Highlights

-

Cancer patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) are increasing; thrombolysis benefit remains uncertain.

-

In this post-hoc analysis of the AcT trial, we found AIS with cancer leads to worse outcomes, longer hospital stays, and higher mortality, but no differences in bleeding-related complications compared to those without cancer.

-

Larger studies with prospective data are warranted.

Introduction

There is an increased prevalence of patients with cancer due to improved cancer screening and diagnostic methods, novel targets for cancer treatment and reduced cancer-related mortality. Reference Sonkin, Thomas and Teicher1,Reference Siegel, Miller, Fuchs and Jemal2 Thus, the number of patients with cancer presenting with acute ischemic stroke is increasing. Reference Sanossian, Djabiras, Mack and Ovbiagele3 Hyperacute recanalization therapies such as thrombolysis or endovascular thrombectomy have become the mainstay of treatment for acute ischemic stroke, but cancer patients have been classically offered these acute treatments less often compared to non-cancer patients, due to fear of increased complications and perceived poor prognosis. Reference Owusu-Guha, Guha and Miller4 However, systematic reviews and cohort studies have not identified an increased risk of intracranial hemorrhage with thrombolysis in patients with cancer compared to non-cancer patients, though these studies were all retrospective cohorts, largely based on administrative data, and therefore likely reflect a high prevalence of selection bias. Reference Otite, Somani, Chaturvedi and Mehndiratta5–Reference Murthy, Karanth and Shah8 . Clinical trials often exclude patients with limited life expectancy, thereby excluding many patients with active cancer. However, the phase-3 Canadian AcT (Alteplase compared to Tenecteplase) trial (NCT03889249) was a registry and administrative data-linked pragmatic trial that included all patients who were eligible for thrombolysis, as per the treating physician’s discretion, regardless of their premorbid status, which included concomitant diagnosis of cancer. Reference Sajobi, Singh and Almekhlafi9,Reference Menon, Buck and Singh10 While some patients with cancer may have been selectively excluded from AcT if physicians felt that the risks of randomization (and the potential to get thrombolysis) would outweigh the benefits, it still represents one of the few pragmatic hyperacute stroke trials where active cancer status was not an exclusion criterion. Here, we present a post hoc analysis of the AcT trial comparing 90-day outcomes in patients with cancer versus patients without cancer. We hypothesize that cancer patients had worse functional outcomes and increased mortality, with an increased risk for symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage.

Methods

Ethics approval and patient consent

Ethics approval and individual patient consent were not necessary as this was a post hoc analysis of a previously conducted randomized controlled trial.

Data source

AcT was a pragmatic, multicenter, open-label, registry-linked, randomized, controlled, non-inferiority trial comparing intravenous (IV) tenecteplase (0.25 mg/kg) to alteplase (0.9 mg/kg) in patients presenting with acute ischemic stroke within 4.5 h from symptom onset (NCT03889249). Trial design and results have been previously described. Reference Sajobi, Singh and Almekhlafi9,Reference Menon, Buck and Singh10

Patients

All consented patients in the trial were included for analysis. We used International Classification of Diseases – 10th edition (ICD-10) codes linked with administrative data from the Canadian Institute of Health Information to identify baseline comorbidities, including a diagnosis of cancer. ICD-10 codes used to identify cancer are outlined in Supplemental Materials Table S1. All subtypes of cancer were included for analysis, except for non-melanoma skin cancer due to their benign natural history and high prevalence of misclassification and central nervous system tumors. We attempted to delineate the temporal association between cancer and stroke using comorbidity type codes according to the Discharge Abstract Database metadata (Supplemental Materials Table S2), but most cancer diagnoses were not associated with a code type. To maximize our sample size, we included any diagnosis type, which encompassed any subjects with active cancer or a prior history of cancer. Outcome assessment was done by central blinded assessors at 90 days as part of the clinical trial protocol. Imaging analysis was similarly done in the central core lab with experienced members blinded to treatment assignment and outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Our primary outcome was the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) 0–2 at 90 days. Secondary outcomes included mRS 0–1, ordinal mRS, return to pre-stroke function and quality of life as measured by the EQ5D visual analogue scale (EQ5D VAS). Safety outcomes included any intracranial bleeding, symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, peripheral bleeding requiring blood transfusions and mortality. Unadjusted odds ratios for each of the covariates were calculated individually for the primary outcome of interest. A multivariable logistic regression model was constructed to assess the association between cancer and the binary outcomes, adjusting for age, sex, baseline stroke severity measured by National Institute of Health Stroke Severity score (NIHSS) and time from onset to thrombolysis. Effect measures are reported as adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). For continuous outcomes, a generalized linear regression model was used, with logarithmic-transformed values of the outcomes for skewed data. The coefficients of predictors were exponentiated to get the adjusted risk ratios (aRR) with 95% CI. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided p-value < 0.05. Lastly, we performed ordinal shift analysis for the mRS according to the presence or absence of cancer. All analyses were conducted using R (version 2024.12.1 + 563).

