Policy Significance Statement

Our study introduces an AI-coding technique to reliably and efficiently analyze the content of politicians’ efforts to frame policy statements. This technique can reveal the strategies that policymakers use to convey meaning and emphases in the way they frame their policies and policy agendas. The analysis of such statements is an important step in understanding how these policies are likely to be perceived by the public. It can also reveal differences in framing patterns according to various characteristics of policymakers such as party affiliation and gender. Ultimately, this content analysis technique will facilitate our understanding of how policymakers construct meaning as they attempt to shape public opinion regarding policy initiatives.

1. Introduction

One of the important tasks that politicians face is to communicate their policies and positions to their constituencies using a variety of communication channels such as email, town hall meetings, public appearances, and through the media. In the process, they regularly issue press releases to communicate with their constituents and other stakeholders through the media and by posting them online. Not only are press releases a means that politicians use to generate public support for a candidate’s policies and future elections but they are also a way that citizens can learn about what their representatives are doing and provide feedback and hold policymakers accountable.

By examining press releases, political communication researchers can reveal insights into how politicians communicate with their constituents. For many decades, the primary tools used by communication researchers to analyze the content of political and other forms of communication were quantitative and qualitative analyses conducted by humans. These traditional tools have drawbacks. Quantitative content analysis is not only expensive but is often laborious and time consuming such that coder fatigue can be a serious problem. Qualitative analysis is similarly time consuming, but also adds an additional layer of subjectivity bias to its limitations.

But recent technological innovations have greatly increased the capacity of political communication researchers to monitor and assess policy statements such as press releases. Not only has the Internet provided a conduit for politicians to disseminate policy information but it also facilitates access to those policy statements for citizens and researchers. Moreover, data scraping technologies make the collection of such information much more efficient. At the same time, the rapid development and implementation of artificial intelligence (AI) has led to many innovations in tools that can be used to analyze human-generated messages and information allowing researchers to efficiently analyze and display data to understand important aspects of human behavior, including the communication of public policy.

In essence, our expanding capabilities to capture data coupled with the rapid development of tools to efficiently analyze data are opening up vast unexplored territories for answering consequential research questions that can now be addressed by mass communication researchers. While it is true that there are a multitude of academic disciplines that have been blessed by the promise of access to large datasets, innovations in analytical tools and the ascension of AI, communication researchers may be particularly drawn to the new avenues for inquiry created by these developments. Much of the content in digital trace data is the result of human communication, not only our attempts to engage with other humans but also our attempts to engage with media organizations and other social institutions. As communication researchers, we have an important role to play in studying the content of communication.

The purpose of this paper is to document how AI (in the form of GPT) can be adapted to provide an analytical tool to analyze communication content. We describe our efforts to leverage and validate GPT as a content analysis tool that offers advantages over both human coding and other forms of computer-assisted content analysis. In the process, we link the use of GPT for content analysis to the Semantic Architecture Model (SAM) of media framing (McLeod et al., Reference McLeod, Choung, Su, Kim, Tao, Liu and Lee2022) to unitize content and assess how meaning is embedded in gubernatorial official documents. Additionally, we employ prompt engineering to facilitate the generative AI model in providing an optimized prompt. The importance of this work is underscored by changes in the way that citizens communicate and interact with online media in the 21st Century Digital Age, as well as by the tremendous growth in the storage of massive amounts of digital trace data that are available to researchers, organizations, and institutions. As more and more resources are being dedicated to developing AI technologies, it is important to conduct and share research on how such technologies can be used effectively to analyze the burgeoning array of digital trace data, particularly as it is applied to areas of communication research. The application of these techniques used in this study also sheds light on how politicians, in this case U.S. governors, communicated policy positions with their constituents regarding one of the biggest human challenges of this century, the global COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Research background

2.1. The framing perspective

Our theoretical framework for analyzing message content is rooted in the tradition of “frame analysis.” Content researchers from a variety of different theoretical perspectives have contributed to the development and use of frame analysis to understand how meaning is constructed within communication messages (Entman, Reference Entman1993; Pan and Kosicki, Reference Pan and Kosicki1993). Frame analysis has often focused on the narrative frame of the message as a whole to identify a central narrative framework that emphasizes a particular meaning or way of understanding the information and events presented in a message. From this perspective, researchers often seek to identify common narrative patterns in message construction such as the “the protest paradigm,” which revealed the common characteristics of news coverage of social protests (Chan and Lee, Reference Chan, Lee, Arno and Dissanayake1984; McLeod and Hertog, Reference McLeod, Hertog, Demers and Viswanath1999).

In the interest of developing a cohesive framework for frame analysis, McLeod et al. (Reference McLeod, Choung, Su, Kim, Tao, Liu and Lee2022) articulated the SAM that extends frame analysis beyond narrative frames to examine how smaller units of text can be framed to convey meaning. Following an analogy to house construction, message construction often begins with an abstract blueprint for what the narrative of a message will ultimately look like, but the construction process begins with smaller units. Words with particular suggested meanings are chosen to represent a “concept” frame, the equivalent of bricks in the house analogy. Concepts are used to construct “assertion” frames (the walls), which are then put together into “thematic” frames (the rooms), which are compiled to build the “narrative” frames (the house). Thus, meaning is embedded in the message through construction decisions made at each level, which can collectively amplify the power of the message.

The SAM’s architectural conception of framing can be illustrated with a message drawn from the COVID-19 press releases that were analyzed in this study. This press release was issued by the office of Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer. Though this entire message (i.e., the house) was framed around the public health implications of the COVID-19 pandemic, our procedures (as detailed below) selected direct quotations from governors within each press release for further analysis. These direct quotations (i.e., the room) are built from health-related concept frames (i.e., the bricks), which are combined into health-related assertions (i.e., the walls). In her statement, Governor Whitmer uses public health concepts as the “omicron variant,” “kn95 masks,” and the “MDHHS office” (Michigan Department of Health and Human Services) as she builds public health assertions frames (e.g., “By distributing 10 million highly effective kn95 masks, we can keep families and communities safe.”). Such assertions are combined to form an argument that frames meaning (as conceptualized by Entman, Reference Entman1993) to define, diagnose, evaluate and prescribe solutions to the COVID-19 problem.

Applying the SAM to communication research has several benefits. First, it is helpful in identifying the message components that carry the frames as well as the meanings that are conveyed by those components. Second, once categories are established to capture alternative meanings, the various frames can be used as outcome variables to examine their relationship to antecedent variables such as the characteristics of the creator and the creator’s organizational affiliation. Third, it provides a lens through which one can observe content that helps in making indirect inferences about the intentions of the message creator. Finally, it can be used to isolate important message characteristics that can be manipulated in experimental research examining the influence of message frames on various perceptual, affective, emotional, and behavior outcomes.

