The Nordic countries are a model of cooperation and they consistently punch above their weight in meeting the challenges of our time … There have been times where I’ve said, why don’t we just put all these small countries in charge for a while? And they could clean things up.

The Nordic nations – Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden – are poised to spark a global transformation of capitalism.Footnote 1 Amid escalating sustainability challenges, widening social inequalities, and mounting threats to democracy, the need to reimagine American capitalism is urgent. Nordic capitalism offers compelling examples of how to harness the strengths of capitalism while addressing its shortcomings, inspiring and informing others in the ambition to realize sustainable capitalism.

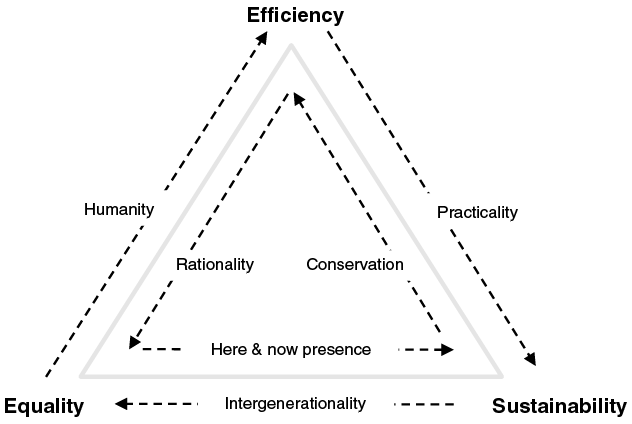

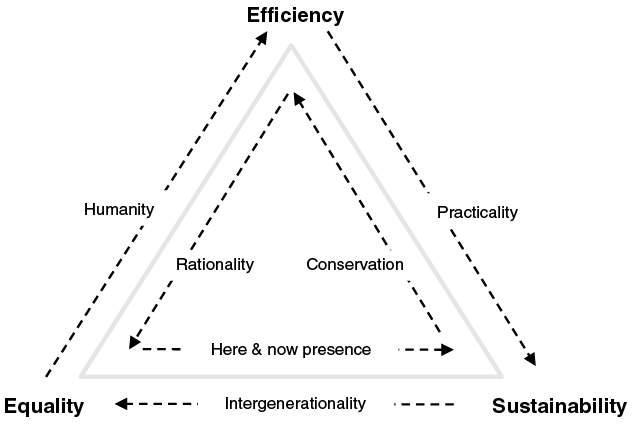

This book defines sustainable capitalism as development realized through capitalistic principles that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

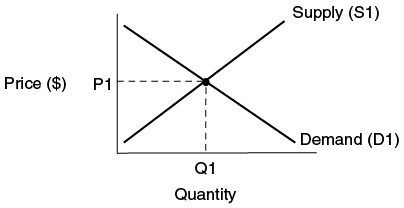

Realizing sustainable capitalism will require markets that align profit with sustainability, where sustainable companies and practices are profitable and unsustainable companies and practices are unprofitable. Markets must be crafted to ensure sustainability is rewarded.Footnote 2

Most investors allocate their capital based on the world as it is and as they expect it to be – not as it ought to be. Smart policies and good governance are therefore essential to construct markets that bring us closer to a world where all people can live with dignity, while operating within the Earth’s planetary boundaries so future generations have the same opportunity. The Nordic nations have made significant strides in designing policies that align markets with sustainability and exemplify good governance, offering valuable lessons for realizing sustainable capitalism. Figure 1.1 illustrates the nations that comprise the Nordic region.

Figure 1.1 Map of the Nordics.

As the world’s largest and most consumptive economy, with the largest pools of investable capital, the US must play a central role in advancing global sustainability. While the Nordic nations’ relatively small scale limits their direct global impact, they offer powerful examples of how to transform capitalism. By demonstrating how market economies can successfully balance profit with social and environmental concerns, Nordic capitalism could inspire necessary changes in American capitalism and, by extension, catalyze much needed global transformations.

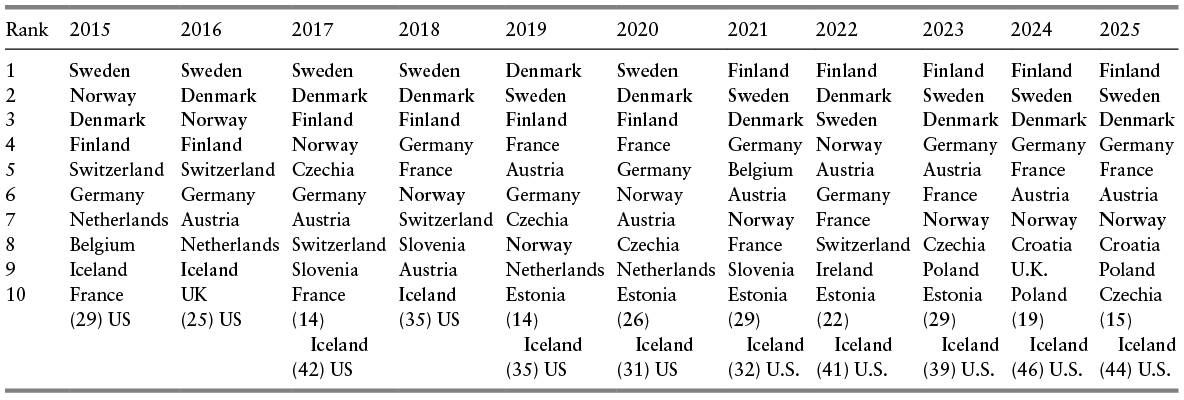

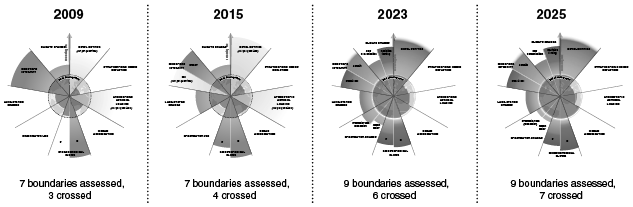

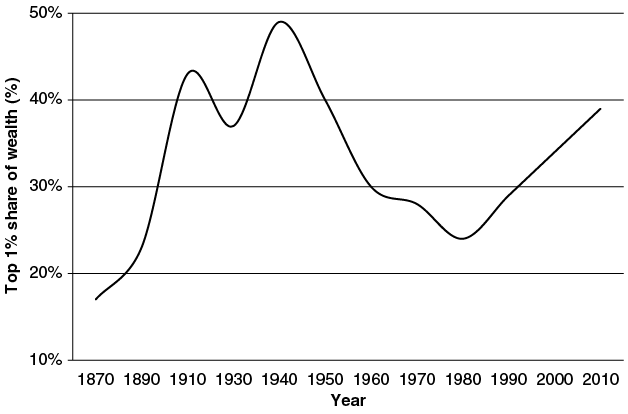

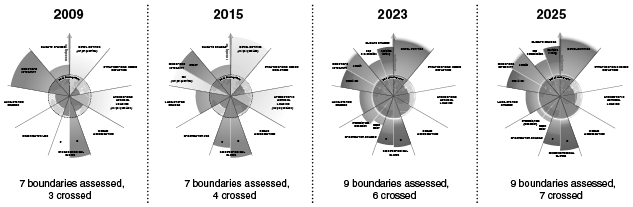

Their comparatively strong performances on global benchmarks demonstrate the Nordics’ potential for global leadership in transforming capitalism. Established by the United Nations in 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a globally recognized framework of seventeen interlinked objectives to tackle pressing issues, including poverty, inequality, and climate change. The SDGs are described as a “shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future.”Footnote 3 Nordic nations consistently excel in SDG performances. Denmark, Finland, and Sweden have occupied the top three global spots yearly since the index’s inception in 2015, with the no. 1 position rotating among them, as shown in Table 1.1. The Sustainable Development Report 2024 summarizes, “Nordic countries continue to lead on SDG achievement.”Footnote 4

Table 1.1Long description

Table shows the top 10 country rankings from 2015 to 2025, with the United States and Iceland's ranks noted outside the top 10 in some years. Finland holds the rank 1 position most recently from 2021 to 2025, succeeding Sweden from 2015 to 2018, 2020, and Denmark in 2019. Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Finland consistently occupy the top 4 spots throughout the decade. Notable trends include Norway consistently ranking in the top 7, Germany in the top 6, and France and Austria frequently in the top 10. The U.S. rankings fluctuate significantly, ranging from a high of 25 in 2016 to a low of 46 in 2024, while Iceland, which started in the top 10 from 2015 to 2016 and 2018, generally ranks between 14 and 29 in later years. The list of top 10 countries includes Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Belgium, Iceland, France, the U.K., Czechia, Slovenia, Estonia, Ireland, Poland, and Croatia over the 11 years.

