I. Introduction

The international community faces a range of sustainability challenges whose causes and effects do not stop at national borders. A particular challenge is companies’ negative impacts on human rights and the environment, such as forced labour in mining and production or agrochemicals degrading biodiversity.Footnote 1 These impacts are of transnational concern because, in the context of globalisation, companies can be involved in adverse impacts through their broader business operations, including foreign-based subsidiaries and global value chains. Impairment of human rights and environmental standards continues to occur,Footnote 2 notwithstanding efforts to conclude an international treatyFootnote 3 and authoritative frameworks on responsible business conduct,Footnote 4 which are widely recognisedFootnote 5 but remain poorly implemented in practice.Footnote 6

While multilateral approaches progress slowly, European lawmakers pursue unilateral action, that is, ‘an individualistic approach to foreign affairs’.Footnote 7 In July 2024, the Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence (CSDDD or the Directive) entered into force in the European Union (EU).Footnote 8 Once transposed, it will require large companies active on the common market to manage adverse human rights and environmental impacts through due diligence processes.Footnote 9 The CSDDD follows in the footsteps of several European countries that have already adopted national due diligence laws, including France with its Duty of Vigilance Law,Footnote 10 Germany with its LkSG,Footnote 11 and Norway with its Norwegian Transparency Act.Footnote 12

What renders these laws an example of unilateralism is their regulatory thrust. While differing in several respects,Footnote 13 the French, German and Norwegian legislation share the purpose of addressing adverse human rights or environmental impacts within and beyond the lawmakers’ own territory and jurisdiction.Footnote 14 Similarly, the CSDDD aims to ensure companies active in the internal market contribute to sustainable development not only in the EU but also in third countries, thereby targeting challenges of ‘transnational dimension’.Footnote 15 To rise to this challenge, due diligence laws impose requirements on companies that have both a transcorporate and a transnational dimension: transcorporate because the obligations reach beyond the boundaries of a company’s own legal entity, and transnational given that corporate ownership ties and value chains regularly extend across multiple jurisdictions. Through these dimensions, due diligence laws like the CSDDD shape the complex dynamics of the global economy.

While aiming to strengthen respect for human rights and environmental standards, due diligence laws carry the risk of unintended consequences in third countries. In particular, they could incentivise companies within their scope to unduly shift responsibility to their business partners along global value chains. Furthermore, relevant legislation could have socioeconomic repercussions for stakeholders due to widespread withdrawals from markets that companies deem too ‘risky’ from a compliance perspective.

Given these risks, it is not surprising that European legislation with extraterritorial implications is increasingly controversial. One example is the political turmoil surrounding the extraterritorial effects of the EU’s Deforestation Regulation, which defines specific due diligence requirements for traders of selected crops in an effort to curb deforestation.Footnote 16 Criticism from Indonesia, the United States (US) and Brazil led to a one-year postponement in 2024.Footnote 17 Similarly, the CSDDD is facing political headwinds. Qatar has criticised the Directive and suggested that it may limit the supply of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to the EU if the directive is not significantly changed.Footnote 18 In the US, business associations and state officials have claimed that the Directive would encroach on US sovereignty.Footnote 19 In March 2025, US Senator Bill Hagerty even presented a proposal for a blocking statute prohibiting entities from complying with the CSDDD.Footnote 20 These contentions raise the question of what boundaries the international legal order defines for unilateral legislation addressing global sustainability challenges.Footnote 21

The relevance of this question is enhanced by the EU political context, given that the EU is currently amending its sustainability legislation. In February 2025, the European Commission published Omnibus proposals to simplify corporate sustainability requirements, including the CSDDD.Footnote 22 EU lawmakers have already agreed to postpone the CSDDD’s transposition and application deadlines by one year,Footnote 23 while further substantial amendments are underway. While the process is primarily concerned with regulatory simplification and EU competitiveness, there are also indications that the EU intends to mitigate extraterritorial implications.Footnote 24

This article assesses the CSDDD as an example of due diligence legislation against the international law of jurisdiction. It analyses the regulatory approach underlying the Directive and other European due diligence laws, and revisits the question of whether, and to what extent, states are permitted under international law to adopt due diligence legislation with significant extraterritorial implications. While the focus is on the CSDDD, whose EU-wide scope is likely to produce the most substantial transnational effects, the assessment also informs discussions on national due diligence laws. The inquiry delves into the principles of jurisdiction to determine the boundaries of unilateral lawmaking, without assessing the Directive’s compliance with international trade law. It argues that unilateral due diligence laws are a lawful means to address transnational sustainability challenges, while recommending adherence to established reasonableness criteria. The article further acknowledges that the principles of jurisdiction ‘carry imperial overtones’ and are increasingly out of touch with the realities of economic globalisation.Footnote 25 It is argued that, although the CSDDD meets the demands of public international law, EU lawmakers ought to be mindful of unintended consequences.

The article proceeds as follows. Section 2 discusses the regulatory approach of the CSDDD and its expected extraterritorial implications. Section 3 defines the lawful scope of prescriptive jurisdiction under international law and applies these principles to the CSDDD, before Section 4 discusses reasonableness considerations as well as structural limitations underlying the law of jurisdiction. Section 5 concludes.

