About one-third of tertiary patients treated for epilepsy remain drug-resistant despite recent advances and the availability of multiple anti-seizure medications (ASMs). Reference Sultana, Panzini and Veilleux Carpentier1 If seizures persist after trials of two appropriately chosen and adequately dosed ASMs, the likelihood of achieving seizure freedom with a third ASM falls below 5% and declines further with each subsequent trial. This prognosis has not improved in recent decades despite the development of new ASMs. Reference Chen, Brodie, Liew and Kwan2

Cenobamate (CNB) is a new ASM approved by the FDA in 2019 and used as an adjunct treatment for refractory focal seizures. Its mechanism of action relies on the suppression of persistent sodium currents (I NaP) as well as positive allosteric modulation of GABAA receptors. Reference Chung, French and Kowalski3 The efficacy and safety of CNB have been demonstrated through two double-blind, randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Reference Chung, French and Kowalski3,Reference Krauss, Klein and Brandt4 The long-term efficacy, safety and tolerability of the drug have been confirmed by an additional open-label study and associated post hoc analyses. Reference Sperling, Klein and Aboumatar5,Reference Sperling, Abou-Khalil and Aboumatar6 Although RCTs are the most unbiased method for assessing the efficacy of an intervention, they are conducted under highly controlled conditions with selected patient populations, thus limiting the generalizability of their conclusions to the broader population. These constraints were evident in the pivotal CNB trials, Reference Chung, French and Kowalski3,Reference Krauss, Klein and Brandt4 which excluded patients with certain characteristics (such as a history of substance use, major psychiatric disorders or drug hypersensitivity) and imposed certain conditions, including a fixed titration schedule and a maximum number of concomitant ASMs.

Although approved by Health Canada in June 2023 as adjunctive therapy for focal seizures in adults with epilepsy, CNB only became reimbursable through provincial public drug plans starting March 2025 following arduous pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance pricing negotiations. The recent introduction of CNB into clinical practice in Canada presents an opportunity to conduct observational studies to assess its efficacy and tolerability in real-world clinical settings.

We conducted a retrospective study using data from electronic medical records of patients followed at the Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM) epilepsy clinic. The study protocol was approved by the CHUM research ethics board. We included patients with drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE) who began CNB therapy between January 2023 and November 2024, with either ≥3-month follow-up data or who discontinued the medication due to adverse events (AEs). Patients with neurodegenerative disease (n = 1) or insufficient data in medical records (n = 15) were excluded. Primary endpoints were percentage seizure reduction and responder rates (≥50%, ≥75% and ≥90%) at 3-month, 6-month and 12-month follow-up. Percentage seizure reduction was calculated for each patient by comparing their 30-day seizure frequency at baseline to that at their 3-month, 6-month and 12-month follow-ups (all seizure types were included including focal preserved consciousness seizures). Thirty-day seizure frequency at each follow-up was assessed over the 3-month period preceding each appointment. Seizure frequency was also assessed categorically at each follow-up visit as either (a) daily (at least one seizure per day), (b) weekly (at least one seizure per week, but not every day), (c) monthly (at least one seizure per month, but not every week), (d) quarterly (at least one seizure every 3 months, but not every month) and (e) seizure-free (no seizures over the last 3 months). The secondary endpoints were the frequency of AEs and the treatment discontinuation rate. AEs were only considered if deemed related to CNB by the treating physician. For each patient, standard baseline demographic and epilepsy data were collected: age, sex, etiology of epilepsy, seizure type(s) present in the 12-month period prior to initiation of CNB, time since epilepsy diagnosis, age of diagnosis, prior/concomitant ASMs, previous vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) trial, prior epilepsy surgery, presence of intellectual disability, prior episode of status epilepticus and 30-day seizure frequency. Descriptive analyses of the collected variables were performed to evaluate all primary and secondary endpoints. The median was used to represent variables and endpoints that did not follow a normal distribution (i.e., 30-day seizure frequency, % seizure reduction) to ensure a clearer representation of central tendency. Additional analyses were conducted to study the association between CNB dose and % seizure reduction. To do so, a two-tailed Student’s t-test assuming equal variance was conducted, comparing the % seizure reduction in patients receiving low-dose CNB (<200 mg/day) versus those receiving high-dose CNB (≥200 mg/day) at the last available follow-up.

