Introduction

The current wave of autocratization around the world is changing how billions of citizens experience domestic and world politics, and poses a profound challenge to the global architecture long seen to structure international politics: the liberal rules-based international order. To date, two countries – China and Russia – have dominated explanations of this trend. There is, however, a growing recognition that a much wider set of states shape current global trends away from democratic government and the post–Second World War system. This includes democracies long taken to be stable, such as India and the United States. Given their sheer size in terms of population – representing more than a fifth of all people on the planet – democratic decay in these polities will have a profound effect on global politics and democracy. Yet it is not only great and superpowers that are shaping current trends. A group of less prominent states are also contributing to a shift away from the liberal order at both the domestic and global level. The combined impact of the strategies employed by countries such as Türkiye, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Venezuela, for example, sustain some of the world’s deadliest conflicts, destabilize regional politics, and undermine the commitment of multilateral institutions to upholding democratic standards. In terms of their wealth and international influence, many of these states fall into the category of “middle-powers” – a term that became popular in International Relations following the end of the Cold War, which is once again gaining prominence.

The concept of middle-power has been the subject of considerable debate, but remains loosely defined and overly focused on democratic countries. At minimum, it refers to states that have mid-level military and/or economic capacity. Such states can therefore be powerful forces in their region, but do not qualify as global major powers. According to George Glazebrook’s early framing (Reference Glazebrook1947: 307), these states “make no claim to the title of great power, but have been shown to be capable of exerting a degree of strength and influence not found in the small powers”. Scholars have disagreed on whether to define middle-powers solely on the basis of their capabilities or with regard to the behavior they manifest internationally.Footnote 1 There has nonetheless been a general consensus about their core features. Traditional democratic middle-powers were seen as liberal internationalists and stabilizers, defending multilateralism and projecting liberal-democratic values abroad to win more legitimacy and international influence (Kutlay and Onis Reference Kutlay and Öniş2021; Sandal Reference Sandal2014). The most studied middle-powers of the 1990s, such as Australia and Canada, were argued to largely act benignly abroad. It is thus no coincidence that classic middle-power theory gained traction during periods when the global order was favorable to the liberal internationalist foreign policy these states pursued, that is, following the end of the Second World War and during the supposed triumph of liberal democracy in the early 1990s.

The countries that have risen to prominence in the last fifteen years have similar capabilities to the classic set of middle-powers discussed by the likes of Andrew Cooper and Richard Higgott (Cooper et al. Reference Cooper, Higgott and Nossal1993) but feature one major difference: they are not democratic. This includes states that are clearly authoritarian, such as Saudi Arabia and Türkiye, and countries that are moving away from democracy, such as Indonesia and Mexico. To reflect this, we refer to both autocratic and autocratizing middle-powers, but often simply refer to these cases as “authoritarian” states to avoid repetition.

It is critical to understand how these rising middle-powers operate, especially given their prominence in regions of wider geostrategic significance such as the Middle East. Doing so requires revising traditional middle-power theory, however. On the one hand, while the literature that has developed to explain the foreign policy of countries such as Canada and Norway has valuable insights for understanding their authoritarian counterparts, it is unlikely to fully capture their motivations and impact. Indeed, traditional middle-power theory explicitly made this point: it was premised on the idea that a state’s foreign policy and international behavior are fundamentally shaped by domestic characteristics, including regime type. Authoritarian states that are predominantly focused on securing regime survival and deploy repressive strategies to achieve this should be expected to employ a different kind of foreign policy. On the other hand, the international context in which authoritarian middle-powers now operate is very different to that of the 1990s. A decades-long process of democratic decline has emboldened authoritarian strategies and alliances. In today’s increasingly authoritarian global context, where a growing number of actors reject the imposition of democratic norms and standards – including countries historically viewed as democratic superpowers such as the United States – authoritarian middle-powers have greater agency.

This trend is further reinforced by the increasingly multipolar nature of the international system. The decline of American hegemony signifies not only a retreat from its role as a standard-bearer of liberal democracy, but also a shift toward a more fragmented international landscape.Footnote 2 In turn, this evolving global context affords greater latitude to middle-powers to assert their interests internationally (Abbondanza and Wilkins Reference Abbondanza and Wilkins2022: 4; Aydin-Duzgit et al. Reference Aydın-Düzgit, Kutlay and Keyman2025), particularly within their respective regions. We therefore need to revise our assumptions and theory regarding mid-sized authoritarian states’ international relations in line with these changes in domestic and international contexts.

To the best of our knowledge, this Element represents the first attempt to do this systematically from a global perspective. It addresses why and how a broad range of authoritarian middle-powers engage abroad, making an original contribution to an emerging literature that so far has predominantly taken the form of case studies (e.g., Aydin Reference Aydin2021; Aydin-Duzgit Reference Aydin-Düzgit2023; Kutlay and Onis Reference Kutlay and Öniş2021). Building on scholarship on authoritarian endurance and rationalist assumptions about state behavior within International Relations (IR), we argue that authoritarian middle-powers operate in a very different way to their democratic counterparts. Most notably, their drive to ensure regime survival means they seek to foster an international context in which undemocratic politics can thrive. This presents a significant challenge to multilateral norms, standards and institutions, including those related to human rights and democracy. We also show that authoritarian middle-powers often project both hard and soft power in a bid for regime stability and regional ascendance that can destabilize their own regions. The cumulative impact of these trends has the potential to be highly disruptive to global politics, especially if, as projected, the number of authoritarian middle-powers increases in years to come (Cheeseman and Desrosiers Reference Cheeseman and Desrosiers2023). An important corollary of this argument is that these states demonstrate the extent to which domestic conditions shape international behavior, once again reminding us of the complex “entanglement” between domestic and international politics (Putnam Reference Putnam1988).

The Argument

We contend that the survival dilemma faced by authoritarian regimes is more intense than the one faced by politicians in stable democracies: if you lose power, the consequences can be fatal. In the 1960s and 1970s “jail, exile or death” was the “most common outcome for departing leaders in Africa and for more than 30 per cent of leaders in Latin America” (Cheeseman and Klaas Reference Cheeseman and Klass2024: 18). Although the way these considerations play out is likely to vary depending on the type of autocratic or autocratizing state, non-democratic regimes tend to treat retaining power as a zero-sum game in which fewer concessions are made to domestic challengers than in democracies. The policies of such governments are therefore predominantly instrumentalized toward regime survival. Indeed, even foreign aid and peacebuilding, which may be motivated by a number of factors including solidarity and sympathy, are deployed with a view to bolstering the strength of the regime both domestically and internationally. As a result, authoritarian middle-powers’ foreign policy is more self-serving, short-termist, and volatile than their democratic counterparts.

Democracies do not always act benignly or coherently abroad, of course. Democratic states have regularly sacrificed democracy and human rights abroad to pursue their national interest, as the authors themselves have documented (Cheeseman and Desrosiers Reference Cheeseman and Desrosiers2023). This is most clearly the case with democratic great powers, which have frequently used coercion and their economic power to pursue their agenda, including in countries as diverse as Iraq and Nicaragua. The United States has also refused to recognize the jurisdiction of multilateral institutions intended to protect human rights, such as the International Criminal Court, especially under the leadership of Donald Trump. Democratic middle-powers have also acted in self-serving and inconsistent ways, though to a lesser extent because acting aggressively in the international arena comes with greater risk of failure and backlash given their limited economic and military capacity. Over the last five years, for example, countries such as the Netherlands and Denmark have moved to cut foreign aid budgets, while explicitly using aid to leverage progress on key strategic goals such as increasing trade and reducing migration.

Our argument is therefore not that democratic middle-powers never act in illiberal ways. Nor are we arguing that authoritarian middle-powers only act in self-serving or harmful ways: some of their actions may be driven by other considerations such as solidarity, religious beliefs, and humanitarian concerns. This is most clearly the case with regard to the role some have played in supporting peace processes and negotiations, which broadcast soft power but are not solely motivated by this concern. Qatar, for example, has played a pivotal role in attempting to secure the release of hostages, most notably through its long-standing mediation channels with the Taliban. The United Arab Emirates has likewise positioned itself as a diplomatic broker, including by offering itself as a venue for sensitive negotiations that other states are unwilling or unable to host.

