I. Introduction

In Mbiuni, a town in a dry region of eastern Kenya, sand miners from Nairobi nearly destroyed the only local sources of drinking water. Sand retains water – removing it in vast quantities causes the water table to drop. A prominent woman from Mbiuni, Mary M., said simply: “The water catchment was on the verge of drying up … Water is very precious here. Without it we will all be dead.”

Mary and several other community members approached the police, the district officer, and the local chief to complain. Every one of those officials claimed he lacked the authority to act against the miners. Desperate, some people set fire to a truck that came to pick up sand. Police arrested and imprisoned two of the demonstrators. The mining continued.

Where were the people of Mbiuni supposed to go? Kenya adopted national guidelines on sand harvesting in 2007. According to the guidelines, no one can mine sand outside of sites approved by district-level sand-harvesting committees. The committees are supposed to designate sites only after considering social and environmental risks.Footnote 1

The mine in Mbiuni was not in an approved site. Mary and others in Mbiuni hadn’t seen the guidelines and didn’t know approval was required. The district officer didn’t mention the guidelines when they approached him. Mary suspected that he and other officials were receiving a cut of the revenue from the mine.

The situation of the Mbiuni residents is not uncommon. For perhaps a majority of human beings – 4 billion people as estimated by the UN Commission on Legal Empowerment – the promises of law and government are often unmet.Footnote 2 Many people have never heard of laws that are supposed to protect them. Others cannot avail themselves of nominally good rules and systems because of cost, dysfunction, corruption, or abuse of power. In many other cases, the law itself is unjust. As a result, people are denied even basic rights to dignity, safety, and livelihood.

Advancing justice requires at least three elements. First, people need to conceive of themselves as bearers of rights, as agents capable of action. In other words, they must undergo that transformation of outlook in which, as Hannah Pitkin puts it, “I want” becomes “I am entitled to.”Footnote 3 Second, state institutions – administrative agencies, legislatures, the courts – need to be fair, effective, and responsive to their citizens. Much of political science is about how to make governments more so. Third, in our view, there is a need for intermediary institutions that assist citizens in exercising their rights.Footnote 4 In other words, there needs to be, as Gauri and Brinks describe it, a “legal support structure appropriate to the claims being brought, in light of the institutional requirements” in any given context.Footnote 5

There are many kinds of intermediary institutions. Political parties and unions, for example, serve as intermediaries for electoral politics and workplaces respectively. Public interest lawyers help people access formal courts. Ombudsman offices serve as intermediaries for citizens seeking to resolve grievances against the state. In this book, we aim to characterize and assess a lesser-known intermediate institution – the community paralegal.

According to the 2012 Kampala Declaration on Community Paralegals, community paralegals “use knowledge of law and government and tools like mediation, organizing, education, and advocacy to [help people] seek concrete solutions to instances of injustice.”Footnote 6

While conventional paralegals typically serve as back-office assistants to lawyers, community paralegals – also known as community legal workers, or barefoot lawyers – work directly with people affected by injustice. Because these community paralegals help people to understand and use the law themselves, their work is often referred to as “legal empowerment.”

Stephen Golub, who coined the phrase “legal empowerment” in the early 2000s, distinguishes legal empowerment from what he calls the “rule of law orthodoxy.” Golub describes rule of law orthodoxy as “a ‘top-down,’ state-centered approach [that] concentrates on law reform and government institutions, particularly judiciaries, to build business-friendly legal systems that presumably spur poverty alleviation.” In contrast, legal empowerment focuses on placing the power of law in the hands of ordinary people.Footnote 7

Throughout this volume, when we use the term “paralegal,” we are referring to community paralegals rather than conventional paralegals unless we specify otherwise.

Community paralegals and their clientsFootnote 8 typically address three kinds of problems: disputes among people, grievances by people against state institutions, and disputes between people and private firms. Sometimes these cases involve individuals seeking justice; often they involve groups or entire communities.

Paralegals aim to help people achieve practical remedies: a group of workers wins unpaid back wages from their employer; a fishing community secures environmental enforcement against a factory releasing illegal effluents into the sea; a mother receives support for her children from a derelict father.

Like community health workers – who have an established place in health care delivery systems around the worldFootnote 9 – community paralegals are close to the communities in which they work and deploy a flexible set of tools. Also like community health workers, paralegals work in tandem with a strong, typically well-organized profession. While community health workers refer difficult cases to doctors and the formal medical system, community paralegals are typically connected to lawyers who can engage in litigation or high-level advocacy if the paralegals’ frontline methods fail.

In Mbiuni, after local authorities refused to take action, and public demonstrations led to violence and arrests but no progress, Mary and others approached a pair of community paralegals. The paralegals organized two public meetings, attended by 400 people each, in which they suggested the community use the law. The paralegals explained the sand-harvesting guidelines and other regulations related to natural resources.

The chief and assistant chief objected to the gatherings, but the paralegals urged the community not to be afraid. The paralegals helped community members draft a written petition to several agencies, including the National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA), which issued the sand harvesting guidelines. NEMA responded: it ordered the operation to close, and requested the provincial administration to enforce its order.

The mining stopped. According to Mary, “now there is enough water.” She said, “the paralegals cooled tempers, educated us and even told [people involved in mining] the legal provisions on sand harvesting … The law says water catchment areas belong to the community … We have said no to sand mining forever.”

Mary could be overestimating the victory. Sand-mining cartels are very powerful in Kenya, as they are in many countries.Footnote 10 The profits at stake are often enough to overcome legal prohibitions and the officials who are supposed to enforce them. It’s hard to say how long the “no” from the community will hold. But those two paralegals helped Mary and others bend a hopeless situation in the direction of justice.

Community paralegals of different kinds exist throughout the world,Footnote 11 and date back to at least the 1950s, when Black Sash and other organizations deployed paralegals to help nonwhite South Africans navigate and defend themselves against apartheid. Community paralegals are recognized by legislation in Afghanistan, Indonesia, Kenya, Malawi, Moldova, Mongolia, New Zealand, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Uganda, England and Wales, and Ontario and British Columbia in Canada.Footnote 12

The NGO BRAC has one of the largest paralegal efforts in the world – it deploys more than 6,000 paralegals or “barefoot lawyers” and has addressed more than 2 million complaints through its legal aid clinics.Footnote 13 Community paralegals have attracted increasing attention from international organizations, including the UN Commission on Legal Empowerment.Footnote 14

Proponents of the paralegal approach have suggested the following four advantages, among others:

Empowerment. A conventional legal aid approach tends to treat people as victims requiring a technical service. In contrast, paralegals aspire to cultivate the knowledge and power of the people with whom they work. Not “I will solve this problem for you,” but “We will solve it together, and in the process we will both grow.”

Mixed methods. Community paralegals combine several strategies: advocacy, mediation, organizing, monitoring, and education. This allows them to pursue creative and constructive solutions to justice problems. Paralegals can tailor their approach in any given case to the wishes of the communities with whom they work.

Creative about institutions. Community paralegals don’t focus on the judiciary alone. They pursue remedies everywhere: administrative agencies, local governments, accountability bodies like ombudsmen and human rights commissions, parliaments, customary justice institutions, and others.

Cost-effectiveness and scale. Lawyers are the conventional providers of legal services, but lawyers are often costly and difficult to access. In many countries, one finds a few ad hoc legal aid centers, often in capital cities, and no serious attempt to reach those in the countryside. The paralegal approach poses a more plausible model for delivering primary justice services to all.Footnote 15

On the other hand, a paralegal approach has several potential problems and limitations. For example:

Limits on effectiveness. Paralegal involvement in local, intra-community disputes can be redundant with existing institutions. In conflicts with the state or with private firms, on the other hand, paralegals and their clients may not be able to win against powerful interests.

