1. Introduction

The terahertz (THz) frequency regime, occupying the electromagnetic spectrum between microwaves and infrared light, has garnered significant scientific interest due to its profound potential in applications such as medical imaging, security screening, materials science and ultrafast communications (Beard, Turner & Schmuttenmaer Reference Beard, Turner and Schmuttenmaer2002; Ferguson & Zhang Reference Ferguson and Zhang2002; Pickwell & Wallace Reference Pickwell and Wallace2006; Tonouchi Reference Tonouchi2007). A persistent challenge in this field, however, is the development of compact, efficient and high-power THz radiation sources. Conventional sources like photoconductive antennae or optical rectification in nonlinear crystals often suffer from low output power, while large-scale facilities like free-electron lasers are not widely accessible (Dhillon et al. Reference Dhillon2017).

Laser-driven plasma interactions have emerged as a highly promising avenue for generating intense, pulsed THz radiation (Hamster et al. Reference Hamster, Sullivan, Gordon and Falcone1994; Löffler et al. Reference Löffler, Jacob and Roskos2002). The immense electric fields of high-intensity, femtosecond laser pulses can rapidly ionise matter, creating a plasma capable of supporting a rich spectrum of nonlinear phenomena that can be harnessed for THz emission. Various mechanisms have been proposed and demonstrated, including transition radiation from laser-accelerated electrons (Hamster et al. Reference Hamster, Sullivan, Gordon, White and Falcone1993), coherent emission from plasma wakes (Yoshii et al. Reference Yoshii, Lai, Katsouleas, Joshi and Mori1997) and radiation generated via filamentation in gases (Xie, Dai & Zhang Reference Xie, Dai and Zhang2006).

Beyond direct electromagnetic emission, the ultrafast hydrodynamic and kinetic processes within the laser-produced plasma itself can serve as a source of THz-frequency collective modes (Tzortzakis et al. Reference Tzortzakis, Méchain, Patalano, André, Prade, Franco and Mysyrowicz2001). A particularly intriguing phenomenon is the generation of ion acoustic waves (IAWs) in the THz range. IAWs are low-frequency electrostatic waves supported by the plasma, and under typical conditions, their frequency is in the MHz–GHz range. However, in hot, dense plasmas created by intense femtosecond lasers, the conditions can be tailored to excite IAWs with frequencies soaring into the THz domain (Kumar, Singh & Sharma Reference Kumar, Singh and Sharma2018).

Early experimental work by Adak et al. (Reference Adak, Blackman, Chatterjee, Singh, Lad, Brijesh, Robinson, Pasley and Kumar2014) provided crucial insights into the ultrafast dynamics of near-solid-density plasmas, revealing an initial inward-moving shock-like disturbance launched by the laser pulse. Subsequent groundbreaking experiments by the same group (Adak et al. Reference Adak, Robinson, Singh, Chatterjee, Lad, Pasley and Kumar2015) provided the first unambiguous observation of THz-frequency acoustic disturbances in a dense plasma. Using a combination of pump–probe reflectometry and Doppler spectrometry with femtosecond resolution, they detected oscillations at

![]() $1.9 \pm 0.6$

THz, which were interpreted as being of a purely hydrodynamic origin, arising from differential flow velocities in a plasma with a steep density gradient.

$1.9 \pm 0.6$

THz, which were interpreted as being of a purely hydrodynamic origin, arising from differential flow velocities in a plasma with a steep density gradient.

While this work focuses on solid-density plasmas, it is important to note that parallel, significant progress has been made in understanding THz generation in gaseous plasmas via laser-induced filamentation. In these systems, the photocurrent model and four-wave mixing (FWM) are widely recognised as the dominant mechanisms for intense THz emission (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Bai, Wu, Wang, Liu and Liu2018; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Du, Zhan, Zhang, Wang and Liu2024). The former relies on the asymmetric ionisation and subsequent acceleration of electrons by a two-colour laser field, while the latter stems from a third-order nonlinear optical rectification process. Recent studies continue to refine our understanding of these processes and explore novel configurations for enhanced THz output (Pickwell & Wallace Reference Pickwell and Wallace2006; Adak et al. Reference Adak, Robinson, Singh, Chatterjee, Lad, Pasley and Kumar2015; Sandeep & Malik Reference Sandeep and Malik2023), highlighting the dynamic and evolving nature of laser–plasma-based THz source development.