II. The CSDDD and its Extraterritorial Dimension

A. Regulatory Approach

In the context of globalization, states claim an interest and increasingly act to govern circumstances beyond their own borders, including the conduct of companies abroad.Footnote 26 Accordingly, unilateral business law with extraterritorial reach is not unprecedented.Footnote 27 The CSDDD essentially requires entities to undertake ‘risk-based human rights and environmental due diligence’ (HREDD), also referred to as ‘corporate sustainability due diligence’.Footnote 28 HREDD describes a management process to identify and address negative impacts on human rights and the environment. The concept evolved in the work of the United Nations (UN), most notably the 2011 UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), which first defined human rights due diligence processes.Footnote 29 Since then, many international organizations have endorsed the approach,Footnote 30 including the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which has published a plethora of guidance, including the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct (OECD Guidelines).Footnote 31 The OECD has coined the term ‘risk-based due diligence’, building on the UNGPs but extending the scope to adverse impacts on sustainability matters more broadly.Footnote 32 The CSDDD explicitly draws upon the frameworks of the UN and OECD, transposing their recommendations from soft law to hard law.Footnote 33

HREDD processes are designed to address sustainability challenges in the globalised economy. As such, they purposely reach beyond national borders. This transnational dimension results from the underlying approach, which is itself a response to economic globalization.Footnote 34 HREDD targets the adverse impacts that a company causes or contributes to through its own (global) operations as well as the impacts caused by other actors to whom the company is directly linked through its operations, products or services.Footnote 35 For example, a company may instruct its foreign subsidiary to implement the parent’s human rights policy and risk assessment processes, or apply its leverage to ensure that an indirect supplier adequately addresses a severe human rights risk. Requiring the management of adverse impacts beyond the boundaries of the own legal entity, HREDD is a transcorporate exercise. In crossing corporate boundaries, it also traverses national frontiers. This is due to the fragmentation of production processes and the diversification of corporate control, which characterise economic globalization.Footnote 36 Where a company’s operations and business relationships go global, HREDD follows suit, rendering the process a transnational exercise. Due diligence laws like the CSDDD incorporate this transnational dimension of HREDD processes.

The regulatory approach described may be one reason why the CSDDD has been in the crossfire of the political debate in Brussels throughout its drafting and beyond. The lengthy and turbulent legislative process concluded with the entry into force in July 2024.Footnote 37 Just eight months later, in February 2025, the CSDDD became the subject of a simplification initiative by the European Commission, which aims to increase EU competitiveness by streamlining sustainability requirements.Footnote 38 The Commission cites, inter alia, concerns that HREDD would impose a ‘significant regulatory burden’ for companies within scope, especially where value chains are multi-tiered and geographically dispersed.Footnote 39 In addition, the Commission argues that small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), though not in scope of the Directive, may still experience ‘unwanted trickle-down effects’.Footnote 40 Thus, the simplification initiative rather reflects concerns about the transcorporate dimension of the CSDDD than its transnational implications.

B. Key Requirements

The CSDDD applies to very large companies with substantial connections to the EU common market.Footnote 41 This includes EU-based companies and parent companies of large groups meeting global employee and turnover thresholds,Footnote 42 as well as companies with franchising or licensing arrangements in the EU above specified levels.Footnote 43 The Directive further extends to third country companies meeting these thresholds through their EU operations.Footnote 44 Companies that fall within this personal scope must comply with due diligence requirements, which target adverse human rights impacts and adverse environmental impacts.Footnote 45 To substantiate these terms, reference is made to specific rights and prohibitions, human rights instruments and obligations under international environmental law.Footnote 46 The EU legislator hence draws on sources of international law to define the negative externalities of companies.

The Directive establishes interconnected due diligence obligations structured around three core elements:Footnote 47 governance (integrating due diligence into policies and systems, as well as stakeholder engagement),Footnote 48 risk management (identification, assessment, prevention, mitigation and remediation of adverse impacts),Footnote 49 and accountability (notification and grievance mechanisms, monitoring and public reporting).Footnote 50 While companies bear these obligations individually, they can engage in collective action for the purpose of compliance by participating in appropriate industry and multi-stakeholder initiatives.Footnote 51

Most of the due diligence requirements in the CSDDD are obligations of means. Thus, companies must take ‘appropriate measures’ to comply with the obligations rather than guaranteeing results.Footnote 52 As regards the management of potential or actual adverse impacts, the CSDDD provides a list of ‘appropriate measures’.Footnote 53 For instance, companies shall adopt action plans, obtain contractual assurances and make necessary investments. If these measures remain insufficient to address an impact on a business partner, companies must consider disengagement, such as suspending the business relationship.Footnote 54

The HREDD requirements cover not only a company’s own operations but, importantly for this article, also those of subsidiaries and business partners in the ‘chain of activities’.Footnote 55 A chain of activities covers the operations of upstream business partners involved in the production of goods or the provision of services of the company, as well as immediate downstream business partners concerned with the distribution, transport and storage of products.Footnote 56 Regarding the enforcement of the HREDD provisions, the CSDDD combines public enforcement through national supervisory authorities with civil liability mechanisms, allowing affected individuals to hold companies accountable in court.Footnote 57

C. The Directive’s Extraterritorial Implications

Due diligence laws like the CSDDD have direct legal implications, indirect legal effects, and broader socioeconomic repercussions extraterritorially. The direct legal implications concern all companies in scope. For example, the French Duty of Vigilance Law applies to large companies registered in France.Footnote 58 However, the scope can also extend to foreign entities. The German LkSG applies to large business branches of foreign companies,Footnote 59 whereas the Norwegian Transparency Act captures foreign companies offering goods and services in Norway that are liable for Norwegian taxes.Footnote 60 The CSDDD similarly extends to third-country companies with significant EU operations, primarily assessed by EU turnover.Footnote 61 These must undertake HREDD throughout their operations, whether or not they have an EU subsidiary or business branch.Footnote 62 Thus, the CSDDD imposes direct obligations upon non-EU companies.