Consistency and quality. Without rigorous training, supervision, and support, paralegal efforts can be of inconsistent quality.

Risk of abuse. Paralegals can use their knowledge and status to take advantage of others.

Sustainability. Funding from donors, development agencies, and governments can prove inadequate and unreliable.

There has been relatively little systematic study of the workings of paralegal programs. In “Nonlawyers as Legal Resources for Their Communities,” Stephen Golub describes Ford Foundation grantees deploying paralegals in Asia, Latin America, and Africa.Footnote 16 In “Legal Empowerment: Advancing Good Governance and Poverty Reduction,” Golub and Kim McQuay document paralegal work in several Asian countries.

One of us (Vivek) offered an overview of paralegal efforts around the world in a 2006 article that was primarily about the methodology of the Sierra Leonean program Timap for Justice.Footnote 17 Another of us (Varun) has presented theoretical accounts of the kind of “legality” that paralegals engage with, and of the pathways through which paralegals can promote economic and social outcomes for poor individuals.Footnote 18

A 2017 review of evidence on civil society efforts at legal empowerment, which considered academic articles as well as “grey” literature like organizational reports and conference papers, turned up twenty-nine pieces that deal with paralegals, not including the ones in this book.Footnote 19 The majority was published in the past decade. Most of these pieces are case studies of individual programs; some involved research on impact.

For example, Jacobs, Saggers, and Namy studied a pilot program in Lowero District, Uganda that deployed paralegals to educate people about women’s land rights and to address individual disputes. The authors drew on surveys, interviews with clients and paralegals, and the program’s internal monitoring data. They found that paralegals were able to resolve many cases quickly – 17 percent of the cases brought to paralegals resulted in mediation agreements between disputing parties. For another 33 percent of cases, paralegals referred people to institutions like the local council or the local council court. In general clients praised paralegals for being accessible and responsive, in contrast to formal institutions that they found expensive, slow, and hard to reach.Footnote 20

Sunil Kumar narrates the experience of a government-sponsored program in Andhra Pradesh, India, which also sought to improve access to land rights for poor rural women. The Society for Elimination of Rural Poverty in the state’s Rural Development Department trained community-based paralegals and community-based surveyors to work with women’s self-help groups. The program was piloted in 2004 and extended to all twenty-two districts of the state in 2006.

Between 2006 and 2010, paralegals and community surveyors identified land problems of 610,000 rural poor people involving 1.18 million acres of land. Of those, the paralegals and community surveyors helped to resolve the problems of 430,000 people, which involved 870,000 acres of land. The National Rural Livelihoods Mission committed to scale up this approach to several more states throughout the country.Footnote 21

Rachael Knight and her coauthors conducted a two-year randomized controlled trial in Liberia, Mozambique, and Uganda that compared the effectiveness of paralegals with two other ways of protecting community land rights. Organizations in all three countries supported communities to document customary land claims, resolve boundary disputes, and strengthen the rules and structures for governing community lands.

Knight and her colleagues found that paralegals were more effective than both a full legal services approach, in which communities had direct assistance from lawyers, and a pared-down rights education approach, in which information was provided and little else. They observed that communities receiving full legal services tended to place their hopes with the outside professionals, while communities with paralegals tended to take greater ownership over the process.Footnote 22

Scholars have conducted two evaluations of the Sierra Leonean legal empowerment group Timap for Justice.Footnote 23 In one study by Pamela Dale, researchers selected forty-two cases from Timap’s docket and interviewed all parties involved. Dale reports that respondents were “overwhelmingly positive” about their experiences with Timap paralegals. Respondents “praised Timap’s effectiveness in resolving difficult disputes, particularly those that confront institutions or power relationships.”Footnote 24

A second evaluation focused on a newer program, in which Timap trains paralegals to work in police stations and prisons. The paralegals educate detainees and remand prisoners about criminal law and assist them with basic procedures like bail petitions. This initiative was modeled in part on the Paralegal Advisory Service in Malawi, which has deployed paralegals in prisons since 2000.

Justin Sandefur, Bilal Siddiqui, and Alaina Varvaloucas used a difference-in-difference approach to compare prisons in which Timap paralegals were working with other prisons where there were no paralegals. They found that the paralegal intervention led to a 13 percent increase in the share of detainees receiving bail and a 20 percent decrease in the share of prisoners held without trial or conviction.Footnote 25

The evidence on paralegal approaches is not limited to the developing world. Jay Wiggan and Colin Talbot review literature on citizen advocates in the United Kingdom who help people to understand and access basic welfare benefits. Wiggan and Talbot find that “welfare rights advisors” increase participation in public entitlements and improve the living standards and mental health of their clients.Footnote 26

Rebecca Sandefur and Thomas Clarke studied the work of non-lawyer “access to justice navigators” who assist self-represented litigants in housing and civil courts in New York City. The navigators help people to understand the legal process and to prepare basic documents, like a tenant’s “answer” to a landlord’s petition for nonpayment of rent.

Normally, one in nine nonpayment of rent cases in New York City leads to eviction. Many of the evictions result from imbalances of power between landlords and tenants. Sandefur and Clarke found that navigators could narrow those imbalances considerably, at a very low cost. Out of 150 cases handled by one set of navigators in the borough of Brooklyn, Sandefur and Clarke found no evictions at all.Footnote 27

Together, these studies suggest that community paralegals succeed in advancing justice in some circumstances, and that the advantages posited earlier in this chapter – empowerment, mixed methods, institutional creativity, cost-effectiveness – do apply, at least in some cases. There is very little existing research, however, on the factors that shape paralegal work, and the way paralegals interact with political and social context. We pay particular attention to those questions here.

This is the first book on the subject, and the first effort to bring together original empirical work on multiple paralegal programs from several countries, using a structured and explicitly comparative approach. By taking a comparative approach, we are able to venture more generalized conclusions, which extend beyond a particular program in a particular place.

In the next section, we describe the scope and methods of our research. After that we discuss the methodology of paralegals themselves, in particular the six approaches we found them using in their work. We then explore how three sets of factors shape community paralegal efforts: government institutions, culture, and paralegal organizations. We close with a summary of our findings and a reflection on the role of paralegals in deepening democracy.

II. Methods and Scope

This book considers community paralegals in six countries. We chose to study South Africa and the Philippines because they have some of the oldest and richest experience with paralegals, dating back to the 1950s and 1970s, respectively. In the other four countries – Indonesia, Kenya, Sierra Leone, and Liberia – community paralegals are more recent but are now serving significant portions of the population, and are the subject of current national policy debate. In Indonesia, Kenya, and Sierra Leone, recent legal aid laws recognize the role paralegals play and call for expansion of paralegal services.Footnote 28 We have organized the chapters by the longevity of the paralegal movements, with South Africa first and Liberia – where paralegals began to operate in 2007 – last.

In five of the countries (all but Liberia) we adopted an explicitly comparative approach in advance. The research teams first met in Washington, DC, in 2010 to discuss a shared methodology and approach. The core elements were (a) to study paralegal programs empirically, using case-tracking methods and a counterfactual where possible; and (b) to examine the factors – institutional, cultural, and organizational – that affect the nature and the effectiveness of paralegal efforts. Having developed this common approach, each of the country teams was free to adapt the methods in light of its specific circumstances.

