The “Doomsday Machine”: A nuclear arsenal programmed to automatically explode should the Soviet Union come under nuclear attack. “Skynet”: An artificial general superintelligence system that becomes self-aware and launches a series of nuclear attacks against humans to prevent it from being shut down. “War Operation Plan Response (WOPR)”: A supercomputer that is given access to the US nuclear arsenal, programmed to run continuous war games, and comes to believe a simulation of global thermonuclear war is real. These systems appear in the movies Dr. Strangelove, The Terminator, and WarGames. However, the idea of automating nuclear weapons use—that is, creating a computer system that, once turned on, could launch nuclear weapons on its own without further human interventionFootnote 2 —is not just a Hollywood plot device.

The Soviet Union actually developed a semi-autonomous system called “Dead Hand” or “Perimeter” during the Cold War, which may still be active in some form today.Footnote 3 Once Dead Hand was activated, it monitored for evidence of a nuclear attack against the Soviet Union using a network of radiation, seismic, and air pressure sensors. Upon detecting that a nuclear weapon had been exploded on Soviet territory, it would check to see if there was an active communications link to the Soviet leadership. If the communications link was inactive, Dead Hand would assume Soviet leadership had been killed and transfer nuclear launch authority to a lower-level official operating the system in a protected bunker. Today, technology related to automating the use of lethal force has moved significantly beyond what was possible in the Cold War due to advances in computing and artificial intelligence.Footnote 4 Some scholars have even advocated for the United States to develop its own Dead Hand system.Footnote 5

We assess the impact of automation in the nuclear realm by focusing on nuclear coercion. That is, the threatened use of nuclear weapons to deter actors from changing the status quo or compelling them to alter it. Actually using nuclear weapons against another nuclear-armed state with a secure second-strike capability would be irrational since it comes with a very high risk of retaliation and complete destruction. On the other hand, threatening to use nuclear weapons for the purpose of coercing your adversary and taking active steps to increase the risks of nuclear use could be rational because it is a strategy that enables a state to potentially achieve their objectives without having to actually resort to nuclear war.Footnote 6

This research question intersects with two foundational debates in political science. First, are nuclear weapons useful for coercion at all, and, if so, what factors make the threatened use of nuclear weapons more credible? Although nuclear weapons do appear to be effective at deterring major nuclear attacks against a country’s homeland due to the likelihood of retaliation and mutually assured destruction (MAD), scholars vigorously disagree about their coercive utility beyond these fundamentally defensive scenarios. While some argue that nuclear weapons can be effective tools of coercion,Footnote 7 others contend that “despite their extraordinary power, nuclear weapons are uniquely poor instruments of compellence.”Footnote 8 The second debate our project overlaps with is whether emerging technologies—such as autonomous systems powered by artificial intelligence (AI)—aid or detract from strategic stability.Footnote 9 The effects of automation on the use of nuclear weapons for coercive purposes, however, remain mostly unexplored.

We contribute to these debates by theorizing that greater automation in the nuclear realm—while incredibly dangerous—can enhance the credibility of nuclear threats and better enable states to win games of nuclear brinkmanship. The logic of our argument is simple. Unless it is integrated into their programming, computers do not care that actually using nuclear weapons in a particular situation would be irrational or enormously costly. Consequently, by developing and activating an automated nuclear weapons system, leaders can more credibly threaten to use nuclear weapons compared to when it is a human that retains complete control over the process.Footnote 10 Like other strategies, such as public threats that put a leader’s reputation on the line and launch-on-warning policies, automated nuclear weapons systems enable leaders to more effectively “tie their hands,” increase nuclear risks, and throw the proverbial steering wheel out of the car in a game of chicken.Footnote 11

We test our expectations with preregistered experiments on an elite sample of UK Members of Parliament (MPs) and two representative samples of the UK public. The experimental scenario involves a future Russian invasion of Estonia. While nuclear powers like the United States, China, the United Kingdom, and France have made some level of public commitment to maintain human control over nuclear weapons, Russia has not made this kind of pledge.Footnote 12 All three studies yield at least some evidence—albeit somewhat inconsistent evidence—that Russian nuclear threats implemented via automation are more credible and/or effective than nuclear threats implemented via non-automated means. Troublingly, these dynamics suggest that nuclear-armed states may have incentives to automate elements of nuclear command and control to make their threats more credible.

This study makes several key contributions. First, the results move the debate forward about whether and under what conditions nuclear weapons have coercive utility. Our findings show that automated nuclear weapons launch systems can indeed provide states leverage in international crises. Second, while automated nuclear systems may have the theoretical potential to be stabilizing, our project suggests they can also be effectively used in highly destabilizing and malign ways, such as offensive and revisionist coercive efforts (for example, a Russian invasion of Estonia). Third, given the lack of real-world historical data on the use of automated systems in nuclear coercion, our experimental approach provides unique insights. Fourth, this paper speaks to broader debates about how technological advances will shape warfare, given that most military applications will occur outside the nuclear realm. If automated threats generate credibility in the nuclear realm, it may suggest something about conventional deterrence and coercion as well, which is a potential avenue for future research.

Although we find that automating nuclear use can potentially be useful for coercion, this does not at all suggest that states should adopt these systems given the ways automation could increase the risk of nuclear use and the significant ethical questions associated with reducing human control over weapons of mass destruction. However, states should prepare for the possibility that their adversaries might consider automating elements of nuclear command and control if they believe it will increase their coercive leverage.

