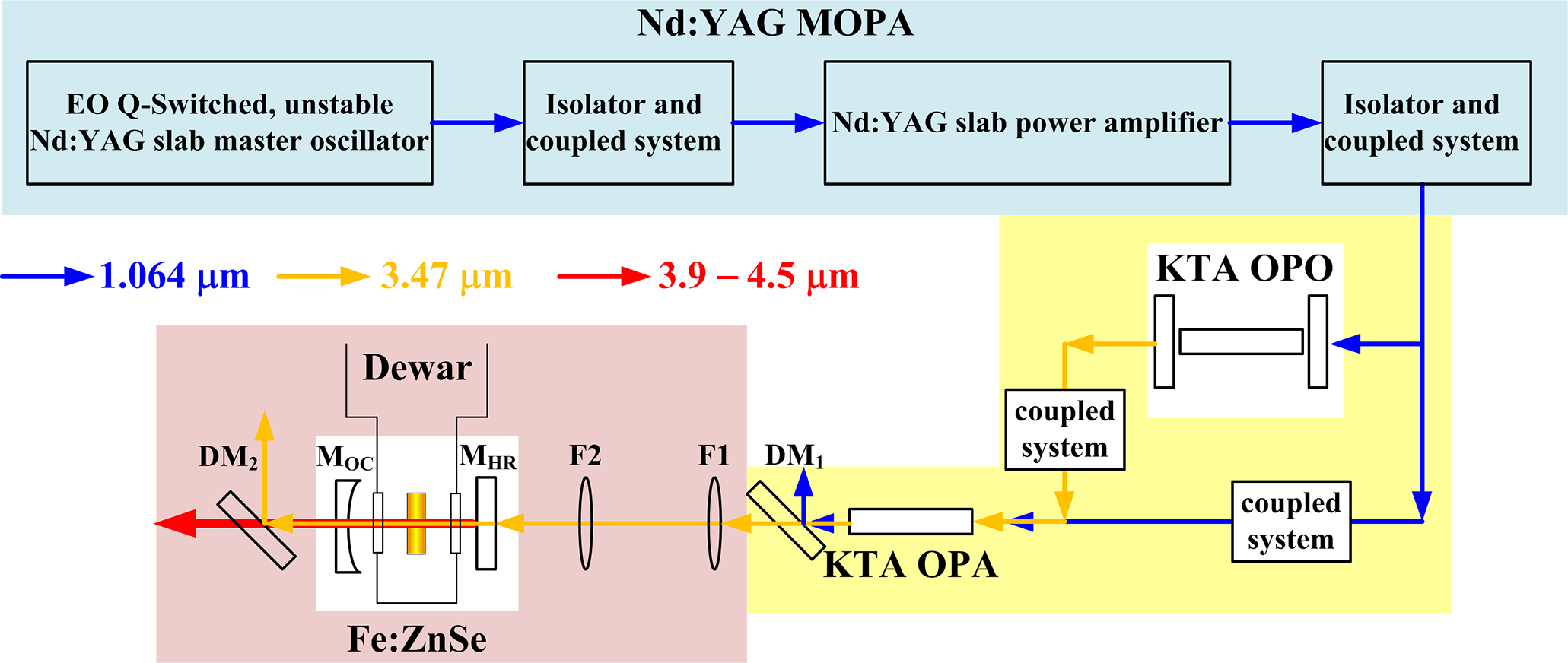

A block diagram of the experimental setup is shown in Figure 1; the whole system mainly contained three parts: the neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) slab master oscillation power amplifier (MOPA) delivering 1.064 μm laser (light blue panel), the KTA OPO and OPA generating 3.47 μm waves (yellow panel) and the Fe:ZnSe laser (pink panel). Detailed information of the former two parts can be found in Ref. [Reference Wei, Tian, Zhou, Yi, Zhang, Xiong, Ren, Wang, Wang, Wu, Zhou, Lu and Shang6]. The 3.47 μm pump pulse duration from the KTA OPO and OPA could be as short as approximately 4 ns. To reduce the damage risk of Fe:ZnSe at high-peak-power intensity, we broadened the pulse width of the 3.47 μm laser by increasing the initial pulse duration of the 1.064 μm laser from Nd:YAG MOPA. The pulse width of the 1.064 μm fundamental laser was widened to approximately 15 ns. As a direct consequence, the pulse width of the 3.47 μm wave after the KTA OPA was broadened to 8.8 ns. The other properties, such as the square uniform beam profile, output energy, spectrum and frequency, were almost the same[ Reference Wei, Tian, Zhou, Yi, Zhang, Xiong, Ren, Wang, Wang, Wu, Zhou, Lu and Shang 6 ]. The amplified 3.47 μm idler wave was separated from the 1.53 μm signal wave and 1.064 μm pump laser by a dichroic mirror (DM1) before it was injected into the Fe:ZnSe crystal. DM1 was anti-reflective (AR) coated at 3.47 μm and highly reflective (HR) coated at 1.064 and 1.53 μm for 45° incidence. The detailed parameters of the Fe:ZnSe laser were as follows: lenses F1 and F2 with AR coating at the pump wavelength were combined to reshape the pump beam to the proper size (around 7.5 mm × 7.5 mm) in Fe:ZnSe in consideration of the damage, TPO and nonlinear absorption effects. Here, MHR was a flat mirror with its AR coating at the pump wavelength and HR coating at 4.1–4.6 μm. The output coupler (OC) MOC was a plano-concave mirror (curvature radius of 500 mm) AR coated at the pump wavelength and R = 75% at 4.1–4.6 μm. The parameters of this MOC were optimal compared to other OCs available in our lab. Both MHR and MOC were AR coated at the pump wavelength, so we could pump the Fe:ZnSe crystal from both directions using two perpendicular polarization 3.47 μm lasers in the future. The polycrystalline Fe:ZnSe crystal (20 mm × 20 mm cross-section, 4 mm thick) was thermal diffusion doped from two sides to enhance the absorption at 3.47 μm. Both end faces of the crystal were AR coated at the pump and laser wavelengths to reduce Fresnel reflection loss at the surfaces. The Fe:ZnSe crystal was manufactured by our colleagues at the Institute of Chemical Materials, China Academy of Engineering Physics. The ZnSe surfaces were deposited with Fe films of 400–500 nm thickness, and were finely polished after 30 days of heating at 1373 K in fused-silica tubes filled with Ar gas. The crystal’s edges were matted and coated to be dark to suppress TPO, which proved to be an easy and effective method[ Reference Pan, Xie, Chen, Zhang and Sun 29 , Reference Ruan, Pan, Alekseev, Kazantsev, Mashkovtseva, Mironov and Podlesnikh 30 ]. The Fe:ZnSe crystal was placed in a Dewar flask whose temperature could be controlled from 77 to 300 K. It is convenient to test the wavelength tunability of Fe:ZnSe lasers by simply changing the operation temperature without additional optics adjustment. The two windows in the vacuum chamber were AR coated for the pump and laser wavelengths. The overall propagation loss of the 3.47 μm pump laser was about 14% before incident to the Fe:ZnSe crystal. Another DM (DM2) was used to separate the residual pump laser from the Fe:ZnSe laser, which was HR coated at 3.47 μm and AR coated at 3.9–4.6 μm for 45° incidence. The substrate of all the above mirrors in the Fe:ZnSe laser was CaF2.

