Introduction

Climate adaptation in agricultural systems presents a classic social dilemma where individual rational choices often conflict with collective welfare (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2009). In the context of saltwater inundation affecting rice farming systems in Southeast Asia, individual farmers may choose short-term protective measures that inadvertently exacerbate salinity problems for neighbouring farms, creating negative externalities that markets fail to price correctly (Fasting et al., Reference Fasting, Bacudo, Damen and Dinesh2021; Resurreccion et al., Reference Resurreccion, Sajor and Fajber2008; Touch et al., Reference Touch, Tan, Cook, Liu, Cross, Tran, Utomo, Yous, Grunbuhel and Cowie2024). Traditional top-down state interventions often fail due to enforcement limitations and information asymmetries, while purely market-based solutions cannot adequately address the collective action problems inherent in managing shared water resources (Berardo and Lubell, Reference Berardo and Lubell2016).

The Philippines and Viet Nam present an opportunity to investigate these issues, as these two countries are among the most threatened by sea level rise and saltwater inundation (The World Bank, 2021). Saltwater inundation in rice farms in Viet Nam is already well-studied because of the increasing frequency and scale. On the other hand, in the Philippines, saltwater inundation in rice farms remains mainly undocumented, especially in Northern Mindanao (Almaden et al., Reference Almaden, Diep, Rola, Baconguis, Pulhin, Camacho and Ancog2020). This study investigates how polycentric institutional arrangements can resolve this social dilemma by fostering collective adaptation to saltwater inundation in rice farming systems in the Philippines and Viet Nam.

Following Ostrom’s framework, this paper examines how multiple, overlapping governance structures, including farmer organisations, irrigation associations, and local government units, create institutional settings that encourage cooperation. However, as Ostrom herself acknowledged, ‘collective action is no panacea’ (Ostrom et al., Reference Ostrom, Janssen and Anderies2007). Success depends on specific institutional conditions that align individual incentives with collective outcomes (Roggero et al., Reference Roggero, Bisaro and Villamayor-Tomas2018a).

Research focus and theoretical foundations

Polycentric and meso-level Governance

Polycentric governance by Ostrom (Reference Ostrom2009) offers an alternative to both top-down state interventions and purely market-based solutions by recognising the existence of multiple, overlapping centres of authority, where decision-making is distributed across state agencies, local governments, civil society, and farmer organisations. Within this polycentric system, meso-institutions occupy a crucial intermediate role (Ménard and Martino, Reference Ménard and Martino2025). They function as transmission mechanisms that connect macro-level institutions such as national climate adaptation policies, environmental regulations, and agricultural development strategies with micro-level actors, including individual farmers and households (Garrick et al., Reference Garrick, Alvarado-Revilla, de Loë and Jorgensen2022; Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Wilson, Noble, Miller, Conway and Cureton2023; Sidibé et al., Reference Sidibé, Totin, Thompson-Hall, Traoré, Sibiry Traoré and Olabisi2018). By interpreting, translating, and adapting broad policies into operational guidelines, meso-institutions enable coherence between the overarching policy environment and the everyday practices of resource users (Ménard and Martino, Reference Ménard and Martino2025).

In the empirical analysis of this study, meso-level institutions are identified through their organisational manifestations (meso-level actors) while recognising that institutions represent the governance structures, rules, and norms that these actors enact and maintain. This distinction is important: institutions are the ‘rules of the game’, while actors are the ‘players’ who interpret and enforce those rules within polycentric governance systems. Meso-level actors include farmer cooperatives, irrigation associations, and local government units. These organisations interpret policies on water use, crop diversification, and risk reduction, and transform them into context-specific adaptation measures (Hien, Reference Hien2025). Their role is not limited to administrative translation but extends to facilitating negotiations between competing water users, resolving conflicts, and coordinating adaptation strategies across farming communities (Fasting et al., Reference Fasting, Bacudo, Damen and Dinesh2021; Shivakoti et al., Reference Shivakoti, Janssen and Chhetri2019).

Common-pool resources and collective action

As stated, this paper is grounded in Ostrom’s framework for managing common-pool resources through collective action within polycentric governance systems. Common-pool resources are characterised as rivalrous (subtractable) but non-excludable goods, such as irrigation water, shared drainage systems, and coastal protection infrastructure (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010a). In saltwater inundation contexts, these resources include shared water management systems where one farmer’s extraction or drainage decisions directly affect neighbouring farms’ access to fresh water and protection from salinity inundation (Su et al., Reference Su, Kambale, Tzeng, Amy, Ladner and Karthikeyan2025).

Common-pool resources, such as irrigation systems and shared dikes, are characterised by being rivalrous in nature yet non-excludable (Kassis, Reference Kassis2023). In contrast, public goods like climate information and early warning systems are both non-rivalrous and non-excludable. Finally, club goods, such as farmer cooperative membership benefits, are non-rivalrous among members but excludable to non-members, creating a middle ground between public and private goods where access is controlled but shared use does not diminish the resource (Hyman, Reference Hyman2010).

Rural farmers in many developing countries typically face resource constraints and uncertainties and require support in accessing and adopting appropriate climate change adaptation strategies (Acevedo et al., Reference Acevedo, Pixley, Zinyengere, Meng, Tufan, Cichy, Bizikova, Isaacs, Ghezzi-Kopel and Porciello2020; Agrawal and Gupta, Reference Agrawal and Gupta2005a; Antwi-Agyei et al., Reference Antwi-Agyei, Wiafe, Amanor, Baffour-Ata and Codjoe2021; Hause, Bradley K, Reference Hause2010; Liang et al., Reference Liang, Zhang, Li, Zhang and Frewer2021). Often, these farmers do not only rely on individual choice but mostly on networks that foster collective action (Kreft et al., Reference Kreft, Angst, Huber and Finger2023; Villamayor-Tomas et al., Reference Villamayor-Tomas, Sagebiel, Rommel and Olschewski2021), encompassing shared customs, ideas, beliefs, and institutional arrangements, to facilitate cooperation (Adeagbo et al., Reference Adeagbo, Ojo and Adetoro2021; Kehinde et al., Reference Kehinde, Adeyemo and Ogundeji2021; Mahmood et al., Reference Mahmood, Arshad, Mehmood, Faisal Shahzad and Kächele2021; Simon et al., Reference Simon, Krupnik, Aguilar-Gallegos, Halbherr and Groot2021). Collective action enables communities to address climate threats, both large and small in scale, to coordinate water management, share costs, and develop common strategies to mitigate risks (Deressa et al., Reference Deressa, Hassan, Ringler, Alemu and Yesuf2009; Ingold, Reference Ingold2017; Ogunleye et al., Reference Ogunleye, Kehinde, Mishra and Ogundeji2021). However, in many cases, collective action often intersects with farmers’ organisations, institutional structures, external actors, and government policies, resulting in complex polycentric governance systems, where multiple centres of authority interact in different scales (Goetz et al., Reference Goetz, Hussein and Thiel2024; Playán et al., Reference Playán, Sagardoy and Castillo2018).

Collective practices and routines

As Ostrom et al. (Reference Ostrom, Janssen and Anderies2007) stressed, collective action has limitations. Managing common-pool resources primarily requires the pursuit of the common good through institutionalised collective practices and collective routines (Albareda and Sison, Reference Albareda and Sison2019). Collective practices are deliberate, coordinated activities that farmers undertake together, such as synchronised planting schedules to optimise water use efficiency, joint construction and maintenance of shared drainage infrastructure, coordinated crop variety selection to minimise pest and disease spillovers, or collective water management during critical growth periods (Almaden et al., Reference Almaden, Rola, Baconguis, Pulhin, Camacho and Ancog2019; Baldwin et al., Reference Baldwin, McCord, Dell’Angelo and Evans2018; Sarasvathy and Ramesh, Reference Sarasvathy and Ramesh2019). Collective routines, by contrast, are institutionalised patterns of interaction embedded in governance structures over time, including regular irrigation association meetings to discuss water allocation, established protocols for monitoring salinity levels and sharing information, standardised procedures for resolving conflicts over water use, and habitual enforcement mechanisms for collective rules (Albareda and Sison, Reference Albareda and Sison2019; Baldwin et al., Reference Baldwin, McCord, Dell’Angelo and Evans2018; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Swann, Weible, Bolognesi, Krause, Park, Tang, Maletsky and Feiock2022a; Sarasvathy and Ramesh, Reference Sarasvathy and Ramesh2019).

