Since the discovery of the psychoactive effects of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) in 1943, Reference Hofmann1 a complex relationship has existed between researchers studying psychedelic drugs and the popular media. Early media coverage of psychedelic drugs in the mid-20th century often treated these drugs with openness and curiosity, with first-person accounts of drug experiences and interviews with intellectuals or celebrities included as subject matter. Once LSD became more widely used in recreational settings, media coverage trended towards greater emphasis on adverse effects and sensationalistic negative themes, such as unproven claims that LSD causes chromosomal damage and birth defects. Reference Siff2 Commentators at the time expressed concern about the deleterious effects of both unduly positive and negative media coverage on the progress of research into therapeutic applications of LSD. Reference Grinker3,Reference Rosenfeld4 In the wake of increasing negative publicity and opposition from the US federal government, support for scientific research gradually declined before ceasing entirely. Reference Oram5

US research into psychedelic drugs began again in the 1990s, with interest in their therapeutic potential increasing dramatically over the past two decades. Reference Fonzo, Wolfgang, Barksdale, Krystal, Carpenter and Kraguljac6–Reference Bender and Hellerstein8 Four commercial entities studying classical psychedelics have received U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) breakthrough therapy designations, 9–12 billions of dollars have been invested into companies studying classical psychedelic drugs or novel chemical analogues, 13 four states have legalised the use of psychedelic drugs within specific settings 14 and US federal government agencies have begun funding research into the potential therapeutic applications of psychedelics. 15 General popular interest has increased simultaneously, Reference Danias and Appel16 with the term ‘The Pollan Effect’ coined to describe the impact of positive media coverage of psychedelics on public perception. Reference Noorani17,Reference Pollan18

In 2022, several researchers characterised this broad surge in interest as a ‘psychedelic hype bubble’ driven by media and commercial interests, expressing concern that this perceived excess in positive sentiment could negatively impact scientific research. Reference Yaden, Potash and Griffiths19 Media outlets are incentivised to attract collective attention, Reference Hayes20 which may contribute to imbalanced discussions of the risks or benefits of psychedelic drugs. This in turn may promote extremes of opinion regarding their appropriate usage and processes of implementation. Reference Siff2

Various commentators consider the year 2024 to be a negative period for the advancement of the clinical application of psychedelic drugs, Reference Hardman21,Reference Khazan22 which included the rejection of the FDA application for the use of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted therapy (MDMA-AT) in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Over the course of that year, several articles were published in major media outlets highlighting various criticisms of the perceived quality of psychedelic research, Reference Khazan22–Reference Silman25 with other commentators suggesting that the rejection of MDMA-AT had resulted from bias. Reference Nuwer26–Reference Xenakis28 Within this evolving media landscape, understanding the relationships between media portrayal of psychedelics, the results of scientific research and political decision-making is especially important.

To our knowledge, two peer-reviewed publications have examined trends in media portrayal of psychedelic drugs in the 21st century, identifying various trends including increasing coverage and increasingly positive sentiment for certain media outlets. Reference Bouzoubaa, Ehsani, Chatterjee and Rezapour29,Reference Oliver30 These studies have been limited to analysis of up to four newspapers and have not applied modern large language models (LLMs) to perform sentiment analysis at scale. This study employs ChatGPT to quantify trends in media portrayal of the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs during the 21st century.

Method

Data collection

Searches for the term ‘psychedelics’ at news.google.com were conducted within private browser windows between January and March 2025 for each calendar year 2000–2025. Every URL derived from each search was extracted (up to 300 per year) and screened by human raters, who determined whether the web page met broad inclusion criteria for constituting an analysable online media article, which included the following: having a date of publication, having adequate text to analyse, not being solely an advertisement, not being published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal and having a functioning URL link (Supplementary Materials, Appendix A available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10974). If human raters were unsure whether a URL met inclusion criteria, that URL was referred to the first author for evaluation. We included articles from a broad variety of online media websites (e.g. major media outlets, academic news media, specialist medical media websites, advocacy websites) to minimise sampling bias. Included URLs were analysed by ChatGPT to determine whether their content focused on the therapeutic potential of psychedelics and, if so, to assign a sentiment score (range 1–100) regarding how positive the article is about the therapeutic potential of psychedelics (Supplementary Methods). A ChatGPT-4-based model was the default during the period of data collection. Total numbers of URLs for each year were determined by summing totals for Google searches confined to calendar years (Supplementary Methods).