Further, due diligence laws have indirect extraterritorial implications. These cascading effects result from the transnational nature of due diligence requirements. French, German and Norwegian due diligence laws, for instance, require companies to undertake HREDD also in relation to foreign-based subsidiaries.Footnote 63 The same applies to the CSDDD, which mandates parent companies to extend their due diligence processes to controlled undertakings over which they exercise control using, for instance, voting rights or board appointments.Footnote 64 Crucially, this applies regardless of where the controlled undertaking is registered. For example, if the Directive applies to a parent company but not to its third-country subsidiary (as it lacks significant EU operations), the parent must cover the subsidiary’s operations ‘as part of its own due diligence obligations’.Footnote 65 The CSDDD thus holds parents responsible for managing their subsidiaries’ human rights and environmental impacts.Footnote 66 In cases of non-compliance, parent companies may face accountability, even where the subsidiary alone caused the relevant harm.Footnote 67

Increased parent accountability could encourage consolidated control over subsidiaries to achieve closer integration (aligned policies, due diligence processes, resource sharing).Footnote 68 Conversely, corporate groups may seek regulatory arbitrage to reduce liability risks by resorting to alternative means of control over affiliates outside of the legal definition.Footnote 69 Either way, the Directive affects all third-country subsidiaries sufficiently controlled by in-scope companies, regardless of diverging requirements at the former’s place of incorporation.

Indirect effects also concern value chain companies of entities required to undertake HREDD, namely those involved in producing their goods or providing their services. Due diligence laws vary in defining which business partners are subject to the HREDD processes of in-scope entities. French and German legislation limit the scope to either ‘established business partners’Footnote 70 or first-tier suppliers, unless the company has substantiated knowledge of negative impacts beyond tier one,Footnote 71 whereas Norwegian law covers relevant suppliers and business partners across the full value chain.Footnote 72 The CSDDD strikes a middle ground covering direct and indirect business partners along companies’ chain of activities, including upstream and specific downstream partners.Footnote 73 Since companies can have hundreds or thousands of suppliers and sub-suppliers, the CSDDD affects a large number of business partners across global value chains.Footnote 74

The cascading effects on value chain companies create risks of unintended consequences, particularly where companies unduly outsource their own responsibilities.Footnote 75 Due diligence laws grant companies discretion in determining appropriate measures to address adverse impacts in business relationships.Footnote 76 The CSDDD, for example, provides a list of measures to choose from.Footnote 77 When exercising this discretion, however, businesses may prioritise cost and risk considerations over the effectiveness of due diligence measures. Take the German LkSG, which led companies to send undifferentiated questionnaires to suppliers and pass legal requirements down the supply chain.Footnote 78 Similar practices were found under the Norwegian Transparency Act.Footnote 79 These examples demonstrate the risk of companies favouring formalistic compliance over effective measures, potentially imposing disproportionate burdens on suppliers.

Certainly, due diligence laws define guardrails to limit companies’ discretion by reference to reasonableness, appropriateness, effectiveness or proportionality.Footnote 80 Similarly, the CSDDD defines appropriate measures as those capable of effectively addressing adverse impacts commensurate to their severity and likelihood, and reasonably available to the company.Footnote 81 These criteria should prevent over-reliance on social audits and contracts, given their well-known limitations.Footnote 82 Furthermore, scholars convincingly argue that these guardrails, in particular the effectiveness criteria, prohibit an undue delegation of due diligence requirements to business partners.Footnote 83 However, the German and Norwegian experience suggests that without dedicated guidance and enforcement, vague concepts like effectiveness, reasonableness and proportionality create a permissive environment for companies to shift responsibility to business partners, particularly where lead companies have economic leverage over their suppliers. These power imbalances may be exploited by demanding unrealistic assurances or imposing unilateral obligations on suppliers.Footnote 84 As such, the CSDDD may have significant extraterritorial implications on businesses that are not only outside the scope of the Directive but also outside of the EU’s jurisdiction.

Aside from direct and indirect legal effects, due diligence laws can have socioeconomic repercussions for stakeholders in third countries.Footnote 85 In particular, HREDD requirements risk company withdrawals from countries with poor human rights and environmental records, harming local businesses, smallholders and communities.Footnote 86 Evidence from national due diligence laws shows that these risks are not merely theoretical. For example, Section 1502 of the United States Dodd-Frank Act establishes transparency obligations to reduce resource-related conflict and human rights abuse in the Great Lakes region in Africa.Footnote 87 Despite positive effects, researchers also observed rising conflict, looting and violence.Footnote 88 In addition, early evidence from the LkSG indicates a change in trading patterns. A 2024 study found the Act coincided with significantly reduced garment imports from Bangladesh and Pakistan, countries with documented human rights and environmental challenges.Footnote 89 It also found that 7 per cent of companies had at least partly withdrawn from countries with weak governance structures.Footnote 90 While the evidence is preliminary, it illustrates the risk of companies withdrawing from emerging and developing markets due to due diligence laws. Due to its geographical scope, the CSDDD poses even greater risks of affecting local economic stability and undermining sustainable development by reducing investment in affected regions.

