The chief rival to capitalism … is, of course, socialism. Its key characteristic is that the state (rather than individuals) is the chief owner of income-producing property and hence the principal employer of labor.

The problem in this world is to avoid concentration of power – we must have dispersion of power.

Our mind tells us, and history confirms, that the great threat to freedom is the concentration of power.

The Cold War rivalry between the US and the Soviet Union defined the twentieth century, casting capitalism and socialism as ideological opposites. Growing up in 1980s America, hearing Cold War rhetoric underscored by the threat of nuclear annihilation and watching movies like Rocky IV and Red Dawn, which dramatized the binary clash between capitalist freedom and socialist oppression, I absorbed this framing: Being “for capitalism” meant being “for America,” while socialism was portrayed as its existential enemy. Though the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, these Cold War narratives continue to shape how capitalism is understood and debated in the US today.

But what is capitalism, exactly?

Understanding any complex system or phenomenon – capitalism included – requires comparison. Just as astronomers gained crucial insights into Earth’s formation after observing planetary formation in other solar systems, understanding capitalism also benefits from comparative analysis across economic systems.

Sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset observed, “Those who only know one country know no country.”Footnote 1 Organizational scholar Andrew Van de Ven – under whom I had the privilege to study as a PhD student at Copenhagen Business School – similarly argued that comparing at least two cases yields far deeper insight, noting that an n of 2 offers infinitely more understanding than an n of 1. Central to his concept of engaged scholarship is the idea that researchers should reflect on their own positionality and learn alongside their inquiry – not as detached observers, but as participants in the process of meaning-making.Footnote 2 As I consider capitalism in this chapter – and throughout this book – I approach it in that spirit.

This chapter takes up the comparative challenge by examining three systems: American capitalism, Nordic capitalism, and Soviet socialism. This three-way comparison clarifies capitalism’s core principles – by contrasting it with socialism – and reveals its varied expressions through a comparison of two capitalist models. Comparative analysis, central to comparative political economy and tools like benchmarking, offers critical insight into how societies structure economic life – and how they might do so more sustainably.Footnote 3

Principles of Capitalism, in Short

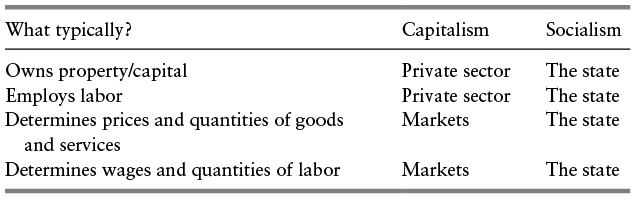

At the highest level, Capitalism is characterized by private ownership of property and capital, operating within market-driven economies. In contrast, socialism is defined by state ownership of property and capital, underpinned by centrally planned economies. Table 3.1 outlines the core principles of capitalism and socialism, which will be explored further in this chapter.

| What typically? | Capitalism | Socialism |

|---|---|---|

| Owns property/capital | Private sector | The state |

| Employs labor | Private sector | The state |

| Determines prices and quantities of goods and services | Markets | The state |

| Determines wages and quantities of labor | Markets | The state |

The term typically is crucial because it acknowledges that a society can embody capitalist principles even if certain aspects deviate from them. For instance, the US National Park System, which includes vast tracts of state-owned land, does not render the US socialist. Similarly, the state’s management of organ donor registries, which prevents human organs from becoming commodities sold in the marketplace to the highest bidder, does not justify labeling the US as socialist. Moreover, fire departments responding to anyone in need, regardless of their ability to pay a market-based price for services, does not mean the US should be considered socialist. Other examples, such as public roads, schools, libraries, the interstate highway system, Social Security, and Medicare, illustrate that publicly funded infrastructure and services can exist within a capitalist society. The qualifier typically is important. The use of 50.1 percent is a practical way to signal a simple majority. When private ownership and market-based mechanisms account for a majority of economic activity, we characterize the society as fundamentally capitalist.

In practice, no society operates under pure capitalism, where the private sector and markets dictate every facet of life – nor would most people want such a thing. A system in which organ transplants go to the highest bidder, fire services respond only to those who can pay, and children receive medical care only if their families can afford it would be widely rejected on ethical grounds. Pure capitalism is neither practical nor desirable.

Capitalism should be understood as a means — a tool — rather than a worthy purpose in itself. Sustainable development is a worthy purpose. I contend that a well-governed, democratically accountable version of capitalism can serve as the means to realize it.

Varieties of Capitalism, in Short

Varieties of Capitalism scholars compare differences in how capitalism is implemented worldwide and the distinct outcomes. When considering different combinations of 50.1 percent to 100 percent across various dimensions of capitalism, an infinite variety of possible capitalist models emerges, allowing for enlightening comparisons.

In this chapter, I also compare Nordic capitalism vis-à-vis American capitalism to demonstrate two distinct implementations of capitalism in practice. Although both varieties share more similarities when compared to Soviet socialism, the differences between American and Nordic capitalism are substantial, highlighting the broad spectrum of possibilities within capitalist systems.

Nordic capitalism is an example of democratic capitalism, characterized by a more even distribution of power throughout society, which supports and reinforces democratic ideals. In contrast, American capitalism is increasingly indicative of oligarchic capitalism, where power is concentrated in the hands of a few. This power concentration challenges the democratic functioning of society and impedes the proper functioning of markets.

Oligarchic versus Democratic Capitalism, in Short

The distinction between oligarchic and democratic capitalism is fundamental to understanding different varieties of capitalism and their capacity to achieve sustainable development.

Oligarchic capitalism is characterized by:

Concentrated economic and political power

Weak democratic institutions

Limited stakeholder voice

Short-term focus on shareholder returns

Resistance to environmental regulation

Weak labor protections

Democracy treated by powerful actors as an obstacle to be curtailed or undermined

Potential drift toward statist capitalism as powerful actors capture state institutions and redirect public authority to private ends

Democratic capitalism, in contrast, features:

Dispersed economic and political power

Strong democratic institutions

Broad stakeholder engagement

Long-term focus on societal value

Support for environmental protection

Strong labor protections

Democracy embraced by powerful actors, signaling a commitment to disperse power

The state is transparent and democratically accountable, understood as an extension of the people

These differences profoundly affect how each variety of capitalism responds to sustainability challenges. While oligarchic capitalism often resists changes that might reduce short-term profits, democratic capitalism’s more inclusive decision-making processes facilitate adaptation to emerging societal needs.

Considering different varieties of capitalist systems sets the stage for exploring the potential of realizing sustainable capitalism. By examining the broad possibilities of capitalism and identifying necessary modifications, we aim to transform the tool of capitalism to realize the worthy purpose of achieving sustainable development.

Is Socialism the Same as Communism?

While often used interchangeably, socialism and communism represent distinct concepts in Marxist theory. For Marx, socialism was a transitional stage where the state controls the economy and means of production, serving as the “dictatorship of the proletariat” before achieving communism’s classless, stateless society. This phase involves abolishing private property, nationalizing assets, and implementing central planning to determine production for all goods and services in society.Footnote 4

The socialist phase serves as a preparatory stage for the final transition to communism.

Communism represents the utopian society Marx envisioned. Goods and services are produced in abundance, and everyone takes them “according to his needs.”Footnote 5 Prices no longer exist because everything is produced in abundance, so markets cease to exist. Class divisions are eliminated because divides along lines of wealth are no longer possible. In this utopian world, Marx predicted that the state would eventually “wither away” to be replaced by a direct form of radical democracy and a united world without national boundaries.

However, Marx’s utopian vision of communism has proven unrealistic on a large scale. While communism might function in small communities where personal relationships and direct democracy can effectively facilitate resource management, scaling it to the level of a nation presents significant challenges. Gross inefficiencies and extreme shortages are the likely result without pricing mechanisms and incentives like profits.