Rather, we claim that what is distinctive about authoritarian middle-powers is that, because they are more focused on the short-term imperatives of regime survival and have less need to justify such behavior to national parliaments and citizens, they deploy a wider and more unpredictable arsenal of strategies in response to threats to the regime. Scholars have at times called their behavior abroad “instrumental” or strategic (Aydin-Duzgit Reference Aydin-Düzgit2023), at other times “erratic” (Kutlay and Onis Reference Kutlay and Öniş2021); they have also been described as omnibalancers by some, and as aggressive rule-breakers by others. Making sense of these seeming contradictions requires us to understand the delicate balancing act of regime survival.

One manifestation of authoritarian middle-power foreign policy, for example, is the use of hard power to achieve core goals. This has included collaborating with other governments to assassinate dissidents in exile, arming allies in neighboring countries (both partner governments and warlords serving as proxies), and promoting cross-border disinformation and cybersecurity attacks. In some cases, authoritarian middle-powers have also watered down or ripped up security norms and crossed red lines in their regions, which has made them stability spoilers. The Middle East and the Caucasus, for example, have felt the negative impacts of these kinds of strategies from middle-powers such as Azerbaijan, Iran, and Saudi Arabia.

At the same time, the mid-level military and economic power of such states means that governments are constantly aware of the risks of challenging great powers, and of being isolated by operating outside of multilateral institutions. Consequently, they often remain active in regional and multilateral forums, adopting a strategy of hedging in their international relations. Hedging involves sustaining links to a wide range of possible allies and benefactors in order to blunt threats to the government and promote regime endurance. This typically includes joining a range of overlapping international organizations, networks, and alliances, including those headed by democratic states.

Most states engage in some form of hedging and participate in multilateralism, and authoritarian middle-powers are not alone in adopting more assertive foreign policies. However, their behavior departs in important ways from long-standing assumptions about middle-power conduct. While they draw from the soft power playbook to elevate their international standing, they show a greater willingness to adopt coercive strategies more typical of great powers, particularly when regime survival is at stake.

As this summary suggests, the role of authoritarian middle-powers is both important and multifaceted. In a world in which liberal norms are increasingly being challenged, authoritarian middle-powers are adopting a very different type of global citizenship. Where democratic middle-powers were widely seen to play a stabilizing role, their authoritarian counterparts are disrupting the rules-based international order to boost their own prospects of survival, while actively seeking to undermine the brand power of liberal democracy. In doing so, they have the potential to profoundly change world politics in ways that are not always straightforward. To give just one example, in Eastern Africa and the Horn, the UAE has presented itself as a constructive investor and peace mediator, while also fueling one of the world’s worst conflicts in Sudan through its support of the Rapid Support (RSF) Forces accused of genocide (Mahjoub Reference Mahjoub2024).

As the example of the UAE powerfully demonstrates, the destabilizing effect of these states is not reducible to the tendency of such government to align with other authoritarian powers in the international arena. Authoritarian middle-powers consistently demonstrate their own agency and are neither simply pawns of China and Russia nor making up the numbers in bouts of global power politics within institutions such as the United Nations (UN). Their individual actions may be idiosyncratic, but the sum of authoritarian middle-powers’ actions on the international scene contributes to the unravelling of the rules-based international order.

How We Make Our Case

We evidence this argument by combining case study analysis with a comprehensive and systematic survey of over 250 academic and gray sources on emerging and/or authoritarian and autocratizing middle-powers.Footnote 3 The literature is still nascent and fragmentary and tends to take the form of individual case studies that often use different definitions of middle-powerhood and focus on one specific area of middle-power behavior. Partly as a result, it often comes to contradictory conclusions, with publications focusing on explaining either authoritarian middle-power aggression or hedging, but not the use of both at the same time. We build on this literature to develop a more rigorous definition of authoritarian middle-powers, while revising middle-power theory to develop a new understanding of the core logic driving these states that accounts for both aspects of their apparently contradictory behavior. Our case studies cover some of the most prominent middle-powers, including Türkiye, the United Arab Emirates, and the Like-Minded Group (LMG), which comprises several middle-powers within the United Nations. These paradigmatic cases enable us to illustrate how authoritarian middle-powers operate in specific areas and to demonstrate their impact on world politics.

We present this argument, and structure this Element, in three main parts. The first section addresses the conceptual and theoretical components of our argument. It begins by exploring how middle-powers have been theorized in the classic literature. We briefly revisit these contributions to identify what they can contribute to our understanding of their non-democratic counterparts. We then introduce our own definition of authoritarian middle-powers and our framework for how the logic of authoritarian survival shapes international behavior, including what variations may exist between entrenched authoritarian states and those that only recently started on an autocratizing trajectory. Given that domestic politics fundamentally influence foreign policy, we expect states that are fully autocratic to behave differently than states that are in the process of autocratizing, even if they share a similar logic of political survival. This is especially the case for those regimes facing the greatest political survival dilemma, for example, because they lack full control at home. To illustrate the breadth of the playbook deployed by authoritarian middle-powers, we then explore some of the more prominent strategies they use, grouping them into three core areas of international relations: multilateralism and international relations-building, power projection through foreign policy – both hard and soft – and, finally, nation-branding and the ideas used to legitimate state action.

The remaining sections of the Element address each one of these areas in turn. The second section reveals how non-democratic middle-powers leverage different international institutions and forums to advance their authoritarian aims. In addition to looking at formal international institutions, we pay close attention to the informal relations of authoritarian middle-powers, including to what are increasingly being called “minilaterals.” The section also provides concrete illustrations of authoritarian multilateralism and relations-building by looking at the efforts of the Like-Minded Group to dilute democratic principles within the UN.

Section 3 focuses on how non-democratic middle-powers project power abroad. We demonstrate that hard power such as military intervention is typically deployed alongside specific forms of soft power, including prestige diplomacy and transactional aid. To illustrate this, we look at Turkish foreign policy under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, which has blended coercive involvement in Syria with tough diplomacy, and instrumentalized development cooperation to strengthen the foundations of his regime. The section also explores the aspirations for regional dominance of authoritarian middle-powers – perhaps one of the biggest differences to standard assumptions about their democratic counterparts – which makes them potential spoilers of regional stability.

Section 4 then turns to the type of branding and ideological promotion used by authoritarian middle-powers. IR theory has long recognized the extent to which power and influence is based on perceptions,Footnote 4 and hence can be shaped by nation-branding efforts, communication, public relations, and (dis)information. We show how non-democratic powers use tools such as nation-branding and forms of identity politics in their international relations, drawing on the example of the UAE and Türkiye. The latter is particularly apposite given that its very name – which was changed in 2022 to highlight a nationalist legacy the government hopes to revive – is part of a broader strategy to recast the country’s international image. Through this focus we reveal how the legitimizing efforts of authoritarian middle-powers, while predominantly designed to improve perceptions of the government itself, nonetheless contribute to shifting global norms, promoting the notion of benevolent or palatable dictatorship.

Finally, the conclusion explores what the ascendance of authoritarian middle-powers means for the global order given that the increasingly authoritarian and multipolar nature of world politics is likely to further embolden such states on both the domestic and international stage. It argues that the recent emphasis on China and Russia’s efforts to undermine democratic processes has led researchers, journalists, and policy-makers to overlook the role played by middle-powers. We also argue that it is only when authoritarian middle-powers are considered that one of the key features of the new global order comes into focus, namely that there will be no return to the Cold War. Several recent takes have suggested that the rise of China and Russia means a return to global politics divided between two rival blocs (Abrams Reference Abrams2022). We argue, however, that the competing aspirations of different authoritarian middle-powers, coupled with the fact that they are stability spoilers, suggest that we are unlikely to see the emergence of a stable and unified authoritarian axis. Instead, as recent conflicts and tensions involving Middle Eastern states demonstrate, such as the war in Yemen, the self-preserving nature of authoritarian middle-powers’ foreign policy means that their coalition-building efforts will continue to go hand in hand with competition and instability. The future is likely to be more authoritarian then, but also more uncertain and unstable.

