On 6 June 1582, the Spanish corregidor in Cusco, Peru, ordered all free Afro-Peruvians (negros y negras y mulatos y mulatas) living in the city to appear before a public notary, “so that it could be seen and understood how they live and serve, and [so that] those who do not have professions [oficios] are assigned masters [amos] according to the law, and so that they will cease the many inconveniences and damages that come from how they carry on and live.”Footnote 1 Failure to comply within ten days would be punished severely, with a public beating of one hundred lashes and exile from the city. The town crier read the proclamation publicly on 12 June and again on 18 June, and the first free Afro-Peruvian people appeared for registration on 25 June. Despite the penalties threatened for not registering promptly, the men and women who assembled took more than a month to do so, arriving in small numbers for multiple registration sessions.Footnote 2 Three individuals were not recorded until 13 October. By that time, the Spanish notary had compiled the names of almost one hundred and fifty people, as well as the information that some provided regarding their occupations, places of residence, and connections to powerful Spaniards. The registry was never successfully used to implement the intended resettlement of men and women that the corregidor identified as threats to municipal order.

This article considers how Afro-Peruvians in early colonial Cusco engaged with the 1582 registration proceedings, as Spaniards continued to articulate a colonial social order grounded in coerced and racialized labor. Details in the 1582 registry vary from person to person, reflecting differences in individual identities and self-positioning, which influenced how registrants volunteered or withheld personal information. We argue that the registry demonstrates strategic efforts by free Afro-Peruvian people to define and maintain their socio-legal standing.Footnote 3 The Cusco case offers a highland complement to the well-documented literature addressing the articulation of Black identities in early colonial Lima.Footnote 4 The 1582 registry was an early and demonstrative part of a drawn-out process whereby colonial elites sought to reformulate Iberian social practices through new institutions and legal practices that favored their interests over others.Footnote 5 Placed into historical context, this document highlights the social complexities and protracted negotiations of colonization, illustrating how free Afro-Peruvians strategically engaged with attempts to constrain their autonomy. Their actions responded to discourses and social practices developing in the Andes since the 1530s, and they contributed to the failures of the early colonial race project, richly documented in the scholarship on the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.Footnote 6 The 1582 registry highlights ambiguities and contradictions in the evolving system of dominance, as well as the persistent efforts of individual Afro-Peruvians to navigate and best position themselves within it.

Coerced Labor and Anti-Black Discrimination in Early Colonial Peru

Because the 1582 registry indicates ways that a person’s parentage, economic standing, and gender could be used to coerce uncompensated or low-wage work, an intersectional review of labor exploitation in early colonial Peru offers important historical context. Free Afro-Peruvian people faced unfair practices that varied based on race, class, and gender, as well as Spanish municipal and viceregal ordinances and royal decrees that discriminated based on race.Footnote 7

Enslavement and Freedom

Uncompensated labor was fundamental to the Spanish colonization of Peru. While the organization of Andean populations into encomiendas was the foundation of the colonial economy, the conquistadores also brought significant numbers of enslaved men and women from Central America and Africa with them.Footnote 8 By 1534, the crown granted licenses to import hundreds of “Black slaves” (esclavos negros) to Peru, the majority of them men, for mining and other labor. This growing population was initially outnumbered by other enslaved laborers, including Indigenous people taken in war, “ransomed” from bondage (esclavos de rescate), or attached to Spanish service under the rubric of existing local practices (e.g., naborías, yanaconas). The leading men of the Pizarro faction augmented their huge grants of tributary Indigenous labor by enslaving people from diverse backgrounds.Footnote 9

The growing Spanish population in Peru demanded free or low-wage labor, which encomienda grants provided only to a select few. By 1550, more than two thousand Spaniards lived in colonial settlements, with fewer than four hundred possessing encomiendas. Footnote 10 Twenty years later, encomenderos comprised just five percent of the nearly 5000 Spanish men residing permanently in the audiencia of Los Reyes.Footnote 11 By then, declines in the tributary population had prompted royal attempts to restrict encomienda services to specified annual tributes (tasas), prohibiting encomenderos from coercing uncompensated services, renting tributary laborers, or using encomienda labor in certain kinds of work.Footnote 12 For example, a 1541 real provisión noted that Native Andeans were free subjects, not slaves, and that as such they should not be forced to do mining labor.Footnote 13 Such restrictions, which Spaniards resisted fiercely, increased demands for enslaved and low-wage laborers in mining and other ventures, and in 1557, Peru’s viceroy recommended that three thousand Afro-Peruvian men and women be sent to gold mines on the Amazonian slope.Footnote 14

As the licit access to uncompensated Indigenous labor narrowed, the crown also attempted to restrict which groups could be brought to Peru as slaves. Early prohibitions focused on the Indigenous slave trade, with royal cédulas addressing trafficking from Nicaragua (1536), Guatemala (1549), and Brazil (1550).Footnote 15 Contemporaneous documents banned the continued practice of esclavitud de rescate (1538) and declared that Indigenous naborías and yanaconas were free subjects (in 1540 and 1541, respectively).Footnote 16 Indigenous enslavement continued despite these prohibitions, but it diminished over time, leading to a stronger association of unfree labor in mining and commodity agriculture using newly-imported laborers from Africa (negros bozales).Footnote 17

The persistent demand for significant numbers of enslaved Afro-Peruvians reflects not only the increasing competition for labor among colonial elites, but also the achievements of many Afro-Peruvian people in obtaining their freedom.Footnote 18 Many people who were brought in bondage escaped to areas beyond Spanish control, leading to a growing population of self-liberated Black people (negros cimarrones) in rural areas.Footnote 19 Spanish officials attempted unsuccessfully to prevent flight and to capture negros cimarrones and return them to captivity. In Lima and other Spanish settlements, a new population of freedmen and freedwomen (negros horros) increased through the well-established Iberian practice of manumission, a legally-recognized avenue for freedom.Footnote 20 People with valuable artisan, business, and technical skills earned the capital needed to purchase their freedom, and many established a trade and acquired real estate and other personal property. By the mid-1500s, there was a substantial and growing number of Afro-Peruvian people who were not esclavos negros, a free population that included individuals wealthy enough to wear fine silk garments and gold and silver jewelry. Their numbers included a new generation of people of mixed-heritage called by a variety of new terms—mestizo, mulato, zambaigo—whose parentage presented uncertain legal implications.Footnote 21

Lower-Class Work

As Spanish men sought access to unfree labor through encomienda grants and enslavement, the most wealthy and powerful also embraced a class-focused rhetoric about settling “vagabonds” (vagabundos) and using coerced labor to prevent the mortal sin of idleness (ociosidad). In Iberia, such themes were already associated with escaped slaves, bandits, ethnic minorities, and the transient poor.Footnote 22 The encomenderos in Peru—most of whom were men of humble origins—quickly came to denounce the disruptive presence of the “wrong kind” of Spaniards. As people entered the Andes seeking wealth and opportunity, the colonial elite portrayed the new arrivals as a dangerous element that harmed tributary populations, committed crimes, and fueled rebellions.Footnote 23 Of particular concern were men who were not permanent residents in colonial towns, especially those lacking a means of support, such as an encomienda or trade (oficio mecánico).

