1. Introduction

1.1. The KP and FDKP equations

The full-dispersion Kadomtsev–Petviashvili (FDKP) equation

where the Fourier multiplier ![]() $m$ is given by

$m$ is given by

\begin{equation*}m(\mathbf{D}) = \left( 1 + \beta |\mathbf{D}|^2 \right)^{\frac{1}{2}} \left( \frac{\tanh |\mathbf{D}|}{|\mathbf{D}|} \right)^{\frac{1}{2}} \left( 1 + \frac{2\mathrm{D}_2^2}{\mathrm{D}_1^2} \right)^{\frac{1}{2}}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}m(\mathbf{D}) = \left( 1 + \beta |\mathbf{D}|^2 \right)^{\frac{1}{2}} \left( \frac{\tanh |\mathbf{D}|}{|\mathbf{D}|} \right)^{\frac{1}{2}} \left( 1 + \frac{2\mathrm{D}_2^2}{\mathrm{D}_1^2} \right)^{\frac{1}{2}}\end{equation*}with ![]() $\mathbf{D} = -\mathrm{i}(\partial_x, \partial_y)$, was introduced by Lannes [Reference Lannes12] (see also Lannes and Saut [Reference Lannes and Saut13]) as an alternative to the classical Kadomtsev–Petviashvili (KP) equation

$\mathbf{D} = -\mathrm{i}(\partial_x, \partial_y)$, was introduced by Lannes [Reference Lannes12] (see also Lannes and Saut [Reference Lannes and Saut13]) as an alternative to the classical Kadomtsev–Petviashvili (KP) equation

\begin{equation}

(\zeta_t-2\zeta\zeta_x+\tfrac{1}{2}(\beta-\tfrac{1}{3})\zeta_{xxx})_x -\zeta_{yy}=0,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

(\zeta_t-2\zeta\zeta_x+\tfrac{1}{2}(\beta-\tfrac{1}{3})\zeta_{xxx})_x -\zeta_{yy}=0,

\end{equation}which arises as a weakly nonlinear approximation for three-dimensional gravity-capillary water waves. The parameter ![]() $\beta \gt 0$ measures the relative strength of surface tension; the case

$\beta \gt 0$ measures the relative strength of surface tension; the case  $\beta \gt \frac{1}{3}$ for strong surface tension is termed KP-I, while the case

$\beta \gt \frac{1}{3}$ for strong surface tension is termed KP-I, while the case  $\beta \lt \frac{1}{3}$ for weak surface tension is KP-II. The analogous convention is used for the FDKP equation, giving us an FDKP-I equation for the strong surface tension case studied in this paper.

$\beta \lt \frac{1}{3}$ for weak surface tension is KP-II. The analogous convention is used for the FDKP equation, giving us an FDKP-I equation for the strong surface tension case studied in this paper.

An FDKP solitary wave is a nontrivial, evanescent solution of (1.1) of the form ![]() $u(x,y,t)=u(x-ct,y)$ with wave speed

$u(x,y,t)=u(x-ct,y)$ with wave speed ![]() $c \gt 0$, that is, a localized solution of the equation

$c \gt 0$, that is, a localized solution of the equation

Similarly, a KP solitary wave is a nontrivial, evanescent solution of (1.2) of the form ![]() $\zeta(x,y,t)=\zeta(x-\tilde{c}t,y)$ with wave speed

$\zeta(x,y,t)=\zeta(x-\tilde{c}t,y)$ with wave speed ![]() $\tilde{c} \gt 0$, that is, a localized solution of the equation

$\tilde{c} \gt 0$, that is, a localized solution of the equation

where

\begin{equation*}

\tilde{m}(\mathbf{D}) = 1+\frac{\mathrm{D}_2^2}{\mathrm{D}_1^2} + \tfrac{1}{2}(\beta- \tfrac{1}{3})\mathrm{D}_1^2.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\tilde{m}(\mathbf{D}) = 1+\frac{\mathrm{D}_2^2}{\mathrm{D}_1^2} + \tfrac{1}{2}(\beta- \tfrac{1}{3})\mathrm{D}_1^2.

\end{equation*} Let us emphasize that these waves are fully localized, that is, decaying in all spatial directions. The KP equation allows a scaling, such that the wave speed ![]() $\tilde{c}$ can be normalized to unity by the transformation

$\tilde{c}$ can be normalized to unity by the transformation  $\zeta(x,y) \mapsto \tilde{c}\zeta(\tilde{c}^\frac{1}{2}x,\tilde{c}y)$, which converts (1.4) into the equation

$\zeta(x,y) \mapsto \tilde{c}\zeta(\tilde{c}^\frac{1}{2}x,\tilde{c}y)$, which converts (1.4) into the equation

While it is known that the KP-II equation does not admit any solitary waves (see de Bouard and Saut [Reference de Bouard and Saut5]), the situation is rather different for the KP-I equation. Letting ![]() $\zeta(x,y)=\zeta(\tilde{x},\tilde{y})$ with

$\zeta(x,y)=\zeta(\tilde{x},\tilde{y})$ with  $(\tilde{x},\tilde{y})=(\frac{1}{2}(\beta-\frac{1}{3}))^{\frac{1}{2}}(x,y)$, one can write the steady KP equation (1.5) in the alternative form

$(\tilde{x},\tilde{y})=(\frac{1}{2}(\beta-\frac{1}{3}))^{\frac{1}{2}}(x,y)$, one can write the steady KP equation (1.5) in the alternative form

\begin{equation}

\partial_x^2 (-\partial_x^2 \zeta + \zeta +\zeta^2)+\partial_y^2 \zeta =0,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\partial_x^2 (-\partial_x^2 \zeta + \zeta +\zeta^2)+\partial_y^2 \zeta =0,

\end{equation}in which we have dropped the tildes for notational simplicity. This equation has a family of explicit symmetric ‘lump’ solutions of the form

\begin{equation}

\zeta_k^\star(x,y)=-6\partial_x^2 \log \tau_k^\star(x,y),\qquad k=1,2,\ldots,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\zeta_k^\star(x,y)=-6\partial_x^2 \log \tau_k^\star(x,y),\qquad k=1,2,\ldots,

\end{equation}where ![]() $\tau_k^\star$ is a polynomial of degree

$\tau_k^\star$ is a polynomial of degree ![]() $k(k+1)$ with

$k(k+1)$ with ![]() $\tau_k^\star(x,y)=\tau_k^\star(-x,y)=\tau_k^\star(x,-y)$ for all

$\tau_k^\star(x,y)=\tau_k^\star(-x,y)=\tau_k^\star(x,-y)$ for all ![]() $(x,y) \in {\mathbb R}^2$; the first two members of the family are

$(x,y) \in {\mathbb R}^2$; the first two members of the family are

\begin{align*}

\tau_1^\star(x,y) &=x^2+y^2+3, \\

\tau_2^\star(x,y) &=x^6+3x^4y^2+3x^2y^4+y^6+25x^4+90x^2y^2+17y^4-125x^2+475y^2+1875.

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\tau_1^\star(x,y) &=x^2+y^2+3, \\

\tau_2^\star(x,y) &=x^6+3x^4y^2+3x^2y^4+y^6+25x^4+90x^2y^2+17y^4-125x^2+475y^2+1875.

\end{align*} Note that the KP lump solutions ![]() $\zeta_k^\star$ are smooth, decaying rational functions, so that the same is true of their derivatives of all orders. The functions

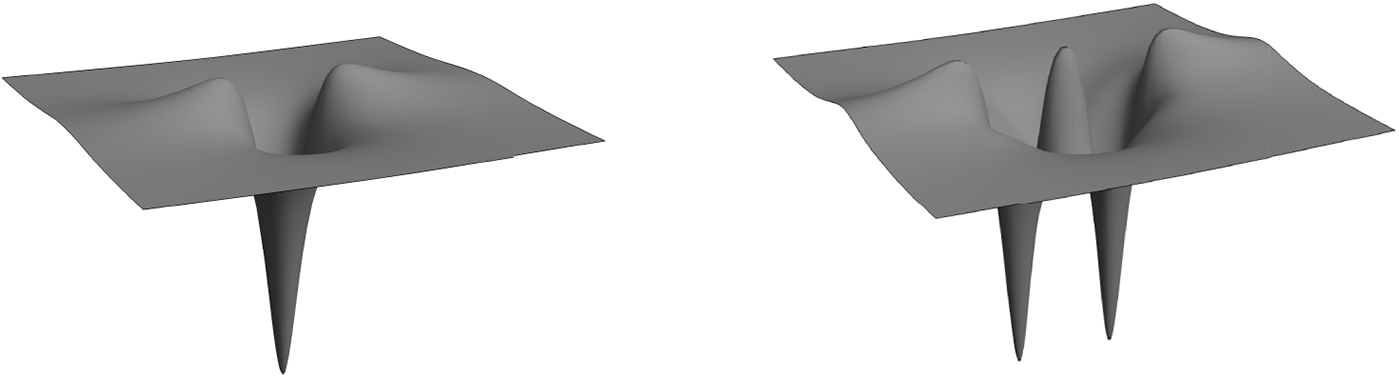

$\zeta_k^\star$ are smooth, decaying rational functions, so that the same is true of their derivatives of all orders. The functions ![]() $\zeta_1^\star$ and

$\zeta_1^\star$ and ![]() $\zeta_2^\star$ are sketched in Figure 1.

$\zeta_2^\star$ are sketched in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The KP lumps ![]() $\zeta_1^\star$ (left) and

$\zeta_1^\star$ (left) and ![]() $\zeta_2^\star$ (right).

$\zeta_2^\star$ (right).

The basic lump solution ![]() $\zeta_1^\star$ was found by Manakov et al [Reference Manakov, Zakharov, Bordag, Its and Matveev18], while the higher-order lump solutions were discovered by Pelinovskii and Stepanyants [Reference Pelinovskii and Stepanyants21] and fully classified by Galkin, Pelinovskii and Stepanyants [Reference Galkin, Pelinovskii and Stepanyants8] (see also Pelinovskii [Reference Pelinovskii19, Reference Pelinovskii20], Clarkson [Reference Clarkson3] and Clarkson and Dowie [Reference Clarkson and Dowie4]). These results have recently been reappraised by Liu and Wei [Reference Liu and Wei15] and Liu, Wei and Yang [Reference Liu, Wei and Yang16, Reference Liu, Wei and Yang17], who in particular discussed the nongeneracy of the lump solutions. Their work is summarized in the following result; see also the comments below the lemma.

$\zeta_1^\star$ was found by Manakov et al [Reference Manakov, Zakharov, Bordag, Its and Matveev18], while the higher-order lump solutions were discovered by Pelinovskii and Stepanyants [Reference Pelinovskii and Stepanyants21] and fully classified by Galkin, Pelinovskii and Stepanyants [Reference Galkin, Pelinovskii and Stepanyants8] (see also Pelinovskii [Reference Pelinovskii19, Reference Pelinovskii20], Clarkson [Reference Clarkson3] and Clarkson and Dowie [Reference Clarkson and Dowie4]). These results have recently been reappraised by Liu and Wei [Reference Liu and Wei15] and Liu, Wei and Yang [Reference Liu, Wei and Yang16, Reference Liu, Wei and Yang17], who in particular discussed the nongeneracy of the lump solutions. Their work is summarized in the following result; see also the comments below the lemma.

(i) Every smooth, algebraically decaying solution of the KP-I equation (1.6) has the form

$\zeta(x,y)=-6\partial_x^2 \log \tau(x,y)$, for some polynomial

$\zeta(x,y)=-6\partial_x^2 \log \tau(x,y)$, for some polynomial  $\tau$ of degree

$\tau$ of degree  $k(k+1)$ with

$k(k+1)$ with  $k \in {\mathbb N}$ and satisfies

$k \in {\mathbb N}$ and satisfies  $|\zeta(x,y)| \lesssim (1+x^2+y^2)^{-1}$ for all

$|\zeta(x,y)| \lesssim (1+x^2+y^2)^{-1}$ for all  $(x,y) \in {\mathbb R}^2$.

$(x,y) \in {\mathbb R}^2$.(ii) There is a unique symmetric solution

$\zeta_k^\star$ of the form (1.7) for each

$\zeta_k^\star$ of the form (1.7) for each  $k \in {\mathbb N}$ with

$k \in {\mathbb N}$ with  $k(k+1) \leq 600$.