Figure 1 Schematic of the experimental setup.

The key goal of this research is to demonstrate the efficiency improvement and energy scalability of the Fe:ZnSe laser pumped by this new source. The pump beam size became the most important factor in the experiment, which was related to the damage, TPO and nonlinear absorption effects. The beam quality dependence on the pump beam size in the cavity was not the main consideration of this study. To avoid damage (damage threshold: 2–3 J/cm2[ Reference Velikanov, Gavrishchuk, Zaretsky, Zakhryapa, Ikonnikov, Kazantsev, Kononov, Maneshkin, Mashkovskii, Saltykov, Firsov, Chuvatkin and Yutkin 13 , Reference Velikanov, Gavrishchuk, Zakharov, Kozlovsky, Korostelin, Lazarenk, Maneshkin, Podmar'kov, Saltykov, Skasyrsky, Frolov, Tsykin, ChuvatkinI and Yutkin 17 , Reference Dormidonov, Firsov, Gavrishchuk, Ikonnikov, Kononov, Kurashkin, Podlesnykh and Savin 31 , Reference Velikanov, Dormidonov, Zaretsky, Kazantsev, Kozlovsky, Kononov, Korostelin, Maneshkin, Podmar'kov, Skasyrsky, Firsov, Frolov and Yutkin 32 ]) and saturated absorption effects[ Reference Il’ichev, Shapkin, Kulevsky, Gulyamova and Nasibov 33 , Reference Yamamoto and Fedorov 34 ] in the Fe:ZnSe crystal, one should increase the pump beam size to reduce the pump energy density. In contrast, one should decrease the pump beam size to suppress the TPO effect[ Reference Pan, Xie, Chen, Zhang and Sun 29 , Reference Dormidonov, Firsov, Gavrishchuk, Ikonnikov, Kononov, Kurashkin, Podlesnykh and Savin 31 , Reference Alekseev, Andronova, Kazantsev, Kolesnikov and Podlesnikh 35 ], which could reduce the efficiency and output energy dramatically. For the above reasons, the pump beam size into the Fe:ZnSe crystal should be carefully designed.

Alekseev et al. [ Reference Alekseev, Andronova, Kazantsev, Kolesnikov and Podlesnikh 35 ] and Pan et al. [ Reference Pan, Xie, Chen, Zhang and Sun 29 ] reported the theoretical analysis and experimental results on the largest allowed pump beam size before the appearance of TPO in a Fe:ZnSe laser with high-energy operation. The pump absorption (or transmission) was fixed in their studies. However, the nonlinear transmission also depends on the pump energy density[ Reference Yamamoto and Fedorov 34 ]. To more accurately analyze the largest pump beam size with the absence of TPO for varied incident pump energy, we combined the nonlinear transmission effect and TPO threshold together in this research for the first time. The maximum allowed pump dimension can be expressed as follows[ Reference Pan, Xie, Chen, Zhang and Sun 29 , Reference Alekseev, Andronova, Kazantsev, Kolesnikov and Podlesnikh 35 ]:

$$\begin{align}{d}_{\mathrm{max}}=\frac{\sigma_\mathrm{ab}\cdot D\cdot {N}_0-\ln \left({R}_\mathrm{p}\right)}{\sigma_\mathrm{em}\cdot {N}_\mathrm{G}+{\sigma}_\mathrm{ab}\cdot {N}_0},\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{d}_{\mathrm{max}}=\frac{\sigma_\mathrm{ab}\cdot D\cdot {N}_0-\ln \left({R}_\mathrm{p}\right)}{\sigma_\mathrm{em}\cdot {N}_\mathrm{G}+{\sigma}_\mathrm{ab}\cdot {N}_0},\end{align}$$

where σ ab and σ em denote the absorption and emission cross-sections, respectively, D is the dimension of the Fe:ZnSe crystal, R p denotes the reflectivity of transverse radiation from the crystal edge, which should be quite small in our case (less than 10%) due to the matting and darkening method, and N 0 and N G are the doping concentration and threshold gain concentration, respectively. The latter can be given by the following expression:

$$\begin{align}{N}_\mathrm{G}=\frac{-\ln \left({R}_1{R}_2\cdot {T}^2\right)}{2\cdot {\sigma}_\mathrm{em}\cdot l},\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{N}_\mathrm{G}=\frac{-\ln \left({R}_1{R}_2\cdot {T}^2\right)}{2\cdot {\sigma}_\mathrm{em}\cdot l},\end{align}$$

in which R 1 and R 2 refer to the reflectivity of MHR and MOC, respectively, while l is the thickness of the Fe:ZnSe crystal and T denotes the single-pass transmittance of the pump laser into the Fe:ZnSe crystal, which can be expressed as follows[ Reference Yamamoto and Fedorov 34 ]:

in which the input pump energy density S E is given by the following:

where E in is the input pump energy, S is the pump beam area and hv p is the photon energy.

In Equation (3), T 0 represents the initial transmission, which can be expressed as follows:

