Highlights

-

• The study investigated CLI in three stages of grammatical gender development.

-

• CLI was investigated in a language with a non-transparent system: Dutch.

-

• CLI was found in all stages of gender development for Dutch-German bilingual children.

-

• CLI simultaneously facilitated and hindered gender acquisition.

-

• Findings suggest co-activation of grammatical gender values.

1. Introduction

The influence of one of a bilingual’s languages on the other is known as cross-linguistic influence and is part and parcel of bilingual development (Van Dijk et al., Reference Van Dijk, Van Wonderen, Koutamanis, Kootstra, Dijkstra and Unsworth2022). Extensive research has explored cross-linguistic influence in bilingual children, particularly in the context of grammatical gender development (e.g., Egger et al., Reference Egger, Hulk and Tsimpli2018; Kaltsa et al., Reference Kaltsa, Tsimpli and Argyri2019; Kupisch et al., Reference Kupisch, Geiss, Mitrofanova and Westergaard2022; Rodina et al., Reference Rodina, Kupisch, Meir, Mitrofanova, Urek and Westergaard2020). Cross-linguistic influence can occur at three stages of grammatical gender acquisition: the discovery of grammatical gender in the target language, the assignment of grammatical gender to a noun and the agreement of grammatical gender with other phrasal elements (Unsworth, Reference Unsworth2013). Many studies have investigated cross-linguistic influence in languages with transparent gender systems (e.g., Kaltsa et al., Reference Kaltsa, Tsimpli and Argyri2019; Kupisch et al., Reference Kupisch, Geiss, Mitrofanova and Westergaard2022; Rodina et al., Reference Rodina, Kupisch, Meir, Mitrofanova, Urek and Westergaard2020), but few have identified at what stage cross-linguistic influence occurs when languages with non-transparent gender systems are being acquired. The aim of the present study is, therefore, to explore if there is cross-linguistic influence in the bilingual acquisition of a non-transparent gender system and at what stage of acquisition it occurs. To that end, we investigated the acquisition of grammatical gender in children who were acquiring the non-transparent gender system of Dutch as a heritage language in one of two societal language contexts: France or Germany.

1.1. Grammatical gender

Grammatical gender is a property of the noun that exists – in various forms – in many languages. Languages with grammatical gender classify nouns into different categories or gender values (Corbett, Reference Corbett1991). For example, Dutch has two gender values: common (e.g., de auto “the car”) and neuter (e.g., het bed “the bed”). Other frequent gender values include masculine and feminine (e.g., French) or masculine, feminine and neuter (e.g., German). Grammatical gender establishes agreement between the gender value of the noun and other phrasal elements, such as determiners and adjectives (e.g., Spanish: una casa blanca “a.f house (f) white.f;” Corbett, Reference Corbett1991).

Two main theoretical accounts address the representation of grammatical gender. The lexicalist approach argues that gender is an inherent characteristic of the noun stored in the lexicon, determining the form of nouns and agreeing words in syntactic processing (e.g., Corbett, Reference Corbett1991). The syntactic approach, on the other hand, proposes that gender is not a lexical feature but is introduced within the syntactic derivation (e.g., Kramer, Reference Kramer2016, Reference Kramer2020). As the theoretical debate is not central to our research questions, and neither of the approaches is in conflict with our design, we do not adopt a specific position.

Across languages, children differ in the speed at which they acquire the gender system of the target language. The transparency of the gender system is considered key in explaining such cross-language differences (e.g., Kupisch et al., Reference Kupisch, Müller and Cantone2002; Velnić, Reference Velnić2020). The transparency of a gender system depends on the transparency of cues on elements associated with the noun, such as determiners and adjectives, that is, noun-external cues, and on the noun itself, that is, noun-internal cues (Kupisch et al., Reference Kupisch, Geiss, Mitrofanova and Westergaard2022). Gender assignment is typically determined by multiple types of noun-internal cues within one language. Cues can be semantic (German nouns denoting fruits tend to be feminine), morphological (German diminutives are always neuter) and phonological (German nouns ending in schwa tend to be feminine; Köpcke, Reference Köpcke1982). Gender systems differ in the existence and transparency of cues. In languages with transparent gender systems, morphophonological markers provide consistent noun-internal and noun-external cues (e.g., Spanish: nouns ending in -a are feminine, agreeing words are marked with -a – una casa blanca “a.f house (f) white.f;” Harris, Reference Harris1991). Semi-transparent gender systems provide cues for gender assignment, although some cues are ambiguous (e.g., French: most nouns ending in nasal vowels are masculine; German: almost all nouns ending in schwa are feminine; Köpcke, Reference Köpcke1982; Lyster, Reference Lyster2006). Non-transparent gender systems, on the other hand, provide limited cues for predicting a noun’s gender (e.g., Dutch; Unsworth, Reference Unsworth2013). Transparent systems are acquired early, whereas non-transparent systems take longer to acquire (Ogneva, Reference Ogneva2023).

1.2. Cross-linguistic influence

The languages of a bilingual can vary with regard to the existence of grammatical gender, the transparency of the gender systems, and the similarities between the systems. In bilingual children, the acquisition of grammatical gender in one language can, therefore, also be influenced by the properties of the other language. The properties of a bilingual’s languages may accelerate or delay the acquisition of the gender system in the target language. The general idea is that a language without a grammatical gender system can delay the acquisition of a grammatical gender system and that a language with a more transparent gender system can accelerate the acquisition of a less transparent system (Kupisch et al., Reference Kupisch, Geiss, Mitrofanova and Westergaard2022).

The properties of a bilingual’s languages may affect the stage at which cross-linguistic influence takes place. It is generally assumed that in order to acquire grammatical gender, children need to learn (1) that grammatical gender is a feature of the noun, that is, gender discovery, (2) the gender specification of the noun in question, that is, gender assignment and (3) how to mark for agreement with other phrasal elements, that is, gender agreement (Unsworth, Reference Unsworth2013). Cross-linguistic influence can take place at one or multiple of these stages. We consider each in turn.

1.2.1. Cross-linguistic influence in gender discovery

Cross-linguistic influence in gender discovery entails that – under the influence of a more transparent gender system in the bilingual’s other language – grammatical gender as a feature of the noun is discovered earlier in the target language compared to monolingual children or bilingual children with a different language combination (e.g., Egger et al., Reference Egger, Hulk and Tsimpli2018; Kaltsa et al., Reference Kaltsa, Tsimpli and Argyri2019). Roeper (Reference Roeper2012) proposed that the appearance of a phenomenon in one language can trigger it in the other language at an abstract level. Likewise, Egger et al. (Reference Egger, Hulk and Tsimpli2018) suggested that having acquired a gender system in a more transparent language increases children’s awareness of grammatical gender as a feature and that this facilitates the discovery of grammatical gender in the less transparent language.

1.2.2. Cross-linguistic influence in gender assignment

Cross-linguistic influence in gender assignment entails that properties of the grammatical gender system of one language influence gender assignment in the other language. As noted above, cross-linguistic influence in gender assignment has mainly been investigated for transparent languages. It has been suggested that abstract knowledge of rules, for example, that noun-internal cues can be used to predict gender, can be transferred across languages (Kupisch et al., Reference Kupisch, Geiss, Mitrofanova and Westergaard2022). When this rule applies to both languages, this may lead to acceleration. In languages with non-transparent gender systems, however, few or no cues exist that predict the gender of a noun. Therefore the transfer of abstract rules will not accelerate the acquisition of a non-transparent gender system. However, for certain language combinations, cross-linguistic influence might still occur at the stage of gender assignment, that is, when a bilingual’s languages share gender values (Klassen, Reference Klassen2016). Such overlap could lead to integrated representations of gender values, allowing co-activation of corresponding gender values across languages (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Integrated gender system in bilinguals adapted from Klassen (Reference Klassen2016) for congruent nouns (left) and incongruent nouns (right). Masculine and feminine have merged into one gender in Dutch: common.

