Euesperides, on the outskirts of the modern city of Benghazi, was probably founded before 600 BCFootnote 1 following the establishment of CyreneFootnote 2 and was eventually abandoned around 250 BC when the Ptolemies regained control of Cyrenaica.Footnote 3 The population of Euesperides was a mix of people of different origins and from diverse cultural backgrounds, which constantly changed during the various phases of the city's life due to the influx of new settlers following political and military developments in the city itself, or in the wider region of Cyrenaica and the Greek world.Footnote 4

The excavations conducted at Euesperides between 1999 and 2007 under the auspices of the Society for Libyan Studies, London, and the Department of Antiquities, Libya, and jointly directed by Paul Bennett and Andrew Wilson, brought to light several private houses and a building complex, industrial areas related to purple dye production and part of the city's fortification wall. Among the finds was a highly significant body of local, regional and imported pottery (from the Greek and Punic world, Cyprus, Italy and elsewhere). Over 15,000 sherds and complete pots have been recorded in the project's database, ranging chronologically between the end of the seventh and the mid-third century BC, representing all the different phases of the city's life. Furthermore, this is high-quality pottery data as significant amounts of it came from well-stratified and securely-dated domestic assemblages, so far missing from elsewhere in Cyrenaica. With the exception of Berenice, the published pottery of pre-Roman Cyrenaica comes primarily from sanctuaries, cemeteries and, occasionally, from public buildings.

In order to understand the pottery diversity encountered at Euesperides, one should take into consideration the nature and the development of this Greek settlement. It was a natural harbour with access to the Mediterranean Sea and, possibly, a ‘contact zone’Footnote 5 between the hinterland and the coast.Footnote 6 Euesperides was strategically positioned for protection, exchange and trade, and could have acted as a gateway for produce from regional settlement ‘clusters’ of Greek and Libyan origin (see Figures 1 and 2). Furthermore, standing geographically at the margins of the Maghreb (Shaw Reference Shaw2003, 98–99) and at a vital crossroads in ancient Mediterranean maritime and land routes linking the Greek, Punic and Italian worlds, the city may have attracted merchants who circulated within the western and the eastern Mediterranean spheres of exchange, as the wide range and substantial quantity of imported pottery from Cyrenaica, Greece, the Aegean, Cyprus, Italy, Sicily and the Punic territories indicateFootnote 7. Furthermore, this pluralism could be partly explained by the different needs of people of various origins settling in the city, their fashions and trends. The population diversity and mobility combined with a considerable volume of trade demonstrates that the Greek settlement of Euesperides developed with both an eastern and western character, reflected in the imports from the site.

Figure 1. Map of the Mediterranean basin showing Greek and Punic sites in Cyrenaica and Tripolitania (©Creative Commons Attribution; digital editing V. Stasinaki).

Figure 2. Map of the region of Benghazi showing the location of ancient Euesperides (after Goodchild 1952, 211 fig. 2; digital editing V. Stasinaki).

The Euesperides archaeological project in the 2000s developed a fresh and innovative approach to the study of pottery from the site, built upon the total quantification of the coarse, fine wares and transport amphorae to shed new light on issues related to trade and ultimately the economy of ancient Euesperides. This approach differed from previous qualitative methods where the study and publication of pre-Roman pottery had been based on a selection of material removed from its original context – methods used at previous projects at Euesperides and in most other Greek sites in Cyrenaica, North Africa and elsewhere in the Mediterranean. Pottery quantification, although common on several Prehistoric and Roman sites already from the 1970s (Peacock Reference Peacock1977), and used for the Hellenistic and Roman coarse and fine ware studies from Berenice, the successor city of Euesperides, by Riley (Reference Riley and Lloyd1979) and Kenrick (Reference Kenrick1985) respectively, was applied for the first time to all pottery groups on a Greek site. Hence, pottery quantification became an important and integral part of the project, and was materialised through:

• systematic and meticulous archaeological fieldwork for several seasons at Euesperides;

• generous funding from the Society for Libyan Studies and the British Academy which allowed three pottery experts to work on the different classes of pottery, namely coarse, fine wares and transport amphorae, throughout the duration of the project.

Consequently, a comparative approach to pottery fabrics and inter-class applications of fabric analysis were instrumental: the identification of Punic and Corinthian coarse wares through comparisons to the fabrics of transport amphorae or of the local and regional fine pottery with the contribution of coarse ware fabrics provide tangible examples of the advantages of this methodology. In addition, the pottery study at Euesperides has been supplemented by a targeted programme of scientific clay analysis to ascertain provenance. Coarse wares (Swift Reference Swift2005) and trade amphorae (Göransson Reference Göransson2007) from the site have already been analyzed petrographically and several groups have been distinguished, both imported and regional, and technological characteristics have been defined. Extending the scientific analysis to certain classes of fine wares also has great potential.Footnote 8 It could enrich our knowledge about the Cyrenaican manufacture and glazing technologies of this class as well as about the production centres of a wide range of imports recorded from the site. Consequently, such a study could contribute to a better understanding of the economic interactions at ancient Euesperides during the different phases of the city's life,Footnote 9 highlight trade networks and patterns and shed light on the city's connectivity with regional economies in Cyrenaica, yet to be defined, and with the wider Mediterranean over time.

The coarse wares

The study of Classical and early Hellenistic coarse pottery from the site comprised the topic of Keith Swift's doctoral thesis submitted at the University of Oxford in 2005. This important work, although unpublished as yet in its totality, has been the first step towards the configuration (identification and characterisation) of local and regional Cyrenaican clay fabrics and their technologies, as published in the last volume of Libyan Studies (Swift Reference Swift2018). Also, Swift thoroughly explored the question of fabrics and functions, indicating that though some local fabrics may have been better suited to some types of containers than others (i.e. Local Ware 1 and 2 for cooking, Local Ware 3 for liquid containers)Footnote 10, and although pottery production at Euesprerides was intended primarily for local consumption, no single local fabric is used exclusively for one function.