1 Middle-Powers: Why Do We Need a Revised Theory?

The development of scholarship on middle-powers is closely tied to the trajectory of the post-War liberal rules-based order. Some of the earliest references to middle-powers followed the end of the Second World War, when a group of liberal-democratic states supported the development of post-War multilateral institutions in the shadow of the great powers (Chapnick Reference Chapnick2000; Glazebrook Reference Glazebrook1947). Following the end of the Cold War and the purported triumph of liberal democracy (Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama1992), notions of middle-powerhood gained prominence again as several mid-size states began promoting niche global initiatives in support of a reinvigorated multilateralism. During this boom of scholarship, work on states like Canada and Norway strove to illustrate how these democratic middle-powers worked through international cooperation and institutions to promote solutions to global problems.

There was consequently a decidedly democratic focus and Western biasFootnote 5 to research on middle-powers up to the late 1990s. It was only later that work on the notion of “emerging powers” began to redress this imbalance, encouraged by the evolutions in middle-power diplomacy itself, such as the emergence of BRICS (Cooper and Parlar Reference Cooper and Parlar2016; Efstathopoulos Reference Efstathopoulos2021). More recently, there has been a growing emphasis on the number of authoritarian states that are middle-powers in terms of their economic size and military capacity, yet act differently to their democratic counterparts. The early “classic” scholarship nonetheless set the tone in terms of debates around what counts as a middle-power and assumptions regarding how these states behave internationally. It is therefore critical to understand this early scholarship to grasp why it does not account for the behavior of states in the authoritarian sub-group.

This section first reviews the conventional middle-power literature and recent work on their non-democratic counterparts before developing our conceptualization of authoritarian middle-powers and setting out the logic of authoritarian international relations. As well as demonstrating the value of a revised approach that understands countries such as Türkiye, the UAE, and Venezuela as cautious yet self-interested international spoilers, we argue that it is important to differentiate between established autocracies and countries that are autocratizing. First, as governments that are not necessarily fully committed to authoritarian rule, autocratizing states have a particularly strong incentive to maintain alliances with both democratic and authoritarian partners. Second, countries that have only recently begun to move away from democracy may still feature some domestic checks and balances capable of shaping foreign policy decisions, complicating the process of using foreign policy as a tool of regime survival.

Finally, we explain why our discussion is structured around three main types of strategies, setting the scene for the sections that follow. In doing so, we are able to show the range of ways in which authoritarian middle-powers are distinctive, including in terms of their approach to multilateralism and international relations-building, their use of hard and soft power, and the kinds of ideas that are developed to legitimate state action. While these strategies are widely used, their specific deployment – and the ways in which they are combined – is characteristic of authoritarian middle-powers.

Conventional Definitions of the “Middle” and Democratic Middle-Powers

At the heart of conventional theorizing on middle-powers lay one basic operating logic: unable to broadcast global power through military might and economic dominance like great powers, mid-size states adopt a different approach to international relations centered around norms, values, and a principled foreign policy. Such strategies were designed to enhance their global influence and domestic legitimacy, while avoiding treading on the toes of great powers. This made defining exactly what qualifies as “middle”-power status essential, but also a source of debate. Scholars of traditional middle-power theory coalesced around two major traditions with regard to defining the concept: a positional camp focused on states’ ranking in the global power hierarchy, and a behavioralist camp based on how they operate.Footnote 6

For “positional” scholars, middle-powerhood was rooted in how states’ military and economic capabilities ranked in relation to great and small powers (Wohlforth et al. Reference Wohlforth, de Carvalho, Leira and Neuman2018: 527). To establish global power rankings, scholars proposed a variety of measures, from military capability (i.e. prowess), gross domestic product (GDP, wealth) and population (size), to vaguer and harder to assess indicators such as international influence and reputation. Carsten Holbraad’s seminal Middle Powers in International Politics (Reference Holbraad1984), for example, combined gross national product (GNP) and population size with military strength to categorize states. The most popular and agreed upon measures tended to be those seen as more objective, especially GDP. A state’s ranking was then assumed to determine its place and imprint on global politics. From this positional standpoint, middle-powers were presumed to be influential regionally, but to have a limited footprint beyond their immediate neighborhood, at least in comparison to great powers.

The “behavioral” camp instead defined middle-powers on the basis of how states act. This school was especially prominent in traditional middle-power scholarship immediately following the end of the Cold War, which some called a “heyday of normative middle-power diplomacy” (Nagy and Ping Reference Nagy and Ping2023). The behavioralist position rested on the implicit assumption that middle-powers were able to exercise agency and craft their own foreign policy, which they exercise in a similar fashion because they share certain regime characteristics (Efstathopoulos Reference Efstathopoulos2021: 385). Given that the states originally studied in the 1990s were predominantly “wealthy, stable, egalitarian, social democratic” (Jordaan Reference Jordaan2003: 165), middle-powers were understood to espouse a form of moral global citizenship centered on internationalist norms and collaborative values. Thus, in contrast to the positionalists, the behavioral camp defined middle-powers by starting with foreign policy and working backward – with the implication that countries that did not behave in this way would not be considered middle-powers at all, whatever their wealth and strength.

Neither camp managed to fully resolve these debates, or some of their own internal contradictions. The positionalist camp faced challenges regarding which metric best measured middle-power status, while the behavioral camp was seen as tautological, as the key outcome of interest was also the definition used to identify middle-powers. Despite their disagreements, both strands of literature nonetheless agreed on a number of key points. A key one was the importance of linkages between the domestic and international when making sense of middle-power behavior, including how size and more implicitly the democratic makeup of traditional middle-powers matter to their behavior abroad. For conventional middle-power theory, the drivers of international middle-power behavior have therefore tended to be rooted in two main sources: first, the constraints middle-powers face, whether in terms of capacity or in relation to the space they are left by major powers, and second, the belief that promoting certain international collective goods through an avowedly altruistic foreign policy represented a win-win position.

On the one hand, middle-power foreign policy strengthened their domestic legitimacy because citizens favored prestige diplomacy and aid; on the other, it was good for their standing in relation to other countries and the wider international system. These two factors were particularly compelling because they were self-reinforcing. By acting as “good” global citizens, traditional middle-powers could gain a different kind of influence abroad than that afforded to great powers due to their military might and economic influence, as well as domestic legitimacy from the approval of voters. While different scholars have continued to make strong cases for the primacy of each of these drivers (see Cooper Reference Cooper2011), it is important to keep in mind that it is the interaction between the two that made this kind of foreign policy so compelling for states such as Canada: it seemed both rational and beneficial to pursue a seemingly moral or collaborative foreign policy.

This led such countries to take the international “moral high ground” in spaces removed from the realm of realpolitik occupied by more powerful players. Democratic middle-powers became entrepreneurs in terms of internationalist practices to try and punch above their weight (Cooper Reference Cooper2018). Furthermore, because there is strength in numbers, and democratic middle-powers lack the capacity to force change on their own, they have long been theorized to favor working through alliances and coalitions of like-minded states. Given that informal or ad hoc coalitions risk being taken over by larger powers, middle-powers were typically expected to be particularly keen liberal internationalists and supporters of formal and institutionalized patterns of cooperation, championing multilateral arenas such as the UN that have historically afforded them opportunities to “exercise greater global influence” (Cooper Reference Cooper2011: 318, 330). This emphasis on institutions naturally encouraged a focus on the norms and rules needed for such bodies to work effectively. Democratic middle-powers such as Australia, Canada, or Norway were seen as a constructive component of the international political system, promoting principles of democracy and human rights both in multilateral institutions and in other countries.