Integrated gender systems have thus far mainly been investigated for adult L2 learners (e.g., Lemhöfer et al., Reference Lemhöfer, Spalek and Schriefers2008; Manolescu & Jarema, Reference Manolescu and Jarema2015). A recent meta-analysis has suggested that, in adult L2 learners, gender values become integrated when they overlap between a bilingual’s languages (Sá-Leite et al., Reference Sá-Leite, Luna, Fraga and Comesaña2020). In such cases, the activation of a lexical item in one language co-activates the gender value of its translation equivalent, as well as the gender value in the target language. This co-activation may affect gender assignment on the item level during processing (Chondrogianni, Reference Chondrogianni, Elgort, Siyanova-Chanturia and Brysbaert2023), as illustrated by the example from Dutch and German in Figure 1. In both languages, the lexical item “bed” (Dutch: bed; German; Bett) has neuter gender. Therefore, only the neuter gender value will be activated. The lexical item “car” (Dutch: auto; German: Auto) has incongruent gender values between the languages, having common gender in Dutch and neuter gender in German. Both gender values will, therefore, be activated and compete for selection (Sá-Leite et al., Reference Sá-Leite, Fraga and Comesaña2019). Such co-activation can boost the selection of the correct gender value when lexical items are gender congruent, but may occasionally result in the selection of the incorrect gender value for lexical items when gender values are incongruent.

For adult second language learners, it is assumed that the acquisition of the L2 builds upon existing grammatical features of the L1, including grammatical gender values, which may underlie shared representations (Sá-Leite et al., Reference Sá-Leite, Fraga and Comesaña2019). In bilingual children, the dependencies between languages are less clear-cut than in adult second language learners. It, therefore, remains unclear if, and if so, how integrated representations develop in the gender systems of bilingual children. There exist only a few studies investigating integrated representations of grammatical gender in which participants were bilingual adults who learned both languages during childhood. Manolescu and Jarema (Reference Manolescu and Jarema2015) investigated grammatical gender in French-Romanian bilinguals and found that participants were quicker in naming stimulus items that had congruent gender in French and Romanian. Such a gender congruency effect was considered evidence for integrated representations of gender values. These findings suggest that gender values become connected not only when an L2 gender system is acquired in adulthood, but also when two gender systems are acquired simultaneously during childhood.

1.2.3. Cross-linguistic influence in gender agreement

Cross-linguistic influence in gender agreement entails that similarities in the way grammatical gender is marked between a bilingual’s languages may accelerate the acquisition of gender agreement rules, whereas differences or the absence of gender agreement in one of a bilingual’s languages may delay its development in the target language. This is illustrated in Schwartz et al.’s (Reference Schwartz, Minkov, Dieser, Protassova, Moin and Polinsky2015) study investigating adjectival gender inflection in bilingual Russian children. Children’s other languages varied from Russian with respect to adjectival inflection: some languages did not have grammatical gender (English) or adjectival inflection (Finnish), whereas others did but varied in how gender was marked on adjectives compared to Russian (different: Hebrew; similar: German). Schwartz and colleagues found that children who had adjectival inflection in the other language (German and Hebrew) outperformed children who spoke a language without adjectival inflection – or gender at all – in the other language (Finnish and English) on adjectival inflection in Russian. They additionally found that more proximity between languages facilitated gender marking in Russian, whereby the Russian-German children outperformed the other groups. This was interpreted as evidence that one of a bilingual’s languages plays a considerable role in the acquisition of gender agreement in the other language.

In sum, cross-linguistic influence may occur during gender discovery, gender assignment and gender agreement. The properties of a bilingual’s languages affect the stages at which cross-linguistic influence can take place. Few studies have investigated cross-linguistic influence in non-transparent gender systems. The present study, therefore, investigates the development of grammatical gender in bilingual Dutch-French children in France and bilingual Dutch-German children in Germany. Both societal languages have more transparent gender systems than Dutch, but they vary in typological proximity to Dutch. German is typologically close, sharing gender values with Dutch, whereas French is typologically more distant. In what follows, we describe the gender systems of Dutch, French and German and their acquisition in more detail.

1.3. Grammatical gender in Dutch

Modern Standard Dutch has a two-gender system distinguishing common and neuter. Approximately 75% of Dutch nouns is common, and 25% is neuter (Hulk & Cornips, Reference Hulk and Cornips2006). Gender is marked on singular definite determiners and on adjectives in indefinite determiner phrases (DPs; Table 1). Grammatical gender is not marked on plural definite determiners – always de – nor on singular indefinite determiners – always een (Cornips & Hulk, Reference Cornips and Hulk2008). Thus, there is a limited number of contexts in which the gender distinction is unambiguously present.

Table 1. Description of the grammatical gender system of Dutch

Dutch used to have the same three-gender system as German (Van Berkum, Reference Van Berkum1996). In modern Standard Dutch, the masculine and feminine genders have merged into one common gender value. Many Dutch and German translation pairs have congruent gender values due to their common Germanic roots (Lemhöfer et al., Reference Lemhöfer, Spalek and Schriefers2008): most neuter nouns have a neuter-gender translation equivalent in Dutch, and many masculine and feminine German nouns have a common-gender translation equivalent in Dutch. This will be relevant for our experimental design.

There do exist some semantic classes which have predictable gender (e.g., names of metals are neuter; Blom et al., Reference Blom, Polišenská and Unsworth2008a), but such regularities are scarce and exceptions exist. The gender specification of nouns is, therefore, assumed to be arbitrary, and speakers need to identify a noun’s gender per individual item (Unsworth, Reference Unsworth2008).

1.3.1. Acquisition of grammatical gender in Dutch

The acquisition of grammatical gender in Dutch is late compared to other languages (Blom et al., Reference Blom, Polišenská and Weerman2008b). Despite the late mastery of the grammatical gender system as a whole, there is a striking contrast between the early appearance of the common determiner de and the relatively late acquisition of the neuter determiner het in Dutch children (Tsimpli & Hulk, Reference Tsimpli and Hulk2013). Several reasons have been put forward to explain this difference. First, there exists a distributional difference between de and het, whereby de predominates the input (Blom et al., Reference Blom, Polišenská and Weerman2008). The determiner de is not only used to distinguish common from neuter nouns in singular definite DPs, but it is also the determiner used for all plural definite nouns. In addition to the determiner de being more frequent in the input, there is a restricted number of syntactic contexts that require differentiation of common and neuter gender (see Table 1; Tsimpli & Hulk, Reference Tsimpli and Hulk2013). Syntactic contexts thus do not provide consistent cues for learners. Given the high frequency of de in the input and the small number of contexts that provide opportunities for learning, the determiner de is therefore argued not to be used as an indicator of grammatical gender in young acquirers of Dutch, but as a default determiner for definite nouns (Cornips & Gregersen, Reference Cornips, Gregersen, Blom, Cornips and Schaeffer2017; Keij et al., Reference Keij, Cornips, Van Hout, Hulk and Van Emmerik2012; Tsimpli & Hulk, Reference Tsimpli and Hulk2013). This explains the early emergence of the determiner de and the much later appearance of the neuter determiner het: in early stages of grammatical gender acquisition, children do not have a gender differentiation in their grammars yet (Keij et al., Reference Keij, Cornips, Van Hout, Hulk and Van Emmerik2012). In a later stage, children discover the existence of grammatical gender as a property of the noun and its operationalization in determiners de and het (Cornips & Gregersen, Reference Cornips, Gregersen, Blom, Cornips and Schaeffer2017). From that moment on, children start to identify the gender of individual nouns (Unsworth, Reference Unsworth2008, Reference Unsworth2013).

Previous research shows that children aged 6 and older still overgeneralize the common determiner de. For example, Blom et al. (Reference Blom, Polišenská and Unsworth2008a) demonstrated that although monolingual 7-year-olds perform above chance level for neuter nouns, determiner het did not yet appear in at least 90% of all obligatory contexts. Likewise, the monolingual children tested by Blom et al. (Reference Blom, Polišenská and Unsworth2008a) showed a steep increase in accuracy on neuter nouns between ages three and seven, but they did not reach the ceiling. The monolingual 6-year-olds tested by Unsworth (Reference Unsworth2013) performed at ceiling for common nouns but just above chance for neuter nouns. In short, monolingual Dutch children generally perform well on common nouns but have greater difficulty with neuter nouns.

Adjective agreement in children acquiring Dutch is marked by overgeneralization of inflection on adjectives where the uninflected form is required (i.e., for neuter indefinite singular nouns: *een grote huis instead of een groot huis “a big house;” Polišenská, Reference Polišenská2010). This could either be the case because children lack the knowledge of the inflectional rule or due to children’s classification of neuter nouns as having common gender (Kupisch et al., Reference Kupisch, Akpinar and Stöhr2013). This question has been addressed by Polišenská (Reference Polišenská2010), who found that when only nouns were considered that were consistently assigned the correct gender, accuracy on adjectival inflection was high in monolingual Dutch children. In other words, overgeneralization in adjectival inflection seems to originate from inaccurate gender assignment rather than the absence of the inflection rule.

