Following publication of the Wildlife Atlas of Sabah (Davies, Reference Davies2022), the Malay language translation (Atlas Hidupan Liar Sabah) was published by the Sabah Biodiversity Centre and WWF-Malaysia a year later (Bernard & Davies, Reference Bernard and Davies2023). The Wildlife Atlas provides information on 31 of Sabah’s 216 mammal species, plus six bird species. It represents a collaboration of 38 authors, including 16 from Sabah, from Malaysian government agencies, NGOs and research institutions. Wildlife records were sourced from published reports; museum specimens; unpublished reports and field data from researchers, conservationists, timber and oil palm companies; and global databases (e.g. GBIF, eMammal, Zenodo). This compilation provided > 175,000 field records. Care was taken to exclude uncertain records, and accompanying chapters were written on species’ ecology and conservation based on studies over the past 4 decades.

The information in these chapters allows comparison with results from a faunal survey of Sabah in 1980 (Davies & Payne, Reference Davies and Payne1982). This provides a sense of the scale of change in mammal numbers over the 40 years to 2020, which is often under-appreciated when looking at populations today. It is important to note, however, that it is difficult to make accurate state-wide population estimates, over 73,400 km2, because of the heterogeneity of forest areas, the variation in wildlife ranging and activity patterns, and the differences in survey methods used. As a result, estimating populations through remote, indirect and often rapid assessments (e.g. camera-trapping, helicopter surveys of Bornean orangutan Pongo pygmaeus nests; Asian elephant Elephas maximus dung counts) have wide error margins. A further challenge is that camera-trapping near the forest floor since the 1990s has transformed our understanding of many nocturnal and terrestrial mammals, but under-represents the arboreal forest community (e.g. primates and squirrels), which was therefore given emphasis in the Wildlife Atlas chapters.