Results

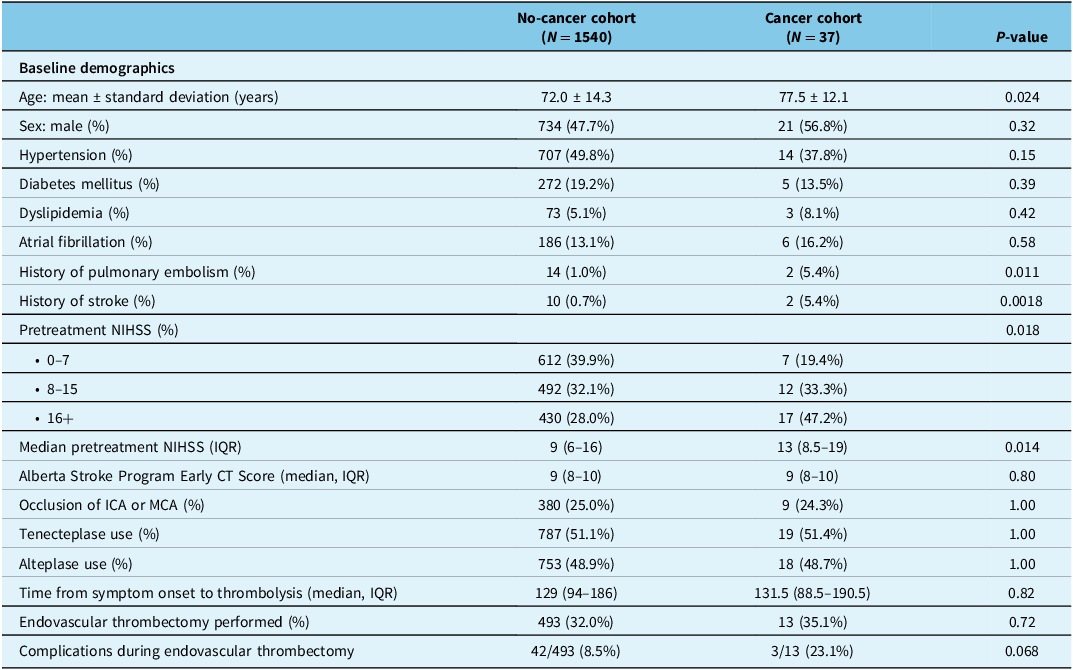

Of the 1577 patients who consented in the trial, 1540 (97.7%) patients had no history of cancer, while 37 (2.3%) patients had either prior history or active cancer at the time of presentation. Cancer patients were older than non-cancer patients: 77.5 ± 12.1 years versus 72.0 ± 14.3 years (p = 0.024). Baseline vascular risk factors including the presence of hypertension, atrial fibrillation, dyslipidemia and diabetes mellitus were similar between the cancer and non-cancer groups (Table 1). Cancer patients had a higher prevalence of pulmonary embolism and previous ischemic stroke (2/37 [5.4%] vs 14/1540 [1.0%], p = 0.011 and 2/37 [5.4%] vs 10/1540 [0.7%], p = 0.0018, respectively). Median NIHSS was higher in cancer patients (13 [IQR 8.5–19] vs 9 [IQR 6–16], p = 0.014), despite similar Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS) scores and proportion of patients with internal carotid artery or middle cerebral artery occlusions (Table 1). There were no differences in the proportions of patients who were treated with tenecteplase versus alteplase (see Table 1). There were 13/37 patients in the cancer group (35.1%) who received endovascular thrombectomy (EVT), compared with 493/1540 patients (32.0%) in the non-cancer group. There was a nonsignificant higher number of complications in the cancer group – 3/13 (23.1%) versus 42/493 (8.5%), p = 0.068. Of the three complications in the cancer group, two had experienced distal emboli to the target vessel territory, and one had vessel perforation during EVT.

