Introduction

Language learners, both children and adults, can rapidly acquire new words, often without explicit instruction. This ability is particularly impressive given the ambiguity inherent in language learning environments. When encountering a new word, learners must determine its meaning from multiple possible referents, often without direct guidance. A proposed mechanism for solving this challenge is cross-situational word learning (CSWL), where learners track word-referent co-occurrences across different situations to form stable associations (e.g., Escudero et al., Reference Escudero, Smit and Mulak2022; Monaghan et al., Reference Monaghan, Schoetensack and Rebuschat2019; Rebuschat et al., Reference Rebuschat, Monaghan and Schoetensack2021). However, for additional language (L2) learners, word learning is further complicated by challenges beyond referential ambiguity, particularly when unfamiliar phonological contrasts make it difficult to distinguish between words. This difficulty has direct implications for language instruction, as teachers and instructors must consider how best to introduce new phonological contrasts in a way that supports vocabulary learning.

Recent research suggests that non-native phonological contrasts significantly influence CSWL (Escudero et al., Reference Escudero, Smit and Mulak2022; Ge et al., Reference Ge, Monaghan and Rebuschat2025; Tuninetti et al., Reference Tuninetti, Mulak and Escudero2020). For instance, Ge et al. (Reference Ge, Monaghan and Rebuschat2025) found that L2 learners struggle with words that differ only in non-native suprasegmental features (e.g., pa1mi1 vs. pa4mi1, where numbers indicate lexical tones). This raises an important question: can targeted perceptual training on these contrasts enhance word learning? While phonetic training has been shown to improve L2 contrast perception and production (e.g., Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Zhang, Fan and Zhang2019; Iverson & Evans, Reference Iverson and Evans2009; Sakai & Moorman, Reference Sakai and Moorman2017), its impact on word learning remains unclear.

To address this gap, we present two studies examining how different types of perceptual training influence non-native word learning using a CSWL paradigm. Our findings contribute to understanding the interplay between phonetic training and lexical acquisition, which may provide implications for how to design tasks and structure phonetic instructions to promote vocabulary development.

Statistical learning of non-native words

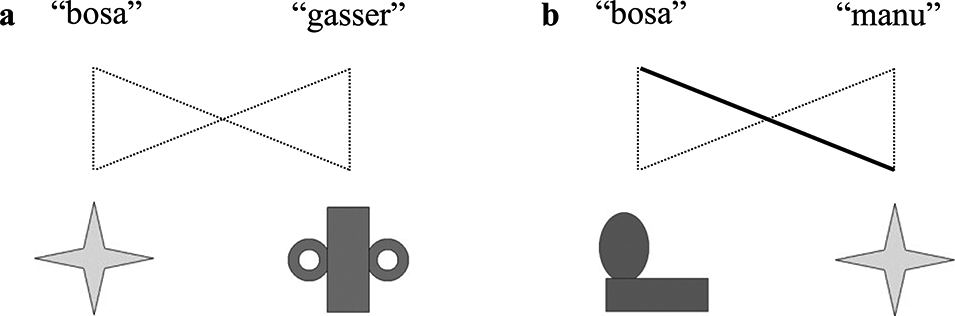

Previous research has shown that learners can extract statistical regularities from the linguistic input to facilitate language learning (see Isbilen & Christiansen, Reference Isbilen and Christiansen2022; Williams & Rebuschat, Reference Williams, Rebuschat, Godfroid and Hopp2023, for reviews). In the area of word learning, a cross-situational statistical learning paradigm has been widely used to examine how learners extract information about word-referent co-occurrences across multiple encounters to find out the correct referents (e.g., Escudero et al., Reference Escudero, Smit and Mulak2022; Rebuschat et al., Reference Rebuschat, Monaghan and Schoetensack2021; Yu & Smith, Reference Yu and Smith2007). For example, in Yu and Smith’s (Reference Yu and Smith2007) seminal study, adult learners were first presented, in each trial, with multiple words and pictures but were not instructed on the individual word-referent mappings (Figure 1a presents an example, dotted lines indicate potential mappings). From each individual trial, it is impossible to infer the word-referent associations; instead, learners need to store information across trials, and when they encounter the same word-referent combination again in another trial (Figure 1b, “bosa” and the star shape), they will start to form the associations. After only six minutes of exposure, learners could match pictures to words at above-chance level even in highly ambiguous conditions where four words and four pictures were presented in each learning trial.

Figure 1. Illustration of CSWL trials based on Yu and Smith’s stimuli.

More recently, the CSWL paradigm has been extended to test L2 learning by including non-native sound contrasts in the words (Escudero et al., Reference Escudero, Smit and Mulak2022; Ge et al., Reference Ge, Monaghan and Rebuschat2025; Tuninetti et al., Reference Tuninetti, Mulak and Escudero2020). For example, Tuninetti et al. (Reference Tuninetti, Mulak and Escudero2020) trained Australian English speakers with novel Dutch and Brazilian Portuguese vowel minimal pairs (e.g., /piχ/-/pyχ/, /fεfe/-/fefe/). The vowel contrasts were classified into perceptually difficult or easy pairs based on acoustic measurements (Escudero, Reference Escudero2005). The perceptually easy minimal pairs contained vowel contrasts that could be mapped to two separate L1 vowel categories, and the perceptually difficult ones had no clear corresponding L1 contrasts (Escudero, Reference Escudero2005: Second Language Linguistic Perception model, L2LP; Best and Tyler, Reference Best, Tyler, Munro and Bohn2007: Perceptual Assimilation-L2 model, PAM-L2). The authors observed a non-native phonology impact: in a word-referent mapping task, learners better identified the minimal pairs that were perceptually easy compared to those that were perceptually difficult.

The non-native phonology effect in CSWL was not only associated with segmental but also suprasegmental features. Ge et al. (Reference Ge, Monaghan and Rebuschat2025) introduced lexical tones to the paradigm and trained English-native speakers with Mandarin pseudowords with tonal differences. In addition to the segmental minimal pairs as in previous research (e.g., Escudero et al., Reference Escudero, Smit and Mulak2022), this study also involved tonal minimal pairs (i.e., two words that differ only in lexical tone: /pa1mi1/ vs. /pa4mi1/ with numbers referring to Mandarin Tone 1 and Tone 4). Through a short cross-situational exposure, the English-native participants successfully identified word-referent mappings in consonantal, vocalic, and non-minimal pair trials, as the segmental features in the stimuli were designed to be familiar to English speakers, but not in the tonal trials. The results add to the previous evidence that non-native phonological features, both segmental and suprasegmental, significantly affect the outcome of L2 word learning.

The previous findings suggested that when learning non-native words, the presence of non-native sound contrasts could pose difficulty. L2 learners could easily learn words that are phonologically distinct from each other (non-minimal pairs, e.g., pa1mi1 vs. li1fa1 in Ge et al. [Reference Ge, Monaghan and Rebuschat2025]) as there are multiple acoustic cues available for distinguishing the words. However, they have problems when the words contrast in only one non-native cue (i.e., tonal minimal pairs for non-tonal speakers). Since the difficulty is closely associated with non-native speech contrasts, but not statistical word learning in general, one possibility is that specific training targeting the speech contrasts could boost learning. The current studies explored this possibility by providing explicit perceptual training to participants before word learning and tested whether perceptual training improved participants’ learning of non-native minimal pair words.

Perceptual training of non-native sounds

Perceptual training research has contributed to the understanding of three processes involved in non-native speech learning: perceptual plasticity, modality transfer, and robustness of learning. It has shown that (i) speech perception remains malleable in adulthood with re-attunement of already established phonemic categories and formation of new non-native categories (e.g., Bohn, Reference Bohn, Fernandez and Cairns2018; Sereno & Wang, Reference Sereno, Wang, Munro and Bohn2007), (ii) perceptual training leads to moderate effects on perception and small improvements in production (e.g., Sakai & Moorman, Reference Sakai and Moorman2017; Uchihara et al., Reference Uchihara, Karas and Thomson2024), and (iii) learning resulting from training tends to generalize to new conditions such as novel tokens, phonetic contexts, talkers, and tasks, and be retained over time, thus leading to robust speech learning (e.g., Rato & Oliveira, Reference Rato, Oliveira, Alves and Albuquerque2022).