By investing in global collective goods, democratic middle-powers deployed “soft power” – what Joseph Nye (Reference Nye1990) described as the ability to co-opt and/or persuade other states to adopt a similar approach without using might or force – in comparison to the geostrategic hard power games of greater powers. This was fitting, because democratic middle-powers’ use of soft power stressed their moral authority. Their foreign policy and especially diplomacy have also been described as “niche” and selective (Cooper Reference Cooper1997), as it often centered on specific key global internationalist agendas and initiatives that captured the imagination of democratic elites. Classic examples include international mediation and peacebuilding, the Ottawa Treaty on landmines, and the development of structures to enact international criminal law.

Two major points implicit in the discussion so far are worth bringing out explicitly as they are important for how we understand states’ behavior. First, middle-powers’ behavior has always been understood as a two-level game: their domestic characteristics shape foreign policy and behavior abroad, and vice versa. As Anna Grzywacz and Marcin Florian Gawrycki (Reference Grzywacz and Gawrycki2021) put it, “foreign policy begins at home.” Understanding middle-power behavior therefore requires us to understand states’ domestic political economy, be it liberal-democratic or authoritarian. Second, and relatedly, the bulk of scholarship on classic middle-powers was produced during a liberal epoch and was tied to key internationalist moments of the post-Second World War order. While some scholars have argued that democratic middle-powers can step up to the plate in times of global uncertainty (Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2016; Paris Reference Paris2019), by and large they are seen to have thrived in stable liberal-democratic epochs. This can be seen as an implicit call to recognize how different international contexts foster different patterns of behavior in states. In today’s more authoritarian and multipolar world, a different kind of middle-power is being emboldened.

Developing a more suitable framework for understanding non-democratic middle-powers therefore requires us to take both domestic and international context into account. Emerging scholarship on authoritarian middle-powers is increasingly recognizing this point, while also stressing that traditional middle-power theory cannot fully account for the behavior of states such as now authoritarian Türkiye – one of the most studied non-democratic middle-powers – or autocratizing Mexico. A key theme within this new literature is that authoritarian mid-level states instrumentalize their foreign policy to enhance state stability and regime endurance. In one of the more explicit accounts on authoritarian middle-powers’ behavior, for example, Digdem Soyaltin-Colella and Tolga Demiryol argue that Türkiye’s “activism” abroad is inherently linked to domestic regime survival (Reference Soyaltin-Colella and Demiryol2023). For instance, the regime’s investment in drone development and exports serves both to boost national pride and to enhance border security. In a similar manner, Senem Aydin-Duzgit has shown that Türkiye “picks and chooses” how it engages with the European Union, contesting Europe’s liberal norms most actively when it is seen as a matter of “regime security and to facilitate regime survival” (Reference Aydin-Düzgit2023: 2330, 2321). Türkiye’s engagement abroad therefore serves both to legitimate the government through the “populist dividend” it affords (Kutlay and Onis Reference Kutlay and Öniş2021), and to displace or neutralize the challenge that regional and global norms and agreements could pose to the regime.

This framing reflects wider trends in emergent scholarship, which depicts the authoritarian nature of these states as the main driver of their different or “unusual” approach to foreign policy (Kutlay and Onis Reference Kutlay and Öniş2021). Umut Aydin, for example, argues they are prone to retreating from the kinds of spaces and activities associated with traditional middle-powers (Reference Aydin2021: 1379). Authoritarian middle-powers have also been described as confrontational, aggressive, and as status quo challengers, especially in their region (Jordaan Reference Jordaan2003). Relatedly, a number of scholars have insisted that the distinctive characteristic of authoritarian middle-powers is their use of military force and hard power as opposed to the soft power of their democratic counterparts (Kutlay and Onis Reference Kutlay and Öniş2021; Soyaltin-Colella and Demiryol Reference Soyaltin-Colella and Demiryol2023).

By contrast, a different set of scholars have instead focused on the particularly strong commitment of these states to “nation-branding” activities that are needed precisely to cover-up the regime’s domestic and international abuses (Alderman Reference Alderman2024), as well as efforts to reshape the international environment to make it more favorable to their type of politics (Grzywacz and Gawrycki Reference Grzywacz and Gawrycki2021). Aydin-Duzgit, in particular, has called attention to the importance of ideas, diplomacy and image-management and to the way these states seek to influence global attitudes and perceptions, for example through engagement in multilateral institutions (Aydin-Duzgit Reference Aydin-Düzgit2023).

Put differently, many analysts of authoritarian middle-powers such as Türkiye and Venezuela tend to emphasize either their overtly aggressive foreign policy or their more subtle efforts to undermine liberal international norms through discourse. Both of these “two faces” of authoritarian middle-powers are seen to be driven by their domestic political context (Grzywacz and Gawrycki Reference Grzywacz and Gawrycki2021). The literature on authoritarian middle-powers therefore remains somewhat fragmented. It tends to present these states as either aggressive or cautious, militarized or ideational, with limited explanation of how these different approaches can be made compatible, or how they relate to regime survival.

This has also led to an incomplete understanding of their impact on the liberal international order. While scholars broadly agree that these states challenge the liberal order, they diverge on the nature and extent of that challenge. For some authors, such as Kutlay and Öniş, these states mount a frontal assault on the liberal rules-based order by promoting militarism and unilateralism (Reference Kutlay and Öniş2021). For others, the challenge is more indirect: authoritarian middle-powers subvert liberalism by withdrawing from global activism or questioning the legitimacy of international institutions (Aydin Reference Aydin2021; Aydin-Duzgit Reference Aydin-Düzgit2023; Jordaan Reference Jordaan2003). In order to build on but also go beyond this existing scholarship, we develop a theoretical framework that explains the tendency of authoritarian-middle powers to simultaneously be more aggressive than their democratic counterparts and to hedge and utilize the power of ideas. In turn, this enables us to provide a more coherent account of the way in which they challenge the liberal order, which includes generating greater regional instability and eroding key multilateral standards and agreements at the same time.

Conceptualizing Non-Democratic Middle-Powers

The majority of scholars and global indices suggest the world has become more authoritarian over the last two decades, challenging the international status quo (Bettiza and Lewis Reference Bettiza and Lewis2020). Several democracies believed to be well-established are in the throes of major crises and many authoritarian governments have continued to entrench themselves (BTI 2024a; V-Dem Reference V-Dem.2024). The growing number of authoritarian and autocratizing states requires us to ask what their rise means for international relations. As set out earlier, the emergent scholarship on authoritarian and autocratizing middle-powers views these states as operating on a different logic given their domestic context (Akpinar Reference Akpinar2015; Sandal Reference Sandal2014). Yet, there remains a lack of conceptual clarity and consensus on exactly how they should be defined.

Authoritarian states in this category are also conceived of as secondary powers, i.e. second to the great powers, rather than minor or peripheral, but exactly what this means is not always clear. Umut Aydin proposes that “in terms of capabilities [authoritarian middle-powers] rank between the Great Powers and the small powers that make up the majority of states” (Reference Aydin2021: 1377). While there is consensus that this means that authoritarian middle-powers are often leaders in their region without the capacity to impose themselves globally, there is variation in terms of exactly where the threshold lies between great powers, middle-powers and the rest (Abbondanza and Wilkins Reference Abbondanza and Wilkins2022). One reason the task of defining mid-level status is particularly challenging is that many authoritarian countries in this category have experienced recent changes in terms of their international standing or influence. Nukhet Sandal, for example, speaks of a “new generation” or “second generation of middle-powers” (Reference Sandal2014: 705). Similarly, scholars stress the relatively recent emergence of many of these states on the international scene, using terms such as “emerging” or “rising” (Burton Reference Burton2021; Ongur and Zengin 2017). For her part, Aydin speaks of states “on an upward trajectory in terms of military and economic capabilities” (Reference Aydin2021: 1379–1380). In most cases, there is an agreement that this process began after the end of the Cold War, with a notable surge in recent decades, with the exception of long-standing cases such as Iran.

