Introduction

Chemical fertilizer use is one of the leading contributors to the crop productivity increase over the last century. Despite the critical role in enhancing crop yields, chemical fertilizers account for approximately 2.4% of total global emissions (IATP, 2022; Statista, 2024). When not absorbed by plants, chemical fertilizers also cause adverse effects to nearby water bodies through leaching and surface runoff, which further results in various aesthetic, health, and economic issues (Legg and Meisinger, Reference Legg and Meisinger1982; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Fan, Xu, Kumar and Kasu2021a).

Biochar has the potential to offset the adverse effects of environmental pollution caused by the excessive use of chemical fertilizers. As a carbon-rich material produced through the pyrolysis of animal and plant products, biochar has the potential to be used as an alternative to chemical fertilizers in agricultural production (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Wang, Riaz, Islam, Khan, Shah, Munsif and Haq2019; Mashamaite et al., Reference Mashamaite, Motsi, Manyevere and Poswa2024). The use of biochar could help reduce greenhouse gas emissions, meanwhile enhancing soil health and water retention (Gross et al., Reference Gross, Bromm and Glaser2021; Kabir, Kim and Kwon, Reference Kabir, Kim and Kwon2023; Savci, Reference Savci2012; Shrestha et al., Reference Shrestha, Jacinthe, Lal, Lorenz, Singh, Demyan, Ren and Lindsey2023; Woolf et al., Reference Woolf, Amonette, Street-Perrott, Lehmann and Joseph2010; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Xu, Liu, Liu, Zhu, Tu, Amonette, Cadisch, Yong and Hu2013).

When used as a soil ameliorant, biochar helps enhance soil quality and plant growth (Khan et al., Reference Khan, Irshad, Mehmood, Hasnain, Nawaz, Rais, Gul, Wahid, Hashem, Abd_Allah and Ibrar2024). Soils amended with biochar have been demonstrated to have a twofold increase in microbial biomass activity, contributing to enhanced soil fertility and plant health (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Liu, Wei, Liu, Gu, Gou and Wang2023). Findings from USDA (2022) further demonstrated that the use of biochar in agricultural production reduces the need for irrigation due to its capability to improve soil water retention. Biochar could also boost crop yield. For example, experimental studies in Illinois found that biochar alone increased corn yield by 18%–23% and that biochar combined with synthetic fertilizer boosted productivity even more than using synthetic fertilizer alone (Zheng and Sharma, Reference Zheng and Sharma2020). Moreover, biochar could have an advantage in economic performance, with its average production cost at $1.06 kg−1, which is lower than that of activated carbon derived from woody biomass at $1.34 kg−1 (Shaheen, Fseha and Sizirici, Reference Shaheen, Fseha and Sizirici2022). A recent review study also highlights biochar’s economic feasibility with substantial increases in yield and net returns for some optimized systems (Bandara, Reference Bandara2025).

Despite the potential environmental, agronomic, and economic benefits of biochar, the market of biochar is still nascent with some uncertainties. For example, biochar use may not show immediate benefit (Major et al., Reference Major, Rondon, Molina, Riha and Lehmann2010). Moreover, the yield boosting effect of biochar may not be universal and could be dependent on soils (Jeffery et al., Reference Jeffery, Abalos, Prodana, Bastos, Van Groenigen, Hungate and Verheijen2017) and climatic conditions (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Ren, Tao, Tao and Lindsey2025; Rogovska et al., Reference Rogovska, Laird, Rathke and Karlen2014). In addition, the impacts of biochar on enhancing carbon storage and soil health differ for soils with different pH values and mineral contents (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Guo, Zhou, Luo, Yi, Zhou, Wu, Petticord and Song2025). Other adoption barriers include inconsistent quality standards, high costs, and a lack of policy support (Bandara, Reference Bandara2025). Due to such barriers and more importantly, knowledge gaps about biochar, the adoption rate of biochar remains very low in the U.S. Midwest (Wang and Cheye, Reference Wang and Cheye2022).

To enhance farmers’ willingness to adopt, farmers need to have a better understanding about biochar, its potential benefits, and the role it plays in achieving the goal of sustainable agriculture. Improved science communication and outreach efforts play an important role in promoting biochar adoption (Pierson et al., Reference Pierson, Anderson, Brewen, Clark, Hardy and McCollum2024). It has been shown that messages framed from different perspectives have a significant impact on outcomes. Message framing is a communication strategy that involves carefully selecting messages that highlight some aspects of reality to shift the mental thought processes of the receiver to have a more positive influence on their behaviors, choices, and decisions (Marra and Myer, Reference Marra and Myer2020). In fields such as agriculture and health, message framing plays a critical role with their significance highlighted in a couple of previous studies (Gallagher and Updegraff, Reference Gallagher and Updegraff2012; Larochelle et al., Reference Larochelle, Alwang, Travis, Barrera and Dominguez2019; Reddy et al., Reference Reddy, Wardropper, Weigel, Masuda, Harden, Ranjan, Getson, Esman, Ferraro and Prokopy2020; Viskupič et al., Reference Viskupič, Wiltse and Meyer2022a).