$k(k+1) \leq 600$.(iii) The solutions

$\zeta_1^\star$,

$\zeta_1^\star$,  $\zeta_2^\star$ are nondegenerate: the only smooth evanescent solution of the linearized equation

for

$\zeta_2^\star$ are nondegenerate: the only smooth evanescent solution of the linearized equation

for \begin{equation*}

\partial_x^2(-\partial_x^2 w +w +2 \zeta_k^\star w)+\partial_y^2w=0

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\partial_x^2(-\partial_x^2 w +w +2 \zeta_k^\star w)+\partial_y^2w=0

\end{equation*} $k=1$,

$k=1$,  $2$ that is also invariant under

$2$ that is also invariant under  $w(x,y) \mapsto w(-x,y)$ and

$w(x,y) \mapsto w(-x,y)$ and  $w(x,y) \mapsto w(x,-y)$ is

$w(x,y) \mapsto w(x,-y)$ is  $w(x,y)=0$.

$w(x,y)=0$.

It is conjectured that part (ii) actually holds for all ![]() $k \in {\mathbb N}$ (see Liu, Wei and Yang [Reference Liu, Wei and Yang17]); furthermore, a sketch of the proof of the nondegeneracy of

$k \in {\mathbb N}$ (see Liu, Wei and Yang [Reference Liu, Wei and Yang17]); furthermore, a sketch of the proof of the nondegeneracy of ![]() $\zeta_k^\star$ for

$\zeta_k^\star$ for ![]() $k \geq 3$ was given by Liu, Wei and Yang [Reference Liu, Wei and Yang16], and here we accept the validity of this result. The existence of a solitary-wave solution to the FDKP-I equation was proved by Ehrnström and Groves [Reference Ehrnström and Groves7] using a variational method, and in this paper, we considerably improve our previous result by using a perturbation argument in place of constrained minimization to prove the following theorem, which establishes the existence of FDKP solitary waves ‘close’ to

$k \geq 3$ was given by Liu, Wei and Yang [Reference Liu, Wei and Yang16], and here we accept the validity of this result. The existence of a solitary-wave solution to the FDKP-I equation was proved by Ehrnström and Groves [Reference Ehrnström and Groves7] using a variational method, and in this paper, we considerably improve our previous result by using a perturbation argument in place of constrained minimization to prove the following theorem, which establishes the existence of FDKP solitary waves ‘close’ to ![]() $\zeta_k^\star$ for all

$\zeta_k^\star$ for all ![]() $k$ for which (iii) holds.

$k$ for which (iii) holds.

Theorem 1.2. For each ![]() $k \in {\mathbb N}$ and each sufficiently small value of

$k \in {\mathbb N}$ and each sufficiently small value of ![]() $\varepsilon \gt 0$, the FDKP-I equation (1.3) possesses a smooth, fully localized solitary-wave solution

$\varepsilon \gt 0$, the FDKP-I equation (1.3) possesses a smooth, fully localized solitary-wave solution ![]() $u_k^\star$ of wave speed

$u_k^\star$ of wave speed ![]() $c=1-\varepsilon^2$, which satisfies

$c=1-\varepsilon^2$, which satisfies

for all ![]() $(x,y) \in {\mathbb R}^2$ and

$(x,y) \in {\mathbb R}^2$ and

\begin{equation}

u_k^\star(x,y)=\varepsilon^2 \zeta_k^\star(\varepsilon x,\varepsilon^2 y)+ o(\varepsilon^2)

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

u_k^\star(x,y)=\varepsilon^2 \zeta_k^\star(\varepsilon x,\varepsilon^2 y)+ o(\varepsilon^2)

\end{equation}uniformly over ![]() $(x,y) \in {\mathbb R}^2$.

$(x,y) \in {\mathbb R}^2$.

Theorem 1.2 is proved in Sections 2–4 below.

1.2. The method

To motivate our method, it is instructive to review the formal derivation of the steady KP equation (1.5) from the steady FDKP equation (1.3). We begin with the linear dispersion relation for the time-dependent FDKP equation (1.1) with  $\beta \gt \frac{1}{3}$: the speed

$\beta \gt \frac{1}{3}$: the speed ![]() $c$ and wave number

$c$ and wave number ![]() $k_1$ of a two-dimensional sinusoidal travelling wave train satisfy

$k_1$ of a two-dimensional sinusoidal travelling wave train satisfy

\begin{equation*}

c= \left( 1 + \beta |k_1|^2 \right)^{\frac{1}{2}} \left( \frac{\tanh |k_1|}{|k_1|} \right)^{\frac{1}{2}}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

c= \left( 1 + \beta |k_1|^2 \right)^{\frac{1}{2}} \left( \frac{\tanh |k_1|}{|k_1|} \right)^{\frac{1}{2}}.

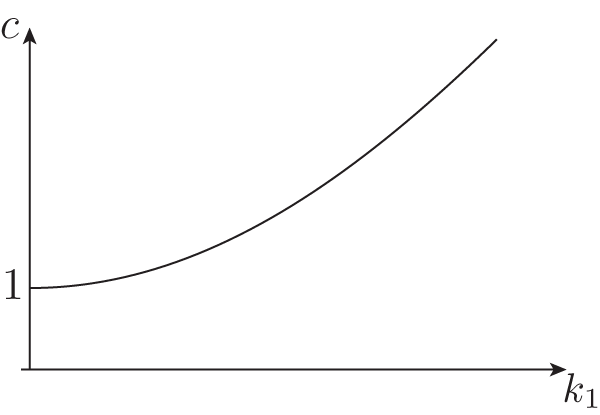

\end{equation*} The function ![]() $k_1 \mapsto c(k_1)$,

$k_1 \mapsto c(k_1)$, ![]() $k_1 \geq 0$ has a unique global minimum at

$k_1 \geq 0$ has a unique global minimum at ![]() $k_1=0$ with

$k_1=0$ with ![]() $c(0)=1$ (see Figure 2). Bifurcations of nonlinear solitary waves are expected whenever the linear group and phase speeds are equal, so that

$c(0)=1$ (see Figure 2). Bifurcations of nonlinear solitary waves are expected whenever the linear group and phase speeds are equal, so that ![]() $c^\prime(k_1)=0$ (see Dias and Kharif [Reference Dias and Kharif6, §3]), and one therefore expects bifurcation of small-amplitude solitary waves from uniform flow with unit speed. Furthermore, observing that

$c^\prime(k_1)=0$ (see Dias and Kharif [Reference Dias and Kharif6, §3]), and one therefore expects bifurcation of small-amplitude solitary waves from uniform flow with unit speed. Furthermore, observing that ![]() $m$ is an analytic function of

$m$ is an analytic function of ![]() $k_1$ and

$k_1$ and ![]() $\frac{k_2}{k_1}$ (note that

$\frac{k_2}{k_1}$ (note that  $|\mathbf{k}|^2 = k_1^2 + \frac{k_2^2}{k_1^2}k_1^2$ for

$|\mathbf{k}|^2 = k_1^2 + \frac{k_2^2}{k_1^2}k_1^2$ for ![]() $\mathbf{k} = (k_1,k_2)$), one finds that

$\mathbf{k} = (k_1,k_2)$), one finds that

\begin{equation}

m(\mathbf{k})=\tilde{m}(\mathbf{k}) + O(|(k_1,\tfrac{k_2}{k_1})|^4)

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

m(\mathbf{k})=\tilde{m}(\mathbf{k}) + O(|(k_1,\tfrac{k_2}{k_1})|^4)

\end{equation}as  $(k_1,\frac{k_2}{k_1}) \to 0$. The variables

$(k_1,\frac{k_2}{k_1}) \to 0$. The variables  $(k_1, \frac{k_2}{k_1})$ are intrinsic to the steady KP equation (1.5), and corresponding to them is the scaling

$(k_1, \frac{k_2}{k_1})$ are intrinsic to the steady KP equation (1.5), and corresponding to them is the scaling

Figure 2. FKDP-I dispersion relation for two-dimensional wave trains.

Substituting the Ansatz (1.10) with assumed wave speed

into the steady FDKP equation (1.3), one finds that, to leading order, ![]() $\zeta$ also satisfies the normalized KP equation (1.5). We henceforth assume that

$\zeta$ also satisfies the normalized KP equation (1.5). We henceforth assume that ![]() $c=1-\varepsilon^2$ for

$c=1-\varepsilon^2$ for ![]() $0 \lt \varepsilon \lt \varepsilon_0$, where

$0 \lt \varepsilon \lt \varepsilon_0$, where ![]() $\varepsilon_0$ is taken small enough for all our arguments to be valid.

$\varepsilon_0$ is taken small enough for all our arguments to be valid.

In the rigorous theory, we seek solutions of (1.3) in a suitable function space ![]() $X$ and identify a corresponding phase space

$X$ and identify a corresponding phase space ![]() $Z$ for this equation. These spaces, which are defined precisely in Section 2, satisfy

$Z$ for this equation. These spaces, which are defined precisely in Section 2, satisfy ![]() $X \subseteq Z \subseteq L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$. The relationship (1.9) between the symbols

$X \subseteq Z \subseteq L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$. The relationship (1.9) between the symbols ![]() $m$ and

$m$ and ![]() $\tilde m$ suggests that the spectrum of a solitary wave

$\tilde m$ suggests that the spectrum of a solitary wave ![]() $u$ is concentrated in the region

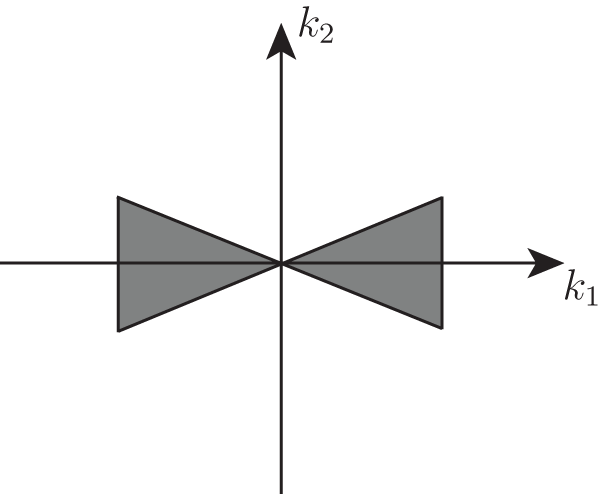

$u$ is concentrated in the region  $|k_1|, |\frac{k_2}{k_1}| \ll 1$. We therefore choose a fixed value of

$|k_1|, |\frac{k_2}{k_1}| \ll 1$. We therefore choose a fixed value of ![]() $\delta \in (0,1)$ and decompose

$\delta \in (0,1)$ and decompose ![]() $L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$, and hence also

$L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$, and hence also ![]() $X$ and

$X$ and ![]() $Z$, into the direct sum of subspaces of functions whose spectra are supported in the region

$Z$, into the direct sum of subspaces of functions whose spectra are supported in the region

\begin{equation}

C=\left\{\mathbf{k} \in {\mathbb R}^2 \colon |k_1| \leq \delta, \left|\frac{k_2}{k_1}\right| \leq \delta\right\}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

C=\left\{\mathbf{k} \in {\mathbb R}^2 \colon |k_1| \leq \delta, \left|\frac{k_2}{k_1}\right| \leq \delta\right\}

\end{equation}and its complement (see Figure 3), so that

\begin{equation*}

X=\underbrace{\chi(\mathbf{D})X}_{\displaystyle = X_1} \oplus \underbrace{(1-\chi(\mathbf{D}))X}_{\displaystyle = X_2}, \qquad

Z=\underbrace{\chi(\mathbf{D})Z}_{\displaystyle = Z_1} \oplus \underbrace{(1-\chi(\mathbf{D}))Z}_{\displaystyle = Z_2},

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

X=\underbrace{\chi(\mathbf{D})X}_{\displaystyle = X_1} \oplus \underbrace{(1-\chi(\mathbf{D}))X}_{\displaystyle = X_2}, \qquad

Z=\underbrace{\chi(\mathbf{D})Z}_{\displaystyle = Z_1} \oplus \underbrace{(1-\chi(\mathbf{D}))Z}_{\displaystyle = Z_2},

\end{equation*}

Figure 3. The cone  $C = \{\mathbf{k} \in {\mathbb R}^2 \colon |k_1| \leq \delta, |\tfrac{k_2}{k_1}| \leq \delta\}$.

