A broad range of social and economic factors shapes the inequalities that have influenced human societies throughout history, often affecting access to resources and opportunities in ways that often persist across generations (Ferreira et al. Reference Ferreira, Gisselquist and Tarp2022; Mare Reference Mare2011; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2006). At a time when equity and inclusion policies worldwide are facing growing scrutiny, understanding inequality is not only a scholarly exercise but also important for contextualizing challenges and informing meaningful action. Within this broad framework, gender inequalities have been documented in various dimensions and disciplines, including leadership positions (Ely et al. Reference Ely, Ibarra and Kolb2011; Rhode Reference Rhode2017; Ruminski and Holba Reference Ruminski and Holba2012) and participation in science (Avolio et al. Reference Avolio, Chávez and Vílchez-Román2020; Carli et al. Reference Carli, Alawa, Lee, Zhao and Kim2016; Ceci and Williams Reference Ceci and Williams2011; Handelsman et al. Reference Handelsman, Cantor, Carnes, Denton, Fine, Grosz and Hinshaw2005). These disparities often stem from biases and social norms that disproportionately affect women, which is evident in several academic fields, including archaeology.

Numerous studies in archaeology have demonstrated that gender is a key factor in grant funding (Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Mills, Herr, Burkholder, Aiello and Thornton2018; Heath-Stout and Jalbert Reference Heath-Stout and Jalbert2023), publications (Bardolph Reference Bardolph2014; Fulkerson and Tushingham Reference Fulkerson and Tushingham2019; Hanscam and Witcher Reference Hanscam and Witcher2023; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2020; Hutson Reference Hutson2002; Hutson et al. Reference Hutson, Johnson, Price, Record, Rodriguez, Snow and Stocking2023; Watts Reference Watts2024), career paths (Chase Reference Chase2021; Díaz-Andreu Reference Díaz-Andreu, Moen and Pedersen2024; Finkel and Olswang Reference Finkel and Olswang1996; Overholtzer and Jalbert Reference Overholtzer and Jalbert2021; Parezo and Bender Reference Parezo and Bender1994), research topics (Horowitz and Brouwer Burg Reference Horowitz and Burg2024; Santana Quispe Reference Santana Quispe2019), and sexual harassment (Coltofean-Arizancu et al. Reference Coltofean-Arizancu, Gaydarska, Plutniak, Mary, Hlad, Algrain and Pasquini2023; Coto Sarmiento et al. Reference Coto Sarmiento, Anés, Martínez, Péreaz, Martínez, Yubero, Díaz-Andreu, Gomariz and Gutiérrez2022; Nieto-Espinet and Campanera Reference Nieto-Espinet, Campanera, Díaz-Andreu, Torres and Gutiérrez2022; Voss Reference Voss2021a, Reference Voss2021b). Many of these studies also examine factors such as race, ethnicity, age, and sexual identity. Originally coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw (Reference Crenshaw1989), intersectionality is a framework that examines how multiple social identities, such as gender, class, and nationality, combine to create systems of discrimination or privilege (Carastathis Reference Carastathis2014; Sterling Reference Sterling, Matić, Gaydarska, Coltofean and Díaz-Guardamino2024). Intersectional approaches have proven effective in analyzing how different identities shape professional and academic opportunities.

Most of this research, however, has focused on North American and European contexts, leaving the status of these issues in other world regions underexplored. This gap limits the global understanding of academic and professional inequalities, leading to policies focused on Global North models. Despite the proven value of intersectional approaches, few studies in Latin America have fully addressed how gender intersects with other axes of inequality, such as ethnicity, class, or nationality. Using Guatemala as a case study, we ask, What role does diversity play in archaeological practice and the production of knowledge in Latin American countries with long histories of exploration and research? More specifically, what dynamics shape inequalities in Guatemala’s archaeological community?

Latin America presents distinct social and institutional dynamics that shape inequalities differently from wealthier regions. For instance, many Latin American universities lack tenure systems, and funding opportunities for research vary across the region. Additionally, institutional policies on maternity leave and childcare support are weak and variable, and professional environments are often influenced by traditional gender norms, with machismo—a mindset emphasizing male dominance and sexist behaviors—posing a significant barrier to gender equity in academia and professional settings (Chant Reference Chant2003).

Without data on the specific challenges faced by researchers in Latin America, these inequalities remain largely invisible to international organizations and scholars. As a result, grant agencies may assume that Latin American researchers face the same challenges as their Global North counterparts. International journals and conferences may also underestimate the impact of language barriers and funding constraints. Consequently, Latin American scholars risk being relegated to peripheral roles in academia, remaining underfunded and underrepresented in influential publications, grants, and policymaking.

Scholars have made significant efforts to understand gender inequalities within Latin American archaeology, with much of this work being led by women through a feminist lens. Research in Mexico (Ruiz Martínez Reference Ruiz Martínez2006, Reference Ruiz Martínez2008), Argentina (Gluzman Reference Gluzman2023; Puebla et al. Reference Puebla, Prieto-Olavarría, Frigolé, Batllori, Laura Salgán, Zárate Bernardi, De La Paz Pompei, da Peña and Yebra2021), Brazil (Ribeiro et al. Reference Ribeiro, Da Silva Formado, Schimidt and Passos2017), and Uruguay (Villarmarzo et al. Reference Villarmarzo, Blasco and Saccone2021) has highlighted women’s contributions to their academic communities, examining how sociopolitical contexts and personal circumstances have shaped individual career trajectories. Studies on scholarly authorship in Peru (Tavera Medina and Santana Quispe Reference Tavera Medina and Quispe2021) and Ecuador (Domínguez Sandoval et al. Reference Domínguez Sandoval, Pazmiño, Auxiliadora Cordero and Cordero2018) reveal that academic publishing is predominantly led by males, despite women’s consistent participation in fieldwork. Other work has also focused on personal experiences that expose sexism in the field (Arroyo Abarca Reference Arroyo Abarca2019; Vásquez Pazmiño Reference Vásquez Pazmiño and Cordero2018). These contributions, while centered on gender, often intersect with other axes of identity such as class, ethnicity, and nationality, although this remains an emerging area of study. Despite these advances, research on these topics in Guatemala remained scarce until recently. In response, we have contributed to these efforts by organizing the First Conference on Diversity in Guatemalan Archaeology in 2021 and conducting research on the current state of diversity within the field.

Here, we present the results of an intersectional analysis of gender and nationality in the dissemination of academic knowledge within Guatemalan archaeology. Our research examines publication trends in Guatemala’s most prominent academic venue, the memoirs of the annual archaeology symposium, as well as two international journals: Latin American Antiquity and Estudios de Cultura Maya. To contextualize our findings, we draw on alumni data from local universities and insights from a survey on the professional roles and perceptions of inequalities among Guatemalan archaeologists (Ponce Reference Ponce2025). This combined-methods approach allows us to bridge institutional data with lived experiences, offering a more nuanced understanding of academic inequality.

Our results indicate that Guatemalan archaeology has been characterized by relative gender parity, but the dissemination of academic knowledge is predominantly led by men, even during periods when female professional archaeologists outnumbered their male counterparts. The purpose of our article is thus twofold: (1) to assess how gender and nationality have shaped archaeological practice and the dissemination of scholarly work and (2) to discuss possible reasons for these discrepancies and offer practical recommendations. We conclude that several factors help sustain the gender gap in this context, particularly socioeconomic and institutional barriers, and expectations of women as caregivers.

Guatemala’s Archaeological Community and the Annual Archaeology Symposium

Guatemala, situated in Central America, is home to numerous archaeological sites that have captured the attention of local and international scholars since the nineteenth century (Figure 1). Today, Maya communities comprise around 40% of Guatemala’s population, reflecting the country’s multiethnic and multicultural character (Censo de Población Reference de Población2019). Nonetheless, academic circles have historically been dominated by non-Indigenous scholars. This imbalance stems partly from the postcolonial legacy and structural racism, which have hindered equitable participation in academia and science (Cojtí Cuxil Reference Cojtí Cuxil2007). These structural barriers continue to influence who leads archaeological research in Guatemala today.