Human versus artificial intelligence comparisons

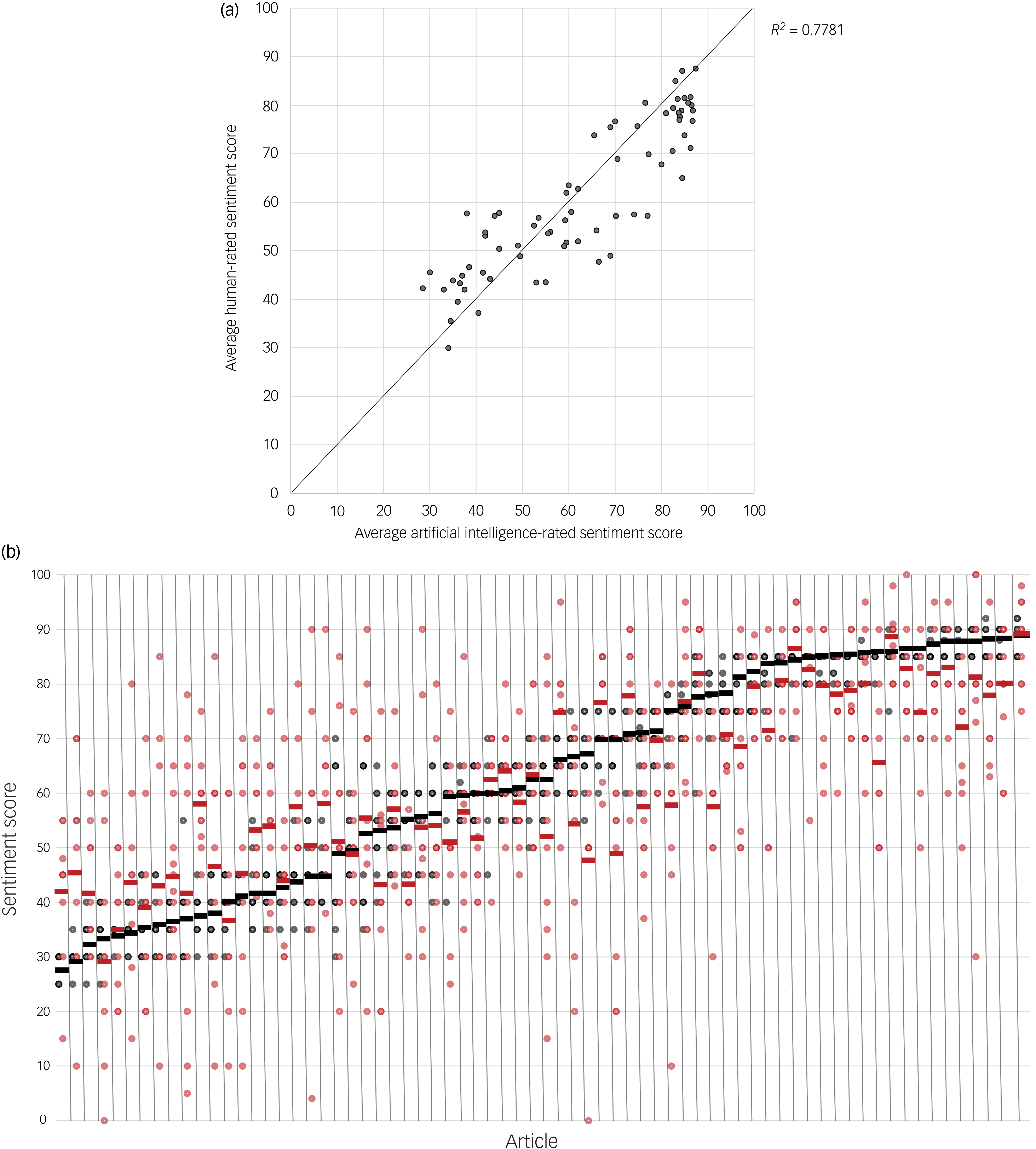

A random number-generator (Matlab 2024b, Mathworks) was used for random selection of approximately equal numbers of URLs from three tiers of articles distinguished by artificial intelligence-determined sentiment score (0–49, 50–74, 75–100), with 70 articles in total selected. These URLs were divided into 3 groups with approximately equal representation of sentiment score tiers, which were assigned to 3 subgroups of human raters (9–10 raters per group; Supplementary Materials, Appendix B). Human raters had varying educational levels (at minimum, high school graduate), and prior knowledge about psychedelic drugs was not a selection criterion. Each human rater was asked to independently score the sentiment of the articles provided using the identical prompt offered to the artificial intelligence (Supplementary Materials, Appendix C). Corresponding artificial intelligence scores for assigned articles were not provided to human raters. For each article scored by human raters, ten total repetitions of the data collection procedures (Supplementary Methods) were performed to collect ten artificial intelligence sentiment scores. Collected human rater and artificial intelligence sentiment scores were averaged for each article for the data-set shown in Fig. 1(a).

Fig. 1 Comparison of the performance of artificial intelligence and human raters in measuring media sentiment towards psychedelic drugs. (a) Scatter plot comparing the average artificial intelligence sentiment score for 70 randomly sampled articles with the average sentiment score of human raters (9–10 raters per article). The plotted line represents the theoretical line of complete concordance between artificial intelligence and human ratings. (b) Plots of each individual sentiment score rating for human raters and repeated artificial intelligence iterations for all 70 articles. Each column on the x axis represents an individual article, with articles sorted left to right from lowest to highest average artificial intelligence rating. Black points denote individual artificial intelligence ratings and red points denote individual human ratings. The thickness of borders for individual points represents the number of ratings at a specific sentiment score, with thicker borders indicating more ratings at that score. Black and red bars represent average scores for artificial intelligence and human raters, respectively.

A random number-generator was used to select 15 articles from Google News judged by artificial intelligence to focus on the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs, and 15 articles that artificial intelligence had judged as not focusing on the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs. Human raters were asked to give a yes or no answer to the identical prompt provided to the artificial intelligence for these 30 articles (see Data collection). Human raters were not provided with the answer previously offered by the artificial intelligence. Articles were considered to have ambiguous content if the percentage of human raters answering the majority response consisted of between >50 and ≤70% of the rater population, or if equal numbers of human raters answered yes and no. For a given article, if no human majority occurred due to equal numbers of human raters answering yes and no (n = 1), artificial intelligence was by default assigned as agreeing with the majority of human raters.

Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney U-test conducted in Matlab 2024b was used to compare sentiment score averages between different subpopulations of scores (sentiment in 2020–2023 versus 2024; human versus artificial intelligence sentiment scores).

Interrater reliability was calculated for subgroups of articles rated by the same group of human raters using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) 2,k, Reference Koo and Li31 with computations performed in Microsoft Excel. ICC was calculated for each article subgroup for both human raters and artificial intelligence scores derived from ten scoring iterations.

The concordance correlation coefficient between averages of artificial intelligence and human scores for individual sampled articles was calculated in accordance with established procedures, Reference Lin32 with computations performed in Microsoft Excel.