In agricultural settings, how a message is framed may influence the way it is perceived by farmers in relevance to their personal and professional goals. Messages emphasizing stewardship values could appeal to farmers’ sense of long-term environmental care and land preservation, while economic framing might incentivize adoption through immediate benefits such as increased yields and profits. For example, regarding climate change communications, Krantz and Monroe (Reference Krantz and Monroe2016) indicated that stewardship frame was better than economic frame in motivating people to think more positively about climate change and could be a more effective way to generate climate messages. Spence and Pidgeon (Reference Spence and Pidgeon2010) found gain frames superior to loss frames in communicating the severity of climate change and generating positive attitudes toward climate change mitigation. Framed messages, however, may not always generate positive outcomes. As demonstrated by Reddy et al. (Reference Reddy, Wardropper, Weigel, Masuda, Harden, Ranjan, Getson, Esman, Ferraro and Prokopy2020), messages framed to emphasize economic and/or environmental benefits reduced farmers’ desire to take the conservation behavior compared with the informational message (control).

Although previous studies have shed critical insights on the effectiveness of message framing in promoting conservation behaviors, no research has investigated the importance of message framing in promoting the use of biochar. To bridge this knowledge gap, we carried out a survey targeting farm operators in Eastern South Dakota, a region with concentrated production of corn and soybeans (Wang and Wongpiyabovorn, Reference Wang and Wongpiyabovorn2024), and the former uses chemical fertilizer intensively as an input. This region has a continental climate, marked by high precipitation variability and a significant risk of both severe drought and heavy rainfall (Barth and Sando, Reference Barth and Sando2024). Such weather patterns could cause major challenges for soil stability and nutrient management, and therefore it is important to consider biochar as a soil amendment to boost soil health and water retention. In addition, the glaciated landscapes of Eastern South Dakota feature a variety of soil types, some of which are susceptible to salinity and sodicity. Soil amendments rich in calcium and magnesium, such as biochar, offer opportunities to reclaim or improve marginal lands (Klopp and Bly, Reference Klopp and Bly2024). Given that biochar has the potential to serve as a partial substitute for chemical fertilizer in our studied region, we intend to provide a better understanding toward the importance of message framing in enhancing farmers’ desire to learn more about biochar as a chemical fertilizer alternative, as well as the role of message framing on farmers’ future adoption decisions.

Data and methodology

Survey description

We conducted a farmer survey from February 22 to March 9, 2025 to test the impact of message framing on farmers’ learning and adoption decisions of biochar. A sample of 10,000 South Dakota farming operations east of the Missouri River (where climate favors row crop production) was randomly drawn from those who participated in Farm Service Agency (FSA) programs in 2024. Each recipient was sent an invitation letter with a link to answer the survey questionnaire online, administered through the QuestionPro survey platform. The survey received approval from South Dakota State University’s Institutional Review Board. We received a total of 812 responses, of which 320 indicated they were not current agricultural producers (retirees, nonfarming landowners, etc.). The remaining 492 eligible farmers completed the survey questionnaire.

This relatively low number of responses could be due to the online survey format, which generally has lower response rate than mail survey (Daikeler, Bošnjak and Lozar Manfreda, Reference Daikeler, Bošnjak and Lozar Manfreda2020). In addition, FSA survey samples generally contain many bad addresses or farmers who never farmed (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Xu, Kolady, Ulrich-Schad and Clay2021b). Furthermore, no monetary incentive was provided, which is not beneficial for survey participation (Avemegah et al., Reference Avemegah, Gu, Abulbasher, Koci, Ogunyiola and Eduful2021). To evaluate the representativeness of our survey respondents, we compared the age and farm size of our respondents with the 2022 U.S. Agricultural Census data. The average survey respondents’ age is 55.8 years, which is not different from the census average age of 57.2 years at a 5% significance level. However, the average farm size in our survey is 840 acres, which is significantly lower than the census average of 1,495 acres. In this regard, previous studies also found average farm size using FSA sample lower than the census average (Avemegah et al., Reference Avemegah, Gu, Abulbasher, Koci, Ogunyiola and Eduful2021).

Overall, our sample size aligns with those of comparable studies that employed online surveys among South Dakota farmers (Avemegah et al., Reference Avemegah, May, Ulrich-Schad, Kovács and Clark2024; Viskupič et al., Reference Viskupič, Celik and Wiltse2022b). The random assignment of farmers into three groups ensures that unmeasured traits potentially influencing learning or adoption interest of biochar are evenly distributed across groups (Weigel et al., Reference Weigel, Cruse and Reddy2022). The design of the study allows us to attribute outcome differences to treatment effects rather than to preexisting characteristics, thereby maintaining the internal validity of our findings.

Data description

Despite the benefits of biochar, very few farmers adopted it in South Dakota. To understand how message framing may affect nonadopters’ interest to learn and desire to adopt biochar, we first asked our survey respondents whether they currently use biochar as a soil amendment in their land management. Out of 492 respondents, only 4 chose ‘yes’ for this question. The rest were randomly split into three groups; to each group, we provided a different message about biochar, which are displayed in Table 1, with differences shown in bold and italics for comparison purposes. Among those, the economic framing targeted farmers’ economic and productivity goals, focusing on the benefit of biochar in improving crop yields and farm profitability, while the stewardship framing appealed to farmers’ desire toward long-term responsible land management and leaving a legacy for future generations, in contrast to the control message, which focused on providing a neutral, factual description.