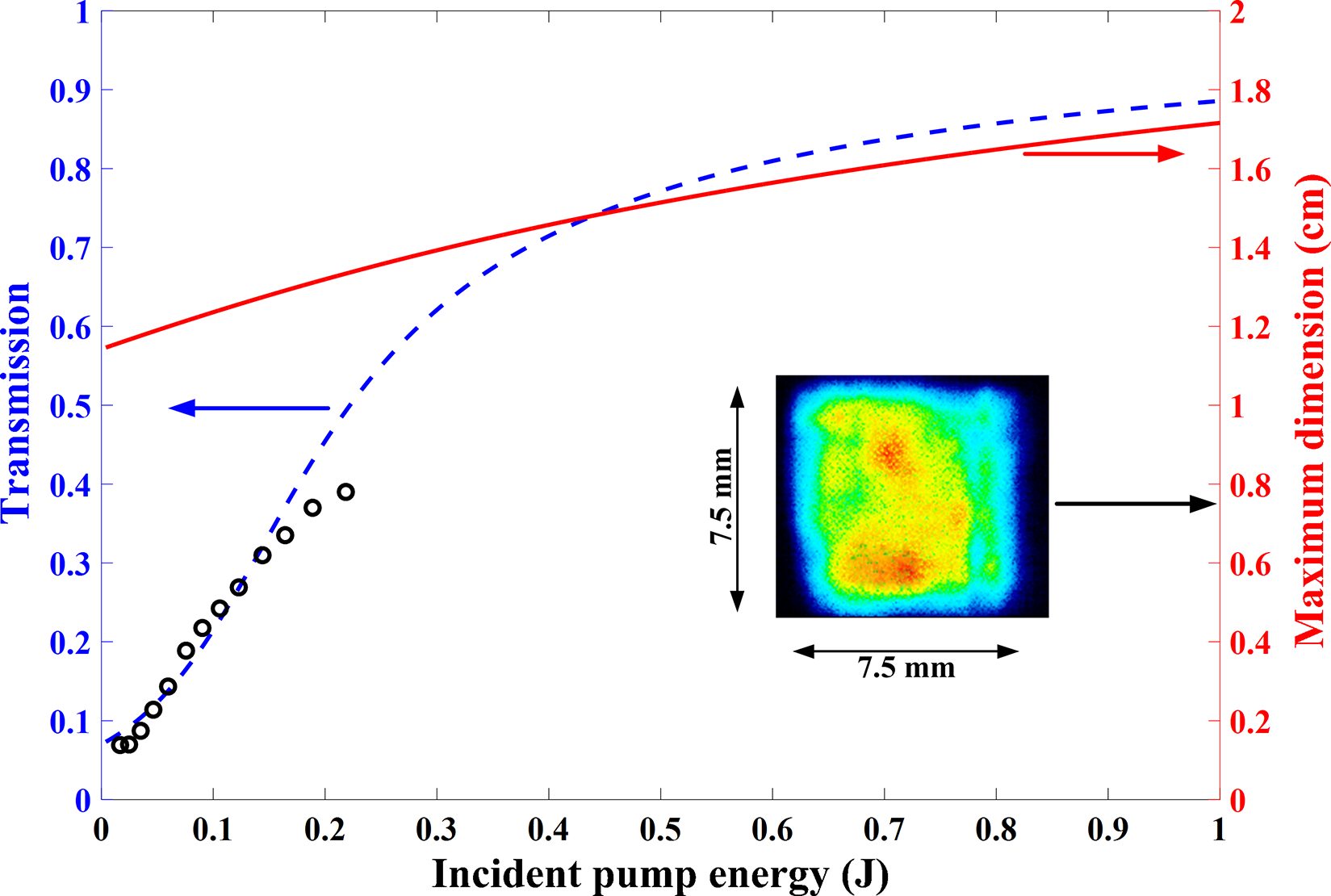

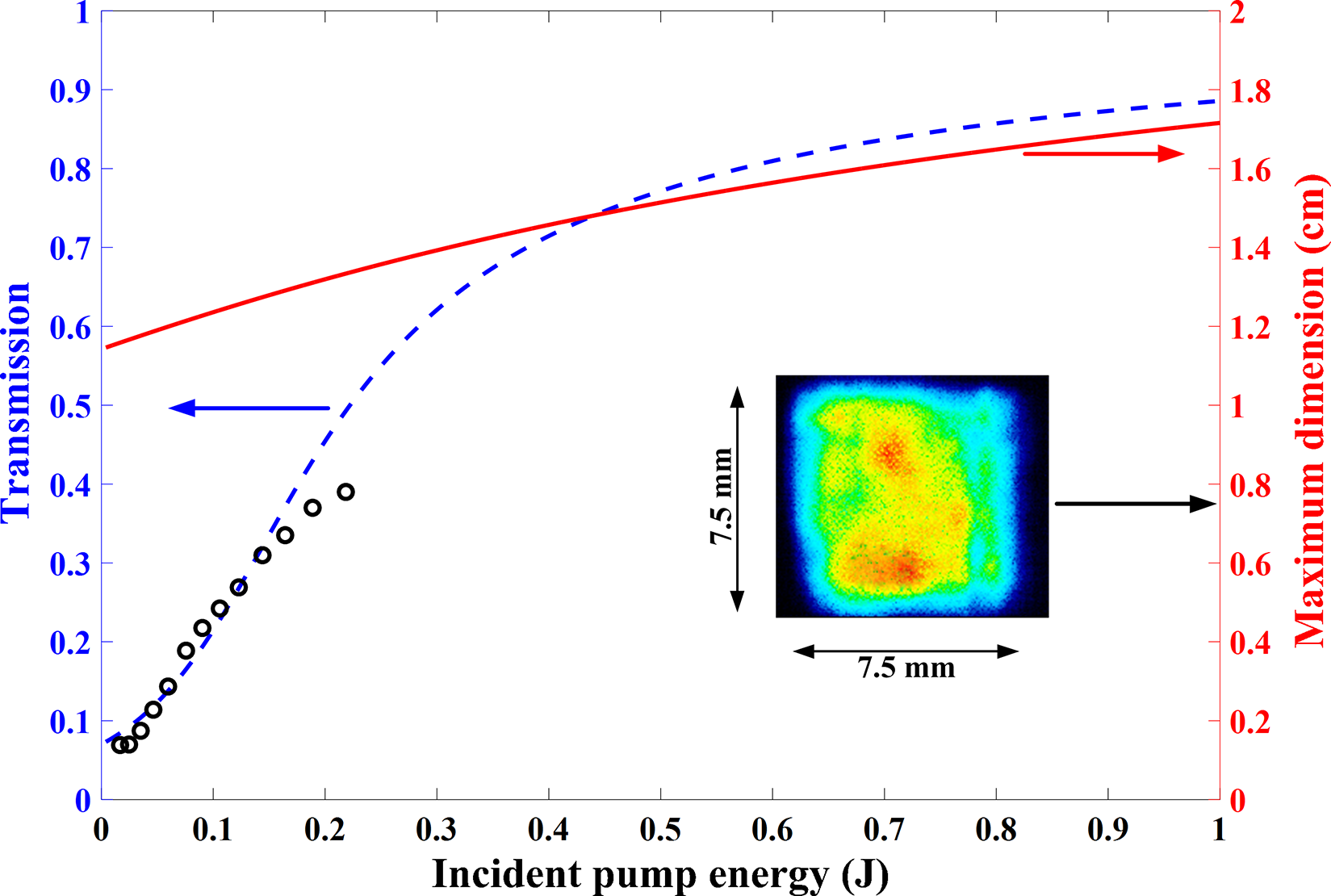

By combining Equations (1)–(5), the maximum pump dimension d max with respect to the incident pump energy can be obtained. We measured the single-pass transmittance at different pump energies to evaluate the averaged doping concentration of the bilateral doped Fe:ZnSe crystal, and also to test its damage threshold without cavity mirrors. The single-pass transmittance was 7% at low incident pump energy at 80 K, and increased to 39% at higher energy. The calculated average doping concentration (see Equation (5)) was approximately 8.86 × 1018 cm–3, taking the absorption cross-section of 0.75 × 10–18 cm2 at 3.47 μm and 80 K from Ref. [Reference Evans, Sanamyan and Berry36]. No damage to the crystal or its coatings was discovered at the highest pump energy density of approximately 0.4 J/cm2 and peak power intensity of approximately 45 MW/cm2.

The calculated maximum pump dimension (red line on the right-hand axis) and nonlinear transmission (blue dashed line on the left-hand axis) versus the input pump energy are shown in Figure 2. The black circles represent the measured single-pass transmission, which basically accorded with the theoretical calculation. The difference in pump energy higher than 0.2 J might be induced by the asymmetrical doping structure of the thermal diffusion method. To suppress TPO effectively, the pump beam size should be below the red line, where the threshold of TPO is higher than that of laser generation. It is noticeable that the pump beam size of 7.5 mm × 7.5 mm was smaller than the maximum pump dimension in theory, which meant the TPO should be well avoided in the experiment. The inset of Figure 2 shows the beam profile of the 3.47 μm pump laser at the incident energy of 218.4 mJ, which was measured by an MIR camera from DataRay company (WinCamD, FIR2-16-HR). The quasi-uniform distribution eliminated hot-spot and central peak intensity, such as Gaussian beams, which were more likely to damage the Fe:ZnSe crystal, although some comparatively stronger areas still existed due to the initial imperfect uniformity of the 1.064 μm pump profile.