Table 1. Baseline demographics, treatment characteristics and 90-day outcomes comparing AcT patients with and without a history of cancer and/or active cancer

AcT = Alteplase compared to Tenecteplase; ICA = internal carotid artery; IQR = interquartile range; MCA = middle cerebral artery; NIHSS = National Institute of Health Stroke Severity score.

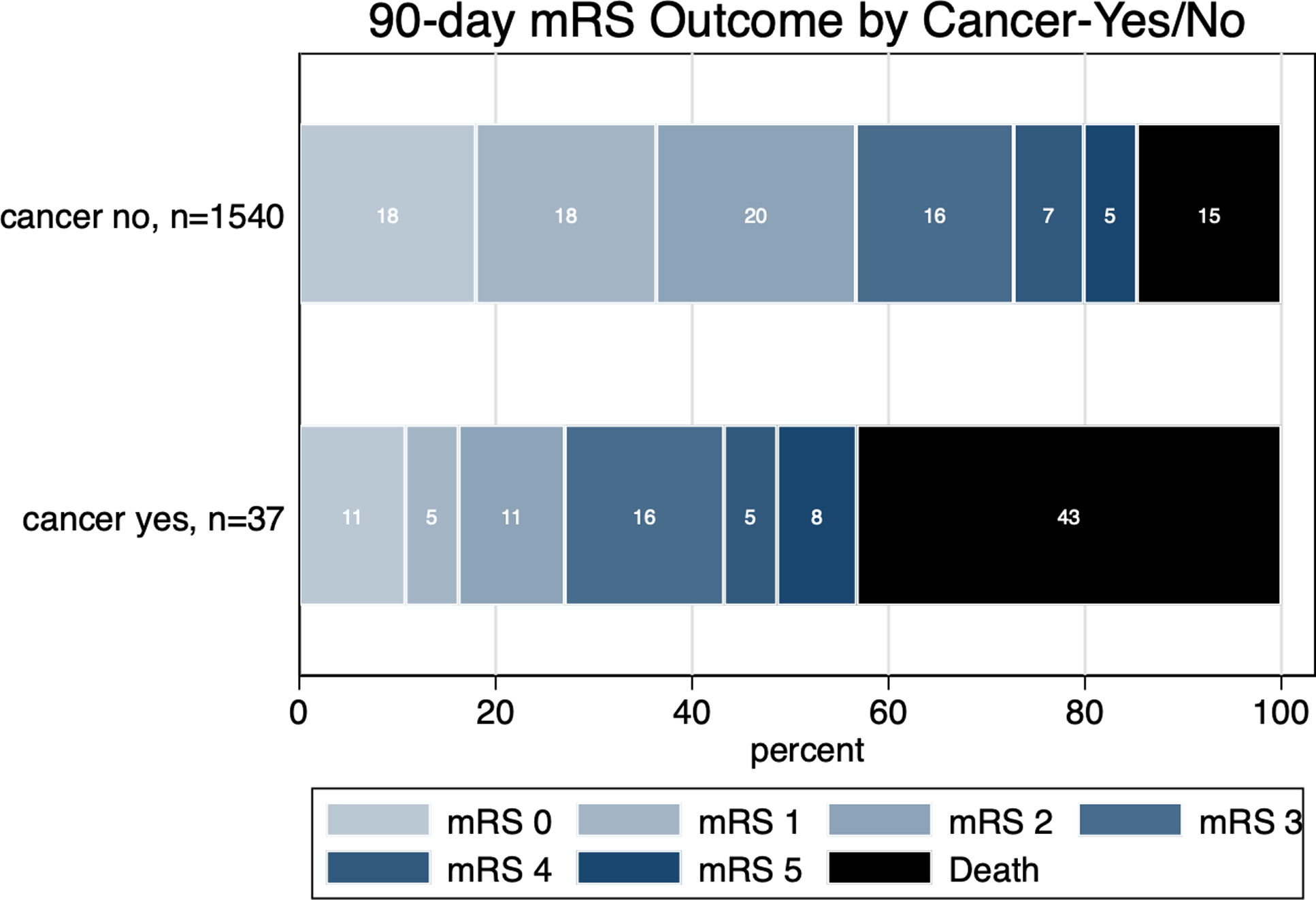

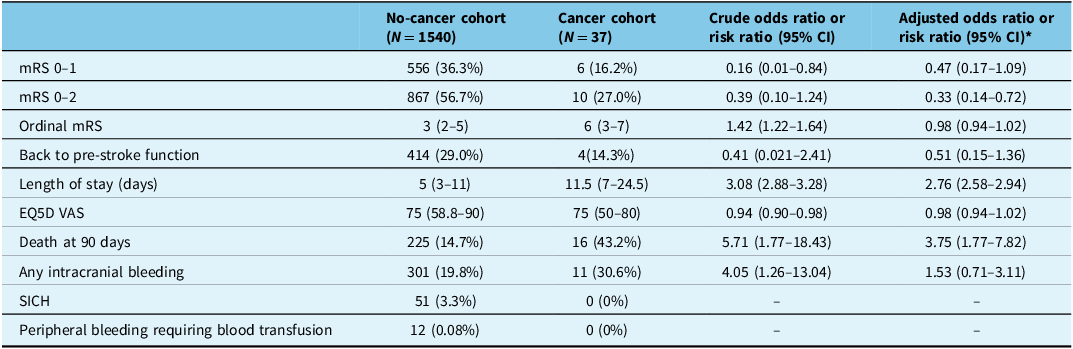

At 90 days, patients with cancer had significantly lower rates of mRS 0–2 at 90 days (27% vs 56.7%, aOR 0.92, 95% CI 0.91–0.94; Figure 1) and had more prolonged hospital stay as compared to those without cancer (median 11.5 [IQR 7–24.5] days vs 5 [IQR 3–11] days, respectively, aRR 2.76 [95% CI 2.58–2.94]). There was no difference in other functional outcomes, including quality of life as measured by the EQ5D VAS (Table 2). In terms of safety outcomes, 90-day mortality was higher in patients with cancer as compared to those without cancer (43.2% vs 14.7%, aOR 3.75, 95% CI 1.77–7.82). There were no bleeding events including intracranial and peripheral bleeding requiring blood transfusion in patients with cancer. All other safety outcomes were not statistically significant between the two groups.

Figure 1. Proportion of patients achieving various 90-day modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores according to the presence or absence of cancer.

Table 2. 90-day outcomes stratified by the presence or absence of active cancer or a history of cancer. Crude and final adjusted odds ratios are presented

CI = confidence interval; EQ5D VAS = EQ5D visual analogue scale; mRS = modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS = National Institute of Health Stroke Severity score; SICH = symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage.

* The adjusted odds ratios are adjusted for age, pretreatment NIHSS and time from onset to needle.

Discussion

