Severe mental illness

Definition and classification

Severe mental illness (SMI) encompasses a range of mental, behavioural, or emotional disorders that causes significant functional impairment, substantially limiting or interfering with one or more major life activities(1). Generally, SMI refers to a diagnosis of psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, major depression, anxiety disorder and/or eating and personality disorders, provided the degree of functional impairment is severe(Reference Gaynes, Brown and Lux2). While the precise cause of mental illness remains unclear, research indicates that a combination of genetic, environmental, and social factors contribute to their development(3). There remains a lack of clarity on how SMI is defined across contexts, including clinical settings, scientific research and legal standards(Reference Gonzales, Kois and Chen4). Furthermore, there is ongoing discussion that labelling an already stigmatised diagnosis as ‘severe’ could worsen the attitudinal consequences of diagnostic labelling, including stigma, potentially creating further barriers to recovery(Reference Gonzales, Kois and Chen4).

Prevalence and burden

Studies examining the global burden of disease have emphasised the vast scale of mental illness worldwide(Reference Lopez and Murray5), with SMI affecting individuals in all groups of society(Reference Doran and Kinchin6). Approximately one in three people will face a mental health disruption during their lifetime(Reference Vigo, Thornicroft and Atun7), and an estimated 10% of the global population currently live with a mental disorder(8). Ireland reports one of the highest levels of mental ill health in the European Union (EU), with over one million affected in 2019, representing 21% of the population, up from 18.5% in 2016, and exceeding the EU average of 16.7%(9,10) . These figures are based on the most recent Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development country health profile (2023). The Healthy Ireland Survey (2024) further reported that approximately 12% of the Irish population exhibit mental health problems, with the lowest mental health scores recorded among those aged 15–24 years(11). Additionally, a study conducted in 2022 by Maynooth University, Trinity College Dublin and the National College of Ireland, found that over 40% of Irish adults have a mental health disorder and more than one in ten people have attempted suicide at some point in their lives(Reference Hyland, Vallières and Shevlin12). Although based on different assessment methods, these findings collectively underscore the ongoing and significant mental health challenges in Ireland, highlighting the need for support and intervention.

Health inequalities

Individuals living with SMI experience a significantly reduced life expectancy across a broad spectrum of diagnoses(Reference Chan, Correll and Wong13). The presence of multiple physical and psychiatric conditions is a major factor contributing to significantly poorer health outcomes in this population(Reference Halstead, Cao and Mohr14). The risk of comorbidity is pervasive across a wide range of co-occurring disorders, with the likelihood of developing a subsequent mental health disorder highest within the first year of a primary diagnosis, and elevated risks persisting for over 15 years thereafter(Reference Plana-Ripoll, Pedersen and Holtz15). In addition, individuals with SMI have more than twice the likelihood of experiencing physical multimorbidity (the presence of two or more concurrent chronic conditions) compared to those without SMI(Reference Halstead, Cao and Mohr14).

Addressing these stark health disparities requires urgent implementation of comprehensive and multi-level intervention strategies(Reference Chan, Correll and Wong13). Central to such efforts is understanding and targeting key modifiable risk factors to reduce the alarming rates of mortality in this population(Reference Thornicroft16), with nutrition emerging as a critical modifiable factor(Reference Cherak, Fiest and VanderSluis17). The evidence underscores the importance of population-level, government-led strategies that prioritises nutrition as a fundamental determinant of health outcomes(Reference Teasdale, Ward and Samaras18). Therefore, this review discusses the current and potential role of digital nutrition interventions for individuals with severe mental illness, examining insights, challenges and future directions to inform research and practice.

Nutrition and severe mental illness

Nutritional psychiatry

Nutritional psychiatry is a field of research that explores the effects of nutrition interventions on mental health outcomes(Reference Jacka19). It emphasises how food choices influence mental health and provides evidence for diet as a modifiable risk factor for SMI(Reference Marx, Moseley and Berk20). In recent years, a growing body of research has identified a strong association between diet and SMI(Reference Conner, Brookie and Carr21–Reference Emerson and Carbert23). Their link could be explained by the impact of diet on many pathophysiological pathways, which outline why and how, diet can affect mental and cognitive health(Reference Marx, Moseley and Berk20). Examples of these pathways involve inflammation, epigenetics, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and the gut microbiota. For detailed synthesis of these pathways see Marx et al.(Reference Marx, Moseley and Berk20). The International Society of Nutritional Psychiatry Research consensus position statement titled ‘Nutritional Medicine in Modern Psychiatry’ (Reference Sarris, Logan and Akbaraly24) concluded that nutrition and nutraceuticals (dietary supplements used to promote bodily function, prevent disease and improve health)(Reference Sachdeva, Roy and Bharadvaja25) should now be mainstream elements of psychiatric practice. This consensus advocates for an integrative psychiatric model, in which nutrition plays a central role.