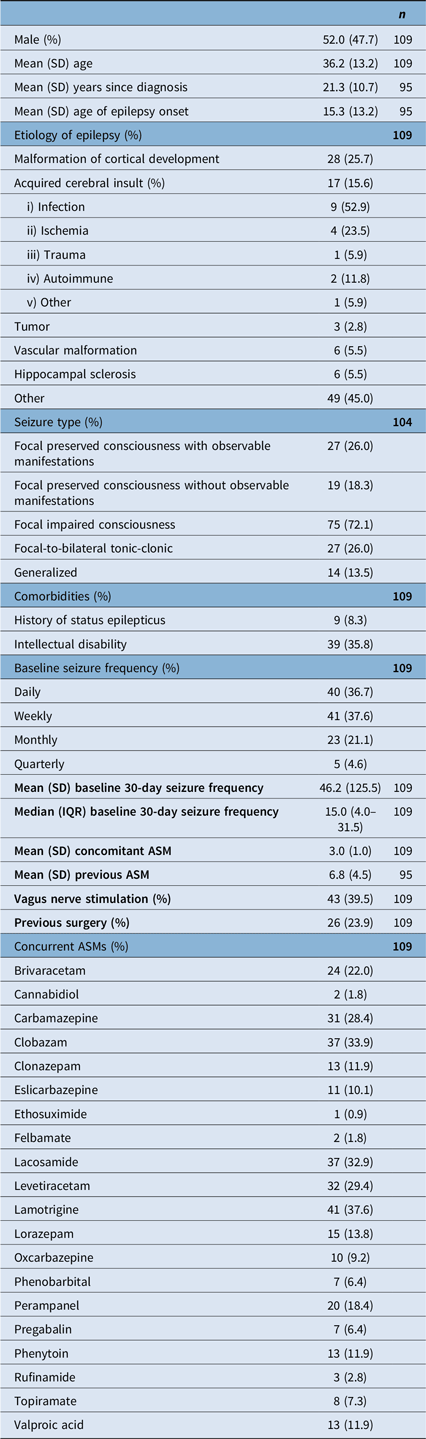

A total of 109 patients were included in our analysis. Although the number of patients at each follow-up time point varies (n = 68 at 3 months, n = 53 at 6 months and n = 54 at 12 months), these assessments represent a total of 109 distinct patients. This is explained by the fact that some patients missed earlier follow-ups but completed later ones, while others have not yet reached subsequent time points at the time of analysis. At baseline, mean age was 36.2 (SD: 13.2) years. Median 30-day seizure frequency was 15 (IQR: 4.0–31.5). Patients were on a mean of 3.0 (SD: 1.0) concurrent ASMs and had attempted a mean of 6.8 (SD: 4.5) ASMs. 39.5% of patients had prior or active VNS therapy, and 23.9% had previously undergone epilepsy surgery. 8.3% of patients had a prior history of status epilepticus, and 35.8% had some degree of intellectual disability. Baseline demographic and epilepsy data are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics

SD = standard deviation; IQR = interquartile range; ASM = anti-seizure medication.

