1. The Variants

If one asks a grammarian what she or he takes the (main) predicate of a sentence such as Ian has revised his paper twice to be, the response one is likely to receive is difficult to predict.Footnote 1 The bolded strings in the next lines illustrate five of the many possible answers one might receive:

The understanding of predicates in (1a–c) has the longest tradition, being associated with the propositional logic of Aristotle (384–322 BC) (cf. Seuren Reference Seuren1998: 121–125). The understanding of predicates in (1d–e) also enjoys a significant tradition, but reaching back just to the predicate logic of Gottlob Frege (1848–1925) (cf. Seuren Reference Seuren1998: 338–339). All five variants are encountered in the literature on semantics and syntax, and in grammar books more generally. Variants 1 and 4 are the most frequently occurring, but Variants 2, 3, and 5 also have their adherents.

The Aristotelian understanding of predicates shown as Variant 1 views everything except the subject as the predicate; the predicate serves to assert something about the subject. Variant 2 excludes the auxiliary has from the predicate because has contributes functional meaning only and hence cannot be construed as influencing semantic selection of the subject. Variant 3 excludes adjuncts from the predicate, reducing the predicate down to just the content verb and its complement(s). On the Fregean understanding, in contrast, predicates are properties or n‑ary relations, taking zero to four arguments in order to express a complete idea. Variant 4 construes just the content verb revised – or just the lexical-semantic core revise of the content verb – as the predicate, whereas Variant 5 includes the function verb has in the predicate with revised, the two verbs together serving to express the predicate analytically.

This article pursues three main goals: 1) it surveys textbooks and current views among linguists concerning predicates, 2) it scrutinizes aspects of all five variants shown here, and most importantly, 3) it advocates for Variant 5. The particular argument developed below in favor of Variant 5 is that, given a dependency grammar (DG) approach to the syntax of natural languages, Variant 5 predicates receive a concrete expression in sentence structures. In particular, predicates need not be constituents,Footnote 2 but rather they are subtrees; the operative term used to denote these subtrees is catenae – singular catena [kəˈti:nə], Latin for ‘chain’ (see O’Grady Reference O’Grady1998; Osborne Reference Osborne2005, Reference Osborne2019: 106–112; Osborne & Groß Reference Osborne and Groß2012, Osborne et al. Reference Osborne, Putnam and Groß2012).

This article is organized as follows. Section 2 surveys textbook wisdom and current views among linguists concerning predicates. Section 3 scrutinizes the five variants, pointing out problems associated with Variants 1–4; it focuses in particular on the status of finite VP in English as, perhaps surprisingly, a non-constituent string.Footnote 3 Section 4 turns to the DG understanding of predicates along the lines of Variant 5, defining predicates and predications as catenae in sentence structures. Sections 5–7 motivate the approach: Section 5 in terms of the synthetic vs. analytic manifestations of predicates, Section 6 in terms of entailment patterns, and Section 7 in terms of pronoun resolution. Section 8 concludes the article.

Finally, the use of informant judgments to support claims about (un)grammaticality and (un)acceptability should be mentioned. Many of the perhaps controversial example sentences below were presented to informants in the crowdsourcing service Amazon Mechanical Turk, the intent being to determine where acceptability actually lies. When testing for the general grammaticality of example sentences, a four-point scale from 1 (perfectly grammatical) to 4 (quite ungrammatical) was used; when testing for entailment, a three-point scale from 1 (entailment present) to 3 (entailment absent) was used; and when testing for pronoun resolution, a four-point scale from 1 (coreference easily possible) to 4 (coreference clearly impossible) was again used.

The next three example pairs illustrate this use of informant judgments:

Concerning the numbers on the right, the number before the slash each time is the number of informants that judged the sentence, and the number after the slash is the average score the sentence received on the mentioned scale, either 1–4 or 1–3.

The low score of 1.29 (scale 1–4) for sentence (2a) indicates that it is perfectly grammatical, and the much higher score of 2.76 for sentence (2b) indicates that it is grammatically strongly marginal. In a similar vein, the low score of 1.00 (scale 1–3), for example (3a), indicates that the sentence The anarchist assassinated the emperor entails the sentence The emperor is dead, and the relatively high score of 2.47 for example (3b) indicates that the sentence The emperor is dead does not entail the sentence The anarchist assassinated the emperor. Finally, the low score of 1.47 (scale 1–4) for sentence (4a) indicates that the sentence is grammatical and that Susan and herself are coreferential, and the high score of 3.29 for sentence (4b) indicates that Susan and her cannot be coreferential. The inclusion of such informant scores guards against confirmation bias, and it allows the account here to challenge inaccurate acceptability judgments in the literature and to perceive with confidence relatively minor shifts in acceptability. The appendix provides more information about the data collection project.

2. Surveys

The next three sections survey textbook wisdom and current views among linguists concerning predicates and predicators.

2.1. Survey of textbooks

In order to determine just how the predicate concept is understood and used in the study of grammar, more than 60 textbooks on semantics, syntax, and grammar were surveyed. Table 1 summarizes the results of this survey. Variant 4 is the most commonly encountered among the texts surveyed, followed by Variant 1. Variants 2, 3, and 5 are encountered much less frequently.

Table 1. Textbooks acknowledging predicates

There are a couple of noteworthy points in Table 1. Firstly, some textbook authors consciously employ the predicate concept in more than one way (e.g. Allerton Reference Allerton1979: 184–185, 259–260; Borsley Reference Borsley1991: 78–85, 104–105; Huddleston & Pullum Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 226, 252; Tallerman Reference Tallerman2005: 36–37, 68–69; Ouhalla Reference Ouhalla1994: 45, 126–127; Dixon Reference Dixon2010: 78–79 – concerning the latter, Dixon prefers the Fregean understanding of predicates, designating those that assume the Aristotelian predicate as ‘binarists’). Other authors seem to use the concept flexibly without explicitly acknowledging the inconsistency in use (e.g. Cowper Reference Cowper1992: 54, 67; van der Elst & Habermann Reference van der Elst and Habermann1997: 13, 39, 53, 56, 58; Portner Reference Portner2005: 31–33, 50; Kim & Sells Reference Kim and Sells2008: 35–36, 67–68). Yet other authors – authors not listed in Table 1 – choose to avoid the predicate concept (almost) entirely insofar as the term predicate does not appear in the book’s index (e.g. Radford Reference Radford1988; Eggins Reference Eggins1994; Fabb Reference Fabb1994; Sag et al. Reference Sag, Wasow and Bender2003; Haegeman Reference Haegeman2006; Payne Reference Payne2006; Miller Reference Miller2011; Sobin Reference Sobin2011). The reason these authors choose to avoid acknowledging predicates may be awareness of the overly flexible and at times contradictory manner in which the term is employed in grammar studies in general.

Concerning Variants 2 and 3, only a couple of authors employ the predicate concept in a way that allows classification as those variants. Haegeman and Gueron’s (Reference Haegeman and Guéron1999: 22, 40, 71, 77) and Culicover’s (Reference Culicover2009: 67, 299) uses of the predicate notion qualify as Variant 2 based mainly on their decision to exclude the copula from the predicate. Haegeman and Gueron (Reference Haegeman and Guéron1999: 71) state, for instance, that in the sentence John is rather proud of the result, the predicate is rather proud of the result to the exclusion of is. Similarly, Culicover (Reference Culicover2009: 299) states that the predicate in the simple sentence Kim is hungry is hungry alone, to the exclusion of is. Extending this approach to other auxiliary verbs, Variant 2 can claim the advantage that the predicate is consistent in English regardless of whether subject-auxiliary inversion is or is not present.