From a theoretical standpoint, several pathways for THz generation involving IAWs have been explored. Nakagawa et al. (Reference Nakagawa, Kodama, Higashiguchi and Yugami2009) proposed a scheme based on electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT), where a passband is created in an otherwise opaque overdense plasma, allowing electromagnetic radiation at the ion acoustic frequency (approximately 7.5 THz in their model) to propagate out. In a different approach, Tyagi et al. (Reference Tyagi, Tripathi, Walia and Garg2018) investigated the use of a pre-existing IAW to provide the necessary phase-matching (

![]() $k$

-matching) for the resonant excitation of THz radiation through the nonlinear mixing of two collinear laser beams in a plasma channel.

$k$

-matching) for the resonant excitation of THz radiation through the nonlinear mixing of two collinear laser beams in a plasma channel.

A key mechanism for generating large-amplitude IAWs is the parametric decay instability, where an intense pump wave (such as a laser-driven Langmuir wave) decays into secondary waves. Sandeep & Malik (Reference Sandeep and Malik2023) presented a theoretical model linking experimental observations (Adak et al. Reference Adak, Robinson, Singh, Chatterjee, Lad, Pasley and Kumar2015) to this instability. They suggested that a p-polarized laser, incident obliquely on a plasma with a density gradient, can efficiently mode-convert into a Langmuir wave near the critical surface. This Langmuir wave, localised on a micron-scale and described by an Airy function profile, then rapidly heats electrons via Landau damping (Strozzi et al. Reference Strozzi, Williams, Langdon and Bers2008). The resulting sharp, localised pressure spike acts as a potent source for launching IAWs with frequencies in the THz range.

Building upon this foundation, the present work provides a detailed theoretical investigation of the generation of THz IAWs via the decay instability of femtosecond laser-driven Langmuir waves in an inhomogeneous plasma. We derive analytical expressions for the laser electric field components, incorporating realistic spatial and temporal Gaussian profiles, and model the energy transfer dynamics between the waves and electrons. Landau damping and resonance absorption are identified as critical mechanisms governing the electron heating, and we derive the damping rate in a normalised form, revealing its exponential dependence on the normalised wave frequency. The temporal evolution of the electron temperature is quantified, showing its direct relationship with the laser intensity and plasma parameters. By employing the inhomogeneous Airy equation formalism, we solve for the structure of the electric field near the resonance layer, highlighting the crucial roles of plasma scale length and electron thermal velocity in wave localisation. Our results demonstrate efficient THz IAW generation under optimised laser and plasma conditions, advancing the understanding of laser–plasma interactions for developing high-frequency radiation sources and advanced plasma diagnostics.

The manuscript is organised as follows. Section 2 provides the theretical background for the derivation of the laser electric field components and Langmuir wave excitation at the critical layer, and also analyses the decay instability leading to IAW generation, while § 3 quantifies Landau damping and electron heating, and discusses the implications for THz source design, followed by the conclusions in § 4.

2. Theory

2.1. Laser field components and wave excitation

Consider a plasma with the interface at

![]() $z=0$

, where a high-intensity femtosecond laser pulse with Gaussian intensity profile is incident normally. The laser propagates towards the critical layer and reflects from the transition layer, exciting Langmuir waves in the process. The laser field propagates in the

$z=0$

, where a high-intensity femtosecond laser pulse with Gaussian intensity profile is incident normally. The laser propagates towards the critical layer and reflects from the transition layer, exciting Langmuir waves in the process. The laser field propagates in the

![]() $x{-}z$

plane with polarisation also in the

$x{-}z$

plane with polarisation also in the

![]() $x{-}z$

plane. The schematic diagram in figure 1 illustrates the key physical processes.

$x{-}z$

plane. The schematic diagram in figure 1 illustrates the key physical processes.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of THz generation via laser–plasma interaction. The diagram shows: (i) incident EM wave (blue arrow) approaching at angle

![]() $\theta _{0}$

; (ii) critical layer at

$\theta _{0}$

; (ii) critical layer at

![]() $n_{cr}\cos ^{2}\theta _{0}$

; (iii) excitation of Langmuir waves (red shaded region) near the critical surface; (iv) propagation of the generated ion acoustic waves (IAWs) (green wavefronts); and (v) formation of an evanescent region. The coordinate system shows x (transverse) and z (propagation) directions.