Within this framework, scholars argue that embedding the common good and collective action into farm management practices is crucial for addressing sustainability challenges (Albareda and Sison, Reference Albareda and Sison2019; Brahm and Poblete, Reference Brahm and Poblete2024; Decaro et al., Reference Decaro, Schlager and Frimpong Boamah2025). However, following Ostrom’s caution, collective action succeeds only when institutions are adaptive, polycentric, and contextually grounded, rather than designed as one-size-fits-all mechanisms (Ostrom et al., Reference Ostrom, Janssen and Anderies2007). Berardo and Lubell (Reference Berardo and Lubell2016) extend this reasoning by showing that network structures of collaboration among actors can either enhance or constrain cooperation, depending on the balance between bonding and bridging ties. Similarly, institutional heterogeneity and asymmetrical power relations within governance networks can undermine trust and hinder coordination, even when collective platforms exist (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Swann, Weible, Bolognesi, Krause, Park, Tang, Maletsky and Feiock2022b; Villamayor-Tomas, Reference Villamayor-Tomas2018). These insights underscore that the effectiveness of collective action depends not merely on participation, but on the quality of relationships, governance rules, and information exchange that sustain cooperation over time (Berardo and Lubell, Reference Berardo and Lubell2016; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Swann, Weible, Bolognesi, Krause, Park, Tang, Maletsky and Feiock2022b; Ostrom et al., Reference Ostrom, Janssen and Anderies2007). Aligning individual and communal values remains essential to ensure that collective practices and routines lead to equitable and resilient outcomes (Bastakoti and Shivakoti, Reference Bastakoti and Shivakoti2011; Roggero et al., Reference Roggero, Bisaro and Villamayor-Tomas2018b; Villamayor-Tomas, Reference Villamayor-Tomas2018).

Collective action therefore represents a necessary but insufficient mechanism for effective adaptation in farming systems exposed to salinity risks. While individual responses such as adopting saline-tolerant rice varieties or installing farm-level drainage systems can provide temporary relief, they fail to address the shared and interconnected nature of water and salinity dynamics (Bergqvist et al., Reference Bergqvist, Holmgren and Rylander2012; Diep et al., Reference Diep, Trung, Nhung, Huong, Vu and Tuan2022). Collective coordination through synchronised cropping calendars, pooled resources for dike construction, or cooperative water management regimes can reduce transaction costs, create economies of scale, and enhance resilience against external shocks. Nevertheless, as Ostrom and others cautioned, sustaining such cooperation requires continuous investment in trust-building, learning, and adaptive institutional design to avoid collective failure (Baldwin et al., Reference Baldwin, McCord, Dell’Angelo and Evans2018; Bastakoti and Shivakoti, Reference Bastakoti and Shivakoti2011; Bodin et al., Reference Bodin, Baird, Schultz, Plummer and Armitage2020).

Communicative process

Drawing on polycentric governance theory, the paper posits that meso-institutions influence farmers’ preferences through three distinct mechanisms that operate through different communicative processes of collective action: extremist, multivocal, and deliberative, which shape how collective practices and routines unfold and impact polarised contexts (Fasting et al., Reference Fasting, Bacudo, Damen and Dinesh2021; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Swann, Weible, Bolognesi, Krause, Park, Tang, Maletsky and Feiock2022a; Liu, Reference Liu2010; Morgan and Olsen, Reference Morgan and Olsen2011; Morrison et al., Reference Morrison, Adger, Brown, Lemos, Huitema, Phelps, Evans, Cohen, Song, Turner, Quinn and Hughes2019; Shivakoti et al., Reference Shivakoti, Janssen and Chhetri2019).

Importantly, these processes are not mutually exclusive but can co-occur within the same institutional setting. Extremist communication involves polarised messaging that emphasises crisis urgency and creates clear in-group/out-group distinctions. In saltwater management contexts, this might involve crisis framing (‘saltwater inundation threatens our survival as rice farmers’) and binary choices (‘either we act collectively or suffer crop damages’). While effective for rapid mobilisation during crises, extremist communication may undermine long-term cooperation by reducing trust and flexibility. Multivocal communication accommodates diverse perspectives and allows multiple interpretations of collective goals, enabling broad participation while maintaining flexibility about specific commitments. This approach emphasises consensus-building across different farmer circumstances. Lastly, deliberative communication involves structured dialogue where participants engage in reasoned discussion about trade-offs, share information transparently, and seek mutually acceptable solutions through evidence-based reasoning. This includes transparent information sharing, systematic evaluation of adaptation options, and consensus through reasoning rather than power. Most studies suggest that deliberative processes are most likely to generate positive systemic effects by fostering inclusive dialogue and mutual understanding (Bellocchi et al., Reference Bellocchi, Rivington, Matthews and Acutis2015; Bodin et al., Reference Bodin, Baird, Schultz, Plummer and Armitage2020; Decaro et al., Reference Decaro, Schlager and Frimpong Boamah2025; Villamayor-Tomas et al., Reference Villamayor-Tomas, Sagebiel, Rommel and Olschewski2021; Zagaria et al., Reference Zagaria, Schulp, Zavalloni, Viaggi and Verburg2021).

Multilevel framework of deliberative preferences for collective adaptation

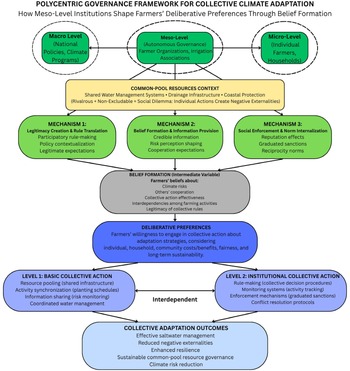

This study applies and extends Ostrom’s polycentric governance framework by explicitly examining the role of meso-level institutions in mediating between individual-level deliberative preferences and collective adaptation outcomes. While building on established multilevel institutional theory (Agrawal and Gupta, Reference Agrawal and Gupta2005b; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010b), the contribution of this study lies in empirically demonstrating how meso-institutional mechanisms operate in the specific context of agricultural climate adaptation, with a clear distinction between everyday management decisions at the farmer level and the meso-institutional structures that shape those decisions.

Deliberative preferences capture the willingness of farmers to engage in these collective measures. Unlike purely economic preferences, deliberative preferences emerge from participatory reasoning processes where farmers weigh costs, benefits, and trade-offs not only for themselves but also for their community (Bellocchi et al., Reference Bellocchi, Rivington, Matthews and Acutis2015; Holden and Quiggin, Reference Holden and Quiggin2017; Villamayor-Tomas et al., Reference Villamayor-Tomas, Sagebiel, Rommel and Olschewski2021). This paper argues that deliberative preferences do not form in isolation. These preferences are influenced by perceptions of fairness, trust in institutions, expected returns from cooperation, and alignment with broader cultural and social norms (Arbuckle et al., Reference Arbuckle, Morton and Hobbs2015; Kaasa and Andriani, Reference Kaasa and Andriani2022). Specifically, a multilevel meso-institution that shapes farmers’ inclination toward collective adaptation.

The First Level is Basic Collective Action which involves direct coordination among farmers to implement specific adaptation measures through: Resource Pooling evidenced by combining financial resources, labour, and equipment for measures beyond individual capacity; Activity Synchronisation which involves coordinated timing of farming activities to optimise collective outcomes; and Information Sharing focused on direct exchange of knowledge about salinity patterns and effective practices (Ansari et al., Reference Ansari, Wijen and Gray2013; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Baker, Ewing, Hemming, Kenney and Runge2023).