Figure 1. Location of Guatemala.

Despite Guatemala’s rich archaeological heritage, the opportunity to obtain bachelor’s and licenciatura degrees in archaeology is relatively recent (Carpio Rezzio Reference Carpio Rezzio2023; Carpio Rezzio and Martínez Paiz Reference Carpio Rezzio and Martínez Paiz2015; Chinchilla Mazariegos Reference Chinchilla Mazariegos and Nichols2012). Currently, only three universities offer these programs: Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala (USAC), Universidad del Valle de Guatemala (UVG), and the Centro Universitario de Petén (CUDEP), which awarded their first degrees in the 1970s and 1980s. A licenciatura typically involves extensive coursework, field training, and a final research project or thesis. It is the primary qualification for professional archaeologists in Latin America, enabling them to direct research projects and hold professional positions. The length, required professional practice, and final project of a licenciatura make it a greater academic commitment than a bachelor’s degree. Although licenciatura programs have expanded professional opportunities, limited resources and weak institutional development have constrained job opportunities for Guatemalan archaeologists (Carpio Rezzio and Martínez Paiz Reference Carpio Rezzio and Martínez Paiz2015; Chinchilla Mazariegos Reference Chinchilla Mazariegos and Nichols2012).

The development of academic archaeology in Guatemala has also been supported by events that facilitate research dissemination and collaboration. Since 1987, Guatemala’s archaeology symposium has gathered dozens of national and international researchers annually for five days of academic presentations in Guatemala City. The symposium is accessible for students, professionals, tour guides, and the public, with prices ranging from around US$20 to US$40 for attendees and presenters, respectively. Additionally, presenters have the option to publish their papers in the symposium’s proceedings, making recent research findings and ideas available to the public.

It is important to note that, unlike many other Latin American countries, Guatemala lacks established peer-reviewed journals. This absence can hinder academic recognition and career advancement for local researchers. Moreover, on a global scale, while several academic journals are published in Spanish, the most prestigious international journals are in English and are often costly for those without institutional access. As a result, researchers who lack English proficiency and do not have financial or institutional support face significant barriers to accessing data and disseminating their work. These factors contribute to academic inequality, referring to the systemic unequal distribution of resources, opportunities, and recognition within scholarly settings. Given these challenges, the Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala has become a cornerstone for disseminating scholarly knowledge in the country. As the number of local and international researchers working in Guatemala continues to grow, it is essential to examine the role of diversity in archaeological practice and the production of scholarly knowledge. Therefore, this study seeks to answer the following questions: Is there inequality in Guatemalan archaeology in terms of gender and nationality? And who leads the production and dissemination of academic knowledge in this context?

Methods

This study quantified the total number of men and women who published in the conference proceedings of the Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala from 1987 to 2024, as well as the country of academic affiliation of the first author of each paper for a period of 11 years from 2010 to 2021. The primary authors were counted separately because they tend to have greater responsibilities in drafting the manuscript, presenting the research to the public, or interpreting the results, making it an indicator of leadership. This approach, however, has the limitation of gendering participants solely as male or female. We also acknowledge that we are identifying the presumed sex and not necessarily their gender. In cases where identification based on names was challenging, we classified them based on familiarity or from their academic or personal web pages. The gender (n = 15; 0.22%) and country of academic affiliation (n = 16; 1.55%) of a small number of participants could not be identified, and these were excluded from the analysis. Additionally, some papers were authored by individuals outside the discipline of archaeology, such as avocational researchers or professionals from related fields, and were included in the study because their contributions are integral to the symposium’s diverse authorship.

To assess the international dissemination of knowledge by Guatemalan archaeologists, we analyzed the gender and country of academic affiliation of all authors who published in Latin American Antiquity and Estudios de Cultura Maya over a 10-year period (2013–2022), regardless of nationality. Estudios de Cultura Maya is a biannual academic journal ranked in the second quartile (Q2), and Latin American Antiquity is a quarterly journal ranked in the first quartile (Q1). Both journals accept publications in Spanish and were selected for their regional and specialized focus. Additionally, we quantified the authorship positions of contributors affiliated with Guatemalan academic institutions, as authorship order is often considered a relevant factor in academic hiring decisions. Our analysis focused on research articles and reports, and excluded book reviews, editorial contributions, corrigenda, comments, and obituaries. Chi-square (χ2) tests of independence were conducted in SPSS 30 software, and we provide results that were statistically significant at the 0.05 confidence level.

To address the limitations of our approach and obtain additional data, an anonymous survey was conducted in 2021 of 103 Guatemalan archaeologists regarding their perceptions of gender gaps in professional and academic archaeology in the country. We emphasize that the survey was designed as an exploratory effort intended to provide initial insights into the status of inequality within Guatemalan archaeology. The anonymous survey was distributed through a combination of institutional and personal channels. The authors shared the survey within their professional networks, and the Archaeology Department at UVG circulated it through its mailing list. Participation was voluntary, which we acknowledge may have affected the representativeness of our sample. The anonymous survey was distributed via Google Forms and was divided into three parts. First, it asked participants to identify themselves in terms of gender and ethnicity. Subsequently, they provided information about the job positions held throughout their careers with the aim of identifying patterns in occupations and leadership roles. Finally, they were asked whether they perceived gender disparities in professional practice and dissemination of archaeological research in Guatemala. The survey was voluntarily completed by archaeologists at various stages of their professional training, including pregraduates, graduates, and postgraduates. Although only graduates and postgraduates are authorized to direct or codirect archaeological projects, licenciatura candidates and students were included in the sample because they participate in professional practice early on through field and laboratory work. Moreover, scholarly production is not confined to project directors, as students and archaeologists at various professional stages also publish. We now turn to present the results of our study, beginning with the demographic data of professional graduates from local universities.

Results

Demographics

Based on alumni data provided by department chairs, Guatemala produced a total of 297 archaeologists with a licenciatura degree from 1979 to May 2024. The majority graduated from USAC (75.76%), followed by UVG (16.16%) and CUDEP (8.08%). Currently, only these three academic centers offer licenciatura degrees in archaeology. UVG is a private university, whereas USAC and CUDEP are government-funded institutions. CUDEP, an academic extension of USAC located in northern Guatemala, has also produced 41 archaeology technicians, the majority of whom are men (63%). Unlike professionals with a licenciatura degree, archaeology technicians are trained in the practical skills for field and laboratory work but are not typically responsible for directing research projects.

