1. Introduction

Contra-rotating propellers are propulsion devices where a downstream rotor recovers the azimuthal momentum gained by the flow through the front rotor, with the purpose of generating additional thrust. This strategy is beneficial to the efficiency of propulsion, since in conventional propellers the azimuthal momentum gained by the flow is not utilized to produce thrust and is actually an energetic loss. Furthermore, this is source of unwanted lateral loads, causing additional stresses to the bearings of the device.

Marine propellers are characterized by complex flow physics, populated by tip and hub vortices in interaction. During the last decades this was studied in several works through both physical experiments (Stella et al. Reference Stella, Guj, Di Felice and Elefante2000; Di Felice et al. Reference Di Felice, Di Florio, Felli and Romano2004; Felli & Di Felice Reference Felli and Di Felice2005; Felli et al. Reference Felli, Di Felice, Guj and Camussi2006, Reference Felli, Guj and Camussi2008, Reference Felli, Camussi and Di Felice2011, Felli & Falchi Reference Felli and Falchi2018) and numerical simulations (Muscari, Di Mascio & Verzicco Reference Muscari, Di Mascio and Verzicco2013; Di Mascio, Muscari & Dubbioso Reference Di Mascio, Muscari and Dubbioso2014; Balaras, Schroeder & Posa Reference Balaras, Schroeder and Posa2015; Kumar & Mahesh Reference Kumar and Mahesh2017; Posa et al. Reference Posa, Broglia, Felli, Falchi and Balaras2019, Reference Posa, Broglia and Balaras2022a

, Sun et al. Reference Sun, Wang, Guo, Zhang, Sun and Liu2020, Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wu, Gong and Yang2021a

,

Reference Wang, Wu, Gong and Yangb

). More recently this was also the case of their acoustics (Felli, Grizzi & Falchi Reference Felli, Grizzi and Falchi2014, Reference Felli, Falchi and Dubbioso2015a

,

Reference Felli, Falchi and Dubbiosob

; Lidtke et al. Reference Lidtke, Humphrey and Turnock2016, Reference Lidtke, Lloyd, Lafeber and Bosschers2022; Cianferra et al. Reference Cianferra, Petronio and Armenio2019b

; Tani et al. Reference Tani2020; Wang, Göttsche & Abdel-Maksoud Reference Wang, Göttsche and Abdel-Maksoud2020; Cianferra & Armenio Reference Cianferra and Armenio2021; Kimmerl, Mertes & Abdel-Maksoud Reference Kimmerl, Mertes and Abdel-Maksoud2021; Sezen et al. Reference Sezen, Atlar and Fitzsimmons2021a

,Reference Sezen, Cosgun, Yurtseven and Atlar

b

; Broglia, Felli & Posa Reference Posa, Broglia, Felli, Cianferra and Armenio2022c

, Reference Posa, Felli and Broglia2023; Petris, Cianferra & Armenio Reference Petris, Cianferra and Armenio2022; Sezen & Atlar Reference Sezen and Atlar2022, Reference Sezen and Atlar2023). However, in comparison with conventional propellers, performing both experiments and numerical simulations on contra-rotating marine propellers is more challenging, as demonstrated by the limited information available in the literature, which is actually mainly focused on aeronautical propellers (see the recent review by Filippone (Reference Filippone2023)). For instance, in the realm of numerical studies on contra-rotating marine propellers, most of them focus on the analysis of the global performance for design purposes (Sasaki et al. Reference Sasaki, Murakami, Nozawa, Soejima, Shiraki, Aono, Fujimoto, Funeno, Ishii and Onogi1998; Brizzolara et al. Reference Brizzolara, Tincani and Grassi2007, Reference Brizzolara, Grassi and Tincani2012; Min, Chang & Seo Reference Min, Chang and Seo2009; Grassi et al. Reference Grassi, Brizzolara, Viviani, Savio and Caviglia2010; Su & Kinnas Reference Su and Kinnas2017; Khan et al. Reference Khan, Kundu, Rahman, Haque and Ullah2018; Nouri, Mohammadi & Zarezadeh Reference Nouri, Mohammadi and Zarezadeh2018; Hou et al. Reference Hou, Yin, Hu, Chang, Lin and Wang2021; Tadros, Ventura & Guedes Soares Reference Tadros, Ventura and Guedes Soares2022), while investigations on the flow physics were performed in the framework of only a few works (Paik et al. Reference Paik, Hwang, Jung, Lee, Lee, Ahn and Van2015; Hu et al. Reference Hu, Wang, Zhang, Chang and Zhao2019). In particular, the large-eddy simulation (LES) computations by Hu et al. (Reference Hu, Wang, Zhang, Chang and Zhao2019) on grids consisting of

![]() $O(10^7)$

points were exploited to visualize the interaction between the tip vortices shed by the front and rear propellers of the system, giving rise to a more complex wake topology, in comparison with that usually found downstream of conventional propellers, characterized by the onset of vortex rings, in place of the typical helical topology of the tip vortices shed by axial-flow rotors.

$O(10^7)$

points were exploited to visualize the interaction between the tip vortices shed by the front and rear propellers of the system, giving rise to a more complex wake topology, in comparison with that usually found downstream of conventional propellers, characterized by the onset of vortex rings, in place of the typical helical topology of the tip vortices shed by axial-flow rotors.

The literature on the acoustic emission from contra-rotating marine propellers is even more limited, although more information is available in the field of aeronautical propellers (Blandeau & Joseph Reference Blandeau and Joseph2010; Akkermans, Stuermer & Delfs Reference Akkermans, Stuermer and Delfs2016; Kingan & Parry Reference Kingan and Parry2019, Reference Kingan and Parry2020a

,

Reference Kingan and Parryb

; Parry & Kingan Reference Parry and Kingan2019, Reference Parry and Kingan2020; McKay et al. Reference McKay, Kingan, Go and Jung2021; Chaitanya et al. Reference Chaitanya, Joseph, Prior and Parry2022; Smith, Filippone & Barakos Reference Smith, Filippone and Barakos2022; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Ma, Spieser, Guo, Zhou, Zhong, Zhang and Huang2023; Casagrande Hirono, Robertson & Torija Martinez Reference Casagrande Hirono, Robertson and Torija Martinez2024). However, recent studies pointed out an important difference between aeroacoustics and hydroacoustics of propellers. While in aeroacoustics the quadrupole sound becomes important only in the high-subsonic regime (Glegg & Devenport Reference Glegg and Devenport2017), this is not the case in hydroacoustics (Cianferra et al. Reference Cianferra, Petronio and Armenio2019b

; Cianferra & Armenio Reference Cianferra and Armenio2021). To the authors’ knowledge, the major contribution to the field of the hydroacoustics of contra-rotating marine propellers is attributable to Hu et al. (Reference Hu, Ning, Zhao, Li, Ma, Zhang, Sun, Zou and Lin2021). They utilized detached-eddy simulation on computational meshes up to approximately

![]() $7\times10^6$

cells to reconstruct the acoustic emission in cavitating conditions by exploiting the Ffowcs Williams–Hawkings (FWH) acoustic analogy and the Schnerr–Sauer cavitation model. Besides the expected increase in noise levels, cavitation was found to reduce the directivity of the acoustic field. Unfortunately, a limitation of this study was that noise sources were considered only on the surface of the propeller blades and no information was provided on the wake flow, while the complex wake system generated by this class of propellers is expected to be an important region of additional sources of quadrupole sound.

$7\times10^6$

cells to reconstruct the acoustic emission in cavitating conditions by exploiting the Ffowcs Williams–Hawkings (FWH) acoustic analogy and the Schnerr–Sauer cavitation model. Besides the expected increase in noise levels, cavitation was found to reduce the directivity of the acoustic field. Unfortunately, a limitation of this study was that noise sources were considered only on the surface of the propeller blades and no information was provided on the wake flow, while the complex wake system generated by this class of propellers is expected to be an important region of additional sources of quadrupole sound.

The little number of computational studies on the flow physics of contra-rotating marine propellers is due to the challenge of resolving the flow through multiple parts in relative motion. Meanwhile, the wealth of structures populating this class of propellers requires the use of accurate, eddy resolving techniques exploiting fine resolutions in both space and time, which are computationally expensive. The wake flow of marine propellers is well known to be especially complex, since it is populated by helical tip vortices whose instability is characterized by mutual inductance phenomena, coupling and eventual breakup into smaller turbulent scales, as reported in the relevant literature above. Furthermore, the recent experimental studies by Capone & Alves Pereira (Reference Capone and Alves Pereira2020), Capone, Di Felice & Alves Pereira (Reference Capone, Di Felice and Alves Pereira2021) and Alves Pereira, Capone & Di Felice (Reference Alves Pereira, Capone and Di Felice2021) demonstrated that the flow physics of contra-rotating marine propellers is even more complex, due to the shear occurring between the tip vortices shed by their front and rear rotors, leading to the onset of isolated vortex rings and resulting in a dramatic modification of the wake topology, if compared with conventional propulsion devices. This complex topology was captured in even more detail in our recent numerical studies (Posa et al. Reference Posa, Capone, Alves Pereira, Di Felice and Broglia2024, Reference Posa, Capone, Alves Pereira, Di Felice and Broglia2025b ), where LES on very fine computational grids, consisting of a few billion points, was utilized. The interaction between the tip vortices results in the formation of vortex rings whose branches come alternatively from the tip vortices shed by the front and rear rotors of the system. In addition, the regions of intersection between tip vortices are characterized by the onset of U-shaped vortex lobes, which are locations of intense shear and turbulent stresses, bending alternatively outwards and inwards relative to the wake core. We also verified that in contra-rotating propellers the relative importance of the quadrupole, nonlinear component of sound in the overall acoustic field is reinforced by the intense interaction between tip vortices, if compared with the acoustic signature of conventional propellers (Posa et al. Reference Posa, Capone, Alves Pereira, Di Felice and Broglia2025a ).