In 1549, Pedro de la Gasca complained that there were more “vagabonds” in Peru than in Spain, France, and Italy combined, “because over there [i.e., Europe], everyone typically has an oficio through which they live, and if not … they serve those who will feed them; and here, after they arrive, they want to be gentlemen and to live without oficio and without serving.”Footnote 24 A real cédula ordered that Spanish vagrants and idlers (vagabundos y holgazanes) be settled with masters (amos), occupied in skilled labor (oficios), or expelled from Peru.Footnote 25 Many poor Spaniards were sent to prisons in Panama, but the Marqúes de Cañete warned in 1556 that more than three thousand men remained in Peru seeking royal favors, “all of them very well armed.”Footnote 26 His successor complained that vagabundos deported to Spain often managed to return, “with worse intentions than before,” and that there were still “more than 2,500 men who have no other thing to do than to eat in other people’s houses and to lounge about without having an oficio and not wishing to learn one.”Footnote 27 In 1568, Philip II reiterated that “vagabonds and gypsies” were a problem in the Americas, and he ordered his officials to expel them.Footnote 28

By then, rhetoric about an unsettled and jobless poor had diffused into discussions about other populations that Spaniards struggled to fix in place as a reliable source of low-cost labor.Footnote 29 Advocates of Spanish administrative intensification argued that scattered Indigenous populations needed to be resettled, closely supervised, and kept busy with hard labor to ensure their moral development as good Christians. They began to describe Indigenous individuals who left tributary communities as vagabundos or holgazanes. Footnote 30 Free Afro-Peruvian people also came to be portrayed in this way, although their mobility and freedom from regulation were characterized as harmful to others, rather than to themselves.Footnote 31 In 1567, the oidor Juan de Matienzo proposed the detailed registration of Afro-Peruvians in all Spanish settlements to remedy their supposed idleness: “there should be a great account made by the justice to record all of the mestizos, mulatos, and negros horros that might be in it, and the ages they have, and those that are married and have some property or means; and for those that do not, they should be placed with amos or to learn mechanical offices [officios mecanicos] so that they do not go about lost or lazy. …”Footnote 32 The class-based distinction between skilled workers (oficiales) and those who needed to be settled and assigned in service to masters became entwined with racially-motivated efforts to constrain Black socio-legal standing and mobility in Peru.Footnote 33

As the sovereign of both the “Spanish” and “Indian” republics, Philip II reworked these arguments around his own interests in raising revenue. A real cédula stated in 1574 that free Blacks in the Americas owed their liberty, economic prosperity, and safety to his governance, and should pay tribute: “Having come over as slaves [and] finding themselves free—and Blacks in their native lands having the custom of paying tribute in great quantity—we have the just right that they should pay us. …”Footnote 34 Initially portraying negros as foreigners, rather than subjects within the Spanish Republic, the king soon adapted his approach to the prevailing discourse on vagrancy, noting that tribute collection had proved difficult, because they were “a people that has no settlement or fixed location.” Claiming, in effect, that free people of African heritage were vagabonds, Philip ordered them to settle permanently with amos who would ensure that their royal tribute was paid.Footnote 35

Reproductive Labor and Domestic Bondage

Early colonial policies related to “vagabonds” primarily targeted low-status men who lacked a trade, a class-based antagonism linked to the male exploitation of women’s labor.Footnote 36 The conquistadores brought enslaved women from Africa and Central America with them to the Andes, where they also took Indigenous women into enmeshed and coercive relationships, involving skilled and domestic labor and sexual violence.Footnote 37 A 1541 royal cédula denounced Spaniards of all statuses in Peru for murdering Indigenous men “for the sole purpose of robbing them and taking their wives and daughters against their will”; another denounced the many Spaniards “who keep in their houses a quantity of indias to carry out their wicked desires with them.”Footnote 38 One report from Quito claimed that the early conquistadores frequently took twenty to thirty Indigenous girls from their families to serve in their households.Footnote 39

Although records are scarce, wealthy encomenderos often kept large numbers of women as servants and slaves, whereas newly arrived Spaniards and men lacking encomiendas had fewer opportunities and less social support for doing so. Indigenous elite men were also known to keep secondary wives and to sequester unmarried women and widows, who produced food and cloth for them.Footnote 40 Some wealthy Afro-Peruvians also kept Indigenous women in this manner. In 1551, a royal cédula prohibited Afro-Peruvians of all statuses from being served by Indigenous slaves and servants, making special reference to the mistreatment of women kept as mancebas (concubines).Footnote 41

The decline in Indigenous enslavement and efforts to reform the worst excesses of the encomienda system contributed to a reduction of unfree female labor in Spanish households. Many women were able to establish more autonomous relations in households where they were made to labor, attaining the status of free servants (criadas), though still navigating and constrained by entangled and unequal labor relationships.Footnote 42 Uncompensated women’s domestic labor received limited official attention, most of which was indirect and couched in church concerns about moral problems of cohabitation and sexual relations outside of marriage. Although there were few European women in the Andes in the early years, the crown ordered encomenderos to marry, which ironically legitimized keeping enslaved and servant women, since such practices were considered proper for the support of a wealthy Iberian household. A 1541 royal cédula ordered that “no Spaniard should have in his house a suspicious india, nor one who is pregnant or has just given birth, except those that might be appropriate specifically for their kitchen and regular service.”Footnote 43 Marriage also promoted permanent settlement and moral oversight by parish priests, and the Second Lima Council (1567–1568) ordered that priests not preside over the marriages of Spaniards without a fixed residence.Footnote 44

The moral imperative to marry extended to other populations in the Andes as royal and church officials denounced cohabitation and increasingly promoted within-group marriages.Footnote 45 Whereas Spaniards viewed their own marriages as a justification for maintaining uncompensated and low-wage domestic labor, many treated the marriages of others as an impediment to such access. For example, in 1553, a royal cédula denounced the “open concubinage” practiced in the Black population living in the towns, mines, and plantations of Guatemala, which was attributed to the resistance of Spaniards who feared that marriage would lead to emancipation for enslaved people (despite royal declarations to the contrary).Footnote 46 A 1569 report from Quito stated that Spaniards who kept unmarried Indigenous women as domestic servants prevented them from marrying so that their husbands would not remove them, “which is a manner of enslavement.”Footnote 47

Racial Injustice in Peru’s Two Republics

The crown viewed Black freedom as a threat, and a 1526 royal cédula prohibited Afro-Spaniards (negros ladinos) from traveling to the Americas without special licenses, claiming that they refused to serve Spaniards and organized the resistance and flight of those in bondage.Footnote 48 After colonial officials in Mexico prevented a Black uprising in 1537, new ordinances were established that attempted to reduce the threat of future actions.Footnote 49 Peru’s small Spanish population responded to Black liberation, social advancement, and diversification with similar rhetoric and race-specific ordinances.Footnote 50 Spaniards with rural encomiendas, mines, plantations, and herding stations asserted that self-liberated and enslaved Afro-Peruvians threatened their lives and property. They denounced negros cimarrones as violent bandits who preyed on travelers and remote settlements, offering rewards for their recapture.Footnote 51 They also complained that enslaved Black men and women mistreated Native populations when they were permitted to reside in rural areas.Footnote 52 Allegations of Black abuse of Indian subjects proved influential at court, where self-interested policy-making was often expressed through a moral rhetoric about the protection and well-being of “Indians.” In 1541, Charles V decreed that enslaved Afro-Peruvians should have no interactions with Indigenous villages, as they allegedly promoted drunkenness, vice, and flight from tributary service.Footnote 53