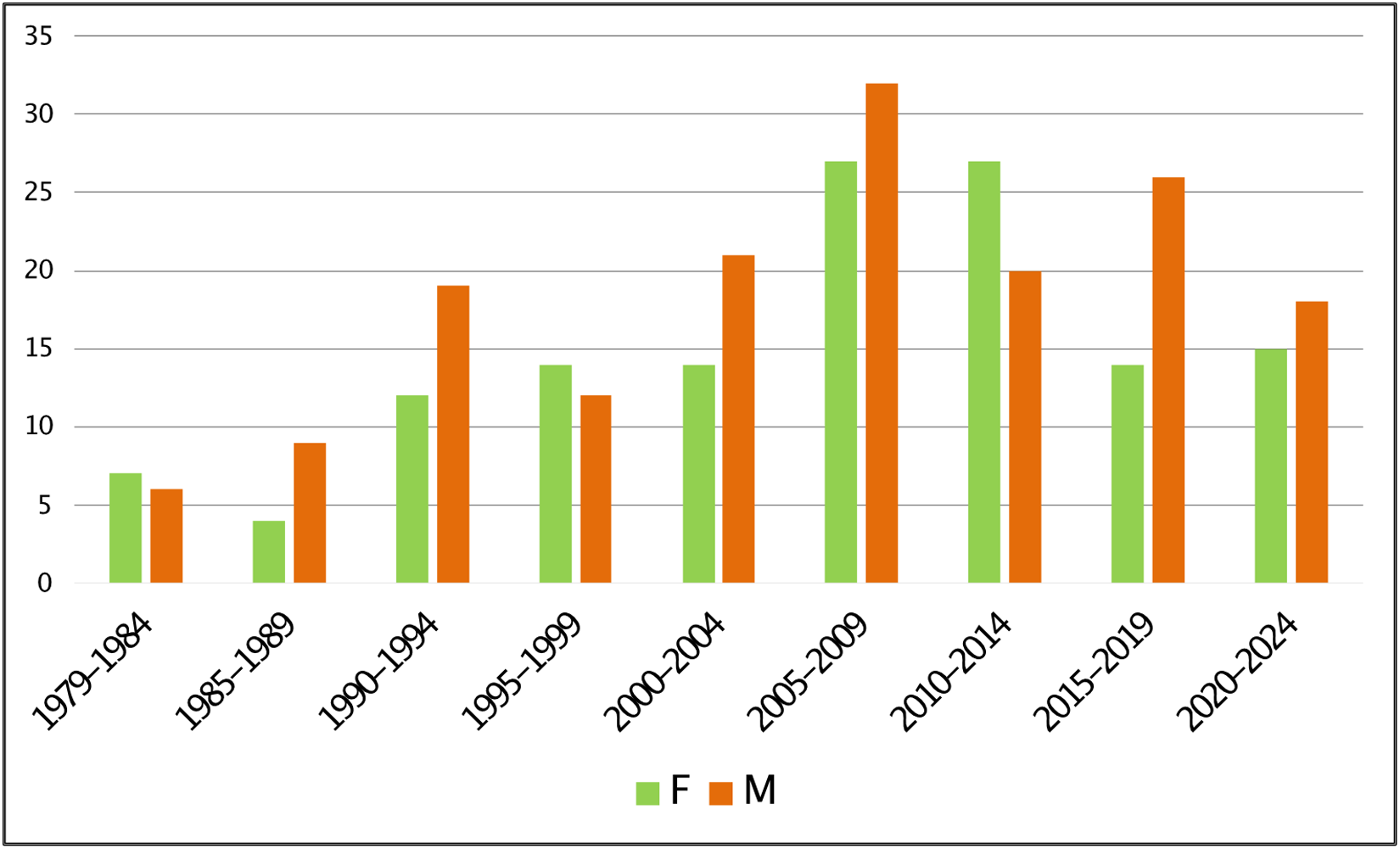

Interestingly, the proportions between male (54.88%) and female (45.12%) licenciatura graduates are relatively equal (χ2 = 51.237; df = 45; p = 0.242). Additionally, women have played an active role in the field since its early years. For example, Marion Popenoe de Hatch was the founder and first archaeology chair at UVG (Barrera Reference Barrera2024), and the first licenciatura graduates (1979–1984) were predominantly women (Figure 2). Among them was Zoila Rodríguez, who later became archaeology chair at USAC (Cáceres Trujillo Reference Cáceres Trujillo2016; Carpio Rezzio Reference Carpio Rezzio2023). These early instances of female academic leadership contrast with current disparities in doctoral attainment and scholarly dissemination.

Figure 2. Gendered distribution of Guatemalan licenciatura graduates from 1979 until May 2024 (N = 297).

According to data provided by departmental chairs, the gender distribution among archaeologists with postgraduate degrees is relatively balanced (N = 92; 51.09% men; 48.91% women). However, men are significantly overrepresented at the doctoral level, comprising 75% of doctorate holders (N = 24). This disparity at the highest academic level may influence research direction and leadership opportunities. Since most doctorates are obtained abroad, this imbalance may further reflect financial and, in many cases, linguistic barriers disproportionately affecting women. Nevertheless, this gap may narrow in the near future, as several women are currently pursuing doctoral studies.

Publication Trends in a National Venue: Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala

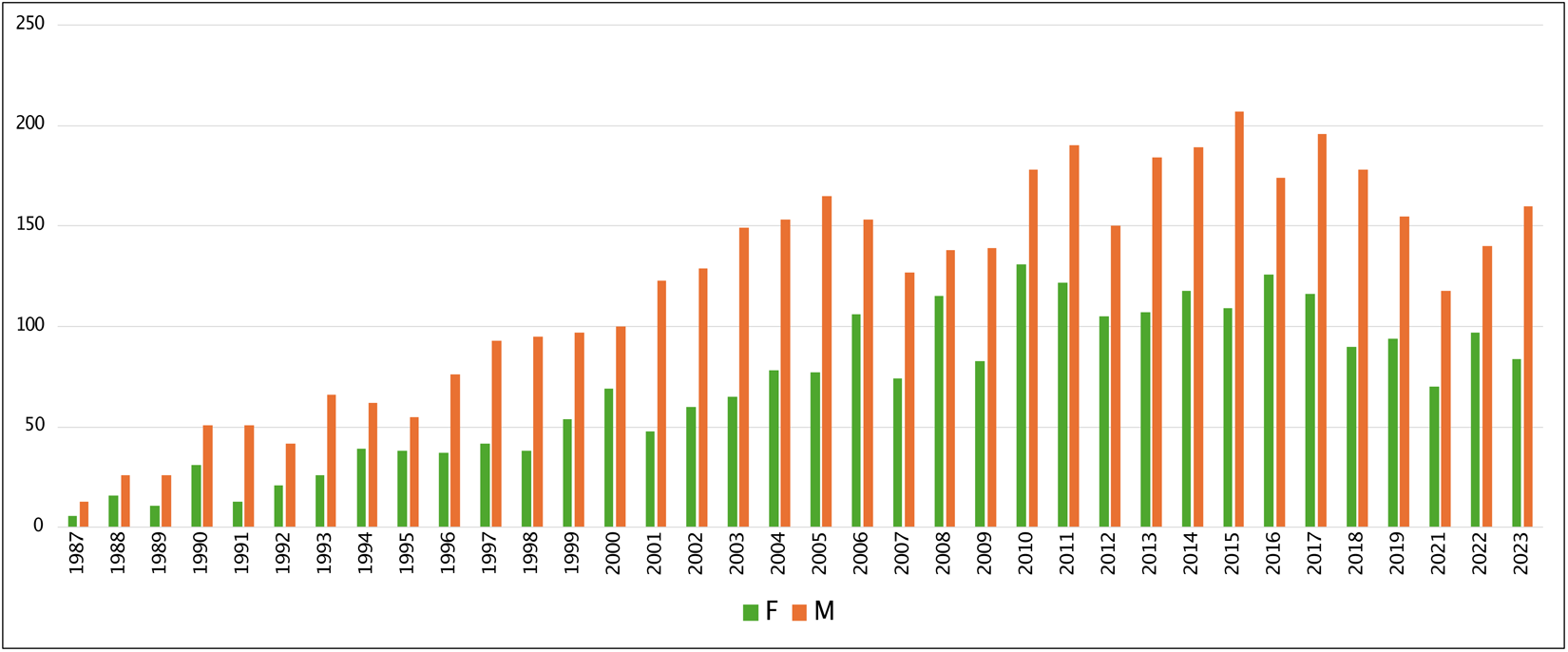

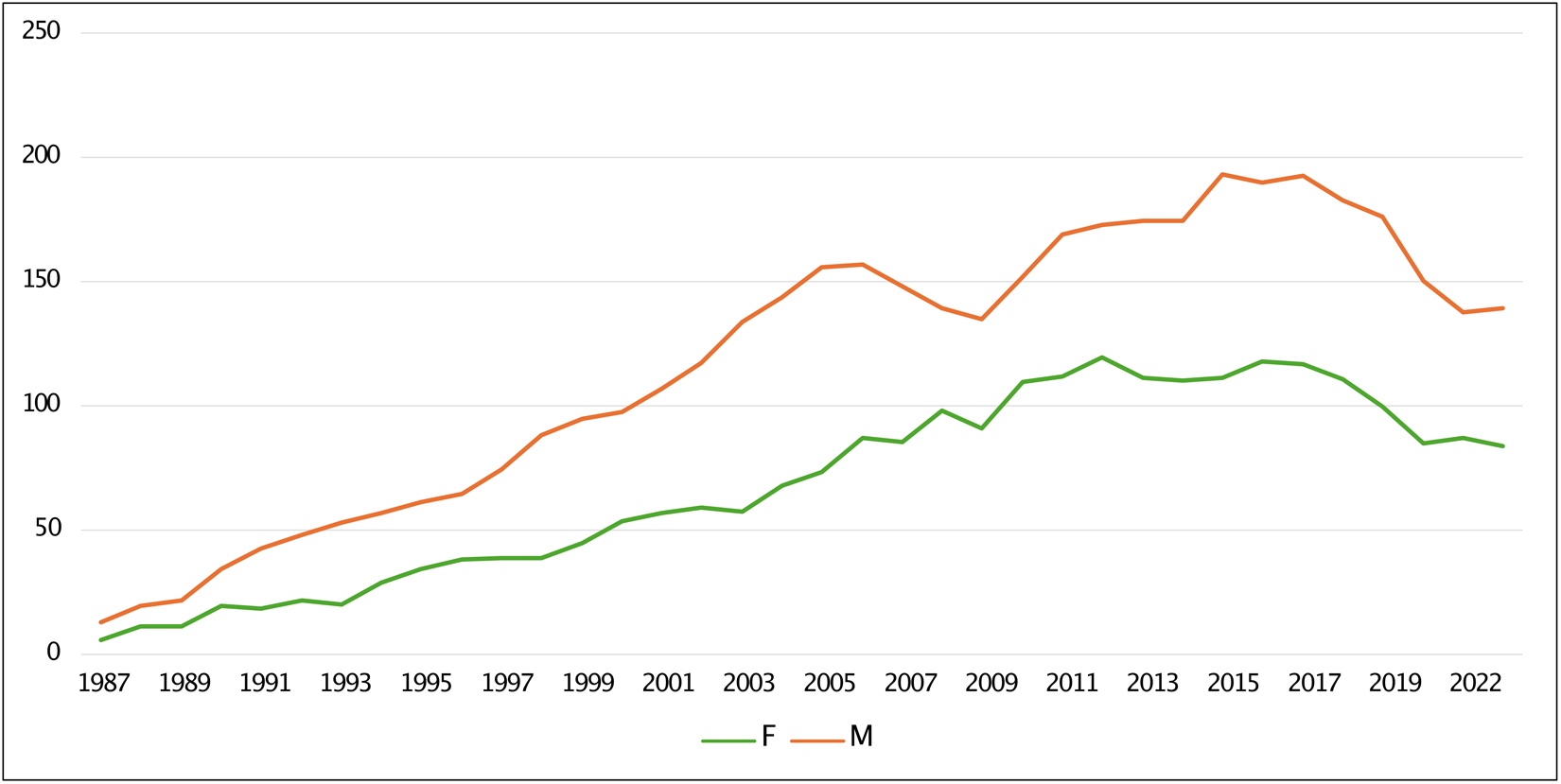

An analysis of all contributors to the memoirs of Guatemala’s annual archaeology symposium shows that men have published more than women, regardless of nationality (63.34% men; 36.66% women; N = 6,864; χ2 = 60.653; df = 35; p = 0.005; Figure 3). A moving average for the dataset reveals the trends more clearly, indicating an increase in overall participation over time, which began to decline in 2017 (Figure 4). The broadest gender gaps appear from 2003 to 2005 and from 2015 to 2018. Notably, there was a drop in participation for both men and women in 2021, likely attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic. While the gender gap did not widen in 2021 and 2022, it began to expand again in 2023. It is worth noting that the symposium was held online in 2021 and 2022, which potentially made remote attendance more accessible. We believe some of these trends are tied to professional roles, as discussed below.

Figure 3. Gendered publication trends in the memoirs of the Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 1987–2023 (N = 6,864).

Figure 4. Moving average showing gendered publication trends in the memoirs of the Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 1987–2023 (N = 6,864).

According to data on lead authors from 2010 to 2021, Guatemalan archaeologists comprise the largest group of contributors, followed by researchers from the United States, Mexico, Japan, and Europe (Table 1). Within the European cohort, scholars from Slovakia, France, Spain, and Poland are known to lead research projects in Guatemala. In Table 1, the “other” category for symposium proceedings comprises countries with fewer than 11 authors, including Russia, Canada, Honduras, Argentina, Portugal, and the Netherlands. An interesting pattern is observed when looking at the work presented by Central American and Mexican scholars, who generally present findings from their own countries rather than from Guatemala. This suggests that the symposium attracts a diverse set of participants who wish to share broader regional findings.

Table 1. Gender and Country of Academic Affiliation of First Authors in the Analyzed Publication Venues.

An examination of the lead authors’ gender, regardless of nationality, reveals that men represent 60.02% and women 39.98% of the total sample (N = 1,018; χ2 = 50.824; df = 19; p = < 0.001). To assess the strength of the association between gender and country of academic affiliation, we performed a Cramer’s V test. The V value ranges between 0 and 1, and a value closer to 0 shows a weak association between variables. A Cramer’s V value of 0.223 indicates a weak-to-moderate association between gender and country of academic affiliation for lead authors, suggesting that gender imbalances are not strongly tied to the country of academic affiliation.

Interestingly, men generally publish at higher rates, even during periods when the overall number of Guatemalan female professionals was higher (1980–1984; 2000–2004). A revealing pattern emerges when comparing lead authorship and degree completion at Guatemalan universities. In years with notable gender gaps in symposium proceedings publications, specifically 2015 and 2018, a higher percentage of female lead authors had completed their licenciatura degrees than their male counterparts (2015: 93.9% for women vs. 84.38% for men; 2018: 93.3% for women vs. 88.46% for men).

While speculative, several possible explanations may account for this trend. One possibility is that men take over lead field roles more frequently, which entails preparing technical reports that can later be adapted into symposium papers and other types of publication. This pattern may thus reflect gendered differences in occupational roles or access to research opportunities. Alternatively, men might be more likely to pursue research projects earlier in their academic careers. Lastly, gendered differences in life-stage responsibilities, such as women having children early in their careers, may temporarily limit their participation in fieldwork and affect authorship practices.

Overall, these data point to a gender imbalance in the dissemination of scholarly knowledge at the annual archaeology symposium. Data also reveal a robust community of Guatemalan professionals and students who are actively engaged in archaeology and have a strong inclination to disseminate their work. The presence of foreign presenters points to an international commitment to collaboration and knowledge-sharing, which enriches the discipline by introducing diverse perspectives and methodologies. Consequently, the symposium serves as an essential forum for fostering dialogue between local researchers and a more global archaeological community, ultimately strengthening the field’s collective understanding of Mesoamerican heritage. To provide a broader context for authorship practices by Guatemalan archaeologists, we now describe trends in two international journals.