Figure 2 Single-pass transmission (blue dashed line) and maximum dimension (red solid line) versus the incident pump energy. The black circles represent the measured transmission data, and the inset is the beam profile of the 3.47 μm pump laser at 218.4 mJ.

The design of a proper pump beam size should consider not only the avoidance of TPO (below the red line in Figure 2), insufficient absorption (right-hand side of the blue dashed line in Figure 2) and damage to the Fe:ZnSe crystal but also cavity matching with specific OCs for high-efficiency output. Increasing the pump beam size (still below the red line in Figure 2) would increase the laser oscillation threshold and affect the output efficiency. Another defect of this large pump beam configuration was the increase of the Fresnel number in this short linear Fe:ZnSe cavity, which would degenerate the output beam qualities. The simulated beam quality M 2 was about 30 for the approximately 4.5 μm laser through the cavity mode-matching method. To improve the beam quality[ Reference Zhang, Xu, Pan, Zhang, Zhou, Zhao and Chen 37 ], a longer Fe:ZnSe cavity or MOPA system could be implemented with possibly compromised output efficiency.

3 Experimental results and discussion

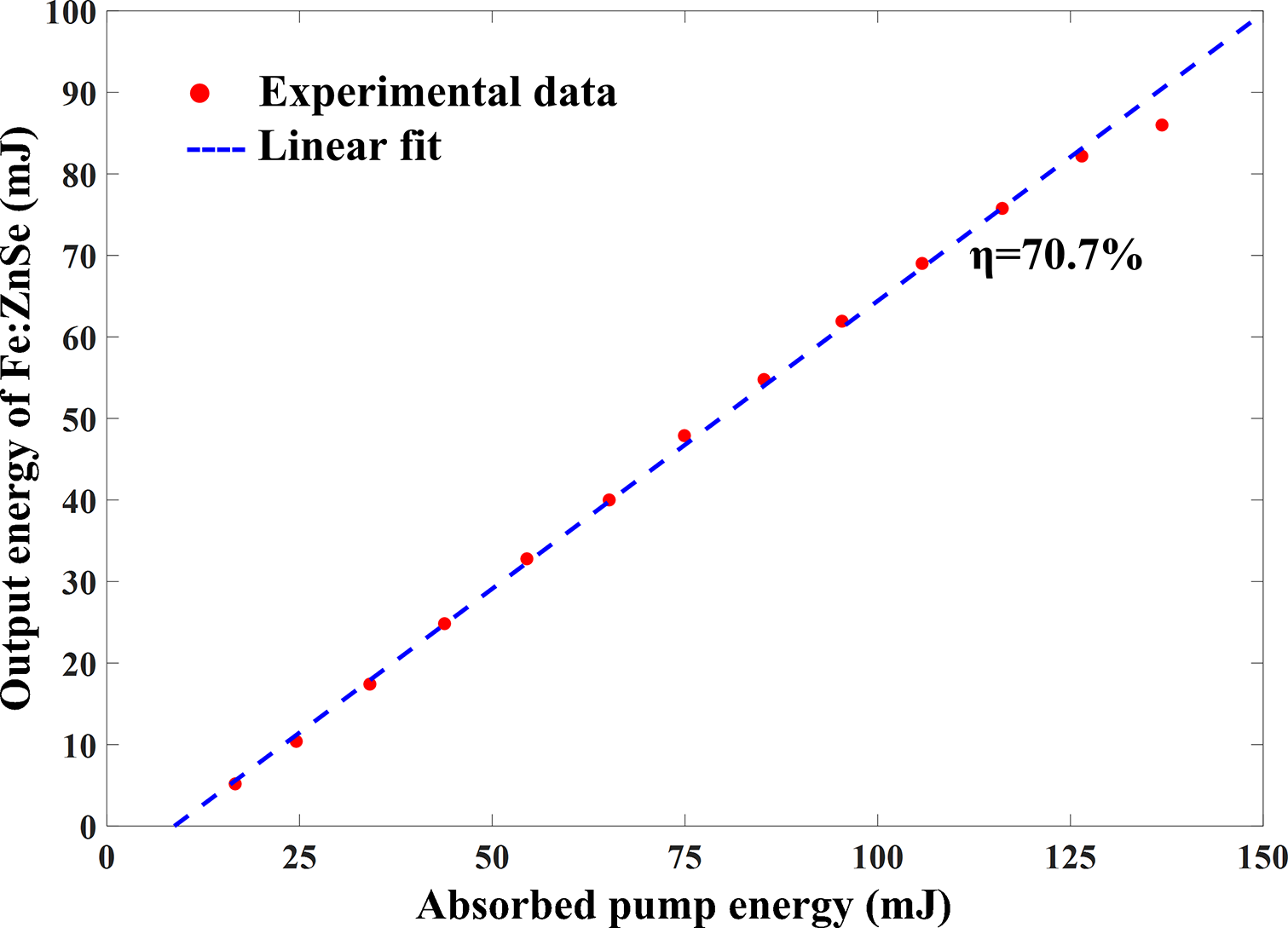

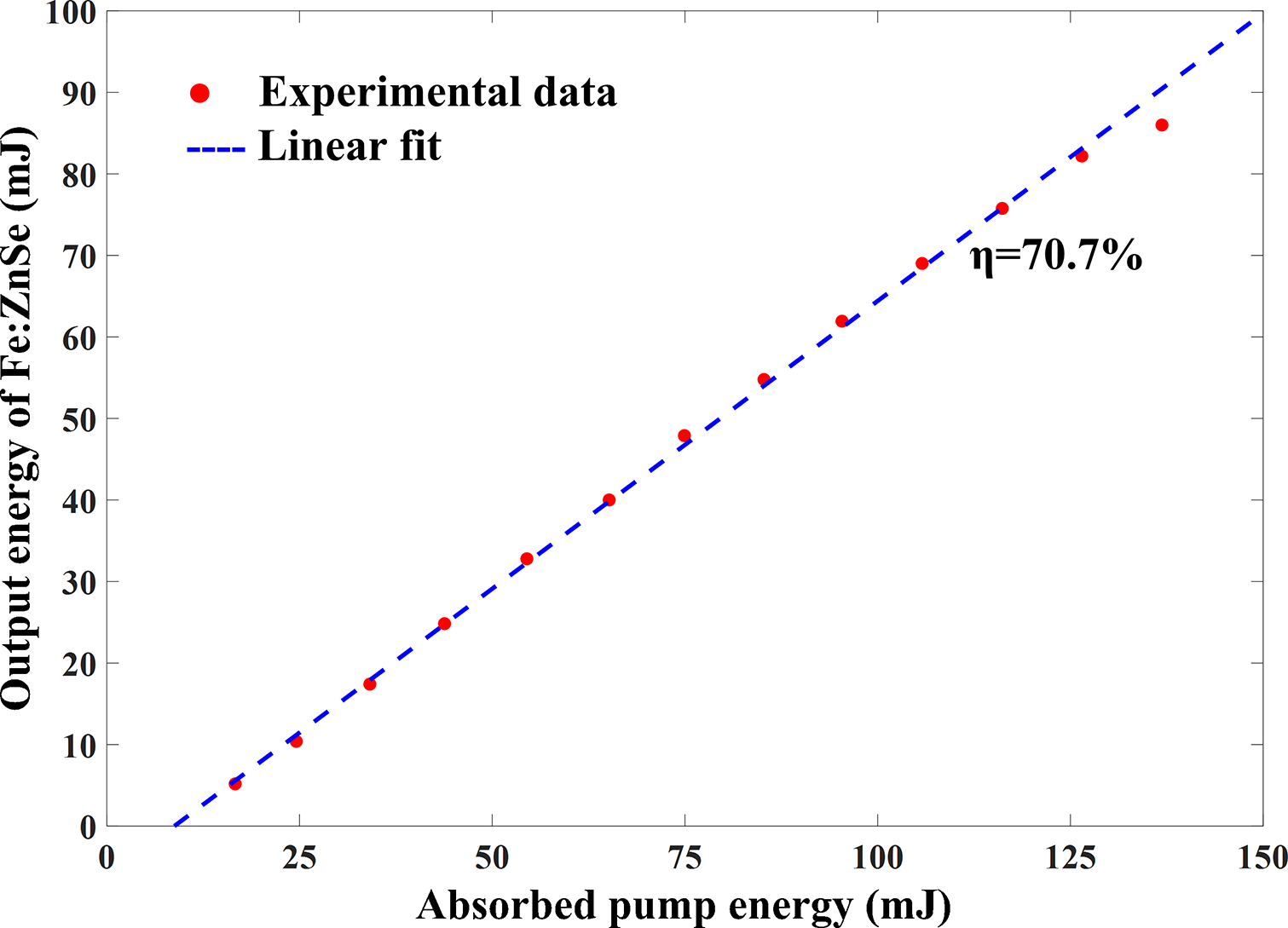

The output energy with respect to the absorbed pump energy is plotted in Figure 3 with the operation temperature of 120 K. The absorbed pump energy was calculated from the measurements of incident pump energy to the Fe:ZnSe crystal and the residual unabsorbed pump energy after DM2 during the lasing operation, which showed a slight absorption enhancement. The output energy increased linearly with the increase of the absorbed pump energy. The maximum output energy was 86 mJ with the absorbed pump energy of 136.8 mJ, and the corresponding optical-to-optical (o-o) efficiency was 62.8%. There seems to be a roll-over trend near the last point. We found that it was not because of the saturation effect or TPO appearance but rather the trivial damage inside Fe:ZnSe[ Reference Velikanov, Dormidonov, Zaretsky, Kazantsev, Kozlovsky, Kononov, Korostelin, Maneshkin, Podmar'kov, Skasyrsky, Firsov, Frolov and Yutkin 32 ]. The damage was not obviously noticeable with the naked eye, and could only be discovered through strong light at a certain angle. The phenomenon that Fe:ZnSe would be more likely to be