1. Introduction

Boundary layers in practical engineering applications rarely develop under ideal zero-pressure-gradient conditions. Flows over hulls, fuselages and swept wings are strongly influenced by pressure gradients and curvature of the mean streamlines. Past studies have demonstrated the importance of these effects on the development of boundary layers and the state of turbulence (Mager Reference Mager1951; Cooke Reference Cooke1958; Bradshaw & Young Reference Bradshaw and Young1973; Finnigan Reference Finnigan1983). The flow around the canonical

![]() $6 \colon\! 1$

prolate spheroid highlights the complexity of these phenomena, with interacting streamwise, crossflow and centrifugal instabilities contributing to transition. The spheroid geometry has been studied experimentally (Fu et al. Reference Fu, Shekarriz, Katz and Huang1994; Chesnakas & Simpson Reference Chesnakas and Simpson1994, Reference Chesnakas and Simpson1996, Reference Chesnakas and Simpson1997; Wetzel Reference Wetzel1996) and numerically (Hedin et al. Reference Hedin, Berglund, Alin and Fureby2001; Constantinescu et al. Reference Constantinescu, Pasinato, Wang, Forsythe and Squires2002; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Huang, Chen and Fu2007; Fureby & Karlsson Reference Fureby and Karlsson2009; Aram et al. Reference Aram, Shan and Jiang2021, Reference Aram, Shan, Jiang and Atsavapranee2022). Recently Plasseraud, Kumar & Mahesh (Reference Plasseraud, Kumar and Mahesh2023) performed a trip-resolved large-eddy simulation (LES) of the prolate spheroid flow at incidence with the same trip configuration as Chesnakas & Simpson (Reference Chesnakas and Simpson1994). These studies noted the geometry-induced pressure gradients that created a crossflow transporting momentum from the windward to the leeward side. Plasseraud et al. (Reference Plasseraud, Kumar and Mahesh2023) recorded insufficient tripping on the windward side of the spheroid due to the effect of streamline curvature. A deeper understanding of curvature effects is therefore critical for predictive modelling of turbulent boundary layers in three-dimensional (3-D) configurations.

$6 \colon\! 1$

prolate spheroid highlights the complexity of these phenomena, with interacting streamwise, crossflow and centrifugal instabilities contributing to transition. The spheroid geometry has been studied experimentally (Fu et al. Reference Fu, Shekarriz, Katz and Huang1994; Chesnakas & Simpson Reference Chesnakas and Simpson1994, Reference Chesnakas and Simpson1996, Reference Chesnakas and Simpson1997; Wetzel Reference Wetzel1996) and numerically (Hedin et al. Reference Hedin, Berglund, Alin and Fureby2001; Constantinescu et al. Reference Constantinescu, Pasinato, Wang, Forsythe and Squires2002; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Huang, Chen and Fu2007; Fureby & Karlsson Reference Fureby and Karlsson2009; Aram et al. Reference Aram, Shan and Jiang2021, Reference Aram, Shan, Jiang and Atsavapranee2022). Recently Plasseraud, Kumar & Mahesh (Reference Plasseraud, Kumar and Mahesh2023) performed a trip-resolved large-eddy simulation (LES) of the prolate spheroid flow at incidence with the same trip configuration as Chesnakas & Simpson (Reference Chesnakas and Simpson1994). These studies noted the geometry-induced pressure gradients that created a crossflow transporting momentum from the windward to the leeward side. Plasseraud et al. (Reference Plasseraud, Kumar and Mahesh2023) recorded insufficient tripping on the windward side of the spheroid due to the effect of streamline curvature. A deeper understanding of curvature effects is therefore critical for predictive modelling of turbulent boundary layers in three-dimensional (3-D) configurations.

These complex boundary layer behaviours can be studied through both experimental and numerical approaches. Experimentally, transition is often accelerated using surface tripping techniques to ensure repeatability and enable model-scale testing at Reynolds numbers relevant to full-scale flows. The design of the trip must be carefully considered such that the boundary layer successfully undergoes a complete transition to turbulence without retaining any of the specific geometric characteristics of the disturbance. Erm & Joubert (Reference Erm and Joubert1991) and Morse & Mahesh (Reference Morse and Mahesh2023) have evaluated the trip design on the DARPA SUBOFF hull, and Aram, Shan & Jiang (Reference Aram, Shan and Jiang2021) and Plasseraud et al. (Reference Plasseraud, Kumar, Ma and Mahesh2022) performed a trip design study on the

![]() $6\colon\! 1$

prolate spheroid. Various tripping methods have been utilised including, but not limited to, pockets of isotropic turbulence (Wu & Moin Reference Wu and Moin2009), isolated wall-attached cubes (Daniel, Laizet & Vassilicos Reference Daniel, Laizet and Vassilicos2017; Ma & Mahesh Reference Ma and Mahesh2022), isolated wall-attached cylinders (Bucci et al. Reference Bucci, Puckert, Andriano, Loiseau, Cherubini, Robinet and Rist2018), distributed roughness elements (Ma & Mahesh Reference Ma and Mahesh2023) and tripwires (Jiménez et al. Reference Jiménez, Hultmark and Smits2010). Numerically, the geometry of trip can be either directly resolved (Ma & Mahesh Reference Ma and Mahesh2022; Morse & Mahesh Reference Morse and Mahesh2023; Plasseraud et al. Reference Plasseraud, Kumar and Mahesh2023) or it can be mimicked with wall blowing by introducing wall-normal velocity to the corresponding near-wall control volumes (Kumar & Mahesh Reference Kumar and Mahesh2018; Morse & Mahesh Reference Morse and Mahesh2021). Schlatter & Örlü (Reference Schlatter and Örlü2012) analysed the effect of tripping on the downstream behaviour via wall-normal volume forcing at various amplitudes, temporal frequencies and spanwise length scales and found marked differences in the skin friction coefficient, shape factor and mean profiles based on the forcing characteristics. The choice of geometry and location are important parameters to assess as they can give rise to different perturbation modes that affect the downstream boundary layer evolution. The problem is further complicated when considering the addition of pressure gradient. Adverse pressure gradients are known to increase the boundary layer thickness and promote transition, whereas favourable pressure gradients have the opposite effect (Pope Reference Pope2000).

$6\colon\! 1$

prolate spheroid. Various tripping methods have been utilised including, but not limited to, pockets of isotropic turbulence (Wu & Moin Reference Wu and Moin2009), isolated wall-attached cubes (Daniel, Laizet & Vassilicos Reference Daniel, Laizet and Vassilicos2017; Ma & Mahesh Reference Ma and Mahesh2022), isolated wall-attached cylinders (Bucci et al. Reference Bucci, Puckert, Andriano, Loiseau, Cherubini, Robinet and Rist2018), distributed roughness elements (Ma & Mahesh Reference Ma and Mahesh2023) and tripwires (Jiménez et al. Reference Jiménez, Hultmark and Smits2010). Numerically, the geometry of trip can be either directly resolved (Ma & Mahesh Reference Ma and Mahesh2022; Morse & Mahesh Reference Morse and Mahesh2023; Plasseraud et al. Reference Plasseraud, Kumar and Mahesh2023) or it can be mimicked with wall blowing by introducing wall-normal velocity to the corresponding near-wall control volumes (Kumar & Mahesh Reference Kumar and Mahesh2018; Morse & Mahesh Reference Morse and Mahesh2021). Schlatter & Örlü (Reference Schlatter and Örlü2012) analysed the effect of tripping on the downstream behaviour via wall-normal volume forcing at various amplitudes, temporal frequencies and spanwise length scales and found marked differences in the skin friction coefficient, shape factor and mean profiles based on the forcing characteristics. The choice of geometry and location are important parameters to assess as they can give rise to different perturbation modes that affect the downstream boundary layer evolution. The problem is further complicated when considering the addition of pressure gradient. Adverse pressure gradients are known to increase the boundary layer thickness and promote transition, whereas favourable pressure gradients have the opposite effect (Pope Reference Pope2000).

Considerable research has been conducted on the influence of pressure gradients and curvature on turbulent boundary layers. Classic works (Rotta Reference Rotta1953; Clauser Reference Clauser1956; Townsend Reference Townsend1956) established the impact of streamwise pressure gradients on scaling laws and turbulence structure. More recent studies examined history effects (Bobke et al. Reference Bobke, Vinuesa, Örlü and Schlatter2017), structure organisation (Harun et al. Reference Harun, Monty, Mathis and Marusic2013) and combined adverse and favourable gradients (Volino Reference Volino2020a

; Kumar & Mahesh Reference Kumar and Mahesh2025). Eskinazi & Yeh (Reference Eskinazi and Yeh1956) and So & Mellor (Reference So and Mellor1975) conducted wind tunnel experiments of a boundary layer developing on a concave wall and noted substantial increases in turbulent intensities and the development of Taylor–Görtler-type instabilities, whereas convex curvature has been found to attenuate turbulence (Muck, Hoffmann & Bradshaw Reference Muck, Hoffmann and Bradshaw1985; Moser & Moin Reference Moser and Moin1987). Bradshaw (Reference Bradshaw1969) drew a connection between curvature and buoyancy in turbulent shear flows and found the effects of curvature appreciable only if the shear layer thickness is greater than

![]() $1/300{{\rm th}}$

of the radius of curvature. The presence of transverse pressure gradients drives an initially two-dimensional (2-D) boundary layer into three dimensions and creates a secondary flow with a positive gradient

$1/300{{\rm th}}$

of the radius of curvature. The presence of transverse pressure gradients drives an initially two-dimensional (2-D) boundary layer into three dimensions and creates a secondary flow with a positive gradient

![]() $\partial \overline {w} / \partial y$

(Hawthorne Reference Hawthorne1951; Squire & Winter Reference Squire and Winter1951; Johnston Reference Johnston1960). This crossflow has been long reported on swept wings (Bradshaw & Pontikos Reference Bradshaw and Pontikos1985) and is known to introduce additional instabilities (Dagenhart & Saric Reference Dagenhart and Saric1999). Direct numerical simulations (DNS) of a fully developed plane Poiseuille flow by Moin et al. (Reference Moin, Shih, Driver and Mansour1990) where the flow was suddenly exposed to a transverse pressure gradient showed a decrease in turbulence production. Mager & Hansen (Reference Mager and Hansen1952) studied laminar boundary layer development over a flat plate with small turning of the mean flow along concentric circular streamlines and derived an analytical expression for the crossflow. Similar expressions were also derived for turbulent boundary layers (Cooke Reference Cooke1958) and supersonic boundary layers (Braun Reference Braun1958). Holstad, Andersson & Pettersen (Reference Holstad, Andersson and Pettersen2010) conducted DNS of Couette–Poiseuille flow with a spanwise pressure gradient that resulted in an

$\partial \overline {w} / \partial y$

(Hawthorne Reference Hawthorne1951; Squire & Winter Reference Squire and Winter1951; Johnston Reference Johnston1960). This crossflow has been long reported on swept wings (Bradshaw & Pontikos Reference Bradshaw and Pontikos1985) and is known to introduce additional instabilities (Dagenhart & Saric Reference Dagenhart and Saric1999). Direct numerical simulations (DNS) of a fully developed plane Poiseuille flow by Moin et al. (Reference Moin, Shih, Driver and Mansour1990) where the flow was suddenly exposed to a transverse pressure gradient showed a decrease in turbulence production. Mager & Hansen (Reference Mager and Hansen1952) studied laminar boundary layer development over a flat plate with small turning of the mean flow along concentric circular streamlines and derived an analytical expression for the crossflow. Similar expressions were also derived for turbulent boundary layers (Cooke Reference Cooke1958) and supersonic boundary layers (Braun Reference Braun1958). Holstad, Andersson & Pettersen (Reference Holstad, Andersson and Pettersen2010) conducted DNS of Couette–Poiseuille flow with a spanwise pressure gradient that resulted in an

![]() $8^\circ $

turn from the original flow direction and noted that the coherent flow structures turned to align with the local mean-flow direction, giving rise to secondary and tertiary turbulent stress components. Both Moin et al. (Reference Moin, Shih, Driver and Mansour1990) and Holstad et al. (Reference Holstad, Andersson and Pettersen2010) reported misalignment of the Reynolds shear stress and velocity gradient, and this phenomenon has also been documented by Bradshaw & Pontikos (Reference Bradshaw and Pontikos1985), Chesnakas & Simpson (Reference Chesnakas and Simpson1996) and Hu, Hayat & Park (Reference Hu, Hayat and Park2023). Apart from these observations, the effect of spanwise streamline curvature on transitioning and turbulent boundary layers has seldom been formally studied, especially in an idealised fashion where the curvature of the mean streamlines is unchanging. Deep understanding of such effects is of critical importance to understanding practical flows, specifically, flow around marine or aerial vehicles. This gap limits predictive understanding of how curvature modifies transition length scales, mean-flow development and turbulence dynamics.

$8^\circ $

turn from the original flow direction and noted that the coherent flow structures turned to align with the local mean-flow direction, giving rise to secondary and tertiary turbulent stress components. Both Moin et al. (Reference Moin, Shih, Driver and Mansour1990) and Holstad et al. (Reference Holstad, Andersson and Pettersen2010) reported misalignment of the Reynolds shear stress and velocity gradient, and this phenomenon has also been documented by Bradshaw & Pontikos (Reference Bradshaw and Pontikos1985), Chesnakas & Simpson (Reference Chesnakas and Simpson1996) and Hu, Hayat & Park (Reference Hu, Hayat and Park2023). Apart from these observations, the effect of spanwise streamline curvature on transitioning and turbulent boundary layers has seldom been formally studied, especially in an idealised fashion where the curvature of the mean streamlines is unchanging. Deep understanding of such effects is of critical importance to understanding practical flows, specifically, flow around marine or aerial vehicles. This gap limits predictive understanding of how curvature modifies transition length scales, mean-flow development and turbulence dynamics.

To this end, an idealised DNS study is conducted with an array of resolved trips to induce turbulent transition on a flat plate. A novel method is introduced to impose flow turning about the wall-normal axis via body force at constant radius, resembling the conditions on a prolate spheroid. This approach enables, for the first time in DNS, an investigation of how transverse streamline curvature alters transition distance, bulk and secondary flows, turbulent stresses, and the alignment and orientation of turbulent structures. The numerical methodology is described in § 2 and followed by an outline of the problem set-up in § 3; the results are presented and analysed in § 4 and summarised in § 5.

2. Numerical approach

2.1. Direct numerical simulation

The incompressible Navier–Stokes equations in Cartesian coordinates are

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \partial _iu_i &= 0, \\ \frac {\partial {u_i}}{\partial {t}} + \partial _j(u_iu_j) &= -\partial _ip + \nu \partial _j\partial _ju_i + f_i, \end{aligned} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \partial _iu_i &= 0, \\ \frac {\partial {u_i}}{\partial {t}} + \partial _j(u_iu_j) &= -\partial _ip + \nu \partial _j\partial _ju_i + f_i, \end{aligned} \end{equation}

where

![]() $x_i$

,

$x_i$

,

![]() $u_i$

and

$u_i$

and

![]() $\partial _i$

represent the

$\partial _i$

represent the

![]() $i$

th components of the position, velocity and spatial-derivative (

$i$

th components of the position, velocity and spatial-derivative (

![]() $\partial /\partial x_i$

) vectors, respectively,

$\partial /\partial x_i$

) vectors, respectively,

![]() $p$

denotes the density-normalised pressure,

$p$

denotes the density-normalised pressure,

![]() $\nu$

represents the kinematic viscosity of the fluid and

$\nu$

represents the kinematic viscosity of the fluid and

![]() $f_i$

is an externally applied density-normalised pressure gradient. The equations are solved with a spatially second-order finite-volume algorithm (Mahesh, Constantinescu & Moin Reference Mahesh, Constantinescu and Moin2004) that was extended to allow for overlapping grid configurations and six-degree-of-freedom movement (Horne & Mahesh Reference Horne and Mahesh2019a

, Reference Horne and Mahesh2019b

). The velocity and pressure values are stored at the cell centroids and the face-normal velocities are estimated at the face centres. The velocity update is calculated using a predictor–corrector methodology by prediction through the momentum equation and correction via the pressure gradient obtained from the Poisson equation yielded by continuity. A second-order implicit Crank–Nicolson time-marching scheme is used. Discrete kinetic energy conservation is emphasised in the inviscid limit enabling the simulation of high-Reynolds-number flows while avoiding numerical dissipation. Moving forward, mean quantities will be denoted with an overbar

$f_i$

is an externally applied density-normalised pressure gradient. The equations are solved with a spatially second-order finite-volume algorithm (Mahesh, Constantinescu & Moin Reference Mahesh, Constantinescu and Moin2004) that was extended to allow for overlapping grid configurations and six-degree-of-freedom movement (Horne & Mahesh Reference Horne and Mahesh2019a

, Reference Horne and Mahesh2019b

). The velocity and pressure values are stored at the cell centroids and the face-normal velocities are estimated at the face centres. The velocity update is calculated using a predictor–corrector methodology by prediction through the momentum equation and correction via the pressure gradient obtained from the Poisson equation yielded by continuity. A second-order implicit Crank–Nicolson time-marching scheme is used. Discrete kinetic energy conservation is emphasised in the inviscid limit enabling the simulation of high-Reynolds-number flows while avoiding numerical dissipation. Moving forward, mean quantities will be denoted with an overbar

![]() $\overline {(\boldsymbol{\cdot })}$

, turbulent quantities will be denoted as prime

$\overline {(\boldsymbol{\cdot })}$

, turbulent quantities will be denoted as prime

![]() $(\boldsymbol{\cdot })'$

and quantities scaled with local wall units will be denoted with a plus

$(\boldsymbol{\cdot })'$

and quantities scaled with local wall units will be denoted with a plus

![]() $(\boldsymbol{\cdot })^+$

. All represented quantities are time and span averaged unless otherwise specified.

$(\boldsymbol{\cdot })^+$

. All represented quantities are time and span averaged unless otherwise specified.

