Introduction

Using public transport is among the most effective individual actions for reducing emissions in the transport sector and has the largest reduction potential of all options across sectors aimed at shifting demand (Ivanova et al., Reference Ivanova, Barrett, Wiedenhofer, Macura, Callaghan and Creutzig2020; Creutzig et al., Reference Creutzig, Roy, Devine-Wright, Díaz-José, Geels, Grubler, Maïzi, Masanet, Mulugetta, Onyige, Perkins, Sanches-Pereira, Weber, Shukla, Skea, Al Khourdajie, van Diemen, McCollum, Pathak, Some, Vyas, Fradera, Belkacemi, Hasija, Lisboa, Luz and Malley2022). Demand-side solutions seek to facilitate such behavioral change (Creutzig et al., Reference Creutzig2018; Reisch et al., Reference Reisch, Sunstein, Andor, Doebbe, Meier and Haddaway2021). In principle, modal shifts can be promoted either by discouraging car use (push measures) or by increasing the attractiveness of public transport (pull measures; Zarabi et al., Reference Zarabi, Waygood, Olsson, Friman and Gousse-Lessard2024). However, both approaches have limitations. Traditional push measures, such as congestion pricing or driving restrictions, are often perceived as freedom-restricting and face low social acceptance.Footnote 1 Pull measures, by contrast, tend to involve high costs while delivering limited effectiveness (Schade, Reference Schade, Schade and Schlag2003; Gaunt et al., Reference Gaunt, Rye and Allen2007; Lanzendorf et al., Reference Lanzendorf, Baumgartner and Klinner2023; Mehdizadeh et al., Reference Mehdizadeh, Solbu, Klöckner and Moe Skjølsvold2024). Even the effectiveness of fare-free public transport, the arguably most radical pull measure to promote public transport, falls short of expectations: a review of nearly 100 trials worldwide indicates that while such policies typically lead to substantial ridership increases, these are largely driven by additional trips and shifts from cycling or walking rather than significant reductions in car use (Kębłowski, Reference Kębłowski2020).

In other policy areas, attention has been focused on alternative demand-side instruments such as ‘nudges’, which are valued for cost-effectiveness and preservation of choice (Thaler and Sunstein, Reference Thaler and Sunstein2008; Reisch et al., Reference Reisch, Sunstein, Andor, Doebbe, Meier and Haddaway2021). Studies highlight the potential of such behaviorally informed interventions to increase public transport use, especially when information is tailored and effectively framed and timing is considered (Kormos et al., Reference Kormos, Sussman and Rosenberg2021). At the same time, scholars underscore the complexity of changing transport behavior (Arnott et al., Reference Arnott, Rehackova, Errington, Sniehotta, Roberts and Araujo-Soares2014). For instance, behaviorally informed interventions faced difficulties in changing behavior when confronted with strong habits (e.g., in the case of commuting), conflicting self-interests or opposing incentives (Lieberoth et al., Reference Lieberoth, Holm Jensen and Bredahl2018; Kristal and Whillans, Reference Kristal and Whillans2019; Gravert and Olsson Collentine, Reference Gravert and Olsson Collentine2021). For this reason, using behaviorally informed interventions to enhance traditional policy instruments is considered an effective option (Khanna et al., Reference Khanna, Baiocchi, Callaghan, Creutzig, Guias, Haddaway, Hirth, Javaid, Koch, Laukemper, Löschel, Zamora Dominguez and Minx2021; Composto and Weber, Reference Composto and Weber2022).

Against this background, this study aims to improve the understanding of how behavioral science can be used to strengthen traditional public transport policies. Specifically, it examines the role of nonmonetary attributes of flat-fare public transport tickets in promoting their use. Accordingly, the research question is: To what extent do behaviorally alignedFootnote 2 attributes influence the use of flat-fare public transport tickets, and how does the role of these attributes differ across user groups?

To address this research question, the study employs a representative survey of flat-fare public transport ticket users, administered by a professional market research provider. The questionnaire includes attributes reflecting the dimensions of the EAST framework, which posits that effective interventions should be easy, attractive, social and timely (BIT, 2014). The ‘Deutschlandticket’ serves as the case study. Introduced in May 2023, this flat-fare ticket allows for unlimited use of public transport across Germany (excluding long-distance services) for a monthly fee of 49 euros (63 euros since 2026). The Deutschlandticket succeeded the temporary ‘9-Euro-Ticket’ introduced in summer 2022 to mitigate rising living costs and support public transport recovery after the COVID-19 pandemic. This earlier measure attracted substantial public and academic attention (Bissel, Reference Bissel2023; Milner and Wolff, Reference Milner and Wolff2023; Loder et al., Reference Loder, Cantner, Adenaw, Nachtigall, Ziegler, Gotzler, Siewert, Wurster, Goerg, Lienkamp and Bogenberger2024).