All six research teams conducted interviews with paralegal organizations, including paralegals themselves, lawyers, and other program staff. The teams reviewed organization documents, including data on cases when they were available. All teams also interviewed key stakeholders in executive and judicial branches of government, as well as in the private bar.

Everywhere except the Philippines, the teams undertook some form of case tracking: selecting a sample of cases handled by paralegals and interviewing clients and others involved in those cases. The teams in Indonesia and Sierra Leone followed the same case-tracking process in similar areas where paralegals were not operating, in order to establish a basis for comparison. Researchers identified cases in those non-paralegal areas by interviewing chiefs and other leaders who commonly address disputes.

The Liberia chapter draws on interviews with stakeholders conducted by the chapter authors as well as a randomized controlled trial led by two other researchers, Justin Sandefur and Bilal Siddiqui.Footnote 29 The randomized controlled trial compared people who had help from a paralegal with people who had requested help but not yet received it.

The findings in the South Africa, Philippines, and Kenya chapters are largely qualitative, while the Indonesia, Sierra Leone, and Liberia chapters blend qualitative and quantitative analysis. Some variations in methodology were due to local circumstances, others to time and resource constraints. Despite the variation, we believe there is enough commonality across the six studies to yield meaningful comparative insight.

III. Modes of Action: How Paralegals Work

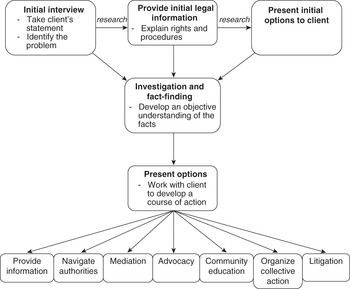

What exactly do community paralegals do? In our research we found paralegals using six broad approaches: (1) education, (2) mediation, (3) organizing, (4) advocacy, (5) monitoring, and, with the help of lawyers, (6) litigation. Most of these approaches appear, for example, in the diagram that follows, from the Timap for Justice paralegal manual, on the steps Timap paralegals take to address a case.

Paralegals try to demystify law – to transform it from something abstract and intimidating into something that people can understand, use, and shape. In all six countries, paralegals dedicate significant time to educating communities about laws that affect them. In Indonesia, paralegals conduct village-level discussions on topics like contract law, corruption, the rights of criminal suspects, and a 2004 law on domestic violence. Similar meetings in Liberia often address women’s rights, land rights, and labor rights.

In the two countries where we quantified comparisons between those receiving paralegal services and “control” populations – Sierra Leone and Liberia – we found that parties in cases handled by paralegals were significantly more likely than their counterparts to have knowledge of relevant national law.

Figure 1.1 Steps in solving justice problems.

But raising legal awareness by itself is usually not enough. Paralegals go further: they walk with clients toward a solution. In citizen versus citizen disputes, paralegals often attempt mediation. In Northwest Province of South Africa, for example, members of a burial society approached a paralegal at the Lethabong community advice office, whom they heard about from workers on neighboring farms. Two members of their society had failed to make the agreed financial contributions, and the rest of the membership had to bear the burden. The paralegal conducted a three-hour mediation – in the end, the two defaulters acknowledged their debt and agreed to pay it off in monthly installments. In Sierra Leone and Liberia, mediation was the approach paralegals used most often.

Paralegal mediations tend to differ from those conducted by other local dispute resolvers – a village chief, say, or a religious elder – in that paralegals inject information about the law, and are willing to assist a wronged party to pursue a remedy if mediation fails. This is one of the ways that paralegals “enlarge,” as Berenschot and Rinaldi write in the Indonesia chapter, “the shadow of the law.”

A common step beyond mediation is organizing community members for collective action.Footnote 30 After mediating between the burial society and its defaulting members, the paralegal from Lethabong helped the society draft a constitution and formal membership agreement, so that the rules would be clearer and more easily enforced in the future.

In cases involving government or private firms, paralegals often combine organizing and advocacy. The sand-mining case from Kenya with which we opened the chapter involved both organizing and advocacy. So too a case from Indonesia, in which a nationwide fund for village-level infrastructure projects called PNPM (Program Nasional Pemberdayaan Mandiri) allocated resources for only half of the village of Bandung Baru in Lampung Province.

A paralegal named Ulhaidi educated people from the neglected half of the village about the policies governing PNPM. He then organized them to demonstrate outside the village headman’s house. They demanded that the headman request PNPM officials to provide resources for the entire village; the headman made the request, and the PNPM officials complied.

Paralegals do not always wait for community members to approach them with problems; in some cases, they actively monitor for possible rights violations. In the Philippines, for example, some paralegals supported by the Alternative Law Groups take water samples to examine the impact of tailings from mines on community water supply. When they identify violations, paralegals and communities use the evidence to lodge complaints with the Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

When both mediation and advocacy fail, paralegals sometimes turn to lawyers to litigate. In 2014 in the Nimiyama chiefdom of Sierra Leone, seventy families woke up to find poles erected on the land they have farmed for generations. Their paramount chief had sold 1,400 acres to a Chinese rubber company without asking them.

Blocked from entering their land, some of them moved to neighboring chiefdoms to find work as laborers. Some stayed, hoping to challenge the sale. The ones who stayed connected with two paralegals working in the region, Hassan Sesay and Fatmata Kanu.

Hassan and Fatmata explained that the deal between the chief and the rubber company was illegal. At most the chief could have leased farmland – outright sale of customary land is prohibited by law – but even that would have required the consent of the families who have customary rights to it.

The paralegals helped the families try for redress – they approached the chief and the company directly, and they engaged the ministries of land and agriculture. But in this case, the firm and the chief were intransigent, and the ministries were unresponsive. So the families and paralegals partnered with a single Sierra Leonean lawyer, Sonkita Conteh, to bring a case in the High Court.

After a long litigation, the High Court ordered in February 2016 that the company return the land and pay reparations for the damage that was done.Footnote 31 The families were able to return to their farms in time for planting season. Fanta Nyanda, one of the women whose land it was, said at the courthouse the day the judgment came out: “We now know the law is for us.”Footnote 32

A successful court judgment – like a positive new law or regulation – offers a lever paralegals and communities can use in the future. Paralegals in Sierra Leone have educated people about the Nimiyama judgment via radio and community meetings, with the aim of stopping land grabs before they happen.

Community paralegals are not the only ones who apply these various approaches. Governments and many civic organizations provide education about the law. Respected members of society – customary authorities, religious leaders, family elders – often mediate local disputes. For grievances with the state or with private firms, those same leaders, as well as members of political, social, or trade associations, sometimes organize collective action and advocate for remedies. The private bar engages in litigation, as do some public interest lawyers who are not connected to community paralegals.

What distinguishes community paralegals is the way they combine these various approaches. They do not stop at educating people about the law; they actively seek remedies. When voluntary mediation does not result in an agreement in an intra-community dispute, they assist the wronged party to pursue other channels of redress. Their organizing and advocacy are informed by their understanding of law and government, and are bolstered by their connection to lawyers and the possibility of litigation.

Some social workers, trade unionists, and community organizers may indeed combine these six approaches in ways very similar to that of paralegals, without referring to themselves as such. The findings in this book may have relevance for those other actors as well, irrespective of which term they use.