Debates in the Literature

The Debate over Nuclear Weapons and Coercion

Sun Tzu famously said, “For to win one hundred victories in one hundred battles is not the acme of skill. To subdue the enemy without fighting is the acme of skill.” The logic of this argument is that actually fighting costs blood and treasure, whereas achieving your goals without using military force preserves lives, money, and other resources like land and weapons. One way to achieve foreign policy objectives without fighting is to utilize coercion, which involves the threat to do something—such as use military force—in the future. Coercion can either be utilized to (1) deter, which involves preventing a target from taking an action, or to (2) compel, which entails convincing a target to take an action. The latter type of coercion is generally accepted as more difficult to achieve because, in that case, it will be obvious a target “gave in” to the threat, which causes the kind of embarrassment leaders typically wish to avoid. Compellence is also more likely to fail because psychological biases tend to make those attempting to maintain the status quo more resolved than those trying to change it, and giving in to compellent threats can weaken a target’s material power relative to the status quo in ways that may make resisting future aggression more challenging.Footnote 13 Threats can also involve either punishment (for example, “if you attack my country, then I will hurt your country”) or denial (for example, “you can try to attack my country, but I will prevent you from successfully doing so”).

Although there are many factors that impact the efficacy of coercive efforts, a critical one is a state’s military capabilities. For example, the greater a state’s capacity to engage in deadly violence, the more pain they can realistically threaten. Nuclear weapons, then, would ostensibly confer significant coercive leverage given their immense destructive capabilities. As Pape said, “Nuclear weapons can almost always inflict more pain than any victim can withstand.”Footnote 14 However, for coercion to achieve its desired goal (that is, for it to be effective) the target must believe that if they violate your threat, then they will face the promised punishment or be directly denied from achieving their objective (that is, your threat must be credible). Or, at least, the target must believe there is an unacceptably high risk of the punishment being imposed or a denial effort working. The question of whether nuclear threats are credible has led to two fundamental debates among scholars that are germane to this project. First, are nuclear weapons useful at all for coercion, especially coercion that does not involve deterrence and self-defense? Second, if nuclear weapons can aid in coercion, then what factors make the threatened use of nuclear weapons more credible?

With respect to the first question, there are two schools of thought that can broadly be labeled as nuclear coercion skeptics and nuclear coercion believers. Skeptics question whether the threat of nuclear use by State A against State B is credible, except for direct self-defense against a potentially existential attack. When facing a nuclear-armed opponent with a secure second-strike capability, using nuclear weapons may simply be irrational because it has a high chance of leading to devastating nuclear retaliation.Footnote 15 In accordance with this logic, some studies find that nuclear-armed states are less likely to go to warFootnote 16 and crises that involve nuclear-armed states are more likely to end without violence.Footnote 17 The fact that the Cold War between the United States and Soviet Union stayed cold and never escalated into World War III is also frequently cited as evidence of the pacifying effects of nuclear weapons.Footnote 18

Even against non-nuclear states that cannot threaten nuclear retaliation, nuclear threats may also lack credibility because the political, economic, and social costs of carrying out the threat would be extremely high.Footnote 19 Some scholars argue there is a global nuclear taboo, which is “a de facto prohibition against the use of nuclear weapons … [that] involves expectations of awful consequences or sanctions to follow in the wake of a taboo violation.”Footnote 20 This logic may help explain why countries have not used nuclear weapons even when they possess an asymmetric nuclear edge (for example, the United States’ war in Vietnam). More systematically, using statistical analysis and case studies, Sechser and Fuhrmann find little evidence that nuclear weapons are useful for more than self-defense. The reason, they conclude, “is that it is exceedingly difficult to make coercive nuclear threats believable. Nuclear blackmail does not work because threats to launch nuclear attacks for offensive political purposes fundamentally lack credibility.”Footnote 21

On the other hand, nuclear coercion believers contend that nuclear threats can be made credible, even outside the context of deterrence and self-defense. One key argument that purportedly helps solve the problem of credibility is Schelling’s theory of nuclear brinkmanship, or the “threat that leaves something to chance.”Footnote 22 Although actually using nuclear weapons against a nuclear-armed state with a second-strike capability is illogical due to the dynamics of MAD, states may be able to take certain actions to increase the risk of nuclear use and thus convince adversaries that nuclear threats could end up being acted upon.

This paper directly contributes to this first debate by theorizing and empirically testing whether nuclear weapons can be useful for coercion in a case that involves clear offensive objectives rather than self-defense. It contributes to the second debate as well about the factors that make the threatened use of nuclear weapons more credible. One option is for states to delegate the authority to use nuclear weapons to lower-level military commanders (for example, Dead Hand). Doing so raises the risk that “rogue military officers could take matters into their own hands and release nuclear weapons.”Footnote 23 In other words, giving the authority to launch nuclear weapons over to an entity that is less likely to be dissuaded by the risks of MAD can make nuclear threats more credible.Footnote 24 This policy option is closely related to this project, which examines the impact of delegating nuclear launch authority to a machine rather than another human.

