Impact Statement

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, making accurate monitoring of its sources essential for effective climate action. This study presents a framework that integrates drone-based measurements with artificial intelligence to improve the detection and quantification of methane emissions. By combining Bayesian inference with atmospheric dispersion modeling and drone-based atmospheric data, the system estimates source locations and emission rates. Reinforcement learning enables the drone to plan adaptive flight paths that maximize information gain in unfamiliar environments. This framework supports the development of intelligent, efficient tools for environmental monitoring, with applications in climate science, emissions reporting, and regulatory compliance.

1. Introduction

Methane (CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

) is an important greenhouse gas emitted by a range of anthropogenic activities, including fossil fuel extraction, agriculture, and waste management, as well as natural sources such as inland waters, wild animals, and thawing permafrost (IPCC, Reference Lee and Romero2023). Accurate quantification of CH

$ {}_4 $

) is an important greenhouse gas emitted by a range of anthropogenic activities, including fossil fuel extraction, agriculture, and waste management, as well as natural sources such as inland waters, wild animals, and thawing permafrost (IPCC, Reference Lee and Romero2023). Accurate quantification of CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

emissions are essential for climate change mitigation; yet, current national and global inventories remain highly uncertain (Saunois et al., Reference Saunois, Stavert, Poulter, Bousquet, Canadell, Jackson, Raymond, Dlugokencky, Houweling, Patra, Ciais, Arora, Bastviken, Bergamaschi, Blake, Brailsford, Bruhwiler, Carlson, Carrol, Castaldi, Chandra, Crevoisier, Crill, Covey, Curry, Etiope, Frankenberg, Gedney, Hegglin, Höglund-Isaksson, Hugelius, Ishizawa, Ito, Janssens-Maenhout, Jensen, Joos, Kleinen, Krummel, Langenfelds, Laruelle, Liu, Machida, Maksyutov, McDonald, McNorton, Miller, Melton, Morino, Müller, Murguia-Flores, Naik, Niwa, Noce, O’Doherty, Parker, Peng, Peng, Peters, Prigent, Prinn, Ramonet, Regnier, Riley, Rosentreter, Segers, Simpson, Shi, Smith, Steele, Thornton, Tian, Tohjima, Tubiello, Tsuruta, Viovy, Voulgarakis, Weber, Van Weele, Van Der Werf, Weiss, Worthy, Wunch, Yin, Yoshida, Zhang, Zhang, Zhao, Zheng, Zhu, Zhu and Zhuang2020). As identified by Saunois et al. (Reference Saunois, Martinez, Poulter, Zhang, Raymond, Regnier, Canadell, Jackson, Patra, Bousquet, Ciais, Dlugokencky, Lan, Allen, Bastviken, Beerling, Belikov, Blake, Castaldi, Crippa, Deemer, Dennison, Etiope, Gedney, Höglund-Isaksson, Holgerson, Hopcroft, Hugelius, Ito, Jain, Janardanan, Johnson, Kleinen, Krummel, Lauerwald, Li, Liu, McDonald, Melton, Mühle, Müller, Murguia-Flores, Niwa, Noce, Pan, Parker, Peng, Ramonet, Riley, Rocher-Ros, Rosentreter, Sasakawa, Segers, Smith, Stanley, Thanwerdas, Tian, Tsuruta, Tubiello, Weber, Van Der Werf, Worthy, Xi, Yoshida, Zhang, Zheng, Zhu, Zhu and Zhuang2024), increasing the density of CH

$ {}_4 $

emissions are essential for climate change mitigation; yet, current national and global inventories remain highly uncertain (Saunois et al., Reference Saunois, Stavert, Poulter, Bousquet, Canadell, Jackson, Raymond, Dlugokencky, Houweling, Patra, Ciais, Arora, Bastviken, Bergamaschi, Blake, Brailsford, Bruhwiler, Carlson, Carrol, Castaldi, Chandra, Crevoisier, Crill, Covey, Curry, Etiope, Frankenberg, Gedney, Hegglin, Höglund-Isaksson, Hugelius, Ishizawa, Ito, Janssens-Maenhout, Jensen, Joos, Kleinen, Krummel, Langenfelds, Laruelle, Liu, Machida, Maksyutov, McDonald, McNorton, Miller, Melton, Morino, Müller, Murguia-Flores, Naik, Niwa, Noce, O’Doherty, Parker, Peng, Peng, Peters, Prigent, Prinn, Ramonet, Regnier, Riley, Rosentreter, Segers, Simpson, Shi, Smith, Steele, Thornton, Tian, Tohjima, Tubiello, Tsuruta, Viovy, Voulgarakis, Weber, Van Weele, Van Der Werf, Weiss, Worthy, Wunch, Yin, Yoshida, Zhang, Zhang, Zhao, Zheng, Zhu, Zhu and Zhuang2020). As identified by Saunois et al. (Reference Saunois, Martinez, Poulter, Zhang, Raymond, Regnier, Canadell, Jackson, Patra, Bousquet, Ciais, Dlugokencky, Lan, Allen, Bastviken, Beerling, Belikov, Blake, Castaldi, Crippa, Deemer, Dennison, Etiope, Gedney, Höglund-Isaksson, Holgerson, Hopcroft, Hugelius, Ito, Jain, Janardanan, Johnson, Kleinen, Krummel, Lauerwald, Li, Liu, McDonald, Melton, Mühle, Müller, Murguia-Flores, Niwa, Noce, Pan, Parker, Peng, Ramonet, Riley, Rocher-Ros, Rosentreter, Sasakawa, Segers, Smith, Stanley, Thanwerdas, Tian, Tsuruta, Tubiello, Weber, Van Der Werf, Worthy, Xi, Yoshida, Zhang, Zheng, Zhu, Zhu and Zhuang2024), increasing the density of CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

observations at local to regional scales are among the top five priorities for reducing uncertainty in the global CH

$ {}_4 $

observations at local to regional scales are among the top five priorities for reducing uncertainty in the global CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

budget.

$ {}_4 $

budget.

To address this challenge, we investigate the use of drones to collect local CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

measurements, enabling the estimation of point-source emissions. Several airborne techniques have been developed for quantifying CH

$ {}_4 $

measurements, enabling the estimation of point-source emissions. Several airborne techniques have been developed for quantifying CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

emission rates. The tracer flux ratio method involves co-releasing a tracer gas with a known flow rate and comparing its downwind dispersion to that of CH

$ {}_4 $

emission rates. The tracer flux ratio method involves co-releasing a tracer gas with a known flow rate and comparing its downwind dispersion to that of CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

. The mass balance method integrates CH

$ {}_4 $

. The mass balance method integrates CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

concentrations and wind data across a defined control volume to calculate the net flux. Both methods, which are compared in Lunt et al. (Reference Lunt, Harris, Hacker, Joynes, Robertson, Thompson and France2025) as well as Scheutz et al. (Reference Scheutz, Knudsen, Vechi and Knudsen2025), require prior knowledge of the source location. Inverse modeling techniques can infer multiple uncertain source parameters by fitting an atmospheric dispersion model to measured atmospheric data. We use a Bayesian inverse modeling approach, which offers a probabilistic framework for jointly estimating both the emission rate and the source location, while explicitly accounting for measurement uncertainty and model error (e.g., Hutchinson et al., Reference Hutchinson, Liu and Chen2019b; Park et al., Reference Park, An, Seo and Oh2021; van Hove et al., Reference van Hove, Aalstad, Lind, Arndt, Odongo, Ceriani, Fava, Hulth and Pirk2025).

$ {}_4 $

concentrations and wind data across a defined control volume to calculate the net flux. Both methods, which are compared in Lunt et al. (Reference Lunt, Harris, Hacker, Joynes, Robertson, Thompson and France2025) as well as Scheutz et al. (Reference Scheutz, Knudsen, Vechi and Knudsen2025), require prior knowledge of the source location. Inverse modeling techniques can infer multiple uncertain source parameters by fitting an atmospheric dispersion model to measured atmospheric data. We use a Bayesian inverse modeling approach, which offers a probabilistic framework for jointly estimating both the emission rate and the source location, while explicitly accounting for measurement uncertainty and model error (e.g., Hutchinson et al., Reference Hutchinson, Liu and Chen2019b; Park et al., Reference Park, An, Seo and Oh2021; van Hove et al., Reference van Hove, Aalstad, Lind, Arndt, Odongo, Ceriani, Fava, Hulth and Pirk2025).

Drone-based data collection offers spatial flexibility but is resource-intensive. Acquiring informative measurements is particularly difficult in environments with uncertain source locations and dynamic atmospheric conditions (Francis et al., Reference Francis, Li, Griffiths and Sienz2022). These constraints underscore the need for intelligent sampling strategies that maximize the informational value of each flight. In this study, we examine the optimization of drone flight paths in unfamiliar environments to improve the estimation of both emission rates and source locations from single-point CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

sources.

$ {}_4 $

sources.

We compare three path-planning strategies for drone-based CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

monitoring: (i) a preplanned lawnmower pattern, (ii) an adaptive short-sighted (myopic) policy that selects actions based on immediate information gain, and (iii) an adaptive long-term (non-myopic) policy trained using deep reinforcement learning. While similar strategies have been explored in previous work (e.g., Loisy and Eloy, Reference Loisy and Eloy2022; Park et al., Reference Park, Ladosz and Oh2022; Loisy and Heinonen, Reference Loisy and Heinonen2023; van Hove et al., Reference van Hove, Aalstad and Pirk2023; van Hove et al., Reference van Hove, Aalstad, Pirk, Lutchyn, Ramírez Rivera and Ricaud2024), prior studies often rely on synthetic data generated from simplified models, such as discretized observation spaces or additive white Gaussian noise assumptions, that may not adequately capture the complexity and variability of real-world atmospheric conditions.

$ {}_4 $

monitoring: (i) a preplanned lawnmower pattern, (ii) an adaptive short-sighted (myopic) policy that selects actions based on immediate information gain, and (iii) an adaptive long-term (non-myopic) policy trained using deep reinforcement learning. While similar strategies have been explored in previous work (e.g., Loisy and Eloy, Reference Loisy and Eloy2022; Park et al., Reference Park, Ladosz and Oh2022; Loisy and Heinonen, Reference Loisy and Heinonen2023; van Hove et al., Reference van Hove, Aalstad and Pirk2023; van Hove et al., Reference van Hove, Aalstad, Pirk, Lutchyn, Ramírez Rivera and Ricaud2024), prior studies often rely on synthetic data generated from simplified models, such as discretized observation spaces or additive white Gaussian noise assumptions, that may not adequately capture the complexity and variability of real-world atmospheric conditions.