Concerning Variant 3, Aarts and Aarts (Reference Aarts and Aarts1982: 127–136) and Herbst and Schüller (Reference Herbst and Schüller2008: 20–21, 163–167) clearly pursue that understanding of predicates. Aarts and Aarts produce a number of example sentences in which one or more post-verbal adjuncts are shown as being excluded from the predicate (e.g. Frank left his wife last week, p. 128), and the same is true of Herbst and Schüller (e.g. I bought this hat at Heathrow this morning, p. 20).

Most of the books surveyed and listed in Table 1 are textbooks, which means they do not concentrate on the theory of predicates and predication. There are, though, of course, works that do focus on the theory of predicates. Worth mentioning in this regard are the monograph-length accounts of predicates by Napoli (Reference Napoli1989), Ackerman and Webelhuth (Reference Ackerman and Webelhuth1998), and Rothstein (Reference Rothstein2004). Interestingly, Rothstein (Reference Rothstein2004) pursues a decidedly Aristotelian understanding of predicates, but Napoli and Ackerman and Webelhuth pursue a Fregean approach, but one that is, perhaps surprisingly, more along the lines of Variant 5 than Variant 4.

2.2. Predicators

Some authors seek to overcome the difficulty associated with the competing and contradictory senses of the term predicate by acknowledging predicators. These authors tend to employ the term predicate to denote the Aristotelian predicate and the term predicator to denote the Fregean predicate. This might seem like an optimal solution to the inconsistent and contradictory use of terminology. However, scrutiny reveals that the use of the term predicator also varies. Many authors use it more in the sense of Variant 4 predicates above, and yet others in the sense of Variant 5 predicates.

Table 2 lists texts that employ the term predicator. The authors listed in Table 2 seem to agree that only verbs can be predicators – although they are not explicit in the area. Thus when the copula is present, it alone is the predicator, as shown next:

Table 2. Textbooks acknowledging predicators

Variant 4 and Variant 5 are in agreement concerning the simple copular sentence Mike is excited, the predicator being is alone. They disagree, though, when two or more verbs are present, as in the b-sentences.

The DG understanding of predicates developed below is, as stated above, broadly in line with Variant 5. However, the term predicator is not employed below for concrete reasons. Given the DG approach to syntactic structures assumed, the possibility of acknowledging the Aristotelian predicate does not arise, hence the predicator notion does not stand to disambiguate the approach to predicates. More importantly, the understanding of Variant 5 predicates developed below is distinct from the predicators just sketched with examples (5)–(6). In particular, the DG predicates below reach down from the root word of the sentence to include any predicative expression that is present. Hence, the DG predicate in the sentence Mike is excited is is excited rather than just is.

2.3. An email survey

In order to further determine how the predicate notion is understood and employed in linguistics, an email survey was conducted. Linguists in Europe and North America received the next email message; 39 responses were collected:

What qualifies as a predicate for you (off the top of your head)? One of my current research projects is the predicate concept in modern syntax and grammar. This message is simply one instance of me probing to determine how predicates are understood in our broad field in general. Consider the following analyses of the main predicate:

If you are asked to make a concrete statement about the main predicate in this sentence, would you say that it is (or corresponds to) the bolded material in (1a), (1b), or (1c)? Or would you answer in some other way? Comments concerning your answer would be welcome.

Note that Variant 2 and Variant 3 from the introduction are not represented in the options given in the question here. Awareness of those variants arose after sending out the original email queries. Note as well that the sentence Frank has written a long book does not contain an adverbial phrase of any sort, rendering answers along the lines of Variant 3 especially unlikely.

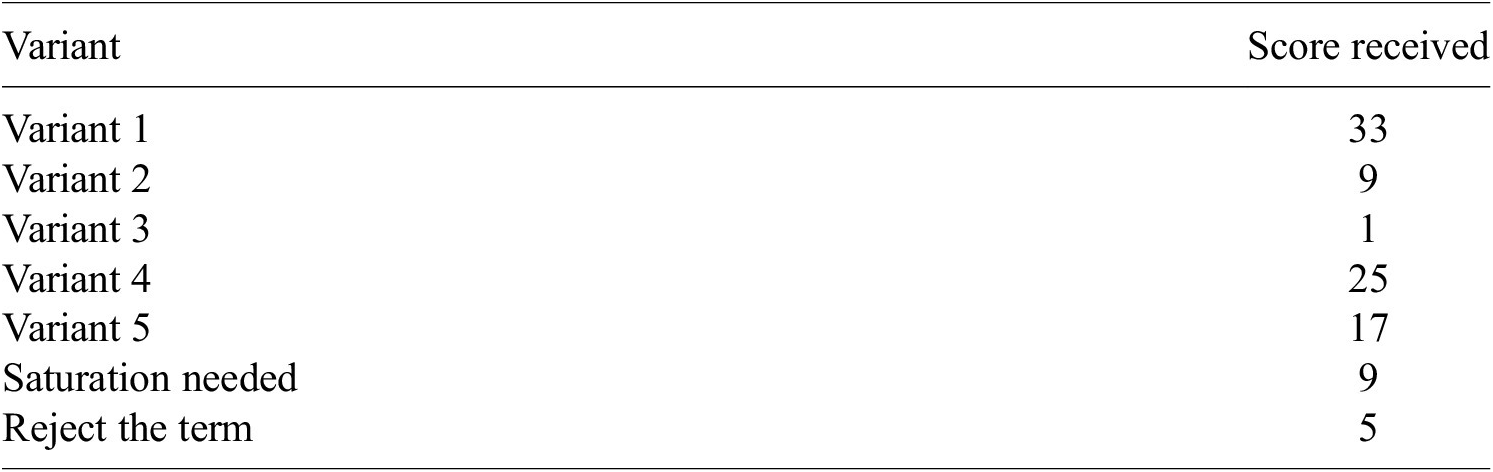

Many of the responses received acknowledged that the term predicate is polysemous. For this reason, a particular scoring procedure was used to assess the responses. When a respondent chose only one of the variants or expressed a preference for one of the variants over the others, that variant received 2 points, and secondary choices received 1 point (each). Table 3 summarizes the results of the survey. Variant 1 received the highest score with 33, followed by Variant 4 with 25, and then Variant 5 with 17. A handful of respondents expressed a particularly broad understanding of predicates, one in which a predicate is any linguistic expression in need of saturation, and yet a couple of other respondents reject the term predicate entirely, avoiding it in their works.

Table 3. Scores received by the variants of the predicate notion in email survey

There are a number of noteworthy points in the responses. There were three linguists who reject the term predicate outright and hence tend to avoid it. Interestingly, these linguists are DG grammarians, and the reason they avoid the term is at least in part because they reject the subject-predicate division of the clause associated with the Aristotelian predicate. Dependency syntax of course rejects the binary division, opting for verb centrality instead (cf. Tesnière Reference Tesnière1959 [Reference Tesnière, Osborne and Kahane2014: 98–100]). The handful of linguists who produced a response distinct from Variants 1–5 emphasized a more general understanding of predicates, whereby a predicate is any linguistic expression that is in need of saturation. Concerning Variant 5, the respondents who chose it tend to be linguists in Europe; four of them cited the school grammar they learned in their primary education. Concerning those linguists who produced a response along the lines of Variant 2 or Variant 4, an important qualification is necessary: a couple of them expressed the view that predicates are lexical-semantic entities instead of syntactic ones; these linguists hence view the main predicate of the sentence Frank has written a long book as simply write instead of as written or has written.

