Highlights

-

Systematic review of 4 studies (622 patients) shows early mobilization after chronic subdural hematoma (cSDH) surgery is safe, with no increase in recurrence and fewer complications.

-

Early mobilization may also improve functional recovery compared to delayed mobilization.

-

Findings support reconsidering traditional bed rest in postoperative management of cSDH.

Introduction

Chronic subdural hematoma (cSDH) is one of the most common neurosurgical pathologies, which has a predilection for affecting the elderly. The incidence rate is approximately 130 cases per 100,000 persons over the age of 80 annually and is projected to rise given an aging global populace and increased use of antithrombotic medications. Reference Rauhala, Luoto and Huhtala1–Reference Baiser, Farooq, Mehmood, Reyes and Samadani3 This condition is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, increasing the burden on healthcare institutions worldwide. Reference Miranda, Braxton, Hobbs and Quigley4–Reference Feghali, Yang and Huang7 In patients with neurological sequelae, surgical evacuation, typically via burr-hole craniostomy, is the mainstay of treatment. Reference Duerinck, Der Veken and Schuind8–Reference Mehta, Harward, Sankey, Nayar and Codd10 Despite being one of the most common neurosurgical procedures, approximately 10%–20% of surgically treated cSDH patients experience postoperative recurrence that requires reoperation. Reference Kolias, Chari, Santarius and Hutchinson11

Postoperative management strategies for these patients are heterogeneous across neurosurgical centers, particularly concerning the timing and extent of postoperative patient mobilization and positioning. Reference Kolias, Chari, Santarius and Hutchinson11,Reference Holl, Volovici and Dirven12 Traditional teaching emphasized prolonged bed rest and supine position based on the hypothesis that it promotes brain re-expansion, thereby reducing the risk of hematoma recurrence. Reference Abouzari, Rashidi and Rezaii13 However, this approach carries inherent risks of prolonged immobilization, such as pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis and pressure ulcers. These complications can delay recovery, increase the length of hospital stays and raise healthcare costs. Reference Perme and Chandrashekar14,Reference Tazreean, Nelson and Twomey15 In response to these concerns, there has been a growing interest in improving the postoperative management of cSDH patients, such as patient positioning and mobilization. Recent analyses have indicated no difference in recurrence rates based on postoperative head positioning. Reference Abouzari, Rashidi and Rezaii13,Reference Serag, Abdelhady and Awad16–Reference Tamura, Sato, Yoshida and Toda20 Although postoperative mobilization is recognized as beneficial in other neurosurgical pathologies, few studies investigating early postoperative mobilization have been done on cSDH, and what research does exist has not been systematically evaluated. Reference Wang, Xue and Zhao21–Reference Rupich, Missimer and O’Brien24

Herein, we conducted a systematic review to evaluate whether early postoperative mobilization compared to late or standard mobilization is associated with differences in recurrence rates, postoperative complications, functional recovery and length of hospital stay among patients undergoing surgical evacuation for cSDH. This study aims to summarize the state of the literature to help guide clinicians on the optimal postoperative management of this patient population. When made possible by homogenously reported outcomes, we also performed a supplementary meta-analysis of early versus late mobilization.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Reference Page, McKenzie and Bossuyt25 We reported definitions of early mobilization (EM) and delayed mobilization (DM) as defined by the included studies. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective cohort studies and retrospective cohort studies that included a direct comparison group were eligible for inclusion. Case reports, case series without a comparison group, review articles, editorials and conference abstracts were excluded. We attempted to identify full papers resulting from conference abstracts if the abstract or presentation met our inclusion criteria. The reference section of papers that met the inclusion criteria of our review was examined for any other relevant papers. No restrictions on language were placed.

Our research question was defined and guided using the Population, Intervention, Comparator and Outcome (PICO) framework.

-

Population (P): Adult patients undergoing surgical treatment of cSDH.

-

Intervention (I): EM (as defined by each study, no pre hoc restriction placed on timing).

-

Comparator (C): DM (as defined by each study).

-

Outcomes (O): The primary outcome was recurrence of cSDH. Secondary outcomes included the incidence of postoperative medical complications (e.g., infection, seizure or thromboembolic events), surgical details (type of surgery, use of drains), functional outcomes at discharge or follow-up and length of hospital stay.