The contributions of this study are threefold. First, by analyzing a behaviorally aligned transport policy, it bridges the gap between nudging interventions and traditional policy instruments, illustrating how behavioral science can strengthen such policy instruments. This responds to recent calls for research (Cherry and Kallbekken, Reference Cherry and Kallbekken2023; Johnson and Mrkva, Reference Johnson and Mrkva2023; Zhao and Chen, Reference Zhao and Chen2023). Second, in terms of practical implications, the study goes beyond pricing by focusing on nonmonetary attributes of public transport tickets, thereby providing insights to improve the cost-effectiveness of transport policies (Alta Planning & BIT, 2017; Whillans et al., Reference Whillans, Sherlock, Roberts, O’Flaherty, Gavin, Dykstra and Daly2021). Third, the study advances research by systematically and empirically applying the EAST framework to a single intervention. While the framework has proven valuable in other policy domains (Arboleda et al., Reference Arboleda, Jaramillo, Velez and Restrepo2024), its application in public transport has so far been limited to anecdotal evidence and illustrative examples (Alta Planning & BIT, 2017)

Behavioral science and public transport

Insights from behavioral science, particularly on bounded rationality and social preferences, provide valuable complements to the traditional rational decision models that inform transport policy (Avineri, Reference Avineri2012; Metcalfe and Dolan, Reference Metcalfe and Dolan2012; Garcia-Sierra et al., Reference Garcia-Sierra, van den Bergh and Miralles-Guasch2015).Footnote 3 For example, mode choice is influenced by habits and the status quo bias (Samuelson and Zeckhauser, Reference Samuelson and Zeckhauser1988; Garcia-Sierra et al., Reference Garcia-Sierra, van den Bergh and Miralles-Guasch2015). Individuals also tend to overestimate the cost of using public transport on a pay-per-use basis and to underestimate the cost of car ownership (Gaker and Walker, Reference Gaker, Walker, Lucas, Blumenberg and Weinberger2011; Andor et al., Reference Andor, Gerster, Gillingham and Horvath2020). This finding can be explained by the overweighting of frequent small losses, as described by the prospect theory, and separate mental accounts for one-time payments and frequent expenditures (Kahneman and Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979; Thaler, Reference Thaler1985; Gaker and Walker, Reference Gaker, Walker, Lucas, Blumenberg and Weinberger2011; Garcia-Sierra et al., Reference Garcia-Sierra, van den Bergh and Miralles-Guasch2015).

These concepts are also relevant for the so-called ‘flat-rate bias’, which describes the tendency of consumers to choose flat-rate tariffs even if they are more expensive (Train, Reference Train1991, p. 211). While this phenomenon also corresponds to traditional economic concepts such as (mental) transaction costs and option value, it is often considered ‘irrational’ (Geurs et al., Reference Geurs, Haaijer and Van Wee2006; Levinson and Odlyzko, Reference Levinson and Odlyzko2008). Behavioral science suggests several underlying effects (Lambrecht and Skiera, Reference Lambrecht and Skiera2006): First, flat-rates may provide loss-averse individuals with ‘insurance’ against fluctuating payments. Second, such tariffs make usage feel ‘free’ due to separated mental accounts (taxi meter effect). Third, flat-rates reduce decision-making effort and are convenient. Fourth, consumers may overestimate actual usage. Lastly, the upfront payment may represent an active commitment, the so-called self-discipline effect (Wirtz et al., Reference Wirtz, Chlond and Vortisch2015).

The Deutschlandticket in the light of the EAST framework

As described in this section, the EAST framework provides a suitable basis for identifying behaviorally aligned attributes of the Deutschlandticket (see Table 1).

Table 1. Overview of the Deutschlandticket in light of the EAST principles

a Definition based on BIT (2014); italic: attributes included in empirical analysis.