Although Cusco’s early Cabildo and notary records are fragmentary, surviving documents indicate municipal attempts to limit the freedom of the city’s Afro-Peruvian population. In 1545, the Cabildo announced a fine of three pesos for Afro-Peruvian men and women found in the Indigenous barter market, a penalty that was increased to five pesos in 1550.Footnote 54 In 1548, it was prohibited for any free Afro-Peruvian to have an enslaved Afro-Peruvian man or woman in their home because of the supposed “disorder” that existed among the free population.Footnote 55 Despite these attempted restrictions, in 1560, the Cabildo swore in a free Black man named Tomás as the alguacil for the Afro-Peruvian men and women living in the city.Footnote 56 The municipal recognition of a legal official from the Black community speaks to the possibility of organizing a self-governing república de negros within Spanish cities, although the Cabildo still argued that Afro-Peruvians should not be allowed into the Amazonian lowlands within Cusco’s rural jurisdiction.Footnote 57

That same year, new royal ordinances proclaimed a very different approach to governing Afro-Peruvians in Lima.Footnote 58 The laws announced several restrictions that applied specifically to “Blacks,” regardless of status. Free and enslaved people were required to reside with a Spanish master (amo), prohibited from bearing arms, and subject to a nightly curfew. The application of these ordinances varied based on status—free Afro-Peruvians were attached to their amo by service contracts (asientos), had greater economic autonomy, and faced less severe punishments than enslaved Afro-Peruvians for violating the same rules. The Lima ordinances addressed negros cimarrones indirectly, ordering Spaniards to register enslaved individuals who escaped and announcing penalties for anyone supporting self-emancipation, regardless of racial identity or status. They also permitted Indigenous people in rural communities to use violence in defending themselves against negros cimarrones and offered them rewards for the capture and return of those who fled bondage.

The extent to which the 1560 ordinances were enforced in Lima is uncertain, but Peru’s viceroy wrote in 1563 that a “huge number” (cantidad grandissima) of free Afro-Peruvian homeowners continued to aid those escaping enslavement, suggesting that few had relocated to the houses of Spaniards.Footnote 59 His attempt to introduce some of the Lima ordinances to Charcas failed when Black leaders there convinced officials not to implement them.Footnote 60 Promoting a stereotype of Black violence and criminality, the viceroy wrote fearfully of the need to control a population that outnumbered “White” colonists. Such fears extended to the growing mixed-race population in Peru, which also faced new legal restrictions at this time.Footnote 61 The head of Lima’s audiencia real wrote in 1565 that “there are so many negros and mulatos and mestizos in this land that if they were to work together, it would not be possible for the Spaniards who are here to stand against them.”Footnote 62

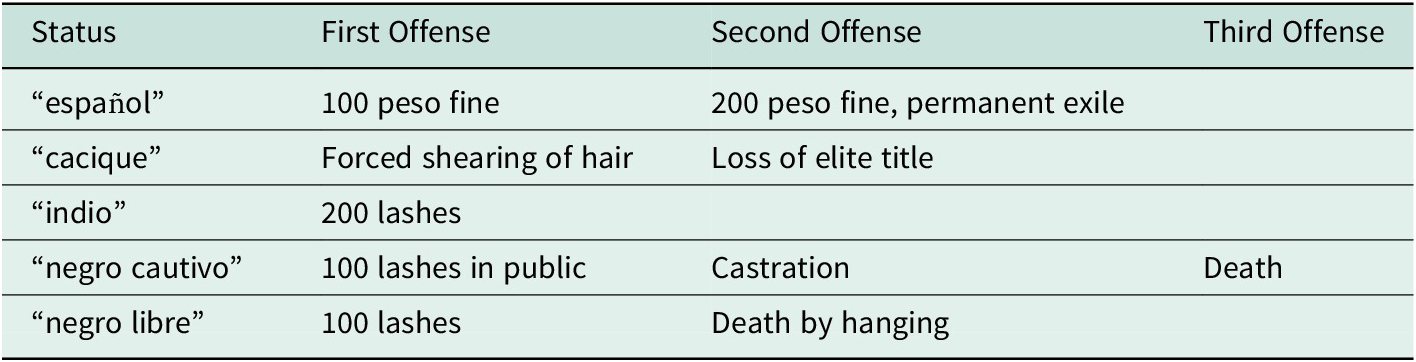

Legal efforts to ensure Spanish access to uncompensated and low-wage labor recognized the diversity of the Peruvian populace by designating unequal punishments for those violating new statutes. Men were the unmarked subjects of punishment, although non-Spanish women (indias, negras) are sometimes mentioned as subject to the same punishment as men of their racial group. Some ordinances specified status-dependent punishments for Spaniards (encomenderos, residents, vagabundos), Native Andeans (caciques, indios), and Afro-Peruvians (horros, cimarrones, esclavos). Rules that applied to all populations often threatened Afro-Peruvians with significantly harsher sanctions. For example, Lima’s 1560 Black ordinances specified different punishments for men who helped enslaved Afro-Peruvians to escape, with mutilation and death reserved for Afro-Peruvians (Table 1).

Table 1. Punishments for Assisting Those Escaping Enslavement

Source: Konetzke Reference Konetzke1953, vol I: 387.

The grim distinctions made for men of different racial and social statuses reinforce the fact that decades of Spanish ad hoc lawmaking attempted to establish two republics in Peru: a república de españoles grounded in municipal practices that were distinct from those of Spain, and a república de indios that governed rural Indigenous populations through their caciques, Spanish encomenderos, and priests. Free Afro-Peruvians and mixed-race people were treated as a growing “nuisance” that needed to be kept out of the Indigenous republic, and constrained from exercising the privileges of leading citizens in the Spanish one.Footnote 63 For example, in 1551, a royal decree banned the entire Black population of Lima—“black (negro) or dark brown-skinned (loro) or North African (berberisco), enslaved or free”—from carrying arms, a common practice among Afro-Peruvian veterans who fought for their freedom in the Spanish civil wars.Footnote 64 Skilled Spanish workers viewed free Afro-Peruvian artisans as unwelcome competition, and Lima’s blacksmiths solicited a ban on Black-operated shops in 1552, claiming that they would make illicit keys.Footnote 65 Sumptuary rules issued in 1554 prohibited wealthy Afro-Peruvians, especially women, from wearing silk, gold, and silver.Footnote 66

