1. Introduction

The moving-boundary problem (Crank Reference Crank1984; Pozrikidis Reference Pozrikidis1997; Fokas & Kalimeris Reference Fokas and Kalimeris2017) plays a pivotal role in understanding various natural processes and engineering applications where boundaries between different phases of matter or regions evolve. A prominent example of this is the Stefan problem, the simplest form (Voller, Swenson & Paola Reference Voller, Swenson and Paola2004; Mitchell & Vynnycky Reference Mitchell and Vynnycky2009; Nandi & Sanyasiraju Reference Nandi and Sanyasiraju2020) of which involves a partial differential equation for energy transport and a dynamic boundary. For example, in heat conduction problems, the phase change between solid and liquid phases creates a boundary that moves as the system evolves. The complexity of these problems arises from the need to model both the evolution of the boundary and the physical processes within the domain, such as heat diffusion or mass transfer, which are often nonlinear and coupled with the dynamics of the boundary itself. While this provides a simple framework for modelling phase changes, real-world systems are often more complex, requiring modifications to account for factors such as fluid movement or external disturbances. In many practical cases (Stern Reference Stern1975; Stevens Reference Stevens2005; McPhee Reference McPhee2008), the involved phase-change material does not remain stationary but instead experiences convection due to energy gradients, buoyancy effects or external forces. The phase change in this case is driven not only by the energy diffusion but also by the convective flow within the liquid. This presents often more significant challenges both in mathematical modelling and physical understanding of the system, as it demands coupling of the flow fields with the energy transport mechanisms governed by convection–diffusion-type equations, alongside the evolving boundary. One particular class of such problems arises in the context of dissolution processes (Davies Wykes et al. Reference Wykes, Megan, Huang, Hajjar and Ristroph2018; Ristroph Reference Ristroph2018; Pegler & Davies Wykes Reference Pegler, Wykes and Megan2020; Wells & Worster Reference Wells and Worster2011; Miao, Yuan & Zhao Reference Miao, Yuan and Zhao2020; Nandi & Yedida Reference Nandi and Yedida2023), where a solute material dissolves into a surrounding fluid.

Over the years, convective dissolution phenomena have been studied across various contexts in the literature, focusing on different aspects such as the shape evolution of dissolving materials (Pegler & Davies Wykes Reference Pegler, Wykes and Megan2020, Reference Pegler, Wykes and Megan2021; Huang & Moore Reference Mac Huang and Moore2022), employment of scaling laws (Huang, Moore & Ristroph Reference Huang, Moore and Ristroph2015; Dietrich et al. Reference Dietrich, Wildeman, Visser, Hofhuis, Kooij, Zandvliet and Lohse2016; Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Berhanu, Derr and du Pont Courrech2020), flow regime analysis with their impact on the process (Sullivan, Liu & Ecke Reference Sullivan, Liu and Ecke1996; Huang, Shelley & Stein Reference Huang, Shelley and Stein2021; Nandi & Yedida Reference Nandi and Yedida2023) and so on. Despite their apparent diversity across different systems, the physical mechanisms driving these dissolution processes are governed by common underlying principles. In many cases, the dissolution of a solute into a surrounding fluid yields local variations in solute concentration, which subsequently change the fluid’s density. This density variation is the primary mechanism for the formation of convective flow as the system seeks to restore mass equilibrium. The buoyant forces caused by the density gradients lead to natural convection, which significantly affects the dissolution rate and the overall shape of the dissolving boundary. In many practical situations, in addition to these internal, naturally driven forces, external factors such as temperature gradients, shear forces, pressure gradients or external flow fields can also play a significant role in influencing the convective dissolution process. For instance, temperature gradients (Olivella et al. Reference Olivella, Carrera, Gens and Alonso1996; Naviaux et al. Reference Naviaux, Subhas, Rollins, Dong, Berelson and Adkins2019) or pressure changes (Tasaka et al. Reference Tasaka, Sekiguchi, Urahama, Matsubara, Kiyono and Suzuki1990; Ren et al. Reference Ren, Hao, Li, Wang, Liu and Li2024) can modify the dissolution dynamics by affecting both the fluid’s properties and the solubility of the material. Similarly, rotation of the fluid or the presence of mechanical stirring generates shear forces (Khoury, Mauger & Howard Reference Khoury, Mauger and Howard1988; Wallin & Bjerle Reference Wallin and Bjerle1989; Ashokbhai et al. Reference Ashokbhai, Sanjay, Sah and Kaity2024) within the fluid, which can enhance mixing and disturb the formation of concentration gradients near the dissolving material. However, the combined effect of these factors, along with the internal forces, determines the overall efficiency of the dissolution process.

The process driven by the interplay between internal forces with rotational factors is particularly relevant in various industrial applications such as drug dissolution, mixing processes and solute extraction from materials. Most of the studies found in the existing literature on this area are based on experimental results. For example, one may refer to the study on the dissolution of limestone in a rotating cylinder (Wallin & Bjerle Reference Wallin and Bjerle1989), dissolution of hydrocortisone alcohol and acetate in rotating fluids (Khoury et al. Reference Khoury, Mauger and Howard1988), a rotating cylinder electrode (Gabe Reference Gabe1974), and so on. In many of these studies, the typical set-up consists of a dissolvable solute placed in a rotating vertical cylindrical container filled with solvent. On the other hand, in the current study, though we focus on understanding a similar dissolution process, apart from the solute being in the shape of a circular cylinder, such as a candle or rod, the rotating cylindrical container is horizontal, rather than vertical. A previous study on the dissolution in a similar configuration but without rotation was conducted by Nandi & Yedida (Reference Nandi and Yedida2023). They mainly focused on the dissolution rate and shape evolution under various parameters like fluid–solute volumetric ratio, Stefan number

![]() $(St)$

, solutal Rayleigh number

$(St)$

, solutal Rayleigh number

![]() $(Ra)$

, Schmidt number

$(Ra)$

, Schmidt number

![]() $(Sc)$

, etc. However, this study specifically aims to examine the contribution of rotational forces to the dissolution process while keeping all other involved parameters constant. Our objective is to observe how the rate of dissolution differs with the addition of rotational force, along with the corresponding flow behaviours and shape dynamics of the solute. Additionally, the study attempts to predict dissolution time at various rotation speeds and explores the relationship between the percentage of dissolution and time. It also focuses on providing a rough/estimated idea of shape dynamics by introducing a modified Rayleigh number

$(Sc)$

, etc. However, this study specifically aims to examine the contribution of rotational forces to the dissolution process while keeping all other involved parameters constant. Our objective is to observe how the rate of dissolution differs with the addition of rotational force, along with the corresponding flow behaviours and shape dynamics of the solute. Additionally, the study attempts to predict dissolution time at various rotation speeds and explores the relationship between the percentage of dissolution and time. It also focuses on providing a rough/estimated idea of shape dynamics by introducing a modified Rayleigh number

![]() $(Ra_{\varOmega })$

that accounts for both gravitational and rotational effects. In the process, it also aims to provide a complete numerical framework for predicting the dissolution dynamics in rotating systems, which is lacking in the existing literature.

$(Ra_{\varOmega })$

that accounts for both gravitational and rotational effects. In the process, it also aims to provide a complete numerical framework for predicting the dissolution dynamics in rotating systems, which is lacking in the existing literature.

Mathematically, modelling dissolution (phase-change) systems chosen for the present configuration is fraught with unique challenges due to the dynamic nature of the interface and the additional mechanical rotational factors introduced by the rotation of the cylinder. Traditional numerical techniques often fail to adequately address such complex, time-dependent and multi-dimensional systems. This study adopts a stable and accurate boundary-fitted grid-based method (Nandi & Sanyasiraju Reference Nandi and Sanyasiraju2022), which is capable of solving the coupled nonlinear governing equations while accurately capturing the transient interface without the need for supplementary tools such as level-set, phase field, immersed boundary methods, etc. Here, at each time step of computation, the physical domain is transformed into a fixed rectangular domain using a boundary-fitted transformation. The transformed energy transport and the flow-field equations are then solved on the computational grid using an unconditionally stable alternating direction implicit (ADI) scheme, while the boundary update equations are solved using a total variation diminishing Runge–Kutta method. Before applying this numerical approach to the problem under consideration, it is validated by solving a benchmark problem of natural convective heat transfer in a counter-rotating cylindrical annulus (Abu-Sitta et al. Reference Abu-Sitta, Khanafer, Vafai and Al-Amiri2007) but without phase transition using the same scheme.

The outline of the paper is as follows. Section 2 details the mathematical formulation of the problem, including the governing equations and boundary conditions. Section 3 discusses the numerical methods used for solving the problem, while § 4 presents and analyses the results of our simulations. Finally, in § 5, we conclude by summarising our findings and suggesting potential directions for future research.