In contrast, we generate synthetic observations using an observation model calibrated to replicate CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

dispersion from a point source under Arctic conditions. This calibrated model is referred to as the nature run, following the concept used in observing system simulation experiments (OSSEs) (Masutani et al., Reference Masutani, Schlatter, Errico, Stoffelen, Andersson, Lahoz, Woollen, Emmitt, Riishøjgaard, Lahoz, Khattatov and Menard2010). In OSSEs, a nature run represents a high-resolution atmospheric simulation that acts as a surrogate for the “true” atmospheric state, enabling the generation of realistic synthetic observations for testing hypothetical observing systems. Our approach adopts this principle but grounds it in field data. Specifically, we tune the observation model using measurements from a drone campaign in Svalbard. Physical parameters are derived directly from field observations, while observation error characteristics are estimated through statistical calibration methods, including maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) and Bayesian model comparison. The resulting nature run provides a controlled, data-driven environment from which synthetic observations are generated to evaluate the different path-planning strategies under varied conditions, such as source location, emission strength, and wind conditions.

$ {}_4 $

dispersion from a point source under Arctic conditions. This calibrated model is referred to as the nature run, following the concept used in observing system simulation experiments (OSSEs) (Masutani et al., Reference Masutani, Schlatter, Errico, Stoffelen, Andersson, Lahoz, Woollen, Emmitt, Riishøjgaard, Lahoz, Khattatov and Menard2010). In OSSEs, a nature run represents a high-resolution atmospheric simulation that acts as a surrogate for the “true” atmospheric state, enabling the generation of realistic synthetic observations for testing hypothetical observing systems. Our approach adopts this principle but grounds it in field data. Specifically, we tune the observation model using measurements from a drone campaign in Svalbard. Physical parameters are derived directly from field observations, while observation error characteristics are estimated through statistical calibration methods, including maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) and Bayesian model comparison. The resulting nature run provides a controlled, data-driven environment from which synthetic observations are generated to evaluate the different path-planning strategies under varied conditions, such as source location, emission strength, and wind conditions.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to use a data-driven nature run to train and assess adaptive drone sampling strategies for joint estimation of source location and emission rate. Deep reinforcement learning has rarely been applied to this problem (e.g., Park et al., Reference Park, Ladosz and Oh2022; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Jang, Park and Oh2025), and its use with information gain as a reward signal remains especially uncommon—making our approach both novel and technically challenging.

We further explore the role of drone collaboration by comparing single-agent systems (i.e., one drone) with multi-agent systems (i.e., multiple drones). Specifically, we assess whether centralized, coordinated exploration improves the accuracy of source term estimates compared to independent operation. Our objectives are threefold: (i) to generate more realistic synthetic data informed by real-world observations, (ii) to evaluate whether adaptive sampling improves estimation accuracy over preplanned baseline strategies, and (iii) to explore whether collaboration between two drones yields additional benefits over independent operation. Ultimately, our goal is to support the development of more reliable emission inventories and inform targeted mitigation strategies at local to regional scales by improving the accuracy and efficiency of CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

source term estimation methods.

$ {}_4 $

source term estimation methods.

2. Methods

We present a framework for estimating the location and emission rate of a single CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

source using drone-based observations. Our approach consists of two components: (i) source term estimation (STE) (Hutchinson et al., Reference Hutchinson, Oh and Chen2017), which applies Bayesian inverse modeling to infer the source parameters from CH

$ {}_4 $

source using drone-based observations. Our approach consists of two components: (i) source term estimation (STE) (Hutchinson et al., Reference Hutchinson, Oh and Chen2017), which applies Bayesian inverse modeling to infer the source parameters from CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

concentration and wind data; and (ii) adaptive informative path planning (AIPP) (Popović et al., Reference Popović, Ott, Rückin and Kochenderfer2024), which optimizes drone trajectories to collect the most informative observations in a limited flight time. A schematic overview of the framework and its methodologies is provided in Figure 1.

$ {}_4 $

concentration and wind data; and (ii) adaptive informative path planning (AIPP) (Popović et al., Reference Popović, Ott, Rückin and Kochenderfer2024), which optimizes drone trajectories to collect the most informative observations in a limited flight time. A schematic overview of the framework and its methodologies is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic overview of the developed framework, consisting of two main components: source term estimation (top box, Section 2.1) and drone path planning strategies (bottom box, Section 2.2). Source estimation uses Bayesian inverse modeling in the Box–Cox transformed observation space, where “B-C” denotes the Box–Cox transformation. Bayesian updating is sequential in the synthetic experiments, with each posterior becoming the prior for the next step. Path planning is guided by the agent (i.e., drone) policy: preplanned (deterministic), myopic (greedy one-step lookahead), or non-myopic (greedy via a trained state-value function). Dashed lines indicate components used only during reinforcement learning training, where a neural network approximates state-action values using epsilon-greedy exploration.

2.1. Source term estimation

Estimating the location and emission rate of a CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

source from drone observations is formulated as an inverse modeling problem. The source parameters of interest cannot be observed directly, but must be inferred from indirect observations of CH

$ {}_4 $

source from drone observations is formulated as an inverse modeling problem. The source parameters of interest cannot be observed directly, but must be inferred from indirect observations of CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

concentration and wind.

$ {}_4 $

concentration and wind.

This relationship is expressed by the observation model:

where

![]() $ \boldsymbol{d} $

denotes the observed data,

$ \boldsymbol{d} $

denotes the observed data,

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

represents the uncertain source parameters to be estimated, and

$ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

represents the uncertain source parameters to be estimated, and

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\zeta} $

includes parameters assumed to be known. The forward model

$ \boldsymbol{\zeta} $

includes parameters assumed to be known. The forward model

![]() $ \mathcal{F}\left(\cdot \right) $

maps these inputs to predicted observations, while the residual term

$ \mathcal{F}\left(\cdot \right) $

maps these inputs to predicted observations, while the residual term

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\epsilon} $

accounts for measurement noise, including effects of flow disturbances caused by the drone (e.g., downwash), errors in the assumed known parameters, limitations of the forward model, and representation errors (van Leeuwen, Reference van Leeuwen2015).

$ \boldsymbol{\epsilon} $

accounts for measurement noise, including effects of flow disturbances caused by the drone (e.g., downwash), errors in the assumed known parameters, limitations of the forward model, and representation errors (van Leeuwen, Reference van Leeuwen2015).

This inverse problem is inherently nonlinear and ill-posed, and is further complicated by sparse, noisy, and intermittent data due to atmospheric turbulence and limited sampling. We adopt a probabilistic framework based on Bayesian inference (Jaynes, Reference Jaynes2003) to invert the observation model, Eq. (2.1), and obtain an uncertainty-aware estimate of the uncertain source parameters

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

(Sanz-Alonso et al., Reference Sanz-Alonso, Stuart and Taeb2023).

$ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

(Sanz-Alonso et al., Reference Sanz-Alonso, Stuart and Taeb2023).

2.1.1. Observation model

The observational data vector

![]() $ {\boldsymbol{d}}_t=\left[c\left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right),v\left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right),\phi \left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right)\right] $

consists of instantaneous measurements of CH

$ {\boldsymbol{d}}_t=\left[c\left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right),v\left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right),\phi \left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right)\right] $

consists of instantaneous measurements of CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

concentration

$ {}_4 $

concentration

![]() $ c\left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right)\;\left[\mathrm{ppm}\right] $

, horizontal wind speed

$ c\left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right)\;\left[\mathrm{ppm}\right] $

, horizontal wind speed

![]() $ v\left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right)\;\left[\mathrm{m}\hskip0.1em {\mathrm{s}}^{-1}\right] $

, and wind direction

$ v\left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right)\;\left[\mathrm{m}\hskip0.1em {\mathrm{s}}^{-1}\right] $

, and wind direction

![]() $ \phi \left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right)\;\left[{}^{\circ}\right] $

, recorded at location

$ \phi \left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right)\;\left[{}^{\circ}\right] $

, recorded at location

![]() $ \boldsymbol{x}=\left[x,y,z\right]\;\left[\mathrm{m}\right] $

and time step

$ \boldsymbol{x}=\left[x,y,z\right]\;\left[\mathrm{m}\right] $

and time step

![]() $ t\hskip0.22em \left[-\right] $

. Our goal is to infer the mean emission rate

$ t\hskip0.22em \left[-\right] $

. Our goal is to infer the mean emission rate

![]() $ Q\hskip0.22em \left[\mathrm{kg}\hskip0.1em {\mathrm{h}}^{-1}\right] $

and the horizontal source location

$ Q\hskip0.22em \left[\mathrm{kg}\hskip0.1em {\mathrm{h}}^{-1}\right] $

and the horizontal source location

![]() $ {\boldsymbol{x}}_{\mathrm{s}}=\left[{x}_{\mathrm{s}},{y}_{\mathrm{s}}\right]\hskip0.24em \left[\mathrm{m}\right] $

. Additionally, we infer two nuisance parameters (Jaynes, Reference Jaynes2003): the mean horizontal wind speed

$ {\boldsymbol{x}}_{\mathrm{s}}=\left[{x}_{\mathrm{s}},{y}_{\mathrm{s}}\right]\hskip0.24em \left[\mathrm{m}\right] $

. Additionally, we infer two nuisance parameters (Jaynes, Reference Jaynes2003): the mean horizontal wind speed

![]() $ V\hskip0.22em \left[\mathrm{m}\hskip0.1em {\mathrm{s}}^{-1}\right] $

and the mean wind direction

$ V\hskip0.22em \left[\mathrm{m}\hskip0.1em {\mathrm{s}}^{-1}\right] $

and the mean wind direction

![]() $ \Phi \hskip0.22em \left[{}^{\circ}\right] $

, which are not of primary interest but improve the robustness of the inference. The full vector of uncertain parameters that we seek to infer is thus

$ \Phi \hskip0.22em \left[{}^{\circ}\right] $

, which are not of primary interest but improve the robustness of the inference. The full vector of uncertain parameters that we seek to infer is thus

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\theta} =\left[Q,{x}_{\mathrm{s}},{y}_{\mathrm{s}},V,\Phi \right] $

.

$ \boldsymbol{\theta} =\left[Q,{x}_{\mathrm{s}},{y}_{\mathrm{s}},V,\Phi \right] $

.