Some of the respondents also gave a reason as to why they reject one or the other variant. Concerning Variant 5, three respondents stated that they reject it at least in part because the two verbs do not form a constituent together in the syntax they assume and hence cannot be assigned meaning. These linguists are, namely, building on the assumption encountered among formal semanticists that there is necessarily a one-to-one mapping of semantic units to syntactic units, and that constituents qualify as syntactic units only if they can be assigned meaning. The DG approach to predicates below is quite contrary to this restrictive account. One-to-one mapping of semantic to syntactic units can still be assumed, but the relevant syntactic units are catenae rather than constituents.

Finally, a number of the respondents stated that the predicate notion is pre-theoretical or simply vague and hence likely to be construed in varied and imprecise ways. These respondents then tended to emphasize the importance of offering clear definitions in one’s theory. In this light, one linguist provided the following comment:

It’s a mess. Like most syntactic terminology. And we’ll never make it not a mess, so recognizing the mess is important but then being clear about what your theory does in terms of accounting for the phenomena we pretheoretically think are somehow connected becomes the crucial thing…I don’t believe in definitions outside a theoretical framework. (David Adger, email correspondence)

It is with this point in mind that the catena-based definition of predicate is presented below in Section 4.2.

3. Scrutiny

The next four sections scrutinize aspects of the five variants. Variants 1–3 are rejected mainly due to the absence of syntactic evidence supporting the existence of finite VP as a constituent, and Variant 4 is rejected because of its inability to acknowledge non-constituent predicates in syntax. Variant 5 is deemed the most promising because it consciously abandons the expectation that predicates be syntactic constituents, allowing the word combinations of analytically expressed predicates to be acknowledged despite the fact that these combinations do not form constituents in sentence structures.

3.1. Variants 1–3

The predicates of Variants 1–3 have been characterized above as ‘Aristotelian’. They do have something important in common that motivates this designation for all three. This common trait is that the three completely overlap in simple sentences such as John visited Mary, where there is no auxiliary verb and no adjunct present. In such a case, Variants 1–3 agree that the predicate is visited Mary. In this respect, motivating the Aristotelian predicate revolves primarily around the semantic and syntactic legitimacy of the finite VP constituent. There are two main ways of motivating the existence of finite VP as the predicate: the one is pragmatic in terms of ‘aboutness’ and the other is in terms of syntactic constituency. This section and the next two examine and refute these motivations.

Concerning aboutness, clauses are deemed to assert something about something, the former ‘something’ being the subject, and the latter ‘something’ being the predicate. Thus if one can demonstrate that sentences always assert something about the pre-verbal constituent in simple declarative sentences, then at least for such sentences, finite VP is motivated as the predicate. This pragmatic approach to motivating the existence of finite VP predicates is, though, not convincing, for it is easily possible to produce sentences in English (and most if not all other languages) in which the sentence as a whole is deemed to be more about what looks to be an object rather than about the subject, e.g.

These sentences are arguably more about Mary than about Everyone, It, or It. Thus, if aboutness is the criterion that identifies subjects, these sentences are such that what is standardly viewed as the object (or predicative nominal) would have to be completely reassessed and designated as the subject instead.

A similar point is valid for formal semantic approaches to predicates in terms of truth values. There is no a priori requirement that predicates be manifest as constituents in sentence structures. The logical analysis of sentence meaning is easily capable of abstracting over any position in the sentence structure at hand, a fact frequently pointed out in the literature (e.g. Strawson 1970: 110; Napoli Reference Napoli1989: 7; Ackerman & Webelhuth Reference Ackerman and Webelhuth1998: 9; Rothstein Reference Rothstein2004: 2). The point is illustrated next in terms of lambda abstraction, applied to the various positions in an example sentence discussed by Rothstein (Reference Rothstein2004: 2):

This ability to abstract over any of the four indicated positions in the sentence means that any one of the indicated four word combinations in lines (8a–d) can be construed as a one-place predicate, one that delivers a truth value when converted by the missing argument.

Most formal semanticist do not, though, choose to understand predicates in such a manner. They instead tie the understanding of predicates to the syntactic structure, assuming that only syntactic constituents can be assigned meaning and hence only syntactic constituents can be predicates (cf. Heycock Reference Heycock2013: 322–323). On standard phrase structure grammar (PSG) accounts of sentence structures, then, the word combinations indicated in lines (8b–d) cannot qualify as predicates because they clearly do not qualify as constituents.Footnote 4 Only the word combination gave John a copy of War and Peace in line (8a) potentially qualifies as a constituent, and hence only that combination can be a predicate.

If one’s theory of the syntax-semantics interface accepts this dictum, namely that only constituents can be assigned meaning, then the word combinations of Variant 5 – e.g. has revised in the sentence Ian has revised his paper twice – cannot be predicates in most theories, since most theories do not view such combinations as syntactic constituents. In contrast, the word combinations of Variants 1–4 generally do qualify as constituents, at least at first blush. The discussion now turns more directly to this matter of constituent structure.

3.2. Finite vs. nonfinite VP

Rothstein (Reference Rothstein2004) rejects pragmatic attempts to motivate the existence of finite VP as the predicate for reasons similar to those just given in the previous section. She therefore endeavors instead to motivate the linguistic reality of the binary subject-predicate division in terms of tests for constituents. Rothstein’s message is that while the subject-predicate division cannot be motivated by pragmatic considerations, it can be motivated by syntactic ones. She claims that tests for constituents reveal the presence of a constituent encompassing everything but the subject, this constituent being the finite VP.Footnote 5 If, however, it can be demonstrated that a finite VP such as visited Mary in the sentence John visited Mary is in fact not a constituent, then the primary syntactic motivation supporting the predicates of Variants 1–3 falls away. As non-constituent word combinations, finite VPs cannot be assigned meaning and should hence not necessarily qualify as predicates.

Rothstein (Reference Rothstein2004: 20–25) produces seven pieces of syntactic evidence supporting the initial binary division of clause structure into a subject constituent and a finite VP predicate constituent, evidence from 1) VP-fronting, 2) pseudoclefting, 3) VP-ellipsis, 4) VP-conjunction, 5) argument ellipsis, 6) wh-extraction, and 7) pleonastic it. Scrutiny of these seven areas actually undermines Rothstein’s central claim, though. Rothstein’s main point in the area is that the object forms a constituent with the verb to the exclusion of the subject. While this insight is in part correct, Rothstein overlooks the fact that the object does this if and only if the verb at hand is nonfinite; if it is finite, there is no longer evidence supporting the existence of VP as a constituent. Quite to the contrary, the evidence produced below reveals that neither the object nor the subject forms a constituent with a finite verb; instead, the structure is flat with subject and object appearing equi-level in the structure.

To help establish the fallacy in Rothstein’s reasoning concerning the putative clause binarity she seeks to motivate, consider first the next two simple sentences, the second of which is the initial example that Rothstein (Reference Rothstein2004: 20) gives:

The tests for sentence structure that Rothstein employs certainly converge, revealing that nonfinite visit and Mary form the constituent visit Mary in (9a). Rothstein then mistakenly transfers this conclusion to sentences like (9b), though, where the verb visited is finite instead of nonfinite.Footnote 6 The issue at hand concerns which of the next structures is the best analysis of the two sentences:

Rothstein advocates for the structural analyses shown with the a-trees on the left, these analyses clearly involving the initial binary subject-predicate division. Upon scrutiny, however, the evidence she produces actually supports the flatter analyses on the right. The discussion in the next section examines the seven sources of evidence that Rothstein considers in this area, employing many of the same example sentences she produces.