Furthermore, history has often shown that power-hungry leaders exploit the promise of a communist utopia to consolidate their control during the transitional phase of socialism, never to relinquish it. A stark illustration of this is the Soviet Union after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. Once Vladimir Lenin centralized power, and later under Joseph Stalin’s regime, it was never relinquished. Reinhold Niebuhr poignantly articulated the gap between Marx’s utopian vision and the stark realities of power concentration, writing, “Marx’s dream of a ‘free association of workers’ turns out to be a community governed by a particularly vexatious tyranny.”Footnote 6 Similarly, John Keane challenges socialists to confront tough scrutiny of how their utopian visions play out in reality, stating, “Socialists must face up honestly to their critics’ questions: In which country have socialist movements and governments actualized the old socialist ideals of equality with liberty and solidarity?”Footnote 7

The promises of utopias diverge significantly from the materialized realities. I focus this chapter on the realities of socialism in practice, not Marx’s vision of a communist utopia.

However, the ills of power concentration are not confined to socialism. They can also manifest within capitalist systems.

Joseph Schumpeter warned that both capitalism and socialism carry risks of power concentration. While he clearly advocated for capitalism in his treatise Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, he emphasized that each system can drift toward forms of dominance that undermine democracy.Footnote 8 He warned of socialism’s tendency to concentrate power in the hands of state tyrants, and capitalism’s tendency to concentrate power among large corporations and economic elites. His warning is prescient today, as seen in the rise of monopolistic tech companies and their outsized influence over policy and political systems. Schumpeter highlighted the tensions, suggesting capitalism’s success could eventually threaten democratic principles and ultimately undermine the functioning of capitalism. At the heart of Schumpeter’s concerns is the need for sufficient dispersion of power in society, a necessary safeguard against the undue influence of any single group, be it state actors or economic elites.

Principles of Capitalism

The term “capitalism” gained prominence in English following the translation of Marx’s Das Kapital in 1867. In Das Kapital, Marx defined “capitalists” as the individuals who own capital in a society and extract profits from it. The term “capitalism” began to enter common usage shortly thereafter. French socialist Louis Blanc is credited with being among the first to use the term “capitalisme” in his 1839 work, L’Organisation du travail (The Organization of Work), where he critiqued the economic system characterized by private ownership of the means of production and profit-driven operations. Ironically, it was the critics of capitalism who helped popularize the term.Footnote 9

The following section describes the principles of capitalism.

Private Sector Typically Owns Property/Capital

In capitalist societies, property is generally owned by the private sector and can be used to generate profits. The private sector includes individuals, large corporations, small and medium-sized enterprises, cooperatives, and non-profit organizations. Property and capital are often used synonymously and encompass tangible assets like factories, buildings, natural capital (land, trees, water, and minerals), and intellectual property (patented, trademarked, or copyrighted inventions or works). Property also encompasses data like consumer and personal data.Footnote 10

The US and Nordic nations rank among global leaders in private property protections, with Finland #1, Denmark #4, Norway #6, Sweden #7, US #14, and Iceland #19 in the 2023 International Property Rights Index. Venezuela rated last out of the 125 rated nations.Footnote 11

Capitalist societies are typically easier places to do business. The World Bank periodically assesses the ease of doing business by nation, considering factors like the ease of starting a business, registering property, and enforcing contracts. Its 2019 assessment ranked Denmark #4, US #6, Norway #9, Sweden #10, Finland #20, Iceland #26. At the bottom of the rankings were Venezuela #188, Eritrea #189, Somalia #190.Footnote 12

In the Soviet Union, owning property or operating a private business was forbidden. During the Soviet era, the state owned 100 percent of the land. Shortly after the October Revolution in 1917, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, Vladimir Lenin issued the Decree on Land, abolishing private land ownership. The Soviet state assumed ownership of all land, which remained the case throughout the Soviet Union’s existence until its dissolution in 1991. Similarly, starting a for-profit business was generally forbidden in the Soviet Union.

Private Sector Typically Employs Labor

In capitalist societies, the private sector typically employs labor, whereas the state employs only a minority of the population. In socialist societies, the state typically employs most of the labor – and sometimes all.

In the US and Nordic nations, labor is employed predominantly by the private sector. The private sector in the US employs about 85 percent of labor, with about 15 percent employed by the state (including federal, state, and local governments). In the Nordic nations, about 65–75 percent of labor is employed by the private sector, with the remaining 25–35 percent employed by the state.Footnote 13

In the Soviet Union, the state employed nearly 100 percent of labor. Some individuals were allowed to farm small plots of land, growing food for personal consumption or sale at a local market, which could be considered private-sector employment. However, such commerce constituted a small percentage of the overall economy.

Markets Typically Determine Prices and Quantities of Goods and Services

Markets predominantly determine the prices and quantities of goods and services in capitalist societies. Prices and quantities for cars, haircuts, guns, butter, and most other goods and services result from the interplay of market forces. In socialist societies, prices and quantities are typically set by central planners.

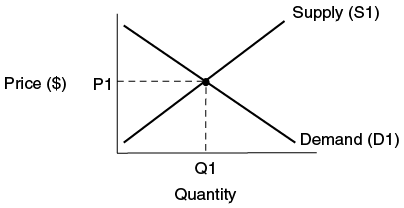

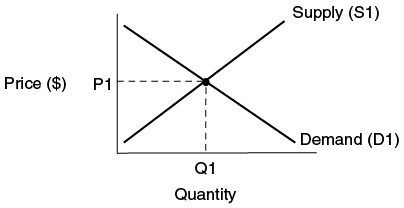

Markets are visually represented by the supply–demand curves, depicted as straight lines in Figure 3.1, representing the inverse relationship between price and demand. As a good or service becomes more expensive, demand for it reduces. Conversely, as something becomes less expensive, there will be more demand for it. The market equilibrium resides at the intersection of the supply and demand curves, representing the point where consumer demand aligns with capitalist supply. The market equilibrium is considered the most efficient output for society.

Figure 3.1 The market.

Figure 3.1Long description

Figure depicts a standard supply and demand diagram. The horizontal axis represents quantity, and the vertical axis represents price. The downward-sloping demand curve intersects with the upward-sloping supply curve. The point of intersection is marked as the market equilibrium, indicating the price and quantity where supply equals demand. This equilibrium point is considered the most efficient allocation of goods and services in a capitalist system. The curves are straight lines, illustrating the inverse relationship between price and demand, and the direct relationship between price and supply.

The US and Nordic economies typically rely upon markets to determine prices and quantities of goods and services. In the 2023 Index of Economic Freedom by the Heritage Foundation, the US and Nordic nations were categorized near the top of the global ratings, indicating a reliance upon markets to determine prices and quantities of goods and services. The index ranked Denmark #9, Sweden #10, Finland #11, Norway #12, Iceland #19, and the US #25, whereby each nation was categorized in the “Mostly Free” tier of nations. (Singapore, Switzerland, Ireland, and Taiwan topped the ranking and were categorized in the tier labeled “Free.”) At the bottom of the ratings were Venuela #174, Cuba #175, and North Korea #176.Footnote 14

The state typically set prices in the Soviet Union. The State Planning Committee, known as Gosplan, was the primary body responsible for economic planning in the Soviet Union. They set production targets across various sectors and industries, determining the quantities of goods to be produced. The State Committee on Prices, Goskomtsen, set prices based on production costs and were commonly stamped or labeled directly on goods, making them uniform across the Soviet Union. Because prices did not adjust to real-time supply and demand conditions, there were often imbalances, where shortages of certain goods could exist even if there was high demand because production targets were not met or were set too low. Similarly, there might be surpluses of goods that people didn’t want.

Stock and Bond Markets and Power Dispersion

Stock and bond markets demonstrate capitalism’s potential for dispersing power. Milton Friedman championed markets as essential safeguards against the undue concentration of power, whether in the hands of the state or individuals. Following President Trump’s announcement of global tariffs in April 2025, enacted without legislative oversight, global markets experienced significant declines. The severe market reaction proved decisive in compelling the Trump administration to reverse these tariff policies. While political leaders might seek to leverage other power forms (e.g., military) to counteract market forces, this instance underscored the markets’ vital role as a counterbalance to concentrated power. In contrast, centrally planned socialist economies lack these visible market forces, which Friedman saw as instrumental in holding political leaders accountable, and why he considered capitalism’s fundamental reliance upon markets indispensable to political freedom.

