Introduction

Periods of crisis and collapse have often been regarded as relevant phases for investigating the processes of change in human societies. These phenomena have been seen either as catastrophic events causing profound fractures and revolutions in historical processes, or as phases of cultural transformation and active response by a human population with new adaptive innovations to environmental or political stress. The twelfth century BC was certainly one of the most relevant periods of transformation in the Near East, marking the end of the Late Bronze Age. Collapse was, however, not a generalised event; rather, different regions responded differently to the dismantling of previous palatial systems, and produced diversified outcomes.

At Arslantepe in the Malatya province in south-eastern Turkey (Figure 1), recent results have opened new perspectives on the crucial post-Hittite (c. 1200–700 BC) developments. The site owes most of its fame to the extraordinary results of its prehistoric and proto-historic phases (Frangipane Reference Frangipane2010, Reference Frangipane2012a & Reference Frangipaneb, Reference Frangipane, Meller, Hahn, Jung and Risch2016). It was, however, originally known for the Iron Age monumental discoveries unearthed in the 1930s and 1960s: primarily, the famous ‘Lions Gate’ relating to the period during which Arslantepe became the capital of the neo-Hittite Kingdom of Melid (Delaporte Reference Delaporte1940; Pecorella Reference Pecorella1975; Hawkins Reference Hawkins2000: 282–329; Manuelli Reference Manuelli2013).

Figure 1. Map of Anatolia showing Arslantepe and the main Iron Age sites (credit: MAIAO, Missione Archeologica Italiana nell'Anatolia Orientale).

