1. Introduction

Over 20 % of the Earth’s surface can be characterized as hilly or mountainous terrain (e.g. Körner et al. Reference Körner, Hassan, Scholes and Ash2005). Although tall mountainous regions of the world garner substantial focus in meteorology (e.g. Bougeault et al. Reference Bougeault, Binder, Buzzi, Dirks, Kuettner, Houze, Smith, Steinacker and Volkert2001; Grubišić et al. Reference Grubišić2008; Houze et al. Reference Houze2017), the Earth’s hypsographic curve interestingly shows that most of Earth’s terrain is less than 1000 m in height (e.g. Lagrula Reference Lagrula1968; Cawood et al. Reference Cawood, Chowdhury, Mulder, Hawkesworth, Capitanio, Gunawardana and Nebel2022). Even in large-scale mountainous terrain, terrain height spectra demonstrate substantial variance at small scales (e.g. Young & Pielke Reference Young and Pielke1983). While today’s weather, air pollution and climate models can potentially resolve the larger-scale terrain features (e.g. mountains), the ability to resolve gentle small-scale hills currently remains beyond reach in larger-scale models. Due to the prevalence of small-scale hills, understanding their influence on turbulent flow is also essential for proper measurement interpretation, and for describing pollutant, aerosol and seed transport, and for predicting wind throw and wind energy availability (e.g. Finnigan et al. Reference Finnigan, Ayotte, Harman, Katul, Oldroyd, Patton, Poggi, Ross and Taylor2020).

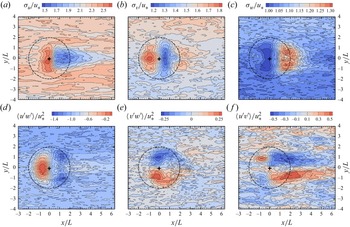

Under neutrally stratified conditions, inviscid incompressible flow over a low symmetric obstacle produces a pressure minima occurring at the obstacle crest but does not generate any resistance (drag) because the pressure perturbation remains symmetric relative to the obstacle in the absence of any momentum stress (e.g. d’Alembert Reference d’Alembert1752; Calero Reference Calero2018). In laminar incompressible flow, the addition of finite viscosity ensures a thickening of the boundary layer (a greater separation of the streamlines) in a hill-like obstacle’s lee due to the spatially varying action of viscous drag which produces a pressure perturbation phase-shifted slightly downstream relative to the obstacle resulting in form drag (typically referred to as sheltering, e.g. Prandtl (Reference Prandtl1904)). Turbulent incompressible flows over hills also produce form drag through sheltering but the turbulent stresses dominate the smaller viscous stresses resulting in even larger pressure asymmetry relative to the hill shape producing even larger drag (e.g. Jackson & Hunt Reference Jackson and Hunt1975; Britter, Hunt & Richards Reference Britter, Hunt and Richards1981; Hunt, Leibovich & Richards Reference Hunt, Leibovich and Richards1988; Belcher, Newley & Hunt Reference Belcher, Newley and Hunt1993). Characteristics of the hill can alter the flow’s evolution over the obstacle, e.g. flow over steeper hills induces larger amplitude pressure perturbations and this obstacle-induced pressure perturbation can generate a sufficiently large near-surface adverse pressure-gradient on the hill’s lee that downward turbulent transport of momentum from aloft becomes insufficient to counter the adverse pressure-gradient producing flow separation; whether the flow separates or not dramatically alters the pressure field and hence the overall form drag felt by the outer flow (e.g. Taylor, Mason & Bradley Reference Taylor, Mason and Bradley1987; Finnigan et al. Reference Finnigan, Raupach, Bradley and Aldis1990; Wood & Mason Reference Wood and Mason1993; Athanassiadou & Castro Reference Athanassiadou and Castro2001). Because surface roughness alters the turbulence, variations in surface roughness also modulate flow responses to hills and the induced separation (e.g. Britter et al. Reference Britter, Hunt and Richards1981; Ayotte & Hughes Reference Ayotte and Hughes2004; Tamura, Okuno & Sugio Reference Tamura, Okuno and Sugio2007). Flow over two-dimensional (2D) versus three-dimensional (3D) hills (e.g. ridges versus isolated hills) also differs substantially because of the ability for flow over 3D hills to divert around the hill, which produces spanwise shear around the edges of and in the lee of the hill altering the turbulence and separation by generating additional instabilities and vortices (e.g. Mason & Sykes Reference Mason and Sykes1979; Hunt & Snyder Reference Hunt and Snyder1980; Mason & King Reference Mason and King1985; Arya & Gadiyaram Reference Arya and Gadiyaram1986; Gong & Ibbetson Reference Gong and Ibbetson1989; Ishihara, Hibi & Oikawa Reference Ishihara, Hibi and Oikawa1999; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Cao, Liu and Ishihara2019a , Reference Liu, Diao and Ishiharab , Reference Liu, Wang, Wang and Ishihara2020).

Because mountainous and hilly terrain compresses climate zones and creates small-scale habitat diversity, these regions support more than one quarter of the Earth’s terrestrial biodiversity (e.g. Körner et al. Reference Körner, Hassan, Scholes and Ash2005). Hilly terrain is therefore frequently forested. Finnigan & Belcher (Reference Finnigan and Belcher2004) demonstrated using linearized theory that because forests interact with the flow through pressure drag, forests on hills can shift the hill-induced pressure perturbation enough to induce separation at notably smaller slopes than expected over hills of similarly specified roughness. Finnigan & Belcher’s (Reference Finnigan and Belcher2004) theory also predicts that flow separation should depend on the distribution and density of the canopy elements, which Patton & Katul (Reference Patton and Katul2009) later confirmed. Researchers such as Wilson, Finnigan & Raupach (Reference Wilson, Finnigan and Raupach1998), Poggi et al. (Reference Poggi, Katul, Albertson and Ridolfi2007) and Ross (Reference Ross2008) discussed that within-canopy turbulence mixing length scales vary with position over sinusoidally repeating forested hills. When investigating turbulent flow over observed Amazonian terrain, Chen, Chamecki & Katul (Reference Chen, Chamecki and Katul2020) found separated flow even in the lee of small bumps, and Chamecki et al. (Reference Chamecki, Freire, Dias, Chen, Dias-Junior, Toledo Machado, Sörgel, Tsokankunku and de Araújo2020) and Chen & Chamecki (Reference Chen and Chamecki2023) showed that imbalances in above-canopy turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) budgets can result from upstream terrain influences. With the exception of Chamecki et al. (Reference Chamecki, Freire, Dias, Chen, Dias-Junior, Toledo Machado, Sörgel, Tsokankunku and de Araújo2020), Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Chamecki and Katul2020) and Chen & Chamecki (Reference Chen and Chamecki2023), much of this literature discussing turbulence over forested hills has focused on 2D sinusoidally repeating hills.

To our knowledge, Finnigan & Brunet (Reference Finnigan, Brunet, Coutts and Grace1995) represents the first effort describing within- and above-canopy turbulent flow over isolated forested hills, where they documented that above-canopy streamlines dip into the canopy at approximately one-third the way up the windward side of a 2D isolated hill that can eliminate (or even reverse) the inflection point in the mean velocity profile expected in canopy-flows (e.g. Raupach, Finnigan & Brunet Reference Raupach, Finnigan and Brunet1996; Finnigan, Shaw & Patton Reference Finnigan, Shaw and Patton2009); a phenomenon that has important implications for turbulence production at canopy-top. Neff & Meroney (Reference Neff and Meroney1998) found that canopy-gaps influence hill-induced fractional speed-up factors and flow separation. Through two-point correlation analysis, Dupont & Brunet (Reference Dupont and Brunet2008) noted that turbulence in the intermittent leeward separation zone is not correlated with canopy-top turbulence on the windward side of the hill. Grant et al. (Reference Grant, Ross, Gardiner and Mobbs2015) found key features predicted by Finnigan & Belcher’s (Reference Finnigan and Belcher2004) theory in their field measurements over an isolated forested ridge. For a given hill shape, Ma et al. (Reference Ma, Liu, Banerjee, Katul, Yi and Pardyjak2020) demonstrated that variation in a canopy’s morphology modulates the position, strength and depth of the leeward separation bubble. Similar to Wood (Reference Wood2000) who discussed flow over hills with unresolved roughness, Tolladay & Chemel (Reference Tolladay and Chemel2021) demonstrated resolution influences on key turbulence statistics in large-eddy simulation (LES) of flow over the same isolated forested ridge as that studied by Ma et al. (Reference Ma, Liu, Banerjee, Katul, Yi and Pardyjak2020). These efforts have enhanced the general understanding of the role tall vegetation plays in modulating turbulent flow over infinitely long isolated ridges; how canopies modulate turbulence over 3D hills remains understudied.

Towards understanding the role that hill shape and slope play in modulating turbulence, we analyse four LESs of turbulent flow over isolated forested hills. These four simulations include two each at two different hill slopes. For each hill slope, the simulations conducted include one targeting flow over an infinitely wide 2D hill and one over an axisymmetric 3D hill. In collaboration with the effort reported here, colleagues conducted a comprehensive WT experiment studying neutrally stratified turbulent over 3D forested hills (figure 1, Harman & Finnigan Reference Harman and Finnigan2018). The numerical simulations attempt to reproduce the physical WT simulations over axisymmetric 3D hills (Harman & Finnigan Reference Harman and Finnigan2018) and 2D hills.

Figure 1. A photograph of the forested isolated axisymmetric 3D steep (

![]() $s_m =\,$

0.26) cosine hill surface in the wind tunnel (WT) (Harman & Finnigan Reference Harman and Finnigan2018).

$s_m =\,$

0.26) cosine hill surface in the wind tunnel (WT) (Harman & Finnigan Reference Harman and Finnigan2018).

The outline of this manuscript is as follows: § 2 discusses current theory describing turbulent flow over forested hills. Section 3 describes the simulations investigated. Section 4 outlines the techniques used to analyse the simulation data. Section 5 compares the simulation results against WT measurements from Harman & Finnigan (Reference Harman and Finnigan2018). Section 6 describes the mean flow and turbulence response to variations in hill shape and slope. Section 7 interrogates turbulence/mean-flow phase relationships at key heights above the surface towards advancing current theory, and § 8 summarizes the findings.

2. Current theory describing turbulent flow over forested hills

Current analytic theory of turbulent shear flow over low hills (e.g. Jackson & Hunt Reference Jackson and Hunt1975; Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Leibovich and Richards1988; Belcher et al. Reference Belcher, Newley and Hunt1993) has provided an enduring and consistent framework for analysis and understanding of flow over low hills and even over steeper hills upwind of the separation region. The theory divides the flow into different layers, where the perturbations to the mean flow caused by the hill are governed by distinctly different dynamics. Separate solutions to the flow equations are found for each layer and then these are matched asymptotically between the layers. For hills of sufficiently low-slope to ignore flow separation, Hunt et al. (Reference Hunt, Leibovich and Richards1988) defined two main regions: (i) the outer region, where the response to the pressure field generated by flow over the hill is inviscid, and (ii) the inner region, where perturbations to the turbulent Reynolds stresses affect the perturbations to the mean flow. Each of these regions was further divided into two layers. The middle layer, of depth

![]() $h_m$

, is the lower part of the outer region through which flow responses are inviscid but rotational to accommodate shear in the approach flow. In the upper layer, extending from

$h_m$

, is the lower part of the outer region through which flow responses are inviscid but rotational to accommodate shear in the approach flow. In the upper layer, extending from

![]() $h_m$

to the top of the boundary layer, flow responses are irrotational and can be computed by potential theory. The inner region consists of the shear stress layer of depth

$h_m$

to the top of the boundary layer, flow responses are irrotational and can be computed by potential theory. The inner region consists of the shear stress layer of depth

![]() $h_i$

, and the thin inner surface layer, of depth

$h_i$

, and the thin inner surface layer, of depth

![]() $l_s$

, which allows formal matching with a surface boundary condition.