Diet quality

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), a healthy diet includes limiting saturated fat to less than 10% of total energy intake, reducing free sugars to 10% (ideally 5%), and keeping salt consumption below 5g per day(26). However, individuals with psychosis are less likely to meet the WHO Food Consumption Recommendations (>5 portions fruit/vegetables, 30g fibre, <5g of salt per day, <10% of daily energy from saturated fat)(Reference Martland, Teasdale and Murray27). Poor diet quality is a prevalent concern among individuals with SMI, with evidence reporting that this population consume significantly more dietary energy and sodium, both of which are linked to overall poor diet quality and unhealthier eating patterns(Reference Teasdale, Ward and Samaras18). Observational evidence further highlights that individuals with psychotic disorders also tend to have dietary patterns characterised by low consumption of fruit and vegetables, high intakes of refined carbohydrates and total fat, reduced intakes of fibre, omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids, as well as key vitamins and minerals(Reference Aucoin, LaChance and Cooley28).

While interpretations of a ‘healthy diet’ varies across countries and cultures, the Mediterranean diet (MedDiet) is widely regarded to have positive health outcomes, including lower incidences of chronic disease and greater longevity(Reference Sanchez and Garcia29,Reference Guasch-Ferré and Willett30) . It is typically characterised as high intake of plant-based foods, with an emphasis on minimally processed, locally grown ingredients, olive oil (served as the primary source of fat), with moderate amounts of dairy and red meat intake(Reference Guasch-Ferré and Willett30). In contrast, western dietary patterns have been linked to a range of chronic diseases(Reference García-Montero, Fraile-Martínez and Gómez-Lahoz31). They are characterised by high intakes of refined sugars, animal fats, processed meats, conventionally-farmed animal products, refined grains, high-fat dairy products, pre-packaged foods with minimal intake of unprocessed fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fish, nuts and seeds(Reference Cordain, Eaton and Sebastian32,Reference Malesza, Malesza and Walkowiak33) . Notably, a poorer diet, such as adherence to western dietary patterns, has been linked to chronicity of psychosis(Reference Teasdale, Ward and Samaras18,Reference Dipasquale, Pariante and Dazzan34–Reference Scoriels, Zimbron and Garcia-León36) .

While the Mediterranean diet is among the most extensively studied and supported, emerging evidence suggests that other dietary approaches such as the ketogenic diet(Reference Rog, Wingralek and Nowak37) may also offer benefits for individuals with SMI. However, research in this area is largely preliminary.

Contributing factors

A range of factors may contribute to suboptimal dietary behaviours in individuals with SMI. These include the effects of psychotropic medications, such as increased appetite, and weight gain(Reference Leucht, Cipriani and Spineli38–Reference Fitzgerald, Crowley and Dhubhlaing41), as well as psychological challenges such as low motivation and cognitive impairment, which can make planning and preparing meals difficult(Reference Teasdale, Ward and Samaras18). Food security defined at the societal levels refers to a situation where all people have reliable access to sufficient, safe and nutritious foods(Reference Compton42). Conversely, food insecurity is a common and significant issue affecting the SMI population(Reference Compton42–Reference Teasdale, Müller-Stierlin and Ruusunen44). Challenges with body weight management, along with environmental factors such as limited autonomy over food choices in controlled environments, further complicate dietary behaviours(Reference Lowndes, Angus and Peter45,Reference Mueller-Stierlin, Cornet and Peisser46) . While some studies indicate that individuals with SMI may have lower levels of nutrition knowledge and reduced cooking and food skills(Reference Barre, Ferron and Davis47–Reference Teasdale, Burrows and Hayes50), more recent research found comparable levels to healthy adults(Reference Mötteli, Provaznikova and Vetter51). Nevertheless, this research highlights the urgent need for nutritional support for this population, incorporating educational, behavioural and long-term approaches(Reference Mötteli, Provaznikova and Vetter51).

Nutrition interventions

Traditional nutrition interventions

Nutrition interventions can play a crucial role in the treatment of SMI(Reference Burrows, Teasdale and Rocks52) and should be recognised as a standard component of care for this population(Reference Teasdale, Ward and Samaras18). Nutrition interventions for mental health conditions have been categorised into three main types(Reference Cherak, Fiest and VanderSluis17), namely: (1) Guide (e.g., counselling), (2) Provide (e.g., food provisions) and (3) Add (e.g., supplementation).

These interventions can be delivered as single components or in complex combinations (e.g., guide alongside provide). Several systematic reviews have investigated the use of traditional nutrition interventions in SMI(Reference Cherak, Fiest and VanderSluis17,Reference Burrows, Teasdale and Rocks52–Reference Rocks, Teasdale and Fehily54) . A systematic review of randomised controlled trials found that dietary intervention led to improvements in weight, body mass index, waist circumference and blood glucose levels(Reference Teasdale, Ward and Rosenbaum53). Another review reported a large body of evidence supporting the positive impact of dietary interventions in individuals with SMI, leading to improvements in both weight-related and mental health outcomes(Reference Burrows, Teasdale and Rocks52). Nutrition education and behaviour change techniques are identified as effective components of these interventions(Reference Burrows, Teasdale and Rocks52). Given the higher prevalence of obesity among individuals with SMI(Reference Afzal, Siddiqi and Ahmad55), literature has documented the ‘double stigma’ faced by those living with both an SMI and obesity(Reference Mizock56). Although many interventions demonstrate some effectiveness, they primarily focus on weight loss or weight management, which is complex in this population group and may improve or decline participants’ mental health, dependent on individual diagnosis, nature of intervention and setting(Reference Burrows, Teasdale and Rocks52).