Markets Typically Determine Wages and Quantities of Labor

In capitalist societies, labor markets typically determine wages and employment rates. At the heart of the labor markets is the interplay between the labor supply and the labor demand by employers – that is to say, the “capitalists” – who seek to employ the labor. The intersection of the supply–demand curves is the equilibrium wage rate representing the labor price. At that intersection, we also have the equilibrium quantity of labor corresponding to the number of laborers employed at that wage.

For example, if wages are set above this equilibrium through an artificially high minimum wage rate, the likely result is heightened unemployment. As a thought exercise, imagine if a minimum wage of $50/hour is established across the US employers would likely lay off workers and remove their “Help Wanted” signs. An overall reduction in the quantity of labor would result in heightened unemployment. Perhaps a handful of laborers would benefit from the heightened wages but at the cost of undoubtedly far more people who would be laid off and unable to find work elsewhere.

Conversely, if wages are set below equilibrium, for example, if employers have significantly more power than labor and the employers utilize that power to suppress wages, a labor shortage is likely where potential laborers do not find the wages sufficient to take the jobs. Imagine if employers only offer $7/hour in wages. An eight-hour shift would garner only $56, which is unlikely to cover the cost of bus fare and childcare. Laborers would likely elect not to take these low-paying jobs, resulting in a labor shortage. “Help Wanted” signs would likely be prevalent, but the job openings go unfilled.

Presumably, in a capitalist society that is also a functioning democracy, an artificially high minimum wage rate would be reduced through additional legislative action to reduce the minimum wage. Similarly, in a functioning democracy, if wages are artificially suppressed because power is too concentrated with employers, legislative action would presumably be taken to disperse power so the labor markets can function. (Such legislative actions are expected in the marketplace for goods and services when private sector actors achieve concentrated power as a monopoly or oligopoly. Sufficiently dispersed power is necessary for markets to function.) Legislative action, including an increase in minimum wage laws, may also be considered.

In the Soviet Union, central planners set wages and determined labor quantities. The Soviet state determined employment levels, set wages, and assigned jobs often irrespective of individual preferences. Not showing up for your assigned job came with severe consequences. Absenteeism without a legitimate excuse could result in criminal charges for “social parasitism,” tuneyadstvo, a punishable offense under Soviet law. While the Gulags were not typically used for cases of social parasitism, the broader threat of severe punishment, including forced labor, loomed large in the Soviet Union, reinforcing compliance and suppressing personal freedom.

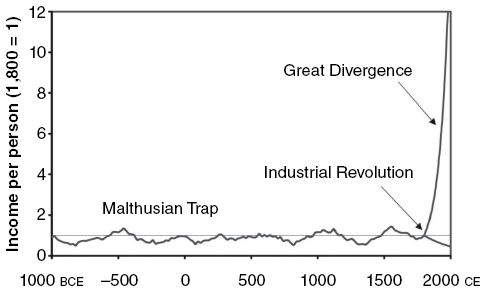

What Is So Great about Capitalism? Efficiency

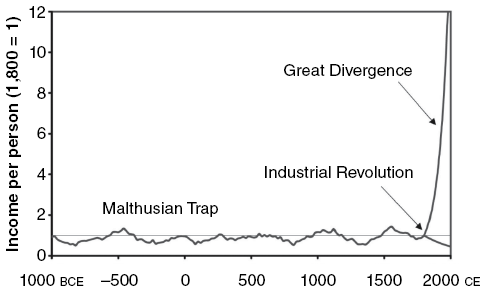

The efficiency advantages of capitalism are well established when compared to centrally planned socialist economies and earlier systems such as feudalism. Economic historian Gregory Clark notes that the economic history of the world is surprisingly simple, as it can be captured in a single graph, depicted in Figure 3.2, which shows the dramatic rise in productivity and living standards that followed the emergence of capitalism around 1800, in tandem with the Industrial Revolution.Footnote 15 Economist Jonathan Levy similarly observed that “before capitalism, societies usually scraped along just above subsistence.”Footnote 16 China’s shift toward market economics between 1981 and 2010 demonstrates capitalism’s transformative power: over 800 million people lifted from extreme poverty, accounting for half of global poverty reduction in that period.Footnote 17

Figure 3.2 Capitalism and the Industrial Revolution: The rapid rise of efficiency.

Figure 3.2Long description

Figure is a line graph tracking global income per person over time, from 1000 BC to 2000 AD, using 1800 as the baseline set to 1. For most of history, the line remains nearly flat, showing minimal increases in income. This prolonged period is labeled the Malthusian Trap. Around 1800, the line curves sharply upward, marking the onset of the Industrial Revolution. After 1800, income per person increased exponentially. This steep upward slope is labeled the Great Divergence, indicating widening income differences across regions. The graph visually reinforces how capitalism and industrialization contributed to unprecedented efficiency and productivity gains in modern history.

Together, these reflections underscore capitalism’s historical role in unlocking large-scale economic efficiency.

Capitalism’s key advantage lies in its efficient allocation of resources through decentralized decision-making and responsiveness to market signals. The Soviet Union dramatically illustrated the limitations of centralized planning, with Moscow-based planners attempting to coordinate production across fifteen republics, spanning eleven time zones and over twenty million square kilometers.

My early career as an industrial engineer at IBM offered firsthand insight into the efficiency advantages of market-based systems over centralized planning. I began in the late 1990s as a labor and capacity planner at IBM’s largest factory in Rochester, Minnesota. I quickly saw that long-term production planning often led to mismatches between supply and demand. When customer preferences shifted, we were left with excess inventory of unwanted products and shortages of those in high demand. The further out we planned, the more likely we were to misallocate resources. Efficiency improved when we responded to real-time demand rather than relying on static forecasts.

To increase responsiveness, we adopted the Toyota Production System (TPS), which emphasizes just-in-time production and real-time, on-the-ground decision-making – a stark contrast to Soviet planners managing from afar. At its core, TPS seeks to eliminate muda, or waste, to improve efficiency. A five-year production plan at our factory would have created severe mismatches between supply and demand, just as Soviet central planning produced chronic shortages of everyday goods, including toilet paper.

Creating five-year plans for agriculture introduced even greater inefficiencies. Unlike factory environments, agricultural outputs are subject to uncontrollable variables like weather and climate. The further planners attempted to forecast, the more damage was caused by deviations between projected and actual conditions. The Soviet Union experienced chronic shortages of agricultural staples, including bread. Most tragically, misguided grain requisition policies contributed to the Holodomor, the famine of 1932–1933, during which nearly 4 million Ukrainians died.

Advocates of centralized economic planning have often underestimated the complexity of efficiently producing and distributing goods and services at scale. George Orwell, a self-described socialist best known for Animal Farm and 1984, once wrote:

It is not certain that socialism is in all ways superior to capitalism, but it is certain that, unlike capitalism, it can solve the problems of consumption and production … In a socialist economy these problems do not exist. The State simply calculates what goods will be needed and does its best to produce them.Footnote 18

Orwell’s comment reflects a common mid twentieth-century optimism that central planners could master the technical challenges of production. In practice, however, the assumptions underlying this confidence often proved deeply flawed.

Socialism’s inefficiencies extend beyond those caused by central planning alone. Limited innovation results when no incentives exist to pursue greater efficiency or innovations. Individuals and corporations in a capitalist system have these incentives in the form of profits. While the Industrial Revolution’s remarkable efficiency gains stemmed from multiple factors – technological advancement, scientific discovery, and broader societal changes – capitalism’s profit incentives and the global rise of corporations significantly accelerated these developments. “Creative destruction,” Joseph Schumpeter coined in his classic Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, denotes how entrepreneurial innovations encourage long-term economic growth in capitalism, even as established companies that cannot keep up with innovations are destroyed.Footnote 19

However, for all the benefits of efficiency, critics point to capitalism’s tendency to exacerbate inequalities as a fundamental flaw. Capitalism’s defenders, like Milton Friedman, argue that addressing inequality necessarily compromises efficiency. He minimized concerns about inequality, contending that even the modern poor enjoy higher living standards than the wealthy of past generations, thanks to capitalism’s efficiency and innovation. Yet this defense of inequality as the price of efficiency remains deeply contested.