damaged during lasing operation was also reported by other authors[ Reference Velikanov, Gavrishchuk, Zaretsky, Zakhryapa, Ikonnikov, Kazantsev, Kononov, Maneshkin, Mashkovskii, Saltykov, Firsov, Chuvatkin and Yutkin 13 , Reference Dormidonov, Firsov, Gavrishchuk, Ikonnikov, Kononov, Kurashkin, Podlesnykh and Savin 31 ], who suggested that the Fe:ZnSe crystal was damaged by radiation of oscillated laser (with higher intra-cavity intensity) rather than the pump radiation. The instinct breakdown mechanism remains unknown, and the Fe:ZnSe damage threshold in both forms of energy density (1–3 J/cm2) and peak power intensity (several tens of MW/cm2[ Reference Velikanov, Dormidonov, Zaretsky, Kazantsev, Kozlovsky, Kononov, Korostelin, Maneshkin, Podmar'kov, Skasyrsky, Firsov, Frolov and Yutkin 32 ]) needs further investigation at short-pulse operations.

Figure 3 Output energy of Fe:ZnSe versus the absorbed pump energy with linear fitting.

By linearly fitting the experimental data (without the last point), the slope efficiency was 70.7%, which is the highest for Fe:ZnSe lasers ever reported in the literature. Taking into account the ratio of the photon energies of the 3.47 μm pump and 4.05 μm Fe:ZnSe lasers, this corresponds to 82.5% of the quantum efficiency. For comparison, the representative works achieving high slope-efficiency Fe:ZnSe lasers are 66.3%[ Reference Shen, Wan, Zhu, Chai, Wang and Huang 38 ], 59%[ Reference Pushkin, Migal, Uehara, Goya, Tokita, Frolov, Korostelin, Kozlovsky, Skasyrsky and Potemki 39 ] and 58% (waveguide configuration)[ Reference McDaniel, Lancaster, Evans, Kar and Cook 40 ] in CW operation pumped by Er fibers, 58.8% in CW operation pumped by Cr:CdSe[ Reference Kozlovsky, Akimov, Frolov, Korostelin, Landman, Martovitsky, Mislavskii, Podmar'kov, Skasyrsky and Voronov 41 ], 53% in short-pulse operation gain-switched by a HF laser[ Reference Dormidonov, Firsov, Gavrishchuk, Ikonnikov, Kazantsev, Kononov, Kotereva, Savin and Timofeeva 42 ] and 53% in long-pulse operation pumped by free-running Er:YAG[ Reference Kozlovsky, Korostelin, Podmar'kov, Skasyrsky and Frolov 12 ]. The previous highest slope efficiencies were mainly based on CW operation. We achieved a new record of slope efficiency in a short-pulse Fe:ZnSe laser by utilizing a longer pump wavelength, resulting in a promotion of the quantum efficiency compared to the traditional shorter wavelengths near 2.9 μm.