A more holistic approach is illustrated by the HELFIMED study(Reference Bogomolova, Zarnowiecki and Wilson57), which aimed to improve healthy eating behaviours in individuals with SMI through principles of the Mediterranean diet. The intervention integrated nutrition education with practical, behaviour-focused components such as cooking workshops and guided shopping trips. This multifaceted approach not only improved food behaviours (e.g., healthy eating habits, nutritional knowledge) but also enhanced independent living skills (e.g., increased cooking and shopping skills), biomarkers of dietary intake and cardiovascular disease risk factors after 12 weeks(Reference Bogomolova, Zarnowiecki and Wilson57). This study offers a particularly illustrative example of the value of incorporating behavioural skill development into nutrition intervention for this population.

While some reviews have found limited evidence for improvements in metabolic syndrome risk factors, they suggest that effectiveness may increase when interventions are delivered individually or by dietitians(Reference Rocks, Teasdale and Fehily54). However, such interventions are often labour and time intensive and the implementation of dietary interventions for individuals with SMI are often met with considerable challenges(Reference Teasdale, Samaras and Wade58,Reference Deenik, Tenback and Tak59) .

Challenges in implementing nutrition interventions

Dietitians and other professionals working with individuals with SMI must navigate low attendance rates, reduced cognitive capacity affecting information processing and retention, side effects of medication, decreased motivation, sedentary behaviour, isolation, social exclusion and financial constraints(Reference Teasdale, Samaras and Wade58). Additionally, healthcare professionals report organisational barriers including financial resources, insufficient staff capacity, lack of materials and time, inadequate education and lack of management support, which collectively hinder their ability to invest the necessary time and effort to overcome these challenges(Reference Deenik, Tenback and Tak59). Nevertheless, the primary challenge continues to be practical implementation and long-term maintenance of these interventions(Reference Deenik, Tenback and Tak59). Developing innovative strategies that aim to overcome these challenges and encourage healthy lifestyles, including healthy nutrition behaviours among individuals with SMI, is therefore essential. Digital technology, in particular, has been found to play an increasingly important role in supporting and enhancing health outcomes(Reference Firth, Siddiqi and Koyanagi60).

The potential of digital technology for supporting nutrition in severe mental illness

Digital technology

Digital technology has rapidly become embedded in and transformed many aspects of daily life(Reference Batra, Barker and Wang61). In the context of mental health care, digital interventions offer a promising alternative support model, with the potential to address many of the challenges faced by those living with a SMI(Reference Gan, McGillivray and Han62). The anonymity, accessibility and flexibility offered by digital mental health interventions helps overcome common structural and attitudinal barriers such as cost, time constraints and stigma(Reference Gan, McGillivray and Han62,Reference Hom, Stanley and Joiner63) . These technologies hold potential as behaviour change tools by supporting individuals with SMI in managing their health behaviours, while improving engagement and addressing socioeconomic and logical barriers associated with in-person components(Reference Sawyer, McKeon and Hassan64).

A wide range of digital tools are currently used in mental health care, including but not limited to mobile applications, digital medicine, digital personal health records, electronic pill containers(Reference Batra, Barker and Wang61), accelerometers, exergames, wearables, heart rate monitors(Reference Forde, Coppinger and Rea65), social media, virtual reality, chatbots and more advanced approaches such as digital phenotyping(Reference Torous, Bucci and Bell66). Furthermore, evidence from a sample of 249 individuals attending mental health clinics in the United States suggests that device ownership among individuals with SMI is comparable to the general population, with the majority owning a phone and most having a smartphone(Reference Young, Cohen and Niv67).

The growing momentum of digital transformation in health care is reflected in Ireland’s ‘Digital for Care – A Digital Health Framework 2024–2030’, which outlines a national vision for leveraging data, technology and innovation to deliver more affordable, equitable, person-centred and efficient care(68). This framework also highlights the important role of digital tools in improving population health outcomes(68). Overall, digital technologies have the potential to enhance mental health services, support personalised care and offer innovative digital interventions for prevention, and treatment support(Reference Bond, Mulvenna and Potts69). However, to fully realise this potential, it is essential to understand and address the barriers that may limit the effective use of these tools in individuals with SMI, including digital literacy, accessibility and relevance within the Irish mental health care context.