Studies into the bilingual development of grammatical gender in Dutch (Blom et al., Reference Blom, Polišenská and Unsworth2008a; Egger et al., Reference Egger, Hulk and Tsimpli2018; Keij et al., Reference Keij, Cornips, Van Hout, Hulk and Van Emmerik2012; Orgassa & Weerman, Reference Orgassa and Weerman2008; Unsworth, Reference Unsworth2008, Reference Unsworth2013; Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Argyri, Cornips, Hulk, Sorace and Tsimpli2014) reveal a pattern for bilingual children that is similar to monolingual children – that is, overgeneralization of common de for neuter nouns – although somewhat delayed compared to monolingual peers (e.g., Blom et al., Reference Blom, Polišenská and Weerman2008b; Hulk & Cornips, Reference Hulk and Cornips2006; Keij et al., Reference Keij, Cornips, Van Hout, Hulk and Van Emmerik2012). Some studies have, therefore, explored the influence of language exposure on grammatical gender acquisition and found that exposure to Dutch was the most important predictor of grammatical gender accuracy in bilingual children (e.g., Egger et al., Reference Egger, Hulk and Tsimpli2018; Unsworth, Reference Unsworth2013). Adjective agreement in bilingual Dutch children is also comparable with that of monolingual children. For example, Unsworth (Reference Unsworth2013) found that monolingual and bilingual children behaved on a par when individual gender assignment was taken into account, suggesting that once children start identifying a noun’s gender, they apply agreement rules to adjectives.

Cross-linguistic influence in the acquisition of grammatical gender in Dutch has received little attention. Cornips et al. (Reference Cornips, Van Der Hoek and Verwer2006) investigated cross-linguistic influence in Dutch-Moroccan, Dutch-Berber and Dutch-Turkish children aged 10–12. Moroccan-Arabic and Berber have grammatical gender, whereas Turkish does not. Cross-linguistic influence in the form of acceleration was expected for children whose other language also has grammatical gender, that is, bilingual Dutch-Moroccan-Arabic and Dutch-Berber children. However, no significant differences were found between children with (Moroccan-Arabic and Berber) or without (Turkish) a grammatical gender system in their heritage language. In contrast, Egger et al. (Reference Egger, Hulk and Tsimpli2018) did find acceleration effects in the development of Dutch grammatical gender in bilingual Dutch-Greek children compared to bilingual Dutch-English children. English does not have grammatical gender, whereas Greek has a transparent gender system. Egger et al. (Reference Egger, Hulk and Tsimpli2018), therefore, predicted that Dutch-Greek bilingual children would benefit from their knowledge of the Greek gender system in the discovery of grammatical gender in Dutch. Dutch-Greek bilinguals indeed outperformed age-matched Dutch-English bilinguals and they performed on a par with Dutch monolingual children from the same age. Given that the bilingual children received quantitatively less input in Dutch than the monolinguals, this was interpreted as acceleration. Egger et al. (Reference Egger, Hulk and Tsimpli2018) suggested that this was due to children’s knowledge of Greek, making children aware of grammatical gender from early on.

All studies mentioned so far focused on Dutch as a societal language. To our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated the development of grammatical gender in Dutch as a heritage language. Doing this allows us to explore cross-linguistic influence in the acquisition of a non-transparent (input-dependent) structure in a context with limited exposure to the target language.

1.4. Grammatical gender in German

Modern Standard German has a three-gender system distinguishing masculine, feminine and neuter (Köpcke, Reference Köpcke1982). Approximately half of all German nouns are masculine, 30% is feminine and the remaining 20% is neuter (Hohlfeld, Reference Hohlfeld2006). Gender is marked on indefinite and definite determiners and on adjectives in indefinite singular DPs (Table 2). German marks not only gender but also number and case on articles.

Table 2. Description of the grammatical gender system of German

The German gender system is semi-transparent (Kupisch et al., Reference Kupisch, Geiss, Mitrofanova and Westergaard2022), meaning that there exist noun-internal cues that tend to predict a noun’s gender. In German, these cues are semantic, morphological and phonological. However, gender cues in German are considered probabilistic tendencies rather than deterministic rules (Köpcke, Reference Köpcke1982), meaning that nouns containing certain cues show a tendency to be associated with a particular gender (Szagun et al., Reference Szagun, Stumper, Sondag and Franik2007). For example, the suffix -heit requires feminine gender (e.g., dieFEM Weisheit “the wisdom”), words ending in -er are typically masculine (e.g., derMASC Arbeiter “the worker”) and the diminutive suffix -chen indicates neuter (e.g., dasNEUT Märchen “the fairy tale;” Hohlfeld, Reference Hohlfeld2006).

1.4.1. Acquisition of grammatical gender in German

Despite the seeming complexities of the system, grammatical gender is acquired early by monolingual German children. In a longitudinal study, Szagun et al. (Reference Szagun, Stumper, Sondag and Franik2007) showed that children start using gender-marked articles in their second year of life and that error rates for gender marking drop rapidly below 10% by the age of three. A recent study by Kupisch et al. (Reference Kupisch, Geiss, Mitrofanova and Westergaard2022) showed that children acquiring German use phonological cues to assign gender to nouns, although gender assignment based on phonological cues was significantly less successful for nonce nouns. This highlights that in semi-transparent languages such as German, despite children’s sensitivity to phonological gender cues, there is an important role for lexical learning (Kupisch et al., Reference Kupisch, Geiss, Mitrofanova and Westergaard2022). Nevertheless, children generally acquire grammatical gender before age 3, which is considerably younger than in Dutch monolingual children.

The acquisitional steps of grammatical gender in bilingual children acquiring German as a societal language resemble those of monolingual acquisition (see Kupisch et al., submitted, for an overview). Kupisch et al. (Reference Kupisch, Geiss, Mitrofanova and Westergaard2022), in a study testing 3- to 11-year-old Russian-German bilingual children, showed that both monolingual and bilingual children used all three grammatical genders productively. Lindauer (Reference Lindauer2024) tested Italian-German and Turkish-German bilingual children and monolingual German children. She found that the monolingual children performed better on gender assignment than the bilingual groups, but that this difference disappeared almost completely when the amount of exposure was taken into account. Cross-linguistic influence was suggested to play a role as well: Italian-German bilinguals performed better on German masculine and feminine nouns (two gender values that exist in Italian) than on neuter nouns. These and other studies investigating the gender development of German as a societal language show that differences between monolingual and bilingual children are predominantly of a quantitative nature, partially driven by cross-linguistic influence.

1.5. Grammatical gender in French

Modern Standard French has a semi-transparent, two-gender system distinguishing masculine and feminine (Lyster, Reference Lyster2006). Over half of the French nouns are masculine (58%; Corbett, Reference Corbett1991). Gender is marked on determiners and adjectives in definite and indefinite DPs (Table 3). Grammatical gender is not marked on plural definite determiners – always les – nor on plural indefinite determiners – always des (Krenca et al., Reference Krenca, Hipfner-Boucher and Chen2020).

Table 3. Description of the grammatical gender system of French

Like German, the French gender system is semi-transparent with semantic, morphological and phonological gender cues predicting a noun’s gender (Kupisch et al., Reference Kupisch, Geiss, Mitrofanova and Westergaard2022). For example, nouns ending in -ment are generally masculine (e.g., leMASC commencement “the beginning”) and words ending in -ion are typically feminine (e.g., laFEM revolution “the revolution;” Eichler et al., Reference Eichler, Jansen and Müller2013), but exceptions are omnipresent (Krenca et al., Reference Krenca, Hipfner-Boucher and Chen2020). An example of a semantically based assignment tendency is that nouns denoting fruits tend to be feminine (e.g., laFEM pomme “the apple”).