It also overlooks a central tenet of early management thinking. As Frederick Winslow Taylor wrote on page one in The Principles of Scientific Management (1911): “The principal object of management should be to secure the maximum prosperity for the employer, coupled with the maximum prosperity for each employee.”Footnote 20 Efficiency, in Taylor’s view, was not meant to enrich only those at the top but to deliver shared gains across the enterprise. That ideal has been largely abandoned under modern American capitalism, where efficiency gains often flow disproportionately to shareholders and executives.

Beyond inequality, capitalism’s relentless pursuit of efficiency frequently generates sustainability challenges that disproportionately affect the poor. China’s dramatic economic transformation illustrates this pattern: Regions of intense industrial development between 1981 and 2010 became known as cancer villages due to severe environmental degradation. The mounting climate crisis and accelerating biodiversity loss further show how capitalism’s drive for efficiency – left unchecked – has made us exceptionally efficient at consuming Earth’s resources.

While Friedman and other neoliberal economists maintained near-religious zealotry that market forces would correct environmental damage, this belief has proved tragically unfounded. As discussed in the Triangle of Tensions (Chapter 2), capitalism excels at promoting efficiency but struggles to address the twin challenges of equity and sustainability – tensions at the heart of today’s economic systems.

What’s So Great about Capitalism? – Freedom? Democracy?

Milton Friedman argued that capitalism inevitably leads to political freedom – first capitalism, then freedom. However, the post-Soviet transition challenges this assumption. Rather than fostering democracy, rapid privatization of state assets in Russia and other former Soviet states led to unprecedented concentration of economic power among oligarchs, who then captured political institutions.

This historical evidence, along with contemporary analysis of American capitalism, suggests that democracy may be a prerequisite for – rather than a consequence of – well-functioning capitalism. Without robust democratic institutions and countervailing forces, market systems alone cannot prevent the power aggregation that leads to oligarchic capitalism. While Friedman correctly identified power concentration as a fundamental concern, its dynamics have manifested in ways he did not anticipate.

Just as neoliberal economists promoted “trickle-down economics,” assuming that prosperity would naturally flow from the wealthy to the poor, Friedman’s assumption that capitalism necessarily leads to political freedom could be characterized as “trickle-down democracy.” The post-Soviet experience decisively challenges this theory of trickle-down democracy: Rather than fostering democratic institutions, rapid privatization without pre-existing democratic safeguards led to oligarchic capture of both economic and political power. The evidence suggests that, like prosperity, democracy does not simply trickle down. Democratic institutions must be deliberately constructed and vigilantly maintained, rather than expected to emerge as a natural by-product of market capitalism.

In sum, while capitalism’s efficiency advantages over centralized planning are self-evident, its relationship with equality, sustainability, political freedom, and democracy proves far more complex.

Varieties of Capitalism

Though American and Nordic capitalism share fundamental market principles that distinguish them from Soviet socialism, their distinct institutional arrangements produce markedly different social and economic outcomes. The scholarly field of “varieties of capitalism” provides frameworks for understanding these crucial differences.

With their 2001 edited volume titled Varieties of Capitalism, Peter Hall and David Soskice are credited with establishing varieties of capitalism as a distinct scholarly field.Footnote 21 Hall and Soskice distinguished between Liberal Market Economies (LMEs) typified by the US and Coordinated Market Economies (CMEs) like the Nordic nations. Their work sparked a rich academic discourse and the proliferation of further taxonomies of capitalism, including shareholder and stakeholder capitalism, oligarchic and democratic capitalism, state-led capitalism, entrepreneurial capitalism, patrimonial capitalism, climate capitalism, and even the normative categorizations of “good capitalism” and “bad capitalism.”Footnote 22

Our analysis focuses specifically on American and Nordic capitalism through two interrelated lenses: power distribution and stakeholder inclusion. Recent scholarship describes American capitalism as increasingly “oligarchic,” where concentrated economic and political power among a small elite has reshaped American institutions to serve narrow interests.Footnote 23 Nordic capitalism, by contrast, exemplifies “democratic capitalism,” marked by more dispersed power and decision-making across a wider array of stakeholders.

The distinctions between oligarchic and democratic capitalism provide crucial insights into how different varieties of capitalism shape societal outcomes.

Principles of Capitalism: American Capitalism vis-à-vis Nordic Capitalism

American and Nordic capitalism differ significantly in its principles, giving rise to their unique varieties of capitalism.

Private Sector Typically Owns Property/Capital

While both the US and Nordic nations uphold strong private property rights, they implement them differently. The conventional American publicly traded corporation differs markedly from Nordic structures, which include enterprise foundation-owned companies, cooperatives, employee-owned firms, and companies with the state as a partial owner. These variations foster different approaches to capitalism, with some structures encouraging short-term, extractive approaches and others promoting long-term stewardship.Footnote 24

In the enterprise foundation model, exemplified by publicly traded companies like Novo Nordisk and Carlsberg, as well as privately held companies like Ramboll, foundations hold controlling voting rights. This structure ensures long-term stability and channels profits toward social benefits while mitigating short-term market pressures, whether from public markets or private owners.

Another distinctive feature of the Nordic approach is its public and private ownership mix. Nordic states often hold significant minority stakes in key companies, leaving day-to-day operations and employment decisions to the private sector. This contrasts with socialist systems that rely on direct state control and state employment.

This model is particularly prevalent in the energy and natural resource sectors. Norway’s Equinor (67% state-owned) operates in oil, gas, and renewable energy. Similarly, Norsk Hydro (34.3% state-owned) leads in aluminum production, while Sweden’s Telia Company (37.3% state-owned) provides telecommunications. Finland’s Fortum (50.8% state-owned) and Denmark’s Ørsted (50.1% state-owned) demonstrate this model in the energy sector. This partial state ownership allows democratically accountable states to encourage privately held firms to pursue broader social goals consistent with sustainable development.

The Nordic region features distinct ownership structures in which ownership and governance are more commonly dispersed. Cooperatives and foundation-owned companies are significantly more prominent, enabling broader stakeholder involvement and reducing the dominance of any single owner. These structural differences shape how companies operate, with Nordic models more often supporting long-term thinking and attention to multiple stakeholders. In contrast, US models tend to prioritize shareholder interests and shorter-term outcomes.

Land ownership represents another domain of distinct difference between American and Nordic capitalism. While the private sector owns most of the land in the US and Nordic nations, environmental regulations are comparatively relaxed in the US, particularly in rural regions, affording greater freedom for US landowners to do what they want with their land. Conversely, Nordic nations emphasize more stringent land-use regulations where considerations for environmental harms or broader community interests are often elevated.

The Nordic approach to land ownership also reflects more collective values while respective private property rights. Sweden’s constitutionally protected Allemansrätten (“everyman’s right”), known as the freedom to roam, allows public access to private land for activities like hiking, foraging, and camping – so long as privacy and nature are respected.Footnote 25 Despite over 90 percent of land in Sweden being privately owned, access remains widely available, contrasting sharply with US norms of exclusion marked by “No Trespassing” signs.

The Nordic “freedom to roam” laws highlight one of the most striking differences in land ownership between Nordic and other capitalist systems. These laws grant everyone the right to access almost all land – public or private – for activities such as hiking, camping, and foraging, provided they maintain distance from private residences. In Sweden, this right, known as Allemansrätten or “everyman’s right,” is enshrined in the Constitution. Although over 90 percent of Sweden’s land is privately owned, freedom to roam ensures public access. This contrasts sharply with the US, where “No Trespassing” signs on private land (about 60% of total land) symbolize a fundamental difference that land access is reserved for owners alone.

Private Sector Typically Employs Labor

Private sector employment characterizes both American and Nordic capitalism, but their approaches to labor markets reveal fundamental differences in how these societies balance worker security with market flexibility.