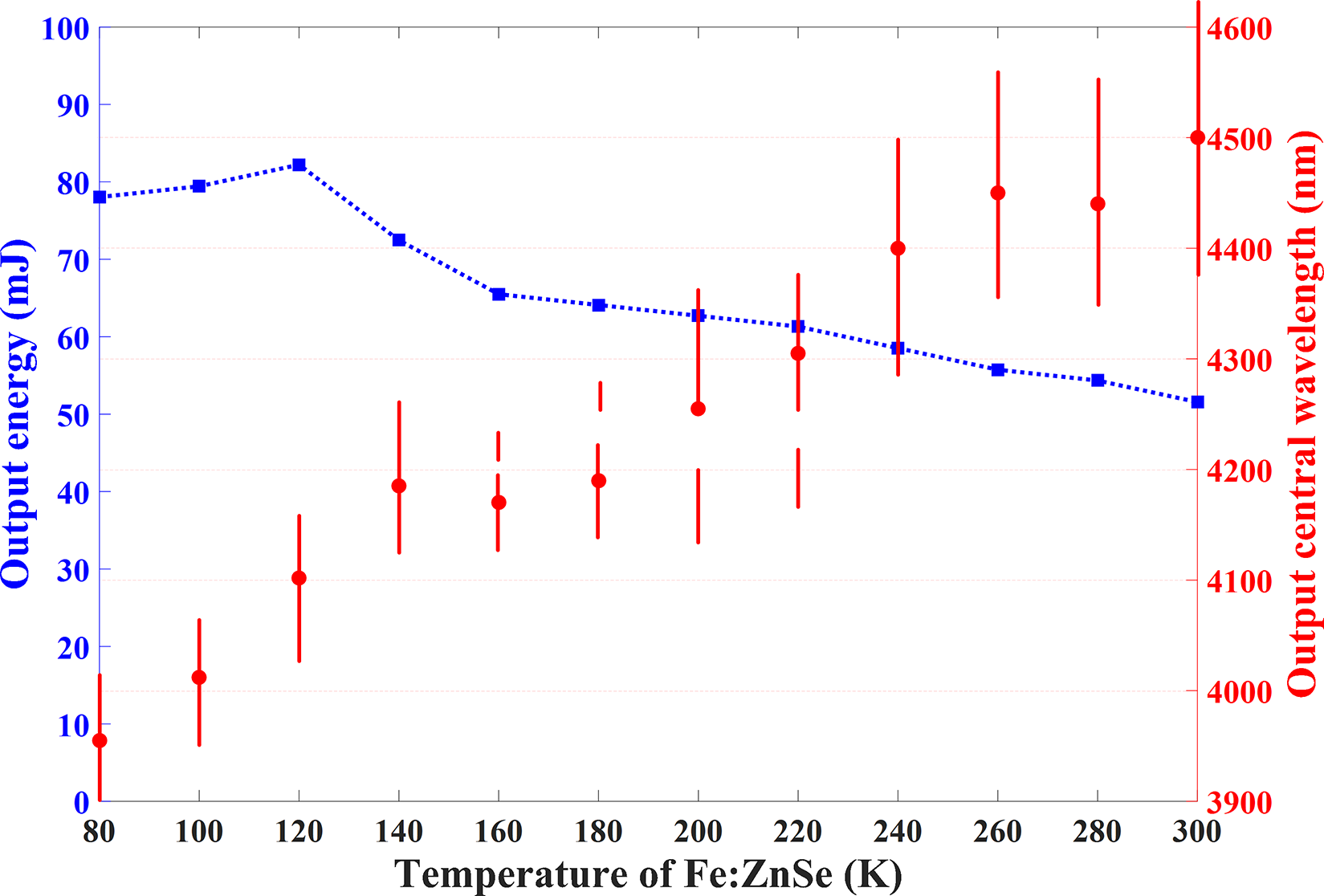

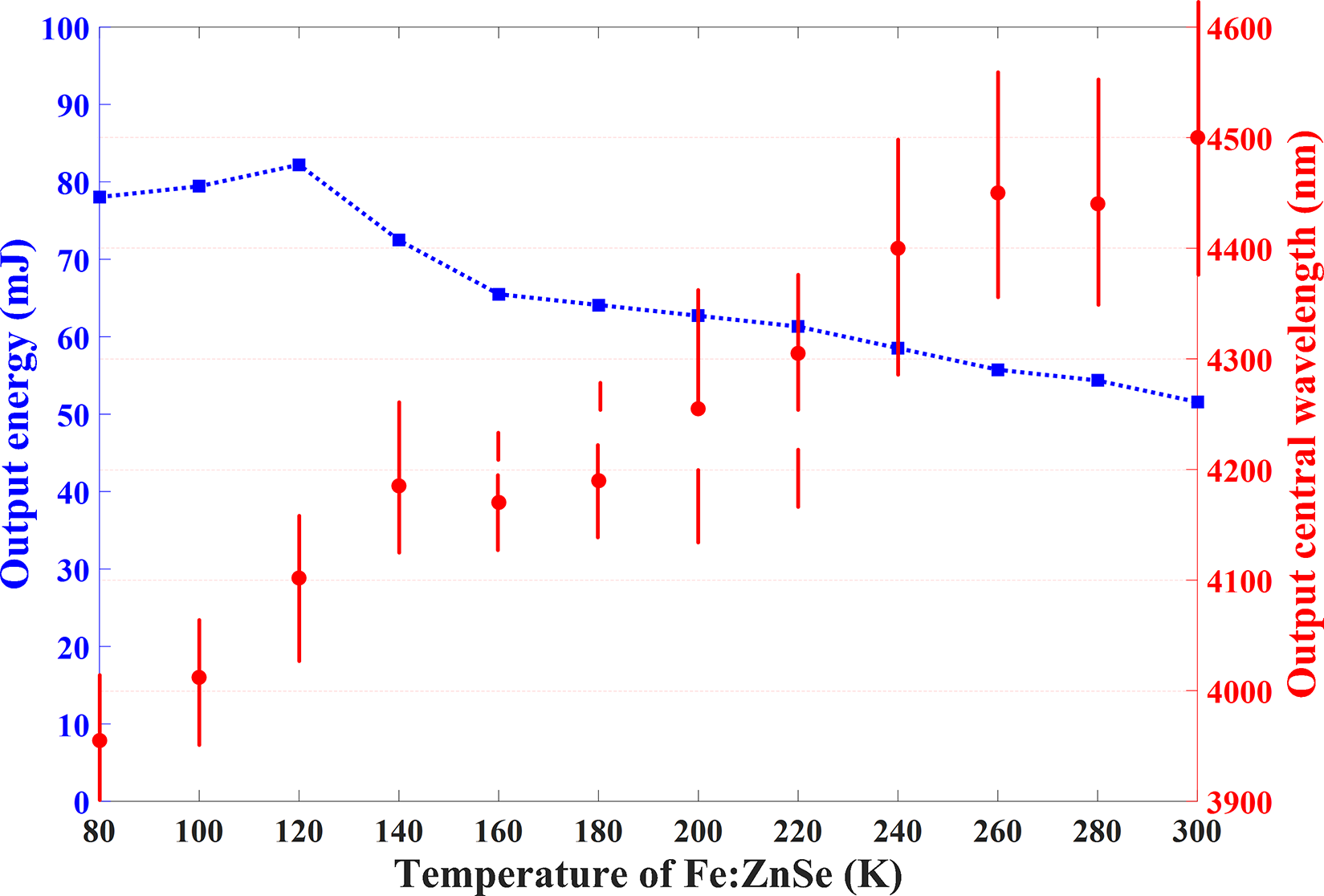

Another important feature of Fe:ZnSe is the broad wavelength tunability covering 3.8–4.8 μm[ Reference Kernal, Fedorov, Gallian, Mirov and Badikov 1 , Reference Fjodorow, Frolov, Korostelin, Kozlovsky, Schulz, Leonov and Skasyrsky 43 , Reference Fedorov, Martyshkin, Karki and Mirov 44 ]. As the pump pulse duration from the KTA OPO and OPA was only approximately 8.8 ns, liquid nitrogen cooling of the Fe:ZnSe crystal was not obligatory. However, for CW and long-pulse operation, a low temperature is needed because of the great drop of the upper-level lifetime from approximately 100 μs at 100 K to approximately 360 ns at room temperature[ Reference Kernal, Fedorov, Gallian, Mirov and Badikov 1 ] due to the multi-phonon quenching effect. This allowed us to implement the wavelength tuning of the Fe:ZnSe laser by simply changing the temperature without additional spectrum-selective elements. The output central wavelengths and corresponding output energies at different temperatures are shown in Figure 4 with the same incident pump energy of 189 mJ at 3.47 μm.