Labor and Race in Cusco’s 1572 Ordinances

As an Indigenous-majority highland city where more than one-quarter of Spanish men held repartimientos, colonial Cusco’s practices of unfree labor and racial discrimination developed in distinctive ways from those of Lima.Footnote 67 Cabildo records before 1570 rarely mention free Afro-Peruvians, and notarial archives focus on sales of enslaved individuals, rather than the lives of a growing free population. Major changes to Cusco’s labor market and race relations occurred in 1572, when the viceroy Francisco de Toledo consulted with the city’s leading Spaniards and devised new municipal ordinances.Footnote 68 Indigenous labor figured prominently in Toledo’s plan for governing Peru’s two republics, and the new regulations required local communities to send hundreds of day-laborers (jornaleros) to Cusco’s central plaza, where they were assigned tasks that included construction and sanitation.Footnote 69 Addressing the numerous Indigenous “vagabonds” in the region, Toledo ordered their compulsory service, promoting annual labor contracts (asientos) with Spaniards of all social statuses (vecinos, estantes y habitantes y encomenderos de indios). The ordinances specified daily wages for jornaleros, as well as annual payments for workers of different ages engaged in different kinds of work.Footnote 70 They also recognized Indigenous artisans (oficiales) and allowed them to take apprentices, but required Spanish oversight in some areas, such as silver and gold work.Footnote 71 One Spaniard recalled that the Toledan ordinances exempted skilled Indigenous workers from municipal day labor and service to Spaniards, so that even the Inca nobility were eager to learn shoemaking and other trades.Footnote 72

Cusco’s Toledan ordinances formalized new racial inequalities, including allowing Spanish artisans to charge more than Indigenous and Black professionals.Footnote 73 Penalties announced for illegal logging, herding, and brewing differed by race, with public beatings limited to non-Spaniards.Footnote 74 Cusco’s jail was to be segregated by race and gender, with different treatment for non-Spaniards.Footnote 75 Indigenous and Black Cusqueños were to be overseen by the juez de naturales, an office initially created for Indigenous administration.Footnote 76 That judge was to direct the settlement of negros horros, mulatos, and indios vagamundos with Spanish masters.

In addition to unequal treatment and a lack of legal representation, Afro-Peruvian people in Cusco were subject to ordinances specifically targeting them.Footnote 77 Some of the new laws applied to all Afro-Peruvians, regardless of status, restricting commercial activities and attempting to keep them out of Indigenous neighborhoods and villages. Others specifically addressed free negros and mulatos, whom the viceroy blamed for causing serious harm to the republic by aiding in the escape of enslaved individuals. One law imposed substantial financial penalties on free people of color who kept escaped “captives” (cautivos) in their homes or working on their rural estates. The most significant ordinance imposed restrictions on those properties and the people who owned them, specifying that, except for skilled workers (oficiales), free negros and mulatos could not have their own houses, and they had to make written contracts to serve masters (amos) within a month or leave the city.Footnote 78 Although these race-specific restrictions appeared within a rhetoric about the damages caused by free Afro-Peruvian people, Toledo also argued the “occupation and service” required of “the mulatos and zambahigos and freed slaves” was essential for benefiting Spaniards and relieving Indigenous people from hard labor.Footnote 79

After announcing his Cusco ordinances, Toledo continued to write that free Afro-Peruvians “should go about under greater subjugation,”Footnote 80 an attitude consistent with royal attempts to extract tribute from them. Despite the restrictions spelled out in the 1572 laws, many individuals found ways to evade them. Those with oficios were not subject to constraints on property ownership and residence, and many of those who were ordered to enter service under Spanish amos were able to make favorable arrangements. In 1577, Toledo complained that Afro-Peruvians had thwarted his order by finding Spaniards willing to enter into falsified contracts with them, “which they do so that they will not actually be forced to serve; rather, [the amos] make those asientos so as to have the title of domestic servants [criados] over such people without them actually serving them.”Footnote 81

Cusco’s Free Afro-Peruvian Population in 1582

When Cusco’s free Afro-Peruvian men and women learned of the corregidor’s intent to register them in 1582, they had spent nearly a decade navigating attempts to implement the Toledan ordinances. The registry was a familiar threat—part of a decades-long Spanish discourse about labor, race, and social status—although the new municipal effort responded to the interests of the incoming viceroy, Martín Enríquez de Almansa, whose tenure in New Spain (1568–1580) had coincided with intensified efforts to regulate and tax free Afro-Mexicans.Footnote 82 When Cusco’s corregidor issued his summons, he made racial and gender distinctions (e.g., negra/o, mulata/o) that applied only to free Afro-Peruvians, and his declared outcome of the registry distinguished between skilled laborers and those who were supposed to contract with Spanish amos for low-wage service. These differences reflected the intersecting practices of unfree and unfair labor that had been developing in early colonial Peru, which posed different risks to registrants and influenced what they shared with the Spanish notary.

Oficiales

Almost thirty individuals reported having a skilled occupation when they registered. These oficiales were not threatened with resettlement and contracts for low-wage labor to Spanish amos, and it is not surprising that most appear early in the registry, representing themselves during the proceeding. Their compliance was strategic, asserting a higher social standing while also withholding other personal information. Entries for oficiales, especially men, contain only professional details—locations of their workshops, names of work associates—while remaining silent about their spouses, children, and other properties. The most autonomous oficiales were a mostly-male group who owned their workshops and shops (tiendas), and thus controlled their space of work.Footnote 83 These men were among the first to register with the notary, with brief entries reporting surnames, occupation, and tienda ownership. They included the cobblers (çapateros) Antonyo de Miranda, Domingo Y., and Juan de Trujillo, and the baker (pastelero) Juan Ruiz.Footnote 84 These men reported owning tiendas on the city plaza (en la plaça de esta ciudad), indicating a significant presence of Afro-Peruvian businesses there. Other tienda owners included the tailor (sastre) Francisco Alvarez, and Gabriel Palomino, who owned a general store (pulperia).Footnote 85 In most cases, the notary attached these men’s mulato status to their profession (e.g., mulato sastre), distinguishing them from Spaniards who were permitted to charge more for the same work.

In addition to tienda owners, several oficiales described themselves as working “with” (trabaja con)—rather than “for”—other men, a phrasing distinct from the service relationships described elsewhere in the document. The cobbler Pedro de Laguna “worked with” Francisco Sanches, and the hosier (calçet[e]ro) Domingo Ruiz reported working with a man named Florencio.Footnote 86 Because no further identifying information was recorded, their work status was ambiguous, potentially organized as partnerships or artisan-journeyman contracts. Given that four of the five instances of this phrasing appear in the registry’s first ten entries, however, “with” appears to signify independence. Coworking was particularly common among blacksmiths, the most numerous group of oficiales. Juan de Banos reported working with Gonzalo Perez, a blacksmith with a shop in the arcades surrounding Cusco’s central plaza, whereas Juan Sanches worked with a group of smiths, possibly in a larger workshop.Footnote 87 Three other smiths, Juan Baptista, Juan Dominguez, and Miguel Martinez, maintained one or more workshops at an inn (meson) owned by a man named Diego Gomez. As with those who owned tiendas, men who “worked with” others are registered with their surnames, an identity marker that is rare among other lower-status Afro-Peruvian registrants.Footnote 88