3.3. Rothstein’s evidence (or lack thereof)

Rothstein’s first piece of evidence that finite VP is a constituent is from VP-fronting. Sentences (12a) and (13a) are her examples (40a–b), and examples (12b) and (13b) are her examples (41a–b) (Rothstein Reference Rothstein2004: 20):

Concerning the informant scores to the right, see examples (2a–b) above and the surrounding paragraph. The first thing to note about these examples is that Rothstein judges sentences (12a) and (13a) to be good. The scores here demonstrate, though, that Rothstein’s acceptability judgements are not accurate, those sentences being marginal to strongly marginal. Nevertheless, Rothstein is correct insofar as the b-sentences are noticeably worse than the a-sentences. What can one glean from such data, though? At best, one might conclude that the nonfinite VPs Visit her father and Eat a big dinner are constituents. Crucially, though, such data reveal nothing about the status of finite VP.

When one switches to intransitive verbs, the grammatical acceptability of such sentences can improve. The next sentences are analogous to (12–13), but now the b-, c-, and d-sentences probe the status of finite VP:

The a-sentences reveal that the nonfinite VPs Try and Rain can at least marginally be fronted and hence qualify as constituents. In contrast, the b-, c-, and d-sentences demonstrate that the finite VPs Tries, May try, Rains, and May rain cannot be fronted and hence do not qualify as constituents. Thus, VP-fronting actually contradicts Rothstein’s central claim concerning the binary subject-predicate division of the clause.

Rothstein’s second piece of evidence is from pseudoclefting. Sentences (16a) and (17a), in which the focused constituents are nonfinite VPs, are her examples (42a–b) (Rothstein Reference Rothstein2004: 21). The b- and c-sentences have been added to make the same point again concerning the corresponding finite VPs:

Rothstein again erroneously concludes that the acceptability of the a-sentences should allow one to view the corresponding finite VPs as constituents. The strong marginality of the b-sentences and the clear ungrammaticality of the c-sentences indicate again, though, that the strings visited her father, did visit her father, ate a big dinner, and did eat a big dinner are not constituents, again contradicting Rothstein’s central claim.

The third piece of evidence Rothstein produces is from VP-ellipsis. Sentences (18a) and (19a) are closely similar to Rothstein’s (Reference Rothstein2004: 21) sentences (43a–b). The b- and c-sentences are again added to make the point about the inability to transfer conclusions about nonfinite VP to finite VP:

The pointy brackets are used to indicate ellipsis; the elided constituents in (18a) and (19a) are the nonfinite VPs read War and Peace and eat an apple, respectively. Such instances of VP-ellipsis certainly support the existence of nonfinite VPs as constituents. But again, they do not support the transfer of this conclusion to finite VPs. The elision of the finite VPs in the b‑sentences results in instances of not-stripping. Stripping is arguably a manifestation of the gapping ellipsis mechanism, which is clearly capable of eliding non-constituent word combinations, as the c-sentences demonstrate.

The fourth piece of evidence Rothstein (Reference Rothstein2004: 23) produces is from VP-conjunction. Rothstein observes that the finite verb and its complements form a unit that can be conjoined. Her sentences in this area are next:

Rothstein then immediately concedes, though, that the next sentences are also possible, where the subject and finite verb appear to form a unit that can be conjoined to the exclusion of the complement(s):

These two groups of sentences would seem to cancel each other, such that there is no argument for or against the binary subject-predicate division of the clause.

Rothstein (Reference Rothstein2004: 23) observes further, however, that sentences like (21a–c) necessitate readings corresponding to complete clauses, whereas sentences (20a–b) do not do the same. She illustrates the point with the next examples:

The reading of sentence (22b) here is that of conjoined complete sentences, i.e. [A boy visited most soldiers] and [a girl wrote a letter to most soldiers]. The same is not true of sentence (22a), though, where the quantified subject scopes over both conjuncts. Rothstein concludes in this area, then, that cases like (21a–c) and (22b) involve conjoined clauses underlyingly rather than conjoined subject-verb strings, and these conjoined clauses do not count as an argument against the stance that VP-conjunction can coordinate verb-object combinations in a manner that is not possible for subject-verb combinations. What Rothstein overlooks, though, is that it is also possible to produce examples of like (21a–c) and (22b) that prohibit the reading as conjoined complete clauses, e.g.

What exactly is responsible for the difference in scope facts across sentences (22b) and (23a–b) is not clear. The point, though, is that coordination is a flexible mechanism that can coordinate a broad array of strings, many of which are not constituents. VP-conjunction is hence not a convincing argument in support of the binary subject-predicate division.

Rothstein’s fifth piece of evidence is from argument ellipsis. It is at times possible to elide an object argument whereas the same is not possible for the subject argument. Rothstein’s examples in this area are next (Rothstein Reference Rothstein2004: 24):

These data certainly do establish that the subject-verb relationship is unlike the verb-object relationship. However, the notion that this asymmetry supports the binary subject-predicate division of the clause does not follow. If anything, the asymmetry suggests, rather, that the subject’s link to the finite verb is stronger than the object’s link thereto, which might allow one to conclude that subject and finite verb form a constituent together to the exclusion of the object, the exact opposite situation from what Rothstein maintains.

Rothstein’s sixth piece of evidence is from wh-movement out of an embedded interrogative clause. Sentences (25a–b) are Rothstein’s examples (54) (p. 24) with her grammaticality judgments shown:

Rothstein states that the contrast in acceptability here is due to the structural asymmetry across subject and object; extracting the object is possible in (25a), but attempting to do the same with the subject is impossible in (25b). The problem with this argument is that Rothstein’s acceptability judgments are inaccurate. Both sentence (25a) and sentence (25b) are judged ungrammatical by informants. Sentences (25a–b) are now given again as (26a–b) but with the acceptability scores of informants included, and sentences (26c–d) are added to provide points of comparison concerning the level of acceptability:

Both sentence (26a) and sentence (26b) were judged ungrammatical as the scores of 3.00 and 3.82 demonstrate. While sentence (26b) was indeed judged to be worse than sentence (26a), both sentences are clearly ungrammatical, a fact that is evident when considering the much lower scores of 1.06 and 1.65 for sentences (26c) and (26d).

The seventh and final piece of evidence Rothstein produces involves pleonastic it. Rothstein writes that pleonastic it appears in subject position only; it cannot appear in object position. Her examples in this area are next (Rothstein Reference Rothstein2004: 25):

The fact that pleonastic it, a semantically vacuous element, is obligatory in such sentences demonstrates that the subject position must be filled. Since the same is not true of the object position, it should, according to Rothstein, again be evident that there is a fundamental subject-object asymmetry at the core of the grammar, and this asymmetry is best addressed in terms of the binary subject-predicate division of the clause.