American capitalism ties essential services directly to employment status. Healthcare, retirement benefits, and other social services typically come as part of a private sector employment package. Under prevalent at-will employment practices, workers can be terminated without cause, creating a double vulnerability: job loss often means simultaneous loss of essential benefits. This arrangement can trap workers in unfulfilling jobs and discourage entrepreneurship or career transitions, despite the theoretical flexibility of the American labor market.

Nordic “flexicurity” combines worker protections with market efficiency. While employers maintain termination rights, comprehensive state benefits prevent job loss from triggering personal crises, enabling greater labor market flexibility and entrepreneurial risk-taking.

Driven by robust state initiatives and strong labor unions, Nordic countries implement extensive retraining and upskilling programs that enhance workforce adaptability. This adaptability is underpinned by active labor market policies aimed at facilitating quick reemployment and maintaining high levels of labor market participation. In this system, Nordic citizens recognize the value of their comparatively high tax contributions, which fund these extensive public services, promoting a cycle of investment in human capital that benefits individual and societal welfare alike.

The assurance of continuous access to healthcare and other services, regardless of job status, fosters a culture where individuals feel secure enough to take entrepreneurial risks or pivot their careers in response to changing economic landscapes. This security – known as flexicurity that promotes security through flexible labor markets – is a cornerstone of Nordic labor policy, contrasting sharply with the US approach and highlighting a deeper philosophical difference in how labor is valued within these two varieties of capitalism.

Denmark’s postal service decision illustrates the dynamic nature of Nordic capitalism as it relates to state and private sector employment. After 400 years of state-run postal delivery, PostNord announced it would end letter delivery in 2025 due to a 90 percent decline in volume since 2000. The decision to discontinue state-employed postal delivery, affecting 1,500 workers, emerged from a clear focus on efficiency – made possible through Denmark’s commitment to transparency and democratic oversight of state enterprises. These workers can transition to new employment opportunities without fear of losing healthcare and other essential services thanks to flexicurity with its comprehensive social safety nets and retraining programs. This case demonstrates how Nordic capitalism enables even centuries-old state institutions to adapt to changing market conditions, shifting services between state and private sector delivery based on efficiency considerations while maintaining strong worker protections.Footnote 26

Markets Typically Determine Prices and Quantities of Goods/Services

In the US and Nordic nations, most goods and services are priced through market mechanisms. Whether it is groceries, clothing, lawn services, haircuts, or household items, market forces typically dictate both prices and quantities subject to supply and demand curves.

However, a key distinction lies in the Nordic model’s universal access to social services, such as healthcare. In the Nordic model, the government directly negotiates prices with providers of medical services and pharmaceuticals, unlike the US, where market forces largely control healthcare access, except for specific groups like Medicare recipients, veterans, and others covered by state-provided programs. While the state regulates healthcare pricing and access in the Nordics, the production of pharmaceuticals, including insulin by companies like Denmark’s Novo Nordisk, remains in the private sector.

The Nordic countries also offer universal subsidies for childcare, ensuring all families have access to high-quality services. This reflects the broader Nordic balance between market forces and state intervention to provide essential social support for all citizens.

In the US and Nordic nations, utilities such as water, electricity, and gas are heavily regulated, with the state often setting or approving prices. Similarly, public transportation and vehicle parking prices are usually set by the state in both regions. A notable exception is the privatization of vehicle street parking in Chicago in 2008, which led to a dramatic quadrupling of parking rates by 2009.Footnote 27 This highlighted the extent to which parking had been state-subsidized, leading to significant public backlash when prices surged under private ownership.

Higher education presents a significant contrast between the US and the Nordics. In the Nordic countries, higher education is typically tuition-free, with the state covering most associated costs through taxes. In contrast, US tuition rates are largely market-driven. While many US public universities once had low or even free in-state tuition, such as the University of California system in the 1960s, tuition rates have risen significantly over the past few decades as state funding has decreased and tuition rates are increasingly subject to market forces.

State subsidies significantly shape market outcomes. For instance, the US fossil fuel industry receives substantial government subsidies, distorting market prices and making fossil fuels artificially cheaper. This practice is not unique to the US – fossil fuel subsidies totaled $7 trillion globally in 2022, or 7.1 percent of global GDP. These subsidies, tax breaks, and loan guarantees disproportionately benefit the fossil fuel industry in the US compared to renewables, making renewable energy alternatives less competitive.Footnote 28

Internalizing Negative Externalities

A negative externality occurs when a company’s operations create costs borne by society rather than reflected in its prices – such as when factory pollution causes health problems or greenhouse gas emissions contribute to climate change. Addressing these externalities in capitalist systems requires policy interventions, typically through taxation or cap-and-trade programs, to force companies to “internalize” these costs. Carbon pricing exemplifies this approach: by making companies pay for emissions, it incorporates climate costs into prices and shifts market behavior toward sustainability.

The Nordic countries led the world in efforts to address the negative externalities of carbon emissions. Finland introduced the first carbon tax in 1990, with Sweden, Norway, and Denmark following shortly after. Today, the Nordic nations maintain among the world’s highest carbon prices – Sweden charges $126 per ton of CO2 and Norway $91 per ton.Footnote 29 While still below the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s estimated social cost of carbon ($190 per ton), intended to wholly internalize the negative externalities of CO2 emissions,Footnote 30 these carbon taxes create powerful market signals for innovation and emissions reduction.

Each Nordic nation has set ambitious climate targets backed by concrete policies. Denmark’s 2020 Climate Act mandates 70 percent emissions reduction by 2030 and climate neutrality by 2050, adding in 2024 the world’s first carbon tax on the agricultural sector through policy innovations developed via structured tripartite collaboration among government, industry, and farmers.Footnote 31 Sweden established policy to achieve net-zero by 2045, while Finland targets carbon neutrality by 2035 – the region’s most ambitious timeline.

In contrast, the US has struggled to implement comprehensive policies that internalize the cost of CO2 emissions. Even though two-thirds of Americans think the government should take more significant action on climate change, including supporting measures to tax corporations on greenhouse gas emissions, powerful lobbying by fossil fuel companies and other vested political interests has significantly hindered action.Footnote 32

California is a notable exception. In 2012, it implemented a cap-and-trade program that covers approximately 85 percent of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions, including those from large industrial facilities, power generation, and fuel distributors.Footnote 33 The program has established a price floor of $25.24 per ton of CO2 in 2024, with actual market prices typically ranging between $30 and $35 per ton. According to state data, the California program has established a market mechanism that has helped reduce the state’s emissions by approximately 30 percent between their 2004 peak and 2021.Footnote 34 While a piecemeal state-by-state approach is not ideal, and causes inefficiencies for companies (and investors) who struggle to implement and assess, California’s experience demonstrates how individual states can experiment with needed policies.

However, barriers to implementing policies that price carbon become readily apparent when examining specific cases and the associated economics.

Carbon Pricing and Corporate Accountability: Two Cases

To illustrate how carbon pricing can radically reshape corporate profitability, consider Vistra Energy, the largest corporate greenhouse gas emitter within the US.Footnote 35 In 2023, this Texas-based Fortune 500 company and its subsidiaries emitted 87 million metric tons of CO2,Footnote 36 which is approximately 1.6 percent of total US greenhouse gas emissions.Footnote 37

That same year, Vistra reported $14.8 billion in revenue and $1.5 billion in net income, yielding a 10.1 percent profit margin. But if Sweden’s carbon tax of $126 per ton were applied,Footnote 38 Vistra would face a carbon liability of $11.0 billion – flipping its profit into a $9.5 billion loss. Under the European Union’s $70 per ton carbon price, the liability would be $6.1 billion, resulting in a $4.6 billion loss.Footnote 39 The break-even carbon price – at which Vistra’s emissions liability would fully eliminate its profits – is just $17 per ton, well below even the most modest carbon pricing proposals. At the full social cost of carbon of $190 per ton, Vistra’s emissions liability would climb to $16.5 billion, exceeding its total revenue.