$l_s$

, which allows formal matching with a surface boundary condition.

Finnigan & Belcher (Reference Finnigan and Belcher2004) extended the analytic theory of Hunt et al. (Reference Hunt, Leibovich and Richards1988) to hills covered by tall plant canopies by replacing the thin inner surface layer by a deep plant canopy parameterized by linearized flow equations in the upper canopy but where the unavoidably nonlinear dynamics in the lower canopy were treated heuristically. Harman & Finnigan (Reference Harman and Finnigan2009, Reference Harman and Finnigan2013) further developed Finnigan & Belcher (Reference Finnigan and Belcher2004) to accommodate more realistic 2D hills, and then Harman & Finnigan (Reference Harman and Finnigan2021) extended the theory to 3D hills.

In all of these small perturbation theories, whether over hills covered by a rough surface or a tall canopy, identifying the depths of the inner shear stress layer,

![]() $h_i$

, and the middle layer,

$h_i$

, and the middle layer,

![]() $h_m$

, is critical to applying the theory. To derive the formula for

$h_m$

, is critical to applying the theory. To derive the formula for

![]() $h_m$

, Hunt et al. (Reference Hunt, Leibovich and Richards1988) assumed that the flow approaching the hill could be described by a logarithmic profile in equilibrium with the upstream surface while in the inner shear stress layer

$h_m$

, Hunt et al. (Reference Hunt, Leibovich and Richards1988) assumed that the flow approaching the hill could be described by a logarithmic profile in equilibrium with the upstream surface while in the inner shear stress layer

![]() $h_i$

, the interdependence of the perturbations to the turbulent shear stresses and the perturbations to the mean shear are assumed to obey the same mixing length flux-gradient relationship as in an equilibrium log law. Finnigan & Belcher (Reference Finnigan and Belcher2004) relies on the same formulae for

$h_i$

, the interdependence of the perturbations to the turbulent shear stresses and the perturbations to the mean shear are assumed to obey the same mixing length flux-gradient relationship as in an equilibrium log law. Finnigan & Belcher (Reference Finnigan and Belcher2004) relies on the same formulae for

![]() $h_m$

and

$h_m$

and

![]() $h_i$

as Hunt et al. (Reference Hunt, Leibovich and Richards1988).

$h_i$

as Hunt et al. (Reference Hunt, Leibovich and Richards1988).

The formulae for

![]() $h_m$

and

$h_m$

and

![]() $h_i$

assume the flow over the hill remains attached (i.e. no flow separation). Over steeper 2D hills and over 3D hills, this assumption breaks down. If the flow separates, streamlines that were following the surface contour upwind leave the surface and delineate the boundary of a separation bubble. Downwind of the separation point the scale of the largest turbulent eddies increases abruptly. In the attached flow the largest eddies are limited by the local distance to the surface but after separation the largest eddies span the bubble depth, which is typically

$h_i$

assume the flow over the hill remains attached (i.e. no flow separation). Over steeper 2D hills and over 3D hills, this assumption breaks down. If the flow separates, streamlines that were following the surface contour upwind leave the surface and delineate the boundary of a separation bubble. Downwind of the separation point the scale of the largest turbulent eddies increases abruptly. In the attached flow the largest eddies are limited by the local distance to the surface but after separation the largest eddies span the bubble depth, which is typically

![]() ${ {O}}(H)$

with

${ {O}}(H)$

with

![]() $H$

representing the hill height. While the streamlines approaching a 3D hill in its plane of lateral symmetry go over the hill-centreline, streamlines to either side are deflected forming space curves whose principal normals intersect the hill surface at right angles (Finnigan Reference Finnigan2024).

$H$

representing the hill height. While the streamlines approaching a 3D hill in its plane of lateral symmetry go over the hill-centreline, streamlines to either side are deflected forming space curves whose principal normals intersect the hill surface at right angles (Finnigan Reference Finnigan2024).

As fluid parcels above the canopy advect over the hill, changes to the Reynolds stresses reflect the competing effects of two processes. First, the existing eddies are stretched and rotated by the mean flow as they follow the mean streamlines. Second, nonlinear interactions between the eddies will tend to equalize

![]() $T\!K\!E$

between their orthogonal components

$T\!K\!E$

between their orthogonal components

![]() $u^{\prime}$

,

$u^{\prime}$

,

![]() $v^{\prime}$

and

$v^{\prime}$

and

![]() $w^{\prime}$

, and to transfer TKE to finer scale eddies where it is ultimately dissipated to heat through the action of viscosity. These effects are represented formally in the conservation equations for the turbulent normal and shear stresses,

$w^{\prime}$

, and to transfer TKE to finer scale eddies where it is ultimately dissipated to heat through the action of viscosity. These effects are represented formally in the conservation equations for the turbulent normal and shear stresses,

![]() $\langle u'^2 \rangle$

,

$\langle u'^2 \rangle$

,

![]() $\langle v'^2 \rangle$

,

$\langle v'^2 \rangle$

,

![]() $\langle w'^2 \rangle$

,

$\langle w'^2 \rangle$

,

![]() $\langle u'w' \rangle$

,

$\langle u'w' \rangle$

,

![]() $\langle v'w' \rangle$

and

$\langle v'w' \rangle$

and

![]() $T\!K\!E$

, where

$T\!K\!E$

, where

![]() $T\!K\!E = (\langle u'^2 \rangle + \langle v'^2 \rangle + \langle w'^2 \rangle )/2$

. In these equations, the so-called production terms describe the transfer of kinetic energy from the mean flow to the larger energy-containing eddies of the turbulence while the turbulent diffusion and pressure-strain terms describe the nonlinear interactions between these eddies, which break them down and destroy their coherence. These nonlinear interactions determine

$T\!K\!E = (\langle u'^2 \rangle + \langle v'^2 \rangle + \langle w'^2 \rangle )/2$

. In these equations, the so-called production terms describe the transfer of kinetic energy from the mean flow to the larger energy-containing eddies of the turbulence while the turbulent diffusion and pressure-strain terms describe the nonlinear interactions between these eddies, which break them down and destroy their coherence. These nonlinear interactions determine

![]() $\tau$

, the time over which the large eddies remain coherent enough to receive energy directly from the mean flow. Here

$\tau$

, the time over which the large eddies remain coherent enough to receive energy directly from the mean flow. Here

![]() $\tau$

can be taken as

$\tau$

can be taken as

![]() $\tau \sim T\!K\!E/\epsilon$

, where

$\tau \sim T\!K\!E/\epsilon$

, where

![]() $\epsilon$

is the rate of viscous dissipation of TKE. This definition is strictly only applicable to equilibrium situations, where the rate of viscous dissipation is in balance with the transfer of kinetic energy from the mean flow to the turbulence, but we will assume that is also indicative of the rate at which these large eddies lose their coherence as they interact with each other during their passage over the hill.

$\epsilon$

is the rate of viscous dissipation of TKE. This definition is strictly only applicable to equilibrium situations, where the rate of viscous dissipation is in balance with the transfer of kinetic energy from the mean flow to the turbulence, but we will assume that is also indicative of the rate at which these large eddies lose their coherence as they interact with each other during their passage over the hill.

In regions where the time scale of hill-induced changes in the mean flow is small compared with

![]() $\tau$

(i.e. in the so-called rapid distortion regimes), the turbulent stresses will reflect their recent history of straining and rotation by the mean flow and Hunt et al. (Reference Hunt, Leibovich and Richards1988) assumes that this will be the case in the outer region in general and in the middle layer in particular. In regions where mean flow changes are slow compared with

$\tau$

(i.e. in the so-called rapid distortion regimes), the turbulent stresses will reflect their recent history of straining and rotation by the mean flow and Hunt et al. (Reference Hunt, Leibovich and Richards1988) assumes that this will be the case in the outer region in general and in the middle layer in particular. In regions where mean flow changes are slow compared with

![]() $\tau$

, the turbulence will approach a state of local equilibrium between the rate of straining by the mean flow and the resulting Reynolds stresses so that their relationship can be described by an eddy viscosity. Current theory assumes that we should observe this behaviour in the inner shear stress layer,

$\tau$

, the turbulence will approach a state of local equilibrium between the rate of straining by the mean flow and the resulting Reynolds stresses so that their relationship can be described by an eddy viscosity. Current theory assumes that we should observe this behaviour in the inner shear stress layer,

![]() $z \lt h_i$

.

$z \lt h_i$

.

Beneath the inner layer and above the ground surface lies the canopy layer, which introduces additional length scales (

![]() $L_c$

and

$L_c$

and

![]() $h_c$

), through the addition of canopy drag and the no-slip condition at the surface. In the canopy, turbulent stresses are complicated by wake production,

$h_c$

), through the addition of canopy drag and the no-slip condition at the surface. In the canopy, turbulent stresses are complicated by wake production,

![]() $W_p$

, i.e. the production of turbulent eddies at scales defined by the canopy elements and associated short-circuiting of the inertial energy cascade (Finnigan Reference Finnigan2000; Shaw & Patton Reference Shaw and Patton2003). In addition, viscous dissipation increases by the work performed by the turbulence against the viscous drag of the canopy elements (Ayotte, Finnigan & Raupach Reference Ayotte, Finnigan and Raupach1999; Shaw & Patton Reference Shaw and Patton2003). For dense canopies (

$W_p$

, i.e. the production of turbulent eddies at scales defined by the canopy elements and associated short-circuiting of the inertial energy cascade (Finnigan Reference Finnigan2000; Shaw & Patton Reference Shaw and Patton2003). In addition, viscous dissipation increases by the work performed by the turbulence against the viscous drag of the canopy elements (Ayotte, Finnigan & Raupach Reference Ayotte, Finnigan and Raupach1999; Shaw & Patton Reference Shaw and Patton2003). For dense canopies (

![]() $h_c/L_c \gt 1$

), canopy drag eliminates the importance for the flow dynamics of shear stress at the underlying surface but at the same time ensures strong vertical gradients in turbulent stresses. Finally, behind the hill crest, the strong adverse pressure gradient can cause reversed flow and separation, which introduces the hill height

$h_c/L_c \gt 1$

), canopy drag eliminates the importance for the flow dynamics of shear stress at the underlying surface but at the same time ensures strong vertical gradients in turbulent stresses. Finally, behind the hill crest, the strong adverse pressure gradient can cause reversed flow and separation, which introduces the hill height

![]() $H$

as an additional length scale affecting the turbulence.

$H$

as an additional length scale affecting the turbulence.