Nordic leadership extends across virtually every measure of societal well-being, highlighting Nordic nations’ strengths in fostering societal well-being and sustainability. Finland has held the top spot in the annual World Happiness Report for eight consecutive years, followed by Denmark no. 2, Iceland no. 3, and Sweden no. 4 in the 2025 global rating.Footnote 5 The Democracy Index 2023 Report by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) declares, “The Nordic countries continue to dominate the Democracy Index rankings, taking five of the top six spots,” with Norway rated the most democratic country in the world for fourteen consecutive years.Footnote 6 Iceland has topped the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Global Gender Gap Index for fifteen years straight, with Iceland at no. 1, Finland no. 2, and Norway no. 3 in the 2024 edition.Footnote 7 Denmark has topped Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index for seven straight years, with Finland at no. 2 in the 2024 ranking.Footnote 8 Nordic nations routinely top the Environmental Performance Index,Footnote 9 Robeco Country Sustainability Ranking,Footnote 10 WEF Energy Transition Index,Footnote 11 Global Peace Index,Footnote 12 Prosperity Index,Footnote 13 and the Women, Peace and Security Index.Footnote 14

Influential voices consistently praise the Nordics. The Economist heralded the Nordics as “the next supermodel” in its 2013 special issue focused on Nordic countries.Footnote 15 The WEF’s Global Competitiveness Report 2020 highlighted, “The Nordic model stands out as the most promising in transitioning towards a productive, sustainable, and inclusive economic system.”Footnote 16 Francis Fukuyama argued that “Getting to Denmark” – establishing stable, prosperous, and inclusive societies founded on deliberative democracy and the rule of law – should be a global aim. He later acknowledged he “might as well have said ‘Getting to Norway,’” recognizing the equally remarkable story of Norwegian modernization.Footnote 17

The New York Times columnist David Brooks observed, “Almost everybody admires the Nordic model. Countries like Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Finland have high economic productivity, high social equality, high social trust, and high levels of personal happiness.”Footnote 18 Political analyst Fareed Zakaria captured the pragmatic essence of Nordic success in his 2020 book, Ten Lessons for a Post-Pandemic World. Speaking of the Nordic nations, Zakaria offered they “understood that markets are incredibly powerful, yet insufficient alone; they require supports, buffers, and supplements. We should all adapt their best practices to our national contexts. There really is no alternative.”Footnote 19

US economist Jeffrey Sachs stated, “It is possible to combine a high level of income, growth, and innovation with a high degree of social protection. The Nordic societies of Northern Europe have done it. And their experience sheds considerable light on the choices for others.”Footnote 20 Former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan highlighted the broader impact of the Nordic nations, noting their positive influence on global standards and practices. He underscored that the Nordics “have consistently supported the institutions and common values needed to make the world a fairer, more secure place.”Footnote 21

American progressives have long looked to Nordic nations as beacons of possibility. In 1966, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. praised Sweden’s commitment to racial justice, declaring, “Never before has a nation come forth with such total commitment to our cause. Truly, Sweden is a nation with a conscience.”Footnote 22 Like many American reformers before and since, King saw in Nordic society a mirror that reflected both inspiration and implicit critique of American shortcomings.

The Nordic commitment to sustainability extends beyond government policy into the private sector, where Nordic companies consistently lead global sustainability rankings. From 2005 to 2024, Denmark was home to more of the “world’s most sustainable companies” according to the Corporate Knights Global 100 ranking than any other nation, despite being only about the size of the US state of Wisconsin.Footnote 23

While Nordic societies often receive accolades for their achievements and are sometimes discussed in nearly utopian terms, they face significant challenges and demonstrate many shortcomings. Nordic nations consume resources in excess of planetary boundaries, contributing to climate change and biodiversity loss. Nordic societies face the challenge of aging populations, which are increasingly straining the universal services that comprise the Nordic Model. Racism persists as a significant challenge, evident both in the rise of nationalist political parties and more covertly in colorblind policies that obscure understanding of racial inequalities. Acknowledging these shortcomings does not diminish the value of Nordic capitalism; instead, it underscores the importance of critical reflection and a commitment to continuous improvement.

The term “utopia” – derived from the Greek words for “no place” – reminds us that no society is without flaws. While some Americans idealize the Nordic model, others view it as dystopian. These stark contrasts in perception reveal more about American political orientations than Nordic realities: The Nordic system often serves as a Rorschach test, appearing utopian to those on the political left and dystopian to those on the right.Footnote 24 This book adopts a pragmatic approach, utilizing careful benchmarking to identify actionable lessons for improvement while acknowledging that the Nordics are neither perfect nor completely imperfect. That said, just as the US has imparted many valuable lessons to the world despite its many flaws, Nordic capitalism offers valuable lessons for benchmarkers that adopt a curious and open mind.

The term “Nordic capitalism” used throughout this book might suggest a singular model, but each Nordic nation presents a distinct version of capitalism. However, the similarities among these Nordic capitalisms are far more pronounced than their differences, especially when contrasted with American capitalism. Therefore, we use Nordic capitalism as a convenient collective label.Footnote 25

Nordic Socialism? No

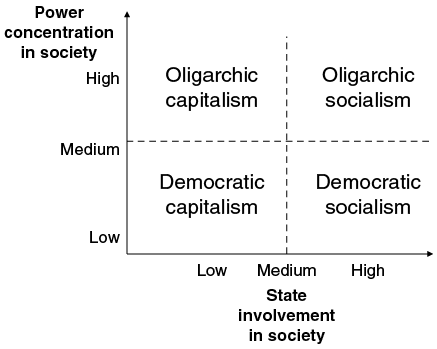

In the US, discussions surrounding Nordic policies frequently turn to the term “socialism.” Critics from the American political right routinely describe central features of the Nordic model – universal healthcare, paid parental leave, subsidized childcare – as a slippery slope to oppressive Soviet-style socialism. Conversely, critics of capitalism from the American political left sometimes hail the Nordics as paragons of successful socialism.

These polarized perspectives from the American political right and left fundamentally mischaracterize the Nordic political economy. As Chapter 3 details, Nordic nations adhere to capitalist principles: private ownership of property and capital, and market-driven economies. In short, Nordic capitalism is, indeed, capitalism.

In 2015, Denmark’s then Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen addressed the socialist misconception at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. Responding to US Senator Bernie Sanders’s praise of Denmark as a socialist success, Rasmussen, who was leader of the conservative Venstre Party, stated firmly, “I know that some people in the US associate the Nordic model with some sort of socialism. Therefore, I would like to make one thing clear. Denmark is far from a socialist planned economy. Denmark is a market economy.” He added, “The Nordic model is an expanded welfare state which provides a high level of security for its citizens but is also a successful market economy with much freedom to pursue your dreams and live your life as you wish.”Footnote 26

Similarly, the conservative Washington-based think tank Heritage Foundation highlights the success of capitalism in the Nordic countries in its 2020 report, Economic Freedom Underpins Nordic Prosperity. The authors assert, “The Nordic experience demonstrates that free-market capitalism, not big-government socialism, is the best path to enduring prosperity and resilience.”Footnote 27

There is agreement on this point even from the opposite end of the political spectrum. Nathan Robinson, author of Why You Should Be a Socialist, emphasizes that the Nordic countries are not socialist states but social democracies. In these systems, he notes, the private sector maintains control of property and capital – hallmarks of capitalism – while the state ensures universal access to essential services. Though Robinson finds Nordic-style capitalism more appealing than its American counterpart, he ultimately rejects it precisely because it remains fundamentally capitalist. He argues, “We might borrow Scandinavian social policies, such as paid parental leave and universal healthcare. But the [socialist] dream is transformative – the total elimination of exploitation and hierarchy, and a change in the structure of who owns capital.”Footnote 28

The capitalist nature of Nordic economies is further evidenced by their stock markets – institutions fundamental to private ownership and market exchange. Each Nordic nation maintains its own primary stock exchange, with most now operating as part of Nasdaq Nordic: Nasdaq Stockholm, Nasdaq Copenhagen, Nasdaq Helsinki, and Nasdaq Iceland. Norway’s Oslo Børs operates under Euronext. These exchanges, along with their auxiliary markets for smaller growth companies, facilitate the buying and selling of private ownership stakes in Nordic companies.

While Nordic populations typically dismiss American mischaracterizations of their societies as socialist without much comment, a 2018 Fox News segment proved harder to ignore. Fox News commentator Trish Regan equated Denmark with Venezuela and claimed that socialism in “Denmark, like Venezuela, has stripped people of their opportunities.” She alleged that everyone in Denmark works for the government and that its universal education system (tuition-free through university) yields fewer graduates who often pursue frivolous careers, like opening cupcake cafés.Footnote 29 The Danish response was swift. Parliamentary member Dan Jørgensen issued a rebuttal on YouTube that quickly went viral.

Drawing on data from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Jørgensen demonstrated that overall employment rates were, in fact, higher in Denmark than in the US. He speculated that the distinction lay in that, in Denmark, “people are paid a decent wage.” Jørgensen further refuted the education claims within the Fox News segment by citing WEF statistics, showing that Denmark ranked significantly higher than the US in measures of best educated populations. He pointed to Denmark’s universal education system, which provides both tuition and living stipends for all citizens, explaining: “It’s not the size of your parent’s bank account that decides whether or not you get an education. It’s your hard work; it’s your talent; it’s your motivation.”Footnote 30

In the US the term “socialism” evokes Cold War-era apprehensions. President Donald J. Trump echoed this sentiment in his 2019 State of the Union address, where he said, “Here, in the United States, we are alarmed by new calls to adopt socialism in our country,” in a thinly veiled reference to Nordic-style policies. Discussions about policies in Denmark, like tuition-free universities for all citizens, were on the rise at that time, as promoted by Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.Footnote 31 Trump asserted, “America was founded on liberty and independence – not government coercion, domination, and control. We are born free, and we will stay free. Tonight, we renew our resolve that America will never be a socialist country.”Footnote 32

Despite persistent warnings about the purported dangers of Nordic-style policies to freedom and democracy, empirical evidence demonstrates contrary outcomes.