Of particular interest for the scope of the present studies is the research that examines the robustness of non-native speech learning, specifically perceptual training studies that investigate whether gains obtained via a training program generalize to new conditions. In a systematic review of 27 perceptual training studies, Rato and Oliveira (Reference Rato, Oliveira, Alves and Albuquerque2022) report that the studies (93%) that tested generalization of learning to untrained conditions found evidence of transfer of improvement to novel voices, stimuli, tasks, and phonetic contexts, with only 68% reporting that effect for all conditions tested. For example, Godfroid, Lin, and Ryu (Reference Godfroid, Lin and Ryu2017) reported transfer of perceptual learning to untrained tasks, stimuli and talkers; Strange and Dittmann (Reference Strange and Dittmann1984) observed that improvement in AX discrimination tasks generalized to identification tasks; Shport (Reference Shport2016) found evidence of generalization to novel stimuli but not to new voices; and Lee and Lyster (Reference Lee and Lyster2016) observed the inverse trend, i.e., transfer to novel talkers but not to untrained stimuli. However, there are also contradicting results where limited generalizability to new phonetic environments was observed (e.g., Iverson et al., Reference Iverson, Hazan and Bannister2005; Barriuso & Hayes-Harb, Reference Barriuso and Hayes-Harb2018 for discussion). Given these findings, we predict that perceptual training in the target non-native sounds may lead to generalization of learning to non-native minimal pairs in a CSWL paradigm, but we also acknowledge that the degree of generalization may be relatively small, as our target participants are naïve learners of the sounds.

Findings further suggest that the learning of non-native speech sounds is moderated by the nature of the perceptual training paradigm (Sakai & Moorman, Reference Sakai and Moorman2017). Two meta-analyses reveal that speech performance outcomes show a generally larger effect for training providing feedback, and for training that includes explicit phonetic instruction (Lee, Jang, & Plonsky, Reference Lee, Jang and Plonsky2015; Sakai & Moorman, Reference Sakai and Moorman2017, respectively). The preliminary results of a recent meta-analysis examining the effectiveness of different types of pronunciation instruction show that both explicit and implicit instruction are effective for the acquisition of non-native segments, but explicit instruction tends to be more effective in the learning of similar sounds (De Clercq et al., Reference De Clercq, Valada, Tran, Correia and Housen2023), as is the case of the four segmental target contrasts in the language pair L1 English-L2 Portuguese. Importantly, results with native English speakers without previous exposure to Portuguese learning pseudowords with the same non-native contrasts in an oddity discrimination training task without feedback showed no improvements from pre-test to post-test (Correia et al., Reference Correia, Rato, Ge, Fernandes, Kachlicka, Saito and Rebuschat2025). Therefore, in the present study, we employed two discrimination training tasks with feedback (AX and oddity), as they provide perceptual guidance for naïve learners who have not yet established phonological categories for the target contrasts. Unlike identification training, which requires learners to assign labels or categories to sounds—a process that presupposes some phonological knowledge—discrimination training is more accessible for naïve listeners because it focuses on detecting phonetic differences without requiring explicit categorization. Furthermore, the two discrimination tasks used in this study differ in their complexity and cognitive demands. AX discrimination focuses on auditory processing (i.e., detecting the differences between sounds), whereas oddity discrimination additionally allows learners to build more robust representations and categorizations (Strange & Shafer, Reference Strange, Shafer, Edwards and Zampini2008). By employing both training methods, we aimed to investigate how task type influences phonetic learning and whether improvements in phonetic perception transfer to word learning in a CSWL paradigm.

The perceptual-lexical link

The link between perceptual and lexical abilities has been reported in L2 studies across a range of target languages (e.g., Silbert et al., Reference Silbert, Smith, Jackson, Campbell, Hughes and Tare2015 for contrasts from nine languages; Wong & Perrachione, Reference Wong and Perrachione2007 for Mandarin). For instance, one early study that directly investigated the “phonetic-phonological-lexical continuity” was Wong and Perrachione’s (Reference Wong and Perrachione2007) work on L2 tonal word learning. English-native participants who had no tonal experience learned pseudowords that contained Mandarin tonal features, and additionally were examined on the ability to identify pitch patterns before training. A correlation was observed between pitch pattern identification and word learning performance, indicating that better perceptual ability was associated with better word learning. This raises a critical question: can targeted perceptual training enhance learners’ word acquisition? Only a few studies have explicitly investigated this question, with mixed findings reported. For example, Ingvalson et al. (Reference Ingvalson, Barr and Wong2013) found that a combination of phonetic and lexical training improved tonal word learning more than merely lexical training, especially for low-aptitude English-native speakers; Melnik and Peperkamp (Reference Melnik and Peperkamp2021) observed that High-Variability Phonetic Training (HVPT) improved not only prelexical identification but also lexical processing among French learners of English. However, Barriuso (Reference Barriuso2018) showed no such transfer of phonetic training to word learning tasks. Overall, there is limited research that directly examines the role of perceptual training on the higher lexical level, and the current study aims to address this gap.

Research questions and predictions

RQ1: Do phonological overlaps and non-native phonological contrasts pose difficulty during cross-situational word learning?

RQ2: Do different types of perception training tasks facilitate non-native word learning?

In Study 1, we addressed the first question. We predicted that phonologically overlapping words (i.e., minimal pairs) would be more difficult to learn than non-minimal pairs, and minimal pairs with non-native phonological contrasts would generate great difficulty in learning (RQ1). To compare the performance on native vs. non-native contrasts, we created Portuguese pseudowords and recruited Portuguese-native and English-native speakers. The Portuguese-native participants were predicted to perform better than English-native participants in learning the minimal pair words with Portuguese-specific contrasts. In Study 2, we employed two perception training tasks, and predicted that participants who received discrimination training before the CSWL task would outperform those without training (RQ2).

Study 1: Methods

Participants

Twenty native speakers of English and twenty Portuguese speakers volunteered to participate in this study. The sample size was estimated by means of Monte Carlo simulations of data.Footnote 1 Participants were recruited through email advertisements within university communities in Lancaster and Lisbon. Participants had to be at least 18 years old, native speakers of English or Portuguese, and have normal or corrected-to-normal vision and hearing. An additional prerequisite was that the English native speakers should have no previous experience learning European Portuguese, nor should they have resided in a Portuguese-speaking country for more than four weeks. Participants were not remunerated in this study.

Our sample consisted of 23 women, 14 men, and 2 non-binary persons (1 not reported). The mean age was 26.3 (SD = 9.2, range 18–56 years). All participants grew up monolingually in childhood, except for two in the English-speaking group who reported being English-Polish and English-Vietnamese bilinguals. Thirty-two participants reported having learned additional languages. In the English-native group, the average number of additional languages was 1.5 (in order of decreasing frequency, French, Spanish, German, Mandarin, Japanese, Urdu, and Welsh).Footnote 2 In the Portuguese-native group, the average number of additional languages was 2.6 (English, French, German, Italian, Spanish, and Romanian). There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of gender, age, or language background.

The preregistration for this study can be found on the OSF website, https://osf.io/ne7vd?.

Experimental tasks and materials

Cross-situational word learning task

In the cross-situational word learning (CSWL) task, participants were told that they would hear one word and see two objects on the screen. Their task was to decide, as quickly and accurately as possible, which object the word referred to. We used this version of the CSWL paradigm (Ge et al., Reference Ge, Monaghan and Rebuschat2025) because it more closely mirrors natural language learning, requiring learners to track minimal pairs across multiple exposures rather than within a single trial. Traditional CSWL paradigms (e.g., Yu & Smith, Reference Yu and Smith2007) often present multiple words and referents together, making phonological contrasts more salient due to immediate proximity (Escudero et al., 2016b, 2022; Tuninetti et al., Reference Tuninetti, Mulak and Escudero2020). However, in natural learning settings, minimal pairs are typically encountered in varied contexts, requiring learners to extract phonological contrasts over time. Additionally, this design allows for continuous tracking of learning trajectories, enabling us to examine how accuracy evolves throughout the task.

Participants were instructed to press “Q” on the keyboard if they thought the object on the left was the correct referent of the word and “P” for the object on the right. Since the task is very simple, no practice trials were used. At the beginning of the task, participants were expected to guess the correct referent, and over multiple encounters, they would start to form associations between pseudowords and referents.

In each trial, participants first saw a fixation cross at the center of the screen for 500 ms. They were then shown two objects on the screen (one on the left side and one on the right) and were played a single pseudoword (~500 ms). After the pseudoword was played, participants were prompted to enter their response on the keyboard (Q or P). The objects remained on the screen during the entire trial, but the pseudoword was only played once. The next trial only started after participants made a choice for the current one. No feedback was provided after each response. We recorded the keyboard responses in each trial to calculate accuracy and response times. Figure 2 provides an example of a CSWL trial.

Figure 2. Example of cross-situational word learning (CSWL) trial.