The Commission considers the CSDDD’s risk of socioeconomic repercussions in third countries as low, emphasising the requirements for in-scope companies to provide support to SMEs in the value chain.Footnote 91 Further, the Directive envisages accompanying measures to facilitate implementation, including capacity building for upstream businesses in third countries.Footnote 92 However, as the applicable provisions are vague, how effective they are at preventing market withdrawals will depend on the EU’s political commitment to taking effective accompanying measures. The legal effects and socioeconomic risks of the CSDDD for third countries raise the question of the boundaries defined by international law for unilateral measures with extraterritorial implications.

III. The Law of Jurisdiction

As a management tool that evolved in international soft law, HREDD does not distinguish between corporate nationalities and state territories. The approach was developed to address adverse impacts in the global economy, distinguishing only between levels of corporate involvement. While international soft law can disregard corporate nationality and territorial links, due diligence legislation like the CSDDD cannot. Where the approach enters the sphere of law, it becomes a legal concept, the regulation of which presupposes jurisdiction, which is (still) determined based on state-centred principles like territoriality and nationality.Footnote 93 Therefore, this section revisits relevant principles of jurisdiction to lay the ground for an assessment of the CSDDD.

Jurisdiction describes the right of a sovereign state to exercise authority.Footnote 94 It is commonly divided into prescriptive, adjudicatory and enforcement jurisdiction.Footnote 95 Prescriptive jurisdiction describes ‘the authority of a state to make law applicable to persons, property, or conduct’.Footnote 96 Adjudicatory jurisdiction, in turn, is ‘the authority of a state to apply law to persons or things, in particular through the processes of its courts or administrative tribunals’,Footnote 97 whereas ‘the authority of a state to exercise its power to compel compliance with law’ is termed enforcement jurisdiction.Footnote 98 Sovereign states can exercise all three forms of jurisdiction within their own territory.Footnote 99 Where state authority touches on transnational or purely extraterritorial circumstances, however, the picture becomes more complicated, not least because there is no consensus on the applicable terminology.Footnote 100

The main doctrine delimiting the exercise of state authority beyond the own borders is the principle of non-intervention.Footnote 101 This provision of customary international law grants sovereign states the right to govern their internal affairs without external interference.Footnote 102 If a state exercises jurisdiction ultra vires, it runs the risk of infringing the principle of non-intervention in relation to another state. Assertions of jurisdiction with extraterritorial implications can therefore lead to legal disputes alongside political backlashes.Footnote 103

There are customary rules that govern the exercise of authority over transnational and extraterritorial affairs. Which rules apply depends on whether a state asserts prescriptive, adjudicatory or enforcement jurisdiction. Whereas a state is only allowed to enforce its laws on the territory of another state if the latter consents,Footnote 104 the international law on prescriptive jurisdiction with extraterritorial implications is more nuanced.Footnote 105 In principle, the adoption of laws requires a ‘genuine connection’ between the legislating state and the subject of regulation.Footnote 106 A genuine connection exists where the assertion of jurisdiction can be based on one or more jurisdictional bases.Footnote 107 Where this condition is met, a state is also permitted to exercise adjudicatory jurisdiction.Footnote 108 As the CSDDD is an assertion of prescriptive jurisdiction, the remainder of this section elaborates on the relevant prerequisites, specifically the principles of territoriality and nationality.Footnote 109

A. The Territoriality Principle

The most important base for prescriptive jurisdiction is the territoriality principle.Footnote 110 This doctrine grants states jurisdiction over persons, property and conduct within their own frontiers.Footnote 111 Importantly, it is not confined to circumstances that take place in one state alone. The principle also allows for the exercise of authority over transnational conduct, provided it is based on a sufficient territorial link.Footnote 112 For instance, states regularly adopt laws with territorial extension.Footnote 113 These are legal provisions whose ‘application depends on the existence of a relevant territorial connection, but where the relevant regulatory determination will be shaped as a matter of law, by conduct or circumstances abroad’.Footnote 114 What types of connections allow for a territorial extension, however, is still unclear.Footnote 115 A glance at state practice reveals that measures are usually based on economic activity or presence on state territory.Footnote 116

Although measures with territorial extension are generally recognised, they have been the subject of contention. For instance, the EU Aviation Directive from 2008 included a territorial extension that gave rise to international quarrels.Footnote 117 It subjected greenhouse gas emissions of flights within and beyond European airspace to the EU emission trading scheme, provided that a flight departed from or arrived at an EU airport. The provision was brought before the European Court of Justice (ECJ), in part, based on the claim that the Directive would exceed the boundaries of jurisdiction.Footnote 118 Although the ECJ confirmed that the Directive builds on the territoriality principle,Footnote 119 the EU Commission suspended its implementation to allow for a multi-lateral solution.Footnote 120 Legislation with territorial extension has also been challenged through the dispute-settlement mechanisms of the World Trade Organization (WTO).Footnote 121 However, the body’s decisions remain inconclusive: while the WTO’s Appellate Body has not taken issue with territorial extensions per se, it has neither developed a systematic approach to the matter.Footnote 122

In view of the foregoing, some legal scholars doubt that legislation with territorial extension is permissible under all circumstances.Footnote 123 Critics are particularly concerned with the possible proliferation of the approach. Given the interconnectedness of global value chains and networks of ownership, different states may compete for jurisdiction based on some form of territorial connection.Footnote 124 Without any limiting factor, it is argued, the approach would grant states ‘nearly universal jurisdiction’.Footnote 125 For the present inquiry, it is sufficient to conclude that there are laws with territorial extension that even critics consider permissible under international law. These uncontested cases generally have two features: first, they are characterised by an international orientation and, second, they take precautions to prevent conflicts of laws.Footnote 126 As will be shown, these features reflect the reasonableness criteria, which are further discussed in Section IV.Footnote 127