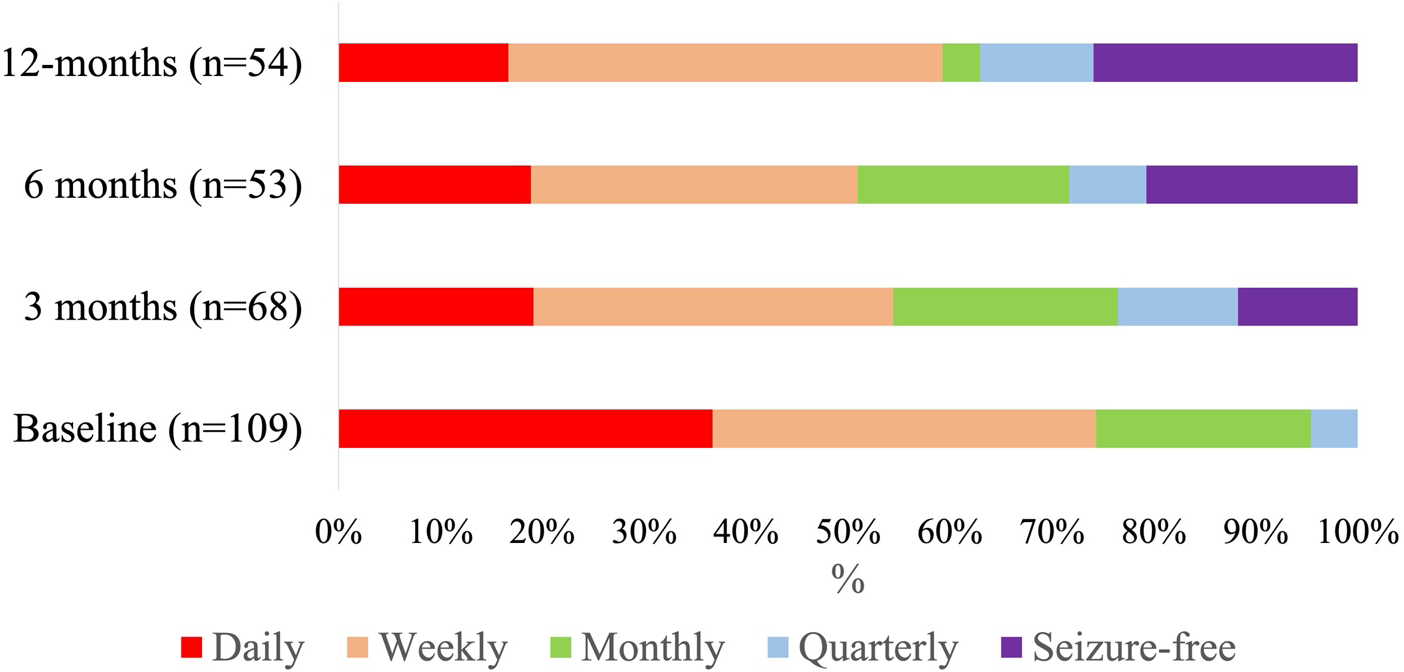

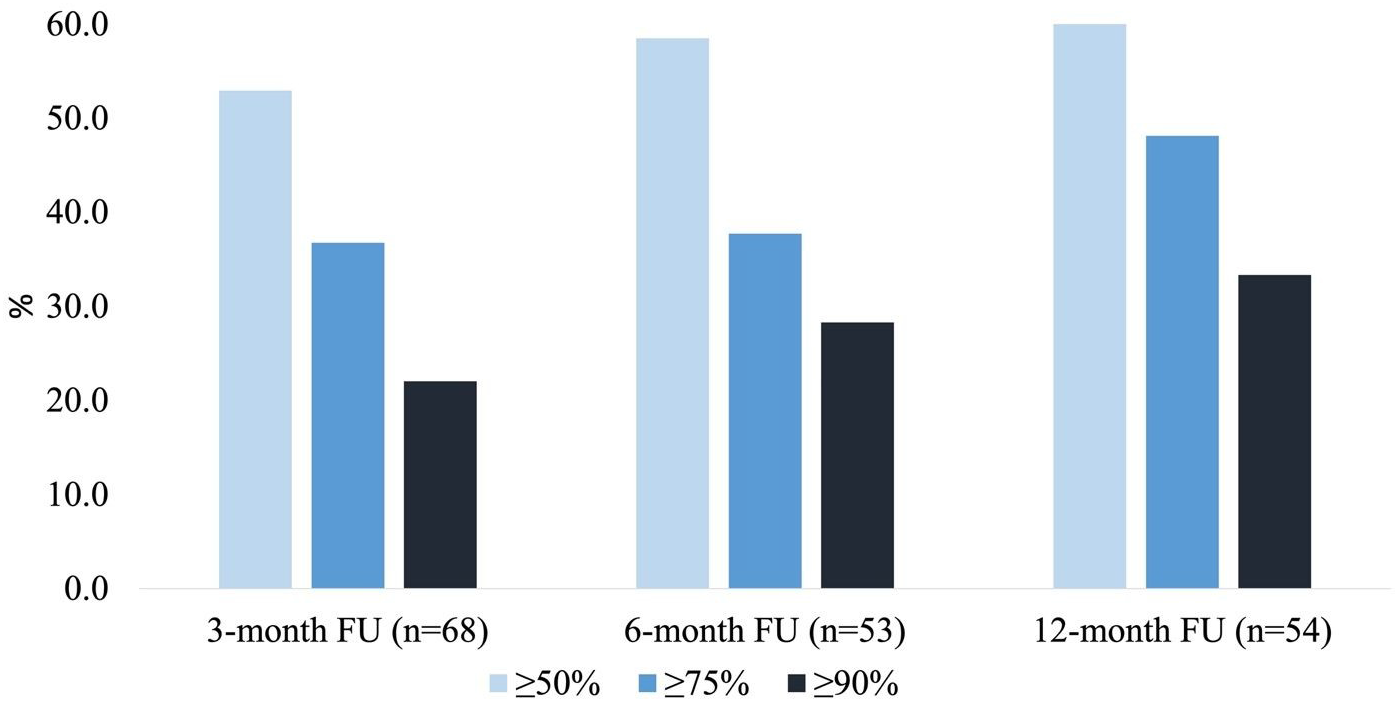

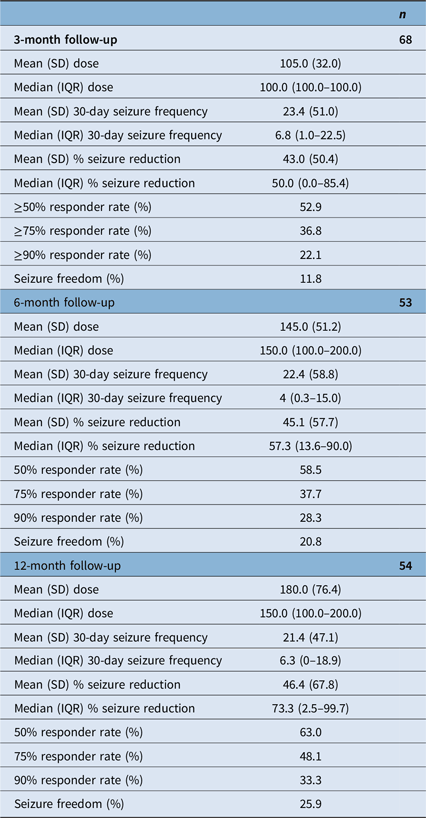

At 3-month follow-up, the mean and median CNB dose were 105.0 mg per day (SD: 32.0) and 100.0 mg per day (IQR: 100.0–100.0, range: 12.5–150.0), respectively. Median 3-month % seizure reduction was 50.0% (IQR: 0.0–85.4%, n = 68). The ≥50%, ≥75% responder rates and seizure freedom rates were 52.9%, 36.8% and 11.8%, respectively. At 6-month follow-up, mean and median CNB dose were 145.0 mg per day (SD: 51.2) and 150 mg per day (IQR: 100.0–200.0, range: 50.0–300.0), respectively. Median 6-month % seizure reduction was 57.3% (IQR: 13.6–90.0%, n = 53). The ≥50%, ≥75% responder rates and seizure freedom rates were 58.5%, 37.7% and 20.8%, respectively. At 12-month follow-up, mean and median CNB dose were 180.0 mg per day (SD: 76.4) and 150 mg per day (IQR: 100.0–200.0, range: 100.0–400.0), respectively. Median 12-month % seizure reduction was 73.3% (IQR: 2.5–99.7%, n = 54). The ≥50%, ≥75% responder rates and seizure freedom rates were 63.0%, 48.1% and 25.9%, respectively. Results are summarized in Table 2. Seizure frequency reduction and responder rates are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 1. Seizure frequency during cenobamate treatment. Thirty-day seizure frequency was categorically assessed at 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up appointments (daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly and seizure-free). The % of patients categorized as “seizure-free” steadily increased with increased treatment duration.

Figure 2. Cenobamate responder rates. ≥50%, ≥75% and ≥90% responder rates were evaluated at 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up appointments, respectively. Responder rates increased steadily with increased treatment duration.

Table 2. Cenobamate efficacy at 3−, 6- and 12-month follow-up

SD = standard deviation; IQR = interquartile range.

Our analysis showed a greater mean % seizure reduction among patients on low-dose CNB (50.6%, SD: 44.8, n = 77) compared with those on high-dose CNB (33.0%, SD: 77.0, n = 32); however, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.14). Among patients who were seizure-free at last follow-up, the mean CNB dose was 158.8 mg/day (SD: 76.6) and the median dose was 125 mg/day (IQR: 100.0–200.0).