There were three types of trials. In non-minimal pair (non-MP) trials, the two objects presented on the screen referred to pseudowords that were phonologically distinct (e.g., /dopu/ and /kiɲu/). In consonantal minimal pair (cMP) trials, the two objects on the screen referred to pseudowords that differed in only one consonant contrast (e.g., /tilu/ and /tiʎu/). Finally, in vocalic minimal pair (vMP) trials, the two objects referred to pseudowords that differed in only one vowel contrast (e.g., /pemu/ and /pɛmu/). This manipulation allowed us to determine if and how phonological overlap between the pseudowords affected word learning.

Each participant completed 12 cross-situational learning blocks, with each pseudoword-object mapping occurring once per block. There were thus 24 trials per block, and 288 trials in total. The three trial types (non-MP, cMP, vMP) occurred eight times per block. The order of trials within each block was randomized for each participant, as was the sequence in which the 12 blocks occurred.

Pseudowords and visual referents

To create the pseudowords for the CSWL task, 10 consonants (/d, k, l, ʎ, m, n, ɲ, p, s, t/) and 7 vowels (/a, e, ɛ, i, u, o, ɔ/) from the Portuguese phonemic inventory were combined to create 24 pseudowords.Footnote 3 Each pseudoword was disyllabic with CVCV structure and followed the phonotactics of Portuguese. The linguistic focus in our study was on four sound contrasts that are phonemic in Portuguese but not in English, the native language of our participants. Two of these were consonant contrasts, /l/ and /ʎ/ (e.g., Portuguese mala, “suitcase,” and malha, “mesh”) and /n/ and /ɲ/ (mana, “sister” informal, and manha, “ruse”). The other two were vowel contrasts, /e/ and /ɛ/ (sede, “thirst,” and sede, “head office”) and /o/ and /ɔ/ (olho, “eye,” and olho, “I look”).

To investigate the impact of non-native phonology on novel word learning, our 24 pseudowords formed 12 minimal pairs. As can be seen in Table 1, we manipulated the onset of the second syllable to create consonant minimal pairs (e.g., /palu/ and /paʎu/) and the rhyme of the first syllable to create vowel minimal pairs (e.g., /dopu/ and /dɔpu/). The pseudowords have no corresponding meaning in English or Portuguese. The audio stimuli were recorded by a female native speaker of Portuguese, and the mean length of the audio stimuli was 500 ms. We did not use any written representation of the pseudowords.

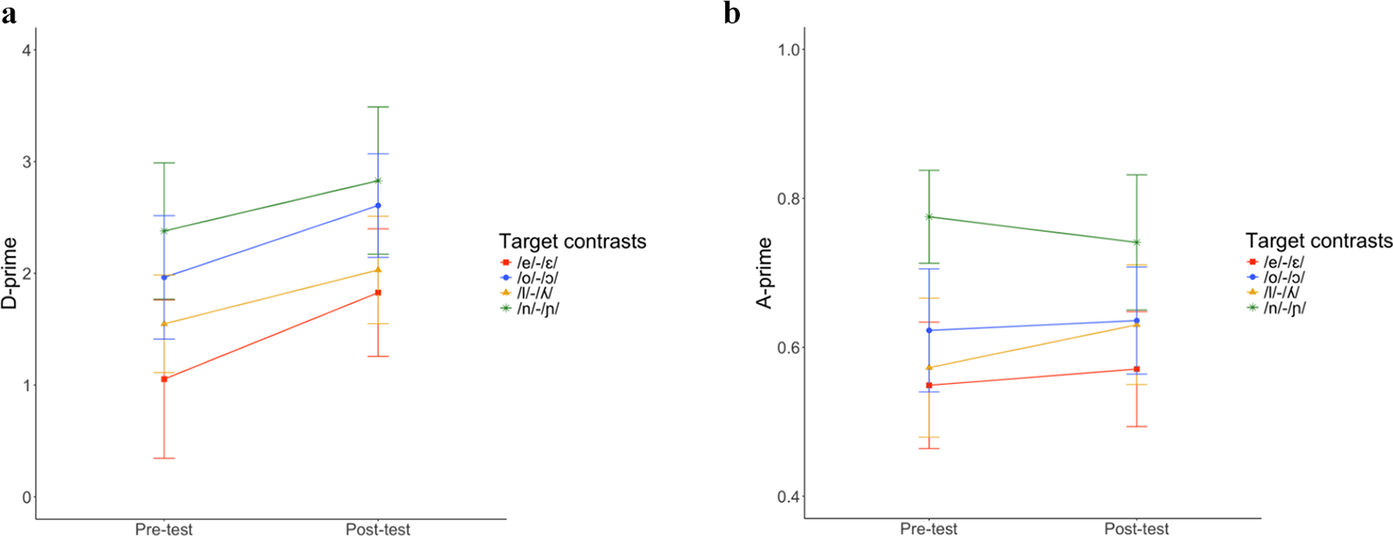

Table 1. The phonological contrasts and pseudowords used in this study

We chose 24 novel and unusual objects from Horst and Hout’s (Reference Horst and Hout2016) NOUN database as referents for our pseudowords. The pseudowords were randomly mapped to the objects, and we created four lists of word-referent mappings to minimize the influence of a particular mapping being more memorizable than other mappings. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of the mappings. All materials are openly available at: https://osf.io/qjrm8?.

Debriefing questionnaire

We adapted the debriefing questionnaire from Monaghan et al. (Reference Monaghan, Schoetensack and Rebuschat2019) to gather information about the strategies that participants might have used during the task and to determine whether participants became aware of the non-native target segments (/ʎ/, /ɲ/, /e/, /ɔ/), as awareness of the target might influence learning outcomes. In terms of strategy use, we asked participants to report how they decided which object was the correct referent, if they followed any strategies, and if they changed the way they made decisions on the objects throughout the experiment. In terms of awareness, we first asked them if they had noticed any patterns or rules in general. We then asked if they noticed any patterns or rules about the sound system of the new language in terms of pronunciation. Finally, we asked specifically if they noticed that the language used vowels and/or consonants to mark different word meanings. The questionnaire can be found in our OSF repository. Participants completed this questionnaire in their respective native languages, English or Portuguese.

Background questionnaire

We adapted Marian et al.’s (Reference Marian, Blumenfeld and Kaushanskaya2007) LEAP-Q to gather information about participants’ gender, age, and language backgrounds. Participants were asked to specify their native languages and all non-native languages they have learned, including the age of learning onset, contexts of learning, lengths of learning, and self-estimated general proficiency levels. Again, there were two versions of this questionnaire, one in English and one in Portuguese.

Procedure

We used the online research platform Gorilla (Anwyl-Irvine et al., Reference Anwyl-Irvine, Massonnié, Flitton, Kirkham and Evershed2020) to collect data. Participants were instructed to run the experiment using only headphones or earbuds and NOT audio coming from speakers. They were explicitly instructed to find a quiet and silent place where they would not be disturbed, and to turn off all notifications and instant messaging (WhatsApp, Skype, Discord, etc.) and close all other windows on their browser.

After successfully completing a sound check and providing informed consent, participants completed the background questionnaire, followed by the CSWL task. The tasks were administered in either English or Portuguese, depending on the language group. For the Portuguese native-speaking group, the experiment concluded with the completion of the debriefing questionnaire. In the case of the English native speakers, we also asked them to complete two phonological short-term memory measures (nonword repetition and digit span). These tests were included for exploratory purposes and are not reported below. The entire experiment took approximately 40 minutes to complete.

Data analysis

We excluded one participant who failed to successfully complete the initial sound check. We also excluded individual responses that lasted over 30 seconds (4 out of 11,520 trials). This was because these participants failed to follow the instruction to respond as quickly and accurately as possible. After excluding these data points, we visualized the data using R for general descriptive patterns. We then used generalized linear mixed effects modelling for statistical data analysis. Mixed effects models were constructed from a null model (containing only random effects of item and participant) to models containing fixed effects. We tested whether each of the fixed effects improved model fit using log-likelihood comparisons between models. A quadratic effect of block was also tested for its contribution to model fit, as block may exert a quadratic rather than linear effect.

Study 1: Results

Performance on CSWL task

Figure 3 illustrates the performance of the two groups across the twelve blocks of the CSWL task. Both groups scored significantly above chance from the fourth block, i.e., there were clear learning effects in both groups. However, as Figures 4a (L1 English) and 4b (L1 Portuguese) suggest, performance was affected by trial type. Both groups showed robust learning effects when responding to non-minimal pair trials, i.e., in trials in which the pseudowords associated with the two objects were phonologically distant (e.g., /kiɲu/ and /pemu/). But when they were presented with minimal pair trials (vocalic or consonantal), their accuracy decreased substantially. For the L1 Portuguese group, the accuracies in the minimal pair trials exhibited small, gradual increases throughout the cross-situational learning task, but the performance of the L1 English group was at chance level throughout the task.

Figure 3. Mean proportion of correct pictures selected in each block of the CSWL task.