Barriers to technology use

A recent consensus on digital mental health for schizophrenia and other SMIs further emphasised the key barriers to digital intervention success, including sustained user engagement, and implementation challenges(Reference Smith, Hardy and Vinnikova70). The perception that individuals with SMI are either unwilling or incapable to engage with technology, alongside digital exclusion driven by socioeconomic inequalities, has contributed to the limited progress in this area(Reference Kozelka, Acquilano and Al-Abdulmunem71,Reference Spanakis, Lorimer and Newbronner72) . Individuals with SMI are indeed at a greater risk of digital exclusion, due to a combination of limited access to devices and low levels of digital literacy(Reference Spanakis, Lorimer and Newbronner72,Reference Middle and Welch73) . Even when a device is available, barriers such as financial resources can hinder consistent access, while a lack of confidence and digital skills can further limit effective use(Reference Kozelka, Acquilano and Al-Abdulmunem71–Reference Middle and Welch73). This reflects a persistent digital divide within this population, where the primary challenge may not only be access to technology but also the knowledge, skills and confidence to use these tools(Reference Camacho and Torous74).

Despite commonly held concerns that smartphone use may hinder the effectiveness of digital interventions in this population(Reference Sawyer, McKeon and Hassan64), a systematic review reported that individuals with SMI generally found digital interventions easy to use(Reference Sawyer, McKeon and Hassan64). In some studies, participants engaged beyond expectations by voluntarily completing additional modules or sessions(Reference Aschbrenner, Naslund and Shevenell75–Reference Brunette, Ferron and Robinson78). However, some individuals, particularly those with limited prior experience, faced challenges with internet access, accessibility and required additional support to engage fully(Reference Sawyer, McKeon and Hassan64,Reference Naslund, Aschbrenner and Bartels79–Reference Vilardaga, Rizo and Palenski86) .

Although research in this area includes a wide range of age groups, younger adults with SMI are typically inclined to use various types of technology and engage with social media more(Reference Brunette, Achtyes and Pratt87). Despite the existence of training programmes to improve digital skills and confidence among individuals with SMI(Reference Camacho and Torous74,Reference Hoffman, Wisniewski and Hays88) , this area remains underdeveloped and underutilised. Nevertheless, there is evidence that demonstrates that individuals with SMI can and do engage effectively with digital behaviour change interventions(Reference Sawyer, McKeon and Hassan64).

Digital behaviour change interventions in severe mental illness

Health behaviour change interventions include a wide range of psychological strategies aimed at addressing key modifiable health behaviours, including diet, physical activity, smoking, sleep, substance or alcohol use and medication adherence(Reference Sawyer, McKeon and Hassan64). Digital health behaviour change interventions have grown substantially in recent years(Reference Arigo, Jake-Schoffman and Wolin89). A systematic review on digital behaviour change interventions for individuals with SMI found varied outcomes; however, over 90% of studies reported positive shifts in behaviour or attitudes(Reference Sawyer, McKeon and Hassan64). These interventions were generally acceptable, highlighting their potential as a promising approach for addressing health-related behaviours in this population(Reference Sawyer, McKeon and Hassan64). Notably, none of the included studies focused exclusively on digital nutrition interventions, with nutrition or diet typically embedded as part of broader interventions(Reference Naslund, Aschbrenner and Bartels79–Reference Olmos-Ochoa, Niv and Hellemann81,Reference Aschbrenner, Naslund and Barre90–Reference Melamed, Voineskos and Vojtila93) . These multi-component interventions primarily contained nutrition education sessions for individuals with SMI.

A small number of targeted digital nutrition interventions in individuals with SMI have been reported in the literature, including two examples:

-

1. My Food & Mood programme (Reference Young, Mohebbi and Staudacher94): A smartphone-based app designed for adults with depression (>5 on the 8-item patient health questionnaire). It delivered Mediterranean diet modules, and included features such as mood, and food, tracking lifestyle, goal setting and shopping support. Nutritional intake and depression outcomes were measured at baseline, week 4, and week 8, with significant improvements in both. The study demonstrated the feasibility of a digital dietary intervention in this population but also highlighted participation barriers, particularly among those with lower computer confidence who were less likely to enrol.

-

2. Food4Thought (Reference Cheung, Dutta and Kovic95): A remote trainee-led nutrition programme delivered to individuals with SMI and staff. It included modules on nutritional psychiatry, mindful eating, healthy eating on a budget and food as medicine. Following each module the participants completed surveys to assess their attitudes on healthy eating. While the study did not collect objective dietary intake data, it did measure self-reported nutrition-related behaviours such as nutrition label reading, and the perceived impact of food on mood. The programme was well received, and the virtual format was found to be feasible and accessible. However, the small sample size (n = 12) and the requirement for both digital devices and kitchen facilities were limitations.

Together, these examples illustrate the potential of digital nutrition interventions to support individuals with SMI, while also underscoring ongoing challenges in implementation into real-world settings(Reference Smith, Hardy and Vinnikova70). Addressing these challenges reinforces the importance of embedding Public and Patient Involvement (PPI) throughout all stages of the research(Reference Smith, Hardy and Vinnikova70).

