According to what we can call the Dual View, both absolute and comparative welfare provide moral reasons. The absolute part claims that we have moral reasons to make individuals well off and prevent them from being badly off. This accounts for our moral intuitions in variable-population choices: it solves the Non-Identity Problem, avoids anti-natalist implications, and explains why we shouldn’t create people with bad lives. The comparative part claims that we have moral reasons to make individuals better off and prevent them from being worse off than they would otherwise be. That captures our moral intuitions about harms and benefits; that we have moral reasons to realise welfare gains and prevent welfare losses for individuals.

Some philosophers have pointed towards the Dual View. Jeff McMahan (Reference McMahan1981: 105 and Reference McMahan2013) claims that, next to ordinary comparative benefits and harms, existential non-comparative benefits and harms morally matter. Larry Temkin (Reference Temkin2012: chs. 11–12) believes that both impersonal considerations about total welfare and narrow person-affecting considerations about the gains and losses of particular individuals are morally relevant. So, both authors accept that absolute and comparative welfare provide moral reasons. McMahan (Reference McMahan, Coleman and Morris1998: 243–244 and Reference McMahan2013: 15–20) also discusses whether non-comparative benefits have less weight than comparative benefits. However, neither McMahan nor Temkin investigates how the two parts of the Dual View relate to each other in general.Footnote 1

This paper explores how a theory based on the Dual View can be developed: How should the two parts be combined? Given its dual reason-giving force, which moral reasons does welfare provide overall? I’ll present the two parts of the Dual View in section 1 and argue that we should accept them. Section 2 distinguishes two ways of developing the dual theory that differ regarding the level at which we combine the moral reasons of the two kinds of welfare – at the collective or individual level. In sections 3 and 4, I present the collective version and show that it’s confronted with severe objections. In sections 5 and 6, I develop the individual version with a refinement that avoids the objections, but I argue that it implies hypersensitivity and contradicts the prioritarian idea. In sections 7 and 8, I reconsider the objections: we can avoid one objection by accepting an asymmetry about comparative welfare and bite the bullet on the other objection rather than adopting recent solutions to the so-called problem of improvable life avoidance.

1 The dual reason-giving force of welfare

The Dual View claims that welfare has a twofold reason-giving force: insofar as things are good or bad for individuals and insofar as things are better or worse for them relative to an alternative. It consists of the following parts.

Absolute View: Given a set of outcomes M that an agent can realise, the extent to which an outcome A is good or bad for an individual p provides a moral reason to realise or prevent A rather than any other outcome within M.

Comparative View: Given a set of outcomes M that an agent can realise, the extent to which an outcome A is better or worse for an individual p than another outcome B within M provides a moral reason to realise or prevent A rather than any other outcome within M.

I assume two things for which I have no space to argue. First, the Dual View presupposes

Existence-Non-Comparativism: An individual’s existence cannot be better, worse, or equally good for an individual than the individual’s non-existence.Footnote 2

This is a common but controversial assumption.Footnote 3 Without it, however, we wouldn’t need the Dual View because welfare gains and losses would provide all moral reasons needed. Second, I assume that the individuals’ lifetime welfare is morally relevant. While this sidesteps approaches that consider an individual’s negative and positive welfare within a life to provide different reasons, it’s a common and reasonable assumption.Footnote 4

The Absolute View is straightforward: An individual’s positive welfare in an outcome provides reasons to realise that outcome; the individual’s negative welfare provides reasons to prevent that outcome.

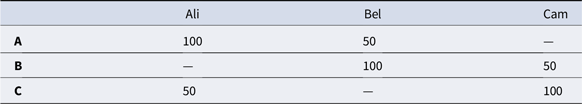

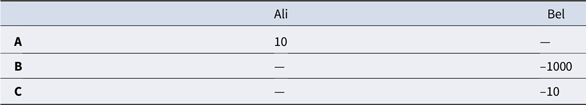

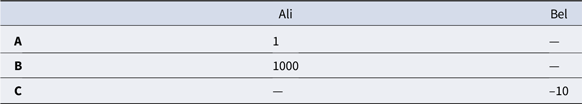

The Comparative View comes with more prerequisites: it understands comparative reasons as set-wise rather than pairwise.Footnote 5 While pairwise reasons favour or disfavour an outcome only relative to the outcome compared with which an individual gains or loses welfare, set-wise reasons do so relative to all other available outcomes – all outcomes within M. However, the pairwise understanding implies cyclical reason-assessments and obligations. Consider the Cyclic Case in Table 1, where the numbers represent the individuals’ welfare levels in the outcomes and “—” indicates that an individual doesn’t exist. Given a pairwise understanding, the Comparative View implies that we have moral reasons to realise B rather than A, C rather than B, yet A rather than C. Since everything else is equal and assuming that we ought to do what we have the strongest reason to do, it also implies that we ought to realise B rather than A, C rather than B, yet A rather than C. Hence, whatever outcome we choose to realise, there is always an outcome we ought to realise instead.Footnote 6 This is absurd.Footnote 7

Table 1. Cyclic Case

The set-wise understanding avoids these problems. If the reasons provided by the individuals’ welfare gains and losses are set-wise, they are reasons to realise or prevent an outcome rather than any other available outcome. Since the gains and losses are equal in all three outcomes, we have equally strong comparative reasons to realise and prevent each of the three outcomes. Therefore, we should accept the set-wise understanding: welfare gains and losses in an outcome relative to an alternative provide moral reasons to realise and prevent that outcome rather than any other available outcome.Footnote 8

Why should we accept the Dual View? Both parts are necessary to comprehensively account for our moral concerns towards the welfare of individuals. In a nutshell, only the Absolute View accounts for our moral reasons towards the welfare of all individuals who exist in only one of the available outcomes, and only the Comparative View captures our moral reasons towards all individual harms and benefits or welfare gains and losses.

Consider the Absolute View first. If absolute welfare didn’t provide moral reasons, we would have no reason to prevent an outcome in which an individual who doesn’t exist in any alternative leads a miserable life.Footnote 9 Furthermore, if we could bring into existence either a moderately happy individual or another very happy individual, everything else being equal, we wouldn’t have any moral reason to create the happier individual. We wouldn’t solve the Non-Identity Problem.Footnote 10 Both implications are absurd. We have moral reasons to prevent the existence of individuals with bad lives and to create, of two possible people, the one who has the higher level of welfare. Therefore, we should accept the Absolute View.