2. Mathematical model

Consider the dissolution of a cylindrical solvable substance (solid/solute) in a solvent (fluid) filling an infinitely long horizontal concentric cylinder rotating in the clockwise direction about its axis (see figure 1). As the solid dissolves, the fluid–solid boundary (interface) recedes, dissolved solute mixes with the solvent and forms a solution (solvent + dissolved solute). It is assumed that the solute is sufficiently solid so that it dissolves uniformly in the solvent without fragmenting under the influence of the developed flow. In general, the fragmentation of a dissolving substance depends on several factors, including mechanical stress from high fluid velocities, chemical instability or reactivity in the solvent, solubility limits, thermal effects and so on. Solute dissolution leads to a density gradient in the fluid, leading to a convective flow.

Further, we assume that the cylinder experiences a clockwise rotation relative to the solute at an angular velocity

![]() $\varOmega _0$

about its horizontal axis. Although the rotation of the cylinder enhances the convective flow, the assumptions of the flow remain valid up to a certain rotation speed until the solubility limit is maintained. It is worth mentioning that due to the mechanically induced forced convection resulting from cylinder rotation, the solute dissolution is driven by the combined effects of natural and forced convection.

$\varOmega _0$

about its horizontal axis. Although the rotation of the cylinder enhances the convective flow, the assumptions of the flow remain valid up to a certain rotation speed until the solubility limit is maintained. It is worth mentioning that due to the mechanically induced forced convection resulting from cylinder rotation, the solute dissolution is driven by the combined effects of natural and forced convection.

Assuming that the flow remains invariant along the axis of the cylinder, the problem can be modelled mathematically in two space dimensions. We consider a cross-section of the cylinder perpendicular to its axis such that the liquid region is contained between the cylinder and the interface (see figure 1 b for the initial time and figure 1 c for a later time). We restrict our study to the fluid region, and the boundary concentration of the solute is assumed to be equal to the phase-change concentration at which the solution saturates. Solute dissolution may generate latent heat due to the interactions between the solute and solvent molecules. Depending on the nature of the solute–solvent interactions, it may either absorb or release latent heat. However, the effects of the latent heat generated and heat arising due to mixing during the dissolution are extremely negligible on the flow structure, and hence they are neglected here. Thus, the density of the solution depends solely on the concentration of the dissolved solute.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the problem under consideration. (a) An infinitely long rotating horizontal cylinder filled with an incompressible solvent (blue) in which a solute (yellow) in the shape of a concentric circular cylinder is placed initially (at time

![]() $t = 0$

), and (b) its

$t = 0$

), and (b) its

![]() $xy$

cross-section showing the two-dimensional nature of the problem under investigation in this study. (c) Location and geometry of the solute–solvent interface

$xy$

cross-section showing the two-dimensional nature of the problem under investigation in this study. (c) Location and geometry of the solute–solvent interface

![]() $\varGamma (t)$

at a later time (

$\varGamma (t)$

at a later time (

![]() $t \gg 1$

) along with its initial position,

$t \gg 1$

) along with its initial position,

![]() $\varGamma (0)$

(dashed line), and the cylinder wall,

$\varGamma (0)$

(dashed line), and the cylinder wall,

![]() $\varGamma _w$

.

$\varGamma _w$

.

The fluid region,

![]() $\varSigma _{l}(t)\subset \mathbb{R}^2$

, is bounded by the rigid wall of the cylinder,

$\varSigma _{l}(t)\subset \mathbb{R}^2$

, is bounded by the rigid wall of the cylinder,

![]() $\varGamma _w$

(outer boundary), and the interface,

$\varGamma _w$

(outer boundary), and the interface,

![]() $\varGamma (t)$

(inner boundary). At

$\varGamma (t)$

(inner boundary). At

![]() $t = 0$

, the fluid region corresponds to an annular region (see figure 1

b), and as time progresses, its shape is determined by the evolving interface

$t = 0$

, the fluid region corresponds to an annular region (see figure 1

b), and as time progresses, its shape is determined by the evolving interface

![]() $\varGamma (t)$

(see figure 1

c) governed by the Stefan condition. The liquid is assumed to be incompressible, and the density variation is modelled using the Oberbeck–Boussinesq approximation. The mass balance of the dissolved solute concentration (

$\varGamma (t)$

(see figure 1

c) governed by the Stefan condition. The liquid is assumed to be incompressible, and the density variation is modelled using the Oberbeck–Boussinesq approximation. The mass balance of the dissolved solute concentration (

![]() $c$

) is described in terms of an advection–diffusion equation. Thus, the resulting governing equations read as

$c$

) is described in terms of an advection–diffusion equation. Thus, the resulting governing equations read as

where

![]() $p$

represents the pressure distribution,

$p$

represents the pressure distribution,

![]() $\hat {g}$

denotes the gravitational acceleration,

$\hat {g}$

denotes the gravitational acceleration,

![]() $\rho _0 = \rho (c = 0)$

is the density of the solvent,

$\rho _0 = \rho (c = 0)$

is the density of the solvent,

![]() $\beta _c$

is the solutal mass expansion coefficient,

$\beta _c$

is the solutal mass expansion coefficient,

![]() $c_{\varGamma }$

is the concentration at the interface,

$c_{\varGamma }$

is the concentration at the interface,

![]() $\nu$

is the kinematic viscosity and

$\nu$

is the kinematic viscosity and

![]() $D$

is the mass diffusivity of the solute in the liquid. The last term on the right-hand side of (2.2) indicates the buoyancy force acting against the force of gravity. Here, we consider that gravity acts vertically downward, i.e.

$D$

is the mass diffusivity of the solute in the liquid. The last term on the right-hand side of (2.2) indicates the buoyancy force acting against the force of gravity. Here, we consider that gravity acts vertically downward, i.e.

![]() $\hat {g} = -g\hat {j}$

, where

$\hat {g} = -g\hat {j}$

, where

![]() $\hat {j}$

denotes the unit vector in the

$\hat {j}$

denotes the unit vector in the

![]() $y$

direction.

$y$

direction.

2.1. Initial and boundary conditions

The mathematical description of the problem is concluded by prescribing initial and boundary conditions. Initially, the fluid region is filled with quiescent solvent, mathematically

Fluid velocity at the boundaries satisfies

where

![]() $V_{\!x}$

and

$V_{\!x}$

and

![]() $V_{\!y}$

are the horizontal and vertical components of the interface velocity, respectively, and

$V_{\!y}$

are the horizontal and vertical components of the interface velocity, respectively, and

![]() $\hat {n}^\varGamma = (n_x^\varGamma , n_y^\varGamma )$

is the unit normal to the interface into the fluid region. Although the fluid velocity at the interface is assumed to be the same as the interface velocity, one can also use

$\hat {n}^\varGamma = (n_x^\varGamma , n_y^\varGamma )$

is the unit normal to the interface into the fluid region. Although the fluid velocity at the interface is assumed to be the same as the interface velocity, one can also use

![]() $V = 0$

(Huang et al. Reference Huang, Shelley and Stein2021). This assumption is relevant because the interface velocity is typically very small (

$V = 0$

(Huang et al. Reference Huang, Shelley and Stein2021). This assumption is relevant because the interface velocity is typically very small (

![]() ${\sim} \boldsymbol{O}(10^{-5})$

) in dissolution problems. On the other hand, the fluid velocity at the wall

${\sim} \boldsymbol{O}(10^{-5})$

) in dissolution problems. On the other hand, the fluid velocity at the wall

![]() $\varGamma _w$

is specified based on a fixed clockwise rotation speed

$\varGamma _w$

is specified based on a fixed clockwise rotation speed

![]() $\varOmega _0 (\geqslant 0)$

. This indicates that the wall is treated as rotating with a constant angular velocity, without any acceleration or oscillation.

$\varOmega _0 (\geqslant 0)$

. This indicates that the wall is treated as rotating with a constant angular velocity, without any acceleration or oscillation.

At the interface

![]() $\varGamma (t)$

, concentration equals the saturation concentration (

$\varGamma (t)$

, concentration equals the saturation concentration (

![]() $c_{\textit{sat}}$

) of the solution:

$c_{\textit{sat}}$

) of the solution:

As the solute dissolves, the interface recedes as a necessary consequence of mass conservation, described by the flux balance (Wells & Worster Reference Wells and Worster2011; Pegler & Davies Wykes Reference Pegler, Wykes and Megan2021, and references therein):

where

![]() $\rho _s$

is the density of the solid,

$\rho _s$

is the density of the solid,

![]() $c_s$

is the concentration of the undissolved solute and

$c_s$

is the concentration of the undissolved solute and

![]() $V$

is the normal velocity of the interface. The condition (2.7) indicates that the solute dissolution rate/speed depends on the concentration flux at the interface as well as the mass diffusivity of the solute in the solvent. Interestingly, in nature, the mass diffusivity of most solute materials is relatively low. As a result, we can expect the dissolution process to be slower than other phase-change processes, such as melting or solidification. However, the current investigation does not focus on any specific solute or solvent. At the outer boundary

$V$

is the normal velocity of the interface. The condition (2.7) indicates that the solute dissolution rate/speed depends on the concentration flux at the interface as well as the mass diffusivity of the solute in the solvent. Interestingly, in nature, the mass diffusivity of most solute materials is relatively low. As a result, we can expect the dissolution process to be slower than other phase-change processes, such as melting or solidification. However, the current investigation does not focus on any specific solute or solvent. At the outer boundary

![]() $\varGamma _w$

, we assume a Neumann condition:

$\varGamma _w$

, we assume a Neumann condition:

representing no diffusive flux, wherein

![]() $\boldsymbol{n}^w$

represents a unit normal out of the fluid region.