2.2. Analyzing message content

The application of the SAM has parallels to quantitative content analysis methodology in terms of “unitization,” one of the basic elements of quantitative content analysis. One of the first choices that must be made in designing content analysis centers on the “unit of analysis,” the basic textual unit that first must be isolated and then coded for the content variables of interest. Each of these variables must be linked to a list of categories that represent an exhaustive and mutually exclusive set of content categories that reflect the important potential content differences between different content units (e.g., the presence or absence of a frame within that unit). Coders could also assess the intensity (or saturation) of the frame within that unit (e.g., a major or minor frame).

Along these lines, the SAM suggests that a given message (such as a newspaper article or a press release) could be unitized and coded in terms of concepts, assertions, arguments and a narrative that work together to convey meaning. Traditionally, communication researchers have employed human coders in the laborious process of quantitative content analysis following social science principles (Holsti, Reference Holsti1969; Krippendorff, Reference Krippendorff1980). Following these procedures, manual coders would be trained to isolate a particular unit for coding according to the categories for each variable that describes that textual unit. Coding content at the concept-level is a relatively simple task but is very time-consuming. As content unitization moves to higher levels (i.e., assertions to thematic arguments to the narrative of the entire message), coding becomes more efficient in terms of coding time, but the judgment becomes more complex as multiple frames may come into play and the saturation level of a particular frame (i.e., how salient the frame is within the unit) varies from one unit to another (often reducing the intercoder agreement of human coding).

Thus, human content coding involves a priori methodological decision regarding unitization that considers implications for validity, reliability, coding time and expense, task complexity, and coder fatigue, while trying to capture textual meaning sufficient to answering research questions and testing hypotheses. These considerations collectively impose potential limitations.

2.3. Computer-assisted content analysis

With the advent of digital media and the explosion of online content, traditional manual content analysis began to face new challenges. The vast amounts of data generated in the digital age necessitated the integration of computational techniques that could efficiently manage and analyze these large datasets (Dakhel et al., Reference Dakhel, Nikanjam, Khomh, Desmarais, Washizaki, Nguyen–Duc, Abrahamsson and Khomh2024). As such, computational methods allow for more efficient sampling and coding of extensive text corpora, enabling the analysis of patterns across large bodies of text (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Zamith and Hermida2013).

Computers assist in analyzing content through various Natural Language Processing (NLP) tasks, leveraging computational power to manage large volumes of text data. They offer several methods for content analysis, allowing communication researchers to systematically process and interpret the large-scale text data. (Chowdhary and Chowdhary, Reference Chowdhary and Chowdhary2020). Below, we identify several of these approaches.

Word frequency analysis: This fundamental method involves counting the occurrences of specific words or phrases within a text corpus. It provides insights into the prominence of certain topics or themes in the dataset, helping to identify areas of focus or concern (Manning and Schütze, Reference Manning and Schütze1999).

Dictionary-based sentiment analysis: This approach employs predefined word lists categorized by positive, negative, and neutral sentiments to evaluate the emotional tone of a text. It facilitates the comprehension of sentiment in communication, offering a structured analysis of public opinion and emotional reactions (Liu, Reference Liu2012).

Topic modeling: Techniques such as Latent Dirichlet Allocation and Structural Topic Modeling (STM) are employed to discover hidden themes in large text corpora (Blei et al., Reference Blei, Ng and Jordan2003). Topic modeling identifies groups of words that frequently appear together, thereby uncovering the underlying topics within the text and offering a nuanced understanding of its thematic structure.

Network Analysis: Network analysis examines the relationships between different entities (e.g., words, individuals, organizations) within a text (Abraham et al., Reference Abraham, Hassanien and Snášel2009; Tabassum et al., Reference Tabassum, Pereira, Fernandes and Gama2018). It helps visualize and understand the connections and structures within communication content, shedding light on the interactions and relationships present in the data.

Traditional machine-learning classification: Machine-learning algorithms can be trained to classify text into predefined categories based on patterns learned from annotated training data (Thai, Reference Thai2022; Parmar et al., Reference Parmar, Chouhan, Raychoudhury and Rathore2023). This method is useful for spam detection and sentiment classification tasks, allowing for efficient categorization and analysis of large text datasets.

By employing these computational methods, researchers can uncover patterns, sentiments, and structures within vast amounts of digital data that might not be easily discernible through manual analysis.

2.4. The use of AI in content analysis

Recently, computer-assisted content analysis has been advanced by developments in AI. Unlike simple keyword matching and topic modeling, AI models employ sophisticated algorithms to delve into the deeper meanings and contexts embedded within a text (Orrù et al., Reference Orrù, Piarulli, Conversano and Gemignani2023). By analyzing syntax, semantics, and context, these models can accurately identify message frames and underlying themes, even in complex and nuanced language. Moreover, AI enables automated and scalable analysis, processing vast amounts of data at speeds far beyond human capabilities (Zhang and Lu, Reference Zhang and Lu2021). Utilizing parallel computing and distributed systems, AI algorithms can swiftly analyze massive text corpora, making large-scale content analysis feasible and efficient. This scalability is instrumental in managing the deluge of digital information generated daily across various platforms and sources. Additionally, AI models engage in dynamic learning, continuously improving their accuracy and adaptability through exposure to new data (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Brantley, Ramamurthy, Misra and Sun2023). Using reinforcement learning and online learning techniques, these models iteratively refine their understanding and predictive capabilities based on real-time feedback. This ongoing learning process ensures that the analysis remains abreast of evolving communication trends, adapting to shifts in language usage, cultural context, and societal dynamic.

Despite these advancements, the use of AI in content analysis also poses several challenges. First, compared to the growing demand for AI in research, there is a scarcity of studies focusing on applying Large Language Models (LLMs) in communication research. This gap results in a lack of clear roadmaps and guides for using state-of-the-art models effectively. Second, while AI models have advanced significantly, they are not infallible. Issues with accuracy and reliability persist, especially when dealing with nuanced or context-specific content. Third, few studies have explored sophisticated framing and content analysis using AI. The typical computer-assisted approaches often simplify the task by identifying whether a certain frame, stance, or sentiment appears (i.e., binary classification) without delving into the more intricate aspects of framing (i.e., the intensity or salience of frames). This study addresses these gaps by offering a practical example of how LLMs (e.g., GPT) can be applied in communication research, particularly for conducting efficient, accurate, and nuanced framing and content analysis.