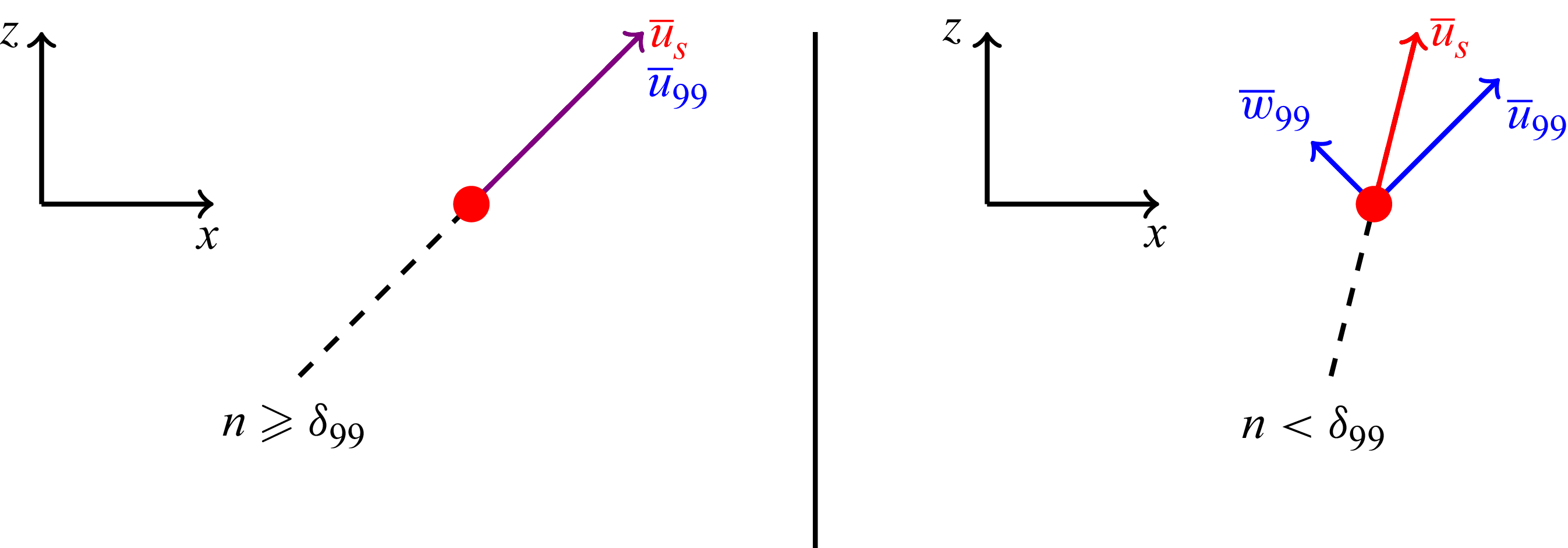

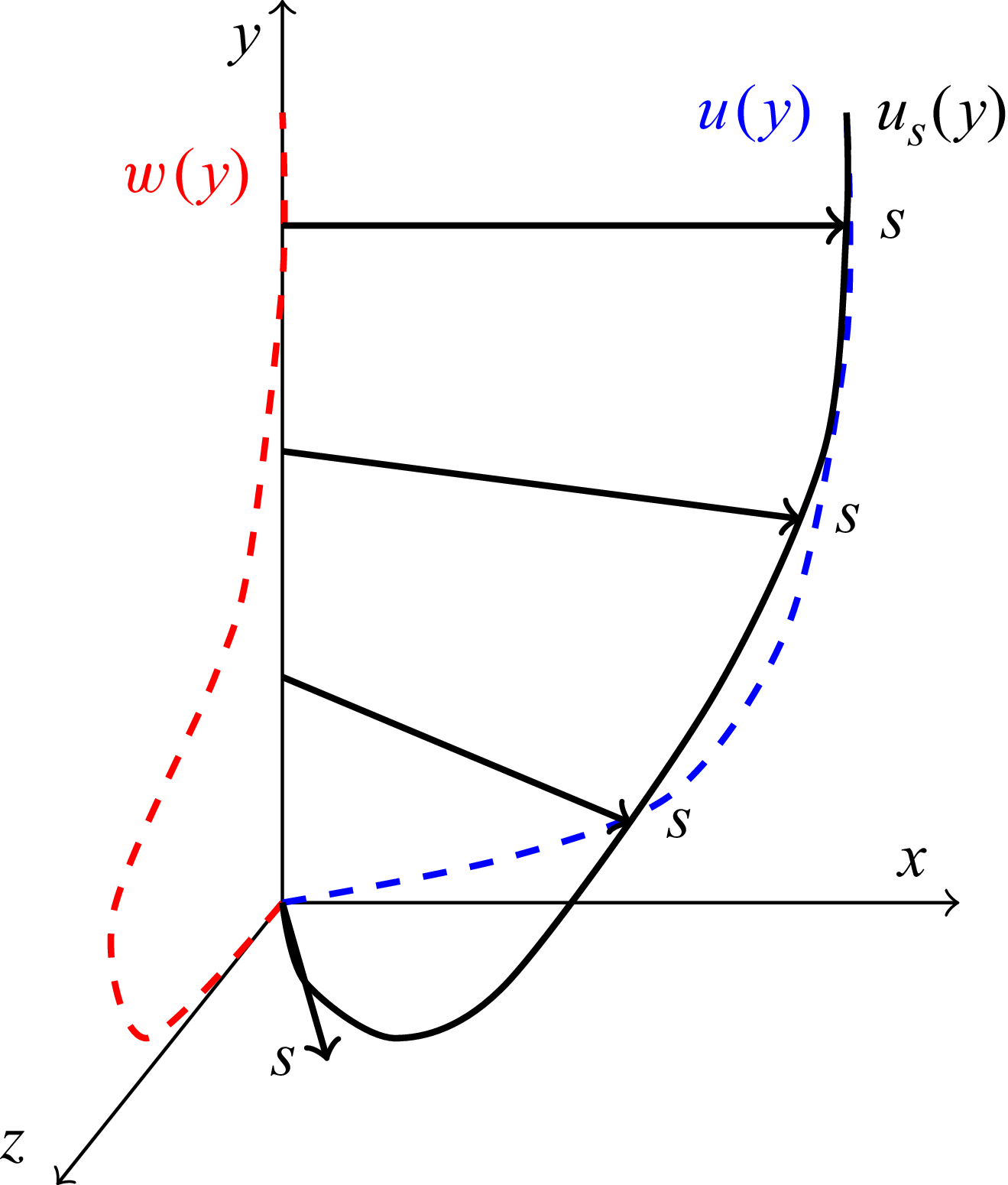

2.2. Coordinate systems

The study of curved geometries requires that the coordinate system be chosen carefully. Standard Cartesian or polar reference frames are ineffective when analysing boundary layer development as the coordinate direction does not necessarily align with the no-penetration boundary condition, invalidating canonical boundary layer assumptions. A cylindrical coordinate system is not viable unless the radius of curvature is constant, which is untrue for most practical flows. Selecting a coordinate frame that is everywhere normal and tangential to the surface offers an appropriate solution if the mean streamlines closely follow the geometry; however, this generalisation does not always hold. The ideal coordinate system coincides with the flow direction and provides a reference frame normal to the geometry. This simplifies the analysis of quantities between two points that would otherwise involve integration along a curve. Previous works by Cooke (Reference Cooke1958), Finnigan (Reference Finnigan1983), Morse & Mahesh (Reference Morse and Mahesh2021), Plasseraud et al. (Reference Plasseraud, Kumar and Mahesh2023), Prakash et al. (Reference Prakash, Balin, Evans and Jansen2024) and Finnigan (Reference Finnigan2024) have reported streamline-oriented reference frames, and this current work will adopt a coordinate system where

![]() $\langle s, n, {\zeta } \rangle$

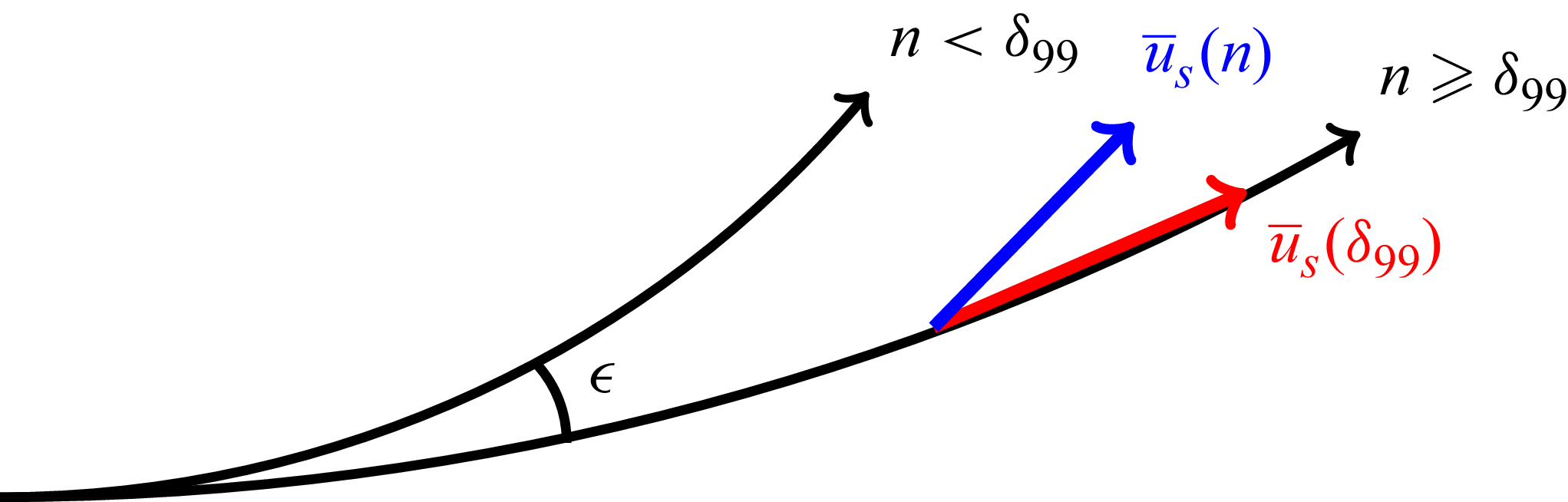

are the coordinate axes aligned with the mean streamline, the local wall-normal vector and the cross-product of the two. Two coordinate systems are considered. The first system uses the streamline defined by the mean velocity vector at the

$\langle s, n, {\zeta } \rangle$

are the coordinate axes aligned with the mean streamline, the local wall-normal vector and the cross-product of the two. Two coordinate systems are considered. The first system uses the streamline defined by the mean velocity vector at the

![]() $\delta _{99}$

location of the mean boundary layer as its first axis, the wall-normal direction as the second axis and the cross-product of the two as the third axis. The wall-normal axis is then recomputed with the cross-product of the mean velocity at the boundary layer edge and the newly computed streamline-tangential axis to ensure an orthogonal coordinate frame. The mean velocity vector in this coordinate system will be written as

$\delta _{99}$

location of the mean boundary layer as its first axis, the wall-normal direction as the second axis and the cross-product of the two as the third axis. The wall-normal axis is then recomputed with the cross-product of the mean velocity at the boundary layer edge and the newly computed streamline-tangential axis to ensure an orthogonal coordinate frame. The mean velocity vector in this coordinate system will be written as

![]() $\langle \overline {u}_{99}, \overline {v}_{99}, \overline {w}_{99} \rangle$

. The second system is defined by the orientation of the local velocity vector for the first axis, the wall-normal direction for the second axis, and the cross-product of the first two axes for the third axis. The wall-normal axis is similarly recomputed with another cross-product. The mean velocity vector in this coordinate system will be written as

$\langle \overline {u}_{99}, \overline {v}_{99}, \overline {w}_{99} \rangle$

. The second system is defined by the orientation of the local velocity vector for the first axis, the wall-normal direction for the second axis, and the cross-product of the first two axes for the third axis. The wall-normal axis is similarly recomputed with another cross-product. The mean velocity vector in this coordinate system will be written as

![]() $\langle \overline {u}_s, \overline {u}_n, \overline {u}_{{\zeta }}\rangle$

. This is shown graphically for two arbitrary streamlines in figure 1. Note that in the local streamline coordinate system, the bulk flow is aligned everywhere with the

$\langle \overline {u}_s, \overline {u}_n, \overline {u}_{{\zeta }}\rangle$

. This is shown graphically for two arbitrary streamlines in figure 1. Note that in the local streamline coordinate system, the bulk flow is aligned everywhere with the

![]() $s$

coordinate leaving mean quantities in

$s$

coordinate leaving mean quantities in

![]() $n$

and

$n$

and

![]() $t$

zero by construction. The

$t$

zero by construction. The

![]() $\delta _{99}$

-coordinate system collapses to the local streamline coordinate system at the boundary layer edge and is useful for showing secondary flow within the boundary layer.

$\delta _{99}$

-coordinate system collapses to the local streamline coordinate system at the boundary layer edge and is useful for showing secondary flow within the boundary layer.

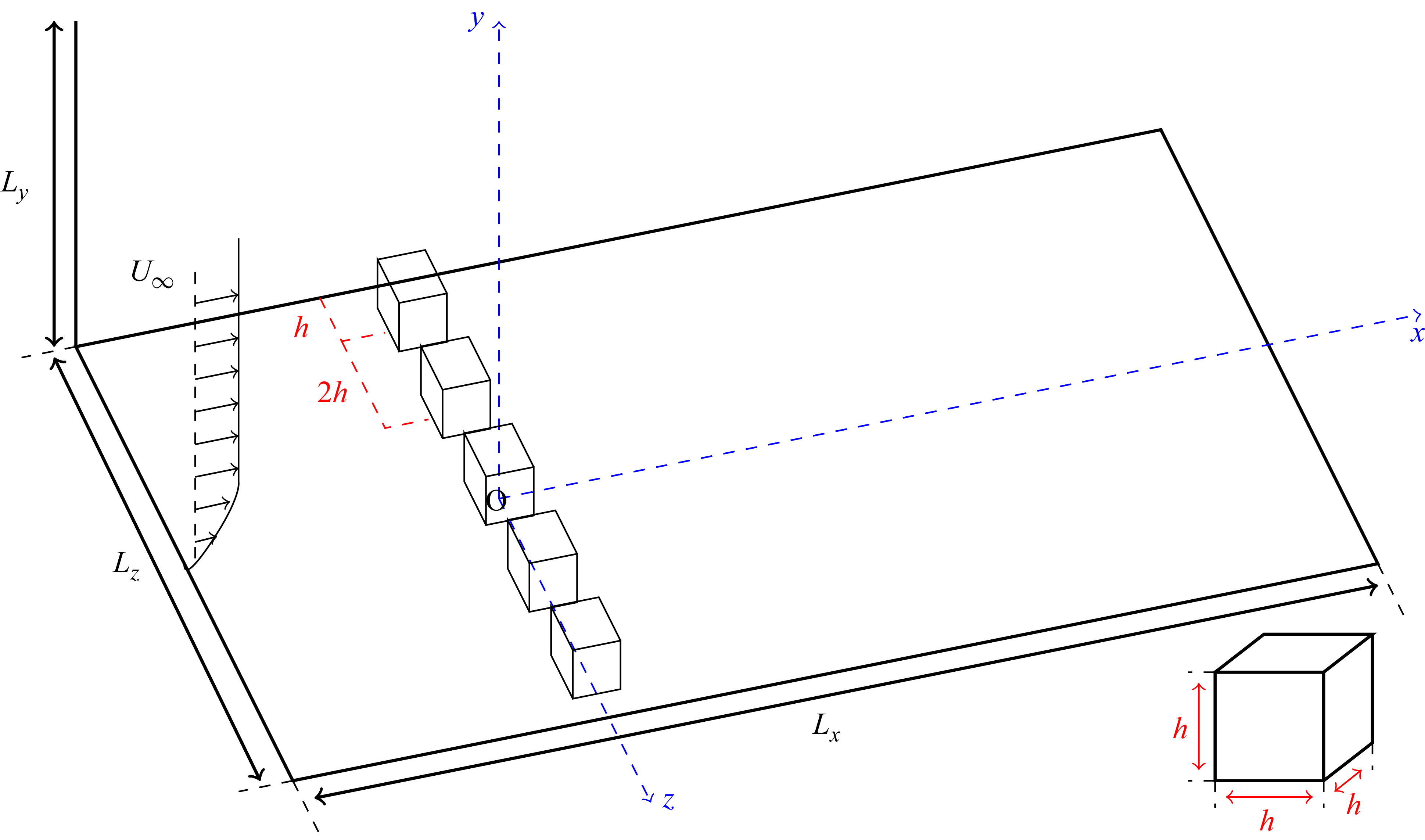

3. Problem description

3.1. Numerical apparatus

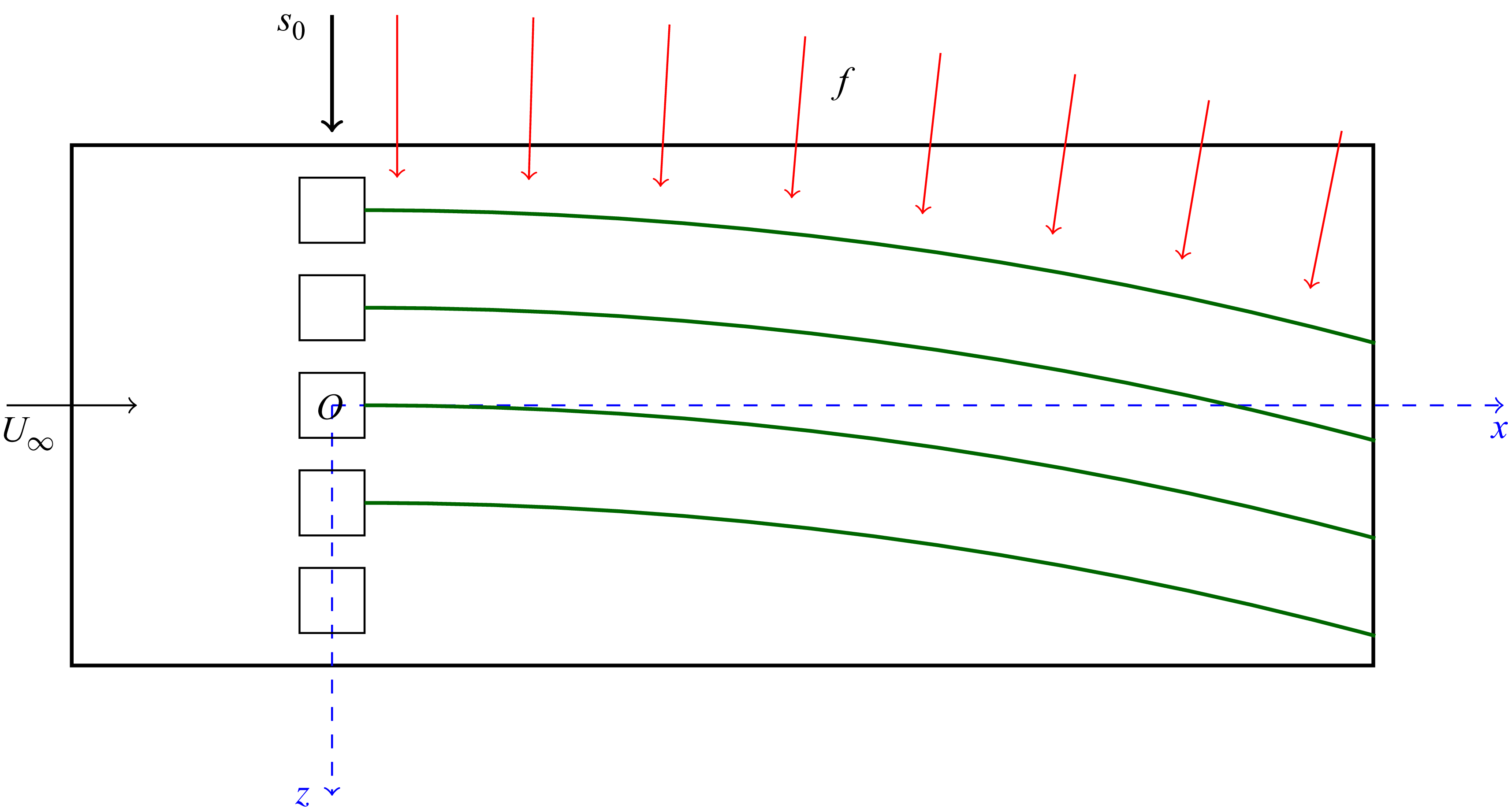

A visual representation of the general computational domain is shown in figure 2. A laminar Blasius profile is prescribed at the inflow at

![]() $x = -10h$

such that the displacement thickness of the boundary layer at the trip location is

$x = -10h$

such that the displacement thickness of the boundary layer at the trip location is

![]() $\delta ^{*} = h/2.86$

, specified using the methodology detailed in Savaş (Reference Savaş2012). Convective boundary conditions are prescribed at the outflow at

$\delta ^{*} = h/2.86$

, specified using the methodology detailed in Savaş (Reference Savaş2012). Convective boundary conditions are prescribed at the outflow at

![]() $x = 150h$

; periodic boundary conditions are prescribed in the spanwise direction at

$x = 150h$

; periodic boundary conditions are prescribed in the spanwise direction at

![]() $z = -5h$

and

$z = -5h$

and

![]() $z = 5h$

; and no-slip boundary conditions are prescribed on the roughness elements and the bottom wall at

$z = 5h$

; and no-slip boundary conditions are prescribed on the roughness elements and the bottom wall at

![]() $y = 0$

. Full-slip, no-penetration boundary conditions are prescribed at the upper boundary at

$y = 0$

. Full-slip, no-penetration boundary conditions are prescribed at the upper boundary at

![]() $y=15h$

by projecting the wall velocity onto the plane parallel to the top boundary:

$y=15h$

by projecting the wall velocity onto the plane parallel to the top boundary:

![]() $u_{\textit{top}} = u-(u \boldsymbol{\cdot }\hat {\boldsymbol {n}})\hat {\boldsymbol {n}}$

, where

$u_{\textit{top}} = u-(u \boldsymbol{\cdot }\hat {\boldsymbol {n}})\hat {\boldsymbol {n}}$

, where

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol {n}}$

is the unit vector normal to the upper boundary. The boundary layer is tripped using a set of cuboids of side length

$\hat {\boldsymbol {n}}$

is the unit vector normal to the upper boundary. The boundary layer is tripped using a set of cuboids of side length

![]() $h$

. The entire array occupies the span centred at

$h$

. The entire array occupies the span centred at

![]() $(x, z) = (0, 0)$

, evenly spaced every

$(x, z) = (0, 0)$

, evenly spaced every

![]() $2h$

; the roughness elements are resolved by 120 elements in the wall-normal direction. The Reynolds number,

$2h$

; the roughness elements are resolved by 120 elements in the wall-normal direction. The Reynolds number,

![]() $\textit{Re}_h$

, is based on the trip height, the kinematic viscosity and

$\textit{Re}_h$

, is based on the trip height, the kinematic viscosity and

![]() $U_\infty$

, the inflow velocity for

$U_\infty$

, the inflow velocity for

![]() $y \gg \delta _{99}$

. The grid spacing is uniform in both streamwise and spanwise directions; a wall-normal clustering is applied on the no-slip wall using the Rakich stretching function as detailed in MacCormack (Reference MacCormack2014). The streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise extents of the domain are denoted by

$y \gg \delta _{99}$

. The grid spacing is uniform in both streamwise and spanwise directions; a wall-normal clustering is applied on the no-slip wall using the Rakich stretching function as detailed in MacCormack (Reference MacCormack2014). The streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise extents of the domain are denoted by

![]() $L_x, L_y$

and

$L_x, L_y$

and

![]() $L_z$

, and the number of grid points are denoted by

$L_z$

, and the number of grid points are denoted by

![]() $N_x, N_y \,{\rm and }\,N_z$

. The spanwise and wall-normal extents are the same as the grid of Ma & Mahesh (Reference Ma and Mahesh2022). The solver is advanced with a time step of

$N_x, N_y \,{\rm and }\,N_z$

. The spanwise and wall-normal extents are the same as the grid of Ma & Mahesh (Reference Ma and Mahesh2022). The solver is advanced with a time step of

![]() $5\times 10^{-4}\,h{U_\infty }^{-1}$

, and statistics are collected for

$5\times 10^{-4}\,h{U_\infty }^{-1}$

, and statistics are collected for

![]() $6\times 10^{3}\,h{U_\infty }^{-1}$

at a frequency of

$6\times 10^{3}\,h{U_\infty }^{-1}$

at a frequency of

![]() $5\times 10^{-2}\,h{U_\infty }^{-1}$

. More details on the computational domain can be found in table 1.