$\boldsymbol{n}^w$

represents a unit normal out of the fluid region.

2.2. Non-dimensionalisation

Introducing the annular gap width

![]() $L$

as the characteristic length scale, we define the characteristic velocity as

$L$

as the characteristic length scale, we define the characteristic velocity as

which is analogous to the free-fall velocity commonly used in natural convection, obtained by balancing the buoyancy and convective terms appearing in the momentum equation. Using this velocity scale, we render the non-dimensional variables as

The corresponding dimensionless equations read (after dropping the prime symbols)

Equations (2.11)–(2.13) are associated with the initial conditions

boundary conditions

and the Stefan condition

A close look into (2.11)–(2.17) yields that the convective dissolution problem can be studied in terms of four dimensionless parameters: Péclet number (

![]() $\textit{Pe}$

), Reynolds number (

$\textit{Pe}$

), Reynolds number (

![]() $\textit{Re}$

) (or, two derived parameters – solutal Rayleigh number (

$\textit{Re}$

) (or, two derived parameters – solutal Rayleigh number (

![]() $Ra = \textit{Re} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\textit{Pe}$

) and Schmidt number (

$Ra = \textit{Re} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\textit{Pe}$

) and Schmidt number (

![]() $Sc = \textit{Pe}/\textit{Re}$

)); Stefan number (

$Sc = \textit{Pe}/\textit{Re}$

)); Stefan number (

![]() $St$

); and

$St$

); and

![]() $\varOmega$

. These parameters are defined as

$\varOmega$

. These parameters are defined as

where

![]() $\Delta c_s = c_s - c_\varGamma$

.

$\Delta c_s = c_s - c_\varGamma$

.

2.3. Stream function–vorticity formulation

The stream function–vorticity formulation of the Navier–Stokes equations in a two-dimensional domain facilitates a more comprehensive and intuitive understanding of flow mechanisms than the conventional representation using primitive variables (

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}, p$

). In a two-dimensional Cartesian framework, the relationships between the stream function

$\boldsymbol{u}, p$

). In a two-dimensional Cartesian framework, the relationships between the stream function

![]() $(\psi )$

and vorticity

$(\psi )$

and vorticity

![]() $(\omega )$

are defined as follows:

$(\omega )$

are defined as follows:

where

![]() $ u,v$

denote the velocity components of the fluid in

$ u,v$

denote the velocity components of the fluid in

![]() $x,y$

directions, respectively. Using these relations, the governing flow system becomes

$x,y$

directions, respectively. Using these relations, the governing flow system becomes

The corresponding boundary conditions for

![]() $\psi$

are

$\psi$

are

To complete the system, boundary conditions for the vorticity

![]() $\omega$

are required to be computed from (2.20) utilising conditions (2.22) and (2.23). These are discussed/specified later.

$\omega$

are required to be computed from (2.20) utilising conditions (2.22) and (2.23). These are discussed/specified later.

2.4. Gibbs–Thomson effect

The Stefan condition (2.17) indicates that the interface velocity can be determined solely from the parameter ratio

![]() $St/\textit{Pe}$

and the concentration flux into the fluid region at the interface. Notably, this movement/velocity may also be influenced by the shape of the interface surface. In convex regions, where the local curvature exceeds the mean curvature, the interface moves more rapidly, enhancing the dissolution process. Conversely, in concave regions, the movement is steadier, resulting in a slower dissolution process. Although the initial circular interface of this model is smooth, it may develop irregularities in areas of both low and high curvature during dissolution. In such instances, it is necessary to equilibrate the interface motion between the concave and convex regions. The Gibbs–Thomson effect effectively addresses this requirement by establishing equilibrium in mass exchange between the solid and fluid regions due to interface effects. In this context, the interface velocity is adjusted as (Perez Reference Perez2005; Moore et al. Reference Moore, Ristroph, Childress, Zhang and Shelley2013; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Shelley and Stein2021)

$St/\textit{Pe}$

and the concentration flux into the fluid region at the interface. Notably, this movement/velocity may also be influenced by the shape of the interface surface. In convex regions, where the local curvature exceeds the mean curvature, the interface moves more rapidly, enhancing the dissolution process. Conversely, in concave regions, the movement is steadier, resulting in a slower dissolution process. Although the initial circular interface of this model is smooth, it may develop irregularities in areas of both low and high curvature during dissolution. In such instances, it is necessary to equilibrate the interface motion between the concave and convex regions. The Gibbs–Thomson effect effectively addresses this requirement by establishing equilibrium in mass exchange between the solid and fluid regions due to interface effects. In this context, the interface velocity is adjusted as (Perez Reference Perez2005; Moore et al. Reference Moore, Ristroph, Childress, Zhang and Shelley2013; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Shelley and Stein2021)

where

![]() $\epsilon$

is a smoothing term in the interface velocity to enhance numerical stability without affecting the physical dissolution process (Moore et al. Reference Moore, Ristroph, Childress, Zhang and Shelley2013; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Shelley and Stein2021). Here,

$\epsilon$

is a smoothing term in the interface velocity to enhance numerical stability without affecting the physical dissolution process (Moore et al. Reference Moore, Ristroph, Childress, Zhang and Shelley2013; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Shelley and Stein2021). Here,

![]() $\kappa$

and

$\kappa$

and

![]() $S$

represent the local curvature and total arc length of the interface, respectively. When the interface is circular, the local curvature

$S$

represent the local curvature and total arc length of the interface, respectively. When the interface is circular, the local curvature

![]() $\kappa$

is equivalent to the mean curvature given by

$\kappa$

is equivalent to the mean curvature given by

![]() $2\pi /S$

. As a result, no adjustment to the interface velocity is required for a steadily advancing circular interface.

$2\pi /S$

. As a result, no adjustment to the interface velocity is required for a steadily advancing circular interface.

3. Numerical methods

3.1. Transformed model in computational domain

The initial annular domain of the problem evolves due to the dynamic characteristics of the interface, which may lead to complex shapes. Therefore, in order to solve the problem on a uniform Cartesian grid numerically, the physical domain is transformed at every time step into a fixed unit square

![]() $([0,1]\times [0,1])$

using a boundary-fitted transformation (see figure 2). This transformation is implemented so that the physical boundaries of the problem align with the boundary curves of the

$([0,1]\times [0,1])$

using a boundary-fitted transformation (see figure 2). This transformation is implemented so that the physical boundaries of the problem align with the boundary curves of the

![]() $(\xi ,\eta )$

coordinates. In the present scenario, we map the inner boundary

$(\xi ,\eta )$

coordinates. In the present scenario, we map the inner boundary

![]() $\varGamma (t)$

(the interface) to the line

$\varGamma (t)$

(the interface) to the line

![]() $\xi = 0$

and the outer rotating wall

$\xi = 0$

and the outer rotating wall

![]() $\varGamma _w$

to the line

$\varGamma _w$

to the line

![]() $\xi = 1$

. The other two lines,

$\xi = 1$

. The other two lines,

![]() $\eta = 0$

and

$\eta = 0$

and

![]() $\eta = 1$

, act as artificial boundaries, allowing the computational domain to be defined without resorting to the use of physical boundaries.

$\eta = 1$

, act as artificial boundaries, allowing the computational domain to be defined without resorting to the use of physical boundaries.

Figure 2. Layout of a typical

![]() $10\times 24$

grid in the (a) physical

$10\times 24$

grid in the (a) physical

![]() $(x,y)$

domain and (b) computational

$(x,y)$

domain and (b) computational

![]() $(\xi ,\eta )$

domain.

$(\xi ,\eta )$

domain.

The corresponding Cartesian grid in the

![]() $(\xi ,\eta )$

domain is generated by solving the following equations (see Thompson, Thames & Mastin (Reference Thompson, Thames and Mastin1974) and Nandi & Sanyasiraju (Reference Nandi and Sanyasiraju2021) for further details):

$(\xi ,\eta )$

domain is generated by solving the following equations (see Thompson, Thames & Mastin (Reference Thompson, Thames and Mastin1974) and Nandi & Sanyasiraju (Reference Nandi and Sanyasiraju2021) for further details):

with

Here, the functions

![]() $P$

and

$P$

and

![]() $Q$

are used to control the spacing between grid lines. To avoid the interpolation at every time step of calculations, time derivative is calculated in the

$Q$

are used to control the spacing between grid lines. To avoid the interpolation at every time step of calculations, time derivative is calculated in the

![]() $(\xi , \eta )$

domain using the following relation:

$(\xi , \eta )$

domain using the following relation:

\begin{align} \left (\dfrac {\partial g}{\partial t}\right )_{x, y} & = \dfrac {\partial (x, y, g)}{\partial (\xi , \eta , t)}\big/ \dfrac {\partial (x, y, t)}{\partial (\xi , \eta , t)} \nonumber \\ & = \left (\dfrac {\partial g}{\partial t}\right )_{\xi , \eta } - \dfrac {(g_{\xi }y_{\eta } - g_{\eta }y_{\xi })}{J} \left (\dfrac {{\rm d}x}{{\rm d}t}\right )_{\xi , \eta } + \dfrac {(g_{\xi }x_{\eta } - g_{\eta }x_{\xi })}{J} \left (\dfrac {{\rm d}y}{{\rm d}t}\right )_{\xi , \eta }\!, \end{align}

\begin{align} \left (\dfrac {\partial g}{\partial t}\right )_{x, y} & = \dfrac {\partial (x, y, g)}{\partial (\xi , \eta , t)}\big/ \dfrac {\partial (x, y, t)}{\partial (\xi , \eta , t)} \nonumber \\ & = \left (\dfrac {\partial g}{\partial t}\right )_{\xi , \eta } - \dfrac {(g_{\xi }y_{\eta } - g_{\eta }y_{\xi })}{J} \left (\dfrac {{\rm d}x}{{\rm d}t}\right )_{\xi , \eta } + \dfrac {(g_{\xi }x_{\eta } - g_{\eta }x_{\xi })}{J} \left (\dfrac {{\rm d}y}{{\rm d}t}\right )_{\xi , \eta }\!, \end{align}

where

![]() $g \in \{ c, \omega \}$

.