Table 1. A side-by-side comparison of message differences provided to three randomized groups of farm operators in Eastern South Dakota

Note: Bold and italicized parts illustrate differences across message frames for comparison purposes.

After reading the corresponding messages provided to their groups, survey respondents were asked whether they have interest in learning more about biochar with four possible options: 1 = ‘not interested at all’, 2 = ‘not interested’, 3 = ‘interested’, and 4 = ‘very interested’. The average interest ratings were 2.76, 2.67, and 2.60 for the economic, stewardship, and control groups, respectively (Table 2). Based on Duncan’s multiple range test, the means of three different groups are not significantly different at the 5% level. We further developed a binary variable for learning interest, where farmers who chose the two not interested options are combined into one group, and those choosing the two interested options are combined into the other (Table 2). Two thirds of producers demonstrated different degrees of interest in learning more about biochar, ranging from 61% to 72% across groups. While the economic group shows the highest interest, the degrees of interest did not differ at the 5% level across the three groups.

Table 2. Farmers’ learning interest and adoption likelihood of biochar by message framing: Ducan multiple range test results

Note: Subscripts are used to denote Duncan’s multiple range test results, where the numbers with same letters imply no statistically significant difference exist between the average values in different groups.

We also checked farmers’ likelihood to adopt biochar in the next 5 years, denoted as follows: 1 = ‘very unlikely’, 2 = ‘somewhat unlikely’, 3 = ‘neither likely or unlikely’, 4 = ‘somewhat likely’, and 5 = ‘very likely’. The average likelihood ratings were 2.80, 2.78, and 2.49 for the economic, stewardship, and control groups, respectively. Among these, the average likelihood ratings for the economic and stewardship groups are both significantly higher than that of the control group, yet no significant difference exists between those for the economic and stewardship groups (Table 2). Similarly, a binary variable is developed for the adoption likelihood, with those who indicated ‘somewhat likely’ or ‘very likely’ denoted as 1, and the other three categories denoted as 0. We can see that the proportion of farmers who indicated they are likely to adopt were only around 10%, much lower than that of farmers showing the learning interest. Sixteen percent of farmers in the stewardship group demonstrated their desire to adopt, which is significantly higher than the 6% for the control group (Table 2).

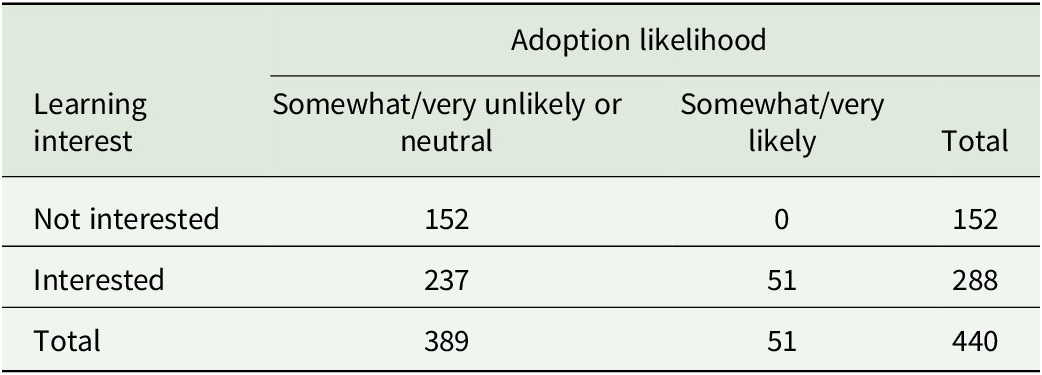

The frequency distribution of farmers’ interest in learning and likelihood of adoption is provided in Table 3. Not surprisingly, none of the farmers who showed no interest in learning biochar were interested in adopting biochar in the future. This indicates that learning is a prerequisite for adoption. Yet, among 288 respondents who are willing to learn, only 51 (18%) of them indicated further desire to adopt. This means most farmers, even though willing to learn, find future adoption aspect rather uncertain.

Table 3. Interaction between learning interest and adoption likelihood

Table 4 displays the summary statistics for all explanatory variables included in the regression. Both economic framing and stewardship framing are included, which take the values of 0.32 and 0.33, respectively. This indicates that roughly one third of the farmers were included in each of the three groups. To control other potential factors that may affect farmers’ decisions toward learning or adopting biochar, we also included some variables of farm characteristics. It has been shown that farms with higher gross sales are more likely to adopt new technologies or conservation practices (Lamba, Filson and Adekunle, Reference Lamba, Filson and Adekunle2009; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Sullivan, Claassen and Foreman2007). In our survey, gross sales takes six possible values ranging from 1 = ‘< 50,000’ to 6 = ‘>1,000,000’. An average value of 3.83 shows, on average, our surveyed farms have an average gross sales value close to 4 = ‘250,000–499,999’ range. Furthermore, operators for farms with a higher percentage of land with saline and sodic conditions are more likely to take different measures to revert or adapt to such conditions (Yarazari et al., Reference Yarazari, Devegowda, Shelar and Sachin2019). Therefore, they may be more likely to try a new practice such as biochar as a potential means to improve the soil conditions. The saline condition variable also takes six possible values from 1 = ‘0%’ to 6 = ‘>20%’. A mean value of 2.19 suggests that, on average, our surveyed farms have 1%–5% of cropland under saline or sodic conditions.