Easy

Prior to the introduction of the Deutschlandticket, public transport in Germany was a ‘tariff jungle’, in which traveling was complicated by more than 70 transit districts, each with distinct fare systems (Pucher and Kurth, Reference Pucher and Kurth1995; Nobis and Kolarova, Reference Nobis and Kolarova2022; Loder et al., Reference Loder, Cantner, Dahmen and Bogenberger2023). As shown in Figure 1, while the transit districts still exist, the Deutschlandticket simplifies public transport usage by offering a nationwide, easy-to-use ticket that is valid for unlimited journeys (Loder et al., Reference Loder, Cantner, Dahmen and Bogenberger2023). The ticket can be purchased and used through multiple apps and is often directly recommended (Motzer et al., Reference Motzer, Hamel, Agola, Riedel, Wagner-Hanl and Stein2024). In addition, the automatic monthly renewal creates a status quo effect.

Figure 1. Comparison of the tariff structure before and after the Deutschlandticket.

Attractive

In addition to the distinctive name and logo (see Figure 1), researchers emphasize the psychological role of the ticket’s pricing. Besides the flat-fare, this refers to the ticket’s memorable sequence of numbers (Krämer, Reference Krämer2023), as it was commonly referred to as the ‘49-Euro-Ticket’ (Agola et al., Reference Agola, Hamel and Amorim2025). Lastly, in line with the EAST framework (BIT, 2014), the name ‘Deutschlandticket’ increases the salience of its nationwide validity.

Social

The temporary predecessor, the 9-Euro-Ticket, triggered a public discourse on the societal role of public transport, which led to more positive perceptions (Loder et al., Reference Loder, Cantner, Dahmen and Bogenberger2023). This discussion also addressed social norms and transport modes as symbols of social status (Milner and Wolff, Reference Milner and Wolff2023) and contributed to the country’s transition to sustainable mobility (Krämer et al., Reference Krämer, Wilger and Bongaerts2022). Given the prominent role of the Deutschlandticket in this ongoing discourse, the ticket can be seen as an example of how individuals are attempting to contribute to the mobility transition.

Timely

The ‘timely’ dimension is based on the finding that consumers are more receptive to changing routines at certain points in time (Bamberg, Reference Bamberg2006). Researchers have argued that the end of the COVID-19 pandemic provided an opportunity to change mobility routines (Kormos et al., Reference Kormos, Sussman and Rosenberg2021; BIT & ECCC, 2022). As mentioned above, the temporary predecessor of the Deutschlandticket was introduced during such a period of volatility. Since the 9-Euro-Ticket acted as a ‘door opener’, it can be seen as a positive effect of timing if the Deutschlandticket is used due to experiences with the 9-Euro-Ticket (Motzer et al., Reference Motzer, Hamel, Agola, Riedel, Wagner-Hanl and Stein2024).

Hypotheses

Considering the large number of behaviorally aligned attributes in line with the EAST framework in combination with the general potential of such attributes (BIT, 2014; Alta Planning & BIT, 2017), we hypothesize that these attributes are key reasons for using the Deutschlandticket (H1).

Second, we test two hypotheses stating that the role of behaviorally aligned attributes differs between user groups. This relates to new subscribers compared to existing subscribers (H2a) and individuals of different income groups (H2b). With regard to H2a, Loder et al. (Reference Loder, Cantner, Dahmen and Bogenberger2023) argue that aspects such as simplification can play an important role in attracting new customers. This hypothesis seems plausible since, as outlined before, complexity of the public transport system represented a key barrier to public transport use in Germany. In addition, social influences and timely interventions to break routines are considered important aspects to change the behavior of individuals who previously did not possess a public transport season ticket (Bamberg, Reference Bamberg2006; Garcia-Sierra et al., Reference Garcia-Sierra, van den Bergh and Miralles-Guasch2015; Alta Planning & BIT, 2017). Therefore, we hypothesize that behaviorally aligned attributes, especially those related to simplification, are particularly important for new subscribers without previous season tickets compared to existing subscribers. Regarding H2b, the reason to use the Deutschlandticket for users of different income groups was a heavily discussed topic in debates on the right pricing of the ticket, which also relates back to the social objectives of the 9-Euro predecessor (Loder et al., Reference Loder, Cantner, Dahmen and Bogenberger2023). Scholars argued that the price of flat-fare tickets, if sufficiently low, represents the most important attribute for lower-income individuals, whereas behaviorally aligned attributes such as simplicity and social signaling might be more important for individuals with higher financial means (Hille and Gather, Reference Hille and Gather2022; Aberle et al., Reference Aberle, Havemann, Weissinger and Porsche2023; Agola et al., Reference Agola, Hamel and Amorim2025). For this reason, we test whether behaviorally aligned attributes are more important for individuals in higher than in lower income groups.