To facilitate probabilistic inference, we model the residuals between observations and model predictions as Gaussian noise. However, real-world CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

concentration and wind data often exhibit non-normal error distributions. To address this mismatch, we apply Box–Cox transformations (Box and Cox, Reference Box and Cox1964) within the observation model. These transformations, parameterized by

$ {}_4 $

concentration and wind data often exhibit non-normal error distributions. To address this mismatch, we apply Box–Cox transformations (Box and Cox, Reference Box and Cox1964) within the observation model. These transformations, parameterized by

![]() $ \lambda $

, map non-normal data from physical space into a transformed observation space where the residuals more closely approximate normality. Separate transformations are applied to CH

$ \lambda $

, map non-normal data from physical space into a transformed observation space where the residuals more closely approximate normality. Separate transformations are applied to CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

concentration, wind speed, and wind direction, each with its own optimal

$ {}_4 $

concentration, wind speed, and wind direction, each with its own optimal

![]() $ \lambda $

and transformed observation error standard deviation

$ \lambda $

and transformed observation error standard deviation

![]() $ {\sigma}^{\left(\lambda \right)} $

. To construct the nature run, these parameters are calibrated using real-world drone measurements to replicate realistic measurement noise (see Section 3.1 for their reported values).

$ {\sigma}^{\left(\lambda \right)} $

. To construct the nature run, these parameters are calibrated using real-world drone measurements to replicate realistic measurement noise (see Section 3.1 for their reported values).

We define the transformed observation model as a system of equations evaluated at each time step

![]() $ t $

:

$ t $

:

$$ {\boldsymbol{d}}_t^{\left(\lambda \right)}=\left\{\begin{array}{l}c{\left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right)}^{\left(\lambda \right)}=C{\left(\boldsymbol{x}\right)}^{\left(\lambda \right)}+{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}_C^{\left(\lambda \right)},\\ {}v{\left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right)}^{\left(\lambda \right)}={V}^{\left(\lambda \right)}+{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}_V^{\left(\lambda \right)},\\ {}\phi {\left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right)}^{\left(\lambda \right)}={\Phi}^{\left(\lambda \right)}+{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}_{\Phi}^{\left(\lambda \right)},\end{array}\right. $$

$$ {\boldsymbol{d}}_t^{\left(\lambda \right)}=\left\{\begin{array}{l}c{\left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right)}^{\left(\lambda \right)}=C{\left(\boldsymbol{x}\right)}^{\left(\lambda \right)}+{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}_C^{\left(\lambda \right)},\\ {}v{\left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right)}^{\left(\lambda \right)}={V}^{\left(\lambda \right)}+{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}_V^{\left(\lambda \right)},\\ {}\phi {\left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right)}^{\left(\lambda \right)}={\Phi}^{\left(\lambda \right)}+{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}_{\Phi}^{\left(\lambda \right)},\end{array}\right. $$

where

![]() $ C\left(\boldsymbol{x}\right)\hskip0.22em \left[\mathrm{ppm}\right] $

denotes the temporally averaged CH

$ C\left(\boldsymbol{x}\right)\hskip0.22em \left[\mathrm{ppm}\right] $

denotes the temporally averaged CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

concentration at the location

$ {}_4 $

concentration at the location

![]() $ \boldsymbol{x} $

, and

$ \boldsymbol{x} $

, and

![]() $ {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}^{\left(\lambda \right)}=\left[{\unicode{x025B}}_C^{\left(\lambda \right)},{\unicode{x025B}}_V^{\left(\lambda \right)},{\unicode{x025B}}_{\Phi}^{\left(\lambda \right)}\right] $

represents additive observational and model errors in the transformed space. We assume that these transformed residuals follow a multivariate normal distribution:

$ {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}^{\left(\lambda \right)}=\left[{\unicode{x025B}}_C^{\left(\lambda \right)},{\unicode{x025B}}_V^{\left(\lambda \right)},{\unicode{x025B}}_{\Phi}^{\left(\lambda \right)}\right] $

represents additive observational and model errors in the transformed space. We assume that these transformed residuals follow a multivariate normal distribution:

![]() $ {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}^{\left(\lambda \right)}\sim \mathcal{N}\left(0,{\mathbf{R}}_{\lambda}\right) $

, where

$ {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}^{\left(\lambda \right)}\sim \mathcal{N}\left(0,{\mathbf{R}}_{\lambda}\right) $

, where

![]() $ {\mathbf{R}}_{\lambda } $

is a diagonal covariance matrix encoding the standard deviations of the transformed observation errors.

$ {\mathbf{R}}_{\lambda } $

is a diagonal covariance matrix encoding the standard deviations of the transformed observation errors.

The mean concentration field

![]() $ C\left(\boldsymbol{x}\right) $

is modeled using an advection–dispersion formulation from Vergassola et al. (Reference Vergassola, Villermaux and Shraiman2007) that simulates particle transport under turbulent atmospheric conditions:

$ C\left(\boldsymbol{x}\right) $

is modeled using an advection–dispersion formulation from Vergassola et al. (Reference Vergassola, Villermaux and Shraiman2007) that simulates particle transport under turbulent atmospheric conditions:

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}C\left(\boldsymbol{x}\right)=\frac{\alpha Q}{4\pi K\mid \boldsymbol{x}-{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\mathrm{s}}\mid}\exp \left(\frac{-\left(x-{x}_{\mathrm{s}}\right)V\sin \left(\Phi \right)}{2K}\right)\\ {}\exp \left(\frac{-\left(y-{y}_{\mathrm{s}}\right)V\cos \left(\Phi \right)}{2K}\right)\exp \left(\frac{-\mid \boldsymbol{x}-{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\mathrm{s}}\mid }{\mathrm{\mathcal{L}}}\right)+{C}_0,\end{array}} $$

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}C\left(\boldsymbol{x}\right)=\frac{\alpha Q}{4\pi K\mid \boldsymbol{x}-{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\mathrm{s}}\mid}\exp \left(\frac{-\left(x-{x}_{\mathrm{s}}\right)V\sin \left(\Phi \right)}{2K}\right)\\ {}\exp \left(\frac{-\left(y-{y}_{\mathrm{s}}\right)V\cos \left(\Phi \right)}{2K}\right)\exp \left(\frac{-\mid \boldsymbol{x}-{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\mathrm{s}}\mid }{\mathrm{\mathcal{L}}}\right)+{C}_0,\end{array}} $$

where

![]() $ {C}_0\hskip0.22em \left[\mathrm{ppm}\right] $

is the background CH

$ {C}_0\hskip0.22em \left[\mathrm{ppm}\right] $

is the background CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

concentration, and

$ {}_4 $

concentration, and

![]() $ K\hskip0.22em \left[{\mathrm{m}}^2\hskip0.1em {\mathrm{s}}^{-1}\right] $

represents the mean effective diffusivity, which comprises both turbulent diffusivity and the generally much smaller molecular diffusivity (Stull, Reference Stull1989). The conversion factor

$ K\hskip0.22em \left[{\mathrm{m}}^2\hskip0.1em {\mathrm{s}}^{-1}\right] $

represents the mean effective diffusivity, which comprises both turbulent diffusivity and the generally much smaller molecular diffusivity (Stull, Reference Stull1989). The conversion factor

![]() $ \alpha $

incorporates the ideal gas law using air temperature

$ \alpha $

incorporates the ideal gas law using air temperature

![]() $ T $

and atmospheric pressure

$ T $

and atmospheric pressure

![]() $ P $

to facilitate unit conversion between mass concentration

$ P $

to facilitate unit conversion between mass concentration

![]() $ \left[\mathrm{kg}\hskip0.22em {\mathrm{m}}^{-3}\right] $

and mixing ratio

$ \left[\mathrm{kg}\hskip0.22em {\mathrm{m}}^{-3}\right] $

and mixing ratio

![]() $ \left[\mathrm{ppm}\right] $

, as well as between temporal units. Additionally,

$ \left[\mathrm{ppm}\right] $

, as well as between temporal units. Additionally,

![]() $ \alpha $

includes a factor of

$ \alpha $

includes a factor of

![]() $ 2 $

to account for CH

$ 2 $

to account for CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

mass conservation, assuming a ground-level source with dispersion over flat terrain. The effective dispersion length scale

$ {}_4 $

mass conservation, assuming a ground-level source with dispersion over flat terrain. The effective dispersion length scale

![]() $ \mathrm{\mathcal{L}}\hskip0.22em \left[\mathrm{m}\right] $

is defined as:

$ \mathrm{\mathcal{L}}\hskip0.22em \left[\mathrm{m}\right] $

is defined as:

$$ \mathrm{\mathcal{L}}=\sqrt{\frac{K\tau}{1+\frac{V^2\tau }{4K}}}, $$

$$ \mathrm{\mathcal{L}}=\sqrt{\frac{K\tau}{1+\frac{V^2\tau }{4K}}}, $$

where

![]() $ \tau \hskip0.22em \left[\mathrm{s}\right] $

is the atmospheric lifetime of CH

$ \tau \hskip0.22em \left[\mathrm{s}\right] $

is the atmospheric lifetime of CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

.

$ {}_4 $

.

The vector of assumed known input parameters to the forward model is

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\zeta} =\left[\boldsymbol{x},{z}_{\mathrm{s}},\tau, K,{C}_0,T,P\right] $

, where

$ \boldsymbol{\zeta} =\left[\boldsymbol{x},{z}_{\mathrm{s}},\tau, K,{C}_0,T,P\right] $

, where

![]() $ {z}_{\mathrm{s}}=0\;\mathrm{m} $

is the source height and

$ {z}_{\mathrm{s}}=0\;\mathrm{m} $

is the source height and

![]() $ \tau =9.1 $

years (Prather et al., Reference Prather, Holmes and Hsu2012) is the atmospheric lifetime of CH

$ \tau =9.1 $

years (Prather et al., Reference Prather, Holmes and Hsu2012) is the atmospheric lifetime of CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

. The remaining fixed parameters used to construct the nature run are derived from the real-world drone experimental data (see Section 3.1).

$ {}_4 $

. The remaining fixed parameters used to construct the nature run are derived from the real-world drone experimental data (see Section 3.1).

2.1.2. Bayesian inference

We adopt a sequential Bayesian inference (also known as filtering) approach (Murphy, Reference Murphy2023; Särkkä and Svensson, Reference Särkkä and Svensson2023) to estimate the uncertain parameters

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

from indirect observations

$ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

from indirect observations

![]() $ \boldsymbol{d} $

, integrating prior knowledge with new observational data and quantifying uncertainty in the estimates.

$ \boldsymbol{d} $

, integrating prior knowledge with new observational data and quantifying uncertainty in the estimates.