Public and patient involvement as a research approach

Implementing this approach requires collaborative methods that integrate PPI, alongside tailored strategies and multidisciplinary collaboration, to effectively translate research findings and digital tools into practical, real-world applications(Reference Smith, Hardy and Vinnikova70). Co-design is a key method that involves meaningful engagement of end users throughout all stages of the research process, including developing solutions to the identified problems(Reference Slattery, Saeri and Bragge96,Reference Vargas, Whelan and Brimblecombe97) . Actively involving users throughout all stages not only results in research that is more relevant and beneficial to the users, but also acknowledges their right to participate in shaping interventions that affect their lives and those around them(Reference Smith, Hardy and Vinnikova70). PPI is classified as a specific type of co-design approach(Reference Slattery, Saeri and Bragge96) and is often defined as: ‘research done “with”or “by”members of the public rather than “to”, “about” or “for” “them”’ (98).

This approach can enhance the quality, value and impact of research(98). PPI also provides significant benefits to contributors themselves, such as increased knowledge and skills, learning opportunities, training, empowerment, networking and relationships, confidence and wellbeing, as well as sharing of expertise and lived experience(98). Individuals involved in PPI may fulfil a range of roles, such as co-researchers or co-applicants, contributing as members of steering or project management groups, participating in advisory panels, or even leading research(98). It is important to acknowledge that PPI contributors give their time, skills and expertise to the research, and should be recognised, valued, and where possible, appropriately rewarded(98). A recent study highlighted the value of PPI in designing web-based physical activity applications in individuals with SMI in Irish mental health residential settings(Reference Forde, Rea and Racine99). Feedback from contributors shaped the app’s design features to better meet the needs and preferences of users(Reference Forde, Rea and Racine99). A useful resource outlining best practices for implementing PPI in research is available from the HSE(98).

One major contributor to research inefficiency and wasted funding is the focus on questions and outcomes that have limited relevance to clinicians, patients and other users, often paired with poor design(Reference Slattery, Saeri and Bragge96,Reference Ioannidis100) . This suggests that a considerable amount of health research may be insufficient from the outset, primarily because researchers frequently do not engage with the clinicians, stakeholders and other end users during the planning or design phases of research(Reference Chalmers and Glasziou101). It is essential for nutrition researchers to report co-design methods in a systemically and transparent way to ensure learnings and reproducibility(Reference Needham, Partridge and Alston102). The GRIPP2 reporting checklist(Reference Staniszewska, Brett and Simera103), the first international guidance for documenting PPI in health and social care research, was developed to support greater quality, transparency and consistency. However, a recent review highlights that PPI is still infrequently reported using the GRIPP2, highlighting the need for researchers, funders, publishers and journals to actively promote consistent and transparent reporting through the use of internationally recognised tools(Reference Hammoud, Alsabek and Rogers104).

While co-design approaches offer clear advantages, a review of health research co-design projects highlighted that initiating and sustaining collaboration frequently presents difficulties(Reference Slattery, Saeri and Bragge96). As many of these challenges are partly behavioural in nature, it has been recommended that researchers incorporate behavioural science to guide their approach(Reference Slattery, Saeri and Bragge96).

Behavioural science and theoretical frameworks

Behavioural science plays a critical role at every stage of the process, from generating evidence through primary research, to synthesising findings in reviews, translating evidence into guidelines and recommendations and ultimately implementing them in practice(Reference Michie105). The application of theory is considered a critical component to the design, evaluation and synthesis of interventions(Reference Davis, Campbell and Hildon106). Given the complexity of human behaviour, particular in individuals with SMI, understanding behaviours and the contexts in which they take place is fundamental to developing effective, evidence-based interventions(Reference Davis, Campbell and Hildon106).

Implementation frameworks offer a structured approach to describing, guiding, analysing and evaluating implementation efforts, thereby supporting the development of generalisable implementation knowledge(Reference Ferron, Brunette and McHugo82). Ideally, such frameworks should be employed both during the planning stage and throughout the implementation process(Reference Moullin, Dickson and Stadnick107). When used in research settings, implementation frameworks can shape study design, inform theoretical and empirical perspectives and support the interpretation of findings(Reference Moullin, Dickson and Stadnick107).