3. Simulation description and configuration

Numerical models of turbulent flow over forested hills take many forms that each provide value with varying levels of accuracy and cost (see recent review by Finnigan et al. (Reference Finnigan, Ayotte, Harman, Katul, Oldroyd, Patton, Poggi, Ross and Taylor2020)). Analytical models provide extremely timely solutions, but typically linearize the nonlinear equations that describe turbulent flow (e.g. Finnigan & Belcher Reference Finnigan and Belcher2004; Poggi et al. Reference Poggi, Katul, Finnigan and Belcher2008; Harman & Finnigan Reference Harman and Finnigan2009, Reference Harman and Finnigan2013). Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes models solve the full nonlinear equations but averaged over space and time such that the influence of turbulence is fully parameterized (e.g. Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Finnigan and Raupach1998; Katul & Chang Reference Katul and Chang1999; Ross & Vosper Reference Ross and Vosper2005, among others). Similar to Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes, LES also solves the full nonlinear equations but relies on relatively isotropic grids and only spatially averages (or filters) the equations at scales smaller than the grid resolution, such that the largest scales of turbulence (i.e. those performing most of the transport) are resolved by the grid and only the smallest scales of turbulence (which primarily act to dissipate energy) must be parameterized (e.g. Moeng & Sullivan Reference Moeng and Sullivan2015). Although it is computationally expensive, LES has become a close counterpart to field and laboratory experiments over the past 30 plus years because of its ability to accurately simulate the time-evolving and spatially evolving response of turbulence to varying forcing over complex surfaces (e.g. Wood Reference Wood2000; Patton & Katul Reference Patton and Katul2009; Sullivan, McWilliams & Patton Reference Sullivan, McWilliams and Patton2014; Chamecki et al. Reference Chamecki, Freire, Dias, Chen, Dias-Junior, Toledo Machado, Sörgel, Tsokankunku and de Araújo2020).

In our LES, the governing equations describe 3D time-dependent turbulent winds in a dry incompressible Boussinesq atmospheric boundary layer, including (i) three transport equations for momentum

![]() $\rho {\boldsymbol{u}}$

, (ii) a transport equation for a conserved scalar variable, (iii) a discrete Poisson equation for a pressure variable

$\rho {\boldsymbol{u}}$

, (ii) a transport equation for a conserved scalar variable, (iii) a discrete Poisson equation for a pressure variable

![]() $p$

to enforce incompressibility and (iv) closure expressions for subgrid-scale (SGS) variables, e.g. an equation for SGS TKE

$p$

to enforce incompressibility and (iv) closure expressions for subgrid-scale (SGS) variables, e.g. an equation for SGS TKE

![]() $e$

(see Sullivan et al. Reference Sullivan, McWilliams and Patton2014). The physical processes included in the LES boundary-layer equations include, temporal time tendencies, advection, pressure gradients, divergence of SGS fluxes, buoyancy, resolved turbulence, and in the case of the SGS

$e$

(see Sullivan et al. Reference Sullivan, McWilliams and Patton2014). The physical processes included in the LES boundary-layer equations include, temporal time tendencies, advection, pressure gradients, divergence of SGS fluxes, buoyancy, resolved turbulence, and in the case of the SGS

![]() $e$

equation also diffusion and dissipation.

$e$

equation also diffusion and dissipation.

Explicit spatial filtering of the momentum equations in the presence of vegetative-canopy elements generates terms representing canopy-induced pressure and viscous drag (Finnigan & Shaw Reference Finnigan and Shaw2008) which are parameterized using a time-dependent and local velocity-squared type drag law, e.g.

where,

![]() $a$

is the canopy’s frontal area density and

$a$

is the canopy’s frontal area density and

![]() $c_d$

is a drag coefficient describing the canopy’s efficiency at absorbing momentum. Dissipation in the SGS energy equation is also augmented by the work SGS motions perform against the canopy-induced form drag. See Shaw & Patton (Reference Shaw and Patton2003), Patton & Katul (Reference Patton and Katul2009) and Patton et al. (Reference Patton, Sullivan, Shaw, Finnigan and Weil2016) for further details of the canopy representation in the LES.

$c_d$

is a drag coefficient describing the canopy’s efficiency at absorbing momentum. Dissipation in the SGS energy equation is also augmented by the work SGS motions perform against the canopy-induced form drag. See Shaw & Patton (Reference Shaw and Patton2003), Patton & Katul (Reference Patton and Katul2009) and Patton et al. (Reference Patton, Sullivan, Shaw, Finnigan and Weil2016) for further details of the canopy representation in the LES.

By applying a transformation to the physical space coordinates

![]() $(x,y,z)$

that maps them onto flat computational coordinates

$(x,y,z)$

that maps them onto flat computational coordinates

![]() $(\xi ,\eta ,\zeta )$

, Sullivan et al. (Reference Sullivan, McWilliams and Patton2014) adapted our flat LES (Sullivan & Patton Reference Sullivan and Patton2011) to a situation with a 3D time-evolving lower boundary shape

$(\xi ,\eta ,\zeta )$

, Sullivan et al. (Reference Sullivan, McWilliams and Patton2014) adapted our flat LES (Sullivan & Patton Reference Sullivan and Patton2011) to a situation with a 3D time-evolving lower boundary shape

![]() $h = h(x,y,t)$

. The current simulations use this same framework, but impose a time-independent surface, e.g.

$h = h(x,y,t)$

. The current simulations use this same framework, but impose a time-independent surface, e.g.

![]() $h = h(x,y)$

where the maximum hill slope

$h = h(x,y)$

where the maximum hill slope

![]() $s_m = \text {max}( {\partial h}/{\partial x})$

. Of importance is that we transform the coordinates, not the flow variables. Therefore, horizontal velocity components (

$s_m = \text {max}( {\partial h}/{\partial x})$

. Of importance is that we transform the coordinates, not the flow variables. Therefore, horizontal velocity components (

![]() $u$

,

$u$

,

![]() $v$

) are defined in a right-handed Cartesian coordinate system parallel to the flat surface surrounding each hill (with

$v$

) are defined in a right-handed Cartesian coordinate system parallel to the flat surface surrounding each hill (with

![]() $u$

aligned with the imposed pressure gradient force in the

$u$

aligned with the imposed pressure gradient force in the

![]() $+x$

direction, and

$+x$

direction, and

![]() $v$

positive to the left of the imposed pressure gradient force in the

$v$

positive to the left of the imposed pressure gradient force in the

![]() $+y$

direction), and vertical velocity (

$+y$

direction), and vertical velocity (

![]() $w$

) is defined positive upward from the underlying flat surface (the

$w$

) is defined positive upward from the underlying flat surface (the

![]() $+z$

direction) aligned opposite to the gravitational force (although the flow under consideration is neutrally stratified, so gravitational forces are ignored).

$+z$

direction) aligned opposite to the gravitational force (although the flow under consideration is neutrally stratified, so gravitational forces are ignored).

The simulations discretize a 4096

![]() $\times$

2048

$\times$

2048

![]() $\times$

512 m

$\times$

512 m

![]() $^3$

domain using 2048

$^3$

domain using 2048

![]() $\times$

1024

$\times$

1024

![]() $\times$

256 grid points. The computational mesh in physical space is surface following and non-orthogonal. Vertical grid lines are held fixed at a particular

$\times$

256 grid points. The computational mesh in physical space is surface following and non-orthogonal. Vertical grid lines are held fixed at a particular

![]() $(x,y)$

location but the horizontal grid lines undergo vertical translation according to the vertical variation of the underlying surface. While the grid resolution in the horizontal directions is fixed for all horizontal locations, the vertical grid is refined near the surface to resolve near-surface/canopy processes and is then algebraically stretched above the canopy to push the upper boundary far above the hill to minimize any influence of the upper boundary on the hill-induced pressure field. Care is taken to ensure that every grid volume uses an aspect ratio no larger than

$(x,y)$

location but the horizontal grid lines undergo vertical translation according to the vertical variation of the underlying surface. While the grid resolution in the horizontal directions is fixed for all horizontal locations, the vertical grid is refined near the surface to resolve near-surface/canopy processes and is then algebraically stretched above the canopy to push the upper boundary far above the hill to minimize any influence of the upper boundary on the hill-induced pressure field. Care is taken to ensure that every grid volume uses an aspect ratio no larger than

![]() $5:1$

attempting to reasonably satisfy isotropy assumptions used to close the equations in the SGS model.

$5:1$

attempting to reasonably satisfy isotropy assumptions used to close the equations in the SGS model.

Figure 2. Example of the horizontal domains used and the idealized cosine-shaped 2D and 3D hills. Panel (b) reflects the axisymmetric case with

![]() $L = L_y = L_x$

. The blue line spanning the domain at

$L = L_y = L_x$

. The blue line spanning the domain at

![]() $x$

= 1024 m depicts the downwind boundary of the horizontally homogeneous periodic region, while the green line spanning the domain at

$x$

= 1024 m depicts the downwind boundary of the horizontally homogeneous periodic region, while the green line spanning the domain at

![]() $x \sim$

3892 m depicts the beginning of the fringe region where the solutions begin to be nudged back to those at the downwind edge of the upwind periodic region starting at the green line located at

$x \sim$

3892 m depicts the beginning of the fringe region where the solutions begin to be nudged back to those at the downwind edge of the upwind periodic region starting at the green line located at

![]() $x \sim$

820 m. Periodic boundary conditions are imposed in the

$x \sim$

820 m. Periodic boundary conditions are imposed in the

![]() $y$

-direction. The vertical domain extends up to 512 m.

$y$

-direction. The vertical domain extends up to 512 m.

Spatial differencing is pseudospectral in the horizontal computational directions

![]() $(\xi , \eta )$

and is second-order finite difference in

$(\xi , \eta )$

and is second-order finite difference in

![]() $\zeta$

. Time stepping uses a low-storage third-order Runge–Kutta scheme, and the time step

$\zeta$

. Time stepping uses a low-storage third-order Runge–Kutta scheme, and the time step

![]() $\delta t$

is picked dynamically based on a fixed Courant–Fredrichs–Lewy number.

$\delta t$

is picked dynamically based on a fixed Courant–Fredrichs–Lewy number.

An important development for this effort involves implementing a turbulent inflow fringe (or precursor) method which is compatible with our pseudospectral spatial differencing and third-order Runge–Kutta time differencing (Schlatter, Adams & Kleiser Reference Schlatter, Adams and Kleiser2005; Munters, Meneveau & Meyers Reference Munters, Meneveau and Meyers2016) to enable simulation of flow over isolated 2D and 3D hills. The strategy involves simulating two interconnected periodic domains, where the flow in the upwind domain is periodic and representative of flow over an infinitely long horizontally homogeneous forested surface. The outflow of that upwind domain serves as inflow for the downwind domain containing the hill. In the second domain at the boundary far downstream from the hill, nudging terms are applied over the downwind-most 102 grid points (from grid points 1946–2048) to force the exit flow of the larger downwind domain to match the flow exiting the upstream region (note that 102 grid points is 20 % of the upwind domain). Hence both domains use periodic boundary conditions in the

![]() $x$

direction, but the flow impinging on the hill is unaware of any upstream hills. It is important to note two things: (i) the size of the upstream inflow domain dictates the largest scales of motion impinging on the hill located in the downstream domain, and (ii) the chosen fringe strategy used in these simulations was developed prior to and differs from the two-domain strategy discussed in Sullivan et al. (Reference Sullivan, McWilliams, Weil, Patton and Fernando2020, Reference Sullivan, McWilliams, Weil, Patton and Fernando2021) that ensures decoupling of inflow conditions from any slight imperfections in the spectral tapering (e.g. Inoue, Matheou & Teixeira Reference Inoue, Matheou and Teixeira2014) and which enables inclusion of Coriolis and buoyancy forces. (For these reasons, we recommend using the technique described by Sullivan et al. (Reference Sullivan, McWilliams, Weil, Patton and Fernando2020, Reference Sullivan, McWilliams, Weil, Patton and Fernando2021) for future studies.) Figure 2 shows the total extent of the horizontal domain for the two steeper hill configurations (