IV. Factors that Shape Paralegal Efforts: Institutions, Culture, and Organizations

We found evidence of paralegal effectiveness in all six countries. In Liberia, people who had worked with paralegals demonstrated significantly greater knowledge of law than people who hadn’t. Paralegal clients were also 35 percent more likely to think that the outcome of their case was fair and 37 percent more likely to be satisfied with the outcome.Footnote 33 In the other countries, findings on effectiveness were qualitative rather than quantitative, but thematically similar. We heard repeatedly that help from a paralegal increased people’s understanding of law and government, increased their confidence to take action, and allowed them to achieve at least a partial solution to an injustice they would have otherwise had to bear.Footnote 34

But the specific nature of paralegal work varied greatly: the types of cases paralegals take on, for example, or the institutions they engage, or the kinds of remedies they’re able to achieve, or the scale at which they operate, or the extent to which governments are responsive to their efforts. We saw variation across countries, across organizations, and across individual paralegals.

In the remainder of this chapter we draw conclusions about the factors that shape the nature of paralegal efforts. We divide our findings according to three kinds of factors: institutional (the nature of a legal system and government), social (norms and culture), and organizational (the way a program is run). This typology of factors emerged from the collaborative workshop we held with research teams, and it serves as the general explanatory framework in each of the chapters in this book, though variously adapted to match the data available in each country context. Our interpretations in this comparative chapter grow directly from the country-level empirical work, though in some cases, our views may not be identical to those of the country study authors.

V. Political and Legal Institutions

A. Paralegals in the Justice Landscape

1. From Resisting Repressive Regimes to Realizing the Promises of Democracy, and Back Again

The kinds of injustices paralegals take on and their chances of winning are shaped by the legal and governance climate in which paralegals work. In three countries in our study, paralegals at first helped people to navigate and survive repressive regimes. In South Africa, community paralegals emerged in the 1950s, during apartheid. Some were based in African National Congress offices, some worked from the homes of community leaders, and others were supported by the NGO Black Sash. Paralegals assisted people of color to defend themselves against repressive laws, in particular pass laws and others that restricted movement. They also monitored and publicized the conditions of people who were forcibly displaced.

In the 1970s in the Philippines, during the dictatorship of President Marcos, the Free Legal Assistance Group began training paralegals to provide “first aid legal aid,” often for people accused of violating martial law. During the New Order in Indonesia, two legal aid movements emerged, both deploying paralegals: bantuan hukum structural – structural legal aid – in the 1970s and pendidikan hukum kritis – critical legal education – in the 1990s. Paralegals in both movements supported communities to pursue women’s rights and rights related to land, natural resources, and labor. Pendidikan hukum kritis placed particular emphasis on customary legal regimes as alternatives to inherently repressive official law.

In all three of these repressive regimes – apartheid South Africa, the Philippines under Marcos, and New Order Indonesia – paralegals sought to mobilize communities to change laws and government structures, though many of those efforts were thwarted and paralegals themselves were often subject to repression.

As these countries underwent transitions toward democracy, the paralegals in each one devoted more time to the realization of newly codified legal rights. The combination of progressive, pro-poor legislation with massive gaps in the state’s capacity to deliver (the existence of “big policies in small states”Footnote 35) creates an opportunity for paralegals.Footnote 36 Paralegals can help citizens hold the state accountable to its new promises. South African paralegals, for example, now focus their efforts on assisting clients to access state provisions like social security, pension, and health care, or on enforcing new protections for women and workers.

Paralegals in the Philippines have played a central role in the implementation of post-Marcos laws on environment, agrarian reform, and labor – they educate communities about the laws, monitor compliance, and help clients to seek enforcement. Paralegals can provide representation in agrarian reform and labor tribunals, and some are deputized as community-based coast and forest guards. In some cases, paralegals were involved in lobbying for the laws they now help to implement.

In a review of literature on the relationship between citizen action and state services, Ringold and colleagues conclude that asymmetries in information and power are key barriers that limit citizen capacity to hold the state accountable to its positive commitments.Footnote 37 Paralegals aim to reduce both kinds of asymmetry.

Unfortunately, the journey from extractive to inclusive institutions is not linear. South Africa, the Philippines, Kenya, and Sierra Leone have all arguably zigzagged in recent years.Footnote 38 Paralegal groups have adapted their work accordingly. In the Philippines, in response to President Duterte’s “War on Drugs,” paralegals with the organization SALIGAN have re-focused their community education efforts on laws governing police searches and arrests.

Paralegals with the coalition Alternative Law Groups are planning to train communities on how to document extra-judicial killings, to collect evidence in the hope of future efforts to hold public and private actors accountable. Marlon Manuel, National Coordinator of Alternative Law Groups, said “we are more prepared to resist repression now because of our experience in the days of Marcos and what we learned from that period.”Footnote 39

2. Variation in Impact across Case Types, and the Relationship between Grassroots Experience and Systemic Change

The kind of value paralegals add varies across different types of cases. When people have disputes with other community members, rather than with the state or private firms, they generally have a wider choice of forums, including customary authorities like traditional courts and chiefs, state institutions like the police, and other actors who will mediate or arbitrate, like a religious leader or a school principal. Paralegals sometimes help community members to engage these various forums; in other cases, they mediate the disputes themselves.

The more functional and fair the existing forums are, it seems, the less important is the role of paralegals in cases that would go before them. In the Philippines, the local barangay justice system, which is a hybrid structure that combines traditional and formal elements – is reasonably accessible and accepted.Footnote 40 Likely as a result of this, paralegals in the Philippines focus comparatively less on intra-community disputes and more on efforts to hold government and private firms accountable.

In Indonesia, village heads resolve most intra-community disputes. Paralegals often advise people who are going before these village leaders. Berenshcot and Rinaldi tracked some cases in which advice from paralegals strengthened the ability of poor parties to argue for themselves, and to invoke the law in doing so. But in many other cases resolved by village heads, the paralegals seemed to have minimal impact, perhaps at best boosting a poor person’s confidence. In Indonesia, like in the Philippines, paralegals’ significance in intra-community disputes seemed to be lower when village heads were functioning well.

Paralegal intervention can be very valuable in intra-community disputes, on the other hand, when local institutions are likely to be systematically unfair. The rights of women is a prime example. There are paralegals who help women exercise their rights in relation to family and community members in every country we studied.

In Sierra Leone, child support, alimony, child custody, wife neglect, and rape/sexual abuse made up 43 percent of all cases handled by paralegals, but less than 10 percent of the cases we encountered in non-paralegal sites. All of these cases involved complaints by women against men. The Sierra Leone chapter infers that “women are bringing these cases more often to paralegals and less often to local authorities because of the bias of existing institutions.”

For cases that do not involve a serious crime, paralegals will often attempt mediation with the aim of reaching an agreement that respects women’s rights under law. If mediation fails, or if a violation is too serious for mediation to be appropriate (e.g., rape), paralegals help women seek a fair result from existing institutions.

In Liberia, a paralegal (locally called a community justice advisor), assisted a woman, Musu, whose boyfriend threw acid on her, severely burning her face and torso. The man was initially arrested, but the state dropped his case and released him, which led Musu to fear for her life. A paralegal educated Musu about criminal procedure and accompanied her in a meeting with the county attorney. Together they pressed for prosecution, and Musu offered to serve as a witness. The county attorney complied, and the man was re-apprehended and convicted. Chapman and Payne conclude in the Liberia chapter that “without the [paralegal’s] intervention, the case would likely have been forgotten, [and] Musu’s justice denied.”

The forward-looking implication of our findings on intra-community disputes is this: paralegals should avoid redundancy with existing institutions by focusing their work with respect to intra-community disputes on areas, like women’s rights, for which existing institutions are likely to be systematically unfair.

Researchers in all six countries found that paralegals have some of their greatest impact when dealing with disputes between people and the state, as in the infrastructure fund case we described from Indonesia, or disputes between people and private firms, as with the sand mining case from Kenya with which we opened the book. The Indonesia, Kenya, and Sierra Leone chapters recommend that paralegals in those countries place greater emphasis on such cases.