Note: The dotted line represents the chance level. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 4. Mean proportion of correct pictures selected in different trial types, for L1 English (a) and L1 Portuguese (b) groups.

Planned analyses

As outlined in our preregistration, to investigate whether learning was different across language groups and trial types, we ran generalized linear mixed effects models to examine performance accuracy across blocks. We started with a model with the maximal random effects that converged, which included item slope for block, language group, and trial type, and participant slope for learning block, trial type, and the interaction between block and trial type. Then we added fixed effects of block, language group, trial type, and the three-way interaction to test if they improve model fit. We also tested for a quadratic effect for block.

Compared to the empty model, adding the fixed effect of block improved model fit significantly (χ2(1) = 6.034, p = .014), adding trial type (consonant, vowel, non-minimal pair) improved model fit further (χ2(2) = 45.706, p < .001) as well as the three-way interaction (χ2(5) = 36.827, p <.001). This indicates that participants improved significantly over the blocks, and the learning trajectories for different types of trials were different. Adding English vs. Portuguese language group did not significantly improve fit (χ2(1) = 2.532, p = .112). The quadratic effect for block did not result in a significant difference (χ2(36) = 31.634, p = .676). The summary of the best-fitting model can be found in supplementary materials Table S1.Footnote 4

Exploratory analyses. To disentangle the three-way interaction, we further analyzed the effect of language group and block in each trial type condition, respectively. For non-minimal pair trials, adding the effect of block improved model fit (χ2(1) = 31.712, p < .001), but not L1 English vs L1 Portuguese group (χ2(1) = 0, p = 1) nor the block*trial type interaction (χ2(2) = 0.4068, p = .816). For consonantal and vocalic trials, language group (consonantal χ2(1) = 0.5724, p = .449; vocalic χ2(1) = 0.1603, p = .689) and block did not improve fit (consonantal: χ2(1) = 0.5023, p = .479; vocalic: χ2(1) = 1.0474, p = .306). Adding the language group by block interaction led to a marginally significant improvement in model fit for vocalic trials (χ2(3) = 7.7346, p = .052) but not for consonantal trials (χ2(3) = 6.1921, p = .103).Footnote 5

Additionally, we explored whether the two language groups differed in learning outcomes of the critical consonantal and vocalic trials at the end of the CSWL task. For consonantal trials, adding the effect of L1 English vs L2 Portuguese group had a marginally significant influence on model fit (χ2(1) = 3.068, p = .080). For vocalic trials, the group effect was significant (χ2(1) = 4.5471, p = .033). That is, the L1 Portuguese group performed significantly better than the English group in consonantal and vocalic trials at the end of the CSWL task.

Retrospective verbal reports

We analyzed participants’ responses in the debriefing questionnaire to determine if they became aware of the non-native target segments (/ʎ, ɲ, e, o/) and, if so, if awareness was linked to improved performance during the CSWL task. The awareness coding followed Rebuschat et al. (Reference Rebuschat, Hamrick, Riestenberg, Sachs and Ziegler2015) and Monaghan et al. (Reference Monaghan, Schoetensack and Rebuschat2019) (see also Ge et al., Reference Ge, Monaghan and Rebuschat2025), and the transcripts can be found in our OSF repository. We focused on the retrospective verbal reports of the English-native speakers, as the Portuguese-native speakers were expected to be familiar with the segmental contrasts of their native language. In coding the reports, we classified as “aware” any participant who mentioned noticing the non-native segments (/ʎ, ɲ, e, o/) or the existence of minimal pairs in which a native and a non-native sound contrast. Participants who failed to report this were classified as being “unaware.” Two researchers completed the coding to ensure consistency and agreement on criteria.

The 2 coders agreed to classify 5 participants (out of 20, i.e., 25%) as being potentially “aware.” One participant reported that “some different vowel sounds and vowels seemed to be longer on average,” suggesting perhaps that they believed the differences between /e/-/ɛ/ and /o/-/ɔ/ to be one of vowel length. Another participant appeared to have noticed the /ɲ/ sound in the pseudoword. In both cases, this could reflect attention to the learning targets. In addition, there were three participants who might have become aware of the minimal pairs. For example, when prompted to reflect about the existence of minimal pairs, one participant appeared to be aware that “the words that were very similar seemed to only have like one or two different letters in them.” Another participant suggested that the words “seemed to change on very small details like one different letter.” Again, this could suggest that they noticed the subtle phonetic changes in our pseudowords. Given that only five participants reported some basic awareness of the learning targets, we did not reanalyze our data based on aware and unaware subgroups (see Monaghan et al., Reference Monaghan, Schoetensack and Rebuschat2019, for an illustration).

Study 1: Discussion

Study 1 provided further evidence that adults can learn non-native words through cross-situational statistics (Escudero et al., Reference Escudero, Smit and Mulak2022; Ge et al., Reference Ge, Monaghan and Rebuschat2025; Tuninetti et al., Reference Tuninetti, Mulak and Escudero2020), even when the minimal pairs were not immediately available within a single learning trial. The results also indicated that the existence of minimal pairs and non-native sounds can influence learning outcomes. As predicted, participants better identified referents in non-minimal pair trials where the two pictures were mapped to phonologically distinct words than in the minimal pair trials. In addition, learners’ familiarity with the phonological contrasts influenced learning, as the Portuguese-native participants outperformed the English-native participants at the end of the CSWL task in consonantal and vocalic minimal pair trials. It is worth noting that this difference between language groups was only found at the end of the learning, but the two groups’ learning trajectories across blocks did not significantly differ in general. This differs from previous findings where the L1 participants showed greater advantages in learning native minimal pairs than the L2 participants (e.g., Ge et al., Reference Ge, Monaghan and Rebuschat2025). This indicates that the chosen minimal pair contrasts are relatively difficult even for Portuguese-native speakers, and hence, the L2 learners are likely to require more specific and explicit training on these target sounds to aid learning.

Regarding English-native participants’ awareness of the phonological properties of the words, only a small proportion of participants developed some explicit knowledge of the novel phonology system and the existence of similar-sounding words (minimal pairs). This aligns with their chance-level performance in the minimal pair trials.

These findings closely connect with classroom-based language instruction. The challenges associated with minimal pairs could lead to increased lexical confusion in real-world communication, highlighting the importance of integrating targeted phonological instructions into vocabulary learning. Our results suggest that incidental exposure to phonological contrasts may be insufficient for successful learning of phonologically overlapping words, especially for beginner L2 learners with limited familiarity with the target language’s phonology. Given that only a small proportion of English-native participants developed explicit awareness of the phonological properties of the novel words, it appears that implicit learning under the current conditions may not be sufficient for acquiring such contrasts. However, this does not preclude the possibility of implicit learning altogether. Greater exposure over a longer period might be necessary for these contrasts to be acquired. Additionally, adult learners, whose phonological systems are already established, may require more time and/or different types of input for successful learning. Future research should explore the role of specific interventions in supporting minimal pair learning. For example, providing learners with immediate feedback on their phonological distinctions (e.g., Thomson & Derwing, Reference Thomson, Derwing, Levis, Le, Lucic, Simpson and Vo2016) or explicit phonetic instructions (e.g., Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Darcy, Ewert, Levis and LeVelle2013) may enhance awareness and facilitate more precise encoding of novel contrasts. Increased exposure to minimal pairs through high-variability input conditions, such as exposure to different talkers, may also aid learning (e.g., Uchihara et al., Reference Uchihara, Karas and Thomson2024).

Study 2: Methods

Participants

Sixty-eight native speakers of EnglishFootnote 6 (34 women, 34 men, average age 32.4 (SD = 7.4), 18–45 years) were randomly assigned to one of the three training groups. One group was trained via an oddity discrimination task (Oddity condition, n = 24) before the CSWL task. A second group was trained via an AX discrimination task (AX condition, n = 22). The third group received no phonetic training (untrained condition, n = 22).

Nineteen participants reported having learned an additional language. The average number of additional languages was 0.3 (in order of decreasing frequency, Spanish, French, German, Japanese, Welsh, Bengali, Indonesian).Footnote 7

Participants were recruited via the Prolific platform, https://www.prolific.com/. They had to be at least 18 years old, speak English as a native language, and have no prior experience learning Portuguese or have resided in a Portuguese-speaking country for more than four weeks. Participants were paid 9 GBP per hour. The preregistration for this study can be accessed at: https://osf.io/vafu3?.

Experimental tasks and materials

The CSWL task, the debriefing, and background questionnaires were identical to those used in Study 1, but we created two perceptual discrimination tasks.