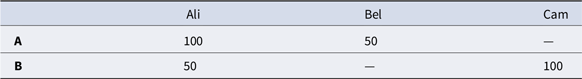

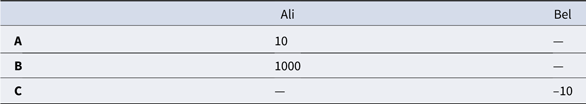

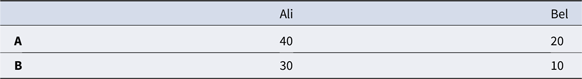

The Comparative View accounts for our moral reasons to benefit and not harm individuals. This is so, as I’ll assume, if benefits and harms are understood in a counterfactual comparative sense: An act benefits or harms an individual if it makes the individual better or worse off than they would have been had the act not been performed.Footnote 11 Only if the Comparative View is correct, do we always have moral reasons to realise welfare gains and to prevent welfare losses to individuals. You might object that our moral reasons provided by the individuals’ absolute welfare would already capture that because a gain of welfare implies an increase, and a loss of welfare implies a decrease, of the individual’s absolute welfare. However, the Absolute View cannot fully account for our moral reasons provided by welfare gains and losses, as the cases shown by Tables 2 and 3 illustrate.Footnote 12

Table 2. Identical absolute welfare profile with loss

Table 3. Identical absolute welfare profile without loss

The anonymised absolute welfare profile is identical in all four outcomes: one individual is very well off, and one is moderately well off. Therefore, if only absolute welfare provided moral reasons, our moral reasons to realise any of the outcomes would be equally strong. We should then be morally indifferent between realising A or B, just as we are about realising C or D. However, this overlooks a crucial difference. If we choose A in the first case, Ali will be much better off than if we choose B. In the second case, by contrast, no matter whether we choose C or D, no individual will be better or worse off than in the alternative. Thus, if we realise A, Ali will gain welfare; if we realise B, Ali will lose welfare. Since we have moral reasons to realise gains and prevent losses for individuals, we have moral reasons to realise A rather than B. The Absolute View, however, cannot capture that. Consequently, to comprehensively account for our moral reasons towards welfare gains and losses of individuals, we must accept the Comparative View, too. We have equally strong absolute reasons for all four options and comparative reasons in favour of A and against B.Footnote 13

The Dual View might be charged with double-counting: the welfare of individuals who exist in more than one outcome would be counted twice. However, the Dual View doesn’t count anything doubly in a strict sense. Rather, two different things matter: the individuals’ absolute welfare level and the individuals’ comparative welfare gains and losses. Neither of the two is counted twice! Second, even if it is one, the form of double-counting employed by the Dual View is justified. If we are concerned only with choices that don’t influence the population, absolute and comparative welfare coincide: for each alteration x of an individual’s absolute welfare, there is a gain, respectively a loss, for that individual of size x; alterations of the absolute welfare and occurrences of gains and losses of welfare necessarily coincide. If our choices influence the population, by contrast, absolute and comparative welfare come apart. This is because, if an individual doesn’t exist in the alternative, it has absolute welfare but no welfare gains or losses. Therefore, the dual reason-giving force of welfare emerges first when we consider choices that affect the population. Consequently, the double-counting, if there is any, is an advantage of the Dual View. It captures our moral concerns towards welfare not only in fixed-population choices but also in variable-population choices. The Dual View, thus, consistently counts the welfare of some individuals doubly or, as we would better say, dually: insofar as things are both good or bad and better or worse for these individuals.

2 Two approaches to the dual theory

The Dual View comprises the Absolute View and the Comparative View. Yet, these views yield only pro tanto moral reasons. Which moral reasons does welfare provide overall?

To streamline the discussion, let’s introduce some terminology. Call moral reasons provided by absolute welfare absolute reasons and moral reasons provided by comparative welfare comparative reasons, and call moral reasons provided by both absolute and comparative welfare combined reasons. The reasons provided by the welfare of an individual p can be called reasons regarding p. The qualifier “aggregated” denotes the reason provided by the absolute and/or comparative welfare of all individuals, and the qualifier “overall” indicates that we are concerned with the aggregated combined reason. For simplicity, I’ll skip the qualification “moral” and use “reason for or against an outcome” as shorthand for a moral reason that an agent has to realise or prevent an outcome. The question then is this: Given that welfare provides absolute and comparative reasons, which overall reason does it provide?

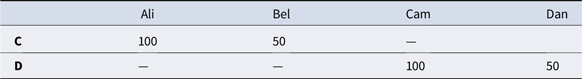

The dual theory could be developed in two ways, as illustrated in Figure 1. The small circles represent the reasons provided by the welfare of the individuals p1 to p n , and the large circles represent the aggregated reasons. To distinguish the two ways, we can ask: on which level do we combine the absolute and comparative reasons? On the Collective Approach, they’re combined at the collective level. Hence, we first aggregate the absolute and comparative reasons separately across all individuals and then combine these aggregated reasons. On the Individual Approach, the reasons are combined at the individual level. Hence, we first combine the absolute and comparative reasons for each individual and then aggregate these combined reasons across all individuals.

Figure 1. Collective approach vs. individual approach.

In the next two sections, I’ll develop and discuss the dual theory based on the Collective Approach. In sections 5 and 6, I’ll do so for the Individual Approach.

3 The collective dual theory

On the Collective Approach, we first aggregate the absolute and comparative reasons separately across all individuals and then combine the aggregated reasons into overall reasons. Call this the Collective Dual Theory. Its general principle is the

Collective Dual Principle: In a choice between n outcomes O 1 to O n , we have a stronger overall reason to realise or prevent outcome O 1 than to realise or prevent another outcome O 2 if and only if the aggregated absolute reason for or against O 1 combined with the aggregated comparative reason for or against O 1 is stronger than those reasons combined for or against O 2 .

The principle is the most general version of the Collective Dual Theory. It leaves open both how the two kinds of reasons are aggregated, respectively, and how these aggregated reasons are combined.