Rothstein’s statements about the limited distribution of pleonastic it are not entirely accurate. The next a-sentences have pleonastic it appearing as the object complement of a preceding raising-to-object verb:

There are a number of facts suggesting that it in the a-sentences here is a complement of the preceding raising verb – rather than the structural subject of a putative ‘small clause’ constituent. The strings it unlikely that he will tell the truth and it quite probable that it will rain today fail standard tests for constituents. Those strings cannot be fronted, nor can they be replaced by a single proform or questioned by a single wh-word. More importantly, it becomes the subject in the corresponding passive sentences as demonstrated in (28b) and (29b), which is exactly as one expects if the structure is flat, such that pleonastic it in (28a) and (29a) is an object complement of the preceding raising verb.

A greater problem for Rothstein’s interpretation of sentences like (27a–b) is that for the binary subject-predicate division to be maintained, the strings seems that John is very late today and is unlikely that we will go to China this year are the predicates and as such, they must be constituents and should therefore be identifiable as constituents. Yet there is no test that convincingly verifies the existence of such constituents. Consider, for instance, that VP–ellipsis using the auxiliary does can identify the corresponding nonfinite VP in (27a) as a constituent, e.g.

But this datum in no way supports the existence of finite seems that John is very late today as a constituent. Interestingly, the same diagnostic using does accomplishes nothing when applied to example (27b):

The robust ungrammaticality of the B answer reveals that auxiliary do should not be construed as a pro-verb; it is, rather, simply an auxiliary verb, and as such it can license VP-ellipsis. The perfect acceptability of the Bˈ answer reveals that nonfinite unlikely that we will go to China this year is a constituent. In any event, there is no evidence anywhere in these examples suggesting that finite is unlikely that we will go to China this year is a constituent.

To summarize, Rothstein’s seven arguments in favor of the binary division of the clause into a subject constituent and a finite VP predicate constituent do not survive scrutiny. While some of them do clearly reveal the existence of nonfinite VPs as constituents, they do not do the same for finite VPs. In fact, the term finite VP is a misnomer – see footnote 2. A more accurate designation in this area would be finite verb string. Concerning the structural analyses, then, (10b) and (11b) are preferable over (10a) and (11a), since the former correctly show nonfinite VP as a constituent and the finite VP string as a nonconstituent.

A final point concerns the DG structural analyses of the sentences under discussion. Assuming that the S node in the trees of (10–11) is a projection of the finite verb, trees (10b) and (11b) automatically translate to the corresponding dependency trees, as shown next:

The translation procedure is indeed automatic. Any phrase structure tree in which all constituents are endocentric (i.e. headed) can be automatically translated to the corresponding dependency tree. If a phrase structure tree contains one or more exocentric (i.e. headless) constituents, however, it cannot be translated to dependency, since an inherent trait of dependencies is that they are directed.

3.3. Variant 4 vs. Variant 5

Variants 4 and 5 are both construed as Fregean because they both see predicates as properties or relations that take n arguments. The main difference between the two variants, though, is that Variant 4 construes just individual content words alone, usually a verb or adjective, as predicates and can hence claim that predicates correspond to actual constituents in sentence structures. In contrast, Variant 5 consciously abandons the notion that predicates should be, or should correspond to, constituents in sentence structures, allowing various function words to also be included in the word combinations that form predicates. The advantage that Variant 5 enjoys over Variant 4 is the obvious ability to shed light on the manner in which predicates are manifest synthetically or analytically across languages and within a given language. The difficulty with Variant 5 predicates, though, is that to pursue such an account, one has to abandon the notion that predicates necessarily appear as constituents in actual sentence structures.

The notion that the Variant 4 approach can consistently view predicates as constituents does not survive simple scrutiny. There are many cases where it is apparent that the word combinations of predicates do not correspond to constituents in actual sentence structures. The verb-particle combinations of phrasal verbs are perhaps the most vivid cases. The predicates assumed henceforth appear in bold:

The combinations put…on, took…up, and turned…off are single units of meaning and hence single lexical items, yet they obviously do not qualify as constituents in surface syntax. While one might stipulate that phrasal verbs do in fact qualify as constituents at a deep level of representation or at some early point in the derivation, there are other cases where it is apparent that the words of the predicate cannot be construed as constituents at any level of representation or any point in a derivation. Consider the words constituting the idioms in the next sentences in this regard:

The bolded words are arguably single units of meaning and hence single lexical items each time, yet the notion that such word combinations can ever be construed as constituents at any level of structure or at any point in a putative derivation is implausible.

The conclusion drawn here is that any attempt to require that predicates be, or correspond to, constituents in sentence structures cannot succeed. Thus, Variant 4 cannot claim to have the advantage of ‘constituenthood’ over Variant 5. In fact, the theory of predicates should abandon the notion that predicates are necessarily syntactic constituents. The DG approach that the discussion now turns to does just this, and it offers the catena unit as the alternative, that is, predicates must appear as catenae in sentence structures. Indeed, the bolded word combinations in (34–35) are all catenae.

4. Catena-based dependency syntax

The next three sections present the catena-based understanding of predicates and predications in the DG framework assumed. Due to space limitations, the discussion here does not attempt to introduce dependency syntax and establish how dependency structures are motivated, but rather it takes the dependency trees shown for granted. Note, though, that there is a substantial body of literature backing the dependency hierarchies assumed (see Osborne Reference Osborne2019 and the sources cited therein). These hierarchical structures are motivated directly by standard diagnostics for sentence structure (e.g. fronting, answer fragments, clefting, pseudoclefting, passivization, etc.). The complete subtrees of these dependency structures are usually the constituents that standard tests for constituents identify (see in particular Osborne Reference Osborne2018).

Finally, observe that there is a significant tradition of dependency syntax reaching back to Franz Kern (Reference Kern1883). A few of the most prominent works in this tradition that have influenced the current DG are listed next: Tesnière (Reference Tesnière1959), Hays (Reference Hays1964), Matthews (Reference Matthews1981), Melˈčuk (Reference Melˈčuk1988), Schubert (Reference Schubert1988), Hudson (Reference Hudson1990), Heringer (Reference Heringer1996), Groß (Reference Groß1999) and Eroms (Reference Eroms2000). Concerning the annotation schemes that are currently prominent in natural language processing (NLP) circles, the DG here is mostly in line with the annotation choices of the Surface-Syntactic Universal Dependencies (SUD) scheme (https://surfacesyntacticud.github.io/). Crucially, these choices are at least somewhat incompatible with the Universal Dependencies (UD) annotation scheme (https://universaldependencies.org/). The relevant annotation choices concern the hierarchical status of auxiliary verbs and adpositions, which are deemed here to be heads over, rather than as dependents under, the co-occurring content words. See Osborne (Reference Osborne2024) concerning the SUD vs UD debate.

4.1. The catena unit

The catena unit has been defined in various ways. Two definitions are given here, an informal one and a formal one (Osborne et al. Reference Osborne, Putnam and Groß2012: 359; Osborne Reference Osborne2019: 107–110):

Catena (informal definition)

A word or a combination of words that are continuous with respect to dominance.

Catena (formal definition)

Given a dependency tree T, a catena is a set S of nodes in T such that there is one and only one member of S that is not immediately dominated by any other member of S.

Stated in the simplest terms possible, any subtree of a dependency tree is a catena.Footnote 7 The next dependency tree is used to illustrate catenae.

The capital letters abbreviate the words. There are 33 distinct catenae in this tree, all of which are listed next: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, AB, BC, BE, CD, EG, FG, ABC, ABE, BCD, BCE, BEG, EFG, ABCD, ABCE, ABEG, BCDE, BCEG, BEFG, ABCDE, ABCEG, ABEG, BCDEG, BCEFG, ABCDEG, ABCEFG, and ABCDEFG.