Results

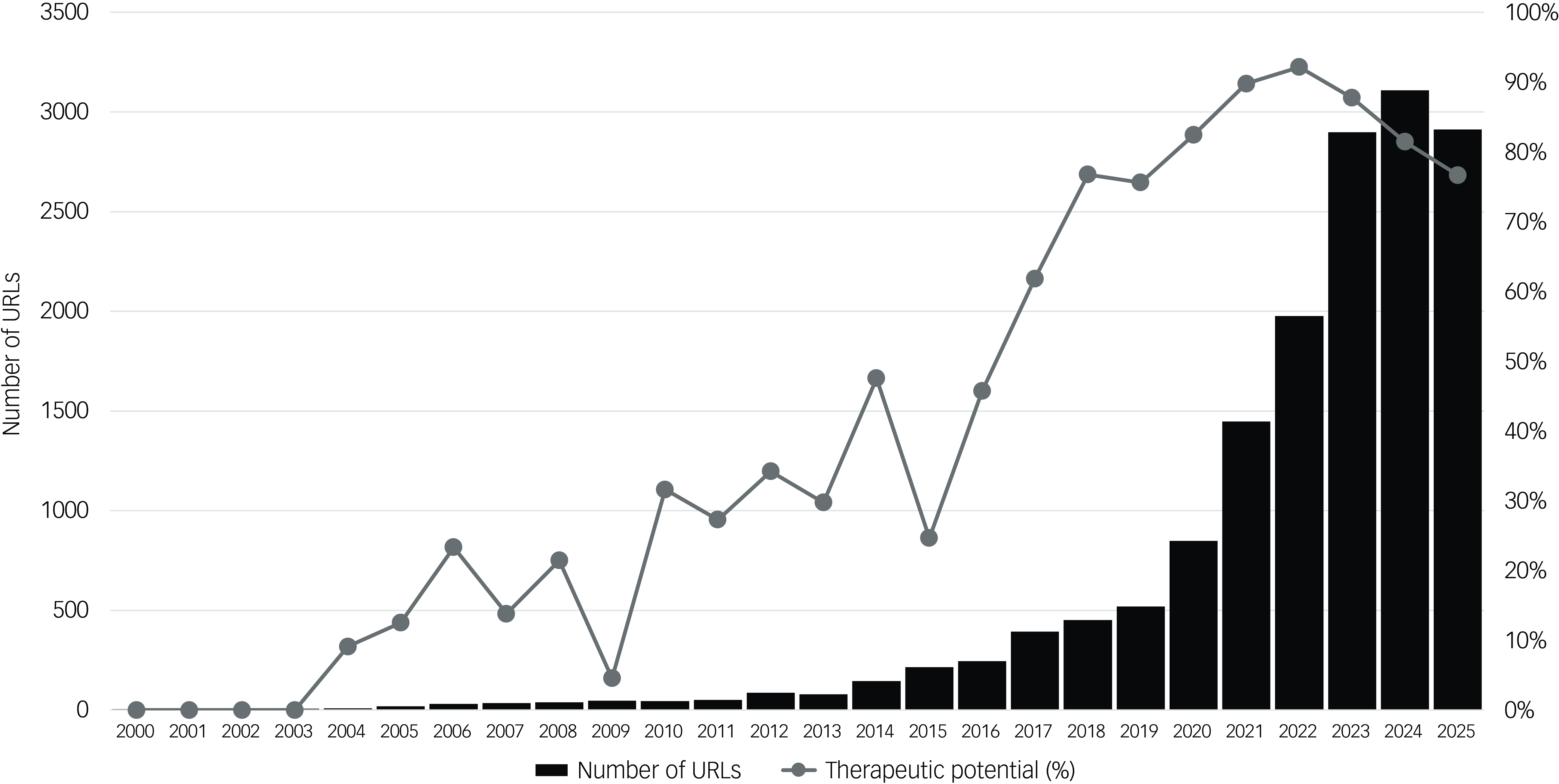

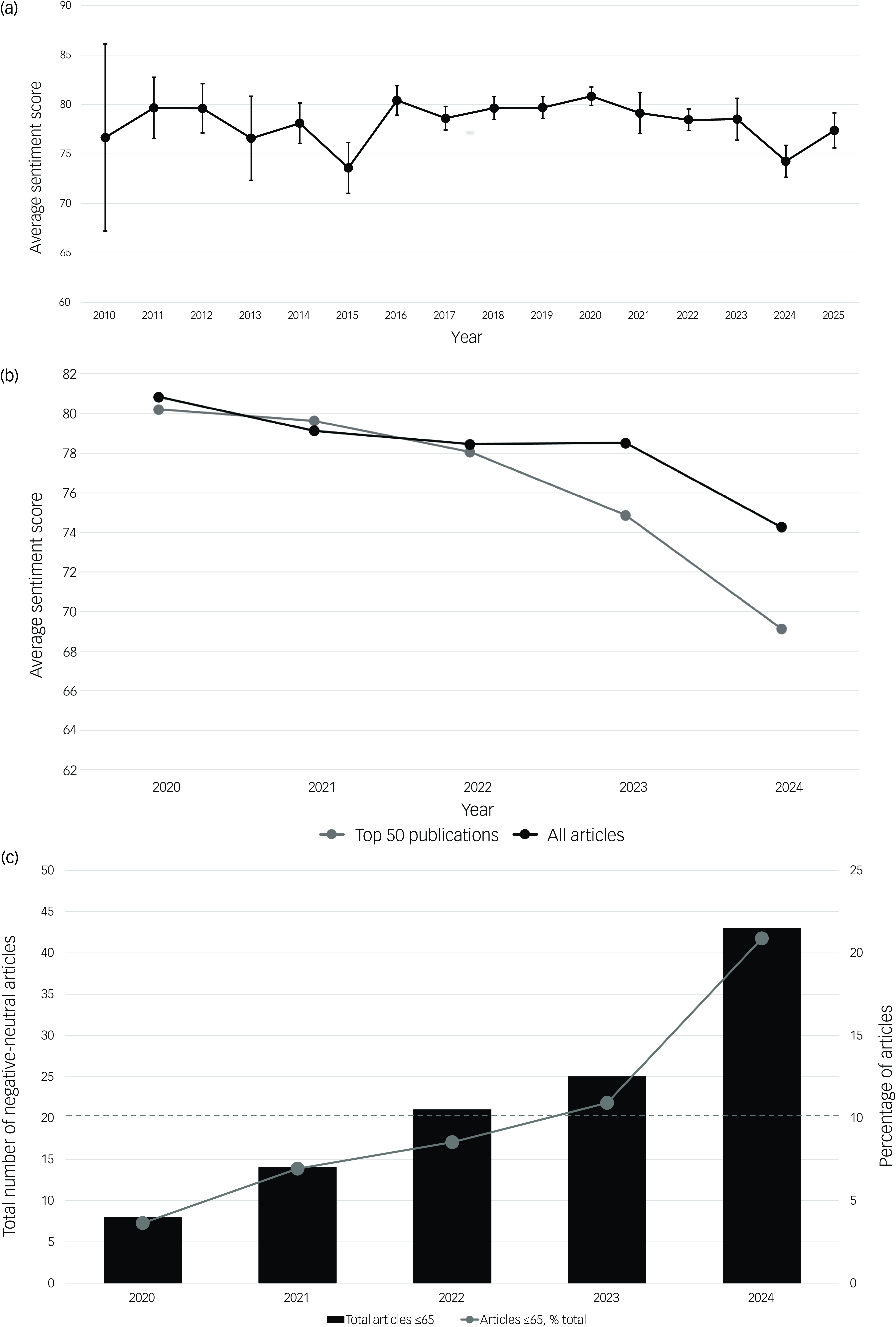

A total of 3747 URLs were screened, of which 88.3% (3308) were included in the analysis (Supplementary Materials, Appendix A). Of these articles, 65.5% (2168) were judged by artificial intelligence to primarily pertain to the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs. The proportion of media articles relating to psychedelics that focus on their therapeutic potential has markedly increased since 2000, with 13.3% (26 of 198) of articles from 2000 to 2009 focusing on this topic compared with 85.5% (1254 of 1470) from 2020 to 2025 (Fig. 2). The total number of URLs appearing within Google News for the search term ‘psychedelics’ increased from a minimum of 4 in 2000 to a maximum of 3108 in 2024, with a 501% increase in total numbers between 2019 and 2024 (520 to 3108) (Fig. 2). Similar trends were observed when articles were sampled from the Harvard Media Cloud online media database (Supplementary Materials, Appendix D).

Fig. 2 Changes in media coverage of psychedelic drugs in the 21st century. Black bars represent the total number of URLs appearing in Google News searches for the term ‘psychedelics’, confined to individual