In our setting, inference is performed sequentially: each new set of observations—comprising CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

concentration, wind speed, and wind direction—triggers a single Bayesian update, allowing the posterior distribution to evolve over time as more data are collected. At each new time step

$ {}_4 $

concentration, wind speed, and wind direction—triggers a single Bayesian update, allowing the posterior distribution to evolve over time as more data are collected. At each new time step

![]() $ t+1 $

, the prior distribution over the unknown parameters

$ t+1 $

, the prior distribution over the unknown parameters

![]() $ p\left(\boldsymbol{\theta} |{\boldsymbol{d}}_{0:t}\right) $

is updated to a posterior distribution

$ p\left(\boldsymbol{\theta} |{\boldsymbol{d}}_{0:t}\right) $

is updated to a posterior distribution

![]() $ p\left(\boldsymbol{\theta} |{\boldsymbol{d}}_{0:t+1}\right) $

conditioned on the new observation(s)

$ p\left(\boldsymbol{\theta} |{\boldsymbol{d}}_{0:t+1}\right) $

conditioned on the new observation(s)

![]() $ {\boldsymbol{d}}_{t+1} $

via Bayes’ rule:

$ {\boldsymbol{d}}_{t+1} $

via Bayes’ rule:

In our plume model, the uncertain parameters

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

are treated as constants over time. Therefore, we apply particle filtering under the assumption of a static model (Chopin, Reference Chopin2002; van Hove et al., Reference van Hove, Aalstad, Lind, Arndt, Odongo, Ceriani, Fava, Hulth and Pirk2025). The denominator is the model evidence (also known as marginal likelihood) (MacKay, Reference MacKay2003), acting as a normalizing constant:

$ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

are treated as constants over time. Therefore, we apply particle filtering under the assumption of a static model (Chopin, Reference Chopin2002; van Hove et al., Reference van Hove, Aalstad, Lind, Arndt, Odongo, Ceriani, Fava, Hulth and Pirk2025). The denominator is the model evidence (also known as marginal likelihood) (MacKay, Reference MacKay2003), acting as a normalizing constant:

In this sequential framework, the posterior at the time step

![]() $ t $

serves as the prior at the time step

$ t $

serves as the prior at the time step

![]() $ t+1 $

. For notational convenience, we define

$ t+1 $

. For notational convenience, we define

![]() $ {\boldsymbol{d}}_0 $

as an empty set, so that

$ {\boldsymbol{d}}_0 $

as an empty set, so that

![]() $ p\left(\boldsymbol{\theta} |{\boldsymbol{d}}_0\right) $

denotes the initial prior. We assume uniform priors over all elements of

$ p\left(\boldsymbol{\theta} |{\boldsymbol{d}}_0\right) $

denotes the initial prior. We assume uniform priors over all elements of

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

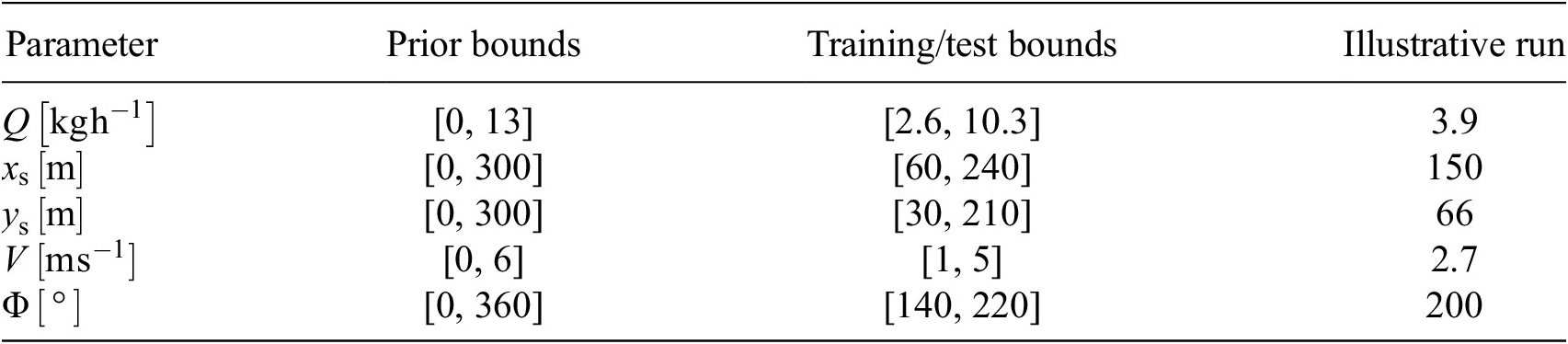

. The prior bounds, specified in Table 1, are deliberately chosen to encompass the bounds of the training and testing domains to avoid biasing the inference process. Additionally, we assume some prior knowledge of the prevailing wind direction, which informs the design of the measurement domain. Specifically, we position the measurement domain slightly downwind of the region where the source is expected to be located, increasing the likelihood of plume detection.

$ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

. The prior bounds, specified in Table 1, are deliberately chosen to encompass the bounds of the training and testing domains to avoid biasing the inference process. Additionally, we assume some prior knowledge of the prevailing wind direction, which informs the design of the measurement domain. Specifically, we position the measurement domain slightly downwind of the region where the source is expected to be located, increasing the likelihood of plume detection.

Table 1. Uniform prior bounds, training/test scenario bounds, and true values used in the illustrative run for the five uncertain parameters. These parameters define the search space for Bayesian inference and reinforcement learning-based path planning strategies

The likelihood term

![]() $ p\left({\boldsymbol{d}}_{t+1}|\boldsymbol{\theta} \right) $

quantifies the agreement between the observed data and model predictions. In our implementation, the likelihood is modeled as a multivariate Gaussian in Box–Cox transformed observation space (see Appendix B and Eq. [B.3]) following Smith et al., Reference Smith, Sharma, Marshall, Mehrotra and Sisson2010:

$ p\left({\boldsymbol{d}}_{t+1}|\boldsymbol{\theta} \right) $

quantifies the agreement between the observed data and model predictions. In our implementation, the likelihood is modeled as a multivariate Gaussian in Box–Cox transformed observation space (see Appendix B and Eq. [B.3]) following Smith et al., Reference Smith, Sharma, Marshall, Mehrotra and Sisson2010:

where

![]() $ \mathcal{F}{\left(\boldsymbol{\theta}, \boldsymbol{\zeta} \right)}^{\left(\lambda \right)} $

is the Box–Cox-transformed forward model prediction, and the observation error covariance

$ \mathcal{F}{\left(\boldsymbol{\theta}, \boldsymbol{\zeta} \right)}^{\left(\lambda \right)} $

is the Box–Cox-transformed forward model prediction, and the observation error covariance

![]() $ {\mathbf{R}}_{\lambda } $

is a diagonal matrix containing the square of the error standard deviations

$ {\mathbf{R}}_{\lambda } $

is a diagonal matrix containing the square of the error standard deviations

![]() $ {\sigma}^{\left(\lambda \right)} $

estimated via calibration against field data (see Section 2.4). The transformed likelihood (Eq. [2.7] and Eq. [B.3]) and evidence can be directly substituted into Eq. (2.5), as the Jacobian of the transformation term cancels out owing to its independence from

$ {\sigma}^{\left(\lambda \right)} $

estimated via calibration against field data (see Section 2.4). The transformed likelihood (Eq. [2.7] and Eq. [B.3]) and evidence can be directly substituted into Eq. (2.5), as the Jacobian of the transformation term cancels out owing to its independence from

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

(Jaynes, Reference Jaynes2003).

$ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

(Jaynes, Reference Jaynes2003).

2.1.3. Particle filter

In most real-world scenarios, exact Bayesian inference is computationally intractable due to the complexity and high dimensionality of the posterior distributions. We adopt a Sequential Monte Carlo approach (Chopin and Papaspiliopoulos, Reference Chopin and Papaspiliopoulos2020; Särkkä and Svensson, Reference Särkkä and Svensson2023) to approximate the posterior distribution of the uncertain parameters

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

.

$ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

.

The prior is represented by a weighted ensemble of particles:

where

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

denotes the state of a particle

$ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

denotes the state of a particle

![]() $ j $

,

$ j $

,

![]() $ {w}_t $

represents its corresponding weight at the time step

$ {w}_t $

represents its corresponding weight at the time step

![]() $ t $

(reflecting its probability given the data up to time step

$ t $

(reflecting its probability given the data up to time step

![]() $ t $

), and

$ t $

), and

![]() $ {N}_e $

is the total number of particles in the ensemble. The weights are self-normalized such that

$ {N}_e $

is the total number of particles in the ensemble. The weights are self-normalized such that

![]() $ {\sum}_{j=1}^{N_e}{w}_t^{(j)}=1 $

(Murphy, Reference Murphy2023).

$ {\sum}_{j=1}^{N_e}{w}_t^{(j)}=1 $

(Murphy, Reference Murphy2023).

At each iteration, the particle weights are updated using importance sampling based on the transformed likelihood, Eq. (2.7), of the new observation:

The weights

![]() $ {\overline{w}}_{t+1}^{(j)} $

are subsequently self-normalized to approximate the posterior

$ {\overline{w}}_{t+1}^{(j)} $

are subsequently self-normalized to approximate the posterior

![]() $ p\left(\boldsymbol{\theta} |{\boldsymbol{d}}_{0:t+1}\right) $

.

$ p\left(\boldsymbol{\theta} |{\boldsymbol{d}}_{0:t+1}\right) $

.

A common issue in particle filtering is degeneracy, where a small number of particle paths dominate the weight distribution (Murphy, Reference Murphy2023), leading to poor representation of the posterior distribution. To mitigate this, we deploy the resample-move algorithm (Gilks and Berzuini, Reference Gilks and Berzuini2001; Doucet and Johansen, Reference Doucet and Johansen2009), which combines resampling with a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) move step based on the Metropolis–Hastings algorithm.

To balance exploration and exploitation, we employ an adaptive step size for the MCMC proposals. The step size is set to the bandwidth of the dynamic prior particle distribution from time

![]() $ t $

, computed using Silverman’s rule, Eq. (D.2). This adaptive proposal distribution helps prevent premature convergence and supports robust posterior estimation. Reflective boundary conditions are applied to ensure that proposed particles remain within the prior bounds.

$ t $

, computed using Silverman’s rule, Eq. (D.2). This adaptive proposal distribution helps prevent premature convergence and supports robust posterior estimation. Reflective boundary conditions are applied to ensure that proposed particles remain within the prior bounds.

Online path planning requires data processing during collection, necessitating fast updates. As such, we use

![]() $ {N}_e=\mathrm{1,000} $

particles and a single MCMC move step per iteration, updating the posterior after each new observation

$ {N}_e=\mathrm{1,000} $

particles and a single MCMC move step per iteration, updating the posterior after each new observation

![]() $ {\boldsymbol{d}}_{t+1} $

.

$ {\boldsymbol{d}}_{t+1} $

.