Consider first the aggregation of the reasons across all individuals. We can adopt a fully additive approach that aggregates the reasons by summing up their strengths – a utilitarian version of the Collective Dual Theory. We could limit additive aggregation by, for example, adding only the strengths of the reasons provided by sufficiently similar absolute and comparative welfare, respectively, as advocated by proponents of partial or limited additive aggregation. We could even reject additive aggregation altogether and claim, for example, that the strength of the aggregated reason is equivalent to the strength of the strongest (absolute or comparative) reason regarding a single individual. This could provide versions of the Collective Dual Theory that align with the complaint model.Footnote 14 The Collective Dual Principle can be specified by any of these options, and I don’t take a stand on the matter here.

Next, consider how the Collective Dual Theory can combine the aggregated absolute reasons and the aggregated comparative reasons. Countless options are possible. Let’s consider some. First, we can advance a dominance principle according to which we have overall reason to realise an outcome rather than another if both the aggregated absolute reason and the aggregated comparative reason speak in its favour. That seems plausible, but it won’t suffice for a comprehensive theory because the dominance principle is silent if the two parts of the Collective Dual Theory favour different options.

Second, we could claim that one of the two parts of the Dual View has absolute priority over the other. This would reduce the other part to a mere tiebreaker. For example, if we claimed that absolute reasons have priority because it’s most important to create individuals with good rather than bad lives, the welfare gains and losses would only become effective when equally strong absolute reasons speak in favour of two outcomes. If, by contrast, we claimed the comparative reasons to have absolute priority, the welfare of additional individuals whom we could create would only matter when equally strong comparative reasons speak in favour of the outcomes.

However, I don’t think that either of the two parts has absolute priority. It lacks intuitive plausibility and has counterintuitive implications. If absolute reasons had absolute priority, we wouldn’t have any reason to greatly benefit individuals and greatly reduce harm to them at the cost of an arbitrarily small reduction in absolute welfare. Similarly, if comparative reasons had absolute priority, we wouldn’t have any reason to create very many happier rather than less happy individuals or prevent the existence of many suffering individuals at the cost of an arbitrarily small reduction in welfare losses or missed increase in welfare gains. Both implications seem implausible and in tension with the motivation for the Dual View.

The point can be generalised. The function that we employ to combine the aggregated absolute and comparative reasons should be strictly monotonically increasing in each of the arguments. The Collective Dual Theory should satisfy the

Combination Condition: If the strength of an aggregated absolute or comparative reason to realise or prevent an outcome rises, so does the strength of the overall reason to realise or prevent that outcome; if the strength of an aggregated absolute or comparative reason to realise or prevent an outcome falls, so does the strength of the overall reason to realise or prevent that outcome.

A version of the dual theory that doesn’t satisfy the Combination Condition is confronted with what I call the Addition Objection: It has counterintuitive implications in cases in which we cause additional individuals to exist or bring about additional gains and losses. Suppose a strengthening of the aggregated absolute reason wouldn’t always imply a strengthening of the overall reason. Then, we might not have an overall reason to create a very happy rather than a barely happy individual, everything else being equal. This is absurd and contradicts one important reason in favour of the Dual View: that it solves the Non-Identity Problem. Furthermore, suppose that a weakening of the aggregated absolute reason wouldn’t always imply a weakening of the overall reason. Then, we might not have an overall reason to prevent the existence of an additional individual with a horrible life, everything else being equal. This is utterly absurd. We have a particularly strong overall reason to prevent the existence of every additional miserable individual! Analogous implications would follow regarding the comparative reasons if the Combination Condition weren’t satisfied: we might not have reasons to realise additional welfare gains and prevent additional welfare losses. Therefore, the Collective Dual Theory must comply with the Combination Condition.

How should we combine the two parts of the Dual View given the Combination Condition? While many ways would satisfy the Combination Condition, the following view seems natural. The Absolute View and the Comparative View specify two separate moral ideals that provide independent reasons. The considerations of absolute and comparative welfare tilt the moral scale in one or the other direction, just as weights cause a scale to swing in one or the other direction depending on which side of the scale they are placed. The more of the considerations count in favour of an outcome, regardless of their kind, the more the moral scale tilts towards that outcome, where each consideration adds weight to the respective side of the scale. If this is plausible, we should adopt an additive combination of the aggregated reasons.

We might want to refine the simple additive combination, though. It arbitrarily fixes the relative moral importance of absolute and comparative welfare without any room for adjustment. Yet, one of the two views – the Absolute or the Comparative View – might be more important.Footnote 15 We could implement that by adding weights to the two parts of the Collective Dual Theory. While any particular weight might still be arbitrary to some degree, such weights at least allow us to fine-tune the relative moral importance of absolute and comparative welfare.

However, both the simple and the weighted addition approaches are subject to what we can call the Negligence Objection. Suppose many people gain or lose welfare in an outcome relative to another one, yet far more people exist in only one outcome but not in the alternative. As a consequence, the influence of the Comparative View on the overall reasons will be relatively small. The more people exist in the two outcomes who don’t exist in the alternative, respectively, the less important the comparative welfare becomes relative to absolute welfare – up until the point where the comparative welfare becomes morally insignificant and will be neglected. We might claim that, even in such cases, the comparative reasons should keep a substantial influence on our overall reasons for or against the outcomes.

We can both fine-tune the relative importance of the two parts of the Dual View and avoid the Negligence Objection by employing what Temkin (Reference Temkin2012: sec. 10.6) calls a capped model of moral ideals. On that version, the influence on our overall reasons to realise or prevent an outcome of both the aggregated absolute and the aggregated comparative reasons is limited. We can picture that as follows: Each outcome merits two numerical scores, one representing the strength of the aggregated absolute reason and one representing the strength of the aggregated comparative reason for or against the outcome. The overall reason is then determined by adding the two scores. Yet, the extent to which the two kinds of reasons can influence the score is limited by an upper bound for reasons in favour of the outcome and a lower bound for reasons against the outcome.

The capped model opens room to fine-tune the relative weight of the absolute and the comparative reason. If the Absolute View and the Comparative View have equal moral importance, the (positive and negative) maximum scores for the two kinds of reasons are equal. For example, both absolute and comparative welfare can provide a maximum score of 1000 for the reasons in favour of an outcome and a minimal score of –1000 for the reasons against the outcome. We would have maximal overall reasons in favour of an outcome if the outcome scores 1000 for absolute welfare and 1000 for comparative welfare. If one score were lower, we would have correspondingly weaker overall reasons. We would have maximal reasons against an outcome if it scored –1000 for both absolute and comparative welfare. Since the sum of the scores represents the strength of the overall reason in favour of or against an outcome, we have reason to realise the outcome with the higher sum over outcomes with lower sums. If we believed that absolute welfare matters more than comparative welfare, we would give it a higher maximum score, and vice versa; and absolute and comparative welfare could have additional or perhaps increasing weight between the caps.