calendar years, with totals labelled on the left-hand y axis. The total for the year 2025 is a projection determined by multiplying the total URLs in January–March by 4. The line chart represents the percentage of analysed articles judged by artificial intelligence as primarily pertaining to the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs for each calendar year.

Analysed articles were published on 1004 different websites (Supplementary Materials, Appendix E), with those published in the top 50 most heavily trafficked English-language media websites accounting for 19.6% (650 of 3308) of the data-set (Supplementary Materials, Appendix F). Individual websites with the most articles focusing on the therapeutic potential of psychedelics included VICE (62 articles), The Guardian (61 articles), Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (55 articles), Business Insider (53 articles) and The New York Times (48 articles) (Supplementary Materials, Appendix G).

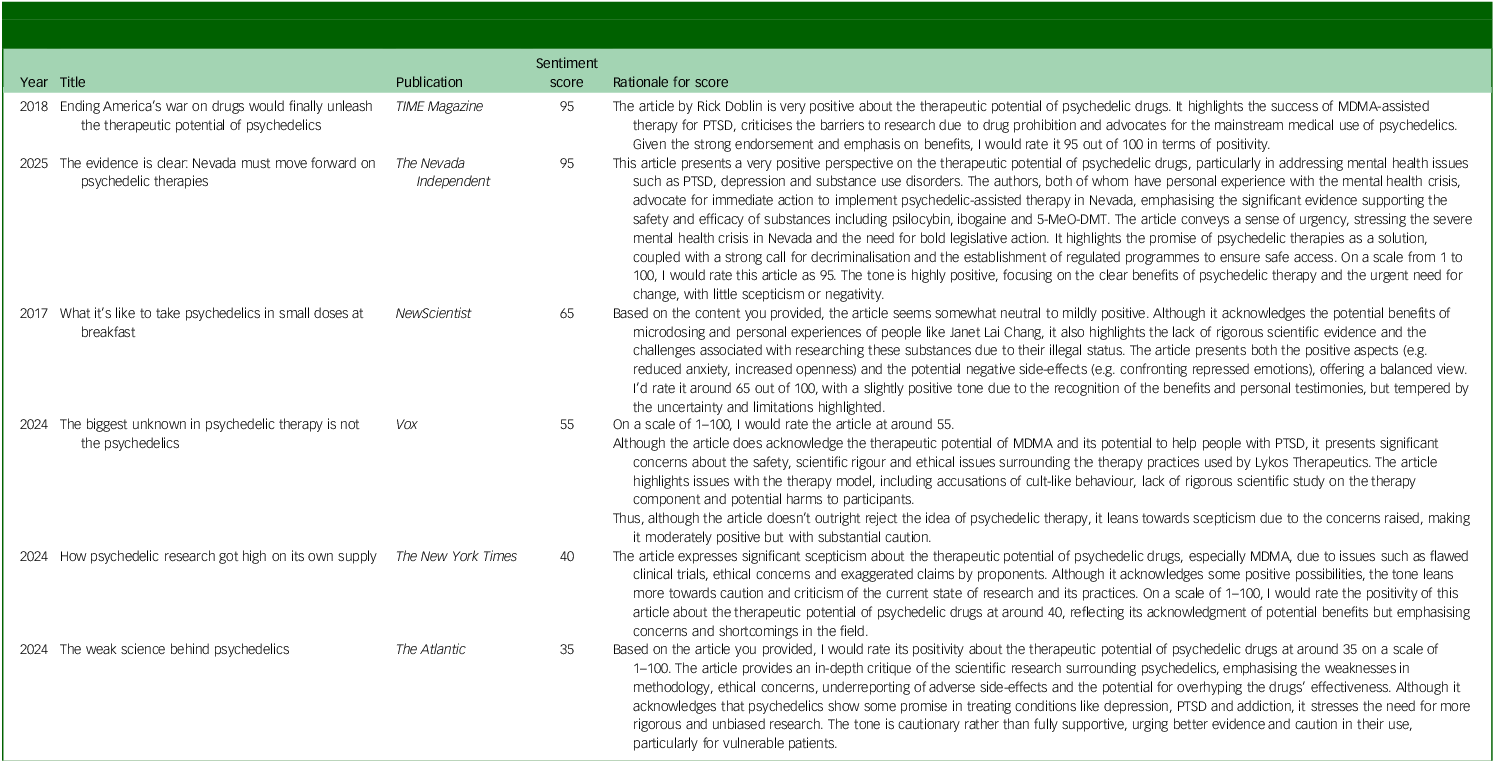

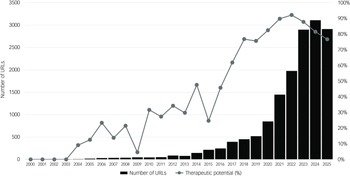

Table 1 provides examples of analysed articles, alongside sentiment scores and rationales produced by artificial intelligence to offer context for quantitative analysis.