$n_{cr}\cos ^{2}\theta _{0}$

; (iii) excitation of Langmuir waves (red shaded region) near the critical surface; (iv) propagation of the generated ion acoustic waves (IAWs) (green wavefronts); and (v) formation of an evanescent region. The coordinate system shows x (transverse) and z (propagation) directions.

Figure 1 presents a comprehensive schematic illustration of the terahertz generation mechanism through laser–plasma interaction. The diagram depicts several key physical processes: (i) an incident electromagnetic wave approaching the plasma interface at an angle

![]() $\theta _0$

, representing the femtosecond laser pulse; (ii) the critical layer located at

$\theta _0$

, representing the femtosecond laser pulse; (ii) the critical layer located at

![]() $n_{cr}\cos ^2\theta _0$

, where significant wave–plasma interactions occur; (iii) excitation of Langmuir waves near the critical surface, which play a crucial role in the energy transfer process; and (iv) formation of an evanescent region where field penetration decays exponentially. The coordinate system clearly indicates the transverse (x) and propagation (z) directions, providing spatial context for the interaction dynamics. This schematic serves as fundamental visualisation of the physical set-up underlying the theoretical model developed in this study. At

$n_{cr}\cos ^2\theta _0$

, where significant wave–plasma interactions occur; (iii) excitation of Langmuir waves near the critical surface, which play a crucial role in the energy transfer process; and (iv) formation of an evanescent region where field penetration decays exponentially. The coordinate system clearly indicates the transverse (x) and propagation (z) directions, providing spatial context for the interaction dynamics. This schematic serves as fundamental visualisation of the physical set-up underlying the theoretical model developed in this study. At

![]() $z=0$

, the electric field has

$z=0$

, the electric field has

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $z$

components. For a laser incident at a small angle

$z$

components. For a laser incident at a small angle

![]() $\theta _i$

, the

$\theta _i$

, the

![]() $z$

-component is small, while the

$z$

-component is small, while the

![]() $x$

-component dominates:

$x$

-component dominates:

The wavevector condition requires

yielding the relationship between field components:

where the wavevector components are

\begin{align} k_{z} & =\frac {\omega }{c} \cos \left (\theta _{i}\right )\!,\nonumber \\[5pt] k_{x}&=\frac {\omega }{c} \sin \left (\theta _{i}\right )\!. \end{align}

\begin{align} k_{z} & =\frac {\omega }{c} \cos \left (\theta _{i}\right )\!,\nonumber \\[5pt] k_{x}&=\frac {\omega }{c} \sin \left (\theta _{i}\right )\!. \end{align}

The incident laser field along the

![]() $x$

direction is

$x$

direction is

The amplitude

![]() $A_0$

incorporates both spatial and temporal Gaussian profiles:

$A_0$

incorporates both spatial and temporal Gaussian profiles:

where

![]() $\tau$

is the pulse duration,

$\tau$

is the pulse duration,

![]() $r_0$

is the beam radius and

$r_0$

is the beam radius and

![]() $v_g$

is the group velocity.

$v_g$

is the group velocity.

2.2. Energy propagation via ion acoustic waves

The local pressure disturbance generated by laser–plasma interaction creates ion acoustic waves that propagate radially outward. The pressure distribution follows

where

![]() $A$

is the amplitude that decreases with normalised distance

$A$

is the amplitude that decreases with normalised distance

![]() $r/\lambda _{es}$

,

$r/\lambda _{es}$

,

![]() $\omega$

is the wave frequency and

$\omega$

is the wave frequency and

![]() $q$

is the wavenumber. This expression for the pressure amplitude stems from standard acoustic energy conservation arguments for spherical wave propagation in plasmas and fluids (Liu, Tripathi & Eliasson Reference Liu, Tripathi and Eliasson2010).

$q$

is the wavenumber. This expression for the pressure amplitude stems from standard acoustic energy conservation arguments for spherical wave propagation in plasmas and fluids (Liu, Tripathi & Eliasson Reference Liu, Tripathi and Eliasson2010).