Figure 4 Output energies and central wavelengths of Fe:ZnSe at different temperatures.

With the increase of the Fe:ZnSe temperature, the output energy decreased from approximately 80 mJ at 120 K to 51.5 mJ at 300 K. The energy decrease was not as rapid as for the long-pulse operation Fe:ZnSe laser pumped by free-running Er:YAG lasers. As the pump duration was much shorter than the upper-level lifetime, room-temperature operation of the crystal should not influence output energy[ Reference Migal, Balabanov, Savin, Ikonnikov, Gavrishchuk and Potemkin 45 ]. The main reason for the energy decrease was the reduction of the absorption cross-section with the increase of temperature. The relative absorption cross-section decreased by about 1.5 times at 300 K compared to that at 80 K by an approximate estimation from Ref. [Reference Il'ichev, Bufetova, Gulyamova, Pashinin, Sidorin, Polyanskii, Kalinushkin, Gavrishchuk, Ikonnikov and Savin46]. If the absorbed pump energy was taken into account, the o-o efficiencies were 48.1% at 300 K and 50.9% at 200 K, which were comparable to the o-o efficiency of 62.8% at 120 K. The decreased emission cross-section and longer output wavelength (with lower quantum efficiency) also contributed to the efficiency drop at 300 K. The reason why the highest output energy was obtained near 120 K might be that the coating parameter of MHR and MOC was optimized for 4.1–4.6 μm, while the output wavelengths were shorter than 4.1 μm at temperatures lower than 120 K. The re-absorption at shorter wavelengths in Fe:ZnSe is also stronger[ Reference Kernal, Fedorov, Gallian, Mirov and Badikov 1 ]. The energy variation was small between 80 and 120 K. For the above reasons, the lower temperature of the Fe:ZnSe crystal pumped by the traditional approximately 2.9 μm wavelength is beneficial to improve the output energy and efficiency as compared to room-temperature operations[ Reference Velikanov, Gavrishchuk, Zakharov, Kozlovsky, Korostelin, Lazarenk, Maneshkin, Podmar'kov, Saltykov, Skasyrsky, Frolov, Tsykin, ChuvatkinI and Yutkin 17 , Reference Il'ichev, Bufetova, Gulyamova, Pashinin, Sidorin, Polyanskii, Kalinushkin, Gavrishchuk, Ikonnikov and Savin 46 ]. High slope-efficiency gain-switched Fe:ZnSe lasers are also achievable for the whole temperature range, if the cavity parameters (such as the doping of the crystal, the reflectivity of OCs and the cavity mode matching) are specifically optimized.

In addition, the approximately 4.5 μm single-pass transmission of the Fe:ZnSe crystal at room temperature was 86.4%, and the corresponding absorption coefficient was 0.365 cm–1 at approximately 4.5 μm. The absorption loss was mainly induced by the re-absorption effect overlapped with its broad lasing spectrum[ Reference Ghimire, Danilin, Martyshkin, Fedorov and Mirov 21 ], and was also influenced partially by the AR coatings and defects of the Fe:ZnSe crystal.

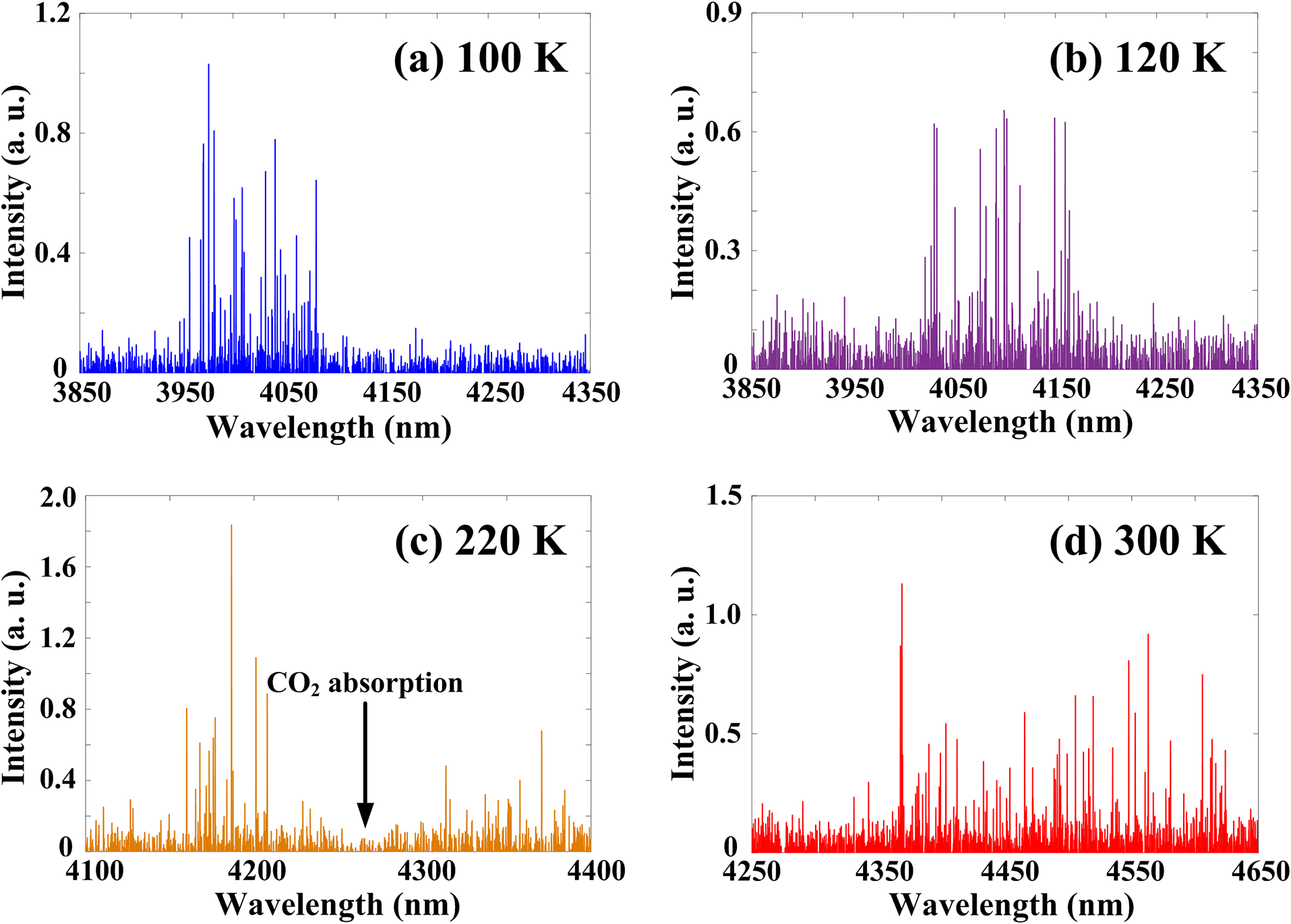

The output spectra were measured several times at each temperature, because the external triggering function of the spectrometer (Yokogawa AQ6377, wavelength range 1.9–5.5 μm, highest resolution 0.02 nm) was invalid at present, and the spectrometer could only record the spectrum by chance due to the short pulse duration and low frequency. The central wavelength was defined as the middle of the whole spectrum range (red lines in Figure 4) after summing up several measurements. The central wavelength changed from 3.95 μm at 80 K to 4.5 μm at 300 K due to the effect that resulted from higher-lying ground states being thermally populated at higher temperatures[ Reference Adams, Bibeau, Page, Krol, Furu and Payne 47 ]. Some dips near 4.25 μm in the output spectrum were discovered[ Reference Kernal, Fedorov, Gallian, Mirov and Badikov 1 ] because of the CO2 absorption. The spectrum width was also broadened with the increase of the temperature induced by the thermally activated transitions. The experimental results basically agreed with Ref. [Reference Kernal, Fedorov, Gallian, Mirov and Badikov1]. Some typical output spectra are shown in Figure 5. The full width of the spectrum range at 100 K was about 125 nm, and it was broadened to about 250 nm at 300 K. The spectrum split into two envelopes with a dip around 4.25 μm at 220 K due to the overlapping of CO2 absorption.