2.2. Adaptive informative path planning

Optimizing the drone’s flight path for STE is formulated as a sequential decision-making problem under uncertainty. At each time step, the drone must decide where to move next in order to collect the most informative observations. We model this task as a Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (Kochenderfer et al., Reference Kochenderfer, Wheeler and Wray2022), where the agent, that is, the drone, interacts with the environment through a cycle of actions, observations, and belief updates.

In this framework, the agent does not have direct access to the true state of the environment

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

, but instead maintains a belief over the uncertain parameters, updated via the particle filter described in Section 2.1.3. The belief state at time step

$ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

, but instead maintains a belief over the uncertain parameters, updated via the particle filter described in Section 2.1.3. The belief state at time step

![]() $ t $

, denoted

$ t $

, denoted

![]() $ {s}_t $

, includes a representation of the distribution over the source parameters

$ {s}_t $

, includes a representation of the distribution over the source parameters

![]() $ p\left(\boldsymbol{\theta} |{\boldsymbol{d}}_{0:t}\right) $

, as well as assumed known parameters such as the drone’s current position

$ p\left(\boldsymbol{\theta} |{\boldsymbol{d}}_{0:t}\right) $

, as well as assumed known parameters such as the drone’s current position

![]() $ {\boldsymbol{x}}_t $

.

$ {\boldsymbol{x}}_t $

.

At each time step, the agent selects an action

![]() $ {a}_t $

from a discrete set of movement options in a three-dimensional domain: one step in any cardinal direction (north, south, east, and west), vertical movement (up and down), or remaining stationary. After executing the action, the agent receives new observations

$ {a}_t $

from a discrete set of movement options in a three-dimensional domain: one step in any cardinal direction (north, south, east, and west), vertical movement (up and down), or remaining stationary. After executing the action, the agent receives new observations

![]() $ {\boldsymbol{d}}_{t+1} $

, a numerical reward

$ {\boldsymbol{d}}_{t+1} $

, a numerical reward

![]() $ {r}_{t+1} $

, and transitions to a new belief state

$ {r}_{t+1} $

, and transitions to a new belief state

![]() $ {s}_{t+1} $

. The episode terminates after a fixed number of steps, simulating battery life.

$ {s}_{t+1} $

. The episode terminates after a fixed number of steps, simulating battery life.

The agent’s objective is to maximize the expected cumulative reward, defined as the sum of discounted future rewards over a finite horizon:

$$ {G}_t={r}_{t+1}+\gamma {r}_{t+2}+{\gamma}^2{r}_{t+3}+\dots =\sum \limits_{k=t+1}^{t_{\mathrm{final}}}{\gamma}^{k-t-1}{r}_k, $$

$$ {G}_t={r}_{t+1}+\gamma {r}_{t+2}+{\gamma}^2{r}_{t+3}+\dots =\sum \limits_{k=t+1}^{t_{\mathrm{final}}}{\gamma}^{k-t-1}{r}_k, $$

where

![]() $ \gamma \in \left[0,1\right] $

is the discount factor controlling the agent’s planning horizon, and

$ \gamma \in \left[0,1\right] $

is the discount factor controlling the agent’s planning horizon, and

![]() $ {t}_{\mathrm{final}} $

is the final time step of the episode. In our setting, the reward function is based on information gain—specifically, the reduction in entropy of the posterior relative to the dynamic prior (see Section 2.3). This encourages the agent to collect observations that most effectively reduce uncertainty.

$ {t}_{\mathrm{final}} $

is the final time step of the episode. In our setting, the reward function is based on information gain—specifically, the reduction in entropy of the posterior relative to the dynamic prior (see Section 2.3). This encourages the agent to collect observations that most effectively reduce uncertainty.

To explore different planning horizons, we evaluate both myopic (short-sighted) and non-myopic (long-term) policies, as described in the following section.

2.2.1. Myopic and non-myopic policies

The agent’s decision-making is governed by a policy

![]() $ \pi $

, which maps belief states to actions. We consider two classes of policies that differ in their planning horizon: myopic and non-myopic. In a myopic policy, the agent selects actions based solely on the expected immediate reward. This corresponds to setting the discount factor

$ \pi $

, which maps belief states to actions. We consider two classes of policies that differ in their planning horizon: myopic and non-myopic. In a myopic policy, the agent selects actions based solely on the expected immediate reward. This corresponds to setting the discount factor

![]() $ \gamma =0 $

in Eq. (2.10), reducing the return to

$ \gamma =0 $

in Eq. (2.10), reducing the return to

![]() $ {G}_t={r}_{t+1} $

. In contrast, a non-myopic policy considers the long-term consequences of actions by using a discount factor

$ {G}_t={r}_{t+1} $

. In contrast, a non-myopic policy considers the long-term consequences of actions by using a discount factor

![]() $ \gamma $

close to 1, thereby incorporating future rewards into the decision-making process.

$ \gamma $

close to 1, thereby incorporating future rewards into the decision-making process.

To guide action selection, we estimate the action-value function

![]() $ {q}_{\pi}\left(s,a\right)={\unicode{x1D53C}}_{\pi}\left[{G}_t|{s}_t=s,{a}_t=a\right] $

, which represents the expected return when taking action

$ {q}_{\pi}\left(s,a\right)={\unicode{x1D53C}}_{\pi}\left[{G}_t|{s}_t=s,{a}_t=a\right] $

, which represents the expected return when taking action

![]() $ a $

in belief state

$ a $

in belief state

![]() $ s $

and following the policy

$ s $

and following the policy

![]() $ \pi $

thereafter. A greedy agent selects the action that maximizes the function:

$ \pi $

thereafter. A greedy agent selects the action that maximizes the function:

![]() $ \pi (s)=\arg {\max}_aq\left(s,a\right) $

.

$ \pi (s)=\arg {\max}_aq\left(s,a\right) $

.

The optimal action-value function

![]() $ {q}_{\ast}\left(s,a\right) $

satisfies the Bellman optimality equation:

$ {q}_{\ast}\left(s,a\right) $

satisfies the Bellman optimality equation:

$$ {q}_{\ast}\left(s,a\right)=\unicode{x1D53C}\left[{r}_{t+1}+\gamma \underset{a^{\prime }}{\max }{q}_{\ast}\left({s}_{t+1},{a}^{\prime}\right)|{s}_t=s,{a}_t=a\right]. $$

$$ {q}_{\ast}\left(s,a\right)=\unicode{x1D53C}\left[{r}_{t+1}+\gamma \underset{a^{\prime }}{\max }{q}_{\ast}\left({s}_{t+1},{a}^{\prime}\right)|{s}_t=s,{a}_t=a\right]. $$

In practice, computing this expectation exactly is infeasible due to the high dimensionality of the belief space and the stochastic nature of observations. We therefore rely on sample-based approximations.

For the myopic policy with

![]() $ \gamma =0 $

, the Bellman optimality equation simplifies to:

$ \gamma =0 $

, the Bellman optimality equation simplifies to:

![]() $ {q}_{\ast}\left(s,a\right)=\unicode{x1D53C}\left[{r}_{t+1}|{s}_t=s,{a}_t=a\right] $

, which we estimate using Monte Carlo sampling. Specifically, we draw samples from the current belief state, simulate the outcome of each candidate action, and compute the expected immediate reward. To maintain computational efficiency during online decision-making, we limit the number of samples to one per candidate action, trading off accuracy for speed.

$ {q}_{\ast}\left(s,a\right)=\unicode{x1D53C}\left[{r}_{t+1}|{s}_t=s,{a}_t=a\right] $

, which we estimate using Monte Carlo sampling. Specifically, we draw samples from the current belief state, simulate the outcome of each candidate action, and compute the expected immediate reward. To maintain computational efficiency during online decision-making, we limit the number of samples to one per candidate action, trading off accuracy for speed.

In contrast, the non-myopic policy requires estimating the long-term value of actions. We approximate the action-value function using a parameterized function

![]() $ \hat{q}\left(s,a;\boldsymbol{\omega} \right) $

, implemented as a deep neural network with weights

$ \hat{q}\left(s,a;\boldsymbol{\omega} \right) $

, implemented as a deep neural network with weights

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\omega} $

. The training of this network through deep reinforcement learning is described in the following section.

$ \boldsymbol{\omega} $

. The training of this network through deep reinforcement learning is described in the following section.

2.2.2. Reinforcement learning

To implement the non-myopic policy, we use reinforcement learning (RL) (Sutton and Barto, Reference Sutton and Barto2018), specifically deep Q-learning (Mnih et al., Reference Mnih, Kavukcuoglu, Silver, Rusu, Veness, Bellemare, Graves, Riedmiller, Fidjeland, Ostrovski, Petersen, Beattie, Sadik, Antonoglou, King, Kumaran, Wierstra, Legg and Hassabis2015), for the approximation of the optimal action-value function

![]() $ {q}_{\ast}\left(s,a\right) $

. This is achieved using a feedforward neural network parameterized by weights

$ {q}_{\ast}\left(s,a\right) $

. This is achieved using a feedforward neural network parameterized by weights

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\omega} $

, denoted by

$ \boldsymbol{\omega} $

, denoted by

![]() $ \hat{q}\left(s,a;\boldsymbol{\omega} \right) $

. The network is implemented in Python using TensorFlow (Martín et al., Reference Martín, Agarwal, Barham, Brevdo, Chen, Citro, Corrado, Davis, Dean, Devin, Ghemawat, Goodfellow, Harp, Irving, Isard, Jia, Jozefowicz, Kaiser, Kudlur, Levenberg, Mané, Monga, Moore, Murray, Olah, Schuster, Shlens, Steiner, Sutskever, Talwar, Tucker, Vanhoucke, Vasudevan, Viégas, Vinyals, Warden, Wattenberg, Wicke, Yu and Zheng2015).

$ \hat{q}\left(s,a;\boldsymbol{\omega} \right) $

. The network is implemented in Python using TensorFlow (Martín et al., Reference Martín, Agarwal, Barham, Brevdo, Chen, Citro, Corrado, Davis, Dean, Devin, Ghemawat, Goodfellow, Harp, Irving, Isard, Jia, Jozefowicz, Kaiser, Kudlur, Levenberg, Mané, Monga, Moore, Murray, Olah, Schuster, Shlens, Steiner, Sutskever, Talwar, Tucker, Vanhoucke, Vasudevan, Viégas, Vinyals, Warden, Wattenberg, Wicke, Yu and Zheng2015).

The architecture consists of three fully connected hidden layers with 512, 256, and 128 units, respectively, each using rectified linear unit activation functions. The output layer is linear, with one node per action, that is, seven nodes for navigation in a three-dimensional (3D) domain, representing the estimated action values

![]() $ \hat{q}\left(s,a;\boldsymbol{\omega} \right) $

.