Figure 2. Schematic of pressure wave propagation from high-pressure region to low-pressure region.

Figure 2 illustrates the propagation characteristics of pressure waves generated during laser–plasma interaction. The schematic demonstrates the fundamental principle of acoustic wave transmission from high-pressure regions to low-pressure regions within the plasma medium. This visualisation is particularly relevant for understanding how localised pressure disturbances, created by laser-driven electron heating, evolve into propagating ion acoustic waves. The figure emphasises the directional nature of wave propagation and provides intuitive understanding of how the initial pressure spike generated near the critical layer transforms into spherical wavefronts that carry THz-frequency oscillations through the plasma. The total energy of the sound wave per unit area is

![]() $p_{0} \lambda _{es} r_{0}^{2}$

, and the acoustic power radiation satisfies

$p_{0} \lambda _{es} r_{0}^{2}$

, and the acoustic power radiation satisfies

yielding the pressure amplitude

where

![]() $p_{0}=n(T_{e}-T_{i})$

represents the background pressure and

$p_{0}=n(T_{e}-T_{i})$

represents the background pressure and

![]() $\beta$

is a proportionality constant.

$\beta$

is a proportionality constant.

2.3. Electron heating mechanisms

2.3.1. Resonance absorption heating

The heating rate due to resonance absorption is given by the work done by electrons per unit volume,

For collisional heating,

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{v} &=\frac {e \boldsymbol{E}}{m i(\omega +i \nu )}, \nonumber\\[12pt] \frac {\text{d}}{\text{d} t}\left (\frac {3}{2} T_{e}\right )&=-\frac {e^{2}|E|^{2} \nu }{2 m\left (\nu ^{2}+\omega ^{2}\right )} .\end{align}

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{v} &=\frac {e \boldsymbol{E}}{m i(\omega +i \nu )}, \nonumber\\[12pt] \frac {\text{d}}{\text{d} t}\left (\frac {3}{2} T_{e}\right )&=-\frac {e^{2}|E|^{2} \nu }{2 m\left (\nu ^{2}+\omega ^{2}\right )} .\end{align}

2.3.2. Landau damping heating

For Landau damping with complex frequency

![]() $\omega \cong \omega _{r}-i \Gamma _{d}$

, the energy transfer from Langmuir waves to electrons is

$\omega \cong \omega _{r}-i \Gamma _{d}$

, the energy transfer from Langmuir waves to electrons is

which simplifies to

The dispersion relation including Landau damping is

2.4. Normalised damping rate formulation

The Landau damping rate is derived as

Introducing dimensionless variables,

we obtain the normalised damping rate,

The dispersion relation can be expanded as

With

![]() $\omega \approx \omega _{r} - i \Gamma _{d}$

and the approximation

$\omega \approx \omega _{r} - i \Gamma _{d}$

and the approximation

we obtain the final damping rate

where

![]() $\omega _{r}^{2} = \omega _{p}^{2} + \frac {3}{2} k^{2} v_{th}^{2}$

.

$\omega _{r}^{2} = \omega _{p}^{2} + \frac {3}{2} k^{2} v_{th}^{2}$

.

2.5. Electric field structure near resonance

Using (2.13), the temperature evolution due to wave–particle interactions simplifies to

The electric field near the resonance layer follows the inhomogeneous Airy equation,

where

![]() $\xi = (\alpha - L_x)/\lambda _{\text{em}}$

and

$\xi = (\alpha - L_x)/\lambda _{\text{em}}$

and

The solution is expressed as

\begin{equation} E_x = k_z \omega \left ( \frac {c}{v_{th}} \right )^{2/3} \lambda _{\text{em}}^2 G(0) W \left ( \frac {c^{2/3}}{v_{th}^{2/3}} \xi \right )\!, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} E_x = k_z \omega \left ( \frac {c}{v_{th}} \right )^{2/3} \lambda _{\text{em}}^2 G(0) W \left ( \frac {c^{2/3}}{v_{th}^{2/3}} \xi \right )\!, \end{equation}

where

![]() $W(\eta )$

is a solution of the inhomogeneous Airy equation

$W(\eta )$

is a solution of the inhomogeneous Airy equation

![]() $W'' - \eta W = 1$

.