We searched Medline, Embase, Scopus and Web of Science from database inception until May 1, 2025. A medical librarian assisted in search strategy design (Supplementary Material 1).

Two independent reviewers (D.C. and K.O.) screened titles and abstracts against the predefined eligibility criteria. Duplicate records were removed. Full-text reviews were performed independently by two reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with the two reviewers, as well as with a third reviewer (K.C.), where a complete consensus between all three reviewers was required. Our team scheduled a midpoint recalibration meeting halfway through both the screening and full text review to discuss any questions from screening team members.

For each included study, data were extracted on study characteristics (author, year of publication, country, study design, follow-up duration), patient demographics (total sample size, number of patients in early and late mobilization groups, mean age, sex distribution, relevant comorbidities), intervention details (specific definition of early and late mobilization) and outcome data. Data extraction was conducted by two reviewers (D.C. and K.O.), with any disagreements again resolved through discussion between these two reviewers, as well as a third reviewer (K.C.).

Supplemental Statistical Analysis Information pertaining to the supplemental meta-analysis can be found in the supplemental methods document (Supplementary Material 2).

Results

We identified 1295 articles, of which 4 met the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were included in our systematic analysis. The results of our search strategy are detailed in the PRISMA diagram in Figure 1. Study design included one RCT (Sousa et al.), one prospective cohort study (Adeolu et al.), one retrospective cohort study with historical controls (Kurabe et al.) and one propensity-matched cohort study (Staartjes et al.). Reference Kurabe, Ozawa, Watanabe and Aiba26–Reference Staartjes, Spinello, Schwendinger, Germans, Serra and Regli29 Each study had an equal number of patients in their respective mobilization group.

Figure 1. PRISMA – early versus late mobilization of chronic subdural hematoma.

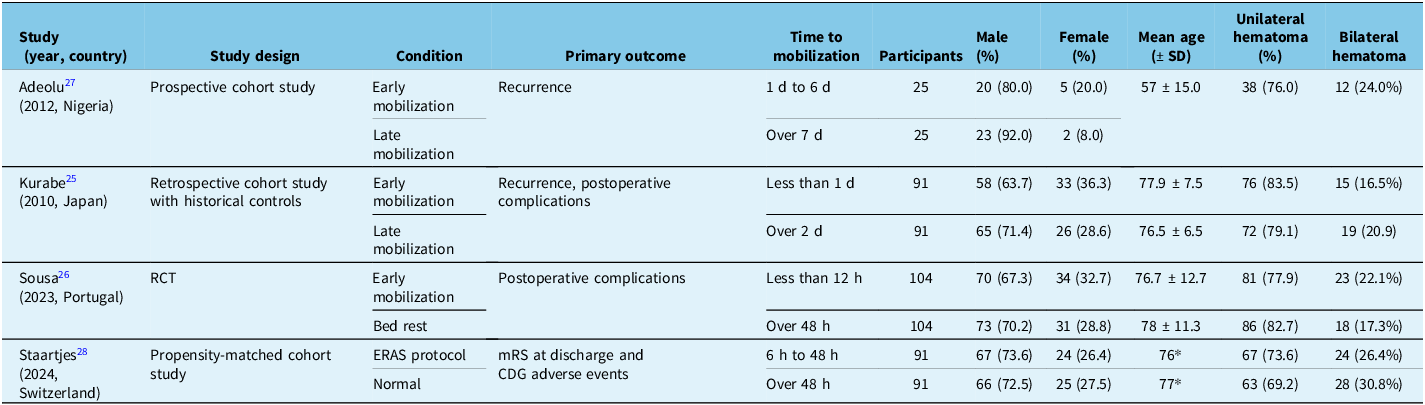

Overall, 622 patients were included (Table 1). The pooled mean age across these studies was 75.0 ± 12.4 years. The majority of patients were male (442, 71.1%), and 22.3% of patients had a bilateral hematoma. Other patient data, including comorbidities and preoperative status, were inconsistently reported and are instead included in the supplement (Supplementary Material 3). Postoperative outcomes for each study can be found in Table 2.