$5\times 10^{-2}\,h{U_\infty }^{-1}$

. More details on the computational domain can be found in table 1.

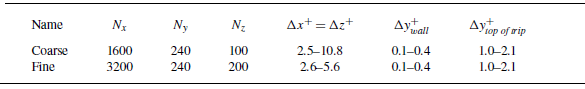

Table 1. Domain resolutions for the grid convergence study are listed in wall units based on the range of friction velocity

![]() $u_\tau$

present in the domain at

$u_\tau$

present in the domain at

![]() $\textit{Re}_h=2000$

. The boundary conditions; streamwise, spanwise and wall-normal extents; and distance between the inflow and cuboid array remain constant for all cases.

$\textit{Re}_h=2000$

. The boundary conditions; streamwise, spanwise and wall-normal extents; and distance between the inflow and cuboid array remain constant for all cases.

Figure 1. Comparison between local streamline coordinate system (red) and

![]() $\delta _{99}$

-aligned coordinate system (blue) considering two points at the same

$\delta _{99}$

-aligned coordinate system (blue) considering two points at the same

![]() $(s, {\zeta })$

locations at varying

$(s, {\zeta })$

locations at varying

![]() $n$

.

$n$

.

Figure 2. Sketch of domain and roughness geometries.

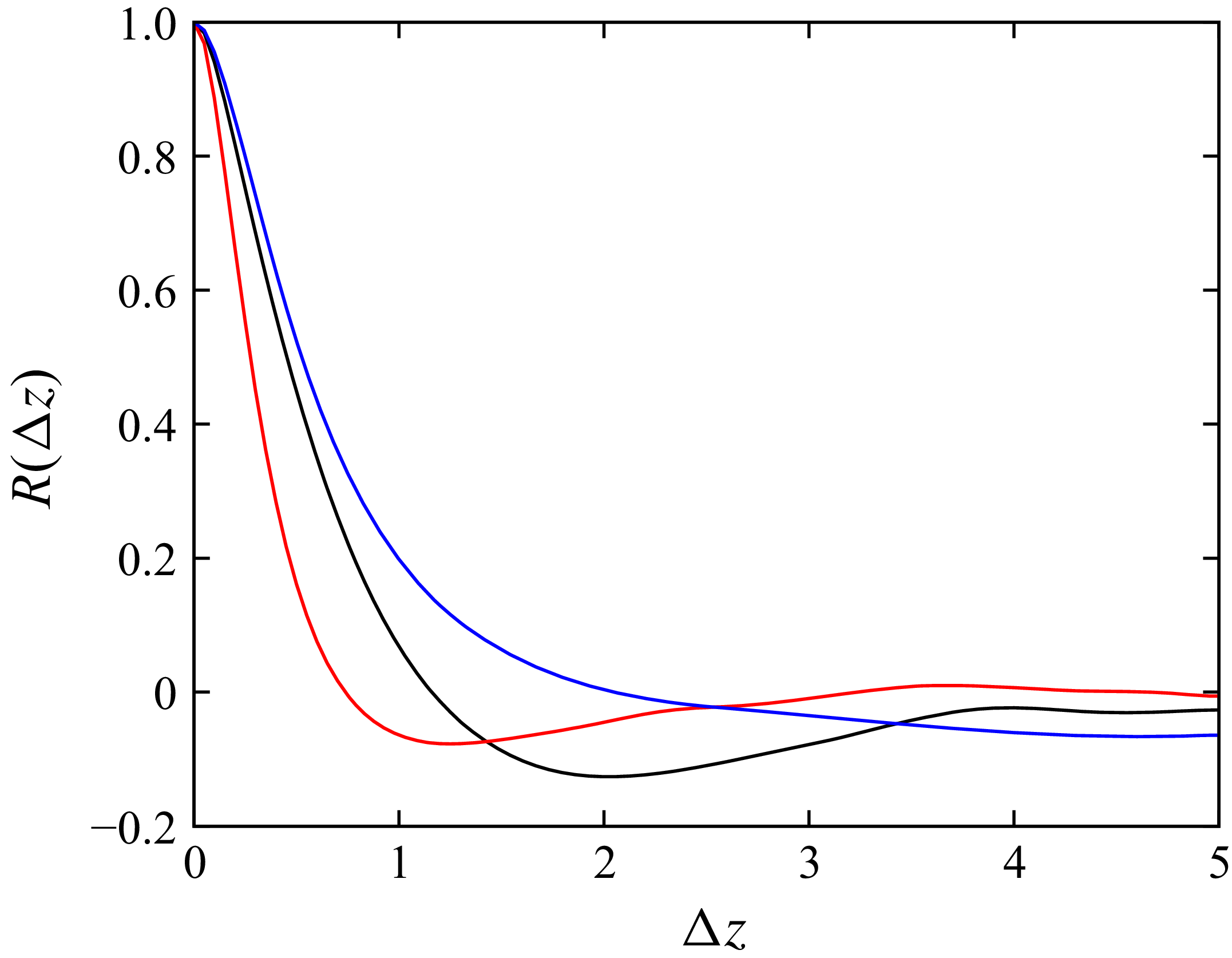

3.2. Grid validation

To assess whether the computational domain is sufficiently wide to not be influenced by spanwise periodicity, the two-point autocorrelation of the velocity fluctuations is considered in the spanwise direction with

![]() $N_z$

uniformly spaced spanwise points ranging

$N_z$

uniformly spaced spanwise points ranging

![]() $L_z$

, defined in (3.1) as the inverse discrete Fourier transform of the power spectrum, which is then normalised by the autocorrelation at

$L_z$

, defined in (3.1) as the inverse discrete Fourier transform of the power spectrum, which is then normalised by the autocorrelation at

![]() $\Delta z = 0$

.

$\Delta z = 0$

.

\begin{equation} R_{\textit{ii}}(n) = \frac {\sum _{j=0}^{N_z-1}|\hat {f_j}|^2{\rm e}^{ik_jn\Delta z}}{\sum _{j=0}^{N_z-1}|\hat {f_j}|^2}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} R_{\textit{ii}}(n) = \frac {\sum _{j=0}^{N_z-1}|\hat {f_j}|^2{\rm e}^{ik_jn\Delta z}}{\sum _{j=0}^{N_z-1}|\hat {f_j}|^2}. \end{equation}

Here

![]() $|\hat {f}(k_j, t)|^2$

is the discrete energy spectrum at spanwise wavenumber

$|\hat {f}(k_j, t)|^2$

is the discrete energy spectrum at spanwise wavenumber

![]() $k_j$

. This signal was sampled every

$k_j$

. This signal was sampled every

![]() $0.01h{U_\infty }^{-1}$

over a duration of

$0.01h{U_\infty }^{-1}$

over a duration of

![]() $1000h{U_\infty }^{-1}$

. Figure 3 shows the spanwise autocorrelation of streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise velocity fluctuations near the outflow at

$1000h{U_\infty }^{-1}$

. Figure 3 shows the spanwise autocorrelation of streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise velocity fluctuations near the outflow at

![]() $s=145h{, }n=h$

from the fine grid for a zero-pressure-gradient turbulent boundary layer (ZPG TBL) at

$s=145h{, }n=h$

from the fine grid for a zero-pressure-gradient turbulent boundary layer (ZPG TBL) at

![]() $\textit{Re}_h = 2000$

. Here

$\textit{Re}_h = 2000$

. Here

![]() $R_{\textit{uu}}$

,

$R_{\textit{uu}}$

,

![]() $R_{vv}$

and

$R_{vv}$

and

![]() $R_{ww}$

all decay rapidly and approach zero well before

$R_{ww}$

all decay rapidly and approach zero well before

![]() $L_z/2$

. The autocorrelation at

$L_z/2$

. The autocorrelation at

![]() $\Delta z = L_z/2$

is small (

$\Delta z = L_z/2$

is small (

![]() $|R_{ww}|(\Delta z = L_z/2) \approx 0.06$

and there are no secondary peaks where the periodic boundary conditions are enforced, suggesting that the small residual is physical rather than an artefact of periodicity. This diagnostic indicates that the domain width is sufficient and that the turbulent statistics are not contaminated by spanwise periodicity.

$|R_{ww}|(\Delta z = L_z/2) \approx 0.06$

and there are no secondary peaks where the periodic boundary conditions are enforced, suggesting that the small residual is physical rather than an artefact of periodicity. This diagnostic indicates that the domain width is sufficient and that the turbulent statistics are not contaminated by spanwise periodicity.

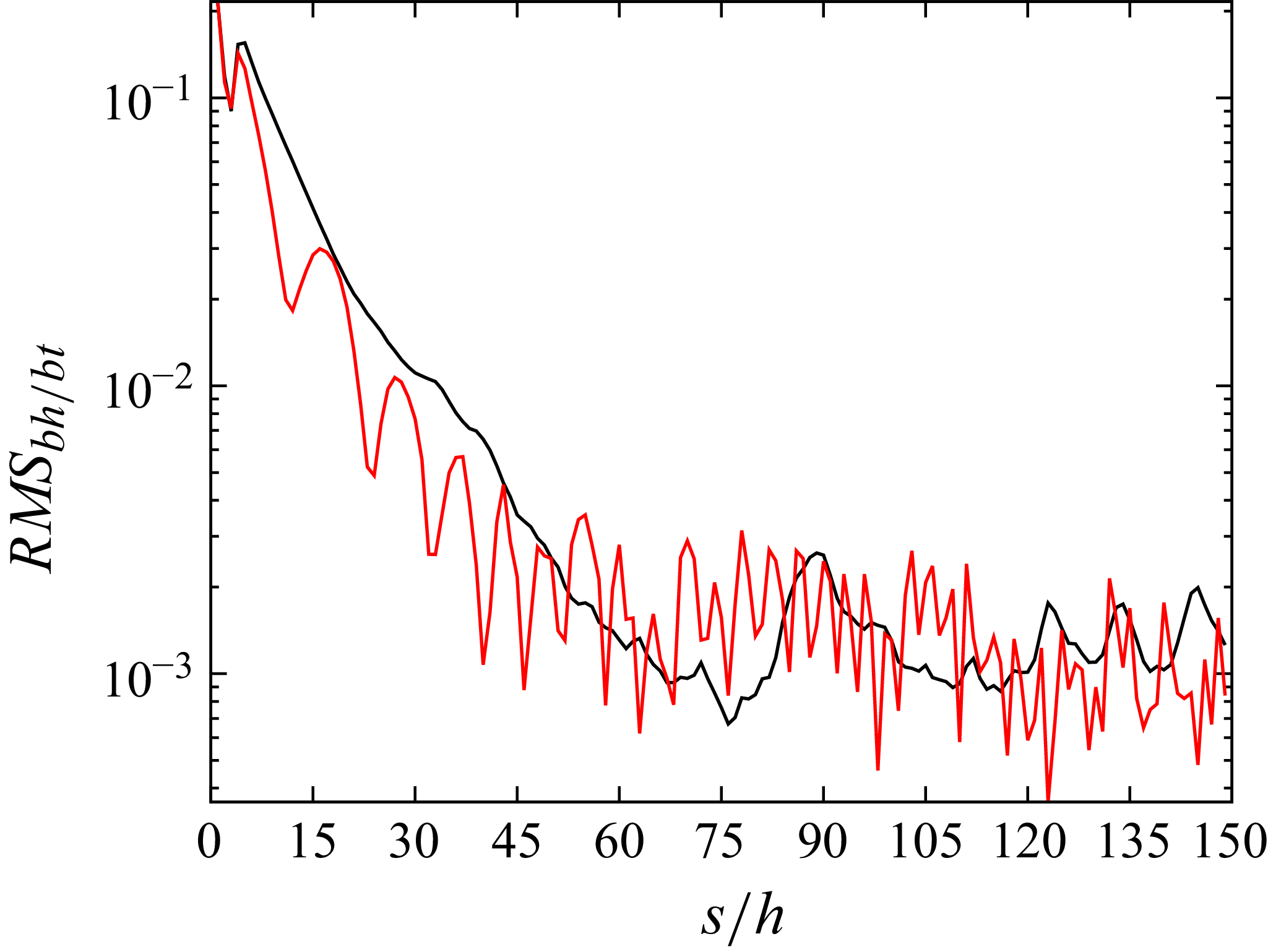

Figure 3. Domain sensitivity analysis for ZPG TBL on a fine grid at

![]() $\textit{Re}_h=2000$

showing spanwise autocorrelation of streamline fluctuations

$\textit{Re}_h=2000$

showing spanwise autocorrelation of streamline fluctuations

![]() $R_{\textit{uu}}$

, wall-normal fluctuations

$R_{\textit{uu}}$

, wall-normal fluctuations

![]() $R_{vv}$

(red) and spanwise fluctuations

$R_{vv}$

(red) and spanwise fluctuations

![]() $R_{ww}$

(black) at

$R_{ww}$

(black) at

![]() $s=145h$

.

$s=145h$

.

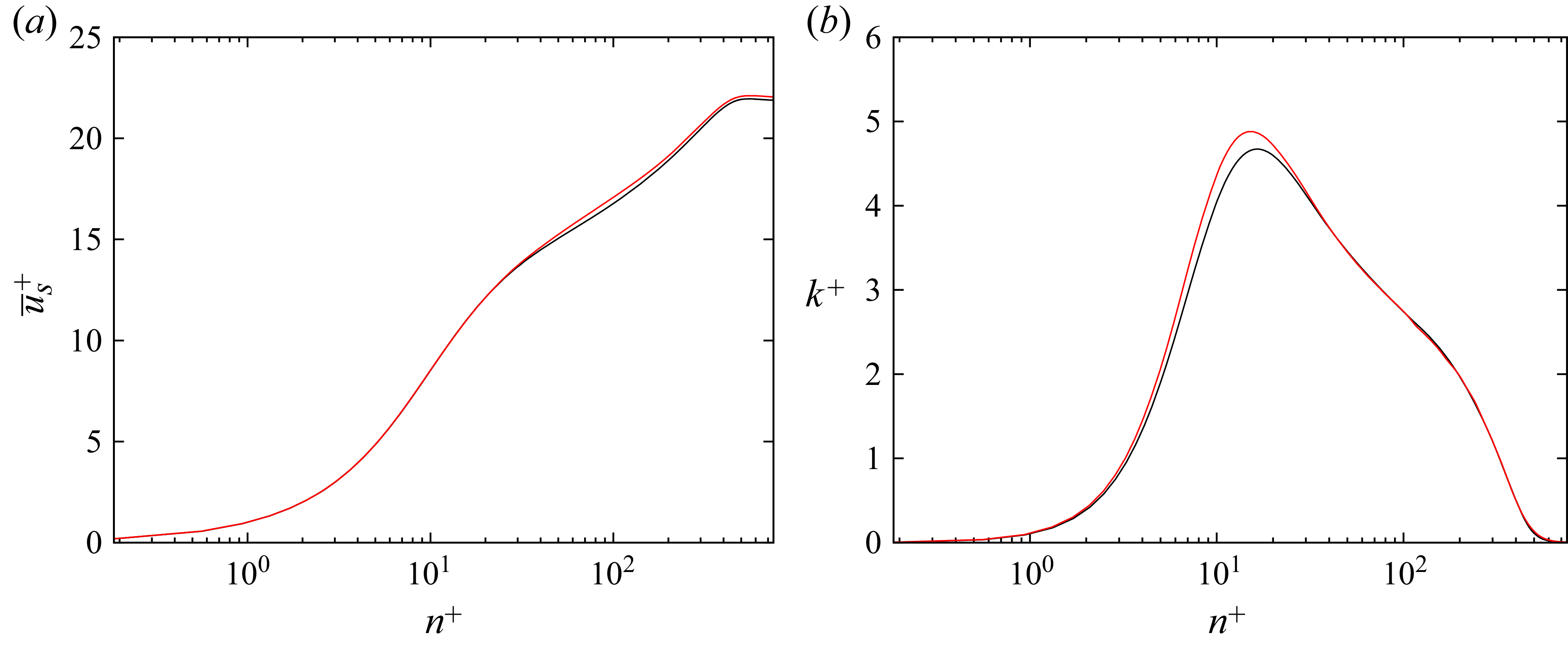

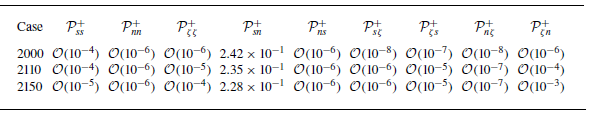

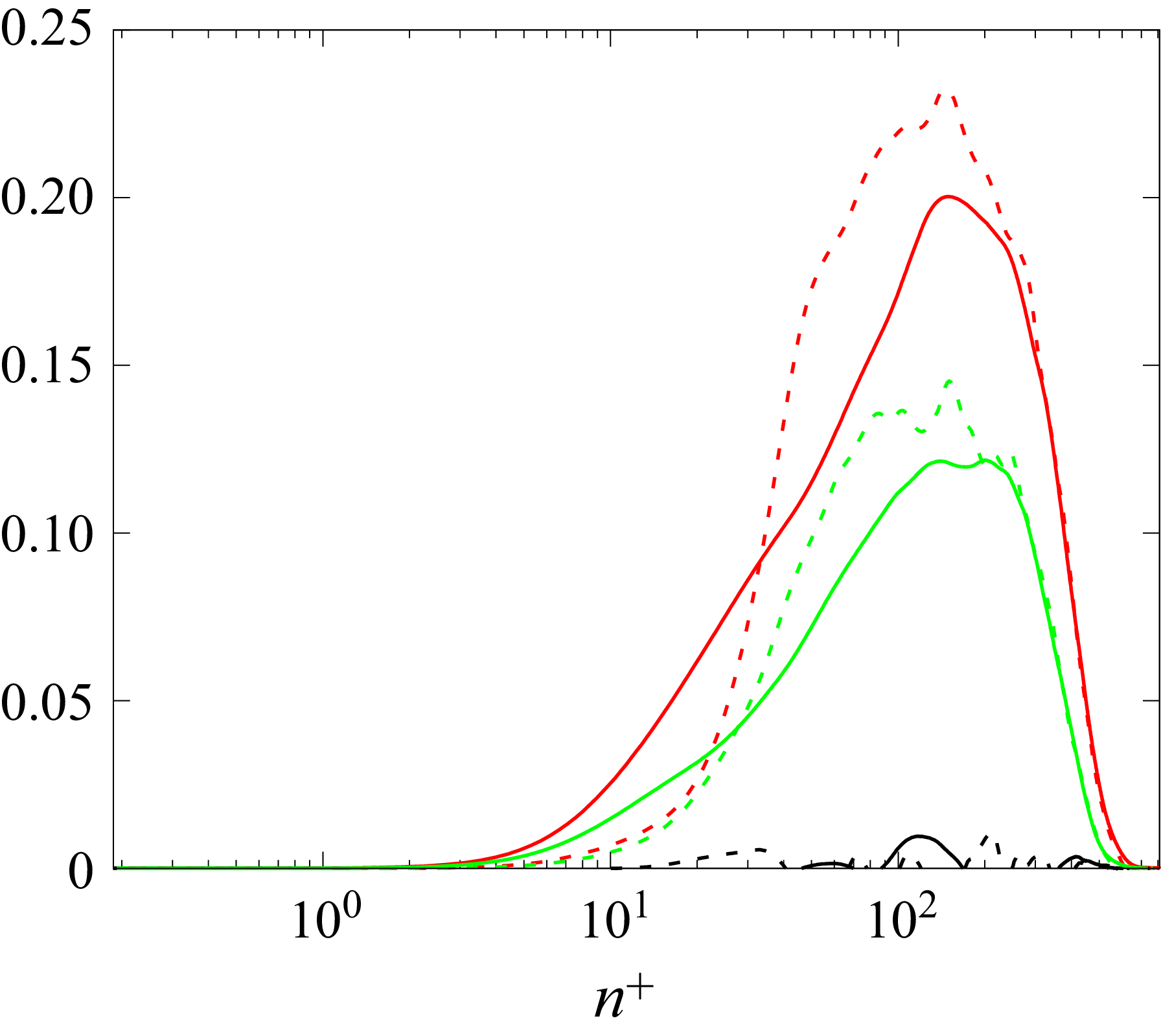

Figure 4. Results from the grid convergence study for ZPG TBL at

![]() $\textit{Re}_h=2000$

on both coarse (red) and fine (black) grids from table 1 showing (a) mean velocity profile and (b) turbulent kinetic energy at

$\textit{Re}_h=2000$

on both coarse (red) and fine (black) grids from table 1 showing (a) mean velocity profile and (b) turbulent kinetic energy at

![]() $s = 135h$

.