In this study, we found that patients with a history of cancer and acute ischemic stroke who received thrombolysis were less likely to achieve functional independence and had longer lengths of hospital stay, worse ordinal modified Rankin scores and higher rates of mortality at 90 days compared to patients without a history of cancer. These results are novel, as there is no randomized controlled trial data evaluating the efficacy and safety of thrombolysis in patients with a history of cancer, and previously reported data on this understudied subgroup came from retrospective cohorts or administrative data using alteplase. Data on the use and safety of tenecteplase in this subgroup have not yet been published.

A 2023 systematic review of systemic thrombolysis in patients with acute stroke and active cancer found that IV thrombolysis was not associated with a significant increase in the incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage (OR 1.35, 95% CI 0.85–2.14, I2 76%) or all-cause mortality (OR 1.26, 95% CI 0.91–1.75, I2 71%) compared to patients without cancer. Reference Mosconi, Capponi and Paciaroni6 Only 6 out of 11 studies reported data on disability, and there was no difference between active cancer and non-cancer patients for achieving a good functional outcome (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.35–1.49, I2 59%). All 11 studies included in this systematic review came from stroke registries or administrative data, and 10/11 studies were based exclusively on retrospective data. The potential for selection bias in these studies is high, and it is likely that cancer patients included in these studies had lower risks of bleeding (i.e., less proportion of patients with gastrointestinal cancers, thrombocytopenia or presence of metastases). Furthermore, all of these studies were conducted using alteplase, since evidence supporting the use of tenecteplase over alteplase did not emerge until recent years. Reference Menon, Buck and Singh10–Reference Wang, Hao, Wu, Wu, Fisher and Xiong12