Table 1. Study descriptions

Note: ERAS = early recovery after surgery; SD = standard deviation; RCT = randomized control trial; mRS = modified Rankin Scale; CDG = Clavien–Dindo grading.

* No SD reported.

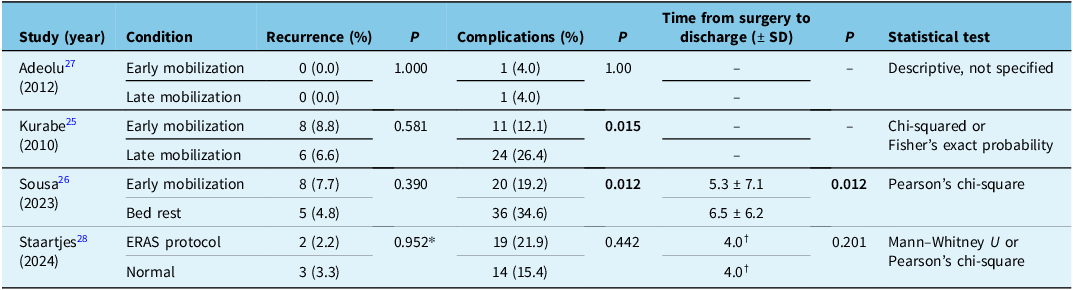

Table 2. Systematic review results

Note: ERAS = early recovery after surgery; SD = standard deviation; RCT = randomized control trial.

* P value comparing the total difference in dynamic maximum hematoma thickness between groups.

†No SD reported.

Values not reported are denoted by “–“.

Recurrence

The impact of early versus late mobilization on cSDH recurrence failed to reach significance in all studies. Adeolu et al. reported no recurrence in any patient. Kurabe et al. found no statistically significant difference in recurrence rates between the EM (8/91, 8.8%) and DM (6/91, 6.6%) groups (p = 0.58). Reference Kurabe, Ozawa, Watanabe and Aiba26,Reference Adeolu, Rabiu and Adeleye28 Sousa et al. documented three recurrences in each group at the time of discharge, and at one-month follow-up, they found no statistically significant difference between the EM (8/104, 7.7%) and DM (5.104, 4.8%) groups (p = 0.39). Reference Sousa, Pinto and da Silva27 Staartjes et al. did not specifically report recurrence as a primary outcome. However, they reported imaging outcomes at first follow-up. Two of 91 (2.2%) patients in the EM group had increased dynamic max hematoma size compared to 3 of 91 (3.3%) in the DM group. Reference Staartjes, Spinello, Schwendinger, Germans, Serra and Regli29 This was no significant difference between the EM and DM groups (p = 0.471 for absolute thickness, p = 0.952 for dynamic thickness). We conducted a supplemental meta-analysis to assess the pooled effect of mobilization on recurrence, which did not identify any changes between groups (Supplementary Material 4).

Complications

Adeolu et al. recorded one complication in each group (p = 1.00). Reference Adeolu, Rabiu and Adeleye28 Kurabe et al. found a statistically significant reduction in the number of patients with at least one postoperative complication in the EM (11/91, 12.1%) compared to the DM (24/91, 26.4%) group (p = 0.015). Reference Kurabe, Ozawa, Watanabe and Aiba26 Sousa et al. reported that medical complications at discharge occurred significantly less often in the EM group (20/104, 19.2%) compared to the DM (36/104, 34.6%) group (p = 0.012). Reference Sousa, Pinto and da Silva27 Staartjes et al. reported no significant difference in the severity of postoperative complications (graded by the Clavien–Dindo adverse event grading classification) or occurrence of any adverse events at discharge (p = 0.442) and at follow-up (p = 0.560) between groups. Reference Staartjes, Spinello, Schwendinger, Germans, Serra and Regli29 Details on specific complications can be found in Table 3. We conducted a supplemental meta-analysis to assess the pooled effect of mobilization on complications, which did not identify any changes between groups (Supplementary Material 5).