Publication Trends in International Venues: Latin American Antiquity and Estudios de Cultura Maya

In this section, we first present an overview of general publication trends in both international journals, followed by results focused on Guatemalan archaeologists. An analysis of all contributors to research papers and reports in Latin American Antiquity between 2013 and 2022 shows that the majority were men (58.04% men vs. 41.96% women; N = 1,182; χ2 = 55.982; df = 37; p = 0.023). A similar pattern emerges when examining only the first authors, with 53.97% men and 46.03% women (Table 1; N = 378). The majority of overall contributors and lead authors to Latin American Antiquity during the examined time frame were affiliated with academic institutions in the United States, Argentina, Chile, and Mexico. Although men were generally overrepresented, Argentina, contributing the second-largest number of authors, stands out for its small gender gap, featuring more female first authors and an almost equal number of male and female overall contributors. Guatemala does not appear as a separate category in Table 1 for Latin American Antiquity because there was only one female lead author from this country during the examined period. This case was therefore included in the “other” category, which groups countries with fewer than five authors for this journal, and includes Australia, Uruguay, Panama, Switzerland, Portugal, and Belgium, among others.

Notably, Latin American Antiquity exhibited a relatively narrow gender gap in lead authorship among the analyzed publication venues (N = 378; χ2 = 31.750; df = 25; p = 0.165). A Cramer’s V of 0.290 indicates only a weak-to-moderate association between gender and country of academic affiliation, suggesting that these patterns are not strongly driven by national context. It is important to note that Latin American Antiquity is a hybrid journal, where open-access fees may be waived through institutional agreements. For first authors not covered by such agreements, article processing charges vary. As of July 2025, members of the Society for American Archaeology (SAA) paid US$1,000, and nonmembers paid US$3,550 (Cambridge University Press 2025a, 2025b) for open–access publishing.

Within Estudios de Cultura Maya, an analysis of all contributors between 2013 and 2022 shows that men comprised the majority (55.41% men and 44.59% women; N = 314; χ2 = 26.407; df = 16; p = 0.049). A comparable pattern is observed among first authors, with 56.36% men and 43.64% women, although the gender gap is relatively narrow (N = 165; χ2 = 16.078; df = 13; p = 0.245). Most lead and secondary authors were affiliated with Mexican academic institutions, an outcome that is not unexpected, given the journal’s origin. Contributors from the United States, Guatemala, and France followed in frequency (Table 1). A Cramer’s V of 0.312 for lead authors suggests a moderate association between gender and country of affiliation. This Cramer’s V figure is higher than that observed for Latin American Antiquity and the memoirs of the Guatemalan symposium, suggesting that patterns of authorship in Estudios de Cultura Maya may be more strongly influenced by institutional contexts.