The Second Level integrates Institutional Collective Action, involving the creation and maintenance of governance structures that enable Level 1 activities through: Rule-Making by establishing legitimate procedures for collective decisions about adaptation strategies; Monitoring Systems by creating mechanisms to track environmental conditions and measure effectiveness; and Enforcement Mechanisms by developing graduated sanctions and incentive structures that maintain cooperation (Holden and Quiggin, Reference Holden and Quiggin2017; Oliveira and Schnaider, Reference De Oliveira and Schnaider2025; Vanschoenwinkel et al., Reference Vanschoenwinkel, Moretti and van Passel2020).

The framework recognises that Level 1 activities depend on Level 2 institutions for sustainability and effectiveness. Without legitimate governance structures, basic collective action often fails due to free-riding and coordination problems (Magesa et al., Reference Magesa, Mohan, Matsuda, Melts, Kefi and Fukushi2023; Mathias et al., Reference Mathias, Anderies, Baggio, Hodbod, Huet, Janssen, Milkoreit and Schoon2020; Su et al., Reference Su, Kambale, Tzeng, Amy, Ladner and Karthikeyan2025; Touch et al., Reference Touch, Tan, Cook, Liu, Cross, Tran, Utomo, Yous, Grunbuhel and Cowie2024). Conversely, institutional structures remain ineffective without concrete collective activities that generate tangible benefits (Berardo and Lubell, Reference Berardo and Lubell2016; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Swann, Weible, Bolognesi, Krause, Park, Tang, Maletsky and Feiock2022a; Ostrom et al., Reference Ostrom, Janssen and Anderies2007).

Three mechanisms of meso-institutional influence

The paper also furthers the notion that meso-institutions guide farmer behaviour through three distinct mechanisms.

Mechanism 1: Legitimacy creation and rule translation

Meso-institutions translate broad climate policies into locally legitimate rules through participatory processes (Jensen and Ménard, Reference Jensen and Ménard2024). Unlike simple policy implementation, this involves deliberative engagement where farmers participate in rule-making, creating perceived legitimacy that enhances voluntary compliance (Albareda and Sison, Reference Albareda and Sison2019; Baldwin et al., Reference Baldwin, McCord, Dell’Angelo and Evans2018).

Mechanism 2: Belief formation and information provision

Meso-institutions shape farmers’ perceptions of climate risks and interdependencies among farming activities (Bolognesi and Pflieger, Reference Bolognesi and Pflieger2024). They provide credible information that enables farmers to update their beliefs about collective action effectiveness and others’ cooperation likelihood (Caplin and Martin, Reference Caplin and Martin2011).

Mechanism 3: Social enforcement and norm internalisation

Meso-institutions create enforcement mechanisms based on reputation, reciprocity, and community sanctions rather than state coercion (Kahan, Reference Kahan2013; Wittek et al., Reference Wittek, van Bavel, Ellemers, van Hees, van der Lippe and Spears2025). These mechanisms coordinate behaviour by creating predictable expectations about others’ actions and consequences of non-compliance (Magesa et al., Reference Magesa, Mohan, Matsuda, Melts, Kefi and Fukushi2023; Touch et al., Reference Touch, Tan, Cook, Liu, Cross, Tran, Utomo, Yous, Grunbuhel and Cowie2024; Wittek et al., Reference Wittek, van Bavel, Ellemers, van Hees, van der Lippe and Spears2025).

Cristina Bicchieri’s Social Norms Theory supports the three mechanisms in that individuals follow norms because they hold both empirical expectations and normative expectations, creating conditional cooperation based on shared expectations rather than external enforcement (Bicchieri, Reference Bicchieri2006). In relation to this study, her framework explains how meso-level institutions shape farmers’ deliberative preferences for collective climate adaptation by influencing these expectations through credible information, participatory rule-making, and social enforcement. Thus, Bicchieri’s theory provides the cognitive foundation for understanding how information, trust, and legitimacy operate as mechanisms of collective behaviour within polycentric governance systems.

Figure 1 visualises the analytical framework of this paper, showing polycentric, meso-level governance as the enabling environment in which deliberative preferences for collective adaptation are pursued to combat slow-onset events like saltwater inundation.

Figure 1. Framework on polycentric and meso-level institutions shaping farmers’ deliberative preferences for collective adaptation.

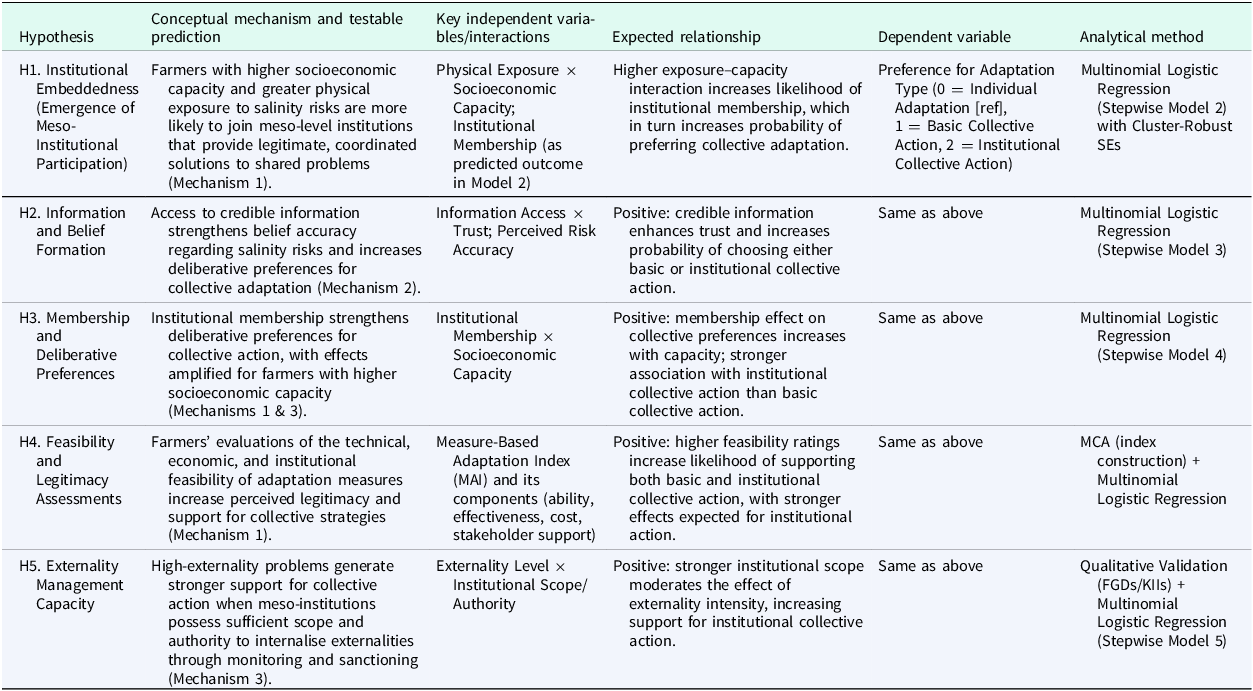

Research hypotheses

The hypotheses are organised into two categories consistent with the conceptual framework: (1) factors explaining the emergence of meso-institutional participation (H1), and (2) the effects of meso-institutions on belief formation, deliberative preferences, and support for collective adaptation (H2–H5). Each hypothesis corresponds directly to one or more of the three explanatory mechanisms in Figure 1.

H1 (Institutional embeddedness and emergence of participation)

Farmers facing higher levels of saltwater inundation risk and possessing greater socioeconomic capacity are more likely to join meso-level institutions (e.g., farmer organisations, irrigation associations), because these institutions provide legitimacy, rule translation, and coordinated solutions to shared problems that cannot be resolved individually (Mechanism 1).

H2 (Information provision and belief formation)

Farmers with access to credible information delivered through meso-institutions will form more accurate beliefs about climate risks, cooperation expectations, and the effectiveness of collective action, strengthening their deliberative preferences for collective adaptation (Mechanism 2).

H3 (Institutional membership × socioeconomic capacity interaction)

Membership in meso-level institutions strengthens farmers’ deliberative preferences for collective adaptation, and this effect is amplified for farmers with greater socioeconomic capacity, who benefit more from legitimacy creation, rule contextualisation, and norm internalisation provided by meso-institutions (Mechanisms 1 and 3).