Furthermore, the capped model can avoid the Negligence Objection. The maximum score representing the strength of both the aggregated absolute reason and the aggregated comparative reason is limited. Therefore, neither of the two scores can exceed the other infinitely, and thus neither of the two kinds of aggregated reason will be neglected.

The capped model can be spelt out in various ways. We could endorse caps for only one part of the dual theory, say only for absolute reasons; we could aggregate reasons in favour of an outcome and reasons against an outcome separately and assign different caps; we could assign caps only for the reasons in favour of outcomes but not for the reasons against outcomes; and, again, we could do so for one but not for the other part of the dual theory.

Furthermore, we need to specify how the two kinds of aggregated reasons transform into the scores that represent the strength of our overall reason. In principle, a cap of aggregated reasons could be approached linearly. Then, however, while additional reasons proportionally increase the strength of the aggregated reason if that strength remains below the cap, additional reasons don’t increase the strength of the aggregated reason at all when the cap has been reached. This violates the Combination Condition. If we endorsed the capped model, therefore, we should accept an asymptotic approach: the strengths of the aggregated reasons approach but never actually reach the maximum that is determined by the caps. The absolute welfare of additional people and additional gains and losses will then matter less as we approach the limits set by the capped model. Nevertheless, they’ll always influence the strength of our overall reasons. The asymptotic approach thus ensures that additional individuals with merely absolute welfare and additional gains or losses for individuals always matter. Admittedly, however, if one score is close to its upper or lower cap but the other isn’t, changes to the respective kind of welfare will become relatively unimportant.

The Collective Dual Principle provides one way to develop a moral theory based on the Dual View. It can be refined to align with various views on aggregation, and it can employ various ways of combining the aggregated absolute and the aggregated comparative reasons. The theory should comply with the Combination Condition to avoid the Addition Objection, it should have room to fine-tune the relative weight of absolute and comparative reasons, and it should avoid the Negligence Objection. As I have shown, a capped additive approach seems fitting for those purposes, or at least better suited than the alternatives that I’ve discussed.

4 The positive and negative lives objections

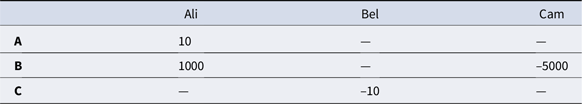

The Collective Dual Theory is confronted with two serious objections. Consider the Negative Life Case as illustrated in Table 4. On the Collective Dual Principle, we likely have stronger overall reasons to realise C than to realise A. This is because Bel’s massive welfare gain in C relative to B provides a strong comparative reason for C, while Ali’s slightly positive absolute welfare provides only a weak reason for A and Bel’s slightly negative absolute welfare only a weak reason against C. Since the absolute reasons are only weak, but the comparative reason is very strong, and given the Combination Condition, we likely have an overall reason to realise C rather than A. On the Collective Dual Principle, therefore, if an individual gains enough welfare relative to a third outcome, we can have a stronger overall reason to create this individual with a bad life than to create another individual with a good life, everything else being equal in those two outcomes. This, however, seems absurd. Call it the Negative Lives Objection.

Table 4. Negative Life Case

A similar objection holds for positive lives – the Positive Lives Objection. In the Positive Life Case, as shown in Table 5, Ali’s massive welfare loss in A relative to B provides a strong comparative reason against A. Even though this reason will be slightly mitigated by Ali’s positive welfare level in A, the overall reason to prevent A is likely to be stronger than the overall reason to prevent C. On the Collective Dual Principle, therefore, if an individual loses sufficiently much welfare relative to a third outcome, we can have a stronger overall reason against creating this individual with a good life than against creating another individual with a bad life, everything else being equal. While that verdict may not be as absurd as the equivalent for a bad life, the implication still seems implausible.

Table 5. Positive Life Case

Before I continue, let me briefly address one worry. The objections could be seen as weaker instances of what is known as the problem of improvable life avoidance: it shouldn’t be impermissible to create a good life just because that life could be improved.Footnote 16 However, there are important differences. First, the problem of improvable life avoidance concerns only welfare losses and thus, if at all, only the Positive Lives Objection would coincide with it. The Negative Lives Objection, by contrast, points out that welfare gains for an individual can provide reasons in favour of creating the individual even if that individual has a bad life. Second, the problem of improvable life avoidance merely states that it shouldn’t be impermissible to create an improvable but good life. The objections raised here, by contrast, point out that comparative reasons can make the creation of an individual with a good life less choiceworthy than the creation of another individual with a life not worth living. This seems problematic even if we accept obligations to prevent improvable lives. Thus, the objections here are distinct and go beyond the problem of improvable life avoidance. In section 8, however, I’ll discuss whether the proposed solutions to the problem can help us with the objections.

Back to the Positive and Negative Lives Objections, we might think that certain specifications of the Collective Dual Principle can avoid them. First, we could adopt a prioritarian weighting, according to which welfare gains and losses matter less the better off the individual is who gains or loses.Footnote 17 In the Positive Life Case (Table 5), this might render Ali’s loss in A relative to B less morally significant. If the prioritarian weighting function were steep enough, Ali’s loss in A relative to B wouldn’t morally outweigh the difference in absolute welfare between A and C. That would reduce the severity of the Positive Lives Objection. However, the prioritarian weighting aggravates the Negative Lives Objection. Gains and losses at low absolute levels matter more. In the Negative Life Case (Table 4), therefore, Bel’s gain in C relative to B provides an even stronger reason for C with the prioritarian weighting. Thus, the Negative Lives Objection would worsen.

Second, we could give absolute reasons more weight than comparative reasons by introducing a weighting factor large enough to block the absurd implications in the two cases. However, this merely mitigates the objection. We can construct cases for any weighting factor that doesn’t reduce the relative weight of the comparative reasons to zero, such that an individual’s gain outweighs its bad life and an individual’s loss outweighs its good life.

Third, we could adopt the capped model and set a lower limit for the aggregated comparative reason than for the aggregated absolute reason. However, to avoid the unwanted implications, the limit would need to be reached even if only one individual’s comparative welfare is at stake, as in the Negative and Positive Life Cases. If the limit blocked the objections, the comparative welfare of other individuals in cases that involve more individuals would barely matter. Yet, this avoids the objections only on pain of another implausible implication.