1.5.1. Acquisition of grammatical gender in French

The French grammatical gender system is acquired well before age three (Kupisch et al., Reference Kupisch, Müller and Cantone2002). A corpus analysis by Kupisch et al. (Reference Kupisch, Müller and Cantone2002) revealed an error rate below 2% in gender assignment in children younger than three. Tucker et al. (Reference Tucker, Lambert and Rigault1977) demonstrated that French children use phonological cues to predict a noun’s gender for both real and nonce words. The monolingual children in their study used regularities to assign gender to nonce words, suggesting that children actively use phonological cues in gender assignment. Recall that for German, Kupisch et al. (Reference Kupisch, Geiss, Mitrofanova and Westergaard2022) found that children relied on a combination of phonological cues and lexical learning. For French, phonological regularities seem to play a more important role in gender assignment.

The acquisition of grammatical gender in bilingual French children is comparable to that of monolingual children (Eichler et al., Reference Eichler, Jansen and Müller2013; Granfeldt, Reference Granfeldt2018; Kupisch et al., Reference Kupisch, Müller and Cantone2002; Möhring, Reference Möhring2001). For example, the simultaneous French-Swedish bilingual children tested by Granfeldt (Reference Granfeldt2018) were over 90% accurate in gender assignment. Similarly, the French-German and French-Italian bilingual children studied from age 1;6 to 5;4 in Eichler et al. (Reference Eichler, Jansen and Müller2013) had an overall accuracy of 95%. This shows that bilingual children actively and accurately use grammatical gender in French.

1.6. Present study

Few studies have investigated cross-linguistic influence in non-transparent gender systems. Therefore, little is known about the stage at which cross-linguistic influence occurs in languages with such gender systems. The present study investigated if there was cross-linguistic influence in the bilingual development of grammatical gender in Dutch and if it takes place at the stage of gender discovery, gender assignment or gender agreement. Our research questions were as follows:

-

1. Is there evidence for cross-linguistic influence in the discovery of grammatical gender in Dutch-French and Dutch-German bilingual children?

-

2. Is there evidence for cross-linguistic influence in the assignment of grammatical gender on determiners in Dutch-French and Dutch-German bilingual children?

-

3. Is there evidence for cross-linguistic influence in the agreement of grammatical gender on adjectives in Dutch-French and Dutch-German children?

We predicted cross-linguistic influence in the discovery of grammatical gender for bilingual Dutch-French and Dutch-German children. German and French both have more transparent gender systems than Dutch, which we expected to increase awareness of grammatical gender as a feature in Dutch, resulting in an earlier discovery of grammatical gender in the language (in line with Egger et al., Reference Egger, Hulk and Tsimpli2018). We operationalized this by measuring evidence of use of both gender values of the Dutch grammatical gender system in the children, that is, whether children used neuter gender at least once throughout the experiment, rather than only the default common gender value. As such, we measured the productive outcome of gender discovery. Cross-linguistic influence is expected to manifest itself in an equal or greater proportion of children using both gender values available in Dutch in the Dutch-French and Dutch-German groups compared to the monolingual Dutch group.

We furthermore predicted cross-linguistic influence in the assignment of grammatical gender for Dutch-German bilingual children. We hypothesized that overlapping gender values in Dutch-German bilinguals could lead to co-activation of the gender system of the non-target language German, potentially influencing gender assignment in this group. Specifically, we expected Dutch-German bilinguals to outperform Dutch-French bilinguals on lexical items with congruent gender values between Dutch and German (i.e., when Dutch neuter maps onto German neuter or Dutch common onto German masculine or feminine), but for items with incongruent gender values between Dutch and German, we expected a worse performance than the Dutch-French group for Dutch-German bilingual children.

Finally, we predicted that both the bilingual Dutch-French and Dutch-German children would perform well on gender agreement once they have discovered grammatical gender in Dutch. However, given the typological proximity between gender marking in Dutch and German (i.e., gender agreement is gender-specific for adjectives in indefinite NPs only), we expected that once we took correct gender assignment on the noun into account (Polišenská, Reference Polišenská2010), the bilingual Dutch-German children would outperform the bilingual Dutch-French children.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were 74 Dutch-French bilingual children, 77 Dutch-German bilingual children and 64 monolingual Dutch children. All bilingual children spoke Dutch as a heritage language.

The 74 Dutch-French bilingual children (ages 5–8, Mage = 78 months, SD = 16 months, 35 girls) were recruited in Paris, Ferney-Voltaire and the Côte d’Azur. All children attended education in French, but most children (n = 66) additionally attended 3–6 hours of Dutch education per week. Dutch education was either integrated into their regular curriculum or took place at language schools. Almost all children (n = 68) were exposed to Dutch and French from birth; the other children were exposed to Dutch from birth and were first exposed to French before age 4. Some children (n = 10) spoke an additional language at home (Italian, n = 1; Chinese, n = 1; Portuguese, n = 1; Spanish, n = 2; English, n = 5).

The 77 Dutch-German bilingual children (ages 5–8, Mage = 81 months, SD = 15 months, 39 girls) were recruited in Berlin, Hamburg, Frankfurt am Main, Cologne and Düsseldorf. All children attended education in German, but most children (n = 67) additionally attended 3 hours of Dutch education per week at Dutch language schools. Almost all children (n = 68) were exposed to Dutch and German from birth; the others were exposed to Dutch from birth and were first exposed to German before age 4. Some children (n = 11) spoke an additional language at home (Italian, n = 1; Swahili, n = 1; English, n = 2; Russian, n = 6; Polish, n = 1).

The Dutch-French and Dutch-German bilingual children had comparable current (Dutch-French: M = 0.33 (SD 0.16); Dutch-German: M = 0.37 (SD 0.17)) and cumulative (Dutch-French: M = 0.36 (SD 0.19); Dutch-German: M = 0.33 (SD 0.14)) exposure to Dutch, as well as comparable current (Dutch-French: M = 0.29 (SD 0.19); Dutch-German: M = 0.34 (SD 0.19)) and cumulative (Dutch-French: M = 0.32 (SD 0.21); Dutch-German: M = 0.29 (SD 0.15)) use of Dutch. See Supplementary Materials 4 for corresponding figures.Footnote 1

We additionally tested 64 monolingual Dutch children (ages 5–8, Mage = 75 months, SD = 9 months, 31 girls). All children grew up in the Netherlands in monolingual Dutch-speaking families.

2.2. Materials

To answer our research questions, we administered a grammatical gender task. To account for differences in language proficiency between monolingual and bilingual children, we also measured all children’s Dutch language proficiency and bilingual children’s societal language proficiency. Finally, children’s non-verbal intelligence was measured to ensure comparability between groups. In what follows, we describe the administered tasks in more detail.

2.2.1. Grammatical gender tasks

We selected 32 Dutch nouns that are typically acquired before age 6 (M = 4.49, SD = 0.80; Brysbaert et al., Reference Brysbaert, Stevens, De Deyne, Voorspoels and Storms2014). The complete list of items can be found in Supplementary Materials 1. The selected nouns were paired with two color adjectives. Images were selected that depicted the meaning of the NPs (e.g., a red window and a blue window).

The nouns were divided into four conditions contrasting gender in Dutch (common de versus neuter het) and gender congruency with the German translation equivalent (congruent versus incongruent). We followed Lemhöfer et al. (Reference Lemhöfer, Spalek and Schriefers2008) by considering translation pairs to be congruent when Dutch neuter maps onto German neuter and when Dutch common maps onto German feminine or masculine (Table 4). Because the Dutch and French gender systems do not share gender values, gender congruency was not defined for this language combination.

Table 4. Conditions of the grammatical gender task

Note: Half of the items per condition are cognates.

We controlled for cognate status by selecting stimulus items that are cognates in Dutch and German for half of the items per condition. Words were considered cognates when they were phonologically identical or very similar in Dutch and German (based on Lemhöfer et al., Reference Lemhöfer, Spalek and Schriefers2008).

The adjective–noun combinations were used in a collaborative task. The child and experimenter were both given a magnetic board and a pile of cards with the 32 image pairs of contrasting colors (Figure 2). The goal of the task was to end up with identical magnetic boards. For each image pair, the child was asked to describe the images, eliciting two indefinite DPs (e.g., ik heb een blauw raam en een rood raam “I have a blue window and a red window”), and to select one, eliciting a definite DP (e.g., ik kies het blauwe raam “I pick the blue window”). The child was invited to place the selected image somewhere on the magnetic board. Once all the spots on the magnetic board were filled (Figure 2), the child and the experimenter tried to match the location of the images on their boards by means of questions and answers. The experimenter asked the child questions based on some predetermined orientation marks, such as: “what is below the pink lollipop?,” thereby eliciting a second definite DP (e.g., het blauwe raam “the blue window;” Figure 2). The images that served as orientation marks depicted nouns that were not used as stimuli. Both common and neuter nouns were selected, and they were always pink or orange, because there is no adjectival inflection on these colors.