AX discrimination task

In this task, participants were played two pseudowords and asked to decide if the items were the same or different by clicking the options “SAME” or “DIFFERENT” on the screen. The inter-stimulus interval between the two pseudowords was 750 ms, and the inter-trial interval was 1,000 ms. In the first and sixth blocks of the task, participants did not receive feedback on the accuracy of their response, and the next trial started once the response had been entered. These blocks thus served as pre-test and post-test, respectively. In the second to the fifth blocks of the task, participants did receive feedback on response accuracy. If the response was correct, participants saw a green tick. If the response was incorrect, they saw a red cross and were then played the same pseudowords and had to respond again. The next trial was only played once a correct response was entered. These blocks (2–5) served to train our participants on the non-native sounds. There were 48 trials per block, and the trial and block sequences were randomized for each participant. Participants received detailed instructions and six practice trials every time a change in task is introduced or a new session/day starts—prior to the first (pre-test) and the second block (training block) on Day 1, and the fifth (training block) and the sixth block (post-test) on Day 2.

Oddity discrimination task

Participants were played three pseudowords sequentially and asked to indicate which, if any, of the words was different from the others. The inter-stimulus interval was 750 ms, and the inter-trial interval was 1,000 ms. Participants had to respond by clicking on one of the four options “1,” “2,” “3,” or “SAME.” The latter response indicated that participants did not detect a difference. Again, in the first and sixth blocks of the task, participants were not provided with feedback, and so these blocks served as pre-test and post-test, respectively. In the second to the fifth blocks, feedback was provided in the same manner as in the AX discrimination task. There were also 48 trials per block, and the trial and block sequences were randomized for each participant. Participants received detailed instructions and six practice trials every time a change in task is introduced or a new session/day starts—prior to the first (pre-test) and the second block (training block) on Day 1, and the fifth (training block) and the sixth block (post-test) on Day 2.

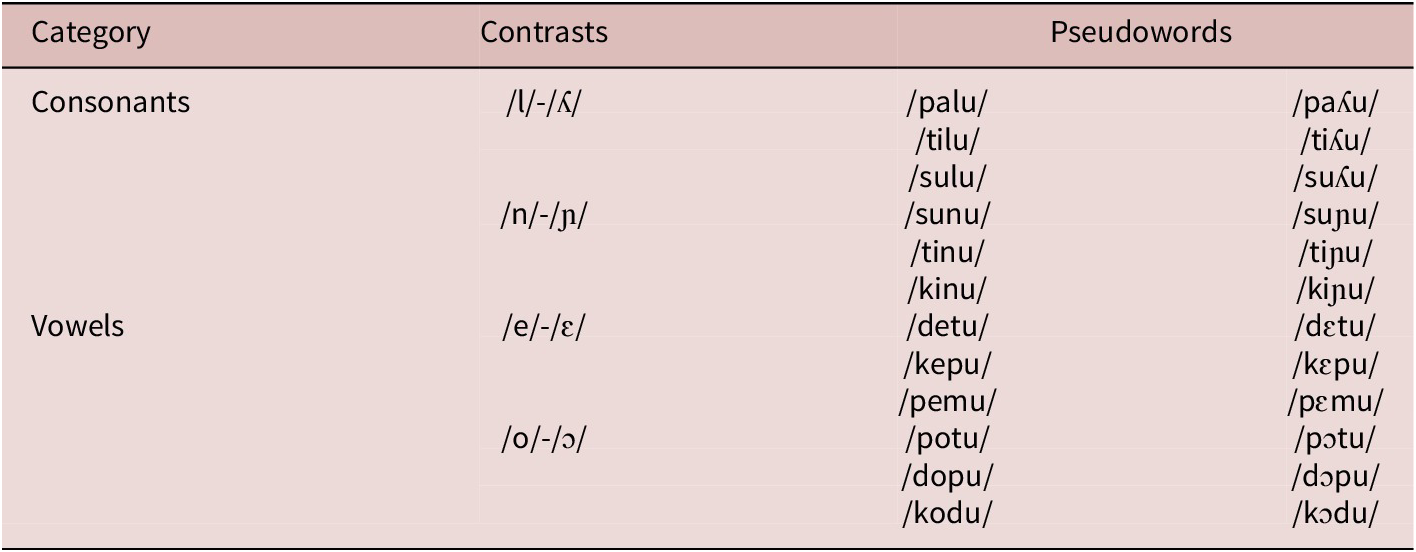

Pseudowords in the discrimination tasks

For the perceptual discrimination tasks (AX and oddity), we used 24 disyllabic (pseudo)words (Table 2) that were developed for a separate project on L2 speech learning (Correia et al., Reference Correia, Rato, Ge, Fernandes, Kachlicka, Saito and Rebuschat2025). The items followed the phonotactics of Portuguese, and each target contrast, i.e., /e/-/ɛ/, /o/-/ɔ/, /l/-/ʎ/, and /n/-/ɲ/, occurred three times. Each pseudoword was produced by three native speakers of Portuguese, two female and one male speakers. The occurrence of each speaker’s voice was counterbalanced across trials.

Table 2. The pseudowords used in the AX task and the oddity discrimination task

Procedure

Participants were instructed to complete the experimental tasks over two consecutive days, using headphones or earbuds in a quiet place. On Day 1, participants provided informed consent and completed a sound check and the background questionnaire. Participants in the AX and oddity conditions then completed the first four blocks of their respective perceptual discrimination tasks, with the first block as a pre-test. Participants in the untrained condition did not complete perceptual discrimination and moved straight to the CSWL task, followed by the debriefing questionnaire.

On Day 2, participants were first given the same instruction on the testing environment again, reinforcing the requirement to complete the experiment in a quiet place with headphones or earbuds, while turning off all notifications. Participants in the AX and oddity conditions first completed another sound check, then received one more block of their respective perceptual discrimination task with feedback, followed by a final block without feedback, which served as post-test. They then completed the same CSWL task, followed by the debriefing questionnaire. On Day 2, participants in the untrained condition completed a series of unrelated tasks, which are not reported below. For this condition, all relevant data were collected on the first day.

For the oddity condition, the experiment took approximately two hours to complete (one hour per day); for the AX condition, it took around one hour to complete (half an hour per day); and for the control group, the tasks took around 25 minutes (on Day 1).

Data analysis

The analyses of the CSWL results were the same as in Study 1. We excluded two participants who failed the initial sound check and excluded 10 (out of 19,584) individual responses that lasted over 30 seconds. Additionally, we ran mixed-effect models to compare participants’ perceptual performance in pre- vs. post-tests.

Study 2: Results

Performance in the perceptual discrimination tests

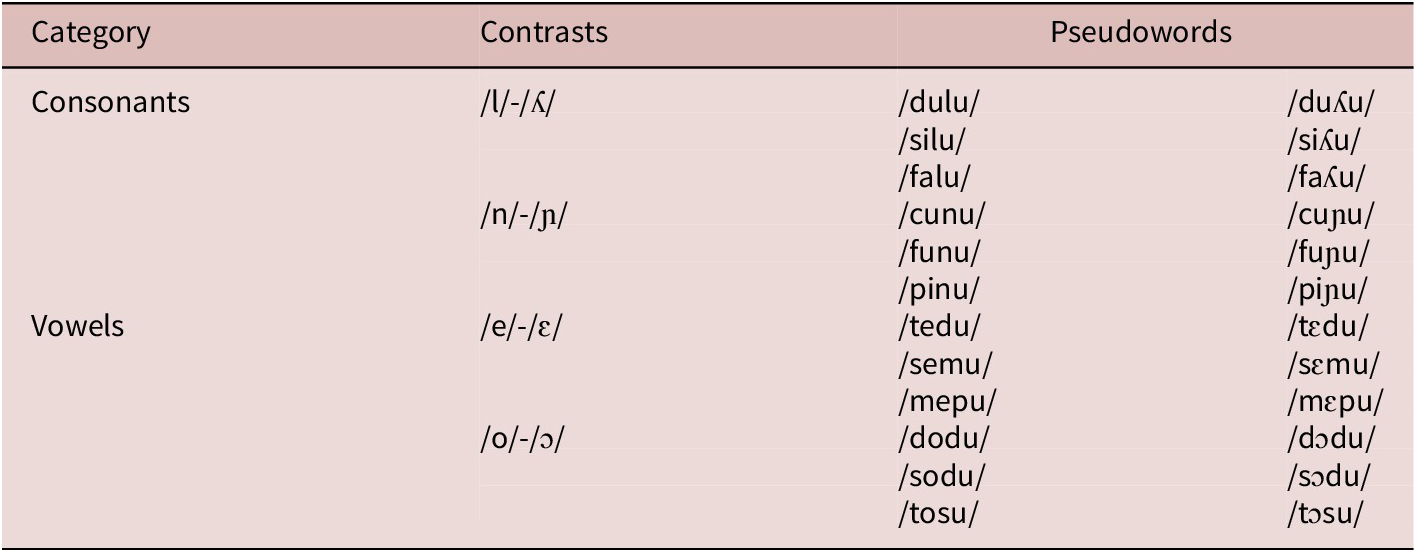

Figures 5a and 5b visualize the performance of the AX and the oddity groups on the perceptual discrimination pre-tests and post-tests, i.e., on the first and the final block of the AX or oddity discrimination tasks, which were administered without feedback on response accuracy.