2.5. Research questions

To advance the use of AI in content analysis, specifically examining how governors construct their messages to communicate policies and agendas, this paper explores the application of GPT to the analysis of gubernatorial statements in COVID-19 relevant press releases. We approach this computational content analysis grounded in framing theory, using GPT to reveal how meaning is embedded in message content. We illustrate this process by using a case study of how we apply GPT to identify message frames across different levels of emphasis. To guide this analysis presented below, we propose the following research questions:

RQ1): How can GPT be used as an effective tool for content analysis in the context of framing research?

RQ2): How do distinct prompts impact the performance of GPT in analyzing message frames?

RQ3): How consistent is GPT with human coders?

RQ4): What are the proportions of each frame used by governors, and how do they vary by party affiliation and gender?

3. Methodology

3.1. Codebook development

We developed a codebook to categorize potential frames that align with major public concerns stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic. Past research has focused on public health and economic threats as major concerns (Kassas and Nayga, Reference Kassas and Nayga2021; Knapp et al., Reference Knapp, Smith and Motta2023; Zhong and Broniatowski, Reference Zhong and Broniatowski2023). Also apparent in public discourse, were concerns about threats to civic life, as participation in schools, churches, and other community events were widely curtailed (Puranik, Reference Puranik2024). Inherent in each of the public health, economic stability and civic vitality frames are assertions that convey different definitions, diagnoses, evaluations, and prescriptions for the problems of COVID-19, reflecting framing components identified by Entman (Reference Entman1993).

Building on these prior studies, we employed STM not only to identify three dominant framing patterns but also to explore additional potential frames that may be present in our dataset beyond the predefined categories. STM is an unsupervised machine learning method to be widely utilized in NLP tasks (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Stewart and Tingley2019). It enables us to efficiently discover hidden thematic structures of a given dataset by providing insights to the prevalence of words and the underlying topics they represent.

We applied standard pre-processing techniques commonly used in STM, including tokenization, stemming, and stopwords removal. Subsequently, we determined the optimal number of topics (K = 10) based on four diagnostic metrics (e.g., held-out likelihood, residuals, semantic coherence, and lower bound). Table 1 presents the top words and representative quotes for each topic. Based on these keywords and a review of the corresponding documents, we assigned interpretive labels to each topic.

Table 1. STM results: Top words and representative press releasesa

a Preprocessing procedures (e.g., tokenization, stemming, and stopwords removal) were applied to the top words and example quotes.

Informed by both existing literature and the empirical results of STM, we synthesized three overarching frame categories: public health, economic stability, and civic vitality. These three categories not only represent central themes of the COVID-19 discourse, but they also fit Entman’s (Reference Entman1993) observation that frames convey problem definition, causal diagnosis, moral judgments, and prescriptive solutions. We illustrate these categories and demonstrate their fit with Entman’s observation using the following examples excerpted from our dataset.

Public health. Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer’s statement that, “COVID-19 has had an immense impact on our state’s healthcare system and its ability to provide quality care in critical conditions,” clearly contains elements of problem definition and causal diagnosis. Her statement that, “as we continue facing COVID, the best thing you can do to protect yourself and your loved ones is to get vaccinated, and if you’re eligible, get your booster shot,” reflects both a moral judgment and a prescriptive solution.

Economic stability. Missouri Governor Michael Parson’s quote, “COVID-19 has had severe impacts on our anticipated economic growth. This is truly unlike anything we have ever experienced before, and we are now expecting significant revenue declines,” illustrates both problem definition and causal diagnosis. Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers’s stated that, “we want small businesses to know that help is on the way. and once we receive federal funds, we aren’t going to wait to get these funds out quickly to help small businesses restock shelves, catch up on bills, rehire and retain workers, and continue to help keep their customers, employees, and our communities safe as we work to bounce back together,” includes elements of problem definition, causal diagnosis, moral judgment and prescriptive solution.

Civic vitality. Kansas Governor Laura Kelly’s quote illustrates problem definition and causal diagnosis: “Opportunities for in-person voting registration are among the many normal routines that have become more difficult as a result of covid-19.” Governor Whitmer statement reflects problem definition, causal diagnosis, moral judgment and prescriptive solution: “My number one priority right now is protecting Michigan families from the spread of covid-19. For the sake of our students, their families, and the more than 100,000 teachers and staff in our state, I have made the difficult decision to close our school facilities for the remainder of the school year,” Subsequently, this well-constructed codebook served as the foundation for manual annotation, in which human coders analyzed several hundred samples to identify the presence of each frame. It also guided the development of GPT-based prompts designed to assess the saturation levels of each frame within press releases.

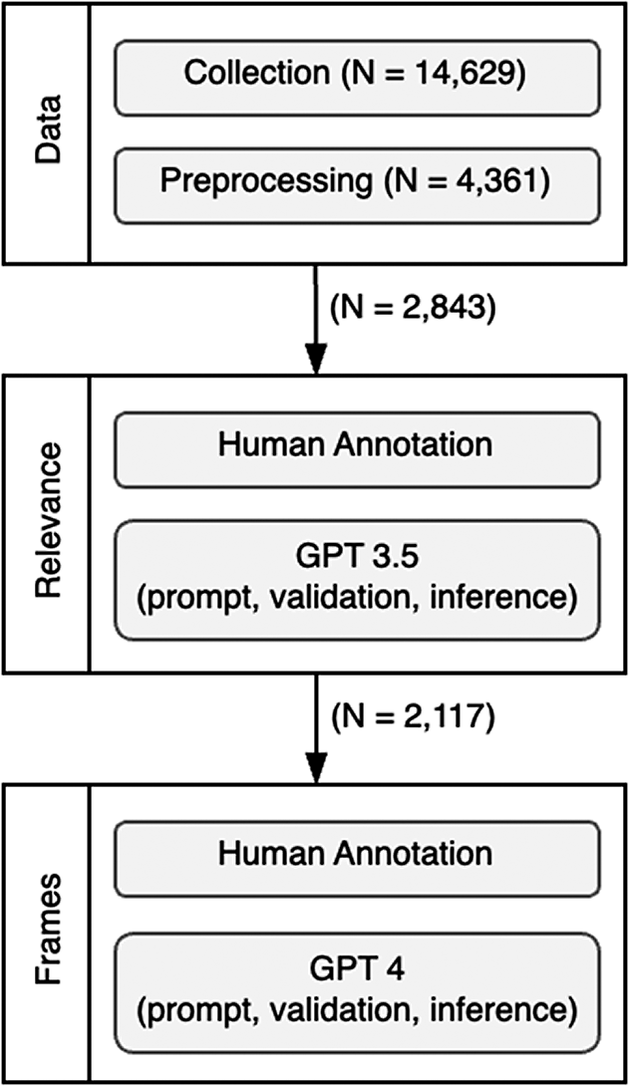

3.2. Data

The AI-coding technique employed in this study can be broadly applied to a whole range of different types of message framing across contexts following the process presented in Figure 1. While the general framework remains consistent, the specific configuration of GPT prompts varies depending on the policy issue context and analytical goals of each study. Following data collection and preprocessing, ChatGPT initially isolates text segments relevant to the study’s focal topic and subsequently annotates message frames in accordance with the specified coding instructions (i.e., prompt). Each stage is iteratively refined through human validation and prompt optimization until satisfactory performance is achieved. The following section illustrates how this AI-coding technique was implemented in our COVID-19 dataset of U.S. governors’ press releases.