B. The Nationality Principle

The second relevant basis for the exercise of prescriptive jurisdiction with extraterritorial reach is the active nationality principle.Footnote 128 This doctrine gives states jurisdiction over ‘the conduct, interests, status, and relations of its nationals and residents outside its territory’.Footnote 129 Legislation on the basis of nationality can be found in various legal areas, including criminal, tax and economic law.Footnote 130 Being generally accepted, the principle opens up opportunities for states to govern the activities of their corporate nationals worldwide.Footnote 131 The sticking point lies in the determination of corporate citizenship, for which there is no universal definition.Footnote 132 In practice, the nationality of a company is usually derived from (i) the state where it is incorporated; (ii) the country where the company has its headquarters or principal place of business; or (iii) the nationality of the owner or another entity in control.Footnote 133 Whereas the former approaches (i and ii) are recognised under customary international law,Footnote 134 the third method remains controversial.Footnote 135 Legislation extending to foreign-based entities on the sole basis of the active nationality principle is therefore likely to run into strong headwind at the international stage.Footnote 136

C. Applying the Principles of Jurisdiction and Reasonableness to the CSDDD

Based on the principles of jurisdiction discussed, this section establishes whether the CSDDD falls within the permissible scope. To comply with international law, the CSDDD, as an exercise of prescriptive jurisdiction, must draw on one or more jurisdictional bases.Footnote 137 For this requirement, it is expedient to distinguish between EU and non-EU companies. Moreover, the activities of these entities can be divided into those within and outside EU territory. This categorisation enables the personal scope of the CSDDD to be assessed against the principles of jurisdiction.

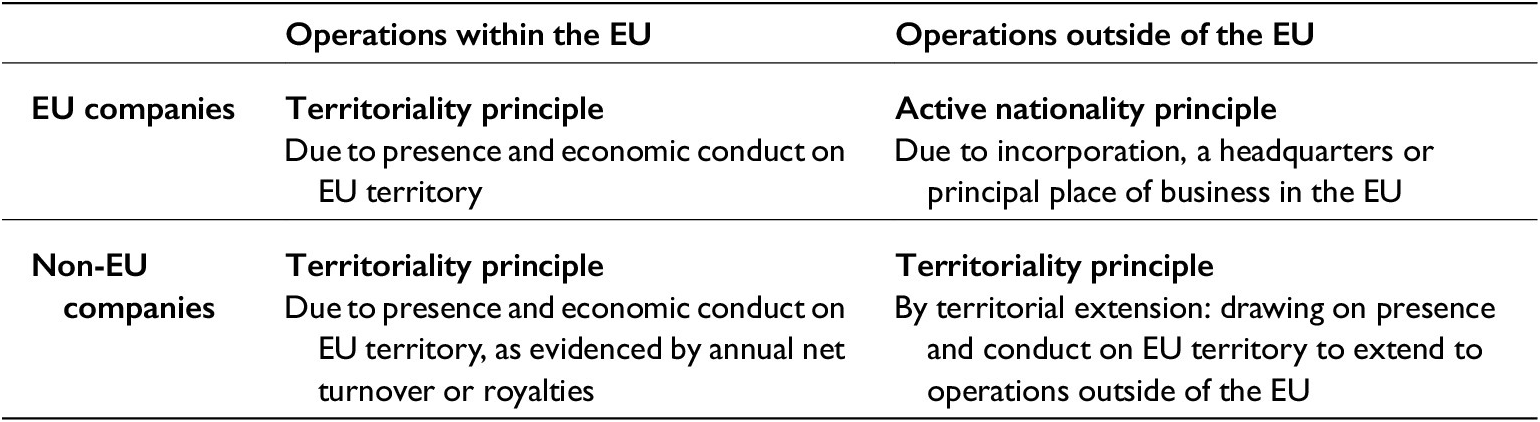

As regards EU companies, the jurisdictional bases of the CSDDD are straightforward. Where EU companies operate within the EU, the Directive draws on the territoriality principle, first, because EU companies are present on EU territory due to their incorporation in a Member State and, second, because they engage in economic conduct within the common market. The active nationality principle, in turn, allows EU lawmakers to govern the operations of EU companies abroad. With respect to non-EU companies, the CSDDD builds exclusively on the territoriality principle. Non-EU companies are subject to the due diligence requirements if they are present or doing business in the EU, as evidenced by a minimum annual net turnover or royalties generated in the EU.Footnote 138 According to recital 30 of the CSDDD, this criterion establishes the basis for requiring non-EU companies to conduct HREDD on their operations within the EU, as well as on their business activities outside EU territory. Insofar, the Directive includes a territorial extension given that compliance by non-EU companies is also shaped as a matter of law by their conduct abroad. The above table summarises how the personal and geographical dimensions of the CSDDD relate to the different jurisdictional bases (Table 1).

Table 1. Matching the CSDDD’s personal and geographical scope with the jurisdictional bases of territoriality and active nationality

IV. Reasonableness and Beyond

In addition to a jurisdictional basis, the exercise of authority with extraterritorial implications may call for an additional requirement: an overall reasonableness test. Whether customary international law prescribes this additional criterion is subject to debate, requiring further consideration in Subsection A. In addition, there is an ongoing controversy regarding the exercise of unilateral jurisdiction with extraterritorial implications, specifically in the EU context, as well as a fundamental discussion on the limitations of the law of jurisdiction, discussed in Subsection B. The remainder of this section dives into these debates to place the extraterritorial dimension of the CSDDD in the broader context.