$g \in \{ c, \omega \}$

.

Using (3.4), the governing equation for the concentration field

![]() $c$

in the computational plane reads as

$c$

in the computational plane reads as

where

\begin{align} & A = \dfrac {\alpha }{J^{2}\textit{Pe}},\quad B = - \dfrac {2 \beta }{J^{2}\textit{Pe}},\quad C = \dfrac {\gamma }{J^{2}\textit{Pe}}, \nonumber\\ & D = \dfrac {P}{\textit{Pe}} - \dfrac {1}{J}\! \left (x_{\eta }\frac {{\rm d}y}{{\rm d}t} - y_{\eta } \frac {{\rm d}x}{{\rm d}t}\right ), \quad E = \frac {Q}{\textit{Pe}} - \frac {1}{J}\! \left ( y_{\xi } \frac {{\rm d}x}{{\rm d}t} - x_{\xi } \frac {{\rm d}y}{{\rm d}t}\right )\!. \end{align}

\begin{align} & A = \dfrac {\alpha }{J^{2}\textit{Pe}},\quad B = - \dfrac {2 \beta }{J^{2}\textit{Pe}},\quad C = \dfrac {\gamma }{J^{2}\textit{Pe}}, \nonumber\\ & D = \dfrac {P}{\textit{Pe}} - \dfrac {1}{J}\! \left (x_{\eta }\frac {{\rm d}y}{{\rm d}t} - y_{\eta } \frac {{\rm d}x}{{\rm d}t}\right ), \quad E = \frac {Q}{\textit{Pe}} - \frac {1}{J}\! \left ( y_{\xi } \frac {{\rm d}x}{{\rm d}t} - x_{\xi } \frac {{\rm d}y}{{\rm d}t}\right )\!. \end{align}

Similarly, the equation for the vorticity field can be expressed as

where

\begin{align} & A_1 = \dfrac {\alpha }{J^{2}\textit{Re}},\quad B_1 = - \dfrac {2 \beta }{J^{2}\textit{Re}},\quad C_1 = \dfrac {\gamma }{J^{2}Re}, \quad R = - \dfrac {1}{J} ( c_\xi y_\eta - c_\eta y_\xi ), \nonumber\\ & D_1 = \dfrac {P}{\textit{Re}} - \frac {1}{J}\! \left ( x_{\eta } \frac {{\rm d}y}{{\rm d}t} - y_{\eta } \frac {{\rm d}x}{{\rm d}t}\right ), \quad E_1 = \dfrac {Q}{\textit{Re}} - \frac {1}{J}\! \left ( y_{\xi } \frac {{\rm d}x}{{\rm d}t} - x_{\xi } \frac {{\rm d}y}{{\rm d}t} \right )\!. \end{align}

\begin{align} & A_1 = \dfrac {\alpha }{J^{2}\textit{Re}},\quad B_1 = - \dfrac {2 \beta }{J^{2}\textit{Re}},\quad C_1 = \dfrac {\gamma }{J^{2}Re}, \quad R = - \dfrac {1}{J} ( c_\xi y_\eta - c_\eta y_\xi ), \nonumber\\ & D_1 = \dfrac {P}{\textit{Re}} - \frac {1}{J}\! \left ( x_{\eta } \frac {{\rm d}y}{{\rm d}t} - y_{\eta } \frac {{\rm d}x}{{\rm d}t}\right ), \quad E_1 = \dfrac {Q}{\textit{Re}} - \frac {1}{J}\! \left ( y_{\xi } \frac {{\rm d}x}{{\rm d}t} - x_{\xi } \frac {{\rm d}y}{{\rm d}t} \right )\!. \end{align}

Here, the contravariant fluid velocity components

![]() $u^{\xi }$

and

$u^{\xi }$

and

![]() $u^{\eta }$

in the

$u^{\eta }$

in the

![]() $\xi$

and

$\xi$

and

![]() $\eta$

directions are expressed as follows:

$\eta$

directions are expressed as follows:

which satisfy the continuity equation (2.11). Therefore, in computations, techniques such as upwinding or downwinding can be applied using these contravariant components instead of Cartesian ones. This approach facilitates an accurate numerical representation of fluid flow across different coordinate systems. The stream function and the interface normal velocity in the

![]() $\xi \eta$

plane are described by

$\xi \eta$

plane are described by

At the artificial boundaries

![]() $\eta = 0$

and

$\eta = 0$

and

![]() $\eta = 1$

, the flow variables are periodic. On the other hand, at the other boundaries (

$\eta = 1$

, the flow variables are periodic. On the other hand, at the other boundaries (

![]() $\xi = 0, 1$

), concentration

$\xi = 0, 1$

), concentration

![]() $c$

and stream function

$c$

and stream function

![]() $\psi$

are computed using (2.15), (2.22) and (2.23). Finally, the boundary conditions for

$\psi$

are computed using (2.15), (2.22) and (2.23). Finally, the boundary conditions for

![]() $\omega$

at these boundaries are derived from the conditions for

$\omega$

at these boundaries are derived from the conditions for

![]() $\psi$

and (3.10). For example, at the boundary

$\psi$

and (3.10). For example, at the boundary

![]() $\xi = 1$

, (2.23) yields

$\xi = 1$

, (2.23) yields

This leads to the equation for

![]() $\omega$

as follows:

$\omega$

as follows:

A similar approach can be used to obtain the condition for

![]() $\omega$

at

$\omega$

at

![]() $\xi = 0$

. It is important to note that the derivatives involved in the

$\xi = 0$

. It is important to note that the derivatives involved in the

![]() $\omega$

boundary condition are computed using a five-point ghost cell technique to incorporate the specified lower-order non-zero derivative condition efficiently.

$\omega$

boundary condition are computed using a five-point ghost cell technique to incorporate the specified lower-order non-zero derivative condition efficiently.

3.2. Numerical scheme implementation for flow and concentration

While implementing the numerical scheme, the spatial derivatives are discretised using standard second-order central difference approximations, while the convection terms are approximated using a third-order QUICK scheme (Johnson & MacKinnon Reference Johnson and MacKinnon1992; Leonard Reference Leonard1995), as described below:

where

To compute the stream function

![]() $\psi$

, Poisson’s equation (3.10) is discretised with the boundary condition

$\psi$

, Poisson’s equation (3.10) is discretised with the boundary condition

![]() $\psi = 0$

at

$\psi = 0$

at

![]() $\xi = 0, 1$

. The resulting system of algebraic equations is solved using the bi-conjugate gradient-stabilised method with incomplete LU factorisation as a preconditioner, up to a convergence tolerance of

$\xi = 0, 1$

. The resulting system of algebraic equations is solved using the bi-conjugate gradient-stabilised method with incomplete LU factorisation as a preconditioner, up to a convergence tolerance of

![]() $10^{-10}$

of the residual vector. On the other hand, for the concentration

$10^{-10}$

of the residual vector. On the other hand, for the concentration

![]() $(c)$

and vorticity

$(c)$

and vorticity

![]() $(\omega )$

fields, the advection–diffusion equations (3.5) and (3.7) are split in the time direction using the ADI scheme (In’t Hout & Welfert Reference In’t Hout and Welfert2009):

$(\omega )$

fields, the advection–diffusion equations (3.5) and (3.7) are split in the time direction using the ADI scheme (In’t Hout & Welfert Reference In’t Hout and Welfert2009):

where

![]() $f$

is defined as the sum of three functions:

$f$

is defined as the sum of three functions:

![]() $f_1$

, which consists of derivatives in the

$f_1$

, which consists of derivatives in the

![]() $\xi$

direction;

$\xi$

direction;

![]() $f_2$

, which involves derivatives in the

$f_2$

, which involves derivatives in the

![]() $\eta$

direction; and

$\eta$

direction; and

![]() $f_{12}$

, which includes mixed derivatives and additional terms. The constant parameters

$f_{12}$

, which includes mixed derivatives and additional terms. The constant parameters

![]() $\lambda$

and

$\lambda$

and

![]() $\zeta$

determining the stability of the ADI scheme are chosen as

$\zeta$

determining the stability of the ADI scheme are chosen as

![]() $\lambda \geqslant {1}/{2} + {\sqrt {3}}/{2}$

and

$\lambda \geqslant {1}/{2} + {\sqrt {3}}/{2}$

and

![]() $\zeta = {1}/{2}$

, which are in accordance with the stability analysis (In’t Hout & Welfert Reference In’t Hout and Welfert2009; Nandi & Sanyasiraju Reference Nandi and Sanyasiraju2021).