$ \hat{q}\left(s,a;\boldsymbol{\omega} \right) $

.

The input to the network includes a discretized belief map over the source location and wind direction, the drone’s current position, and a representation of previously visited observation locations within the domain (see Appendix E).

Training is conducted over 25,000 iterations, with 12 mini-batch updates per iteration. Each update uses 32 transitions sampled uniformly from a replay buffer of 10,000 transitions.

The Q-values are updated using the standard Q-learning rule:

where

![]() $ \eta =0.0001 $

is the learning rate, optimized using the Adam optimizer (Diederik and Jimmy, Reference Kingma and Ba2015). The target Q-value is computed using a separate target network

$ \eta =0.0001 $

is the learning rate, optimized using the Adam optimizer (Diederik and Jimmy, Reference Kingma and Ba2015). The target Q-value is computed using a separate target network

![]() $ {\hat{q}}_{\mathrm{target}} $

, which is synchronized with the main network every 500 iterations to improve training stability.

$ {\hat{q}}_{\mathrm{target}} $

, which is synchronized with the main network every 500 iterations to improve training stability.

Exploration is managed using an

![]() $ \unicode{x025B} $

-greedy policy. The exploration rate

$ \unicode{x025B} $

-greedy policy. The exploration rate

![]() $ \unicode{x025B} $

starts at

$ \unicode{x025B} $

starts at

![]() $ 1.0 $

and decays toward

$ 1.0 $

and decays toward

![]() $ 0.01 $

over the course of training, encouraging exploration early on and exploitation of learned strategies later. While training was conducted for 25,000 episodes, we observed that cumulative reward sometimes deteriorated during the final stages of training. To ensure robust evaluation, we then selected the policy from an earlier, better-performing iteration.

$ 0.01 $

over the course of training, encouraging exploration early on and exploitation of learned strategies later. While training was conducted for 25,000 episodes, we observed that cumulative reward sometimes deteriorated during the final stages of training. To ensure robust evaluation, we then selected the policy from an earlier, better-performing iteration.

2.2.3. Centralized multi-agent system

In a centralized multi-agent framework, multiple agents collaboratively maintain a joint belief over the environment. Since agents’ actions are interdependent, optimal decision-making requires selecting joint actions from the combined action space, which grows exponentially with the number of agents. To manage this complexity, we restrict our study to two agents operating in a two-dimensional domain. This simplification reduces the size of the joint action space and makes centralized coordination computationally feasible for our synthetic experiments.

In the collaborative setting, the joint belief is updated sequentially at each time step using the observational data from each agent, resulting in two inference steps, one for each agent. For comparison, we also evaluate a non-collaborative scenario in which each drone follows its own trajectory and maintains an independent belief.

In addition, we explore an alternative inference approach where the joint belief is updated in a single inference step using aggregated observational data. Specifically, at each time step, the observations from both agents are concatenated into a single vector and assimilated jointly, rather than sequentially.

Training of the centralized multi-agent RL (Albrecht et al., Reference Albrecht, Christianos and Schäfer2024) policy with joint assimilation is conducted over three training sessions, each comprising 25,000 iterations. In the first session, the exploration rate

![]() $ \unicode{x025B} $

decays from

$ \unicode{x025B} $

decays from

![]() $ 1.0 $

to

$ 1.0 $

to

![]() $ 0.01 $

. In the second and third sessions,

$ 0.01 $

. In the second and third sessions,

![]() $ \unicode{x025B} $

decays from

$ \unicode{x025B} $

decays from

![]() $ 0.5 $

to

$ 0.5 $

to

![]() $ 0.01 $

. Subsequently, the policy with sequential assimilation is initialized from the joint assimilation policy and retrained over an additional 25,000 iterations, with

$ 0.01 $

. Subsequently, the policy with sequential assimilation is initialized from the joint assimilation policy and retrained over an additional 25,000 iterations, with

![]() $ \unicode{x025B} $

decaying from

$ \unicode{x025B} $

decaying from

![]() $ 0.5 $

to

$ 0.5 $

to

![]() $ 0.01 $

.

$ 0.01 $

.

2.3. Information entropy

Our primary objective is to obtain accurate and precise estimates of the source term parameters. To this end, we define a reward function based on information entropy

![]() $ \mathcal{H}\left(\cdot \right) $

, which quantifies the uncertainty associated with these parameters. This approach incentivizes actions that reduce uncertainty in the agent’s belief state.

$ \mathcal{H}\left(\cdot \right) $

, which quantifies the uncertainty associated with these parameters. This approach incentivizes actions that reduce uncertainty in the agent’s belief state.

Entropy reflects how uncertain we are about a random variable; the higher the entropy, the less we know about its value (MacKay, Reference MacKay2003). We prioritize entropy over variance, as variance can be misleading, particularly in multimodal distributions where high variance may still correspond to informative beliefs. Entropy is maximal for uniform distributions, such as our priors, and decreases as the distribution becomes more constrained. We define the reward at each time step as the reduction in entropy between successive belief states, that is, information gain (Lindley, Reference Lindley1956):

For continuous distributions, entropy generalizes to differential entropy, defined as:

where

![]() $ p\left(\boldsymbol{\theta} \right) $

denotes the probability density over the unknown parameters

$ p\left(\boldsymbol{\theta} \right) $

denotes the probability density over the unknown parameters

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

. We use the natural logarithm base

$ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

. We use the natural logarithm base

![]() $ \mathrm{e} $

, yielding entropy in units of

$ \mathrm{e} $

, yielding entropy in units of

![]() $ \left[\mathrm{nats}\right] $

.

$ \left[\mathrm{nats}\right] $

.

In our framework, the posterior distribution

![]() $ p\left(\boldsymbol{\theta} \right) $

is approximated by a weighted particle set, Eq. (2.8). The integral in Eq. (2.14) is then approximated via Monte Carlo integration:

$ p\left(\boldsymbol{\theta} \right) $

is approximated by a weighted particle set, Eq. (2.8). The integral in Eq. (2.14) is then approximated via Monte Carlo integration:

$$ \mathcal{H}(s)\approx -\sum \limits_{j=1}^{N_e}{w}^{(j)}\log p\left({\boldsymbol{\theta}}^{(j)}\right), $$

$$ \mathcal{H}(s)\approx -\sum \limits_{j=1}^{N_e}{w}^{(j)}\log p\left({\boldsymbol{\theta}}^{(j)}\right), $$

where

![]() $ {\boldsymbol{\theta}}^{(j)} $

are the particles and

$ {\boldsymbol{\theta}}^{(j)} $

are the particles and

![]() $ {w}^{(j)} $

their associated weights.

$ {w}^{(j)} $

their associated weights.

Following Fischer and Tas (Reference Fischer, Tas, Daumé and Aarti2020), we employ kernel density estimation (KDE) (Gisbert, Reference Gisbert2003) to calculate differential entropy from a weighted particle set. KDE provides a smooth approximation of the posterior density from the weighted particle ensemble. Further implementation details are provided in Appendix D.

Several previous STE studies (e.g., Hutchinson et al., Reference Hutchinson, Liu and Chen2019a; Hutchinson et al., Reference Hutchinson, Liu, Thomas and Chen2020; Park et al., Reference Park, An, Seo and Oh2021) approximate entropy using only the particle weights:

$$ \mathcal{H}(s)\approx -\sum \limits_{j=1}^{N_e}{w}^{(j)}\log {w}^{(j)}. $$

$$ \mathcal{H}(s)\approx -\sum \limits_{j=1}^{N_e}{w}^{(j)}\log {w}^{(j)}. $$

This formulation neglects the spatial distribution and density of particles in the parameter space. As noted by Boers et al. (Reference Boers, Driessen, Bagchi and Mandal2010), such an approximation is sensitive to resampling: since resampling assigns uniform weights (

![]() $ {w}^{(j)}=1/{N}_e $

), it can artificially reduce the entropy to a constant value, regardless of the actual distribution of particles. In contrast, the KDE-based approach incorporates both particle weights and their positions, yielding a more accurate and informative measure of uncertainty. While this method is computationally more demanding, it avoids misleading entropy estimates.

$ {w}^{(j)}=1/{N}_e $

), it can artificially reduce the entropy to a constant value, regardless of the actual distribution of particles. In contrast, the KDE-based approach incorporates both particle weights and their positions, yielding a more accurate and informative measure of uncertainty. While this method is computationally more demanding, it avoids misleading entropy estimates.

2.4. Nature run

In this study, we evaluate different path-planning strategies through synthetic experiments, where observations are generated by a nature run that serves as a proxy for “true” plume dispersion in an Arctic environment. The nature run is a calibrated observation model (see Section 2.1.1) constructed using real-world data from a field experiment. This experiment involved drone-based measurements at a legacy borehole in Adventdalen, Svalbard, which is normally sealed and inactive. The borehole—well 1967–1971—was originally drilled during coal exploration by Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani, and reaches a depth of

![]() $ 106\;\mathrm{m} $

. The well intersects a shallow gas accumulation at the base of the permafrost within the Lower Cretaceous Helvetiafjellet Formation. Between 1967 and 1975, the well intermittently produced over 2.5 million cubic meters of

$ 106\;\mathrm{m} $

. The well intersects a shallow gas accumulation at the base of the permafrost within the Lower Cretaceous Helvetiafjellet Formation. Between 1967 and 1975, the well intermittently produced over 2.5 million cubic meters of

![]() $ {\mathrm{CH}}_4 $

. The borehole is situated in a valley where the permafrost is ice-saturated and acts as an effective cryogenic seal, trapping gas beneath it (Birchall et al., Reference Birchall, Jochmann, Betlem, Senger, Hodson and Olaussen2023).

$ {\mathrm{CH}}_4 $

. The borehole is situated in a valley where the permafrost is ice-saturated and acts as an effective cryogenic seal, trapping gas beneath it (Birchall et al., Reference Birchall, Jochmann, Betlem, Senger, Hodson and Olaussen2023).

Following a flood and subsequent freezing period, structural damage to the borehole was suspected to have initiated a leak. We drilled five shallow holes in the surface ice to release trapped

![]() $ {\mathrm{CH}}_4 $

and allowed ~

$ {\mathrm{CH}}_4 $

and allowed ~

![]() $ 30\;\min $

for flow stabilization prior to measurement.

$ 30\;\min $

for flow stabilization prior to measurement.