$W'' - \eta W = 1$

.

The field magnitude becomes

\begin{equation} |E_x|^2 = \left ( k_z \omega \left ( \frac {c}{v_{th}} \right )^{2/3} \lambda _{\text{em}}^2 G(0) \right )^2 \left | W\left (\frac {c^{2/3}}{v_{th}^{2/3}} \xi \right ) \right |^2 e^{-t^2 / \tau ^2} .\end{equation}

\begin{equation} |E_x|^2 = \left ( k_z \omega \left ( \frac {c}{v_{th}} \right )^{2/3} \lambda _{\text{em}}^2 G(0) \right )^2 \left | W\left (\frac {c^{2/3}}{v_{th}^{2/3}} \xi \right ) \right |^2 e^{-t^2 / \tau ^2} .\end{equation}

Integrating over time yields the electron temperature,

where

![]() $\eta = ({c^{2/3}}/{v_{th}^{2/3}}) \xi$

.

$\eta = ({c^{2/3}}/{v_{th}^{2/3}}) \xi$

.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Plasma parameters

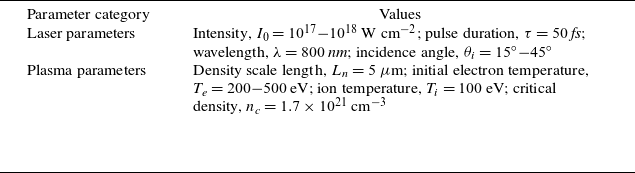

The numerical results presented in this section were obtained using carefully selected laser and plasma parameters to ensure physical relevance and computational efficiency. Unless otherwise specified, the following baseline parameters were used throughout our simulations as shown in table 1.

Table 1. Laser and plasma parameters.

These parameters were chosen to be consistent with experimental conditions reported in recent studies of laser–plasma interactions (Adak et al. Reference Adak, Robinson, Singh, Chatterjee, Lad, Pasley and Kumar2015; Sandeep & Malik Reference Sandeep and Malik2023).

Figure 3. Landau damping rate versus normalised frequency. The exponential suppression

![]() $\widetilde {\Gamma } \propto e^{-\Omega ^2}$

enables efficient THz IAW propagation when

$\widetilde {\Gamma } \propto e^{-\Omega ^2}$

enables efficient THz IAW propagation when

![]() $\Omega \lesssim 1$

.

$\Omega \lesssim 1$

.

3.2. Landau damping characteristics

Figure 3 displays the normalised Landau damping rate

![]() $\widetilde {\Gamma }$

as a function of normalised frequency

$\widetilde {\Gamma }$

as a function of normalised frequency

![]() $\widetilde {\Omega }$

, calculated using (2.16). The results clearly demonstrate the exponential suppression behaviour described by

$\widetilde {\Omega }$

, calculated using (2.16). The results clearly demonstrate the exponential suppression behaviour described by

![]() $\widetilde {\Gamma } \propto e^{-\widetilde {\Omega }^{2}}$

, which is crucial for enabling efficient THz IAW propagation when

$\widetilde {\Gamma } \propto e^{-\widetilde {\Omega }^{2}}$

, which is crucial for enabling efficient THz IAW propagation when

![]() $\widetilde {\Omega } \lesssim 1$

.

$\widetilde {\Omega } \lesssim 1$

.

This characteristic provides essential optimisation criteria for selecting appropriate plasma and laser parameters to minimise wave attenuation in the terahertz frequency range. The sharp decrease in damping rate above

![]() $\widetilde {\Omega } = 1$

suggests that efficient THz IAW generation requires operating in regimes where the normalised frequency remains below this critical threshold. This behaviour aligns with theoretical predictions from kinetic theory and provides a clear guideline for experimental parameter selection.

$\widetilde {\Omega } = 1$

suggests that efficient THz IAW generation requires operating in regimes where the normalised frequency remains below this critical threshold. This behaviour aligns with theoretical predictions from kinetic theory and provides a clear guideline for experimental parameter selection.