Eight individuals identified oficios without providing details about property or work associates. This group included most women registered with oficios, a gendered contrast with the mostly-male workshop owners. A woman named Catalina said she had sold coca leaf and other merchandise in the Indigenous barter market since her childhood (vende coca e otras mercadurias en el gato desde niñez), an occupation licensed by the Spanish corregidor. Footnote 89 Maria Hernandez sold the same goods in the barter market, but the notary did not register a license for her and described her work as “haggling” (rregatar), rather than selling. She was married to an unnamed man from the Collagua group, a relationship facilitating her work with an Indigenous commodity in a space where colonial officials had repeatedly attempted to bar Afro-Peruvian commerce.Footnote 90

Two other women declared oficios directly engaged with Cusco’s diverse Andean population. Maria Ximenez, a free Black woman (negra horra) married to a man named Gaspar, appeared in an early registration assembly, and her entry was followed by that of Catalina Bravo, who resided in their house (esta en su casa). The notary reported that “these two women are bakers who feed many Indigenous migrants” (estas dos son pasteleras y dan de comer a muchos forasteros).Footnote 91 The pair, who appear to have been cohabitating business partners, represented themselves in the proceeding, a contrast with the silence and restraint of many free Afro-Peruvian women during their registration. The economic independence seen in the registration of oficiales highlights the fact that legal autonomy, property ownership, and skilled labor were more accessible to men. Only five of the registered oficiales were women, and they worked in the Indigenous economy without a fixed place of business. The Spanish notary represented some of their work as informal negotiations and reproductive labor. While registering the mulato baker Juan Ruiz as having a baked goods shop in the arcade surrounding the central plaza (tiene tienda de pasteles en el portal de la plaça), he wrote on the same day that Maria Ximenez and Catalina Bravo merely “gave food” to migrant workers, a phrasing similar to his entry for the morena servant Leonor de Loaysa, whose work included feeding a Spanish household and washing clothes (servir y dar de comer y lava ropa).Footnote 92

Although those with oficios were supposedly exempt from service contracts, several professional men described service to Spaniards. The mulato blacksmith Juan de Banos mentioned service to a Spaniard named Juanes de Castro, and the tailor Juan Fernandez, “who goes about with the professional tailors of this city” (pasa con oficiales sastres de esta ciudad), served the conquistador Mancio Serra.Footnote 93 It is not clear why these artisans were in service, but they provide a reminder that not all skilled laborers were free. Many of Cusco’s enslaved people were artisans, including a blacksmith named Pedro Miguel, who “worked with” a free mulato blacksmith named Francisco de Albornoz, and who was of sufficient reputation that he was training a mulato apprentice named Melchor.Footnote 94 The varying degrees of autonomy among oficiales make it difficult to interpret entries that do not specify an individual’s work environment and relationships. For example, Juan Ruiz appeared late in the proceeding and was recorded only as a “married carpenter,” and when the weaver (tejedor) Juan de Pomasi and his wife, Ysabel de Ojeda, registered, he offered no details about his occupation.Footnote 95

Contracted Services

The relationship between the enslaved blacksmith Pedro Miguel and his free apprentice Melchor highlights the fact that the skills for an oficio were acquired through a period of contracted subordination, an outgrowth of Iberian apprenticeship practices. The 1582 registry lists four individuals as serving in apprenticeships with other Afro-Peruvians. All were male, underscoring the gendered access to skilled work. Whereas one apprentice named Melchor appeared on his own behalf for the registry, an apprentice blacksmith named Juan Martinez probably accompanied his mulato master, Juan Baptista, to the proceeding.Footnote 96 On 11 July, Baptista registered himself with the Spanish notary along with two other blacksmiths, declaring that he maintained his own workshop at an inn. Later that day, after more than twenty other people had appeared, Baptista presented a mulata woman named Dominga who worked as his servant. Her registry entry was followed directly by that of his apprentice, Juan Martinez, who was among the last to be registered that day, after all oficiales had appeared.

In later gatherings, a mulato raft pilot (balzero) named Juan de Morales presented his apprentice, Pedro Anton, and a mulato youth named Marcos appeared on his own, declaring that he was learning unspecified skills from his father (esta con su padre aprendiendo el oficio), an enslaved man named Alonso.Footnote 97 The number of registered apprentices is small, but it indicates that free Afro-Peruvian youths typically apprenticed under free and enslaved Afro-Peruvian artisans.Footnote 98

Although apprenticeships in early colonial Cusco remain understudied, early records from Cuenca (Ecuador) offer details on Spanish practices. These were contracted between master artisans and young men, typically youths of thirteen to fifteen, who were represented by their father or custodian.Footnote 99 The contract (asiento) between master and apprentice defined a typical term of service of three or four years, during which masters held legal authority.Footnote 100 Masters taught skilled labor and provided basic subsistence—food, adequate clothing, medicine—but they rarely paid apprentices for their work.Footnote 101 Apprentices performed whatever labor their masters required in carrying out their oficios, as well as domestic tasks. They were prohibited from abandoning their work and returning home and were thus unfree laborers until the completion of their asiento. Footnote 102 Presumably, free Afro-Peruvian apprentices in Cusco who trained under other free men had similar contracts, whereas those learning from enslaved men presumably had legal relationships with their enslavers.

Whereas asientos of apprenticeship reflected a temporary subordination of young men who aspired to the independence of an oficio, the contracts promoted for non-oficiales were expected to be renewed, keeping free people in service. Francisco de Toledo acknowledged that free Afro-Peruvians thwarted his attempts to force them (and so-called indios vagamundos) into service contracts, a failure that is confirmed in the 1582 registry. The only instance where the notary reported seeing such a document was when Gregorio Mexia and Beatris Gonzales, a married couple described as Black (de color negros), presented their four-year service contract with Francisco de Tordoya.Footnote 103 Three other entries mention asientos, all of them involving Afro-Peruvian women. Francisca de Vargas and a woman named Luisa both presented themselves for registration, each declaring that she had an asiento with doña Luisa de la Cruz, a nun cloistered in the Santa Clara convent.Footnote 104 The women’s appearance at a proceeding outside the convent—where the high-born nun whom they served could not attend—speaks to a degree of freedom that contrasts with the entry for a woman named Catalina, who was presented by a man named Juan Gutierrez, who declared that she served him based on a contract that he had made with her, the terms of which were not specified.Footnote 105

Uncontracted Services

The small number of formally contracted relationships highlights the lack of progress that Spanish officials made in forcing free Afro-Peruvians into contractually-defined labor. This is not to say that the Cusco population was free from service. There are forty-two entries in the 1582 registry that refer to service (servir/servicio), describing the labor of more than fifty free individuals. Although some of these entries involved men with oficios, male apprentices, and (mostly) women with formally contracted asientos, most referred to individuals whose services in Spanish households were less clearly defined, although it is reasonable to assume that many were working without contracts. Of the forty-six individuals who fall into this category, thirty-two were women or girls, a gendered contrast with the mostly-male oficiales. Women and girls in service were more likely than men and boys of the same status to be listed without a surname, and to be presented for registration by a man—almost always a Spaniard—who spoke for them.Footnote 106 Several women in this group were mothers without a registered spouse or were described as unmarried (soltera), signifying a stronger tie to the Spanish household. These individuals had fewer means of strategically presenting and speaking for themselves, as the amos presented them before the notary and often described their servitude in ambiguous or quasi-familial terms, leaving uncertainty about the nature of their relationships and statuses.