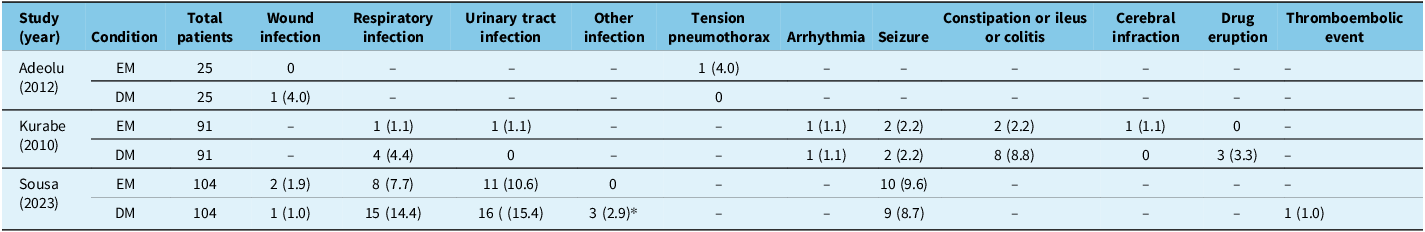

Table 3. Patient complications

Note: Values are shown as number (%) unless otherwise specified.

EM = early mobilization; DM = delayed mobilization.

* Other infections include one superior limb cellulitis, one acute otitis media and one perineal fungal infection.

Values not reported are denoted by “–“.

Time from surgery to discharge

Data on the length of time between surgery and discharge were only detailed in two studies. Sousa et al. reported a significantly different mean time from surgery to discharge of 6.5 ± 6.2 days in the DM group and 5.3 ± 7.1 days in the EM group (p = 0.012). Reference Sousa, Pinto and da Silva27 Conversely, Staartjes et al. found no significant difference in time from procedure to discharge (p = 0.201) or total hospital length of stay (p = 0.113) between their standard and enhanced recovery protocol groups. Reference Staartjes, Spinello, Schwendinger, Germans, Serra and Regli29