Table 4. Summary statics for the explanatory variables included in the regression

In addition, farmers’ perceived weather trends, such as more severe wet and drought conditions, were included to capture farmers’ awareness of the changes that directly affect farming. In general, farmers who perceive greater changes in different aspects affecting farming are more likely to alter their management practices to adapt to such changes. Both variables take five different values spanning from 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 = ‘strongly agree’. The average values for these two variables are very similar, at 3.28 and 3.35, respectively, for the severe wet and drought conditions. This indicates that farmers, on average, are inclined to show some agreement that their farms have been affected by extreme weather conditions such as flooding and drought.

Variable ‘extension’ was included to find out whether farmers have been using extension service to make fertilizer application/planning decisions. Extension plays a crucial role in disseminating new technologies and innovations to farmers (Suvedi and Kaplowitz, Reference Suvedi and Kaplowitz2016). Therefore, we expect to find those farmers who use Extension service more willing to learn new things such as biochar. Only about a quarter of farmers use extension service as a source to make such decisions. An explanatory variable ‘recommendation’ was included to capture whether the respondents had already been using less fertilizer than recommended. Those who use less fertilizers are likely to be aware of the potential adverse effects caused by chemical fertilizers, which, therefore, provides them with more justifications to use biochar as an alternative. We found that a quarter of farmers use less than recommended amount, whereas most of the farmers use about the same amount compared to recommendations.

Previous studies have shown that biochar can be an effective alternative to chemical fertilizers because it can increase crop yields, reduce nutrient leaching, and add nutrients to the soil (Dokoohaki et al., Reference Dokoohaki, Miguez, Laird and Dumortier2019; Zaid et al., Reference Zaid, Al-Awwal, Yang, Anderson and Alsunuse2024). Compared with chemical fertilizers, nutrients applied through biochar stay in the soil longer and are less likely to leach away, making them more available to plants when needed. Therefore, we expect to find those who are willing to try different management practices to reduce chemical fertilizer use more likely to learn or adopt biochar as a substitute for fertilizer. In the questionnaire, farmers were asked about their willingness to reduce the use of chemical fertilizer, using a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ and 5 = ‘strongly agree’. The mean value of 3.81 suggests that most farmers are willing to take measures to reduce fertilizer use. We further included a variable ‘ImproveSoil’ to capture the importance of improving soil health as a farm management goal. For those who view soil health as a more important goal, we expect to find a greater desire to try biochar since it could be applied to improve soil health. Five different importance levels were attributed, ranging from 1 = ‘not important’ to 5 = ‘extremely important’. A mean value of 4.2 indicates that farmers, on average, view improving soil health as between ‘very important’ and ‘extremely important’. Finally, the awareness of carbon programs was included as an indicator of farmers’ interest in carbon sequestration and conservation efforts. Slightly over half of farmers are aware of the carbon programs.

Empirical model

To examine the role that message framing plays in shaping producers’ decisions toward biochar, we estimated a bivariate probit model with the two binary variables in Table 2 serving as dependent variables. Due to the correlation between learning interest and desire to adopt in the future, we modeled the two correlated decisions on learning interest and adoption likelihood jointly with the same set of explanatory variables listed in Table 4.

The bivariate probit model is specified as follows:

Note that

![]() $ {y}_{1i}^{\ast } $

and

$ {y}_{1i}^{\ast } $

and

![]() $ {y}_{2i}^{\ast } $

are latent variables with their observed counterparts as

$ {y}_{2i}^{\ast } $

are latent variables with their observed counterparts as

![]() $ {y}_{1i} $

and

$ {y}_{1i} $

and

![]() $ {y}_{2i} $

. The observed counterparts are farmers’ binary decisions for learning interest and adoption likelihood for biochar, calculated based on the original responses as described in Tables 2 and 3. The same vectors of explanatory variables,

$ {y}_{2i} $

. The observed counterparts are farmers’ binary decisions for learning interest and adoption likelihood for biochar, calculated based on the original responses as described in Tables 2 and 3. The same vectors of explanatory variables,

![]() $ {x}_i $

, are used for both equations. Error terms are denoted as

$ {x}_i $

, are used for both equations. Error terms are denoted as

![]() $ {\varepsilon}_{1i} $

and

$ {\varepsilon}_{1i} $

and

![]() $ {\varepsilon}_{2i} $

, with a bivariate normal distribution,

$ {\varepsilon}_{2i} $

, with a bivariate normal distribution,

![]() $ BVN\left(0,0,1,1,\rho \right) $

, where

$ BVN\left(0,0,1,1,\rho \right) $

, where

![]() $ \rho $

is the tetrachoric correlation between two latent variables,

$ \rho $

is the tetrachoric correlation between two latent variables,

![]() $ {y}_{1i}^{\ast } $

and

$ {y}_{1i}^{\ast } $

and

![]() $ {y}_{2i}^{\ast } $

.

$ {y}_{2i}^{\ast } $

.