H4 (Feasibility, legitimacy, and institutional support)

Farmers’ assessments of the technical feasibility, economic viability, and institutional legitimacy of adaptation options, shaped in part by meso-institutions’ role in policy contextualisation and participatory rule-making, will significantly correlate with their deliberative preferences for collective adaptation (Mechanism 1).

H5 (Scope of meso-institutions and externality management)

Collective adaptation measures that generate significant interdependencies or externalities will receive stronger farmer support when meso-institutions possess sufficient scope and authority to internalise externalities through monitoring, social enforcement, and reciprocity-based norms (Mechanism 3).

This research contributes to understanding climate adaptation governance by: (1) providing empirical evidence on how polycentric governance operates in practice, (2) developing methods for measuring deliberative preferences and their relationship to collective action, and (3) generating policy insights for designing effective meso-level institutions in developing country contexts.

Methodology

Study sites

The research was conducted in two highly vulnerable rice-farming regions: Plaridel, Misamis Occidental in Northern Mindanao, Philippines, where ten coastal barangays lie only 1–4 meters above sea level and are highly exposed to recurrent coastal flooding and saline inundation, and two districts in Ben Tre and Tra Vinh provinces in the Mekong Delta, Viet Nam, both low-lying areas averaging about 1.5 meters in elevation and prone to salinity from sea-level rise and riverine flooding. Projections from the Climate Change Research Institute indicate that up to 51% of Ben Tre Province could experience more frequent flooding under a 1-meter sea-level rise scenario. These shared hydrological pressures underscore the collective action challenges faced by rice farmers in both countries.

Data collection

A mixed-methods exploratory-sequential approach combined quantitative and qualitative data (Creswell and Creswell, Reference Creswell and Creswell2022). Structured questionnaires were administered through face-to-face interviews in the Philippines and Viet Nam, aided by the Kobo Toolbox Software using mobile Android devices.

Qualitative data were first collected to provide contextual depth and practical knowledge in the development of the questionnaire. The same methods were applied to triangulate the survey findings. In the Philippines, six focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted, each involving 8 to 12 participants, for a total of 58 participants. In Viet Nam, 2 FGDs were held, each with 10-12 participants, totalling 22 participants. Participants were purposively selected to ensure variation in institutional membership status and adaptation experience.

In addition, 15 key informant interviews (KIIs) were conducted: 12 in the Philippines (four agricultural officers, four irrigation association leaders, and four local government officials) and 3 in Viet Nam (1 agricultural officer, 1 farmers’ association leader, and 1 rice production researcher). These qualitative interviews provided insights into institutional arrangements, adaptation practices, and policy environments relevant to rice production in coastal communities.

Secondary data were primarily sourced from the Department of Agriculture (DA) Region 10 and the Municipal Agriculture Office of Plaridel, Misamis Occidental in the Philippines, as well as the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD), provincial Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (DARDs) and local authorities in Viet Nam.

Qualitative phase and survey development

Insights from the FGDs and KIIs in the Philippines and in Viet Nam, were used to: (i) identify adaptation measures farmers use at individual, communal, and institutional levels; (ii) map meso-level institutions (irrigation associations, farmer organisations, cooperatives); (iii) understand information channels, credibility issues, local rules, and enforcement practices; (iv) generate items for evaluating adaptation feasibility, legitimacy, enforcement, and coordination needs. These qualitative inputs directly informed the survey design, ensuring operationalisation of the conceptual mechanisms (legitimacy, information credibility, and social enforcement) through measurable indicators.

Survey instrument structure

Although the full questionnaire contained multiple modules, this study utilised only six of them: (i) household and farm characteristics (age, education, land size, tenure, income, farming inputs, etc.); (ii) physical exposure to climate and salinity events (frequency/severity of saline inundation, floods, droughts, riverine flooding in 5-point scales); (iii) institutional membership and participation (membership in farmer groups, irrigation associations, extent of involvement, rule compliance, and sanctions); (iv) information access and trust (access to extension services, local government, mass media, peer networks; credibility and usefulness ratings in Likert scales); (v) feasibility evaluation of adaptation measures (ratings for each measure on ability, effectiveness, cost, and stakeholder support which are inputs to the Measure-based Adaptation Index (MAI)); and (vi) deliberative preferences (Likert-scale questions on different strategies to coordinate planting schedules, participate in community-based adaptation, and other collective measures). All items were pre-tested, refined for clarity, and translated into the vernacular language for cultural appropriateness.

Sampling

A total of 584 farmers were surveyed across the Philippines and Viet Nam, comprising 326 respondents from the Philippines and 258 from Viet Nam. The analytical sample size remained stable across all models because only minimal missing data were observed. In the Philippines, 314 farmers (96.31%) provided complete responses; eight cases (2.45%) had missing data on the MAI components, and four cases (1.23%) had missing data on institutional membership. In Viet Nam, 241 farmers (93.41%) provided complete responses; nine cases (3.49%) had missing MAI components, and eight cases (3.10%) had missing institutional membership data. After excluding cases with missing values on key variables, the final analytical sample consisted of 555 farmers, representing a 95.03% usable response rate. Non-response diagnostics further showed that the missing data were missing completely at random (Little’s MCAR test: χ2 = 12.34, p = 0.42), with no significant associations between non-response and demographic or farm characteristics (age, education, farm size).

A cluster sampling design was employed in both countries. In the Philippines, the survey was conducted in 10 coastal barangays in Plaridel, Misamis Occidental, while in Viet Nam, 12 communes were selected across two districts in Ben Tre and Tra Vinh provinces, resulting in a total of 22 clusters. The sampling followed a three-stage procedure: (1) purposive selection of highly vulnerable coastal areas, (2) random selection of barangays or communes using probability proportional to size, and (3) systematic random sampling of farmers within each cluster based on local farmer registries. This design ensured representation of farming households across varying exposure and institutional contexts.

Data analysis

Variables and measurement

The study’s dependent variable, collective adaptation preference, was conceptualised following a two-level collective action framework that distinguishes between progressively more institutionalised forms of cooperation. Farmers were classified into three mutually exclusive categories reflecting their preferred mode of adaptation.

-

1. Individual adaptation only: Farmers in this category preferred exclusively private measures undertaken within their own farms, such as private dikes, individual crop variety choices, and farm-level water and soil management. These measures require no explicit coordination, shared rules, or joint decision-making with other farmers.

-

2. Basic collective action (Level 1): This category captures farmers who favoured low-intensity, community-based coordination that does not rely on formalised governance structures. Basic collective action is characterised by informal agreements or loose coordination (e.g. aligning planting dates with neighbours, joint cleaning of canals); short-lived or ad hoc initiatives; minimal or no codified rules; shared resource use or cost-sharing arrangements (e.g. small shared dikes, pooled labour); and reliance on social norms and reciprocity rather than structured monitoring and sanctions. In basic collective organisation, interdependence is recognised but handled through local conventions and mutual understanding rather than through formal meso-level institutions.

-

3. Institutional collective action (Level 2): This category refers to farmers who supported governance-intensive collective measures embedded in more formal organisations. Institutional collective action has distinct attributes: presence of meso-level organisations (e.g. irrigators’ associations and cooperatives) with recognised mandates; participatory rule-making for water allocation, land use, or dike operation; formal or semi-formal rules, recorded agreements, and procedures; explicit monitoring mechanisms (e.g. committees, patrols, record-keeping); sanctioning systems for non-compliance (fines, exclusion, loss of privileges); and greater spatial and temporal scope (e.g. coordination across several canals or barangays, multi-season planning). Institutional collective organisation thus differs from basic collective organisation not only in degree but in kind: it introduces formalised authority, monitoring, and enforcement capacities that allow management of high-externality problems and more complex interdependencies.

While these three categories can be conceptually arranged to reflect increasing levels of interdependence and institutional complexity, they are not ordinal in a strict statistical sense. Rather, they represent qualitatively distinct governance modes.