The behaviour change wheel framework

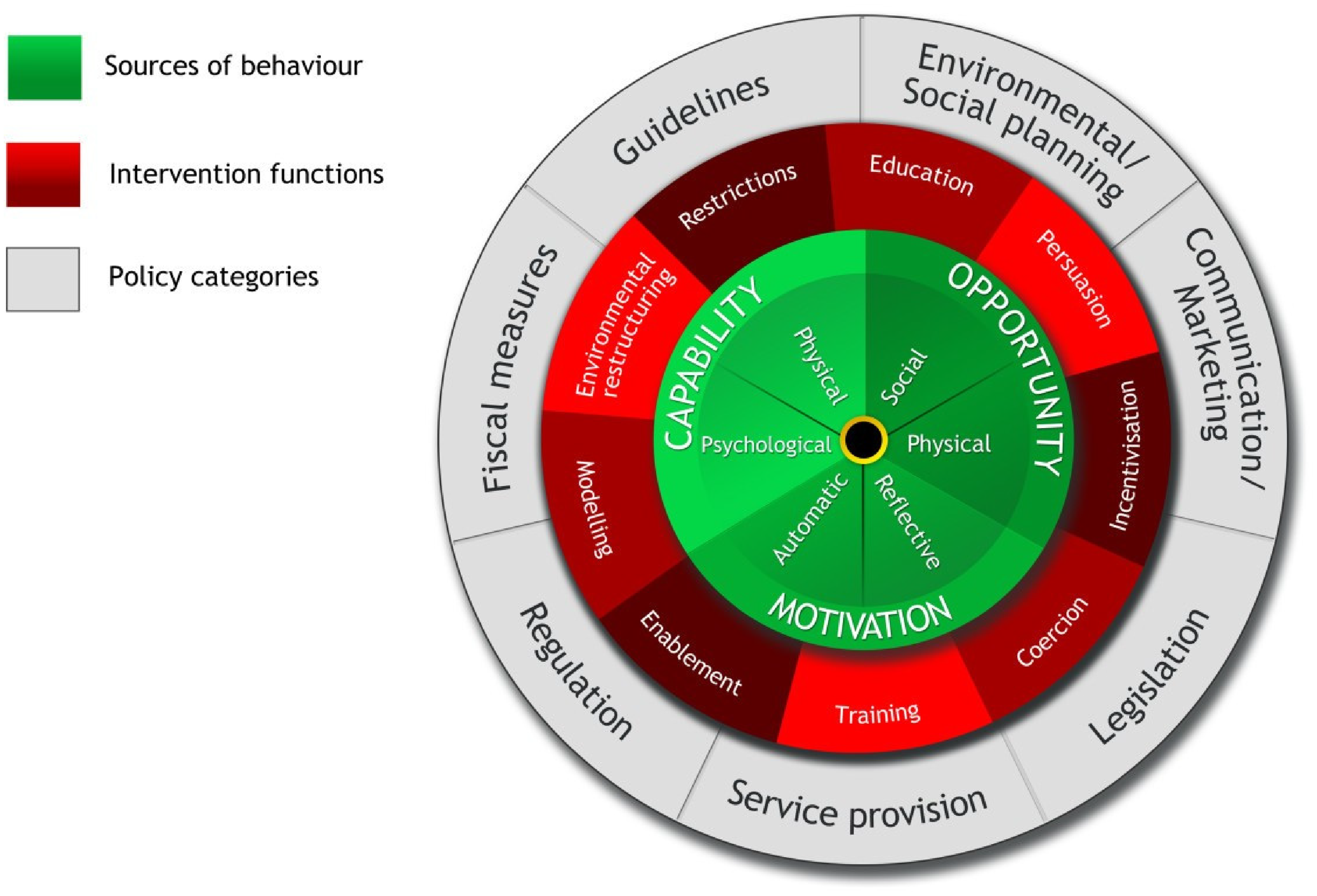

One widely used and comprehensive framework is the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) (Figure 1) developed by Michie, Atkins and West (2011)(Reference Michie, Van Stralen and West108). Synthesising 19 behaviour change frameworks, the BCW offers a systematic process to assist from understanding a behavioural problem to evidence-based strategies(Reference Barker, Atkins and De Lusignan109). At the centre of the BCW lies the COM-B model – Capability, Opportunity, Motivation as the fundamental drivers of behaviour(Reference Michie, Van Stralen and West108).

Fig. 1. The behaviour change wheel.

Source: Reproduced in its original form from Michie et al., (2011)(Reference Michie, Van Stralen and West108), Implementation Science, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution (CC. BY. 2.0).

Surrounding this core is a middle layer of nine intervention functions designed to address limitations in capability, opportunity, or motivation. The outer layer includes seven categories of policy approaches that can be used to support and implement these intervention functions(Reference Michie, Van Stralen and West108,Reference Michie, Atkins and West110) .