Unlike univariate statistics, the probit model allows us to isolate the effects of message framing while holding all the other variables constant. Note that

![]() $ \partial E\left({y}_{1i}^{\ast}\right)/\partial {x}_k $

=

$ \partial E\left({y}_{1i}^{\ast}\right)/\partial {x}_k $

=

![]() $ {\beta}_{1k} $

, which means that the coefficient estimate matrices,

$ {\beta}_{1k} $

, which means that the coefficient estimate matrices,

![]() $ {\beta}_1 $

and

$ {\beta}_1 $

and

![]() $ {\beta}_2 $

, measure how one unit change in one explanatory variable, holding the other factors fixed, affects the expected values of the latent variables. To understand the effects of explanatory variables on the expectation values of observed variables,

$ {\beta}_2 $

, measure how one unit change in one explanatory variable, holding the other factors fixed, affects the expected values of the latent variables. To understand the effects of explanatory variables on the expectation values of observed variables,

![]() $ E\left({y}_{1i}\right) $

and

$ E\left({y}_{1i}\right) $

and

![]() $ E\left({y}_{2i}\right) $

, we also computed the marginal effects. As our survey sample is relatively small, the marginal effect for each observation is computed first, which is the corresponding coefficient scaled by density function,

$ E\left({y}_{2i}\right) $

, we also computed the marginal effects. As our survey sample is relatively small, the marginal effect for each observation is computed first, which is the corresponding coefficient scaled by density function,

![]() $ {\phi}_2\left({x}_1,{x}_2,\rho \right) $

, then the mean value of all individual marginal effects is obtained (Greene, Reference Greene2012).

$ {\phi}_2\left({x}_1,{x}_2,\rho \right) $

, then the mean value of all individual marginal effects is obtained (Greene, Reference Greene2012).