Nordic nations continue to rank significantly higher than the US in the associated measures of freedom and democracy. The 2024 Democracy Index by the EIU exhibits the Nordic nations occupying five of the top seven global positions, with Norway at no. 1, Sweden at no. 3, Iceland at no. 4, Finland at no. 6, and Denmark at no. 7. The US ranks no. 28.Footnote 33 Similarly, the 2022 World Press Freedom Index ranks Norway no. 1, Denmark no. 2, Sweden no. 3, Finland no. 5, Iceland no. 15, while the US ranks no. 42.Footnote 34 The WEF’s Global Social Mobility Index also positions the Nordics on top, with Denmark leading the 2020 report and Norway at no. 2, Finland at no. 3, Sweden at no. 4, and Iceland at no. 5. By contrast, the US is placed no. 27.Footnote 35 The Nordic nations consistently outperform the US in comparative measurements of freedom for women, as illustrated by the WEF’s 2024 Global Gender Gap Report. Iceland, Finland, and Norway topped the global ranking while the US ranked no. 43.Footnote 36

Nordic business leaders and politicians across the political spectrum endorse policies often decried as socialism in the US, such as universal healthcare and subsidized childcare. These policies, central to the Nordic Model, relieve businesses from managing employee healthcare and losing productive workers who cannot afford childcare. Far from being socialist, these measures are widely embraced as vital to the success of Nordic capitalism.

Nordic business leaders also actively support and collaborate with labor unions, contrasting sharply with many US business leaders who frequently oppose them and sometimes even associate union activities with socialism. Thanks to strong labor unions, Denmark’s lowest-paid McDonald’s employee earn approximately $22 per hour. Labor unions are integral to the Nordic tripartite model. Under the tripartite model, labor and employers hold periodic collective bargaining agreements to set wages, with the state ready to act as a backstop if agreements falter.Footnote 37

McDonald’s remains profitable in Denmark despite the higher wages, and the cost of hamburgers remains accessible, thereby challenging a common American myth that higher wages inevitably lead to prohibitive consumer prices. As of 2021, a Big Mac in Denmark was priced at approximately $5.15, only a 7 percent increase compared to $4.80 in the US.Footnote 38 The lowest-paid workers in Denmark can easily afford the marginal price increase, given that they earn about three times more than their minimum wage-earning US counterparts.

“McDonald’s Workers in Denmark Pity Us: Danes Haven’t Built a ‘Socialist’ Country. Just One That Works,” reads the title of the 2020 New York Times article by Nicholas Kristof, describing the starkly different realities between the US and Nordic contexts for McDonald’s workers and the lowest-paid workers in society more generally. Denmark has constructed a version of capitalism that better ensures rank-and-file employees a share in the nation’s overall economic prosperity.Footnote 39

Yeah, but … (A Primer)

I often encounter skepticism when suggesting that the US could learn from Nordic experiences, typically met with the retort prefixed with “Yeah, but.” Common objections include, “Yeah, but the US is the freest nation in the world,” and “Yeah, but the Nordics are small and homogeneous.” I briefly address these objections here, with a more comprehensive response in Chapter 8.

Yeah, but the US Is the Freest Nation in the World

The US is the “freest nation in the world” is a common assertion by Americans, frequently invoked by prominent politicians. This claim often arises in response to critiques of systemic issues within the US, sometimes paired with the notion that adopting Nordic-like policies would undermine American freedoms. Such a comparative claim of “freest,” or any assertion of superiority, invites a rigorous comparative analysis. Yet, when pressed for evidence, responses often lack empirical support, relying instead on spurious claims or ad hominem attacks rather than substantive proof.

In 2022, following the devastating mass shooting in Uvalde, Texas – where a gunman killed nineteen children with a military-grade weapon at an elementary school – a British reporter questioned US Senator Ted Cruz about the alarming prevalence of mass shootings in the country. Rather than engaging with the substance of the question, Cruz dismissed the reporter as a “propagandist” and sarcastically retorted, “I’m sorry you think American exceptionalism is awful.” He then asserted US superiority: “Why do people come from all over the world to America? Because it’s the freest, most prosperous, safest country on Earth.”Footnote 40 Such comparative claims demand examination.

Freedom is deeply intertwined with a sense of safety – it is challenging to feel truly free when one’s safety, especially that of one’s children, is at risk. According to the 2023 Global Peace Index, Iceland and Denmark are ranked as the safest globally, with all Nordic countries, along with Australia, Canada, Germany, Japan, England, Costa Rica, Vietnam, Uruguay, and South Korea, outperforming the US.Footnote 41 The tragically high incidence of mass shootings in US schools is one of the many indicators where the US significantly trails Nordic nations in measures of safety.Footnote 42 Furthermore, in holistic measurements of freedom, Nordic nations outperform the US. For example, the 2023 Human Freedom Index, compiled by the conservative think tank Cato Institute in Washington, DC, places all five Nordic nations in the top ten, while the US ranks no. 17.Footnote 43 The empirical evidence starkly contradicts Senator Cruz’s comparative claims.

Comparative claims of US superiority often lack empirical backing, veering from healthy patriotism to dangerous denial. When these comparative claims are challenged, detractors are often dismissed as “anti-American,” reflecting a troubling trend where genuine issues are overshadowed by nationalistic fervor. The satirical title of Stephen Colbert’s book, America Again: Re-becoming the Greatness We Never Weren’t, humorously underscores the irony of unchecked American exceptionalism claims, which seriously hinder constructive discourse and the development of solutions for pressing issues.Footnote 44

Yeah, but the Nordics Are Small and Homogeneous

Some US audiences commonly theorize that the smallness and perceived homogeneity of Nordic nations, often stereotyped as exclusively white, renders Nordic experiences irrelevant in the US. The frequent hypothesis expressed is that because the US is large and diverse, something that works in the Nordics is unlikely to work in the US. It is important to immediately note that the Nordic nations are not exclusively white and have experienced significantly increased demographic diversification over the past decades.

That said, the US and the Nordics are indeed different contexts.

Nevertheless, the Nordics can offer valuable lessons for the US no different than how the US has provided lessons for the Nordics. I routinely host Nordic political and business leaders who come to the US to benchmark practices in diverse fields such as artificial intelligence, entrepreneurship, technology innovation, and food safety. Nordic benchmarking exercises have been a longstanding tradition. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, letters from Nordic emigrants in the US helped spur the adoption of innovative practices in their home countries, which were then lagging behind the US in industrial development. Adopted in 1814, the Norwegian Constitution was inspired by the U.S. Constitution, incorporating its principles of democracy and separation of powers. It is crucial to remember that learning can flow both ways across the Atlantic.

These Nordic explorations are best understood as benchmarking exercises – systematic analyses of successful practices that can inform improvements elsewhere. Effective benchmarking requires approaching different contexts with curiosity, humility, and an open mind, recognizing that valuable lessons can emerge from studying systems different from our own.

Benchmarking can occur at many different units of analysis – not solely at the national level. Nordic states, cities, companies, and specific programs can offer valuable lessons through benchmarking.

Many efforts in the US are coordinated at the state level – including education, transportation, law enforcement, prisons and correctional systems, elections, public health programs, land use, and energy and environmental policies. Nordic nations are, on average, about the size of mid sized US states like Wisconsin and Minnesota, the US’s no. 20 and no. 22 most populated states, respectively. Sweden is the largest Nordic nation at just over ten million people, a similar population to North Carolina and Michigan, no. 9 and no. 10 in the US, respectively. Iceland is the smallest Nordic nation, just below the population of Wyoming, which is no. 50. Therefore, the range of populations of the Nordic nations spans over 80 percent of US states.

US states could, for example, look to Finland for educational reform, digital government services, or universal subsidized childcare; Iceland for gender equality, sustainable fishing, or geothermal energy; Norway for electric vehicle adoption, integrated public transportation, or “Freedom to Roam” laws (Allemannsretten); Sweden for elder care, waste management and recycling, or efficient healthcare systems; Denmark for wind energy transition, voter participation, or universal paid parental leaves, and so on.

Even the largest states may prosper by turning their benchmarking gaze on the Nordic nations.

California is actively benchmarking the Norwegian correctional system. It is examining how Norway dramatically reduced its recidivism rates since the 1990s, when they mirrored those of the US, by shifting the focus from punishment to rehabilitation. Today, Norway’s recidivism rate is roughly half that of California’s.Footnote 45 California is the most populous US state and, if it were a country, would rank as the world’s fourth-largest economy, just ahead of Japan and behind only the US, China, and Germany.Footnote 46 Nevertheless, Norway offers California valuable insights for those open to learning.

University of California, San Francisco, public health researcher Cyrus Ahalt routinely leads US groups on benchmarking tours of Norwegian prisons. He remarked, “We hear ‘Norway’s so socialist’ or ‘Norway’s all white,’ which is actually not true,” as common dismissals from US audiences. However, Ahalt notes that when someone experiences the Norwegian prisons firsthand on a benchmarking excursion, “the skepticism and resistance evaporate.”Footnote 47 Secretary Ralph Diaz of California’s Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation emphasized that while California would not copy Norway’s system exactly, it could adapt valuable lessons for its diverse context. “We are not trying to make it the Norway way, or the European way, but the California way. We are a unique, diverse populous with cultures within cultures, but that doesn’t mean we can’t make necessary changes.”Footnote 48

Researchers also point to opportunities for California to learn from Denmark’s successes in establishing innovative circular systems at scale. Denmark is a global leader in aluminum, glass, and plastic beverage-container takeback systems, supported by well-designed recycling infrastructure and strong industry collaborations. Denmark also leads efforts to convert animal waste into energy, providing additional practical insights for meeting sustainability objectives. Denmark’s combination of state policy support and private sector innovation holds particular relevance for California, as it seeks to meet ambitious climate goals.Footnote 49 These lessons extend beyond California to other US states.