There are several other factors that have been posited to make the use of nuclear weapons more credible. These include nuclear superiority relative to an opponent,Footnote 25 putting nuclear forces on hair-trigger alert,Footnote 26 making public threats that engage audience costs,Footnote 27 or adopting the so-called “madman strategy.”Footnote 28

While all of these strategies can increase risks by leaving “something to chance,” at the end of the day a human being still has to press the nuclear button. As Pauly and McDermott said, “Barring a preexisting doomsday machine, leaders still must make a conscious choice to use nuclear weapons, even in response to an attack that is assumed to be so provocative as to demand one.”Footnote 29 Nevertheless, it is precisely the potential use of a doomsday machine, as in Dr. Strangelove or like the Soviet’s Dead Hand system, that we are interested in and turn to now.

The Debate over Automation and Strategic Stability

Given the unthinkable destructiveness that a nuclear war would bring, a key concern of scholars and policymakers is maintaining strategic stability. Strategic stability can be defined narrowly as the lack of incentives for any country to attempt a disarming nuclear first strike or, more broadly, as the lack of military conflict between nuclear-armed states.Footnote 30 One major debate is whether greater automation in the nuclear realm will enhance or undermine strategic stability. States can automate nuclear processes via hard-coded and rules-based computer systems, such as Dead Hand, or more complex and cutting-edge machine learning programs that make inferences from patterns in a training data set and then perform tasks without explicit instructions (namely, AI).Footnote 31 We derive two broad schools of thought from the existing literature—nuclear automation optimists and pessimists. Though very few scholars advocate automating nuclear use, there is a potential nuclear automation optimist argument for why it could bolster strategic stability.

One key argument automation optimists make is that new technologies—such as hypersonic weapons, stealthy nuclear-armed cruise missiles, and underwater nuclear-armed drones—substantially compress the time available to respond to a nuclear first strike, making such an attack more likely to succeed in crippling a country’s nuclear command, control, and communications systems (NC3) before they are able to retaliate or leading to poor and escalatory decision making, thus undermining strategic stability.Footnote 32 To avoid such a scenario, countries can adopt automated nuclear systems (like Dead Hand) to help ensure retaliation and enhance nuclear deterrence.

Other optimistic arguments include the claim AI can enhance the accuracy of nuclear early warning systems by more efficiently processing information.Footnote 33 However, this capability would be less valuable when a country’s adversary has only a small nuclear arsenal that presents less of a large data problem. AI-enabled systems may also be able to search for vulnerabilities in a country’s own NC3. Nevertheless, nearly all scholars—even relative optimists—argue there is substantial risk to removing humans from decisions about the use of nuclear weapons.Footnote 34

The argument automation pessimists make, by contrast, is that implementing automation into nuclear systems is highly dangerous and likely to undermine strategic stability. One key risk with these systems is simply that they will fail.Footnote 35 An oft-cited example is the “man who saved the world” on 26 September 1983, when a Soviet early warning system falsely indicated that an American nuclear strike was incoming. Colonel Stanislav Petrov, who was the key Soviet officer on duty, believed this was a false alarm due to computer error and decided not to report this warning up the chain of command. If he had reported it, then that could have led the Soviet political leadership to immediately order nuclear retaliation. There are other historical examples of nuclear early-warning systems reporting false positives during the Cold War, and automated systems have failed in other contexts. For example, Boeing’s 737 MAX Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) was responsible for several fatal commercial airline crashes in 2018 and 2019. Automation systems based on machine learning are particularly opaque in terms of how they make decisions, which could lead to errors that would be less likely in hard-coded, rules-based systems like Dead Hand. The problem is made worse by the lack of extensive real-world data on nuclear war that can be used to effectively train these systems (thankfully).Footnote 36 Furthermore, automated nuclear systems may reflect the biases of their programmers and of societies at-large, which can contribute to system failure.Footnote 37

Two other issues associated with automation compound the dangers of system failure. The first is automation bias, where humans put too much trust in computers and become less likely to question or critically analyze their conclusions and recommendations.Footnote 38 The risk is that if an automated nuclear system makes a mistake, then the next human in a similar situation as Petrov may decide to just trust the machine. A second concern is the high speeds with which computers operate, which might prevent humans from having the time to recognize and correct a mistake made by an automated nuclear system.Footnote 39 For example, in the 2010 “flash crash,” automated stock market trading systems caused the market to lose around one trillion dollars worth of value in a matter of minutes. Although the stock market was able to recover, the destruction caused by the use of even a single nuclear weapon would be impossible to fully ameliorate.

Finally, another principal concern is that automated nuclear systems could be hacked.Footnote 40 Malign state or nonstate actors could leverage this vulnerability to try and start a nuclear war between their enemies, or a state actor could attempt to prevent an adversary from having the capability to retaliate in response to a nuclear first strike attempt.

While nuclear automation pessimists have explored the many ways in which automation could undermine strategic stability, much less work has focused on how automation could be utilized for compellent and/or offensive efforts to acquire territory or achieve other revisionist foreign policy objectives. We fill this gap by developing a theory about how automated nuclear systems can be used to enable highly aggressive and revisionist foreign policies.

Theory: Tying Hands via Automation

Nuclear brinkmanship contests between two nuclear-armed states can be thought of as a game of chicken. In the classic example of a game of chicken, two cars are barreling toward each other and the first car to swerve loses. “Winning” requires one actor convincing the other that they will not swerve, even though a head-on collision would, of course, be disastrous. A similar situation exists in games of nuclear brinkmanship, as one actor must convince the other of the credibility of their nuclear threats even though using nuclear weapons against another nuclear-armed country has a high likelihood of leading to disaster. One way to do this is to throw the steering wheel out of the car, demonstrating your resolve and degrading or removing your ability to steer the car out of harm’s way.Footnote 41 As previously discussed, several strategies have been proposed that might have this kind of effect. For example, delegating launch authority to lower-level officers, making public threats, and putting weapons on hair-trigger alert. However, none of these strategies eliminates human choice, as someone must still actively decide to launch nuclear weapons barring mechanical failure.Footnote 42 Since doing so is arguably irrational, the credibility of such threats may still be uncertain.