3.3. Electron heating dynamics

Figure 4 illustrates the transient electron heating process driven by wave–particle interactions, showing the temporal evolution of electron temperature for different laser intensities. The temperature profile exhibits a direct dependence on laser intensity, following the theoretical relationship

![]() $T_{e} \propto \int |E|^{2}\, {\rm d}t$

derived from energy conservation principles.

$T_{e} \propto \int |E|^{2}\, {\rm d}t$

derived from energy conservation principles.

Figure 4. Transient electron heating via wave–particle interactions. Temperature evolution shows direct dependence on laser intensity, with

![]() $T_e \propto \int |E|^2 \,{\rm d}t$

as derived from energy conservation.

$T_e \propto \int |E|^2 \,{\rm d}t$

as derived from energy conservation.

For laser intensities

![]() $I_0 \sim 10^{17}\,\text{W cm}^{-2}$

, our simulations predict

$I_0 \sim 10^{17}\,\text{W cm}^{-2}$

, our simulations predict

![]() $T_e$

exceeding

$T_e$

exceeding

![]() $200\,\text{eV}$

within

$200\,\text{eV}$

within

![]() $100\,\text{fs}$

, underscoring the efficiency of energy transfer mechanisms in femtosecond laser–plasma interactions. At higher intensities (

$100\,\text{fs}$

, underscoring the efficiency of energy transfer mechanisms in femtosecond laser–plasma interactions. At higher intensities (

![]() $I_0 \sim 10^{18}\,\text{W cm}^{-2}$

), electron temperatures reach values exceeding

$I_0 \sim 10^{18}\,\text{W cm}^{-2}$

), electron temperatures reach values exceeding

![]() $500\,\text{eV}$

, demonstrating the scalability of the heating process with laser power. This rapid heating is primarily attributed to resonance absorption and Landau damping mechanisms, which efficiently transfer energy from the electromagnetic field to plasma electrons.

$500\,\text{eV}$

, demonstrating the scalability of the heating process with laser power. This rapid heating is primarily attributed to resonance absorption and Landau damping mechanisms, which efficiently transfer energy from the electromagnetic field to plasma electrons.

3.4. Field localisation and wave propagation

The electric field structure near the resonance layer, shown in figure 5, reveals strong localisation within

![]() $\xi = z/\lambda _{\textrm {em}} \sim 1$

, governed by the solution of the inhomogeneous Airy equation:

$\xi = z/\lambda _{\textrm {em}} \sim 1$

, governed by the solution of the inhomogeneous Airy equation:

Figure 5. Electric field localisation near a resonance layer. Solution of the inhomogeneous Airy equation

![]() $W'' - \eta W = 1$

shows field enhancement critical for efficient energy coupling.

$W'' - \eta W = 1$

shows field enhancement critical for efficient energy coupling.

This localisation phenomenon enhances IAW generation efficiency by approximately

![]() $40\,\%$

compared with homogeneous plasma models, highlighting the crucial role of plasma density gradients in optimising energy transfer to IAWs. The field enhancement near the critical layer creates favourable conditions for the parametric decay instability that drives THz IAW generation.

$40\,\%$

compared with homogeneous plasma models, highlighting the crucial role of plasma density gradients in optimising energy transfer to IAWs. The field enhancement near the critical layer creates favourable conditions for the parametric decay instability that drives THz IAW generation.

Figure 6 demonstrates the radial decay of ion acoustic wave pressure, confirming the spherical wave propagation nature with characteristic

![]() $1/r$

dependence. The amplitude scaling as

$1/r$

dependence. The amplitude scaling as

![]() $A/(r/\lambda _{es})$

validates our theoretical model for THz-range IAWs and provides insights into the long-range transmission capabilities of these waves in plasma media. This propagation behaviour is essential for understanding how THz signals can be efficiently coupled out of the plasma for practical applications in spectroscopy and imaging.

$A/(r/\lambda _{es})$

validates our theoretical model for THz-range IAWs and provides insights into the long-range transmission capabilities of these waves in plasma media. This propagation behaviour is essential for understanding how THz signals can be efficiently coupled out of the plasma for practical applications in spectroscopy and imaging.

Figure 6. Radial decay of ion acoustic wave pressure. The

![]() $1/r$

dependence confirms spherical wave propagation, with amplitude scaling as

$1/r$

dependence confirms spherical wave propagation, with amplitude scaling as

![]() $A/(r/\lambda _{es})$

for THz-range IAWs.