The catena unit is a much more inclusive unit of syntax than the constituent unit of phrase structure grammar (PSG). There would likely be approximately 12 distinct phrase structure constituents acknowledged in the sentence The story about you surprised your friends (33 vs. 12). Certainly, every PSG constituent is a DG catena, but there are many DG catenae that are not PSG constituents. Concerning constituents further, dependency structures can also acknowledge their presence. The standard definition of the constituent unit is any complete subtree. There are, then, six distinct DG constituents in (36): A, D, F, CD, FG, and ABCD.

While the catena unit is a much more inclusive unit of syntactic analysis than the phrase structure constituent, it is important to acknowledge that there are usually significantly more non-catena word combinations in a given sentence than there are catena combinations. There are, for instance, 94 distinct non-catena word combinations in (36), e.g. AC, AF, ABG, DFG, DEF, CDEG, ADEFG, etc.Footnote 8 There are hence almost three-times more non-catena word combinations in (36) than there are catena combinations (33 vs. 94). The stance here concerning the inclusiveness/exclusiveness of the catena unit is that the catena is inclusive enough to acknowledge all the various word combinations that are relevant for the analysis of syntactic phenomena, and at the same time, it is exclusive enough to exclude all the word combinations that are not relevant to syntactic phenomena. Regarding predicates, the word combinations that one wishes to acknowledge as Variant 5 predicates are indeed catenae. These word combinations are, in contrast, very often not phrase structure constituents.

4.2. A definition and a condition

The discussion can now present a definition of the Variant 5 predicates assumed henceforth:

Syntactic predicate

A property or relation appearing as a word or a combination of words requiring the presence of zero to four arguments to express a complete idea; predicates assign semantic roles to their arguments

Given this definition, the Catena Condition specifies the word combinations that can qualify as syntactic predicates:

Catena Condition

For a combination of words to be a syntactic predicate, those words must form a catena in the dependency structure.

The Catena Condition imposes a concrete limitation on the syntactic form of predicates. The condition holds for word combinations that are intuitively predicates; it is the basis for an elegant theory that explains observed facts about language.

The Catena Condition should be evaluated with respect to the monograph-length theories of predicates developed by Napoli (Reference Napoli1989) and Ackerman and Webelhuth (Reference Ackerman and Webelhuth1998), these theories having influenced the current approach. Napoli (Reference Napoli1989: 14–15) emphasizes that the word combinations she acknowledges as predicates often do not qualify as constituents. She specifically argues that the theory of predicates should be freed from the overly narrow limitation that predicates be syntactic constituents. What Napoli and Ackerman & Webelhuth do not do in this area, though, is establish a concrete status in sentence structures for their predicates, but rather they remain vague about the precise nature of the word combinations that can and cannot form predicates. The Catena Condition overcomes this vagueness.

Observe that the definition just given is that of syntactic predicates. Predicates also exist as lexical-semantic entities. In order to distinguish between lexical-semantic and syntactic predicates, small caps are used for the former – as has already occurred above twice. Thus, the lexical-semantic predicate in the sentence Ian has revised his paper twice is revise, whereas the syntactic predicate is has revised. Important in this regard is the fact that many lexical-semantic predicates correspond to multi-word expressions, e.g. get over in John can’t get over his grade, spill the beans in Mary will certainly spill the beans, drive bananas in The music drove us bananas, etc.

Finally, the syntactic predicates identified and illustrated henceforth all qualify as catenae, in line with the Catena Condition. An interesting thought-experiment in this area is to seek to falsify the Catena Condition by identifying word combinations that intuitively express the meaning of a predicate but that clearly do not form catenae in the sentence structures. The task is not an easy one, as I believe the reader will discover for her- or himself going forward.Footnote 9

4.3. Predications

In addition to defining syntactic predicate in terms of the catena unit, the current account also defines predication in terms of the catena unit:

Predication

A property manifest as a catena in sentence structure and requiring the presence of no more than one argument to express a complete idea

To illustrate, example (8) from above is reproduced here as (37):

Recall that the example is from Rothstein (Reference Rothstein2004: 2); it demonstrates that the machinery of formal semantics, the lambda calculus, can easily abstract over any of the indicated positions in the structure. Given the definition, it is now apparent that the current account can acknowledge the indicated word combination each time as a predication.

Trees (38a–d) are the structural analyses of the indicated word combinations in (37a–d). Bold script now marks predications (rather than predicates); the predication each time encompasses everything except the x constituent:

Any time one removes a complete subtree, i.e. a constituent, from a dependency tree, what remains is also a subtree, but one that is obviously not complete. These incomplete subtrees are of course catenae, as these examples show.

Two points about predications can be mentioned here before turning back to the account of predicates. The first concerns the finite VP string. The discussion above demonstrated that finite VP is in fact not a constituent in sentence structure; it should be apparent now, though, that according to the definition, finite VP is a predication. The second point concerns truth values. While the definition does not make reference to truth values, it could be expanded to do so. Each of the catenae illustrated in (38a–d) would hence be of type <e,t>, delivering a truth value when applied to the argument occupying the position marked by x each time.

5. Synthetic vs. Analytic predicates

A primary motivation for assuming an understanding of predicates along the lines of Variant 5 is the ability to accommodate the synthetic vs. analytic manifestation of predicates across languages and within a given language. A one-word synthetic predicate in one language can correspond to a multi-word analytic predicate in another language or to a periphrastic version of that predicate within the same language. Grammatical categories of tense, modality, mood, aspect, voice, causation, etc., can be expressed synthetically or analytically depending on the language at hand, or depending on the specific construction assumed within one and the same language. The catena unit can accommodate these facts, since, regardless of the particular realization of the predicate at hand, that realization will appear as a catena in sentence structure.

The next three sections establish some foundational aspects of analytically realized predicates. Function words (auxiliary verbs, particles, separable prefixes, inert adpositions, etc.) are often included in the syntactic predicate formed around a lexical-semantic core.

5.1. Auxiliary verbs

The quintessential trait of analytical predicates is the presence of one or more auxiliary verbs. The auxiliaries form a syntactic predicate with one or more content words, often with a content verb (cf. Napoli Reference Napoli1989: 13). There are clear reasons why auxiliary verbs should be included in the syntactic predicate. One is that auxiliary verbs do not influence the semantic selection of nominal arguments, which means they cannot be construed as predicates in their own right. More importantly, auxiliary morphs cannot be separated out from the predicate in synthetic languages, so it is better to include them in the predicate in analytic languages as well. In this manner, greater structural and semantic parallelism is achieved across analytic and synthetic languages.

The next three simple synonymous sentences from French, English, and German illustrate the manner in which the lexical-semantic predicate see can be realized synthetically or analytically in syntax. Bold script again identifies the matrix predicate:

The synthetic predicate verra in French translates to the analytic predicates will see in English and wird…sehen in German. In all three sentences, the predicate is a catena, and this is even so in (39c), where the words wird and sehen are not adjacent to each other.