The stakes in state and corporate accountability cases are typically high, and the imbalance of power is great. Resolving them frequently involves engaging administrative institutions (like the PNPM administration in Indonesia, or the National Environmental Management Authority in Kenya), which do not require a lawyer but which are often opaque, intimidating, or corrupt. A paralegal can help people to understand the terrain, identify favorable laws and regulations, and find their way to a remedy.Footnote 41

Paralegals and their clients do not always win when they take on tough cases of any type. The solutions they do achieve are usually partial victories. By and large this is to be expected – if the cases are too easy, then paralegals wouldn’t be adding much value. But it is important that they can make enough progress to inspire hope. If remedies are completely out of reach, Franco, Soliman, and Cisnero point out in the Philippines chapter, “the cumulative effects” on communities “can be demoralization, demobilization, or a turn toward violence.”

In all three categories of cases – disputes with the state, disputes with firms, and disputes between citizens – paralegal casework provides a detailed picture of how people experience the law in practice. Organizations and the communities they serve can draw on that information to identify and advocate for systemic changes. In the Philippines, after a decade of working to implement the agrarian reform passed in 1988, paralegals and their clients were crucial in advocating for two extensions of the law – first for another ten years until 1998, and then again until 2014. Franco, Soliman, and Cisnero explain that “[t]he work of paralegals was instrumental in providing the much-needed evidence of the weaknesses and shortcomings of the law as crafted. For example, landowners in the coconut-producing areas used criminal statutes in order to circumvent the intent of the law, and this practice was corrected in subsequent legislation.”

By translating grassroots experience into nuanced calls for reform, paralegals and their clients can help shape the institutional landscapes they inhabit.

B. Recognition and Regulation

1. Paralegal Groups Have Sought, and Sometimes Won, Recognition within National Legal Aid Systems

In all six countries, as paralegal movements have matured, they have raised the question of their status vis-à-vis the state. Paralegals and paralegal organizations seek formal recognition for three reasons. First, recognition can bring greater legitimacy, and thereby make government officials and private actors more responsive to advocacy by paralegals.

Second, recognition can lead to public financing. Third, standards for who qualifies as a paralegal may improve the consistency of paralegal services and guard against fraud and abuse. On the other hand, state recognition and regulation also pose risks: too much state involvement might replace dynamism with rigidityFootnote 42 and curtail paralegals’ ability to hold the state accountable.Footnote 43

Segments of the private bar, meanwhile, often oppose recognition of community paralegals. These lawyers are typically concerned with maintaining their monopoly over legal services; as a result, they often only welcome paralegals who work as lawyers’ assistants. Legal empowerment groups respond that there is almost no overlap between the two spheres of practice because community paralegal clients are too poor to access lawyers.

Chapman and Payne write that “objections from many members of the bar miss a fundamental reality confronting many in Liberia: most individuals simply cannot engage lawyers for advice or assistance or access formal courts with legal and administrative issues. The fees and geographic factors are prohibitive.” Moreover, several of the methods community paralegals deploy, including mediation, organizing, and navigating administrative and traditional institutions, are outside lawyers’ core competence.

In Indonesia, Kenya, and Sierra Leone, legal empowerment organizations have overcome opposition from the bar and successfully advocated for legal aid legislation that recognizes community paralegals. The 2012 Sierra Leone Legal Aid Law establishes an independent Legal Aid Board and authorizes the Board to accredit legal aid providers, including civil society organizations and paralegals. The law calls for a paralegal in every chiefdom of the country.Footnote 44

The 2011 Indonesia Law on Legal Assistance also recognizes community paralegals. The law does not set up a separate board; rather, it mandates the Ministry of Law and Human Rights to directly accredit legal aid providers.Footnote 45 Paralegal proponents in Indonesia have therefore expressed concern as to whether accredited paralegals will be able to maintain their independence from government.Footnote 46

The 2016 Kenya Legal Aid Act recognizes paralegals, including community paralegals, so long as they are supervised by an advocate or an accredited legal aid organization. The Act establishes a national Legal Aid Service responsible, among other things, for coordinating, monitoring, and evaluating paralegals. The governing board for the Service includes a reserved seat for a representative elected by a joint forum of civil society legal aid providers. The Act establishes a legal aid fund to “meet the expenses incurred by legal aid providers,”Footnote 47 although details on how the fund will work in practice are still being negotiated as of this writing.

In South Africa, two bills that would have recognized paralegals – the Legal Practice Bill of 2002 and the Legal Services Charter of 2007 – stalled in parliament, in part because of opposition to paralegal recognition by the private bar.Footnote 48 The bar was particularly resistant to provisions that would have allowed paralegals to collect fees and to represent clients in low-level administrative courts. Dugard and Drage point out in the South Africa chapter that the lack of recognition, and in particular the failure to integrate community advice offices more fully with Legal Aid South Africa, creates challenges for sustainability and quality control.

In March 2015, South Africa established a Legal Practice Council through a new law, the Legal Aid South Africa Act. The Act requires the Council to make recommendations, within two years of its creation, regarding the statutory recognition of community paralegals.Footnote 49 Two national coalitions dedicated to community paralegals – the Association of Community Advice Offices in South Africa (ACAOSA) and the National Alliance for the Development of Community Advice Offices (NADCAO) – applauded the passage of the Act.Footnote 50

Where legal empowerment groups have managed to secure legislative recognition for community paralegals, they have tended to work in coalitions like NADCAO and ACAOSA, rather than as lone organizations acting in isolation. They have also cultivated champions within government. Advocates in Sierra Leone reached a turning point when they persuaded the attorney general to change his position from opposing paralegal recognition to embracing it. In Kenya, the Parliamentary Human Rights Association proved to be a vital ally. Immediately after a meeting with legal empowerment groups in 2015, association members reintroduced the legal aid bill that had been stuck since 2013. The bill passed by the end of the session.

2. The Challenges of Recognition within Legal Aid Systems, and Two Alternatives: Sectoral Departments and Local Governments

There are drawbacks to seeking recognition from national legal aid schemes. Because legal aid is traditionally the domain of lawyers, this avenue of recognition often runs directly into opposition from the bar.

Recognition within a legal aid scheme also poses budgetary challenges. Legal aid systems often lack the resources to meet their constitutional obligations to provide a defense counsel to people facing serious criminal charges.Footnote 51 Asking cash-strapped institutions to broaden their mandate can be like trying to squeeze juice out of dry limes.Footnote 52

As a result, some paralegal movements have sought recognition on a sector-specific basis, as a complement or an alternative to recognition by a national legal aid system. In the Philippines, for example, the Supreme Court objected to a component of an access to justice project that involved training community paralegals. The Court found that the project would constitute unlawful practice of law.

But despite this rejection by the judiciary, community paralegals have gained recognition from several sectoral departments. Paralegals can provide representation in agrarian reform tribunals (through the Department of Agrarian Reform Adjudication Board) and labor disputes (through the National Labor Relations Commission). Some are deputized as community-based forest guards (by the Department of the Environment and Natural Resources). The Department of Agrarian Reform has also provided financial support for the training of farmer paralegals.Footnote 53 Community paralegals are not part of a national legal aid scheme to date. But Supreme Court opposition did not crush the paralegal movement, in part because the movement found recognition elsewhere.

Paralegal groups have secured a sector-specific form of recognition in Sierra Leone as well. Government there was slow to constitute the Legal Aid Board after passage of the Legal Aid Law. As of this writing, the Board has not recognized or funded community paralegals, with the exception of a small pilot focused on pretrial detainees. In the meantime, legal empowerment groups have successfully advocated for recognition in the new National Land Policy for the role of paralegals in supporting communities in relation to investors.