Table 1 Examples of artificial intelligence sentiment analysis. Artificial intelligence was asked to rate the positivity of individual articles about the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs, on a scale of 1–100, where 100 denotes very positive and 1 very negative. Example artificial intelligence responses are shown

MDMA, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; 5-MeO-DMT, 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine.

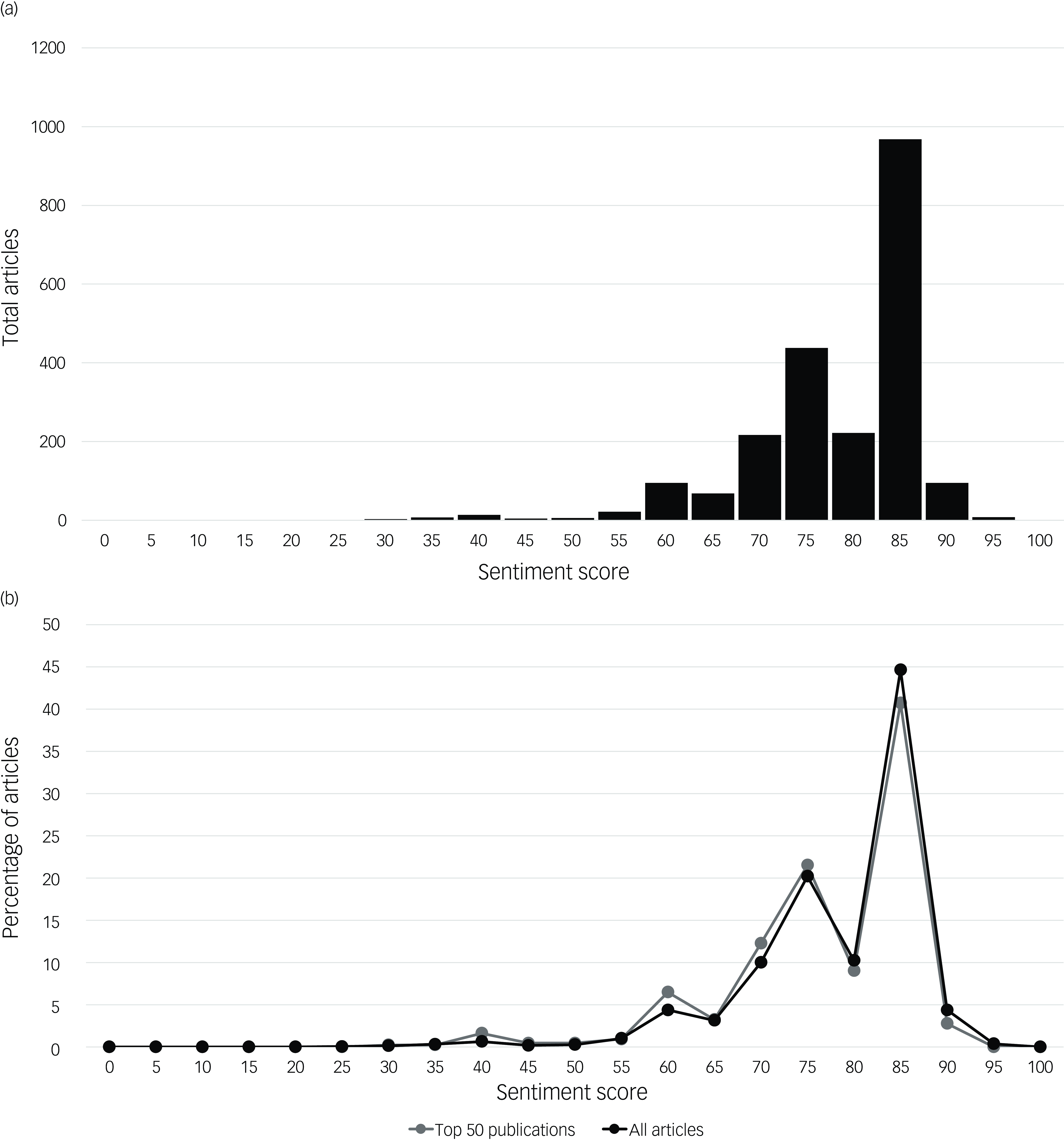

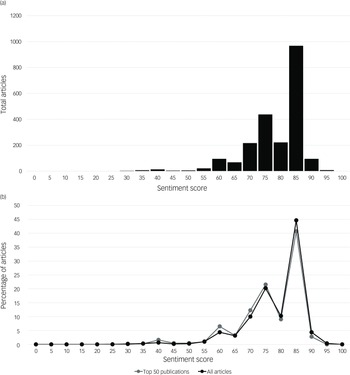

Overall, 21st-century media sentiment regarding the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs was heavily skewed towards positive portrayals (Fig. 3(a)), with 98.7% of articles having a score of 50 or greater (2139 of 2168) and 89.9% having a score of 70 or greater (1948 of 2168). Extreme positive portrayals (sentiment score ≥90) accounted for 4.8% (103 of 2168) of all articles, while negative portrayals (sentiment score <50) accounted for only 1.3% (29 of 2168). Similar results were found among the top 50 most trafficked English-language media websites (Fig. 3(b)), with an average sentiment score of 76.8 (n = 432) compared with 78.9 among websites outside the top 50 (n = 1736). For the the top 50 online media outlets with at least 5 articles pertaining to the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs in the data-set (n = 20), average sentiment ranged from a minimum of 67.0 (Daily Mail) to a maximum of 80.9 (CNN) (Supplementary Materials, Appendix G).

Fig. 3 Media sentiment towards the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs in the 21st century. (a) Bar chart demonstrating the total number of articles with each sentiment score as determined by the large language model. (b) Line chart demonstrating the percentage of all articles with specific sentiment scores from article subgroups.