The principal independent variable, deliberative preferences, was defined as farmers’ expressed willingness to engage in collective action about adaptation strategies. This construct captures the extent to which individuals weigh not only their own private costs and benefits but also broader community outcomes. It was measured using a five-point Likert format. Reliability tests indicated satisfactory internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α = 0.78 for the Philippines and α = 0.81 for Viet Nam. Factor analysis was used. These items were factor-analysed to confirm unidimensionality; loadings exceeded 0.70, and Cronbach’s α ranged from 0.78–0.81. The resulting scale score feeds directly into the regression models.

This research also formulated the Physical Exposure Index (PEI) for the various climate-related events to indicate the varying frequency, intensity, and manageability. To determine the PEI on the number of weather-related changes perceived by the farmers with the indicators of change, an index adapted from the study of (Below et al., Reference Below, Mutabazi, Kirschke, Franke and Sieber2012) was developed. The PEI was modified and expressed as:

$${\rm{PE}}{{\rm{I}}_{\rm{j}}} = {1 \over m}\mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^m {{{C_{ij}} - {\overline {C}_i}{\rm{\;\;\;}}} \over {{\rm{\sigma }}{C_i}}}$$

$${\rm{PE}}{{\rm{I}}_{\rm{j}}} = {1 \over m}\mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^m {{{C_{ij}} - {\overline {C}_i}{\rm{\;\;\;}}} \over {{\rm{\sigma }}{C_i}}}$$

where:

![]() ${\overline {C}_{ij}}$

perception score of respondent j for climate-related event;

${\overline {C}_{ij}}$

perception score of respondent j for climate-related event;

![]() ${\overline{C}_{i}}$

mean perception score for climate-related event i across all respondents;

${\overline{C}_{i}}$

mean perception score for climate-related event i across all respondents;

![]() ${\rm{\sigma }}{C_i}$

standard deviation of perception scores for event i; m is the total number of climatic events.

${\rm{\sigma }}{C_i}$

standard deviation of perception scores for event i; m is the total number of climatic events.

The PEI reflects farmers’ perceived frequency and intensity of climate-related events and therefore captures subjective exposure.

To evaluate adaptation measures, a MAI was developed using multi-criteria analysis (MCA). Farmers rated each adaptation measure’s feasibility across four criteria: (i) ability to implement, (ii) effectiveness, (iii) cost, and (iv) stakeholder support. Ratings were converted into Adaptation Weights (AW) and combined with farmers’ reported adoption levels to compute Adaptation Scores (AS). The scores were aggregated into the MAI, which was standardised to range from 0 to 1. This provided a structured metric for comparing the feasibility and adoption of individual versus collective adaptation measures. Reliability was checked using Cronbach’s alpha.

The Adaptation Weight (AW) for each measure is obtained by dividing the average rating for each feasibility criterion of the j th respondent by the most desirable score of each criterion and getting the sum for all standards divided by the total number of measures, thereby reducing the score to a scale of 0 ≤ AS ≤ 1. This expressed as

where: AWij: represents the Adaptation Weight for the j th household for a given measure i; i: the measure employed; j: individual farming household; k: Total measures employed; A: Ability of the farmer to implement the measure; E: Effectiveness of the measure; C: Cost of implementing the measure; S: Level of support from major stakeholders; T: the total number of criteria (T = 4).

Equal weights were assigned to the four criteria of adaptation measures to ensure analytical neutrality and avoid subjective bias. This assumes that each criterion represents an essential and complementary dimension of adaptation feasibility, with no single factor dominating the assessment. In the absence of empirical or stakeholder-based evidence to justify differential weighting, equal allocation provides a balanced and comparable basis for evaluating farmers’ evaluations across measures and study sites (Philippines and Viet Nam). This approach aligns with standard practices in composite index construction, offering a transparent and normative baseline before applying expert- or data-driven weighting schemes in future analyses.

To determine the Adaptation Score of the farmer for each measure, the adaptation level is multiplied by the adaptation weight. The resulting Adaptation Score follows a scale 0 ≤ AL ≤ 1.

where: AS ij : represents the Adaptation Score for the j th farmer for a given measure i; i: the measure employed; j: individual rice-farming household.

Individual scores for each measure were combined into a final score for the MAI. The index was calculated as the sum of the weighted adaptation measures of the household. This is expressed as

where: MAIij = Measure-based adaptation index of rice-farming household j for all the; i measures employed from 1 – n; i: the measure employed; j: individual rice-farming household; n = the last i measure employed by the jth rice farming household; ALij = jth rice farming household’s value for a given i measure employed (0 ≤ AL ≤ 1); AW ij = weighting factor for each adaptation measure i employed by the jth rice-farming household; it is therefore necessary to standardise each as an index using the equation:

Internal consistency for each component was acceptable. For the Philippine sample, Cronbach’s α coefficients were 0.82 for the ability to implement, 0.85 for the effectiveness assessment, 0.81 for the cost evaluation, and 0.84 for the stakeholder support. For Viet Nam, the corresponding values were 0.79, 0.78, 0.73, and 0.76, respectively. The overall MAI demonstrated strong internal reliability (α = 0.83 in the Philippines; α = 0.76 in Viet Nam), indicating its robustness as a multidimensional measure of farmers’ evaluative judgments of adaptation strategies. Together, these measures provide an integrated empirical basis for examining how deliberative orientations and evaluative perceptions of adaptation measures shape farmers’ collective adaptation preferences across varying institutional contexts.

Statistical analyses

Multinomial logistic regression was estimated separately for the Philippines and Viet Nam with ‘Individual Adaptation Only’ as the reference category, examining factors influencing preferences for Basic Collective Action and Institutional Collective Action. All models use cluster-robust standard errors clustered at the barangay/commune level to account for intra-cluster correlation.

The multinomial logit (MNL) model estimates, for each farmer I in cluster c:

where:

![]() $j$

= 1 (Basic Collective Action), 2 (Institutional Collective Action);

$j$

= 1 (Basic Collective Action), 2 (Institutional Collective Action);

![]() ${X_i}$

= exposure, capacity, institutional membership; Z

i

= belief formation and trust variables; W

i

= feasibility/MAI variables and externality interactions.

${X_i}$

= exposure, capacity, institutional membership; Z

i

= belief formation and trust variables; W

i

= feasibility/MAI variables and externality interactions.

Standard error clustered by barangay/commune (22 clusters)

This structure mirrors the conceptual mechanisms:

-

Mechanism 1 (legitimacy): operationalised through the MAI and the institutional membership variable.

-

Mechanism 2 (information): captured through the interaction between information access and trust.

-

Mechanism 3 (social enforcement and norm internalisation): reflected in the interaction between institutional membership and socioeconomic capacity, as well as the interaction between externality intensity and institutional scope.

Choice of model

Given the three-category dependent variable and the conceptual discussion above, the outcome is categorical but not ordinal. Farmers choose among distinct governance modes rather than moving along a single latent ‘more collective’ continuum. To test whether an ordinal model would nevertheless be appropriate, the proportional odds (parallel lines) assumption was assessed. For both the Philippines and Viet Nam, the test produced significant results (Philippines: χ² = 47.3, p < 0.001; Viet Nam: χ² = 52.1, p < 0.001), indicating that the effects of predictors on cumulative logits are not constant. This rejects the proportional odds assumption and rules out ordinal logistic regression. Instead, MNL models were estimated separately for each country, with ‘Individual adaptation only’ as the reference category. The MNL framework allows the effect of key mechanisms: exposure, capacity, institutional membership, information, deliberative preferences, and MAI, to differ across the two collective categories (basic and institutional), consistent with the theoretical expectation that these mechanisms guide distinct governance modes in non-monotonic ways. The Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives (IIA) assumption was evaluated using Hausman–McFadden and Small–Hsiao tests and was not rejected (p > 0.10), supporting the use of the MNL specification.

Stepwise modelling and interaction terms

To avoid over-parameterisation, empty cells, and non-estimable interaction terms, a stepwise, theoretically informed modelling strategy was adopted:

-

Model 1 (baseline): main effects only (PEI, socioeconomic capacity, institutional membership, information access, trust, MAI, and relevant controls);

-

Model 2: adds Physical Exposure × Socioeconomic Capacity (H1 – emergence and embeddedness);

-

Model 3: adds Information Access × Trust (H2 – information and belief formation);

-

Model 4: adds Institutional Membership × Socioeconomic Capacity (H3 – membership and capacity interaction);

-

Model 5: adds Externality level × Institutional Scope/Authority (H5 – externality management).