$C = \{\mathbf{k} \in {\mathbb R}^2 \colon |k_1| \leq \delta, |\tfrac{k_2}{k_1}| \leq \delta\}$.

in which ![]() $\chi$ is the characteristic function of

$\chi$ is the characteristic function of ![]() $C$. Observing that

$C$. Observing that ![]() $X_1$,

$X_1$, ![]() $Z_1$ both coincide with

$Z_1$ both coincide with ![]() $\chi(\mathbf{D})L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$, we equip

$\chi(\mathbf{D})L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$, we equip ![]() $Z_1$ with the

$Z_1$ with the ![]() $L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$ norm and

$L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$ norm and ![]() $X_1$ with the equivalent scaled norm

$X_1$ with the equivalent scaled norm

\begin{equation}

|u_1|_\varepsilon^2 = \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} \bigg(|u_1|^2 + \varepsilon^{-2} |\mathrm{D}_1 u_1|^2 +

\varepsilon^{-2}\left|\frac{\mathrm{D}_2}{\mathrm{D}_1}u_1\right|^2\bigg)\, \mathrm{d} x\, \mathrm{d} y,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

|u_1|_\varepsilon^2 = \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} \bigg(|u_1|^2 + \varepsilon^{-2} |\mathrm{D}_1 u_1|^2 +

\varepsilon^{-2}\left|\frac{\mathrm{D}_2}{\mathrm{D}_1}u_1\right|^2\bigg)\, \mathrm{d} x\, \mathrm{d} y,

\end{equation}and employ a method akin to the Lyapunov–Schmidt reduction to determine ![]() $u_2\in X_2$ as a function of

$u_2\in X_2$ as a function of ![]() $u_1\in X_1$. With

$u_1\in X_1$. With ![]() $n(\mathbf{D})=m(\mathbf{D})-1$, the result is the equation

$n(\mathbf{D})=m(\mathbf{D})-1$, the result is the equation

for ![]() $u_1$ in the unit ball

$u_1$ in the unit ball

of ![]() $X_1$.

$X_1$.

Applying the KP scaling

so that the spectrum of ![]() $\zeta$ lies in the set

$\zeta$ lies in the set

\begin{equation*}

C_\varepsilon=\left\{\mathbf{k} \in {\mathbb R}^2 \colon |k_1| \leq \frac{\delta}{\varepsilon}, \left|\frac{k_2}{k_1}\right|\leq \frac{\delta}{\varepsilon}\right\},

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

C_\varepsilon=\left\{\mathbf{k} \in {\mathbb R}^2 \colon |k_1| \leq \frac{\delta}{\varepsilon}, \left|\frac{k_2}{k_1}\right|\leq \frac{\delta}{\varepsilon}\right\},

\end{equation*}one obtains the reduced equation

where

The remainder term ![]() $S_\varepsilon \colon B_M(0) \subseteq \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) Y^1 \rightarrow \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$ satisfies the estimates

$S_\varepsilon \colon B_M(0) \subseteq \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) Y^1 \rightarrow \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$ satisfies the estimates

\begin{equation*}

|S_\varepsilon(\zeta)|_{L^2} \lesssim \varepsilon^2| \zeta |_{Y^1}^3, \quad

|\mathrm{d} S_\varepsilon[\zeta]|_{\mathcal L(Y^1,L^2({\mathbb R}^2))}\lesssim \varepsilon^2| \zeta |_{Y^1}^2

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

|S_\varepsilon(\zeta)|_{L^2} \lesssim \varepsilon^2| \zeta |_{Y^1}^3, \quad

|\mathrm{d} S_\varepsilon[\zeta]|_{\mathcal L(Y^1,L^2({\mathbb R}^2))}\lesssim \varepsilon^2| \zeta |_{Y^1}^2

\end{equation*}(see Section 3), where

\begin{equation*}Y^1 = \{u \in L^2({\mathbb R}^2)\colon |u|_{Y^1} \lt \infty\}, \qquad

|u|_{Y^1}^2 = \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} \bigg(|u|^2 + |\mathrm{D}_1 u|^2 +

\left|\frac{\mathrm{D}_2}{\mathrm{D}_1}u\right|^2\bigg)\, \mathrm{d} x\, \mathrm{d} y\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}Y^1 = \{u \in L^2({\mathbb R}^2)\colon |u|_{Y^1} \lt \infty\}, \qquad

|u|_{Y^1}^2 = \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} \bigg(|u|^2 + |\mathrm{D}_1 u|^2 +

\left|\frac{\mathrm{D}_2}{\mathrm{D}_1}u\right|^2\bigg)\, \mathrm{d} x\, \mathrm{d} y\end{equation*}is the natural energy space for the KP-I equation (see de Bouard and Saut [Reference de Bouard and Saut5]); the constant ![]() $M \gt 1$ is chosen large enough so that

$M \gt 1$ is chosen large enough so that ![]() $\zeta_k^\star \in B_M(0)$, while the requirement that

$\zeta_k^\star \in B_M(0)$, while the requirement that ![]() $B_M(0)$ is contained in the range of the isomorphism

$B_M(0)$ is contained in the range of the isomorphism ![]() $u_1 \mapsto \zeta$ requires

$u_1 \mapsto \zeta$ requires ![]() $\varepsilon \leq M^{-2}$. In the formal limit

$\varepsilon \leq M^{-2}$. In the formal limit ![]() $\varepsilon \to 0$, the subspace

$\varepsilon \to 0$, the subspace ![]() $\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})Y^1$ ‘fills out’ all of

$\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})Y^1$ ‘fills out’ all of ![]() $Y^1$ and Equation (1.13) reduces to the KP equation (1.5).

$Y^1$ and Equation (1.13) reduces to the KP equation (1.5).

We demonstrate in Theorem 4.2 that Equation (1.13) has solutions ![]() $\zeta_k^\varepsilon$ which satisfy

$\zeta_k^\varepsilon$ which satisfy ![]() $\zeta_k^\varepsilon \rightarrow \zeta_k^\star$ as

$\zeta_k^\varepsilon \rightarrow \zeta_k^\star$ as ![]() $\varepsilon \rightarrow 0$ in a suitable subspace of

$\varepsilon \rightarrow 0$ in a suitable subspace of ![]() $Y^1$, and deduce our main Theorem 1.2 by tracing back the steps in the reduction procedure. One of the key arguments is based upon the nondegeneracy result given in Lemma 1.1(iii), which allows one to apply a variant of the implicit-function theorem. For this purpose we exploit the fact that the reduction procedure preserves the invariance of Equation (1.3) under

$Y^1$, and deduce our main Theorem 1.2 by tracing back the steps in the reduction procedure. One of the key arguments is based upon the nondegeneracy result given in Lemma 1.1(iii), which allows one to apply a variant of the implicit-function theorem. For this purpose we exploit the fact that the reduction procedure preserves the invariance of Equation (1.3) under ![]() $u(x,y) \mapsto u(-x,y)$ and

$u(x,y) \mapsto u(-x,y)$ and ![]() $u(x,y) \mapsto u(x,-y)$, so that Equation (1.13) is invariant under

$u(x,y) \mapsto u(x,-y)$, so that Equation (1.13) is invariant under ![]() $\zeta(x,y) \mapsto \zeta(-x,y)$ and

$\zeta(x,y) \mapsto \zeta(-x,y)$ and ![]() $\zeta(x,y) \mapsto \zeta(x,-y)$. It is necessary to use a low regularity version of the implicit-function theorem since the reduction in Section 3 is performed using the

$\zeta(x,y) \mapsto \zeta(x,-y)$. It is necessary to use a low regularity version of the implicit-function theorem since the reduction in Section 3 is performed using the ![]() $\varepsilon$-dependent norm

$\varepsilon$-dependent norm ![]() $|\cdot|_\varepsilon$ and thus does not yield information concerning the smoothness of

$|\cdot|_\varepsilon$ and thus does not yield information concerning the smoothness of ![]() $u_1$ as a function of

$u_1$ as a function of ![]() $\varepsilon$.

$\varepsilon$.

Ehrnström and Groves [Reference Ehrnström and Groves7] use a variational version of the reduction procedure outlined above to reduce a variational principle for Equation (1.3) to a variational principle for (1.13) and proceed by finding critical points of the reduced variational functional by the direct methods of the calculus of variations. Here, with some amendments, we use their functional-analytic setting and follow the steps in their reduction (see Sections 2 and 3 below), but study the reduced equation (1.13) in Section 4 in an entirely different manner, arriving at a much more comprehensive conclusion.

Perturbation arguments to construct localized solutions approximated by nondegenerate KP lump solutions have recently also been used for the Gross-Pitaevskii equation by Liu et al [Reference Liu, Wang, Wei and Yang14] (see also Chiron and Scheid [Reference Chiron and Scheid2] for a numerical approach) and for the steady water-wave problem with strong surface tension by Gui et al [Reference Gui, Lai, Liu, Wei and Yang11] and Groves and Wahlén [Reference Groves and Wahlén10], who included vorticity effects. The method has additionally been applied to physical problems approximated by other model equations, in particular to the Whitham equation by Stefanov and Wright [Reference Stefanov and Wright22] (perturbation of Korteweg–de Vries solitary waves), to the gravity-capillary steady water-wave problem by Groves [Reference Groves9] (perturbation of Korteweg–de Vries and nonlinear Schrödinger solitary waves) and Buffoni, Groves and Wahlén [Reference Buffoni, Groves and Wahlén1] (perturbation of two-dimensional Schrödinger solitary waves).

2. Function spaces

In this section, we introduce the Banach spaces used in our theory and state their main properties; the proofs of most of these results are given by Ehrnström and Groves [Reference Ehrnström and Groves7, §2]. We use the familiar scale ![]() $\{H^r({\mathbb R}^2), |\cdot|_{H^r}\}_{r \geq 0}$ of Sobolev spaces together with the anisotropic spaces

$\{H^r({\mathbb R}^2), |\cdot|_{H^r}\}_{r \geq 0}$ of Sobolev spaces together with the anisotropic spaces

\begin{align*}

X&=\{u \in L^2({\mathbb R}^2)\colon |u|_X \lt \infty\}, \qquad

|u|_{X}^2 = \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} \bigg( 1 + \frac{k_2^2}{k_1^2} + \frac{k_2^4}{k_1^2} + |\mathbf{k}|^{2s}\bigg) |\hat u(\mathbf{k})|^2\, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k}, \\

Z&=\{u \in L^2({\mathbb R}^2)\colon |u|_Z \lt \infty\}, \qquad

|u|_{Z}^2 = \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} \left( 1 + |\mathbf{k}| + k_1^2|\mathbf{k}|^{2s-3}\right) |\hat u(\mathbf{k})|^2\, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k},

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

X&=\{u \in L^2({\mathbb R}^2)\colon |u|_X \lt \infty\}, \qquad

|u|_{X}^2 = \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} \bigg( 1 + \frac{k_2^2}{k_1^2} + \frac{k_2^4}{k_1^2} + |\mathbf{k}|^{2s}\bigg) |\hat u(\mathbf{k})|^2\, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k}, \\

Z&=\{u \in L^2({\mathbb R}^2)\colon |u|_Z \lt \infty\}, \qquad

|u|_{Z}^2 = \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} \left( 1 + |\mathbf{k}| + k_1^2|\mathbf{k}|^{2s-3}\right) |\hat u(\mathbf{k})|^2\, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k},

\end{align*}in which the Sobolev index  $s \gt \frac{3}{2}$ is fixed and

$s \gt \frac{3}{2}$ is fixed and ![]() $u \mapsto \hat{u}$ denotes the unitary Fourier transform on

$u \mapsto \hat{u}$ denotes the unitary Fourier transform on ![]() $L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$. We also use the scale

$L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$. We also use the scale ![]() $\{Y^r,|\cdot|_{Y^r}\}_{r \geq 0}$, where

$\{Y^r,|\cdot|_{Y^r}\}_{r \geq 0}$, where

\begin{equation}

Y^r = \{u \in L^2({\mathbb R}^2)\colon |u|_{Y^r} \lt \infty\}, \qquad

|u|_{Y^r}^2 = \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} \bigg(1+k_1^2+\frac{k_2^2}{k_1^2}\bigg)^{\!r} |\hat u(\mathbf{k})|^2\, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

Y^r = \{u \in L^2({\mathbb R}^2)\colon |u|_{Y^r} \lt \infty\}, \qquad

|u|_{Y^r}^2 = \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} \bigg(1+k_1^2+\frac{k_2^2}{k_1^2}\bigg)^{\!r} |\hat u(\mathbf{k})|^2\, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k}.

\end{equation} Note that ![]() $Y^0=L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$ while

$Y^0=L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$ while ![]() $Y^1$ is the natural energy space for the KP-I equation (see de Bouard and Saut [Reference de Bouard and Saut5]). Ehrnström and Groves [Reference Ehrnström and Groves7] use only the space

$Y^1$ is the natural energy space for the KP-I equation (see de Bouard and Saut [Reference de Bouard and Saut5]). Ehrnström and Groves [Reference Ehrnström and Groves7] use only the space ![]() $Y^1$, there called

$Y^1$, there called ![]() $\tilde{Y}$, but the proof of the following proposition is a straightforward variant of the proof of Lemma 2.1(i) in that reference.

$\tilde{Y}$, but the proof of the following proposition is a straightforward variant of the proof of Lemma 2.1(i) in that reference.