In our recent work (Posa et al. Reference Posa, Capone, Alves Pereira, Di Felice and Broglia2025b

), we compared the performance and wake properties of contra-rotating and conventional marine propellers. This work demonstrated that the former are indeed able to achieve better performance than the latter when producing the same thrust, with a rise in the efficiency of propulsion of approximately

![]() $10\,\%$

. We also verified that the flow structures they shed, in particular the tip vortices and the vortex rings arising from their interaction, are less intense than those shed by conventional propellers, since the overall load is split between the two rotors of the system. This was the case for the turbulent stresses as well. These phenomena have the potential of resulting in a weaker acoustic field. This would be beneficial in terms of environmental impact and comfort as well as for the stealth capabilities of marine propulsion for military purposes. Meanwhile, contra-rotating propellers are characterized by the mutual interaction between front and rear rotors and their wake structures, which have instead the potential of reinforcing the levels of radiated sound. This work is aimed at studying the overall balance between the opposite effects of the above phenomena. This analysis is based on the data from LES computations reported in Posa et al. (Reference Posa, Capone, Alves Pereira, Di Felice and Broglia2025b

). The solution of the fluid dynamics is adopted to reconstruct the radiated sound by using the FWH acoustic analogy. It is worth mentioning that the acoustic analysis reported in this study differs from that in Posa et al. (Reference Posa, Capone, Alves Pereira, Di Felice and Broglia2025a

), where the focus was on the relative importance of the different (linear and nonlinear) components of the acoustic signature. In that case, the conventional propellers were working at the same rotational speed as the contra-rotating propeller. We demonstrated that, despite the similar intensity of the tip vortices and loads on each rotor, the interplay between wake systems reinforced the nonlinear sound from the flow field, if compared with the linear one from the propeller blades. Meanwhile, in those conditions the conventional propellers were producing lower levels of overall thrust, if compared with the contra-rotating system. In this study, based on new computations (Posa et al. Reference Posa, Capone, Alves Pereira, Di Felice and Broglia2025b

), the isolated, conventional propellers were simulated at higher values of the rotational speed, with the purpose of producing the same overall thrust as the contra-rotating system. Therefore, the aim of this study is to find out whether a contra-rotating propeller, besides achieving improved efficiency and shedding weaker wake structures, is able to reduce the radiated sound, in comparison with conventional propellers working at conditions of thrust similitude.

$10\,\%$

. We also verified that the flow structures they shed, in particular the tip vortices and the vortex rings arising from their interaction, are less intense than those shed by conventional propellers, since the overall load is split between the two rotors of the system. This was the case for the turbulent stresses as well. These phenomena have the potential of resulting in a weaker acoustic field. This would be beneficial in terms of environmental impact and comfort as well as for the stealth capabilities of marine propulsion for military purposes. Meanwhile, contra-rotating propellers are characterized by the mutual interaction between front and rear rotors and their wake structures, which have instead the potential of reinforcing the levels of radiated sound. This work is aimed at studying the overall balance between the opposite effects of the above phenomena. This analysis is based on the data from LES computations reported in Posa et al. (Reference Posa, Capone, Alves Pereira, Di Felice and Broglia2025b

). The solution of the fluid dynamics is adopted to reconstruct the radiated sound by using the FWH acoustic analogy. It is worth mentioning that the acoustic analysis reported in this study differs from that in Posa et al. (Reference Posa, Capone, Alves Pereira, Di Felice and Broglia2025a

), where the focus was on the relative importance of the different (linear and nonlinear) components of the acoustic signature. In that case, the conventional propellers were working at the same rotational speed as the contra-rotating propeller. We demonstrated that, despite the similar intensity of the tip vortices and loads on each rotor, the interplay between wake systems reinforced the nonlinear sound from the flow field, if compared with the linear one from the propeller blades. Meanwhile, in those conditions the conventional propellers were producing lower levels of overall thrust, if compared with the contra-rotating system. In this study, based on new computations (Posa et al. Reference Posa, Capone, Alves Pereira, Di Felice and Broglia2025b

), the isolated, conventional propellers were simulated at higher values of the rotational speed, with the purpose of producing the same overall thrust as the contra-rotating system. Therefore, the aim of this study is to find out whether a contra-rotating propeller, besides achieving improved efficiency and shedding weaker wake structures, is able to reduce the radiated sound, in comparison with conventional propellers working at conditions of thrust similitude.

This manuscript is structured as follows: the methodology, including both the solution of the fluid dynamics and the FWH acoustic analogy, is discussed in § 2, the set-up for both LES computations and the reconstruction of the acoustic field in § 3, the results of both fluid dynamics and hydroacoustics in § 4 and the conclusions of the study in § 5.

2. Methodology

2.1. Fluid dynamics

The fluid dynamics of the problem was reconstructed through the solution of the filtered Navier–Stokes equations (NSE) for incompressible flows:

\begin{align} {\partial \widetilde {u}_i \over \partial t} + {\partial \widetilde {u}_i \widetilde {u}_{\!j} \over \partial x_{\!j} } &= - {\partial\! \tilde {p} \over \partial x_i} - {\partial \tau _{\textit{ij}} \over \partial x_{\!j}} + {1 \over \textit{Re}} {\partial ^2 \widetilde {u}_i \over \partial x_{\!j}^2} + f_i, \;\;\;i,j=1,2,3. \end{align}

\begin{align} {\partial \widetilde {u}_i \over \partial t} + {\partial \widetilde {u}_i \widetilde {u}_{\!j} \over \partial x_{\!j} } &= - {\partial\! \tilde {p} \over \partial x_i} - {\partial \tau _{\textit{ij}} \over \partial x_{\!j}} + {1 \over \textit{Re}} {\partial ^2 \widetilde {u}_i \over \partial x_{\!j}^2} + f_i, \;\;\;i,j=1,2,3. \end{align}

In the equations above,

![]() $x_i$

and

$x_i$

and

![]() $t$

represent the coordinate in space along the direction

$t$

represent the coordinate in space along the direction

![]() $i$

and time, respectively. The quantities

$i$

and time, respectively. The quantities

![]() $\widetilde {u}_i$

and

$\widetilde {u}_i$

and

![]() $ \tilde {p}$

are the filtered velocity component in the direction

$ \tilde {p}$

are the filtered velocity component in the direction

![]() $i$

and the filtered pressure. The tensor

$i$

and the filtered pressure. The tensor

![]() $\tau _{\textit{ij}}$

represents the subgrid stresses (SGS),

$\tau _{\textit{ij}}$

represents the subgrid stresses (SGS),

![]() $\textit{Re}$

is the Reynolds number and

$\textit{Re}$

is the Reynolds number and

![]() $f_i$

is the component in the direction

$f_i$

is the component in the direction

![]() $i$

of the forcing terms, utilized in the framework of an immersed boundary (IB) methodology to represent the action of the bodies on the flow. The Reynolds number is defined as

$i$

of the forcing terms, utilized in the framework of an immersed boundary (IB) methodology to represent the action of the bodies on the flow. The Reynolds number is defined as

![]() $\textit{Re}=\mathcal{VL}\rho /\mu =\mathcal{VL}/\nu$

, where

$\textit{Re}=\mathcal{VL}\rho /\mu =\mathcal{VL}/\nu$

, where

![]() $\mathcal{V}$

and

$\mathcal{V}$

and

![]() $\mathcal{L}$

are the reference velocity and length scales utilized to non-dimensionalize the NSE, while

$\mathcal{L}$

are the reference velocity and length scales utilized to non-dimensionalize the NSE, while

![]() $\rho$

,

$\rho$

,

![]() $\mu$

and

$\mu$

and

![]() $\nu$

are the density, dynamic viscosity and kinematic viscosity of the fluid, respectively.

$\nu$

are the density, dynamic viscosity and kinematic viscosity of the fluid, respectively.