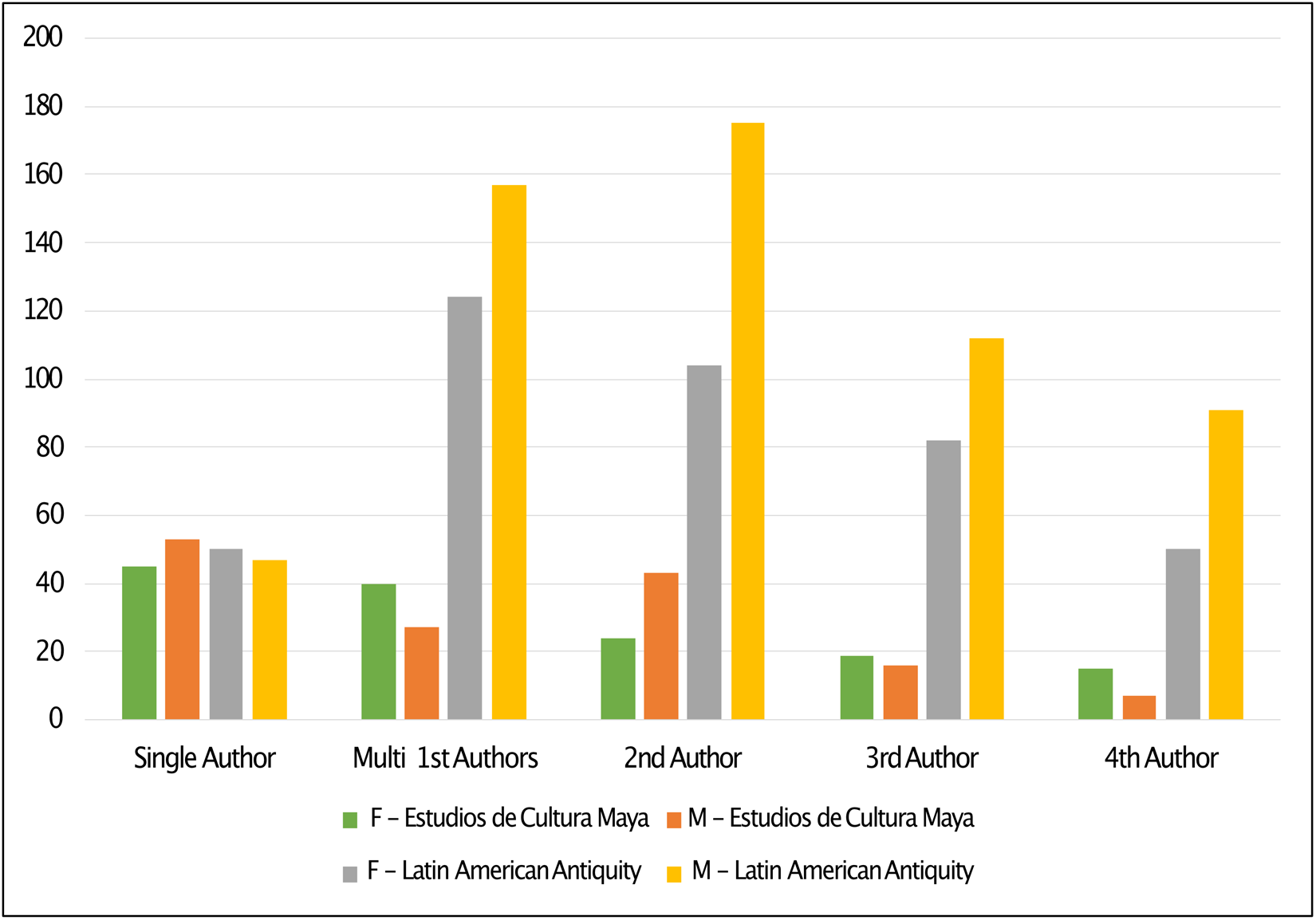

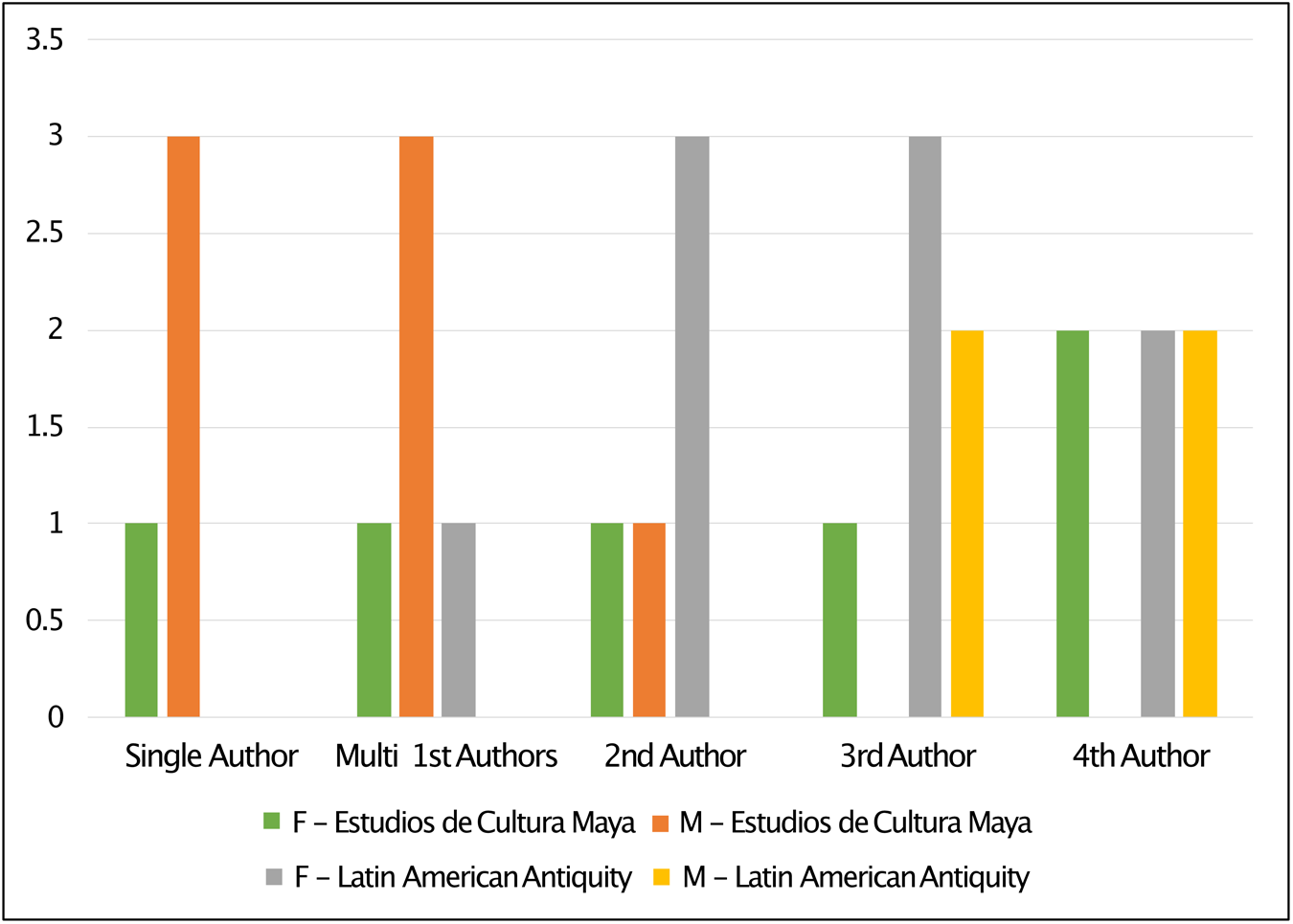

When examining authorship positions, men led a greater number of papers in Estudios de Cultura Maya as sole authors (Figure 5). Women, by comparison, were more commonly first authors on multiauthored publications and appeared more frequently as third and fourth authors in collaborative works. In contrast, in Latin American Antiquity, women authored more papers as sole authors, but the gender gap widened in collaborative works. This suggests that women were more visible as primary contributors in Latin American Antiquity during the examined time frame. It is important to note that first or sole authorship typically carries greater professional weight in academic hiring and promotion, making these trends meaningful for career advancement.

Figure 5. Authorship position by gender in Estudios de Cultura Maya and Latin American Antiquity, 2013–2022 (N = 1,281).

The authorship positions of individuals affiliated with Guatemalan academic institutions reveal that single-authored publications were limited to Estudios de Cultura Maya, and most of these were authored by men (Figure 6). Women appeared in multiauthored publications in both journals and more frequently contributed as second and third authors in Latin American Antiquity. The gender gap narrows in the fourth authorship position in Latin American Antiquity, and, notably, only women appear in that position in Estudios de Cultura Maya.

Figure 6. Counts of authorship position by gender for authors affiliated with Guatemalan academic institutions in Estudios de Cultura Maya and Latin American Antiquity, 2013–2022 (N = 27).

Several factors may account for the more substantial presence of Guatemalan authors in Estudios de Cultura Maya. First, authors who lack institutional open-access agreements must pay fees to publish open-access in Latin American Antiquity, whereas Estudios de Cultura Maya is entirely in Spanish and open-access, thereby removing financial and language barriers. Second, many Guatemalan archaeologists do not pursue tenure-track positions, so the prestige of certain international journals may carry less weight in their career trajectories. Finally, a preference for publishing in a regionally specialized journal like Estudios de Cultura Maya could be influential, as it may offer greater accessibility to local audiences and a focused scholarly community. Overall, the data suggest variations in gender gaps and multiple factors influencing international authorship patterns. To contextualize these publication trends further, we turn to the final part of our results and present the survey findings.

Exploratory Survey: Occupations and Perceptions of Inequalities

Of the total respondents of the exploratory survey, 61% were women and 39% were men, with the majority falling between 36 and 45 years old (N = 103; Table 2). Most respondents were licenciatura candidates (31.4%), who constitute a large number of the active workforce in Guatemalan archaeology as researchers and employees. Their higher response rate reflects both their prominent role in the field and their willingness to participate voluntarily in the survey. Respondents also included those holding master’s degrees (28.4%), licenciatura degrees (20.6%), and PhDs (6.9%). In terms of ethnicity, a significant majority (82.36%) identified as non-Indigenous, 5.88% as Maya, and 11.76% as other (e.g., Guatemalan, Ladino, or Hispanic), indicating an ethnic gap among respondents. Although we lack comparable data on the ethnicity of professional graduates, this distribution aligns with broader observations of the archaeological community, which has historically been dominated by non-Indigenous archaeologists.

Table 2. Age Range and Academic Degrees of Survey Respondents (N = 103).