The policy requires firms interested in leasing land to pay into a basket fund that will finance legal support via paralegals for landowning communities.Footnote 54 If implemented, this provision will create revenue for an urgent need. The Sierra Leone government is aggressively courting large-scale agriculture and mining investments as a way of restarting the economy after the Ebola epidemic. The investments often lead to gross exploitation, as with the case from Nimiyama that we described earlier. With basic legal support communities can defend themselves against outright land grabs, negotiate equitable terms if they do choose to welcome investment, and seek enforcement if those terms are violated.Footnote 55

In addition to sectoral recognition, another alternative to the national legal aid route is to make inroads with government at a local level. In South Africa, the Zola municipal government in Gauteng Province pays rent and utilities for its local community advice office; the Mpola municipality in Kwa Zulu Natal provides its local advice office with free space in the town hall. Other paralegals in South Africa have recognition from local traditional authorities: fifteen community advice offices in Kwa Zulu Natal are located in the offices of traditional courts.

In the Philippines some barangay (village-level) governments have similarly provided community paralegals with office space and operational expenses. Good relations with barangay officials can be of great value to paralegals, especially for addressing the rights of women and children. In those matters, barangay officials carry significant authority, including the power to issue protection orders.

But paralegal informants in the Philippines identified risks with this local government approach as well. Paralegals can become associated with the barangay officials that support them, and therefore go out of favor when those officials lose elections. While the supportive officials are in power, paralegals may find it difficult to oppose them in the event that they act illegally or unjustly.

Whether recognition flows from a national legal aid scheme, a sector-specific department like land or labor, or a local government, it is always a double-edged sword: the state can provide legitimacy and possibly resources, but it can also potentially constrain the autonomy of paralegal organizations.

There might be greater mission alignment with ombudsman offices and human rights commissions, both of which are explicitly designed to help citizens hold the state accountable. We did not observe affiliations between paralegal groups and such national accountability institutions in any of the six countries we studied, but it may be an avenue worth exploring. Overall, our impression is that community paralegals are not likely to ever outgrow the need to dance delicately between recognition and independence.

C. Funding

Community paralegal efforts cost money. Paralegals who work full time require a salary; those who serve their own village or their own membership association as volunteers require support from lawyers or more senior paralegals who earn a salary. There are also costs associated with training, office space, materials, transportation to reach clients and government offices, and litigation for a small percentage of cases.

The costs tend to be low. In Sierra Leone, the legal empowerment group NamatiFootnote 56 estimates that it would cost US$2 million per year to provide paralegal services throughout the country. That figure includes a small corps of lawyers to provide paralegals with supervision and support. To put that figure into context, US$2 million is three-tenths of a percent of the total 2013 national budget and 3 percent of what the Sierra Leone government allocated to health care that year.Footnote 57 Law and Development Partnership estimated costs for nationwide delivery of seventeen basic legal services programs, most of which included paralegals. The estimates ranged from US$0.1 to US$1.3 per capita in less developed countries, and from US$3 to US$6 per capita in highly developed countries.Footnote 58

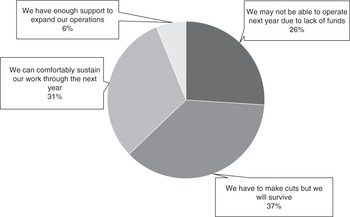

Despite relatively modest costs, paralegal groups in every country identified unstable funding as a key constraint.Footnote 59 This is consistent with data from the Global Legal Empowerment Network. When asked “How sustainable is your funding situation for the coming year?” in a 2017 member survey, 63 percent of respondents said either “we have to make cuts but we will survive” or “we may not be able to operate next year due to lack of funds.”Footnote 60

Figure 1.2 How sustainable is your funding situation for the coming year?.

The bulk of the funding that does exist in all six countries comes from international donors: foundations like the Atlantic Philanthropies and the Open Society Foundation, bilateral development agencies like Britain’s Department for International Development, and multilateral institutions like the UN Development Programme.

1. Seeking a Greater Share of International Development Assistance

Paralegal groups are keen to expand investment from development agencies. Official development assistance amounts to more than US$130 billion per year.Footnote 61 Only a small share of that is dedicated to governance and the rule of law,Footnote 62 and the vast majority of what is invested in those areas goes to support state institutions rather than civil society organizations.Footnote 63 The Millennium Development Goals, which were adopted in 2000 and were influential on development spending and policy, did not mention justice, fairness, or accountability at all.

Many paralegal groups campaigned for incorporation of access to justice in the 2030 Sustainable Goals, which were adopted in 2015 after the Millennium Development Goals expired. They argued that legal empowerment is essential to the mission of poverty alleviation – people cannot improve their lives if they cannot exercise basic rights.Footnote 64

Despite significant opposition from countries inclined to define development in exclusively technical, economic terms, that campaign was ultimately successful: Goal 16 in the new framework commits to “access to justice for all.”Footnote 65 Legal empowerment groups now hope to translate that nominal commitment into increased financing.Footnote 66

2. Efforts to Diversify Revenue: Domestic Government, Social Enterprise, and Community Contributions

Sole reliance on development aid, or any other single source, leaves paralegal efforts vulnerable to interference or political whim. A resilient, independent paralegal movement requires diverse support. As discussed earlier, groups in all six countries in the study are seeking some degree of financing from domestic governments, via national legal aid schemes, sectoral departments like land and labor, or local governments.

In addition to those, social enterprise and community contributions offer two other channels for diversifying revenue. The NGO BRAC, for example, earns more than 60 percent of its revenue from microfinance and from social enterprises like rural computer learning centers.Footnote 67 The work of BRAC’s 6,000 “barefoot lawyers” is primarily donor-funded, but BRAC’s business revenue does subsidize the legal empowerment efforts, in part by sustaining programs if there is a gap between grants. On a smaller scale, one community paralegal office in Orange Farm Township, South Africa, pays its staff with revenue from a recycling business that it runs.Footnote 68

Community contributions can be in cash or in kind. Some legal aid laws, including the ones in Kenya and Sierra Leone, prohibit charging fees for paralegal services.Footnote 69 But none bars collective contributions or voluntary individual donations. In Sierra Leone, all the chiefdoms where the legal empowerment group Timap for Justice works have offered land where Timap can build permanent offices. In the Philippines and Indonesia, some trade unions and farmers’ associations use membership dues to defray paralegal expenses.

Many paralegal offices in South Africa hold community fundraisers like fish barbecues and car washes. The Social Change Assistance Trust incentivizes this local fundraising by providing five rand of donor funding for every rand raised from the community. By itself, community financing is often able to cover only a small proportion of the total cost. But it has the additional benefit of increasing the accountability of paralegals to their constituents.

Overall, the challenge of securing diverse revenue is an existential one for paralegal movements – large-scale, long-term impact is difficult to achieve without it.

VI. Society and Culture

Social dynamics – of power and inequality, of cohesion and conflict – shape paralegal efforts as much as public institutions.

A. Paralegal Groups Both Respond to Demand and Try to Stimulate It

Social conditions shape the demand for paralegal services. The civil wars in Sierra Leone and Liberia, for example, caused severe disruption: some people fought, some fled, and some stayed behind; some people survived and some did not. That disruption, along with poverty, urbanization, and other factors, has led to particularly unstable family arrangements.Footnote 70 Instability in the family, in turn, may be part of why child support cases make up a large proportion of paralegal dockets in both places.