Functional recovery

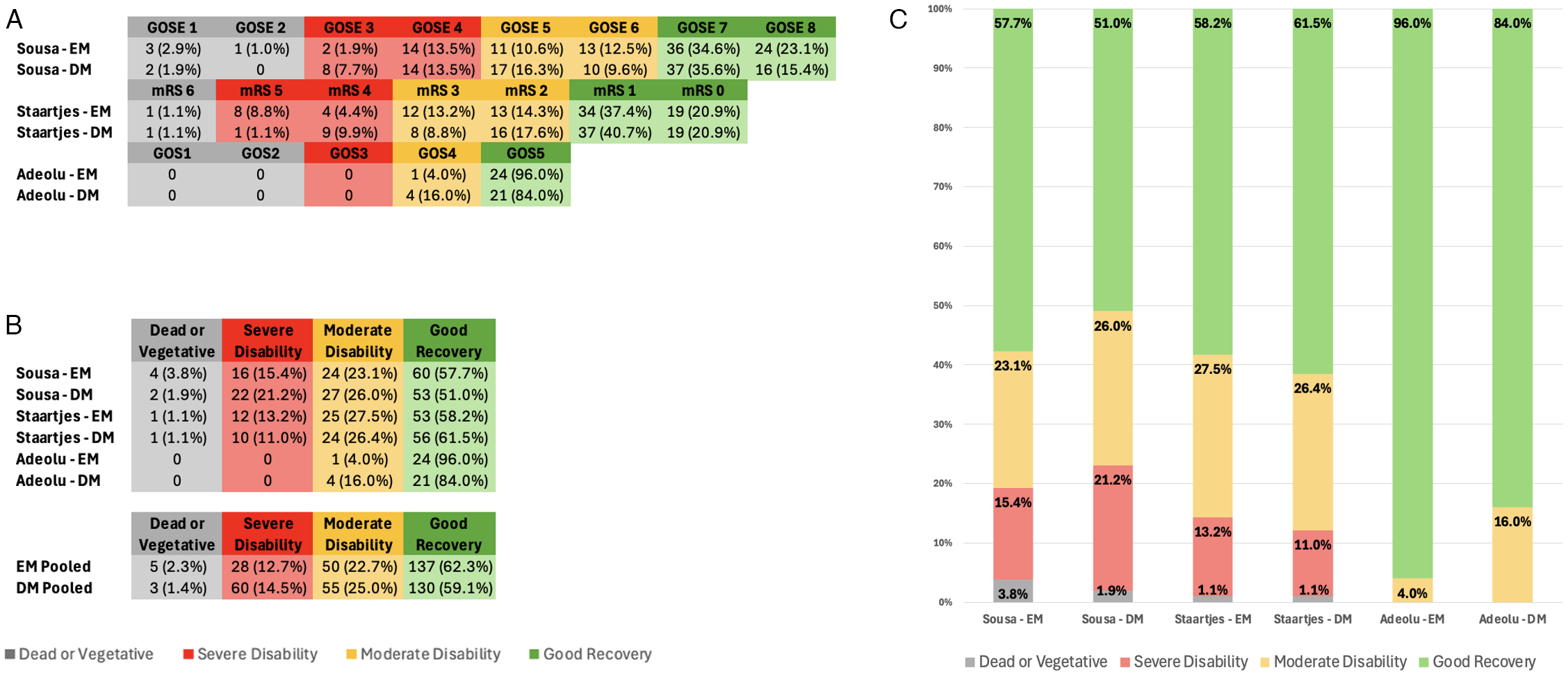

Functional recovery outcomes were reported in three studies, each using a different grading scale. Adeolu et al. utilized the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS). Reference Adeolu, Rabiu and Adeleye28 At discharge, 24 (96.0%) EM and 21 (84%) DM patients achieved a good recovery, as defined by a GOS = 5. The remaining patients, one (4.0%) in the EM and four (16.0%) in the DM group, had a GOS = 4, defined as moderate disability. These differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.349). Sousa et al. utilized the Glasgow Outcome Scale – Extended (GOSE). Reference Sousa, Pinto and da Silva27 They reported a favorable functional outcome, defined as GOSE ≥ 5, in 85 (81.7%) of patients in the EM group and 75 (72.1%) of patients in the DM group. This showed a trend toward improvement with EM but was not statistically significant (p = 0.100). They reported good recovery, defined as GOSE ≥ 7, in 78 (75.0%) patients in the EM group and 63 (60.6%) patients in the DM group. This comparison was statistically significant (p = 0.026). Staartjes et al. did not report any significant differences in the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) between the EM and DM groups at time of discharge (p = 0.552) or first follow-up (= 0.737). Reference Staartjes, Spinello, Schwendinger, Germans, Serra and Regli29 To harmonize the outcome data between scales, the scores for each scale were sorted into four outcome categories. These were “Good Recovery” (GOSE of 7–8, mRS of 1–2, GOS of 5), “Moderate Disability” (GOSE of 5–6, mRS of 3–2, GOS of 4), “Severe Disability” (GOSE 3–4, mRS of 4–5, GOS of 4) and “Dead or Vegetative Status” (GOSE of 1–2, mRS of 6, GOS of 1–2). When comparing pooled functional outcomes, the proportion of patients achieving Good Recovery (n = 137, 62.3%) versus Not Good Recovery (n = 130, 59.1%) did not differ significantly between the EM and DM groups (χ 2(1) = 0.34, p = 0.56). Other functional outcomes like Glasgow Coma Scale, Karnofsky Performance Status and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale also showed no significant differences. Kurabe et al. did not report on the functional outcomes. Reference Kurabe, Ozawa, Watanabe and Aiba26 A summary of functional outcomes is displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2. . Patient functional outcomes. (A) Patient functional outcomes per study, separated by EM and DM. The scale used to grade functional outcomes depended on the study. Functional outcomes are further categorized based on the following groupings as described by their respective scale: Dead or Vegetative, Severe Disability, Moderate Disability and Good Recovery. (B) Number and percentage of patients in each study categorized by functional outcome category, separated by EM and DM. Number and percentage of patients pooled by functional outcome category are also displayed. (C) Graphical representation of the percentage of patients in each study categorized by functional outcome category, separated by EM and DM. EM = early mobilization; DM = delayed mobilization; GOSE = Glasgow Outcome Scale – Extended; mRS = modified Rankin Scale; GOS = Glasgow Outcome Scale.

Discussion

This systematic review synthesized the current evidence regarding early versus late mobilization on outcomes in adult patients undergoing surgical evacuation for cSDH. Our findings suggest that EM is safe and may reduce postoperative complications and improve functional recovery, without any increased risk of hematoma recurrence. All four studies reported no significant differences in cSDH recurrence rates between groups. This was consistent with our supplemental pooled analysis, which likewise found no statistical differences between groups.