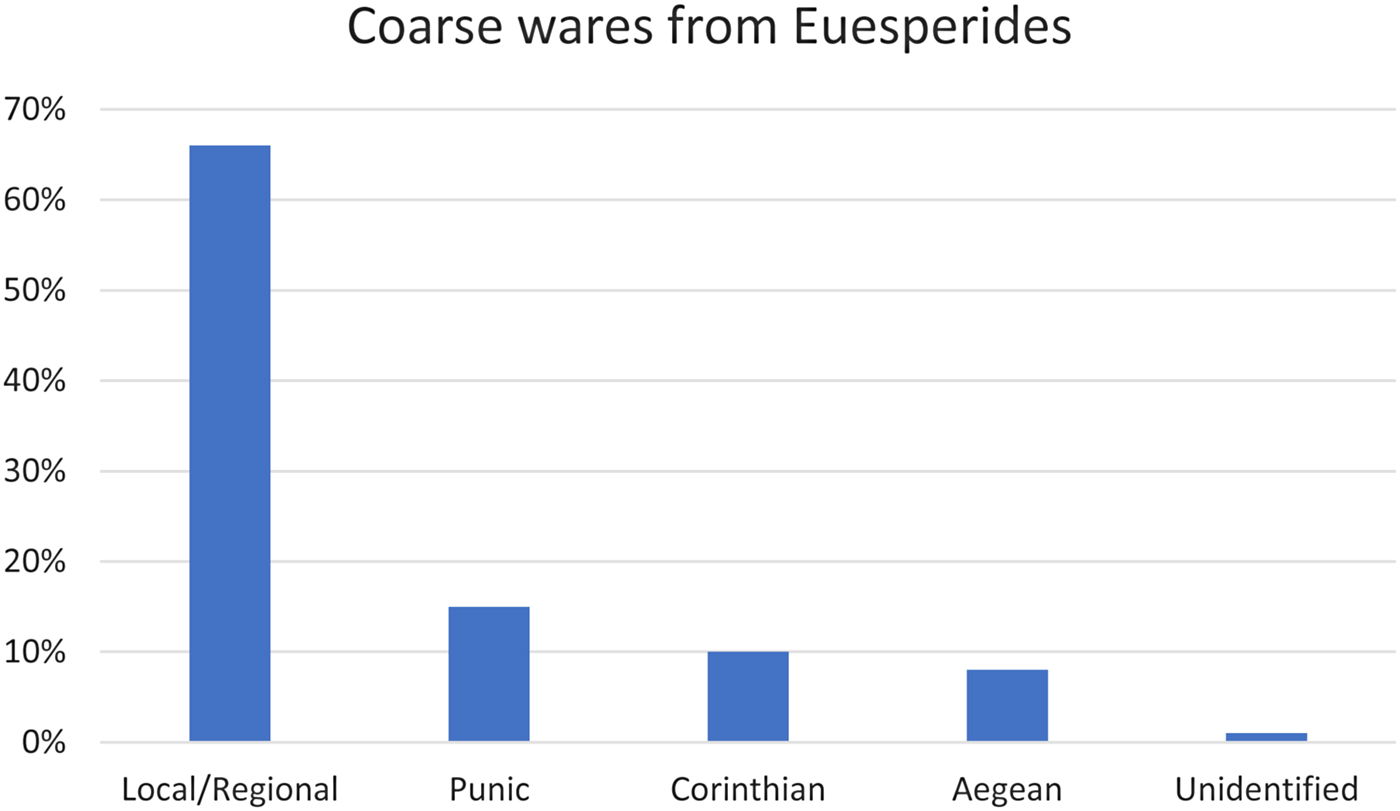

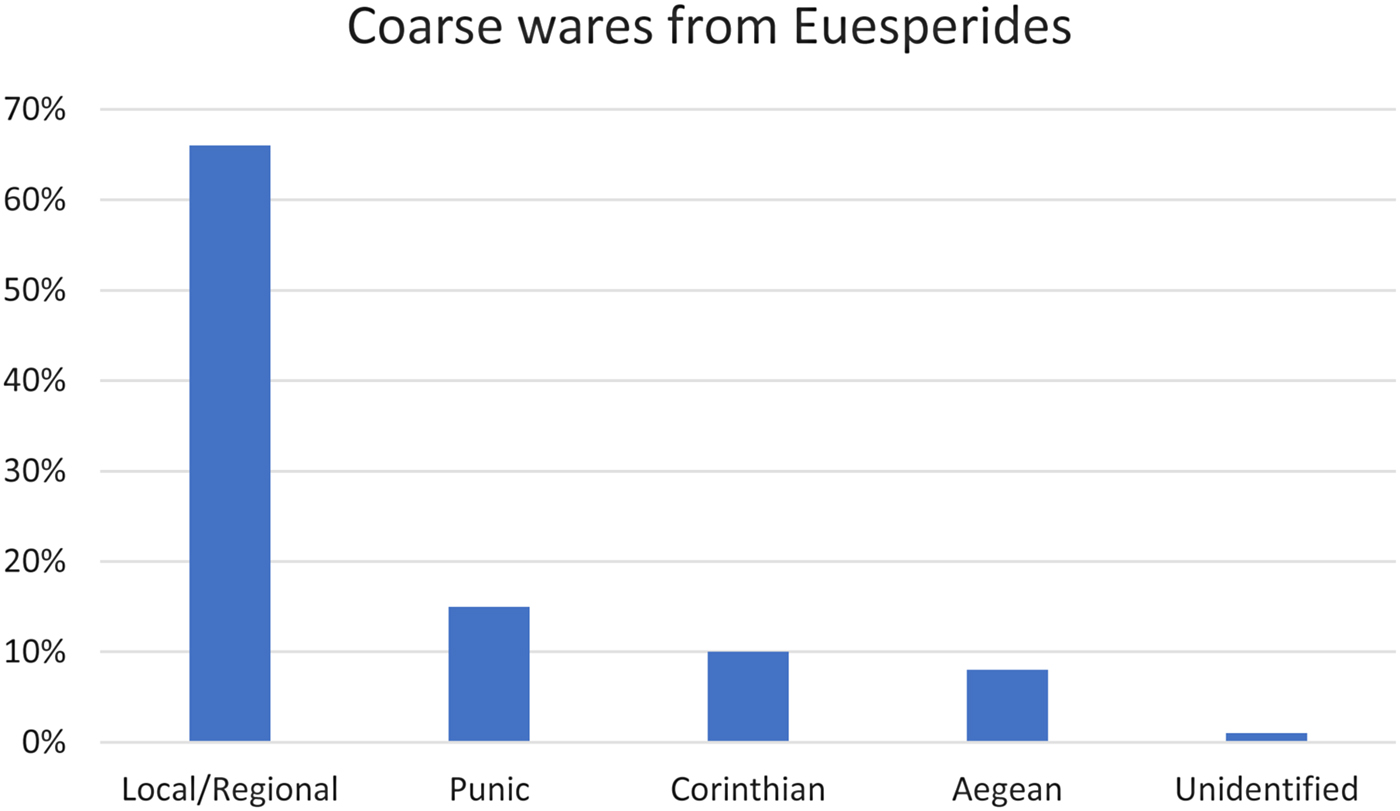

Furthermore, Swift's study demonstrated that substantial quantities of coarse wares were imported at Euesperides, counting for c. 34% of all coarse pottery by count, at least, in the fourth and first half of the third century BC, a result indicating ‘long-distant trade and economic interactions’ (Swift Reference Swift2005, 233) in a regional or extra-regional level. The issue of traded coarse wares in Greek settlements has become popular in scholarship over the last decade, since it is only relatively recently that cooking assemblages, coarse tableware and storage containers from various sites around the Mediterranean have drawn the attention of pottery specialists and the topic has gained ground in contemporary discourses on pre-Roman coarse pottery distribution and consumption (Spataro and Villing Reference Spataro and Villing2015; Dietler Reference Dietler2010). Regarding the provenance of the imported coarse pottery from Euesperides, Swift identified Corinthian (c. 10%), ‘Aegean’ (including Aiginetan cooking wares, c. 8%) and Punic examples (c. 15%) (Swift Reference Swift2005, 232–233). Corinthian imports go beyond specialised vessels, such as mortaria,Footnote 11 sometimes associated with grinding up additives to flavour wines,Footnote 12 and louteria, which have been also found in other Mediterranean sites (e.g. Miletos, Villing Reference Villing and Tsingarida2009, 321–322), and extend to lekanai, bowls and liquid containers (Swift Reference Swift2005, 199).

Regarding Corinthian liquid containers, Swift argues that they were traded to Euesperides because of their compactness and permeability which made them more suitable for ‘long-term liquid storage and transfer’ than those produced in the local fabrics (Swift Reference Swift2005, 199). Furthermore, he suggests that these containers ‘were traded as part of the Corinthian coarse pottery repertoire as a whole or perhaps for their contents, i.e. as containers for commodities rather than as commodities in their own right’. Related evidence from Corinth itself and identification of similar imports on other sites could shed light on the question of why and how these containers reached the settlements overseas and whether their high demand at Euesperides, and possibly elsewhere, is representative of a wider trend in the late Classical and early Hellenistic period in the eastern Mediterranean – related to the focus of Corinthian pottery production towards an export market (Swift Reference Swift2005, 199) or identities and consumption habits of the inhabitants of Euesperides. For the question of internal distribution of Corinthian coarse wares in the various assemblages at Euesperides itself, which may help explain their circulation in the social strata during different phases of the city's life, we must look ahead to the much awaited, final publication of the project (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Relative proportions of coarse wares (RHBS) at Euesperides (end of fifth to the middle of the third century BC) (after Swift Reference Swift2005, 233. Wilson Reference Wilson, Prag and Crawley Quinn2013, 140, fig. 5.10).