$s = 135h$

.

Figure 4 shows a comparison between the results from the coarse and fine domains (outlined in table 1) showing the mean velocity profile (panel a) and the mean kinetic energy profile (panel b) in wall units at

![]() $s = 135h$

for ZPG TBLs at

$s = 135h$

for ZPG TBLs at

![]() $\textit{Re}_h=2000$

. Both grids give similar results, with the coarse grid slightly overpredicting the velocity and the TKE at the bottom of the log layer for

$\textit{Re}_h=2000$

. Both grids give similar results, with the coarse grid slightly overpredicting the velocity and the TKE at the bottom of the log layer for

![]() $n^+ \in [40, 200]$

.

$n^+ \in [40, 200]$

.

The following results are based on the fine grid as detailed in table 1.

3.3. Summary of the cases

A zero curvature and a right-turning spanwise curvature about the wall-normal axis are being investigated at Reynolds numbers of

![]() $\textit{Re}_h = 1000$

and

$\textit{Re}_h = 1000$

and

![]() $2000$

. The zero curvature case follows the flow configuration outlined in figure 2 and is used as a baseline. Spanwise curvature is prescribed via a pressure gradient that is kept orthogonal to the mean free-stream velocity vector as shown in figure 5. The application of this body force can be understood by considering the steady, incompressible

$2000$

. The zero curvature case follows the flow configuration outlined in figure 2 and is used as a baseline. Spanwise curvature is prescribed via a pressure gradient that is kept orthogonal to the mean free-stream velocity vector as shown in figure 5. The application of this body force can be understood by considering the steady, incompressible

![]() $r$

-momentum equation in cylindrical coordinates

$r$

-momentum equation in cylindrical coordinates

![]() $\langle r, \phi , z \rangle$

with external body force

$\langle r, \phi , z \rangle$

with external body force

![]() $f$

:

$f$

:

As the radius of curvature

![]() $R$

is constant, the cylindrical coordinates can be likened to streamline-aligned coordinates

$R$

is constant, the cylindrical coordinates can be likened to streamline-aligned coordinates

![]() $\langle {\zeta }, s, n \rangle$

:

$\langle {\zeta }, s, n \rangle$

:

In the free stream, viscous effects are negligible, and with assumptions of spanwise homogeneity, a slow change in streamwise velocity and negligible wall-normal velocity, a balance is obtained between the centrifugal acceleration

![]() ${U_\infty }^2/R$

and the prescribed body force

${U_\infty }^2/R$

and the prescribed body force

![]() $f$

. Thus, the applied body forces in

$f$

. Thus, the applied body forces in

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $z$

along the domain are

$z$

along the domain are

![]() ${f_x =} -{U_\infty }^2\sin (\theta )/R$

and

${f_x =} -{U_\infty }^2\sin (\theta )/R$

and

![]() ${f_z =} {U_\infty }^2\cos (\theta )/R$

, where

${f_z =} {U_\infty }^2\cos (\theta )/R$

, where

![]() $\theta =x/R$

is the distance travelled along the circumference of the circle. The curvature of the inviscid streamlines is investigated for curvatures

$\theta =x/R$

is the distance travelled along the circumference of the circle. The curvature of the inviscid streamlines is investigated for curvatures

![]() $R = 500h$

and

$R = 500h$

and

![]() $1000h$

with curvature effects beginning at

$1000h$

with curvature effects beginning at

![]() $s_0 = 0$

. These are similar values to those observed by Plasseraud et al. (Reference Plasseraud, Kumar and Mahesh2023) in their study on the 6 : 1 prolate spheroid. This information is organised in table 2.

$s_0 = 0$

. These are similar values to those observed by Plasseraud et al. (Reference Plasseraud, Kumar and Mahesh2023) in their study on the 6 : 1 prolate spheroid. This information is organised in table 2.

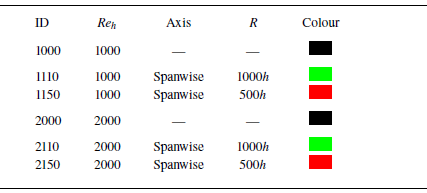

Table 2. Summary of the cases. The first digit of the case ID encodes the Reynolds number; the second digit, the type of curvature (0 for none, 1 for spanwise); the third, the radius of curvature. The last column shows the colour that each case will be represented by in figures.

Figure 5. Sketch of the applied spanwise pressure gradient.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Tripping effects

In the current section, an investigation is performed on whether the presence of a small spanwise curvature influences the downstream distance taken for the boundary layer to become a fully developed turbulent boundary layer. With that goal, the following criteria are considered.

-

(i) Statistical homogeneity of the velocity profiles in the span.

-

(ii) Presence of a logarithmic layer in the velocity profile.

-

(iii) Vanishing of residual harmonics of the trip in the spanwise spectra.

The first two conditions were previously developed by Plasseraud et al. (Reference Plasseraud, Kumar, Ma and Mahesh2022) to assess the effectiveness of a trip on the windward side of a prolate spheroid. These criteria verify that the resulting boundary layer is turbulent and that no signature of the trip is visible, ensuring that the state of the flow is not a function of the specific geometric characteristics of the trip. Figure 6 shows the instantaneous velocity field in the wake of the trips for case 2000 and illustrates how homogeneity is evaluated. The immediate vicinity of the trips is heterogeneous in the span, with low-speed streaks behind each trip and pockets of higher velocity between the trips. The mean velocity field then homogenises as the wakes of the trips diffuse. The homogeneity criterion is evaluated by taking velocity profiles along

![]() $z$

-planar slices behind and between each trip, shown in figure 6 with solid and dashed lines, respectively, for one trip. Profiles at the same streamwise stations along slices behind the trip are averaged together, and profiles at the same streamwise station along slices between the trip are averaged together. Once homogeneity is achieved, spanwise averaging is performed by considering data from every grid element in the span.

$z$

-planar slices behind and between each trip, shown in figure 6 with solid and dashed lines, respectively, for one trip. Profiles at the same streamwise stations along slices behind the trip are averaged together, and profiles at the same streamwise station along slices between the trip are averaged together. Once homogeneity is achieved, spanwise averaging is performed by considering data from every grid element in the span.

Figure 6. Contour plot of instantaneous transitionary streamwise velocity field for case 2000 at

![]() $n = 0.5h$

highlighting profile extraction locations.

$n = 0.5h$

highlighting profile extraction locations.

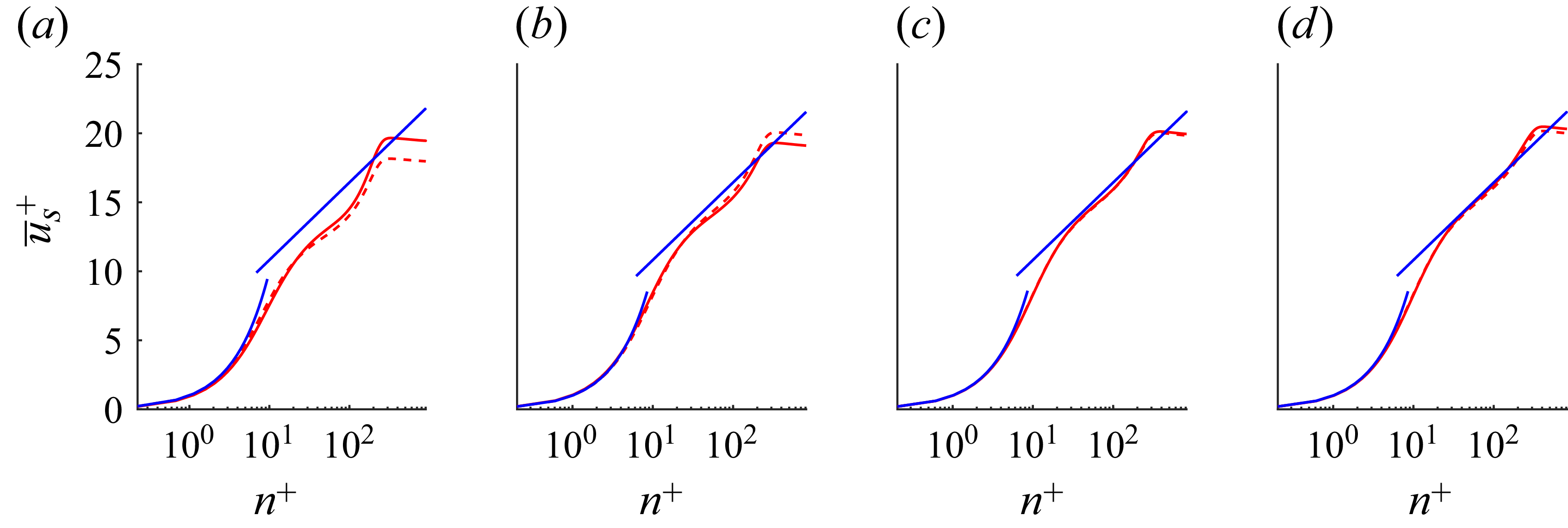

Figure 7 shows the velocity profiles between (

![]() $u_{bt}$

) and behind the trip (

$u_{bt}$

) and behind the trip (

![]() $u_{bh}$

) for case 2000 at

$u_{bh}$

) for case 2000 at

![]() $s = 20h, 30h, 40h, 50h$

. The profiles behind the trips initially have a 15 % momentum deficit with respect to the profiles between the trips, which have a momentum surplus as the former are in the recirculation zones of the obstacles while the latter are in the accelerated region. The two profiles converge with increasing distance from the trip as diffusion homogenises the flow. Figure 7 also shows where a logarithmic layer develops in the profile, indicating that a canonical turbulent boundary layer is found between

$s = 20h, 30h, 40h, 50h$

. The profiles behind the trips initially have a 15 % momentum deficit with respect to the profiles between the trips, which have a momentum surplus as the former are in the recirculation zones of the obstacles while the latter are in the accelerated region. The two profiles converge with increasing distance from the trip as diffusion homogenises the flow. Figure 7 also shows where a logarithmic layer develops in the profile, indicating that a canonical turbulent boundary layer is found between

![]() $s = 40h$

and

$s = 40h$

and

![]() $50h$

with ZPG. The same analysis is conducted for the case with spanwise curvature of radius

$50h$

with ZPG. The same analysis is conducted for the case with spanwise curvature of radius

![]() $500h$

. A similar momentum deficit is visible in figure 8, and profiles behind and between the trips converge with increasing streamwise distance. However, the pressure gradient transports fluid elements in recirculation regions behind the trip into high-speed streaks between the trips, promoting mixing. Figure 8 shows convergence of the profiles between and behind the trips at a more upstream location of

$500h$

. A similar momentum deficit is visible in figure 8, and profiles behind and between the trips converge with increasing streamwise distance. However, the pressure gradient transports fluid elements in recirculation regions behind the trip into high-speed streaks between the trips, promoting mixing. Figure 8 shows convergence of the profiles between and behind the trips at a more upstream location of

![]() $s \approx 40h$

; however, logarithmic layer development is not visible until

$s \approx 40h$

; however, logarithmic layer development is not visible until

![]() $s \approx 50h$

, indicating that the transition location is unchanged.

$s \approx 50h$

, indicating that the transition location is unchanged.

Figure 7. Mean velocity profiles behind the trip (solid) and between the trips (dashed) for case 2000 at (a)

![]() $s = 20h$

, (b)

$s = 20h$

, (b)

![]() $s = 30h$

, (c)

$s = 30h$

, (c)

![]() $s = 40h$

, (d)

$s = 40h$

, (d)

![]() $s = 50h$

with comparison to the law of the wall (blue).

$s = 50h$

with comparison to the law of the wall (blue).

Figure 8. Mean velocity profiles behind the trip (solid) and between the trips (dashed) for case 2150 at (a)

![]() $s = 20h$

, (b)

$s = 20h$

, (b)

![]() $s = 30h$

, (c)

$s = 30h$

, (c)

![]() $s = 40h$

, (d)

$s = 40h$

, (d)

![]() $s = 50h$

with comparison to the law of the wall (blue).

$s = 50h$

with comparison to the law of the wall (blue).

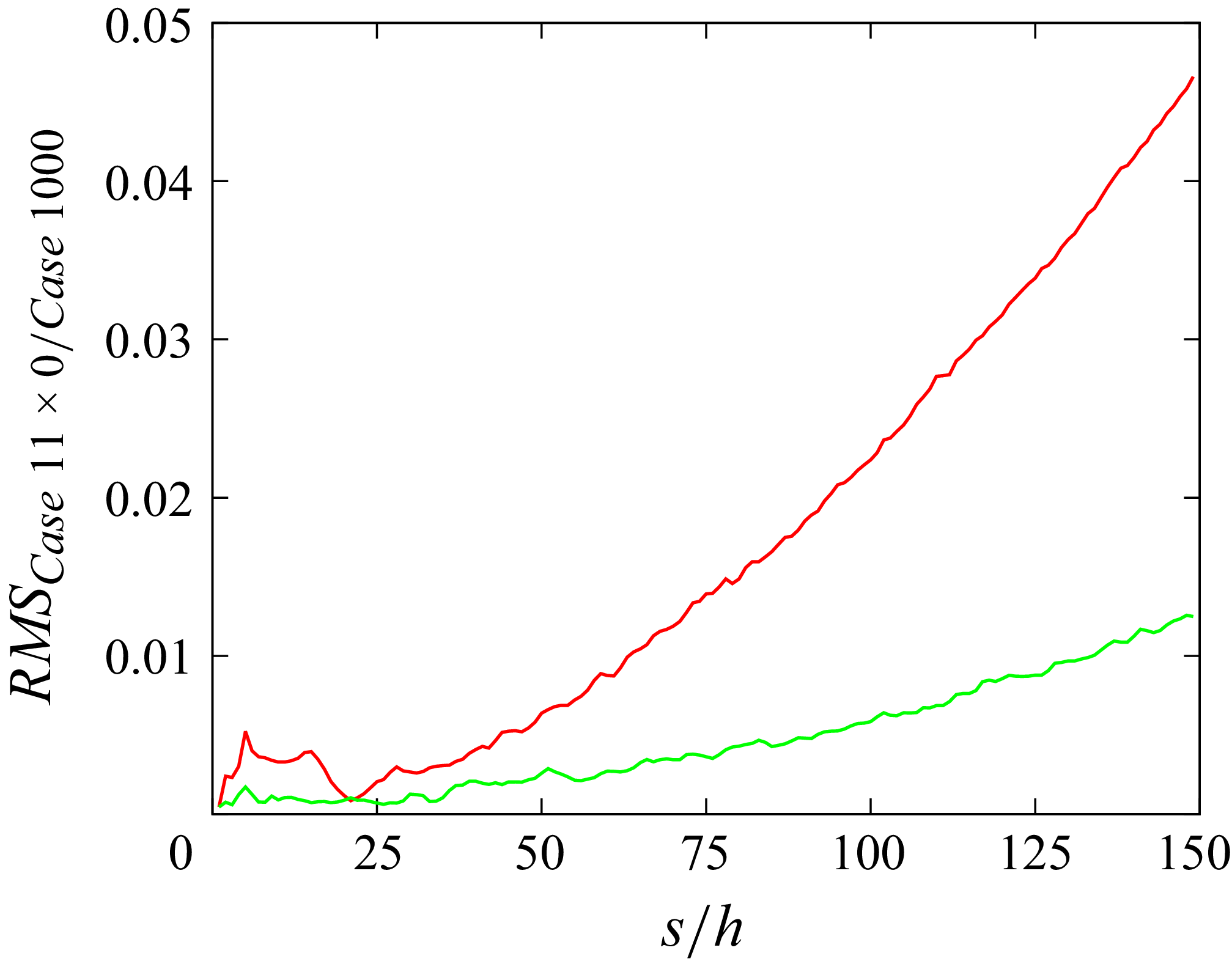

A quantitative metric of the homogeneity of the flow is calculated as the root mean square (RMS) of the difference between velocity profiles between and behind the trip, compared graphically between cases 2000 and 2150 in figure 9:

\begin{equation} \textit{RMS}_{bh/bt} = \sqrt {\frac {1}{N}\sum ^{N} \left(\int _0^{n_{\textit{max}}}(u_{bh}-u_{bt}) dn\right)^2}\!. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \textit{RMS}_{bh/bt} = \sqrt {\frac {1}{N}\sum ^{N} \left(\int _0^{n_{\textit{max}}}(u_{bh}-u_{bt}) dn\right)^2}\!. \end{equation}

Figure 9. Comparison of

![]() $\textit{RMS}_{bh/bt}$

for case 2000 (black) and case 2150 (red).

$\textit{RMS}_{bh/bt}$

for case 2000 (black) and case 2150 (red).

The deviation for both cases is at a maximum in the near-trip region and then decreases downstream. The streamwise distance at which

![]() $\textit{RMS}_{bh/bt}$

plateaus is taken as the transition distance,

$\textit{RMS}_{bh/bt}$

plateaus is taken as the transition distance,

![]() $s_t$

, which corresponds to the streamwise location where a logarithmic layer forms in figures 7 and 8. Here

$s_t$

, which corresponds to the streamwise location where a logarithmic layer forms in figures 7 and 8. Here

![]() $\textit{RMS}_{bh/bt}$

for case 2150 shows signs of faster convergence before tapering out, matching the prior observations. The noise in the RMS for case 2150 can be attributed to fluid elements travelling in the span. The smooth convergence of case 2000 exhibited in figure 9 is not present in the presence of curvature, as the higher velocity fluid elements between the trip and the slower velocity fluid elements behind the trip do not gradually diffuse.

$\textit{RMS}_{bh/bt}$

for case 2150 shows signs of faster convergence before tapering out, matching the prior observations. The noise in the RMS for case 2150 can be attributed to fluid elements travelling in the span. The smooth convergence of case 2000 exhibited in figure 9 is not present in the presence of curvature, as the higher velocity fluid elements between the trip and the slower velocity fluid elements behind the trip do not gradually diffuse.