$x$

direction, but the flow impinging on the hill is unaware of any upstream hills. It is important to note two things: (i) the size of the upstream inflow domain dictates the largest scales of motion impinging on the hill located in the downstream domain, and (ii) the chosen fringe strategy used in these simulations was developed prior to and differs from the two-domain strategy discussed in Sullivan et al. (Reference Sullivan, McWilliams, Weil, Patton and Fernando2020, Reference Sullivan, McWilliams, Weil, Patton and Fernando2021) that ensures decoupling of inflow conditions from any slight imperfections in the spectral tapering (e.g. Inoue, Matheou & Teixeira Reference Inoue, Matheou and Teixeira2014) and which enables inclusion of Coriolis and buoyancy forces. (For these reasons, we recommend using the technique described by Sullivan et al. (Reference Sullivan, McWilliams, Weil, Patton and Fernando2020, Reference Sullivan, McWilliams, Weil, Patton and Fernando2021) for future studies.) Figure 2 shows the total extent of the horizontal domain for the two steeper hill configurations (

![]() $s_m =$

0.26). The blue lines in figure 2 mark the boundaries where periodicity in the

$s_m =$

0.26). The blue lines in figure 2 mark the boundaries where periodicity in the

![]() $x$

direction is enforced. The green lines in figure 2 mark the starting point of the region where the nudging algorithm operates, with the left-hand side showing the horizontally homogeneous region used to nudge the downstream flow back to horizontally homogeneous flow that is unaware of the hill and the right-hand side showing the region that is nudged back to the upwind conditions. Periodic boundary conditions are imposed in the lateral (

$x$

direction is enforced. The green lines in figure 2 mark the starting point of the region where the nudging algorithm operates, with the left-hand side showing the horizontally homogeneous region used to nudge the downstream flow back to horizontally homogeneous flow that is unaware of the hill and the right-hand side showing the region that is nudged back to the upwind conditions. Periodic boundary conditions are imposed in the lateral (

![]() $y$

) direction, the upper boundary is a frictionless rigid lid, and the lower boundary beneath the trees uses a rough-wall neutrally stratified drag law with a surface roughness length

$y$

) direction, the upper boundary is a frictionless rigid lid, and the lower boundary beneath the trees uses a rough-wall neutrally stratified drag law with a surface roughness length

![]() $z_{\circ } = 1\times 10^{-3}$

m.

$z_{\circ } = 1\times 10^{-3}$

m.

To minimize the computational expense, all the simulations are generated by first integrating a smaller

![]() $512\times 512\times 256$

grid point flat-domain simulation out in time using periodic horizontal boundary conditions until the initially laminar flow develops from divergence free random fluctuations into 3D turbulence that is in equilibrium with the imposed pressure gradient. Upon reaching equilibrium, a restart volume is saved. This volume is then mirrored one time in the lateral (

$512\times 512\times 256$

grid point flat-domain simulation out in time using periodic horizontal boundary conditions until the initially laminar flow develops from divergence free random fluctuations into 3D turbulence that is in equilibrium with the imposed pressure gradient. Upon reaching equilibrium, a restart volume is saved. This volume is then mirrored one time in the lateral (

![]() $y$

) and four times in the downwind (

$y$

) and four times in the downwind (

![]() $x$

) directions to create a fully turbulent initial condition for the full large-domain simulations. The code is then reconfigured to: (i) restart from this larger volume, and (ii) run using the precursor inflow boundary condition in the along-wind (

$x$

) directions to create a fully turbulent initial condition for the full large-domain simulations. The code is then reconfigured to: (i) restart from this larger volume, and (ii) run using the precursor inflow boundary condition in the along-wind (

![]() $x$

) direction. Upon restart, a hill is gradually grown into the downwind portion of the domain over a period of 400 s. Averaging begins after integrating forward in this configuration for approximately one large-eddy turnover time to allow the turbulence to evolve into the new configuration. Running on 2048 CPUs on an HPE SGI ICE XA system (Computational and Information Systems Laboratory 2019), the (2D; 3D)-hill simulations required approximately (77; 366) wallclock hours, respectively.

$x$

) direction. Upon restart, a hill is gradually grown into the downwind portion of the domain over a period of 400 s. Averaging begins after integrating forward in this configuration for approximately one large-eddy turnover time to allow the turbulence to evolve into the new configuration. Running on 2048 CPUs on an HPE SGI ICE XA system (Computational and Information Systems Laboratory 2019), the (2D; 3D)-hill simulations required approximately (77; 366) wallclock hours, respectively.

As in the WT measurements (Harman & Finnigan Reference Harman and Finnigan2018), the flow is neutrally stratified (no buoyancy) and Coriolis forces are ignored. The hills are of cosine shape,

where,

![]() $H$

is the hill height. In the 2D-hill case,

$H$

is the hill height. In the 2D-hill case,

and, in the 3D-hill case,

\begin{equation} \widehat {x} = \left [ \left (\frac {x - x_{\circ }}{L_x}\right )^2 + \left (\frac {y - y_{\circ }}{L_y}\right )^2 \right ]^{\frac {1}{2}}\!, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \widehat {x} = \left [ \left (\frac {x - x_{\circ }}{L_x}\right )^2 + \left (\frac {y - y_{\circ }}{L_y}\right )^2 \right ]^{\frac {1}{2}}\!, \end{equation}

where

![]() $L_x$

and

$L_x$

and

![]() $L_y$

are the hill lengths at the hill half-height in the

$L_y$

are the hill lengths at the hill half-height in the

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $y$

directions, respectively, and (

$y$

directions, respectively, and (

![]() $x_{\circ }, y_{\circ }$

) represent the physical location of the hill crest. In the axisymmetric 3D hill simulations,

$x_{\circ }, y_{\circ }$

) represent the physical location of the hill crest. In the axisymmetric 3D hill simulations,

![]() $L_x = L_y = L$

. Variations in hill steepness are generated by keeping

$L_x = L_y = L$

. Variations in hill steepness are generated by keeping

![]() $H$

fixed and varying

$H$

fixed and varying

![]() $L$

. Scaling up the WT hills by a factor of 256,

$L$

. Scaling up the WT hills by a factor of 256,

![]() $H = 12.8$

m for all cases; see table 1 for the matching values of

$H = 12.8$

m for all cases; see table 1 for the matching values of

![]() $L$

. Figure 3 shows examples of the surfaces investigated with the LES. The

$L$

. Figure 3 shows examples of the surfaces investigated with the LES. The

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

grid lines follow this surface and algebraically relax back to horizontal grid lines parallel to the upwind flat surface at approximately the domain half-height (see (4) in Sullivan et al. (Reference Sullivan, McWilliams and Patton2014), where we use

$y$

grid lines follow this surface and algebraically relax back to horizontal grid lines parallel to the upwind flat surface at approximately the domain half-height (see (4) in Sullivan et al. (Reference Sullivan, McWilliams and Patton2014), where we use

![]() $\varpi = 3$

).

$\varpi = 3$

).

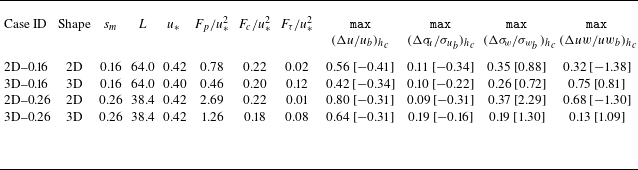

Table 1. Bulk parameters from each of the four simulations. Here

![]() $s_m$

is the maximum hill slope (

$s_m$

is the maximum hill slope (

![]() $\text {max}( {\partial h}/{\partial x})$

),

$\text {max}( {\partial h}/{\partial x})$

),

![]() $L$

is the length of the hill (m) in the streamwise direction

$L$

is the length of the hill (m) in the streamwise direction

![]() $x$

at half the hill height (so the total hill length is 4L),

$x$

at half the hill height (so the total hill length is 4L),

![]() $u_*$

is the friction velocity (m s

$u_*$

is the friction velocity (m s

![]() $^{-1}$

) evaluated at

$^{-1}$

) evaluated at

![]() $x = -4L$

and

$x = -4L$

and

![]() $z = h_c$

(consistent with

$z = h_c$

(consistent with

![]() $u_*$

observed in the WT; when averaged over the entire upwind periodic domain,

$u_*$

observed in the WT; when averaged over the entire upwind periodic domain,

![]() $u_* = 0.42$

m s

$u_* = 0.42$

m s

![]() $^{-1}$

for all cases). Here

$^{-1}$

for all cases). Here

![]() $F_p = - \int _{-2L}^{2L}\langle p \rangle h_x\,{\rm d}x$

is the streamwise surface pressure drag integrated over the hill (e.g. the hill-induced pressure force on the air) normalized by

$F_p = - \int _{-2L}^{2L}\langle p \rangle h_x\,{\rm d}x$

is the streamwise surface pressure drag integrated over the hill (e.g. the hill-induced pressure force on the air) normalized by

![]() $u_*^2$

, where

$u_*^2$

, where

![]() $h_x = {\partial h}/{\partial x}$

is the

$h_x = {\partial h}/{\partial x}$

is the

![]() $x$

-varying hill slope),

$x$

-varying hill slope),

![]() $F_c = - \,c_d\,a \int _{-2L}^{2L}\int _{0}^{h_c} \langle |u_i| u \rangle \,{\rm d}z\,{\rm d}x$

is the hill- and canopy-integrated drag induced by the canopy in the streamwise direction and

$F_c = - \,c_d\,a \int _{-2L}^{2L}\int _{0}^{h_c} \langle |u_i| u \rangle \,{\rm d}z\,{\rm d}x$

is the hill- and canopy-integrated drag induced by the canopy in the streamwise direction and

![]() $F_{\tau } = \int _{-2L}^{2L}\langle u'w' \rangle \,{\rm d}x$

is the hill-integrated streamwise surface stress; the total drag felt by the flow over the hill

$F_{\tau } = \int _{-2L}^{2L}\langle u'w' \rangle \,{\rm d}x$

is the hill-integrated streamwise surface stress; the total drag felt by the flow over the hill

![]() $F_T = F_p + F_c + F_{\tau }$

. Here max

$F_T = F_p + F_c + F_{\tau }$

. Here max

![]() $(\Delta u/u_b)_{ h_c}$

, max

$(\Delta u/u_b)_{ h_c}$

, max

![]() $(\Delta \sigma _{\!u}/\sigma _{u_b})_{ h_c}$

, max

$(\Delta \sigma _{\!u}/\sigma _{u_b})_{ h_c}$

, max

![]() $(\Delta \sigma _{\!w}/\sigma _{w_b})_{ h_c}$

and max

$(\Delta \sigma _{\!w}/\sigma _{w_b})_{ h_c}$

and max

![]() $(\Delta uw/uw_b)_{ h_c}$

are the maximum hill- and canopy-induced speedup, standard deviation of streamwise and vertical velocity, and vertical flux of streamwise momentum increase at canopy top along hill centreline, respectively, where

$(\Delta uw/uw_b)_{ h_c}$

are the maximum hill- and canopy-induced speedup, standard deviation of streamwise and vertical velocity, and vertical flux of streamwise momentum increase at canopy top along hill centreline, respectively, where

![]() $\Delta u/u_b = [(\langle u \rangle - \langle u \rangle _{b}) / \langle u \rangle _{b}]$

,

$\Delta u/u_b = [(\langle u \rangle - \langle u \rangle _{b}) / \langle u \rangle _{b}]$

,

![]() $\Delta \sigma _{u}/\sigma _{u_b} = [(\sigma _u - \sigma _{u_{b}}) / \sigma _{u_{b}}]$

,

$\Delta \sigma _{u}/\sigma _{u_b} = [(\sigma _u - \sigma _{u_{b}}) / \sigma _{u_{b}}]$

,

![]() $\Delta \sigma _w/\sigma _{w_{b}} = [(\sigma _w - \sigma _{w_{b}}) / \sigma _{w_{b}}]$

and

$\Delta \sigma _w/\sigma _{w_{b}} = [(\sigma _w - \sigma _{w_{b}}) / \sigma _{w_{b}}]$

and

![]() $\Delta uw/uw_b = [(\langle u'w' \rangle - \langle u'w' \rangle _{b}) / \langle u'w' \rangle _{b}]$

evaluated at a height of

$\Delta uw/uw_b = [(\langle u'w' \rangle - \langle u'w' \rangle _{b}) / \langle u'w' \rangle _{b}]$

evaluated at a height of

![]() $h_c$

above the local surface

$h_c$

above the local surface

![]() $h$

, the notation

$h$

, the notation

![]() $_{b}$

refers to a reference value upwind of the hill (Appendix A) and the adjacent values in square brackets reflects the

$_{b}$

refers to a reference value upwind of the hill (Appendix A) and the adjacent values in square brackets reflects the

![]() $x/L$

location where the maximum canopy-top value is found.