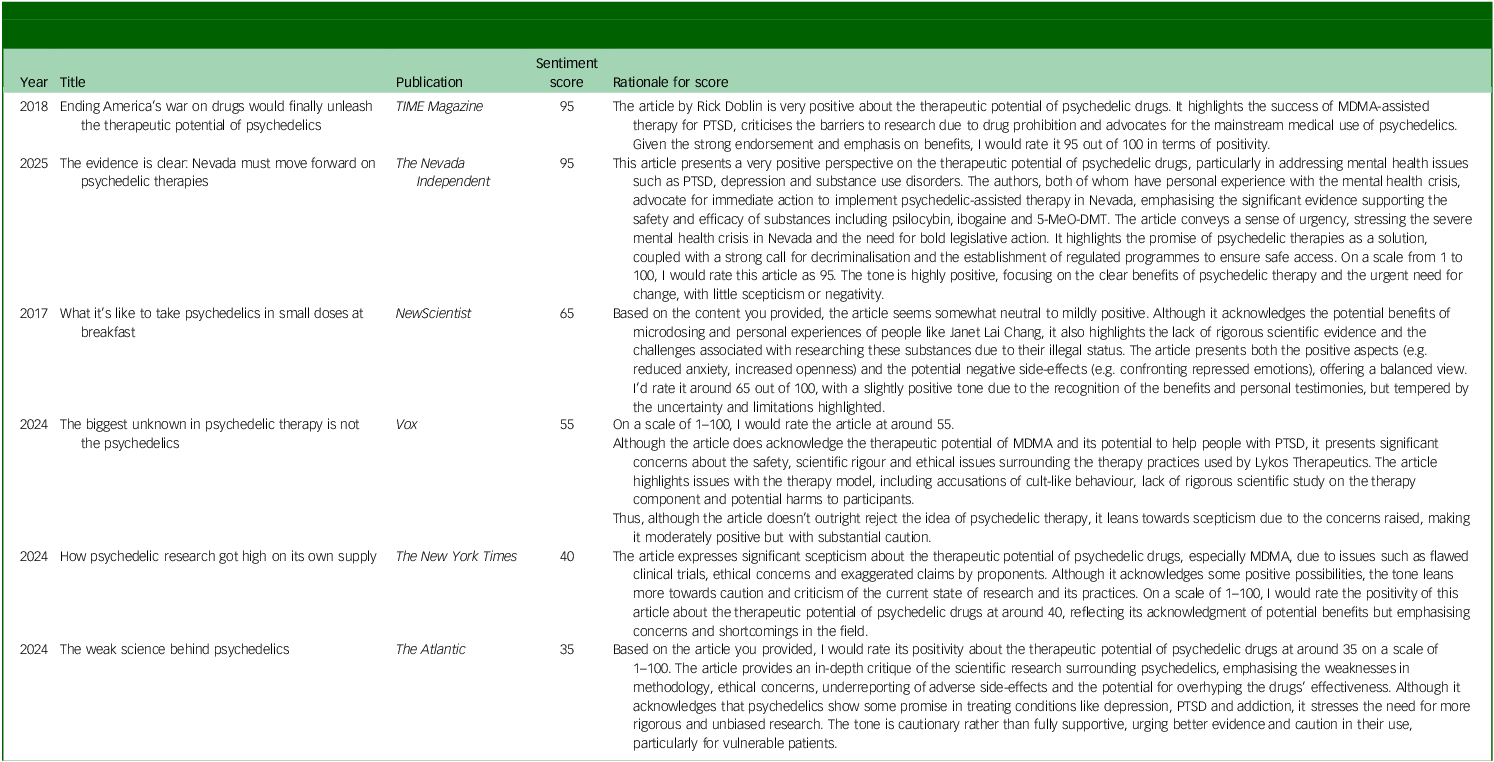

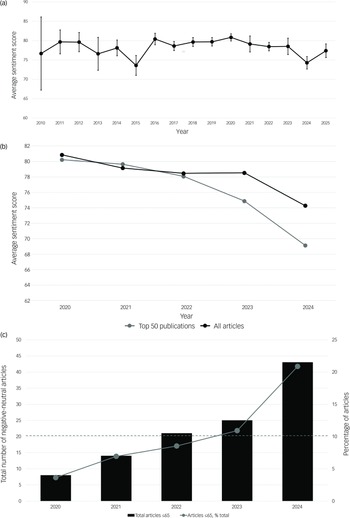

Average media sentiment from 2010 to 2025 is depicted in Fig. 4(a), ranging from a minimum of 73.6 in 2015 to a maximum of 80.8 in 2020. A statistically significant decline in sentiment occurred between 2020–2023 and 2024, the year in which the FDA application for MDMA-AT was not approved (2020–2023, 79.2; 2024, 74.3, P < 0.00001; Mann–Whitney U-test). Absolute declines in sentiment were greater in magnitude for the top 50 publications (Fig. 4(b)). Both the total number and proportion of analysed articles with negative-neutral sentiment (sentiment score ≤65) increased annually from a trough in 2020 until a peak in 2024, with negative-neutral articles accounting for only 3.6% of articles in 2020 compared with 20.9% in 2024 (Fig. 4(c)).

Fig. 4 Temporal shifts in media sentiment towards the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs. (a) Average sentiment score for individual years from 2010 to 2025, with bars representing 95% confidence intervals. The year 2025 sampled articles from only 2 calendar months (January and February). (b) Average sentiment score during a period of decline in sentiment from 2020 to 2024, distinguishing between article subgroups. (c) Increases in the absolute numbers (black bars) and percentages of negative-neutral articles (grey line) (sentiment score ≤65) from 2020 to 2024, with the left-hand y axis indicating the total number of negative-neutral articles and the right-hand y axis indicating the percentage of articles. The dashed line indicates the percentage of negative-neutral articles within the entire data-set.