Figure 1. Generic stages of the AI-coding technique for message framing.

3.2.1. Data collection

We analyzed the policy statements that appeared in press releases of 12 U.S. governors during the COVID-19 pandemic. These 12 governors were selected from three tiers of four states that were matched based on population size and density, demographic composition, per capita incomes, geographic proximity, and COVID-19 incidence. Each tier included one Democratic female, one Democratic male, one Republican female and one Republican male governor; Tier 1: Gretchen Whitmer (D-MI), Tony Evers (D-WI), Kim Reynolds (R-IA), and Pete Ricketts (R-NB); Tier 2: Laura Kelly (D-KS), John Bel Edwards (D-LA), Kay Ivey (R-AL), and Tate Reeves (R-MS); Tier 3: Michelle Grisham (D-NM), Jared Polis (D-CO), Kristi Noem (R-SD), and Doug Burgum (R-ND).

We began by using ScrapeStorm, a web scraping tool, to gather the official press releases of these governors from state government archives spanning January 2020 to May 2023 (N = 14,629). We then selected only those press releases that contained the words “covid,” “coronavirus,” and “pandemic” yielding a total of 4361 COVID-19 press releases.

3.2.2. Data preprocessing

To unitize for analysis, we isolated direct quotes from each governor presented with the press release to represent how these governors were framing COVID-19 concerns. This was accomplished by identifying three common quotation formats used in press releases: a) “[Statement]” said Governor [Name]; b) “[Statement],” Governor/Gov. [Name] said; and c) “[Statement]” [Name] said/added. Using these patterns, we employed regular expressions in R to systematically isolate these quotes. This process yielded 2843 press releases with their governor quotation passages isolated for coding.

3.3. Human annotation for data cleaning

The above procedures still yielded a small number of governor quotation passages that were irrelevant to COVID-19. As the first step in the process to leverage GPT to recognize and remove these irrelevant quotations (i.e., build a relevance classifier), we coded a random sample of 200 press releases drawn from the preprocessed dataset to identify relevant quotations in which the governor’s statement was related to the pandemic. Press releases were coded as “1” if deemed relevant to COVID-19 and ‘0’ if not (Krippendorff’s alpha = .87). We subsequently used this dataset of 200 human-annotated documents to conduct a validation test of GPT’s identification of COVID-relevant quotations as described below.

3.4. Using GPT for data cleaning

We developed a specific GPT prompt to filter out COVID-irrelevant quotations. The prompt used was: “{Governor’s quotation passage} If the given text is related to the context of COVID-19, answer ‘1’ otherwise ‘0.’ Your answer MUST be either ‘1’ or ‘0’. Do not include your explanation.” Incorporating the phrases, “Your task is” and “You MUST,” resulted in improved model performance (Bsharat et al., Reference Bsharat, Myrzakhan and Shen2023), prompting us to include ‘MUST’ in the query. Additionally, the prompt’s last sentence suppresses the often lengthy explanations GPT provides with its coding decisions.

After preparing this prompt and our sample of 200 quotations, we submitted them to GPT for label generation. Initially, we defined hyperparameters, such as “model,” “messages,” and “temperature.” As the relevance assessment task is relatively simple, we chose to use the cost-effective “GPT 3.5” model (i.e., “gpt-3.5-turbo-0125”). Within GPT’s “messages” parameter, we specified two “role” configurations: “system” with the message “You are the expert of content analysis of COVID-19.” and “user” with our prompt, allowing GPT to generate responses based on the provided role and instructions. Finally, we set the “temperature” of the model to 0, which regulates randomness. Temperature closer to 1 yield more creative but less factual outputs (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Savelka, Oliver and Ashley2023).

To assess the performance of the GPT on this relevance assessment task, we used common metrics: precision, recall, and F1 score (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Shah, Foley, Abhishek, Lukito, Suk, Kim, Sun, Pevehouse and Garlough2019). We achieved high precision (.95), recall (.95), and F1 scores (.95), so no further updates were necessary for the existing prompt. In machine learning, inference refers to the process of applying a trained model to predict outcomes based on previously unseen data (Web3.com Ventures, 2023). For the relevance task, out of 2843 documents, the model categorized 2117 as COVID-relevant governor quotes (typically multiple related assertions) and 726 as irrelevant. These quotes (essentially argument frames from the SAM typology) became the unit that was coded in our frame analysis.

3.5. Human annotation for frame analysis

Following the identification of COVID-19 relevant governor quotation passages, the second stage of annotation involved both human and computer annotation of the presence of our frames of interest. We began with human coding of the presence and intensity of these frames within the quotation passages for later assessment of the GPT analysis. This stage involves more complex analysis as this larger textual unit that potentially constitutes an argument frame provides the capacity for the speaker to co-mingle multiple sub-frames through the incorporation of different assertion and concept frames. That is, the quotation passage might contain elements of all three of COVID-19 frames (i.e., public health, economic stability, and civic vitality). By focusing on indicative concept frames within the quotation passage, we assessed the presence or absence of each of these three frames, as well as their intensity (saturation) within the quotation passage. As such, we coded whether each of these frames had a “major,” “minor,” or “none” presence.

For example, we analyzed the following quotation passage: “It’s great to see Wisconsinites rolling up their sleeves and doing their part to make sure our state and our economy continue to recover,” said Gov. Evers. “The vaccine is safe, effective, and is the best way to keep yourself and your loved ones healthy. I encourage Wisconsinites to drop by our vaccine clinic at the state fair to get your shot–and a free cream puff, too!” Here we coded public health as major, economic stability as minor, and civic vitality as none. In this passage, the public health frame was central to the message, encouraging vaccinations to keep people healthy. Economic stability was identified as a side benefit of people rolling up their sleeves to get vaccinated, while no mention of the civic vitality frame.