A. The Rule of Reason

Some authorities and scholars consider a reasonableness test to be a mandatory precondition for the lawful exercise of jurisdiction.Footnote 139 The purpose of this requirement is to determine whether a particular claim to jurisdiction, though based on a jurisdictional basis, still interferes with the sovereignty of another state.Footnote 140 While the purpose of the test is evident, its substance is more ambiguous.Footnote 141 To make the requirement more operational, scholars have defined a set of criteria,Footnote 142 like the extent to which a unilateral act is embedded in the international context.Footnote 143 If a reasonableness test would be required under international law, non-compliance would render the CSDDD, as an assertion of prescriptive jurisdiction, an infringement of the principle of non-intervention. This could trigger a range of consequences like blocking statutes, economic sanctions and diplomatic fallout.Footnote 144

By contrast, other authorities reject the idea that a reasonableness requirement is necessary for the exercise of prescriptive jurisdiction.Footnote 145 Rather than introducing an additional prerequisite, this position deems a ‘genuine connection’ between the legislating state and the subject of regulation sufficient to prevent the arbitrary assertion of jurisdiction.Footnote 146 It is argued that additional reasonableness considerations are not a matter of customary international law, but international comity.Footnote 147

As the evidence of state practice establishing reasonableness as binding customary international law remains insufficient, this paper adopts the latter view.Footnote 148 Even proponents of the former position, including the American Law Institute, have revised their position.Footnote 149 The practice of the EU and its Member States does not support a requirement for reasonableness as a condition for exercising prescriptive jurisdiction either.Footnote 150 Rather than constituting a legal prerequisite, reasonableness considerations are best understood as a matter of international comity: a principle whereby states voluntarily take other states’ interests into account when exercising jurisdiction with extraterritorial implications.Footnote 151 In light of the foregoing, this paper proceeds on the basis that reasonableness is a matter of comity rather than customary international law.

However, the fact that reasonableness considerations are a matter of international comity does not imply that they are not important benchmarks for assessing legislation with extraterritorial implications. The international law of jurisdiction, while permitting states to assert authority based on recognized bases, is structurally deficient.Footnote 152 It allows multiple states to assert prescriptive jurisdiction over the same situations, creating risks of duplicative and even conflicting requirements affecting both regulated persons and international relations.Footnote 153 Reasonableness considerations can address limitations that jurisdictional bases alone cannot remedy: territoriality and nationality determine whether a state has jurisdiction but offer no guidance when multiple states address the same conduct.Footnote 154

Furthermore, reasonableness directly affects whether laws with extraterritorial implications achieve their objectives. Disregarding international comity can lead to misalignment with international standards and undermine multi-national initiatives. Reasonableness considerations are particularly salient in the case of the CSDDD, given its significant legal and socioeconomic implications in third countries, which warrant careful consideration beyond what is captured by the territoriality and active nationality principles. Even a perceived disregard of third countries’ legitimate interests may cause political backlash, which is likely to compromise the effectiveness of a law targeting transnational sustainability challenges.Footnote 155 Due diligence laws like the CSDDD should thus align with reasonableness criteria, not because international law requires it but because doing so enhances their effectiveness, demonstrates respect for other states’ legitimate interests, prevents conflicts of laws, and increases the likelihood of international cooperation.

The following analysis therefore examines whether the CSDDD qualifies as reasonable from the viewpoint of international comity. When considering established reasonableness considerations, four criteria merit further scrutiny.Footnote 156 First, the objective of the CSDDD is significant. Legislation is more likely to be reasonable if it addresses a matter of international concern rather than a unilateral interest.Footnote 157 Reversely, one may ask whether a law targets an internationally or a unilaterally condemned wrong.Footnote 158 The EU Directive requires companies to undertake HREDD pursuing the protection of internationally recognised human rights and environmental standards, as laid down in widely ratified international treaties.Footnote 159 Indeed, it seems EU lawmakers deliberately excluded regional instruments from the catalogue of international instruments listed in the Annex of the CSDDD.Footnote 160 The HREDD provisions thus target a matter of international concern, which renders the Directive more reasonable.

The reasonableness of a law hinges, second, on the level of international agreement on the substantive standard endorsed.Footnote 161 The CSDDD’s requirements on due diligence largely align with the UNGPs, which were adopted unanimously by the UN Human Rights Council.Footnote 162 Further evidence of state support for the concept of due diligence is that over 30 countries have adopted National Action Plans to implement the UNGPs.Footnote 163 Other countries have endorsed HREDD at least on a sectoral level,Footnote 164 or through their engagement with international organizations, which have adopted the approach, including the International Labor Organization,Footnote 165 the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights,Footnote 166 the Council of EuropeFootnote 167 and the African Union.Footnote 168 Consequently, there is broad international recognition of HREDD as a global standard.

A third reasonableness criterion is the regulatory design of laws with extraterritorial implications, that is, regulatory flexibility in substantial terms. A law is more prone to receive international recognition if it involves ‘principles-based and outcomes oriented’ rules rather than comprehensive and strict provisions.Footnote 169 The CSDDD meets these flexibility benchmarks. As discussed, it mostly defines obligations of means, granting companies discretion to determine what measures are appropriate in a particular context to identify and address adverse impacts. This margin of discretion is also in line with international standards.Footnote 170 Accordingly, the CSDDD does not put companies into a regulatory corset but offers them sufficient flexibility to tailor due diligence measures to their respective business context. This level of flexibility renders the HREDD provisions more reasonable from the viewpoint of international comity.