Each block of interaction terms is evaluated separately to maintain estimability and to directly correspond to the hypothesised mechanisms. Interactions that produced quasi-complete separation, empty cells, or convergence problems in preliminary models were excluded or simplified, and this is noted in the Results section where relevant. Table 1 presents the explanatory variables and their expected relationship with model j.

Collinearity diagnostics

Multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIFs) and condition indices for all continuous predictors and their interaction terms. VIF values for retained variables remained below 5, indicating acceptable levels of collinearity. Where preliminary diagnostics suggested high collinearity (especially for interaction terms involving strongly correlated components), variables were mean-centred or rescaled before forming interactions. Interaction terms that continued to cause instability despite centring were dropped from the final model specification.

Results and discussion

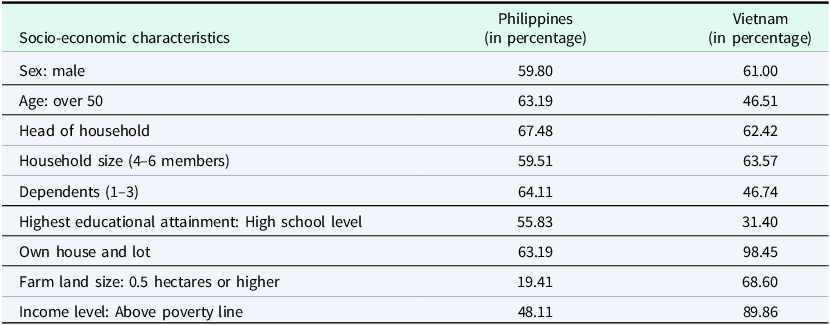

Farmers’ socio-economic characteristics and context

Table 2 present the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of rice farmers in the Philippines and Vietnam. Across both countries, surveyed farmers fall predominantly in the 51–65 age group, with limited formal education, wherein 56% of Filipinos and 31% of Vietnamese farmers report elementary or high school completion. Landholding disparities are evident: Filipino farmers cultivate an average of 0.3 ha with only one successful crop cycle annually, whereas Vietnamese farmers manage 1–2 ha and often achieve three cycles. Consequently, yields diverge substantially: over 90% of Filipino farmers report yields below 50% of expected output, while Vietnamese farmers attain roughly 80%. These structural disadvantages lend support to the data on Filipino farmers’ incomes, which situate them closer to the poverty line, underscoring the socio-economic vulnerability that frames subsequent adaptation choices.

The results show broad demographic similarity (gender, household size, marital status) but large structural socioeconomic differences. Philippine farmers are older, have smaller landholdings, and lower incomes, positioning them closer to the poverty line. Vietnamese farmers generally possess larger farms, more stable infrastructure, and higher household assets (e.g., housing ownership). Education levels are higher in the Philippines, but Vietnamese farmers have stronger asset security, which aligns with more formalised agricultural systems. These differences justify the separate country-level multinomial estimations and help explain why mechanisms operate differently across contexts (e.g., stronger legitimacy and social enforcement effects in the Philippines, greater state-anchored trust in Viet Nam).

This context is critical because it shapes not only farmers’ risk exposure but also their capacity to engage in collective or individual adaptation pathways. It establishes the background against which the paper assesses the hypotheses.

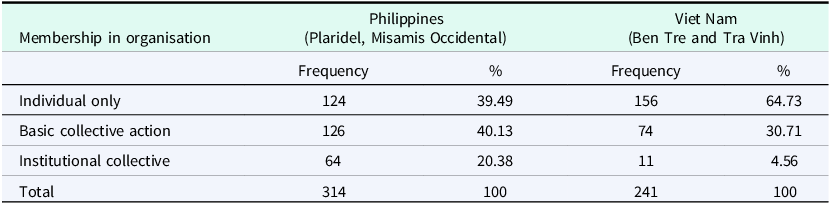

H1: Institutional embeddedness and emergence of participation

Membership patterns diverge sharply (Table 3). In the Philippines, 60% of respondents belong to either farmer associations, irrigation cooperatives, or informal ‘cabicilla’ groups. These affiliations facilitate structured irrigation management and local adaptation coordination. Conversely, only 35% of Vietnamese farmers report formal membership, with reliance instead on the People’s Committee or Farmers’ Association for mobilisation. FGDs revealed frequent difficulties in reaching consensus, highlighting weaker meso-level structures.

The multinomial logistic regression results indicate that the model fits the data well and provides meaningful insights into the predictors. Sensitivity analyses using wild-cluster bootstrap (Rademacher, G = 22) produced consistent p-values across models (p < 0.05 for key effects). Additionally, propensity score weighting (IPW/AIPW) and leave-one-cluster-out tests confirmed stability of the coefficients, with average partial effects varying by less than 5%. These specifications and robustness tests collectively support the validity and stability of the multinomial model used in the analysis. Oster’s δ values for the membership and interaction effects ranged from 1.8 to 2.6, indicating that unobserved selection would need to be nearly twice as strong as observed factors to nullify results, while Rosenbaum bounds (Γ = 1.9–2.3) confirmed resilience to moderate hidden bias. These specifications and robustness tests collectively support the validity and stability of the multinomial model used in the analysis.

Model diagnostics further confirmed acceptable model fit and classification performance. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) values indicated improved fit for the full model (Philippines: AIC = 1,082.47, BIC = 1,194.22; Viet Nam: AIC = 974.63, BIC = 1,068.51) compared to the baseline intercept-only model. Classification accuracy reached 71.4% for the Philippines and 69.8% for Viet Nam, substantially exceeding the proportional by-chance accuracy rates of 42% and 40%, respectively, suggesting the model reliably predicts adaptation preferences.

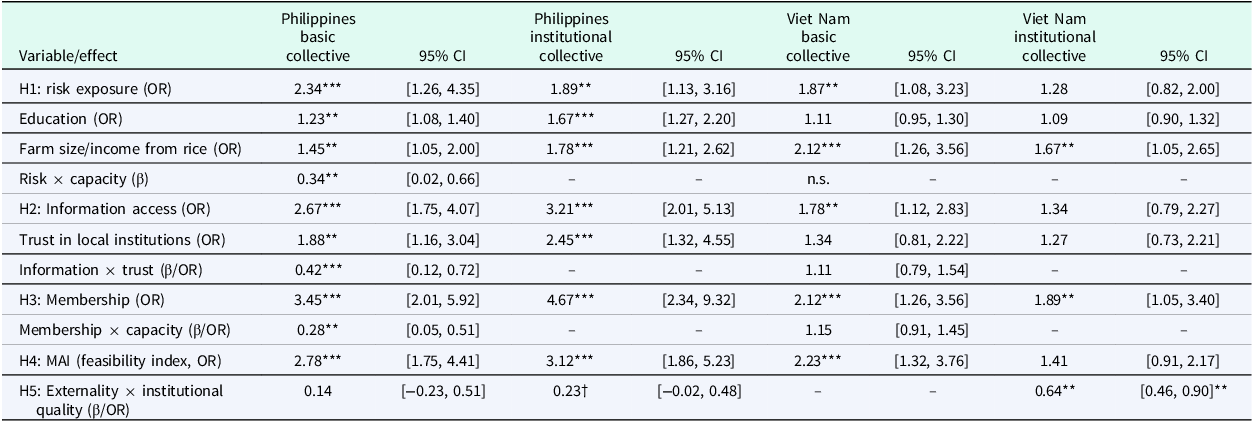

The multinomial logistic regression results provide strong support for Institutional Embeddedness, which demonstrates that farmers exposed to higher saltwater inundation risks and possessing greater socioeconomic capacity are more likely to participate in meso-level institutions that facilitate collective adaptation. In the Philippines’ model (Pseudo R² = 0.451), physical exposure emerged as a significant determinant of both Basic Collective (Odds Ratio [OR] = 2.34, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.26–4.35) and Institutional Collective preferences (OR = 1.89, 95% CI: 1.13–3.16), indicating that farmers perceiving greater climate-related risks are more inclined toward collective adaptation measures. Education exerted a stronger correlation on Institutional Collective choices (OR = 1.67, 95% CI: 1.27–2.20) compared with Basic Collective action (OR = 1.23, 95% CI: 1.08–1.40), suggesting that more educated farmers are better able to engage with and benefit from institutionalised forms of cooperation. Farm size also displayed a positive association with both forms of collective adaptation (Basic: OR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.05–2.00; Institutional: OR = 1.78, 95% CI: 1.21–2.62), reflecting the capacity of larger landholders to absorb risks and invest in cooperative mechanisms.