After several rounds of training, human coders analyzed a random sample of 200 quotation passages for the presence and intensity of the three frames (Krippendorff’s alpha = .82). The results of this human coding were subsequently used to assess the accuracy of GPT coding.

3.6. Using GPT for frame analysis

One of the main objectives of our study is to compare GPT’s performance in content analysis to that of human coding. Enhancing the accuracy and performance of the LLM in generating outputs requires designing various prompts (instructions) through trial-and-error experimentation until an optimized prompt is developed.

Our prompt development consisted of three rounds of refinement. The initial baseline instruction to analyze the presence and intensity of the three frames in the quotation passage is illustrated in Figure 2. After giving GPT examples of the three types of concept frames, we instructed GPT to identify the thematic argument frames in each passage along with a confidence rating based on the presence of concept indicators. As a cut-off criterion, frames with a confidence rating greater than 5 were labeled as “major,” those scoring between 1 and 5 were classified as “minor,” and frames that did not appear were categorized as “none.”

Figure 2. Initial GPT prompt for frame classification without prompt engineering.

The cost-effective GPT 3.5 model used in the relevance task was not sufficient to conduct the more complex frame analysis, so we opted for the more expensive and more powerful “gpt-4-turbo-preview” model (GPT 4) to conduct the framing analysis. In terms of the parameters and temperature, we retained the same values applied in the relevance assessment task.

Using the initial prompt, the comparison to human coding yielded less than satisfactory results. The precision, recall and F1 scores were: .46, .50, and .47 for the public health frame; .36, .35, and .35 for the economic stability frame; and .59, .46, and .50 for the civic vitality frame. To enhance the model’s efficacy, prompt engineering strategies were considered in subsequent rounds of frame analysis.

3.7. Prompt engineering

Prompt engineering involves deliberate procedures to design and optimize prompts (instructions) to enhance the accuracy of LLMs (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wu, Xie, Kim and Carroll2023). Numerous studies in Computer Science and Engineering have explored and evaluated prompts using diverse strategies and principles (Bsharat et al., Reference Bsharat, Myrzakhan and Shen2023; Hatakeyama-Sato et al., Reference Hatakeyama-Sato, Yamane, Igarashi, Nabae and Hayakawa2023; Velásquez-Henao et al., Reference Velásquez-Henao, Franco-Cardona and Cadavid-Higuita2023).

Past research (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Min, Deng, Shen, Wu, Zettlemoyer and Sun2022; Liyanage et al., Reference Liyanage, Gokani and Mago2023) has supported the efficacy of the “Chain-of-Thought (CoT),” in which prompts are delivered step-by-step. Instead of expecting the LLMs to generate an answer in one step, the task is broken down into smaller, logical steps that guide the model toward the solution. This sequential approach reduces task ambiguity and enhances comprehension and ultimately improves the model’s performance.

Figure 3 illustrates our implementation of three separate prompts designed to guide GPT through a sequential reasoning process. Upon reviewing the initial GPT annotation results, we observed challenges in the model’s ability to predict major frames despite their explicit presence in the text. This difficulty may stem from the lengthiness of press releases. To address this, our revised approach first condensed the entire document into a summary (of 30 words). Then, GPT was asked to identify major frames in the summary, applying the same confidence rating procedure that was used in our initial analysis. Once major frames had been identified, GPT was then asked to examine the original quotation passage to identify minor frames, excluding those already categorized as major. The updated prompt exhibited improved performance in precision, recall and F1 scores: public health (.76, .78, and .75); economic stability (.71, .74, and .69); and civic vitality (.62, .54, and .57).

Figure 3. Second GPT prompt for frame classification.

To further increase the effectiveness of the GPT’s performance, we revised the second prompt to clarify the quantification of frame intensity by specifying more concrete procedures for classifying “major,” “minor” frames. Here, we followed the SAM’s principle that meaning can be embedded in different textual levels to develop a four-step process. First, each document was separated (tokenized) into discrete sentences (at the assertion level). Second, within each sentence, keywords (concept frames) indicative of particular frames (i.e., public health, economic stability, and civic vitality) were isolated. Third, the proportion of sentences containing each frame-relevant keyword was calculated and divided by the total number of sentences. This information was then used to create a code of “major,” “minor,” or “none” to indicate the saturation of particular frames within the message. In addition, we followed examples from Bsharat et al. (Reference Bsharat, Myrzakhan and Shen2023) to further enhance our CoT approach by combining our step-by-step instructions into a single prompt (i.e., instead of making three separate API requests, we consolidated them into a single API request). In the process, we enhanced the clarity of our GPT instructions by employing “#,” “\n,” and alphabetical ordering to distinctly delineate each step: “###Frames and Keywords###,” “###Instruction###,” and “###Question###” (see Figure 4). Our latest prompt yielded satisfactory results in terms of public health (.95 for all three metrics), economic stability (.90, .89, and .89) and civic vitality (.89, .88, and .88).

Figure 4. Final optimized GPT prompt for frame classification.

4. Results and analyses

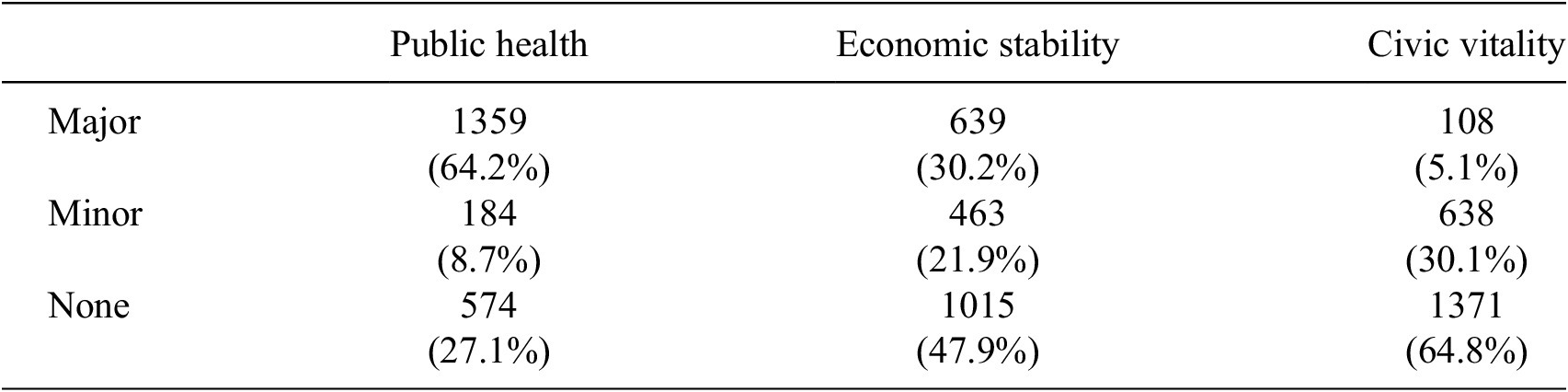

Using this satisfactory prompt, we could use GPT to conduct frame analysis to provide descriptive results of the frequency and intensity of frames found in the 2117 governor quotation passages in our dataset. As illustrated in Table 2, a single passage may contain various combinations of the three frames, occurring at different levels of emphasis. This is largely due to the nature of official government communications, which are typically extensive enough to encompass multiple narratives and emphasize several policy dimensions. For instance, a quotation from Missouri Governor Parson prominently features the civic vitality frame by foregrounding the election as a central theme while also incorporating elements of the public health frame through the presence of minor-level references to health and safety.