US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis famously asserted, “A single courageous State may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.”Footnote 50 Similarly, the Nordic nations are often described as “social laboratories,” where innovative policies are pragmatically tested and refined.Footnote 51 Encouraging state-level experimentation in the US by adapting proven Nordic policies could unlock powerful learning opportunities. However, as Jacob Grumbach warns in his 2022 book Laboratories against Democracy, the opposite is happening in many US states. Grumbach demonstrates that political, ideological, and economic interests are actively suppressing policy experimentation, undermining states’ ability to address pressing challenges.Footnote 52 This policy of suppression feeds into a neoliberal self-fulfilling prophecy: As state and federal governments become less effective, it reinforces the belief in their inherent inefficiency, justifying further reductions in the government’s role – a core tenet of neoliberal ideology.

Benchmarking has the potential to ignite meaningful change as growing public awareness of better alternatives challenges the status quo. When citizens recognize opportunities for improvement elsewhere, demands for change naturally intensify. The stark contrast between conditions under Soviet socialism and those in American capitalism once fueled Soviet citizens’ push for reform; they began asking, “Am I better off than Americans?”Footnote 53 In much the same way, Americans today may find themselves inspired to question their own systems, comparing their quality of life with that of Nordic citizens. As more people examine the strengths of Nordic capitalism in fostering well-being, these comparisons may galvanize calls to reform American capitalism to better serve US citizens.

However, benchmarking alone does not automatically overcome barriers to change or ensure the direct applicability of all lessons learned. Overcoming entrenched, powerful interests that benefit from maintaining the status quo is persistently challenging. Denial of major problems remains difficult to counter in the US, where entrenched interests, polarization, and strategic misinformation work together to obstruct efforts to confront shared challenges. Additionally, even when the need for change is widely recognized, achieving consensus on specific policies and practices to enact can be difficult, especially in politically divided environments. Indeed, the US and the Nordics are different contexts with different historical pathways and current conditions.

The US is much larger, has a more diverse population, and is arguably more divided, raising questions about the applicability of Nordic practices in the US. Does the US possess the necessary social solidarity to adopt such practices? Does the US have enough sense of “We” to implement change for the common good? While there are no simple answers, two important points are evident. First, the scale of the US is daunting, and the political gridlock at the national level can be demoralizing. Benchmarking at a more local level – comparing Nordic nations with US states, Nordic cities with US cities, Nordic companies with US companies, and so on – is more effective. Second, US audiences must actively avoid the reflex to dismiss Nordic approaches as “socialism,” which reinforces false equivalences with Soviet socialism and forecloses meaningful discussion.

One concern that necessitates immediate addressing is the misconception that directing attention to Nordic countries equates to celebrating “whiteness” or endorsing white supremacy. Such a concern is understandable, considering the disturbing historical connections between Nordic identity, whiteness, and systems of domination associated with white supremacy.Footnote 54 US eugenicist Madison Grant extolled “Nordicness” as the superior race in his xenophobic manifesto, The Passing of the Great Race, published in 1916.Footnote 55 Grant was associated with numerous notable US figures, including President Theodore Roosevelt, who praised the book as “the work of an American scholar and gentleman.”Footnote 56 Grant’s book also found its way into the hands of Adolf Hitler, who professed, “This book is my Bible.”Footnote 57 The Nazis infamously appropriated Nordic symbols and Viking imagery. The insurrectionists who attacked the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, prominently displayed Norse and Viking symbols, continuing a pattern of white supremacist movements appropriating Nordic cultural imagery.Footnote 58 During a meeting on immigration with lawmakers in the White House in 2018, President Trump reportedly questioned why the US accepted immigrants from Haiti and African countries, referring to them as “shithole countries,” remarking that the US should instead bring more immigrants “from places like Norway.” Trump’s remark was criticized as racially charged. It reflects a common discourse in the US conflating white supremacy with Nordic considerations.Footnote 59 The rise of nationalistic political groups in the Nordic region with their thinly veiled agendas promoting white supremacy, like the Sweden Democrats, further cement such harmful associations.

This persistent appropriation of Nordic identity by white supremacist movements demands careful attention when examining Nordic social and economic models. However, rejecting substantive examination of Nordic policy innovations due to such appropriation would effectively cede important practical lessons to extremist narratives.

Furthermore, the “yeah, but they’re homogeneous” argument can at times come across as “yeah, but they’re white” – as if whiteness somehow equates with performance. By most measures, Japan is a more homogeneous society than any of the Nordic societies. Yet in all my years as an industrial engineer benchmarking Japan for its efficiency advances of the 1970s into the 1990s, I never once heard “Yeah, but they’re homogeneous” as a counterargument, despite Japan having a far more homogeneous population and different cultural context than the US. Yet I receive this objection routinely when suggesting Americans could prosperously benchmark the Nordics. This disparity in response suggests that the “homogeneous” argument may sometimes serve as a proxy for racial assumptions that need to be directly confronted and challenged.

Nordics: From Poverty to Shared Prosperity

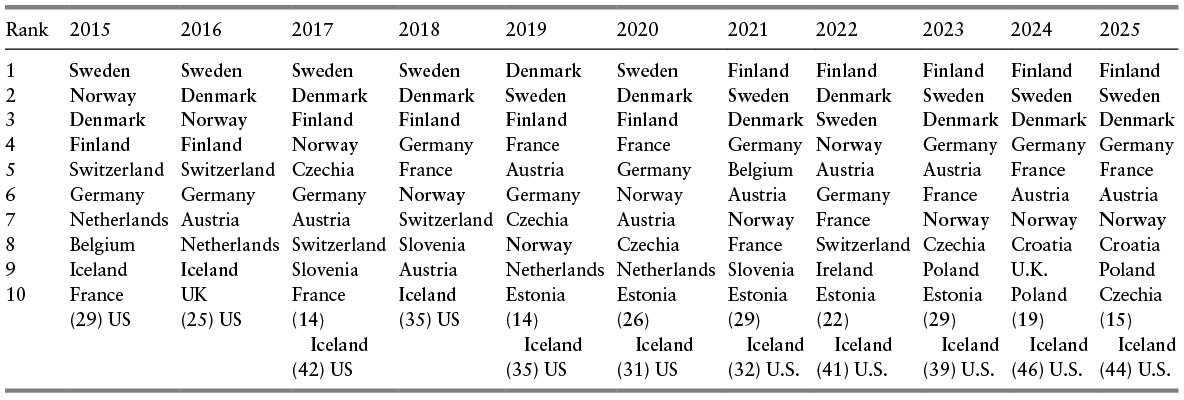

During the 1800s and early 1900s, Nordic societies were marked by poverty and inequality in stark contrast to their present-day egalitarian identity with high levels of shared prosperity. According to Thomas Piketty, the propertarian structure of Swedish society around the turn of the twentieth century rendered it “one of the most inegalitarian societies in the world.” Societal status was determined almost entirely by property ownership.Footnote 60

In contrast, the US represented a beacon of freedom and opportunity to many in Northern Europe. Beginning in the 1850s and continuing into the early 1900s, the promise of a better life drove millions of Nordic citizens to immigrate to the US – including my Norwegian great-great-grandparents, Knut and Anne Strand, shown in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Knut and Anne Strand.

Knut and Anne came from Telemark, Norway, a region known for its striking landscapes, rich folk traditions, and as the birthplace of Telemark skiing. Decades after their departure, Telemark would gain international attention for its role in the Norwegian resistance to Nazi occupation, most notably through the sabotage of the heavy-water plant at Vemork. This episode was dramatized in the 1965 Hollywood film The Heroes of Telemark, starring Kirk Douglas, and the 2015 Norwegian miniseries The Heavy Water War. At the time Knut and Anne left, however, the region was marked by economic hardship. Knut was a tenant farmer with no land of his own, and Anne worked as a servant in a wealthy household. Life in Norway offered little prospect for upward mobility.

Hoping for a brighter future, Knut, Anne, and their one-year-old son Leof (my great-grandfather) boarded a sailing vessel bound for North America on April 4, 1861. After a weary ten-week journey, they arrived in Quebec and made their way to La Crosse, Wisconsin, eventually settling nearby in an area still known today as Norway Valley due to its influx of Norwegian immigrants.

Through the Homestead Act of 1862, many Nordic immigrants became landowners. In 1863, Knut secured a plot of fertile land in Tamarack, Wisconsin, and joined fellow recent Norwegian immigrants in establishing the Tamarack Norwegian Lutheran Church.Footnote 61 The idea of owning land – and the freedoms that came with it – had been a distant dream in Norway, but it quickly became their reality in the US.

During my youth, my family celebrated Norwegian traditions as we understood them. The Strand family reunion was a yearly summer gathering in Norway Valley, always preceded by a service in the church our ancestors had built. At Christmas we displayed Norwegian flags, and my grandparents, Gladys and Milton Strand (Leof’s son), prepared traditional dishes like lefse, sandbakelse, and lutefisk. Recounting the fortitude of Knut and Anne became a tradition of its own – one that instilled in me a lasting pride in my Norwegian heritage and a deep gratitude for the foundation my ancestors laid, which allowed me the opportunity to build a good life.