While the specific application of carbon taxes would vary based on sector, jurisdiction, and policy design, and therefore actual liabilities assessed would vary, these calculations illustrate the magnitude of impact that meaningful carbon pricing would have on corporate profitability, even at prices well below the full social cost of carbon. Without carbon pricing, companies can appear financially healthy while imposing enormous, unaccounted-for costs on society.

The Vistra case underscores how the invisible hand of the market depends on the visible hand of the state to function properly. Without state-enacted carbon pricing, the social and environmental costs of emissions remain external to market prices, leaving Vistra with no financial incentive to improve its efficiency in managing emissions.

Heavily fossil fuel-dependent companies like Vistra benefit from the absence of carbon pricing while publicly claiming to support it. This gap between corporate rhetoric and political action is starkly revealed in the case of ExxonMobil, another Texas-based energy giant whose behind-the-scenes lobbying runs counter to the goals of SDG #13 “Climate Action,” particularly efforts to implement carbon pricing mechanisms.

In July 2021, undercover footage surfaced of Keith McCoy, then Exxon’s senior director of government affairs in Washington, DC, candidly discussing the company’s lobbying efforts to undermine carbon pricing and broader climate legislation. McCoy acknowledged that ExxonMobil’s public support for a carbon tax was merely an “advocacy tool” and a “talking point,” noting bluntly: “Nobody is going to propose a tax on all Americans … A carbon tax is not going to happen.” He further admitted that the company had historically used “shadow groups” to fight climate science, stating: “We were looking out for our investments, we were looking out for our shareholders.”Footnote 40

In response to the public fallout, ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods issued a press release titled “Our Position on Climate Policy and Carbon Pricing.” In it, Woods asserted: “We believe a price on carbon emissions is essential to achieving net zero emissions,” and announced a $3 billion investment commitment in lower-emission technologies through 2025 – an average of less than $1 billion annually.Footnote 41

To put this in perspective: in 2023, ExxonMobil reported 98 million metric tons globally of CO2 in emissions.Footnote 42 Under Sweden’s carbon tax of $126 per ton, the company’s emissions liability would total $12.4 billion. Even under California’s more modest 2024 price floor of $25.24 per ton, the liability would amount to $2.5 billion – more than double the company’s promised annual investment in low-emission technologies touted in the wake of the damaging undercover footage.

The contrast between fossil fuel companies’ expressed public support for carbon pricing and their apparent behind-the-scenes lobbying efforts to obstruct it suggests a strategy akin to denial (Chapter 2) designed to appear proactive while in practice delaying meaningful policy action. This strategy represents an evolution from outright denial of climate science to a more sophisticated form of obstruction, where companies publicly endorse climate action while covertly preventing implementation.

Opposition to carbon pricing exposes a central paradox in neoliberal theory. While championing the invisible hand of the market and portraying government intervention as inherently anti-capitalist, neoliberalism fails to account for how addressing negative externalities requires a democratically accountable state. It is the visible hand of government that must create the market incentives, such as carbon pricing, that drive carbon efficiency through capitalistic principles.

The case of carbon pricing illustrates a broader truth: capitalism depends on robust democratic processes to function effectively, particularly when powerful corporate interests work to block the market mechanisms neoliberal proponents like Milton Friedman have long claimed make capitalism the most effective driver of efficiency.

Markets Typically Determine Wages and Quantities of Labor

A fundamental difference in labor markets between the US and Nordic nations is the levels of labor union participation. In the US, only about 10 percent of laborers are members of labor unions. Across the Nordic countries, the figure is closer to 70 percent, with some variations, with Denmark, Finland, Sweden about 70 percent, Norway closer to 50 percent, and Iceland one of the highest in the world, nearing 90 percent.Footnote 43 The differences manifest most conspicuously in determining wages for labor through collective bargaining arrangements, as discussed in the subsequent section on wages.

Differences in labor union participation reflect differences in US and Nordic varieties of capitalism, where Hall and Soskice categorize the Nordics as coordinated market economies partly because of the strength of the labor unions. Nordic countries have some of the highest unionization rates in the world. Collective bargaining is widespread, and cooperative relations are practiced between employers and unions. In contrast, with liberal market economies like the US, labor relations are often more adversarial and decentralized.

Some US audiences can associate strong labor movements or high union membership rates with socialism. This perception partly stems from the Cold War era, during which anti-communist sentiments in the US sometimes linked labor movements to socialist or communist ideologies. Historically speaking, such a linkage between socialists and labor movements existed in the Nordic region in the late 1800s and early 1900s, as will be further explored in Chapter 4. Still, such connections have dissipated in modern Nordic nations.

Labor unions can also play a significant role in specific regions or sectors, negotiating for wages and working conditions on behalf of the workforce. While the market forces inherently push towards an equilibrium, these external influences can either hasten or hinder the labor market’s responsiveness to changes in supply or demand. The result is an ever-evolving dynamic, balancing employer demands with employee welfare within the broader context of societal and economic progress.

In the US, labor unions have been equated with socialism by those who view unions’ collective bargaining and worker rights advocacy as socialistic or a slippery slope toward socialism. The equation of labor union participation with socialism in the US is likely due to the association of labor unions with Marxism, as Marx critiqued labor exploitation by capitalists, and unions often state a primary purpose to protect workers from such exploitation. However, as the Nordic experience demonstrates, labor unions can coexist with capitalism.

Minimum Wage Laws and Market Equilibrium

Neoliberal economists like Milton Friedman argued that minimum wage laws force prices and quantities away from market equilibrium, creating inefficiencies. This view emphasizes minimal state intervention in market operations.

According to neoliberal theory, a minimum wage law artificially raises wages (P1) and reduces the number of workers employed (Q1). So, establishing a minimum wage above P1 increases unemployment for low-wage workers. Friedman contended that a minimum wage law harms the people it was established to help – low-wage earners. He stated, “The minimum wage law is most properly described as a law saying employers must discriminate against people with low skills.”Footnote 44 Friedman furthermore contended minimum wage laws had the effect of increasing unemployment among Black citizens, “I’ve often said that the minimum wage rate is the most anti-Negro law on the books.”Footnote 45

Economists like David Card and Alan Krueger described neoliberal presumptions about minimum wages as myths. They empirically showed that increases in the minimum wage do not inevitably result in increased unemployment among low-wage earners.Footnote 46

Card and Krueger’s groundbreaking 1992 study of New Jersey’s minimum wage increase (from $4.25 to $5.05 per hour) found no evidence of increased unemployment in fast-food restaurants, contrary to Friedman’s theoretical predictions. This natural experiment, which used eastern Pennsylvania as a control group, earned Card the 2021 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences and fundamentally challenged conventional wisdom about minimum wage effects.Footnote 47

Subsequent research has reinforced Card and Krueger’s conclusions, including a 2024 study on California’s policy setting a $20 minimum wage floor for large fast-food chains that raised wages for 90 percent of non-managerial workers. This policy resulted in an 18 percent increase in average hourly wages without causing a rise in unemployment. Prices rose modestly, by about 3.7 percent (roughly 15 cents on a $4 hamburger), far lower than the dire predictions from industry representatives.Footnote 48

Card and Krueger’s work, along with studies that have replicated their findings, underscores the importance of a more nuanced understanding of societal conditions, particularly the distribution of power. Neoliberal economists like Friedman often assumed that power is sufficiently dispersed for markets to operate efficiently. However, Card and Krueger’s research challenges this assumption, suggesting it requires empirical testing. In the US, for example, the concentration of power among capital owners may enable them to suppress wages below market equilibrium, distorting the market and limiting its efficiency.

To fully grasp the role of power concentration in wage-setting, examining different varieties of capitalism is useful. In particular, we can compare oligarchic capitalism, where economic power is concentrated among capital owners, with democratic capitalism, where power is more widely dispersed. Understanding these distinctions is critical to analyzing how minimum wage laws function in different economic systems.

In a society reflective of democratic capitalism, where power is sufficiently dispersed and markets are functioning well, introducing a minimum wage law could likely result in increased unemployment. If P1 and Q1 were already at market equilibrium, an artificial increase in P1 (wages) through a minimum wage law could likely lead to a decrease in Q1 (laborers).