Figure 2. Example of the gender elicitation task. Target response: ik heb een rood raam en een blauw raam. Ik kies voor het blauwe raam (I have a red window and a blue window. I pick the blue window). After selecting an image, the child was invited to place the image on the magnetic grid.

2.2.2. Sentence repetition task

Language proficiency was measured using the LITMUS Sentence Repetition Task (Armon-Lotem & Marinis, Reference Armon-Lotem, Marinis, Armon-Lotem, De Jong and Meir2015). In this task, children listened to sentences and had to repeat what they heard. Repeating a sentence requires the child to process the sentence and to analyze and reconstruct its meaning using their own grammatical system (Armon-Lotem & Marinis, Reference Armon-Lotem, Marinis, Armon-Lotem, De Jong and Meir2015). It is generally assumed that children are able to repeat a structure only if they have acquired it. Sentence repetition tasks are therefore considered to be a good measure of children’s vocabulary knowledge and morphosyntactic abilities (Polišenská et al., Reference Polišenská, Chiat and Roy2015).

Dutch language proficiency was measured for monolingual and bilingual children with the LITMUS-NL Sentence Repetition Task (De Jong et al., Reference De Jong, Blom and Van Dijk2021) and bilingual children additionally took the task in the societal language (LITMUS SRT French: Tuller et al., Reference Tuller, Hamann, Chilla, Ferré, Morin, Prevost, Dos Santos, Abed Ibrahim and Zebib2018; LITMUS SRT German: Hamann & Abed Ibrahim, Reference Hamann and Abed Ibrahim2017). The Sentence Repetition Task consisted of 30 sentences per language that were presented auditorily through headphones in a fixed order. The target sentences varied in complexity: from short sentences in the present simple to sentences containing object relative clauses. Responses were scored for (1) verbatim repetitions, (2) grammatical repetitions, (3) grammatical repetitions disregarding grammatical gender errors and (4) target structure repetitions (see Supplementary Materials 3 for a description of the scoring methods and their correlations). The scores were highly correlated (r ≥ 0.88). We, therefore, used grammatical repetitions, disregarding grammatical gender errors, which measured whether children produced a grammatically correct utterance in their repetition of the target sentence without counting errors for grammatical gender. As such, our independent variable, language proficiency, did not include instances of our dependent variable, elicitation of grammatical gender.

2.2.3. Non-verbal intelligence

Non-verbal intelligence was measured using the Wechsler Non-verbal Scale of Ability (Wechsler & Naglieri, Reference Wechsler and Naglieri2012). The matrix reasoning subtask was administered to get an impression of children’s non-verbal intelligence. This subtask consists of matrices made up of geometric figures. One part of the matrix is always missing. The child is asked to select the figure out of five that completes the matrix. Responses were scored for correctness: a score of 1 was given for a correct response and a score of 0 for an incorrect response. The test ended when children gave four incorrect responses on five consecutive items.

2.2.4. Parental questionnaire

Detailed information about children’s language history, exposure and use was collected with the Q-BEx questionnaire (De Cat et al., Reference De Cat, Kašćelan, Prevost, Serratrice, Tuller and Unsworth2022). In addition to the required modules, Background information and Risk Factors, two additional modules were selected to retrieve the information on children’s language background: language exposure and use and Richness of linguistic experience. The questionnaire automatically returns a measure of current and cumulative language exposure and use.

2.3. Procedure

Informed consent was obtained from all parents. All children were tested individually in a quiet room at their home or at their school by a native experimenter. Children’s responses were recorded using an audio recorder and checked afterwards. Parents filled in the Q-BEx questionnaire prior to the first test session. Children completed the tasks in the following order: gender task (part 1), non-verbal intelligence task, gender task (part 2), LITMUS SRT Dutch.Footnote 2

For the bilingual children, a second session took place within 2 weeks after the first session. During this session, children completed tasks in their societal languages (French or German). The second session took place online via Zoom or at children’s schools by a near-native experimenter. The children completed the LITMUS SRT French or LITMUS SRT German.

2.4. Coding and analysis

Responses on the grammatical gender task were coded by the experimenter and checked based on audio recordings. Usable responses were determiners in definite noun phrases and adjectives in indefinite noun phrases. If the child produced a usable response, it was coded as being correct (e.g., het rode raam “the.n red window.n”) or incorrect (e.g., de rode raam “the.c red window.n”). Other responses were excluded from analyses (see Supplementary Materials 2). For each noun, there were two responses of a definite DP and two responses of an indefinite DP. After scoring children’s responses on individual items, a consistency score was calculated: children received a score of 1 when they correctly assigned grammatical gender in both elicitations and a score of 0 when they incorrectly assigned gender on one or both elicitations. Lastly, we calculated evidence of the use of neuter gender: children received a score of 1 when they used neuter gender at least once throughout the experiment and a score of 0 when no instances of neuter gender occurred. There were a few children who did not produce any usable responses throughout the experiment (monolingual, n = 1; bilingual Dutch-French, n = 8; bilingual Dutch-German, n = 3). These children were not included in the analyses.

To investigate cross-linguistic influence in gender discovery, logistic regressions (R Core Team, 2024) were used to fit children’s evidence of use of neuter gender. Contrast coding was applied to our categorical fixed effect of Group: we contrasted monolingual children (coded as 0.67) with Dutch-French children (coded as −0.33) and Dutch-German children (coded as −0.33), and subsequently contrasted Dutch-French children (coded as −0.5) with Dutch-German children (coded as 0.5). The continuous variable Proficiency was centered around zero.

To investigate cross-linguistic influence in gender assignment and gender agreement, mixed-effect logistic regressions were used to fit children’s responses on the gender elicitation task to predict accuracy using R’s lme4 package (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015). Convergence issues were addressed with the default optimizer (bobyqa; Powell, Reference Powell2009). In all models, contrast coding was applied to our categorical fixed effects (i.e., Gender, Condition and Group) and continuous variables were centered around zero (i.e., Proficiency). For Gender, the common gender (coded as 0.5) was contrasted with the neuter gender (coded as −0.5). For Condition, congruent pairs (coded as 0.5) were contrasted with incongruent pairs (coded as −0.5). For Group, we contrasted monolingual children (coded as 0.67) with Dutch-French children (coded as −0.33) and Dutch-German children (coded as −0.33), and subsequently contrasted Dutch-French children (coded as −0.5) with Dutch-German children (coded as 0.5).

In all models, we controlled for language proficiency (i.e., Proficiency). The background variable Age was added last. This background variable was kept only when it improved the model fit. Models were compared on the goodness of fit by means of likelihood ratio tests using the anova function in the R base package (R Core Team, 2024). Significant interactions of the best-fitting models were plotted using the sjPlot package (Lüdecke, Reference Lüdecke2024).

3. Results

3.1. Background measures

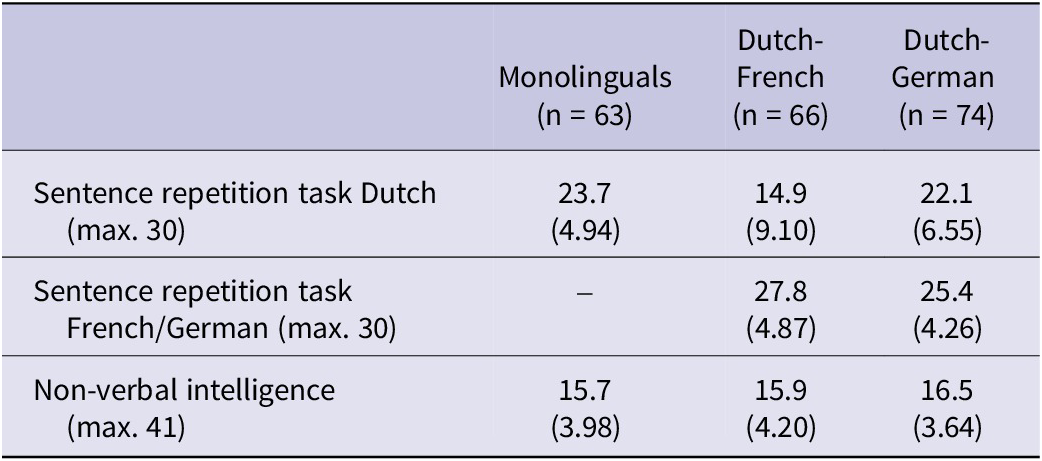

Children’s scores on the background measures are reported in Table 5. The monolingual group and bilingual Dutch-German group scored higher than the bilingual Dutch-French group on Dutch language proficiency.Footnote 3 The bilingual groups scored alike on societal language proficiency and all three groups performed similarly on non-verbal intelligence.