By contrast, the development and deployment of automated nuclear weapons systems may remove human agency to an even greater degree than these other policies and thus increase threat credibility. Unless it is integrated into their programming, computers do not care that actually using nuclear weapons in a particular situation would be irrational or unimaginably costly. Therefore, automated nuclear systems may enable leaders to more literally “tie their hands.” As Reiter explained, “Perhaps the most extreme form of tying hands is giving a computer the ability to implement a commitment. This solves the credible commitment problem, because a computer is untroubled if an action is genocidal or suicidal.”Footnote 43 Or consider the following logic from Dr. Strangelove himself:

Mr. President, it is not only possible [for the doomsday machine to be triggered automatically and impossible to untrigger], it is essential. That is the whole idea of this machine, you know. Deterrence is the art of producing in the mind of the enemy the fear to attack. And so, because of the automated and irrevocable decision-making process which rules out human meddling, the doomsday machine is terrifying. It’s simple to understand. And completely credible, and convincing.

Of course, automated nuclear launch systems do not completely eliminate human choice. Humans would have to design such a system, activate it, and (potentially, depending on the programming) not override it if the conditions were met to launch a nuclear attack. Political leaders may be loath to take these actions given the risks of escalation and the loss of personal control it entails.Footnote 44 There are therefore many factors that likely impact the credibility of claims that an automated nuclear weapons system has been activated. This includes the stakes of the scenario, the technological capabilities of the country, and the perceived risk tolerance of the country’s leadership. Coercers could potentially increase the credibility of this claim by (1) providing some kind of demonstration or test of the automated system, (2) making public statements that engage audience costs, which prior work shows even operate in autocracies to some extent,Footnote 45 and (3) issuing private statements to target countries, which previous research also shows can enhance credibility.Footnote 46 Alternatively, they might purposefully maintain strategic ambiguity—much like Washington’s policy vis-à-vis Taiwan—to create some level of uncertainty while also lessening the reputational costs and escalatory risks of explicitly announcing the activation of an automated nuclear system. A necessary condition for our argument to operate is that a claim to have built and activated an automated nuclear weapons launch system is at least somewhat credible, meaning—at minimum—it is perceived as having a non-zero probability. Even if the probability is less than 100 percent, uncertainty about whether a country has actually activated such a system could increase credibility by heightening perceptions that a country has perhaps taken the risky step of reducing human control over nuclear weapons. Although how countries handle this uncertainty will likely vary, we expect the following preregistered hypothesis to hold on average.Footnote 47

H1 Nuclear threats implemented via automated launch systems will increase perceptions in target audiences that a country will use nuclear weapons if their threatened red line is violated compared to nuclear threats implemented via non-automated procedures.

For threats to achieve their desired goal (that is, for them to be effective), target states must believe they might actually face the stated punishment if they cross the threatening country’s red line. Consequently, threat credibility is a key mechanism explaining threat effectiveness. Given H1, we next hypothesize that nuclear threats implemented via automated systems will enhance threat effectiveness relative to threats implemented without automation. If an adversary believes a country is more likely to utilize nuclear weapons when they have an automated launch system, then they should be more likely to back down to avoid the tremendous pain such an attack would inflict. Leaders might also be better able to justify to their domestic constituents why they are backing down from previous promises if they can point to new information in the form of an automated nuclear threat.Footnote 48

H2 Nuclear threats implemented via automated launch systems will increase target audiences’ willingness to back down compared to nuclear threats implemented via non-automated procedures.

Given that these are probabilistic rather than deterministic arguments, we do not expect threats implemented via automated launch systems to always be effective. Many factors will impact the likelihood of success. For instance, the higher the stakes are for the target of coercion, the lower the probability in general of them giving in. Nuclear coercion—whether automated or non-automated—involving threats of denial rather than punishment may also be more likely to succeed given findings about airpower.Footnote 49 Additionally, per the aforementioned consensus among scholars, compellent threats should be less likely to be effective in general than deterrent ones. As Art and Greenhill conclude from a review of the literature, “successful nuclear compellence is not impossible, but it is difficult and dangerous to execute.”Footnote 50 However, while the success rate of compellent nuclear threats should be lower than deterrent ones whether implemented via automation or not, we do not anticipate compellence will be uniquely challenging in the case of automation. In both scenarios, the reputational and other challenges with successfully compelling targets to change their behavior should be present. We thus expect relative differences in credibility between automated and non-automated threats to persist for both compellence and deterrence.

Although we theorize automated nuclear weapons launch systems provide some advantages in coercive bargaining, we preregistered that they also entail drawbacks to the coercing state. Given that baseline public opposition to lethal autonomous weapons is highFootnote 51 —despite also being malleableFootnote 52 —respondents may view nuclear threats implemented via automated systems to be especially threatening.

H3 Nuclear threats implemented via automated launch systems will increase target audiences’ threat perceptions compared to nuclear threats implemented via non-automated procedures.