If we want to avoid the Negative and Positive Lives Objections, the welfare of an individual who has a bad life in an outcome cannot provide a combined reason in favour of that outcome no matter how much welfare the individual gains relative to an alternative, and the welfare of an individual who has a good life in an outcome must not provide a combined reason against that outcome no matter how much the individual loses relative to an alternative. Therefore, we need to restrict the influence of the comparative reasons: the individuals’ welfare gains cannot outweigh their negative absolute welfare, and the individuals’ welfare losses cannot outweigh their positive absolute welfare. In other words, the following condition must hold:

Positive and Negative Lives Condition: In a choice between some outcomes, if an individual has a good or bad life in outcome A, the individual’s welfare must provide a combined reason for or against A.

This can be achieved only if we combine the absolute and comparative reasons regarding each individual before we aggregate these combined reasons across all individuals. However, the Collective Approach doesn’t allow for that because it first aggregates the absolute and the comparative reasons across all individuals before it combines those aggregated reasons. Hence, the Positive and Negative Lives Condition suggests that we drop the Collective Approach in favour of the Individual Approach.

5 The individual dual theory and subordinate relation

On the Individual Approach, we first combine the absolute and comparative reasons regarding each individual and then aggregate these combined reasons across all individuals into an overall reason for or against the available outcomes. The Individual Approach is attractive if the absolute and comparative reasons regarding one individual are interdependent, as the Positive and Negative Lives Objections suggest. Before we consider how the Individual Approach can avoid those objections, let’s define the Individual Dual Theory. Its general principle is the

Individual Dual Principle: In a choice between n outcomes O 1 to O n , we have a stronger overall reason to realise or prevent an outcome O 1 than to realise or prevent another outcome O 2 if and only if the individually combined and then aggregated reason for or against O 1 is stronger than such reason for or against O 2 .

The Individual Dual Principle leaves open both how the absolute and comparative reasons regarding each individual are combined and how these individually combined reasons are aggregated. In principle, the Individual Dual Theory can be paired with views similar to those that we considered for the Collective Dual Theory. We can, for example, aggregate the combined reasons by adding up their strengths across all individuals; we can limit or entirely reject additive aggregation. To combine the absolute and comparative reasons regarding each individual, we could add up their strengths and supplement that approach with weights or caps.

To avoid the Positive and Negative Lives Objections, however, the Individual Dual Theory needs to satisfy the Positive and Negative Lives Condition. It will do so only if the comparative reasons don’t count in addition to or separately from the absolute reasons. Rather, they must depend on those reasons. One possibility is to understand comparative reasons as being subordinately related to absolute reasons – as specified by

Subordinate Relation: Comparative reasons enhance and reduce absolute reasons, but their influence is limited: the comparative reason regarding an individual can mitigate but never outweigh the absolute reason regarding that individual, such that, if the absolute reason is in favour of or against an outcome, the combined reason regarding the individual will be as well.

On Subordinate Relation, the comparative reason provided by the welfare gains of an individual enhances the absolute reason regarding that individual. Yet, if the individual’s absolute welfare is negative in an outcome, the contribution of the comparative reason is limited: the combined reason regarding the individual cannot be rendered in favour of the outcome but remains a reason against it. In the Negative Life Case (Table 4), Bel’s negative absolute welfare in C provides only a weak absolute reason against C. Still, the comparative reason provided by Bel’s gain in C relative to B doesn’t render the combined reason regarding Bel in favour of C. It remains a reason against C such that we have overall reason to choose A rather than C. Similarly, the comparative reason provided by an individual’s losses reduces the absolute reason regarding that individual. Yet, if the individual’s absolute welfare is positive, the contribution of the comparative reason is limited: the combined reason regarding the individual cannot be rendered into a reason against the outcome but remains a reason in favour of it. In the Positive Life Case (Table 5), Ali’s positive absolute welfare in A provides only a weak absolute reason for A. Still, the comparative reason provided by Ali’s loss in A relative to B doesn’t render the combined reason regarding Ali a reason against A. It remains a reason in favour of A. Thus, while we still have the strongest reason to realise B, we have a stronger reason to realise A than we have to realise C. Consequently, the Individual Dual Principle paired with Subordinate Relation avoids the Positive and Negative Lives Objections.

While I cannot provide any deeper justification for Subordinate Relation, it appears initially plausible. We have reason to realise an outcome in which individuals lead good lives, even stronger such reason if the individuals gain relative to the alternatives, and weaker such reason if the individuals lose relative to the alternatives. However, no matter how large an individual’s losses in the outcome relative to the alternatives, as long as the individual is well off, we have no combined reason to prevent the individual’s existence. Similarly, we have reason to prevent outcomes in which individuals have bad lives, even stronger such reason if the individuals lose in the outcome relative to the alternatives, and weaker such reason if the individuals gain relative to the alternatives. However, no matter how much an individual gains, as long as the individual is badly off in the outcome, we have no combined reason to create the individual. While this would be so even if the individual is worse off in all alternative outcomes, there would be an even stronger combined reason against all those alternatives regarding that individual. At least initially, therefore, Subordinate Relation seems plausible.

6 The problems of subordinate relation

Subordinate Relation seems initially plausible and avoids the Positive and Negative Lives Objections. However, it has unwelcome features, two of which I want to address. The first concerns how we combine the absolute and comparative reasons if the individual has a neutral life. Subordinate Relation leaves this open. I see two options.

On the one hand, if an individual has neutral welfare in an outcome, the comparative reason regarding the individual might not count at all. This seems in line with Subordinate Relation: comparative reasons enhance and reduce absolute reasons, but since neutral absolute welfare doesn’t provide any absolute reason for or against the outcome, there is nothing that could be enhanced or reduced. Therefore, if the individual’s absolute welfare is neutral in an outcome, the individual’s welfare doesn’t provide any combined reason for or against that outcome. Call this No Comparative Reason.

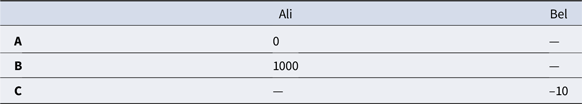

I see two problems with the approach. First, it implies hypersensitivity: small changes to an individual’s welfare can induce large differences for the reason provided by that welfare.