The SGS tensor,

![]() $\tau _{\textit{ij}}=\widetilde {u_i u_{\!j}} - \widetilde {u}_i \widetilde {u}_{\!j}$

, comes from filtering the NSE and in particular its nonlinear terms. It represents the action of the unresolved scales, smaller than the filter, on the larger, resolved ones. Practically, the NSE are filtered since they are resolved on a computational grid that is coarser than the smallest scale of the flow, that is the Kolmogorov scale. This is always the case for problems of interest in engineering, since performing a direct numerical simulation on this class of flows, which means resolving all dissipative scales, is prohibitively expensive and today still unfeasible even on the most powerful supercomputers. Therefore, the LES methodology requires the SGS tensor to be modelled for closing the problem of turbulence. In this study, as typical in LES approaches, this modelling is achieved by exploiting the Boussinesq hypothesis, assuming that the deviatoric part of the SGS tensor,

$\tau _{\textit{ij}}=\widetilde {u_i u_{\!j}} - \widetilde {u}_i \widetilde {u}_{\!j}$

, comes from filtering the NSE and in particular its nonlinear terms. It represents the action of the unresolved scales, smaller than the filter, on the larger, resolved ones. Practically, the NSE are filtered since they are resolved on a computational grid that is coarser than the smallest scale of the flow, that is the Kolmogorov scale. This is always the case for problems of interest in engineering, since performing a direct numerical simulation on this class of flows, which means resolving all dissipative scales, is prohibitively expensive and today still unfeasible even on the most powerful supercomputers. Therefore, the LES methodology requires the SGS tensor to be modelled for closing the problem of turbulence. In this study, as typical in LES approaches, this modelling is achieved by exploiting the Boussinesq hypothesis, assuming that the deviatoric part of the SGS tensor,

![]() $\tau _{\textit{ij}}^d$

, and the rate-of-strain tensor of the resolved velocity field,

$\tau _{\textit{ij}}^d$

, and the rate-of-strain tensor of the resolved velocity field,

![]() $\widetilde {S}_{\textit{ij}}$

, are aligned,

$\widetilde {S}_{\textit{ij}}$

, are aligned,

where

![]() $\delta _{\textit{ij}}$

is the Kronecker delta,

$\delta _{\textit{ij}}$

is the Kronecker delta,

![]() $\tau _{kk}$

is the trace of the SGS tensor and

$\tau _{kk}$

is the trace of the SGS tensor and

![]() $\nu _t$

is the so-called eddy-viscosity. By using this hypothesis the problem of turbulence closure is reduced from modelling a symmetric tensor,

$\nu _t$

is the so-called eddy-viscosity. By using this hypothesis the problem of turbulence closure is reduced from modelling a symmetric tensor,

![]() $\tau _{\textit{ij}}$

, to modelling a scalar quantity,

$\tau _{\textit{ij}}$

, to modelling a scalar quantity,

![]() $\nu _t$

, which is a function of both space and time. In this study, as in our earlier works on marine propellers (Posa & Broglia Reference Posa and Broglia2022; Posa Reference Posa2022a

,

Reference Posab

, Reference Posa2023), the wall-adaptive local eddy-viscosity model by Nicoud & Ducros (Reference Nicoud and Ducros1999) was adopted. This features a series of convenient properties. For instance, it is able to switch-off in regions of pure strain, as in the presence of laminar gradients. It is also designed to reproduce the correct behaviour of the eddy viscosity in the vicinity of solid walls, scaling as the cube power of the distance from the wall. In addition, in our experience it is an inexpensive model, requiring only a few percent of the overall computational cost of the simulations. Therefore, in the present study the eddy-viscosity was computed at each location of the computational domain as

$\nu _t$

, which is a function of both space and time. In this study, as in our earlier works on marine propellers (Posa & Broglia Reference Posa and Broglia2022; Posa Reference Posa2022a

,

Reference Posab

, Reference Posa2023), the wall-adaptive local eddy-viscosity model by Nicoud & Ducros (Reference Nicoud and Ducros1999) was adopted. This features a series of convenient properties. For instance, it is able to switch-off in regions of pure strain, as in the presence of laminar gradients. It is also designed to reproduce the correct behaviour of the eddy viscosity in the vicinity of solid walls, scaling as the cube power of the distance from the wall. In addition, in our experience it is an inexpensive model, requiring only a few percent of the overall computational cost of the simulations. Therefore, in the present study the eddy-viscosity was computed at each location of the computational domain as

\begin{align} \nu _t= (C_w \varDelta )^2 {\left ( \widetilde {\mathcal{G}}_{\textit{ij}}^d \widetilde {\mathcal{G}}_{\textit{ij}}^d \right )^{3/2} \over \left ( \widetilde {S}_{\textit{ij}} \widetilde {S}_{\textit{ij}} \right )^{5/2} + {\left ( \widetilde {\mathcal{G}}_{\textit{ij}}^d \widetilde {\mathcal{G}}_{\textit{ij}}^d \right )^{5/4}}}, \;\;\;i,j=1,2,3, \end{align}

\begin{align} \nu _t= (C_w \varDelta )^2 {\left ( \widetilde {\mathcal{G}}_{\textit{ij}}^d \widetilde {\mathcal{G}}_{\textit{ij}}^d \right )^{3/2} \over \left ( \widetilde {S}_{\textit{ij}} \widetilde {S}_{\textit{ij}} \right )^{5/2} + {\left ( \widetilde {\mathcal{G}}_{\textit{ij}}^d \widetilde {\mathcal{G}}_{\textit{ij}}^d \right )^{5/4}}}, \;\;\;i,j=1,2,3, \end{align}

where

![]() $\widetilde {\mathcal{G}}_{\textit{ij}}^d$

is the deviatoric part of the square of the velocity gradient tensor of the resolved (filtered) field, which includes both contributions of rotation and deformation tensors. In (2.4) the quantity

$\widetilde {\mathcal{G}}_{\textit{ij}}^d$

is the deviatoric part of the square of the velocity gradient tensor of the resolved (filtered) field, which includes both contributions of rotation and deformation tensors. In (2.4) the quantity

![]() $C_w=0.5$

is a constant, while

$C_w=0.5$

is a constant, while

![]() $\varDelta$

is the local size of the filter, that is the local size of the computational grid, computed as the cube root of the local grid cell.

$\varDelta$

is the local size of the filter, that is the local size of the computational grid, computed as the cube root of the local grid cell.

As discussed above, the quantity

![]() $f_i$

in (2.2) is utilized in the framework of an IB methodology to represent the action of the bodies on the flow. This strategy allows separating the discretization of the computational domain from the discretization of the bodies immersed within the flow. Therefore, while the former is achieved by using a regular Eulerian grid, which is not required to conform to the geometry of the bodies, the latter utilizes Lagrangian grids representing the surface of the immersed boundaries. The Lagrangian grids are ‘immersed’ within the Eulerian grid, free to move across its cells, and the interaction between the bodies and the flow is taken into account by means of the forcing term

$f_i$

in (2.2) is utilized in the framework of an IB methodology to represent the action of the bodies on the flow. This strategy allows separating the discretization of the computational domain from the discretization of the bodies immersed within the flow. Therefore, while the former is achieved by using a regular Eulerian grid, which is not required to conform to the geometry of the bodies, the latter utilizes Lagrangian grids representing the surface of the immersed boundaries. The Lagrangian grids are ‘immersed’ within the Eulerian grid, free to move across its cells, and the interaction between the bodies and the flow is taken into account by means of the forcing term

![]() $f_i$

. In IB methods the elements of the Eulerian grid are separated in ‘solid’, ‘fluid’ and ‘interface’ points, based on their position relative to the Lagrangian grids representing the bodies. The solid points are those located inside the immersed boundaries. The fluid points are those placed outside and having no neighbouring solid points along any coordinate direction. The interface points are all remaining points of the Eulerian grid, placed at the boundary between the solid and fluid regions of the computational domain. The forcing term

$f_i$

. In IB methods the elements of the Eulerian grid are separated in ‘solid’, ‘fluid’ and ‘interface’ points, based on their position relative to the Lagrangian grids representing the bodies. The solid points are those located inside the immersed boundaries. The fluid points are those placed outside and having no neighbouring solid points along any coordinate direction. The interface points are all remaining points of the Eulerian grid, placed at the boundary between the solid and fluid regions of the computational domain. The forcing term

![]() $f_i$

is equal to zero at the fluid points, while at the interface and solid points it is given by the following expression:

$f_i$

is equal to zero at the fluid points, while at the interface and solid points it is given by the following expression:

where

![]() $\mathcal{U}_i$

is the velocity condition to be enforced at the particular solid or interface point,

$\mathcal{U}_i$

is the velocity condition to be enforced at the particular solid or interface point,

![]() $\widetilde {u}_i$

is the local flow velocity,

$\widetilde {u}_i$

is the local flow velocity,

![]() $\Delta t$

is the step of advancement in time of the numerical solution, while

$\Delta t$

is the step of advancement in time of the numerical solution, while

![]() $\mathcal{RHS}_i$

is the sum of the convective, viscous, pressure gradient and SGS terms, all computed explicitly from the previous time level. The value of

$\mathcal{RHS}_i$

is the sum of the convective, viscous, pressure gradient and SGS terms, all computed explicitly from the previous time level. The value of

![]() $\mathcal{U}_i$

at the solid points is given by the velocity of the body where the particular point is located. Instead, for the interface points,

$\mathcal{U}_i$

at the solid points is given by the velocity of the body where the particular point is located. Instead, for the interface points,

![]() $\mathcal{U}_i$

comes from a linear reconstruction of the velocity field along the direction normal to the Lagrangian grid representing the IB. This reconstruction utilizes as boundary conditions the no-slip requirement on the surface of the body and the solution at the fluid points in the vicinity of the particular interface point. More details on the particular implementation of the IB method can be found in the works by Balaras (Reference Balaras2004) and Yang & Balaras (Reference Yang and Balaras2006).

$\mathcal{U}_i$

comes from a linear reconstruction of the velocity field along the direction normal to the Lagrangian grid representing the IB. This reconstruction utilizes as boundary conditions the no-slip requirement on the surface of the body and the solution at the fluid points in the vicinity of the particular interface point. More details on the particular implementation of the IB method can be found in the works by Balaras (Reference Balaras2004) and Yang & Balaras (Reference Yang and Balaras2006).