$\zeta = {1}/{2}$

, which are in accordance with the stability analysis (In’t Hout & Welfert Reference In’t Hout and Welfert2009; Nandi & Sanyasiraju Reference Nandi and Sanyasiraju2021).

The ADI splitting (3.18) involves six intermediate steps for computing the required variables for the next time step, comprising two explicit and four implicit steps. The internal variables

![]() $Y^{(0)}$

and

$Y^{(0)}$

and

![]() $Y^{(3)}$

can be obtained directly from the first and fourth explicit steps, respectively. The other variables

$Y^{(3)}$

can be obtained directly from the first and fourth explicit steps, respectively. The other variables

![]() $Y^{(1)},\ Y^{(2)},\ Y^{(4)}$

and

$Y^{(1)},\ Y^{(2)},\ Y^{(4)}$

and

![]() $Y^{(5)}$

are computed by solving the following four tri-diagonal systems:

$Y^{(5)}$

are computed by solving the following four tri-diagonal systems:

which are deduced from the remaining four implicit steps. Here,

![]() $S_\xi$

and

$S_\xi$

and

![]() $S_\eta$

are two tri-diagonal matrices derived from discretised equations involving functions

$S_\eta$

are two tri-diagonal matrices derived from discretised equations involving functions

![]() $f_{1}(c)$

and

$f_{1}(c)$

and

![]() $f_{2}(c)$

. The column vectors

$f_{2}(c)$

. The column vectors

![]() $B_{l}$

(where

$B_{l}$

(where

![]() $l = 1, \ldots , 4$

) appearing in (3.19a

–

d

) represent the boundary conditions. The boundary conditions for the variables at the intermediate time steps are treated the same as those at the working time steps.

$l = 1, \ldots , 4$

) appearing in (3.19a

–

d

) represent the boundary conditions. The boundary conditions for the variables at the intermediate time steps are treated the same as those at the working time steps.

It is worth noting that although there are four tri-diagonal systems, two distinct tri-diagonal matrices are sufficient to handle the computations for the required variables at a particular time step. The ADI scheme is preferred over other implicit or explicit methods, such as the Crank–Nicolson and total variation diminishing Runge–Kutta schemes, for solving the convection–diffusion equation for vorticity and concentration owing to the former’s computational economy and unconditional stability.

3.3. Interface tracking

Recall from § 3.1 that

![]() $\xi = 0$

corresponds to the interface. Therefore, the unit normal at the interface can be expressed as

$\xi = 0$

corresponds to the interface. Therefore, the unit normal at the interface can be expressed as

![]() $\displaystyle \boldsymbol{n}^\varGamma = ( {y_\eta }/{\sqrt {\alpha }}, - {x_\eta }/{\sqrt {\alpha }} )$

. Thus, given the normal velocity

$\displaystyle \boldsymbol{n}^\varGamma = ( {y_\eta }/{\sqrt {\alpha }}, - {x_\eta }/{\sqrt {\alpha }} )$

. Thus, given the normal velocity

![]() $V$

from (3.11), the interface in the

$V$

from (3.11), the interface in the

![]() $xy$

plane evolves according to

$xy$

plane evolves according to

which can be expressed in a compact form:

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{X} = (x, y)^\top$

and

$\boldsymbol{X} = (x, y)^\top$

and

![]() $\displaystyle \boldsymbol{g} = ( V\! y_\eta /\sqrt {\alpha }, -V\! x_\eta /\sqrt {\alpha } )^\top$

. Equations (3.21) are solved using the third-order total variation diminishing Runge–Kutta scheme:

$\displaystyle \boldsymbol{g} = ( V\! y_\eta /\sqrt {\alpha }, -V\! x_\eta /\sqrt {\alpha } )^\top$

. Equations (3.21) are solved using the third-order total variation diminishing Runge–Kutta scheme:

Here, we have used the total variation diminishing Runge–Kutta method instead of the previously used ADI scheme as the ordinary differential equation system (3.20) involves only unidirectional derivative terms along the

![]() $\eta$

direction. However, it is worth noting that a first-order explicit scheme can also be used for solving these boundary update equations rather than higher-order methods, as its effects on the accuracy of the numerical solutions are negligible (Udaykumar, Mittal & Shyy Reference Udaykumar, Mittal and Shyy1999).

$\eta$

direction. However, it is worth noting that a first-order explicit scheme can also be used for solving these boundary update equations rather than higher-order methods, as its effects on the accuracy of the numerical solutions are negligible (Udaykumar, Mittal & Shyy Reference Udaykumar, Mittal and Shyy1999).

3.4. Overview of computational framework

Numerical simulations at a given time step consist of several key steps starting with grid generation using (3.1)–(3.2). Next, the stream function

![]() $\psi$

is calculated from (3.10) based on the known values of vorticity

$\psi$

is calculated from (3.10) based on the known values of vorticity

![]() $\omega$

. Following this, the fluid velocity components

$\omega$

. Following this, the fluid velocity components

![]() $u^{\xi }$

and

$u^{\xi }$

and

![]() $u^{\eta }$

are derived from (3.9) using the stream function. The boundary conditions for

$u^{\eta }$

are derived from (3.9) using the stream function. The boundary conditions for

![]() $\omega$

are then set according to (3.14). Afterward, the concentration

$\omega$

are then set according to (3.14). Afterward, the concentration

![]() $c$

and vorticity

$c$

and vorticity

![]() $\omega$

are solved separately using the ADI scheme outlined in (3.18). Once these values are obtained, the moving interface is updated using (3.20) with the computed concentration field

$\omega$

are solved separately using the ADI scheme outlined in (3.18). Once these values are obtained, the moving interface is updated using (3.20) with the computed concentration field

![]() $c$

, and the grid is regenerated to reflect the new interface location. This cycle of computation is repeated until convergence is achieved. The numerical solution is assumed to converge when the infinity norm of the absolute errors of the variables

$c$

, and the grid is regenerated to reflect the new interface location. This cycle of computation is repeated until convergence is achieved. The numerical solution is assumed to converge when the infinity norm of the absolute errors of the variables

![]() $\omega , c, x^\varGamma\!, y^\varGamma$

satisfies the specified tolerance of

$\omega , c, x^\varGamma\!, y^\varGamma$

satisfies the specified tolerance of

![]() $10^{-8}$

. Once the process converges, the flow field, concentration field and interface are all stored at the current time step.

$10^{-8}$

. Once the process converges, the flow field, concentration field and interface are all stored at the current time step.

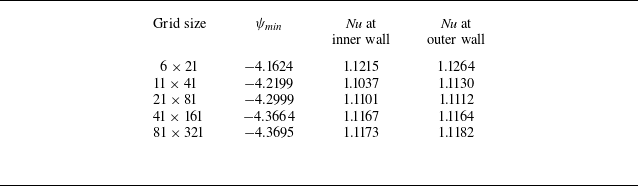

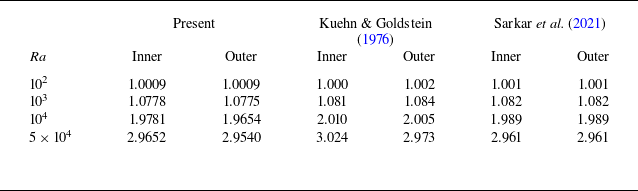

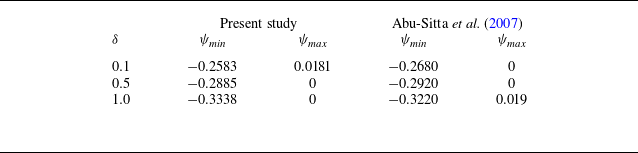

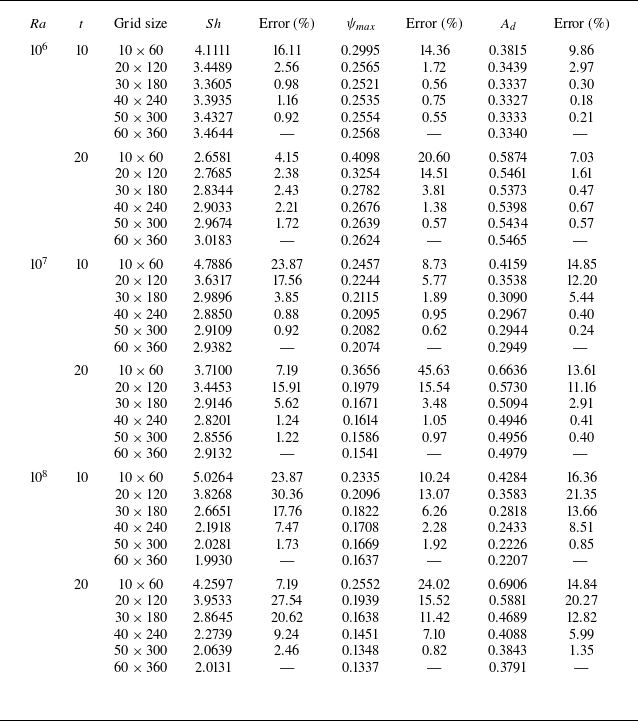

The code validation and grid independence studies for our computations are presented in Appendices A and B, respectively. The CPU time taken to complete one cycle of computation within the convergence loop is approximately 0.6 s for

![]() $50 \times 300$

spatial grid points using MATLAB 2022b in an Intel Xeon(R) Gold 6326 processor with a clock speed of 2.90 GHz and 64 GB of RAM.