Consider the Zero Case in Table 6 and the Minus-One Case in Table 7. They only differ in Ali’s absolute welfare in A: 0 or –1. Thus, there is only a very small change in Ali’s welfare from one case to the other. The Individual Dual Principle specified by Subordinate Relation and No Comparative Reason, however, yields a huge difference in the assessment of the two cases. In the Minus-One Case, Ali’s slightly negative absolute welfare in A and his loss in A relative to B provide a strong combined reason to prevent A. In the Zero Case, by contrast, we don’t have any such combined reason. Since everything else is equal in the two cases, this transfers to our overall reason. Thus, while we have a very strong overall reason against A in the Minus-One Case, we have, on No Comparative Reason, no overall reason against A in the Zero Case, even though the welfare difference between the two cases is very small. This seems implausible.

Table 6. Zero Case

Table 7. Minus-One Case

Furthermore, on No Comparative Reason, welfare gains and losses don’t count at all for individuals with neutral lives. Neither would the individual’s welfare provide any reason in favour of that outcome if the individual is much better off than in all alternatives, nor would it provide any reason against the outcome if the individual would be much worse off than in all alternatives. Both implications are in tension with the Comparative View and implausible in themselves.

On the other hand, if an individual has neutral welfare in an outcome, the combined reason regarding the individual could be equivalent to the comparative reason. Call this Full Comparative Reason. It slightly stretches the idea of Subordinate Relation. However, that might be justified because it avoids hypersensitivity in the comparison between the Zero Case and the Minus-One Case. In both cases, Ali’s loss in A relative to B provides strong comparative reasons against A that fully matter for the combined reasons regarding Ali: in the Minus-One Case, the comparative reason enhances the absolute reason against A; in the Zero Case, the combined reason is equivalent to the comparative reason. Consequently, there will only be a slight difference in the combined reasons against A in the two cases, which fits the small difference in Ali’s absolute welfare in the A-outcomes.

However, hypersensitivity isn’t avoided for other cases, as we can see by comparing the Zero Case (Table 6) with the Plus-One Case in Table 8. In that case, Ali’s loss in A relative to B barely influences his combined reason. For, according to Subordinate Relation, the combined reason regarding Ali cannot be rendered against A but must remain (very weakly) in favour of A due to Ali’s (barely) good life in A. In the Zero Case, by contrast, since Ali’s absolute welfare is neutral in A, his loss in A relative to B fully counts: it provides a strong comparative and, given Full Comparative Reason, combined reason against A. Again, a small change in Ali’s welfare induces large differences in the combined reasons provided by his welfare. Thus, even on Full Comparative Reason, Subordinate Relation is hypersensitive!

Table 8. Plus-One Case

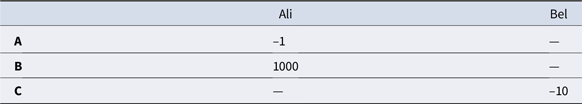

The second problem of Subordinate Relation concerns its incompatibility with the prioritarian idea: welfare gains and losses morally matter more the worse off an individual is. A plausible application of Subordinate Relation will contradict this idea – an idea that is widely spread among consequentialist and non-consequentialists alike.Footnote 18 Let me explain.

To apply Subordinate Relation to the Individual Dual Principle, we need to limit the influence that the comparative reason has on the combined reason regarding each individual: gains cannot provide overall reasons to create bad lives, and losses cannot provide overall reasons to refrain from creating good lives. Those limits could be approached linearly or asymptotically. If they were approached linearly, the comparative reason regarding the individual would count fully up to the limits, but its contribution would be zero after the limits have been reached. Suppose, for example, that an individual has a good life in an outcome but loses so much welfare in that outcome relative to an alternative that the limit has been reached. If the loss were to increase even further, everything else being equal, the strength of the combined reason wouldn’t change. This is implausible and violates an individual version of the Combination Condition: even regarding one individual, an increasing loss of welfare in an outcome should reduce the strength of the combined reason to realise that outcome. Consequently, the limits that Subordinate Relation demands must be approached asymptotically: regarding an individual, the strength of the combined reason approaches zero for positive absolute welfare and increasing negative comparative welfare as well as for negative absolute welfare and increasing positive comparative welfare. Call this the Asymptotic Specification.

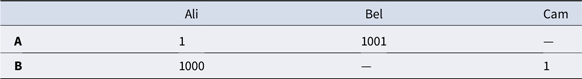

However, Subordinate Relation paired with the Asymptotic Specification contradicts the prioritarian idea. Consider the Priority Case in Table 9. Ali’s and Bel’s losses in B relative to A are equal: they each lose 10 units of welfare. On Subordinate Relation, these losses reduce the combined reasons for A regarding both individuals. On the Asymptotic Specification, furthermore, losses of the same extent reduce the combined reason regarding an individual to a larger extent, the higher the positive absolute welfare level is at which the loss occurs. That’s how the asymptotic function works. Consequently, since Ali’s welfare levels are higher than Bel’s, his loss of 10 units of welfare will reduce the strength of the combined reason regarding Ali to a larger extent than Bel’s loss of 10 units of welfare will reduce the strength of the combined reason regarding Bel. In general, therefore, if the individuals have a good life in an outcome, losses relative to other outcomes don’t matter more the worse off an individual is. Quite the contrary: on the Asymptotic Specification, the loss of the worse-off individual matters less!

Table 9. Priority Case

In sum, if we want to avoid the Positive and Negative Lives Objections, we have reason to believe that, regarding each individual, the comparative reason is subordinate to the absolute reason: the former enhances and reduces but never outweighs the latter. However, Subordinate Relation comes with severe costs. It’s hypersensitive, and the Asymptotic Specification contradicts the prioritarian idea. Maybe other specifications can avoid or mitigate the latter problem, but I doubt that they would still be plausible and able to avoid the Positive and Negative Lives Objections. If they aren’t, we should reject Subordinate Relation.

7 Biting the bullet and the comparative asymmetry

The Positive and Negative Lives Objections suggest adopting Subordinate Relation, but that doesn’t seem tenable either. Which options remain?

We could bite the bullet and reject both objections by arguing that the implications are plausible. The bullet is too big, though. It’s utterly absurd that, in any case, we would have the strongest overall reason to create a bad life even though it’s also possible to create a good life instead, and everything else is equal in these two outcomes.Footnote 19 If both options are available, we should create the good life! Consequently, the Negative Lives Objection is too powerful to dismiss.