Descriptions of women’s service rarely offer details about its terms or substance. A noteworthy exception to this was a morena woman named Catalina, who was presented by a man named Alvaro Hernandez, who stated that “she owes him 200 pesos, which he gave her for her manumission, and she is paying [the debt] back through the service that she gives.”Footnote 107 This debt servitude, which was at least defined in its financial terms, contrasts with the entry for Juana, an elderly mulata woman presented by the notary Antonio de Meres, who said only that she had served him “for a long time.”Footnote 108 Another mulata woman named Dominga was presented by Juan de Berrio Villavicencio, who said she served him “because she has been in the service of his house for a long time.”Footnote 109 Martin de Bustinça registered a woman named Juana, whom he described as a “mulata slave” (mulata esclava).

Several men and boys served in houses where their wives and mothers were registered as servants, but a few men emphasized their own connections to prominent Spanish officials. Diego Martin de Almagro stated that he served Cusco’s corregidor. Footnote 110 Another mulato man, Domingo Roxo, said that he and his wife cultivated wheat for the cantor of Cusco’s cathedral.Footnote 111 Whereas those men presented themselves for registration, the Spanish constable Bartolome Baez brought a free moreno man named Pedro de Villagran and a “mulatillo” named Diego for registration, saying they served him as soldiers.Footnote 112

Although documents promoting contractual service identified Spanish men as appropriate amos, the 1582 registry includes at least one case where an Afro-Peruvian was in service to another (Dominga, the servant of the blacksmith Juan Baptista), and there are five examples of service given to Spanish women. Given the patriarchal structure of the Spanish legal system, it is not surprising that the women named as “mistresses” of Afro-Peruvian servants did not appear before the notary, and that they had special social statuses. One was the nun doña Luisa de la Cruz, who had asientos with two women, while a widow named Ana Ribero was identified as the mistress of Luzia, a mulata woman born in her house.Footnote 113 Another mulata woman named Luysa was presented by Damian de la Bandera on behalf of his mother-in-law, Maria de Balenzuela, and a woman named Mencia testified that she served doña Luisa Narbaez, the wife of Francisco de Saavedra.Footnote 114 These exceptional cases reinforce the reality that it was typically wealthy Spanish men who directly claimed domestic services performed by Afro-Peruvian women.

Family Service

Several of the women serving in the homes of Spanish men had children who were registered with them. A mulata woman named Ynes lived and served in the house of the conquistador Alonso de Mesa, along with her daughter Francisca. Another woman, named Barbola, resided with her two daughters in Alonso Paniagua’s house.Footnote 115 Meanwhile, Catalina worked alongside her daughter, Juana, in the home of the notary Antonio Sanchez.Footnote 116 Catalina was married to an Indigenous man, whereas the other two women did not have a spouse registered. By contrast, the entire family of a mulata woman named Francisca—including her son, Alonso, who served as a page—lived and served in the house of Francisco Moreno, who said that Francisca had been born and raised there (nacido y criadose en su casa).Footnote 117

There were several men and women described as criada/o living in the homes of royal officials, municipal officeholders, and high-ranking clergy. Although legally free, they remained in ambiguous domestic relationships, undefined on a spectrum between chattel and kin. At least some of the individuals described as mulata/o were probably the progeny of the Spaniards whom they served, although such relationships are never mentioned in the 1582 registry.Footnote 118 While claiming to have raised Afro-Peruvian servants as part of their household, Spaniards also entrusted Afro-Peruvian women to serve as wet nurses and caregivers for their sons, a relationship that inverted the language of service and nurturing. A woman named Beatriz was registered as “a governess [ama] who is raising [cria] a son of Pedro Alonso Carrasco,”Footnote 119 and Damian de Bandera registered two amas, Teresa and Gracia, each of whom was caring for one of his sons.Footnote 120 Teresa had been raised in his household, and Gracia was an unmarried woman with no other domestic ties.

Women represented the majority of those described as criada/o. Whereas women living in Spanish households performed childcare, cooking, and laundry, male criados apparently conducted other kinds of work. Young men served as pages and apprentices, and a mulato criado named Juan Lucas said that he worked in a slaughterhouse for the royal treasurer Garcia de Melo.Footnote 121 In one unusual arrangement, a mulato man named Julian de Hojeda and his sons, Gaspar Llanos and Sebastian, provided unspecified services in the house of the military captain Martin Llanos.Footnote 122

Kin Connections and Afro-Peruvian Identities

Whereas the likely Spanish parentage of many of Cusco’s mulatos and mulatas was not mentioned in the 1582 registry, several registry entries noted relationships that free people had with enslaved men. A tailor named Santiago was the son of an enslaved man also called Santiago.Footnote 123 A mulata woman named Luzia was the daughter of an enslaved man named Anton, and she served in the house where she had been born.Footnote 124 Marcos, a mulato youth, was the son of an enslaved man named Alonso and was learning his oficio from him.Footnote 125 The fact that all three of these individuals were identified as having mixed racial heritage and enslaved fathers raises intriguing questions about their ancestry and social status. In addition to these children of enslaved men, there were at least four free mulata women—Madalena de Sauzedo, Catalina, Ysavel Hernandez, and Geronima—who were married to enslaved men.Footnote 126

These marriages serve as a reminder that Spaniards in Cusco continued to acquire enslaved individuals of African heritage, many of whom succeeded in gaining their freedom. Marriages between free women and enslaved men represent one of the many diverse households that Afro-Peruvians created while navigating the opportunities and constraints of manumission in Spanish colonial cities, potentially shedding light on the priorities that couples might have had for pursuing freedom for themselves and their children.Footnote 127 These mixed-status marriages also reflect the tendency to ascribe different degrees of perceived blackness to enslaved and free statuses.Footnote 128 Whereas only one mulata woman registered in 1582 was enslaved, at least four “black” (negra/o) or “dark-complexioned” (morena/o) individuals were described as manumitted (horra/o), including a woman named Catalina, who performed domestic service to repay the costs of her freedom.Footnote 129 One of the other rare instances of Afro-Peruvians with an asiento for service was a free Black couple, Gregorio Mexia and Beatris Gonzales. The predominance of free people described as mulata/o contrasts with notarial records of sales of enslaved people in sixteenth-century Cusco.Footnote 130 Individuals identified as mulata/o are rare, whereas those identified as morena/o are mentioned more commonly, their skin color associated with populations from the Atlantic coast of sub-Saharan Africa, including Angola, Bran, Biafra, and Sape.Footnote 131 A few free people also appear in these records (as morena libre). Enslaved people described as negra/o are by far the majority of those recorded in the sales transactions, with men appearing more frequently than women. In administrative proceedings, the labels of negra/o, morena/o, and mulata/o might reflect a shorthand for enslavement, manumission, and free birth. On the streets of Cusco, people originating from different parts of Africa and with varying mixes of European and Indigenous ancestry were part of a diverse Afro-Peruvian population whose phenotypical variation created opportunities for navigating racial identity and status in the uneven terrain of the evolving colonial legal system.