Among imported coarse pottery, Swift also identified a group named ‘Aegean’ cooking ware, including chytrai and lopades, of which a considerable number seems to be of Aiginetan manufacture. This is not surprising taking into consideration that Aigina was a noted source and a major exporter of cooking pots around the Mediterranean in Classical antiquity.Footnote 13 Evidence from the Athenian Agora demonstrates that Aiginetan chytrai and lopades were consumed in Athens in considerable quantities from the last quarter of the sixth to the end of the fifth century BC; it has been suggested that a number of them may have been exchanged for Attic pottery and then traded in the west.Footnote 14 Swift favours the hypothesis that Aiginetan pottery could have been co-distributed from the Saronic Gulf together with Corinthian coarse and Attic fine wares to Cyrenaica, at least in the fourth century BC (Swift Reference Swift2005, 201). This preference for specialized, imported cooking wares seems to be a common feature in Greek and non-Greek settlements from at least the Early Iron Age onwards (i.e. Cycladic cooking pots at Knossos,Footnote 15 East Greek cooking wares at Ashkelon,Footnote 16 etc.) and persists beyond antiquity to modern times (i.e. the island of Siphnos specialized in cooking wares, which were exported to other islandsFootnote 17).

Punic coarse wares have been also identified at Euesperides following comparisons with Punic amphora clay fabrics, and constitute the largest imported group, at 11–15% of the assemblage. This figure, which complements the picture given by the amphorae from the site, has been suggested to indicate ‘plenty of shipping contact across the Gulf of Syrte’ (Quinn Reference Quinn, Dowler and Galvin2011; Wilson Reference Wilson, Prag and Crawley Quinn2013). However, the possibility that these containers did not travel only as part-cargoes with other commodities, but reflects inter-regional commerce or even movement of people (i.e. presence of Punic traders at EuesperidesFootnote 18) between Punic regions (Tripolitania and/or the wider Carthaginian territory) and Cyrenaica is worth exploring. This hypothesis can also be supported by the wide range of Punic containers, besides transport amphorae, included in the assemblages at Euesperides: cooking and table ware, such as lopades, chytrai, lekanai, bowls, jugs and table amphorae, primarily those dated between the second quarter of the fourth and the first quarter of the third century BC. These are classified into two different types according to their clay consistency, which have also been found at Sabratha and Carthage (Quinn Reference Quinn, Dowler and Galvin2011; Wilson Reference Wilson, Prag and Crawley Quinn2013). In common with cooking wares from other areas of the Mediterranean (i.e. southern France where cooking pots follow Greek forms),Footnote 19 the Punic examples from Euesperides follow their Aiginetan counterparts.Footnote 20 It has been recognised that this is an indication that Aiginetan cooking pots were also traded to the Punic world,Footnote 21 implying interconnected trade flows and cultural borrowing between the eastern Mediterranean and Punic North Africa, although further research on other sites is required in order to develop this hypothesis further.