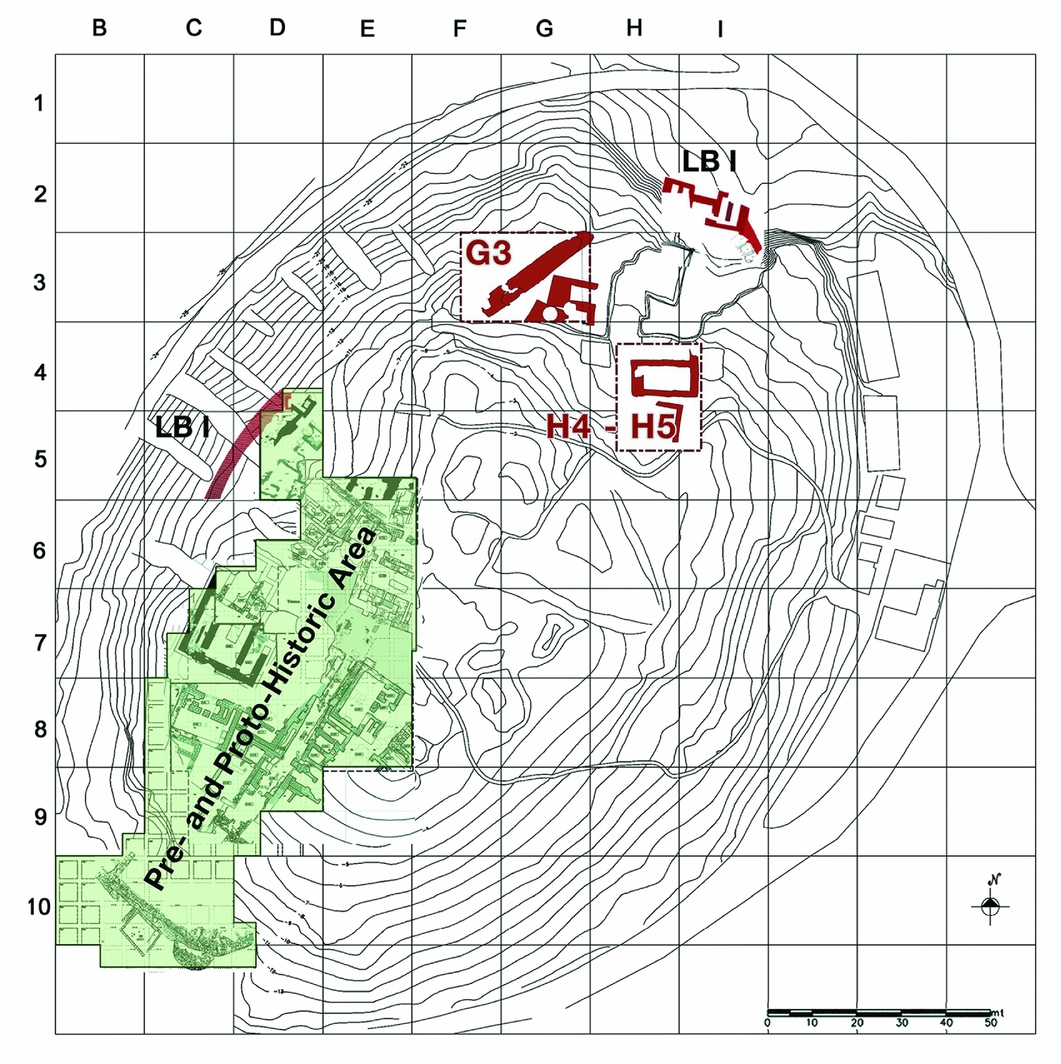

Recent excavations in 2008–2010 have shown the existence of a continuous sequence of levels from the tenth century BC and the Assyrian occupation (seventh century BC) of the site (Liverani Reference Frangipane, Meller, Hahn, Jung and Risch2012), and have raised questions concerning the resilience and regeneration of local elites during the post-Hittite phase. In 2015, a new project of field research aimed to investigate the periods that followed the breakup of the Hittite Empire, and to understand the process of change that influenced the formation of the local Iron Age polity. The excavation was carried out on both the outskirts of the mound (G3 area) and the centre of the citadel (H4–5 areas), in order to investigate the features of the political core of the neo-Hittite town in the period of its maximum splendour (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Plan of the mound with the 2015–2016 excavated areas (credit: MAIAO).

The Early Iron Age fortified levels

The activities on the northern edge of the mound (G3) revealed two monumental levels dating to the twelfth and eleventh centuries BC (Figure 3). The later level is characterised by a massive 4m-thick fortification wall, preserved for a length of approximately 30m. Two figurative bas-reliefs—which might have decorated a city-gate—had been discovered in 2010, and were sealed by the destruction that marked the end of the Early Iron Age settlement at the beginning of the tenth century BC (Manuelli & Mori Reference Manuelli and Mori2016: 219–22). The 2016 excavations demonstrated that the fortification wall had a total preserved height of nearly 4m, thus stressing its impressive monumentality.

Figure 3. Arslantepe, facing west. Sector G3 with the twelfth- to eleventh-century BC monumental town wall and the ‘green building’ (credit: MAIAO).

The earlier levels also revealed substantial architectural features. Two large rooms with thick plastered walls of greenish mud-brick (‘green-building’) showed several phases of construction and use, but no traces of fire destruction. The almost total lack of in-situ material suggests that they were abandoned before the construction of the town wall, perhaps following a new urban plan.

Evidence of an earlier structure with a round wall—a possible enclosure or tower—was found beneath these rooms in 2016. The fortification system, therefore, seems to have been constantly rebuilt, without significant interruptions from the final Late Bronze Age up to the Iron Age.

The neo-Hittite inner citadel

The new excavation areas opened in 2016 in the inner citadel (H4–5) revealed a remarkable sequence of buildings, mostly dating to the ninth to seventh centuries BC (Figure 4). The area was probably used as a courtyard during both the Assyrian and the neo-Hittite periods. Two damaged superimposed stone-slab floors, belonging to the brief Assyrian occupation, were also excavated. They sealed the neo-Hittite remains, which comprised a series of large post-holes and a few squared stone-blocks symmetrically distributed over a wide area, suggesting the presence of a series of pillars and columns recalling the ‘pillared hall’ found close to the ‘Lions Gate’ in 2008 (Liverani Reference Liverani, Lippolis and Martino2011).

Figure 4. Arslantepe, facing east. The H4–5 sectors with the ninth- to seventh-century BC excavated sequence (credit: MAIAO).

An earlier neo-Hittite level, consisting of a large building whose internal layout had been repeatedly modified by several phases, was also unearthed. Three rooms were preserved: a large hall of approximately 100m2 with a double-chambered hearth and two smaller rooms adjoining it on the northern side.

The floor of the large hall sealed part of a small pit, within which a finely carved ivory plaque—reminiscent of the ‘Nimrud ivories’ and unique so far at Arslantepe—was discovered (Figure 5). The pit was located between this building and an underlying monumental hall, also dated to the neo-Hittite period. This positioning confirms the date of the ivory plaque to the ninth to eighth centuries BC. The early monumental hall had imposing stone wall-foundations and appears to have been a special structure, possibly with a non-domestic function (Figure 6).

Figure 5. The ivory plaque (credit: MAIAO).

Figure 6. Arslantepe, facing south. The large neo-Hittite monumental hall in the centre of the town (credit: MAIAO).

Concluding observations

The 2015–2016 excavations in the northern area of Arslantepe provide important insights into two crucial phases of the site in the post-Hittite period, while also illuminating the development of the Syro-Anatolian societies at the transition from the second to the first millennium BC. The monumental sequence revealed in sector G3 testifies to settlement continuity following the collapse of the Hittite Empire, and shows interesting processes of cultural regeneration after the crisis that affected the Near Eastern societies during the late thirteenth century BC. The dramatic end of the Early Iron Age citadel at Arslantepe was followed by another magnificent period. The political prominence, cultural innovations and external relations developed by the neo-Hittite Kingdom of Melid during the ninth and especially the eighth centuries BC are reflected in important discoveries from the newly opened H4–5 areas, which promises significant future discoveries.

Acknowledgements

The excavations at Arslantepe were funded by the Sapienza University of Rome and the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The 2016 campaign also benefited from a generous grant awarded by the National Geographic Society (grant 990116).