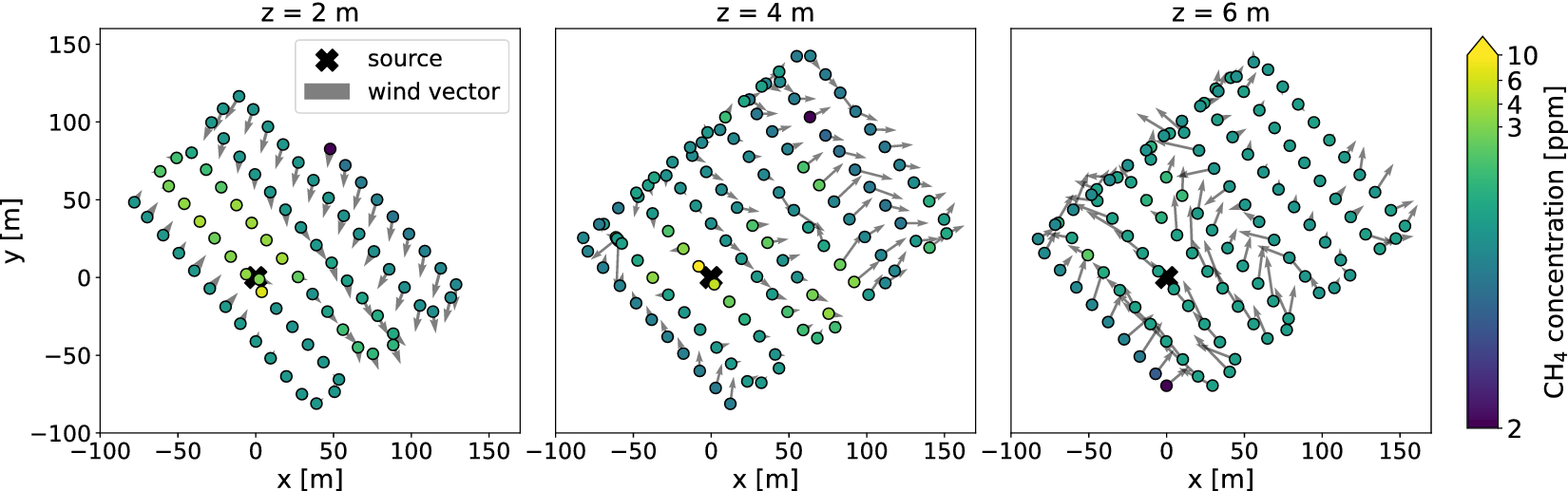

The field experiment was performed on 1 February 2025, using a DJI M300 RTK quadcopter (DJI, China) equipped with an AERIES MIRA Strato LDS methane gas sensor (Aeries Technologies, USA) and a Trisonica Sphere 3D sonic anemometer (LI-COR, USA) (see Figure 2). Atmospheric observations were collected over a

![]() $ 150\;\mathrm{m}\times 200\;\mathrm{m} $

area surrounding the source. The drone followed a preplanned lawnmower flight pattern at altitudes of ~2, ~4, and ~

$ 150\;\mathrm{m}\times 200\;\mathrm{m} $

area surrounding the source. The drone followed a preplanned lawnmower flight pattern at altitudes of ~2, ~4, and ~

![]() $ 6\;\mathrm{m} $

above ground level, moving at a speed of

$ 6\;\mathrm{m} $

above ground level, moving at a speed of

![]() $ 1.4\;\mathrm{m}\hskip0.22em {\mathrm{s}}^{-1} $

.

$ 1.4\;\mathrm{m}\hskip0.22em {\mathrm{s}}^{-1} $

.

Figure 2. (a) The drone used in the field experiment, equipped with a methane sensor mounted underneath, and a 3D sonic anemometer on top. The pole with reflectors marks the location of the leaking borehole. Methane was released by drilling five shallow holes through the ice to access the underlying water. Credit: Gina Schulz. (b) The drone is collecting atmospheric observations near the borehole.

The gas sensor measured CH

![]() $ {}_4 $

concentrations via mid-infrared laser spectroscopy at

$ {}_4 $

concentrations via mid-infrared laser spectroscopy at

![]() $ 1\;\mathrm{Hz} $

, while the sonic anemometer recorded wind speed and direction at

$ 1\;\mathrm{Hz} $

, while the sonic anemometer recorded wind speed and direction at

![]() $ 20\;\mathrm{Hz} $

. Wind measurements were corrected for drone motion (pitch, roll, yaw, and translation).

$ 20\;\mathrm{Hz} $

. Wind measurements were corrected for drone motion (pitch, roll, yaw, and translation).

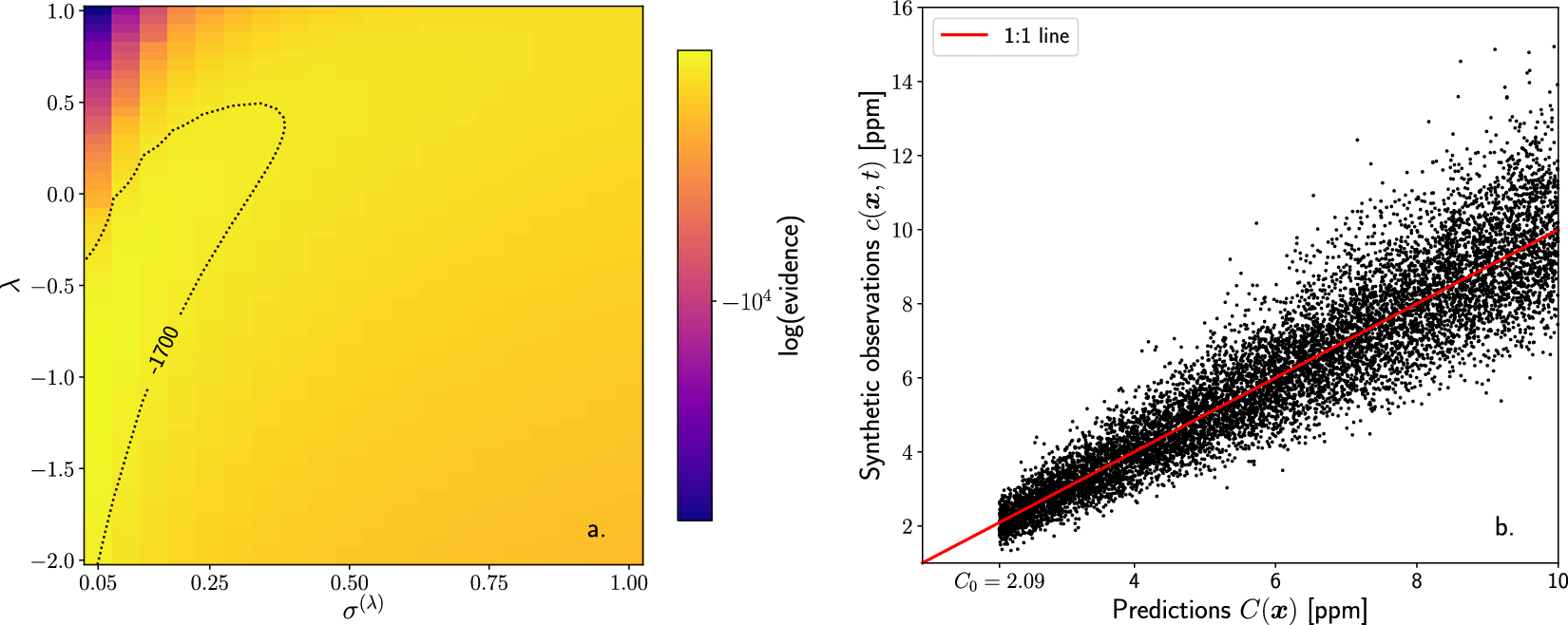

The collected data were used to calibrate the following parameters in the nature run: (i) the effective diffusivity

![]() $ K $

using the Businger–Dyer relationship (Appendix A), (ii) the background concentration

$ K $

using the Businger–Dyer relationship (Appendix A), (ii) the background concentration

![]() $ {C}_0 $

, atmospheric temperature

$ {C}_0 $

, atmospheric temperature

![]() $ T $

, and pressure

$ T $

, and pressure

![]() $ P $

, (iii) the Box–Cox transformation parameters

$ P $

, (iii) the Box–Cox transformation parameters

![]() $ \lambda $

and the transformed observation error standard deviations

$ \lambda $

and the transformed observation error standard deviations

![]() $ {\unicode{x025B}}^{\left(\lambda \right)} $

for concentration, wind speed, and wind direction in Eq. (2.2). In addition, an estimate of the emission rate from the leak is provided.

$ {\unicode{x025B}}^{\left(\lambda \right)} $

for concentration, wind speed, and wind direction in Eq. (2.2). In addition, an estimate of the emission rate from the leak is provided.

For wind data, we calibrate the transformation parameters by applying MLE to wind speed and direction measurements from the field experiment (see Appendix B). Following the observation model, Eq. (2.2), we directly infer the mean wind speed

![]() $ V $

and direction

$ V $

and direction

![]() $ \Phi $

from the observed quantities

$ \Phi $

from the observed quantities

![]() $ v\left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right) $

and

$ v\left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right) $

and

![]() $ \phi \left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right) $

, allowing us to apply MLE directly to the observed data to estimate the Box–Cox parameters. In contrast, for concentration

$ \phi \left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right) $

, allowing us to apply MLE directly to the observed data to estimate the Box–Cox parameters. In contrast, for concentration

![]() $ c\left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right) $

, the inference involves hidden parameters in

$ c\left(\boldsymbol{x},t\right) $

, the inference involves hidden parameters in

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

that are nonlinearly and indirectly related to the temporally averaged concentration

$ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

that are nonlinearly and indirectly related to the temporally averaged concentration

![]() $ C\left(\boldsymbol{x}\right) $

. Consequently, we adopt a more sophisticated particle-based Bayesian model comparison approach to calibrate the transformation parameters for the concentration error model (see Appendix C).

$ C\left(\boldsymbol{x}\right) $

. Consequently, we adopt a more sophisticated particle-based Bayesian model comparison approach to calibrate the transformation parameters for the concentration error model (see Appendix C).