Two studies demonstrated a significant reduction in medical complications with EM. This reduction appeared to be attributed to lower rates of pneumonia, urinary tract infections and gastrointestinal complications such as constipation and ileus. These findings are consistent with the broader surgical literature, which shows how early ambulation reduces complications associated with prolonged immobility, particularly respiratory and urinary issues. Reference Chen, Wan and Wang23,Reference Rupich, Missimer and O’Brien24,Reference Turan, Khanna and Brooker30,Reference Rosowicz, Brody and Lazar31 However, this was not replicated in all of the included studies. Notably, the paper by Staartjes et al. did not find a significant difference in overall adverse events despite a comprehensive enhanced recovery after surgery protocol. The authors acknowledged that protocol adherence likely varied between patients, potentially diminishing the observed impact. Additionally, their protocol included multiple elements, making it difficult to interpret the impact of mobilization timing on their reported complication rates. Adeolu et al. only identified one complication in each group, suggesting the study was likely underpowered to detect any significant change in complication rates.

The assessment of functional recovery across included studies revealed mixed findings. The GET-UP trial by Sousa et al. found a significant improvement in functional outcomes, with a higher proportion of patients in the EM group achieving favorable scores on the GOSE (GOSE ≥ 7) at one month postoperatively. Notably, this study also demonstrated a significant reduction in postoperative complications, which is known to impact functional outcomes after neurosurgical procedures. Reference Reponen, Tuominen, Hernesniemi and Korja32,Reference Sarnthein, Stieglitz, Clavien and Regli33 This supports the idea that fewer complications may have contributed to better outcomes, though it is unclear if these occurred in the same patients. In contrast, Staartjes et al. found no difference in functional outcomes between groups. This was attributed to protocol complexity and variations in adherence, which may have diluted the benefits of EM. Adeolu et al. also reported no significant difference in functional outcomes (GOS) at discharge. However, the majority of patients in both groups achieved a maximum GOS score, suggesting a possible ceiling effect, limiting the ability to detect further improvement. Overall, these differences may reflect variations in study design, follow-up duration, mobilization timing and how outcomes were measured.

The impact on the length of hospital stay also remains mixed. While Sousa et al. reported a significant reduction in hospital stay with EM, Staartjes et al. did not observe this effect. This variability might reflect differences in healthcare systems, discharge criteria or the specific components of the “early mobilization” protocols. As the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery protocol adopted by Staartjes et al. implemented multiple changes, these differences in the timing of other interventions, such as the initiation of thrombosis prophylaxis and earlier restarting of oral anticoagulants or antiplatelets, may have obscured the effect of EM.

This review identifies several limitations in the literature on mobilization after cSDH surgery. First, the number of included studies was small, limiting the ability to perform a meaningful quantitative analysis. Second, there were considerable differences in study design, with only one RCT and three observational studies. Observational designs carry a greater risk of bias due to confounding factors, even when methods such as propensity matching, as used in Staartjes et al., are applied. The single-center nature of all studies further limits the generalizability of their findings. There were also major inconsistencies in the definitions of key variables, such as what constituted “early” and “late” mobilization, definitions of recurrence and differences in functional outcome assessments. The timing of EM ranged from 6 to 24 hours postoperatively, while DM ranged from after 2 days to beyond 7 days. Definitions of recurrence and functional outcome measures also varied across studies. In addition, differences in postoperative care, including positioning protocols, use of thromboprophylaxis and drain management, may have influenced outcomes. Finally, the follow-up periods varied and were not consistently reported beyond two months across all studies. These factors limited our ability to perform further quantitative analysis of the available literature.