The transport amphorae

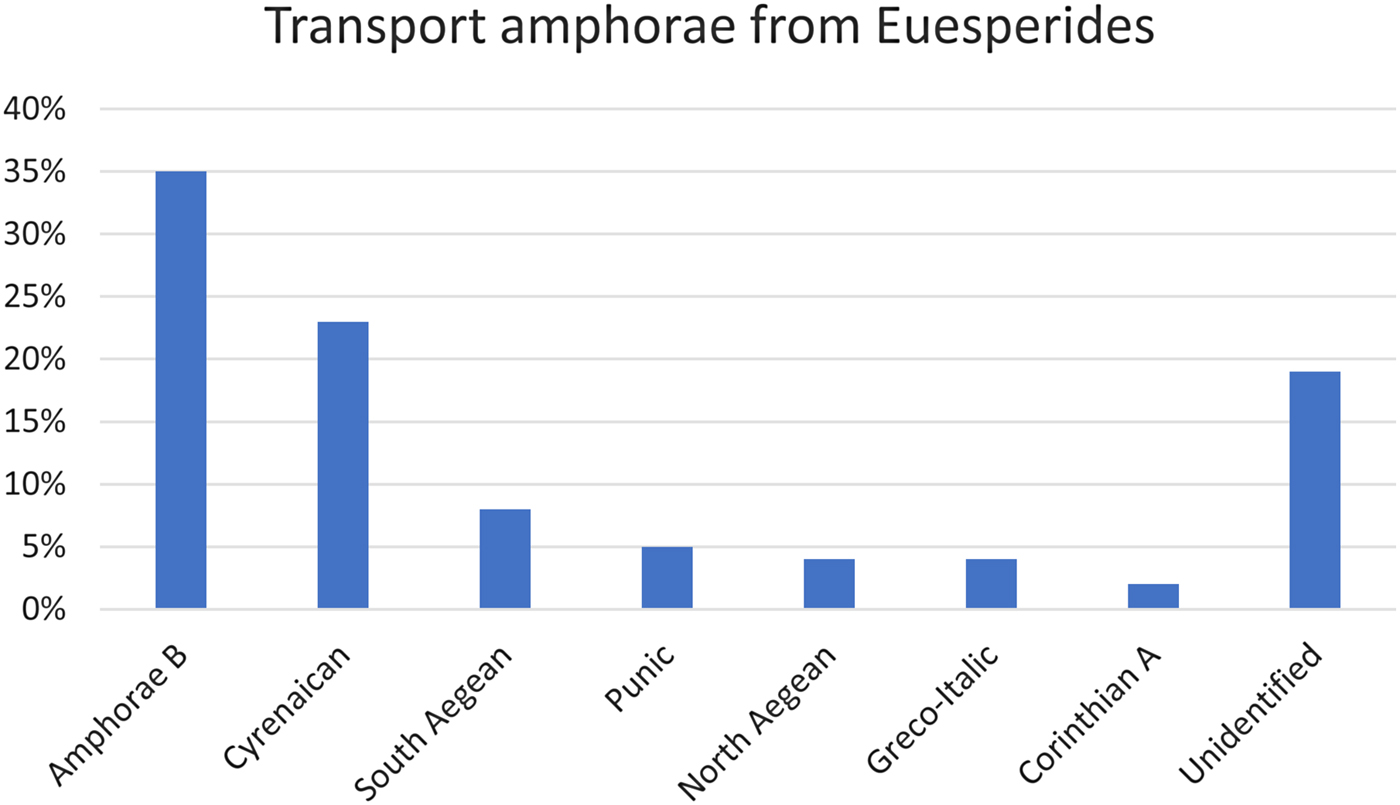

Regarding transport amphorae, Kristian Göransson quantified and studied the late Classical and early Hellenistic amphorae for his doctoral thesis published in 2007. His analysis demonstrated that imports outnumber Cyrenaican examples, counting for c. 77% by total sherd count (RBHS), while the Cyrenaican amphorae reach approximately 23%Footnote 22 and are classified in four groups but cannot as yet be ascribed to any particular cities or workshops in the region (Figure 4). Their presence at Euesperides suggests the local consumption of their contents (olive-oil, wine, etc.) or/and the possible role of the port of Euesperides in the inter-regional trade network for the redistribution of amphorae-borne commodities (i.e. silphium derivatives, etc.) further west, i.e. in Tripolitania (perhaps Sabratha) and Carthage (Göransson Reference Göransson2007, 217 and note 157, 219). The Cyrenaican examples adopt the forms of Greco-Italic and Chian amphorae, while the similarity of certain groups with the amphorae types 1 and 2 from Berenice has also been noted.Footnote 23 Furthermore, the examples which were locally-made at Euesperides belong to the so-called ‘Corinthian B’ type and form a small group.Footnote 24

Figure 4. Rims of the Cyrenaican Amphora 4 class from Euesperides (photograph by K. Göransson).