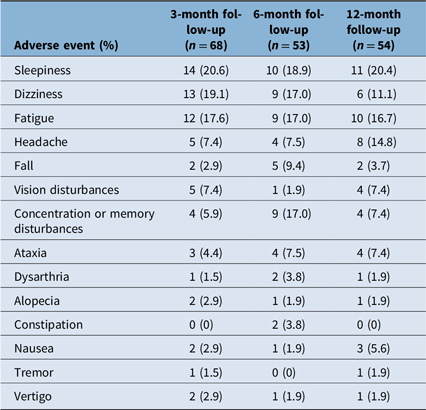

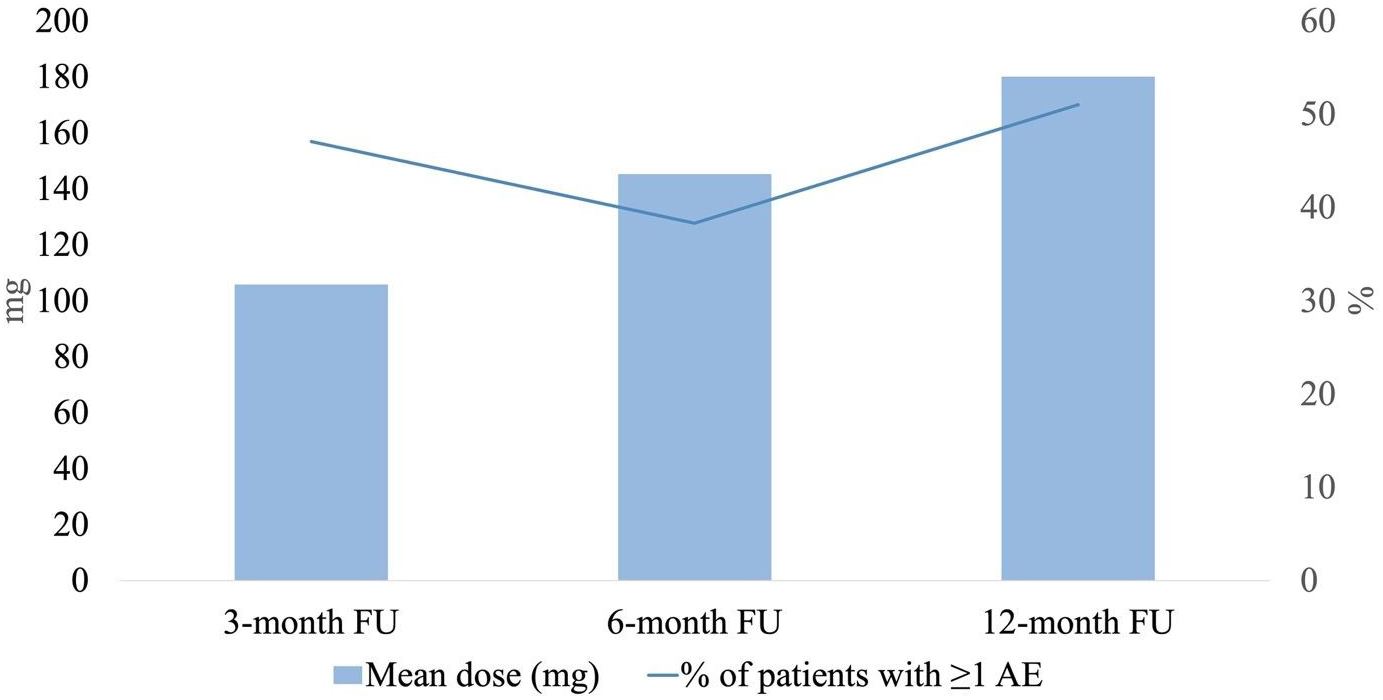

The main AEs of CNB treatment at 3-month follow-up were sleepiness (20.6%), dizziness (19.1%), fatigue (17.6%), headache (7.4%) and vision disturbances (7.4%). At 6-month follow-up, the main AEs were sleepiness (18.9%), dizziness (17.0%), fatigue (17.0%), concentration or memory disturbances (17.0%) and fall (9.4%). At 12-month follow-up, the main AEs were sleepiness (20.4%), fatigue (16.7%), headache (14.8%), dizziness (11.1%), ataxia (7.4%) and concentration or memory disturbances (7.4%). The percentage of patients who experienced AEs at 3-month, 6-month and 12-month follow-up was 47.1%, 38.3% and 51.0%, respectively. Moreover, 8.3% of patients discontinued CNB (n = 9). Four patients discontinued CNB due to intolerable AEs, four patients discontinued CNB due to intolerable AEs combined with treatment inefficacy and one patient discontinued CNB due to an increase in seizure frequency. The mean treatment duration before discontinuation was 5.6 (SD:1.5) months. There were no reports of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. The frequency of AEs is summarized in Table 3 and Figure 3.