In addition to registrants with an enslaved parent or spouse, several women were married to Indigenous men. Despite Spanish claims that Black-Indigenous interactions were mutually harmful, there are records of multiple interracial marriages between free Afro-Peruvians and Andean people of different identities and statuses.Footnote 132 A 1579 lawsuit between a mulata woman named Beatriz Gonzales and a negro horro named Anton de Hojeda included an Inca witness who testified that the plaintiff was his niece.Footnote 133 Several women registered in 1582 were married to Andean men who lived in different parts of the former Inca capital. As noted already, Maria Hernandez, the mulata woman who “haggled” in the barter market, was married to a Collagua man of unknown status.Footnote 134 Another woman, Juana, was married to a Collagua man named Alonso Hanco, a silversmith who lived in the parish of Santiago.Footnote 135 A mulato man named Pedro de Mesa was married to a local Indigenous woman and lived in the Hospital parish.Footnote 136 Other interracial couples were tied more firmly to service in Spanish households. For example, Ysabel and Juana, two mulata women who served Pedro Alonso Carrasco, were both married to Indigenous yanaconas in his service.Footnote 137

These marriage details highlight the small number of registrants who chose to provide information about whether they were married or had children. In total, there were only twenty-eight individuals recorded as having a spouse, and only twenty-two of those spouses were named. The underreporting of family information was associated with gender and status. Of the mostly-male group of oficiales, only about one quarter (n=8) identified a spouse, and none of them mentioned having children. Representing themselves in the proceeding, skilled laborers divulged only the information necessary to exempt them—and by extension, their households—from the possible imposition of service to Spaniards. Across the registry, the small number of reported children suggests that they were strategically omitted by parents who saw no advantage to sharing their existence and identity with the notary.Footnote 138 Five married couples mentioned a child, whereas the other minors in the registry were either listed with unpartnered parents (n=6) or described as wards or apprentices. At the lower end of the Afro-Peruvian status spectrum, Spaniards frequently provided information about the marriage status and children of the women they presented as servants.Footnote 139

Many documented couples were in mixed-status marriages, including six Afro-Peruvian-Indigenous relationships, and at least four in which the Afro-Peruvian husband was enslaved. In most of these cases, the registering spouse was a woman, and it is possible that the disclosure of spousal information was intended to demonstrate an existing service connection to a Spanish household. Of the five men who identified a spouse but not a profession, two mentioned their service to Spanish officials, and a third presented the contract that he and his wife had with a Spaniard.

Whereas most registered married couples presented information to demonstrate that they were already in service, some of those who did not do so chose to give evidence of their socioeconomic stability by declaring ownership of houses and other property. A morena woman named Maria and her negro horro husband, Juan de Asis, stated that they lived in their own house with their infant son, while a mulato man named Pasqual Ynfante said that he owned a house on a plot of land in Tecsi Cocha, as well as agricultural fields and other lands in and around Cusco that sustained him, his wife, and his siblings.Footnote 140 Pedro de Mesa and his Indigenous wife had a house in Cusco’s mostly Indigenous Hospital parish.Footnote 141 Evidence of fixed residence and financial means might have been intended to argue that these families were not the kinds of “vagabonds” targeted by the registration proceeding, but this was a potentially risky gambit, given the recent Toledan ordinances that prohibited Afro-Peruvians without oficios from living in their own homes. It is noteworthy that the only person with an oficio who mentioned domestic arrangements was the baker Catalina Bravo, who stated that she lived in the house of her business partner, a married woman.

The effort that some couples made to present themselves as stable and virtuous families contrasts with the claims that wealthy and powerful Spaniards made regarding Afro-Peruvian individuals as belonging to their households. Because registrants underreported information about families and places of residence, the largest documented household with free Afro-Peruvian residents was that of a Spaniard, don Antonio Pereyra, who registered seven men and women in his service. The son of a conquistador, Pereyra lived off an encomienda of almost three hundred Indigenous tributary households, and he actively accumulated unfree labor in his Cusco home.Footnote 142 Documents from the early 1560s record his purchase of at least six enslaved Afro-Peruvian men, and the 1585 sale of an enslaved woman named Ynez mentioned that she had previously been acquired from Pereyra.Footnote 143 It is not clear how any of these individuals might have been related to the seven free mulato men and women living with and serving Pereyra in 1582.

Other wealthy Spaniards also claimed multiple free Afro-Peruvian men and women as part of their households. The conquistador Mancio Serra identified three individuals as criados, and the tailor Juan Fernandez also reported that he served Serra.Footnote 144 Pedro Alonso Carrasco, the son of another conquistador, received service from three women, who were married to unfree men (an enslaved man and two Indigenous yanaconas) attached to his household.Footnote 145 A mulata woman named Beatriz was his son’s nurse, and her sister Juana also served Carrasco. The free women and men who registered in 1582 were much more likely to present themselves as spouses and parents in the context of service to Spaniards than as members of autonomous Afro-Peruvian households.

As a whole, the social performances recorded in the 1582 registry reflect the varying individual autonomy and positionality found within Cusco’s Afro-Peruvian population, which was shaped by occupation, gender, and existing ties to Spanish households. While oficiales proudly declared their successes as skilled laborers and shop owners, domestic servants were presented by Spanish men who spoke for them. Many individuals resorted to selective compliance and silence while navigating the proceedings; those who spoke appear to have furnished details that they thought would insulate them from the intended application of the registry, including connections to wealthy and influential Spaniards.

Aftermath

Although details on Cusco’s free Afro-Peruvian population are scarce for the decades following the registry, all evidence indicates that Spanish officials across the Andes failed to settle unskilled Afro-Peruvian laborers with Spanish masters. Colonial officials continued to complain about their inability to keep Afro-Peruvians (and other groups) living and working where they wanted them, and some advocated lowering tribute demands and providing opportunities for education and job training to prevent vagabondage.Footnote 146 In 1590, the viceroy García de Mendoza noted that Lima had large numbers of free Afro-Peruvians and Indigenous yanaconas and others who had fled their repartimientos, who supported themselves through day labor and artisan work, without paying any tribute at all.Footnote 147 Five years later, a real cédula noted the damages still reportedly caused by unmarried “vagabonds” of all racial backgrounds in rural Indigenous communities, ordering those who knew oficios to use them, and those that lacked skills to learn them, serve amos, or find some other means of support.Footnote 148 At the turn of the seventeenth century, efforts to document Lima’s free Afro-Peruvian population managed to record several hundred individuals, but almost three-quarters were recorded as unmarried women (solteras), most of whom were probably domestic servants.Footnote 149 Philip III continued to promote coerced labor for unemployed and unskilled workers, writing in 1601 that “Spaniards of a servile and lazy disposition … and the free mestizos, negros, mulatos, and zambaigos should be compelled to work and be occupied through their day labor [jornales] in the service of the republic.”Footnote 150 Although service in elite households was still seen favorably, promotion of Afro-Peruvian resettlement and long-term asientos faded as the colonial demand for day labor in mining, hacienda agriculture, public works, and other unskilled occupations increased.Footnote 151