The multinomial logistic regression results provide strong support for Institutional Embeddedness, which demonstrates that farmers exposed to higher saltwater inundation risks and possessing greater socioeconomic capacity are more likely to participate in meso-level institutions that facilitate collective adaptation. In the Philippines’ model (Pseudo R² = 0.451), physical exposure emerged as a significant determinant of both Basic Collective (Odds Ratio [OR] = 2.34, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.26–4.35) and Institutional Collective preferences (OR = 1.89, 95% CI: 1.13–3.16), indicating that farmers perceiving greater climate-related risks are more inclined toward collective adaptation measures. Education exerted a stronger correlation on Institutional Collective choices (OR = 1.67, 95% CI: 1.27–2.20) compared with Basic Collective action (OR = 1.23, 95% CI: 1.08–1.40), suggesting that more educated farmers are better able to engage with and benefit from institutionalised forms of cooperation. Farm size also displayed a positive association with both forms of collective adaptation (Basic: OR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.05–2.00; Institutional: OR = 1.78, 95% CI: 1.21–2.62), reflecting the capacity of larger landholders to absorb risks and invest in cooperative mechanisms.

In contrast, the Viet Nam model (Pseudo R² = 0.396) showed that risk exposure significantly predicted Basic Collective preferences (OR = 1.87, 95% CI: 1.08–3.23) but not Institutional Collective action, indicating a greater reliance on local action, rather than formalised, cooperation under moderate risk conditions. Education effects were weaker and statistically less robust across both collective categories, while income derived from rice farming was a strong predictor of collective preferences (OR = 2.12, 95% CI: 1.26–3.56), implying that farmers with higher livelihood dependence on rice production are more motivated to engage in cooperative risk management.

The interaction between risk exposure and socioeconomic capacity further underscores the differentiated dynamics between the two countries. In the Philippines, the interaction term was statistically significant (β = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.02–0.66), indicating that greater socioeconomic capacity amplifies the effect of perceived risk on collective action preference. In Viet Nam, however, the interaction was not significant, suggesting that risk perception and capacity operate independently rather than synergistically. At the field level, there is a noticeable shift away from traditional support systems involving residential neighbours, farm neighbours, and relatives. Farmers have increasingly favoured individual approaches to crop cultivation over collective efforts. This shift highlights a broader trend toward individualisation, where personal responsibility for farming decisions has become more prevalent, diminishing the perceived utility of traditional cooperative support systems. This trend is in contrast with the findings from the Philippines, where informal networks such as ‘cabicilla’ groups remain crucial for local coordination and adaptation (Howard-Grenville et al., Reference Howard-Grenville, Buckle, Hoskins and George2014; Phung et al., Reference Phung, Bertels, Ansari, Hoffman, Howard-Grenville and Zietsma2020).

These findings confirm H1 and reveal important cross-country differences in how exposure and capacity shape institutional engagement. In the Philippine context, collective adaptation is driven by both vulnerability and capacity, reflecting a co-dependent mechanism consistent with polycentric adaptation theory, whereas in Viet Nam, collective action appears to arise primarily from risk exposure alone, highlighting the persistence of more localised, less institutionalised forms of cooperation.

H2: Information provision and belief formation

The analysis confirms that access to credible information through meso-institutional channels significantly increases the likelihood of collective adaptation preferences. In the Philippines, information access had a strong and statistically significant correlation on both Basic Collective (OR = 2.67, 95% CI [1.75, 4.07]) and Institutional Collective preferences (OR = 3.21, 95% CI [2.01, 5.13]). In Viet Nam, the effects were more moderate, significant for Basic Collective adaptation (OR = 1.78, 95% CI [1.12, 2.83]) but weaker and non-significant for Institutional Collective action (OR = 1.34, 95% CI [0.79, 2.27]). Trust in local institutions was also a key determinant, particularly in the Philippines, where it significantly predicted institutional collective preferences (OR = 2.45, 95% CI [1.32, 4.55]). By contrast, trust had weaker and statistically inconsistent effects in Viet Nam. The interaction between information access and trust further reinforces this mechanism: in the Philippines, a significant positive interaction (β = 0.42, 95% CI [0.12, 0.72]) indicates that information access is amplified in high-trust contexts, whereas in Viet Nam, the interaction was non-significant, suggesting independent operation of the two variables. Survey data show that informal networks (friends, relatives, neighbours) are the primary information source in both countries. However, information ecosystems differ: Philippine farmers rely on mass media (e.g., television), while Vietnamese farmers place greater trust in government channels. Despite this, Vietnamese FGDs revealed scepticism about monitoring outcomes, particularly regarding government-led irrigation and dike projects. These findings support Mechanism 2 (Belief Formation), emphasising that information access fosters collective preferences most effectively when trust in meso-institutions is high.

H3: Institutional membership × socioeconomic capacity interaction

The results demonstrate that institutional membership substantially strengthens collective adaptation preferences, with effects interacting with farmers’ socioeconomic capacity. In the Philippines, membership strongly increased the odds of both Basic Collective (OR = 3.45, 95% CI [2.01, 5.92]) and Institutional Collective preferences (OR = 4.67, 95% CI [2.34, 9.32]). In Viet Nam, the effects were significant but more modest (Basic: OR = 2.12, 95% CI [1.26, 3.56]; Institutional: OR = 1.89, 95% CI [1.05, 3.40]). The interaction between membership and socioeconomic capacity was significant in the Philippines (β = 0.28, 95% CI [0.05, 0.51]), indicating that higher-capacity farmers benefit more from institutional affiliation, whereas the effect was weaker in Viet Nam. Results show that Filipino farmers are highly motivated to join associations to buffer risks based on their socio-economic conditions. In contrast, Vietnamese farmers with larger landholdings and diversified income streams express greater ambivalence toward collective action. These results confirm H3, suggesting that membership plays a central role in developing deliberative preferences, especially where meso-institutions function autonomously from state direction. They are consistent with Mechanism 1 (legitimacy creation and rule contextualisation) and Mechanism 3 (social enforcement and reciprocity norms), which jointly strengthen deliberative preferences among members of meso-level institutions.

H4: Feasibility, legitimacy, and institutional support

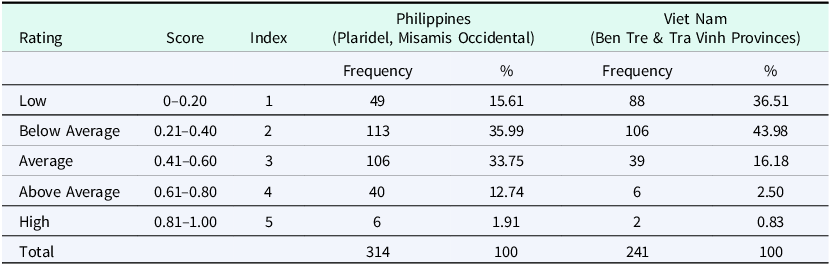

MAI results for the Philippines showed mostly Below Average (35.99%) to Average (33.75%) scores. Viet Nam had higher shares in Below Average (43.98%) and Low levels (36.51%), reflecting generally lower performance (Table 4). The findings reveal that farmers’ evaluations of the feasibility of adaptation measures are substantially associated with their collective adaptation choices. Higher MAI scores were associated with significantly greater odds of preferring both Basic Collective (OR = 2.78, 95% CI [1.75, 4.41]) and Institutional Collective adaptation (OR = 3.12, 95% CI [1.86, 5.23]) in the Philippines, and Basic Collective preferences (OR = 2.23, 95% CI [1.32, 3.76]) in Viet Nam. In supplementary models where the MAI components were analysed separately, the legitimacy/support dimension consistently showed a positive association with collective preferences, the cost component exhibited a negative association, and the effectiveness dimension had a stronger positive effect in the Philippines. These supplementary findings help interpret farmers’ feasibility evaluations but are not included in the main multinomial models reported in Table 5, which use only the aggregated MAI index to avoid collinearity with its components.