Denmark may represent an example of democratic capitalism worthy of consideration here. Denmark’s lowest-paid McDonald’s employees already earn $22/hour without minimum wage laws. Suppose Denmark enacted a minimum wage law that increased wages by 20 percent (i.e., P1 increases from $22/hour to P2 of $26/hour). In that case, one might anticipate a decrease in laborers (i.e., Q1 to Q2 decreases) because the market equilibrium was already achieved before the minimum wage law. Friedman’s stance against minimum wage laws was made with the presumption that power is sufficiently dispersed and markets are functioning – where all actors are price takers, and none are price makers.

But what happens in a capitalist society where power is not sufficiently dispersed?

In a capitalist society with highly concentrated power, a small group of actors can become price setters. Such is the case with oligarchic capitalism. In a society where power is concentrated with capital owners, the capitalists can leverage their power to act as price makers and suppress prices for labor (i.e., wages). Card and Krueger’s research demonstrates how concentrated corporate power can suppress wages below market equilibrium. When New Jersey’s minimum wage increased by 20 percent, McDonald’s maintained employment levels while absorbing reduced profits, suggesting wages had been artificially suppressed. The minimum wage law effectively redistributed some profits from capital owners to labor while moving the labor market closer to equilibrium.

Friedman’s critique of minimum wage laws inadvertently reveals a more fundamental issue: the failure of markets when power becomes too concentrated. The contrast between the US and Denmark illuminates this point. While US policymakers rely on minimum wage laws to protect workers, Denmark achieves higher wages – about triple the US federal minimum – without such legislation. This stark difference challenges us to examine why American capitalism requires state intervention to achieve what Nordic capitalism accomplishes through more balanced market structures.

Denmark and its Nordic neighbors are home to “the world’s strongest trade unions.”Footnote 49 Collective bargaining agreements are negotiated between the capitalists and labor unions every two to three years, a process underpinned by a commitment to cooperation and consensus-building over conflict.Footnote 50 The state takes a backseat in the process and only intervenes when an agreement is not achieved, which is rare in the Nordic nations. Power is, therefore, more sufficiently dispersed between the capital owners (e.g., McDonald’s franchise owners) and labor to ensure no single actor is a price maker.Footnote 51 One could argue that Nordic capitalism is more “capitalistic” than American capitalism regarding labor markets, as the strength of Nordic labor unions effectively disperses power and obviates the need for minimum wage laws. In Denmark, for example, there is no minimum wage, yet workers receive far higher wages than their American counterparts. The labor market requires government intervention through minimum wage laws to correct for the imbalances caused by concentrated corporate power.

The higher wages for the lowest-paid labor do not come at the cost of higher unemployment in Denmark, which is consistently low.Footnote 52 Again, the cost of a Big Mac in Denmark as of 2021 was about $5.15, compared to about $4.80 in the US.Footnote 53 So, while a McDonald’s worker in Denmark pays about 7 percent more for lunch, they earn three times more than their minimum wage-earning US counterparts.

Which actors benefit from productivity gains is predominantly a question of power. In a capitalist society that tends toward oligarchic capitalism, where power is concentrated with the capital owners, one can expect capital owners to extract a larger share of the prosperity created. In a capitalist society that tends toward democratic capitalism, where power is more sufficiently dispersed, one can expect a heightened level of shared prosperity. Had minimum wage in the US kept pace with productivity gains since 1968, the minimum wage would have been $21.45/hour by 2020 – about equal to a Danish McDonald’s worker today – indicating power has been increasingly concentrated with capital owners in the US.Footnote 54

Examining wages for the lowest-paid laborers in society reminds us that markets are not immutable natural laws like those of physics. The term “physics envy” arose in the twentieth century to critique a perceived tendency by economists to present markets as guided by a gravity-like force – metaphorically represented by the invisible hand.Footnote 55 A rock accelerates to the Earth at 9.8 m/s2 because of gravity, irrespective of whether it is dropped in the US or Denmark. However, a McDonald’s worker in the US may earn $7.25/hour while a McDonald’s worker in Denmark earns $22/hour because markets are social constructions created and shaped by human beings through the “visible hand” of laws, institutions, social norms, and matters of power concentration in society.Footnote 56

More Varieties of Capitalism

While we have focused on comparing American and Nordic capitalism, examining additional varieties of capitalism can further illuminate how different institutional arrangements affect economic and social outcomes. Many more typologies of capitalism exist, each offering unique insights into how market economies can be structured.

Hall and Soskice delineated between LMEs and CMEs in their 2001 Varieties of Capitalism. Scholars like Kathleen Thelen added nuance to Hall and Soskice’s work, exploring how variations in power structures within the categories, such as the strength or weakness of labor unions, can influence a nation’s vocational training system, further connecting labor unions and educational opportunities to the varieties of capitalism discourse.Footnote 57

More recently, advocates for “stakeholder capitalism” have become increasingly prevalent. Stakeholder capitalism is rooted in a stakeholder view of the firm. It asserts that businesses should create value for all stakeholders, not just shareholders, and that a firm’s success is intimately connected to the well-being of its customers, employees, suppliers, communities, and shareholders. The shareholder view of the firm is most closely associated with R. Edward Freeman, stemming from his 1984 book Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Stakeholder capitalism is commonly juxtaposed vis-à-vis shareholder capitalism, rooted in the shareholder view of the firm. Shareholder capitalism is, therefore, most associated with Milton Friedman and his 1970 offering “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits.” The Business Roundtable, a group of CEOs from major US corporations, advocated for a shift from shareholder capitalism to stakeholder capitalism with their 2019 restatement of the corporation’s purpose. More recently, World Economic Forum founder Klaus Schwab further popularized stakeholder capitalism with his 2021 book Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy that Works for Progress, People and Planet.Footnote 58

Stakeholder capitalism is rooted in democratic ideals and measures to disperse power throughout society to prevent a concentration of power with capital owners. As such, it exhibits strong connections with “democratic capitalism.” Democratic capitalism is affiliated with Michael Novak, mainly stemming from his 1982 book The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism. Novak describes democratic capitalism as rooted in an ethical and cultural system that respects human dignity and individual-level freedoms, producing a more just, humane, and prosperous society.Footnote 59 Democratic capitalism and the closely related ideas of stakeholder capitalism are based on ethical foundations and practical considerations for building a good society.

The labels for varieties of capitalism intersect and overlap. They do not have precise black-and-white criteria but are oftentimes more conceptual. Depending on the analysis at hand, different suites of labels are more valuable than others.

Sustainable Capitalism

This book defines sustainable capitalism as development achieved through capitalistic principles that meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own. This definition aligns with the objectives of the emerging “post-growth” field, which seeks to replace GDP as the primary metric with a focus on human well-being within planetary boundaries. However, the definition offered here remains agnostic regarding economic growth. From a sustainability perspective, growth becomes irrelevant if it can be effectively decoupled from environmental degradation – through mechanisms such as circular economy practices – and within planetary boundaries. At present, however, we remain far from realizing this possibility.Footnote 60

This conceptualization of sustainable capitalism distinguishes between the end (i.e., purpose) and the means. The purpose of sustainable capitalism is to achieve sustainable development within planetary boundaries, and the means are capitalist principles. Capitalism is a powerful means, but it is not, in itself, a compelling purpose. Sustainable development, by contrast, is a compelling purpose. By harnessing capitalism’s strengths in the service of achieving the higher purpose of sustainable development, sustainable capitalism offers a pragmatic approach to building flourishing, freedom-filled societies for future generations.

The term “sustainable capitalism” gained broader visibility through Al Gore and David Blood’s Wall Street Journal opinion article, “A Manifesto for Sustainable Capitalism,” published in 2011.Footnote 61 Building on the 1987 Brundtland Report and the 1999 book Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution by Paul Hawken and colleagues,Footnote 62 Gore and Blood highlighted the importance of preserving natural capital within a capitalistic framework. Their vision of sustainable capitalism emphasizes stewardship over extractive approaches, requiring the internalization of negative externalities through policy interventions. Unsustainable industries, mainly those reliant on fossil fuels, must be radically restructured or phased out, while human talent should be directed toward sustainable sectors.