Figure 5. Performance on the perceptual discrimination pre- and post-tests for the AX (a) and oddity (b) group.

Note: Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

We transformed raw percentage accuracy to D-prime (for AX same-different task) and A-prime (for oddity judgement task) measures, respectively, to account for potential response biases in discrimination judgments. The D-prime scores could reach a highest effective limit of 4.65, indicating near ceiling sensitivity, whereas 0 indicates chance level. The A-prime scores can range from −1 to 1, with 0 indicating chance-level discrimination and 1 indicating perfect discrimination. The AX group showed improvement on all four target contrasts after training, whereas the oddity group did not exhibit clear improvement in the contrasts.

For each of the trained groups, we used linear mixed-effects models to explore the effects of perceptual discrimination training, target contrasts, and the interaction between training and target contrasts on perception accuracy. For the AX group, the effect of test (pre-test vs. post-test) significantly improved model fit (χ2(1) = 8.2301, p = .004), as well as the effect of target contrast (χ2(3) = 20.96, p < .001). The interaction effect did not further improve fit (χ2(4) = 0.4761, p = .924). This suggests an overall improvement in the perception of all contrasts from pre-test to post-test. For the oddity group, only the effect of target contrast led to a significant improvement in model fit (χ2(3) = 27.219, p < .001), but not the training effect (χ2(1) = 0.2426, p = .622) nor the interaction effect (χ2(3) = 1.7428, p = .783), indicating that the oddity group did not show significant improvement from pre- to post-test.

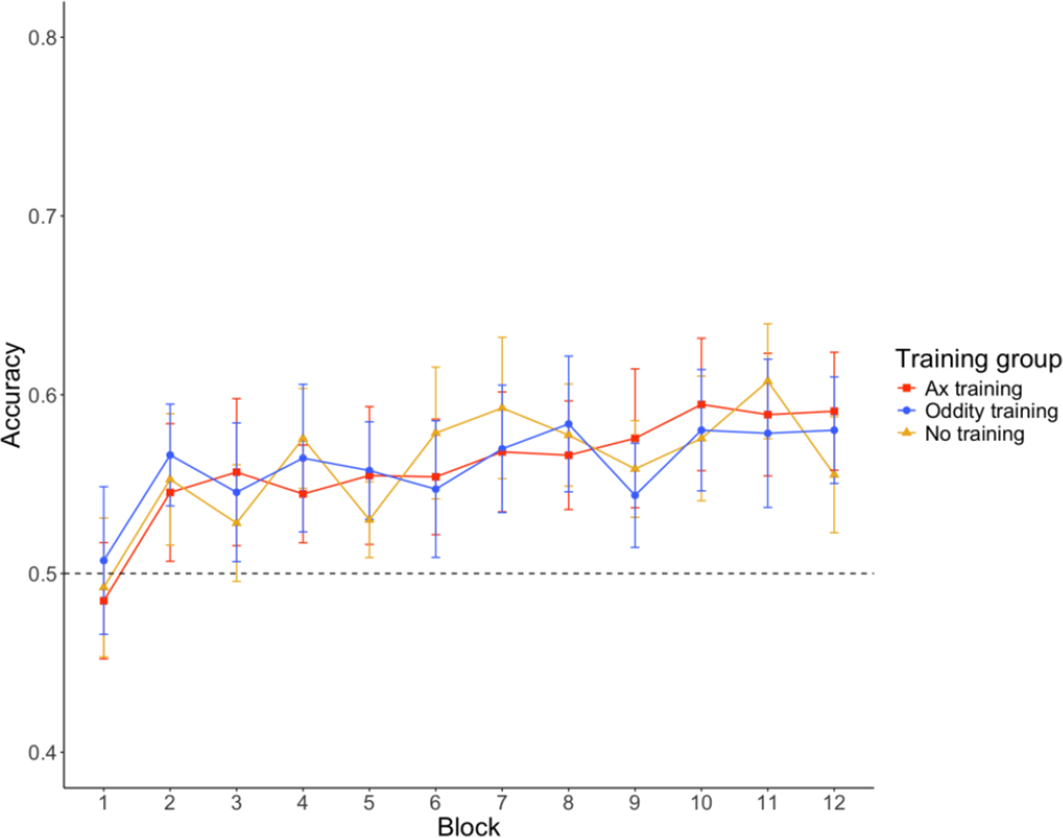

Performance on the CSWL task

Figure 6 illustrates the performance of the 3 groups across the 12 blocks of the CSWL task. As in Study 1, all groups showed clear learning effects, performing consistently above chance after the fourth exposure block. The untrained group replicated the results of the English-speaking group in Study 1. However, the learning trajectories of the three groups were surprisingly similar. Again, all groups performed best (above chance) in non-minimal pair trials, and around chance-level in consonantal and vocalic minimal-pair trials. Figures 7a, 7b, and 7c summarize the groups’ performances across the different trial types.

Figure 6. Mean proportion of correct pictures selected in each block of the CSWL task.

Note: The dotted line represents the chance level. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 7. Mean proportion of correct pictures selected in different trial types for the AX (a), oddity (b), and untrained group (c).

To be comparable to Study 1, we ran similar mixed effects models to examine the effect of exposure block, trial types, and groups. The fixed effect of exposure block (χ2(1) = 1.0791, p = .299) and group (χ2(2) = 0, p = 1) did not significantly improve model fit. But adding trial type (χ2(2) = 52.373, p < .001) and the three-way interaction (χ2(8) = 45.019, p < .001) led to significant improvement. The quadratic effect for block did result in a significant difference (χ2(38) = 64.332, p = .005). Thus, the three groups did not differ significantly in performance, but the learning trajectories of different trial types differed for all groups. The best-fitting model can be found in supplement materials Table S2. The similar learning trajectories across groups suggest that the training design may not have been optimal in differentiating word learning outcomes. Future work should explore whether modifications in training task or intensity could improve its effectiveness.

Exploratory analyses

To look closer into the interaction effect, we ran analyses for each trial type. For the consonantal and vocalic minimal pair trials, we found no effect of group (consonantal χ2(2) = 1.6907, p = .429; vocalic χ2(2) = 0.918, p = .632), exposure block (consonantal χ2(1) = 2.3698, p = .124; vocalic χ2(1) = 0.0053, p = .942) nor block*group interaction (consonantal χ2(5) = 7.7955, p = .168; vocalic χ2(5) = 3.3514, p = .646). For the non-minimal pair trials, adding the effect of block improved model fit (χ2(1) = 24.76, p < .001), but not the effect of group (χ2(2) = 1.953, p = .377) nor the interaction (χ2(4) = 0, p = 1). Also, the final learning outcome (i.e., performance in the final exposure block) did not differ significantly across groups (group effect in consonantal trials: χ2(2) = 2.2567, p = .324; vocalic trials: χ2(2) = 0.2355, p = .889). These results suggest that participants’ performance improved over time only in the non-minimal pair trials across all groups.

Retrospective verbal reports

We used the same procedure as in Study 1 to distinguish “aware” and “unaware” participants in the two trained groups. Participants in the untrained group did not provide verbal reports after the first CSWL task, so we cannot include them in the analysis below. The transcripts can be found in our OSF repository.

Two coders agreed to classify 12 participants (out of 46, i.e., 26%) as being potentially “aware” of the non-native target sounds, contrasts, or minimal pairs: eight participants in the AX condition (36%) and four in the oddity condition (17%). Aware participants include those who commented on how the words sounded very similar, suggesting awareness of the existence of minimal pairs. We also considered aware one participant in the oddity group who commented on vowel length (“I think they hold the vowel longer in the middle or end to signify a different meaning”). Finally, we considered aware the four participants who noticed at least one of the non-native segments. One participant commented on the existence of “pairs of similar words with slightly different vowel sounds.” Three other participants commented on the consonants. For example, participant 321 stated that the “n” sometimes sounded like the “‘n’ in ‘pinata’ or ‘jalepeno’,” and participant 405 reported that “there were words like “P-EE-N-OO” and “P-EE-N-IU” or “P-EI-N-OO”. All of these had different meanings.” In both cases, this suggests awareness of the /ɲ/ sound.