The majority of the imported amphorae are of the so-called Corinthian B type (c. 48–55%) produced in various centres around the Mediterranean (i.e. Corcyra, Sicily, the Adriatic, etc.), but, besides a few local examples, have not been provenanced at Euesperides.Footnote 25 Göransson assumes that most of the amphorae B from the site come from Corcyra and suggests either a direct link between the island and Euesperides or their re-distribution via Sicily where they are commonly found.Footnote 26 Recent petrographic studies have attributed amphorae B from Gela in Sicily to the Corcyrean Kerameikos (Finocchiaro et al. Reference Finocchiaro, Barone, P. Mazzoleni and Spagnolo2018), but as long as the provenance of the total assemblage of amphorae B from Euesperides is not defined, the representation of other production centres besides Corcyra cannot be excluded. Also, the fact that the clay fabric of a group of fine wares from Euesperides bears similarities to amphora B fabrics reinforces the hypothesis of commercial networks linking Euesperides with the manufacturing region of this class, which could have reached the city together with the goods transported in the amphorae of the same provenance, either directly or via re-distribution hubs (i.e. in Sicily) or even through both routes.Footnote 27 Based on the large amount of amphorae B at Sabratha, Göransson sees Euesperides as ‘an entrepôt for onward trade in Corcyrean (and perhaps also Corinthian) products with the Punic cities in Tripolitania’ (Göransson Reference Göransson2007, 224). Further research on the provenance of amphorae B from the wider Carthaginian territoryFootnote 28 may indicate maritime networks between this region, western Cyrenaica and Tripolitania and, possibly, with Sicily and the Adriatic, and contribute to the assessment of the role of Corinth, where a significant amount of amphorae B has been also found, as a transhipment centre in the fourth and first half of the third century BC.Footnote 29

Moreover, there are numerous early Hellenistic wine amphorae from the south-western Aegean (c. 7-10%), namely from Chian, Samian, Knidian and Koan, workshops, while Rhodes is barely represented (Göransson Reference Göransson2007, 146–166; Wilson Reference Wilson, Prag and Crawley Quinn2013, 133). The north Aegean amphorae (primarily Thasian and Mendean) are less common (c. 1–3%) (Göransson Reference Göransson2007, 136–145; Wilson Reference Wilson, Prag and Crawley Quinn2013, 133). Other imports include a meagre quantity of Corinthian A (Göransson Reference Göransson2007, 82–83) and Cypriot amphorae (Göransson Reference Göransson2007, 170–173). For the Aegean amphorae found at Euesperides, Piraeus as a major port where ships ‘bound to Cyrenaica took on board Aegean amphorae with their staple commodities’ has been suggested as the most likely transhipping centre (Göransson Reference Göransson2007, 229). This hypothesis is reinforced by the large quantities of Attic fine wares and their persistence at Euesperides until the late Classical and Early Hellenistic period, which hints at established trade between Athens and Euesperides.Footnote 30 Other possible routes to western Cyrenaica via the southern Peloponnese and Crete (Phalasarna) have been suggested, while a commercial route via Corinth is also likely taking into consideration not only the importance of its port, but also the amount of Corinthian pottery (fine wares, coarse wares and, to a lesser extent, trade amphorae Corinthian A) imported at Euesperides during this time (Göransson Reference Göransson2007, 228). In his discussion, Göransson claims that ‘some or all of the suggested routes may have been used, perhaps simultaneously, perhaps in varying degrees over time’ (Göransson Reference Göransson2007, 228).

Wine and other goods arrived at Euesperides in modest quantities from southern Italy/Sicily and other places further west. Western imports to the city include Greco-Italic wine amphorae produced in southern Italy and Sicily (4%) (Göransson Reference Göransson2007, 115–134. Also Göransson Reference Göransson and Olcese2013) which have not yet been assigned to specific production centres,Footnote 31 Massaliote amphorae (c. 3% of all quantified amphorae RBH)Footnote 32 as well as a single amphora sherd from Ibiza.Footnote 33 Transhipping from Sicily has been regarded as the most likely route to Euesperides for these amphorae and their staple commodities (Göransson Reference Göransson2007, 226). The Greco-Italic and amphorae B are frequently found at the same sites, which is also true for Cyrenaica (i.e. Euesperides), Tripolitania (i.e. Sabratha) and the Carthaginian territory (i.e. the commercial harbour at Carthage, but also elsewhere), and this may imply a connection between Sicily and North Africa in the trade of commodities transported in amphorae B (i.e. Corcyrean wine and other goods from the various production centres of these amphorae) (Figure 5).Footnote 34

Figure 5. Relative proportions of transport amphorae (RHB) from fully quantified contexts at Euesperides (325–250 BC) (after Göransson Reference Göransson2007, 191, fig. 42).

Italian black-gloss (Campana A and B) and Gnathian tableware of the last quarter of the fourth and first half of the third century BC, which circulated widely in the western Mediterranean, have also been found at EuesperidesFootnote 35 and may have accompanied the goods transported in the Greco-Italic amphorae to Cyrenaica.

Looking beyond the occurrence of the Greco-Italic type of amphorae at Euesperides, Göransson identified, for the first time, copies of the Greco-Italic wine amphora shape in Punic North Africa (Göransson Reference Göransson2007, 188), a very significant indication for commercial and cultural interactions between the Greek and Punic worlds (Wilson Reference Wilson, Prag and Crawley Quinn2013, 136–137) which is reinforced by the Punic adoption of Aiginetan cooking ware forms as mentioned above.

The proximity of Cyrenaica to the Punic world does not seem to have encouraged significant trade flows earlier than the Hellenistic period when the rivalry between the two areas was eventually settled (Göransson Reference Göransson2007, 221). Although Punic coarse pottery has been attested at Euesperides in the fifth century BC (see above), it is only from the last quarter of the fourth century onwards that Punic amphorae and jars appear in the archaeological record of the city in considerable quantities, reaching a ratio of 5–6% of the total amount of amphora sherds.Footnote 36 Punic amphorae of probably Tunisian or Tripolitanian origin belong to the type with a trumpet-shaped mouth and an out-flared rim for wine or olive oil,Footnote 37 while jars of the so-called torpedo type (18% of the Punic amphorae at the site) serving for the transport of processed fish and/or meat have been attributed to Tunisian manufacture implying imports from the Carthaginian territory in the early Hellenistic period.Footnote 38

Lastly, the evidence from the imported amphorae at Euesperides ‘found in domestic contexts or as surface finds from the urban survey’ indicates that some of the commodities were primarily ‘destined for consumption in the city’ (Göransson Reference Göransson2007, 220). It is however not unlikely that others may have been intended for inter/intra-regional trade with other cities in Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and the Carthaginian territory. In addition, several of the imported transport amphorae at Euesperides come from regions with a reputation for high quality wines, such as Chios, Thasos, Mende, some parts of southern Italy, etc., or of wines with aging potential (i.e. from Corcyra) implying local consumption habits and domestic affordability.