2.5. Synthetic experiments

The synthetic experiments are designed to reflect the conditions of the field experiment. The simulation domain is

![]() $ 330\;\mathrm{m}\times 330\;\mathrm{m} $

, discretized into an

$ 330\;\mathrm{m}\times 330\;\mathrm{m} $

, discretized into an

![]() $ 11\times 11 $

grid. The resolution of

$ 11\times 11 $

grid. The resolution of

![]() $ 30\;\mathrm{m} $

was chosen as a compromise: a finer grid would offer greater spatial precision for drone navigation but increase the computational costs of RL policy training, while a coarser grid would reduce computational costs at the expense of navigation flexibility and possibly source localization accuracy. For single-agent test cases, observations are collected at altitudes of

$ 30\;\mathrm{m} $

was chosen as a compromise: a finer grid would offer greater spatial precision for drone navigation but increase the computational costs of RL policy training, while a coarser grid would reduce computational costs at the expense of navigation flexibility and possibly source localization accuracy. For single-agent test cases, observations are collected at altitudes of

![]() $ 2\;\mathrm{m} $

,

$ 2\;\mathrm{m} $

,

![]() $ 4\;\mathrm{m} $

, and

$ 4\;\mathrm{m} $

, and

![]() $ 6\;\mathrm{m} $

above ground level. We assume some prior knowledge of the prevailing wind direction, as is typically available in field deployments, and initialize the drone downwind of the source at position

$ 6\;\mathrm{m} $

above ground level. We assume some prior knowledge of the prevailing wind direction, as is typically available in field deployments, and initialize the drone downwind of the source at position

![]() $ \left[\mathrm{0,300,6}\right]\;\mathrm{m} $

. We evaluate flight durations of 108, 54, and 27 steps. To reduce computational costs in multi-agent test cases, data collection is restricted to a fixed altitude of

$ \left[\mathrm{0,300,6}\right]\;\mathrm{m} $

. We evaluate flight durations of 108, 54, and 27 steps. To reduce computational costs in multi-agent test cases, data collection is restricted to a fixed altitude of

![]() $ 2\;\mathrm{m} $

, with both drones starting at

$ 2\;\mathrm{m} $

, with both drones starting at

![]() $ \left[\mathrm{0,300,2}\right]\;\mathrm{m} $

. We consider flights of 27 steps.

$ \left[\mathrm{0,300,2}\right]\;\mathrm{m} $

. We consider flights of 27 steps.

The RL policy is trained offline using domain randomization. In each training episode, the true values for the uncertain parameters

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

to be inferred are uniformly sampled from the ranges specified in Table 1. Policy performance is assessed across the same parameter ranges using a testbed of 25,000 simulated flights. During both training and testing, synthetic observations are generated from the nature run. Specifically, we sample from the transformed observation model defined in Eq. (2.2), and then apply an inverse Box–Cox transformation to recover observations in physical space. This model incorporates: (i) the forward model, which takes as input the sampled true values of

$ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

to be inferred are uniformly sampled from the ranges specified in Table 1. Policy performance is assessed across the same parameter ranges using a testbed of 25,000 simulated flights. During both training and testing, synthetic observations are generated from the nature run. Specifically, we sample from the transformed observation model defined in Eq. (2.2), and then apply an inverse Box–Cox transformation to recover observations in physical space. This model incorporates: (i) the forward model, which takes as input the sampled true values of

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

and the assumed known input parameters

$ \boldsymbol{\theta} $

and the assumed known input parameters

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\zeta} $

(as specified in Sections 2.1.1 and 3.1); (ii) Box–Cox transformation parameters

$ \boldsymbol{\zeta} $

(as specified in Sections 2.1.1 and 3.1); (ii) Box–Cox transformation parameters

![]() $ \lambda $

; and (iii) a Gaussian error model in the transformed observation space, with calibrated noise parameters

$ \lambda $

; and (iii) a Gaussian error model in the transformed observation space, with calibrated noise parameters

![]() $ {\sigma}^{\left(\lambda \right)} $

detailed in Section 3.1.

$ {\sigma}^{\left(\lambda \right)} $

detailed in Section 3.1.

2.5.1. Performance metrics

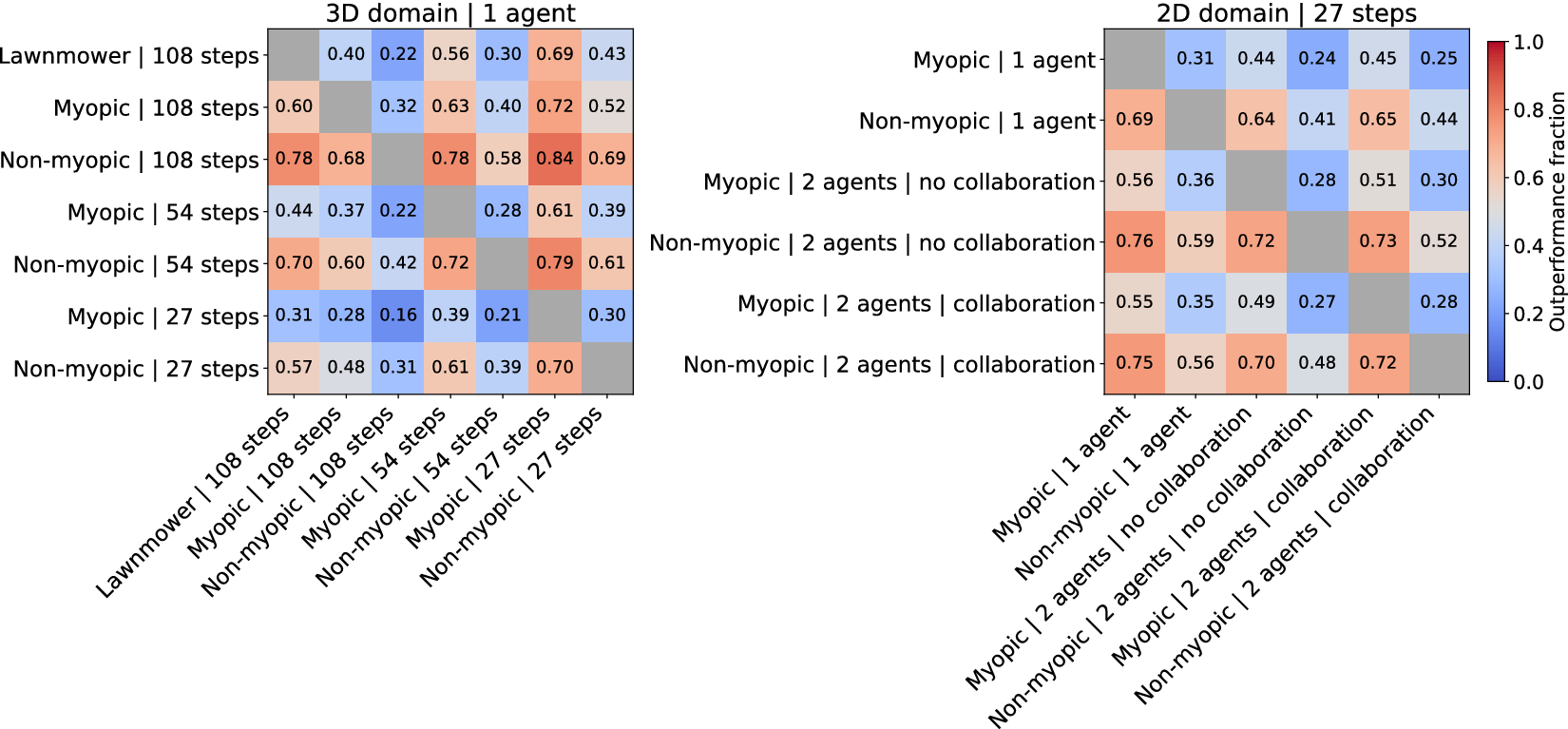

Policy performance is assessed using entropy-based and probabilistic scoring metrics. Continuous Ranked Probability Score (

![]() $ \mathrm{CRPS} $

) (Hersbach, Reference Hersbach2000) is a proper scoring rule (Gneiting and Raftery, Reference Gneiting and Raftery2007) that evaluates the quality of probabilistic forecasts by comparing the predicted distribution to the true value. Lower

$ \mathrm{CRPS} $

) (Hersbach, Reference Hersbach2000) is a proper scoring rule (Gneiting and Raftery, Reference Gneiting and Raftery2007) that evaluates the quality of probabilistic forecasts by comparing the predicted distribution to the true value. Lower

![]() $ \mathrm{CRPS} $

values indicate better performance, with a score of zero corresponding to a perfectly sharp and accurate prediction. While entropy measures the precision of the posterior distribution,

$ \mathrm{CRPS} $

values indicate better performance, with a score of zero corresponding to a perfectly sharp and accurate prediction. While entropy measures the precision of the posterior distribution,

![]() $ \mathrm{CRPS} $

captures both precision and accuracy but requires access to the true value.

$ \mathrm{CRPS} $

captures both precision and accuracy but requires access to the true value.

We evaluate policy performance using the following metrics: (i) Cumulative information gain, also referred to as entropy reduction, denoted by

![]() $ \varDelta \mathcal{H}\left[\mathrm{nats}\right] $

. This metric quantifies the total reduction in uncertainty over the course of the flight from the initial prior at

$ \varDelta \mathcal{H}\left[\mathrm{nats}\right] $

. This metric quantifies the total reduction in uncertainty over the course of the flight from the initial prior at

![]() $ t=0 $

to the final posterior. (ii)

$ t=0 $

to the final posterior. (ii)

![]() $ \mathrm{CRPS} $

for emission rate, denoted by

$ \mathrm{CRPS} $

for emission rate, denoted by

![]() $ {\mathrm{CRPS}}_Q\hskip0.22em \left[\mathrm{kg}\hskip0.1em {\mathrm{h}}^{-1}\right] $

. This metric evaluates the accuracy and precision of the posterior distribution for the emission rate

$ {\mathrm{CRPS}}_Q\hskip0.22em \left[\mathrm{kg}\hskip0.1em {\mathrm{h}}^{-1}\right] $

. This metric evaluates the accuracy and precision of the posterior distribution for the emission rate

![]() $ Q $

. (iii)

$ Q $

. (iii)

![]() $ \mathrm{CRPS} $

for source location, denoted by

$ \mathrm{CRPS} $

for source location, denoted by

![]() $ {\mathrm{CRPS}}_{{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\mathrm{s}}}\hskip0.1em \left[\mathrm{m}\right] $

. This is computed as the

$ {\mathrm{CRPS}}_{{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\mathrm{s}}}\hskip0.1em \left[\mathrm{m}\right] $

. This is computed as the

![]() $ \mathrm{CRPS} $

of the Euclidean distance between the estimated and true source location

$ \mathrm{CRPS} $

of the Euclidean distance between the estimated and true source location

![]() $ {\boldsymbol{x}}_{\mathrm{s}} $

. (iv) Normalized

$ {\boldsymbol{x}}_{\mathrm{s}} $

. (iv) Normalized

![]() $ \mathrm{CRPS} $

, denoted by

$ \mathrm{CRPS} $

, denoted by

![]() $ {\mathrm{CRPS}}_{\mathrm{norm}}\left[-\right] $

, which assesses the improvement of the posterior over the initial prior, averaged across both

$ {\mathrm{CRPS}}_{\mathrm{norm}}\left[-\right] $