Proposition 2.1. One has the continuous embeddings

\begin{equation*}

Y^r \hookrightarrow L^2({\mathbb R}^2), \quad H^{s-\frac{1}{2}}({\mathbb R}^2) \hookrightarrow Z \hookrightarrow L^2({\mathbb R}^2), \quad X \hookrightarrow H^s({\mathbb R}^2)

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

Y^r \hookrightarrow L^2({\mathbb R}^2), \quad H^{s-\frac{1}{2}}({\mathbb R}^2) \hookrightarrow Z \hookrightarrow L^2({\mathbb R}^2), \quad X \hookrightarrow H^s({\mathbb R}^2)

\end{equation*} for all ![]() $ r \geq 0$, and in particular

$ r \geq 0$, and in particular ![]() $X \hookrightarrow C_\mathrm{b}({\mathbb R}^2)$, the space of bounded, continuous functions on

$X \hookrightarrow C_\mathrm{b}({\mathbb R}^2)$, the space of bounded, continuous functions on ![]() ${\mathbb R}^2$.

${\mathbb R}^2$.

Proposition 2.2. The space ![]() $Y^1$ (and hence

$Y^1$ (and hence ![]() $Y^r$ for each

$Y^r$ for each ![]() $r \geq 1$) is

$r \geq 1$) is

(i) continuously embedded in

$L^p({\mathbb R}^2)$ for

$L^p({\mathbb R}^2)$ for  $2 \leq p \leq 6$,

$2 \leq p \leq 6$,(ii) compactly embedded in

$L^p_\mathrm{loc}({\mathbb R}^2)$ for

$L^p_\mathrm{loc}({\mathbb R}^2)$ for  $2 \leq p \lt 6$.

$2 \leq p \lt 6$.

Proposition 2.3. The space ![]() $Y^r$ is continuously embedded in

$Y^r$ is continuously embedded in ![]() $C_\mathrm{b}({\mathbb R}^2)$ for each

$C_\mathrm{b}({\mathbb R}^2)$ for each  $r \gt \frac{3}{2}$.

$r \gt \frac{3}{2}$.

Proof. Note that

\begin{equation*}

|u|_\infty \lesssim \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} |\hat{u}(\mathbf{k})|\, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k} \\

= \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} \bigg(1+k_1^2+\frac{k_2^2}{k_1^2}\bigg)^{\!-\frac{1}{2}r} \bigg(1+k_1^2+\frac{k_2^2}{k_1^2}\bigg)^{\!\frac{1}{2}r} |\hat{u}(\mathbf{k})|\, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k}

\leq |u|_{Y^r} I^\frac{1}{2},

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

|u|_\infty \lesssim \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} |\hat{u}(\mathbf{k})|\, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k} \\

= \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} \bigg(1+k_1^2+\frac{k_2^2}{k_1^2}\bigg)^{\!-\frac{1}{2}r} \bigg(1+k_1^2+\frac{k_2^2}{k_1^2}\bigg)^{\!\frac{1}{2}r} |\hat{u}(\mathbf{k})|\, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k}

\leq |u|_{Y^r} I^\frac{1}{2},

\end{equation*}where, with a change of variables,

\begin{equation*}

I=\int_{{\mathbb R}^2} \bigg(1+k_1^2+\frac{k_2^2}{k_1^2}\bigg)^{\!-r}\, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k} = \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} (1+|\mathbf{k}|^2)^{-r} |k_1|\, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k} \lt \infty.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

I=\int_{{\mathbb R}^2} \bigg(1+k_1^2+\frac{k_2^2}{k_1^2}\bigg)^{\!-r}\, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k} = \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} (1+|\mathbf{k}|^2)^{-r} |k_1|\, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k} \lt \infty.

\end{equation*} The continuity of ![]() $u$ follows from a standard dominated convergence argument with

$u$ follows from a standard dominated convergence argument with ![]() $\hat{u}$ as dominating function.

$\hat{u}$ as dominating function.

(i) The Fourier multiplier

$m(\mathbf{D})$ maps

$m(\mathbf{D})$ maps  $X$ continuously onto

$X$ continuously onto  $Z$.

$Z$.(ii) The formula

$u \mapsto u^2$ maps

$u \mapsto u^2$ maps  $X$ smoothly into

$X$ smoothly into  $Z$.

$Z$.

We decompose ![]() $u \in L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$ into the sum of functions

$u \in L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$ into the sum of functions ![]() $u_1$ and

$u_1$ and ![]() $u_2$ whose spectra are supported in the region

$u_2$ whose spectra are supported in the region ![]() $C$ defined in (1.11) and its complement (see Figure 3) by writing

$C$ defined in (1.11) and its complement (see Figure 3) by writing

where ![]() $\chi$ is the characteristic function of

$\chi$ is the characteristic function of ![]() $C$. Since they are subspaces of

$C$. Since they are subspaces of ![]() $L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$, the Fourier multiplier

$L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$, the Fourier multiplier ![]() $\chi(\mathbf{D})$ induces the orthogonal decomposition

$\chi(\mathbf{D})$ induces the orthogonal decomposition ![]() $X = X_1 \oplus X_2$ with

$X = X_1 \oplus X_2$ with ![]() $X_1{= } \chi(\mathbf{D}) X$,

$X_1{= } \chi(\mathbf{D}) X$, ![]() $X_2 {= } (1 - \chi(\mathbf{D})) X$ and analogous decompositions of the spaces

$X_2 {= } (1 - \chi(\mathbf{D})) X$ and analogous decompositions of the spaces ![]() $Y^r$ and

$Y^r$ and ![]() $Z$. We write

$Z$. We write ![]() $Z=Z_1 \oplus Z_2$, but retain the explicit notation

$Z=Z_1 \oplus Z_2$, but retain the explicit notation ![]() $\chi(\mathbf{D})Y^r$ and

$\chi(\mathbf{D})Y^r$ and ![]() $\chi(\mathbf{D})L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$. The spaces

$\chi(\mathbf{D})L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$. The spaces ![]() $X_1$,

$X_1$, ![]() $Z_1$ and

$Z_1$ and ![]() $\chi(\mathbf{D})Y^r$ all coincide with

$\chi(\mathbf{D})Y^r$ all coincide with ![]() $\chi(\mathbf{D})L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$, and

$\chi(\mathbf{D})L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$, and ![]() $|\cdot|_{L^2}$,

$|\cdot|_{L^2}$, ![]() $|\cdot|_{X}$,

$|\cdot|_{X}$, ![]() $|\cdot|_{Y^r}$ and

$|\cdot|_{Y^r}$ and ![]() $|\cdot|_{Z}$ are all equivalent norms for these spaces. We do however make specific choices in the theory below; we equip

$|\cdot|_{Z}$ are all equivalent norms for these spaces. We do however make specific choices in the theory below; we equip ![]() $Z_1$ and

$Z_1$ and ![]() $\chi(\mathbf{D})Y^r$ with

$\chi(\mathbf{D})Y^r$ with ![]() $|\cdot|_{L^2}$ and

$|\cdot|_{L^2}$ and ![]() $|\cdot|_{Y^r}$ respectively, and

$|\cdot|_{Y^r}$ respectively, and ![]() $X_1$ with the equivalent scaled norm

$X_1$ with the equivalent scaled norm

\begin{equation*}

|u_1|_\varepsilon^2 = \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} \bigg( 1 + \varepsilon^{-2} k_1^2 + \varepsilon^{-2} \frac{k_2^2}{k_1^2} \bigg) |\hat u_1(\mathbf{k})|^2\, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

|u_1|_\varepsilon^2 = \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} \bigg( 1 + \varepsilon^{-2} k_1^2 + \varepsilon^{-2} \frac{k_2^2}{k_1^2} \bigg) |\hat u_1(\mathbf{k})|^2\, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k}

\end{equation*} (see Equation (1.12)) in anticipation of the KP scaling ![]() $(k_1, k_2) \mapsto (\varepsilon k_1, \varepsilon^2 k_2)$.

$(k_1, k_2) \mapsto (\varepsilon k_1, \varepsilon^2 k_2)$.

Proposition 2.5. The mapping ![]() $n(\mathbf{D})=m(\mathbf{D})-1$ is an isomorphism

$n(\mathbf{D})=m(\mathbf{D})-1$ is an isomorphism ![]() $X_2 \to Z_2$.

$X_2 \to Z_2$.

Proposition 2.6. The estimates

and

hold for all ![]() $u_1 \in X_1$ and

$u_1 \in X_1$ and ![]() $v,w \in X$.

$v,w \in X$.

Finally, we introduce the space ![]() $Y_\varepsilon^r=\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})Y^r$, where

$Y_\varepsilon^r=\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})Y^r$, where ![]() $\chi_\varepsilon(k_1,k_2)=\chi(\varepsilon k_1, \varepsilon^2 k_2)$ (with norm

$\chi_\varepsilon(k_1,k_2)=\chi(\varepsilon k_1, \varepsilon^2 k_2)$ (with norm ![]() $|\cdot|_{Y^r}$), noting the relationship

$|\cdot|_{Y^r}$), noting the relationship

\begin{equation*}|u|_\varepsilon^2=\varepsilon|\zeta|_{Y^1}^2,

\qquad u(x,y)=\varepsilon^2 \zeta(\varepsilon x, \varepsilon^2 y)

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}|u|_\varepsilon^2=\varepsilon|\zeta|_{Y^1}^2,

\qquad u(x,y)=\varepsilon^2 \zeta(\varepsilon x, \varepsilon^2 y)

\end{equation*}for ![]() $\zeta \in Y_\varepsilon^1$. Observe that

$\zeta \in Y_\varepsilon^1$. Observe that ![]() $Y_\varepsilon^r$ coincides with

$Y_\varepsilon^r$ coincides with ![]() $\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})X$,

$\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})X$, ![]() $\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})Z$ and

$\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})Z$ and ![]() $\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$ for

$\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$ for ![]() $\varepsilon \gt 0$, and with

$\varepsilon \gt 0$, and with ![]() $Y^r$ in the limit

$Y^r$ in the limit ![]() $\varepsilon \rightarrow 0$.

$\varepsilon \rightarrow 0$.

3. Reduction

We proceed by making the Ansatz ![]() $c = 1 - \varepsilon^2$ and studying Equation (1.3) in its phase space

$c = 1 - \varepsilon^2$ and studying Equation (1.3) in its phase space ![]() $Z$. Note that

$Z$. Note that ![]() $u = u_1 + u_2 \in X_1 \oplus X_2$ satisfies this equation if and only if

$u = u_1 + u_2 \in X_1 \oplus X_2$ satisfies this equation if and only if

The first step is to solve (3.2) for ![]() $u_2$ as a function of

$u_2$ as a function of ![]() $u_1$ using the following result, which is proved by a straightforward application of the contraction mapping principle.

$u_1$ using the following result, which is proved by a straightforward application of the contraction mapping principle.

Theorem 3.1. Let ![]() $\mathcal W_1$,

$\mathcal W_1$, ![]() $\mathcal W_2$ be Banach spaces,

$\mathcal W_2$ be Banach spaces, ![]() $K$ be a continuous function

$K$ be a continuous function ![]() $\overline{B}_1(0) \subseteq \mathcal W_1 \to [0,\infty)$ and

$\overline{B}_1(0) \subseteq \mathcal W_1 \to [0,\infty)$ and ![]() $\mathcal F \colon \overline{B}_1(0) \times \mathcal W_2 \to \mathcal W_2$ be a smooth function satisfying

$\mathcal F \colon \overline{B}_1(0) \times \mathcal W_2 \to \mathcal W_2$ be a smooth function satisfying

\begin{equation*}

|\mathcal F(w_1,0)|_{\mathcal W_2} \leq \tfrac{1}{2} K(w_1), \qquad |\mathrm{d}_2 \mathcal F[w_1,w_2]|_{\mathcal L(\mathcal W_2,\mathcal W_2)} \leq \tfrac{1}{3}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

|\mathcal F(w_1,0)|_{\mathcal W_2} \leq \tfrac{1}{2} K(w_1), \qquad |\mathrm{d}_2 \mathcal F[w_1,w_2]|_{\mathcal L(\mathcal W_2,\mathcal W_2)} \leq \tfrac{1}{3}

\end{equation*}for all  $(w_1,w_2) \in \overline{B}_1(0) \times \overline{B}_{K(w_1)}(0)$. The fixed-point equation

$(w_1,w_2) \in \overline{B}_1(0) \times \overline{B}_{K(w_1)}(0)$. The fixed-point equation

has for each ![]() $w_1 \in \overline{B}_1(0)$ a unique solution

$w_1 \in \overline{B}_1(0)$ a unique solution  $w_2 = w_2(w_1) \in \overline{B}_{K(w_1)}(0)$. Moreover,

$w_2 = w_2(w_1) \in \overline{B}_{K(w_1)}(0)$. Moreover, ![]() $w_2$ is a smooth function of

$w_2$ is a smooth function of ![]() $w_1$ and satisfies

$w_1$ and satisfies

Write (3.2) as

where

\begin{equation}

\mathcal F(u_1,u_2) = -n(\mathbf{D})^{-1} {(1-\chi(\mathbf{D}) ) \left( \varepsilon^2 u_2 + (u_1 + u_2)^2 \right)};

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\mathcal F(u_1,u_2) = -n(\mathbf{D})^{-1} {(1-\chi(\mathbf{D}) ) \left( \varepsilon^2 u_2 + (u_1 + u_2)^2 \right)};

\end{equation}the following mapping property of ![]() $\mathcal F$ follows from Propositions 2.4(ii) and 2.5.