$x/L$

location where the maximum canopy-top value is found.

The canopy parameters are derived directly from measurements of the rods used in the WT experiments (Harman & Finnigan Reference Harman and Finnigan2018). In the WT, the rods are 15 mm tall, 5 mm in diameter (

![]() $d_r$

), and are spaced at 12.5 mm intervals in the

$d_r$

), and are spaced at 12.5 mm intervals in the

![]() $x$

direction and 25 mm in the

$x$

direction and 25 mm in the

![]() $y$

direction. Hence, the number of rods per unit area

$y$

direction. Hence, the number of rods per unit area

![]() $n_r$

= 3200 m

$n_r$

= 3200 m

![]() $^{-2}$

and the rods have a frontal area density

$^{-2}$

and the rods have a frontal area density

![]() $a = n_r \times r_d =$

16 m

$a = n_r \times r_d =$

16 m

![]() $^2$

m

$^2$

m

![]() $^{-3}$

that is constant with height. Fitting the WT observed profiles with the rods installed on flat terrain (Harman & Finnigan Reference Harman and Finnigan2018, figure 2

a) to the Harman & Finnigan (Reference Harman and Finnigan2007) roughness sublayer (RSL) theory reveals that the rods have an effective canopy length scale

$^{-3}$

that is constant with height. Fitting the WT observed profiles with the rods installed on flat terrain (Harman & Finnigan Reference Harman and Finnigan2018, figure 2

a) to the Harman & Finnigan (Reference Harman and Finnigan2007) roughness sublayer (RSL) theory reveals that the rods have an effective canopy length scale

![]() $L_c = (c_d\,a)^{-1}$

= 110 mm. Therefore, the drag coefficient

$L_c = (c_d\,a)^{-1}$

= 110 mm. Therefore, the drag coefficient

![]() $c_d$

of the rods is 0.57. In the numerical simulations, these rod parameters are applied to a canopy of height

$c_d$

of the rods is 0.57. In the numerical simulations, these rod parameters are applied to a canopy of height

![]() $h_c$

= 3.84 m resolved by nine grid points on the flat portion of the domain and by 10 grid points at the hill crest due to the terrain following coordinate system. To mimic the WT experiments, the canopy is prescribed to be horizontally homogeneous for all four simulations. Figure 1 shows an image of the WT configuration with the steep-sloped (

$h_c$

= 3.84 m resolved by nine grid points on the flat portion of the domain and by 10 grid points at the hill crest due to the terrain following coordinate system. To mimic the WT experiments, the canopy is prescribed to be horizontally homogeneous for all four simulations. Figure 1 shows an image of the WT configuration with the steep-sloped (

![]() $s_m =$

0.26) axisymmetric canopy-covered hill installed.

$s_m =$

0.26) axisymmetric canopy-covered hill installed.

Figure 3. A zoomed presentation of the 2D (a) and 3D-axisymmetric (b) cosine hills interrogated. In (a),

![]() $L = L_x$

and

$L = L_x$

and

![]() $L_y$

is not defined, and in (b)

$L_y$

is not defined, and in (b)

![]() $L = L_x = L_y$

.

$L = L_x = L_y$

.

![]() $H$

is the hill height (3.2). The green surface depicts canopy top

$H$

is the hill height (3.2). The green surface depicts canopy top

![]() $h_c$

.

$h_c$

.

To classify the current simulations within the context of previous work, we first turn to the Hunt et al. (Reference Hunt, Leibovich and Richards1988) and Finnigan & Belcher (Reference Finnigan and Belcher2004) theories discussed in § 2. In both theories, the middle layer depth (

![]() $h_m$

) is defined as

$h_m$

) is defined as

![]() $h_m \sim L\,[\text{ln}(h_m / z_{\circ })]^{{1}/{2}}$

, and the inner layer depth (

$h_m \sim L\,[\text{ln}(h_m / z_{\circ })]^{{1}/{2}}$

, and the inner layer depth (

![]() $h_i$

) is defined as

$h_i$

) is defined as

![]() $h_i \sim 2\,L\,\kappa ^2 / \text{ln}(h_i / z_{\circ })$

, where

$h_i \sim 2\,L\,\kappa ^2 / \text{ln}(h_i / z_{\circ })$

, where

![]() $\kappa$

is von Kármán’s constant. However, calculating

$\kappa$

is von Kármán’s constant. However, calculating

![]() $h_i$

and

$h_i$

and

![]() $h_m$

using these formulations can lead to physically implausible values over surfaces covered with tall roughness, i.e.

$h_m$

using these formulations can lead to physically implausible values over surfaces covered with tall roughness, i.e.

![]() $h_i$

can end up being found at heights within the canopy of roughness elements (Finnigan et al. Reference Finnigan, Raupach, Bradley and Aldis1990). Therefore, Appendix B derives new formulae for

$h_i$

can end up being found at heights within the canopy of roughness elements (Finnigan et al. Reference Finnigan, Raupach, Bradley and Aldis1990). Therefore, Appendix B derives new formulae for

![]() $h_i$

and

$h_i$

and

![]() $h_m$

incorporating changes to the logarithmic mean velocity profile and the accompanying flux-gradient relationship which occur over a tall plant canopy (Harman & Finnigan Reference Harman and Finnigan2007, Reference Harman and Finnigan2008); labelled

$h_m$

incorporating changes to the logarithmic mean velocity profile and the accompanying flux-gradient relationship which occur over a tall plant canopy (Harman & Finnigan Reference Harman and Finnigan2007, Reference Harman and Finnigan2008); labelled

![]() $\widehat {h_m}$

and

$\widehat {h_m}$

and

![]() $\widehat {h_i}$

using similar notation to Harman & Finnigan (Reference Harman and Finnigan2007, Reference Harman and Finnigan2008). For the configurations discussed here,

$\widehat {h_i}$

using similar notation to Harman & Finnigan (Reference Harman and Finnigan2007, Reference Harman and Finnigan2008). For the configurations discussed here,

![]() $\widehat {h_m}$

$\widehat {h_m}$

![]() $\sim$

(32.8, 21.7) m and

$\sim$

(32.8, 21.7) m and

![]() $\widehat {h_i}$

$\widehat {h_i}$

![]() $\sim$

(11.8, 9.8) m for cases with

$\sim$

(11.8, 9.8) m for cases with

![]() $s_m =$

(0.16, 0.26), respectively, where these values represent their physical height above the origin of the above-canopy coordinates

$s_m =$

(0.16, 0.26), respectively, where these values represent their physical height above the origin of the above-canopy coordinates

![]() $z = d + z_{\circ }$

in the upwind flow (Appendix B). For reference,

$z = d + z_{\circ }$

in the upwind flow (Appendix B). For reference,

![]() $h_i$

for the current configuration using this same reference height is

$h_i$

for the current configuration using this same reference height is

![]() $\sim$

(9.3, 7.2) m, respectively, and

$\sim$

(9.3, 7.2) m, respectively, and

![]() $h_m = \widehat {h_m}$

.

$h_m = \widehat {h_m}$

.

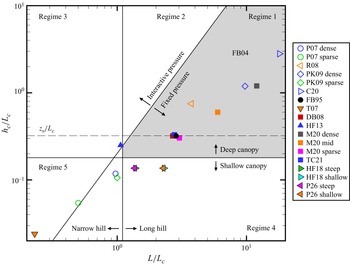

Figure 4. Length scale regime diagram following Poggi et al. (Reference Poggi, Katul, Finnigan and Belcher2008) mapping the hill geometry and canopy morphology of the current numerical (labelled P26) and WT (Harman & Finnigan Reference Harman and Finnigan2018, HF18) simulations relative to previous research on turbulent flow over low forested hills. Here, low hills implies that

![]() $H/L \ll 1$

with

$H/L \ll 1$

with

![]() $H$

the hill height, and

$H$

the hill height, and

![]() $L$

the hill half-length at half the hill height. Here

$L$

the hill half-length at half the hill height. Here

![]() $h_c$

is the canopy height, and

$h_c$

is the canopy height, and

![]() $L_c$

is the canopy adjustment length. Low hills with

$L_c$

is the canopy adjustment length. Low hills with

![]() $L/L_c \lt 1.1$

are deemed `narrow’, and with

$L/L_c \lt 1.1$

are deemed `narrow’, and with

![]() $L/L_c \gt 1.1$

‘long’. Canopies with

$L/L_c \gt 1.1$

‘long’. Canopies with

![]() $h_c/L_c \lt 0.18$

are deemed ‘shallow’, and

$h_c/L_c \lt 0.18$

are deemed ‘shallow’, and

![]() $h_c/L_c \gt 0.18$

`deep’, where

$h_c/L_c \gt 0.18$

`deep’, where

![]() $0.18 = 2\beta ^2$

when

$0.18 = 2\beta ^2$

when

![]() $\beta = {u_*}/{u}|_{h_c} = 0.3$

. From Finnigan & Belcher (Reference Finnigan and Belcher2004, FB04), the envelope

$\beta = {u_*}/{u}|_{h_c} = 0.3$

. From Finnigan & Belcher (Reference Finnigan and Belcher2004, FB04), the envelope

![]() $h_c/L_c = 2(H/L)(L/L_c)^2$

delineates the regime in which the mean within-canopy vertical velocity is expected to be sufficiently large to affect the outer layer pressure. Previous research included Finnigan & Brunet (Reference Finnigan, Brunet, Coutts and Grace1995, FB95), Tamura et al. (Reference Tamura, Okuno and Sugio2007, T07, where

$h_c/L_c = 2(H/L)(L/L_c)^2$

delineates the regime in which the mean within-canopy vertical velocity is expected to be sufficiently large to affect the outer layer pressure. Previous research included Finnigan & Brunet (Reference Finnigan, Brunet, Coutts and Grace1995, FB95), Tamura et al. (Reference Tamura, Okuno and Sugio2007, T07, where

![]() $\beta = 0.3$

is assumed), Poggi et al. (Reference Poggi, Katul, Albertson and Ridolfi2007, P07), Dupont & Brunet (Reference Dupont and Brunet2008, DB08), Ross (Reference Ross2008, R08), Patton & Katul (Reference Patton and Katul2009, PK09), Harman & Finnigan (Reference Harman and Finnigan2013, HF13), Ma et al. (Reference Ma, Liu, Banerjee, Katul, Yi and Pardyjak2020, M20), Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Chamecki and Katul2020, C20) and Tolladay & Chemel (Reference Tolladay and Chemel2021, TC21). Open symbols reflect work on sinusoidally repeating low forested hills, and filled symbols reflect work on isolated forested hills. Symbols without a black outline study flow over low 2D forested hills (ridges), those with a black outline study flow over low 3D forested hills. The thin long-dash black line marks the canopy height at which one would expect separation

$\beta = 0.3$

is assumed), Poggi et al. (Reference Poggi, Katul, Albertson and Ridolfi2007, P07), Dupont & Brunet (Reference Dupont and Brunet2008, DB08), Ross (Reference Ross2008, R08), Patton & Katul (Reference Patton and Katul2009, PK09), Harman & Finnigan (Reference Harman and Finnigan2013, HF13), Ma et al. (Reference Ma, Liu, Banerjee, Katul, Yi and Pardyjak2020, M20), Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Chamecki and Katul2020, C20) and Tolladay & Chemel (Reference Tolladay and Chemel2021, TC21). Open symbols reflect work on sinusoidally repeating low forested hills, and filled symbols reflect work on isolated forested hills. Symbols without a black outline study flow over low 2D forested hills (ridges), those with a black outline study flow over low 3D forested hills. The thin long-dash black line marks the canopy height at which one would expect separation

![]() $z_s$

for the current canopy configuration according to FB04.