However, we could adopt a moderate biting-the-bullet strategy that only retracts the Positive Lives Objection but avoids the Negative Lives Objection. To achieve the latter, we insist that our reasons to provide gains for an individual can never outweigh our reasons against the individual’s existence if the individual has a bad life. We could appeal to

Comparative Asymmetry: While an individual’s welfare loss provides a moral reason to prevent that loss, an individual’s welfare gain doesn’t provide a moral reason to realise that gain.Footnote 20

Given Comparative Asymmetry, we avoid the Negative Lives Objection because an individual’s welfare gains don’t provide any comparative reason that could outweigh the absolute reason to prevent the existence of a miserable life. In the Negative Life Case (Table 4), therefore, Bel’s gain in C relative to B doesn’t provide a reason for C. Since Bel’s welfare is negative in C, we thus have an overall reason to prevent C.

Comparative Asymmetry might strike you as unwarranted. Every asymmetry needs justification, you might say. Furthermore, a loss of welfare in A relative to another outcome B is a gain in B relative to A. Therefore, it seems unclear why gains shouldn’t morally matter while losses do.

However, the fact that gains and losses are the two sides of the same coin provides a reason to accept Comparative Asymmetry. Since every welfare gain in B relative to A is a welfare loss in A relative to B, the individual’s comparative welfare will be taken into account even if we accept Comparative Asymmetry. While the gain no longer counts in favour of B, the loss still counts against A. Therefore, the individual’s welfare still provides a reason to realise B over A. Hence, Comparative Asymmetry seems acceptable, and the Negative Lives Objection provides a powerful argument in its favour.

To repel the Positive Lives Objection, we need to argue that the implication in the Positive Life Case (Table 5) is plausible: we have a stronger overall reason to prevent Ali from existing in A with a slightly good life than to prevent Bel from existing in C with a slightly bad life. The reason is that Ali loses a massive amount of welfare in A. That immense loss renders A overall morally bad – even so bad that we should rather realise C.

Furthermore, by contrast to the Negative Lives Objection, it’s not the case that we have overall the strongest reason to create a miserable life. In the Positive Life Case, we shouldn’t realise C, thereby creating miserable Bel. Rather, we should realise B! It’s merely second-best to create miserable Bel. Furthermore, it’s second-best to do so only in the sense that we have less strong reasons against that than we have against the third alternative. Consequently, only if we didn’t realise the outcome that we have the strongest reason to realise, should we go for the outcome that we have the weakest reason against realising and create a miserable life. That, however, could be justified: at the cost of only a slightly bad life, it prevents the massive welfare loss for Ali that we would have prevented had we realised the outcome that we ought to realise. Hence, we have a somewhat plausible way to repel the Positive Lives Objection.