The NSE were resolved on a staggered cylindrical grid, using second-order central differences for the discretization of the derivatives in space. In the following, the radial, azimuthal and axial coordinates of the cylindrical reference frame will be indicated as

![]() $r$

,

$r$

,

![]() $\vartheta$

and

$\vartheta$

and

![]() $z$

, respectively, and the relevant velocity components as

$z$

, respectively, and the relevant velocity components as

![]() $u$

,

$u$

,

![]() $v$

and

$v$

and

![]() $w$

. Note also that only resolved quantities will be considered. Therefore, for convenience, the symbol of the filter operator

$w$

. Note also that only resolved quantities will be considered. Therefore, for convenience, the symbol of the filter operator

![]() $\widetilde {\boldsymbol{\cdot }}$

will be omitted hereafter. The advancement in time utilized a fractional-step method (Van Kan Reference Van Kan1986). All radial and axial convective, viscous and SGS terms of the momentum equation were discretized in time explicitly by using the three-step Runge–Kutta scheme. For stability, the azimuthal terms were instead discretized implicitly by using the Crank–Nicolson scheme, to avoid computationally expensive restrictions on the step of advancement in time of the numerical solution, arising at the smallest radial coordinates of the cylindrical grid. The hepta-diagonal Poisson problem resulting from the enforcement of the continuity condition was decomposed into a series of penta-diagonal problems by means of trigonometric transformations along the periodic azimuthal direction. These were efficiently inverted using a direct solver (Rossi & Toivanen Reference Rossi and Toivanen1999). The overall NSE solver was demonstrated second-order accurate in both space and time (Balaras Reference Balaras2004; Yang & Balaras Reference Yang and Balaras2006) and was successfully utilized in a number of studies on marine propellers (Posa et al. Reference Posa, Broglia, Felli, Falchi and Balaras2019, Reference Posa, Broglia and Balaras2022a

, Reference Posa, Capone, Alves Pereira, Di Felice and Broglia2024, Reference Posa, Capone, Alves Pereira, Di Felice and Broglia2025b

; Posa & Broglia Reference Posa and Broglia2022; Posa Reference Posa2022a

,

Reference Posab

, Reference Posa2023), including also comparisons with physical measurements.

$\widetilde {\boldsymbol{\cdot }}$

will be omitted hereafter. The advancement in time utilized a fractional-step method (Van Kan Reference Van Kan1986). All radial and axial convective, viscous and SGS terms of the momentum equation were discretized in time explicitly by using the three-step Runge–Kutta scheme. For stability, the azimuthal terms were instead discretized implicitly by using the Crank–Nicolson scheme, to avoid computationally expensive restrictions on the step of advancement in time of the numerical solution, arising at the smallest radial coordinates of the cylindrical grid. The hepta-diagonal Poisson problem resulting from the enforcement of the continuity condition was decomposed into a series of penta-diagonal problems by means of trigonometric transformations along the periodic azimuthal direction. These were efficiently inverted using a direct solver (Rossi & Toivanen Reference Rossi and Toivanen1999). The overall NSE solver was demonstrated second-order accurate in both space and time (Balaras Reference Balaras2004; Yang & Balaras Reference Yang and Balaras2006) and was successfully utilized in a number of studies on marine propellers (Posa et al. Reference Posa, Broglia, Felli, Falchi and Balaras2019, Reference Posa, Broglia and Balaras2022a

, Reference Posa, Capone, Alves Pereira, Di Felice and Broglia2024, Reference Posa, Capone, Alves Pereira, Di Felice and Broglia2025b

; Posa & Broglia Reference Posa and Broglia2022; Posa Reference Posa2022a

,

Reference Posab

, Reference Posa2023), including also comparisons with physical measurements.

2.2. Acoustic analysis

In the present study the acoustic field is reconstructed from the LES solution of the flow by exploiting the FWH acoustic analogy (Ffowcs Williams & Hawkings Reference Ffowcs Williams and Hawkings1969). This assumes that the hydroacoustics has a negligible influence on the fluid dynamics. Therefore, it is possible to first resolve the fluid dynamics without including the hydroacoustics. Then, the hydroacoustics can be reconstructed in postprocessing from the fluid dynamics by using the wave theory, considering the fluid particles as a collection of acoustic sources and assuming that the propagation of the acoustic waves occurs within a homogeneous, unbounded medium. In this work, the acoustic pressure,

![]() $\langle p \rangle$

, was computed by considering the FWH equation in integral form:

$\langle p \rangle$

, was computed by considering the FWH equation in integral form:

\begin{align} 4 \pi \langle p \rangle (\boldsymbol{x},t) &= {\partial \over \partial t} \int _{\mathcal{S}} \left [ {\rho ^* v_n \over r |1-M_r|} \right ]_{\mathcal{T}} {\rm d}S + {1 \over c}{\partial \over \partial t} \int _{\mathcal{S}} \left [ {p' \widehat {n}_i \widehat {r}_i \over r |1-M_r|} \right ]_{\mathcal{T}} {\rm d}S \nonumber \\ &\quad + \int _{\mathcal{S}} \left [ {p' \widehat {n}_i \widehat {r}_i \over r^2 |1-M_r|} \right ]_{\mathcal{T}} {\rm d}S + {1 \over c^2}{\partial ^2 \over \partial t^2} \int _{\mathcal{V}} \left [ {T_{\textit{rr}} \over r |1-M_r|} \right ]_{\mathcal{T}} {\rm d}V \nonumber \\ &\quad + {1 \over c}{\partial \over \partial t} \int _{\mathcal{V}} \left [ {3T_{\textit{rr}} -T_{kk} \over r^2 |1-M_r|} \right ]_{\mathcal{T}} {\rm d}V+ \int _{\mathcal{V}} \left [ {3T_{\textit{rr}} -T_{kk} \over r^3 |1-M_r|} \right ]_{\mathcal{T}} {\rm d}V, \;\;\; i=1,2,3. \end{align}

\begin{align} 4 \pi \langle p \rangle (\boldsymbol{x},t) &= {\partial \over \partial t} \int _{\mathcal{S}} \left [ {\rho ^* v_n \over r |1-M_r|} \right ]_{\mathcal{T}} {\rm d}S + {1 \over c}{\partial \over \partial t} \int _{\mathcal{S}} \left [ {p' \widehat {n}_i \widehat {r}_i \over r |1-M_r|} \right ]_{\mathcal{T}} {\rm d}S \nonumber \\ &\quad + \int _{\mathcal{S}} \left [ {p' \widehat {n}_i \widehat {r}_i \over r^2 |1-M_r|} \right ]_{\mathcal{T}} {\rm d}S + {1 \over c^2}{\partial ^2 \over \partial t^2} \int _{\mathcal{V}} \left [ {T_{\textit{rr}} \over r |1-M_r|} \right ]_{\mathcal{T}} {\rm d}V \nonumber \\ &\quad + {1 \over c}{\partial \over \partial t} \int _{\mathcal{V}} \left [ {3T_{\textit{rr}} -T_{kk} \over r^2 |1-M_r|} \right ]_{\mathcal{T}} {\rm d}V+ \int _{\mathcal{V}} \left [ {3T_{\textit{rr}} -T_{kk} \over r^3 |1-M_r|} \right ]_{\mathcal{T}} {\rm d}V, \;\;\; i=1,2,3. \end{align}

In (2.6) the acoustic pressure is a function of the coordinates of the receiver in both space,

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}$

, and time,

$\boldsymbol{x}$

, and time,

![]() $t$

. The integrals on the right-hand side are computed on the surface

$t$

. The integrals on the right-hand side are computed on the surface

![]() $\mathcal{S}$

(linear component of sound) and within the volume

$\mathcal{S}$

(linear component of sound) and within the volume

![]() $\mathcal{V}$

(nonlinear component of sound). In this study, the direct formulation of the acoustic analogy is adopted, due to its benefits in terms of accuracy, relative to the more typical permeable formulation (Di Francescantonio Reference Di Francescantonio1997), which is often preferred, since computationally less expensive. In the framework of the direct formulation, the surface and volume integrals on the right-hand side of (2.6) are computed on the surface of the bodies immersed within the flow and across a control volume encompassing all fluid regions of the computational domain populated by acoustic sources (vorticity, turbulence). This approach, although computationally more expensive than the permeable formulation, is able to provide more detailed information on the acoustic field, since it allows separating the different components of sound, as reported in the following analysis of the results in § 4. It is worth mentioning that the hydrophones (receivers) considered for the reconstruction of the acoustic field cannot be placed on the surface

$\mathcal{V}$

(nonlinear component of sound). In this study, the direct formulation of the acoustic analogy is adopted, due to its benefits in terms of accuracy, relative to the more typical permeable formulation (Di Francescantonio Reference Di Francescantonio1997), which is often preferred, since computationally less expensive. In the framework of the direct formulation, the surface and volume integrals on the right-hand side of (2.6) are computed on the surface of the bodies immersed within the flow and across a control volume encompassing all fluid regions of the computational domain populated by acoustic sources (vorticity, turbulence). This approach, although computationally more expensive than the permeable formulation, is able to provide more detailed information on the acoustic field, since it allows separating the different components of sound, as reported in the following analysis of the results in § 4. It is worth mentioning that the hydrophones (receivers) considered for the reconstruction of the acoustic field cannot be placed on the surface

![]() $\mathcal{S}$

or within the volume

$\mathcal{S}$

or within the volume

![]() $\mathcal{V}$

, since this selection would arise in a singularity, due to the distance between source and receiver,

$\mathcal{V}$

, since this selection would arise in a singularity, due to the distance between source and receiver,

![]() $r$

, going to zero.