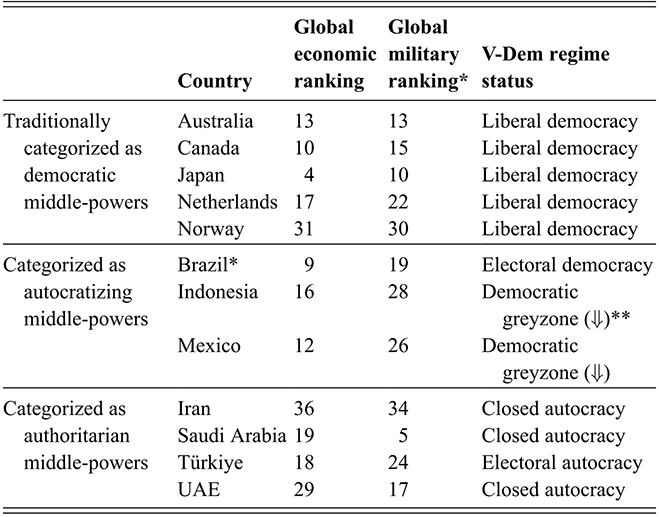

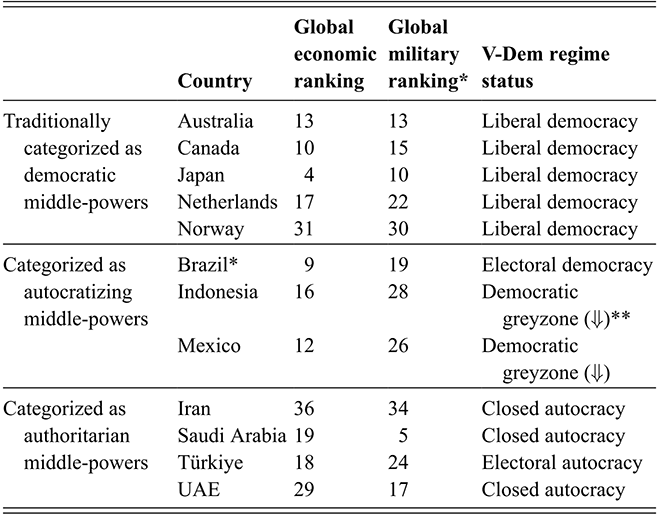

In order to summarize the most commonly referenced cases, and the discrepancies between some of them in terms of size and capacity, Table 1 shows how some of the countries that are regularly named as middle-powers’ rank on the basis of GDP and military spending. For the most part, these middle-powers reside somewhere between the 10th and 50th place globally in terms of their economic power and/or the size of their military sector. There are considerable differences, however, within these categories. Compare Japan, for example, which ranks so highly on GDP it could almost be considered a great power on that score, to states such as Norway and Iran, which have much smaller economies and are closer in many ways to more developed small powers. Similarly, Saudi Arabia ranks 5th in the world when it comes to military spending, whereas Mexico is ranked 29th and spends one seventh as much as a percentage of GDP.

* Calculated based on military expenditures (2022).

** Until the end of the Jair Bolsonaro presidency (31 December 2022).

***Arrows indicate an episode of autocratization between 2013 and 2023. ‘Greyzones’ are “either in the ‘lower bound’ of electoral democracies or in the ‘upper bound’ of electoral autocracies” (V-Dem 2004: 11).

Table 1Long description

Countries are grouped into three categories: traditional democratic, autocratizing, and authoritarian middle-powers. For each case, the table reports global economic and military rankings based on World Bank and SIPRI data, and regime status based on V-Dem’s 2024 classification. Democratic middle-powers include countries such as Australia, Canada, Japan, and Norway. Autocratizing cases include Brazil, Indonesia, and Mexico. Authoritarian middle-powers include countries such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, Türkiye, and the United Arab Emirates.

Table 1 also reveals that there is considerable variation in what scholars use as the threshold for a country to be considered authoritarian. This is partly because defining authoritarianism is challenging. Democracy and autocracy form a spectrum, with various possible combinations, including a “competitive-authoritarian” middle ground (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky2010). The universe of authoritarian states thus features more repressive regimes at one end of the spectrum and more tolerant ones at the other. There is also variation between countries with very different structures of government, including military juntas, monarchic or personalist regimes, and single or dominant party polities (Geddes et al. Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014). While authoritarianism is usually defined as a regime that governs by limiting political alternance, controlling access to state institutions, and infringing on human and especially political rights, scholars differ on what level of abuse is required for a country to fall into the authoritarian category.

A further complication that needs to be considered is that some states are autocratizing, but have not yet become fully authoritarian. As shown in Table 1, for example, Mexico is currently regarded as belonging in the democratic category, though it is also believed to be on a steep downward trajectory. The same was true of Brazil during the presidency of Jair Bolsonaro, and of Indonesia since 2009. These states cannot simply be considered authoritarian, not least because they may never breakdown into full-blown autocracy. Yet, it is important not to ignore this category of country, because if the government has begun undermining democratic institutions and values, it has a vested interest in preventing the enforcement of electoral and human rights standards. At the same time, such cases cannot be expected to behave in exactly the same way as authoritarian states, because they may still feature some influential checks and balances.

One final feature of nondemocratic middle-powers that is often referenced by scholars but not included in formal definitions is that most come from what is often called the “Global South.” Eschewing debates about what counts as the Global South (is Türkiye Southern? Is Kazakhstan?), authoritarian middle-powers are generally defined as “Southern,” “developing,” and/or “peripheral” in terms the center–periphery distinction found in dependency theory (Aydin-Duzgit Reference Aydin-Düzgit2023; Soyaltin-Colella and Demiryol Reference Soyaltin-Colella and Demiryol2023). Charalampos Efstathopoulos, in particular, argues that the actions of these states should be interpreted primarily through a Southern lens, rather than one that emphasizes their emerging status because their rise to prominence may not be as linear or straightforward as the notion of emergence implies (Reference Efstathopoulos2021: 388).

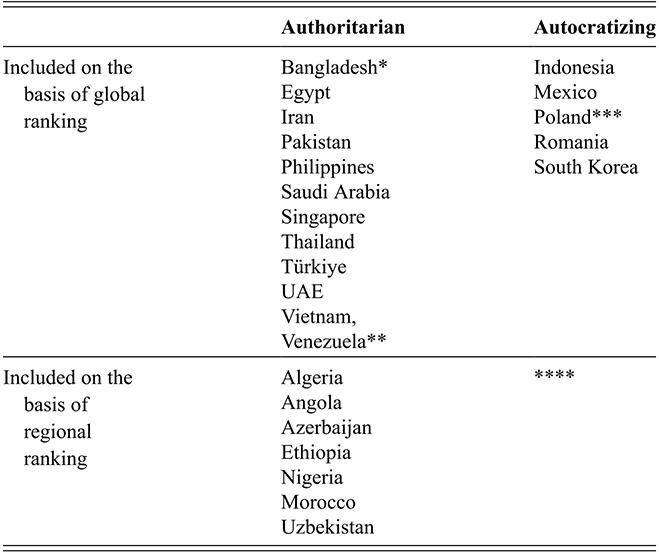

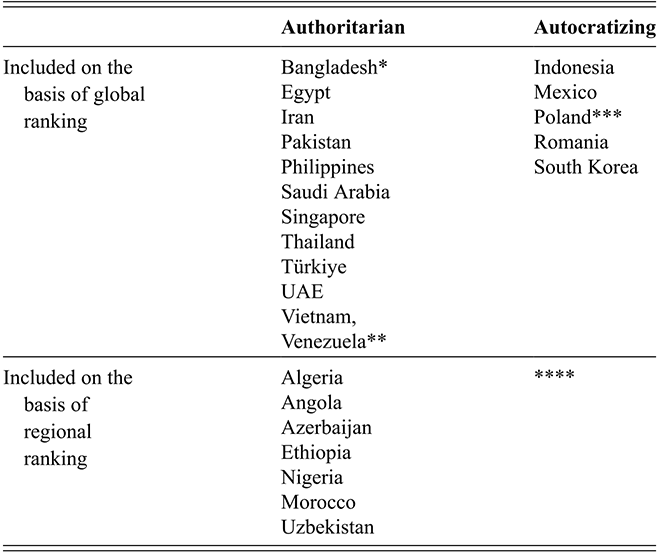

Building on these insights but seeking to deliver greater clarity in terms of middle-powerhood criteria, we define authoritarian and autocratizing middle-powers as states that are regional leaders but unable to exert dominance globally. In order to be consistent and avoid conceptual stretching, we only count a state to be a middle-power if it ranks lower than 10th and higher than 50th globally on both military and economic capacity, or does not meet this criterion but ranks in the top two countries in its own region in terms of both military and economic capacity.Footnote 7 We include this latter consideration because although these countries have a weaker claim to be considered second-level powers, and are less able to influence global events, a key feature of middle-powers is that they are locally powerful without being globally dominant. The majority of our discussion focuses on states that qualify as middle-powers in terms of their global ranking, such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, Türkiye, and the UAE, and which have the strongest claim to middle-power status (see Table 2). Also drawing examples from middle-powers included on the basis of our “regional leader” criterion, however, enables us to demonstrate the impact these countries have on regional international relations, and the extent to which they exhibit similar patterns of behavior to more established middle-powers on the world stage.