My fascination with the Nordics deepened in my late twenties as I began to consider their relevance in a modern context. After several years in Corporate America, I enrolled in the Evening–Weekend MBA program at the University of Minnesota. In my world economics course, I noticed that the Nordic countries consistently ranked among the world’s most prosperous economies – a stark contrast to their status among Europe’s poorest during my great-great-grandparents’ era. Intrigued by this rapid transformation, I asked my professor for an explanation. His answer – “oil” – felt insufficient. There had to be more to the story.

While Norway discovered significant offshore oil reserves in the late 1960s, petroleum wealth alone cannot explain the region’s broader pattern of shared prosperity. Oil discovery has produced the opposite effect in many countries – exacerbating inequality, corruption, and institutional decay. Venezuela offers a striking example. Despite its substantial oil reserves, the country experienced such damaging consequences that, in 1975, its oil minister, Pablo Pérez Alfonzo, famously called petroleum “the devil’s excrement,” blaming it for worsening corruption, waste, and inequality.Footnote 62

Norway – and the other Nordic countries – pursued a very different path. Modern Nordic societies exhibit low levels of corruption, efficient public services, and broadly shared prosperity – outcomes that reflect deep institutional strengths. Norway’s democratic management of its oil resources is one example. In 1990, the Norwegian government established the Sovereign Wealth Fund to ensure that oil revenues would benefit both present and future generations. As of January 2025, the fund was valued at $1.8 trillion – more than $300,000 per Norwegian citizen – and is managed with a strong emphasis on democratic oversight.Footnote 63

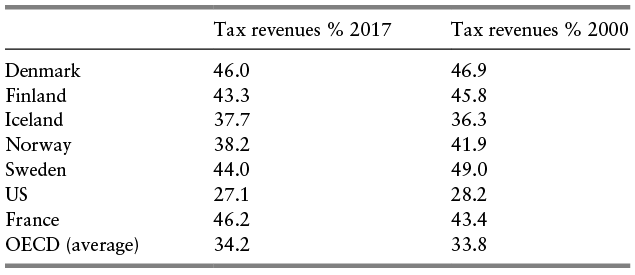

At the same time, I noticed something else: Nordic realities directly contradicted what I was being taught in my American MBA program. The Nordic countries challenged the prevailing assumption that social or environmental responsibility inevitably comes at an economic cost. According to the conventional economic wisdom presented in class, promoting social welfare or protecting the environment required sacrificing financial performance. Personal income tax rates were higher in the Nordics than in the US, especially when considering what was actually collected from the wealthiest citizens, yet their economies were thriving in ways that ran counter to what I had been taught. The Nordics, stood as living counterexamples. Their attention to societal well-being and environmental stewardship appeared to strengthen – rather than hinder – their economies. The question remained: how was this possible?

In my MBA coursework, the doctrine of “shareholder primacy” was presented as a core principle of American capitalism. Popularized by economist Milton Friedman, this view holds that business leaders are agents of shareholders and that their primary responsibility is to maximize profits. In his influential 1970 essay “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits,” Friedman argued that business leaders who take actions such as reducing discrimination or curbing pollution are “preaching pure and unadulterated socialism.”Footnote 64

Friedman warned that prioritizing any stakeholder beyond shareholders would threaten the foundation of a free society. Stakeholders include employees, customers, suppliers, communities, and shareholders themselves.Footnote 65 From Friedman’s perspective, attending to these broader interests risked undermining liberty.

Yet when we consider the Nordic experience and examine multiple dimensions of freedom – personal, civil, and economic liberties; freedom of the press; social mobility; democratic strength; and gender equality – Nordic countries often outrank the US (Chapter 7). By these measures, Nordic citizens are, in many ways, freer than their American counterparts, calling into question the foundational theory of American capitalism.

From the US to the Nordics

After finishing my American MBA in 2005, I was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship to Norway. My research aimed to understand the mechanisms behind the Nordic countries’ impressive economic, social, and environmental performances. I was primarily interested in understanding the business community’s influence on the Nordic achievements and the role of business leaders. Based at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim, I delved into a study of a case company from each of the four largest Nordic countries: Equinor in Norway, IKEA in Sweden, Novo Nordisk in Denmark, and Nokia in Finland.

As I engaged in my research, I was immediately struck by the fact that Nordic business leaders favored cooperation and consensus-building, a style that was fundamentally different from the authoritative, commander-style leadership I had experienced in corporate America. I saw concerted efforts to utilize democratic principles to organize and make decisions where business leaders actively sought critical voices, demonstrated humility, and openly acknowledged that they did not have the answers, thereby encouraging questions and discussion. I realized that employees at these Nordic companies had significant freedom to make decisions.

Moreover, I noticed a work culture that appeared to respect the boundaries of personal life and work. Statements like “I have to leave to pick up my kids” were expressed confidently rather than as an apology. I sensed a flatness to the corporate hierarchies, with less pronounced separation between the executive levels and the rest of the workforce.

In the Nordic corporate cultures I encountered, I sensed a noticeable shift in discourse. Conversations about stakeholders – extending beyond just shareholders – and sustainability issues were treated with importance. This was starkly different from my experiences in US corporations, where senior executives repeated the mantra of shareholder primacy and where suggesting an alternative was dismissed as a violation of fiduciary duty or as naive.

From the Nordics Back to the US

Returning to corporate America after my Fulbright year in the Nordics was jarring. The contrast in working environments was immediately palpable. I went from airy Nordic offices – where access to natural light is legally mandated – back to a cubicle in a large, windowless room. The ergonomic standing desk I had grown accustomed to was replaced by a fixed, rigid workstation. Communal lunches and fika breaks, which had cultivated a sense of connection, gave way to solitary meals eaten on a styrofoam plate at my desk. The boxes in the office of fresh apples, cucumbers, or carrots, depending on the season, were gone. My workdays were no longer bookended by walking, biking, or public transportation – but by car commutes and more hurried, less healthy meals. I could feel the toll on my energy and well-being.

Fortunately, an unexpected opportunity allowed me to reconnect with my growing Nordic interests. The University of Minnesota expressed interest in my proposal to launch a new course on sustainability in the Nordics. I was appointed adjunct faculty and developed the course for a cohort of twenty-five MBA students. In 2008, I embarked on a two-week journey across Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, visiting the people and organizations I had studied during my Fulbright year. The course was well received and became an annual fixture, allowing me to continue nurturing my Nordic fascination.Footnote 66

From the US Back to the Nordics

In 2009, newly married, my wife Sarah and I returned to the Nordic region to pursue our graduate studies. I began my doctoral work at Copenhagen Business School in Denmark, while continuing to lead annual MBA excursions to the Nordics for the University of Minnesota. As part of my PhD program, I taught a course on Nordic sustainability. My “outsider” perspective served me well – I could highlight aspects of Nordic societies that locals may have taken for granted but stood out as exceptional compared to my experiences in the US.

During this period, I also became concerned by what I observed in Nordic university bookstores: US business textbooks, steeped in the doctrine of shareholder primacy, increasingly dominated the shelves. This struck me as deeply ironic, given that Nordic management scholarship has long championed a stakeholder approach, and Nordic-based companies such as IKEA and Novo Nordisk are internationally recognized for their stakeholder orientation. I worried that the hegemony of US business literature risked eroding the very stakeholder ethos that had helped shape Nordic success.

Sumantra Ghoshal’s 2005 article “Bad Management Theories Are Destroying Good Management Practices,” captured my growing concern. Ghoshal argued that theories like Friedman’s prescription of shareholder primacy had come to dominate management education in the second half of the twentieth century, leading US corporations to prioritize maximizing shareholder value with limited regard for other stakeholders. He warned, “Unlike theories in the physical sciences, theories in the social sciences tend to be self-fulfilling.”Footnote 67 I feared that this dynamic could take hold in the Nordics, undermining a stakeholder model that had proven both durable and effective.Footnote 68

On a more personal note, the Nordic way of life captivated Sarah and me, prompting us to consider staying beyond our studies. I completed my PhD and was grateful for the opportunity to join Copenhagen Business School as an assistant professor.Footnote 69 We transitioned from being transient students to more permanent residents, immersing ourselves in Danish life.

From the Nordics Back to the US (Please)

In 2013, the joyous news of Sarah’s pregnancy prompted us to consider a temporary relocation. We wanted to return from Denmark to our longtime residence in Minneapolis, Minnesota, to be near family for the birth of our first child.

Denmark’s family-friendly policies enabled us to take a year of paid parental leave. During that time, I secured visiting scholar positions at the University of Minnesota and UC, Berkeley. I also received a travel grant from the Carlsberg Foundation, which supported my efforts to explore the creation of a research network among US universities focused on Nordic approaches to sustainability. The stage was set for a fulfilling year ahead.

However, we were quickly confronted with the harsh realities of American capitalism. In Nordic countries, healthcare is universally accessible and funded through taxes, a stark contrast to the US system, where access depends on the private market and is often tied to employer-sponsored “benefits.”

Without a US employer, Sarah and I had to navigate the labyrinth of private health insurance. While we were startled by the exorbitant out-of-pocket costs, the greatest shock came when Sarah was repeatedly denied coverage. We approached insurers like Minnesota’s UnitedHealth Group, who routinely labeled her pregnancy a “pre-existing condition” and used it as grounds for denial. Pregnancy, cancer, diabetes, high blood pressure, and mental health conditions were commonly cited by insurance companies to justify denying coverage. This rationale aligns with the doctrine of shareholder primacy, as these individuals were deemed unprofitable customers, and insurers prioritized profitability over access to care.