As Spanish policy pivoted toward coerced day labor for all unskilled and poor individuals, race-specific restrictions continued to target both free and enslaved Afro-Peruvians. The leyes de Indias addressed enslaved people in a distinct area of law (Book 8, Title 18), stressing the connection between the identity of negro/a and an unfree status. By contrast, the free Afro-Peruvian population of negros libres, mulatos, and zambaigos was often lumped together with mestizos, and sometimes with poor españoles, who were supposed to settle and work in Spanish towns. They were also targeted based on race by new restrictions, including prohibitions on carrying weapons, riding horses, keeping Indigenous servants, and being buried in coffins.Footnote 152 Some were repeatedly issued as colonial officials acknowledged that they remained unenforced.Footnote 153 Spanish officials persisted in their efforts to collect special tribute from free Afro-Peruvians, with limited success. The viceroy Francisco de Borja wrote in 1621 that Lima’s free Afro-Peruvian population resisted tax collectors with complaints and legal grievances, concluding that “[t]his tribute is of little substance and very great nuisance.”Footnote 154

By that time, more than thirteen thousand Afro-Peruvians lived in Lima, more than half of the city’s diverse population.Footnote 155 The viceregal capital’s market networks, systems of apprenticeship, and religious confraternities provided greater opportunities for Afro-Peruvian community-building and structured paths for social mobility, despite continued racial discrimination.Footnote 156 Documents from seventeenth and eighteenth century Lima attest to the successes that many Afro-Peruvians had in defending their rights and property and petitioning for greater autonomy.Footnote 157 The size, diversity, and prosperity of the Black community in Lima created opportunities for personal status renegotiations and participation in celebrations of “sovereign joy” that might not have been possible in smaller cities like Cusco.Footnote 158

The demographic trajectory of Cusco and its surrounding region differed significantly from that of Lima, and the Afro-Peruvian population did not grow substantially after the late 1500s. As an Indigenous-majority city drawing extensive encomienda labor, Cusco’s urban development was tied to the long-term impacts of rural resettlement (reducciones) and subsequent titling and sale of large swaths of Indigenous farmland (composiciones de tierras), which unfolded during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.Footnote 159 Population declines related to disease and chronic overwork through the colonial mita reduced the amount of labor extracted from tributary communities, while the population of Indigenous migrants (forasteros) grew substantially in rural Cusco and in most of the city’s parishes.Footnote 160

The increase in the availability of Indigenous day-laborers might help to explain why the free Afro-Peruvian population of the city did not increase along with that of other groups.Footnote 161 Although notary records attest to the continued sale of enslaved Afro-Peruvians in Cusco, the associated costs and logistics limited the use of unfree labor, and seventeenth-century sources only identify a few hundred Afro-Peruvians (free and enslaved).Footnote 162 Census data from 1690 report just forty-six negros in Cusco, compared with 2773 españoles and mestizos, and 7195 Indigenous residents.Footnote 163 Cusco’s Afro-Peruvian population was predominantly free and native-born, but its numbers did not increase significantly over time, possibly because of the challenges of competing with Indigenous forasteros and better-paid Spanish oficiales. Footnote 164 While sought after for labor in multiple economic sectors, they would always make up a small percentage of Cusco’s demographics, serving as a “complementary” workforce.Footnote 165 Census data from 1795 identified free Afro-Peruvians as just 2.6 percent of the city’s total population (645 of 24,842).Footnote 166

This “low numerical strength” created more opportunities for Spaniards to implement legal and de facto limits on Afro-Peruvian social mobility in Cusco.Footnote 167 As people of different parentage, status, and personal connections navigated racial discrimination, their tactics did not coalesce into a community based on a shared racial identity.Footnote 168 Afro-Peruvian oficiales do not appear to have established their own guilds, and their work engaged with Spanish artisans who sometimes attempted to restrict their trade.Footnote 169 For example, a 1591 decree for the city’s tailors and hosiers prohibited Blacks and enslaved people from maintaining a public shop or cutting new cloth, except in the house of a certified oficial. Footnote 170 The extent of such restrictions is unknown, and free and enslaved people continued to learn and perform skilled work during the seventeenth century.Footnote 171 While Afro-Peruvian oficiales engaged with Spanish-dominated guilds in the pursuit of their professions, domestic servants, mostly women, continued to navigate subordinate relationships in the wealthiest households of Cusco. The surviving documentation affirms this group’s limited potential for social mobility, maintained through debt, vague terms of service, and kin ties to others living in the household.Footnote 172 Despite official barriers, other Afro-Peruvians established business and marriage relationships with people in Indigenous parishes and towns, which facilitated work as market vendors and muleteers (arrieros).Footnote 173 The disparate social engagements pursued by Afro-Peruvian artisans, servants, and traders reflect the continuity of practices seen in the 1582 registry, although opportunities for social mobility might have become more limited over time.Footnote 174

As free Afro-Peruvians confronted obstacles to their social advancement in Cusco, relocation to Lima or another colonial center might have offered an opportunity to pursue economic opportunities and renegotiate social and racial identities. People with work skills and family connections outside Cusco were probably better-positioned to take advantage of migration opportunities, and men were more likely to extricate themselves from domestic relations tying them to the city. The 1582 registry demonstrates the limited potential for social mobility that many women had in Spanish households, as well as the clear avenues for the reproduction of servitude as their children, especially their daughters, grew up serving alongside their mothers. It appears that domestic service became more established over time, with more details of contracts, and a “preference” for locally-raised mulatas. However, the ambiguities surrounding terms of service remained a powerful tool for control.Footnote 175

For Afro-Peruvians who remained in Cusco, it is possible that some mixed-race individuals gradually “blended” into new identities with a change in recognized calidad as colonial racial categories proliferated and became more permeable.Footnote 176 Just as moreno was a significant socio-cultural and racial distinction in Lima, it also appears in the 1582 registry for native Afro-Cusqueños, perhaps gradually distinguished from formal records of “negros.”Footnote 177 Afro-Peruvian engagement with Indigenous populations via marriage and work might eventually have led to blurred and strategic shifts to a mestizo identity that potentially offered greater freedom, opportunity, mobility, and community.Footnote 178

Although the 1582 registry reflects ongoing Spanish strategies to monitor and control free Afro-Peruvians based on race, class, and gender, it also illustrates the strategic ways that people navigated the registration process to communicate their social attainments while also minimizing their exposure to official scrutiny. This document captures compelling glimpses of people who successfully acquired work skills, accumulated property, and controlled the conditions of their labor to varying degrees, despite the promulgation of laws and social practices that discriminated based on racial identity. We also see a sharp contrast in the short entries and silences of people who remained enmeshed in Spanish households and others who had fewer opportunities for overcoming social and economic marginalization. These intersectional differences speak to the ongoing redefinition of unfree labor along differences of race, class, and gender, and how this affected the ways that free Afro-Peruvians were able to pursue autonomy, build family and social networks, and foster a sense of community in Cusco.

Acknowledgments

We thank Serline Coelho and Nicolas Silva for their contributions to the initial literature review, and Jesús Galiano Blanco for producing the transcript of the 1582 registry. We are grateful for the support of the journal’s editorial team, and the detailed commentary of three anonymous reviewers, which guided us to significant improvements of a paper whose remaining flaws remain our own.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests that could interfere with the objectivity or integrity of a publication.