To investigate the effect of awareness on learning, we compared the performance of aware and unaware participants in the combined trained conditions. As shown in Figures 8 and 9, the learning trajectories of aware and unaware participants overlap substantially. Overall accuracy in the CSWL task for unaware participants rose steadily from the first to the final block, but there was a drop in accuracy for aware participants between blocks 10 and 12.

Figure 8. Mean proportion of correct pictures selected in each block of the CSWL task—aware vs. unaware participants.

Figure 9. Mean proportion of correct pictures selected in different trial types—aware (a) vs. unaware participants (b).

We ran mixed-effect models with fixed effects of block, trial type, awareness status (aware vs unaware), and the three-way interaction. The inclusion of trial type (χ2(2) = 17.078, p < .001) and the interaction effect (χ2(5) = 28.858, p < .001) led to better model fit. Awareness (χ2(1) = 0.6941, p = .405) and block (χ2(1) = 0.7406, p = .390) did not influence model fit significantly. This shows that learning performance of the aware and unaware participants did not differ significantly across blocks. The best-fitting model is included in supplement materials Table S3.

Exploratory analysis

As shown in Figure 8, the aware participants showed a decrease in performance from block 10 onwards. Thus, we ran exploratory analyses to test if the aware participants’ peak performance (in blocks 10 and 11) was above chance in consonantal and vocalic minimal pair trials. Since the number of aware participants was small (n = 12) and performance accuracy was not normally distributed, we ran Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The aware participants’ performance in consonantal trials was significantly above chance at block 11 (V = 343, p = .023), but in vocalic trials performance was not above chance (V = 275, p = .291).

The relationship between perceptual discrimination and word learning

We further explored whether there is a link between participants’ perceptual discrimination (as measured by their performance in the AX or oddity discrimination post-test) and their learning outcomes in the CSWL task (measured by performance on the last block). Pearson’s correlation test revealed no significant correlation between participants’ discrimination of the consonant contrasts (/l/-/ʎ/, /n/-/ɲ/) after perception training and their performance on consonantal minimal pair trials at the end of the CSWL task (for AX group: r = 0.0061, p = .98; for oddity group: r = 0.2, p = .34). For the vowel contrasts (/e/-/ɛ/, /o/-/ɔ/) the oddity group’s perceptual discrimination performance did not correlate with their performance in vocalic minimal pair trials at the end of the CSWL task (r = 0.094, p = .66), whereas the AX group’s perceptual performance showed a moderate negative correlation with CSWL learning outcome (r = −0.53, p = .012). Figures 10 and 11 visualize these relationships.

Figure 10. Relationship between performance in the AX discrimination post-test and performance in the final block of the CSWL task—consonant (a) and vowel minimal pair trials (b).

Figure 11. Relationship between performance in the oddity discrimination post-test and performance in the final block of the CSWL task—consonant (a) and vowel minimal pair trials (b).

Study 2: Discussion

Study 2 confirmed the effect of perceptual training on the discrimination of L2 contrasts. The results indicated that the AX discrimination task with feedback led to greater improvement compared to the oddity discrimination task. This is likely because the AX discrimination task was less perceptually and cognitively demanding for the naïve listeners, as it only involved the processing of two sounds in each trial. However, although the group with AX discrimination training improved in perceptual discrimination accuracy, they did not show better learning outcomes in the CSWL task compared to the oddity training and the no-training groups. This means that perceptual improvement did not transfer to the learning of words that contain these contrasts. Additionally, we did not find a positive relationship between perceptual discrimination accuracy and word learning outcome, again confirming that better perception of the non-native contrasts does not directly facilitate word learning. Interestingly, we observed a negative relationship between the discrimination of vowel contrasts and the learning of vowel minimal pair words in the AX training group. One possibility is that AX discrimination training improved participants’ awareness of the existence of different vowels in the words, but this also increased confusion among the vowel minimal pairs because participants had not yet formed the corresponding phonological categories to properly map the sounds to different meanings. This is in line with the greater number of aware participants in the AX training group (n = 8) compared to the oddity training group (n = 4). However, this interpretation needs to be taken with caution because the correlational analysis was based on a small number of CSWL trials (only eight vowel trials at the final block).

These findings highlight the limited transfer from discrimination training to word learning and raise the question of whether alternative training methods, such as identification-based training, could yield more robust learning outcomes. Unlike discrimination tasks, identification training encourages learners to associate sounds with specific labels, promoting phonemic category formation (Bradlow et al., Reference Bradlow, Pisoni, Akahane-Yamada and Tohkura1997; Logan et al., Reference Logan, Lively and Pisoni1991). As discussed in the introduction, only a few studies have directly examined the effects of phonetic training on lexical learning, with most using identification tasks. However, findings remain mixed—some report positive effects on word learning and processing (Ingvalson et al., Reference Ingvalson, Barr and Wong2013; Melnik & Peperkamp, Reference Melnik and Peperkamp2021), while others find no such benefit (Barriuso, Reference Barriuso2018). Thus, whether identification training leads to stronger transfer to word learning remains an open question. Importantly, the feasibility of identification-based training may depend on participants’ prior experience with the target language. Although training can be effective for learners with some L2 exposure, it may be more challenging for naïve participants who lack phonological or lexical representations. In future work, we will address this by using images instead of orthographic forms or phonetic symbols to associate with sounds, hence reducing the cognitive load and supporting learners without formal L2 training. Future research should directly compare discrimination- and identification-based training methods, especially in populations with varying L2 experience, to determine which approach better supports the integration of novel phonological contrasts into the lexicon.

The analyses of the awareness measure suggested no overall difference in learning performance between aware and unaware participants. However, we found that the aware participants showed above-chance performance at block 11 in the consonantal trials, and their performance dropped to chance level at the final block. This could reflect some degree of learning in the consonantal minimal pair trials, though the learning effect was not yet stabilized among the participants. This observation among “aware” participants highlights the potential role of metalinguistic awareness in word learning. Developing explicit awareness during training may be a useful strategy for enhancing L2 word learning outcomes (Ge et al., Reference Ge and Rebuschatunder review), suggesting potential applications in instructional settings where guided attention to phonological contrasts could support word acquisition.

General Discussion

In two studies, we explored the impact of novel phonology and perceptual training on non-native word learning using a CSWL paradigm, which combines methods from implicit and statistical learning research (Monaghan et al., Reference Monaghan, Schoetensack and Rebuschat2019). We found that adult learners can acquire non-native words from cross-situational statistics even when words contain non-native segmental features. Additionally, we manipulated the phonological similarity between words and generated different (non)minimal pair types to resemble natural language learning contexts more closely. Learners’ performance was significantly influenced by how similar the words sounded, suggesting that future word learning research needs to consider the role of phonology more comprehensively. Furthermore, we tested the role of perceptual training in non-native word learning and found that perceptual discrimination training might not be sufficient to support non-native word learning.

Do phonological overlaps and non-native phonological contrasts pose difficulty during cross-situational word learning?

As predicted, in both studies, learners performed better in non-minimal pair trials as compared to minimal pair trials. One explanation is that, in non-minimal pair trials, learners can rely on several phonological cues (e.g., consonants, vowels) to activate the corresponding referent; but in minimal pair trials, most of the cues are uninformative and activate both objects, with only one informative cue indicating the correct referent. Our finding is consistent with previous results of lower performance for minimal pairs (e.g., Escudero et al., Reference Escudero, Smit and Mulak2022; Ge et al., Reference Ge, Monaghan and Rebuschat2025). It was also found that English-native participants had greater difficulty with the consonantal and vocalic minimal pairs than Portuguese-native participants, indicating an impact of non-native phonological contrasts. The target Portuguese contrasts (/l/-/ʎ/, /n/-/ɲ/, /e/-/ɛ/, /o/-/ɔ/) have been found to be perceptually challenging for English-native speakers (for discussion, see Correia et al., Reference Correia, Rato, Ge, Fernandes, Kachlicka, Saito and Rebuschat2025). Inexperienced English-native listeners are likely to perceive the Portuguese sounds /ʎ/ and /ɲ/ as L1 phonemes /l/ (63%) and /n/ (75%) (Rato, Reference Rato2019), and consistently map the vowel /e/ to English /ɛ/ (71%) and /o/ to English /ɔ/ (38%) or /ʊ/ (39%) (Macedo, Reference Macedo2015). Thus, the minimal pair design in our study is similar to Tuninetti et al.’s (Reference Tuninetti, Mulak and Escudero2020) perceptually difficult minimal pairs, where the target non-native contrasts were mapped to either one single L1 vowel category or across multiple L1 categories. However, Tuninetti et al. (Reference Tuninetti, Mulak and Escudero2020) did observe learning of the perceptually difficult minimal pairs, though the performance in these trials was lower than with perceptually easy or non-minimal pairs. This is likely due to the differences in the settings of CSWL. In Tuninetti et al. (Reference Tuninetti, Mulak and Escudero2020), minimal pair words were presented adjacently in the learning trials, which might make the contrasts more salient. Also, presenting two similar-sounding words with two different referent pictures provided a hint that the trivial differences in sounds change meanings. These may direct participants’ attention to the minimal differences in sounds and hence facilitate learning. In our studies, participants never heard the minimal pair words together, and learning relied on their perceptual sensitivity and detecting the non-native contrasts from exposure.