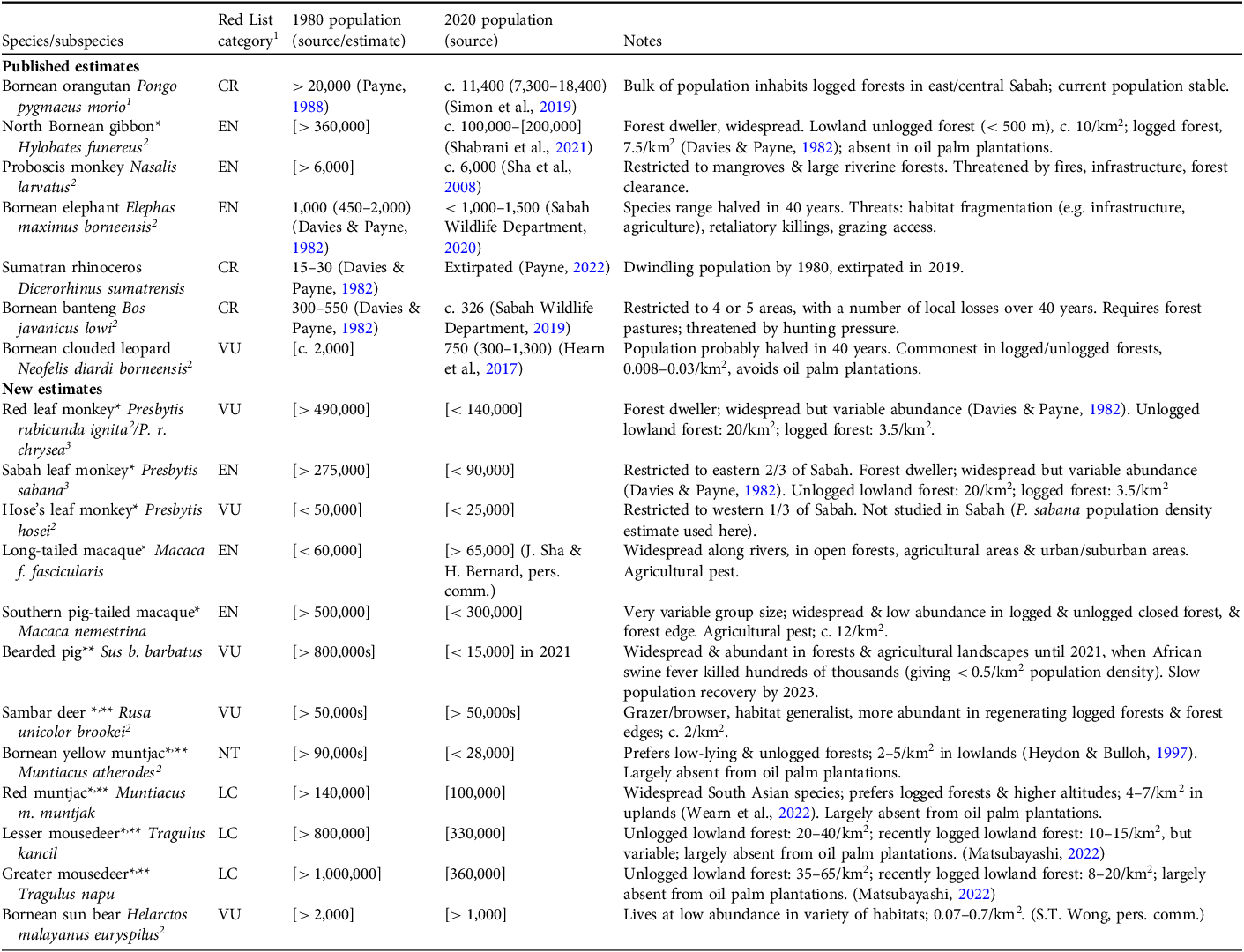

To make comparisons between 1980 and 2020, we consider 19 species (Table 1), for seven of which there are recently published population estimates; for the other 12 species we provide estimates here. Over this period, Sabah’s forests declined from c. 51,500 km2 (McMorrow & Talip, Reference McMorrow and Talip2001) to c. 36,500 km2 (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Potapov, Moore, Hancher, Turubanova and Tyukavina2013, with annual updates providing data for 2020), and the area of unlogged forest declined from c. 26,500 km2 to c. 4,000 km2. The current rate of deforestation has slowed greatly to < 1% per annum (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Potapov, Moore, Hancher, Turubanova and Tyukavina2013: 2020–2023 data), and almost all remaining forest habitat lies within reserves, parks and sanctuaries (Fig. 1). This is mostly logged dipterocarp forest; the distinct but less extensive mangrove, riverine and montane forest communities are not discussed further.

Fig. 1 Commercial Forest Reserves (light shading), Totally Protected Areas (parks, Wildlife Sanctuaries and conservation areas, and Forest Reserves (Class 1, 6 and 7; heavy shading), and agricultural lands (unshaded) in Sabah, northern Borneo (from Sabah Forestry Department, 2020).

Table 1 Published estimates of mammal species population size for seven species, and estimates with wide margins calculated here [in square brackets] for 12 mammal species, in Sabah, northern Borneo, in 1980 and 2020, with their IUCN Red List category and relevant notes.

1CR, Critically Endangered; EN, Endangered; VU, Vulnerable; NT, Near Theatened; LC, Least Concern.

2Borneo endemic.

3Sabah endemic.

* Logging calibration (see text for details).

** Hunting calibration (see text for details).

We made the assessment in four steps. First, 10,000km2 was deducted from both 1980 and 2020 forest area figures to account for high altitude (> 800 m) and badly/recently degraded forests, which are generally less preferred by the species under consideration, giving a reduced forest area for both periods. Second, to estimate mammal populations in unlogged forest, reflecting the ratio of unlogged to logged figures above, 50% of the 1980 reduced forest area (41,500km2), and 10% of the 2020 reduced forest area (26,500 km2) were used, then multiplied by species population density estimates for unlogged forests. Third, to take account of logging, the corresponding 50% of 1980, and 90% of 2020 reduced forest area figures were used and multiplied by population density estimates for that habitat. Both sets of totals were then combined to give estimates for unlogged plus logged forest. Fourth, to account for hunting impacts, a further 20% population reduction (after Benitez-Lopez et al., Reference Benitez-Lopez, Santini, Schipper, Busana and Huijbregts2019) was made for ungulate species at both times. This analysis (Table 1) is discussed below along with ecological information from the Wildlife Atlas of Sabah (where full reference lists can be found).

For the primates, all populations but one have declined by 25–50% of 1980 levels, mostly through forest loss and degradation. The Bornean orangutan retains a viable population of c. 11,400, despite c. 10,000 individuals lost as a result of agriculture expansion, and the North Bornean gibbon Hylobates funereus has a population > 100,000 despite losses of a similar number to logging and agriculture expansion. Both species have adapted to live in regenerating logged forests, as have both species of macaques (Macaca spp.), but unfortunately the three leaf-monkey (langur) species (Presbytis spp.) have not returned to their former abundance, despite being widespread in logged forests.

On the forest floor, two species of muntjac and two species of mousedeer have each declined to c. 30–50% of 1980 levels because of forest loss, and the Bornean yellow muntjac Muntiacus atherodes and greater mousedeer Tragulus napu have additionally not adapted well to logged forests. The impact of hunting on smaller ungulates has been somewhat offset by reproduction/immigration, and even commercial hunting in plantations and farms for bearded pigs Sus barbatus, for food and crop protection, had not substantially reduced their numbers until the precipitous decline in 2021 because of African Swine Fever. This shows how newly arrived diseases can have a sudden and devastating impact, and will likely increase hunting of other ungulates. For the larger species, habitat loss combined with hunting led to the extirpation of the Sumatran rhinoceros Dicerorhinus sumatrensis in 2019; the Bornean banteng Bos javanicus, numbering < 350, could be the next loss and would greatly benefit from a captive breeding programme. The low numbers of sun bears Helarctos malayanus and clouded leopards Neofelis diardi also indicate a need for conservation monitoring and action.