The diverse and wide range of amphorae from Euesperides reflects the nature of trade in western Cyrenaica and, also partly, along the north African coast until the middle of the third century BC. Further research and comparison between the land evidence and the cargoes found in ancient shipwrecks along the North African coast and in the western Mediterranean may improve our knowledge of maritime trade networks. At Euesperides, the picture from the amphorae (and, also, from other classes of pottery) may point predominantly to maritime cabotage. This was a limited-scale enterprise during which the goods may have been acquired in stages from port to port along the way or, more likely, at transhipping centres from where commodities were redistributed. In both cases, this operation may have been carried out by merchants of different origins moving along the Mediterranean carrying ‘heterogeneous, in terms of origin cargo’ but of commodities targeted’ toward regional patterns of demand’.Footnote 39 Although the accessibility of Euesperides’ harbour to large deep-sea consignment ships has not been as yet been assessed, the location of the city along a series of coastal lagoons may have facilitated maritime cabotage services with small merchant vessels to and from the city to other ports along the North African coast.

The fine wares

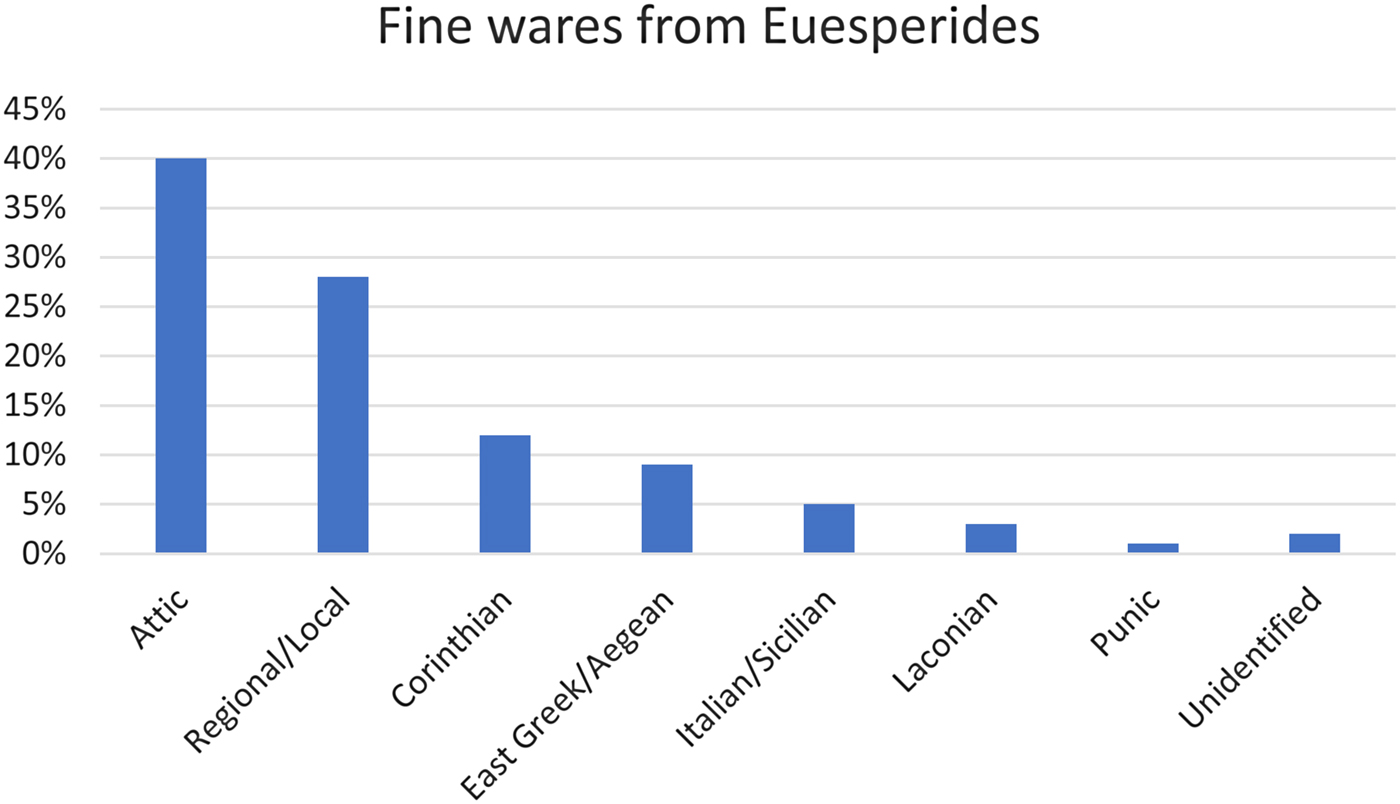

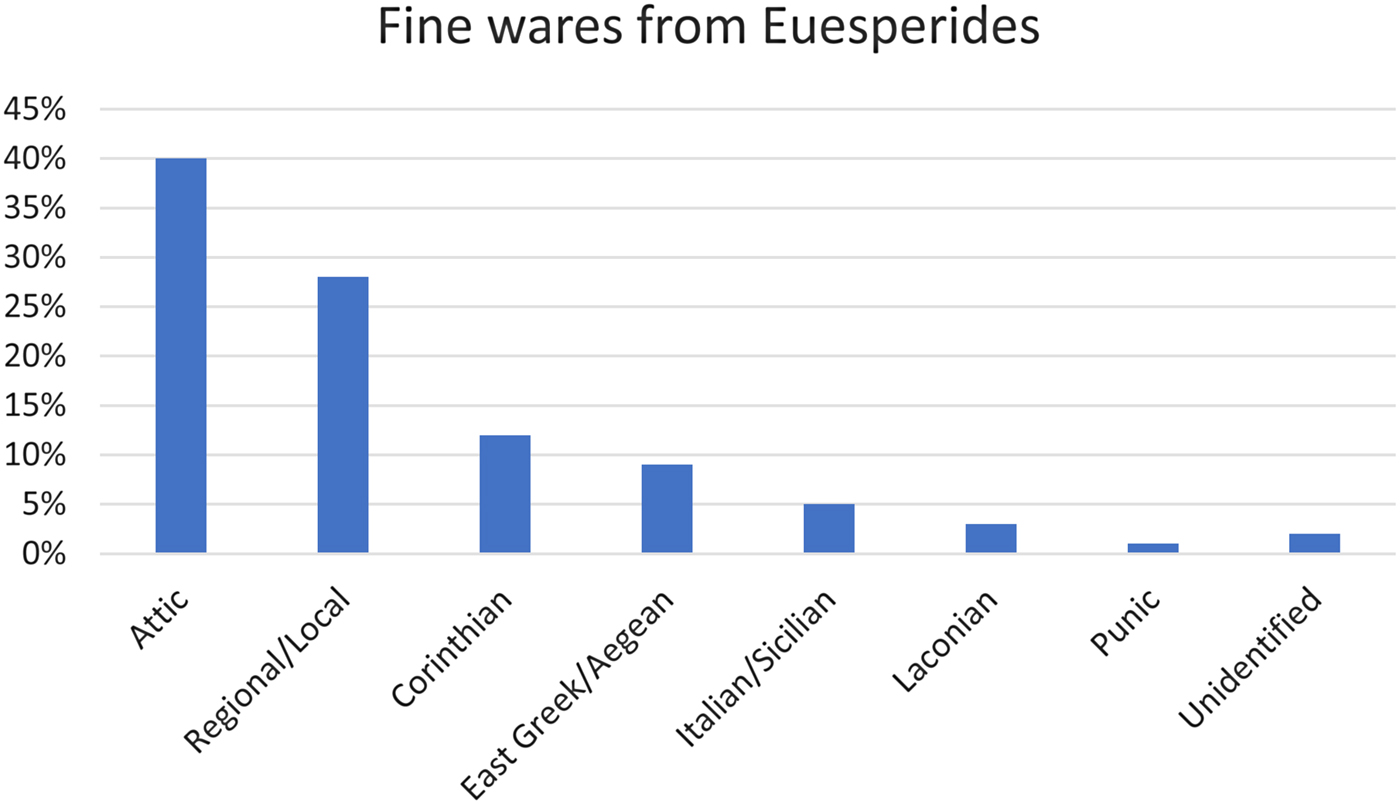

The analysis of the quantified fine wares from Euesperides is a work in progress. Yet their study has so far shown that Euesperides heavily relied on imported fine pottery in varying quantities and from different productions centres, predominantly from Athens (c. 40% of RSHB) (Zimi, Reference Zimiforthcoming c.), but also from Corinth (c. 12%), Laconia (c. 3%) (Zimi, Reference Zimiforthcoming b), East Greece and the Aegean (c. 9%), S. Italy and Sicily (c. 5% including early Campana A, B, C and Gnathia) and the Punic world (c. 1%), to meet its needs (Figures 6 and 7). This picture of imports outnumbering the local/regional examples remained unchanged throughout the city's life despite an increasingly vigorous regional and local fine ware industry which often emulated Attic (Zimi, Reference Zimiforthcoming c.) and Corinthian pottery. Furthermore, among the 7,000 fragments and intact pots recorded, the majority are black-glazed,Footnote 40 several of which are inscribed with graffiti (primarily in Greek, but there are also a few with Punic signs), while painted pottery, including black-figure and red-figure, is found on a much smaller scale, accounting for c. 5% of the total fine pottery assemblage.