Nordic nations’ strong performance on the SDG Index makes them a leading model for aligning capitalism with sustainable development. Their success in SDG #3 “Good Health and Well-Being” is evident in universal healthcare systems that provide high-quality care at lower cost – about 10 percent of GDP compared to 18 percent in the US, which leaves many uninsured.Footnote 63 On SDG #7 “Affordable and Clean Energy,” Nordic countries have long invested in renewables, with Denmark’s wind, Norway’s hydropower, and Iceland’s geothermal energy showing how coordinated policies and market incentives can drive sustainability. These efforts also support SDG #8 “Decent Work and Economic Growth” through green job creation and strong labor protections. Their high carbon taxes and aggressive climate targets advance SDG #13 “Climate Action.” More broadly, Nordic policies promote shared prosperity (SDGs #1 “No Poverty” and #10 “Reduced Inequalities”) and responsible industrial practices (SDGs #9 “Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure” and #12 “Responsible Consumption and Production”).

The Nordic principle of freedom to roam – the right to access nearly all land, public or private – epitomizes a distinctive approach to land use within Nordic capitalism. Enshrined in law and cultural practice, this right reflects a deep commitment to both public health and ecological stewardship, aligning with SDGs #11 “Sustainable Cities and Communities” and #15 “Life on Land.” In societies where freedom to roam is embraced, land is seen as private property and a shared resource. This outlook may make such societies more receptive to ideas like Wilson’s Half-Earth, which calls for preserving large, connected habitats to support biodiversity.

Arguably, Nordic capitalism’s greatest strength lies in its vibrant democracies. These systems empower broad-based participation, creating the political will necessary for implementing the forward-thinking policies essential for realizing sustainable capitalism.

Role of the State to Realize Sustainable Capitalism

An effective state is critical in steering market forces toward addressing transgressed planetary boundaries, such as climate change and biodiversity loss. Historical precedents, like the success of the Montreal Protocol in addressing ozone depletion, illustrate the essential interaction between state policies and establishing the necessary market incentives to spur private sector innovation.

The successes of Nordic capitalism in SDG #7 “Affordable and Clean Energy” highlight the importance of a democratically accountable state to craft policies that align markets with sustainable development goals. The state’s “visible hand” has been vital in shaping policies to internalize negative externalities, transition away from fossil fuels, and foster a labor market oriented toward green jobs. These policies have garnered public support by ensuring that the benefits of the green transition outweigh the short-term costs.

Additionally, Nordic successes in SDG #5 “Gender Equality” demonstrate the state’s pivotal role in advancing societal goals. Policies such as paid parental leave, universal childcare, and pay transparency have increased female workforce participation and narrowed the gender pay gap, offering a model of how state interventions can support equity within a capitalist framework.

Realizing sustainable capitalism will require overcoming entrenched attitudes toward the state, particularly in the US, where Cold War rhetoric has framed government as an impediment to freedom.

In his 2022 book Governance and Business Models for Sustainable Capitalism, Atle Middtun underscored the critical role of a democratically accountable state in achieving sustainable capitalism. Middtun highlighted the state’s crucial role in coordinating activities like internalizing negative externalities and coordinating public investments in sustainability projects approved through democratic vetting. Middtun argued, “The state needs to be part of the equation for civilizing capitalism … The democratic state can credibly represent the public interest better than other actors.”Footnote 64 Middtun emphasizes that large-scale coordination aligned to sustainable development can occur in a capitalistic context, provided the democratic apparatus of the state is strong. He stresses he is not advocating for a variety of socialism but instead emphasizes the need for more attention to democracy as we consider constructions of capitalism. “This is not an argument for going back to projects under a public command and control economy,” highlighting Middtun’s awareness that such proposals of state involvement are likely to attract charges of Soviet socialism.

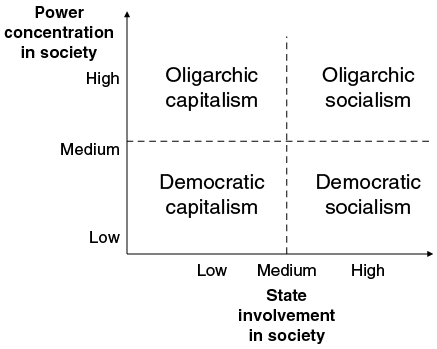

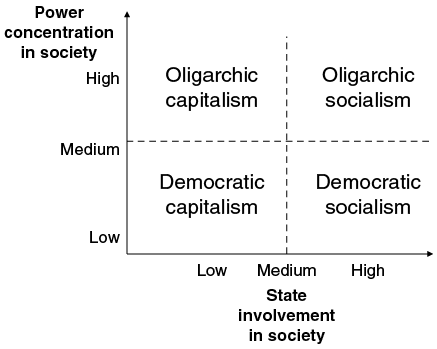

Figure 3.3 illustrates a conceptual typology of capitalism and socialism based on two key dimensions: power concentration in society and state involvement. This framework helps visualize how democratic capitalism, as distinct from oligarchic capitalism, combines decentralized power with an active, democratically accountable state.

Figure 3.3 Typologies of capitalism and socialism.

Figure 3.3Long description

Two cross two matrix categorizes political-economic systems along two axes: the horizontal axis shows State Involvement in Society, increasing from Low to Medium on the left, to High on the right, and the vertical axis shows Power Concentration in Society, increasing from Low at the bottom to High at the top. The four quadrants are: Top Left, Oligarchic Capitalism, High Power, Low Medium State; Top Right, Oligarchic Socialism, High Power, High State; Bottom Left, Democratic Capitalism, Low Power, Low Medium State; Bottom Right, Democratic Socialism, Low Power, High State. This typology highlights how systems differ by both power distribution and state involvement.

Realizing sustainable capitalism very likely depends on achieving democratic capitalism. Democratic capitalism involves a well-functioning, transparent, and democratically accountable state committed to helping coordinate a society’s capitalist activities toward sustainable development, where the populace is committed to sustainable development and holds its democratic institutions accountable. At the heart of democratic capitalism is democratic accountability and the dispersion of power in society – a stark contrast to oligarchic capitalism, where power is overly concentrated, and the interests of a narrow few are more likely to be represented in political decisions than the interests of the broader public.

In addition to historical advocates like Michael Novak, contemporary proponents such as Rebecca Henderson, author of the 2020 book Reimagining Capitalism,Footnote 65 argue that capitalism’s survival depends on the health of democracy. Henderson notes, “The decline of democracy is a mortal threat to the legitimacy and health of capitalism.” She added, “I’m not optimistic, but I am hopeful. The decline of democracy is a mortal threat to the legitimacy and health of capitalism – and business leaders are increasingly recognizing this.”Footnote 66

A recent example of democratic capitalism in action is Denmark’s 2024 decision to become the first country to implement a carbon tax on the agricultural sector. This policy emerged from Denmark’s hallmark tripartite negotiation process involving labor unions, farmers, and government representatives. The inclusive and democratic nature of the framework ensured that key stakeholders shaped the outcome. Farmers supported the tax as it provided a market-driven mechanism for sustainability, rewarding innovation, and offering financial support for adopting greener practices. The state’s role was indispensable in establishing the market conditions necessary to internalize externalities like livestock emissions, advancing progress on SDG #13 “Climate Action” by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, SDG #15 “Life on Land” by restoring carbon-rich soils, and SDG #12 “Responsible Consumption and Production” by promoting sustainable agricultural practices. Crucially, the tax also aligns with SDG #8 “Decent Work and Economic Growth,” as it is designed to safeguard jobs and ensure farmers’ livelihoods are supported during the green transition. This inclusive and coordinated approach not only demonstrates the potential of democratic capitalism to align market incentives with sustainability goals but also brings Denmark closer to realizing a version of sustainable capitalism.Footnote 67

Parting Reflections