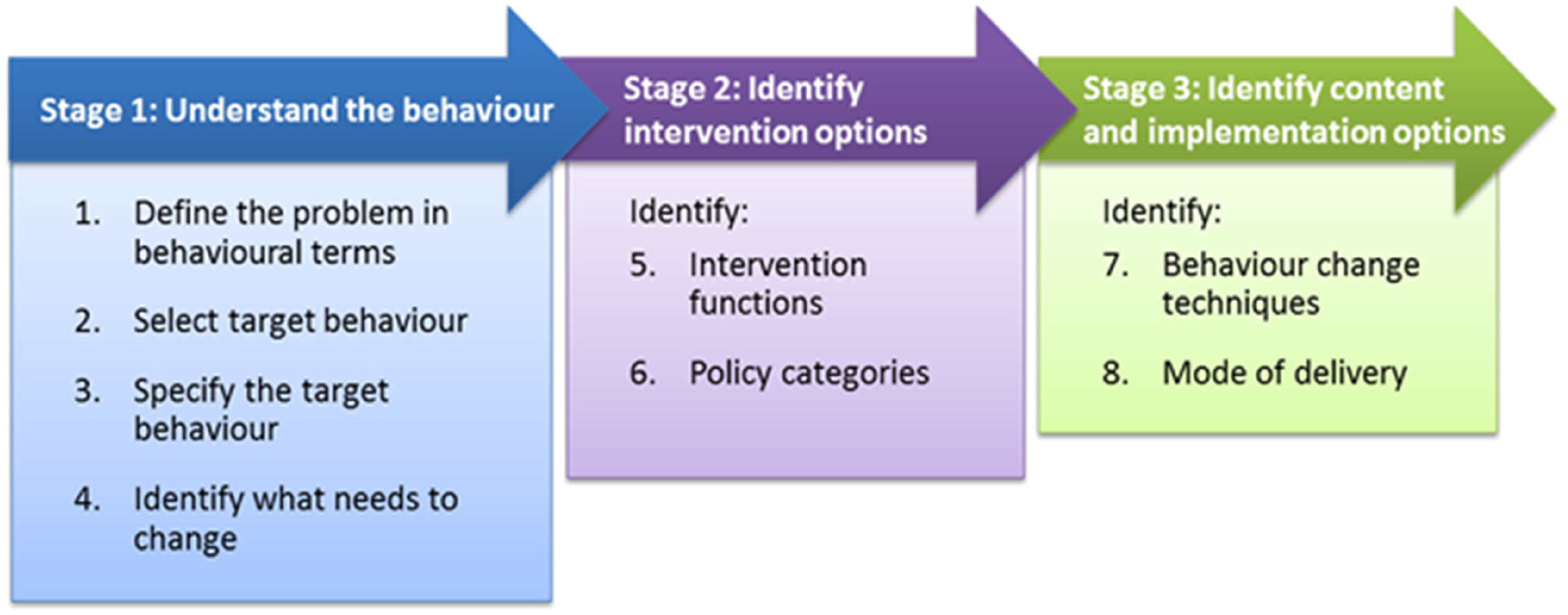

Building on from this, Michie and colleagues outlined a step-by-step method for designing behaviour change interventions, consisting of three stages and eight steps(Reference Michie, Atkins and West110) (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Behaviour change wheel step-by-step method.

Source: Michie S, Atkins L, West R. (2014)(Reference Michie, Atkins and West110) The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions. London: Silverback Publishing. www.behaviourchangewheel.com.

These stages are: (1) Understand the behaviour, (2) Identify intervention options, (3) Identify content and implementation options. Although presented in linear sequence, the process often requires an iterative approach, with movement back and forth between steps as new challenges and insights emerge(Reference Michie, Atkins and West110). While not a ‘magic bullet’, this approach offers a structured method for effectively maximising knowledge and resources to design effective behaviour change interventions(Reference Michie, Atkins and West110).

The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) encompasses 128 theoretical concepts derived from 33 behaviour change theories, and organised into 14 domains(Reference Atkins, Francis and Islam111). The domains include social influences, environmental context and resources, social/professional role and identity, belief about capabilities, optimism, intention, goals, emotion, knowledge, cognitive and interpersonal skills, memory, attainment and decision-making processes, behavioural regulation and physical skills(Reference Atkins, Francis and Islam111). When used in conjunction with the BCW, the TDF allows for a deeper understanding of factors that influence behaviour change(Reference Atkins, Francis and Islam111). Examples of studies applying the COM-B with the TDF in dietary contexts highlight their value in informing intervention development(Reference Bentley, Mitchell and Sutton112,Reference Timlin, McCormack and Simpson113) .

Our ongoing work reflects this integrated approach. The published protocol for co-designing a digital nutrition interventions for individuals with SMI(Reference O’Sullivan, Coppinger and Dhanapala114), illustrates how behavioural science frameworks such as the BCW, can be systematically embedded into intervention development in collaboration with PPI.

Future directions for digital nutrition interventions in severe mental illness

This review highlights critical areas for advancing both existing and current research and practice in digital nutrition interventions for individuals with SMI. As highlighted, existing nutrition interventions have often focused on weight loss or weight management(Reference Burrows, Teasdale and Rocks52), which may not be the most appropriate outcome, potentially neglecting broader nutritional needs. Future interventions should adopt a more holistic perspective, expanding beyond weight management, as exemplified by the HELFIMED study discussed earlier.