Figure 6. Relative proportions of fine wares (RHBS) at Euesperides (end of seventh to the middle of the third century BC).

Figure 7. Imported fine wares from Euesperides. Above: a) rim of a Laconian krater (mid-6th c. BC), b) a fragmentary Attic red-figure askos, decorated with a wreath (second half of the 5th c. BC), c) a fragmentary red-figure askos with animals (5th c. BC), Below: d) Corinthian echinus bowl (end of 4th-early 3rd c. BC), e) south Italian one-handler (4th c. BC) f) partly preserved rim from the lid of a Gnathian-ware pyxis (first half of the 3rd c. BC) [photographs by Eleni Zimi, drawing by D. Hopkins].

Most fine ceramics found at Euesperides are drinking containers (variants of cups, skyphoi, bolsal cups and kylikes) for wine consumption during the symposium, or at any stage of a banquet. From the second half of the fourth century and until the abandonment of the site, however, a gradually increasing quantity of bowls with in-turned (echinus bowl) and out-turned rims, primarily Attic, but also southern Italian, and of local/regional manufacture, has been observed.

East Greek bowls, Laconian and Laconianising black-glazed kraters are common classes of Archaic fine pottery at Euesperides, also supplemented, by Corinthian aryballoi and, later, by Attic black-figure skyphoi. As far as Attic pottery is concerned, it reached the city in the first half of the sixth century and circulated for three centuries until the abandonment of the site. Its wide distribution across the site implies that access to Attic imports was not at any time socially restricted (Zimi, Reference Zimiforthcoming c). There seems to be no preference for figured drinking vessels among the imports at Euesperides, at least from the second half of the fifth century onwards. Drinking from an Attic plain black-glazed cup seems to have been favouredFootnote 41 due to its manufacture and gloss quality, probably creating a ‘sensuous’ drinking experience,Footnote 42 and fashion trends. In the fifth century, Attic black-glazed pots include drinking vessels (i.e. Attic A type skyphoi, kylikes, bolsal cups and a few ‘Castulo cups’), mixing and liquid containers (red-figure kraters, pelikai, hydriai, oinochoai), and a small number of trinket and toiletry vessels (lidded lekanides with ribbon handles, askoi, squat lekythoi).Footnote 43