In 2013, the debate over the Affordable Care Act reached a fever pitch, with some politicians arguing that increased government involvement in healthcare was a slippery slope to Soviet socialism. Senator Tom Coburn, a physician turned legislator, warned that expanding state involvement in healthcare access would “Sovietize” the US system and erode Americans’ freedom.Footnote 70

For Sarah and me, however, our experience was starkly different. Our freedoms were diminished not by state intervention but by profit-driven insurance companies. We were left begging for someone to sell us health insurance, yet no company would.

Our situation underscored the need for an alternative, and the Nordic approach provided a compelling one. While my Nordic friends paid higher personal income taxes than I did in the US, their overall financial burden was lower when considering the cumulative costs of private insurance premiums and the unexpected out-of-pocket expenses that Sarah and I faced. Moreover, they were free from the stress and anxiety of navigating a complex healthcare system and never had to worry about being denied coverage due to pre-existing conditions.

In 2013, amid our healthcare struggles in the US, Denmark was named the World’s Happiest Country – a title routinely claimed by a Nordic nation in the annual World Happiness Report. Analysis of the World Happiness Report’s methodology reveals that this designation signifies more than mere subjective contentment; rather, it measures a complex set of structural factors including institutional trust, social support systems, and universal access to essential services.Footnote 71 When Finland later claimed the top spot, a Finnish citizen succinctly captured this sentiment: “‘Happiness’ is sometimes perceived as merely a smile on a face. However, I believe Nordic happiness is something more foundational – it’s about a high quality of life rooted in universal services, ensuring that people feel safe and included in society.”Footnote 72 The evidence suggests that World’s Happiest Country is better understood as World’s Least Insecure Society – though admittedly, the latter name lacks the same marketing appeal. Systemic security, fostered through robust social institutions and universal access to healthcare, education, and other essential services, represents a fundamental distinction between Nordic and American capitalism.

The Nordic healthcare system exemplifies their pragmatic capitalism: For-profit corporations and market mechanisms operate within a framework of state policies ensuring universal access. While American discourse often presents a false choice between total government control and pure market forces, the Nordic model demonstrates how combining public and private elements can achieve both universal coverage and economic efficiency.

The stark contrast between the two systems becomes undeniable when examining healthcare expenditures. In 2021, the US spent 18 percent of its GDP on healthcare – nearly double the approximately 10 percent typical in Nordic countries.Footnote 73 Yet every Nordic citizen has guaranteed access to healthcare, while in the US, millions remain uninsured, including over 4 million children.Footnote 74 These disparities expose the inefficiencies of the American system and suggest the immense emotional and societal toll of healthcare insecurity on millions of Americans.

Thankfully for Sarah and me, our return to the US in 2013 was enabled by a Nordic-inspired policy implemented in Minnesota in the mid 1970s.

Throughout the twentieth century, Minnesota lawmakers were notably influenced by Nordic policy developments, particularly those related to universal access to healthcare and education. In Scandinavians in the State House: How Nordic Immigrants Shaped Minnesota Politics, Swedish-born author Klas Bergman outlines the impact of modern Nordic policies on Minnesota. Swedish historian Sten Carlsson remarked, “Outside of the Nordic countries, no other part of the world has been so influenced by Scandinavian activities and ambitions as Minnesota.”Footnote 75 A prime example is the Minnesota Comprehensive Health Association (MCHA), established in 1976 to provide health insurance to those denied coverage due to pre-existing conditions. As the first and largest high-risk health insurance pool in the US, MCHA aspired to ensure universal access to healthcare, serving hundreds of thousands, including my wife Sarah and me.Footnote 76

Efforts to implement Nordic-like universal policies at the state level in the US often provoke accusations of socialism and warnings of the erosion of basic freedoms. The socialist allegations intensified in Minnesota in 2024 when Governor Tim Walz became a candidate for vice president, drawing national attention to the state’s policies. This attention coincided with Minnesota’s recent introduction of universal free school meals in 2023, a policy opponents labeled “pure socialism.”Footnote 77 Kevin Hassett, former Chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers under President Trump, went so far as to compare Minnesota’s policies to those of Venezuela, dramatically stating, “If you think of Venezuela … it’s exactly what you see in Minnesota.” This rhetoric suggests that establishing universal social programs inevitably lead to authoritarian socialist regimes like the Soviet Union or modern-day Venezuela.Footnote 78

However, equating Nordic-style universal policies with the failures of socialist authoritarianism overlooks historical and contemporary realities. Finland, which shared a 1,300-kilometer border with the former Soviet Union, has a profound firsthand understanding of the perils of Soviet socialism. Throughout the twentieth century, Finnish casualties in conflicts with Soviet forces were comparable to those the US suffered in the Korean and Vietnam Wars combined.

Despite Finland’s intense and prolonged conflicts with the Soviet Union, including the 1939 Soviet invasion, it enacted legislation in 1943 to ensure universal access to free school lunches funded by taxes – a clear indication that Finland did not regard such universal policies as steps toward authoritarian socialism.Footnote 79 Today, the merits of the Finnish approach are evident; Finland continues to uphold its universal school lunch programs while ranking high in global indices of democracy and freedom, effectively challenging the notion that universal social programs necessarily lead to authoritarianism. Finland’s ascent in global education rankings, from among the lowest in the mid twentieth century to consistently top or near-top positions, as evidenced by its performance in the Programme for International Student Assessment, is primarily attributed to effective educational policies.Footnote 80 Universal school lunches, in particular, ensure that all students are well-nourished and prepared to learn.Footnote 81

Contrary to assertions of a socialist dystopia, Finland is today described as a “capitalist paradise.”Footnote 82

Back Home in the US … but with a Continued Eye on the Nordics

In 2014, I embraced the opportunity to return permanently to the US, accepting the role of Executive Director of the Center for Responsible Business at UC, Berkeley Haas School of Business. I recognized that UC Berkeley provides a robust platform that can elevate the discourse and inquiry around Nordic capitalism.

Subsequently, we established the Nordic Center at the University of California, Berkeley, a campus-wide initiative where I serve as the founding Executive Director. At the Nordic Center, we routinely host events centered on Nordic policies and practices, including the Nordic Talks at Berkeley series. Our inaugural Nordic Talks event “Parental Leaves in the Nordics: Inspiration for California?” featured Robert Reich, former US Secretary of Labor and author of Saving Capitalism: For the Many, Not the Few.Footnote 83 Reich emphasized the practical merits of learning from the Nordics’ pragmatic approach. He stated:

The Nordics are capitalistic societies that have pragmatically figured out over the course of the past century where markets work well – and where they don’t. Paid parental leave does not belong in the domain of the markets. The Nordics learned this, and it is time for those of us in the US to learn this also.

I am increasingly of the belief that there are a number of other things the US may prosperously learn from the Nordic experiences.Footnote 84

From the Nordic Center at University of California Berkeley, we aim to illuminate discussions on Nordic capitalism, deriving lessons to improve American capitalism, and critically evaluating the Nordic model.

Nordics as Global Leaders

Nordic nations are increasingly stepping into the limelight to advocate for ambitious sustainability policies. Although they have long been acknowledged as leaders in sustainability, assuming such a public leadership role is relatively new for the Nordics. Typically characterized by humility, Nordic individuals – including leaders on the global stage – prioritize “walking the walk” over “talking the talk.” This characteristic is often linked to janteloven, a concept from Aksel Sandemose’s 1930s novel, En flyktning krysser sitt spor (A Fugitive Crosses His Tracks), set in a small Danish town. Originally a satirical critique of oppressive social norms, janteloven has evolved in modern discourse to symbolize modesty and social solidarity to engender a sense of ‘We’ in Nordic societies.

Recently, the Nordics have embraced a more vocal leadership role in the world, setting ambitious public sustainability goals and “talking the walk.”Footnote 85 For instance, Denmark’s 2019 climate law mandates a 70 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, targeting carbon neutrality by 2050. Similarly, Sweden established public targets to be completely free of fossil fuels by 2045, and Finland made history in 2022 by legally committing to carbon negativity.Footnote 86

In 2019, the Nordic Council of Ministers announced their goal for the Nordics to become “the most sustainable and integrated region” by 2030.Footnote 87 This bold public declaration represents a shift from the Nordics’ traditionally reserved stance to a more conspicuous role on the global stage, recognizing the broader vacuum of international leadership needed to address significant global challenges. This moment in history calls for global leadership, and the Nordics have chosen to step forward.

Parting Reflections

In just a few generations, the Nordic nations have risen from among Europe’s poorest to global leaders in societal well-being and sustainability. This transformation highlights their adherence to democratic principles, good governance, and a pragmatic focus on developing effective solutions over ideological rigidity.

The longtime Honorary Consul General of Sweden in San Francisco, Barbro Osher, dubbed me “Mr. Nordic” for my efforts to spotlight Nordic approaches in the US as a source of valuable lessons for contemporary challenges. This book aims to ignite widespread curiosity about Nordic capitalism and provide essential insights for realizing sustainable capitalism.

Though not without flaws, Nordic capitalism presents a powerful challenge to entrenched assumptions about how market economies must function. When Marquis Childs sparked American interest in Nordic capitalism with his 1936 work, Sweden: The Middle Way, he revealed an alternative path for market economies. Today, as we grapple with unprecedented social and environmental challenges and fundamental threats to our democratic institutions, the urgency to understand and adapt lessons from Nordic capitalism has intensified.

Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

The 1987 Brundtland Report (Our Common Future), led by Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland, established the globally recognized definition of sustainable development: “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” The commission synthesized diverse research streams to elevate sustainable development as a vital field of study. Brundtland is since dubbed the “Mother of Sustainable Development.”Footnote 1

Nordic leadership in sustainability thinking has a longstanding scientific tradition. Nearly a century before the Brundtland Report, Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius published the first academic article linking activities during the Industrial Revolution to climate change, “On the Influence of Carbonic Acid in the Air upon the Temperature of the Ground,” in 1896. His work laid the scientific foundations for understanding the greenhouse effect, demonstrating how atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) influences Earth’s surface temperature.Footnote 2 Arrhenius’s subsequent 1908 book, Worlds in the Making, expanded on these ideas, pioneering the concept that human industrial activities, specifically the burning of fossil fuels, could lead to long-term climate changes. This early Nordic contribution to climate science set crucial groundwork for later understanding of planetary boundaries in relation to climate change.Footnote 3

Sustainable Development

I first encountered the definition of sustainable development during an elective course in my American MBA program in the early 2000s. It resonated with me as a timeless and universal goal, offering a more profound and overarching purpose than the narrow focus on shareholder profit maximization emphasized elsewhere in my MBA program and prevalent in Corporate America.

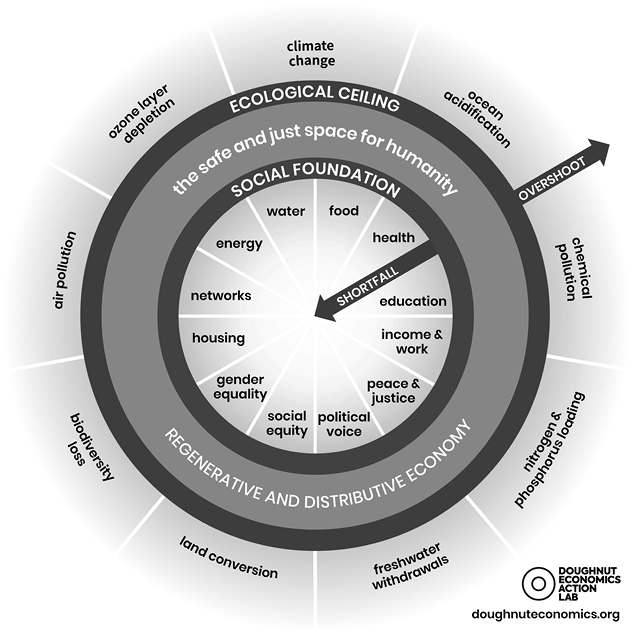

Sustainable development represents a significant shift from the traditional economic models prevalent throughout the twentieth century, which focused almost exclusively on economic growth. Sustainable development recognizes the interconnectedness of economic development with pressing social and environmental challenges, including poverty, hunger, increasing inequalities, climate change, and the eradication of biodiversity. Addressing these intrinsically linked challenges demands a holistic, systems-based approach.

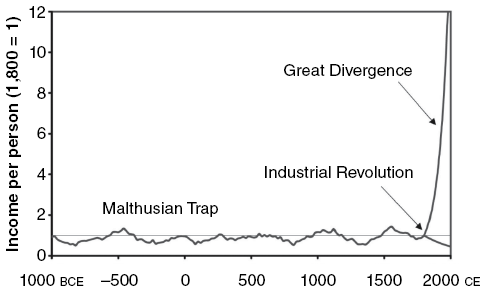

The period from the late eighteenth to the nineteenth century is characterized by profound industrialization and innovation that reshaped societies at an unparalleled pace and profoundly changed humankind’s relationship with the Earth. Beginning in the 1760s, the epicenter of the Industrial Revolution was England. It soon reverberated throughout Europe, the young US, and beyond, radically altering human beings’ everyday lives during the nineteenth century and after that. Characterized by a shift from piecemeal production by hand to mass production by machines in ever-growing factories, the Industrial Revolution brought about unparalleled advances in efficiency and accelerated economic development.

Yet as is often the case with revolutionary transformations, the advances of the Industrial Revolution came with unintended consequences. The industrial era heralded widespread environmental degradation. For the first time, humankind affected the Earth’s geology and ecosystems. As the twentieth century progressed, the need for a more holistic approach to development that integrated environmental, social, and economic dimensions became increasingly apparent. The concept of sustainable development was born of this need.

Systems Thinking: The Earth as a System

Sustainable development emphasizes the necessity of systems thinking.Footnote 4 The Brundtland Report highlighted that economic development is intertwined with environmental sustainability, where poverty and inequality contribute to and are exacerbated by environmental degradation.Footnote 5 It highlights the interconnectivity of critical issues, including population, food security, species loss, energy, industry, and urban development, advocating for integrated, holistic solutions.

The Brundtland Report built upon seminal works, such as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and Donella Meadows and colleagues’ The Limits to Growth, which warned that human activity associated with industrialization would exceed the Earth’s carrying capacity.Footnote 6

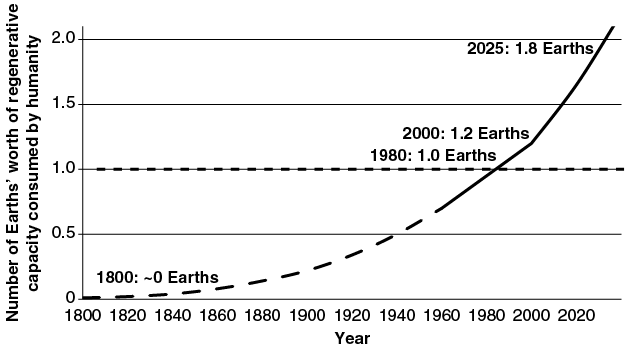

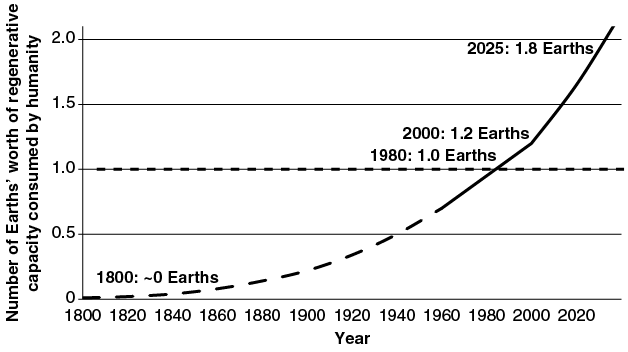

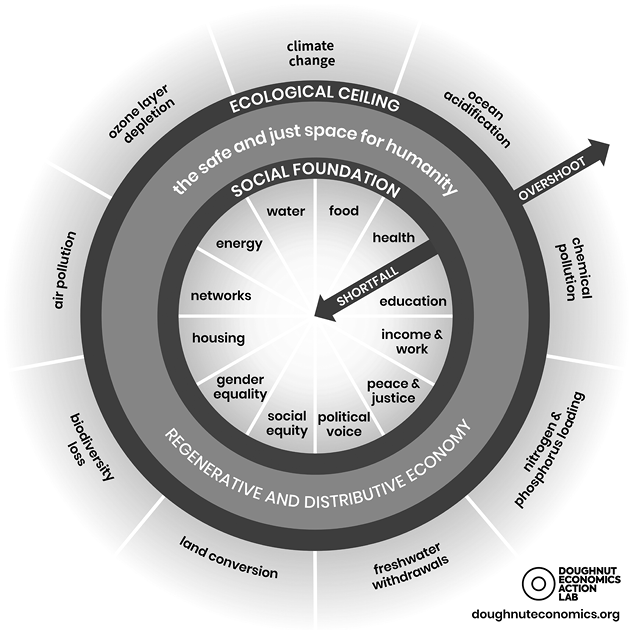

Since the early 1980s, humanity has consumed resources faster than the Earth can regenerate them – driving natural resource depletion, rising greenhouse gas emissions, and biodiversity loss. The 2004 Limits to Growth thirty-year update illustrated this starkly. Using data from Mathis Wackernagel and colleagues, published in “Tracking the Ecological Overshoot of the Human Economy,” it featured a striking graph showing the ecological footprint rising from just over 0.6 Earths’ worth of annual regenerative capacity in 1960 to 1.2 Earths’ worth by 2000.Footnote 7

As depicted in Figure 2.1 – which offers an expanded view of the graph from the Limits to Growth update – humanity’s impact was negligible at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution era but has since surged. By 2025, it reached an estimated 1.8 Earths, corresponding to Earth Overshoot Day falling on July 24 – the symbolic date of the year when humanity has already consumed the Earth’s full annual regenerative capacity.Footnote 8

Figure 2.1 Number of Earths needed to support human activity.

Patterns of overconsumption are deeply unequal worldwide. US citizens rank among the highest per capita consumers globally – if everyone consumed at the level of the average American, more than five Earths’ worth of regenerative capacity would be required. All of the world’s wealthiest nations, including all OECD and Nordic nations, exceed sustainable consumption levels.Footnote 9

Overconsumption is closely tied to wealth. The wealthiest 1 percent have a carbon footprint double that of the poorest 50 percent combined.Footnote 10 Alarmingly, research shows that the wealthiest individuals often view their consumption as fair. This perception gap is especially concerning given the disproportionate influence the wealthiest individuals have over global policy decisions.Footnote 11 Furthermore, as lower-income nations continue to develop, their consumption levels are also rising, further intensifying pressure on the planet’s finite resources.