Beyond food acquisition and crop protection, other mammals at risk from market demands include the Sunda pangolin Manis javanica (whole body/scales), sun bear (bile and claws), and elephant (ivory). If demand for any of these species’ parts increases substantially, they could quickly be extirpated. Plans to encourage 1 million tourists per year may create a large new market unless the tourists adhere to Sabah’s wildlife protection laws. Likewise, plans to develop Indonesia’s new capital city in neighbouring Kalimantan will increase market pressures on Sabah’s wildlife, which could lead to wildlife losses even where good forest habitats are maintained.

The development of c. 17,000 km2 as monoculture oil palm plantations since the 1980s, mostly in the fertile eastern lowlands that once held high mammal population densities, has been the main driver of the substantial declines of both arboreal and terrestrial mammals. Some orangutans can remain at low numbers in plantation areas, traversing planted areas along the ground and using forest patches for food, although they tend to suffer so-called refugee crowding (Husson et al., Reference Husson, Wich, Marshall, Dennis, Ancrenaz, Brassey, Wich, Atmoko, Setia and van Schaik2009). Elephants also pass through these plantations, feeding on grasses and palms, which sometimes leads to damaging conflicts with growers, but they cannot survive in oil palm plantations alone. There are only a few species that have developed survival strategies to make frequent use of oil palm plantations, although usually also using nearby natural forests: pigs, macaques, the leopard cat Prionailurus javanensis, some civets (e.g. Viverra tangalunga), some squirrels (Callosciurus spp.), and the monitor lizard Varanus salvator.

In conclusion, our understanding of mammal ecology in Sabah has greatly improved in the last 40 years, to give a reasonable platform for effective conservation policy and practice, as long as mammal populations continue to be monitored and adaptive actions are taken when needed. The optimistic view is that Sabah will retain its remaining array of species, including many endemic species and subspecies (Table 1), and there are progressive policy opportunities to support this.

Firstly, Malaysia’s forestry policy (Reference Shabrani, Kapis, Tindok, Zuraimi, Simon and Davies2021) has a national commitment to maintain 50% forest cover, and Sabah has gone a step further with a target of maintaining 30% of land in Totally Protected Areas (currently 20,118 km2; 27% of the land area). Most of Sabah’s protected forests have been logged, but neither further timber extraction nor agricultural activity are now permitted, and the forests are regenerating naturally. The remaining 15,865 km2 of commercial (Class II) Forest Reserves are intended for sustainable timber production, and the combined production and protected forest area provides sufficient suitable habitat to support viable populations of even the rarest mammals. Future development of industrial tree plantations needs careful planning, however, to maintain connectivity and minimize loss of areas of high conservation value.

Secondly, ongoing hunting for food and crop protection needs to be managed through licensing and other regulations, but particular attention needs to be focused on preventing the hunting of larger species, especially the banteng, which also requires forest pastures, and other species of medicinal or ornamental market value.

Thirdly, although oil palm plantations are largely unsuitable for wildlife, plantation owners can still support wildlife conservation. They can allocate parts of their land to restore wildlife corridors between isolated forest blocks; provide a shield for adjacent forests by enforcing hunting bans for their staff, and prohibiting hunters accessing forests through their estates; and contribute wildlife records. Such actions, along with social and economic standards, will support certification for sustainable production of oil palm, and the Sabah government is working towards a jurisdictional approach to certified sustainable crop production across the state.

In addition to forest loss and over-hunting, other threats to wildlife include new plans for roads, mining and plantations that could cause forest fragmentation and loss, and climate change impacts may exacerbate all these pressures. Careful spatial planning will be needed to minimize and mitigate damaging effects, and these plans need to include both climate vulnerability and wildlife health risk assessments, so that a combination of threats does not lead to further loss of species.

Author contributions

Study design, writing, revision: GD, HB, AS, SJ, JW; data compilation, analysis: AS, SJ, JW; policy and conservation analysis: GD, HB, RJ, GJ.

Acknowledgements

The Wildlife Atlas project is a collaboration between the Sabah Biodiversity Centre and WWF-Malaysia, funded through WWF-UK, HSBC, Unilever & Beiersdorf, and a Sabah State government grant. We thank Mark Ivan for mapping, and Liz Bennett, John Payne and the Editor for review comments.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.

Data availability

Data were obtained from a collaboration between different parties with specific conditions, and are not available. Data sharing agreements for WWF-Malaysia data can be negotiated.