$50 \times 300$

spatial grid points using MATLAB 2022b in an Intel Xeon(R) Gold 6326 processor with a clock speed of 2.90 GHz and 64 GB of RAM.

4. Dissolution and mixing

Our primary objective is to study the combined effects of rotation and convection on dissolution and mixing. Throughout this paper, we fix

![]() $St/\textit{Pe} = 3 \times 10^{-3}$

,

$St/\textit{Pe} = 3 \times 10^{-3}$

,

![]() $Sc = 1$

,

$Sc = 1$

,

![]() $\epsilon = 5 \times 10^{-4}$

,

$\epsilon = 5 \times 10^{-4}$

,

![]() $r_i/L = 1$

and

$r_i/L = 1$

and

![]() $r_o/L = 2$

. Thus, effects of buoyancy force (

$r_o/L = 2$

. Thus, effects of buoyancy force (

![]() $Ra$

) and rotation (

$Ra$

) and rotation (

![]() $\varOmega$

) are studied by varying

$\varOmega$

) are studied by varying

![]() $Ra \in [10^5, 10^8]$

and

$Ra \in [10^5, 10^8]$

and

![]() $\varOmega \in [0, 2.5]$

.

$\varOmega \in [0, 2.5]$

.

4.1. Qualitative impacts of rotation and buoyancy on flow and solute dissolution

In this section, we discuss the spatio-temporal dynamics of the dissolved solute concentration and the flow field for different values of

![]() $Ra$

and

$Ra$

and

![]() $\varOmega$

. Figure 3 depicts concentration distribution overlaid by streamlines at four instances corresponding to

$\varOmega$

. Figure 3 depicts concentration distribution overlaid by streamlines at four instances corresponding to

![]() $A_d(t) = 10\,\%,\ 30\,\%,\ 60\,\% \text{ and } 90\,\%$

(where

$A_d(t) = 10\,\%,\ 30\,\%,\ 60\,\% \text{ and } 90\,\%$

(where

![]() $A_d$

corresponds to the dissolved area, defined in (B3)) for

$A_d$

corresponds to the dissolved area, defined in (B3)) for

![]() $Ra = 10^5$

and

$Ra = 10^5$

and

![]() $\varOmega = 0$

to 2 with an increment of 0.5. At the early stages (

$\varOmega = 0$

to 2 with an increment of 0.5. At the early stages (

![]() $A_d(t)$

approximately up to 10 %), irrespective of the rotation speed considered here, dissolution and hence the phase-change process are driven by diffusion only (see the first column of figure 3). Thus, the dissolved solute is localised near the interface, and its concentration reduces as we move away from the interface and eventually decays to zero near the wall. However, rotation breaks the left–right symmetry about the vertical axis

$A_d(t)$

approximately up to 10 %), irrespective of the rotation speed considered here, dissolution and hence the phase-change process are driven by diffusion only (see the first column of figure 3). Thus, the dissolved solute is localised near the interface, and its concentration reduces as we move away from the interface and eventually decays to zero near the wall. However, rotation breaks the left–right symmetry about the vertical axis

![]() $x = 0$

, as evident from the first column of figure 3.

$x = 0$

, as evident from the first column of figure 3.

Figure 3. Streamlines (white contours) overlaying the concentration contours of the dissolved solute at

![]() $A_d(t) = 10\,\%$

,

$A_d(t) = 10\,\%$

,

![]() $30\,\%$

,

$30\,\%$

,

![]() $60\,\%$

and

$60\,\%$

and

![]() $90\,\%$

(left to right) for

$90\,\%$

(left to right) for

![]() $Ra = 10^5$

and

$Ra = 10^5$

and

![]() $\varOmega =$

0–2 with an increment of 0.5 (top to bottom). The corresponding colour map illustrates the concentration variations in the domain at these instances.

$\varOmega =$

0–2 with an increment of 0.5 (top to bottom). The corresponding colour map illustrates the concentration variations in the domain at these instances.

In the absence of rotation, the primary vortices, which are observed initially on either side of the solute along the horizontal central line, gradually move towards the bottom of the solute over time and remain there until the dissolution process is complete. On the other hand, with a rotation speed of

![]() $0.5$

, a primary vortex forms on the right-hand side of the solute’s surface and eventually settles there even when dissolution reaches the

$0.5$

, a primary vortex forms on the right-hand side of the solute’s surface and eventually settles there even when dissolution reaches the

![]() $90\,\%$

stage. However, at rotation speeds of

$90\,\%$

stage. However, at rotation speeds of

![]() $1,\;1.5$

and

$1,\;1.5$

and

![]() $2$

, this vortex ceases to exist after certain stages of dissolution.

$2$

, this vortex ceases to exist after certain stages of dissolution.

Figure 3 also shows that, during dissolution with no rotation, the interplay between diffusion and buoyancy-driven convection aids in developing a laminar velocity boundary layer near the interface except at the topmost part. Rotation induces an additional laminar boundary layer near the cylinder wall. The boundary layer near the interface forms due to the combined effects of buoyancy and centripetal forces. At low rotational speeds, this layer is accompanied by a primary vortex to the right of the interface. As the rotation speed increases, the vortex is pushed away from the interface and eventually disappears. As the cylinder rotates, the fluid in immediate contact with the wall is dragged along, causing the fluid at the surface to move faster than the fluid away from the surface, which leads to the development of an additional boundary layer. An increasing rotation speed induces more shear and larger velocity gradients near the wall, affecting the nature of the boundary-layer thickness.

Figure 4. Streamlines (white contours) overlaying the concentration contours of the dissolved solute at

![]() $A_d(t) = 10\,\%$

,

$A_d(t) = 10\,\%$

,

![]() $30\,\%$

,

$30\,\%$

,

![]() $60\,\%$

and

$60\,\%$

and

![]() $90\,\%$

(left to right) for

$90\,\%$

(left to right) for

![]() $\varOmega =$

1 and

$\varOmega =$

1 and

![]() $Ra = 10^5$

,

$Ra = 10^5$

,

![]() $10^6$

and

$10^6$

and

![]() $10^7$

(top to bottom). The corresponding colour map illustrates the concentration variations in the domain at these instances.

$10^7$

(top to bottom). The corresponding colour map illustrates the concentration variations in the domain at these instances.

Another important observation is that the flow patterns at rotation speeds greater than

![]() $1$

begin to resemble concentric circular layers around both the solute and the cylindrical wall after a certain amount of dissolution. As the rotation speed increases, the gap between these layers becomes smaller. The flow also loses its closed trajectories and tends to become more uniform and structured.

$1$

begin to resemble concentric circular layers around both the solute and the cylindrical wall after a certain amount of dissolution. As the rotation speed increases, the gap between these layers becomes smaller. The flow also loses its closed trajectories and tends to become more uniform and structured.

A similar analysis of the flow regimes is performed by varying the Rayleigh number (

![]() $Ra$

) while keeping the rotation speed fixed at

$Ra$

) while keeping the rotation speed fixed at

![]() $\varOmega = 1$

, which corresponds to the case when the rotation-induced laminar velocity of the cylinder is the same as that of the buoyancy-induced characteristic velocity. Figure 4 depicts that the flow varies significantly as the Rayleigh number increases. For

$\varOmega = 1$

, which corresponds to the case when the rotation-induced laminar velocity of the cylinder is the same as that of the buoyancy-induced characteristic velocity. Figure 4 depicts that the flow varies significantly as the Rayleigh number increases. For

![]() $Ra \geqslant 10^6$

, flow tends to become more irregular, and dissolved solute is localised in the right half of the cylinder.

$Ra \geqslant 10^6$

, flow tends to become more irregular, and dissolved solute is localised in the right half of the cylinder.

As discussed earlier, in the absence of rotation, buoyancy causes the dissolved solute-laden heavier fluid to sink near the solute boundary and lighter fluid to rise near the cylinder, respecting mass conservation. As dissolution increases, this convective flow progressively becomes confined within the lower half of the cylinder (see supplementary movie 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2025.11009). When rotation is added to the cylinder, the upward flow near the cylinder is enhanced on the left. At the early stages of the dissolution, the qualitative feature of the flow remains similar on the left, barring fluid parcels moving faster near the cylinder, supported by the clockwise rotation of the cylinder. On the other hand, on the right, the upward flow of the fluid parcels near the cylinder is opposed by the clockwise-rotating cylinder. As a result, a region of upward-moving fluid parcels is formed, confined between two regions with downward-moving fluid parcels. The former carries fluid parcels atop the undissolved solute, leading to a forced convective flow and more dissolution on the left. With increasing dissolution of the solute, the clockwise flow (on the right) near the solute becomes progressively weaker, and the solute appears to be tilted on the right. We further noticed that the clockwise flow near the solute becomes weaker as the rotation speed increases, leading to only an anticlockwise flow near the solute and a clockwise flow near the cylinder (see supplementary movies 2–4).