$z_s$

for the current canopy configuration according to FB04.

Secondly, figure 4 presents a regime diagram following that proposed by Poggi et al. (Reference Poggi, Katul, Finnigan and Belcher2008) that characterizes the simulations based upon key length scales determining canopy influences on the flow. The length scales of importance are the canopy height

![]() $h_c$

, canopy adjustment length

$h_c$

, canopy adjustment length

![]() $L_c$

and the hill half-length at half the hill height

$L_c$

and the hill half-length at half the hill height

![]() $L$

. Regime 1 marks the region where the Finnigan & Belcher (Reference Finnigan and Belcher2004, FB04) theory is valid. In Regime 2, deviations from the FB04 theory can be attributed to within-canopy vertical velocities being of sufficient amplitude to alter the pressure in the inner layer above the canopy; i.e. when

$L$

. Regime 1 marks the region where the Finnigan & Belcher (Reference Finnigan and Belcher2004, FB04) theory is valid. In Regime 2, deviations from the FB04 theory can be attributed to within-canopy vertical velocities being of sufficient amplitude to alter the pressure in the inner layer above the canopy; i.e. when

![]() $L/L_c$

is large, the canopy flow adjusts to the pressure gradient more rapidly than the pressure gradient changes (Belcher, Harman & Finnigan Reference Belcher, Harman and Finnigan2011). In Regime 3, such deviations can be attributed to both pressure and advection. In Regime 4, the canopy is insufficiently deep or dense to absorb all the momentum and hence within-canopy turbulence is influenced by finite shear stress at the underlying surface. All of these processes are at play for flows in Regime 5. Figure 4 shows that the current simulations fall within Regime 4, a regime that falls outside the applicability of current theory (e.g. Finnigan & Belcher Reference Finnigan and Belcher2004; Harman & Finnigan Reference Harman and Finnigan2009, Reference Harman and Finnigan2013) and which has not received much attention in the literature.

$L/L_c$

is large, the canopy flow adjusts to the pressure gradient more rapidly than the pressure gradient changes (Belcher, Harman & Finnigan Reference Belcher, Harman and Finnigan2011). In Regime 3, such deviations can be attributed to both pressure and advection. In Regime 4, the canopy is insufficiently deep or dense to absorb all the momentum and hence within-canopy turbulence is influenced by finite shear stress at the underlying surface. All of these processes are at play for flows in Regime 5. Figure 4 shows that the current simulations fall within Regime 4, a regime that falls outside the applicability of current theory (e.g. Finnigan & Belcher Reference Finnigan and Belcher2004; Harman & Finnigan Reference Harman and Finnigan2009, Reference Harman and Finnigan2013) and which has not received much attention in the literature.

The numerical and physical WT simulations differ in that a constant external pressure gradient (

![]() $\varPi _x = 1.63\times 10^{-4}$

m s

$\varPi _x = 1.63\times 10^{-4}$

m s

![]() $^{-2}$

, selected to reproduce

$^{-2}$

, selected to reproduce

![]() $u_*$

observed in the tunnel) drives the flow in the

$u_*$

observed in the tunnel) drives the flow in the

![]() $x$

-direction in the LES, while the WT is a zero pressure-gradient tunnel. The flow sampled in the WT therefore represents an internal boundary layer driven by downward transport of momentum from the free stream airflow above, while the LES simulations represent a pressure-gradient driven fully developed boundary layer that is turbulent throughout the domain.

$x$

-direction in the LES, while the WT is a zero pressure-gradient tunnel. The flow sampled in the WT therefore represents an internal boundary layer driven by downward transport of momentum from the free stream airflow above, while the LES simulations represent a pressure-gradient driven fully developed boundary layer that is turbulent throughout the domain.

Another aspect of the numerical simulations that differs from the WT physical simulations is that the numerical simulations use periodic boundary conditions in the lateral direction, while the WT has viscous sidewall boundary layers. The horizontal dimensions of the numerical simulation domain are selected to ensure that the flow interacting with the 3D hills remains independent of the problem design. In the configuration with 3D hills (table 1), the hill only occupies a maximum of

![]() $\sim$

3 % of the lateral domain that should ensure that any hill-induced flow perturbations are negligible at the lateral boundaries.

$\sim$

3 % of the lateral domain that should ensure that any hill-induced flow perturbations are negligible at the lateral boundaries.

4. Analysis procedures

Analysis of the 2D- and 3D-hill simulations differ because the 2D simulations contain an homogeneous horizontal direction, i.e. the lateral (

![]() $y$

) direction, while the 3D simulations do not. In the 2D-hill case, mean flow fields and higher moments are laterally averaged and time-averaged during the simulation and statistics are calculated during postprocessing. Analysis of the 3D simulations relies solely upon time averages (analogous to single-point WT measurements) based upon first-, second- and third-order moments calculated at every time step during the simulation. For the 2D-hill cases, a turbulent fluctuation is defined as a deviation from an instantaneous lateral average and higher moments are calculated as laterally averaged products which are then time-averaged over the duration of the simulation. For the 3D-hill cases, a turbulent fluctuation is defined as a deviation from a time-average at a single point and higher moments are calculated as time-averaged products of those fluctuations. The notation

$y$

) direction, while the 3D simulations do not. In the 2D-hill case, mean flow fields and higher moments are laterally averaged and time-averaged during the simulation and statistics are calculated during postprocessing. Analysis of the 3D simulations relies solely upon time averages (analogous to single-point WT measurements) based upon first-, second- and third-order moments calculated at every time step during the simulation. For the 2D-hill cases, a turbulent fluctuation is defined as a deviation from an instantaneous lateral average and higher moments are calculated as laterally averaged products which are then time-averaged over the duration of the simulation. For the 3D-hill cases, a turbulent fluctuation is defined as a deviation from a time-average at a single point and higher moments are calculated as time-averaged products of those fluctuations. The notation

![]() $\langle \phantom {\,}\rangle$

is used to denote a mean and a

$\langle \phantom {\,}\rangle$

is used to denote a mean and a

![]() $'$

for a fluctuation from that mean.

$'$

for a fluctuation from that mean.

To compare the numerical and WT simulations, all flow variables are normalized by time-averaged friction velocity

![]() $u_*$

evaluated at canopy top (

$u_*$

evaluated at canopy top (

![]() $z/h_c = 1$

) and at

$z/h_c = 1$

) and at

![]() $x/L = -4$

, which is characteristic of the undisturbed flow approaching the hill. The actual

$x/L = -4$

, which is characteristic of the undisturbed flow approaching the hill. The actual

![]() $u_*$

values derived from the simulations can be found in table 1, note that the small

$u_*$

values derived from the simulations can be found in table 1, note that the small

![]() $u_*$

variations shown in table 1 reflect a slight need for additional averaging. The simulations are currently averaged over 150 000 time steps (or, if we define a large-eddy turnover time

$u_*$

variations shown in table 1 reflect a slight need for additional averaging. The simulations are currently averaged over 150 000 time steps (or, if we define a large-eddy turnover time

![]() $\tau _{\ell }$

as the height of the domain (512 m) divided by the friction velocity

$\tau _{\ell }$

as the height of the domain (512 m) divided by the friction velocity

![]() $u_*$

, 150 000 time steps is

$u_*$

, 150 000 time steps is

![]() $\sim$

8

$\sim$

8

![]() $\tau _{\ell }$

). Two characteristic length scales are used: (i) the length of the hill at half its height in the along-wind direction

$\tau _{\ell }$

). Two characteristic length scales are used: (i) the length of the hill at half its height in the along-wind direction

![]() $L$

, and (ii) the canopy height

$L$

, and (ii) the canopy height

![]() $h_c$

.

$h_c$

.