Table 5. Mean (SD) on background measures for bilingual Dutch-German and Dutch-French and monolingual children

3.2. Grammatical gender task

The number of usable responses on the grammatical gender task was high for determiners (monolingual group: 84%, Dutch-French group: 77%, Dutch-German group: 84%) and adjectives (monolingual group: 90%, Dutch-French group: 71%, Dutch-German group: 80%). Details of all statistical models presented below can be found in the Appendix Tables A1–A3.

3.2.1. Cross-linguistic influence in gender discovery

We first explored cross-linguistic influence in gender discovery by measuring evidence of the use of both gender values of the Dutch gender system. In the monolingual group, 92% of the children (n = 58) used neuter gender at least once. In the Dutch-German group, 87% of the children did so (n = 67) and in the Dutch-French group, 42% of the children (n = 31) showed evidence of use of both gender values.

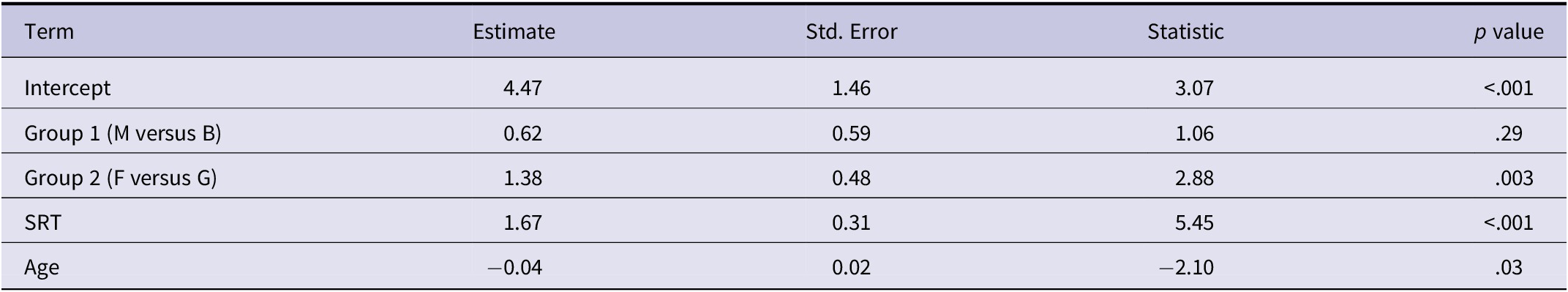

The best-fitting logistic regression model revealed a main effect of Proficiency (ß = 1.67, SE = 0.31, z = 5.45, p < .001), Age (ß = −0.04, SE = 0.02, z = −2.10, p = .04) and Group when the two bilingual groups were compared (Monolingual versus Dutch-French and Dutch-German: ß = 0.62, SE = 0.59, z = 1.06, p = 0.29; Dutch-French versus Dutch-German: ß = 1.38, SE = 0.48, z = 2.88, p = .004). The latter entailed that the Dutch-German bilingual children used the neuter gender more frequently than the Dutch-French bilingual children. This is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Main effect of group controlling for SRT grammar score (language proficiency). Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

3.2.2. Cross-linguistic influence in gender assignment

To investigate cross-linguistic influence in gender assignment, we compared elicitations of determiners in the three groups. The best-fitting model revealed a main effect of Gender (ß = 4.15, SE = 0.25, z = 16.37, p < .001), Condition (ß = .69, SE = 0.24, z = 2.84, p = .004) and Proficiency (ß = 0.72, SE = 0.10, z = 7.14, p < .001), and significant two-way interactions between Gender and Group (Monolingual versus Dutch-French and Dutch-German: ß = −1.28, SE = 0.23, z = −5.48, p < .001; Dutch-French versus Dutch-German: ß = −2.25, SE = 0.30, z = −7.45, p < .001) and Condition and Group (Monolingual versus Dutch-French and Dutch-German: ß = −1.04, SE = 0.21, z = −4.81, p < .001; Dutch-French versus Dutch-German: ß = 2.65, SE = 0.28, z = 9.50, p < .001). Finally, the three-way interaction between Gender, Language and Condition was also significant (Monolingual versus Dutch-French and Dutch-German: ß = −1.34, SE = 0.43, z = −3.09, p = .002; Dutch-French versus Dutch-German: ß = 2.57, SE = 0.55, z = 4.65, p < .001). This three-way interaction means that the accuracy of determiners depended on the gender of the noun and was mediated by group (monolingual, Dutch-French, Dutch-German) and condition (which influenced responses of the Dutch-German group only, given that the congruent–incongruent distinction was based on the grammatical gender of the German translation equivalent). The three-way interaction is depicted in Figure 4. For the common gender, the monolinguals and the Dutch-French bilingual children perform at (near) ceiling, with the Dutch-French group outperforming the monolingual group (details of pairwise comparisons can be found in Supplementary Materials 4). The Dutch-German group performed at ceiling for common nouns when gender is congruent (e.g., de kat – die Katze “the cat”), but not for nouns in the incongruent condition (e.g., de auto – das Auto “the car”). On congruent neuter nouns (e.g., het bed – das Bett “the bed”), Dutch-German children performed equally well as monolingual children and significantly better than Dutch-French children. On incongruent neuter nouns (e.g., het hert – der Hirsch “the deer”), the Dutch-German group and the Dutch-French group performed on a par.

Figure 4. Three-way interaction between gender, condition and language. Vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

We ran the same analyses (1), including only children who used neuter gender at least once throughout the experiment and (2) excluding children speaking an additional heritage language. This did not change the significant interactions of the model. Details of the statistical models and corresponding figures can be found in Supplementary Materials 5 and 6.

3.2.3. Exploratory analysis: Cognate effect in Dutch-German bilinguals

Due to the high degree of form overlap between cognates, co-activation of translation equivalents – and hence their gender – has been shown to be higher for cognates than for non-cognates (Lemhöfer et al., Reference Lemhöfer, Spalek and Schriefers2008). To further explore co-activation of gender values in Dutch-German bilinguals, we investigated the effect of cognate status on children’s gender assignment. The best-fitting model revealed a main effect of Gender (ß = 3.48, SE = 0.29, z = 11.92, p < .001), Condition (ß = 2.37, SE = 0.29, z = 8.3, p < .001) and Proficiency (ß = 0.57, SE = 0.12, z = 4.93, p < .001), and significant two-way interactions between Condition and Gender (ß = 1.98, SE = 0.56, z = 3.51, p < .001) and Condition and Cognate (ß = 1.37, SE = 0.56, z = 2.43, p = .02). Dutch-German children overall performed better on congruent than on incongruent nouns. For incongruent nouns, performance was better for non-cognates than for cognates. Corresponding figures can be found in Supplementary Materials 4.

3.2.4 Cross-linguistic influence in gender agreement

To investigate cross-linguistic influence in gender agreement, we compared elicitations of adjectives for nouns to which children correctly assigned gender (operationalized as two correct elicitations of the determiner). The best-fitting model revealed a significant main effect of Gender (ß = 3.11, SE = 0.29, z = 10.67, p < .001), Proficiency (ß = 1.18, SE =0.18, z = 6.45, p < .001) and Age (ß = −0.02, SE = 0.01, z = −2.02, p = .04) and a significant interaction between Gender and Group (Monolingual versus Dutch-French and Dutch-German: ß = −0.70, SE = 0.51, z = −1.37, p = 0.17; Dutch-French versus Dutch-German: ß = −3.24, SE = 0.64, z = −5.10, p < .001). This is depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Two-way interaction between gender and group controlling for SRT grammar score (language proficiency). Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated cross-linguistic influence in the acquisition of grammatical gender in Dutch-French and Dutch-German bilingual children. We looked at cross-linguistic influence in three stages of gender acquisition: gender discovery, gender assignment and gender agreement. We now turn to a discussion of our findings for each stage separately.