Results and discussion

Interest in learning about biochar and future adoption plan

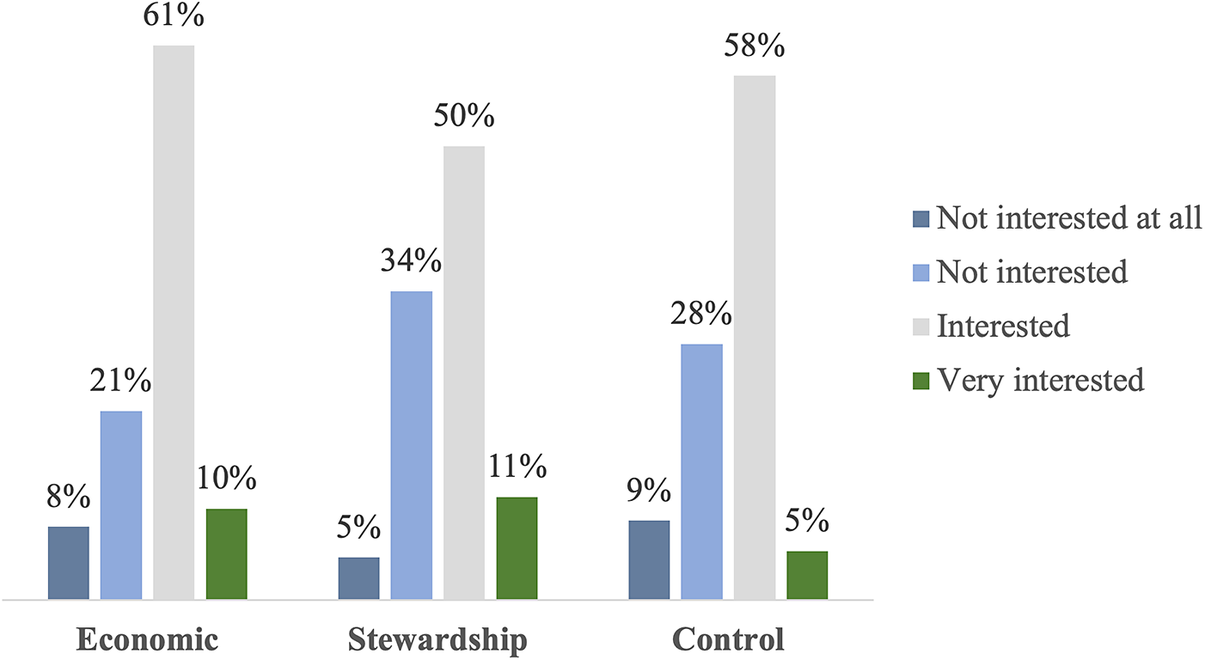

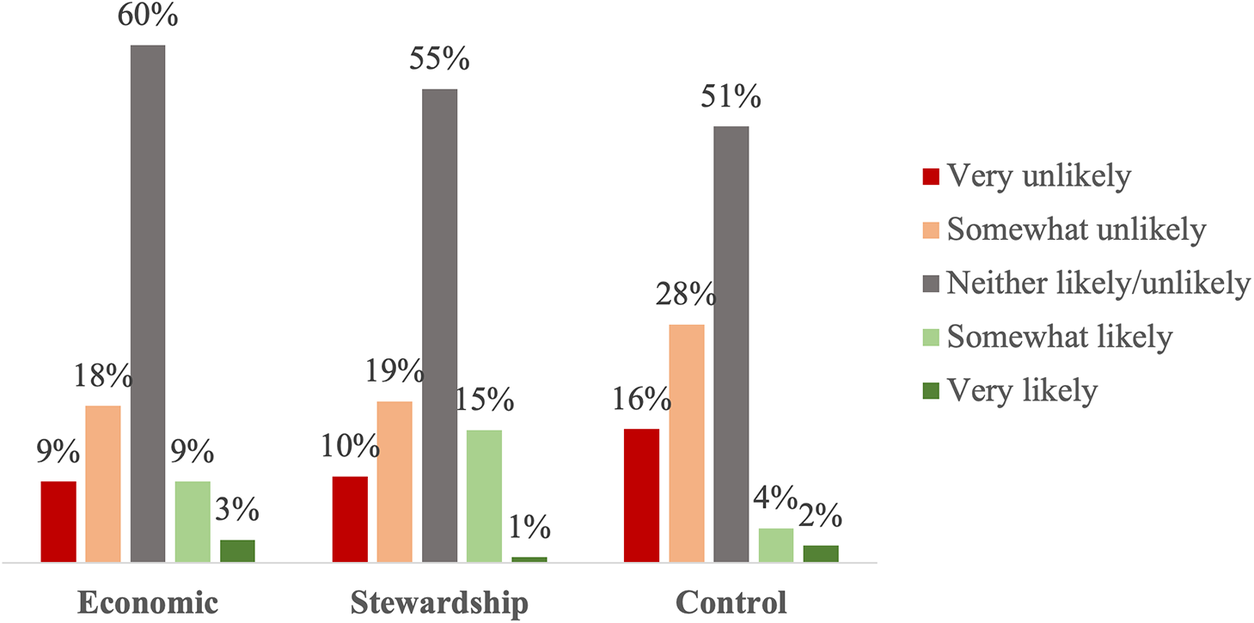

As indicated by Fig. 1, both economic and stewardship groups have very similar proportions (10%–11%) of farmers showing strong interest, which is more than doubled that of farmers in control groups (5%). In addition, the economic group had more farmers (61%) express a modest degree of interest in learning about biochar, followed by the control group (58%), whereas the stewardship group had the least proportion of producers showing modest interest (50%) (Fig. 1). We also checked farmers’ likelihood to use biochar as a soil amendment for the next 5 years. As demonstrated in Fig. 2, most of the farmers are uncertain about their future, and most farmers chose neither likely/unlikely for each of the three groups, ranging from 51% for the control group to 60% for the economic group. Among the control group, 28% of farmers indicated they are somewhat unlikely, and 16% indicated they are very unlikely to use biochar in the next 5 years. Yet the proportion of farmers who chose the two unlikely categories have dropped from over 40% in the control group to less than 30% in both economic and stewardship message frames.

Figure 1. Farmers’ interest in learning more about biochar: Categorized into three groups by the message they received (in economic, stewardship, and control frames).

Figure 2. Farmers’ likelihood of using biochar in the next 5 years: Categorized into three groups by the message they received (in economic, stewardship, and control frames).

Across all groups, very few producers choose the ‘very likely’ category (Fig. 2). This makes sense and indicates that farmers cannot make a certain decision about biochar use when they were provided with only a short paragraph of explanatory message. Nevertheless, the stewardship framing group recorded the highest percentage of farmers selecting ‘likely’ (15%), in comparison with the economic framing group (9%) and the control group (4%).

Estimations of the bivariate probit model

Table 4 presents bivariate probit model estimation results for learning interest and future adoption likelihood of biochar. The model is estimated with 383 observations, with estimated coefficient, standard error for the coefficient, and the marginal effect for each explanatory variable presented. Log-likelihood test shows the hypothesis that all coefficients in our model are equal to zero can be rejected at the 1% significance level. A pseudo-R

2 of 0.24 also demonstrates a reasonable fit of the estimated model. The correlation coefficient (

![]() $ \rho $

) between the bivariate outcomes is 1, which shows the perfect correlation between the two latent variables

$ \rho $

) between the bivariate outcomes is 1, which shows the perfect correlation between the two latent variables

![]() $ {y}_{1i}^{\ast } $

and

$ {y}_{1i}^{\ast } $

and

![]() $ {y}_{2i}^{\ast } $

that correspond to the binary decisions. This, in turn, justifies the joint estimation of the two decisions.

$ {y}_{2i}^{\ast } $

that correspond to the binary decisions. This, in turn, justifies the joint estimation of the two decisions.

The effect of message framing on biochar learning and usage likelihood decisions

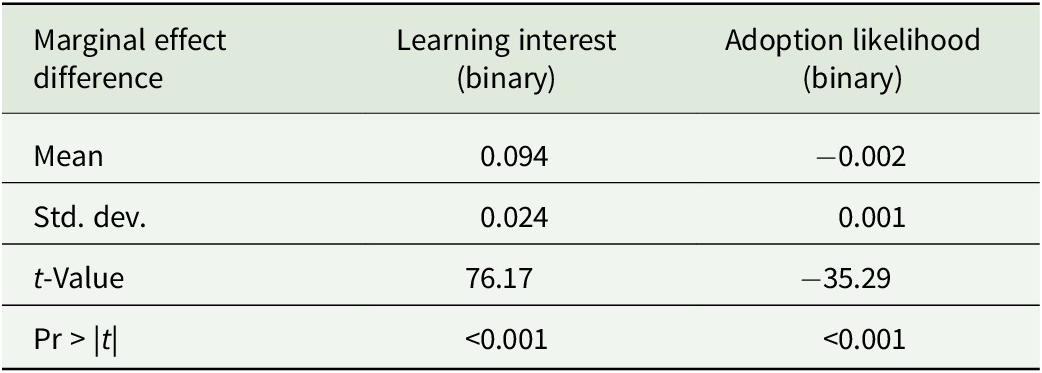

When compared with the control group producers, economic framing raised the probability of farmers’ interest in learning more about biochar by 11.7%. Yet the additional motivation provided by the stewardship message is less strong, and no significant difference is found in comparison with the control group (Table 5). The t-test result comparing the marginal effects of the two frames confirms the significantly higher incentive provided by economic framing in inspiring learning interest (Table 6).