In South Africa, Dugard and Drage find that the most common issues paralegals address are domestic violence and access to social grants. They observe that the prevalence of those cases flows naturally from central features of contemporary South African society. “These areas of work relate to two of the most serious remaining fault lines in South Africa: endemic violence in the home and structural unemployment, meaning that a very high proportion of South Africans relies on social grants to survive.”

But express demand may not reflect perfectly the actual experience of injustice across society. For many people in Sierra Leone and Liberia the state is a remote presence, one that has not offered much over the years. Rural people in those countries often conceive of state failures as facts of life rather than rights violations for which a remedy is worth pursuing.Footnote 71

Berenschot and Rinaldi note a related tendency, associated with the repressive New Order regime but lingering among many Indonesians still, to eschew confrontation with authorities, to make polite requests but avoid formal channels for redress.

Given the way culture can limit people’s ability to conceive of and act on breaches of rights, some paralegal groups depart from the tradition of taking priorities from the cases people bring. Instead, these organizations adopt a more proactive stance toward the kinds of injustices their constituents might not conceive of as such, like failures in the delivery of state services.Footnote 72 The paralegals educate people about state policies, and proactively encourage them to take action against violations. Berenschot and Rinaldi observe – cautiously, for their sample of relevant cases was small – that the presence of paralegals can lead people to complain about problems they might otherwise ignore, and to “press authorities in a more straightforward manner.”

B. Paralegals and Social Movements

When demand for change does gain momentum, and paralegals are a part of larger social movements, they are more likely to succeed in having an impact on not just local state actors but large-scale policy as well. Paralegals in the Philippines, for example, were not alone in pushing for implementation and extension of agrarian reform legislation. They were part of a broad coalition of peasant organizations and public interest lawyers.

In South Africa, paralegals were intimately tied to the antiapartheid movement. After the transition to democracy, individual advice offices were no longer united by a single national struggle. NADCAO and ACAOSA were founded in part as a response to fragmentation. Those coalitions aim to build greater unity among community advice offices, and to connect paralegals with broader movements for justice. The coalition of organizations scaling up paralegal services in Sierra Leone has similar aspirations.

VII. Paralegal Organizations

The success of paralegal efforts turns in large part on the skill and commitment of individual paralegals. The best paralegals we observed were able to help clients make improbable strides toward justice, even when state institutions were brutal or dysfunctional.

But not all paralegals are the same. In the worst case scenario, paralegals could use their knowledge and status to exploit others. We did encounter one example of abuse in our six studies. A paralegal in Kenya collected money from clients, saying he needed to pay an attorney to help with their dispute. Instead he kept the money for himself. Another paralegal discovered what happened and confronted him, but the offending paralegal refused to return the money until he was arrested and summoned to court.

There are many shades between the dynamism of the best paralegals and the outright corruption of that paralegal in Kenya. Paralegal organizations have a vital role in preventing abuse, ensuring consistent quality, and nurturing excellence. We begin this section by describing five qualities we observed in effective paralegals. We then discuss five ways in which organizations try to foster those qualities in the paralegal cadres with whom they work.

A. Five Qualities of Effective Paralegals

1. Trusted by Constituents

Successful paralegals earn the trust of the communities they serve. Dugard and Drage take the title of their chapter from Greg Erasmus, former coordinator of NADCAO, who said, “Simply ask where and to whom do the people take their issues? That person is the paralegal.” Erasmus’ definition holds when communities have confidence in a paralegal’s character and ability. Without that trust a paralegal will not have work.

2. Focus on Empowerment

At the outset of our research, we identified an emphasis on empowerment as one of the key potential advantages of paralegals over a conventional legal aid approach. Not all the paralegals we observed demonstrated this value. Dugard and Drage found that some paralegals “failed to explain each step of the process to the client, meaning that the client would probably have to come to the paralegal if the same or similar problem arose again.”

But the most effective paralegals served as educators, demystifying law and equipping people to advocate for themselves. In Sierra Leone and Liberia, as mentioned earlier, we found that paralegal clients had greater knowledge of national law than those who had not worked with paralegals.

At their best, paralegals help people journey from powerlessness to hope. In Kenya, a community leader in Western Province said that since paralegals had begun to operate, “Women now know their rights … the paralegals have encouraged them to embrace and live these rights.” A man who received help from a paralegal in Indonesia spoke of what he learned from his case this way: “Our neighbors were surprised that we could win against powerful people. We are an example for poor people. If we are enlightened, we do not always have to be the victim; we can fight.”

3. Dogged, Creative Problem Solving

To help their clients win against powerful interests, and to achieve fair results from dysfunctional institutions, paralegals need to be persistent and resourceful. Berenschot and Rinaldi describe the best paralegals they observed in Indonesia as possessing “savoir faire,” and as pragmatically blending legal action with mediation, advocacy, and community organizing in order to reach a solution. Dugard and Drage observed in paralegals “an extraordinary capacity to go the extra mile for clients” and a commitment to “creating authentic, lived solutions at the grassroots level.”

4. Strong Relationships with Local Institutions

Success in problem solving depends in turn on constructive relationships with local authorities. Moy finds in the Kenya chapter that “[t]he success of paralegal efforts often hinged on the quality of their relationships with principal institutional actors and local leaders, including police, local administrative and other government officials, prison authorities, councilors, and chiefs.”

She quotes a local official in Eastern Province of Kenya, who said that “[t]he fact that the [paralegal] office is next to mine should tell you more about our relationship. Us delegating peace and reconciliation to them speaks volumes … It is the biggest resource center in the district … They have the legal knowledge while we have the administrative capability. We even seek advice there.”

In South Africa, officials similarly demonstrate confidence in paralegals by referring cases to them. In 2010, 38 percent of cases handled by paralegals with the Center for Criminal Justice came from state institutions like the police and the social welfare department.

Paralegals sometimes need to challenge local officials or hold them accountable for abuse, and so the relationships are not straightforward.Footnote 73 But the best paralegals find spaces for constructive engagement.

5. Connected to a Vertical Network

Not all problems can be solved locally. The most effective paralegals are embedded in vertical networks that can help them engage higher levels of authority when necessary – state, national, and sometimes international. With the help of a network, paralegals can engage strategically across a wide range of institutions, including administrative agencies, parliaments, ombudsman offices, courts, and corporations.Footnote 74

When paralegals and their clients achieved (partial) redress for abuses by mining companies in Sierra Leone, for example, progress was due in part to key moments in which the lawyer who supervised the paralegals helped advocate with either the Ministry of Mines in Freetown or the mining company directly.

Berenschot and Rinaldi observe that links to farmers’ associations and labor unions are useful, and that “support from city-based lawyers signals to possible clients that a paralegal might actually succeed in bringing a case to court.” Some informants told Franco, Soliman, and Cisnero that in the Philippines, “without lawyers to train and guide paralegals, there can be no paralegal movement.”

Not only do paralegals need a vertical network to succeed in specific tough cases, it is through a network that paralegals and clients can come together to advocate for large-scale systemic changes, like extension of agrarian reform in the Philippines or improvements to land policy in Sierra Leone.

B. Five Organizational Approaches to Ensure Effectiveness

Organizational choices shape whether, and how much, a paralegal cadre attains the dimensions of excellence we’ve just described. Looking across the studies in this volume, five aspects of organizational practice stand out as most important.