* Prior to the recent political transition and the fall of Sheikh Hasina.

** The figures on military spending in Venezuela are contested and impacted by sanctions – see online appendix for more details.

*** Prior to the election of Donald Tusk’s government in 2023.

**** There are no countries in this category – all of the states that would be considered middle-powers on the basis of the regional consideration also meet the global criterion.

Table 2Long description

The table distinguishes between fully authoritarian cases and countries undergoing autocratization. The authoritarian column includes cases such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, Türkiye, Vietnam, and Venezuela, as well as several others identified through the global criterion, and additional cases such as Algeria, Nigeria, and Uzbekistan identified through the regional criterion. The autocratizing column includes Indonesia, Mexico, Poland, Romania, and South Korea, all of which meet the global ranking criterion. A note indicates that no autocratizing middle-powers are identified on the basis of the regional criterion, as all cases that would fall in this category are captured by the global criterion.

As our argument only covers non-democratic states, we also need clear criteria to identify authoritarian and autocratizing countries. We consider a country as authoritarian if it has been classified as an autocracy by V-Dem as of 2023.Footnote 8 We consider a state to be autocratizing if it is not already classified as an autocracy, but experienced an autocratizing episode according to the V-Dem ERT database in the last decade (2013–2023). This generates a universe of authoritarian middle-powers that includes Iran and Türkiye, and a universe of autocratizing middle-powers that includes Indonesia and Mexico. (See Table 2; also see online appendix for a categorization of all countries.)

While it is true that authoritarian middle-powers tend to be more Southern than their democratic counterparts, and are often seen as emergent, we nonetheless have chosen not to make this a feature of our definition for two reasons. First, there are clear exceptions to this tendency, such as Türkiye, and so it is misleading. Second, it is unclear that the fact that states are Southern means they share sufficient commonalities for this to be a useful distinction, or to develop a revised understanding of their behavior – which is the aim of the next section.

Theorizing the Logic of Authoritarian International Relations

The characterizations of authoritarian middle-powers set out in the recent literature – as both aggressive and withdrawn, instrumental and erratic – stand in stark contrast to long-standing definitions of democratic middle-powers. Understanding authoritarian middle-power behavior therefore requires us to rethink and reinvent middle-power theory for the contemporary world. While state size continues to shape what is possible for these states, their non-democratic character means that regime survival – not just state survival – takes precedence. International relations and foreign policy, whether expressed through hard or soft power, therefore becomes a flexible tool in service of that goal. Put differently, authoritarian middle-powers use international engagement not only to secure the state but to preserve the ruling elites who control it.

In one of the clearest statements on the mechanisms at play behind non-democratic international relations, Christina Cottiero and Stephan Haggard argue that: “autocrats desire foremost to remain in power, and this motivates their interests in limiting democratic contagion from abroad and political challenges at home” (Reference Cottiero and Haggard2023: 3). This speaks to core assumptions regarding the rationality of states in the conduct of their foreign policy in classic International Relations scholarship and suggests a rationale of international behavior that also echoes scholarship on the logic of political survival developed in comparative studies of authoritarian politics. Yet with a few notable exceptions,Footnote 9 these two bodies of work have rarely been integrated to explain state behavior, despite sharing a similar focus on the instrumental behavior of governments. We draw on both to explain the drivers of non-democratic middle-powers’ international relations.

Comparative politics scholars often take political endurance or survival to be the main driver of politics, whether in democratic states or authoritarian ones. Most researchers explicitly or implicitly assume political leaders are driven by power, that is, to attain it and retain it (de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno De Mesquita, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2005: 19; Svolik Reference Svolik2012). Notwithstanding major debates regarding the rationality of politics (Jervis Reference Jervis1976; Nardin Reference Nardin2015), it is therefore common to assume that the game of politics is played instrumentally. Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and colleagues’ now seminal selectorate theory is a prime example of scholarship that theorizes this logic of political survival (de Mesquita and Smith Reference de Mesquita, Bruce and Smith2011), stressing that there are common rules of the political game that apply across the spectrum of polities and that center on ensuring regime endurance. Autocrats may have some advantages here. Authoritarians depend on a much smaller group of individuals to make it to power and remain in power. Thus, while autocrats never rule alone, the number of constituencies they must cater to and their “minimum winning coalition” is much smaller than for democrats.

Yet authoritarian leaders also play for higher stakes. Although politics is a long-term multi-iteration game, authoritarian governments cannot assume that they will have an opportunity to regain power in the future if they lose it in the present. Autocrats often persecute and prosecute their rivals and may also assassinate them or send them into exile (Cheeseman and Klass Reference Cheeseman and Klass2024). This ensures that the survival dilemma autocratic leaders face is an intense one. It also makes questions of how to win the support of key constituencies a survival imperative (Cheeseman and Fisher Reference Cheeseman and Fisher2019), even when elections are not held. The zero-sum nature of authoritarian politics is what motivates the strategizing of leaders to incentivize support, disincentivize defections, and reduce dissent more broadly (Gerschewski Reference Gerschewski2023).

The higher stakes involved in repressive regimes means that the authoritarian political game is also likely to be played using a wider range of strategies to ensure power is not lost. This tendency is reinforced by a context where regimes not only have the means to bend the rules but face fewer barriers and punishments to doing so. This means that strategies such as violent repression, identity or personalist politics, and corruption are common. Despite this, however, repression and cooptation are rarely sufficient on their own, not least because these strategies can be immensely costly both financially and to a leader’s reputation (Cheeseman et al. Reference Cheeseman, Fisher, Mwambari and Wolfe2025). Scholars such as Johannes Gerschewski (Reference Gerschewski2023) have stressed how autocrats are keenly aware of the need to persuade larger segments of society to avoid making them into potential challengers. They therefore use legitimization strategies, such as showcasing their ideology, claiming performance or banking on charismatic or traditional sources of legitimacy, to contribute to their political survival. Persuasion is a fundamental strategy of authoritarianism.

This set of assumptions within political science echoes a standard practice in International Relations. There is a long tradition in IR literature of treating decision-makers – or the state itself as the aggregate of government decision-making – as rational actors who deploy foreign relations in instrumental ways.Footnote 10 It is true that there has been a vibrant debate about how deep rationality runs, from proponents of rationality as a fundamental assumption to those who qualify absolute rationality assumptions and stress the impact of imperfect information or emotions, for example (David Reference David2023; Yarhi-Milo Reference Yarhi-Milo2023). Yet dominant IR theories and especially realism, neorealism, neoliberalism, and their variants all consider that states act rationally internationally to gain or preserve power, weight, and influence, or to basically survive in a highly competitive international environment. Put differently, the drive behind foreign policy is to ensure the state does not falter, whether it be democratic or authoritarian.