Lastly, to further examine the effect of spanwise curvature on transition location, the spanwise spectra of velocity fluctuations is considered. A discrete Fourier transform is applied in the spanwise direction considering

![]() $N_z$

uniformly spaced points at

$N_z$

uniformly spaced points at

![]() $n=h$

using the same sampling frequency and period as in figure 3. The energy spectrum is defined as

$n=h$

using the same sampling frequency and period as in figure 3. The energy spectrum is defined as

where

![]() $\hat {u'}(k_z, t)$

is the Fourier transform of streamwise fluctuations. The energy spectrum for cases 2000 and 2150 at

$\hat {u'}(k_z, t)$

is the Fourier transform of streamwise fluctuations. The energy spectrum for cases 2000 and 2150 at

![]() $s = 5h, 25h, 45h, 65h, 85h$

is shown in figure 10. In the immediate wake of the trips (

$s = 5h, 25h, 45h, 65h, 85h$

is shown in figure 10. In the immediate wake of the trips (

![]() $s = 5h$

), the spectra show elevated energy levels at low wavenumbers (

$s = 5h$

), the spectra show elevated energy levels at low wavenumbers (

![]() $k_z \approx 2{-}4$

), a secondary peak at

$k_z \approx 2{-}4$

), a secondary peak at

![]() $k_z = 2\pi h$

and decay with increasing

$k_z = 2\pi h$

and decay with increasing

![]() $k_z$

. With increasing streamwise distance, the spectral energy progressively decreases until

$k_z$

. With increasing streamwise distance, the spectral energy progressively decreases until

![]() $s_t$

where the spectral signature is similar for

$s_t$

where the spectral signature is similar for

![]() $s \gt s_t$

. This reflects the natural relaxation of the boundary layer towards an equilibrium turbulent boundary layer, as residual harmonics of tripping are only visible at

$s \gt s_t$

. This reflects the natural relaxation of the boundary layer towards an equilibrium turbulent boundary layer, as residual harmonics of tripping are only visible at

![]() $s= 5h$

. Both case 2000 and 2150 exhibit a similar behaviour at large wavenumbers.

$s= 5h$

. Both case 2000 and 2150 exhibit a similar behaviour at large wavenumbers.

Figure 10. Spanwise energy spectra of velocity fluctuations

![]() $E_{\textit{uu}}$

for case 2000 (solid) and case 2150 (dashed) progressing from

$E_{\textit{uu}}$

for case 2000 (solid) and case 2150 (dashed) progressing from

![]() $s = 5h$

to

$s = 5h$

to

![]() $s = 85h$

, incremented by

$s = 85h$

, incremented by

![]() $\Delta s = 20h$

.

$\Delta s = 20h$

.

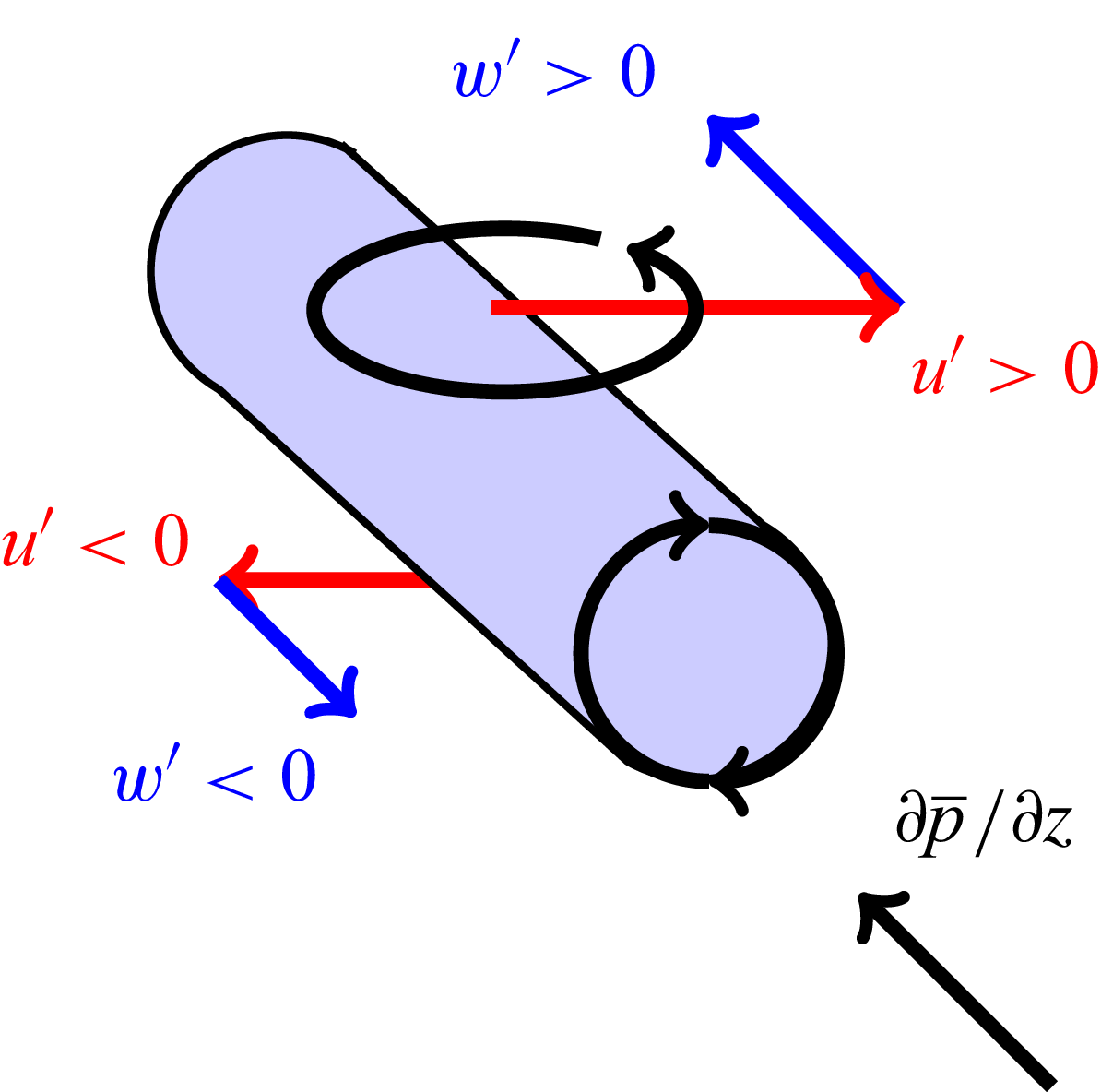

4.2. Crossflow profile

The presence of transverse curvature introduces a crossflow (secondary flow), as the initially 2-D boundary layer gains a spanwise component. Figure 11 shows a schematic of a 3-D boundary layer. The secondary flow is manifested as a non-uniform

![]() $w$

component of velocity and is a consequence of the spanwise pressure gradient

$w$

component of velocity and is a consequence of the spanwise pressure gradient

![]() $\partial \overline {p}/\partial {\zeta }$

in the boundary layer coupled with a wall-normal velocity gradient.

$\partial \overline {p}/\partial {\zeta }$

in the boundary layer coupled with a wall-normal velocity gradient.

Figure 11. Three-dimensional boundary layer schematic.

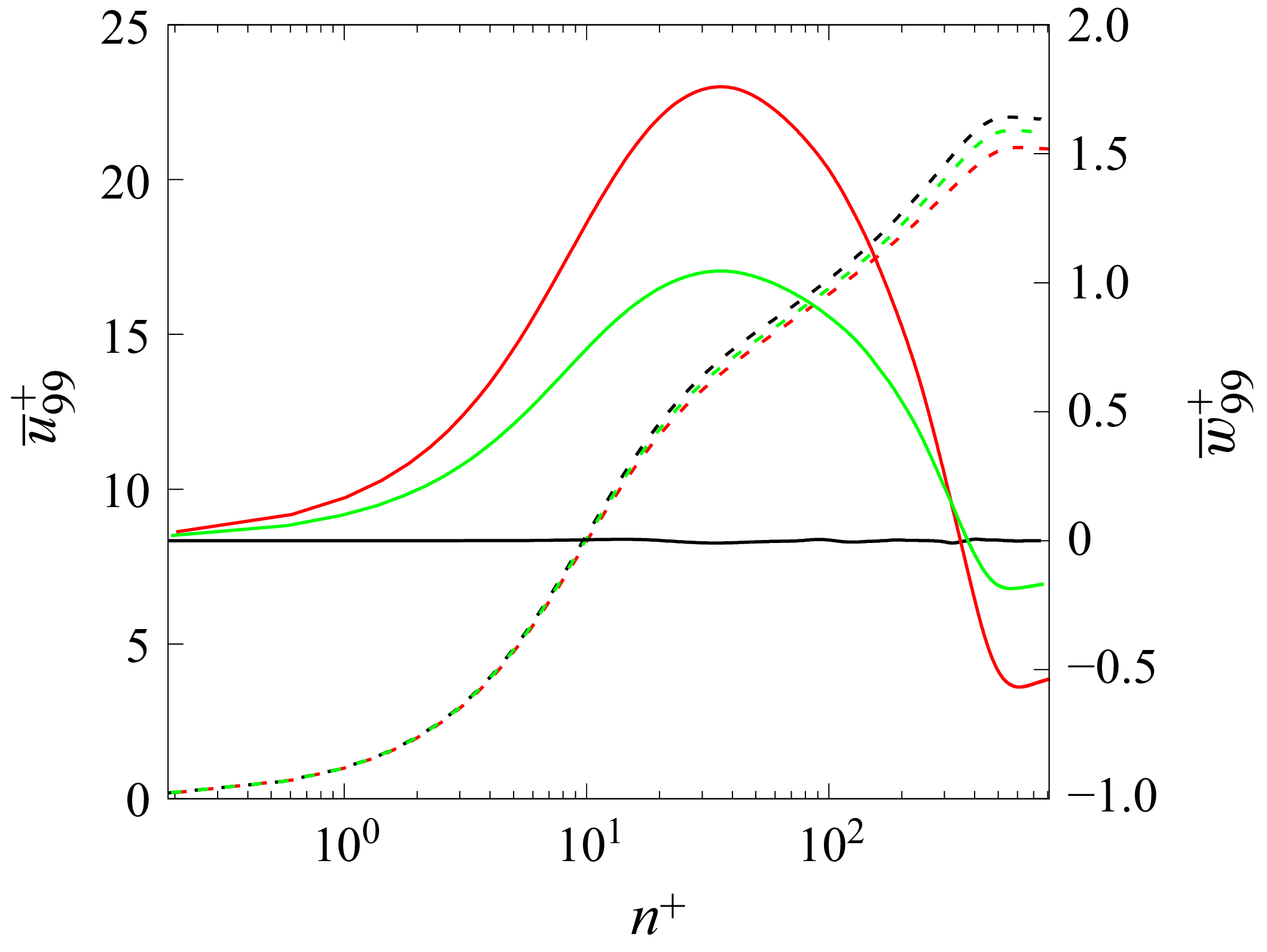

Figure 12. Streamwise (- - -) and spanwise (—) velocity profiles for case 2000 (black), case 2110 (green) and case 2150 (red) at

![]() $s = 140h$

.

$s = 140h$

.

Figure 12 shows the streamwise

![]() $\overline {u}_{99}^+$

and spanwise

$\overline {u}_{99}^+$

and spanwise

![]() $\overline {w}_{99}^+$

velocity profiles at

$\overline {w}_{99}^+$

velocity profiles at

![]() $s = 140h$

for case 2000 (ZPG at

$s = 140h$

for case 2000 (ZPG at

![]() $\textit{Re}_h = 2000$

), case 2110 (with

$\textit{Re}_h = 2000$

), case 2110 (with

![]() $R = 1000h$

spanwise curvature) and case 2150 (with

$R = 1000h$

spanwise curvature) and case 2150 (with

![]() $R = 500h$

spanwise curvature). The streamwise velocity profiles are similar and have a logarithmic layer in all the cases although the maximum value is highest in case 2000. The difference is more pronounced in the spanwise velocity profile. The spanwise velocity is negligible in case 2000 while it is not in cases with spanwise curvature. Here

$R = 500h$

spanwise curvature). The streamwise velocity profiles are similar and have a logarithmic layer in all the cases although the maximum value is highest in case 2000. The difference is more pronounced in the spanwise velocity profile. The spanwise velocity is negligible in case 2000 while it is not in cases with spanwise curvature. Here

![]() $\overline {w}_{99}^+$

increases from zero at the wall to a maximum at

$\overline {w}_{99}^+$

increases from zero at the wall to a maximum at

![]() $n^+ \approx 40$

. The location of this maximum corresponds to the bottom of the logarithmic layer. The spanwise velocity then decreases until the edge of the boundary layer. The formation of a crossflow in a spanwise pressure gradient field can be understood by considering the streamline-transverse momentum equation in the steady regime as listed in (3.3). Assuming homogeneity in the spanwise direction, a small variation in the streamwise direction and

$n^+ \approx 40$

. The location of this maximum corresponds to the bottom of the logarithmic layer. The spanwise velocity then decreases until the edge of the boundary layer. The formation of a crossflow in a spanwise pressure gradient field can be understood by considering the streamline-transverse momentum equation in the steady regime as listed in (3.3). Assuming homogeneity in the spanwise direction, a small variation in the streamwise direction and

![]() $v \approx 0$

:

$v \approx 0$

:

Viscous effects are negligible in the free stream, recovering the prescribed body force. Within the boundary layer, if

![]() $\overline {u}_{{\zeta }} = 0$

then

$\overline {u}_{{\zeta }} = 0$

then

![]() $\overline {u}_s^2/r = -f$

; however, since

$\overline {u}_s^2/r = -f$

; however, since

![]() $f$

is a constant, this equation can only be valid if the left-hand side is constant. More specifically, it can only be valid if

$f$

is a constant, this equation can only be valid if the left-hand side is constant. More specifically, it can only be valid if

![]() $\overline {u}_s$

is constant because if

$\overline {u}_s$

is constant because if

![]() $r$

varies,

$r$

varies,

![]() $\overline {u}_{{\zeta }}$

cannot be constant, hence, a contradiction. Therefore, a gradient of

$\overline {u}_{{\zeta }}$

cannot be constant, hence, a contradiction. Therefore, a gradient of

![]() $\overline {u}_s$

necessarily implies a non-zero and varying

$\overline {u}_s$

necessarily implies a non-zero and varying

![]() $\overline {u}_{{\zeta }}(n)$

within the boundary layer (

$\overline {u}_{{\zeta }}(n)$

within the boundary layer (

![]() $\overline {w}_{99} = 0$

by definition). This non-zero

$\overline {w}_{99} = 0$

by definition). This non-zero

![]() $\overline {u}_{{\zeta }}(n)$

is visible as a crossflow, also called secondary flow. The crossflow can be analytically interpreted by considering (3.3) in local streamline coordinates and neglecting viscous and turbulent stresses:

$\overline {u}_{{\zeta }}(n)$

is visible as a crossflow, also called secondary flow. The crossflow can be analytically interpreted by considering (3.3) in local streamline coordinates and neglecting viscous and turbulent stresses:

Intuition about the behaviour of

![]() $r(n)$

can be gained by considering the log layer where

$r(n)$

can be gained by considering the log layer where

![]() $\overline {u}_s^+ = ({1}/{\kappa })\ln (n^+) + B \Rightarrow r(n^+) = (Ru_\tau ^2/{U_\infty }^2)( ({1}/{\kappa })\ln (n^+)+B)^2$

, where

$\overline {u}_s^+ = ({1}/{\kappa })\ln (n^+) + B \Rightarrow r(n^+) = (Ru_\tau ^2/{U_\infty }^2)( ({1}/{\kappa })\ln (n^+)+B)^2$

, where

![]() $\kappa =0.41$

and

$\kappa =0.41$

and

![]() $B=5.2$

are constants from the logarithmic law of the wall. The angle of the streamwise axis (where

$B=5.2$

are constants from the logarithmic law of the wall. The angle of the streamwise axis (where

![]() $s$

is the streamwise coordinate from the start of curvature) is defined as

$s$

is the streamwise coordinate from the start of curvature) is defined as

Thus, at any point, the relative slip velocity (figure 14) between the free-stream velocity at

![]() $n \geqslant \delta _{99}$

and the velocity within the boundary layer at

$n \geqslant \delta _{99}$

and the velocity within the boundary layer at

![]() $n \lt \delta _{99}$

is

$n \lt \delta _{99}$

is

\begin{align} \overline {w}_{99}(s,n) &= \overline {u}_{99}(s,n) \sin\! \left(\frac {s{U_\infty }^2}{\overline {u}_{99}(s,n)^2 R}-\frac {s}{R}\right)\!, \end{align}

\begin{align} \overline {w}_{99}(s,n) &= \overline {u}_{99}(s,n) \sin\! \left(\frac {s{U_\infty }^2}{\overline {u}_{99}(s,n)^2 R}-\frac {s}{R}\right)\!, \end{align}

\begin{align} \overline {w}_{99}(s,n) &= \overline {u}_{99}(s,n) \sin\! \left(\frac {s}{R}\left(\frac {{U_\infty }^2}{\overline {u}_{99}(s,n)^2}-1\right)\right)\! . \end{align}

\begin{align} \overline {w}_{99}(s,n) &= \overline {u}_{99}(s,n) \sin\! \left(\frac {s}{R}\left(\frac {{U_\infty }^2}{\overline {u}_{99}(s,n)^2}-1\right)\right)\! . \end{align}

Similarly, the secondary flow can be derived in the viscous sublayer:

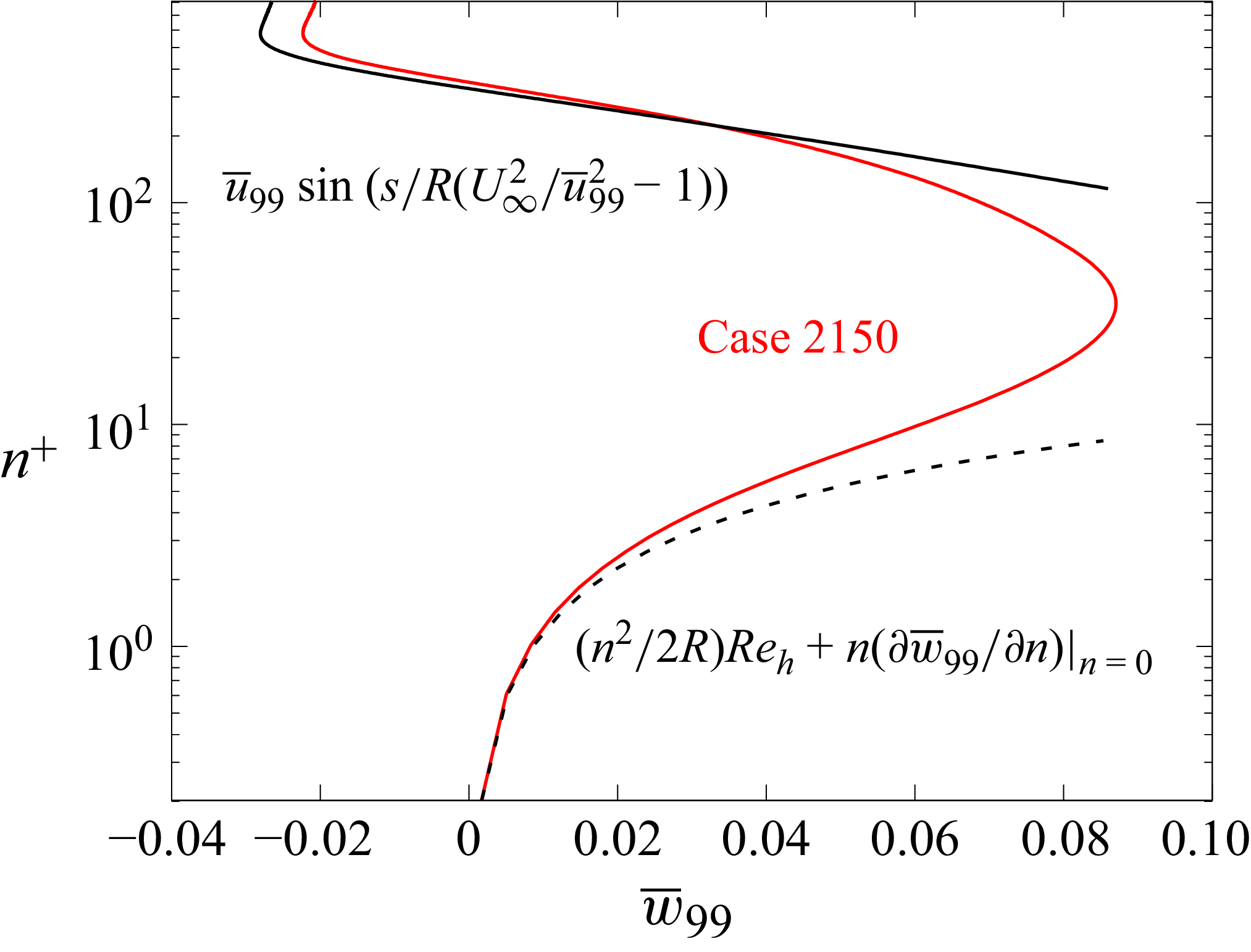

Figure 13 shows a comparison of the derived components of the secondary flow with the measured crossflow for