There are no specific recommendations surrounding the use of IV thrombolysis in cancer patients in international stroke guidelines, given the lack of high-level evidence in this patient population. The American Heart Association guidelines from 2019 state that patients with systemic cancer and reasonable (defined as 6 months or greater) life expectancy may benefit from IV thrombolysis. Reference Powers William, Rabinstein Alejandro and Teri13 The 2021 European Stroke Organization guidelines on IV thrombolysis state that “cancer should not be an absolute contraindication against thrombolytic treatment, although caution seems appropriate.” Reference Berge, Whiteley and Audebert14 The basis for this recommendation is from a single-center, retrospective observational study of 11 patients with nonmetastatic cancer, which found that 7/11 (73%) patients achieved functional independence at 3 months. Reference Cappellari, Carletti and Micheletti15 However, given the features of the highly selected cohort (i.e., no documented history of prior bleeding, absence of metastases, not on anticoagulants at presentation), lack of a comparison group and small number of patients with limited power, the level of evidence for this recommendation is low. The Canadian Stroke Best Practice guidelines and Japanese Stroke Society Guidelines do not mention any specific recommendations surrounding the use of IV thrombolytics in cancer patients. Reference Toyoda, Koga and Iguchi16,Reference Heran, Lindsay and Gubitz17

The major strength of our study is the quality and robustness of our data: all outcome assessments were blinded, and the pragmatic nature of the AcT trial, with broad inclusion criteria and minimal exclusions, likely reflects complication rates seen in real-world clinical practice. This approach enabled the rapid recruitment of over 1600 patients during the COVID-19 pandemic via deferral of consent and minimized potential selection biases, thereby strengthening the generalizability of our findings. Owing to the pragmatic nature of the study, a screening log was not kept for the AcT trial for those who were not treated with IV thrombolysis, which could have provided useful information on reasons for nontreatment in cancer patients and how prevalent an issue this is. Next, our results are in line with those previously published and, despite the small sample size, still show consistency of effect for the safety of thrombolysis in patients with a history of cancer. The biggest limitation of our study is the small number of patients with cancer enrolled, as well as the inability to distinguish active versus history of cancer. However, this practice has been adopted by other stroke trials evaluating cancer patients as a separate subgroup. Reference Navi, Zhang and Miller23,Reference Martinez-Majander, Ntaios and Liu24 While we attempted to distinguish between active and non-active cancer using diagnostic code types, this was inadequately captured in linked administrative data. We also did not have a sufficient sample size to perform subgroup analyses by tumor site in our cohort. Next, the retrospective nature of this analysis predisposes it to potential selection bias based on the original patient population enrolled in AcT – that is, not all consecutive patients with cancer were enrolled, and those with cancer likely reflect a group of patients that are on the mild end of the spectrum for the risk of bleeding. The comparison groups in this analysis were also not randomized, so unmeasured confounders could affect outcomes. Lastly, given the low number of patients with a history of cancer, we did not have sufficient power to detect differences in outcomes between various cancer sites or types of IV thrombolysis treatment.

Conclusion

Patients with a history of cancer and acute ischemic stroke who received thrombolysis had longer lengths of stay, were less likely to achieve functional independence and had higher rates of mortality at 90 days compared to patients without a history of cancer. While they had a numerically higher number of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhages, this difference was not statistically significant. Future studies should evaluate if the response to thrombolysis in cancer patients differs by clinical characteristics, such as cancer site, stage and thrombolytic agent.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2025.10481.

Author contributions

RL and NS conceived and designed the study. MA, BB, LC, AT, TS, RS and BM contributed to the acquisition of data. CD, KI, RL and NS contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. RL and NS drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to revising the article critically for important information and approving the final draft for publication.

Funding statement

None.

Competing interests

The AcT trial was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institute of Health Research. Dr Swartz has stock options in FollowMD and serves on the data safety monitoring board for Hoffman-LaRoche. Dr Lun was invited to speak at the World Stroke Congress on cancer screening after cryptogenic stroke and paid an honorarium.