The major difference between how democracies and non-democratic regimes operate abroad therefore lies not in their core goal but in how they process decisions and how they understand what will best enable them to attain this goal. Rational behavior is not determined by the inherent rationality of a particular course of action in itself (alliances, cooperation, war, for example), but by the decision-making process that leads to the type of foreign policy or international approach adopted. These deliberations are grounded in “credible theories” or what could be considered the logic of a decision. In other words, states hold “credible theories about the workings of the international system and use them to understand their situation and determine how best to navigate it” (Mearsheimer and Rosato Reference Mearsheimer and Rosato2024).

We draw on these two bodies of literature to build our theory of authoritarian middle-power international relations. Those who deliberate and design foreign policy are state decision-makers. As Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith put it, “[s]tates don’t have interests. People do” (Reference de Mesquita, Bruce and Smith2011: 25). The preeminent driving logic for autocratic leaders is their political survival, and how international relations can be put in the “service of the prince.” While authoritarian middle-powers lack the influence of greater powers, they have enough to use international relations as a potent tool of regime survival. This includes pre-empting potential challenges to the regime, diverting attention away from embarrassing aspects of domestic politics, and building coalitions that support power retention.

International relations can impact a regime’s ability to endure in direct and indirect ways. Directly, foreign states can provide support such as trade, resources, technological assistance, and military hardware that can be used to repress domestic opponents. Forming alliances with powerful states can also help to insulate an autocratic regime from international interventions to (re)establish democratic rule, such as sanctions and support to pro-democracy leaders. Indirectly, achievements on the international stage can be used to legitimize a government back home. Manifestations of prestige and influence abroad, or recognition by other states of a country’s prestige or legitimacy, can impact on how it is perceived domestically, making it easier to retain power.

Türkiye under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan offers a compelling example of how authoritarian middle-powers instrumentalize international relations and foreign policy. Following a period of autocratization beginning in the mid-2000s, Türkiye is now widely considered authoritarian. Over the past decade, its international posture has grown markedly more assertive, including military interventions in the Syrian civil war targeting the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Simultaneously, Türkiye has expanded its role as a diplomat and donor, particularly to Muslim-majority countries – moves that have bolstered Erdogan’s domestic image as a powerful global actor. For example, Türkiye is now ranked third in the world in terms of its number of diplomatic missions, surpassed only by China and the United States (Kutlay Reference Kutlay2025).Footnote 11 This international activism has supported Erdogan’s promotion of Turkish nationalism and the vision of Türkiye as a “great nation, and great power” (Fradkin and Libby Reference Fradkin and Libby2013), a narrative also reinforced through popular cultural products like the nationalist, neo-Ottoman TV series Diriliş: Ertuğrul, which glorifies the country’s imperial past. Erdogan also cultivated strategic ties abroad, including with President Donald Trump, securing US support for the flawed 2017 constitutional referendum and 2018 presidential elections. This undermined the credibility of international election observers and helped deflect democratic criticism. In this way, Erdogan’s leadership epitomizes the use of more assertive foreign policy strategies to enhance a leader’s legitimacy, promote pro-regime narratives, and insulate the government from external democratic pressures.

At the same time, however, the leaders of authoritarian middle-powers are aware of the dangers of being perceived to be a threat to global powers, and the heightened risks involved with operating independently of multilateral institutions. Consequently, they often remain active participants in regional and multilateral forums that offer a degree of protection. Similarly, these states frequently hedge by joining multiple overlapping international networks and alliances, including those led by democratic nations. This hedging sometimes goes hand in hand with the use of more coercive forms of foreign policy, especially with regard to smaller and middle-powers in their region. Driven by the imperative of survival, some authoritarian middle-powers have not hesitated to employ the full range of strategies at their disposal, including military support for allies in neighboring areas or efforts to establish regional dominance, which bolsters their influence over regional politics and, by extension, enhances their chances of survival. Their behavior abroad therefore often blends hard power with the more traditional soft power tools commonly associated with democratic middle-powers, mixing strategies of regional ascendance with prestige diplomacy, foreign aid designed to strengthen international alliances, and/or nation-branding.

The pre-eminence of political survival is also key to understanding the different strategies adopted by autocratizing middle-powers. Autocratizing states, while moving toward more exclusionary forms of governance, are nonetheless likely to be more constrained by checks and balances institutions, civil society and public opinion, than their authoritarian counterparts. Put another way, they are likely to cater to a larger winning coalition, and to face greater constraints on domestic and international rule-breaking. Judiciaries, for example, have in some cases proved able to serve as a break on autocratization, even in cases of pronounced democratic backsliding. As a result, autocratizing middle-powers are likely to be more cautious in their choice of approach, both domestically and internationally.

We expect this to manifest as more expansive hedging – that is, as we explain below, catering to a more diverse set of international allies, and participating in a wide range of international arenas. Autocratizing middle-powers are also more likely to be more restrained in using international strategies that cross red lines, unless faced with a domestic crisis. In keeping with this distinction, the type of ideological and legitimation registers used by autocratizing states is likely to differ from fully authoritarian regimes. In their extensive survey of non-democratic governments’ legitimation strategies, Christian Von Soest and Julia Grauvogel (Reference Soest, Christian and Grauvogel2017) suggest that autocratizing regimes tend to focus their ideological work on stressing their relations to society, while closed authoritarian states work on ideas that promote forms of identity and solidarity geared toward the regime (personalism or a foundational myth, for example). Autocratizing middle-powers are therefore likely to manifest a form of behavior that lies between democratic and authoritarian middle-powers. At the same time, the fact that they are moving at different speeds toward authoritarianism and experiencing significant changes in regime type means that their strategies may be more unpredictable and that there is likely to be greater variations in approaches among the countries in this category.

As this discussion makes clear, we do not claim that the individual strategies authoritarian middle-powers deploy are all unique. Most states hedge, cultivate alliances, and invest in their international image. Nor are authoritarian regimes alone in adopting assertive or aggressive strategies. What sets them apart, however, is the arsenal of strategies they use simultaneously, and how they combine them to serve regime survival. When compared to their democratic counterparts, authoritarian middle-powers are more likely to use hard power when confronting threats. In addition to departing from the good citizenship described in classic middle-power literature, this behavior also challenges the status quo, crosses red lines, and defies established norms when regime security is at stake. These moves are not accidental but calibrated – harsh where needed, restrained where strategic – to ensure both survival and international maneuverability. In line with this calibrated approach, these states also offset this more aggressive strategy with softer tools, because they need to use regional diplomacy, multilateral engagement, and charm offensives to a greater extent than authoritarian superpowers.

As with their domestic policies, the international relations of authoritarian middle-powers are therefore pragmatic, self-serving and “transactional” (Kutlay Reference Kutlay2025). This often results in edgier behavior than is typically expected from middle-powers: bending or breaking international rules, when necessary, with potentially greater harm to regional peace and stability than their democratic counterparts. Their behavior is also more volatile. These regimes enjoy more domestic leeway to shift foreign policy in response to emerging challenges, yet balance assertiveness with other strategies. What some have termed the “erratic” nature of undemocratic middle-powers is in fact a structural function of both their domestic politics and level of power. The efforts of these states to weaken liberal global norms are often bold, especially in their neighborhoods, but only where they can afford to be.

A final important consideration is that foreign policy is shaped not only by regime type but also by the international context. Authoritarian middle-powers are more likely to deploy their full strategic arsenal in international environments that are more facilitative of non-democratic approaches. This is the case today, when the emergence of an increasingly authoritarian global landscape and growing multipolarity have emboldened leaders to pursue illiberal strategies at home and abroad. But our current illiberal epoch is not unique in this sense. The interwar period similarly saw a surge in authoritarianism, empowering illiberal middle-powers like Germany and Italy – with disastrous consequences for global stability. These parallels underscore that middle-power behavior is not fixed. It evolves with shifts in the global balance of power and the normative environment, making it essential to analyze such actors within their broader geopolitical moment. It is in the present context, in which the costs and risks associated with undemocratic behavior have become lower and continue to fall, that authoritarian middle-powers are most likely to engage in behaviors that align with the efforts of leading anti-democratic states such as China and Russia to undermine the liberal world order.