The findings also have implications for immersive L2 learning practice. Our design resembled the more natural language learning situations where learners are not explicitly pre-trained with the phonological and phonetic details of the new language and are required to figure out the important phonemic distinctions from exposure to the language. Under such learning situations, it may be harder for learners to pick up words incidentally from the environment when they contain non-native contrasts. It may be necessary to provide certain explicit training or instruction to help learners with these non-native minimal pairs.

Do different types of perception training tasks facilitate non-native word learning?

The two types of perceptual discrimination training employed in Study 2 did not show a direct influence on learners’ non-native word learning, though there was observed improvement in perceptual abilities after training. This lack of transfer from the perceptual level to the lexical level could result from the type of perception training employed. In the current study, participants were trained with discrimination tasks (AX or oddity), which guided participants to attend to and distinguish the differences in fine-grained phonetic details, but did not focus on mapping the phonetic cues to new phonological categories. Thus, although learners improved in their perceptual discrimination of the contrasts, they did not map the different sounds to different meanings in word learning. An alternative for future study is to train learners with an identification task (Rebuschat et al., in preparation), which may draw learners’ attention to the categorization of non-native speech sounds and eventually promote the formation of new categories (Logan & Pruitt, Reference Logan, Pruitt and Strange1995). Additionally, in the current perceptual training tasks, we did not provide any explicit explanations or instructions on the target contrasts. It is possible that more explicit instructions on the minimal pair words will guide learners’ attention to the target contrasts and lead to better perceptual learning outcomes (De Clercq et al., Reference De Clercq, Valada, Tran, Correia and Housen2023), which further facilitate the recategorization of non-native sounds.

Another important factor may be the lack of generalization from the trained contrasts to the novel words used in the word learning task. While the perceptual training specifically targeted the four Portuguese contrasts, the actual pseudowords used in the CSWL task differed from those used in perception training. It is possible that participants had difficulty generalizing the newly acquired contrasts to novel words. Follow-up studies can be conducted to examine if perceptual training on the same words will be more effective in facilitating non-native word learning.

Overall, the findings suggest that the transfer of perceptual ability to lexical encoding could be more challenging than anticipated, especially for beginner-level language learners, and future designs of phono-lexical training experiments should more rigorously account for the ecological validity of the task and the stimuli complexity for the specific learner group. Since perceptual discrimination training alone may not be sufficient to facilitate word learning, instructional approaches can integrate phonetic training into more meaningful learning contexts. For example, phonetic training can be combined with explicit phonetic instruction, feedback, and multimodal input (e.g., visual and articulatory cues) to help learners develop more robust phonological categories (e.g., Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Darcy, Ewert, Levis and LeVelle2013; Thomson & Derwing, Reference Thomson, Derwing, Levis, Le, Lucic, Simpson and Vo2016). Instead of immediately requiring learners to associate novel phonemes with word meanings, instruction could first establish strong phonological categories through high-variability input (e.g., exposure to different speakers and varied lexical contexts). Once learners demonstrate stable phonemic discrimination, they can transition to word learning tasks that emphasize phoneme-meaning mapping.

While phonetic training methods are important for controlled experimental research, they may not fully reflect the complexities of real-world language learning. To bridge the gap between lab-based training and classroom instruction, future studies can employ more holistic training methods, such as task-based language teaching (TBLT) (Ellis, Reference Ellis2017; Mora & Levkina, Reference Mora and Levkina2017). TBLT emphasizes language use in meaningful, context-rich tasks and may encourage learners to engage with phonological contrasts in more natural, communicative settings. Furthermore, language instruction for beginner learners can consider sequencing phonemic contrasts based on their relative difficulty, introducing perceptually easier contrasts first, and then progressing to more challenging contrasts.

We also acknowledge that the design of the current study may have contributed to the lack of significant learning effects, particularly the use of naïve listeners with no prior exposure to Portuguese and the relatively short training sessions. Unlike previous L2 research, which typically involved learners with some level of language experience and multiple extended training sessions, the current study tested participants after just one substantive training session and a shorter second session. These factors may limit the potential for detecting learning effects and suggest that future studies should consider incorporating longer training sessions and learners with prior exposure to the target language.

Lastly, the complexity of the CSWL task itself may have posed an additional challenge, as evidenced by the unexpectedly poor performance of Portuguese native speakers on certain contrasts. Our exploratory analysis indicated that while Portuguese native speakers showed greater improvement in learning /n/-/ɲ/ and /o/-/ɔ/ contrasts, their performance on /l/-/ʎ/ and /e/-/ɛ/ minimal pairs was not significantly different from that of English native speakers. This asymmetry may reflect differences in perceptual salience, acoustic distinctiveness, or lexical representations of these contrasts in Portuguese. That is, some contrasts may be more robustly encoded and easier to access, even in a decontextualized task like CSWL, whereas others may be more variable even for native speakers. These findings suggest that the role of L1 phonological experience in perceptual learning may be contrast-specific, depending on how strongly each contrast is represented in the native system. Given the challenge associated with the /l/-/ʎ/ and /e/-/ɛ/ contrasts, it is possible that the lack of transfer from phonetic training to word learning in Study 2 reflects not only limitations in the training method but also the difficulty of the CSWL task itself. The task may not be sensitive enough to capture subtle learning improvements, particularly for contrasts that remain challenging even for native speakers.

Additionally, the short duration of the CSWL task may have limited its ability to reveal learning effects from phonetic training. Moreover, since all pseudowords were presented in isolation (i.e., without meaningful context), native speakers may struggle due to their reliance on contextual cues to distinguish similar-sounding words in real-world communication. Future studies can consider incorporating more contextualized learning tasks—such as sentence-based or interactive paradigms—to better assess how phonetic training supports lexical acquisition in ecologically valid settings.

Awareness effect

Although there was no overall performance difference between aware and unaware learners, we did observe some learning effects in the consonantal minimal pair trials for aware participants only. At the penultimate CSWL block, the aware participants showed a peak in performance in consonantal trials and the accuracy was above chance. This indicates that participants who were aware of the non-native minimal pairs had the potential to learn consonantal minimal pairs after a short, implicit exposure of 10–15 minutes. This finding aligns with the awareness report in which some participants explicitly mentioned the /n/-/ɲ/ consonantal contrast. However, this learning effect was not persistent and was missing in the final block. It is worth investigating in future studies whether providing a few more CSWL exposure sessions will allow the aware participants to consolidate the learning effect.

Conclusion

We investigated whether phonetic training on perceptually difficult non-native contrasts benefits the learning of words that contain these contrasts. Our results suggested that phonetic training in the form of perceptual discrimination did not directly help with word learning. It is likely that the discrimination task did not focus on the formation of novel phonological categories that are critical in word learning. Our next step is to employ an identification-based phonetic training task as this method explicitly directs learners’ attention to categorization, potentially promoting the integration of new phonological contrasts into the lexicon.

The findings highlight that perceptual discrimination training may not be effective or efficient in promoting the development of lexical abilities in beginner-level L2 classrooms. This suggests that researchers and practitioners should re-evaluate the types of training tasks that are more facilitative in improving not only perception but also other aspects of language learning (e.g., lexical, syntactic development). After all, the ultimate goal of phonetic training extends beyond sound recognition to the effective use of these sounds in communication. However, it is important to acknowledge that the short duration of training and the complexity of the CSWL task used in this study may have contributed to the lack of significant learning effects. Future research can explore more naturalistic training approaches, such as communicative tasks and high-variability input conditions, which may provide insights into how phonetic training can better support language acquisition in real-world contexts. Additionally, future studies can address key limitations, such as assessing the long-term retention of phonetic and lexical learning and examining how exposure to phonetic contrasts over extended periods influences acquisition.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263125101459.

Data availability statement

The experiment in this article earned Open Data, Open Materials and Pre-Registered badges for transparent practices. The materials and data are available in the following links: Study 1: https://osf.io/qjrm8; Study 2: https://osf.io/egxmu.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by Lancaster University’s Camões Institute Chair (Cátedra) for Multilingualism and Diversity, the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT, grant reference 2022.04013.PTDC), and the Linguistics Research Centre of NOVA University Lisbon (UID/03213/2025 - https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/03213/2025).