4.1. Gender discovery

Our first research question asked whether there was cross-linguistic influence at the stage of gender discovery, that is, whether bilingual children discover the existence of grammatical gender in the target language (i.e., Dutch) earlier than monolingual children. We predicted cross-linguistic influence in the form of acceleration, manifested in an equal or greater proportion of children using both Dutch grammatical gender values in the bilingual groups compared to the monolingual group. We hypothesized that such acceleration would stem from increased awareness of grammatical gender as a feature of the noun, thanks to bilingual children’s knowledge of a more transparent gender system in their other language.

In young acquirers of Dutch, the stage preceding the discovery of grammatical gender is characterized by an overuse of the determiner de. In this early phase, de functions as a default determiner for definite nouns rather than as a marker of grammatical gender (Keij et al., Reference Keij, Cornips, Van Hout, Hulk and Van Emmerik2012). It is only once children have discovered the existence of the grammatical gender system that they begin to differentiate between common determiner de and neuter determiner het. Our operationalization of gender discovery captures this development by measuring evidence of use, that is, whether children used neuter gender at least once during the experiment, thereby making use of both gender values of the Dutch system.

Almost all monolingual Dutch children used both gender values productively, as would be expected in this age range. The proportion of children in the Dutch-German group who used neuter gender at least once was comparable to that of the monolingual group. Contrary to our predictions, however, this was not the case for the Dutch-French group: throughout the experiment, less than half of the children used neuter gender productively. Differences in language proficiency between the Dutch-French group and the other groups accounted for a large part of this variation. In fact, the best-fitting model, controlling for language proficiency, reported no significant differences between the monolingual group and the bilingual group.

The Dutch-French group did, however, significantly differ from the Dutch-German group. Specifically, children in the Dutch-German group were more likely to show evidence of gender discovery than children in the Dutch-French group, even at comparable levels of language proficiency. This suggests that properties of the other language influence gender discovery beyond language proficiency. The typological proximity between Dutch and German – and in particular, the presence of neuter gender in both languages – may account for this effect. Exposure to neuter gender in German may strengthen the children’s sensitivity to this gender value in Dutch, facilitating the discovery that Dutch marks grammatical gender in a similar way.

This finding contrasts with the results reported by Rodina et al. (Reference Rodina, Kupisch, Meir, Mitrofanova, Urek and Westergaard2020), who examined gender acquisition in heritage Russian across different societal language contexts. Russian has a three-gender system (masculine, feminine and neuter) and both German and Norwegian – two of the five societal languages in their study – also have neuter gender. Based on this overlap, Rodina et al. predicted acceleration for Russian-German and Russian-Norwegian bilingual children relative to bilinguals whose societal language lacked neuter gender. However, no such acceleration was observed. Several differences between our study and that of Rodina et al. may explain this discrepancy, the most important being the transparency of the gender systems involved. In our study, the heritage language was less transparent than the societal languages, whereas in Rodina et al.’s study, the heritage language was more transparent than the societal languages. Both transparency and linguistic context (societal versus heritage language) have been shown to affect cross-linguistic influence (Van Dijk et al., Reference Van Dijk, Van Wonderen, Koutamanis, Kootstra, Dijkstra and Unsworth2022). Cross-linguistic influence is stronger from the societal language into the dominant language. As such, having a more transparent system in a societal language might facilitate the acquisition of a non-transparent system in the heritage language more than having a less transparent system in the societal language and a transparent system in the heritage language. These differences between our study and Rodina et al. likely contributed to the contrasting findings.

Our results are more in line with those reported by Egger et al. (Reference Egger, Hulk and Tsimpli2018), who found evidence of acceleration in grammatical gender acquisition among bilingual children acquiring two languages with neuter gender. In their study, Dutch-Greek bilingual children performed on a par with monolingual Dutch children and outperformed Dutch-English bilinguals. Although English does not mark grammatical gender – making direct comparison with our study difficult – the overall pattern supports the idea that overlap in gender values between languages can facilitate gender acquisition in bilinguals.

Our operationalization of gender discovery is a rough measure, indicating whether children had reached this milestone by assessing whether they used the neuter determiner het at least once. While this approach captures productive evidence of the use of both gender values, it does not provide precise information about when the discovery occurred. Many children in our sample had already discovered grammatical gender in Dutch before the time of testing. As such, our design does not capture the full picture of cross-linguistic influence in gender discovery. To better understand the timing of gender discovery in bilingual children, future research should test younger children and use more fine-grained measures, such as the proportion of neuter use. That way, the moment children first become aware of grammatical gender can be identified and cross-linguistic influence can be further examined.

4.2. Gender assignment

Our second research question investigated cross-linguistic influence at the stage of gender assignment. We explored whether there is co-activation between the gender values of Dutch and German in Dutch-German bilingual children. We hypothesized that such co-activation would facilitate gender assignment for nouns with gender congruency between Dutch and German but would hinder it for nouns that have different gender values. We found that this was indeed the case: Dutch-German children outperformed Dutch-French bilingual children on items with congruent gender values between Dutch and German, but they performed on a par (neuter) or worse (common) than the Dutch-French group for items with incongruent gender values between Dutch and German.

Whether bilingual children have integrated gender systems has not been investigated before. Evidence of integrated gender systems in bilingual children came from a gender congruency effect on determiners (and adjectives, see Supplementary Materials 7). This novel finding suggests that bilingual children with overlapping gender values between their languages activate not only the gender value of the target language but also the gender value of the translation equivalent. Our findings demonstrate a qualitative difference from monolingual development, where overgeneralization generally happens in one direction, that is, children produce common de for neuter nouns, but hardly ever the other way around (Tsimpli & Hulk, Reference Tsimpli and Hulk2013). However, the Dutch-German bilingual children in our study also produced neuter het for common nouns. Importantly, this did not happen randomly. The effect was driven by gender congruency in German: children almost exclusively did this when the translation equivalent of the items had neuter gender in German.

Evidence for integrated gender systems in bilingual children was reinforced by the cognate effect found in gender assignment for Dutch-German bilingual children. Because half of the items in each condition were cognates in Dutch and German, this allowed for an exploratory analysis of potential cognate effects. These analyses revealed that children were less accurate on cognates (e.g., Dutch: “deCOM auto;” German: “dasNEUT Auto” the car) than on non-cognates (e.g., Dutch: “deCOM kip;” German: “dasNEUT Huhn” the chicken) when lexical items had incongruent gender values between Dutch and German, consistent with accounts proposing stronger lexical co-activation for cognates (Lemhöfer et al., Reference Lemhöfer, Spalek and Schriefers2008). This supports the idea that the gender systems of bilingual children are connected and that experiences with grammatical gender in one language can influence the other language. However, because cognate effects were not the main focus of the study and the analyses were exploratory, some caution is required in interpreting these findings. Future research should study more systematically how cognate status influences cross-linguistic influence in bilingual children.

The finding that systems with overlapping gender values are connected raises the question of whether this leads to shared representations of grammatical gender between languages or whether the systems remain largely separate but develop interconnections. This question has previously been addressed for other syntactic domains by means of structural priming paradigms (see Van Gompel & Arai, Reference Van Gompel and Arai2018). Cross-linguistic structural priming effects have been interpreted as evidence for shared structures in bilingual children (e.g., Hsin et al., Reference Hsin, Legendre and Omaki2013; Unsworth, Reference Unsworth2023; Vasilyeva et al., Reference Vasilyeva, Waterfall, Gámez, Gómez, Bowers and Shimpi2010). Hartsuiker and Bernolet (Reference Hartsuiker and Bernolet2017) proposed an account explaining how shared structures develop. They argue that learners start out with item-specific and language-specific representations, which gradually develop into abstract, shared representations when structures are similar in form and after sufficient exposure. Shared representations of grammatical gender in bilingual children might develop in a similar way when gender values overlap across languages. This possibility is compatible with both theoretical accounts of grammatical gender: shared values may arise at the lemma level in the lexicalist approach or at the level of syntactic derivation in the syntactic approach.