Among 70 randomly sampled articles from three sentiment score tiers (0–49, 50–74, 75–100) scored by human raters, average artificial intelligence sentiment scores were both strongly correlated, and often concordant with, average human scores (Pearson’s r = 0.88, 95% CI [0.81, 0.92]; P < 0.00001, complete concordance coefficient 0.84) (Fig. 1(a)). Correlations of artificial intelligence scores with individual human raters varied widely (minimum correlation, r = 0.28; maximum correlation, r = 0.93) (Supplementary Materials, Appendix H). There was no significant difference when comparing all human sentiment scores versus all artificial intelligence scores (Mann–Whitney U-test; average artificial intelligence score, 61.9; average human score, 60.8). Artificial intelligence sentiment scores were slightly higher than those of human raters for articles with positive sentiment (average 73.1 v. 67.6 for humans), and slightly lower for those with negative sentiment (average 39.1 v. 46.0 for humans).

Figure 1(b) shows all artificial intelligence and human sentiment scores for each sampled article. Artificial intelligence had high interrater reliability across repeated iterations of sentiment scoring (ICC 2,k for article subgroups 1, 2, 3 = 0.94, 0.93 and 0.93, respectively), while human raters had comparatively weak interrater reliability (ICC 2,k for article subgroups 1, 2, 3 = 0.56, 0.50 and 0.51, respectively) (Supplementary Materials, Appendix B).

The subject matter of 30 semi-randomly sampled articles was assessed by human raters regarding whether they primarily pertained to the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs. Majority human opinion concurred with artificial intelligence for 76.7% (23 of 30) of articles. Concurrence between human intelligence and artificial intelligence was higher for articles with unambiguous content, with artificial intelligence agreeing with the human majority for 89.5% (17 of 19) of these articles compared with 54.5% (6 of 11) of articles with ambiguous content (see Methods).

Discussion

This study has several key results. As anticipated, our results indicate a dramatic increase in media interest in psychedelic drugs since the beginning of the 21st century, which has coincided with a subject matter shift towards their therapeutic potential. Although 21st-century media have been heavily skewed towards positive coverage of their therapeutic potential, this coverage has been only moderately positive on the study scale, with articles sampled from the top 50 media outlets carrying an average sentiment score of 76.8 out of 100. Although the average sentiment score has been moderately positive throughout the 21st century, it significantly declined in 2024 and the proportion of negative-neutral articles (sentiment ≤65) has been steadily increasing since reaching a trough of 3.6% in 2020.

The method of using a LLM to quantify sentiment was validated by comparison with 29 human raters. Artificial intelligence sentiment scores were highly correlated with average human scores, and often concordant (Fig. 1(a)). This suggests that the use of the LLM to measure sentiment, as employed in this study, is an overall close approximation of aggregated human intelligence performing the identical task. Moreover, the LLM was substantially more reliable in its measurements than were human raters. In principle, our general approach to sentiment analysis could be broadly utilised across other types of media studies and the social sciences.

Our study has several limitations. Analysed articles were sampled from the most relevant articles from each calendar year, as determined by the Google News search engine. Thus, indexing procedures from Google News will impact the sample and could have led to sampling bias. For example, Google News could be more likely to index positively framed articles due to increased reader engagement, although we did not find any relationship between article index rank and sentiment score within our data-set (Supplementary Materials, Appendix I). Google News is also unlikely to comprehensively index all possible media articles. While this is a socially important sample, given that Google is the most widely used search engine, 33 the use of other approaches to sampling of online media articles could lead to distinct results. Our use of the search term ‘psychedelics’ – although this term is now commonly used to refer to this class of drugs, including by the National Institute on Drug Abuse 34 – may have biased results towards positively framed articles relative to the use of other search terms such as ‘hallucinogen’. Moreover, the term psychedelic is broad and may refer to a variety of heterogeneous compounds in the context of a Google search (e.g. psilocybin, LSD, ketamine, MDMA). This limits our knowledge of which specific drugs with distinct effects are being evaluated in the data-set, and to what degree.

The underlying mechanics of how the LLM determines sentiment scores cannot be known at a granular level due to the complexity of the model, and there is a potential for misinterpretation associated with any limitations of the model. The use of other LLMs could produce different results. The use of the phrase ‘therapeutic potential’ in identifying article subject matter, which addresses the fact that psychedelic drugs do not have widely accepted therapeutic uses, may lead to articles that are negative about psychedelic drug use being excluded from sentiment analysis. Insofar as our data are viewed as a general proxy for media sentiment towards psychedelics, this could lead to an overestimation of average sentiment. However, that is unlikely to make a material impact on sentiment analysis for 2020–2025, given that 85.3% of these articles were deemed to focus on the therapeutic potential of psychedelics. Articles were sampled from only the first 2 months of 2025, which may have led to sampling biases unique to this calendar year. Increases in the sample size of human-rated articles would offer further precision for the determined correlation between human and artificial intelligence raters.

Our results have several implications that can inform ongoing dialogue about the societal value of psychedelic drugs, and the impact of media coverage on their perception. Prior commentators have expressed concerns about the negative effects of sensationalistic positive media coverage of psychedelic drugs. Reference Yaden, Potash and Griffiths19 Although our results indicate a marked positive skew in media coverage, overall sentiment was consistent with only a moderately positive outlook towards the therapeutic potential of psychedelics. However, this persistently positive media sentiment probably played a role in the decision of voters and state legislators in several US states to legalise the use of psychedelic drugs despite a lack of federal approval for use within medical settings, which could have negative effects on public health. It may have also contributed to an increase in recreational use, Reference Patrick, Miech, Johnston and O’Malley35 which can also have deleterious effects. Reference Perna, Trop, Palitsky, Bosshardt, Vantine and Dunlop36–Reference Simonsson, Hendricks, Swords, Osika and Goldberg39 Elevated media sentiment could also affect the expectations of participants in clinical trials, which may impact subsequent experiences.