Overall, we notice that rotation alters the flow topology that leads to the spreading of the dissolved solute around the interface instead of being localised only in the bottom half of the cylinder (

![]() $\varOmega = 0$

). This causes the concentration gradient near the upper part of the interface to be shallow, and, hence, the dissolution slows down.

$\varOmega = 0$

). This causes the concentration gradient near the upper part of the interface to be shallow, and, hence, the dissolution slows down.

To further explore the behaviour of the flow regimes, we trace trajectories of passive tracers released initially at the solute–fluid interface. These trajectories represent the respective pathlines of individual fluid particles coinciding with the tracer particle and reveal how the flow dynamics changes accordingly. The equations governing the trajectory of a particle

![]() $P$

with position

$P$

with position

![]() $(X_{\!P}(t), Y_{\!P}(t))$

are

$(X_{\!P}(t), Y_{\!P}(t))$

are

where the Eulerian velocity at its location gives the Lagrangian velocity of a particle. These equations are associated with initial conditions

![]() $X_{\!P}(t = 0) = X_{\!P}^0, \; Y_{\!P}(t = 0) = Y_{\!P}^0$

.

$X_{\!P}(t = 0) = X_{\!P}^0, \; Y_{\!P}(t = 0) = Y_{\!P}^0$

.

Figure 5. Pathlines of two passive tracers, released initially at

![]() $(0.0745, -1.0115)$

and

$(0.0745, -1.0115)$

and

![]() $(-0.0204, -1.9441)$

, for rotation speeds ranging from

$(-0.0204, -1.9441)$

, for rotation speeds ranging from

![]() $0$

to

$0$

to

![]() $1.5$

(shown left to right with an increment of

$1.5$

(shown left to right with an increment of

![]() $0.5$

). The respective trajectories of these particles are shown in green and blue. The initial positions of the tracers are marked with open markers, while their final positions are marked with the corresponding filled markers. Arrow markers along the pathlines denote the direction of particle motion. The red contour denotes the final shape of the undissolved solute, while

$0.5$

). The respective trajectories of these particles are shown in green and blue. The initial positions of the tracers are marked with open markers, while their final positions are marked with the corresponding filled markers. Arrow markers along the pathlines denote the direction of particle motion. The red contour denotes the final shape of the undissolved solute, while

![]() $+$

represents the centre of the cylinder.

$+$

represents the centre of the cylinder.

Figure 5 shows the trajectories of two tracer particles initially placed at

![]() $(X_{\!P}^0, Y_{\!P}^0) = (0.0745$

,

$(X_{\!P}^0, Y_{\!P}^0) = (0.0745$

,

![]() $-1.0115)$

and

$-1.0115)$

and

![]() $(X_{\!P}^0, Y_{\!P}^0) = (-0.0204, -1.9441)$

for

$(X_{\!P}^0, Y_{\!P}^0) = (-0.0204, -1.9441)$

for

![]() $Ra = 10^5$

and various rotation speeds ranging from 0 to 1.5. The initial positions of the tracers are chosen judiciously to capture the key features of the flow. The former (subsequently called ‘P1’) starts near the solute, where the flow variation is primarily dominated by buoyancy. On the other hand, the latter (subsequently called ‘P2’) is released near the cylinder, where the flow is dominated by rotation. The trajectories are tracked until 90 % dissolution of the solute is achieved. In the absence of rotation, P1 is driven by natural convection and follows a trajectory vertically downward before it moves upward along the cylinder wall, whereas P2 experiences upward motion only (see supplementary movie 5).

$Ra = 10^5$

and various rotation speeds ranging from 0 to 1.5. The initial positions of the tracers are chosen judiciously to capture the key features of the flow. The former (subsequently called ‘P1’) starts near the solute, where the flow variation is primarily dominated by buoyancy. On the other hand, the latter (subsequently called ‘P2’) is released near the cylinder, where the flow is dominated by rotation. The trajectories are tracked until 90 % dissolution of the solute is achieved. In the absence of rotation, P1 is driven by natural convection and follows a trajectory vertically downward before it moves upward along the cylinder wall, whereas P2 experiences upward motion only (see supplementary movie 5).

Cylinder rotation significantly alters the particle trajectories. Particles P1 and P2 primarily traverse in the anticlockwise and clockwise directions, respectively. However, for each

![]() $\varOmega$

, we observe a unique and distinct characteristic of the particle trajectories. When buoyancy dominates rotation (

$\varOmega$

, we observe a unique and distinct characteristic of the particle trajectories. When buoyancy dominates rotation (

![]() $\varOmega = 0.5$

), the trajectory of P1 is confined to the right half of the cylinder for the majority of the dissolution, except at a later stage when the solute shrinks significantly and the particle has to traverse a small distance to end on the left half of the cylinder. Nonetheless, it eventually ends up on the right half (filled green marker) of the cylinder after spending a small duration on the left. For the same flow parameters, P2 initially rotates in the clockwise direction in accordance with the clockwise motion of the cylinder. However, before completing a full revolution around the solute, the particle is caught in the anticlockwise-rotating fluid parcels on the right, attracting P2 towards the solute. Subsequently, the particle traverses around the solute in the anticlockwise direction and re-enters the clockwise-rotating boundary layer adjacent to the cylinder (see supplementary movie 6).

$\varOmega = 0.5$

), the trajectory of P1 is confined to the right half of the cylinder for the majority of the dissolution, except at a later stage when the solute shrinks significantly and the particle has to traverse a small distance to end on the left half of the cylinder. Nonetheless, it eventually ends up on the right half (filled green marker) of the cylinder after spending a small duration on the left. For the same flow parameters, P2 initially rotates in the clockwise direction in accordance with the clockwise motion of the cylinder. However, before completing a full revolution around the solute, the particle is caught in the anticlockwise-rotating fluid parcels on the right, attracting P2 towards the solute. Subsequently, the particle traverses around the solute in the anticlockwise direction and re-enters the clockwise-rotating boundary layer adjacent to the cylinder (see supplementary movie 6).

For

![]() $\varOmega \gt 1$

, when rotation dominates buoyancy, P1 remains confined within a neighbourhood of the initial interface position. In particular, for

$\varOmega \gt 1$

, when rotation dominates buoyancy, P1 remains confined within a neighbourhood of the initial interface position. In particular, for

![]() $\varOmega = 1.5$

, it is evident from figure 5 that the particle exhibits a cyclic motion around the solute. The broken symmetry of the trajectory is attributed to the buoyancy that causes a departure of the particle from a perfect cyclic motion. However, as

$\varOmega = 1.5$

, it is evident from figure 5 that the particle exhibits a cyclic motion around the solute. The broken symmetry of the trajectory is attributed to the buoyancy that causes a departure of the particle from a perfect cyclic motion. However, as

![]() $\varOmega$

increases, the asymmetry becomes less prominent, and the number of revolutions of the trajectory around the solute increases (not shown for brevity). See supplementary movie 7.

$\varOmega$

increases, the asymmetry becomes less prominent, and the number of revolutions of the trajectory around the solute increases (not shown for brevity). See supplementary movie 7.

Finally, for

![]() $\varOmega = 1$

, we observe that, initially, P1 follows a trajectory similar to that for

$\varOmega = 1$

, we observe that, initially, P1 follows a trajectory similar to that for

![]() $\varOmega = 0.5$

. However, instead of being confined within the right half of the cylinder, it revolves around the solute as time progresses. After a couple of revolutions around the solute, the particle is slowly pushed away from the interface by a strong buoyant force below the solute. This process continues for a while before the particle is eventually trapped within the boundary layer near the cylinder wall and traverses in the clockwise direction. As anticipated, for both

$\varOmega = 0.5$

. However, instead of being confined within the right half of the cylinder, it revolves around the solute as time progresses. After a couple of revolutions around the solute, the particle is slowly pushed away from the interface by a strong buoyant force below the solute. This process continues for a while before the particle is eventually trapped within the boundary layer near the cylinder wall and traverses in the clockwise direction. As anticipated, for both

![]() $\varOmega = 1$

and

$\varOmega = 1$

and

![]() $\varOmega = 1.5$

, P2 rotates in the clockwise direction confined within the boundary layer near the cylinder (see supplementary movie 8).

$\varOmega = 1.5$

, P2 rotates in the clockwise direction confined within the boundary layer near the cylinder (see supplementary movie 8).

The above observations of particle paths indicate that the fluid adjacent to the cylinder wall flows in the clockwise direction, while the fluid adjacent to the interface experiences an overall anticlockwise motion. For all the cases under consideration in figure 5, the pathlines are smooth, regular and do not exhibit any disorderly behaviour, a signature of laminar flow. This behaviour is particularly evident at higher rotation speeds, for which the trajectories exhibit smooth circular motions around the solute.