Third, referring to the ‘flat-rate bias’ and individual preferences for flat-rate products beyond actual usage (Lambrecht and Skiera, Reference Lambrecht and Skiera2006), we test the hypothesis that the stated importance of behaviorally aligned attributes exceeds their stated use (H3).

Methodology

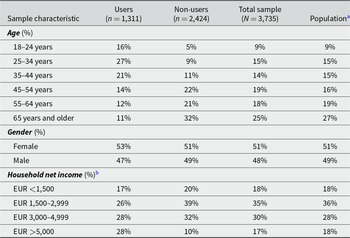

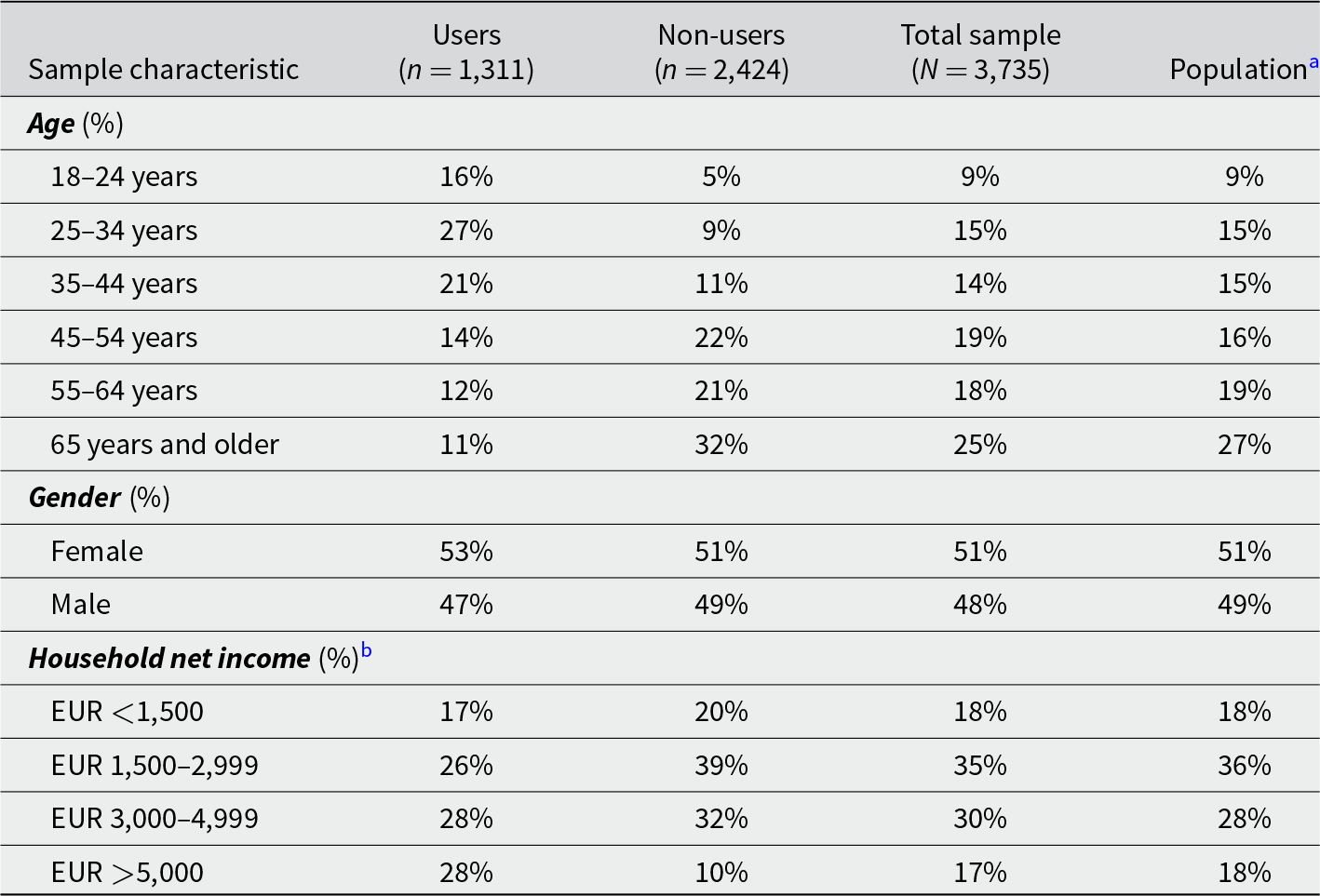

To ensure a high-quality, population-representative sample, data were collected by the professional market research company Cint using the online panel platform Cint exchange (Cint, 2025). Based on the panel, the sample was created using independent quotas for gender, age and primary residence in the federal states building on the latest census data (Federal Statistical Office, 2022). Data were collected from 3 August to 16 August 2023, 4 months after the start of the Deutschlandticket. To test for representativeness in terms of income, the income variable was recoded prior to data analysis to match categories of the census. As shown in Table 2 (together with additional characteristics of the sample), the sample is highly representative regarding income.