8 Restricting comparative reasons?

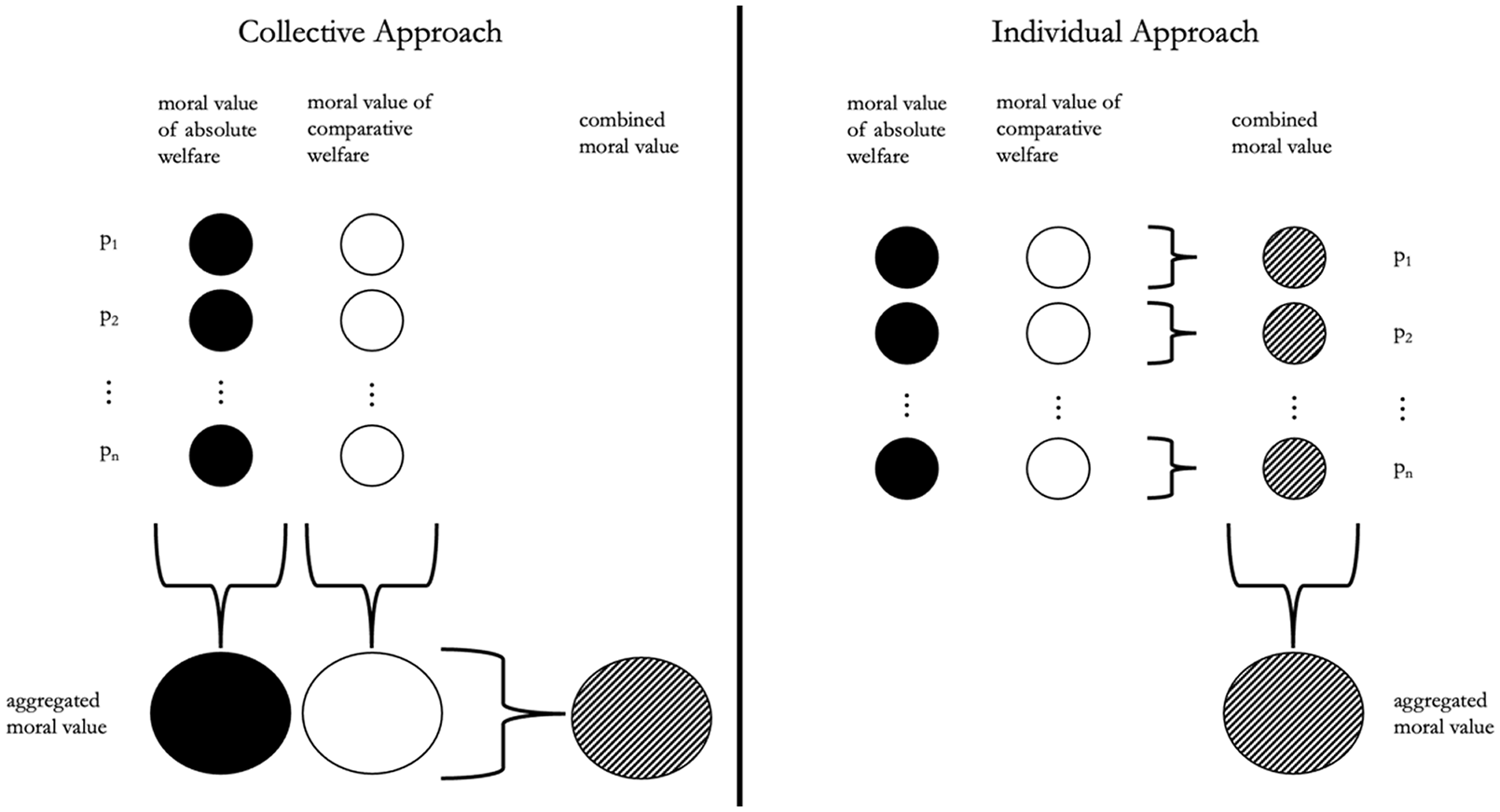

It’s not easy to accept the Positive Lives Objection, though. After all, if the outcomes have further effects, it can be obligatory to create an individual with a bad life rather than an individual with a good but improvable life. The Improvable Life Case in Table 10 illustrates that. Cam’s horrible life renders B the outcome against which we have the strongest overall reason. Consequently, since Ali’s loss in A provides strong reason against A, we have the overall weakest reason against C. Assuming that, if we don’t have overall reason in favour of any outcome, we ought to realise the outcome against which we have the weakest overall reasons, it’s obligatory to create a bad life rather than an improvable good life.

Table 10. Improvable Life Case

The Improvable Life Case is known from discussions of the problem of improvable life avoidance, which I mentioned in section 4.Footnote 21 Might the solutions that have been proposed for that problem help here as well? We cannot simply transfer the respective proposals to our discussion because the authors deny that positive absolute welfare provides reasons to realise it; thus, they don’t solve the Non-Identity Problem. Since that fails to deliver one desideratum of the Dual View, the authors don’t count as its proponents. Nevertheless, their solutions to the problem of improvable life avoidance might help. While different in the details, the common feature of their accounts suggests

Restricted Comparative Reasons: An individual’s comparative welfare in A relative to an alternative B provides a reason for or against A only if the total welfare in A is higher or lower than the total welfare in B.Footnote 22

This claim gives rise to a hybrid of the Collective and Individual Approaches. It considers the comparative reasons regarding one individual as depending on the absolute welfare of the collective. That might seem promising. In the Improvable Life Case (Table 10), Ali’s loss wouldn’t provide any reason against A. Thus, we would have the strongest overall reason to realise A, thereby causing a happy life to exist rather than an unhappy life. On closer inspection, however, it’s not a plausible solution.Footnote 23

First, Restricted Comparative Reason avoids neither the Positive Lives Objection nor the problem that the welfare of happy but improvable lives shouldn’t provide reason against creating them. It does so only in cases in which the total absolute welfare is indeed lower in the alternative. In the Positive Life Case (Table 5), for example, the total welfare in B is not lower than in A. Thus, Ali’s welfare loss provides a reason against A, again rendering our overall reason against A stronger than our overall reason against C. Consequently, we still have reason against creating an improvable life.

Second, the problem to be solved is that we shouldn’t have a reason against creating a good but improvable life. The solution, however, doesn’t target what is going on for people with such lives. For Ali, everything is equal in the Positive Life Case and the Improvable Life Case. Thus, Restricted Comparative Reason doesn’t address the actual problem. The Individual Dual Theory specified by Subordinate Relation did, but only on pain of other problems, as we’ve seen before.

Third, on Restricted Comparative Reasons, comparative welfare doesn’t provide moral reasons in itself but only conditionally: only if A has more total welfare than B can a gain in A relative to B provide a reason in favour of A, and only if A has less total welfare than B can a loss in A relative to B provide a reason against A. As a result, Restricted Comparative Reasons effectively abandons the Comparative View in comparisons of two outcomes. If the total absolute welfare differs in two compared outcomes, the absolute reasons already decide which outcome we have stronger reason to realise, at least if absolute reasons are aggregated by addition. Consequently, the reason-giving force of comparative welfare is reduced to a mere tiebreaker between two outcomes with equal absolute welfare; the comparative welfare can never outweigh differences in total absolute welfare. In the Almost Tied Case shown in Table 11, for example, even though the difference in total absolute welfare is minimal, Ali’s massive welfare loss in A doesn’t provide any reason against A. Restricted Comparative Reason thus violates the Combination Condition and effectively abandons the Dual View in favour of an Absolute View plus some tiebreaking condition in cases with equally strong absolute reasons for two outcomes.

Table 11. Almost Tied Case

In sum, Restricted Comparative Reason isn’t promising. It doesn’t avoid the Positive Lives Objection; it tackles the objection at the wrong point; and it amounts to effectively abandoning the Dual View in comparisons of two outcomes. Given those problems, I tend to adopt the Comparative Asymmetry to avoid the Negative Lives Objection and bite the bullet on the Positive Lives Objection. If we want to uphold the Dual View, we might need to accept that large welfare losses for an individual can provide strong reasons against an outcome – sometimes so strong that they outweigh absolute reasons against the creation of a bad life.

9 Conclusion

In this paper, I’ve explored how to develop a moral theory that is based on the Dual View. The Collective Dual Theory first aggregates the absolute and comparative reasons separately before combining these aggregated reasons across all individuals. The Individual Dual Theory does it the other way around. Both approaches can be specified by different ways of aggregation. The two kinds of reasons can be combined by addition, and their relative strength can be fine-tuned by weights or caps. Since it allows for fine-tuning and avoids the Negligence Objection, the capped model seems promising for the Collective Dual Theory.

The Collective Dual Theory is confronted with the Positive and Negative Lives Objection. The latter can be avoided by accepting Comparative Asymmetry. The former might seem to be averted by solutions to the problem of improvable life avoidance. As we’ve seen, however, the proposed solution doesn’t avoid the Positive Lives Objection and effectively abandons the Dual View in comparisons of two outcomes. To overcome the Positive Lives Objection, we could adopt the Individual Dual Theory paired with Subordinate Relation. This, however, implies hypersensitivity and contradicts the prioritarian idea. Given those costs, it strikes me as plausible to bite the bullet on the Positive Lives Objection: welfare losses matter and, if large enough, even to a degree that we have stronger reasons to avoid those losses than to prevent the existence of a bad life. While surprising, that might be acceptable after all.

The preceding exploration of the dual theory is far from complete. No matter which version we adopt, it needs to be specified by particular views on the aggregation of moral reasons across individuals as well as on the combination of the moral reasons provided by absolute and comparative welfare. This paper has started to do so by investigating some of the promises and pitfalls that we encounter when spelling out a moral theory that is based on the Dual View – the view that both absolute and comparative welfare provide moral reasons.