4.2. Quantitative impacts of rotation and buoyancy on solute transport

In this section, we quantify dissolution, mixing and interface shape due to nonlinear interactions between fluid flow and solute dissolution over a wide range of rotation speed (

![]() $\varOmega$

) and Rayleigh number (

$\varOmega$

) and Rayleigh number (

![]() $Ra$

).

$Ra$

).

4.2.1. Dissolution time of the solute

Our numerical experiments are carried out until the solute experiences

![]() $95\,\%$

dissolution. Using these simulated data, we predict the time required for complete solute dissolution using spline extrapolation. Table 1 lists the time for the complete dissolution for Rayleigh numbers varying by two orders of magnitude and

$95\,\%$

dissolution. Using these simulated data, we predict the time required for complete solute dissolution using spline extrapolation. Table 1 lists the time for the complete dissolution for Rayleigh numbers varying by two orders of magnitude and

![]() $\varOmega$

ranging from 0 to 1.5. Interestingly, rotation-induced forced convection does not enhance dissolution. Rather, for a fixed Rayleigh number, the dissolution process slows down as the rotation speed increases due to a shallow concentration gradient at the interface. We further note, for

$\varOmega$

ranging from 0 to 1.5. Interestingly, rotation-induced forced convection does not enhance dissolution. Rather, for a fixed Rayleigh number, the dissolution process slows down as the rotation speed increases due to a shallow concentration gradient at the interface. We further note, for

![]() $Ra = 10^5$

and

$Ra = 10^5$

and

![]() $10^6$

, a rotation speed

$10^6$

, a rotation speed

![]() $\varOmega = 1.5$

can significantly delay the complete dissolution of the solute with an almost 85 %–94 % increase in complete dissolution as compared with the case at

$\varOmega = 1.5$

can significantly delay the complete dissolution of the solute with an almost 85 %–94 % increase in complete dissolution as compared with the case at

![]() $\varOmega = 0$

. Whereas, for

$\varOmega = 0$

. Whereas, for

![]() $Ra = 10^7$

, the time taken for complete dissolution with

$Ra = 10^7$

, the time taken for complete dissolution with

![]() $\varOmega = 1.5$

increases only up to 8 %–9 % relative to the case of no rotation. In summary, the relative strength of rotation to buoyancy plays a critical role in determining the dissolution of the solute. It appears that there exists a critical rotation speed

$\varOmega = 1.5$

increases only up to 8 %–9 % relative to the case of no rotation. In summary, the relative strength of rotation to buoyancy plays a critical role in determining the dissolution of the solute. It appears that there exists a critical rotation speed

![]() $\varOmega _{\textit{cric}}(Ra)$

such that for

$\varOmega _{\textit{cric}}(Ra)$

such that for

![]() $\varOmega \lt \varOmega _{\textit{cric}}(Ra)$

, dissolution has a weak dependence on rotation. Our prediction further indicates that

$\varOmega \lt \varOmega _{\textit{cric}}(Ra)$

, dissolution has a weak dependence on rotation. Our prediction further indicates that

![]() $\varOmega _{\textit{cric}}$

increases with

$\varOmega _{\textit{cric}}$

increases with

![]() $Ra$

.

$Ra$

.

Table 1. Time required for solute dissolution at various Rayleigh numbers and rotation speeds.

Figure 6. Concentration of dissolved and undissolved solute in the absence of rotation and buoyancy: (a) initially (

![]() $t = 0$

) and (b) at a later time (

$t = 0$

) and (b) at a later time (

![]() $t \gt 0$

). Dissolution recedes the interface (red) radially. Due to this rotational symmetry, the Stefan problem associated with the dissolution can be studied through a one-dimensional model. (c) The concentration profile in the radial direction is shown from top to bottom at

$t \gt 0$

). Dissolution recedes the interface (red) radially. Due to this rotational symmetry, the Stefan problem associated with the dissolution can be studied through a one-dimensional model. (c) The concentration profile in the radial direction is shown from top to bottom at

![]() $t = 0$

,

$t = 0$

,

![]() $t = 7.5$

(early time),

$t = 7.5$

(early time),

![]() $t = 30$

(intermediate time) and

$t = 30$

(intermediate time) and

![]() $t = 60$

(later time).

$t = 60$

(later time).

We now aim to theoretically estimate a relationship for the solute dissolution time. To achieve this, we first consider a scenario where the effects of buoyancy and rotational forces are neglected. In such cases, the chosen problem is driven solely by diffusion forces, which reduces it to a classical one-dimensional phase-change problem in the radial direction due to the symmetric nature of the system. Let

![]() $r_s(t)$

and

$r_s(t)$

and

![]() $r_d(t)$

denote the radius of the undissolved solute and the distance traversed by the solid–liquid interface from its initial position, respectively, at an instantaneous time

$r_d(t)$

denote the radius of the undissolved solute and the distance traversed by the solid–liquid interface from its initial position, respectively, at an instantaneous time

![]() $t$

(see figure 6). Thus, we have

$t$

(see figure 6). Thus, we have

Overall, the problem can be viewed as the dissolution of a solute block in a fluid, with an expanding fluid region. Resorting to

![]() $c(r = r_d(t), t) = 1$

and following the analysis of Stefan (Reference Stefan1891), we obtain

$c(r = r_d(t), t) = 1$

and following the analysis of Stefan (Reference Stefan1891), we obtain

![]() $r_d(t)\propto \sqrt {t}$

. Thus, from (4.2) we derive

$r_d(t)\propto \sqrt {t}$

. Thus, from (4.2) we derive

where

![]() $k$

is a constant of proportionality. The above-mentioned scaling relation is valid until the dissolved solute reaches the cylinder wall. Therefore, in the present study, the finite-size effect of the fluid region leads to a breakdown of the said power-law behaviour. We performed numerical simulations by neglecting buoyancy and rotation in our model formulation and determined the interface evolution, which agrees excellently with

$k$

is a constant of proportionality. The above-mentioned scaling relation is valid until the dissolved solute reaches the cylinder wall. Therefore, in the present study, the finite-size effect of the fluid region leads to a breakdown of the said power-law behaviour. We performed numerical simulations by neglecting buoyancy and rotation in our model formulation and determined the interface evolution, which agrees excellently with

![]() $k \sqrt {t}$

for

$k \sqrt {t}$

for

![]() $k = 0.08$

(correct up to two decimal places) up to

$k = 0.08$

(correct up to two decimal places) up to

![]() $t \lesssim 30$

(see figure 7

a).

$t \lesssim 30$

(see figure 7

a).

Figure 7. Time required for the gradual dissolution of the solute: (a) without buoyancy or rotation, (b) for various rotation speeds at a fixed Rayleigh number

![]() $Ra \approx 10^5$

and (c) for various Rayleigh numbers at fixed rotation speed

$Ra \approx 10^5$

and (c) for various Rayleigh numbers at fixed rotation speed

![]() $\varOmega = 1$

. Solid curves represent numerical results up to 90 % dissolution. The dashed line, proportional to

$\varOmega = 1$

. Solid curves represent numerical results up to 90 % dissolution. The dashed line, proportional to

![]() $\sqrt {t}$

, is shown as a guide to the eye. Square markers denote the predicted time for complete dissolution given in table 1.

$\sqrt {t}$

, is shown as a guide to the eye. Square markers denote the predicted time for complete dissolution given in table 1.

Effects of

![]() $Ra$

and

$Ra$

and

![]() $\varOmega$

on the evolution of

$\varOmega$

on the evolution of

![]() $r_d(t)$

and hence

$r_d(t)$

and hence

![]() $A_d(t)$

are investigated next. We numerically compute

$A_d(t)$

are investigated next. We numerically compute

![]() $A_d(t)$

, defined in (B3), for different values of

$A_d(t)$

, defined in (B3), for different values of

![]() $Ra$

and

$Ra$

and

![]() $\varOmega$

. For a fixed

$\varOmega$

. For a fixed

![]() $Ra$

, the evolution of

$Ra$

, the evolution of

![]() $A_d(t)$

is independent of

$A_d(t)$

is independent of

![]() $\varOmega$

at the early stages of the dissolution. For example, with

$\varOmega$

at the early stages of the dissolution. For example, with

![]() $Ra = 10^5$

, the effects of rotation become evident at

$Ra = 10^5$

, the effects of rotation become evident at

![]() $A_d(t) \gtrsim 0.25$

(see figure 7

b). Provided the evolution of the dissolved solute area satisfies the relation (4.3), one infers that

$A_d(t) \gtrsim 0.25$

(see figure 7

b). Provided the evolution of the dissolved solute area satisfies the relation (4.3), one infers that

![]() $k$

depends on

$k$

depends on

![]() $\varOmega$

in such a way that with increasing

$\varOmega$

in such a way that with increasing

![]() $\varOmega$

,

$\varOmega$

,

![]() $k^2 t$

is dominated by

$k^2 t$

is dominated by

![]() $2 k \sqrt {t}$