Addressing the global crisis of overconsumption necessitates a fundamental reassessment of our production and consumption models. Consumption levels have drastically altered the planet, and many scientists now refer to the present as the Anthropocene epoch, defined by the dominant impact of human activity on Earth’s geological history (from anthropo, for man, and cene, for new).Footnote 12 Before this was the Holocene epoch, which began 11,700 years ago after the last ice age, offering stable climates that allowed human civilization to flourish. Preceding the Holocene was the Pleistocene epoch from about 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago. The Pleistocene epoch posed significant challenges for early humans, with repeated ice ages and harsh conditions that made survival difficult due to extreme cold, food scarcity, and unstable environments. While the official designation of the current epoch is debated, it is evident that humanity’s ability to alter Earth’s systems now significantly poses severe risks to human survival and well-being.

Earth: Humanity’s Endowment

Earth is humanity’s ultimate endowment – an irreplaceable asset that sustains all life and human civilization. Like any precious endowment, it is passed from generation to generation, with each inheritor serving as both beneficiary and trustee.

When a financial endowment is responsibly stewarded, it regenerates a stream of financial resources in perpetuity from which current and future generations benefit. Responsible stewardship entails withdrawing only resources generated from interest and not touching the principal of the asset.

Consider, for example, an endowment of $100 million. At a 4 percent interest rate, commonly accepted in financial management as a sustainable rate minimizing the risk of depleting the principal, such an endowment can regenerate $4 million annually in perpetuity. By withdrawing only the interest generated, the principal is preserved over the long term while providing a reliable revenue stream from interest to live on for each generation of benefactors. However, if a beneficiary extracts more than the $4 million annually generated through interest, the principal is eroded, and the asset is impaired. As a result, the endowment’s regenerative capacity is diminished. For example, imagine a beneficiary extracting $20 million from the $100 million endowment in one year. That $20 million would be $4 million from interest and $16 million from the principal. The value of the endowment is thereby reduced to $84 million.

While the present beneficiary may benefit from their heightened withdrawals by taking from the endowment’s principal, they are effectively stealing from all future beneficiaries – an $84 million endowment only regenerates $3 million annually in interest.

This endowment metaphor parallels environmental scientists’ conceptualization of Earth’s resources: as “stocks” (like an endowment’s principal) and “flows” (like the interest generated). All existing trees on Earth represent a stock, while the annual growth of new trees represents a flow. Similarly, healthy soil is a critical stock that can take centuries to build, generating annual flows of food and biomass. Biodiversity represents another crucial stock, with flows that include vital ecosystem services and medical innovations. More than half of cancer drugs have been discovered from natural sources, with compounds from plants, microorganisms, and marine life providing breakthrough therapies.Footnote 13 While advances in artificial intelligence enhance our ability to identify promising compounds in nature, the accelerating loss of biodiversity through habitat destruction and climate change permanently eliminates potential discoveries that could cure humanity’s most devastating diseases. These natural stocks – our forests, soils, freshwater bodies, oceans, and biodiversity – create vital flows that sustain life: carbon sequestration, food production, air and water purification, and life-saving medicines.

Herman Daly, a pioneering ecological economist, emphasized this distinction between stocks and flows as fundamental to understanding sustainability.Footnote 14 Just as an endowment trustee must distinguish between drawing down principal and living off generated interest, environmental scientists differentiate between depleting Earth’s stocks and sustainably harvesting its flows. When stocks are responsibly stewarded, these flows continue indefinitely. However, every year that humankind consumes more than Earth regenerates, its stocks are depleted and its regenerative capacity diminished.

The economic costs of failing to act as responsible trustees of our planetary endowment are increasingly conspicuous. According to a 2024 study published in Nature, climate change impacts will reduce global economic income by 19 percent within the next twenty-six years. Annual damages are estimated at $38 trillion in 2049 and grow with every passing year of increasing atmospheric CO2 ppm levels.Footnote 15 Harvard economist Adrien Bilal asserts, “By the end of the century, people may well be 50 percent poorer than they would’ve been if it wasn’t for climate change,”Footnote 16 based on his working paper with Diego Känzig, an economist at Northwestern University.Footnote 17

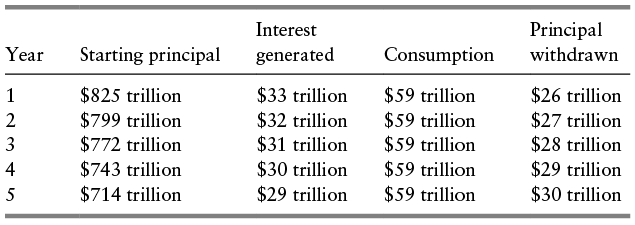

To further illustrate the Earth as an endowment metaphor through a numerical example, we can draw upon the 1997 study published in Nature. Robert Costanza and colleagues estimated the total value of ecosystem services provided by Earth’s biomes – effectively Earth’s annual “interest generated” – at $33 trillion, nearly double the global gross national product (GNP) of $18 trillion at that time. This valuation underscored the immense economic importance of natural ecosystems and the devastating costs of their degradation.Footnote 18

Using Costanza et al.’s valuation of Earth’s annual ecosystem services as our starting point, we can further develop the Earth endowment metaphor to illustrate the consequences of overconsumption. If we treat Earth’s annual ecosystem services of $33 trillion as “interest” generated by our planetary endowment and apply a standard endowment interest rate of 4 percent, we arrive at an Earth “principal” value of $825 trillion ($33 trillion ÷ 0.04). While this arbitrary calculation vastly simplifies Earth’s complex systems and their varying regeneration rates, it will illustrate how overconsumption compounds over time to erode Earth’s regenerative capacity.

Humankind currently consumes resources at about 1.8 times Earth’s annual regenerative capacity. In the endowment metaphor, this equates to withdrawing 7.2% annually (4% × 1.8). While $33 trillion could be sustainably withdrawn each year (at 4%), humankind currently withdraws $59 trillion. The excess $26 trillion comes directly from Earth’s principal Table 2.1.

| Year | Starting principal | Interest generated | Consumption | Principal withdrawn |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $825 trillion | $33 trillion | $59 trillion | $26 trillion |

| 2 | $799 trillion | $32 trillion | $59 trillion | $27 trillion |

| 3 | $772 trillion | $31 trillion | $59 trillion | $28 trillion |

| 4 | $743 trillion | $30 trillion | $59 trillion | $29 trillion |

| 5 | $714 trillion | $29 trillion | $59 trillion | $30 trillion |

As withdrawals routinely exceed interest generated, Earth’s principal is continually drawn down and its regenerative capacity further erodes – visible in the declining annual interest generated. While alarming, this example actually understates the challenge, as global consumption is accelerating beyond the current 1.8 rate. On current trajectories, humanity could be consuming the equivalent of two Earths’ annual regenerative capacity by 2030 or soon thereafter, with no slowdown in sight.

Moreover, while the endowment metaphor is useful for illustration, it has a critical limitation: It assumes linearity. Earth’s systems, in contrast, contain tipping points – critical thresholds beyond which changes become both dramatic and irreversible, with potentially devastating consequences for human civilization. These tipping points represent a fundamental difference between financial and ecological systems: While a depleted financial endowment might be rebuilt over time, a crossed ecological tipping point permanently alters Earth’s life-supporting capacity.

Consider three critical tipping-point examples: The Greenland Ice Sheet may irreversibly melt if warming exceeds 1.5–2°C; the Amazon Rainforest could transform from carbon sink to carbon source, shifting to dry savannah with continued deforestation; and the Atlantic Ocean circulation may collapse, fundamentally altering global climate patterns.Footnote 19 These potential system changes underscore the urgency of correcting humanity’s consumption to levels within planetary boundaries.

While subject to debate, many scientists assert Earth is experiencing the “sixth mass extinction,” representing another critical tipping point in Earth’s systems. Unlike previous mass extinctions caused by natural events like asteroid impacts and volcanic eruptions, this extinction is unique – for the first time, Earth’s inhabitants are driving their own extinction crisis. Species are now disappearing at rates up to 1,000 times greater than the natural background extinction rate. Each lost species weakens the resilience of Earth’s interconnected ecosystems, further compromising its capacity to support human civilization.Footnote 20

Each of us is a trustee of humanity’s sole life-supporting endowment: Earth. While we all share responsibility, some individuals, institutions, and nations wield far greater influence over the fate of humanity’s endowment. How effectively we govern ourselves – particularly those with outsized influence over Earth’s systems – will determine whether future generations judge us as responsible trustees of their inheritance … or not.

Nordic Sustainability Contributions

The Nordic region has pioneered numerous sustainability innovations, from philosophical frameworks to practical policies. The Brundtland Report sparked global efforts to tackle sustainable development challenges. The following examples showcase several more key contributions with Nordic connections that have had significant global influence.

Environmental Protection Agencies

Recognizing the interconnected challenges of economic growth and environmental sustainability, in the 1960s and early 1970s, Nordic nations established some of the world’s first national environmental protection agencies within their respective governments. In 1967, Sweden created the world’s first national environmental protection agency (Statens Naturvårdsverket / Nature Protection Agency), and by the early 1970s, Denmark, Finland, and Norway had followed suit. These agencies were tasked with developing and enforcing stringent environmental regulations, monitoring pollution levels, and promoting public awareness about the ecological impacts of industrialization. The Nordic agencies demonstrated global leadership by actively participating in international environmental dialogues and treaties, notably through initiatives like the 1974 Nordic Environmental Protection Convention that resulted in the first legally binding international convention addressing transboundary pollution.Footnote 21

Deep Ecology