Table 2. Overview of sample characteristics

Of the 3,735 respondents included in the analysis, 1,311 (35%) were categorized as Deutschlandticket users who held a ticket in at least one of the 4 months since its launch. Of these, 48% were new subscribers who did not previously hold a public transport season ticket. 37% were categorized as existing subscribers whose season ticket was automatically converted to a Deutschlandticket (i.e., without an active decision to opt-in). Lastly, 15% were existing subscribers who previously held a public transport season ticket and actively switched to the Deutschlandticket (e.g., by cancelling the previous subscription and purchasing the Deutschlandticket).

The questionnaire included sociodemographic factors, details about mobility behavior, reasons to use the Deutschlandticket and psychological variables such as social norms. An English translation of the items and scales used in this study is provided in the supplementary material. A comprehensive descriptive overview of the survey results was provided in a report by the Fraunhofer Transport Alliance (Motzer et al., Reference Motzer, Hamel, Agola, Riedel, Wagner-Hanl and Stein2024).

For the purpose of this study, the authors (of which two authors contributed to the initial report) were granted permission to re-analyze the relevant subset for the objectives of the current study. In particular, this referred to the question on reasons to use the Deutschlandticket. In this survey item, respondents were asked to select all relevant reasons for using the Deutschlandticket from a list of 10 options that were developed in line with previous research on the Deutschlandticket (e.g., VDV et al., 2022). These options were mapped on the categories of the EAST framework building on a previous conceptual, literature-driven publication by one of the authors (Bissel and Gossen, Reference Bissel and Gossen2023) that discussed behaviorally aligned characteristics of the Deutschlandticket and provided hypotheses on their respective roles for using the Deutschlandticket. Building on this a priori publication of the categorization, 8 survey options were mapped on the EAST categories (and an additional 'economic' category) before data analyses in a joint effort by the entire author team until consensus was reached. Two optionsFootnote 4 were rated to be not in scope of the EAST framework and were therefore not included in the analysis. More information on the options, as well as other items used for this study, is provided in the supplementary material.