Table 5. Bivariate probit model estimates for learning interest and future adoption likelihood of biochar

* p < 0.10.

** p < 0.05.

*** p < 0.01.

Table 6. Comparing marginal effects of economic framing and stewardship framing: t-test results

Note: Marginal effect difference is calculated as the marginal effect of economic framing minus the marginal effect of stewardship framing for each observation.

A possible reason for such difference in two framing works in promoting learning is that farmers who received an economic-related message are likely intrigued to know more about the scientific evidence from the experimental or field trials of biochar, including amount used, changes in cost, yield, and profitability. Furthermore, learning more about biochar from the economic perspective could provide feasible methods for those who are seeking ways to increase their margins from farming. However, those who received a message from a stewardship perspective may not see immediate results as the described benefits are either off-farm or some generations down the path. As such benefits are generally hard to quantify and translated into current farm-level benefits, the stewardship framing did not significantly enhance farmers’ learning desire compared with the control group.

Both economic and stewardship message frames significantly increased farmers’ indicated likelihood of biochar use in the next 5 years at a 5% significance level. Specifically, the likelihood of biochar uses in the next 5 years increased by 10.6% and 10.8%, respectively, for the economic and stewardship groups (Table 5). Although the difference between the marginal effects of these two frames seems minimal, the t-test finding shows that regarding future adoption likelihood, stewardship framing provides a statistically stronger incentive than economic framing (Table 6).

This shows that stewardship framing, while not significantly important in simulating further learning process, might play an important role in the adoption of conservation practices. Previous literature has found that farmer adoption decisions of conservation practices were jointly determined by the profit and stewardship motives (Chouinard et al., Reference Chouinard, Paterson, Wandschneider and Ohler2008; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Jin, Kasu, Jacquet and Kumar2019). In some cases, the land stewardship motivation could even outperform the profit motivation (Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Barkley, Chacón-Cascante and Kastens2012). Therefore, regarding new conservation practices such as biochar amendment, for which the economic benefit has not been quantified and verified, providing farmers stewardship-oriented messages related to biochar use will likely to be more effective than profit-oriented messages.

Effect of other factors on biochar learning and usage likelihood decisions

We found operators for farms with higher gross sales were more likely to express their interest in learning more about biochar, yet this did not translate into their likelihood of future adoption. Similar is true for farmers who used university Extension to make their fertilizer decisions, as we found those who used Extension were 9.7% more likely to indicate a learning interest. University Extension has been shown to play a visible role in enhancing knowledge and adoption rates of conservation practices (Wang, Reference Wang2019). According to Latawiec et al. (Reference Latawiec, Królczyk, Kuboń, Szwedziak, Drosik, Polańczyk, Grotkiewicz and Strassburg2017), information sources such as biochar conferences can enhance farmers’ familiarity with biochar, which in return sparks greater interests toward biochar application in practice. Therefore, university Extension could, in the future, organize more such learning events to expose farmers to comprehensive and in-depth information of biochar and to translate their learning interests more effectively to adoption decisions.

Farmers who experienced more drought conditions in the past 10 years are more likely to demonstrate a desire to learn, which makes sense as biochar helps keep water in the soil (Randolph et al., Reference Randolph, Bansode, Hassan, Rehrah, Ravella, Reddy, Watts, Novak and Ahmedna2017) and to, some degree, reduce the negative impact of drought, yet further demonstration is needed to turn the learning interest of this group into a greater desire to adopt. Not surprisingly, those who are interested in reducing fertilizer use showed a greater interest in learning, as biochar serves as an alternative to chemical fertilizer. Furthermore, we found farmers who are aware of the voluntary carbon programs are willing to learn more about biochar. This is likely because biochar could sequester carbon and could potentially qualify for the carbon program, given its substitution effect for chemical fertilizer (Gui et al., Reference Gui, Xu, Zhang, Hu, Huang, Zhao and Cao2025). In addition, farmers who have already applied less nitrogen than the required amount are 6.7% more likely to adopt biochar in the future. This indicates that environmentally oriented farmers are generally willing to try new practices that serve the same purpose.

Our findings also show that farmers who prioritize soil health improvement as a more important farm management goal indicated both a greater interest in learning and a higher likelihood of adopting biochar in the future. In this regard, our findings are similar to Adesina and Zinnah (Reference Adesina and Zinnah1993), whose findings showed that variables describing farmers’ perceptions were frequently significant in explaining adoption decisions. This result also suggests that future biochar promotion could be more effectively carried out by approaching interested farmers in the broader context of soil improvement strategies.