![]() $R = 500h, \textit{Re}_h = 2000, s = 145h$

. Good agreement is obtained in the log layer (4.9) and the viscous sublayer (4.10). The positive wall-normal velocity gradient implies that the local radius of curvature

$R = 500h, \textit{Re}_h = 2000, s = 145h$

. Good agreement is obtained in the log layer (4.9) and the viscous sublayer (4.10). The positive wall-normal velocity gradient implies that the local radius of curvature

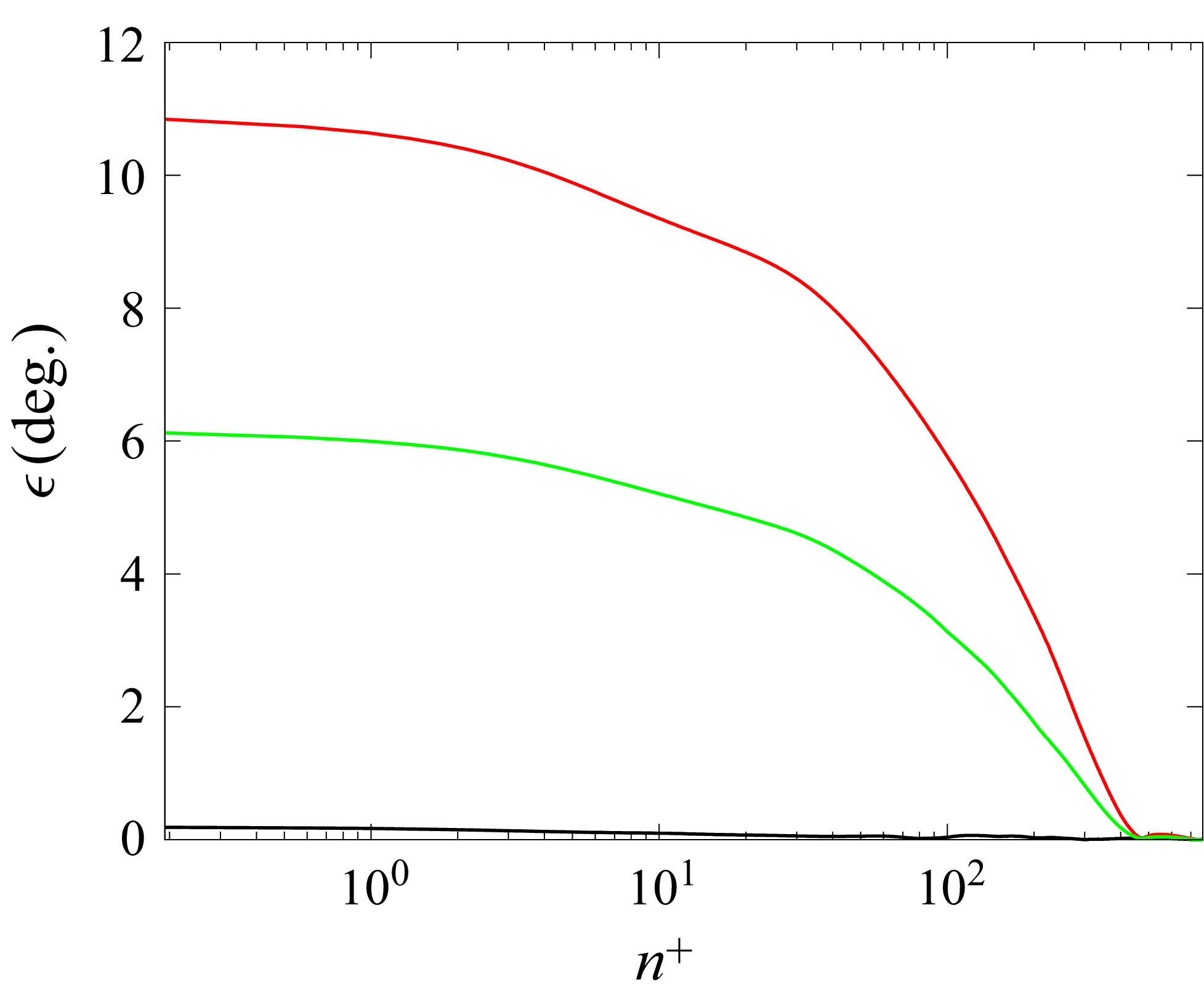

![]() $r$

must also increase to balance (4.3). Figure 15 shows the angle between the local velocity vector and the free-stream velocity vector along the domain for cases 2000, 2110 and 2150 (ZPG and prescribed spanwise free-stream curvature of

$r$

must also increase to balance (4.3). Figure 15 shows the angle between the local velocity vector and the free-stream velocity vector along the domain for cases 2000, 2110 and 2150 (ZPG and prescribed spanwise free-stream curvature of

![]() $R = 500h$

and

$R = 500h$

and

![]() $R = 1000h$

at

$R = 1000h$

at

![]() $\textit{Re}_h = 2000$

) defined by Cooke (Reference Cooke1958) as

$\textit{Re}_h = 2000$

) defined by Cooke (Reference Cooke1958) as

![]() $\epsilon = \cos ^{-1}(\langle \overline {u}_{99}(n), \overline {v}_{99}(n), \overline {w}_{99}(n) \rangle \boldsymbol{\cdot }\langle \overline {u}_{99}(\delta _{99}), \overline {v}_{99}(\delta _{99}), \overline {w}_{99}(\delta _{99}) \rangle )$

. As expected, the orientation of the velocity vector is constant throughout the entire profile in the absence of any external forcing. From the cases studied,

$\epsilon = \cos ^{-1}(\langle \overline {u}_{99}(n), \overline {v}_{99}(n), \overline {w}_{99}(n) \rangle \boldsymbol{\cdot }\langle \overline {u}_{99}(\delta _{99}), \overline {v}_{99}(\delta _{99}), \overline {w}_{99}(\delta _{99}) \rangle )$

. As expected, the orientation of the velocity vector is constant throughout the entire profile in the absence of any external forcing. From the cases studied,

![]() $\epsilon$

scales linearly with the curvature. The orientation of the velocity vectors start to converge towards the free-stream orientation more rapidly within the log layer.

$\epsilon$

scales linearly with the curvature. The orientation of the velocity vectors start to converge towards the free-stream orientation more rapidly within the log layer.

Figure 14. Comparison between the velocity vector within the boundary layer (blue) and at the boundary layer edge (red), emphasising that the orientation of the velocity vector within the boundary layer is not uniform in the presence of spanwise curvature.

Figure 15. Angle between local velocity vector and free-stream velocity vector for case 2000 (black), case 2110 (green) and case 2150 (red) at

![]() $s = 125h$

, showing increased curvature within the boundary layer.

$s = 125h$

, showing increased curvature within the boundary layer.

4.3. Velocity profiles

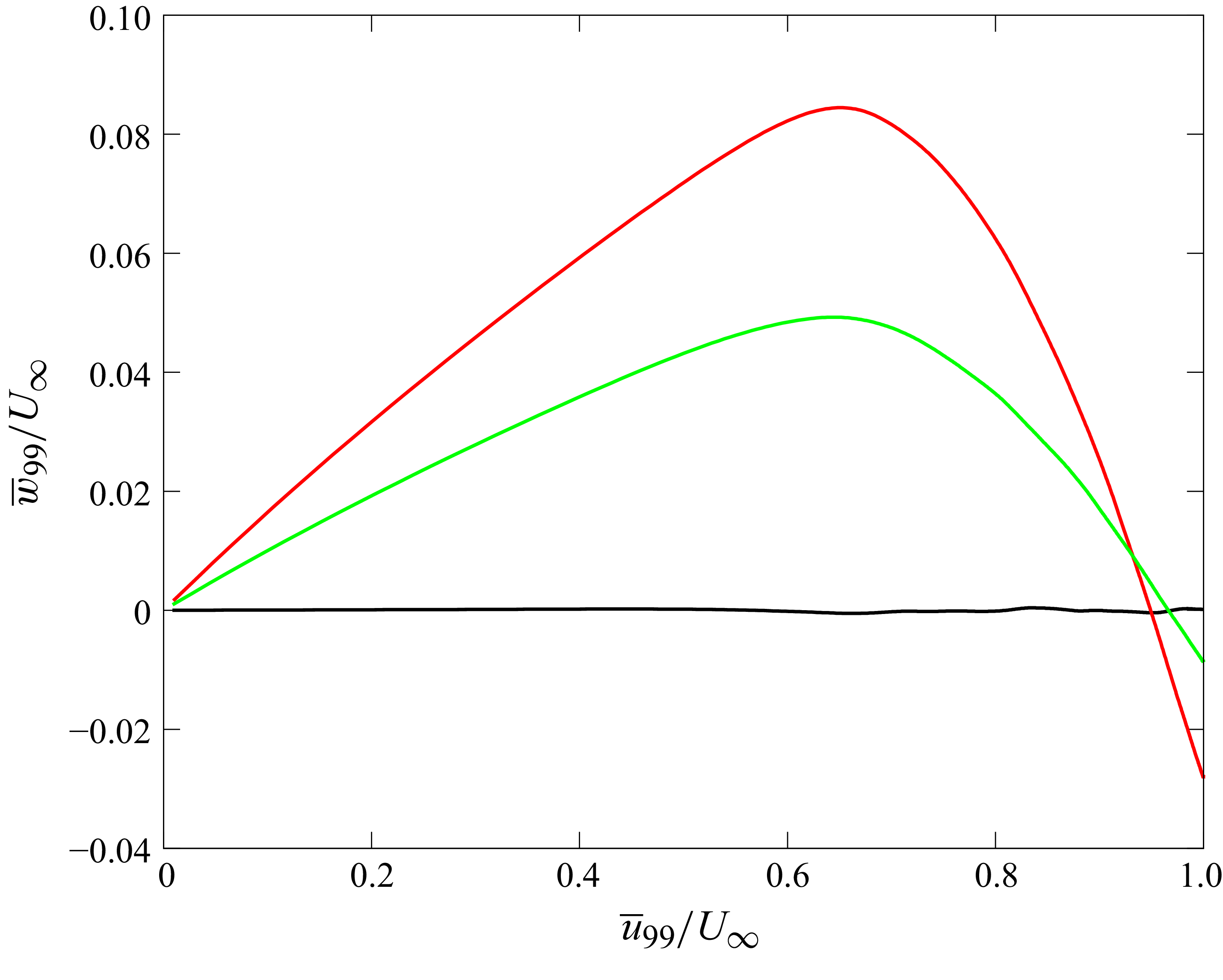

Figure 18 shows the hodograph highlighting the spanwise component of velocity versus the streamwise component in the

![]() $\delta _{99}$

-aligned coordinate system at

$\delta _{99}$

-aligned coordinate system at

![]() $s = 140h$

for cases 2000, 2110 and 2150. A large secondary flow is visible, which is maximum at

$s = 140h$

for cases 2000, 2110 and 2150. A large secondary flow is visible, which is maximum at

![]() $\overline {w}_{99}/{U_\infty } \approx 0.05$

at

$\overline {w}_{99}/{U_\infty } \approx 0.05$

at

![]() $\overline {u}_{99}/{U_\infty } \approx 0.65$

for case 2110 and

$\overline {u}_{99}/{U_\infty } \approx 0.65$

for case 2110 and

![]() $\overline {w}_{99}/{U_\infty } \approx 0.085$

at

$\overline {w}_{99}/{U_\infty } \approx 0.085$

at

![]() $\overline {u}_{99}/{U_\infty } \approx 0.7$

for case 2150. The spanwise velocity then decreases closer to the wall and outside the boundary layer.

$\overline {u}_{99}/{U_\infty } \approx 0.7$

for case 2150. The spanwise velocity then decreases closer to the wall and outside the boundary layer.

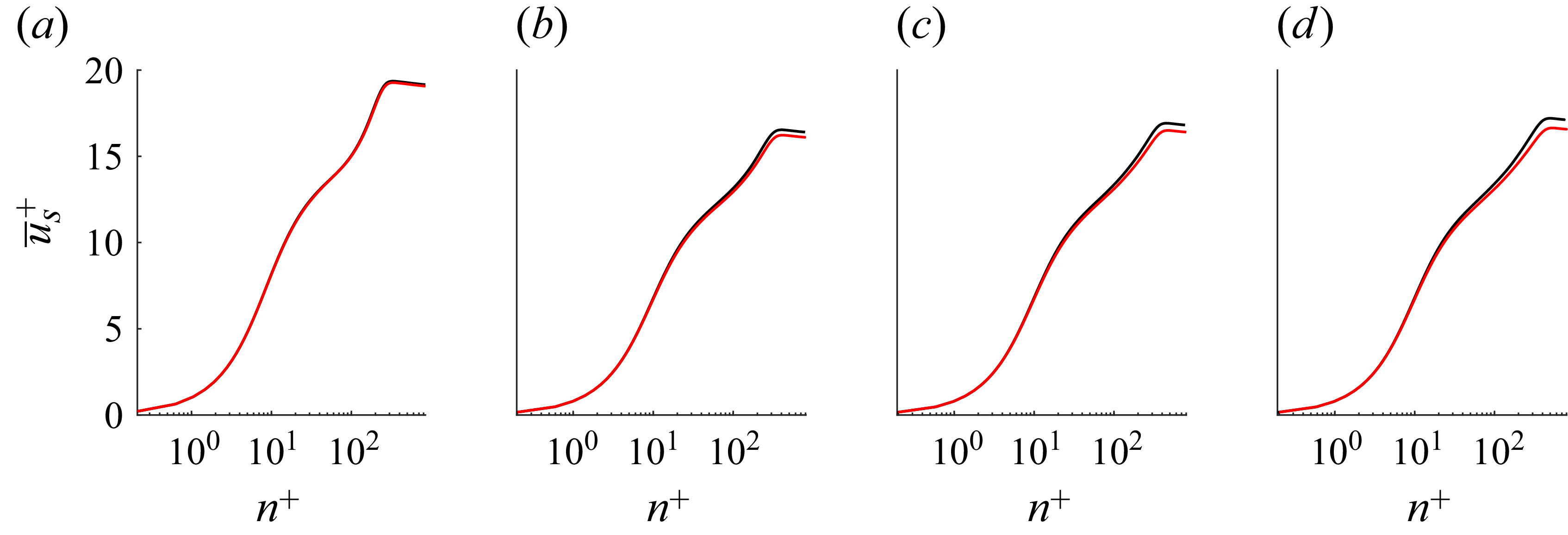

Figure 16. Mean velocity profiles for case 2000 (black) and case 2150 (red) at (a)

![]() $s = 25h$

, (b)

$s = 25h$

, (b)

![]() $s = 50h$

, (c)

$s = 50h$

, (c)

![]() $s = 75h$

, (d)

$s = 75h$

, (d)

![]() $s = 100h$

.

$s = 100h$

.

Figure 16 shows the velocity magnitude profiles downstream of the trip for cases 2000 and 2150 (base case and spanwise curvature,

![]() $\textit{Re}_h = 2000$

). In both cases, the boundary layer is initially perturbed and transitional. As curvature effects compound, the two cases start to diverge from each other, with the spanwise curvature case exhibiting a fuller profile. Figure 17 shows the deviation between the base case and the spanwise curvature cases. This deviation is calculated as the RMS of the difference between the two curves, as in (4.1). For both radii of curvature, a local maximum is observed in the vicinity of the trip because of the increased mixing of the recirculation and accelerated region due to the spanwise pressure gradient. The deviation becomes minimal at

$\textit{Re}_h = 2000$

). In both cases, the boundary layer is initially perturbed and transitional. As curvature effects compound, the two cases start to diverge from each other, with the spanwise curvature case exhibiting a fuller profile. Figure 17 shows the deviation between the base case and the spanwise curvature cases. This deviation is calculated as the RMS of the difference between the two curves, as in (4.1). For both radii of curvature, a local maximum is observed in the vicinity of the trip because of the increased mixing of the recirculation and accelerated region due to the spanwise pressure gradient. The deviation becomes minimal at

![]() $s \approx 20h$

and increases monotonically until the end of the domain. This suggests that the characteristic length necessary for the curvature to affect the profile is much longer than the length for the boundary layer to become turbulent.

$s \approx 20h$

and increases monotonically until the end of the domain. This suggests that the characteristic length necessary for the curvature to affect the profile is much longer than the length for the boundary layer to become turbulent.

Figure 17. Deviation between velocity profiles of case 1110 and case 1000 (green) and case 1150 and case 1000 (red).

Figure 18. Hodograph plot

![]() $\overline {w}_{99}$

vs

$\overline {w}_{99}$

vs

![]() $\overline {u}_{99}$

at

$\overline {u}_{99}$

at

![]() $s = 140h$

for case 2000 (black), case 2110 (green) and case 2150 (red).

$s = 140h$

for case 2000 (black), case 2110 (green) and case 2150 (red).

4.4. Integral boundary layer parameters

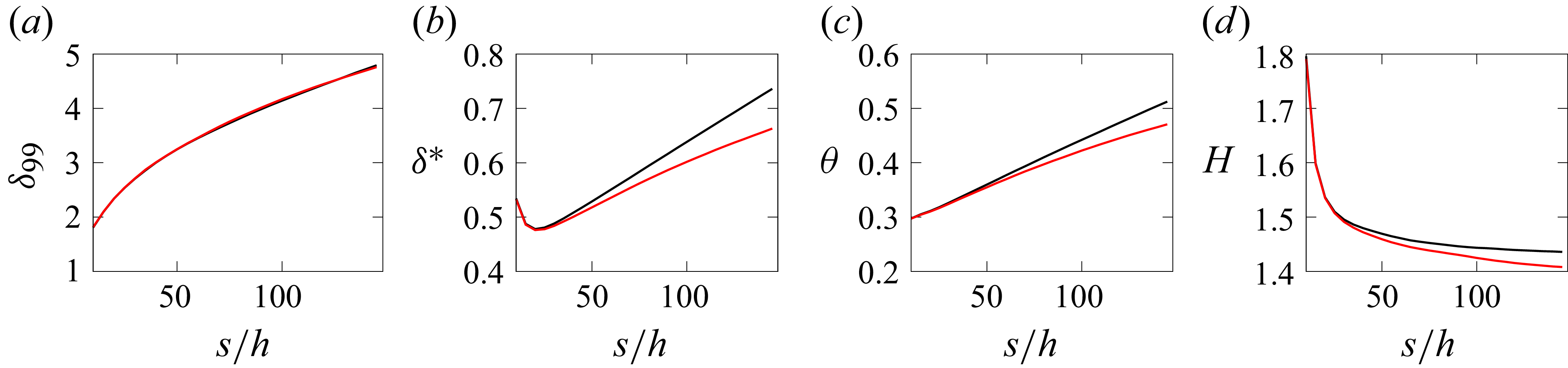

Figure 19 shows the evolution of the

![]() $99{{\rm th}}$

percentile boundary layer thickness

$99{{\rm th}}$

percentile boundary layer thickness

![]() $\delta _{99}$

, the displacement thickness

$\delta _{99}$

, the displacement thickness

![]() $\delta ^{*}$

, the momentum thickness

$\delta ^{*}$

, the momentum thickness

![]() $\theta$

and the shape factor

$\theta$

and the shape factor

![]() $H = \delta ^{*}/\theta$

, downstream of the trip for cases with and without spanwise curvature at

$H = \delta ^{*}/\theta$

, downstream of the trip for cases with and without spanwise curvature at

![]() $\textit{Re}_h = 2000$

. These quantities are computed using the methodology proposed by Griffin, Fu & Moin (Reference Griffin, Fu and Moin2021). Both cases 2000 and 2150 have similar values of

$\textit{Re}_h = 2000$

. These quantities are computed using the methodology proposed by Griffin, Fu & Moin (Reference Griffin, Fu and Moin2021). Both cases 2000 and 2150 have similar values of

![]() $\delta _{99}$

, whereas

$\delta _{99}$

, whereas

![]() $\delta ^{*}$

,

$\delta ^{*}$

,

![]() $\theta$

and

$\theta$

and

![]() $H$

are lower after

$H$

are lower after

![]() $s_t$

in the presence of spanwise curvature compared with the baseline case. Here

$s_t$

in the presence of spanwise curvature compared with the baseline case. Here

![]() $\delta ^{*}$

,

$\delta ^{*}$

,

![]() $\theta$

and

$\theta$

and

![]() $H$

exhibit no differences between the two cases until

$H$

exhibit no differences between the two cases until

![]() $s_t$

, matching the discussion in § 4.1. The sharp decrease in

$s_t$

, matching the discussion in § 4.1. The sharp decrease in

![]() $H$

in the transitionary region until

$H$

in the transitionary region until

![]() $s_t$

is consistent with the development of a turbulent boundary layer. The lower shape factor observed in the case with curvature is indicative of a fuller velocity profile (visible in figure 16). The lower shape profile of the case with spanwise curvature indicates that the three-dimensionality of the boundary layer allows the boundary layer to have higher momentum deficit in a smaller region.