$r$

, going to zero.

The first term on the right-hand side of (2.6) is called ‘thickness’ sound, since it depends on the volume of fluid displaced by the body within the flow. The quantities

![]() $\rho ^*$

and

$\rho ^*$

and

![]() $v_n$

are a reference density, assumed equal to the density of the fluid, and the velocity of the elemental surface

$v_n$

are a reference density, assumed equal to the density of the fluid, and the velocity of the elemental surface

![]() $dS$

along its normal direction. The scalar

$dS$

along its normal direction. The scalar

![]() $r$

is the magnitude of the vector

$r$

is the magnitude of the vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{r} = \boldsymbol{x} - \boldsymbol{y}$

, which represents the position of the receiver, relative to the acoustic source at position

$\boldsymbol{r} = \boldsymbol{x} - \boldsymbol{y}$

, which represents the position of the receiver, relative to the acoustic source at position

![]() $\boldsymbol{y}$

.

$\boldsymbol{y}$

.

![]() $M_r$

is the Mach number of the flow along the direction defined by the vector

$M_r$

is the Mach number of the flow along the direction defined by the vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{r}$

, which in the realm of incompressible flows is typically very close to zero. The second and third terms on the right-hand side of (2.6) represent the ‘loading’ sound, originating from the variation in time of the load conditions on the bodies immersed within the flow. The scalar

$\boldsymbol{r}$

, which in the realm of incompressible flows is typically very close to zero. The second and third terms on the right-hand side of (2.6) represent the ‘loading’ sound, originating from the variation in time of the load conditions on the bodies immersed within the flow. The scalar

![]() $c$

is the velocity of sound in the particular medium,

$c$

is the velocity of sound in the particular medium,

![]() $p'$

is the fluctuation in time of the hydrodynamic pressure on the elemental surface

$p'$

is the fluctuation in time of the hydrodynamic pressure on the elemental surface

![]() ${\rm d}S$

,

${\rm d}S$

,

![]() $\widehat {n}_i$

is the component in the direction

$\widehat {n}_i$

is the component in the direction

![]() $i$

of the unit vector normal to

$i$

of the unit vector normal to

![]() ${\rm d}S$

while

${\rm d}S$

while

![]() $\widehat {r}_i$

is the component in the direction

$\widehat {r}_i$

is the component in the direction

![]() $i$

of the unit vector associated with

$i$

of the unit vector associated with

![]() $\boldsymbol{r}$

. The volume integrals represent the ‘quadrupole’ sound, originating from vorticity and turbulence within the flow. The scalar

$\boldsymbol{r}$

. The volume integrals represent the ‘quadrupole’ sound, originating from vorticity and turbulence within the flow. The scalar

![]() $T_{\textit{rr}}$

in those integrals is given by the following expression:

$T_{\textit{rr}}$

in those integrals is given by the following expression:

where

![]() $T_{\textit{ij}}$

is the

$T_{\textit{ij}}$

is the

![]() $ij$

element of the Lighthill tensor,

$ij$

element of the Lighthill tensor,

where

![]() $p^*$

is a reference pressure, assumed equal to the free stream pressure,

$p^*$

is a reference pressure, assumed equal to the free stream pressure,

![]() $P$

, while

$P$

, while

![]() $\sigma _{\textit{ij}}$

is the

$\sigma _{\textit{ij}}$

is the

![]() $ij$

element of the viscous stress tensor. In (2.8), the second quantity on the right-hand side is the compressibility term, which is equal to zero in the present case of an incompressible flow. Note also that the viscosity term (the last quantity on the right-hand side) was assumed negligible. Therefore, the Lighthill tensor was computed as

$ij$

element of the viscous stress tensor. In (2.8), the second quantity on the right-hand side is the compressibility term, which is equal to zero in the present case of an incompressible flow. Note also that the viscosity term (the last quantity on the right-hand side) was assumed negligible. Therefore, the Lighthill tensor was computed as

![]() $ T_{\textit{ij}}=\rho u_i u_{\!j}$

. The scalar

$ T_{\textit{ij}}=\rho u_i u_{\!j}$

. The scalar

![]() $T_{kk}$

in the last two terms of (2.6) is the trace of the Lighthill tensor.

$T_{kk}$

in the last two terms of (2.6) is the trace of the Lighthill tensor.

It is worth mentioning that all integrals on the right-hand side of (2.6) should be computed at the emission time

![]() $\mathcal{T}$

, since the speed of propagation of the acoustic waves is finite. The emission time represents the time when the acoustic waves start from the source at position

$\mathcal{T}$

, since the speed of propagation of the acoustic waves is finite. The emission time represents the time when the acoustic waves start from the source at position

![]() $\boldsymbol{y}$

to reach the receiver at position

$\boldsymbol{y}$

to reach the receiver at position

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}$

at time

$\boldsymbol{x}$

at time

![]() $t$

. It is given by

$t$

. It is given by

where

![]() $r/c$

represents the time delay. Taking into account the time delay is very problematic in terms of acoustic postprocessing. Meanwhile, as reported in the literature (Cianferra et al. Reference Cianferra, Ianniello and Armenio2019a

,

Reference Cianferra, Petronio and Armeniob

), in the particular field of marine propulsion the time delay can be neglected, since the speed of sound in water is much larger than the typical velocities of marine propellers. For instance, in the case considered in the present study there is a difference of two orders of magnitude between

$r/c$

represents the time delay. Taking into account the time delay is very problematic in terms of acoustic postprocessing. Meanwhile, as reported in the literature (Cianferra et al. Reference Cianferra, Ianniello and Armenio2019a

,

Reference Cianferra, Petronio and Armeniob

), in the particular field of marine propulsion the time delay can be neglected, since the speed of sound in water is much larger than the typical velocities of marine propellers. For instance, in the case considered in the present study there is a difference of two orders of magnitude between

![]() $c$

and the tangential velocity of the propeller blades. Therefore, the time delay was neglected, assuming

$c$

and the tangential velocity of the propeller blades. Therefore, the time delay was neglected, assuming

![]() $\mathcal{T}=t$

. The approach discussed in this section was already successfully adopted in our earlier studies to reconstruct the sound radiated from marine propellers, including also comparisons with experiments (Posa et al. Reference Posa, Broglia and Felli2022b

,

Reference Posa, Broglia, Felli, Cianferra and Armenioc

,

Reference Posa, Felli and Brogliad

,

Reference Posa, Felli and Brogliae

).

$\mathcal{T}=t$

. The approach discussed in this section was already successfully adopted in our earlier studies to reconstruct the sound radiated from marine propellers, including also comparisons with experiments (Posa et al. Reference Posa, Broglia and Felli2022b

,

Reference Posa, Broglia, Felli, Cianferra and Armenioc

,

Reference Posa, Felli and Brogliad

,

Reference Posa, Felli and Brogliae

).