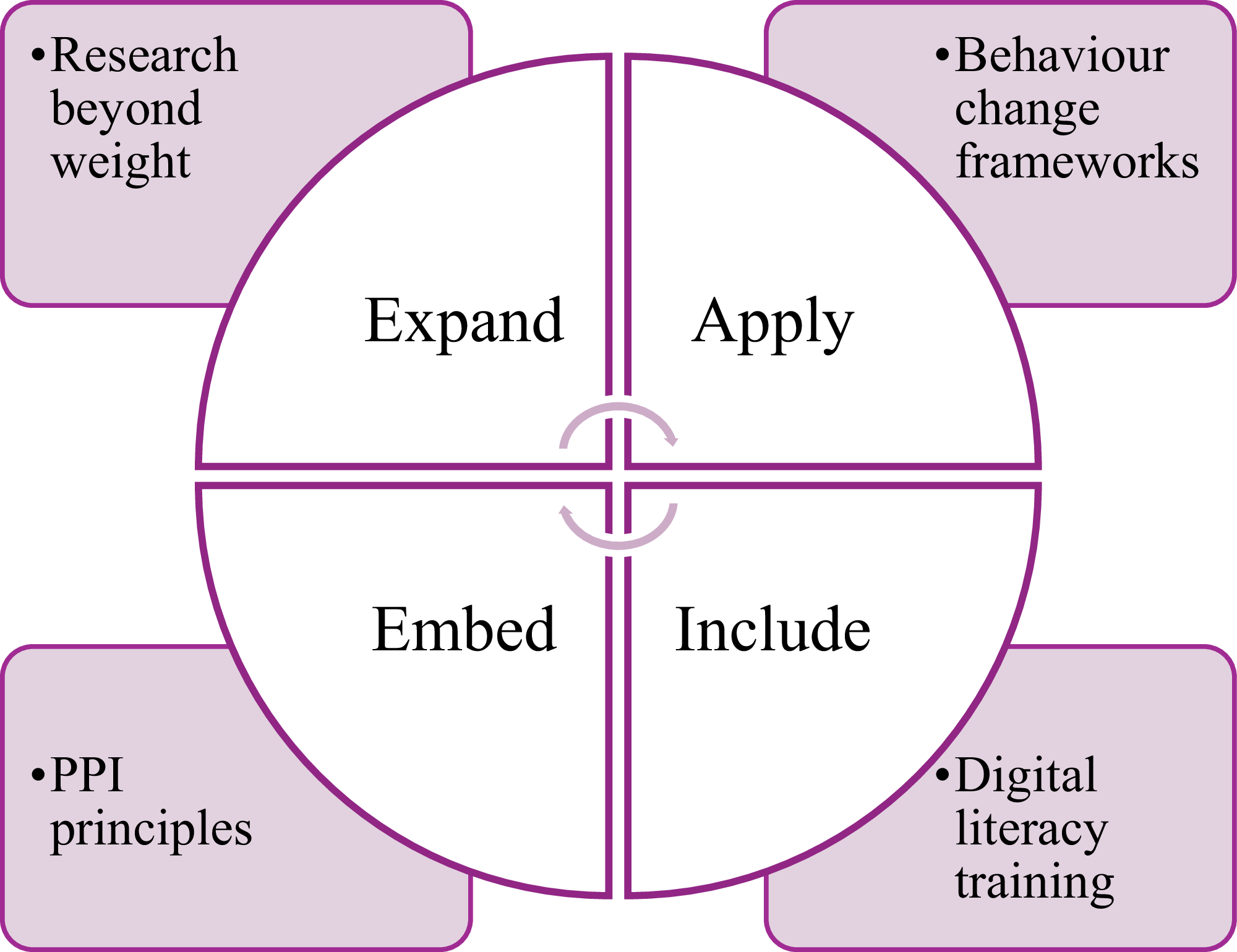

A key barrier to implementation of digital interventions is low digital literacy(Reference Spanakis, Lorimer and Newbronner72). Including digital literacy training can enhance the accessibility, usability and engagement of these tools. Equally as important is the meaningful embedment of PPI principles across all stages of the research process(98). Engaging with PPI participants helps ensure that interventions are relevant, acceptable, and can also improve the quality, value and impact of the research(98). Applying behavioural science frameworks, particularly the BCW can offer an evidence-based approach for designing behaviour change interventions, while optimising the design and effectiveness of such interventions(Reference Michie, Van Stralen and West108,Reference Michie, Atkins and West110) .

Ultimately, advancing digital nutrition support for individuals with SMI will require a collaborative, interdisciplinary effort to co-design solutions that are both scalable and impactful. Key recommendations are summarised in Figure 3.

Fig. 3. Key recommendations for future digital nutrition interventions for individuals with SMI.

Source: Developed by the author.

Conclusion

Individuals with SMI experience significant health inequalities, with poor nutrition a key modifiable contributor. Although traditional interventions offer benefits, they often face difficulties when implementing. Digital technology offers a promising avenue for delivering accessible, scalable nutrition support to individuals with SMI, yet its potential remains largely underutilised. Current evidence, although limited, suggests that these digital nutrition interventions can both be feasible and acceptable when appropriately designed. Future efforts must expand beyond weight management to address broader nutritional needs. Applying behavioural science frameworks and embedding meaningful PPI into the design and delivery of digital nutrition interventions is critical to enhancing relevance, usability and make a lasting impact in this underserved population.

Finally, persistent barriers such as digital exclusion, low digital literacy and implementation challenges must be addressed, with digital training actively included to improve engagement and accessibility. By focusing on these core strategies – expand, embed, apply and include – digital nutrition interventions can help improve health outcomes and reduce inequalities among individuals with SMI.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Irish Section of the Nutrition Society for the invitation to present this review paper as part of the postgraduate review competition.

Author contributions

C.O.S drafted the manuscript. A.M and T.C critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This publication has emanated from research conducted with the financial support of Taighde Éireann – Research Ireland under Grant number 18/CRT/6222. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interests.