Sentiment regarding the therapeutic potential of psychedelics reached a peak in 2020 and declined until reaching a trough in 2024, consistent with the hypothesis that there has been a backlash resulting in part from excessively positive media appraisals. Reference Yaden, Potash and Griffiths19 Several articles in major media outlets were published in 2024 offering comparatively sensationalistic negative characterisations of psychedelic research programmes. Reference Khazan22–Reference Borrell24 This shift coincided with the application for MDMA-AT for PTSD being rejected by the FDA, a decision which was criticised by various groups. Reference Nuwer26–Reference Xenakis28,Reference Buntz40,Reference Stapleton41 These circumstances highlight the complex relationship between science and the media in the case of psychedelic drugs, in which media coverage and public opinion may have a greater impact on policy-making and regulatory processes than in other fields of research. Various commentators have emphasised that the scientific evaluation of psychedelic therapies has been held to uniquely stringent standards in regulatory settings relative to other approved and widely used psychiatric interventions. Reference Nuwer26,Reference Buntz40,Reference Hardman42,Reference Hardman43 These assessments echo the viewpoint of a recent historian of 20th-century psychedelic research, who have argued that the scientific evaluation of research results in the field was meaningfully affected by worsening public sentiment, rather than by scientific quality or clinical utility. Reference Oram5

Classical psychedelic drugs are considered to act psychologically as meaning–response magnifiers Reference Hartogsohn44,Reference Hartogsohn45 or amplifiers of consciousness Reference Grof46 that increase the psychological intensity of experience. Accordingly, the context of their use is probably a key factor in any sustained psychological effects, whether positive or negative. Reference Carhart-Harris, Roseman, Haijen, Erritzoe, Watts and Branchi47 Like most drugs in medical usage, they may be helpful when used in tailored settings by certain individuals but harmful in other circumstances.

Thus, individual anecdotes characterising the results of psychedelic use should be weighted accordingly, because these may suggest unrealistic projections of the results of psychedelic drugs being used at scale within specific circumscribed settings. However, dramatic individual cases – regardless of whether the outcome is positive or negative – often attract attention in the popular media. Reference Siff2,Reference Pollan18,Reference Nuwer26,Reference Chao-Fong37,Reference Goldhill48–Reference Rosman and Egan51 Media outlets are directly incentivised to maximise attention, probably to an even greater degree in the social media era. This incentive structure can contribute to a biased dissemination of information, which may contribute to excessive hype or moral panic regarding psychedelic drugs. Reference Siff2,Reference Yaden, Potash and Griffiths19 In this context, it is especially crucial for progress within the field of psychedelic medicine that researchers, clinicians, regulators and policy-makers focus on aggregated scientific evidence as the primary source of information regarding the potential therapeutic applications of psychedelic drugs.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10974

Data availability

Data access statement: D.A.B. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for their integrity and the accuracy of the data analysis. Data-sharing statement: data will be shared upon request for research purposes at the discretion of the study authors.

Acknowledgement

We thank Sandeep Nayak MD for his recommendations regarding study design and data interpretation.

Author contributions

Study design: D.A.B., B.C.E., D.J.H.; data collection: D.A.B., B.C.E., M.S., H.M.D., N.P., A.D.M., R.A., M.K.S., J.Y., M.V., G.W., A. Anandarajah, J. Steinle, A.D., M.D.-T., S.A.A., R.B., H.W., J. Sridhar, A.P., S.C., M.I., A. Adeyemi, K.S., B.D.R., S. Shankar, U.J., Z.A., S. Sharma, B.K., S.M., R.G.; data analysis and interpretation: D.A.B., H.M.D., A.D.M., A. Anandarajah, B.D.R., B.C.E., D.J.H., C.B.N.; drafting of manuscript: D.A.B.; critical review and final approval of manuscript: D.A.B., M.S., H.M.D., N.P., A.D.M., R.A., M.K.S., J.Y., M.V., G.W., A. Anandarajah, J. Steinle, A.D., M.D.-T., S.A.A., R.B., H.W., J. Sridhar, A.P., S.C., M.I., A. Adeyemi, K.S., B.D.R., S. Shankar, U.J., Z.A., S. Sharma, B.K., S.M., R.G., B.E., D.J.H., C.B.N.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH R25MH112473. The funder had no role in study design, data collection, review of the manuscript or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of interest

M.S., H.M.D., N.P., A.D.M., R.A., M.K.S., J.Y., M.V., G.W., A. Anandarajah, J. Steinle, A.D., M.D., S.A.A., R.B., H.W., J. Sridhar, A.P., S.C., M.I., A. Adeyemi, K.S., B.D.R., S. Shankar, U.J., Z.A., S. Sharma, B.K., S.M. and R.G. have no conflicts of interest to disclose. D.A.B. is a co-investigator on a clinical trial sponsored by Definium Therapeutics, with no current or prior financial compensation for this role. B.C.E. is a co-investigator on a current Compass Pathways clinical trial, with no current or prior financial compensation for this role. He is a site co-investigator for Bipotype-assigned Augmentation Approach in Resistant Late Life Depression (NIMH UG3 MH127353-01). D.J.H. reports grant funding (to Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene, New York State) from the following: Compass Pathways, Relmada, Marinus, Intracellular Therapies, Beckley Scientific, NIAMS (M. Walker, PI) and Velocity Foundation (Columbia; J. Markowitz, PI); has served on scientific advisory boards for Reset Pharmaceuticals and Mind Medicine Inc.; and has received honoraria from Johns Hopkins University Press and Columbia University Press. C.B.N. is supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Mental Health, the Texas Child Mental Health Consortium and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. He is a consultant for Engrail Therapeutics, Clexio Biosciences Ltd, Galen Mental Health LLC, Goodcap Pharmaceuticals, ITI Inc., Sage Therapeutics, Senseye Inc., Precisement Health, Autobahn Therapeutics Inc., EMA Wellness, Denovo Biopharma LLC, Alvogen, Acadia Pharmaceuticals Inc., Reunion Neuroscience, Kivira Health Inc., Wave Neuroscience, Patient Square Capital LP, Invisalert Solutions Inc. and Neurocrine Biosciences, LLC. He owns the following patents: Method and devices for transdermal delivery of lithium (US 6,375,990B1); Method of assessing antidepressant drug therapy via transport inhibition of monoamine neurotransmitters by ex vivo assay (US 7,148,027B2); and Compounds, Compositions, Methods of Synthesis, and Methods of Treatment (CRF Receptor Binding Ligand) (US 8,551, 996 B2). He owns stock in Corcept Therapeutics Company, EMA Wellness, Precisement Health, Signant Health, Galen Mental Health LLC, Kivira Health Inc., Denovo Biopharma LLC and Senseye Inc. He serves on the editorial board of British Journal of Psychiatry Open, but has not been involved in any way in the editorial review of this manuscript.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.