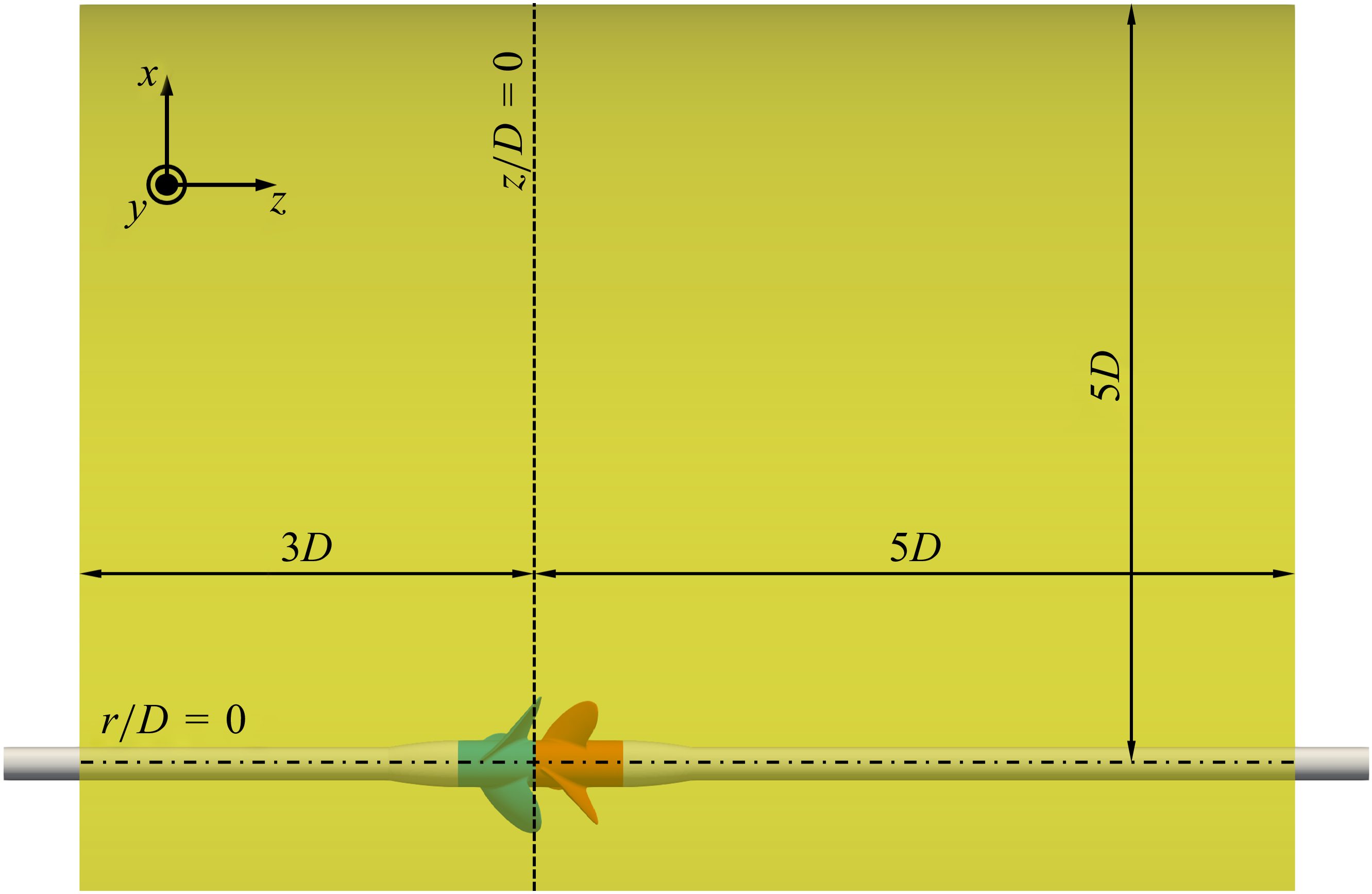

Figure 1. Visualization of the (a)

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

, (b)

${\textrm{CRP}}$

, (b)

![]() ${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and (c)

${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and (c)

![]() ${\textrm{REAR}}$

systems.

${\textrm{REAR}}$

systems.

3. Set-up

3.1. The LES computations

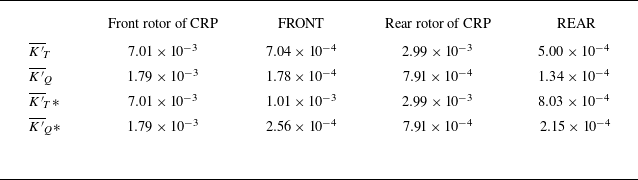

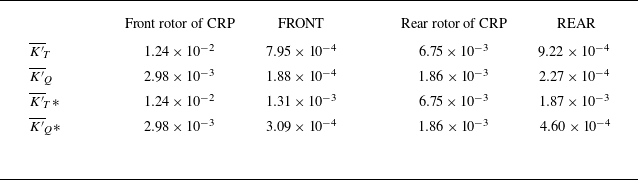

The LES computations were conducted on a contra-rotating propeller, whose geometry is illustrated in figure 1(a), consisting of front and rear three-bladed rotors moving at opposite angular speeds. Although this configuration, with the front and rear rotors sharing the same number of blades, may be not optimal in terms of acoustic performance, it reproduces the working conditions of actual contra-rotating propulsion systems. The set-up included both upstream and downstream stationary shafts and the propulsion system was working in open-water conditions, which means it was ingesting a uniform streamwise flow. The two rotors of the contra-rotating system were also simulated alone, increasing their rotational speed with the purpose of producing the same thrust as the overall contra-rotating system. In these cases, the missing rotor was replaced by a ‘dummy’ hub, moving at the opposite rotational speed of the other rotor, as shown in figure 1(b,c). This is the same set-up considered in the reference experiments (Capone & Alves Pereira Reference Capone and Alves Pereira2020; Alves Pereira et al. Reference Alves Pereira, Capone and Di Felice2021; Capone et al. Reference Capone, Di Felice and Alves Pereira2021). The systems of the contra-rotating, front and rear propellers will be denoted hereafter as

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

,

${\textrm{CRP}}$

,

![]() ${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

![]() ${\textrm{REAR}}$

, respectively. As shown in figure 1, the magnitudes of the rotational speeds of their rotors are indicated as

${\textrm{REAR}}$

, respectively. As shown in figure 1, the magnitudes of the rotational speeds of their rotors are indicated as

![]() $\varOmega _C$

,

$\varOmega _C$

,

![]() $\varOmega _F$

and

$\varOmega _F$

and

![]() $\varOmega _R$

.

$\varOmega _R$

.

The working conditions of marine propellers are typically characterized by means of the advance coefficient,

![]() $J$

, and the Reynolds number,

$J$

, and the Reynolds number,

![]() $\textit{Re}_p$

, defined, respectively, as

$\textit{Re}_p$

, defined, respectively, as

The advance coefficient represents the rotational speed of the propeller in non-dimensional form, where

![]() $V$

is the advance velocity, in this case (open-water conditions) equal to the free stream velocity

$V$

is the advance velocity, in this case (open-water conditions) equal to the free stream velocity

![]() $U$

,

$U$

,

![]() $n$

is the rotational frequency of the propeller while

$n$

is the rotational frequency of the propeller while

![]() $D$

is its diameter. It is worth mentioning that the two rotors of the

$D$

is its diameter. It is worth mentioning that the two rotors of the

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

system are not identical. The front one is larger. Its diameter was utilized as a reference to scale all quantities. The rear rotor has instead a diameter

${\textrm{CRP}}$

system are not identical. The front one is larger. Its diameter was utilized as a reference to scale all quantities. The rear rotor has instead a diameter

![]() $d=0.91\!D$

. For marine propellers the Reynolds number is typically referred to the radial location corresponding to

$d=0.91\!D$

. For marine propellers the Reynolds number is typically referred to the radial location corresponding to

![]() $70\,\%R$

, where

$70\,\%R$

, where

![]() $R$

is the radial extent of the (front) propeller. In (3.1),

$R$

is the radial extent of the (front) propeller. In (3.1),

![]() $c_{70\,\%R}$

is the chord of the propeller blades at

$c_{70\,\%R}$

is the chord of the propeller blades at

![]() $r=70\,\%R$

, while

$r=70\,\%R$

, while

![]() $\sqrt {(2 \pi n \; 0.7\!R)^2+V^2}$

is the magnitude of the relative velocity of the flow at the same radial location.

$\sqrt {(2 \pi n \; 0.7\!R)^2+V^2}$

is the magnitude of the relative velocity of the flow at the same radial location.

The

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

system was simulated for two values of the advance coefficient:

${\textrm{CRP}}$

system was simulated for two values of the advance coefficient:

![]() $J=1.3$

and

$J=1.3$

and

![]() $J=0.7$

. In the experiments by Capone et al. (Reference Capone, Di Felice and Alves Pereira2021) and Alves Pereira et al. (Reference Alves Pereira, Capone and Di Felice2021) different values of the advance coefficient were reproduced by changing the free stream velocity, while maintaining identical but opposite rotational speeds for the front and rear rotors (24 Hz). The two simulated advance coefficients are equivalent to the working condition of design and a highly loaded condition, respectively. The

$J=0.7$

. In the experiments by Capone et al. (Reference Capone, Di Felice and Alves Pereira2021) and Alves Pereira et al. (Reference Alves Pereira, Capone and Di Felice2021) different values of the advance coefficient were reproduced by changing the free stream velocity, while maintaining identical but opposite rotational speeds for the front and rear rotors (24 Hz). The two simulated advance coefficients are equivalent to the working condition of design and a highly loaded condition, respectively. The

![]() ${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

![]() ${\textrm{REAR}}$

systems were also simulated, but at higher values of the rotational speed, with the purpose of producing the same overall thrust as the

${\textrm{REAR}}$

systems were also simulated, but at higher values of the rotational speed, with the purpose of producing the same overall thrust as the

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

system. The values of advance coefficient corresponding to

${\textrm{CRP}}$

system. The values of advance coefficient corresponding to

![]() $J=1.3$

of

$J=1.3$

of

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

were equal to

${\textrm{CRP}}$

were equal to

![]() $J=1.085$

and

$J=1.085$

and

![]() $J=1.026$

for

$J=1.026$

for

![]() ${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

![]() ${\textrm{REAR}}$

, respectively. For the highly loaded condition the advance coefficients of

${\textrm{REAR}}$

, respectively. For the highly loaded condition the advance coefficients of

![]() ${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

![]() ${\textrm{REAR}}$

were reduced to

${\textrm{REAR}}$

were reduced to

![]() $J=0.546$

and

$J=0.546$

and

![]() $J=0.491$

. In order to produce the same thrust, the

$J=0.491$

. In order to produce the same thrust, the

![]() ${\textrm{REAR}}$

system is required to achieve lower advance coefficients than the

${\textrm{REAR}}$

system is required to achieve lower advance coefficients than the

![]() ${\textrm{FRONT}}$

system, equivalent to higher rotational speeds, since the rear rotor is smaller. All cases were simulated for values of the model-scale Reynolds number

${\textrm{FRONT}}$

system, equivalent to higher rotational speeds, since the rear rotor is smaller. All cases were simulated for values of the model-scale Reynolds number

![]() $\textit{Re}_p \approx 2.5 \times 10^5$

. It is important to mention that the

$\textit{Re}_p \approx 2.5 \times 10^5$

. It is important to mention that the

![]() ${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

![]() ${\textrm{REAR}}$

systems operate further away from their optimal working condition, if they are required to produce the same overall thrust of the

${\textrm{REAR}}$

systems operate further away from their optimal working condition, if they are required to produce the same overall thrust of the

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

system. An alternative strategy would be a modified design of the front and rear rotors, having the same operative range as the

${\textrm{CRP}}$

system. An alternative strategy would be a modified design of the front and rear rotors, having the same operative range as the

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

system and achieving their best performance at the same advance coefficient. Meanwhile, the modification of the geometries of the two rotors would make the comparison between their wake systems less straightforward, but it is worth of consideration for future studies. It should be also noted that this solution may be practically unfeasible, depending on the design requirements, since it would likely require an increase of the size of the isolated rotors, in comparison with the

${\textrm{CRP}}$

system and achieving their best performance at the same advance coefficient. Meanwhile, the modification of the geometries of the two rotors would make the comparison between their wake systems less straightforward, but it is worth of consideration for future studies. It should be also noted that this solution may be practically unfeasible, depending on the design requirements, since it would likely require an increase of the size of the isolated rotors, in comparison with the

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

system. In other words, an additional advantage of contra-rotating systems consists in their ability to produce efficiently larger levels of thrust for a given rotor diameter.