Figure 5 Measured output spectra of Fe:ZnSe at 100 K (a), 120 K (b), 220 K (c) and 300 K (d).

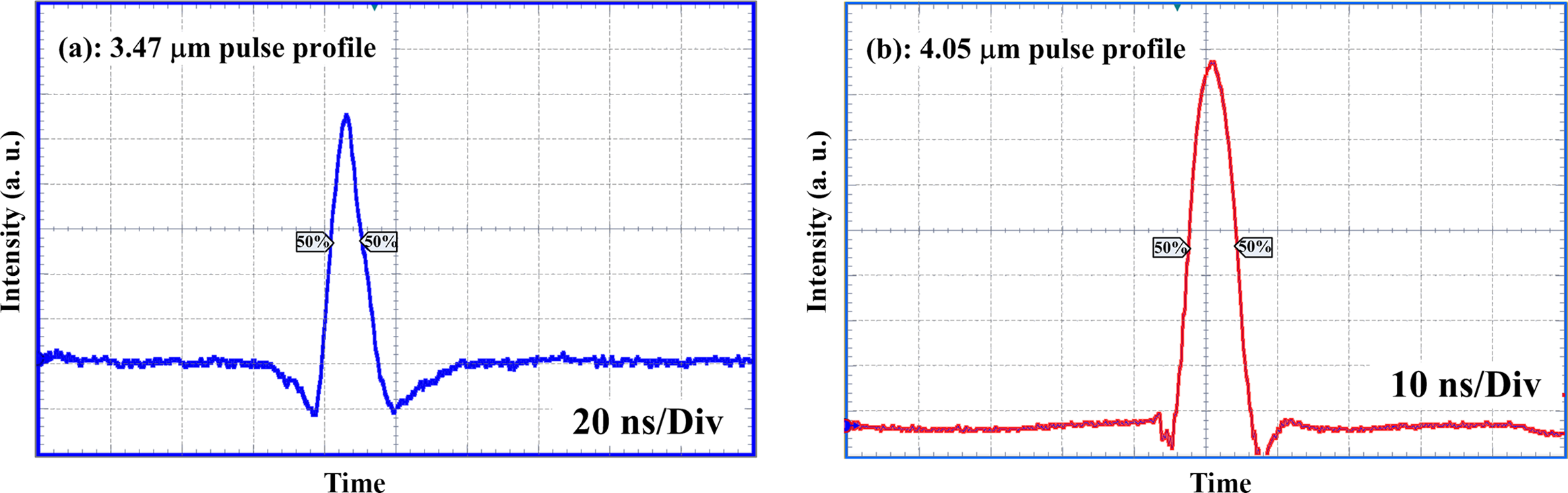

For applications requiring extreme peak power intensity, high-energy and short-pulse-width MIR lasers are urgently needed. The waveforms of the 3.47 μm pump and Fe:ZnSe lasers (at 120 K) near their maximum energies are shown in Figure 6. The temporal profiles were measured by a photodiode from the Vigo company (PVM-10.6, wavelength range 2–10.6 μm, response time ≤1 ns). The average pulse widths at FWHM (full width at half maximum) were 8.8 and 6.7 ns for the pump and Fe:ZnSe lasers, respectively. The single and pure pulse profile of the Fe:ZnSe laser was always recorded during the multiple-time measurements. Compared with other pump sources, spike-like (a sharp spike followed by a much longer tail) temporal profiles were often discovered even for short-pulse pumping of HF lasers[ Reference Gavrishchuk, Ikonnikov, Kazantsev, Kononov, Rodin, Savi, Timofeeva and Firsov 19 , Reference Xu, Pan, Chen, Chen, He, Zhang, Yu, Sun and Zhang 20 ] and Q-switched Cr,Er:YSGG (Cr and Er co-doped yttrium scandium gallium garnet) and Er:YAG lasers with pulse duration at the hundred-ns level. The tails of the pulse profile were much stronger in long-pulse pumping operation (such as free-running Er:YAG[ Reference Frolov, Korostelin, Kozlovsky, Podmar’kov and Skasyrsk 48 ] with pulse duration at the hundred-μs level) due to the much greater relaxation oscillation. In our single and pure pulse profile, the peak power of the 4.05 μm Fe:ZnSe laser was 12.8 MW, which was even higher than the J-level Fe:ZnSe lasers pumped by HF, such as 8 MW (1.2 J with 150 ns duration)[ Reference Kozlovsky, Korostelin, Podmar'kov, Skasyrsky and Frolov 12 ] and approximately 8.35 MW (1.67 J with ~200 ns duration)[ Reference Velikanov, Gavrishchuk, Zaretsky, Zakhryapa, Ikonnikov, Kazantsev, Kononov, Maneshkin, Mashkovskii, Saltykov, Firsov, Chuvatkin and Yutkin 13 ].

Figure 6 The pulse profiles of the pump and Fe:ZnSe lasers.

4 Conclusion

In conclusion, we designed a novel high-efficiency Fe:ZnSe laser that was pumped by an NCPM KTA OPO and OPA system at 3.47 μm for the first time. To the best of our knowledge, a new record slope efficiency of 70.6% was achieved through the promotion of the quantum efficiency by using the longer pump wavelength. The maximum output energy was 86 mJ at 4.05 μm with the absorbed pump energy of 136.8 mJ. The output wavelength was tunable from 3.9 to 4.6 μm by changing the temperature of Fe:ZnSe from 80 to 300 K. The dynamic absorption and TPO avoidance in Fe:ZnSe with respect to incident pump energy were investigated theoretically and experimentally. A single and pure pulse profile with a width of 6.7 ns promotes the applications for high-peak-power intensity MIR lasers. This research provides a new method to obtain high-energy, high-efficiency, short-pulse-duration and widely tunable MIR lasers, and we believe the pump energy could be scaled to the joule-level by adding amplification stages in the NCPM KTA OPA. In the future, we also plan to increase the output energy by using single-crystal Fe:ZnSe, the damage threshold of which has been tested to be much higher than that of polycrystals.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Dongmei HONG (Beijing Qifenglanda Optical Technology Development Company) for providing several kinds of mirrors for testing. The improvement of the coating on the laser-induced damage threshold was remarkable after a long-term technical discussion, revision and validation. This work was supported by the JMRH-2024 Funding of the China Academy of Engineering Physics.