1. Recruitment and Selection

As with most endeavors, choosing the right people for the job is crucial. In Indonesia, organizations selected paralegals using three criteria: “a) trusted by the community; b) actively involved in community organization or activities; [and] c) having organizational, advocacy or legal aid experience.” The coalition of paralegal groups in Sierra Leone goes a bit further, by applying four criteria: (a) trusted by the community; (b) demonstrated commitment to the common good; (c) decent writing skills; and (d) strong analytical and problem-solving ability.

Sierra Leonean groups assess the first two – which are akin to the criteria from Indonesia – through interviews and reference checks. They assess the latter two through a written exercise, often along the lines of “here is an example of an actual justice problem – how would you go about helping your clients?”

An environmental justice paralegal in the Philippines emphasized another specific quality – he said that a paralegal must have “the courage to defend the rights of the people.”

Some paralegals in South Africa and Liberia are elected by the communities they serve. This method has the benefit of establishing the direct accountability of paralegals to their constituents; it is most feasible when the paralegal is serving a relatively small population. Organizations can combine meritocratic and democratic selection by asking the community to elect several candidates who then apply in a competitive process, or by doing the reverse – selecting finalists through a competitive process and then subjecting those finalists to a community vote.

Overall, based on qualitative findings across the studies, we believe that greater stringency in paralegal selection would help to address the weaknesses identified in paralegal performance.

2. Payment

On the surface, it seemed there was a split among the countries we studied with respect to payment. In the Philippines, Indonesia, and Kenya, the majority of paralegals are volunteers who have other occupations. They typically receive stipends for their transport costs and other expenses but not salaries. In South Africa, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, most paralegals work full time and are paid modest salaries.

But this difference turns out to stem in large part from the way the term paralegal is applied. The paid paralegals in South Africa, Sierra Leone, and Liberia tend to serve larger populations – a chiefdom in Sierra Leone, a district in Liberia – and they often interact with village-level liaisons who are volunteers. The volunteers referred to as paralegals in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Kenya, on the other hand, often serve a single village or a small membership group (e.g., a local farmers’ association). The volunteers are typically supported in turn by paid NGO staff who cover a larger area, like the “posko facilitators” in Indonesia. Indonesian posko facilitators play a similar role to that of paralegals in Sierra Leone. The staff structure can be roughly similar, then, with the term paralegal applied to different rungs.

Moy reports that in Kenya, “most interviewees felt that truly effective and sustainable paralegal work requires financial support in some form.” Dugard and Drage conclude that “community-based paralegals are undoubtedly underpaid for their work” and that low salaries increase “the turnover in staff, leading to a brain drain in the [paralegal] sector and the loss of capacity as paralegals look for employment elsewhere to mitigate their own hardship.”

Looking across the six studies, we agree with Moy, Dugard, and Drage. Local-level volunteers play a crucial role in paralegal efforts everywhere. But high-quality, rigorous paralegal work that takes on complex injustices requires a layer of staff who earn a living wage. Whether the volunteers or the paid staff or both are given the name paralegals may not matter intrinsically – that choice is likely shaped in part by organizational practice and in part by regulation. Given limited resources, in a trade-off between a smaller number of people receiving a living wage and a larger number receiving significantly less, our qualitative findings suggest the former is preferable.Footnote 75

3. Support, Supervision, and the Importance of Case Data

All organizations we examined provide training to paralegals at the outset. But the studies suggest that paralegal effectiveness depends less on the initial orientation and more on the provision of ongoing supervision and support. It is through a continuous relationship with paralegals that organizations can ensure consistent quality, learn and improve over time, and integrate paralegals into a vertical network for taking on powerful interests.

Support and supervision are structured differently in different places. In the Philippines, the most common arrangement is for paralegals to be members of grassroots organizations, often labor unions or farmers’ associations. National or regional legal empowerment groups, like Saligan, which focuses on labor rights, and Kaisahan, which focuses on agrarian issues, provide paralegals with ongoing training and support. In South Africa, most community advice offices are independent organizations in and of themselves. The paralegals receive support from umbrella networks they belong to, such as ACAOSA, NADCAO, and the Community Law and Rural Development Center in Kwazulu Natal.

In Sierra Leone and Liberia, the paralegals, “lead paralegals,” and at least one lawyer often work in the same organization, like Timap for Justice in Sierra Leone and the Catholic Justice and Peace Commission in Liberia. In Kenya, Moy identifies a range of approaches and concludes that “greater levels of legal support will on the whole strengthen the long-term morale, commitment, and performance of paralegals.”

Rigorous tracking of case information is essential for effective supervision and support. If paralegals keep good case records, senior staff can review how a case is handled, learn from the paralegal’s work, and provide feedback or suggestions on how to take a case forward. The aggregation of case-level data into a central database, moreover, allows for learning across the cadre. Organizations can draw on aggregate information to identify common problems that are arising, or innovations worth replicating, or specific paralegals who are having trouble.

Aggregate data from cases also provides nuanced evidence from which to identify and advocate for reforms to laws and institutions. Without it, organizations may miss the opportunity to translate their grassroots experience into proposals for systemic change.

Not all the organizations we studied had systems for tracking and aggregating case data. Even the ones that did – in South Africa, Indonesia, Kenya, Sierra Leone, and Liberia – reported challenges in operating these systems smoothly. Paralegals make errors or omissions in filling case-tracking forms, for example, and there are often delays in data entry, aggregation, and analysis.

This challenge is reflective of a larger dynamic with paralegal efforts. Most paralegal organizations grew organically out of social movements, like people power in the Philippines and the antiapartheid movement in South Africa. Many paralegals conceive of their work more as activism than service delivery. They often focus on responding to immediate crises rather than building organizations. But if paralegal groups are to reach their full potential, they need to invest in the systems that make consistent excellence possible.

4. Accountability to Communities

Paralegals regularly make subjective judgments about justice in the course of their work. They choose which cases to take on and, for citizen versus citizen cases, they often take the side of one community member in a dispute against another.

How do we know those choices will be judicious and that the community’s trust will not be abused? In many places, there is a class of people who offer themselves as legal intermediaries – in the Philippines, they are called abogadillos, literally “small lawyers,” in Indonesia, makelar kasus, in Sierra Leone, blackman lawya. These intermediaries often charge exploitative fees for their services. A paralegal from Quezon Province in the Philippines told of an abogadillo charging 5,000 pesos (around US$120) to secure a document from the Department of Agrarian Reform that was officially available for free.

There is a risk that paralegals similarly use their knowledge and reputation to exploit others, as with the one example we observed of a paralegal defrauding clients in Kenya. Support and supervision from paralegal organizations is crucial for preventing abuse, as we’ve just discussed.

Equally important is the accountability of paralegals to the people they serve. Dugard and Drage argue that “embeddedness in communities,” the fact that paralegals live among their clients, is one of the strongest virtues of South African community advice offices. This was a common observation across all six studies and indeed is one of the key arguments in favor of a paralegal approach. But as the phenomenon of abogadillos and their counterparts suggests, embeddedness does not guarantee an alignment with the interests of community members.Footnote 76

Many organizations seek to establish formal structures to ensure accountability. The Social Change Assistance Trust in South Africa requires advice offices it supports to be governed by management committees that include community representatives. The committees in turn must regularly hold open community meetings to review performance. In the Philippines, paralegals who are a part of membership organizations like farmers’ associations and trade unions are answerable to their fellow members. In Sierra Leone, Timap for Justice has community oversight boards in every chiefdom; the boards are charged with ensuring that the paralegals are serving the constituent community effectively.Footnote 77

In addition to providing a channel for accountability, these structures resonate with the ideal of empowerment. Ultimately the work of exercising rights – and the paralegal who can help – are in the people’s hands.

5. Specialization and Coordination across Paralegal Efforts