Table 2. Examples of governors’ quotes at different levels of the three framesa

a PH = Public Health frame; ES = Economic Stability frame; CL = Civic Life frame.

As one might expect during a pandemic, the public health frame emerged as the most frequently employed element in governors’ press releases, often serving as the primary thematic focus. Compared to the other two frames, the public health frame was less frequently detected at the minor level, suggesting that when political leaders choose to emphasize health-related issues, they tend to communicate using a consistent and comprehensive frame rather than embedding others as secondary themes.

In contrast, approximately 65% of the gubernatorial quotations in press releases did not reference the civic vitality frame. However, when this frame appeared, it was more commonly integrated alongside other major frames rather than functioning as the dominant theme on its own. This suggests that civic life is often used to complement broader policy messages rather than serve as the central focus.

The economic stability frame occupied a middle ground in terms of prevalence and emphasis. Roughly one-third of the quotations featured economic concerns as the primary focus, while over 20% of the quotes included minor keywords related to economic well-being. These patterns indicate variability in how governors employed this frame both as a major and minor theme, which may have been influenced by factors such as their party affiliation and gender (see Table 3).

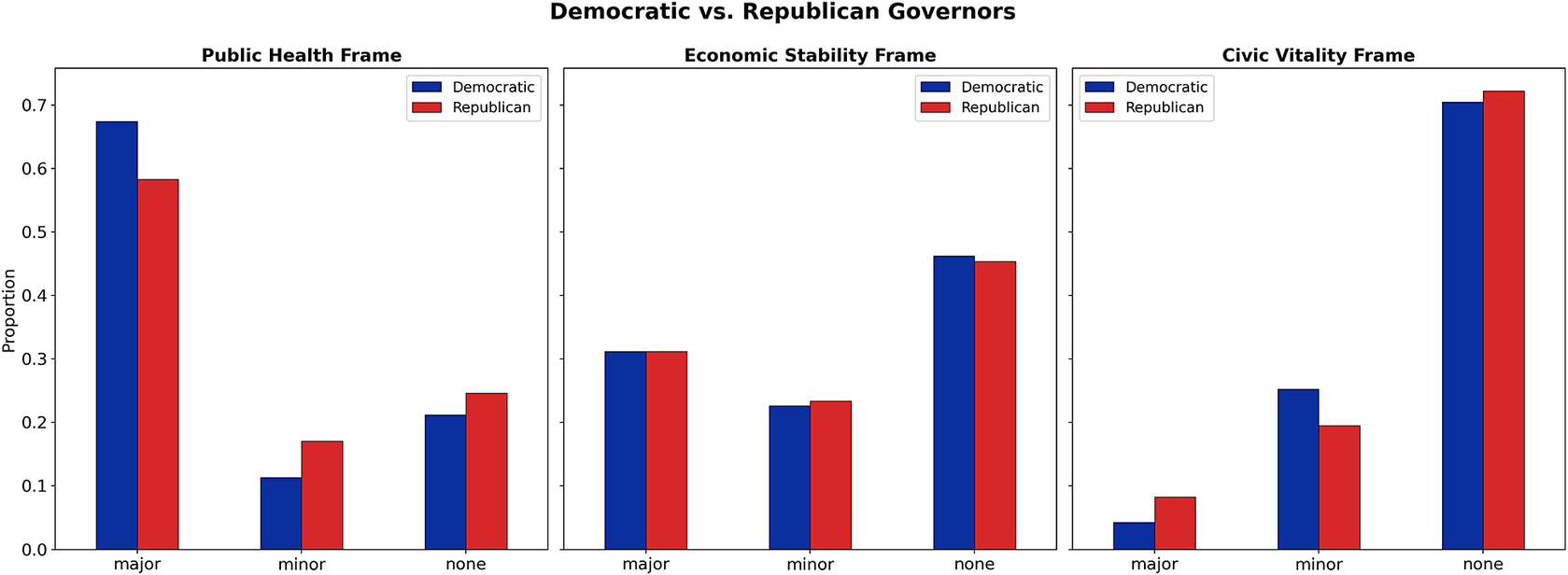

Table 3. Framing analysis results generated by GPT

Democratic governors were more likely to employ the public health frame as a major theme compared to their Republican counterparts (see Figure 5). This result resonates with existing studies that democratic politicians focus more on social welfare, equity, and public health concerns (Conway et al., Reference Conway, Kenski and Wang2015). In contrast, no significant difference was observed between the two parties in the use of the economic stability frame at the major level, which is counter to our expectations that Republican politicians are typically associated with issues related to the economy and national security. With respect to the civic vitality frame, Republican governors more frequently emphasized civic life. However, the overall use of this frame was significantly lower than that of the other two frames.

Figure 5. Frame types and saturation levels by governors’ party affiliation.