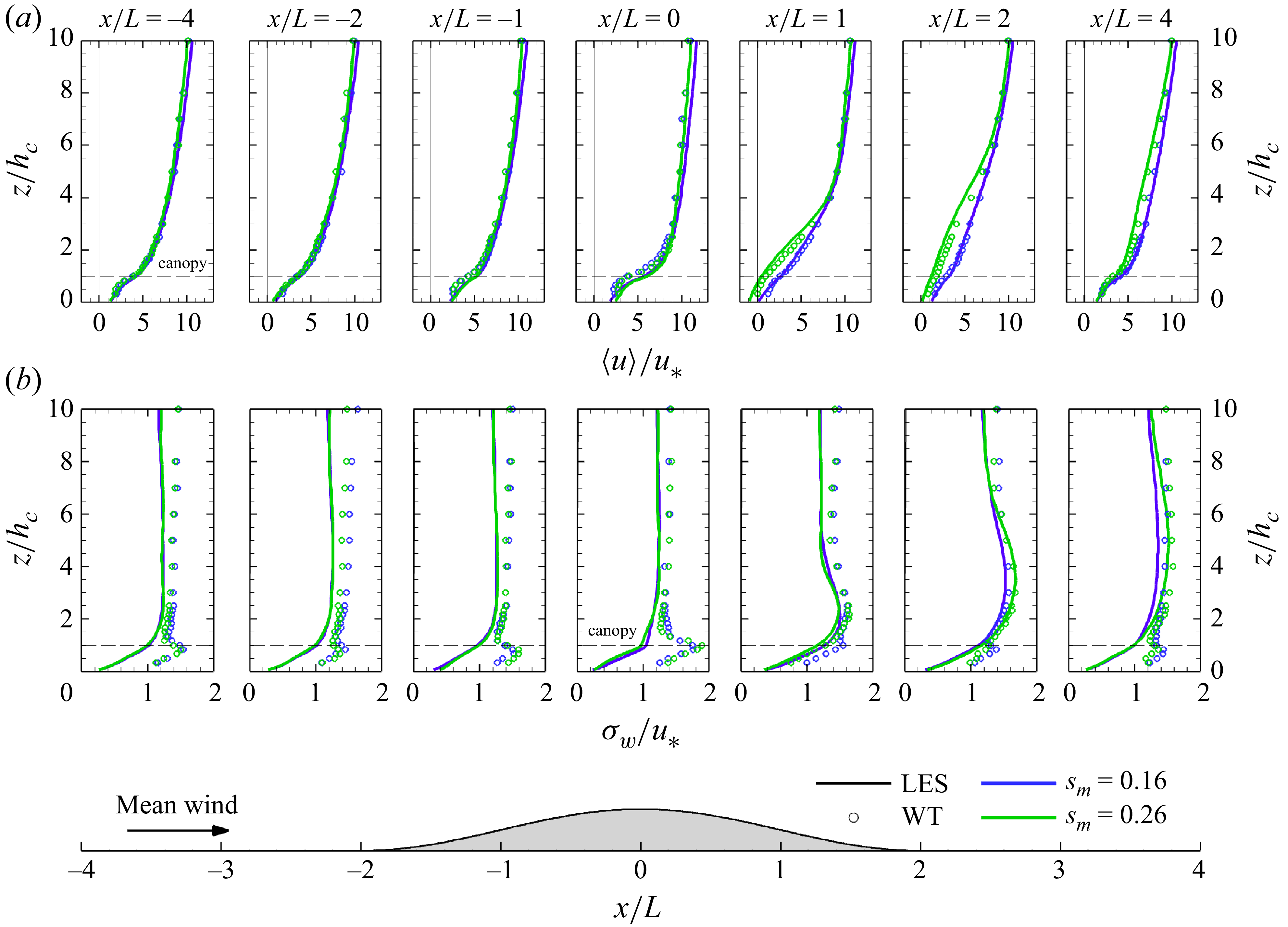

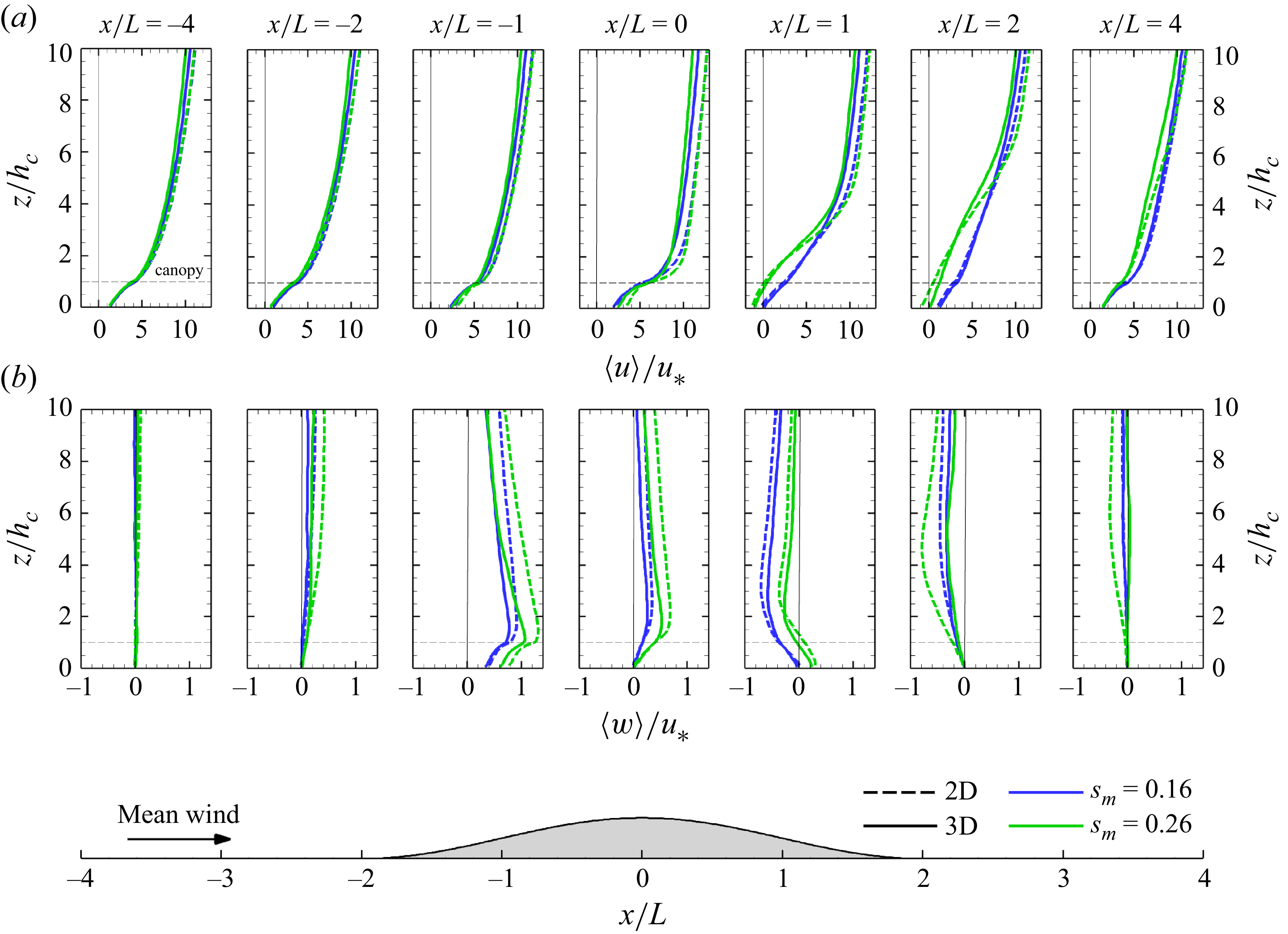

Figure 5. A comparison of WT observed (symbols) and numerically simulated (lines) vertical profiles of average streamwise velocity,

![]() $u$

(a), and vertical velocity standard deviation,

$u$

(a), and vertical velocity standard deviation,

![]() $\sigma _w$

(b), at hill centreline over axisymmetric hills normalized by the friction velocity

$\sigma _w$

(b), at hill centreline over axisymmetric hills normalized by the friction velocity

![]() $u_*$

. Blue colours reflect results for the case with

$u_*$

. Blue colours reflect results for the case with

![]() $s_m =$

0.16, and green colours reflect results for the case with a slope

$s_m =$

0.16, and green colours reflect results for the case with a slope

![]() $s_m =$

0.26; for the LES the data are from 3D–0.16 and 3D–0.26, respectively. The mean flow direction in these figures is from left to right (in the

$s_m =$

0.26; for the LES the data are from 3D–0.16 and 3D–0.26, respectively. The mean flow direction in these figures is from left to right (in the

![]() $+x$

direction). In these figures, we are using a coordinate system that is aligned with (and perpendicular to) the flat terrain surrounding the hill, so positive

$+x$

direction). In these figures, we are using a coordinate system that is aligned with (and perpendicular to) the flat terrain surrounding the hill, so positive

![]() $u$

is in the

$u$

is in the

![]() $+x$

direction, and positive

$+x$

direction, and positive

![]() $w$

is upward.

$w$

is upward.

5. Comparison with WT measurements

5.1. Flow fields

For the 3D–hill cases, vertical profiles of mean wind speed from the LES agree quite well with the WT observed profiles (figure 5). Minor differences can be seen at

![]() $x/L = -1$

and

$x/L = -1$

and

![]() $x/L = 0$

, i.e. halfway up the hill and at hill-crest, where the LES produces slightly higher wind speeds in the upper canopy. Vertical profiles of the vertical velocity standard deviation (

$x/L = 0$

, i.e. halfway up the hill and at hill-crest, where the LES produces slightly higher wind speeds in the upper canopy. Vertical profiles of the vertical velocity standard deviation (

![]() $\sigma _w = \langle w'^2 \rangle ^{{1}/{2}}$

) reveal larger differences between simulations and observations, but the overall trend of the evolution over the hill match well. The most noticeable difference in

$\sigma _w = \langle w'^2 \rangle ^{{1}/{2}}$

) reveal larger differences between simulations and observations, but the overall trend of the evolution over the hill match well. The most noticeable difference in

![]() $\sigma _w$

occurs inside the canopy. These differences can be attributed to the fact that the WT measurements represent samples at fixed locations within the rod canopy, and hence the measurements sample the wakes that waver horizontally and vertically in the lee of the individual physical canopy elements in response to turbulent motions at scales larger than the canopy element spacing. In contrast, the canopy-resolving LES parametrizes the average influence of all canopy elements within a grid cell and hence do not resolve any individual physical canopy elements or the turbulence comprising their wake. Harman et al. (Reference Harman, Böhm, Finnigan and Hughes2016) demonstrated substantial variability of 80 individual

$\sigma _w$

occurs inside the canopy. These differences can be attributed to the fact that the WT measurements represent samples at fixed locations within the rod canopy, and hence the measurements sample the wakes that waver horizontally and vertically in the lee of the individual physical canopy elements in response to turbulent motions at scales larger than the canopy element spacing. In contrast, the canopy-resolving LES parametrizes the average influence of all canopy elements within a grid cell and hence do not resolve any individual physical canopy elements or the turbulence comprising their wake. Harman et al. (Reference Harman, Böhm, Finnigan and Hughes2016) demonstrated substantial variability of 80 individual

![]() $\sigma _w$

profiles collected within a single interelement volume;

$\sigma _w$

profiles collected within a single interelement volume;

![]() $\sigma _w$

profiles averaged over all 80 profiles largely eliminates the within-canopy

$\sigma _w$

profiles averaged over all 80 profiles largely eliminates the within-canopy

![]() $\sigma _w$

peaks, thereby appearing more like those produced by the LES. Harman & Finnigan (Reference Harman and Finnigan2018) conducted similar sampling of 16 locations surrounding a single peg of the current canopy at

$\sigma _w$

peaks, thereby appearing more like those produced by the LES. Harman & Finnigan (Reference Harman and Finnigan2018) conducted similar sampling of 16 locations surrounding a single peg of the current canopy at

![]() $x/L = -4$

; Appendix A shows that observed

$x/L = -4$

; Appendix A shows that observed

![]() $\sigma _w/u_*$

averaged over these 16 locations still peaks in the upper canopy, but the peak is clearly reduced compared with the single-point statistics presented in figure 5 and is more like that in the LES. Therefore, if the WT measurements were to have collected vertical profiles throughout the entire inter-rod volume, notably better agreement would be expected for

$\sigma _w/u_*$

averaged over these 16 locations still peaks in the upper canopy, but the peak is clearly reduced compared with the single-point statistics presented in figure 5 and is more like that in the LES. Therefore, if the WT measurements were to have collected vertical profiles throughout the entire inter-rod volume, notably better agreement would be expected for

![]() $\sigma _w$

between the WT and the LES. Nevertheless, these comparisons provide substantial evidence that the LES reasonably reproduces the physical simulations.

$\sigma _w$

between the WT and the LES. Nevertheless, these comparisons provide substantial evidence that the LES reasonably reproduces the physical simulations.