Heightened threat perceptions may then impact the kinds of policy preferences held by target audiences. In particular, it may incentivize balancing behavior—such as increasing military spending and maintaining a nuclear deterrent—to address the threat. However, these costs to the coercer would materialize only in the longer term, whereas the credibility benefits would accrue in the short term and thus be more immediately relevant for a time-critical crisis of the type we study.

H4 Nuclear threats implemented via automated launch systems will increase target audiences’ support for greater military spending compared to nuclear threats implemented via non-automated procedures.

H5 Nuclear threats implemented via automated launch systems will decrease target audiences’ support for nuclear disarmament compared to nuclear threats implemented via non-automated procedures.

Finally, we theorize that respondents will perceive a greater chance of a nuclear accident (that is, nuclear weapons being mistakenly used even when a country’s red line has not been violated) when automated launch systems are used. Despite the possibility of automation bias—which would suggest the opposite hypothesis—we expect that the relatively novel nature of this technology, recent examples of errors related to automated computer systems (for example, MCAS) and large-language models (for example, ChatGPT), and the dystopian presentation of nuclear automation in popular culture,Footnote 53 will reduce confidence in the ability of these systems to avoid accidents. Non-experimental surveys of eighty-five experts from around the world provide some initial evidence supporting this hypothesis, as a large majority believed emerging technologies like AI increase the risks of inadvertent escalation in the nuclear realm.Footnote 54 Another study finds US citizens have a relatively high baseline view that autonomous weapons are accident-prone.Footnote 55 Although a perceived increased risk of accidents could dissuade the coercer from adopting such a system in the first place,Footnote 56 it could also make the target more likely to back down due to a logical desire to avoid a devastating accident and/or because of psychological risk aversion.

H6 Nuclear threats implemented via automated launch systems will increase perceptions in target audiences that a nuclear accident will occur compared to nuclear threats implemented via non-automated procedures.

Data and Methods

Study 1

Experimental Design

To test our hypotheses, we designed a between-subjects experiment with two key experimental conditions—one where a non-automated nuclear threat is made and another where an automated nuclear threat is made.Footnote 57

The experimental scenario takes place in 2030 and involves a Russian invasion of Estonia. Russia is an appropriate country for this study given its large nuclear arsenal, history of making nuclear threats, and prior use of a semi-automated nuclear weapons system. A Russian invasion of Estonia in 2030 is also, at the very least, plausible. In 2023, the Estonian Foreign Intelligence Service assessed that Russia was unlikely to invade within the next year, but “in the mid-to-long term, Russia’s belligerence and foreign policy ambitions have significantly increased the security risks for Estonia.”Footnote 58 We control for several factors to ensure information equivalence across experimental conditions and thus avoid confounding.Footnote 59 First, we inform respondents that the Russia–Ukraine War formally concluded in 2025 and we hold constant the outcome of the conflict. Russia is also still led by Vladimir Putin and we control for Russia’s military capabilities relative to NATO countries. In particular, we remind respondents that Russia “still maintains a large stockpile of high-yield (strategic) and lower-yield (tactical) nuclear weapons.”

Respondents are then randomly assigned to one of two conditions. The first is the non-automated nuclear threat treatment, where Putin makes an explicit nuclear threat, but human control over the use of nuclear weapons is maintained. The second is the automated nuclear threat treatment. Here, Putin also makes an explicit nuclear threat, but in this scenario the threat is implemented via automation, meaning human control is delegated to a machine:

Vladimir Putin has also publicly made a threat that Russia will immediately launch at least one nuclear weapon against NATO military or civilian targets in the UK and other European countries at the first sign NATO uses missiles or strike aircraft against its forces in Estonia.

-

Non-Automated Treatment: Ultimately, Putin would make the final decision whether or not to use nuclear weapons. UK and US intelligence agencies confirm Putin has indeed issued this order to the Russian military.

-

Automated Treatment: Moreover, Putin also publicly announced that this response would be completely automated, meaning Russia’s artificial intelligence systems would automatically launch a nuclear weapon if Russia’s early-warning systems detect a NATO missile launch or deployment of strike aircraft. Ultimately, a computer—rather than Putin—would make the final decision whether or not to use nuclear weapons. UK and US intelligence agencies confirm Putin has indeed issued this order to the Russian military and the automated nuclear weapons launch system has been turned on.

In both treatments we inform respondents that intelligence agencies confirm that Putin has taken concrete steps to operationalize his threat. Uncertainty about whether or not an automated system has been turned on could certainly reduce the effectiveness of nuclear threats.Footnote 60 Future research should analyze the precise role uncertainty plays, but for our purposes here, we want to test the relative credibility and effectiveness of non-automated and automated nuclear threats that are both presented in relatively strong forms.

We contend these treatments—where Russia makes nuclear threats—are, at the very least, plausible. The Biden administration was so concerned about possible Russian nuclear use against Ukraine or NATO targets that it created task forces and conducted simulations to plan for what the US response should be. At one point, US intelligence agencies estimated that the likelihood of Russian nuclear use was as high as 50 percent if their lines in southern Ukraine collapsed.Footnote 61 Furthermore, according to reporting in the New York Times, “One simulation … involved a demand from Moscow that the West halt all military support for the Ukrainians: no more tanks, no more missiles, no more ammunition.”Footnote 62 This situation is quite similar to the one outlined in the experiment and thus indicates the survey scenario is realistic.