Results

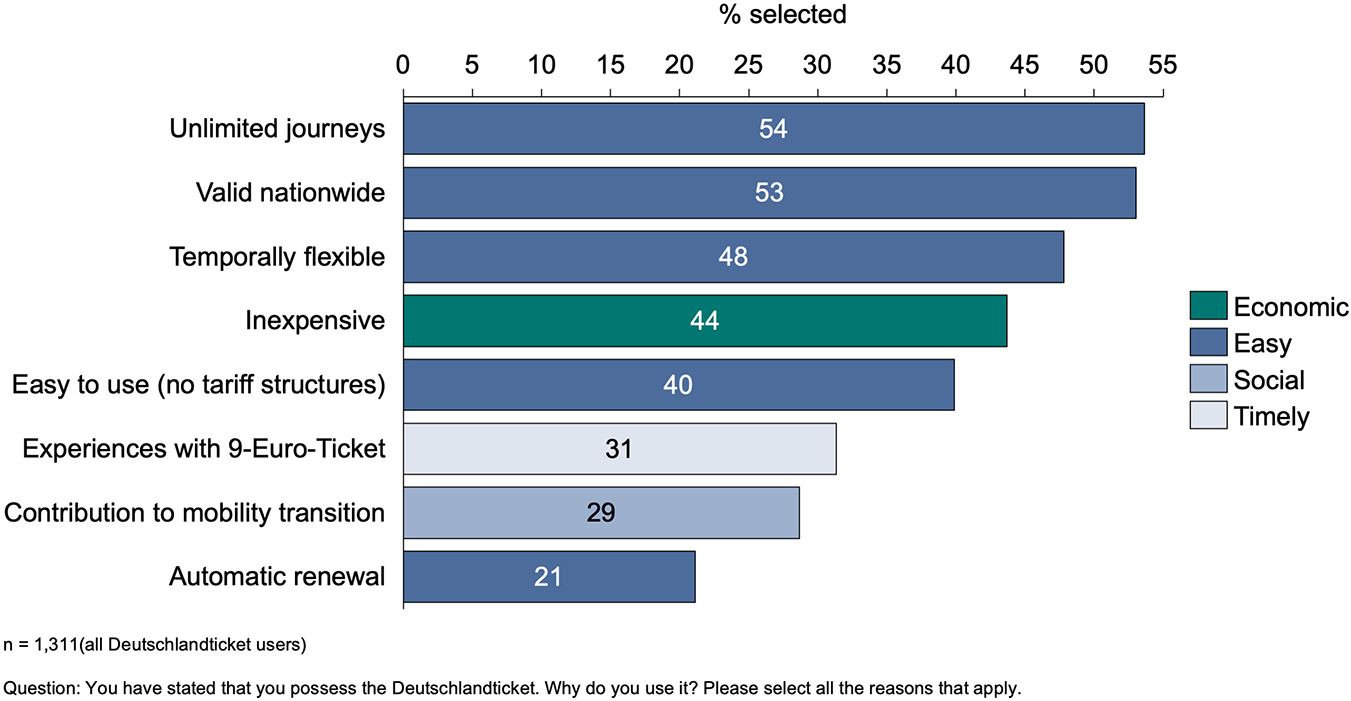

Overall role of behaviorally aligned attributes

With regard to hypothesis 1, Figure 2 shows that three attributes classified as ‘easy’ according to the EAST framework, namely ‘unlimited journeys’, ‘valid nationwide’ and ‘temporally flexible’, are the most frequently selected reasons for using the Deutschlandticket. These attributes even exceed the economic attribute ‘inexpensive’. With regard to the ‘timely’ introduction, the share of respondents who explicitly cited their experience with the 9-Euro-Ticket as a reason for using the Deutschlandticket is 31%. The ‘social’ attribute of ‘contributing to the mobility transition’ as well as the ‘automatic renewal’ feature were rated as less important by the total sample.

Figure 2. Overall reasons for using the Deutschlandticket.

Importance of behaviorally aligned attributes by user group

To test hypotheses 2a and 2b, we compared attribute importance between user groups using chi-squared tests for independent samples. This nonparametric test was chosen in view of the binary outcome variables and the aggregated structure of the dataset in combination with the large sample size. With regard to new vs existing subscribers (H2a),Footnote 5 as shown in Figure 3, new subscribers selected most ‘easy’ attributes statistically significantly more frequently than existing subscribers. This relates to ‘easy to use’ (X 2 [1, N = 1,080] = 6.71, p = 0.010), ‘unlimited journeys’ (X 2 [1, N = 1,080] = 23.91, p < 0.001) and ‘temporally flexible’ (X 2 [1, N = 1,080] = 15.59, p < 0.001). In contrast, the group difference for ‘automatic renewal’ was not found to be statistically significant (X 2 [1, N = 1,080] = 0.79, p = 0.375). Statistically significant differences were also found for the ‘timely’ (X 2 [1, N = 1,080] = 9.66, p = 0.002) and the ‘economic’ attribute (X 2 [1, N = 1,080] = 5.10, p = 0.024), but not for the ‘social’ attribute (X 2 [1, N = 1,080] = 0.07, p = 0.794).

Figure 3. Usage reasons of the Deutschlandticket for new vs existing subscribers.

In terms of income (H2b), respondents in the highest income group mentioned the three most important attributes (all ‘easy’) less frequently than all other income groups (Figure 4). Chi-squared tests revealed statistically significant differences for ‘unlimited journeys’ (X 2 [1, N = 1,252] = 28.69, p < 0.001) and ‘valid nationwide’ (X 2 [1, N = 1,252] = 16.80, p < 0.001), but not for ‘temporally flexible’ (X 2 [1, N = 1,252] = 1.21, p = 0.272), when comparing the highest income group with the remaining sample. While ‘inexpensive’ was selected less frequently by both outer income groups, this difference is only statistically significantly different from the rest of the sample for the highest income group (X 2 [1, N = 1,252] = 18.42, p < 0.001), but not for the lowest (X 2 [1, N = 1,252] = 1.10, p = 0.294). Finally, ‘contribution to mobility transition’ (X 2 [1, N = 1,252] = 4.57, p = 0.032) and ‘automatic renewal’ (X 2 [1, N = 1,252] = 11.79, p < 0.001) were selected statistically significantly more often by the highest income group compared to the rest of the sample.