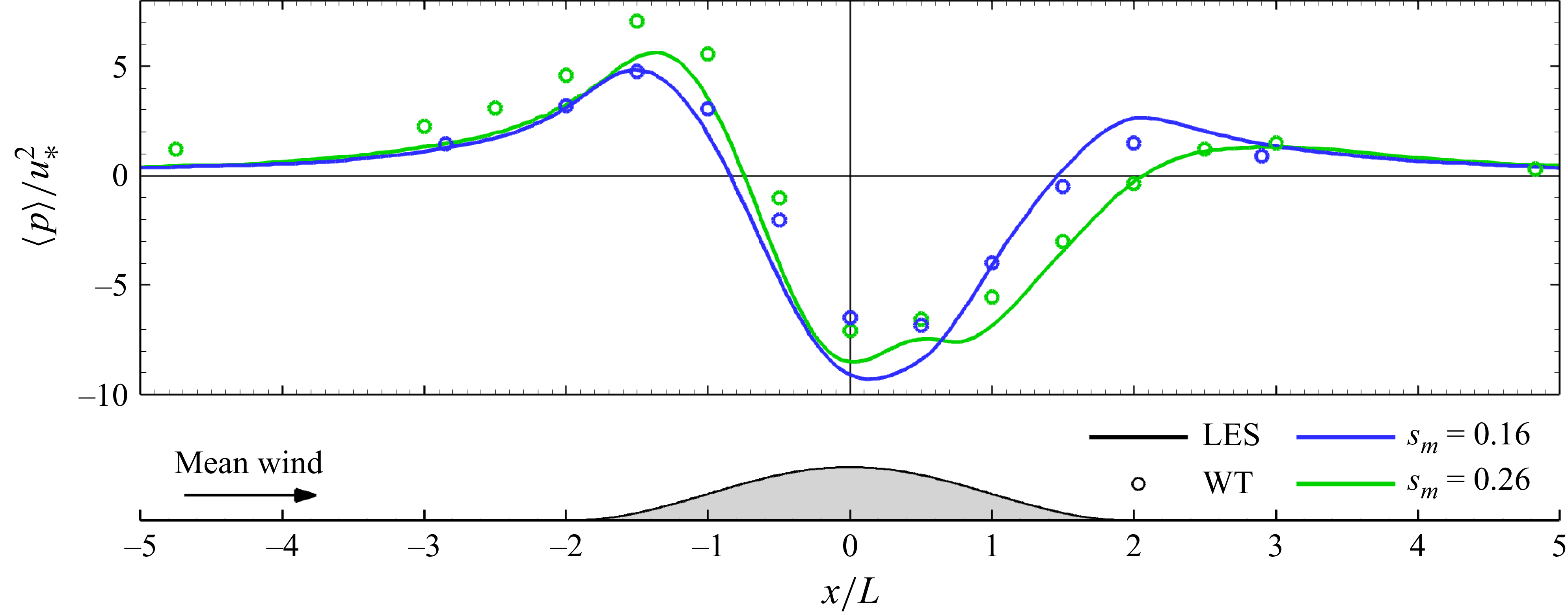

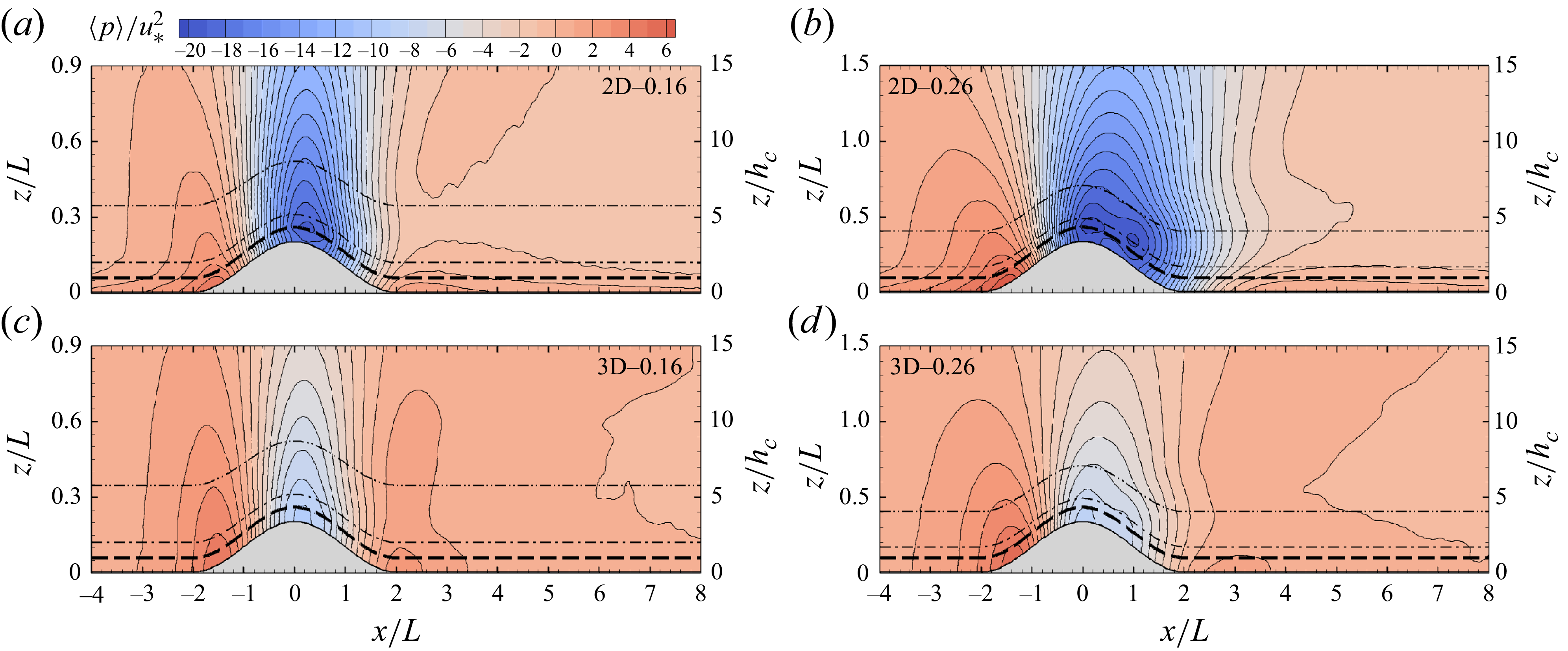

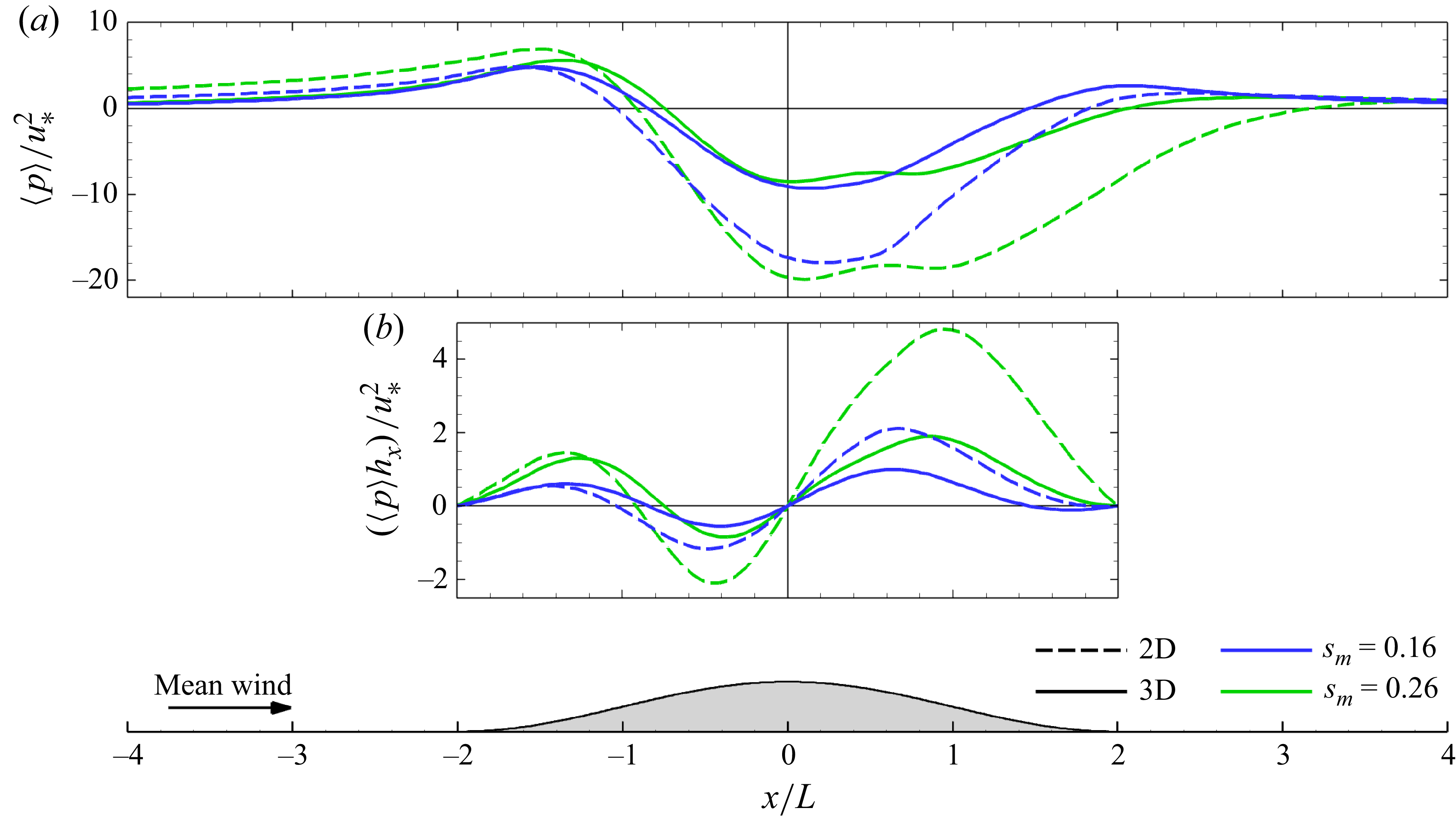

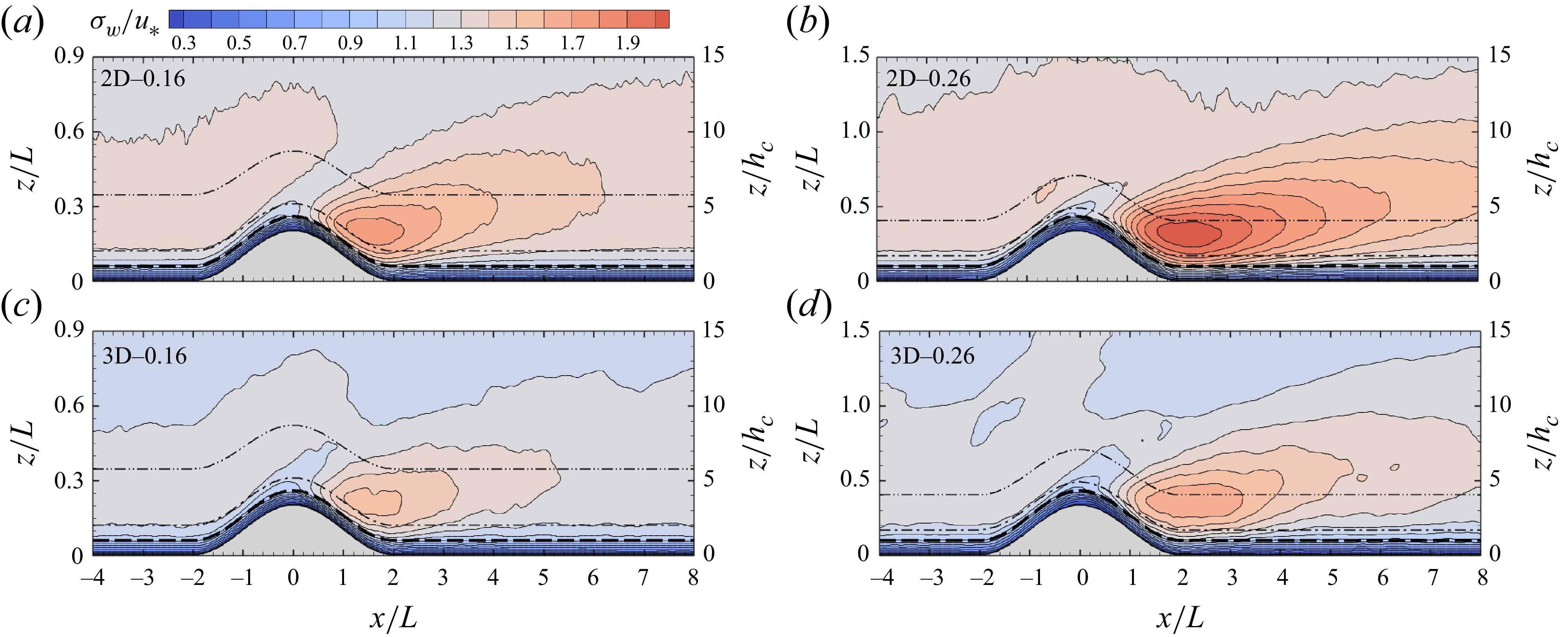

5.2. Pressure