With our research design, we cannot provide conclusive evidence for either fully shared representations or separate but interconnected representations. However, our exploratory analysis investigating the relationship between gender congruency and language proficiency in the Dutch-German group does provide some support for shared representations (see Supplementary Materials 8). We found that the effect of gender congruency increased with higher Dutch proficiency. Children with lower proficiency performed similarly on congruent and incongruent nouns, whereas children with higher proficiency performed better on congruent nouns. For incongruent nouns, highly proficient children were more likely to use the gender value of the German translation equivalent. This pattern suggests that shared representations emerge gradually as proficiency increases, in line with Hartsuiker and Bernolet’s (Reference Hartsuiker and Bernolet2017) account. However, given that this analysis was done post hoc, future research should investigate the distinction between shared syntactic structures and separate but interconnected structures in more detail.

Cross-linguistic influence in gender assignment was not expected for the Dutch-French bilingual children, given the lack of overlap between the gender systems of Dutch and French. Instead, children in this group were expected to show a pattern similar to what is typical for monolingual development, namely, an overgeneralization of common gender for neuter nouns, which is indeed what we found. At the same time, the Dutch-French group had significantly lower Dutch language proficiency than the other two groups. This raises the possibility that the absence of cross-linguistic influence may not solely reflect typological distance but could also be linked to children’s lower Dutch proficiency. In other words, children in the Dutch-French group may not yet have sufficient proficiency in Dutch to discover its grammatical gender system. This could have prevented the development of connections between gender values and, consequently, the emergence of cross-linguistic influence.

Findings related to our first research question indeed showed that fewer than half of the Dutch-French bilingual children had discovered and productively used both gender values in Dutch. To account for this, we reran the analysis for gender assignment, including only those children who showed evidence of productive use of both gender values (see Supplementary Materials 5). This resulted in a subsample of bilingual Dutch-French children with higher Dutch proficiency than the full group (SRT scores subsample: M = 20.1, SD = 7.6; full sample: M = 13.6, SD = 9.4) and whose proficiency was comparable to that of the two other groups. The analysis using this subsample, including only children who used neuter gender at least once, did not differ from the analysis with the full dataset. This suggests that cross-linguistic influence in gender assignment does not emerge in the absence of overlap between the gender systems, at least when the target language is non-transparent. However, as this analysis was conducted post hoc, future research should match groups more closely on language proficiency to provide conclusive answers to this question.

4.3. Gender agreement

Finally, our third research question examined whether there was cross-linguistic influence in gender agreement when individual gender assignment on the noun was taken into account. We predicted that both groups would perform well, but that Dutch-German children would outperform Dutch-French children, given the similarities between gender marking in Dutch and German. This prediction was partially borne out. Dutch-German bilinguals and monolinguals outperformed Dutch-French bilinguals on gender agreement with neuter nouns. Dutch-French bilinguals performed on a par with monolinguals and outperformed Dutch-German bilinguals in adjectival inflection for common nouns.

The latter finding cannot be conclusively interpreted as a facilitation effect in the Dutch-French group, as adjectival inflection (e.g., een groteCOM hond “a big dog”) – rather than bare adjectives (e.g., een grootNEUT paard “a big horse”) – represents the default strategy in monolingual development. Any facilitation effect would thus be expected to be visible only for neuter gender nouns, as they require the bare adjective. No such effect was observed for the Dutch-French group. Instead, we found a pattern similar to what we saw for this group in gender assignment: accuracy in adjectival inflection for neuter nouns increased with higher proficiency but was somewhat lower than in the other two groups. This may reflect the differing ways in which gender agreement is realized in Dutch and French. This aligns with Schwartz et al. (Reference Schwartz, Minkov, Dieser, Protassova, Moin and Polinsky2015), who reported that greater proximity between languages facilitates gender marking.

Given the similarity in how gender agreement is realized in Dutch and German, a facilitation effect was expected for the Dutch-German bilinguals. Surprisingly, however, the Dutch-German group performed significantly worse than the Dutch-French group on common nouns. Upon closer inspection, we hypothesized that a gender congruency effect – similar to the one observed in gender assignment – might also be influencing gender agreement. Exploratory analyses (see Supplementary Materials 7) confirmed a significant effect of gender congruency, even given that only responses were included in which children had correctly and consistently assigned gender to the noun. Specifically, Dutch-German bilinguals sometimes applied the incongruent German gender value during gender agreement, suggesting that cross-linguistic influence may persist even when gender assignment is accurate. For example, for the gender incongruent lexical item auto “car” (Dutch: common, German: neuter), when children correctly assigned common gender to the noun (i.e., de COM auto), they were still more likely to use the German gender value for inflection on the adjective (i.e., neuter: *een roodNEUT auto “a red NEUT car”). Importantly, this does not originate from form-overlap with German (i.e., ein rotes Auto “a red car”), although an anonymous reviewer suggested it might originate from the uninflected form of the adjective in German (das Auto ist rot “the car is red”). The gender congruency effect in adjective agreement emphasizes once more that cross-linguistic influence can facilitate acquisition when gender values overlap across languages (i.e., Dutch-German children performed significantly better on neuter nouns – both on gender assignment and agreement) but can also result in deviating structures when the languages are incongruent.

5. Conclusion

Our findings provide convincing evidence that the gender systems of bilingual children influence each other when there is a degree of similarity between the systems. We found cross-linguistic effects for gender discovery, gender assignment and gender agreement in children with similar gender systems (i.e., Dutch-German bilingual children) but not for children with distant gender systems (i.e., Dutch-French bilingual children). Moreover, in our study, cross-linguistic influence both facilitated and hindered the acquisition of grammatical gender within the same group of children. This emphasizes the complexity of the phenomenon and might explain the inconsistent findings in previous studies.

An additional reason why previous studies report mixed findings is that different studies compare different groups (e.g., monolingual versus bilingual or bilingual versus bilingual) and therefore interpret findings differently. For example, when two bilingual groups are compared and Group A outperforms Group B, this can either be interpreted as cross-linguistic influence in the form of a delay in Group B or an acceleration effect in Group A. In other words, the variety in methods may be reflected in the variety in findings in studies investigating cross-linguistic influence in gender acquisition. By comparing two bilingual groups and a monolingual group, we have provided a more comprehensive picture of cross-linguistic influence in grammatical gender acquisition in bilingual children (in line with Van Dijk et al., Reference Van Dijk, Van Wonderen, Koutamanis, Kootstra, Dijkstra and Unsworth2022).

Our study has a number of limitations. First, it is based exclusively on production data, which limits the level of detail that can be captured in our measures of grammatical gender acquisition. Future research could incorporate tasks of gender awareness to complete our understanding of this development in bilingual children. Second, our measure of gender discovery is rather coarse. This limited what we could learn about cross-linguistic influence at this stage, especially given the age range of the children. We recommend that future studies include younger children and adopt more fine-grained measures to address this limitation. Third, the study focused on children acquiring Dutch as the heritage language. Prior research has shown that the linguistic context in which children acquire their languages (societal versus heritage language) modulates the degree of cross-linguistic influence (Van Dijk et al., Reference Van Dijk, Van Wonderen, Koutamanis, Kootstra, Dijkstra and Unsworth2022). Consequently, the effects reported here may be stronger than what might be found in Dutch-French and Dutch-German bilingual children speaking Dutch as the societal language.

To conclude, this study is one of the few to investigate cross-linguistic influence in the acquisition of a non-transparent gender system. Furthermore, it is the first study to explore the co-activation of gender values in bilingual children. Our results suggest that cross-linguistic influence takes place during gender discovery, gender assignment and gender agreement when a non-transparent gender system is being acquired, particularly when gender values overlap between languages. These findings help us better understand what cross-linguistic interactions take place during bilingual language processing and emphasize that cross-linguistic influence can simultaneously facilitate and hinder language acquisition in bilingual children.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728926101060.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available on OSF at https://osf.io/9wa8y/?view_only=6feb9d68078e43708e75ca746dda3c7a

Acknowledgements

We thank all participating families for their valuable contribution and the Dutch schools in France and Germany for facilitating recruitment and data collection. We also thank Marcel Beentjes, Sanne van Eijsden, Naomi Smolenaers and Anne-Sophie Chalmet for their assistance with data collection.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Appendix

Table A1. Summary of optimal linear regression model for cross-linguistic influence in gender discovery

Table A2. Summary of optimal generalized linear mixed model for cross-linguistic influence in gender assignment

Note: Marginal R2/Conditional R2 0.536/0.680.

Table A3. Summary of optimal generalized linear mixed model for cross-linguistic influence in gender agreement

Note: Marginal R2/Conditional R2 0.287/0.532.