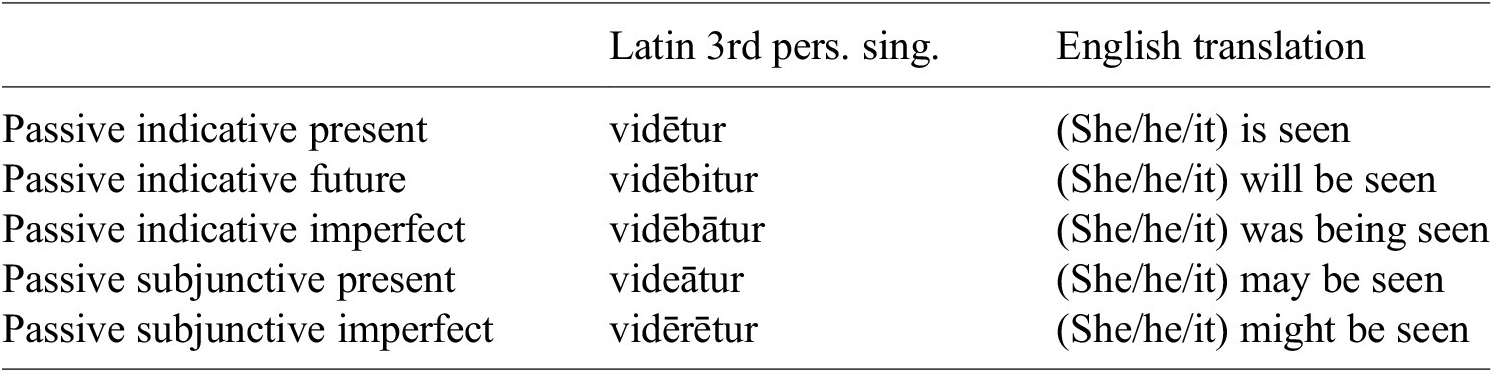

Consider next the English equivalents of verbal predicates in Latin. Latin is known to be a synthetic language, especially in its verb conjugations. A single verb form in Latin often translates to two or three verbs in English. Table 4 is just a portion of the conjugation paradigm of the Latin verb videō ‘I see’, the 3rd person singular passive portion of the paradigm. Single words are by definition always catenae, hence vidētur, vidēbitur, etc. appear as catenae in Latin sentences. Similarly, the verb combinations is seen, will be seen, etc., appear as catenae in English sentences.

Table 4. A portion of the conjugation paradigm for the Latin verb videō ‘I see’, the passive 3rd person singular part

5.2. Particles and separable prefixes

Examples (34a–c) from above illustrating phrasal verbs are repeated here, but now with the dependency trees added:

The predicates in these cases are analytical insofar as they consist of two words each time, the verb and its particle. Note that neither verb nor particle alone qualifies as a predicate, since neither word alone can be assigned a concrete meaning.

These phrasal verb predicates in English are similar to separable prefix verbs in other languages, the separable prefixes being similar to the particles in how they are often separated from the governing verb. Ackerman and Webelhuth (Reference Ackerman and Webelhuth1998) motivate their account and understanding of predicates by pointing precisely to such analytic expressions of predicates across languages and within a given language. Two of their Hungarian sentences involving a separable prefix are diagrammed dependency-style next:

In sentence (41a), the predicate beleszolt ‘intervene’ is synthetic, whereas in sentence (41b), the same predicate is expressed analytically. The appearance of the negation nem ‘not’ in (41b) necessitates the separation of the prefix bele ‘into’ from its host szolt ‘spoke’, such that the predicate clearly comes to consist of two distinct words. These two words form a catena.

Separable prefix verbs occur frequently in German (e.g. aufhören ‘stop’, anfangen ‘start’, einleiten ‘introduce’). The next example pair involves the separable prefix verb abdanken ‘abdicate’:

The predicate abdankte ‘abdicated’ is expressed synthetically in (42a), where the appearance of the subordinator dass ‘that’ forces verb-final word order. In contrast, the predicate dankte…ab ‘abdicated’ is expressed analytically in the independent clause in (42b), where the finite verb occupies the second position in the sentence. In both cases, the verb and its separable particle form a catena.

The existence of the particles of phrasal verbs and of the separable prefixes of separable prefix verbs forces the Fregean understanding of predicates to concede that predicates can appear as non-constituent word combinations in sentence structures, supporting the Variant 5 understanding of predicates over Variants 1–4.

5.3. Inert adpositions

Adpositions are often inert, mostly devoid of semantic content, and are idiosyncratically chosen by their parent word (cf. Napoli Reference Napoli1989: 31–32; Rothstein Reference Rothstein2004: 56). If the parent word is a verb or an adjective, the adposition is easily included in the syntactic predicate of the parent word. The resulting predicates are therefore analytical insofar as they consist of more than one word, e.g.

The choice of preposition in each of these sentences is determined by its parent word, called its governor in DG nomenclature. The governor and its postdependent preposition quite naturally form the matrix syntactic predicate.

The idiosyncratically determined prepositions in sentences (43a–d) can be compared to locative prepositions, which are semantically loaded and can be construed as predicates in their own right. As secondary predicates, they do not incorporate into the predicate of their governors, e.g.

The (non)incorporation of prepositions into the predicate of their governors is important for the theory of pronoun resolution (i.e. binding theory). In this regard, note the occurrence of him, her, and her in these sentences – as opposed to himself, herself, and herself. The discussion returns to such prepositions below in Section 7.

6. Mutual Entailment

The next three sections develop further the insight concerning synthetic and analytic predicates, but now in terms of entailment. Two sentences that mutually entail each other should receive similar predicate-argument analyses. In particular, they should have the same number of arguments and these arguments should receive the same semantic roles assigned to them by the predicates.

6.1. Light verbs

The current understanding of synthetic and analytic predicates extends naturally to light verb constructions. Simple predicates such as shower, hug, and smoke can be expressed analytically as take a shower, give a hug, and have a smoke. The informant judgments we have collected reveal that such sentence pairs mutually entail each other.

The sentences are now presented in pairs that indicate the direction of entailment – see examples (3a–b) above, with the dependency trees and c-lines added, the latter giving the predicate-argument analyses of the sentences at hand.

The scores reveal that the first sentence clearly entails the second each time. Mutual entailment like this provides a strong argument for the predicate-argument analyses shown in the c-lines. The predicate is (reaching down from) the root word of the sentence. With the light verb constructions, the predicate includes the common noun and potentially the following preposition of if present. The two predicates in each pair are closely similar, the core of each being expressed by a fully loaded content word (showered-shower, hugged-hug, criticized-criticism).

The examples just discussed are straightforward, there being little difficulty in judging the verbs take, give, and express to be ‘light’ in the example sentences. More generally, however, determining which verbs qualify as light verbs is less straightforward, as with, for instance, formulations such as fight a war against and propose a revision of. Footnote 10 A diagnostic that can help reveal the reach of predicates in such cases is pronoun resolution. This matter is taken up in Section 7 below.

6.2. Copular sentences

The account of synthetically and analytically expressed predicates extends to copular sentences of all sorts. The sentences of the next pairs also mutually entail each other, suggesting again that the predicate-argument analyses should be similar:

The predicate is reaching down from the copula to include the agentive noun and its postdependent preposition of. Note again that the lexical-semantic core of the predicate of each pair is consistent (creates-creator, supports-supporter).

The account also extends to copular sentences that are clearly specificational. The initial noun phrase of a specificational copular sentence is widely deemed to be predicative, with the post-copular noun phrase then being the argument (e.g. Gundel Reference Gundel1977; Heggie Reference Heggie1988; Moro Reference Moro1997; Mikkelsen Reference Mikkelsen2005; Geist Reference Geist2007; Patten Reference Patten2018). The current theory of predicates can easily accommodate this type of analysis. While predicates typically reach from the root word of the sentence down to the right, nothing prevents them from reaching from the root down to the left instead, e.g.