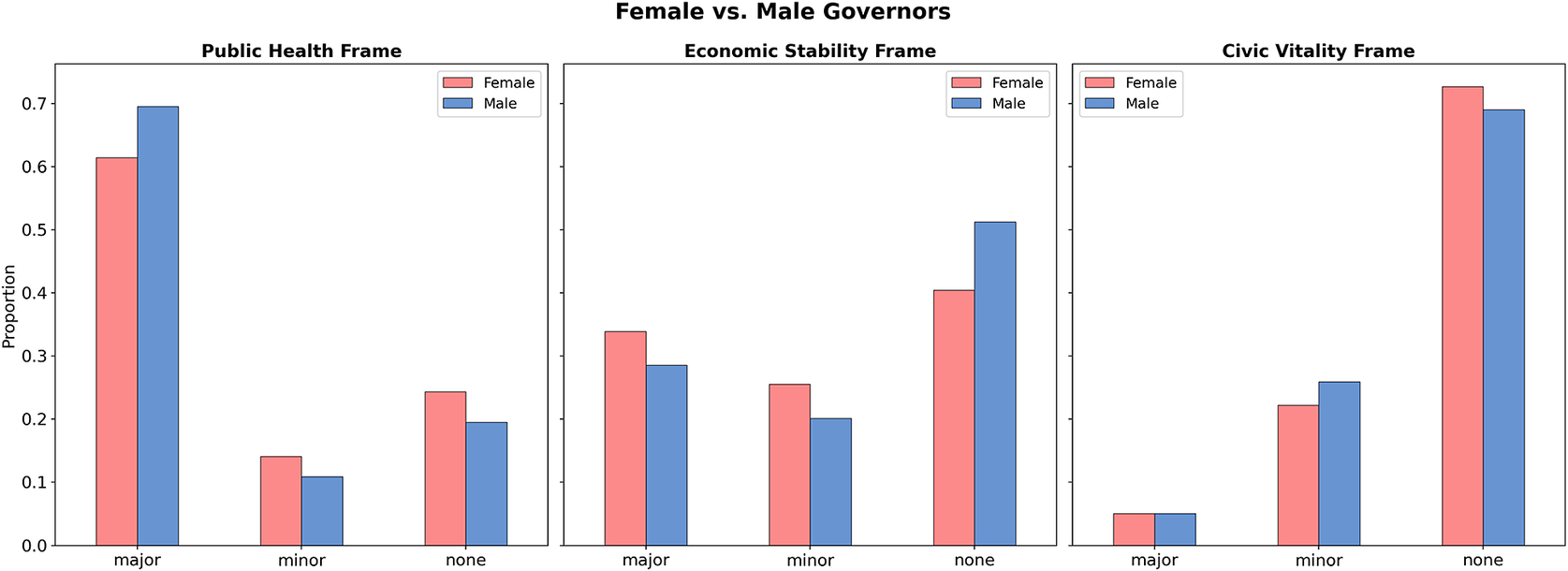

Gender appears to produce a more pronounced difference in framing patterns than party affiliation (see Figure 6). In both the public health and economic stability frame, female and male governors exhibited distinct tendencies in the level of frame usage. Specifically, male governors were more likely to emphasize the public health frame, whereas female governors were more likely to prioritize the economic stability frame than their male counterparts. These findings challenge traditional expectations that associate women with caregiving and public health concerns and men with economic matters. Instead, the results suggest that in the U.S. political sphere, female politicians may adopt less traditional feminine communication styles, while male politicians may also avoid overtly masculine framing to foster broader appeal among potential voters (Jones, Reference Jones2017).

Figure 6. Frame types and saturation levels by governors’ gender.

5. Discussion and conclusion

The purpose of this study was to introduce a meticulous and reliable AI-coding technique for analyzing how policymakers frame their messages. Specifically, we focused on the potential of GPT-driven content analysis in improving our understanding of policy-relevant messaging. This innovative approach allows us to reveal the strategies that politicians use to convey meaning and emphasize their policy positions and agendas.

We have proposed four research questions on AI-assisted content analysis: (1) how politicians and researchers can use cutting-edge AI models to identify specific frames in large-scale government documents, (2) how various prompt engineering techniques can be applied to enhance model performance, (3) how this approach can achieve effectiveness comparable to human coding, and (4) how these methodological procedures can be employed to test theoretical hypotheses such as how the proportions of each frame differ by governors’ party affiliation and gender. Through comprehensive validation that integrated human coders into the process, we achieved satisfactory performance in frame detection assisted by ChatGPT.

Moreover, we have demonstrated the critical role that governors play in shaping public discourse through their press releases, using the COVID-19 pandemic as the contextual framework. This analysis matters because it impacts how political leaders foster citizens’ trust, and hence compliance with response and recovery measures. Additionally, message framing and communication of U.S. governors during crises are influenced by contextual factors. Interestingly, gender, more than party affiliation, shaped governors’ messaging patterns. Our analysis shows that there are notable differences between men and women governors in their pandemic response. Male governors leaned more heavily on public health framing, while female governors emphasized economic stability more than their male counterparts. This challenges our traditional gender expectations and suggests that female politicians may strategically highlight economic competence, whereas male leaders embrace care-oriented messaging to broaden their appeal. Furthermore, we have shown that the complementary use of frames, fostering a sense of collective responsibility, might be central to maintaining public morale and cooperation during challenging times.

Our adaptation of GPT for framing analysis offers a roadmap that guides communication researchers in leveraging cutting-edge computational techniques for research. While our study focuses on the COVID-19 pandemic as a contextual framework, the tool we provided can be extended to any area of political communication, whether analyzing messages of elites or ordinary citizens. This makes our toolkit valuable to framing and other research that deals with large social media datasets.

We illustrated the utility of GPT as an effective content analysis tool by examining how statements by U.S. governors framed their arguments related to the pandemic in official press releases. GPT efficiently performed a series of tasks, including relevance assessment, unitization, and the identification of the presence and intensity of frames, with its performance validated through comparisons to human coding.

Our framing analysis was guided by the Semantic Architecture Model (McLeod et al., Reference McLeod, Choung, Su, Kim, Tao, Liu and Lee2022), which posits that framed meaning can be embedded in textual units, including the author’s selection of concepts, assertions, and arguments that are used to construct a message. As the goal of this analysis was to examine how governors framed COVID-19 to address this issue, we isolated the direct quotations within each press release, focusing on passages that potentially carry what SAM refers to as argument frames. Our initial manual assessment of these passages indicated the presence of multiple COVID-19 frames, suggesting that meaning assessment should include the examination of smaller SAM units assertion and concept frames. Our procedures to guide the GPT application to framing analysis reflect this orientation. After isolating the quotation passages, we inductively as well as deductively developed three categories to represent inherent argument frames (public health, economic stability, and civic vitality) that present different definitional, diagnostic, evaluative, and prescriptive understandings of COVID-19 concerns.

In leveraging GPT to assess these frames, we designed our initial prompt by providing example concept frames for each category and instructing the AI model to identify thematic argument frames and calculate a confidence rating for each identified frame. To improve this initial coding, we used two prompt engineering techniques: isolating the prompt instructions one step at a time and adding a preliminary step of asking GPT to write a 30-word summary of each quotation passage before proceeding to analyze the entire passage. For our final prompt, we added the sentence tokenization instruction (mirroring the SAM’s assertion level framing) and provided specific instructions for calculating the confidence rating. After this final round of prompt revision, we were able to produce satisfactory GPT coding.