Again, this does not mean that imply that all behavior by authoritarian middle-powers is self-centered, or that they do not act at times in order to promote the greater good, but rather that based on these theoretical foundations we expect these short-term domestic considerations to be a particularly powerful determinant of foreign policy. Moreover, our goal is not to show that the global strategies adopted by authoritarian middle-powers are always effective at ensuring regimes endure, but instead to demonstrate how domestic considerations shape international strategies and to highlight some of their consequences. The trajectory and fate of regimes often diverge from what their leaders expect, and the best laid plans can go awry. The main focus of this Element is therefore not authoritarian survival, but rather to explain how the quest for survival shapes foreign policy, and how the cumulative impact of such strategies has helped create a more inhospitable international environment for the promotion of democratic norms and for the liberal rules-based order.

The Authoritarian Middle-Power Toolkit

We outline the broad contours of the authoritarian middle-power “toolkit” (Schatz Reference Schatz2009) in Table 3 which summarises the key differences set out above between democratic and non-democratic middle-powers. In doing so, we categorize the strategies deployed by middle-powers into three heuristically distinct but by no means unconnected categories: multilateralism and relations-building, power projection and foreign policy, and nation-branding and the ideas and ideologies used to foster legitimacy abroad. These categories have been selected because they echo some of the key characteristics of traditional middle-power behavior – supporting multilateralism, their distinctive use of soft power, the way they promote democratic norms – while enabling us to illustrate how non-democratic states diverge from their democratic counterparts.

* These strategies do not imply that traditional middle-powers necessarily behave for purely altruistic reasons.

Table 3Long description

The table contrasts democratic strategies, such as liberal alliances, soft power, and liberal internationalism, with authoritarian ones, such as authoritarian multilateralism, hard power, transactional aid, alternative ideologies, and identity-based solidarity.

These categories also capture three of the core components of international politics: relations between international actors, power (i.e. the ability to influence or persuade others), and legitimizing ideas and ideologies, which emerging work on authoritarian middle-powers has stressed is key to their international relations (Aydin-Duzgit Reference Aydin-Düzgit2023; Kutlay and Onis Reference Kutlay and Öniş2021). Multilateralism and relations-building specifically focus on the type of relations middle-powers seek out and support, from engaging in collective forums to the more informal networks they may work through. Power projection speaks to the means deployed by states to try and shape the behavior of others toward them, including in some of its hard forms, as well as some of its softer ones. Finally, as is now widely recognized in International Relations theory, ideas, from ideologies to identities, also matter in terms of how states behave, and how actors behave towards them. This category of strategies therefore centers on the types of notions states promote of themselves, generally in the form of branding or their international identity.

In the following sections we provide empirical evidence to support the characterization set out in Table 3 and explore the different combinations of strategies that states deploy. For each type of strategy, we also assess the impacts of authoritarian middle-powers on regional and global political dynamics. Some of these effects are relatively direct and observable – for instance, enhanced regional coordination in the repression of political opposition, or the destabilization caused by interventionist behavior in neighboring states. Other forms of influence, however, are more diffuse and difficult to quantify. In particular, the sustained promotion of authoritarian alternatives to liberal democracy, or the deployment of nation-branding strategies by repressive regimes to render their models more palatable, generate subtler yet significant normative shifts.

As longstanding debates in International Relations suggest, the ideational, discursive, and normative dimensions of international influence are notoriously challenging to measure. We acknowledge this analytical limitation while nonetheless using a range of sources, including survey data, media coverage, and scholarly literature, that demonstrates the direct and indirect effects of these efforts. One illustrative trend, for example, is the documented decline in references to “democracy” in multilateral spaces. As Jennie Barker demonstrates (2024), the growing tendency to erase “democracy” is a direct consequence of the efforts of authoritarian middle- and great powers to dilute established norms of democratic governance and human rights in key forums such as the United Nations. Importantly, these developments are not merely rhetorical. As we show throughout the Element, by eroding the liberal normative foundations upon which much of the post-War international order rests, authoritarian states aim to render international intervention to assert and defend liberal principles less likely. In turn, this challenges core IR assumptions that view undemocratic states as unlikely to engage in multilateral environments – and necessitates a deeper look at the foreign policy of authoritarian middle-powers.

2 Multilateralism and International Relations-Building

Democratic middle-powers have long been cast as staunch supporters of multilateralism, particularly liberal international institutions. In the context of a more liberal internationalist era, scholars such as Edward Mansfield and Jon Pevehouse argued that multilateralism served as a conduit for democratic norms and even democratic change (Mansfield and Pevehouse Reference Mansfield and Pevehouse2006; Pevehouse Reference Pevehouse2005). Conversely, it has often been argued that authoritarian powers tend to be isolationist and are much less likely to focus on multilateral arenas and alliance formation (Aydin Reference Aydin2021). As the previous section has demonstrated, these assumptions about authoritarian middle-powers are dangerously wrong. Authoritarian and autocratizing middle-powers have neither rejected nor disengaged from multilateralism. Instead, they regularly engage international institutions to advance regime interests.

At the global level, including within the UN, authoritarian middle-powers have worked to dilute liberal norms, while using regional organizations – both longstanding and newly formed – to promote authoritarian counter-norms and practices (Cooley Reference Cooley2015: 49). In this sense, they appear to uphold the multilateral status quo through formal engagement, while simultaneously subverting it from within. Beyond formal institutions, they also operate through informal mechanisms, such as minilaterals and ad hoc coalitions with like-minded states. Autocratizing regimes often mirror these patterns, though they tend to be more ambivalent toward weakening multilateral structures, especially in the early phases of democratic erosion.

This section begins by examining how authoritarian middle-powers engage multilaterally, before turning to their international alliances, networks, and finally the transnational relationships they leverage to support long-term regime survival. Evidence from case studies such as the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC), along with data on the rise of authoritarian regional organizations, reveals how non-democratic middle-powers use these arenas to erode democratic norms and construct spaces of authoritarian coordination and solidarity. While some of these initiatives have been led by global authoritarian powers – particularly China and Russia – we show that middle-powers often pursue such strategies independently, sometimes advancing authoritarian alternatives without direction or encouragement from more powerful allies.

International Organizations

International organizations have long been viewed as central pillars of the post-Second World War liberal order, enabling Western states to promote democratic values and collective security. As regularized forums for cooperation and norm-setting, institutions such as the UN, the European Union, and various regional bodies have been seen by liberal theorists as foundational to global stability and collaboration (Ruggie Reference Ruggie1992). Yet these same organizations – most notably the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) – have become arenas of contestation, where authoritarian states promote counter-norms that align more closely with their regimes. This includes advancing principles such as sovereignty and non-intervention, limiting scrutiny of authoritarian practices, and denying support to pro-democracy actors.

While China has often led these efforts, it has not acted alone. Authoritarian middle-powers – including Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela – have played key roles in reshaping multilateral spaces to favor non-democratic norms (Inboden Reference Inboden2019). Within the UNHRC, for example, they have backed China’s push to redefine human rights in developmental terms, emphasizing the right to development over political freedoms (Ginsburg Reference Ginsburg2020; Piccone Reference Piccone2018: 4). In some instances, this norm revisionism has also extended to promoting conservative, “traditional” values with adverse consequences for women’s and LGBTQI+ rights (Cooley Reference Cooley2015: 50–53).

Along with China and Russia, middle-powers have also argued for understanding multilateralism through the lens of civilizational diversity and global equity. This includes the speech by President Maduro of Venezuela at the UN General Assembly arguing for a new world that ends “old hegemonies, to put an end to the pretense of some to become policemen and judges of all the peoples of the world,”Footnote 12 and President Erdogan’s demand to make the world “bigger than five” in reference to the Security Council.Footnote 13 These efforts at changing some of the classic liberal underpinnings of the UN have also gone hand in hand with attempts – not always successful – to change practices associated with the defense of democratic and liberal norms. This has predominantly focused on minimizing criticism leveled at specific authoritarian or autocratizing states for their human rights record within multilateral institutions and constraining the participation of democracy and human rights allies such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in such forums.