The sentences ?A creator of content is Joan and ?A supporter of Sanders is Mike were judged marginal.Footnote 11 The marginality makes it difficult to determine whether the uninverted counterparts should be interpreted as predicational or specificational. Regardless of the particular analysis in this area, though, the syntactic predicates shown are plausible since they allow the account to remain consistent, accommodating the pattern of mutual entailment.

The next example pairs extend the analysis to a kinship noun – kinship nouns are relational, taking two arguments when used predicatively:

The predicate is again reaching down from the copula to include the predicative noun and potentially other words dependent on the noun as well. Noteworthy is the inclusion of the Saxon ’s in the predicate. The Saxon ’s is a clitic, which is indicated in the tree by the presence of the hyphen on the left side of s and the absence of a vertical projection line reaching up to s (cf. Groß 2014).

7. Pronoun Resolution

The current account of predicates also sheds light on the distribution and resolution of anaphoric elements. There have certainly been many theories of pronoun resolution over the years that build centrally on predicate-argument structures (e.g. Levinson Reference Levinson1991; Reinhart & Reuland Reference Reinhart and Reuland1993; Pollard & Sag Reference Pollard and Sag1992, Reference Pollard and Sag1994; Reuland & Reinhart Reference Reuland, Reinhart, Haider and Vikner1995; Bresnan Reference Bresnan2001; Lidz Reference Lidz2001; Culicover & Jackendoff Reference Culicover and Jackendoff2005; Culicover Reference Culicover2009). The approach to predicates in syntax here can make these theories more compelling, since predicates now enjoy a concrete status in sentence structures. In fact, the distribution and resolution of pronouns can serve as a diagnostic for identifying the reach of predicates, as mentioned at the end of Sections 5.3 and 6.1.

The co-indexed expressions in the next sentences are clearly co-arguments each time, and correspondingly, the acceptability judgments of informants are robust:

Concerning the scores to the right, see examples (4a–b) above and the surrounding paragraph. The simple pronoun and self-pronoun are in complementary distribution in these sentences, which is expected insofar as the two are co-arguments each time. They are both, namely, immediate dependents of the predicate.

This complementary distribution disappears in other cases, though, cases in which the co-indexed expressions can no longer be interpreted as co-arguments, e.g.

The predicate in these cases does not reach into the object noun phrase each time, which means that the co-indexed expressions cannot be construed as co-arguments. Accordingly, the scores demonstrate that there is a measure of free variation in the choice of anaphoric element, although there is a preference for the self-pronoun over the simple pronoun.

Examples (58–60) can be compared to the next sentences in which the predicate does reach into the object noun phrase:

These sentences qualify as light verb constructions. The core semantic content of the predicates is located in the nouns operation, description, and picture, the verbs performed, gave, and took being light. Complementary distribution is again discernible, which is predictable because the co-indexed expressions qualify as co-arguments, both being immediately dependent on the predicate.

Switching to the semantically loaded prepositions of the sort mentioned and illustrated in Section 5.3 above, the predicate does not reach into the prepositional phrase and hence does not include the preposition:

A measure of free variation is evident again in the scores, which is predictable insofar as the co-indexed expressions are not co-arguments. Examples (64–66) can be compared to the next examples involving the relatively inert preposition to:

The preposition to is functional and hence not semantically loaded in the manner of true locative prepositions. Note that sentences (67a, 68a) alternate with ditransitive sentences: Jack sent himself a gift, Mandy gave herself the candies.

The core insight about the reach of predicates is demonstrated perhaps most vividly by considering the distribution of possessive determiners (e.g. his, her, etc.). These words are simple pronouns; they are not reflexive. They can become reflexive, though, if own is added, e.g.

The complementary distribution across the a- and b-sentences establishes that the extent of the predicate indicated each time is accurate. The predicate in the a-sentences reaches down to include the predicative noun boss or agent, rendering the co-indexed expressions co-arguments. In contrast, the predicate in the b-sentences does not reach into the object noun phrase, so the co-indexed expressions there are not co-arguments. The c-sentences draw attention to the fact that when own is added, the pronoun becomes reflexive, allowing for the coreferential reading.

One final example is considered, the example fight a war against from the end of Section 6.1 above. The challenge with such cases concerns the reach of the predicate. Does it extend down to include a war against, or should the verb fight alone be construed as the predicate? Examine the next two data points in this regard:

The fact that himself is much better than him reveals that the predicate should indeed be construed as shown. That is, the predicate reaches down to include a war against such that John and himself/him become co-arguments. It is in this respect that pronoun resolution can be a diagnostic helping to identify the reach of predicates.

To sum up, the current understanding of predicates allows for a vivid account of the core data associated with the distribution of anaphoric elements. In particular, it allows binding theory to discern when two coreferential expressions are or are not co-arguments. In doing so, the distribution of pronouns has become a source of support motivating the Variant 5 understanding of predicates pursued in this article.

8. Conclusion

This article has surveyed the linguistics world concerning the notions predicate and predicator. It has established that use of the term predicate varies significantly from one theory to the next, and from one grammarian to the next. Motivated by this variability and vagueness, a concrete definition of predicate has been given, one based on a dependency grammar (DG) approach to syntax that builds centrally on the catena unit of sentence structure. Predicates are catenae in syntax, and these catenae are often not constituents. The account has also defined predication as a catena. Support for the catena-based understanding of predicates and predications has been taken from three sources: synthetic vs. analytic expressions of meaning, entailment patterns, and pronoun resolution.

The theory of predicates developed here is of course in need of expansion and refinement. Most of the discussion has focused on primary predicates, that is, on the main predicate in finite clauses. Little guidance has been provided about the nature and distribution of secondary predicates. Certainly, secondary predicates also play an important role in determining aspects of sentence grammar, aspects associated with, for instance, raising and adjuncts. Future research efforts will hopefully expand the approach to predicates presented above to also address the distribution and nature of secondary predicates.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Appendix

The informant judgments reported on in this article were collected in 2023 and 2024 using the crowdsourcing service Amazon Mechanical Turk. Two Likert scales were employed, either 1–4 or 1–3. The workers (the informants) were paid five cents per sentence judged. They were tasked with assessing grammatical acceptability (scale 1–4) or the presence of entailment (scale 1–3). Ten to twenty sentences were tested at a time, with 20 workers providing judgments. Thus in each batch, 200 to 400 judgments were collected. The scores were then always averaged in order to provide an easily understandable general assessment of acceptability.

Amazon Mechanical Turk has criteria for quality control that were of course accessed. Workers had to be located in the United States and had to have a relatively high approval rate of overall intellectual tasks performed (exceeding 98%) to qualify in order to provide judgments. Nevertheless, constant management of the data collection effort was necessary. Control sentences were included in each batch of data collected, these sentences being black-and-white concerning the issue tested. Workers who failed two or more of these control sentences then had all their judgments excluded and were blocked from further participation. This sort of quality control was maintained throughout the data collection process. When reporting the scores, a number of, say, 17 before the slash indicates that the 3 of the 20 informants had all their responses excluded due to failure of quality control.

There was a general tendency among workers to err on the side of permissibility. For this reason, the particular scale for assigning judgments to the left of the example sentences reported on was employed: (no indicator) = 1.00–1.64, ? = 1.65–2.29, ?? = 2.30–2.94, * = 2.95–4.00.