In the fourth century BC, a significant volume of Attic fine ware seems to have reached Euesperides fulfilling a wider range of functions. The increase of the toilet and trinket containers may indicate, together with customers’ preferences, the significant scale of that market in the fourth century BC. Red-figure lekanides are commonly decorated with animals or women's scenes on the lid. One further trend relates to a significant increase in black-glazed small bowls, some of which may have had an intended use as serving vessels for herbs and spices or other types of food, in bowls with out-turned rims, Lykynic lekanides and salt-cellars, as well as in dispensers for special liquids (gutti/askoi, ‘feeders/fillers’, etc.); shallow red-figure and black-glazed askoi with a dome-shaped top and squat lekythoi are also represented. A similar pattern of Attic imports emerges from others site in Cyrenaica (Zimi, Reference Zimiforthcoming c). Furthermore, the appropriation of the Attic small bowl with in-curved or out-turned rim observed at Euesperides, seems to have been shared throughout the western Mediterranean since the first half of the fourth century BC (Zimi, Reference Zimiforthcoming c).

Regarding Corinthian pottery, although it reached Euesperides from an early date, as fragmentary aryballoi of the end of the seventh or early sixth century BC attest, it was not until the late fifth and fourth centuries BC that it became prolific in domestic and funerary contexts.Footnote 44 It has been estimated that approximately 15% of all fine ware pottery is Corinthian, placing Corinth second among the sources of imports at Euesperides, the first being Athens. This figure is close to that of the Corinthian coarse pottery from the site, which comprises approximately 10% of total coarse ware imports (Swift Reference Swift2005, 191). Furthermore, genuinely Corinthian transport amphorae, namely those of Corinthian A type, are also present between 400 and 250 BC, reaching 2% of total amphora imports (Göransson Reference Göransson2007, 83–88). The most popular type of Corinthian fine wares seems to have been the so-called ‘Conventionalizing’. This category, which is rarely found or recorded in settlements around the Mediterranean,Footnote 45 accounts for nearly 40% of the Corinthian fine wares imported at Euesperides, second only to Corinthian black- glazed and plain wares. The vast majority is concentrated on a specific area of the site (Area P) where a building complex with mosaic floors has been excavated, possibly alluding to the origin and/or the status of its inhabitants, and dates to the Classical period, with the latest examples reaching the last quarter of the fourth century BC. Pyxides and miniature kotylai are the commonest shapes.

As is the case in other regions in the Mediterranean where Greeks established settlements, the wine trade may have played a significant role in the stimulation of fine ware imports,Footnote 46 which together with the Greek identity of the new settlers and the cultural significance of the symposium could, at least partly, justify the predominance of cups and other drinking containers in the archaeological record of Euesperides.

The configuration of the local and regional Cyrenaican clay fabrics of the coarse wares from Euesperides contributed to the identification and classification of their counterparts in fine pottery. Locally produced fine wares are found both in the sebkha and terra rossa fabrics defined by Swift,Footnote 47 including drinking vessels, often emulating Attic and Corinthian cups (skyphoi, bolsal cups and kotylai), liquid containers (amphorae and jugs) and lamps. Further research and publication of the local fine pottery from other sites in Cyrenaica and, especially from Cyrene, will facilitate the often-challenging distinction between local and regional products among certain classes of fine pottery at Euesperides. Through this process questions related to inter-regional commerce could then be more successfully tackled.

The imports from southern Italy and Sicily, comprising of skyphoi of various types, kraters and bowls with in-turned rim, which date between the end of fifth and the first half of the third century BC reveal possible commercial relations with this part of the world and reinforce the argument for a political link between Euesperides and Sicily (Syracuse) in the late Classical period, which is documented in at least one inscription from the former.Footnote 48

Last but not least, Punic and Aegean fine wares (i.e. black-glazed pots from the island of Thasos) identified in the assemblage have yet to be studied further. Taking into consideration the pottery evidence from Carthage,Footnote 49 it is noteworthy that the pattern emerging during the Middle Punic II.2 (400–300 BC) and the first half of the third century BC presents similarities with that of contemporary Euesperides: amphorae B, Sicilian amphorae at Carthage/Greco-Italic at Euesperides, northern Aegean vessels and Attic black-glazed pots reached both regions. Despite certain localised commercial behaviours, the picture points towards ‘an important trade route leading from the northern Aegean area via Athens/Piraeus, along the southern Italian and Sicilian coasts, down to the North African coast’ recognised in the Carthaginian territoryFootnote 50 and now also observed in western Cyrenaica.

Discussion

The pottery evidence from Euesperides suggests substantial cross-cultural trading contacts with the Greek and the Punic world which could become clearer in the final publication of the Euesperides project when coarse, fine wares and transport amphorae will be treated together within their contexts. Consequently, distribution patterns and the relative ratios of the three categories of pottery over time will emerge. Here it is important to note that Euesperides seems to have been a merchant port and although any direct exchanges between the indigenous semi-nomadic tribes in its immediate hinterland cannot so far be traced archaeologically in the city, literary sources mention indigenous people collecting silphium and providing wool (Göransson Reference Göransson2007, 218–220) implying that these goods together with products supplied by the inhabitants of Euesperides (i.e. purple dye, textiles, etc.)Footnote 51 played a significant role in the development and sustainability of inter-and intra-regional trade. Imported commodities, such as wine, olive oil, processed fish and meat, arrived in the city, primarily, by maritime transport. The mobility of traders, but also the population diversity of Euesperides may have had an impact on the patterns of demand and consumption as well as on the mechanisms of commerce in the city, and yet these remain rather obscure. The fact that the inhabitants of Euesperides heavily relied on imports to cover their pottery needs would have considerable implications for the state of the city's economy and points to a strong flow of such products in the local and regional markets in affordable prices. Taking into account the contradictory evidence about the fertility of the land around Euesperides by the ancient authors,Footnote 52 one may consider that the need for grain, which was abundant in Cyrene and its hinterland, may have stimulated inter-regional trade between Euesperides and the rest of Cyrenaica.