$s_t$

is consistent with the development of a turbulent boundary layer. The lower shape factor observed in the case with curvature is indicative of a fuller velocity profile (visible in figure 16). The lower shape profile of the case with spanwise curvature indicates that the three-dimensionality of the boundary layer allows the boundary layer to have higher momentum deficit in a smaller region.

Figure 19. Boundary layer evolution for case 2000 (black) and case 2150 (red) showing (a)

![]() $\delta _{99}$

thickness, (b) displacement thickness, (c) momentum thickness, (d) shape factor.

$\delta _{99}$

thickness, (b) displacement thickness, (c) momentum thickness, (d) shape factor.

4.5. Turbulent stresses

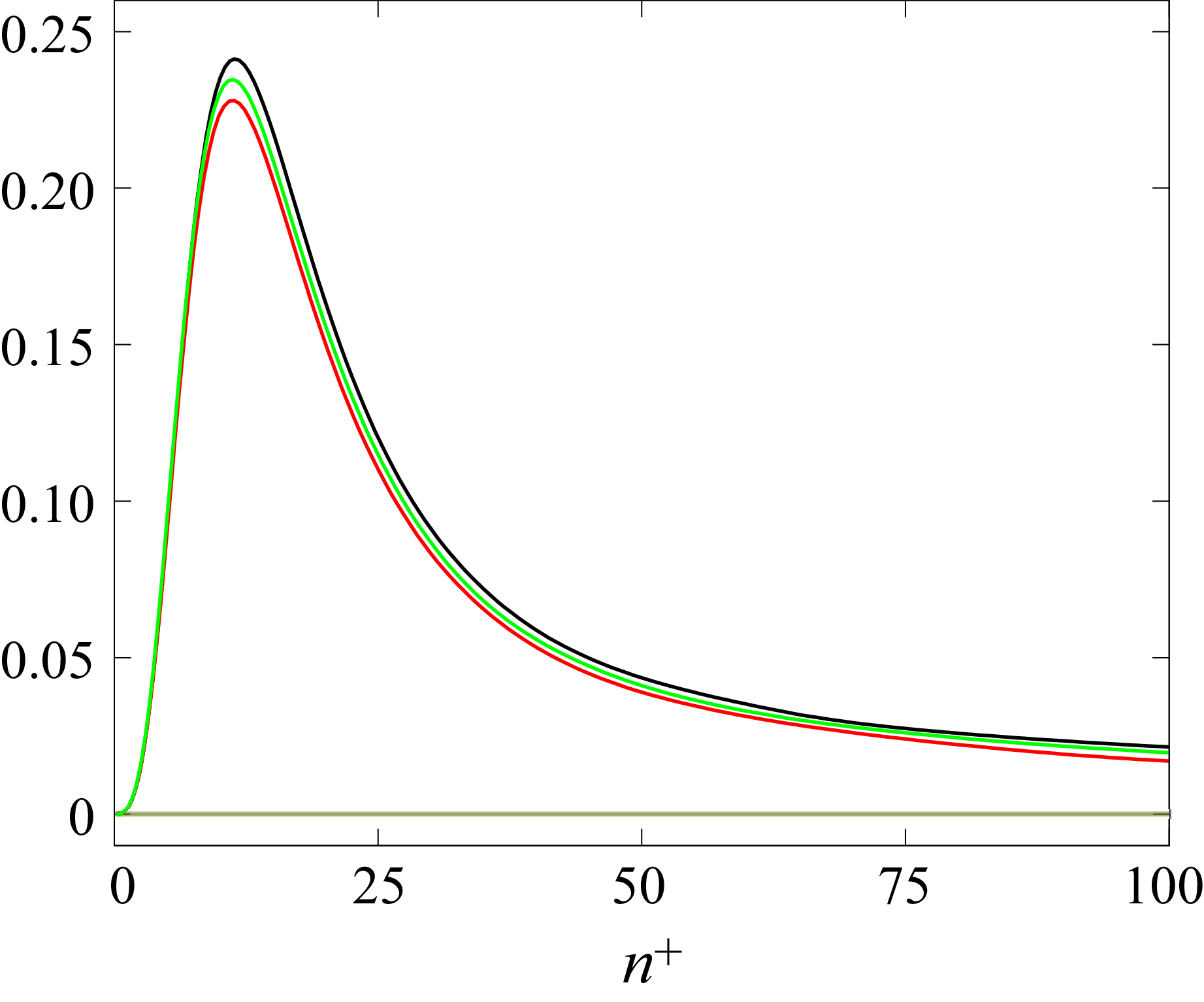

The diagonal Reynolds stress components for cases 2000, 2110 and 2150 are shown in figure 20, and the off-diagonal Reynolds stress terms for the same cases are shown in figure 21. Here

![]() $\overline {u_n'^2}$

peaks at the bottom of the log layer with slightly decreasing magnitudes as the radius of curvature decreases;

$\overline {u_n'^2}$

peaks at the bottom of the log layer with slightly decreasing magnitudes as the radius of curvature decreases;

![]() $\overline {u_n'^2}$

,

$\overline {u_n'^2}$

,

![]() $\overline {u_\zeta '^2}$

and

$\overline {u_\zeta '^2}$

and

![]() $\overline {u_s'u_n'}$

all have a single maximum at the location of maximum crossflow (figure 12). This maximum is highest for case 2000, followed by case 2110 and lowest for case 2150. Here

$\overline {u_s'u_n'}$

all have a single maximum at the location of maximum crossflow (figure 12). This maximum is highest for case 2000, followed by case 2110 and lowest for case 2150. Here

![]() $\overline {u_n'^2}$

and

$\overline {u_n'^2}$

and

![]() $\overline {u_n'u_\zeta '}$

show deficits of

$\overline {u_n'u_\zeta '}$

show deficits of

![]() $5\%$

in case 2110 and

$5\%$

in case 2110 and

![]() $10\,\%$

in case 2150 compared with case 2000, while

$10\,\%$

in case 2150 compared with case 2000, while

![]() $\overline {u_\zeta '^2}$

exhibits a reduction of

$\overline {u_\zeta '^2}$

exhibits a reduction of

![]() $2\,\%$

and

$2\,\%$

and

![]() $4\,\%$

;

$4\,\%$

;

![]() $\overline {u_s'u_{{\zeta }}'}$

and

$\overline {u_s'u_{{\zeta }}'}$

and

![]() $\overline {u_n'u_{{\zeta }}'}$

show a reverse trend, with case 2150 having a maximum around twice the value of case 2110. In addition, these two components are not negligible compared with

$\overline {u_n'u_{{\zeta }}'}$

show a reverse trend, with case 2150 having a maximum around twice the value of case 2110. In addition, these two components are not negligible compared with

![]() $\overline {u_s'u_n'}$

in the presence of spanwise curvature. The value of

$\overline {u_s'u_n'}$

in the presence of spanwise curvature. The value of

![]() $\overline {u_n'u_{{\zeta }}'}$

is slightly lower than

$\overline {u_n'u_{{\zeta }}'}$

is slightly lower than

![]() $\overline {u_s'u_{{\zeta }}'}$

that is

$\overline {u_s'u_{{\zeta }}'}$

that is

![]() ${\sim} 25\,\%$

of

${\sim} 25\,\%$

of

![]() $\overline {u_s'u_n'}$

for case 2150. The maxima of

$\overline {u_s'u_n'}$

for case 2150. The maxima of

![]() $\overline {u_s'u_{{\zeta }}'}$

and

$\overline {u_s'u_{{\zeta }}'}$

and

![]() $\overline {u_n'u_{{\zeta }}'}$

for case 2150 are around twice the value of case 2110, suggesting that the value of these components scales with the radius of curvature.

$\overline {u_n'u_{{\zeta }}'}$

for case 2150 are around twice the value of case 2110, suggesting that the value of these components scales with the radius of curvature.

Figure 20. Reynolds stress profiles for case 2000 (black), case 2110 (green) and case 2150 (red), showing (a)

![]() $\overline {u_s'^2}^+$

, (b)

$\overline {u_s'^2}^+$

, (b)

![]() $\overline {u_n'^2}^+$

, (c)

$\overline {u_n'^2}^+$

, (c)

![]() $\overline {u_\zeta '^2}^+$

at

$\overline {u_\zeta '^2}^+$

at

![]() $s = 145h$

.

$s = 145h$

.

Figure 21. Reynolds stress profiles for case 2000 (black), case 2110 (green) and case 2150 (red), showing (a)

![]() $\overline {u_s'u_n'}^+$

, (b)

$\overline {u_s'u_n'}^+$

, (b)

![]() $\overline {u_s'u_{{\zeta }}'}^+$

, (c)

$\overline {u_s'u_{{\zeta }}'}^+$

, (c)

![]() $\overline {u_n'u_{{\zeta }}'}^+$

at

$\overline {u_n'u_{{\zeta }}'}^+$

at

![]() $s = 145h$

.

$s = 145h$

.

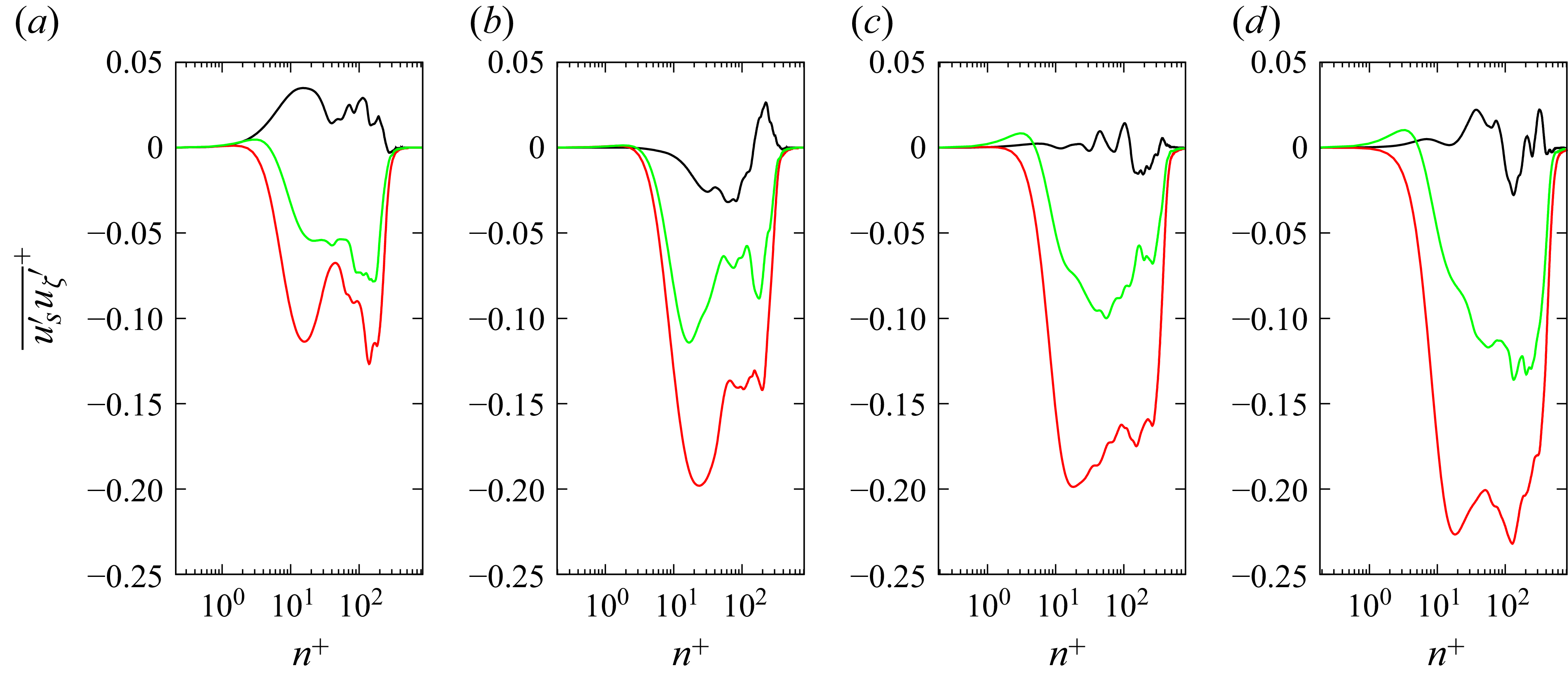

Figure 22. Profiles of Reynolds stress tensor component

![]() $\overline {u_s'u_{{\zeta }}'}^+$

for case 2000 (black), case 2110 (green) and case 2150 (red) at (a)

$\overline {u_s'u_{{\zeta }}'}^+$

for case 2000 (black), case 2110 (green) and case 2150 (red) at (a)

![]() $s = 25h$

, (b)

$s = 25h$

, (b)

![]() $s=50h$

, (c)

$s=50h$

, (c)

![]() $s=100h$

, (d)

$s=100h$

, (d)

![]() $s=145h$

.

$s=145h$

.

Figure 22 shows the evolution of the profiles of

![]() $\overline {u_s'u_{{\zeta }}'}^+$

downstream of the trip for cases 2000, 2110 and 2150 (base case and spanwise curvatures

$\overline {u_s'u_{{\zeta }}'}^+$

downstream of the trip for cases 2000, 2110 and 2150 (base case and spanwise curvatures

![]() $R = 1000h$

and

$R = 1000h$

and

![]() $R = 500h$

at

$R = 500h$

at

![]() $\textit{Re}_h = 2000$

). The magnitude near

$\textit{Re}_h = 2000$

). The magnitude near

![]() $\overline {u_s'u_{{\zeta }}'}^+$

is zero close to the wall where viscous stresses dominate. While

$\overline {u_s'u_{{\zeta }}'}^+$

is zero close to the wall where viscous stresses dominate. While

![]() $\overline {u_s'u_{{\zeta }}'}$

is negligible in the case without a pressure gradient, the term increases in the spanwise case near the end of the viscous sublayer starting from

$\overline {u_s'u_{{\zeta }}'}$

is negligible in the case without a pressure gradient, the term increases in the spanwise case near the end of the viscous sublayer starting from

![]() $n^+ \approx 5$

. Beyond

$n^+ \approx 5$

. Beyond

![]() $s_t$

, the magnitude of

$s_t$

, the magnitude of

![]() $\overline {u_s'u_{{\zeta }}'}$

increases as curvature effects compound.

$\overline {u_s'u_{{\zeta }}'}$

increases as curvature effects compound.

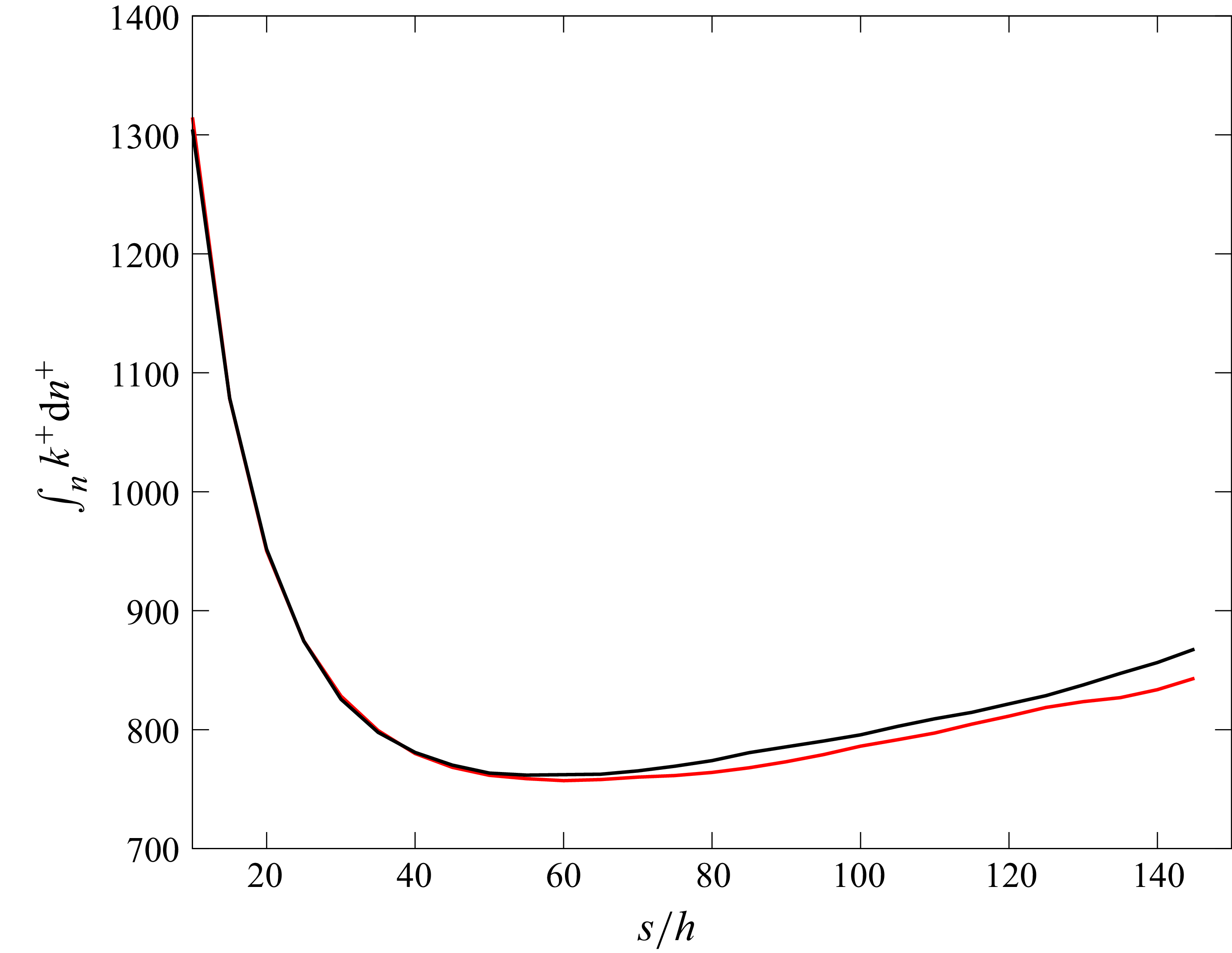

Figure 23. Evolution of the integral of turbulent kinetic energy for case 2000 (black), case 2110 (green) and case 2150 (red) (

![]() $\textit{Re}_h = 2000$

, baseline and spanwise curvature radii

$\textit{Re}_h = 2000$

, baseline and spanwise curvature radii

![]() $R = 1000h, 500h$

).

$R = 1000h, 500h$

).