$\mathcal F$ follows from Propositions 2.4(ii) and 2.5.

Proposition 3.2. Equation (3.4) defines a smooth mapping ![]() $\mathcal F\colon X_1 \times X_2 \to X_2$.

$\mathcal F\colon X_1 \times X_2 \to X_2$.

Lemma 3.3. Define ![]() $U = \{u_1 \in X_1\colon |u_1|_\varepsilon \leq 1\}$. Equation (3.3) defines a map

$U = \{u_1 \in X_1\colon |u_1|_\varepsilon \leq 1\}$. Equation (3.3) defines a map

which satisfies

\begin{equation*}|u_2(u_1)|_{X_2} \lesssim \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon^2, \qquad |\mathrm{d} u_2[u_1]|_{\mathcal L(X_1,X_2)} \lesssim \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}|u_2(u_1)|_{X_2} \lesssim \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon^2, \qquad |\mathrm{d} u_2[u_1]|_{\mathcal L(X_1,X_2)} \lesssim \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon.\end{equation*}Proof. We apply Theorem 3.1 to Equation (3.3) with ![]() $\mathcal W_1=(X_1,|\cdot|_\varepsilon)$,

$\mathcal W_1=(X_1,|\cdot|_\varepsilon)$, ![]() $\mathcal W_2=(X_2,|\cdot|_X)$. Note that

$\mathcal W_2=(X_2,|\cdot|_X)$. Note that

\begin{align*}

\mathrm{d}_1 \mathcal F[u_1,u_2](v_1) = & -n(\mathbf{D})^{-1}{(1-\chi(\mathbf{D}) )(2(u_1+u_2)v_1)}, \nonumber \\

\mathrm{d}_2 \mathcal F[u_1,u_2](v_2) = &- n(\mathbf{D})^{-1}{(1-\chi(\mathbf{D}))(\varepsilon^2 v_2 + 2(u_1+u_2)v_2)}

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\mathrm{d}_1 \mathcal F[u_1,u_2](v_1) = & -n(\mathbf{D})^{-1}{(1-\chi(\mathbf{D}) )(2(u_1+u_2)v_1)}, \nonumber \\

\mathrm{d}_2 \mathcal F[u_1,u_2](v_2) = &- n(\mathbf{D})^{-1}{(1-\chi(\mathbf{D}))(\varepsilon^2 v_2 + 2(u_1+u_2)v_2)}

\end{align*}and

by Proposition 2.5. Using Proposition 2.6, we therefore find that

\begin{equation*}

|\mathcal F(u_1,0)|_X \lesssim |u_1^2|_Z \lesssim \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon |u_1|_X

\lesssim \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon |u_1|_{L^2} \leq \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon^2

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

|\mathcal F(u_1,0)|_X \lesssim |u_1^2|_Z \lesssim \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon |u_1|_X

\lesssim \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon |u_1|_{L^2} \leq \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon^2

\end{equation*}and

\begin{align*}

|\mathrm{d}_2 \mathcal F[u_1,u_2](v_2)|_X

&\lesssim \varepsilon^2 |v_2|_Z + |u_1 v_2|_Z + |u_2 v_2|_Z\nonumber \\

&\lesssim (\varepsilon^2 + \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon + |u_2|_X) |v_2|_{X}.

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

|\mathrm{d}_2 \mathcal F[u_1,u_2](v_2)|_X

&\lesssim \varepsilon^2 |v_2|_Z + |u_1 v_2|_Z + |u_2 v_2|_Z\nonumber \\

&\lesssim (\varepsilon^2 + \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon + |u_2|_X) |v_2|_{X}.

\end{align*} To satisfy the assumptions of Theorem 3.1, we choose ![]() $K(u_1)=\sigma \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon^2$ for a sufficiently large value of

$K(u_1)=\sigma \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon^2$ for a sufficiently large value of ![]() $\sigma \gt 0$, so that

$\sigma \gt 0$, so that

\begin{equation*}

|u_2|_X \lesssim \tfrac{1}{2}K(u_1), \qquad

|\mathrm{d}_2 \mathcal F[u_1,u_2]|_{\mathcal L(X_2,X_2)} \lesssim \varepsilon

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

|u_2|_X \lesssim \tfrac{1}{2}K(u_1), \qquad

|\mathrm{d}_2 \mathcal F[u_1,u_2]|_{\mathcal L(X_2,X_2)} \lesssim \varepsilon

\end{equation*}for  $(u_1,u_2) \in U \times \overline{B}_{K(u_1)}(0)$. The theorem asserts the existence of a unique solution

$(u_1,u_2) \in U \times \overline{B}_{K(u_1)}(0)$. The theorem asserts the existence of a unique solution  $u_2(u_1) \in \overline{B}_{K(u_1)}(0)$ of (3.3) for each

$u_2(u_1) \in \overline{B}_{K(u_1)}(0)$ of (3.3) for each ![]() $u_1 \in U$ which satisfies

$u_1 \in U$ which satisfies

and

\begin{align*}

|\mathrm{d} u_2[u_1](v_1) |_X & \lesssim | \mathrm{d}_1 \mathcal F[u_1,u_2(u_1)] (v_1)|_X \\

&\lesssim |u_1 v_1|_Z + |u_2(u_1) v_1|_Z\nonumber \\

&\lesssim \varepsilon (|u_1|_X + |u_2(u_1)|_X) |v_1|_\varepsilon\nonumber \\

&\lesssim \varepsilon (|u_1|_\varepsilon + \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon^2) |v_1|_\varepsilon,

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

|\mathrm{d} u_2[u_1](v_1) |_X & \lesssim | \mathrm{d}_1 \mathcal F[u_1,u_2(u_1)] (v_1)|_X \\

&\lesssim |u_1 v_1|_Z + |u_2(u_1) v_1|_Z\nonumber \\

&\lesssim \varepsilon (|u_1|_X + |u_2(u_1)|_X) |v_1|_\varepsilon\nonumber \\

&\lesssim \varepsilon (|u_1|_\varepsilon + \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon^2) |v_1|_\varepsilon,

\end{align*}where we have used Proposition 2.6.

Our next result shows in particular that ![]() $u=u_1+u_2(u_1)$ belongs to

$u=u_1+u_2(u_1)$ belongs to  $H^\infty({\mathbb R}^2)=\smash{\bigcap\limits_{j=1}^\infty} H^j({\mathbb R}^2)$ for each

$H^\infty({\mathbb R}^2)=\smash{\bigcap\limits_{j=1}^\infty} H^j({\mathbb R}^2)$ for each ![]() $u_1 \in U_1$.

$u_1 \in U_1$.

Proposition 3.4. Any function ![]() $u=u_1+u_2 \in X_1 \oplus X_2$ which satisfies (3.3) belongs to

$u=u_1+u_2 \in X_1 \oplus X_2$ which satisfies (3.3) belongs to ![]() $H^\infty({\mathbb R}^2)$.

$H^\infty({\mathbb R}^2)$.

Proof. Obviously, ![]() $u_1 \in H^\infty({\mathbb R}^2)$, and to show that

$u_1 \in H^\infty({\mathbb R}^2)$, and to show that ![]() $u_2$ is also smooth, we abandon the fixed regularity index in the spaces

$u_2$ is also smooth, we abandon the fixed regularity index in the spaces ![]() $X$ and

$X$ and ![]() $Z$ and state it explicitly as a variable parameter. Since

$Z$ and state it explicitly as a variable parameter. Since ![]() $H^{s}({\mathbb R}^2)$ is an algebra for

$H^{s}({\mathbb R}^2)$ is an algebra for  $s \gt \frac{3}{2}$ and

$s \gt \frac{3}{2}$ and  $X^s \hookrightarrow

(1-\chi(D))H^s({\mathbb R}^2) \hookrightarrow Z_2^{s+\frac{1}{2}}$ (see Proposition 2.1), the mapping

$X^s \hookrightarrow

(1-\chi(D))H^s({\mathbb R}^2) \hookrightarrow Z_2^{s+\frac{1}{2}}$ (see Proposition 2.1), the mapping

\begin{equation*}

X_1 \oplus X_2^{s} \ni (u_1, u_2) \mapsto -(1-\chi(\mathbf{D}) ) \left( \varepsilon^2 u_2 + (u_1 + u_2)^2 \right) \in Z_2^{s+\frac{1}{2}}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

X_1 \oplus X_2^{s} \ni (u_1, u_2) \mapsto -(1-\chi(\mathbf{D}) ) \left( \varepsilon^2 u_2 + (u_1 + u_2)^2 \right) \in Z_2^{s+\frac{1}{2}}

\end{equation*}is continuous. It follows that  $u_2 \in X_2^{s+\frac{1}{2}}$, because

$u_2 \in X_2^{s+\frac{1}{2}}$, because ![]() $n(\mathbf{D})$ is an isomorphism

$n(\mathbf{D})$ is an isomorphism  $X_2^{s+\frac{1}{2}} \to Z_2^{s+\frac{1}{2}}$ by Proposition 2.5. Bootstrapping this argument yields

$X_2^{s+\frac{1}{2}} \to Z_2^{s+\frac{1}{2}}$ by Proposition 2.5. Bootstrapping this argument yields  $u_2 \in X_2^s \subset H^s({\mathbb R}^2)$ for any

$u_2 \in X_2^s \subset H^s({\mathbb R}^2)$ for any ![]() $s \in {\mathbb R}$.

$s \in {\mathbb R}$.

The next step is to substitute ![]() $u_2=u_2(u_1)$ into Equation (3.1) to obtain the reduced equation

$u_2=u_2(u_1)$ into Equation (3.1) to obtain the reduced equation

for ![]() $u_1$. We can write this equation as

$u_1$. We can write this equation as

\begin{equation*}

\varepsilon^2 u_1 + n(\mathbf{D}) u_1 {+} \chi(\mathbf{D})u_1^2 + R_\varepsilon(u_1)=0,

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\varepsilon^2 u_1 + n(\mathbf{D}) u_1 {+} \chi(\mathbf{D})u_1^2 + R_\varepsilon(u_1)=0,

\end{equation*}where

\begin{equation}

R_\varepsilon(u_1)=\chi(\mathbf{D}) \big(2u_1u_2(u_1) + u_2(u_1)^2\big).

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

R_\varepsilon(u_1)=\chi(\mathbf{D}) \big(2u_1u_2(u_1) + u_2(u_1)^2\big).

\end{equation}Proposition 3.5. The function ![]() $R_\varepsilon\colon U \subseteq X_1 \rightarrow Z_1$ satisfies the estimates

$R_\varepsilon\colon U \subseteq X_1 \rightarrow Z_1$ satisfies the estimates

\begin{equation*}|R_\varepsilon(u_1)|_{L^2} \lesssim \varepsilon^2 |u_1|_\varepsilon^3, \qquad |\mathrm{d} R_\varepsilon[u_1]|_{\mathcal L(X_1,L^2({\mathbb R}^2))} \lesssim \varepsilon^2 |u_1|_\varepsilon^2.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}|R_\varepsilon(u_1)|_{L^2} \lesssim \varepsilon^2 |u_1|_\varepsilon^3, \qquad |\mathrm{d} R_\varepsilon[u_1]|_{\mathcal L(X_1,L^2({\mathbb R}^2))} \lesssim \varepsilon^2 |u_1|_\varepsilon^2.\end{equation*}Proof. By using Proposition 2.6 and Lemma 3.3, it follows from (3.5) that

\begin{align*}

|R_\varepsilon(u_1)|_{L^2} &\lesssim |u_1 u_2(u_1)|_Z + |u_2(u_1)^2|_Z \\

& \lesssim \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon |u_2(u_1)|_X + |u_2(u_1)|_X^2 \\

& \lesssim \varepsilon^2 |u_1|_\varepsilon^3,

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

|R_\varepsilon(u_1)|_{L^2} &\lesssim |u_1 u_2(u_1)|_Z + |u_2(u_1)^2|_Z \\

& \lesssim \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon |u_2(u_1)|_X + |u_2(u_1)|_X^2 \\

& \lesssim \varepsilon^2 |u_1|_\varepsilon^3,

\end{align*}and from

that

\begin{align*}

|\mathrm{d} R_\varepsilon[u_1](v_1) |_{L^2} &\lesssim |v_1 u_2(u_1)|_Z + |u_1 \mathrm{d} u_2[u_1](v_1) |_Z + |u_2(u_1)\mathrm{d} u_2[u_1](v_1)|_Z \\

& \lesssim \varepsilon |v_1|_\varepsilon |u_2(u_1)|_X + \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon |\mathrm{d} u_2[u_1](v_1))|_X + |u_2(u_1)|_X|\mathrm{d} u_2[u_1](v_1)|_X\\

& \lesssim \varepsilon^2 |u_1|_\varepsilon^2 |v_1|_\varepsilon.