Figure 4. Usage reasons of the Deutschlandticket by income group.

Comparison of stated importance with stated usage

The two overall most frequently cited reasons for use, ‘unlimited journeys’ and ‘valid nationwide’, simplify public transport use and reduce frictions. In addition, these attributes increase the utility derived from the ticket. If this benefit is fully exploited, participants choosing these attributes would be expected to use the ticket accordingly. Conversely, if the ticket does not lead to more or more distant trips, respondents would be expected to limit their selection to other attributes such as ‘inexpensive’.

Therefore, to test hypothesis 3, the stated importance of these attributes was compared with stated usage based on McNemar’s tests. The McNemar’s test was selected to allow for paired sample analyses under the aforementioned constraints of the variables and the dataset. Figure 5 illustrates that while 54% of respondents cited ‘unlimited journeys’ as a key usage reason, only 46% reported an increase in public transport use. The discrepancy is even more pronounced for nationwide validity: 60% mentioned it as important but only 23% used the ticket for trips in non-adjacent areas. Both effects are statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Figure 5. Usage reasons compared to stated usage of the Deutschlandticket.

Discussion

This article examined the Deutschlandticket from a behavioral public policy perspective. Regarding hypothesis 1, the results indicate that many of the identified behaviorally aligned attributes, especially those related to ease of use (i.e., unlimited journey, nationwide validity, temporal flexibility), are essential reasons for using the Deutschlandticket and in part even considered more important than the price. While previous studies indicate that approximately 9 out of 10 Deutschlandticket users also purchased the 9-Euro-Ticket (Hamel et al., Reference Hamel, Agola and Amorim2025), the present analysis indicates that the ‘timely’ introduction of the Deutschlandticket was considered a relevant attribute by at least about one-third of respondents.

Moreover, with regard to hypothesis 2a, the majority of these attributes were found to be particularly important to new subscribers. This relates to most ‘easy’ attributes as well as the ‘timely’ introduction in a period of change, highlighting the potential of behaviorally aligned transport policies to attract new subscribers. Regarding differences by income group (H2b), the results reveal a nuanced picture: while individuals in the highest income group put less emphasis on key ‘easy’ attributes such as ‘unlimited journeys’ and ‘nationwide validity’ than individuals with lower income, they statistically significantly more often stated other ‘easy’ aspects such as the automated renewal as well as the ‘social’ aspect of contributing to the mobility transition as important. This underscores the assumption that behaviorally aligned attributes differ in their relevance by income group (Agola et al., Reference Agola, Hamel and Amorim2025).

Finally, in accordance with hypothesis 3, the stated importance ascribed to these attributes was found to significantly exceed stated usage. This finding, while not necessarily irrational, corresponds to the ‘flat-rate bias’, extending studies from other domains and on geographically limited flat-fare public transport (Wirtz et al., Reference Wirtz, Chlond and Vortisch2015).

Potential of behaviorally aligned public transport tariffs

Flat-fare tickets can be an attractive and effective policy instrument and a cost-effective alternative to fare-free public transport. For instance, an impact evaluation indicates that the Deutschlandticket reduced car traffic by 7.6% and transport-related CO2 emissions by 4.7% in its first year (Amberg and Koch, Reference Amberg and Koch2024). This is consistent with the data underlying the present study (Hamel et al., Reference Hamel, Agola and Amorim2025). Notably, building on the aforementioned theoretical concepts, flat-fare tickets may be even more effective in inducing a modal shift, as the one-time payment followed by zero marginal cost results in a commitment similar to car ownership (Wirtz et al., Reference Wirtz, Chlond and Vortisch2015; Loder et al., Reference Loder, Cantner, Adenaw, Nachtigall, Ziegler, Gotzler, Siewert, Wurster, Goerg, Lienkamp and Bogenberger2024).

Limits of behaviorally aligned public transport tariffs

Public transport usage depends on a number of factors (Batty et al., Reference Batty, Palacin and González-Gil2015; Javaid et al., Reference Javaid, Creutzig and Bamberg2020). Flat-fare tickets do not address key issues such as network density, resulting in urban–rural disparities. Without additional measures, as described elsewhere based on this survey, flat-fare tickets risk becoming a ‘lifestyle product’ for privileged citizens (Agola et al., Reference Agola, Hamel and Amorim2025). As a ‘pull’ measure, they also do not discourage car use (Loder et al., Reference Loder, Cantner, Dahmen and Bogenberger2023). This is particularly noteworthy given the interacting ‘commitment’ effects of car and season ticket ownership on mode choice (Axhausen et al., Reference Axhausen, Simma and Golob2000).