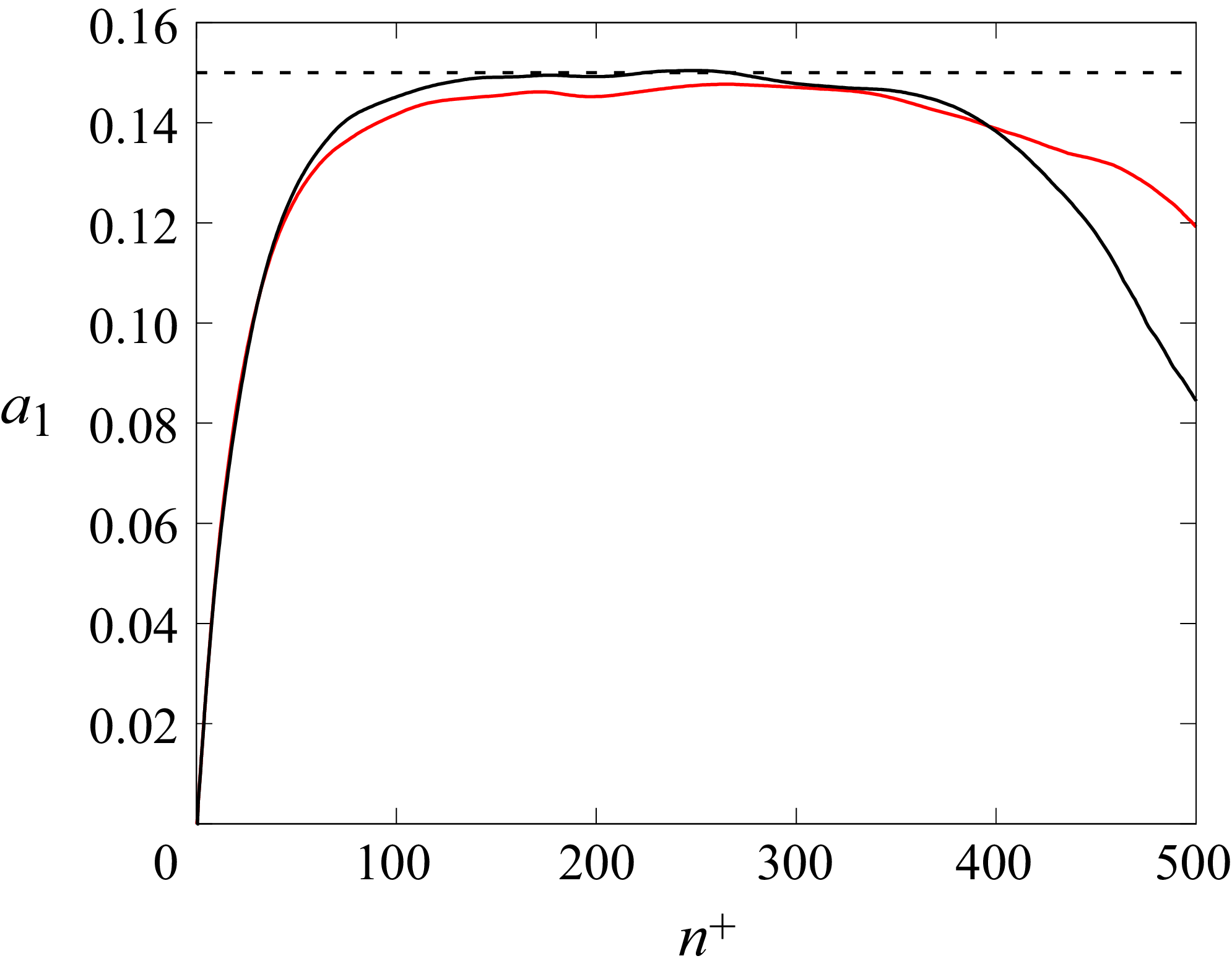

The total energy in the boundary layer can be studied via normalised turbulent kinetic energy (TKE)

![]() $k^+ = ({1}/{2}) \overline {u_i'u_i'}/u_\tau ^2$

integrated in the wall-normal direction. This quantity is shown in figure 23 for the baseline case and with spanwise curvature at

$k^+ = ({1}/{2}) \overline {u_i'u_i'}/u_\tau ^2$

integrated in the wall-normal direction. This quantity is shown in figure 23 for the baseline case and with spanwise curvature at

![]() $\textit{Re}_h = 2000$

. For all cases,

$\textit{Re}_h = 2000$

. For all cases,

![]() $\int k^+$

is highest in the wake of the trip, decreases to a minimum at

$\int k^+$

is highest in the wake of the trip, decreases to a minimum at

![]() $s_t$

(determined in § 4.1) and increases until the end of the domain. The high initial values are due to the perturbation created by the trip. The decay is associated with a dissipation of the wake of the trips. The increase in

$s_t$

(determined in § 4.1) and increases until the end of the domain. The high initial values are due to the perturbation created by the trip. The decay is associated with a dissipation of the wake of the trips. The increase in

![]() $k^+$

for

$k^+$

for

![]() $s \gt {s_t}$

can be attributed to the development of the turbulent boundary layer. Turbulent kinetic energy within the boundary layer decreases in the presence of spanwise curvature, which follows the reduction of the diagonal stresses (figure 20). This analysis can be continued by examining the TKE budget equation, which in Cartesian coordinates, is

$s \gt {s_t}$

can be attributed to the development of the turbulent boundary layer. Turbulent kinetic energy within the boundary layer decreases in the presence of spanwise curvature, which follows the reduction of the diagonal stresses (figure 20). This analysis can be continued by examining the TKE budget equation, which in Cartesian coordinates, is

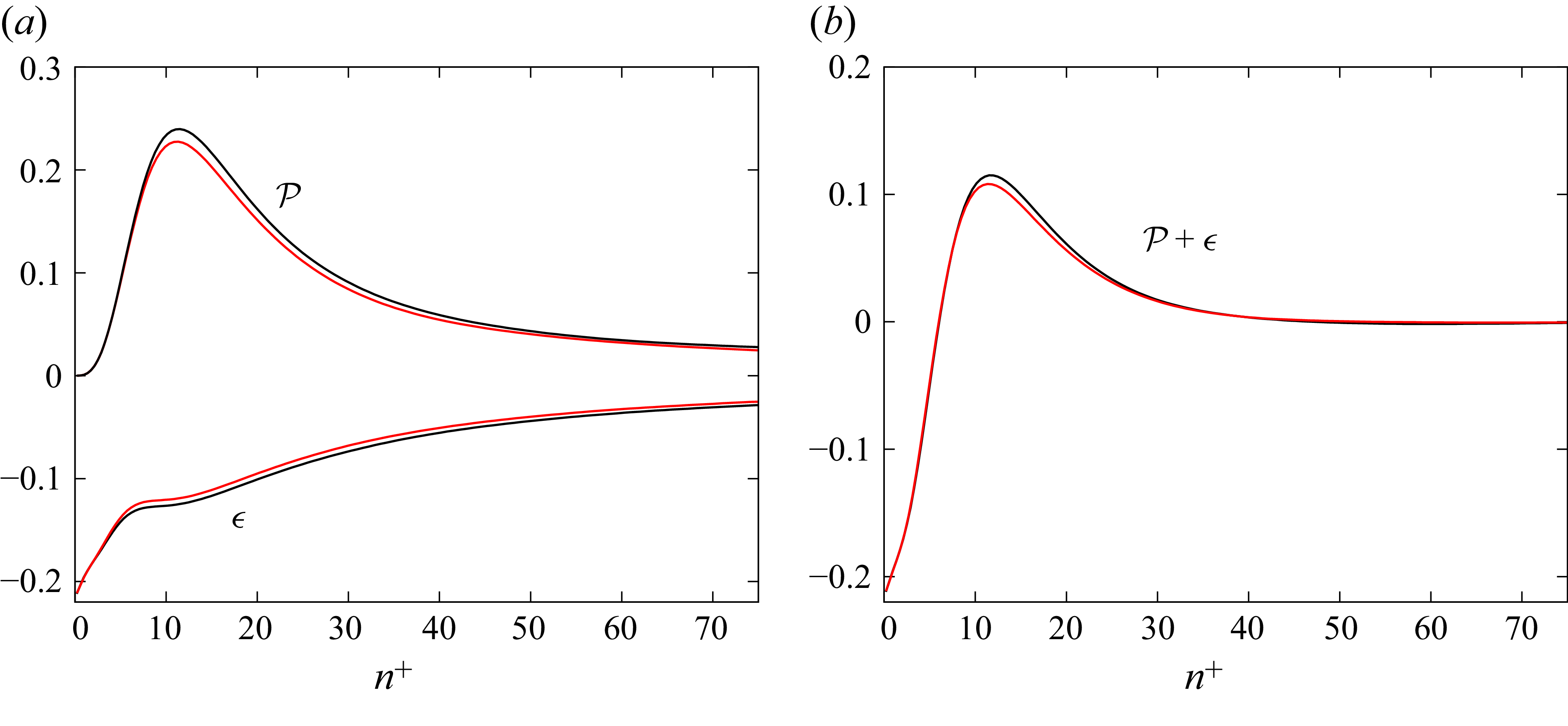

where

![]() $f_i$

is the externally applied body force and

$f_i$

is the externally applied body force and

![]() $T_i$

is the turbulent transport term encompassing viscous diffusion (

$T_i$

is the turbulent transport term encompassing viscous diffusion (

![]() $-\nu \partial _i k$

), turbulent convection (

$-\nu \partial _i k$

), turbulent convection (

![]() $({1}/{2})\overline {u_j'u_j'u_i'}$

) and density-normalised pressure transport (

$({1}/{2})\overline {u_j'u_j'u_i'}$

) and density-normalised pressure transport (

![]() $\overline {p'u_i'}$

). The current application considers a steady flow with spanwise homogeneity and body forces in

$\overline {p'u_i'}$

). The current application considers a steady flow with spanwise homogeneity and body forces in

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $z$

that are constant in

$z$

that are constant in

![]() $y$

; after applying continuity, (4.11) can be rewritten in the form

$y$

; after applying continuity, (4.11) can be rewritten in the form

The total TKE along a profile can be evaluated by integrating in the wall-normal direction from the wall

![]() $y=0$

to some location in the free stream

$y=0$

to some location in the free stream

![]() $y \gt \delta _{99} = y^*$

:

$y \gt \delta _{99} = y^*$

:

The no-slip and no-penetration boundary conditions at the wall and the laminar conditions in the free stream coupled with the growth of the boundary layer in

![]() $x$

occurring on a much larger length scale than the thickness of the boundary layer

$x$

occurring on a much larger length scale than the thickness of the boundary layer

![]() $\delta$

yield an integrated balance between production, dissipation and molecular diffusion due to the wall (shown to be small by figure 20):

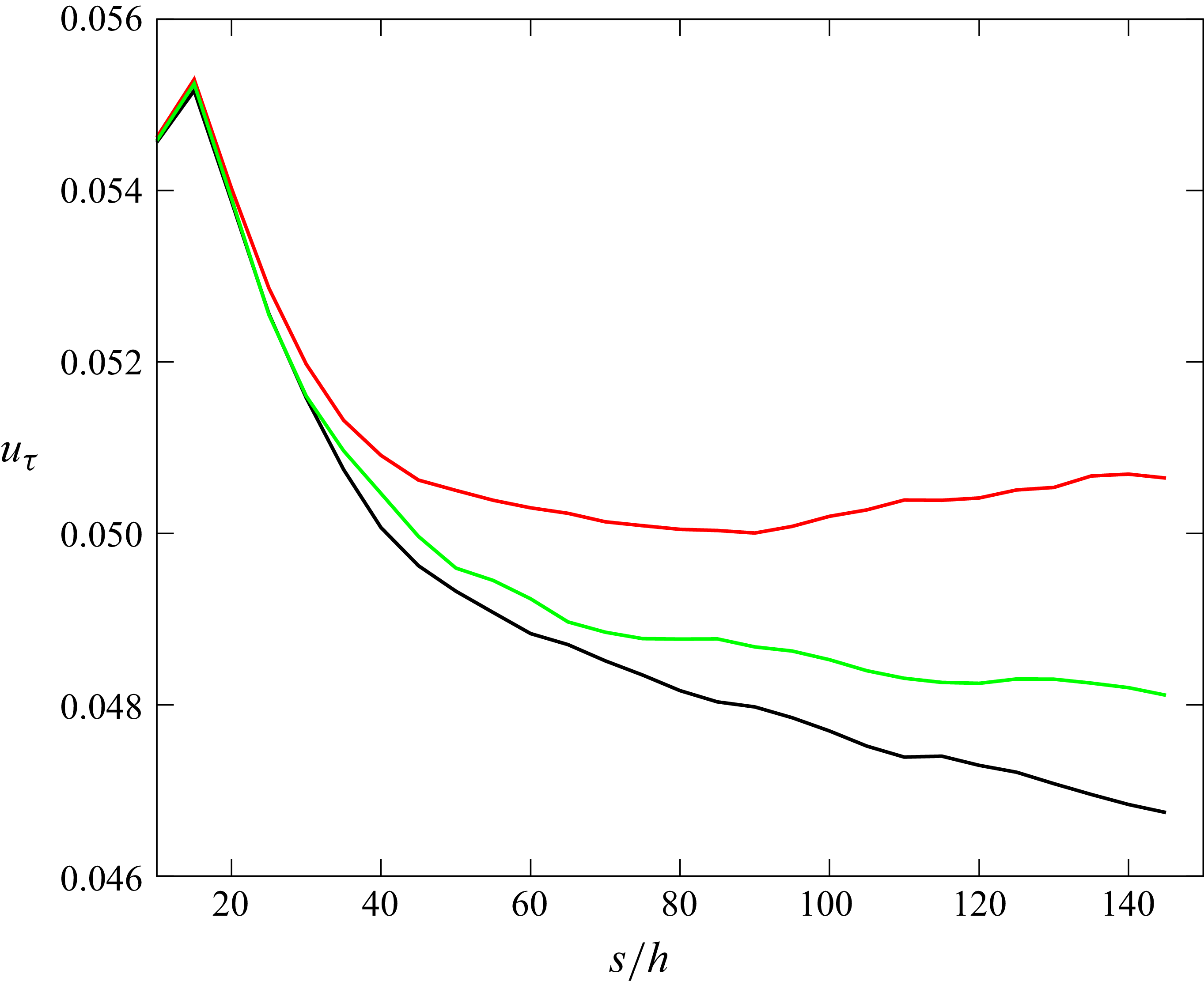

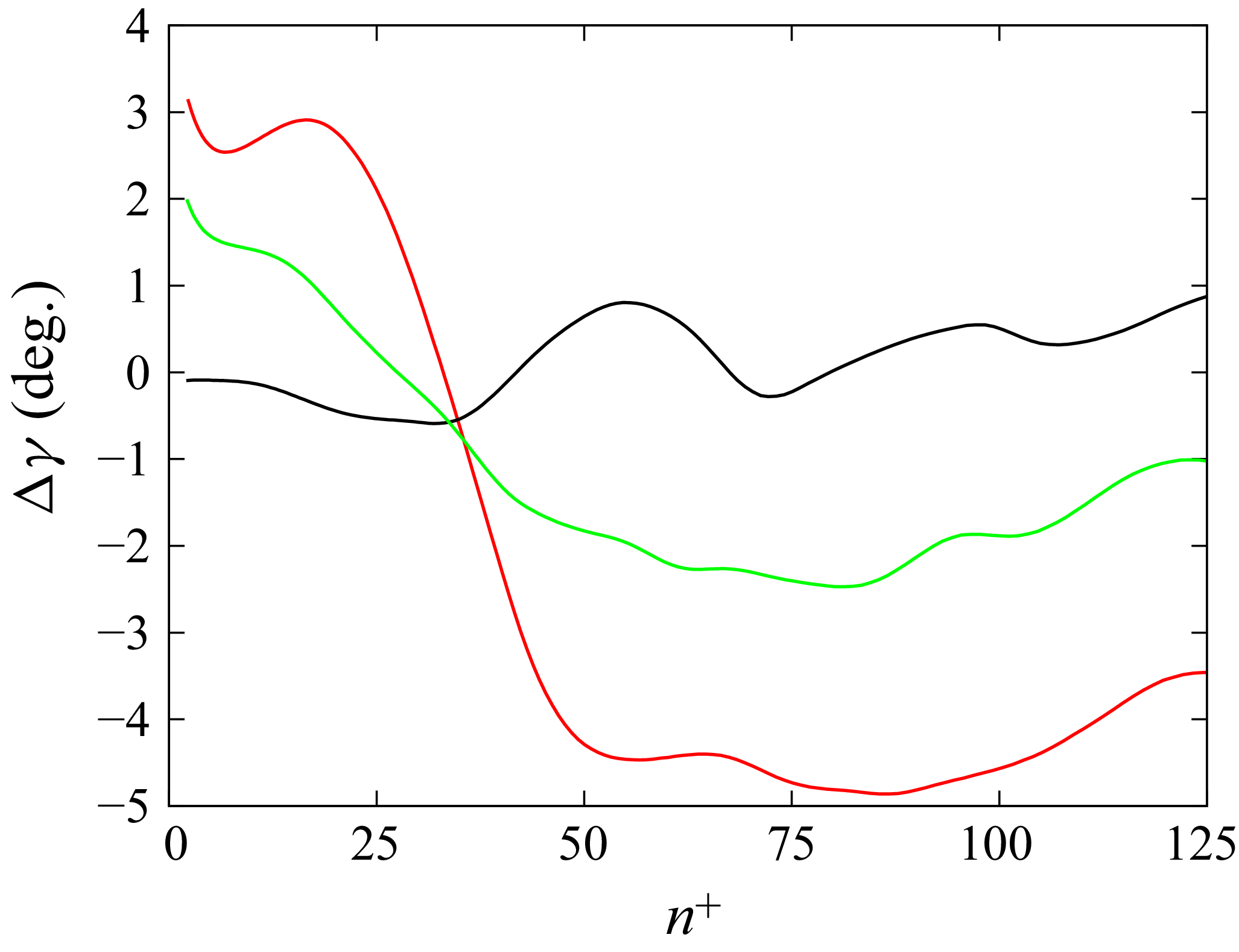

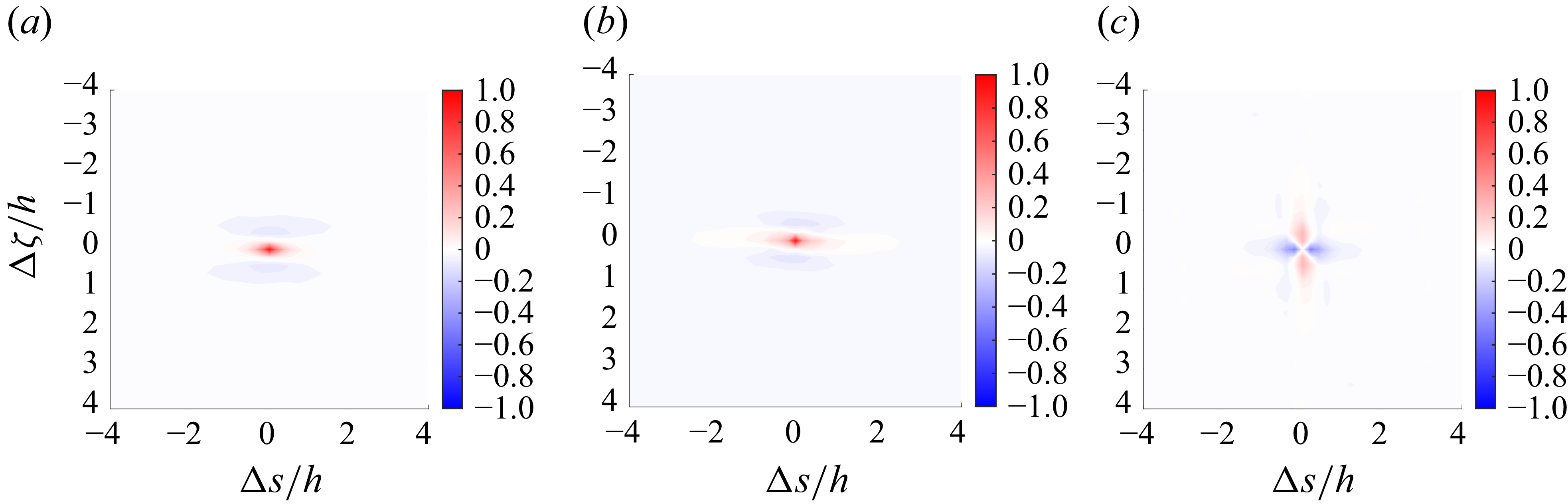

$\delta$