All in all, this scenario involves a clearly aggressive and revisionist action by Russia, and the kind of attempted nuclear blackmail that nuclear coercion skeptics believe is unlikely to succeed.Footnote 63 For example, Russia’s action in the scenario resembles Pakistan’s strategy in the 1999 Kargil War, in which they deployed troops into Indian-controlled Kashmir and hoped their nuclear arsenal would coerce India into accepting the new status quo. Nuclear coercion skeptics point to the Kargil War—the only direct conflict between nuclear-armed powers in history that meets the Correlates of War threshold for war—as a failed example of nuclear blackmail.Footnote 64 Our experimental study provides a more controlled setting to assess the efficacy of nuclear brinkmanship.

Respondents are then asked a series of dependent variable questions. To assess threat credibility, we ask survey subjects to estimate the percentage chance Russia will use at least one nuclear weapon if NATO countries use missiles or strike aircraft. To measure threat effectiveness, we ask to what extent respondents would support or oppose the United Kingdom using missiles or strike aircraft in conjunction with other NATO forces; that is, violating Putin’s red line. We also ask a series of other questions regarding threat perceptions toward Russia, support for increasing military spending or abolishing the United Kingdom’s nuclear arsenal, and perceptions that Russia will accidentally use nuclear weapons even if NATO countries do not cross Putin’s red line.

There are some aspects of our design that make this a harder test for finding evidence that automated nuclear threats increase the efficacy of coercive efforts. Since Estonia is a member of NATO and thus protected under Article 5, UK citizens and policymakers have relatively strong incentives to support coming to their aid compared to countries that have not been given defense guarantees. The United Kingdom also has nuclear weapons of its own that may cause respondents to believe Russia will be deterred from launching a nuclear attack against it. Moreover, Putin and other Russian officials have made nuclear threats in the context of the Russia–Ukraine War that have not been carried out, which may make respondents question the credibility of future threats. On the other hand, this may be an easier test because Russia has deployed a semi-automated nuclear launch system in the past and made implicit and explicit nuclear threats that may have played a role in preventing more direct or larger-scale NATO intervention in Ukraine. Russia has also demonstrated a high degree of resolve by absorbing enormous costs in the Russia–Ukraine War, which is arguably a war of choice rather than necessity. On balance, while we leave it to readers to decide whether this is closer to an easier or a harder test, we believe it is a fair test of our hypotheses—neither too hard nor too easy—given these countervailing logics.

Sample

We recruited 800 UK citizens via the survey platform Prolific in September 2023. Prolific uses quota sampling to match Census benchmarks on sex, age, and ethnicity. Prior research has also demonstrated that data from Prolific is high quality and may perform better than many other survey providers, such as Qualtrics, Dynata, CloudResearch, and MTurk.Footnote 65

We chose to study the United Kingdom because it is a key member of NATO, would likely play a significant role responding to a Russian invasion of Estonia (especially since it is the leading state in the NATO Enhanced Forward Presence force deployed to Estonia), and is a nuclear power itself, along with being one of the world’s largest economies and a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council.

Studying public opinion on this topic is valuable because previous studies—including those conducted directly on elites—establish that policymakers respond to and are constrained by public opinion.Footnote 66 For example, Tomz, Weeks, and Yarhi-Milo conducted experiments on actual members of the Israeli Knesset and found they were more willing to use military force when the public was in favor, as they feared the political consequences of defying public opinion.Footnote 67 In the nuclear realm, scholars have also provided empirical evidence that domestic and international public opinion impacts the views of policymakers,Footnote 68 which is a key basis for the voluminous experimental literature evaluating the nuclear taboo via survey experiments on the public.Footnote 69 Given that nuclear crises are highly salient, they may even be more likely to capture public attention than other types of foreign policy crises. Thus, public willingness to capitulate in the face of threats will reduce the domestic constraints leaders face to backing down. Public opposition to capitulation, on the other hand, will stiffen the spine of leaders and make nuclear threats less likely to succeed.

Study 2

To test the robustness of our results from Study 1, we also designed and fielded a second experiment on about 1,060 members of the UK public in partnership with Prolific in February 2024. The only substantive difference between Studies 1 and 2 relates to the wording of the two treatment conditions. In Study 1, some of the wording, especially in the automated nuclear threat treatment, could arguably increase the likelihood of finding effects. For example, in Study 1 the automated nuclear threat treatment includes the following language: “Ultimately, a computer—rather than Putin—would make the final decision whether or not to use nuclear weapons.” While a computer could indeed have the final say on whether to use nuclear weapons if that was how the system was constructed, this is strong language because some kind of override may very well be programmed into automated launch systems. Consequently, in Study 2 we remove this language from the automated threat treatment. We also remove the corresponding language in the non-automated nuclear threat treatment that “ultimately, Putin would make the final decision whether or not to use nuclear weapons.” On balance, we expect these changes could reduce the perceived disparities between the automated and non-automated treatments and make Study 2 a harder test of our hypotheses. However, one advantage of Study 1 was that it ensured a clearer experimental manipulation since there was a starker contrast between the automated treatment (decision being made by a machine) and the non-automated treatment (decision being made by a human).

Study 3

In a meta-analysis of 162 paired experiments on members of the public and elites, Kertzer finds that elites generally respond to treatments in the same ways as members of the public.Footnote 70 This indicates that results among the general public are likely to be externally valid to policymakers. However, studies have specifically found relatively large elite-public gaps in baseline support for nuclear weapons use.Footnote 71 Although this does not necessarily mean there will be similar gaps in experimental treatment effects due to factors like floor effects, we test the external validity of our public results in a third experiment on an elite sample of 117 UK MPs in October 2024 via a partnership with YouGov. This sample has also been utilized by prior work,Footnote 72 and it tracks well with the actual UK House of Commons in terms of factors like party identification.