The rule of reason fourthly expects lawmakers to consider equivalent rules in other jurisdictions and relevant international developments.Footnote 171 This criterion prevents companies from facing overlapping or even conflicting legal requirements, facilitates international cooperation and recognises legitimate initiatives by third countries. In this regard, three aspects demand further consideration.

First, the CSDDD does not address the likely event of diverging HREDD laws in third countries.Footnote 172 Although legislation on due diligence has not yet been adopted outside Europe, similar legislation has already been discussed in nine non-European countries.Footnote 173 The adoption of the CSDDD itself may accelerate this development, as may the legally binding instrument on business and human rights currently under negotiation.Footnote 174 Consequently, there is a risk of non-aligned, or even conflicting, due diligence requirements with extraterritorial implications. Even when relevant jurisdictions base their laws on the same international framework, divergence is inevitable. The principles-based nature of international standards like the UNGPs leaves room for varying regulatory approaches.Footnote 175 As illustrated by the French, German and Norwegian due diligence laws, the personal and material scope, nature and depth of HREDD requirements as well as the mode of enforcement differ, despite drawing on the same international frameworks.Footnote 176 These divergences create compliance challenges for companies within the scope of different due diligence laws, as well as for entities that are indirectly affected due to cascading requirements, varying recognition of industry schemes and certification programmes, and diverse reporting requirements, information requests and stakeholder expectations. To address these concerns, a non-EU company that complies with a due diligence law in its country of incorporation could, for example, be exempted from the CSDDD’s requirements if the law sufficiently aligns with international standards. A relevant precedent is the EU Credit Rating Agencies Regulation, which holds the possibility of exemptions for regulatory addressees in third countries under specified conditions.Footnote 177 Another example is the EU Deforestation Regulation’s gradual approach to HREDD, which defines simplified due diligence requirements for operators sourcing from countries that the Commission considers to be at low risk of deforestation.Footnote 178 The EU seems to have taken notice of this issue. In a Joint Statement on the US-EU trade relations from August 2025, the EU ‘commits to work to address US concerns regarding the imposition of CSDDD requirements on companies of non-EU countries with relevant high-quality regulations’.Footnote 179 It remains to be seen whether this commitment will result in deregulation or nuanced requirements for third-country companies.

Second, the CSDDD could anticipate future international developments by making provisions for the potential conclusion of a multi-lateral treaty on corporate sustainability.Footnote 180 This could take the form of a dedicated review clause. One example is the EU Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive, which stipulates that the EU lawmaker ‘shall take due account of developments at international level and discussions with third countries and international organisations’.Footnote 181 Such provisions serve multiple functions: they create legal obligations for the Commission to monitor international developments, establish triggers for regulatory reconsideration, and signal to third countries the EU’s willingness to align with multi-lateral approaches. Comparable provisions could be added to the CSDDD by amending its review clause to facilitate international cooperation.Footnote 182

A third feature ensuring jurisdictional flexibility would be to recognize due diligence standards developed by third countries, regional actors, or multi-stakeholder organizations, provided they align with international standards. The CSDDD takes this aspect into account by granting companies the option to involve industry schemes and multi-stakeholder initiatives, where appropriate.Footnote 183 According to the relevant definition, this includes present and future initiatives involving state actors.Footnote 184 Thus, companies can choose to participate in industry schemes and multi-stakeholder initiatives (co-)sponsored by third countries for the purpose of compliance with the CSDDD. The only caveat is that the Directive requires such initiatives to meet fitness criteria to be defined by the Commission.Footnote 185 To ensure jurisdictional flexibility, it will be crucial for the Commission to align these fitness criteria with international standards.

The previous assessment shows that the Directive broadly meets relevant reasonableness criteria, as required by international comity.Footnote 186 However, several qualifications apply: first, the EU lawmaker should make provisions for future developments at the international level, such as the dissemination of HREDD laws in third countries or the conclusion of a multi-lateral treaty. This would ensure that the EU’s unilateral approach takes account of third-country initiatives, avoids conflicts of laws and aligns with international developments. Furthermore, the rule of reason calls for close alignment with international standards, especially when determining the fitness of industry- and multi-stakeholder initiatives. Reasonableness should also guide the upcoming transposition and implementation of the Directive. To adhere to the discussed reasonableness criteria, transposition laws and accompanying measures should therefore closely align with international standards, particularly the UNGPs, given their international recognition.

B. Ongoing Controversies Concerning Extraterritoriality

The preceding analysis demonstrates that the CSDDD complies with the law of jurisdiction by drawing on recognised jurisdictional bases, while also broadly adhering to the rule of reason as a matter of international comity. However, there remain structural limitations in the principles of jurisdiction when applied to unilateral legislation addressing transnational sustainability challenges. This section examines scholarship that exposes these limitations and derives policy recommendations that, while not mandated by international law, are essential to ensure the Directive’s legitimacy and effectiveness. These considerations arise from legal analysis but extend beyond formal legal requirements to address questions of global policy.