Table 3. Cenobamate adverse events at 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up

Figure 3. Frequency of adverse events (AEs) with cenobamate (CNB) at 3-month, 6-month and 12-month follow-ups. The percentage of patients experiencing AEs did not seem to correlate with an increase in CNB dose.

Current literature supports CNB as an effective treatment option for patients with DRE. Our single-center experience contributes to the emerging body of real-world evidence surrounding this relatively novel ASM, with results corroborating those reported in pivotal trials, open-label studies and post hoc analysis. Reference Chung, French and Kowalski3–Reference Sperling, Abou-Khalil and Aboumatar6 More recently, a 2023 meta-analysis pooling data from seven studies analyzing the efficacy of CNB in a real-world setting found similar results, with a ≥50% responder rate of 68%, seizure freedom in 16.2% of patients and a 12-month retention rate of 90%. Reference Makridis and Kaindl7

Our analysis showed a greater mean % seizure reduction among patients on low-dose CNB compared to those on high-dose CNB, though the difference remained statistically nonsignificant. Our findings align with those of a previously published real-world study, which also reported no significant difference in responder rates between patients on high- versus low-dose CNB. Reference Villanueva, Santos-Carrasco and Cabezudo-García8 This contrasts with clinical trial data, Reference Chung, French and Kowalski3,Reference Krauss, Klein and Brandt4 likely reflecting indication bias in real-world settings, where more refractory patients are often escalated to higher doses, while those with favorable early responses remain on lower doses.

Interestingly, the percentage of patients experiencing AEs did not appear to increase with higher CNB doses. This observation is likely explained by physicians proactively adjusting concomitant ASM doses during CNB titration, as recommended by Smith et al. Reference Smith, Klein and Krauss9 More specifically, proactive dose reductions of clobazam, lacosamide, phenytoin and phenobarbital were systematically implemented, with all four requiring adjustments by the time CNB titration reached 50 mg/day, while reactive modifications of other ASMs were undertaken in response to patient-reported AEs. Reference Smith, Klein and Krauss9 Moreover, the literature indicates a synergistic interaction between CNB and clobazam, emphasizing the need for clobazam dose reduction when CNB is titrated to 25–100 mg/day. Reference Osborn and Abou-Khalil10 Conversely, initiation of low-dose clobazam has been recommended in patients demonstrating an incomplete response to CNB. Reference Osborn and Abou-Khalil10

This study is limited by its retrospective design and lack of a control group. There was also a reliance on self-reported seizure frequency as noted in the chart by the treating physician, which was not systematically documented using seizure calendars. Follow-up at 3-, 6- and 12-month intervals was also inconsistent due to missed appointments or scheduling issues. Nevertheless, our findings offer valuable preliminary insight into the real-world effectiveness and safety of CNB. Although we did not compare CNB to other ASMs, our efficacy results, particularly the 12-month seizure freedom rate of 25.9%, well exceed what would be expected from a standard adjunctive ASM in DRE patients, based on previous literature and our own experience with this population.

Consistent with results from pivotal trials and real-world data, our data support CNB as a safe and uncommonly effective treatment option for patients with DRE.

Author contributions

TE was responsible for study conception, data collection and analysis, figure preparation and drafting of the manuscript.

VL, AAB, SLR and MRK reviewed the manuscript critically for intellectual content.

DKN was responsible for study conception, oversaw data collection and analysis and reviewed the manuscript critically for intellectual content.

Funding statement

Funding in the form of a publication logistical support grant was provided by Paladin Labs Inc. in April 2025.

Competing interests

DKN has received honorarium for conferences and participation in advisory boards for Liva Nova, UCB Canada, Paladin Pharma Inc., Eisai Inc. and Novartis. He also received a publication logistical support grant from Paladin Labs Inc. The publication logistical grant was originally granted by Paladin Pharma Inc. in April 2025. As of June 17, 2025, Knight Therapeutics Inc. acquired the Paladin business in Canada. DKN is also supported by the Canada Research Chair Program (CRC-2022-00358). MRK reports unrestricted educational grants from Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Paladin. TE, VL, AAB and SLR have no conflicts of interest. Authors had complete editorial control over the manuscript’s content.