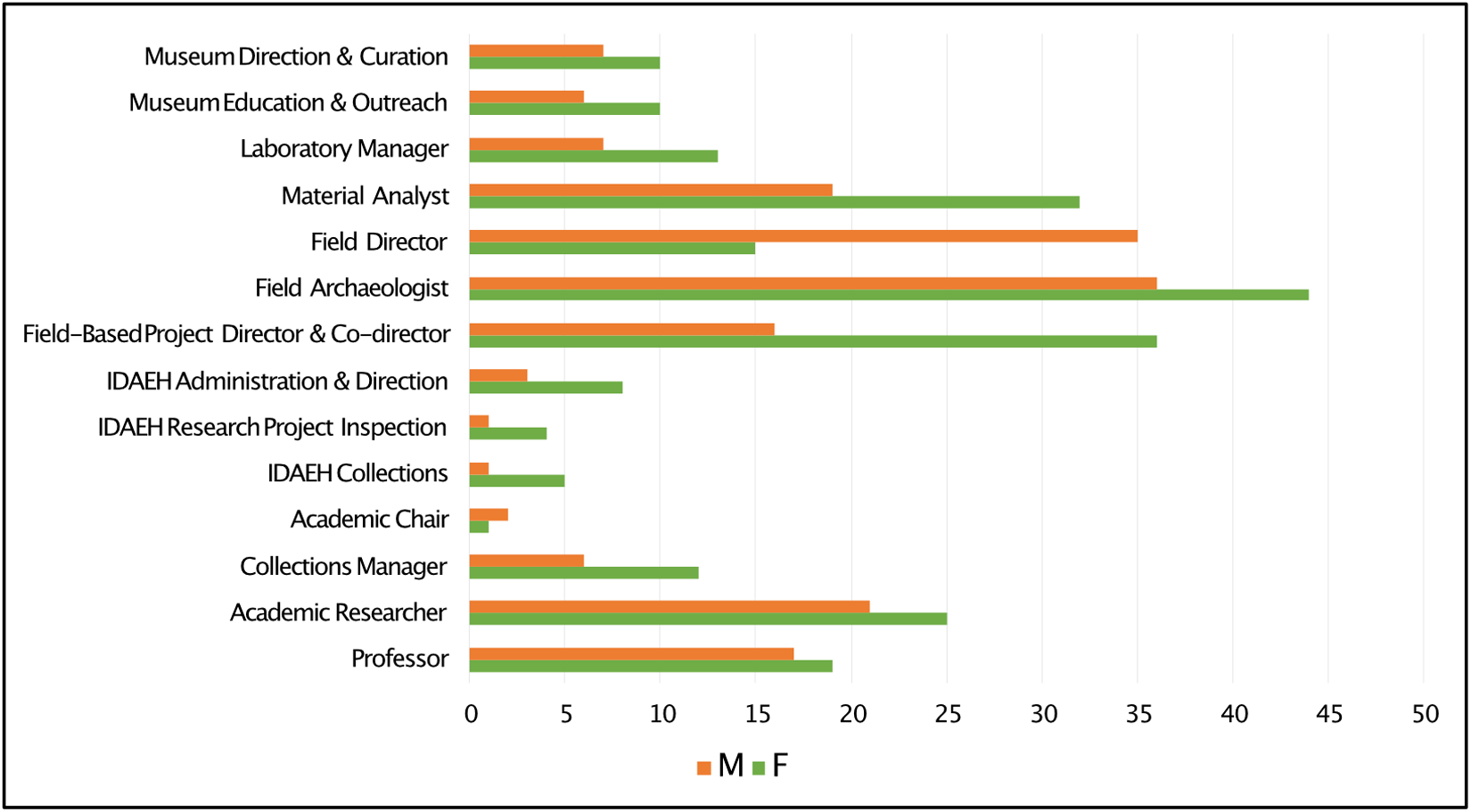

The occupation data reveal that more men have served as academic chairs and field directors, whereas surveyed women reported holding a broader array of professional roles, including material analysts, laboratory managers, research project directors, and museum educators (Figure 7). The narrowest gender gap is observed in academic positions, where professors and researchers exhibit a relatively balanced gendered distribution. Notably, at the Instituto de Antropología e Historia (IDAEH)—the government agency that regulates archaeological research—women have held a more diverse set of positions, including in project inspection, administration, and directorship. While the data may be biased, as more women responded to the survey, these findings suggest variations in occupational roles by gender within Guatemalan archaeology.

Figure 7. Professional positions held by survey respondents throughout their professional trajectories (N = 394).

It is also worth noting that women have held prominent public positions, including director of the National Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, head of the Department of Prehispanic Monuments at IDAEH, and, more recently, minister of culture and sports (Vásquez Reference Vásquez2024). The data thus suggest that while men more commonly occupy leadership positions in fieldwork, women have achieved leadership in other domains. This distinction may help explain some of the disparities observed in publication patterns, as public government positions and administrative roles are not typically focused on academic research. However, concrete data on the male–female ratio in professional roles is needed to confirm this interpretation, which at present remains speculative.

The survey also inquired about respondents’ perceptions of gender gaps in leadership positions, salaries, and publications. Nearly half (49%) perceived a gender gap in leadership roles, and 39.80% believed a salary gap might exist. However, some participants attributed pay differences to factors other than gender, such as academic qualifications, and noted that archaeology appears relatively balanced compared with other professions. Given global trends in gender-based salary disparities, where women are often remunerated less than men for equivalent work (Penner et al. Reference Penner, Petersen, Hermansen, Rainey, Boza, Elvira and Godechot2022), it would not be surprising to find similar patterns in Guatemala, although we currently lack the data to assess this possibility.

Regarding publication opportunities, a slight majority (51.96%) did not perceive gender disparities, despite our research suggesting otherwise. When asked to elaborate on perceptions of inequalities, respondents offered mixed perspectives. Some described sexist experiences during fieldwork, including harassment, resistance from workers who refused to follow orders from women, and inappropriate jokes. Others, however, pointed to strong female leadership and supportive professional development from supervisors. Overall, while the survey was an exploratory effort, the findings highlight the complex nature of gender dynamics in Guatemalan archaeology, on which we further elaborate in the following section.

Discussion and Recommendations

Our findings reveal a gender gap in the dissemination of archaeological knowledge in national and international scholarly venues for Guatemalan archaeologists. This disparity likely stems from a combination of factors, including differences in occupational roles, research opportunities, institutional barriers, and caretaking responsibilities. Men’s greater representation in fieldwork leadership positions likely results in more frequent opportunities for publication. While many Guatemalan scholars direct and contribute to research, most large-scale projects funded by international institutions have been historically led by foreign men. Since Guatemalan codirectorship is required for foreign-led projects, these roles are a crucial means for local scholars to access publishing opportunities. Furthermore, authorship in the proceedings of the Guatemalan symposium is often extended to project members, increasing the likelihood of publication for those engaged in fieldwork.

Patterns in the examined international journals suggest that fees and funding opportunities play a relevant role in publication trends. While the prestige of international journals like Latin American Antiquity may be appealing, fully open-access journals in Spanish, such as Estudios de Cultura Maya, may be more accessible for scholars without institutional subsidies, as reflected in the higher number of publications by Guatemalan authors. Although some open-access publication costs for Latin American Antiquity are subsidized for SAA members, many Guatemalan researchers lack membership and therefore may not benefit from this support, making local fully open-access venues in Spanish a more feasible option. Additionally, in much of Latin America, the absence of formal tenure-track systems can reduce the incentives associated with publishing in high-prestige journals, making the cost for open-access publication a more decisive factor. While USAC has a system similar to tenure, known as titularidad, opportunities for such positions remain limited. At the same time, the authorship trends observed in Latin American Antiquity, where women are more visible in single-authored publications, are encouraging for scholars across Latin America.

We therefore believe that for Guatemalan authors financial barriers are likely more influential than the journal’s specialized focus, and that some may favor local publication venues with broader regional visibility. This is relevant, as over time this dynamic may shape which research reaches global audiences and which remains regionally confined. It is also worth noting that academic affiliation, although a useful indicator, does not always accurately reflect a researcher’s nationality. Guatemalan researchers who pursue graduate training abroad often affiliate with foreign universities, which can sometimes lead to a “brain drain” scenario if they face challenges in returning home owing to limited job opportunities. Consequently, addressing language barriers, publication costs, and inadequate institutional support is pivotal for fostering more equitable practices.

A closer examination of professional roles provides further insight into why women may publish less frequently. Traditional gender norms in Latin America, where women are often the primary caregivers, can influence career choices, leading some to pursue roles that offer greater stability and less travel. Although many women in Guatemalan archaeology direct field-based projects, they also hold administrative, collections management, and public government positions. While these roles are essential to the discipline, they often afford less time for research and writing, and therefore fewer opportunities to publish. Nevertheless, such positions remain important avenues through which women exercise leadership and contribute meaningfully beyond academic publications. It is essential to highlight, however, that women’s presence in these roles does not necessarily reflect gender equity. Future detailed research on occupational trends by gender would be valuable for identifying patterns of inequality more clearly and supporting the development of broader strategies.

It is also important to recognize that gendered divisions of labor are historically contingent and subject to change. Historically, men have taken on higher-profile fieldwork and academic leadership roles (Chase Reference Chase2021; Gero Reference Gero1994), but recent studies show a decline in rigid gender-based labor divisions (Chen and Marwick Reference Chen and Marwick2023; Heath-Stout and Jalbert Reference Heath-Stout and Jalbert2023). Consistent with these findings, both our data and other Latin American research confirm that men and women now participate fully in fieldwork (Cordero Reference Cordero2018; Ribeiro et al. Reference Ribeiro, Da Silva Formado, Schimidt and Passos2017; Tavera Medina Reference Tavera Medina2019). Additionally, although the COVID-19 pandemic generally increased caregiving responsibilities for women (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Mennerat, Lukas, Dugdale and Culina2023), its shift to remote conferences and virtual collaborations may have facilitated continued research engagement for those with field-based roles. Further research on postpandemic trends in lead authorship will help clarify this matter.