The validity of GPT coding was demonstrated by comparing it to reliable human coding using quantitative evaluation metrics (i.e., precision, recall, and F1 scores). For the relevance assessment task, we found that GPT’s prediction was highly consistent with human coding (.95). For the frame analysis task, after several rounds of prompt engineering, we achieved highly satisfactory results, with all three metrics exceeding .8 for public health, economic stability, and civic vitality frames. Additionally, our analysis identified frames that were emphasized or deemphasized by distinguishing the relative salience of major and minor frames. In future research, we will work to leverage ChatGPT to distinguish Entman’s (Reference Entman1993) framing components of problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and treatment recommendations.

Our application of GPT to identify and evaluate message frames has some limitations. Knowledge and techniques based on LLMs are evolving rapidly, which may necessitate further development of our GPT procedures. However, the broader insights identified here, such as the importance of prompt engineering informed by the semantic architecture approach to framing analysis, may be important to future iterations of ChatGPT and other language modeling applications used to analyze communication messages.

Additionally, it is important to consider that an over-reliance on algorithmic approaches can make it challenging to draw meaningful inferences about social phenomena by oversimplifying complex human communication. This may exacerbate the gap between theoretical frameworks and the computational methods used for text analysis (Zamith and Lewis, Reference Zamith and Lewis2015; Baden et al., Reference Baden, Pipal, Schoonvelde and van der Velden2022).

To address these limitations, communication researchers should adopt a balanced, hybrid approach that combines the strengths of traditional qualitative and quantitative content analysis with the power of computational methods. In fact, this study provides an example of such a hybrid approach as we used a simple, inductive qualitative approach to identify COVID-19 frames, and developed a theory-driven GPT-based computational technique that was evaluated by comparisons to traditional quantitative content analysis. Broadly, we believe that fostering collaboration between computational and social science researchers, developing methods that align with theoretical needs, and improving validation techniques are essential for more comprehensive future research. As large language models continue to evolve, future researchers may rely less on prompt engineering and more on selecting or adapting models that are already aligned with complex tasks. However, our findings suggest that prompt design still plays an important role, especially for social science studies that require careful interpretation of meaning, such as framing analysis. Rather than seeing prompt engineering as outdated, we view it as a practical, accessible way to guide model behavior in theory-driven research, especially when fine-tuning or domain-specific training is not feasible (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Tang, Lin and Zhang2023; Woo et al., Reference Woo, Wang, Yung and Guo2024).

While we have demonstrated the utility of GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 for comprehensive content analysis for COVID-19 policy, our study has only focused on these specific models. Acknowledging this limitation, we hope that future work explores the extent to which outcomes can be achieved using other LLMs, such as Claude, LLaMA, or Mistral. This is particularly important as these models may differ in architecture, data training, and interpretability, which might influence their performance with tasks pertaining to framing analysis. Additionally, our study focused on leveraging ChatGPT to perform framing analysis about COVID-19 policy in governors’ press releases. However, we recognize the potential for this approach to be applied across a range of other policy domains. Hence, future scholars are encouraged to explore environmental policy, foreign policy, or economic policies aimed at addressing income inequality. Similarly, the method could be extended to other types of communication messages, including news stories, speeches, and social media posts. Our comprehensive framework can thus be applied to any given combination of policy domain and message type using the same procedures tested in the current study. We believe that once the procedures are validated, the proposed approach could be extended to analyze framing across diverse message formats and policy contexts.

Our approach offers a range of applications centered on policy framing analysis that could assist policymakers and decision-making. Policymakers can investigate how their attempts to frame specific policies, such as those aimed at addressing inequality, are represented across various media platforms. They could also examine differences in policy framing between partisan groups (e.g., Democrats versus Republicans) to uncover potential differences in narratives. Additionally, they could explore the prominence and interpretation of such frames among the general public, particularly as they are expressed on social media. The aforementioned applications are greatly facilitated by data scraping techniques that compile large-scale datasets along with the scalability of AI-assisted framing analysis.

With the growing popularity of AI, future studies should address the ethical implications of AI use in research. First, AI use should be accompanied by careful consideration of potential biases in training datasets. Since the datasets are created by humans and influenced by algorithmic factors, AI outputs may reflect the inherent biases. These biases can lead to a distorted perception of public messages. Therefore, scholars should monitor the AI processes to ensure that training data reflect diversity and inclusion and to address potential biases (Seidenglanz and Baier, Reference Seidenglanz, Baier and Adi2023; Mirek-Rogowska et al., Reference Mirek-Rogowska, Kucza and Gajdka2024). Second, AI use in research should be transparent at every stage of analysis, including data source selection, algorithmic system processing, and results generation (Seidenglanz and Baier, Reference Seidenglanz, Baier and Adi2023).

Taken together, this research carries significant theoretical and practical implications for political communication and framing studies. While our research is situated in a political context, the theoretical advancements can be broadly tested on a variety of topics that involve large textual datasets. We revealed how policymakers curate political messages to influence audience interpretation, hoping to inspire scholars to further explore how communication during uncertain periods can enhance audiences’ ability to form preferences. Methodologically, we leveraged GPT-driven content analysis, laying the groundwork for a more meticulous and effective tool for processing large datasets. This approach offers advances over conventional qualitative and quantitative content analysis methods to the study of political communication content that have long suffered from human fatigue and subjectivity as well as traditional computational analysis that has lacked nuance. Our hope is thus for political communication scholars to leverage the toolkit we provided to explore a wide variety of topics and enhance their understanding of how political leaders communicate with the public.

Data availability statement

The data and code that support the findings of this study are available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository at https://osf.io/a3jmd/.

Author contribution

Conceptualization-Equal: H.K., D.M.M.; Data Curation-Equal: H.K.; Data Curation-Supporting: J.K.; Formal Analysis-Equal: H.K.; Methodology-Equal: H.K.; Validation-Equal: H.K.; Validation-Supporting: J.K.; Visualization-Equal: H.K.; Writing–Original Draft-Equal: H.K., D.M.M.; Writing–Original Draft-Supporting: L.A., L.L.; Writing–Review & Editing-Equal: H.K., L.A., D.M.M.; Writing–Review & Editing-Supporting: J.K.

Funding statement

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

All authors declare that no competing interests exist.

AI statement

In this study, we employed ChatGPT primarily as a large-scale annotation tool to implement our AI-coding technique to classify the complete corpus of governors’ press releases. In addition, we used ChatGPT to support surface-level editorial tasks such as grammar checks, word choice refinement, and minor phrasing adjustments. All conceptual development, analytical decisions, interpretations, and writing were conducted by the authors.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.