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

|\mathrm{d} R_\varepsilon[u_1](v_1) |_{L^2} &\lesssim |v_1 u_2(u_1)|_Z + |u_1 \mathrm{d} u_2[u_1](v_1) |_Z + |u_2(u_1)\mathrm{d} u_2[u_1](v_1)|_Z \\

& \lesssim \varepsilon |v_1|_\varepsilon |u_2(u_1)|_X + \varepsilon |u_1|_\varepsilon |\mathrm{d} u_2[u_1](v_1))|_X + |u_2(u_1)|_X|\mathrm{d} u_2[u_1](v_1)|_X\\

& \lesssim \varepsilon^2 |u_1|_\varepsilon^2 |v_1|_\varepsilon.

\end{align*}The reduction is completed by introducing the KP scaling

noting that ![]() $I\colon u_1 \mapsto \zeta$ is an isomorphism

$I\colon u_1 \mapsto \zeta$ is an isomorphism ![]() $X_1 \rightarrow Y_\varepsilon^1$ and

$X_1 \rightarrow Y_\varepsilon^1$ and ![]() $Z_1 \rightarrow Y_\varepsilon^0$ and choosing

$Z_1 \rightarrow Y_\varepsilon^0$ and choosing ![]() $M \gt 1$ large enough so that

$M \gt 1$ large enough so that ![]() $\zeta_k^\star \in B_M(0)$ (and

$\zeta_k^\star \in B_M(0)$ (and ![]() $\varepsilon \lt M^{-2}$, so that

$\varepsilon \lt M^{-2}$, so that ![]() $B_M(0) \subseteq Y_\varepsilon^1$ is contained in

$B_M(0) \subseteq Y_\varepsilon^1$ is contained in ![]() $I[U]=B_{\varepsilon^{\smash{-\frac{1}{2}}}}(0)\subseteq Y_\varepsilon^1$). Here we have replaced

$I[U]=B_{\varepsilon^{\smash{-\frac{1}{2}}}}(0)\subseteq Y_\varepsilon^1$). Here we have replaced ![]() $(Z_1,|\cdot|_{L^2})$ by the identical space

$(Z_1,|\cdot|_{L^2})$ by the identical space ![]() $(Y_\varepsilon^0, |\cdot|_{Y^0})$ in order to work exclusively with the scales

$(Y_\varepsilon^0, |\cdot|_{Y^0})$ in order to work exclusively with the scales ![]() $\{Y^r,|\cdot|_{Y^r}\}_{r \geq 0}$ and

$\{Y^r,|\cdot|_{Y^r}\}_{r \geq 0}$ and ![]() $\{Y_\varepsilon^r,|\cdot|_{Y^r}\}_{r \geq 0}$ of function spaces. We find that

$\{Y_\varepsilon^r,|\cdot|_{Y^r}\}_{r \geq 0}$ of function spaces. We find that ![]() $\zeta \in B_M(0) \subseteq Y_\varepsilon^1$ satisfies the equation

$\zeta \in B_M(0) \subseteq Y_\varepsilon^1$ satisfies the equation

which now holds in ![]() $Y_\varepsilon^0$, where

$Y_\varepsilon^0$, where

and ![]() $S_\varepsilon\colon B_M(0) \subseteq Y_\varepsilon^1 \rightarrow Y_\varepsilon^0$ satisfies the estimates

$S_\varepsilon\colon B_M(0) \subseteq Y_\varepsilon^1 \rightarrow Y_\varepsilon^0$ satisfies the estimates

\begin{equation}

|S_\varepsilon(\zeta)|_{Y^0} \lesssim \varepsilon | \zeta |_{Y^1}^3, \quad

|\mathrm{d} S_\varepsilon[\zeta]|_{\mathcal L(Y^1,Y^0)}\lesssim \varepsilon| \zeta |_{Y^1}^2.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

|S_\varepsilon(\zeta)|_{Y^0} \lesssim \varepsilon | \zeta |_{Y^1}^3, \quad

|\mathrm{d} S_\varepsilon[\zeta]|_{\mathcal L(Y^1,Y^0)}\lesssim \varepsilon| \zeta |_{Y^1}^2.

\end{equation} Note that  $|u_1|_\varepsilon^2=\varepsilon |\zeta|_{Y^1}^2$ and that the change of variables from

$|u_1|_\varepsilon^2=\varepsilon |\zeta|_{Y^1}^2$ and that the change of variables from ![]() $(x,y)$ to

$(x,y)$ to ![]() $(\varepsilon x, \varepsilon^2y)$ introduces a further factor of

$(\varepsilon x, \varepsilon^2y)$ introduces a further factor of ![]() $\varepsilon^{\frac{3}{2}}$ in the remainder term.

$\varepsilon^{\frac{3}{2}}$ in the remainder term.

Finally, observe that the FDKP equation

is invariant under ![]() $u(x,y) \mapsto u(-x,y)$ and

$u(x,y) \mapsto u(-x,y)$ and ![]() $u(x,y) \mapsto u(x,-y)$ and the reduction procedure preserves this invariance: Equation (3.6) is invariant under

$u(x,y) \mapsto u(x,-y)$ and the reduction procedure preserves this invariance: Equation (3.6) is invariant under ![]() $\zeta(x,y) \mapsto \zeta(-x,y)$ and

$\zeta(x,y) \mapsto \zeta(-x,y)$ and ![]() $\zeta(x,y) \mapsto \zeta(x,-y)$.

$\zeta(x,y) \mapsto \zeta(x,-y)$.

4. Solution of the reduced equation

In this section, we construct solitary-wave solutions of the reduced equation (3.6), noting that in the formal limit ![]() $\varepsilon \rightarrow 0$ it reduces to the KP equation (1.5), which has explicit (symmetric) solitary-wave solutions

$\varepsilon \rightarrow 0$ it reduces to the KP equation (1.5), which has explicit (symmetric) solitary-wave solutions ![]() $\zeta_k^\star$. For this purpose, we use a perturbation argument, rewriting (3.6) as a fixed-point equation and applying the following variant of the implicit-function theorem. It is necessary to use a low regularity version of the implicit-function theorem since the reduction in Section 3 is performed using the

$\zeta_k^\star$. For this purpose, we use a perturbation argument, rewriting (3.6) as a fixed-point equation and applying the following variant of the implicit-function theorem. It is necessary to use a low regularity version of the implicit-function theorem since the reduction in Section 3 is performed using the ![]() $\varepsilon$-dependent norm

$\varepsilon$-dependent norm ![]() $|\cdot|_\varepsilon$ and thus does not yield information concerning the smoothness of

$|\cdot|_\varepsilon$ and thus does not yield information concerning the smoothness of ![]() $u_1$ as a function of

$u_1$ as a function of ![]() $\varepsilon$.

$\varepsilon$.

Theorem 4.1. Let ![]() $\mathcal W$ be a Banach space,

$\mathcal W$ be a Banach space, ![]() $W_0$ and

$W_0$ and ![]() $\Lambda_0$ be open neighbourhoods of respectively

$\Lambda_0$ be open neighbourhoods of respectively ![]() $w^\star$ in

$w^\star$ in ![]() $\mathcal W$ and the origin in

$\mathcal W$ and the origin in ![]() ${\mathbb R}$, and

${\mathbb R}$, and ![]() $\mathcal G\colon W_0 \times \Lambda_0 \rightarrow \mathcal W$ be a function which is differentiable with respect to

$\mathcal G\colon W_0 \times \Lambda_0 \rightarrow \mathcal W$ be a function which is differentiable with respect to ![]() $w \in W_0$ for each

$w \in W_0$ for each ![]() $\lambda \in \Lambda_0$. Furthermore, suppose that

$\lambda \in \Lambda_0$. Furthermore, suppose that ![]() $\mathcal G(w^\star,0)=0$,

$\mathcal G(w^\star,0)=0$, ![]() $\mathrm{d}_1\mathcal G[w^\star,0]\colon \mathcal W \rightarrow \mathcal W$ is an isomorphism,

$\mathrm{d}_1\mathcal G[w^\star,0]\colon \mathcal W \rightarrow \mathcal W$ is an isomorphism,

\begin{equation*}

\lim_{w \rightarrow w^\star}|\mathrm{d}_1\mathcal G[w, 0]-\mathrm{d}_1\mathcal G[w^\star,0]|_{\mathcal L(\mathcal W,\mathcal W)}=0

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\lim_{w \rightarrow w^\star}|\mathrm{d}_1\mathcal G[w, 0]-\mathrm{d}_1\mathcal G[w^\star,0]|_{\mathcal L(\mathcal W,\mathcal W)}=0

\end{equation*}and

\begin{equation*}\lim_{\lambda \rightarrow 0} |\mathcal G(w,\lambda)-\mathcal G(w,0)|_{\mathcal W}=0, \quad \lim_{\lambda \rightarrow 0} \

|\mathrm{d}_1\mathcal G[w,\lambda]-\mathrm{d}_1\mathcal G[w,0]|_{\mathcal L(\mathcal W,\mathcal W)}=0\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\lim_{\lambda \rightarrow 0} |\mathcal G(w,\lambda)-\mathcal G(w,0)|_{\mathcal W}=0, \quad \lim_{\lambda \rightarrow 0} \

|\mathrm{d}_1\mathcal G[w,\lambda]-\mathrm{d}_1\mathcal G[w,0]|_{\mathcal L(\mathcal W,\mathcal W)}=0\end{equation*}uniformly over ![]() $w \in W_0$.

$w \in W_0$.

There exist open neighbourhoods ![]() $W \subseteq W_0$ of

$W \subseteq W_0$ of ![]() $w^\star$ in

$w^\star$ in ![]() $\mathcal W$ and

$\mathcal W$ and ![]() $\Lambda \subseteq \Lambda_0$ of the origin in

$\Lambda \subseteq \Lambda_0$ of the origin in ![]() ${\mathbb R}$, and a uniquely determined mapping

${\mathbb R}$, and a uniquely determined mapping ![]() $h\colon \Lambda \rightarrow W$ with the properties that

$h\colon \Lambda \rightarrow W$ with the properties that

(i)

$h$ is continuous at the origin with

$h$ is continuous at the origin with  $h(0)=w^\star$,

$h(0)=w^\star$,(ii)

$\mathcal G(h(\lambda),\lambda)=0$ for all

$\mathcal G(h(\lambda),\lambda)=0$ for all  $\lambda \in \Lambda$,

$\lambda \in \Lambda$,(iii)

$w=h(\lambda)$ whenever

$w=h(\lambda)$ whenever  $(w,\lambda) \in W \times \Lambda$ satisfies

$(w,\lambda) \in W \times \Lambda$ satisfies  $\mathcal G(w,\lambda)=0$.

$\mathcal G(w,\lambda)=0$.

Our main result is the following theorem, which is proved by reformulating Equation (3.6) in an appropriately chosen function space and verifying that it satisfies the assumptions of Theorem 4.1 through a series of auxiliary results.

Theorem 4.2. Fix  $\theta \in (\frac{1}{2},1)$. For each sufficiently small value of

$\theta \in (\frac{1}{2},1)$. For each sufficiently small value of ![]() $\varepsilon \gt 0$, Equation (3.6) has a small-amplitude, symmetric solution

$\varepsilon \gt 0$, Equation (3.6) has a small-amplitude, symmetric solution ![]() $\zeta_k^\varepsilon$ in

$\zeta_k^\varepsilon$ in ![]() $Y_\varepsilon^{1+\theta}$ with

$Y_\varepsilon^{1+\theta}$ with ![]() $|\zeta_k^\varepsilon-\zeta_k^\star|_{Y^{1+\theta}} \rightarrow 0$ as

$|\zeta_k^\varepsilon-\zeta_k^\star|_{Y^{1+\theta}} \rightarrow 0$ as ![]() $\varepsilon \rightarrow 0$.

$\varepsilon \rightarrow 0$.

The first step in the proof of Theorem 4.2 is to write (3.6) as the fixed-point equation

\begin{equation}

\zeta+\varepsilon^2\big(n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})+\varepsilon^2\big)^{-1}

\big(\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})\zeta^2+S_\varepsilon(\zeta)\big)=0

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\zeta+\varepsilon^2\big(n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})+\varepsilon^2\big)^{-1}

\big(\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})\zeta^2+S_\varepsilon(\zeta)\big)=0

\end{equation}and use the following results to ‘replace’  $\varepsilon^2\left(n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})+\varepsilon^2\right)^{-1}$ with

$\varepsilon^2\left(n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})+\varepsilon^2\right)^{-1}$ with ![]() $\tilde{m}(\mathbf{D})^{-1}$.