Table 1. Explanatory variables and their expected relationship with model j

Table 2. Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of rice farmers, Philippines and Viet Nam

Table 3. Farmers’ membership in organisations for the implementation of adaptation measures, Philippines and Viet Nam

Table 4. Measure-based adaptation index scores of rice farmers, Philippines and Viet Nam

Table 5. Multinomial logistic regression results for collective adaptation preferences, Philippines and Vietnam. Reference category: Individual Adaptation Only. Estimator: Cluster-robust standard errors (22 clusters)

Model Diagnostics:

Philippines: χ²(11) = 118.5, p < 0.001; Pseudo R² = 0.451; N = 314.

Vietnam: χ²(11) = 102.8, p < 0.001; Pseudo R² = 0.396; N = 241.

* Significance levels: p < 0.10 = †; p < 0.05 = *; p < 0.01 = **; p < 0.001 = **.

Note: Odds ratios (OR) are reported for all main effects. Philippine interaction terms are reported as logit coefficients (β) with their 95% confidence intervals. Viet Nam interaction terms are reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals for consistency with the table’s reporting structure.

H5: Scope of meso-institutions and externality management

The results demonstrate that collective support for adaptation measures varies depending on the externality level and institutional capacity. Low-externality measures such as water dilution and seed sharing received high collective support in both countries, with particularly strong preference rates in the Philippines (78% Basic, 65% Institutional) compared to Viet Nam (56% Basic, 34% Institutional). For high-externality measures like dike construction and drainage systems, Philippine farmers still expressed moderate collective preferences (45% Basic, 67% Institutional), while Vietnamese farmers reported much lower support (23% Basic, 31% Institutional). The interaction between externality level and institutional quality was non-significant in the Philippines, implying that well-functioning institutions manage both externality levels effectively. In contrast, Viet Nam showed a significant negative interaction (OR = 0.64, 95% CI [0.46, 0.90]), suggesting that higher externalities reduce collective support. Hence, H5 is partially supported, highlighting that institutional authority and scope are decisive for managing high-externality adaptation measures in weaker governance contexts. This aligns with the hypothesis that the capacity of meso-level institutions to internalise externalities through monitoring and enforcement (Mechanism 3) is critical for sustaining collective support.

The cross-country comparison of mechanisms provides a deeper understanding of how polycentric governance operates. In the Philippines, Legitimacy Creation (Mechanism 1) was pronounced, with participatory rule-making showing strong effects (OR = 2.89, 95% CI [1.67, 4.99]), whereas in Viet Nam, the effect was weaker (OR = 1.45, 95% CI [1.02, 2.06]). Belief Formation (Mechanism 2) was robust in the Philippines, reflected in significant information × trust interactions, while in Viet Nam, information effects occurred independently of trust. Social Enforcement (Mechanism 3) was also stronger in the Philippines (OR = 2.34, 95% CI [1.34, 4.08]) than in Viet Nam (OR = 1.67, 95% CI [1.05, 2.65]), showing that reputation-based enforcement mechanisms operate more effectively within autonomous institutions.

These cross-country differences also confirm the empirical operationalisation of the three mechanisms in the multinomial model: legitimacy (Mechanism 1) captured through MAI and membership, belief formation (Mechanism 2) captured through information × trust, and social enforcement (Mechanism 3) operationalised via membership × capacity and externality × institutional scope.

In summary, these results indicate that all three mechanisms, legitimacy creation, belief formation, and social enforcement, function in both countries, but their integration and effectiveness are markedly stronger in the Philippines, where meso-institutions possess greater autonomy and community participation. Empirically, institutional autonomy corresponds with a higher collective adaptation preference rate in the Philippines than in Viet Nam, demonstrating that polycentric systems enable a stronger progression from basic to institutional collective action, while more centralised systems, such as Viet Nam’s, rely heavily on state intervention, especially for high-externality problems. This confirms the theoretical prediction that autonomous meso-institutions within polycentric governance frameworks generate stronger collective adaptation outcomes than state-centred approaches.

Qualitative evidence reinforces these quantitative findings. In the Philippines, legitimacy was fostered through participatory decision-making: ‘The irrigation association doesn’t just tell us the government rules. We decide together how to apply them to our situation’. Trust-based belief formation was similarly noted: ‘When the association detect high salinity levels, we trust it and do not wait for government reports’. In Viet Nam, social enforcement mechanisms were evident despite weaker institutional structures: ‘If someone diverts the water flows, everyone knows’. These narratives affirm that beyond material incentives, social legitimacy, shared information, and local accountability underpin collective adaptation behaviour in polycentric systems.

Figure 2 illustrates the adapted Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework of Ostrom, which illustrates how farmers’ collective affiliations and organisational activities shape adaptation to saltwater inundation in the Philippines and Viet Nam. Both countries exhibit multi-layered governance systems starting with macro rules (national policies), meso-institutions (farmer groups, irrigation associations), and micro practices (farm-level adaptation). Despite resource scarcity, these polycentric systems generate place-based adaptation, especially for low-cost, high-trust measures. On the other hand, in Viet Nam, limited meso-institutional engagement leads to dependence on macro-level (state) interventions. In line with Ostrom’s polycentric governance framework, these findings suggest that meso-institutions function as transmission devices linking macro policy and micro practice. Their strength or weakness fundamentally shapes adaptation pathways.

Figure 2. Institutional analysis and development (IAD) framework for collective adaptation of farmers to saltwater inundation in the Philippines and Viet Nam.

Conclusion

This study empirically validates the polycentric governance three-mechanism framework of collective adaptation. Findings show that meso-level institutions are associated with farmers’ deliberative preferences through legitimacy creation, belief formation, and social enforcement, with the strength of these mechanisms differing by country.

Results confirm that institutional embeddedness depends on both exposure to risks and socioeconomic capacity (H1), information access enhances belief accuracy, especially in high-trust contexts (H2), institutional membership interacts with capacity to strengthen collective preferences (H3), and legitimacy and perceived feasibility drive support for adaptation measures (H4). The study also finds that institutional scope determines success in managing high-externality problems, with only Viet Nam showing a significant externality × institutional quality interaction (H5, partial). Comparatively, the Philippines demonstrates stronger polycentric governance, autonomous meso-institutions, integrated mechanism operation, and higher collective adaptation, while Viet Nam reflects a more state-centred model, weaker interaction effects, and lower collective participation.

Policy implications emphasise enhancing meso-institutional autonomy, building trust-based information systems, investing in capacity and legitimacy, and matching governance strategies to the scale of externalities. In general, the study highlights that effective climate adaptation emerges not from centralised control but from strengthening meso-institutions that enable legitimate, informed, and socially enforced collective action.

Future research could examine hybrid governance models that bring together multi-stakeholder cooperatives, social enterprises, and local associations alongside traditional state and community actors. Greater attention should also be given to horizontal forms of integration, such as inter-farmer business associations and user cooperatives, and cross-sector collaboration involving unions, NGOs, and local enterprises. These directions will help capture the evolving complexity of adaptive governance systems and advance understanding of how diverse actors jointly sustain collective adaptation to climate challenges.

Data availability statement

Anonymised data and the results of the statistical tests supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request. All data collection, handling, and storage procedures were conducted in accordance with approved institutional ethics and data management protocols. The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board, and data management practices were reviewed and endorsed by the project funder.

Acknowledgements

This research is funded through the Collaborative Research for Young Scientists Program of the Asia-Pacific Network for Global Change Research (APN).

Declaration of use of AI in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, Grammarly was used to improve the grammar, vocabulary, and word choice. After using this tool, the manuscript was reviewed and edited for content as needed.