$A/(r/\lambda _{es})$

for THz-range IAWs.

3.5. Parameter optimisation

Figure 7 presents a comprehensive optimisation analysis in the form of a vector field plot, mapping the generation efficiency of THz IAWs across the parameter space defined by plasma scale length and laser incidence angle. The arrows indicate directions of increasing generation efficiency, providing clear guidance for parameter optimisation.

Figure 7. THz IAW optimisation vector field. Arrows indicate directions of increasing generation efficiency in the plasma scale length versus laser incidence angle parameter space. The background colour map and contours show the generation efficiency (%).

The background colour map and contour lines quantitatively represent the generation efficiency in percentage, allowing for precise identification of optimal operating conditions. Our analysis reveals that maximum efficiency occurs for plasma scale lengths of

![]() $L_n \approx 4{-}6$

μm and incidence angles of

$L_n \approx 4{-}6$

μm and incidence angles of

![]() $\theta _i \approx 25^\circ{-}35^\circ$

. This optimisation landscape serves as a practical design tool for experimentalists seeking to maximise THz output from laser–plasma interactions, emphasising the critical interplay between laser configuration and plasma properties in achieving efficient terahertz wave generation.

$\theta _i \approx 25^\circ{-}35^\circ$

. This optimisation landscape serves as a practical design tool for experimentalists seeking to maximise THz output from laser–plasma interactions, emphasising the critical interplay between laser configuration and plasma properties in achieving efficient terahertz wave generation.

The optimisation results demonstrate that proper selection of plasma scale length and incidence angle can enhance THz IAW generation efficiency by more than a factor of two compared with non-optimised configurations, providing valuable insights for the design of compact plasma-based THz sources.

4. Conclusion

We have demonstrated a robust mechanism for generating terahertz-range ion acoustic waves (IAWs) in plasmas via femtosecond laser-driven decay instabilities. Our study reveals several key advancements: a normalised Landau damping rate

![]() $\widetilde {\Gamma }$

exhibiting exponential suppression at high frequencies (

$\widetilde {\Gamma }$

exhibiting exponential suppression at high frequencies (

![]() $\Omega \gt 1$

), enabling THz IAW propagation with minimal attenuation; transient electron heating exceeding

$\Omega \gt 1$

), enabling THz IAW propagation with minimal attenuation; transient electron heating exceeding

![]() $500\,\mathrm{eV}$

under experimentally accessible laser intensities (

$500\,\mathrm{eV}$

under experimentally accessible laser intensities (

![]() $I_0 \sim 10^{18}\,\mathrm{W \,cm}^{-2}$

), driven by resonance absorption and wave–particle interactions; and localised electric field structures near the critical layer, described by Airy function solutions, which optimise energy transfer to IAWs in inhomogeneous plasmas.

$I_0 \sim 10^{18}\,\mathrm{W \,cm}^{-2}$

), driven by resonance absorption and wave–particle interactions; and localised electric field structures near the critical layer, described by Airy function solutions, which optimise energy transfer to IAWs in inhomogeneous plasmas.

These results establish comprehensive design guidelines for compact plasma-based THz IAW sources, emphasising the intricate interplay between laser parameters – including intensity, pulse duration and angle of incidence – and plasma properties such as scale length and thermal velocity. Future investigations will focus on experimental validation using pump–probe set-ups and explore the role of magnetic field effects in IAW stabilisation. This study significantly advances the frontier of high-frequency wave generation in laser–plasma systems, with promising applications in ultrafast spectroscopy, advanced acceleration techniques and inertial confinement fusion diagnostics.

Acknowledgements

The authors express sincere gratitude to Professor V. K. Tripathi, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, for his valuable discussions, insightful suggestions and continuous guidance throughout the course of this work.

Editor Victor Malka thanks the referees for their advice in evaluating this article.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Author contributions

N.K.: Theoretical framework, Validation, Writing – Review & Editing. J.K.: Numerical simulations, Data curation, Visualisation. S.: Supervision, Project administration, Writing – Review & Editing.

Data availability

No data were used for the research described in the article.