Comparing the findings across the two models, we can see that other than the two message framing variables, producers’ perceptions, program awareness, and past behaviors are the primary variables that will affect their intention to learn or to adopt biochar. For example, agreement with more drought conditions, willingness to reduce fertilizer use, priority with soil health improvement, and awareness of voluntary carbon programs all played a role in spurring learning interest. Meanwhile, farmers who previously used less nitrogen than recommended and those who regarded improving soil health as more important indicated significantly higher likelihood for biochar adoption. The reason that perception-related variables play primary roles in the learning and adoption likelihood model could be because both decisions are hypothetical and there is no actual cost involved. Therefore, other considerations, such as cost per acre and learning cost, which could be affected by farm sizes, are not important at this stage. If we were to study the actual adoption decisions, then we expect some more realistic factors also play a significant role, such as economies of scale and time horizon of planning, which are not accounted for in this study.

Discussion

While our study only covers biochar as a soil amendment, a conservation practice that is new to farmers in Eastern South Dakota, the margin of U.S. corn belt, our methodology and findings could be useful when designing message framing and promoting other new conservation practices in other regions as well. Our findings illustrate that even though stewardship framing message had lesser effect on the generation of learning interest compared with the economic message, it is a more effective way to incentivize farmers to adopt (Table 6). In many cases, stewardship consideration could be of equal importance and even more important than the monetary benefits. This highlights the importance of providing farmers with both economic and stewardship message in the promotion process, to stimulate learning interest and to convert such interest into adoption process.

Our results further show that when comparing messages that emphasize what matter most to the farmers, such as from economic or stewardship perspectives, messages that describe the practice in an informational manner but do not relate to farmers’ interest (control group) will generate much less interest. This indicates that, to incentivize farmers to adopt a certain conservation practice, communicators such as Extension specialists need to maximize the effectiveness of communication strategies by tailoring the message to the interest of the farmers. In other words, the farmers need to be assured that the benefits of using the new practice or product are aligned with their own interests.

This effect of targeted messaging has also been demonstrated in previous studies, where depending on the context, economic and stewardship framing messages may or may not influence farmers’ attitudes and behaviors (Krantz and Monroe, Reference Krantz and Monroe2016; Reddy et al., Reference Reddy, Wardropper, Weigel, Masuda, Harden, Ranjan, Getson, Esman, Ferraro and Prokopy2020). For example, Krantz and Monroe (Reference Krantz and Monroe2016) have shown that appealing to the public environmental benefits has generated either moderate increase or decrease in farmers’ conservation intention or behavior. The reason could be that farmers are not as interested in public environmental benefits as in their own profit. However, some studies also showed that even under the economic frame, no positive outcome in conservation was induced (e.g., Reddy et al., Reference Reddy, Wardropper, Weigel, Masuda, Harden, Ranjan, Getson, Esman, Ferraro and Prokopy2020). In such cases, the conservation actions being promoted are generally well known and have been used by some farmers (e.g., cover crops), and it is likely that respondents have already formed their own opinions on the practice. Before the surveyed farmers read the economic framing message, they likely have already learned from other farmers about the high costs of cover crops and other challenges of adopting them. In such cases, farmers will doubt the credibility of the message, as it conflicts with the view they have previously formed (Gromet, Kunreuther and Larrick, Reference Gromet, Kunreuther and Larrick2013). Therefore, message framing will likely be more useful in promoting practices that are rarely used, for which farmers have not already formed their views yet. The effect of message framing will be greatly compromised for practices that have been used on a wide scale, due to the biased opinions people have formed prior to the survey.

Conclusion

Although biochar has been shown to have numerous benefits when being used as a partial substitute to chemical fertilizer, communications of such benefits to farmers are generally lacking. To help evaluate the effectiveness of different message framing, we conducted a survey among crop producers in Eastern South Dakota. Our findings show that compared with the control group who received the informational description of biochar, survey respondents randomly assigned to receive the economic-framed message indicated greater learning interest and higher likelihood of adoption. Stewardship-framed message, though demonstrated no effect in simulating greater learning interest, have a stronger effect on the adoption likelihood compared with the control-framed messages.

The findings of this article highlight the importance of communicating to farmers in message frames that emphasize the aspects of outcome that align with their own interests. In our case, most farmers are deeply interested in both economic profitability and stewardship of their land, which explains why both economic and stewardship message frames showed positive impacts on producers’ future adoption likelihood of biochar. Therefore, future outreach communications should focus on both established economic and stewardship benefits when conveying information about conservation practices to farmers.

A caveat to note is that for some conservation practices that are more well known to farmers such as cover crops, the effect of message framing could be weak or even nonexistent. This is because many farmers, even nonadopters, would have formed their own opinions on such practices by observing neighborhood adopters and they may deem the message framing contradicting with their preknowledge as not credible. More future work can be carried out in this regard on how the effectiveness of message framing could differ for practices that have varying degrees of awareness among farmers. Furthermore, our experimental study was carried out in Eastern South Dakota, which may limit the scope of the results. Future research could target a broader geographical area with a larger and more diverse farmer sample, which could help validate and extend the conclusions drawn from this study, while assessing farmers’ attitudinal and behavioral changes when facing varying soil management and weather challenges.

Funding statement

Financial support for this work was provided by South Dakota State University.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical standard

This research was approved by South Dakota State University’s Institutional Review Board.

AI declarations

The authors declare that no AI tools were used in writing this article.