${\textrm{CRP}}$

system. In other words, an additional advantage of contra-rotating systems consists in their ability to produce efficiently larger levels of thrust for a given rotor diameter.

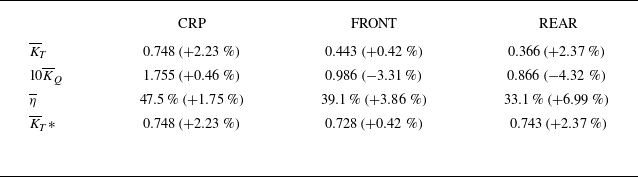

Figure 2. Dimensions of the cylindrical computational domain. The dashed and dot–dashed lines representing the origins of the streamwise and radial coordinates.

All computations were carried out within a cylindrical domain (figure 2), having a radius equivalent to

![]() $5.0D$

and extending

$5.0D$

and extending

![]() $3.0D$

upstream and

$3.0D$

upstream and

![]() $5.0D$

downstream of the plane between the hubs of the front and rear rotors, where the origin of the streamwise coordinates was placed. To mimic open-water conditions, a uniform streamwise velocity was enforced at the inlet section of the computational domain. At the outlet section, convective boundary conditions were utilized for the three velocity components to transport the eddies populating the wake away from the computational domain. At the lateral boundary, free stream conditions were reproduced by enforcing homogeneous Neumann conditions with impermeability, which means that the radial gradients of both azimuthal and streamwise velocities as well as the radial velocity were set to zero. Homogeneous Neumann conditions were also utilized for both pressure and eddy-viscosity at all external boundaries of the computational domain. At the azimuthal boundaries periodic conditions were enforced on all variables (the three velocity components, pressure and eddy-viscosity). The no-slip condition on the surface of the bodies immersed within the flow was imposed by using the IB technique discussed above in § 2.

$5.0D$

downstream of the plane between the hubs of the front and rear rotors, where the origin of the streamwise coordinates was placed. To mimic open-water conditions, a uniform streamwise velocity was enforced at the inlet section of the computational domain. At the outlet section, convective boundary conditions were utilized for the three velocity components to transport the eddies populating the wake away from the computational domain. At the lateral boundary, free stream conditions were reproduced by enforcing homogeneous Neumann conditions with impermeability, which means that the radial gradients of both azimuthal and streamwise velocities as well as the radial velocity were set to zero. Homogeneous Neumann conditions were also utilized for both pressure and eddy-viscosity at all external boundaries of the computational domain. At the azimuthal boundaries periodic conditions were enforced on all variables (the three velocity components, pressure and eddy-viscosity). The no-slip condition on the surface of the bodies immersed within the flow was imposed by using the IB technique discussed above in § 2.

The computational domain was discretized by using a cylindrical grid consisting of

![]() $722 \times 3586 \times 1794$

(

$722 \times 3586 \times 1794$

(

![]() $4.6\times10^9$

) points in the radial, azimuthal and axial directions, respectively, corresponding to a near-wall resolution equivalent to approximately

$4.6\times10^9$

) points in the radial, azimuthal and axial directions, respectively, corresponding to a near-wall resolution equivalent to approximately

![]() $y^+=5$

, where

$y^+=5$

, where

![]() $y^+$

is the normal distance from the bodies in wall-units. The radial and axial grids were uniform in the region of the propeller blades, while stretching was utilized away from them to save grid points. However, while grid coarsening was fast in the radial and upstream directions, it was smoother in the downstream direction, up to

$y^+$

is the normal distance from the bodies in wall-units. The radial and axial grids were uniform in the region of the propeller blades, while stretching was utilized away from them to save grid points. However, while grid coarsening was fast in the radial and upstream directions, it was smoother in the downstream direction, up to

![]() $3.5D$

, with the purpose of resolving accurately the wake structures. Slices of the computational mesh are reported in figure 3, where only a small sample of points is represented, for visibility of the grid lines. The angular spacing of the azimuthal grid was instead uniform. This was convenient to cluster points in the regions of the propellers and their wake, while reducing the resolution away from them: thanks to the cylindrical topology of the grid, the uniform angular spacing results in finer linear spacings towards inner radial coordinates (where the propellers and their wake systems are placed) and coarser linear spacings towards outer radial coordinates at the lateral boundary of the computational domain.

$3.5D$

, with the purpose of resolving accurately the wake structures. Slices of the computational mesh are reported in figure 3, where only a small sample of points is represented, for visibility of the grid lines. The angular spacing of the azimuthal grid was instead uniform. This was convenient to cluster points in the regions of the propellers and their wake, while reducing the resolution away from them: thanks to the cylindrical topology of the grid, the uniform angular spacing results in finer linear spacings towards inner radial coordinates (where the propellers and their wake systems are placed) and coarser linear spacings towards outer radial coordinates at the lateral boundary of the computational domain.

Figure 3. Meridian slices of the cylindrical grid: (a) global and (b) detailed views. For visibility of the grid lines, only one of every 256 and 64 points shown in (a) and (b), respectively.

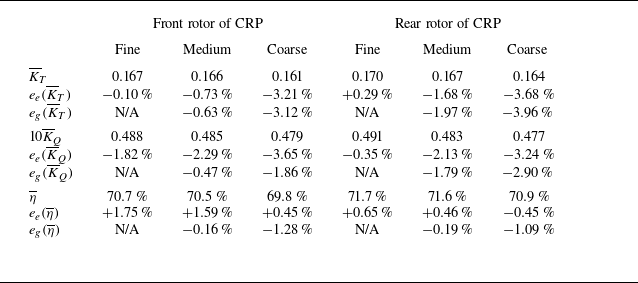

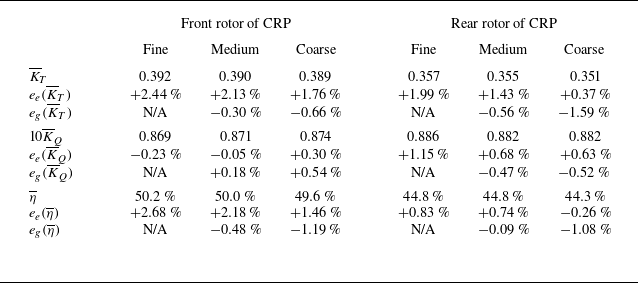

The grid discussed above was utilized to simulate all

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

,

${\textrm{CRP}}$

,

![]() ${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

![]() ${\textrm{REAR}}$

systems, which was beneficial to the accuracy of the comparison across them. This grid will be denoted hereafter as ‘fine’ grid and all following results will be reported from computations on this grid, unless otherwise stated. However, additional computations were carried out for

${\textrm{REAR}}$

systems, which was beneficial to the accuracy of the comparison across them. This grid will be denoted hereafter as ‘fine’ grid and all following results will be reported from computations on this grid, unless otherwise stated. However, additional computations were carried out for

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

on two coarser grids, indicated, respectively, as ‘medium’ and ‘coarse’ grids, to demonstrate grid independence of the results. The

${\textrm{CRP}}$

on two coarser grids, indicated, respectively, as ‘medium’ and ‘coarse’ grids, to demonstrate grid independence of the results. The

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

system was selected for this grid independence study since its flow physics is the most challenging one to capture. The medium and coarse grids were generated from the fine grid by increasing the size of each grid cell of factors equal to

${\textrm{CRP}}$

system was selected for this grid independence study since its flow physics is the most challenging one to capture. The medium and coarse grids were generated from the fine grid by increasing the size of each grid cell of factors equal to

![]() $\sqrt [3]{2}$

and

$\sqrt [3]{2}$

and

![]() $\sqrt [3]{4}$

across the radial, azimuthal and axial directions. By using this strategy the overall number of grid points was reduced of factors equal to two and four, relative to the fine grid, but keeping the same criteria of grid stretching in the radial and axial directions, while the angular spacing of the azimuthal grid was still uniform. Eventually, the medium and coarse grids were composed of

$\sqrt [3]{4}$

across the radial, azimuthal and axial directions. By using this strategy the overall number of grid points was reduced of factors equal to two and four, relative to the fine grid, but keeping the same criteria of grid stretching in the radial and axial directions, while the angular spacing of the azimuthal grid was still uniform. Eventually, the medium and coarse grids were composed of

![]() $572 \times 2818 \times 1410$

(

$572 \times 2818 \times 1410$

(

![]() $2.3\times10^9$

) and

$2.3\times10^9$

) and

![]() $454 \times 2370 \times 1186$

(

$454 \times 2370 \times 1186$

(

![]() $1.3\times10^9$

) points.