Legal scholars have long discussed the global reach of EU law. Bradford famously coined the term ‘Brussels Effect’ to critique the EU’s ‘unilateral power to regulate global markets’.Footnote 187 In a rebuttal, Scott convincingly countered the portrayal of the EU as a hegemonic unilateralist by showing that the EU largely adopts laws with territorial extension that meet reasonableness criteria, including a clear international orientation.Footnote 188 However, other critics not only challenge the exercise of unilateral jurisdiction with extraterritorial implications, but also the law of jurisdiction itself. Krisch contends that the territoriality principle and considerations of reasonableness no longer provide the necessary constraints on state sovereignty.Footnote 189 Instead, he argues that states are increasingly exercising ‘unbound jurisdiction’, resulting ‘in a jurisdictional assemblage with overlapping claims of many different states’.Footnote 190 Krisch argues that the exercise of jurisdiction depends more and more on the power of a country; an argument that can be extended to the CSDDD, whose intended (and unintended) extraterritorial implications depend de facto on the economic clout of the EU common market. Criddle shares Krisch’s concern about states abusing territorial jurisdiction for hegemonic purposes, and asserts that the right to self-determination would limit states’ authority to exercise prescriptive jurisdiction.Footnote 191

Legal scholars in the tradition of Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL) raise additional questions.Footnote 192 Okowa, for instance, sets forth democratic arguments against unilateral legislation with extraterritorial implications.Footnote 193 Whereas treaties would involve international negotiations and – at least in dualistic systems – ratification on the domestic level, unilateral legislation excludes foreign countries and their populations from the process of deliberation.Footnote 194 Similarly, Lichuma holds that business laws promoting human rights, ‘despite their best intentions, inadvertently or otherwise reinforce already existing inequalities and power imbalances to the detriment of Third World states and peoples’.Footnote 195 In the absence of an international treaty, Lichuma calls for consultations with states likely to be affected by HREDD legislation,Footnote 196 a call that, she finds, went unheeded in the legislative process that led to the CSDDD.Footnote 197

What follows is that the principles of jurisdiction and international comity have their limitations. There are legitimate concerns about the ability of these concepts to constrain unilateral legislation with extraterritorial effects, given their imperial undertones and growing mismatch with the realities of economic globalisation. Indeed, the CSDDD is a prime example of unilateral legislation that, while striving to promote international standards, poses significant extraterritorial challenges, which are not fully captured by principles of territoriality, active nationality and reasonableness discussed.

Against this backdrop, the CSDDD will continue to face political headwinds. The Directive has already prompted concerns about EU regulatory overreach from third countries, as illustrated by responses from Qatar and the United States regarding the potential impact on their companies and economic interests.Footnote 198 EU lawmakers must navigate between legitimate concerns about third countries’ regulatory autonomy, on the one hand, and pressures to dilute sustainability standards for purely competitive reasons, on the other.

Two policy responses seem advisable. First, the EU should systematically monitor and research the Directive’s extraterritorial implications: not only the direct and indirect legal effects discussed but also the socioeconomic impacts along global value chains, including potential shifts in trade patterns. Second, the EU should robustly implement the CSDDD’s accompanying measures to support meaningful compliance. These measures should consider companies and smallholders in third countries indirectly affected by the new requirements, aiming to build capacity, prevent undue responsibility-shifting and limit socioeconomic repercussions. Although these demands find no strict basis in the law of jurisdiction as currently conceived, they are expedient for the EU to credibly advance international standards on responsible business conduct, prevent backlash from affected states and stakeholders, and achieve the Directive’s stated goal of contributing ‘to sustainable development and the sustainability transition of economies and societies’ in Europe and beyond.

V. Conclusion

Global sustainability challenges demand regulatory solutions that carefully balance regulatory ambition with respect for international law, the sovereign interests of third countries and legitimate concerns of affected stakeholders. This article has argued that unilateral due diligence laws, such as the CSDDD, offer a credible regulatory path alongside multi-lateral initiatives. However, given the interconnectedness of the global economy, unilateral approaches demand caution. The so-called ‘butterfly effect’ suggests that even small interventions in dynamic systems can lead to unpredictable consequences.Footnote 199 The same arguably applies to due diligence laws considering their extraterritorial implications, including the risks of companies unduly shifting responsibilities onto business partners along global value chains, as well as the potential for socioeconomic repercussions in third countries through significant market withdrawals.

The inquiry into the international law of jurisdiction has ascertained that due diligence laws, as assertions of prescriptive jurisdiction, must draw on jurisdictional bases to ensure the regulating state is genuinely linked to the subject of legislation. The CSDDD adheres to these requirements by drawing on the principles of nationality and territoriality to define HREDD requirements for EU and non-EU companies. While reasonableness is not a mandatory requirement under customary international law, international comity demands that due diligence laws adhere to reasonableness criteria. The analysis has demonstrated that the CSDDD largely meets these standards. It aims to protect internationally recognised human rights and environmental standards, adopts an internationally endorsed approach, and provides regulated entities with sufficient flexibility. It also recognises industry schemes and multi-stakeholder initiatives involving third countries. However, the Directive’s regulatory design calls for enhancement to take adequate account of foreseeable developments at the international level, such as the proliferation of equivalent legislation in third countries or the conclusion of a legally binding instrument.

Beyond compliance with jurisdictional principles and international comity, the assessment has exposed structural limitations in the law of jurisdiction when applied to unilateral legislation addressing transnational sustainability challenges. The CSDDD’s extraterritorial implications, while striving to promote international standards on responsible business conduct, risk perpetuating global inequalities, excluding affected states and populations from the legislative process, and reinforcing power imbalances, disadvantaging states with less economic clout. Consequently, EU lawmakers are well advised to monitor the Directive’s extraterritorial implications and implement accompanying measures that mitigate adverse impacts in third countries. Transposing and implementing the CSDDD thus requires diligence on the part of lawmakers to ensure that the Directive is an effective response – rather than a disservice – to the challenge of business-related human rights abuse and environmental harm. Scholarship will play a crucial role in examining the CSDDD’s broader implications and effectiveness in addressing transnational sustainability challenges.