Lastly, our findings highlight some limitations of the “leaky pipeline” model, especially in contexts outside the Global North. The model emphasizes the gradual loss of women and other marginalized groups from academic trajectories, which often results in their underrepresentation in leadership roles (Avolio et al. Reference Avolio, Chávez and Vílchez-Román2020; Overholtzer and Jalbert Reference Overholtzer and Jalbert2021). However, it tends to overlook complex local dynamics, such as those seen in our case study, and fails to account for the cultural and historical forces that shape academic communities. In Latin America, for example, colonial legacies, postcolonial structures, and gender roles significantly influence professional advancement. Academic inequality is thus experienced differently across regions and is shaped by specific historical and structural conditions. Our case study demonstrates that the challenge is not only one of retaining women and minorities in the field but also of addressing disparities in research opportunities and academic visibility.

The distinction between who creates and who disseminates knowledge is fundamental to understanding how inequalities are reproduced within academic circles. This distinction is another aspect that is often obscured by the leaky pipeline model. Although both roles are essential to the advancement of knowledge, they do not always receive the same recognition and visibility. In Latin America, for example, those who create knowledge, such as researchers who conduct fieldwork or analyze data, are often local scholars from underrepresented backgrounds. The knowledge they produce may be interpreted and disseminated primarily by individuals in more privileged or institutionally visible positions, often located in academic centers of the Global North. This disconnection not only renders invisible the intellectual labor of those at the foundation of the production process but also perpetuates an epistemological hierarchy in which certain voices are granted more authority than others. Understanding this distinction allows us to question the mechanisms through which knowledge is produced and to reconsider the dynamics of collaboration.

Based on our findings, we propose three recommendations for fostering a more inclusive archaeological community. Our first recommendation involves institutional support by academic centers for education and publishing opportunities. Given Guatemala’s colonial history and cultural diversity, the participation of local researchers of diverse backgrounds is vital to ensure that scholarship reflects a wide range of experiences. While historical factors have contributed to unequal participation in science, universities can help address this gap by offering scholarships and targeted programs to support students from underrepresented backgrounds.

Access to higher education in archaeology remains highly centralized in Guatemala City, where only USAC and UVG offer licenciatura degrees, although CUDEP in northern Guatemala partially mitigates this centralization. Although USAC tuition is relatively low (approximately US$20 annually), room and board costs pose a financial challenge. In contrast, UVG’s higher tuition restricts accessibility, although its scholarship programs mark an important step toward inclusivity. By reducing financial barriers and promoting equitable access to training opportunities, such initiatives can help diversify the field and ensure a broader range of perspectives in archaeological research.

Academic institutions and research centers should also consider implementing mechanisms to support local scholars in the publishing process. This could include creating internal funds to cover article processing charges for international journals, negotiating fee waivers with publishers, or offering editorial and peer-review workshops, particularly for early-career researchers and those writing in a second language. Such initiatives would help mitigate some of the barriers that often hinder publication in high-impact journals. In a context where tenure opportunities and institutional funding are limited, providing concrete financial and editorial support would enhance scholarly visibility.

Second, grassroots organizations that promote inclusivity can play a crucial role in driving change. This strategy may face challenges related to funding and implementation if community members do not perceive and acknowledge the existence of gender inequalities, as our study has shown. Our survey also points to gender-based discrimination suffered by some respondents, which can discourage women from pursuing leadership or research-intensive positions. In other contexts, groups such as Red de Investigadoras, Proyecto ArqueologAs/Herstory, Trowelblazers, and Paye ta Truelle have successfully used social media to raise awareness about sexism, highlight the contributions of female archaeologists, and advocate for gender equity within the discipline. A comparable initiative in Guatemala would provide a valuable platform to amplify marginalized voices and strengthen community support.

In 2021, we organized the First Conference on Diversity in Guatemalan Archaeology at UVG. Rather than relying on institutional hierarchies or international recognition, the speakers were women perceived as influential within the local archaeological community, some of whom have paved the way for future generations. The conference created a much-needed space for dialogue, visibility, and recognition, grounded in local values and experiences rather than external validation. Comparable grassroots initiatives would provide valuable platforms for emerging voices and the commemoration of local expertise that may go unacknowledged in international outlets.

Lastly, greater attention to gender equity by project directors could help ensure equal opportunities for professional development within archaeological projects. Research projects could incorporate explicit guidelines to address harassment and offer practical support for caregivers, such as childcare options during fieldwork. Voluntarily adopting practices that promote more equitable participation and leadership would further enhance inclusivity. These strategies would foster a more supportive environment for all scholars, particularly women. Addressing these three areas—institutional support, grassroots advocacy, and project guidelines—would provide substantial steps toward a more inclusive archaeological community.

Conclusions

This study aimed to provide initial insights into the current state of inequality in Guatemalan archaeology and revealed disparities related to gender and nationality in academic publications. Although the overall number of local professional men and women is relatively balanced, Guatemalan men lead the dissemination of archaeological knowledge. Our findings suggest that gender imbalances cannot be fully attributed to researchers’ countries of academic affiliation. Instead, multiple interwoven factors, including institutional barriers, socioeconomic limitations, and traditional gender norms, help perpetuate the gender gap in this specific context.

Variations in research opportunities and occupational roles, particularly the tendency for men to hold leadership positions in fieldwork, likely contribute to the disparities observed in publication trends. However, women have increasingly gained visibility and influence in other areas of the discipline through leadership roles in administrative and public governmental settings. These contributions demonstrate that leadership and scholarly impact extend beyond authorship alone. Nevertheless, women occupying a wide range of professional positions often face additional challenges rooted in sexism and societal expectations associated with traditional gender norms. While women’s visibility in leadership roles marks an important step, it does not ensure gender equity, as systemic barriers to balanced participation persist.

Although centered on Guatemala, these findings contribute to a broader understanding of academic inequality by showing how structural, social, and cultural factors shape scholarly visibility. The absence of subsidized publication fees and variable funding opportunities in Latin America appear to elevate the importance of accessibility and cost over journal prestige or specialization. Based on our findings, the following areas are key to fostering a more inclusive and representative archaeological discipline: (1) institutional strategies to provide education opportunities for underrepresented groups and publication support for scholars; (2) grassroots efforts promoting diversity and raising awareness on inequalities; and (3) gender equity guidelines in archaeological projects, including strategies to address harassment and practical support for caregivers. We hope these recommendations are helpful and encourage tangible actions toward a more inclusive archaeological community in Guatemala and other contexts. Addressing these issues fosters dialogue, informs policy and practice, and brings diverse perspectives to the study of the Mesoamerican past.

Acknowledgments

This research was undertaken with the academic support of the Centro de Investigaciones Arqueológicas y Antropológicas de la Universidad del Valle de Guatemala. No research permits were required for this study. We thank the Guatemalan archaeologists who voluntarily completed the survey, as well as Tomás Barrientos, Amparo Herrera, and Edgar Carpio Rezzio for providing the alumni data used in this study. We are also grateful to Samantha Fladd and Sarah Kurnick for inviting us to contribute to the SAA annual meeting session in Portland that led to this themed issue, and to the four anonymous reviewers whose detailed comments improved the clarity of this article. We also thank Camilo Luin and the Museo Popol Vuh for granting us access to the symposium volumes. Our appreciation also goes to Hiroaki Yagi and Tatsuya Murakami for their assistance in identifying some names, and to Deimy Ventura, Jason Nesbitt, and Marcello Canuto for their comments on an earlier version of this research.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant funding from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are available in the Digital Archaeological Record (tDAR), at https://core.tdar.org/document/504368/data-publication-trends-in-guatemalan-archaeology (Ponce Reference Ponce2025).

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.