Additionally, there were limitations with our study that need to be addressed. This study was not preregistered (e.g., in PROSPERO), which limits independent verification of pre-specified methods. Nonetheless, the analyses were conducted according to a predefined plan established prior to data collection. Another limitation is that a formal risk-of-bias assessment (e.g., ROB-2, ROBINS-I or Newcastle-Ottawa Scale) was not performed. This decision was made because the included studies were heterogeneous in design and largely retrospective in nature, with only one study being an RCT. Reference Sousa, Pinto and da Silva27 However, the lack of a structured bias evaluation limits the ability to formally quantify the methodological quality of included studies. Some degree of bias cannot be excluded, and several bias domains should be acknowledged. Selection bias may exist due to the inclusion of mostly single-center observational studies, which could reflect differences in patient selection and perioperative management. Measurement bias may have been introduced by heterogeneity in how early and late mobilization were defined and by the use of different functional outcome scales (GOS, GOSE, mRS), which may have resulted in inconsistent classification of recovery status across studies. Reporting bias is also possible given the inconsistent documentation of complications and follow-up intervals. These factors collectively limit both the internal validity and external generalizability of our results and should be carefully considered when interpreting these results and the overall strength of evidence in the literature.

Another limitation is that we did not perform formal sensitivity analyses or quantitative exploration of heterogeneity, such as subgroup analyses or meta-regression. Because only four studies were eligible and differed substantially in design, definitions of mobilization and reported outcomes, these analyses were not methodologically feasible. However, the absence of such analyses limits the ability to assess how factors like study design and mobilization timing might have influenced the pooled results.

We propose that future research should prioritize several key areas. Future, ideally larger, multicenter RCTs that are sufficiently powered would help strengthen the evidence base to help provide more robust guidelines for clinicians. Second, the development and adoption of standardized definitions for the timing of mobilization, the definition of recurrence and which outcome measures are reported are crucial to maintain consistency in this field. As shown by the fact that all the included studies had different definitions of early and late mobilization, these definitions are poorly standardized. We propose that future studies aim to maintain similar definitions when describing different mobilization timings. Although recurrence is variably defined in the literature, we propose that clinically significant recurrences, including patients with neurological sequelae or those that require surgical intervention, be emphasized in future research. Reference Desai, Scranton and Britz34 Reporting outcomes using a clinically validated scale should be strongly considered to facilitate comparison of results between trials. We propose that future studies adopt the GOSE, with a score of ≥5 and ≥7 being defined as a moderate and good outcome, respectively, as a consistent functional endpoint to facilitate comparison between studies. This should be evaluated at both discharge and 30 days after surgery. This is consistent with the grading used by the GET-UP Trial. Reference Sousa, Pinto and da Silva27 Finally, we recommend that studies with follow-up periods beyond two months are needed to assess the long-term impact on recurrence and functional outcomes fully. This is in keeping with other cSDH studies that have followed patients over six months postoperatively. Reference Jeon, Rim and Lee35,Reference Martinez-Perez, Tsimpas, Rayo, Cepeda and Lagares36

The findings of this review suggest that EM compared to DM after surgical evacuation for cSDH is a safe and potentially beneficial strategy. Clinicians may consider incorporating EM into their postoperative protocols, particularly given the observed reduction in medical complications, which can significantly impact patient recovery and resource utilization. The absence of a clear increase in recurrence risk with EM is a key finding that can help overcome traditional hesitations.

Conclusion

In summary, this systematic review suggests that EM following surgical evacuation of cSDH is a safe and potentially beneficial strategy that may reduce postoperative medical complications and improve functional recovery without increasing recurrence rates. Clinicians may consider incorporating EM into their postoperative protocols, particularly given the observed reduction in medical complications, which can significantly impact patient recovery and resource utilization. The absence of a clear increase in recurrence risk with EM is a key finding that can help overcome traditional hesitations. While promising, the current evidence is limited by heterogeneity and methodological factors. Further high-quality research is necessary to refine optimal postoperative mobilization strategies for this common neurosurgical presentation.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2025.10514

Data availability statement

This project involves only publicly available data.

Author contributions

KO: Formal analysis, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Investigation. DC: Methodology, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Kelsey Cruz: Methodology, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. ADR: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Investigation. SM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Data curation, Investigation.

Funding statement

No funding support for this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical statement

Ethics approval was not required.

Target article

Early Versus Late Mobilization Following Chronic Subdural Hematoma Surgery: A Systematic Review

Related commentaries (1)

Reviewer Comment on Ong et al. “Early versus Late Mobilization Following Chronic Subdural Hematoma Surgery: A Systematic Review”