We utilize the treatment language from Study 2 in Study 3. We also make another key change to the design. Given the small sample size, we present respondents with both treatment conditions. This alters the experiment from a between-subjects to a fully within-subjects design. Given the small sample size of most elite experiments, this design choice is logical because it helps maximize statistical power.Footnote 73 Extant research also shows that within-subjects designs are valid tools for causal inference, despite theoretical concerns about demand effects and consistency pressures.Footnote 74 To mitigate any possible order effects, we randomize the order of the treatments.

Results

Study 1

According to our theoretical expectations, we find strong evidence that threat credibility is higher in the automated treatment than it is in the non-automated treatment. Figure 1 plots the densities for these two treatments and shows that the perceived probability that Russia will use nuclear weapons is over 12.3 percentage points greater in the automated than the non-automated nuclear threat treatment (p < .001). While undoubtedly dangerous in terms of escalation risks, this accords with our preregistered hypothesis that automated nuclear threats can allow leaders to more credibly tie their hands in crisis scenarios, and illustrates the temptation some leaders may face to adopt these kinds of systems in similar contexts to our experiment.

Figure 1. Automated nuclear threats enhance credibility

Note: *p < .10; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

Similarly, we find strong evidence that nuclear threats implemented via automated launch systems are more effective than those implemented via non-automated means (p < .05 using a seven-point scale). Figure 2 illustrates this visually. Most notably, 20 percent of respondents “strongly opposed” violating Putin’s red line in the automated nuclear threat treatment compared to just 10.9 percent in the non-automated treatment. Interestingly, absolute support for violating Putin’s red line is still relatively high (42–47 percent) despite the risks involved. This is likely due to a combination of the United Kingdom’s Article 5 commitment to Estonia and a perception among some respondents that Russia is probably bluffing. Indeed, we show in the appendix that perceived threat credibility significantly mediates support for violating Putin’s red line.

Figure 2. Automated nuclear threats enhance effectiveness

Surprisingly, and in contrast to our preregistered expectations, automated nuclear threats are not associated with significantly greater threat perception, support for increasing military spending, or opposition to nuclear disarmament.Footnote 75 Floor and ceiling effects can help explain this null finding. For example, threat perceptions were already high and support for nuclear disarmament was already low in an absolute sense whenever any kind of nuclear threat was made, meaning there was little room for the nature of that threat (automated versus non-automated) to matter. This null finding indicates that the costs to the coercer of threatening nuclear use via an automated system are somewhat lower than expected, at least when the counterfactual is a nuclear threat implemented via non-automated means.

However, as Figure 3 shows, automated nuclear threats do increase perceptions—by over thirteen percentage points—that Russia will mistakenly use nuclear weapons even if NATO does not violate Putin’s red line. Automated nuclear systems may enable leaders to throw the steering wheel out of the car in a game of chicken and enhance the effectiveness of nuclear brinkmanship, but the public is relatively less trusting that the technology will work as intended compared to when humans remain fully “in the loop.” This belief may reduce public support for the adoption of automated nuclear launch systems due to the fear of losing control. Of course, whether this perception matches reality, relative to the potential for human error, is open to debate, and the answer may change as the technology develops. Moreover, from the perspective of the coercer, an increased perceived risk of accidents may actually be a positive in one key respect. Since the goal of nuclear brinkmanship is to increase the target’s perception that nuclear escalation is possible, higher fears that automated nuclear weapons systems will lead to accidents might encourage the target to back down.

Figure 3. Automated threats increase the perceived risk of accidents

Note: *p < .10; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

Robustness and Study 2

We take several steps in the appendix to demonstrate the robustness of our core results. First, we illustrate that they hold in a regression context when controlling for factors like hawkishness, political identification, education, and gender. Second, we probe potential interaction effects and do not find consistent effects for factors like hawkishness, support for NATO or military aid to Ukraine, or self-assessed knowledge about international relations or artificial intelligence.Footnote 76 Third, we show that almost all of our core results hold in Study 2. The one exception is that the difference in threat effectiveness between the automated and non-automated threat treatment is estimated less precisely and is not statistically significant, though it is in the hypothesized direction. Overall, there is robust evidence among our public samples that automated nuclear threats enhance threat credibility more than non-automated threats.

Study 3

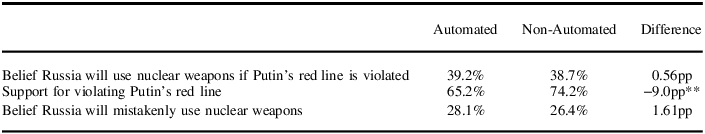

There are mixed results in our UK MP study.Footnote 77 Strikingly, we find significant evidence among our UK MP sample that automated nuclear threats are more effective than non-automated threats in the context of an international crisis. Specifically, as Table 1 displays, UK MPs are about nine percentage points (p ≈ .02) less likely to support violating Putin’s red line when he makes an automated nuclear threat compared to a non-automated nuclear threat.