$1.3\times10^9$

) points.

Thanks to the adopted IB methodology, the discretization of the geometry of the bodies immersed within the flow was separated from the discretization of the computational domain. The former utilized Lagrangian grids, consisting of triangular elements and representing the surface of the propellers. These grids were free to move across the cells of the Eulerian grids discussed above. The Lagrangian grids utilized to represent the upstream shaft, the front rotor, the rear rotor and the downstream shaft of the

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

system were composed of

${\textrm{CRP}}$

system were composed of

![]() $32 \times 10^3$

,

$32 \times 10^3$

,

![]() $66 \times 10^3$

,

$66 \times 10^3$

,

![]() $69 \times 10^3$

and

$69 \times 10^3$

and

![]() $51 \times 10^3$

triangles, respectively, while the dummy hubs replacing the rear and front rotors in the

$51 \times 10^3$

triangles, respectively, while the dummy hubs replacing the rear and front rotors in the

![]() ${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

![]() ${\textrm{REAR}}$

systems were discretized by using approximately

${\textrm{REAR}}$

systems were discretized by using approximately

![]() $10 \times 10^3$

triangular elements. These grids are represented in figure 4.

$10 \times 10^3$

triangular elements. These grids are represented in figure 4.

Figure 4. Lagrangian grids representing the immersed boundaries: (a)

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

(upstream view), (b)

${\textrm{CRP}}$

(upstream view), (b)

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

(downstream view), (c)

${\textrm{CRP}}$

(downstream view), (c)

![]() ${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and (d)

${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and (d)

![]() ${\textrm{REAR}}$

.

${\textrm{REAR}}$

.

Due to stability requirements, the very fine resolution of the Eulerian grid adopted to discretize the computational domain resulted in very fine resolutions in time. For the computations on the fine grid at the design working condition the number of time steps per revolution ranged between

![]() $7.4 \times 10^3$

and

$7.4 \times 10^3$

and

![]() $9.0 \times 10^3$

across the

$9.0 \times 10^3$

across the

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

,

${\textrm{CRP}}$

,

![]() ${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

![]() ${\textrm{REAR}}$

cases, while it was between

${\textrm{REAR}}$

cases, while it was between

![]() $5.5 \times 10^3$

and

$5.5 \times 10^3$

and

![]() $6.9 \times 10^3$

for the highly loaded condition, where the smaller time step at off-design conditions was balanced by the higher rotational speed of the propellers. For the computations dealing with the

$6.9 \times 10^3$

for the highly loaded condition, where the smaller time step at off-design conditions was balanced by the higher rotational speed of the propellers. For the computations dealing with the

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

system on the medium and coarse grids the number of steps per revolution was equal to approximately

${\textrm{CRP}}$

system on the medium and coarse grids the number of steps per revolution was equal to approximately

![]() $9.0 \times 10^3$

at design conditions and

$9.0 \times 10^3$

at design conditions and

![]() $5.2 \times 10^3$

at the off-design conditions. Note that they were not reduced proportionally to the resolution in space, since stability required to keep small values of time step.

$5.2 \times 10^3$

at the off-design conditions. Note that they were not reduced proportionally to the resolution in space, since stability required to keep small values of time step.

All computations were advanced in time for two flow-through times, in order to develop statistically steady conditions in the wake. Then, statistics were computed at run time across 20 additional revolutions of the propellers. They were computed both as time-averages and phase-averages. The former included in the statistical sample all instantaneous realizations of the solution, while the latter only the flow fields corresponding to specific relative positions of the front and rear propellers of the contra-rotating system. For the

![]() ${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

![]() ${\textrm{REAR}}$

systems phase-averages were computed within a reference frame rotating with the front and rear rotors, respectively. Phase-averages are useful to capture the coherence of the wake flow, which will be shown to be characterized by a very complex topology downstream of

${\textrm{REAR}}$

systems phase-averages were computed within a reference frame rotating with the front and rear rotors, respectively. Phase-averages are useful to capture the coherence of the wake flow, which will be shown to be characterized by a very complex topology downstream of

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

. Time-averaged and phase-averaged statistics will be indicated below as

${\textrm{CRP}}$

. Time-averaged and phase-averaged statistics will be indicated below as

![]() $\overline {\mathcal{F}}$

and

$\overline {\mathcal{F}}$

and

![]() $\widehat {\mathcal{F}}$

, respectively, where

$\widehat {\mathcal{F}}$

, respectively, where

![]() $\mathcal{F}$

denotes any physical quantity.

$\mathcal{F}$

denotes any physical quantity.

All simulations were carried out in a high-performance computing environment, using an in-house-developed Fortran solver with parallel capabilities. The computational domain was separated in cylindrical subdomains by decomposition along the streamwise direction, while the communications across subdomains utilized calls to message passage interface libraries. The simulations on the fine, medium and coarse grids were conducted on

![]() $1792$

,

$1792$

,

![]() $1408$

and

$1408$

and

![]() $1184$

cores of MeluXina CPU at LuxProvide. The overall computational cost was equivalent to

$1184$

cores of MeluXina CPU at LuxProvide. The overall computational cost was equivalent to

![]() $25 \times 10^6$

core hours. In particular, the most expensive computations, which were those of the

$25 \times 10^6$

core hours. In particular, the most expensive computations, which were those of the

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

system on the fine grid, required

${\textrm{CRP}}$

system on the fine grid, required

![]() $6 \times 10^6$

core hours each.

$6 \times 10^6$

core hours each.

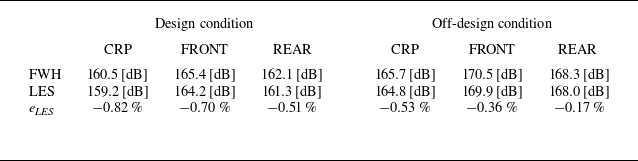

Figure 5. Control volume considered for the computation of the quadrupole component of sound shown in green. The yellow area represents the domain of the LES computations.

3.2. The FWH postprocessing

The sound radiated by the

![]() ${\textrm{CRP}}$

,

${\textrm{CRP}}$

,

![]() ${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

${\textrm{FRONT}}$

and

![]() ${\textrm{REAR}}$

systems was reconstructed in post-processing from instantaneous realizations of the LES solution, using the FWH acoustic analogy discussed in § 2. For the thickness component of sound (the first term on the right-hand side of (2.6)), which was actually verified to be negligible, only the information on the kinematics of the propellers is required. Instead, for the loading component (the second and third terms on the right-hand side of (2.6)) the fluctuations in time of the hydrodynamic pressure over the surface of the propellers need to be reconstructed. They were extrapolated on the surface of the Lagrangian grids representing the immersed boundaries from the solution on the Eulerian grid. For the quadrupole component of sound (the remaining terms on the right-hand side of (2.6)) the information on velocity and pressure across the fluid region of the computational domain is required to compute all corresponding volume integrals. Therefore, an appropriate control volume was selected, encompassing all important acoustic sources, corresponding to the flow structures in the vicinity of the propellers and in their wake. This control volume was cylindrical, with a radial extent equivalent to

${\textrm{REAR}}$

systems was reconstructed in post-processing from instantaneous realizations of the LES solution, using the FWH acoustic analogy discussed in § 2. For the thickness component of sound (the first term on the right-hand side of (2.6)), which was actually verified to be negligible, only the information on the kinematics of the propellers is required. Instead, for the loading component (the second and third terms on the right-hand side of (2.6)) the fluctuations in time of the hydrodynamic pressure over the surface of the propellers need to be reconstructed. They were extrapolated on the surface of the Lagrangian grids representing the immersed boundaries from the solution on the Eulerian grid. For the quadrupole component of sound (the remaining terms on the right-hand side of (2.6)) the information on velocity and pressure across the fluid region of the computational domain is required to compute all corresponding volume integrals. Therefore, an appropriate control volume was selected, encompassing all important acoustic sources, corresponding to the flow structures in the vicinity of the propellers and in their wake. This control volume was cylindrical, with a radial extent equivalent to

![]() $0.9D$

and spanning in the streamwise direction from

$0.9D$

and spanning in the streamwise direction from

![]() $2.5D$

upstream to

$2.5D$

upstream to

![]() $4.5D$

downstream, relative to the origin of the streamwise coordinates (figure 5). This selection of the control volume is based on the assumption that the most intense wake structures, which are important acoustic sources, are enclosed. The following discussion will demonstrate indeed that the decay of vorticity and turbulence within the wake flow downstream of the propellers is fast enough to make this hypothesis legitimate. In other words, it is assumed that the wake flow downstream of

$4.5D$

downstream, relative to the origin of the streamwise coordinates (figure 5). This selection of the control volume is based on the assumption that the most intense wake structures, which are important acoustic sources, are enclosed. The following discussion will demonstrate indeed that the decay of vorticity and turbulence within the wake flow downstream of the propellers is fast enough to make this hypothesis legitimate. In other words, it is assumed that the wake flow downstream of

![]() $4.5D$

is diffused enough to provide a limited, negligible contribution to the acoustic field.

$4.5D$

is diffused enough to provide a limited, negligible contribution to the acoustic field.

Hydrophones were placed on the meridian planes of equations

![]() $x/D=0.0$

and

$x/D=0.0$

and

![]() $y/D=0.0$

(whose results were averaged to increase the size of the statistical sample) and the cross-stream plane of equation

$y/D=0.0$