$\tilde{m}(\mathbf{D})^{-1}$.

Proposition 4.3. The inequality

\begin{equation*}\left|\frac{\varepsilon^2}{\varepsilon^2 + n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{k})}- \frac{1}{\tilde{m}(\mathbf{k})}\right| \lesssim \frac{\varepsilon}{\big(1+|(k_1,\frac{k_2}{k_1})|^2\big)^{1/2}}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\left|\frac{\varepsilon^2}{\varepsilon^2 + n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{k})}- \frac{1}{\tilde{m}(\mathbf{k})}\right| \lesssim \frac{\varepsilon}{\big(1+|(k_1,\frac{k_2}{k_1})|^2\big)^{1/2}}\end{equation*}holds uniformly over  $|k_1|, |\tfrac{k_2}{k_1}| \lt \frac{\delta}{\varepsilon}$.

$|k_1|, |\tfrac{k_2}{k_1}| \lt \frac{\delta}{\varepsilon}$.

Proof. Recall that  $\beta \gt \frac{1}{3}$. Clearly

$\beta \gt \frac{1}{3}$. Clearly

\begin{equation*}

\left|\frac{\varepsilon^2}{\varepsilon^2 + n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{k})}- \frac{1}{\tilde{m}(\mathbf{k})}\right|

=\frac{\left|n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{k})-(\beta-\tfrac{1}{3})\varepsilon^2 k_1^2-\varepsilon^2\tfrac{k_2^2}{k_1^2}\right|}{(\varepsilon^2 + n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{k}))

\left(1+(\beta-\tfrac{1}{3})k_1^2+\tfrac{k_2^2}{k_1^2}\right)}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\left|\frac{\varepsilon^2}{\varepsilon^2 + n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{k})}- \frac{1}{\tilde{m}(\mathbf{k})}\right|

=\frac{\left|n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{k})-(\beta-\tfrac{1}{3})\varepsilon^2 k_1^2-\varepsilon^2\tfrac{k_2^2}{k_1^2}\right|}{(\varepsilon^2 + n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{k}))

\left(1+(\beta-\tfrac{1}{3})k_1^2+\tfrac{k_2^2}{k_1^2}\right)}.

\end{equation*} Furthermore, since ![]() $n(s)$ is an analytic function of

$n(s)$ is an analytic function of ![]() $s_1$ and

$s_1$ and ![]() $\tfrac{s_2}{s_1}$, we have that

$\tfrac{s_2}{s_1}$, we have that

\begin{equation*}

\left|n(s)-\left(\beta-\frac{1}{3}\right)s_1^2-\frac{s_2^2}{s_1^2}\right|\lesssim \left|\left(s_1,\frac{s_2}{s_1}\right)\right|^3\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\left|n(s)-\left(\beta-\frac{1}{3}\right)s_1^2-\frac{s_2^2}{s_1^2}\right|\lesssim \left|\left(s_1,\frac{s_2}{s_1}\right)\right|^3\end{equation*}and by the definition of ![]() $n$ that

$n$ that

\begin{equation*}

n(s) \gt rsim \left|\left(s_1,\frac{s_2}{s_1}\right)\right|^2\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

n(s) \gt rsim \left|\left(s_1,\frac{s_2}{s_1}\right)\right|^2\end{equation*}for  $|(s_1,\tfrac{s_2}{s_1})| \leq \delta$. It follows that

$|(s_1,\tfrac{s_2}{s_1})| \leq \delta$. It follows that

\begin{equation*}

\left|\frac{\varepsilon^2}{\varepsilon^2 + n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{k})}- \frac{1}{\tilde{m}(\mathbf{k})}\right|

\lesssim

\frac{\varepsilon |(k_1,\frac{k_2}{k_1})|^3}{(1+|(k_1,\frac{k_2}{k_1})|^2)^2}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\left|\frac{\varepsilon^2}{\varepsilon^2 + n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{k})}- \frac{1}{\tilde{m}(\mathbf{k})}\right|

\lesssim

\frac{\varepsilon |(k_1,\frac{k_2}{k_1})|^3}{(1+|(k_1,\frac{k_2}{k_1})|^2)^2}

\end{equation*}uniformly over  $|k_1|, |\tfrac{k_2}{k_1}| \lt \frac{\delta}{\varepsilon}$.

$|k_1|, |\tfrac{k_2}{k_1}| \lt \frac{\delta}{\varepsilon}$.

Corollary 4.4. For each ![]() $\theta \in [0,1]$, the inequality

$\theta \in [0,1]$, the inequality

\begin{equation*}\left|\frac{\varepsilon^2}{\varepsilon^2 + n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{k})}- \frac{1}{\tilde{m}(\mathbf{k})}\right| \lesssim \frac{\varepsilon^{1-\theta}}{(1+|(k_1,\frac{k_2}{k_1})|^2)^{\frac{1}{2}(1+\theta)}}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\left|\frac{\varepsilon^2}{\varepsilon^2 + n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{k})}- \frac{1}{\tilde{m}(\mathbf{k})}\right| \lesssim \frac{\varepsilon^{1-\theta}}{(1+|(k_1,\frac{k_2}{k_1})|^2)^{\frac{1}{2}(1+\theta)}}\end{equation*}holds uniformly over  $|k_1|, |\tfrac{k_2}{k_|}| \lt \frac{\delta}{\varepsilon}$.

$|k_1|, |\tfrac{k_2}{k_|}| \lt \frac{\delta}{\varepsilon}$.

Proof. This result follows from Proposition 4.3 and the observation that  $\varepsilon \lesssim \delta(1+|(k_1,\frac{k_2}{k_2})|^2)^{-\frac{1}{2}}$ for

$\varepsilon \lesssim \delta(1+|(k_1,\frac{k_2}{k_2})|^2)^{-\frac{1}{2}}$ for  $|k_1|, |\tfrac{k_2}{k_1}| \lt \frac{\delta}{\varepsilon}$.

$|k_1|, |\tfrac{k_2}{k_1}| \lt \frac{\delta}{\varepsilon}$.

Using Corollary 4.4, one can write Equation (4.1) as

in which

\begin{equation*}

F_\varepsilon(\zeta)= \tilde{m}(\mathbf{D})^{-1}\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})\zeta^2

+\underbrace{T_{1,\varepsilon}(\zeta)+T_{2,\varepsilon}(\zeta)}_{\displaystyle = T_\varepsilon(\zeta)}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

F_\varepsilon(\zeta)= \tilde{m}(\mathbf{D})^{-1}\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})\zeta^2

+\underbrace{T_{1,\varepsilon}(\zeta)+T_{2,\varepsilon}(\zeta)}_{\displaystyle = T_\varepsilon(\zeta)}

\end{equation*}and

\begin{equation*}

T_{1,\varepsilon}(\zeta) = \left(\varepsilon^2\big(n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})+\varepsilon^2\big)^{-1}-\tilde{m}(\mathbf{D})^{-1}\right)\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})\zeta^2,

\qquad

T_{2,\varepsilon}(\zeta) =

\varepsilon^2\big(n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})+\varepsilon^2\big)^{-1}S_\varepsilon(\zeta).

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

T_{1,\varepsilon}(\zeta) = \left(\varepsilon^2\big(n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})+\varepsilon^2\big)^{-1}-\tilde{m}(\mathbf{D})^{-1}\right)\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})\zeta^2,

\qquad

T_{2,\varepsilon}(\zeta) =

\varepsilon^2\big(n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})+\varepsilon^2\big)^{-1}S_\varepsilon(\zeta).

\end{equation*}Proposition 4.5. Fix ![]() $\theta \in [0,1]$. The mapping

$\theta \in [0,1]$. The mapping ![]() $T_\varepsilon\colon B_M(0) \subseteq Y_\varepsilon^1 \rightarrow Y_\varepsilon^{1+\theta}$ satisfies

$T_\varepsilon\colon B_M(0) \subseteq Y_\varepsilon^1 \rightarrow Y_\varepsilon^{1+\theta}$ satisfies

\begin{equation*}

|T_\varepsilon(\zeta)|_{Y^{1+\theta}} \lesssim \varepsilon^{1-\theta} | \zeta |_{Y^1}^2, \quad

|\mathrm{d} T_\varepsilon[\zeta]|_{\mathcal L(Y^1,Y^{1+\theta})}\lesssim \varepsilon^{1-\theta}| \zeta |_{Y^1}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

|T_\varepsilon(\zeta)|_{Y^{1+\theta}} \lesssim \varepsilon^{1-\theta} | \zeta |_{Y^1}^2, \quad

|\mathrm{d} T_\varepsilon[\zeta]|_{\mathcal L(Y^1,Y^{1+\theta})}\lesssim \varepsilon^{1-\theta}| \zeta |_{Y^1}

\end{equation*}for all ![]() $\zeta \in Y_\varepsilon^{1+\theta}$.

$\zeta \in Y_\varepsilon^{1+\theta}$.

Proof. The result for ![]() $T_{1,\varepsilon}$ follows from the calculation

$T_{1,\varepsilon}$ follows from the calculation

\begin{equation*}\left|\left(\varepsilon^2\big(n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})+\varepsilon^2\big)^{-1}\!\!-\tilde{m}(\mathbf{D})^{-1}\right)\!\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})\zeta\rho\right|_{Y^{1+\theta}}

\!\!\lesssim\! \varepsilon^{1-\theta}|\zeta\rho|_0 \!\lesssim\! \varepsilon^{1-\theta}|\zeta|_{L^4} |\rho|_{L^4} \!\lesssim\! \varepsilon^{1-\theta}|\zeta|_{Y^{1+\theta}}|\rho|_{Y^{1+\theta}}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\left|\left(\varepsilon^2\big(n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})+\varepsilon^2\big)^{-1}\!\!-\tilde{m}(\mathbf{D})^{-1}\right)\!\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})\zeta\rho\right|_{Y^{1+\theta}}

\!\!\lesssim\! \varepsilon^{1-\theta}|\zeta\rho|_0 \!\lesssim\! \varepsilon^{1-\theta}|\zeta|_{L^4} |\rho|_{L^4} \!\lesssim\! \varepsilon^{1-\theta}|\zeta|_{Y^{1+\theta}}|\rho|_{Y^{1+\theta}}\end{equation*}for all ![]() $\zeta$,

$\zeta$, ![]() $\rho \in Y_\varepsilon^{1+\theta}$ (see Corollary 4.4 and Proposition 2.2(i)). Corollary 4.4 (with

$\rho \in Y_\varepsilon^{1+\theta}$ (see Corollary 4.4 and Proposition 2.2(i)). Corollary 4.4 (with ![]() $\theta=1$) also yields

$\theta=1$) also yields

\begin{equation*}

\frac{\varepsilon^2}{n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{k})+\varepsilon^2} \lesssim \left(1+k_1^2+\frac{k_2^2}{k_1^2}\right)^{-1},

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\frac{\varepsilon^2}{n_\varepsilon(\mathbf{k})+\varepsilon^2} \lesssim \left(1+k_1^2+\frac{k_2^2}{k_1^2}\right)^{-1},

\end{equation*}and the result for ![]() $T_{2,\varepsilon}$ follows from this estimate and (3.7).

$T_{2,\varepsilon}$ follows from this estimate and (3.7).

Remark 4.6. We can also consider ![]() $T_\varepsilon$ as a mapping

$T_\varepsilon$ as a mapping ![]() $T_\varepsilon\colon B_M(0) \subseteq Y_\varepsilon^{1+\theta} \rightarrow Y_\varepsilon^{1+\theta}$ with identical estimates since

$T_\varepsilon\colon B_M(0) \subseteq Y_\varepsilon^{1+\theta} \rightarrow Y_\varepsilon^{1+\theta}$ with identical estimates since ![]() $\{Y_\varepsilon^r,|\cdot|_{Y^r}\}_{r \geq 0}$ is a scale of Banach spaces.

$\{Y_\varepsilon^r,|\cdot|_{Y^r}\}_{r \geq 0}$ is a scale of Banach spaces.