Implications for practitioners and policymakers

While our study highlights the potential of behaviorally aligned tariff policies in an ex post analysis, the results underscore the general importance of integrating behavioral insights into transport policy. To fully realize this potential, behavioral insights should be integrated ex ante in behaviorally informed policies (European Commission, 2016) and adopted as a lens in the policymaking process (Hallsworth, Reference Hallsworth2023). In addition, the value created by behaviorally aligned attributes needs to be assessed in policy evaluations and considered in the context of discussions on pricing. Notably, as the results of this study indicate, the impact of behaviorally aligned attributes may differ by user group. While flat-fare tickets are one approach to apply behavioral insights, other options include simplifying payments (Alta Planning & BIT, 2017) or personalizing communication and offerings to different user groups based on preferences (BIT, 2014).

Limitations of the present study

While the large and representative sample is considered a strength of this study, some limitations of our study should be noted. First, to ensure cost-efficient data collection at the required scale, the survey employed pragmatic binary and categorical measures of attribute relevance and stated usage behavior. More detailed retrospective methods (e.g., diary studies) were deemed unsuitable for the sample size, and actual trip data could not be analyzed since Deutschlandticket usage can technically not be tracked. Second, as outlined in the methodology section, the empirical survey and conceptual framework were developed independently and integrated prior to analysis. While this enabled access to high-quality data, it led to an imbalance across EAST categories, with ‘easy’ attributes overrepresented and ‘attractive’ attributes not represented. Consequently, the number of attributes reported per category cannot be interpreted as an indicator of relative importance. Third, since the study aims at providing an exploratory overview of the role of behaviorally aligned attributes, testing for confounding variables is not in scope of the current study. Future research could employ Likert scales capturing psychological constructs (e.g., values, norms, intentions) and objective constraints (e.g., urban vs rural contexts) within frameworks such as the Comprehensive Action Determination Model (Klöckner and Blöbaum, Reference Klöckner and Blöbaum2010) to strengthen explanatory power. Lastly, our study only covers the first 4 months of the Deutschlandticket. Longer or longitudinal studies could investigate temporal dynamics, such as a potential decline in discrepancies between stated importance and stated usage once citizens have sufficient experience with the new ticket. Again, such analysis is hampered by the fact that the actual usage of the ticket cannot be tracked.

Avenues for future research

In addition to the research pathways outlined to address limitations of the current study, further research is needed to validate and quantify the ‘flat-rate bias’ and to investigate underlying effects, which could use existing scales (Lambrecht and Skiera, Reference Lambrecht and Skiera2006; Wirtz et al., Reference Wirtz, Chlond and Vortisch2015). Furthermore, research could explore whether a ‘pay-per-use bias’, a preference for single tickets, exists for non-user groups (Lambrecht and Skiera, Reference Lambrecht and Skiera2006). Based on these proposed studies, bias-busting interventions (Kormos et al., Reference Kormos, Sussman and Rosenberg2021) could be tested. For instance, tailored information could provide transparency regarding public transport costs and potential savings with flat-fare tickets compared to car ownership.

Conclusion

The present study indicates that behaviorally aligned attributes contribute to the success of flat-fare public transport tickets. Based on these findings, policymakers are well advised to actively consider insights from behavioral science when designing public transport tariffs. While not a panacea, such instruments could be an important element in a coordinated policy mix and particularly effective to attract new customers.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2026.10029.

Acknowledgments

The survey was commissioned by the Fraunhofer Institute for Industrial Engineering (IAO) and Fraunhofer Institute for Material Flow and Logistics (IML) and administered via the panel provider Cint. The authors would like to thank Sophia Becker, Maike Gossen and Lucia A. Reisch for helpful comments on this project. MB would like to acknowledge financial support from the Foundation of German Business (sdw). All analyses and conclusions are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author contributions

Michael Bissel: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, visualization, writing – original draft preparation, writing – review & editing. Carolin Dörsam: investigation, data curation, resources, formal analysis, writing – review & editing, funding acquisition. David Agola: investigation, data curation, resources, writing – review & editing, funding acquisition

Ethics statement

The study adhered to national and international ethical guidelines. An NHS Health Research Authority assessment confirmed that ethical approval was not required, as the research involved secondary analysis of an anonymized existing dataset.