Although directly comparing our elite study to our public studies is challenging given the differences in experimental design, it is interesting that in contrast to both Studies 1 and 2, we do not find significant evidence in our MP study that automated nuclear threats are more credible than non-automated nuclear threats. Belief that Russia will use nuclear weapons if their red line is violated is about 39 percent in both cases (though, in an absolute sense, that number is still quite high). The difference between our public and elite samples may be due to elites having a better understanding and belief in the dynamics of nuclear deterrence, though, on the other hand, the average UK MP is far from a nuclear expert.Footnote 78 Given that policymakers have a more direct influence over a country’s foreign policy than the public, the null result for threat credibility suggests the incentives to automate nuclear weapons launch systems are somewhat limited.

Table 1. Findings among United Kingdom Members of Parliament

Note: pp = percentage points.

What explains the difference between the threat effectiveness and credibility results, especially since threat effectiveness is arguably the more significant measure? We suggest two potential explanations. The first relates to uncertainty. Even if policymakers’ best point estimate guess about the probability of nuclear use was roughly the same for non-automated and automated nuclear threats, they may have been less confident and more uncertain about their estimates for the latter given the relative novelty of the technology and the inability to bargain with a computer in the same way one can bargain and reason with a human. Greater uncertainty about the risk of nuclear escalation may then have convinced some MPs to support backing down to avoid a devastating outcome. This explanation relates to the philosophical concept of “Pascal’s Wager,” which holds that if presented with significant uncertainty about a high-stakes outcome (for example, nuclear war), it is logical to take the path that reduces the probability of the worst outcome (for example, nuclear Armageddon), even if that outcome is not likely. The French thinker Blaise Pascal applied this logic to belief in God: Even if God might not exist, it is better to hedge your bets and believe to avoid eternal damnation. It is also relevant here in that automated systems might increase uncertainty and thus make backing down, which involves a finite cost, more attractive relative to risking nuclear conflict, which involves potentially infinite costs. A second potential explanation is that perhaps UK MPs felt it would be easier to justify to the UK public why they were backing down if they could point to the unprecedented use of an automated nuclear launch system rather than a more foreseeable nuclear threat implemented via non-automated means.Footnote 79

Another divergence from Studies 1 and 2 is that we find no significant evidence that UK MPs believe that nuclear accidents are more likely when threats are implemented via automation than without. This may reflect a greater belief among policymakers than the public in the testing and evaluation systems that a country would use in the real world prior to deploying such a system to prove it would work as intended. It also means leaders may be marginally less hesitant to adopt these kinds of systems than some believe.Footnote 80

Although the results related to credibility and effectiveness for automated versus non-automated nuclear threats are somewhat inconsistent between the three studies, all yield at least some evidence that states may gain coercion benefits from developing and deploying automated systems.

Conclusion

The question of how to make nuclear threats more credible—or, indeed, whether nuclear threats can ever be credible against nuclear-armed states outside the context of deterring an attack against one’s homeland—has puzzled scholars and policymakers alike. Our study makes a key contribution to this debate. There are ways to make nuclear threats more credible, even when they are in the service of offensive and revisionist goals. We find concerning evidence—even among policymakers—that automated nuclear weapons launch systems in particular may enhance the credibility and/or effectiveness of nuclear threats in the context of crises. Doing so validates fears about the integration of automation—perhaps powered by AI—into NC3. It may also incentivize countries to adopt these kinds of systems, just as the Soviets did with the Dead Hand system.

Our project also raises a number of promising avenues for future research. Since our argument and empirics are focused on crisis scenarios, future work should assess their external validity to non-crisis situations. From a theoretical perspective, threats implemented via automated nuclear launch systems may still enhance credibility and effectiveness for longer-term, more general deterrent relationships. For example, they could make threats to launch a nuclear attack in response to a non-nuclear kinetic attack or a major cyber attack more credible, despite the fact that some scholars reasonably argue such threats would normally be irrational to carry out and thus lack credibility.Footnote 81 For countries without secure second-strike capabilities, some leaders might also think that automated nuclear systems could, theoretically, help deter nuclear attacks by reducing the chances a first strike attempt could successfully decapitate a country’s leadership and cripple their communications networks, preventing a retaliatory order from being given.Footnote 82

Subsequent research can assess related questions while also evaluating the credibility of the claim that a state has actually activated an automated nuclear weapons launch system.Footnote 83 While direct intelligence about the matter is likely to be highly germane, other factors—like the stakes of the crisis, the perceived risk tolerance of the leader, and the public or private statements made by the coercing country—may also play a significant role. For instance, if the stakes are low, then it may be less credible that a country would assume the escalation and reputation risks associated with turning on such a system, especially for an offensive effort.

Technological developments from artillery and aircraft to submarines and smart bombs have, historically, changed the character of warfare and international politics. AI and other computer-related advancements have a similar potential. This paper unpacks how a key emerging technology might be integrated with a powerful existing technology—nuclear weapons—and used for malign purposes. We find evidence that the danger is real and should be taken seriously.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this research note may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/9DKDEK>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this research note, is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818325101215>.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sanghyun Han, Jenna Jordan, David Logan, Scott Sagan, participants of the MIT Security Studies Working Group and Seminar, the Georgia Tech STAIR Workshop, the Carnegie Mellon Political Science Research Workshop, and the 2024 International Studies Association Annual Conference for helpful comments and advice. We are also deeply grateful to Graham Elder, Isabel Leong, and Stotra Pandya for valuable research assistance.

Funding

This research note was made possible, in part, by funding from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the Minerva Research Initiative under grant #FA9550-18-1-0194.