It is convenient to replace Equation (4.2) with

where ![]() $G_\varepsilon(\zeta) = F_\varepsilon(\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})\zeta)$, and study it in the fixed space

$G_\varepsilon(\zeta) = F_\varepsilon(\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})\zeta)$, and study it in the fixed space ![]() $Y^{1+\theta}$ for

$Y^{1+\theta}$ for  $\theta\in(\frac{1}{2},1)$ (the solution sets of the two equations evidently coincide); we choose

$\theta\in(\frac{1}{2},1)$ (the solution sets of the two equations evidently coincide); we choose  $\theta \gt \frac{1}{2}$ so that

$\theta \gt \frac{1}{2}$ so that ![]() $Y^{1+\theta}$ is embedded in

$Y^{1+\theta}$ is embedded in ![]() $C_\mathrm{b}({\mathbb R}^2)$ and

$C_\mathrm{b}({\mathbb R}^2)$ and ![]() $\theta \lt 1$ so that

$\theta \lt 1$ so that ![]() $T_\varepsilon(\zeta)$ vanishes in the limit

$T_\varepsilon(\zeta)$ vanishes in the limit ![]() $\varepsilon \rightarrow 0$. Note that the regularity index

$\varepsilon \rightarrow 0$. Note that the regularity index ![]() $s$ for the space

$s$ for the space ![]() $X$ must be taken larger than

$X$ must be taken larger than ![]() $r = 1+\theta$ to preserve the embedding

$r = 1+\theta$ to preserve the embedding ![]() $X \hookrightarrow Y^r$ (see Lemma 2.1); in fact, all desired properties are satisfied for

$X \hookrightarrow Y^r$ (see Lemma 2.1); in fact, all desired properties are satisfied for  $\tfrac{3}{2} \lt 1 + \theta \lt s \lt 2$. We establish Theorem 4.2 by applying Theorem 4.1 with

$\tfrac{3}{2} \lt 1 + \theta \lt s \lt 2$. We establish Theorem 4.2 by applying Theorem 4.1 with

![]() $W_0=B_M(0)\subseteq Y_\mathrm{e}^{1+\theta}$,

$W_0=B_M(0)\subseteq Y_\mathrm{e}^{1+\theta}$, ![]() $\Lambda_0=(-\varepsilon_0,\varepsilon_0)$ for a sufficiently small value of

$\Lambda_0=(-\varepsilon_0,\varepsilon_0)$ for a sufficiently small value of ![]() $\varepsilon_0$, and

$\varepsilon_0$, and

where ![]() $\varepsilon$ has been replaced by

$\varepsilon$ has been replaced by ![]() $|\varepsilon|$ to have

$|\varepsilon|$ to have ![]() $\mathcal G(\zeta,\varepsilon)$ defined for

$\mathcal G(\zeta,\varepsilon)$ defined for ![]() $\varepsilon$ in a full neighbourhood of the origin in

$\varepsilon$ in a full neighbourhood of the origin in ![]() ${\mathbb R}$.

${\mathbb R}$.

We begin by verifying that the functions ![]() $\zeta_k^\star$ belong to

$\zeta_k^\star$ belong to ![]() $Y_\mathrm{e}^{1+\theta}$.

$Y_\mathrm{e}^{1+\theta}$.

Proposition 4.7. Each KP lump solution ![]() $\zeta_k^\star$ belongs to

$\zeta_k^\star$ belongs to ![]() $Y^2$.

$Y^2$.

Proof. First note that  $(\zeta_k^\star)^2$ belongs to

$(\zeta_k^\star)^2$ belongs to ![]() $L^2({\mathbb R}^2)=Y^0$ because

$L^2({\mathbb R}^2)=Y^0$ because  $|\zeta_k^\star(x,y)| \lesssim (1+x^2+y^2)^{-1}$ for all

$|\zeta_k^\star(x,y)| \lesssim (1+x^2+y^2)^{-1}$ for all ![]() $(x,y) \in {\mathbb R}^2$ (see Proposition 1.1(i)). Since

$(x,y) \in {\mathbb R}^2$ (see Proposition 1.1(i)). Since ![]() $\zeta_k^\star$ satisfies

$\zeta_k^\star$ satisfies

\begin{equation*}

\zeta_k^\star+\tilde{m}(\mathbf{D})^{-1}(\zeta_k^\star)^2=0

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\zeta_k^\star+\tilde{m}(\mathbf{D})^{-1}(\zeta_k^\star)^2=0

\end{equation*}and ![]() $\tilde m(\mathbf{D})^{-1}$ is a lifting operator of order

$\tilde m(\mathbf{D})^{-1}$ is a lifting operator of order ![]() $2$ for the scale

$2$ for the scale ![]() $\{Y^r,|\cdot|_{Y^r}\}_{r \geq 0}$, one finds that

$\{Y^r,|\cdot|_{Y^r}\}_{r \geq 0}$, one finds that  $\zeta_k^\star \in Y^2$.

$\zeta_k^\star \in Y^2$.

Observe that ![]() $\mathcal G(\cdot,\varepsilon)$ is a continuously differentiable function

$\mathcal G(\cdot,\varepsilon)$ is a continuously differentiable function ![]() $B_M(0) \subseteq Y_\mathrm{e}^{1+\theta} \to Y_\mathrm{e}^{1+\theta}$ for each fixed

$B_M(0) \subseteq Y_\mathrm{e}^{1+\theta} \to Y_\mathrm{e}^{1+\theta}$ for each fixed ![]() $\varepsilon \geq 0$, so that

$\varepsilon \geq 0$, so that

\begin{equation*}

\lim_{\zeta \rightarrow \zeta_k^\star}|\mathrm{d}_1\mathcal G[\zeta, 0]-\mathrm{d}_1\mathcal G[\zeta_k^\star,0]|_{\mathcal L(Y^{1+\theta},Y^{1+\theta})}=0.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\lim_{\zeta \rightarrow \zeta_k^\star}|\mathrm{d}_1\mathcal G[\zeta, 0]-\mathrm{d}_1\mathcal G[\zeta_k^\star,0]|_{\mathcal L(Y^{1+\theta},Y^{1+\theta})}=0.

\end{equation*}The facts that

\begin{equation*}

\lim_{\varepsilon \rightarrow 0} |\mathcal G(\zeta,\varepsilon)-\mathcal G(\zeta,0)|_{Y^{1+\theta}}=0, \quad \lim_{\varepsilon \rightarrow 0} \

|\mathrm{d}_1\mathcal G[\zeta,\varepsilon]-\mathrm{d}_1\mathcal G[\zeta,0]|_{\mathcal L(Y^{1+\theta},Y^{1+\theta})}=0

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\lim_{\varepsilon \rightarrow 0} |\mathcal G(\zeta,\varepsilon)-\mathcal G(\zeta,0)|_{Y^{1+\theta}}=0, \quad \lim_{\varepsilon \rightarrow 0} \

|\mathrm{d}_1\mathcal G[\zeta,\varepsilon]-\mathrm{d}_1\mathcal G[\zeta,0]|_{\mathcal L(Y^{1+\theta},Y^{1+\theta})}=0

\end{equation*}uniformly over ![]() $\zeta \in B_M(0)\subseteq Y_\mathrm{e}^{1+\theta}$ are obtained from the equation

$\zeta \in B_M(0)\subseteq Y_\mathrm{e}^{1+\theta}$ are obtained from the equation

\begin{equation*}

\mathcal G(\zeta,\varepsilon)-\mathcal G(\zeta,0)

= \tilde{m}(\mathbf{D})^{-1}

\left(\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})

\left(\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})\zeta\right)^2-\zeta^2\right)

+ T_{|\varepsilon|}(\zeta)

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\mathcal G(\zeta,\varepsilon)-\mathcal G(\zeta,0)

= \tilde{m}(\mathbf{D})^{-1}

\left(\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})

\left(\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})\zeta\right)^2-\zeta^2\right)

+ T_{|\varepsilon|}(\zeta)

\end{equation*}using Proposition 4.5 and Corollary 4.10 below, which is a consequence of the next two lemmas.

Lemma 4.8. Fix  $\theta \gt \frac{1}{2}$. The estimate

$\theta \gt \frac{1}{2}$. The estimate

\begin{equation*}

| \tilde m(\mathbf{D})^{-1} \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) \big( (( \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) + I) \zeta) ((\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) - I) \rho)\big) |_{Y^{1+\theta}} \lesssim \varepsilon | \zeta |_{Y^{1+\theta}} | \rho |_{Y^{1+\theta}}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

| \tilde m(\mathbf{D})^{-1} \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) \big( (( \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) + I) \zeta) ((\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) - I) \rho)\big) |_{Y^{1+\theta}} \lesssim \varepsilon | \zeta |_{Y^{1+\theta}} | \rho |_{Y^{1+\theta}}

\end{equation*}holds for all ![]() $\zeta, \rho \in Y^{1+\theta}$.

$\zeta, \rho \in Y^{1+\theta}$.

Proof. Recall that ![]() $\tilde m(\mathbf{D})^{-1}$ is a lifting operator of order 2 for the scale

$\tilde m(\mathbf{D})^{-1}$ is a lifting operator of order 2 for the scale ![]() $\{Y^r,|\cdot|_{Y^r}\}_{r \geq 0}$ and that

$\{Y^r,|\cdot|_{Y^r}\}_{r \geq 0}$ and that ![]() $\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})$ is a bounded projection on

$\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D})$ is a bounded projection on ![]() $L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$. It follows that

$L^2({\mathbb R}^2)$. It follows that

\begin{align*}

| \tilde m(\mathbf{D})^{-1} & \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) \big( (( \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) + I) \zeta) ((\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) - I) \rho)\big) |_{Y^{1+\theta}}\\

&\quad\leq | \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) \big( (( \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) + I) \zeta) ((\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) - I) \rho)\big)|_{L^2}\\

&\quad \leq |(( \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) + I) \zeta) ((\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) - I) \rho) |_{L^2}\\

&\quad \leq | ( \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) + I) \zeta|_\infty | (\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) - I) \rho |_{L^2} \\

&\quad \lesssim | ( \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) + I) \zeta|_{Y^{1+\theta}}| (\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) - I) \rho |_{L^2} \\

&\quad \leq 2| \zeta|_{Y^{1+\theta}} | (\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) - I) \rho |_{L^2},

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

| \tilde m(\mathbf{D})^{-1} & \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) \big( (( \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) + I) \zeta) ((\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) - I) \rho)\big) |_{Y^{1+\theta}}\\

&\quad\leq | \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) \big( (( \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) + I) \zeta) ((\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) - I) \rho)\big)|_{L^2}\\

&\quad \leq |(( \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) + I) \zeta) ((\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) - I) \rho) |_{L^2}\\

&\quad \leq | ( \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) + I) \zeta|_\infty | (\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) - I) \rho |_{L^2} \\

&\quad \lesssim | ( \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) + I) \zeta|_{Y^{1+\theta}}| (\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) - I) \rho |_{L^2} \\

&\quad \leq 2| \zeta|_{Y^{1+\theta}} | (\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) - I) \rho |_{L^2},

\end{align*}where the last line is followed by the embedding ![]() $Y^{1+\theta} \hookrightarrow C_\mathrm{b}({\mathbb R}^2)$. To estimate

$Y^{1+\theta} \hookrightarrow C_\mathrm{b}({\mathbb R}^2)$. To estimate ![]() $| \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) - I) \zeta|_{L^2}$, note that

$| \chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) - I) \zeta|_{L^2}$, note that

\begin{equation*}

\mathbb{R}^2 \setminus C_\varepsilon \subset \underbrace{\left\{(k_1,k_2) \colon |k_1| \gt \frac{\delta}{\varepsilon}\right\}}_{\displaystyle= C_\varepsilon^1} \cup \underbrace{\left\{(k_1,k_2) \colon \left|\frac{k_2}{k_1}\right| \gt \frac{\delta}{\varepsilon}\right\}}_{\displaystyle=C_\varepsilon^2},

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\mathbb{R}^2 \setminus C_\varepsilon \subset \underbrace{\left\{(k_1,k_2) \colon |k_1| \gt \frac{\delta}{\varepsilon}\right\}}_{\displaystyle= C_\varepsilon^1} \cup \underbrace{\left\{(k_1,k_2) \colon \left|\frac{k_2}{k_1}\right| \gt \frac{\delta}{\varepsilon}\right\}}_{\displaystyle=C_\varepsilon^2},

\end{equation*}so that

\begin{align*}

| (\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) - I) \zeta |_{L^2}^2 &= \int_{\mathbb{R}^2 \setminus C_\varepsilon} |\hat \zeta|^2 \, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k} \\

& \leq \int_{C_\varepsilon^1} |\hat \zeta|^2 \, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k} + \int_{C_\varepsilon^2} |\hat \zeta|^2 \, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k}\\

&\leq \frac{\varepsilon^2}{\delta^2} \int_{C_\varepsilon^1} k_1^2 |\hat \zeta|^2 \, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k} + \frac{\varepsilon^2}{\delta^2} \int_{C_\varepsilon^2} \frac{k_2^2}{k_1^2} |\hat \zeta|^2 \, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k} \\

& \leq \frac{2\varepsilon^2}{\delta^2} | \zeta |_{Y^1}^2.

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

| (\chi_\varepsilon(\mathbf{D}) - I) \zeta |_{L^2}^2 &= \int_{\mathbb{R}^2 \setminus C_\varepsilon} |\hat \zeta|^2 \, \mathrm{d} \mathbf{k} \\